Background

Childhood poverty is robustly associated with general and specific cognitive performance deficits (Clearfield & Niman, Reference Clearfield and Niman2012; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Riis and Noble2016; Noble et al., Reference Noble, Houston, Brito, Bartsch, Kan, Kuperman, Akshoomoff, Amaral, Bloss, Libiger, Schork, Murray, Casey, Chang, Ernst, Frazier, Gruen, Kennedy, Van Zijl, Mostofsky and Sowell2015; Noble & Giebler, Reference Noble and Giebler2020). As early as six months old, youth raised with lower household incomes exhibit poorer performance on measures of total IQ and specific cognitive processes (e.g., executive function, language; Farah, Reference Farah2017; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Riis and Noble2016; Noble et al., Reference Noble, Houston, Brito, Bartsch, Kan, Kuperman, Akshoomoff, Amaral, Bloss, Libiger, Schork, Murray, Casey, Chang, Ernst, Frazier, Gruen, Kennedy, Van Zijl, Mostofsky and Sowell2015; Noble & Giebler, Reference Noble and Giebler2020). An emerging literature also supports independent contributions of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage (e.g., a greater percentage of families living in poverty, increased unemployment, lower percentage of educational attainment at the neighborhood level) to cognitive functions and brain maturation in regions associated with cognitive ability above and beyond the contributions of household socioeconomic status (SES; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Cooper, Jackson and Barch2020). Greater educational attainment among children whose families received supplemental income (Akee et al., Reference Akee, Copeland, Keeler, Angold and Costello2010; Costello et al., Reference Costello, Compton, Keeler and Angold2003, Reference Costello, Erkanli, Copeland and Angold2010) and boosts in cognitive performance induced by enriched environments in non-human animal models (Sauce et al., Reference Sauce, Bendrath, Herzfeld, Siegel, Style, Rab, Korabelnikov and Matzel2018) highlight the plausibility that multiple facets of SES may have a causal impact on child cognition, and heighten the urgency of addressing the epidemic of childhood poverty (DeNavas-Walt & Proctor, Reference DeNavas-Walt and Proctor2014; Newhouse et al., Reference Newhouse, Suarez-Becerra and Evans2016).

The moderate heritability of cognitive ability and SES (Tucker-Drob et al., Reference Tucker-Drob, Briley and Harden2013), as well as their shared genetic architecture (rg = 0.65–0.82 in adults; Hill, Davies, et al., Reference Hill, Davies, Ritchie, Skene, Bryois, Bell, Di Angelantonio, Roberts, Xueyi, Davies, Liewald, Porteous, Hayward, Butterworth, McIntosh, Gale and Deary2019; Hill, Marioni, et al., Reference Hill, Marioni, Maghzian, Ritchie, Hagenaars, McIntosh, Gale, Davies and Deary2019), has been used to argue that cognitive deficits related to childhood poverty may be partially attributable to shared genetic liability (Trzaskowski, Harlaar, et al., Reference Trzaskowski, Harlaar, Arden, Krapohl, Rimfeld, McMillan, Dale and Plomin2014). Evidence that adolescent cognitive ability is associated with adult neighborhood disadvantage has also been used to argue that associations between cognitive ability and neighborhood disadvantage may be genetically mediated (Ksinan & Vazsonyi, Reference Ksinan and Vazsonyi2021). Shared genetic liability may arise from genetic inheritance that directly influences cognitive ability as well as gene-environment correlations (e.g., between genetic propensity and higher SES environments with generally more access to cognitively stimulating activities that may be more amenable to environmental intervention (Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Domingue, Wedow, Arseneault, Boardman, Caspi, Conley, Fletcher, Freese, Herd, Moffitt, Poulton, Sicinski, Wertz and Harris2018).

Disentangling genetic and socioeconomic status associations with cognition is challenging. Twin studies may not be able to detect genetic influences on SES or the influence of SES on cognitive development, as family-level SES is typically shared within a twin pair (Trzaskowski, Harlaar, et al., Reference Trzaskowski, Harlaar, Arden, Krapohl, Rimfeld, McMillan, Dale and Plomin2014). Twin studies may also modestly overestimate the effect of genetics, given that the equal environments assumption (i.e., that monozygotic twin pairs share the same environmental similarity as dizygotic twin pairs) may not be valid (Felson, Reference Felson2014). Another approach is to measure genetic influence using polygenic scores (PGS) that effectively represent genome-wide genetic liability to a particular phenotype on an individual (rather than population) level (Wray et al., Reference Wray, Goddard and Visscher2007). Relative to heritability estimates in twin studies that violate the equal environments assumption, genetic similarities detected in GWAS of largely unrelated individuals should be minimally confounded by environmental similarities after accounting for genetic similarity to reference population(s) (and thus any influences of population stratification (Friedman et al., Reference Friedman, Banich and Keller2021).

Emerging evidence largely based on PGS for educational attainment (EduA) and family-level SES suggests that both PGS and SES have independent effects on cognition (Corley et al., Reference Corley, Conte, Harris, Taylor, Redmond, Russ, Deary and Cox2023; Judd et al., Reference Judd, Sauce, Wiedenhoeft, Tromp, Chaarani, Schliep, van Noort, Penttilä, Grimmer, Insensee, Becker, Banaschewski, Bokde, Quinlan, Desrivières, Flor, Grigis, Gowland, Heinz, Ittermann and Klingberg2020; Merz et al., Reference Merz, Strack, Hurtado, Vainik, Thomas, Evans and Khundrakpam2022; Park et al., Reference Park, Lee, Cho, Hwang, Kim, Kim, Joo and Cha2023; Raffington et al., Reference Raffington, Czamara, Mohn, Falck, Schmoll, Heim, Binder and Shing2019). Given evidence from twin studies that SES may moderate the heritability of cognitive outcomes, such that heritability is higher in higher SES environments (i.e., the Scarr-Rowe hypothesis; Hanscombe et al., Reference Hanscombe, Trzaskowski, Haworth, Davis, Dale and Plomin2012; Rowe et al., Reference Rowe, Jacobson and Van den Oord1999), recent work using PGS has also attempted to replicate this finding in the context of individual genetic propensity, with mixed evidence (Corley et al., Reference Corley, Conte, Harris, Taylor, Redmond, Russ, Deary and Cox2023; Judd et al., Reference Judd, Sauce, Wiedenhoeft, Tromp, Chaarani, Schliep, van Noort, Penttilä, Grimmer, Insensee, Becker, Banaschewski, Bokde, Quinlan, Desrivières, Flor, Grigis, Gowland, Heinz, Ittermann and Klingberg2020; Park et al., Reference Park, Lee, Cho, Hwang, Kim, Kim, Joo and Cha2023; Peñaherrera-Aguirre et al., Reference Peñaherrera-Aguirre, Woodley, Sarraf and Beaver2022; Woodley Of Menie et al., 2021).

Focusing on EduA PGS, in particular, may have limitations, given that educational attainment PGS is confounded by factors such as population stratification, assortative mating, and/or gene-environment correlation (e.g., Okbay et al., Reference Okbay, Wu, Wang, Jayashankar, Bennett, Nehzati, Sidorenko, Kweon, Goldman, Gjorgjieva, Jiang, Hicks, Tian, Hinds, Ahlskog, Magnusson, Oskarsson, Hayward, Campbell and Young2022). Thus, investigations that more comprehensively assess PGS and cognitive abilities are needed. Further, work in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study (ABCD) sample has shown that both family income (Tomasi & Volkow, Reference Tomasi and Volkow2021) and neighborhood socioeconomic poverty (e.g., median neighborhood income) have unique associations with neurocognitive performance in youth (Hackman et al., Reference Hackman, Cserbik, Chen, Berhane, Minaravesh, McConnell and Herting2021; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Cooper, Jackson and Barch2020). Thus, to examine the contributions of both PGS and SES to cognition, it is critical to measure SES comprehensively, including both the familial and neighborhood levels, and to account for genetic propensity for phenotypes, other than EduA, more directly related to cognition. Recent work using the ABCD sample incorporated PGS for cognitive performance and indicators of neighborhood adversity but did not account for family relatedness (Park et al., Reference Park, Lee, Cho, Hwang, Kim, Kim, Joo and Cha2023).

The present study tested the hypothesis that SES (i.e., family income, neighborhood socioeconomic resources) and genetic propensity (polygenic scores [PGS] for educational attainment, intelligence, and executive function) independently contribute to variance in four domains of cognitive ability (i.e., general cognitive ability, executive function, learning and memory, fluid intelligence) in a sample of 5,549 children (ages nine to 10) genetically similar to European reference populations. To reduce the influence of confounding from population stratification, assortative mating, and/or passive gene-environment correlation, we further decomposed PGS variance into between-family and within-family variance (i.e., within-siblings PGS analyses; (Selzam et al., Reference Selzam, Ritchie, Pingault, Reynolds, O’Reilly and Plomin2019). With this approach, family-mean PGS and individual deviation from that family-mean PGS are both included in the model, disaggregating confounded effects (i.e., family-mean PGS) from effects that more closely approximate direct genetic effects (i.e., individual deviations from family-mean PGS; Selzam et al., Reference Selzam, Ritchie, Pingault, Reynolds, O’Reilly and Plomin2019). Finally, given mixed evidence that SES may moderate the heritability of cognitive outcomes (Hanscombe et al., Reference Hanscombe, Trzaskowski, Haworth, Davis, Dale and Plomin2012; Rowe et al., Reference Rowe, Jacobson and Van den Oord1999), we also tested interactions between each SES metric (i.e., family income and neighborhood advantage) and each PGS.

Method

Statement on ethical regulations

Parents/caregivers provided written informed consent, and children verbal assent, to a research protocol approved by the central institutional review board at the University of California at San Diego for 21 data collection sites across the United States (https://abcdstudy.org/sites/abcd-sites.html) and by the Washington University IRB for the Washington University site.

Participants

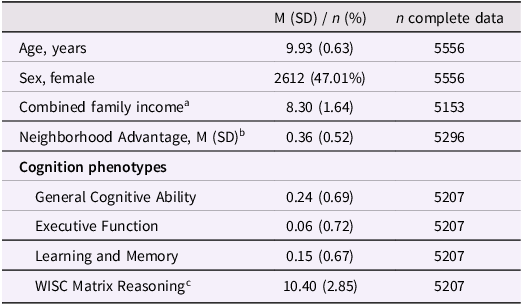

Data came from 11,875 children (mean ± SD age = 9.91 ± 0.62 years; 47.85% girls; 52.1% white; Table 1) who completed the baseline assessment of the ongoing longitudinal Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study (release 3.0; https://abcdstudy.org/; Volkow et al., Reference Volkow, Koob, Croyle, Bianchi, Gordon, Koroshetz, Pérez-Stable, Riley, Bloch, Conway, Deeds, Dowling, Grant, Howlett, Matochik, Morgan, Murray, Noronha, Spong and Weiss2018). The study includes multiple sibling and twin pairs and triplets as part of its family-based design (Garavan et al., Reference Garavan, Bartsch, Conway, Decastro, Goldstein, Heeringa, Jernigan, Potter, Thompson and Zahs2018). Primary analyses were restricted to individuals genetically similar to reference populations from Europe with available genetic data who did not withdraw consent between baseline and later study waves (n = 5549), given the lack of other ancestry-specific discovery GWAS of cognitive phenotypes and the low predictive utility of PGS when applied across ancestries (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Kanai, Kamatani, Okada, Neale and Daly2019).

Table 1. Sample characteristics

a Family income was estimated using binned gross household income and collected from the PhenX questionnaire (see Methods).

b Scaled factor score.

c Total scaled score. WISC = Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children.

Individuals in this sample were 9.9 (±0.63) years old, on average, and 47.0% of the sample were female (Table 1). Of these 5,549Footnote 1 individuals, there were 3,733 singletons as well as 1,816 individuals in 895 families. According to genetic relatedness metrics documented in ABCD release 5.1 (“gen_y_pihat.csv”), there were 863 sibling pairs (197 monozygotic pairs, 296 dizygotic pairs, 357 non-twin sibling pairs, and 13 pairs of unknown relatedness), 21 sibling trios (4 sets of triplets, 4 sets of MZ twins and 1 sibling, 11 sets of DZ twins and 1 sibling, and 2 sets of 3 siblings), one family of 4 individuals (2 sets of MZ twins), one family of five individuals (1 set of triplets, 1 set of DZ twins), and nine families of three individuals of whom only two were included in the subsample of individuals genetically similar to European reference populations (8 DZ twin pairs and 10 sibling pairs among those included).

This subsample of ABCD was slightly older at the time of assessment (t[11,637] = 2.39, p = 0.017) and exhibited lower neighborhood poverty (t[9358.5] = −48.1, p < 2.2e–16) and higher household income (t[9436] = 44.2, p < 2.2e–16) than the remainder of the ABCD sample (Table 1). Relative to the singleton sample, the sibling sample was older (t[3376.2] = 6.11, p = 1.08e–09) and had lower general ability (t[3468.8] = –7.90, p = 3.60e–15), higher executive function (t[3378.6] = 3.22, p = 1.28e–03), higher neighborhood advantage (t[3535] = 6.34, p = 2.61e–10), and higher household income (t[3655.1] = 2.54, p = 0.011).

Measures

Demographic measures

Child demographics

Child age was self-reported and measured in months. Child sex was a caregiver-reported dichotomous variable (Barch et al., Reference Barch, Albaugh, Avenevoli, Chang, Clark, Glantz, Hudziak, Jernigan, Tapert and Yurgelun-Todd2018).

Familial income

Familial income was estimated using binned gross household income and collected from the PhenX questionnaire (Barch et al., Reference Barch, Albaugh, Avenevoli, Chang, Clark, Glantz, Hudziak, Jernigan, Tapert and Yurgelun-Todd2018).

Neighborhood advantage (NAdv)

Area deprivation index values were calculated as outlined in previous investigations with the ABCD cohort (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Cooper, Jackson and Barch2020). Briefly, a participant’s primary residential address at baseline was geocoded by the Data Analysis, Informatics, and Resource Center of the ABCD Study and were linked to each individual according to their US census tract information (Singh, Reference Singh2003). Values were multiplied by -1, such that higher values represent more advantage, like family income.

Cognitive measures

Cognitive ability

Three principal components previously derived in the ABCD sample representing general cognitive ability, executive function, and learning and memory were used to index cognitive ability (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Barch, Bjork, Gonzalez, Nagel, Nixon and Luciana2019). Briefly, a Bayesian Probabilistic Principal Component Analysis (BBPCA) was applied to cognitive tasks from the NIH Toolbox cognition battery, which assesses executive function, attention, processing speed, working memory, episodic memory, and language; the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test, which measures auditory learning, memory, and recognition; and the Little Man Task, which assesses visuospatial processing (Luciana et al., Reference Luciana, Bjork, Nagel, Barch, Gonzalez, Nixon and Banich2018). BPPCA component weights for each participant were made available with the ABCD curated data release 2.0.1. The Matrix Reasoning subtest of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Fifth Edition (WISC), which indexes fluid and perceptual reasoning important for life function (Burgess et al., Reference Burgess, Gray, Conway and Braver2011; Green et al., Reference Green, Bunge, Briones Chiongbian, Barrow and Ferrer2017) was included as an additional measure of fluid intelligence.

Polygenic Scores (PGS)

Polygenic scores are weighted sums of effect alleles weighted by effect sizes found through GWAS of cognitive phenotypes. Summary statistics from the most well-powered, publicly available genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of three cognitive phenotypes (Educational Attainment (EA PGS), N = 766,345 (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Wedow, Okbay, Kong, Maghzian, Zacher, Nguyen-Viet, Bowers, Sidorenko, Karlsson Linnér, Fontana, Kundu, Lee, Li, Li, Royer, Timshel, Walters, Willoughby and Cesarini2018); common Executive Function (cEF PGS), N = 427,037 (Hatoum et al., Reference Hatoum, Mitchell, Morrison, Evans, Keller and Friedman2019); and IQ (IQ PGS), N = 269,867 (Savage et al., Reference Savage, Jansen, Stringer, Watanabe, Bryois, De Leeuw, Nagel, Awasthi, Barr, Coleman, Grasby, Hammerschlag, Kaminski, Karlsson, Krapohl, Lam, Nygaard, Reynolds, Trampush and Posthuma2018)) were used. PGS were computed using PRS-CS (Ge et al., Reference Ge, Chen, Ni, Feng and Smoller2019), a Bayesian approach that incorporates all SNPs (i.e., no p-value thresholding) and utilizes an external linkage disequilibrium (LD) reference panel to account for correlations between SNPs. The “auto” function within the PRS-CS software package was used to compute PGS (see Supplement for further details).

Genotyping, quality control, and imputation

The Rutgers University Cell and DNA repository (now incorporated with other companies as Sampled; https://sampled.com/) genotyped saliva samples on the Smokescreen array (Baurley et al., Reference Baurley, Edlund, Pardamean, Conti and Bergen2016). The genetic data underwent typical quality control procedures following the Ricopili pipeline (Lam et al., Reference Lam, Awasthi, Watson, Goldstein, Panagiotaropoulou, Trubetskoy, Karlsson, Frei, Fan, De Witte, Mota, Mullins, Brügger, Lee, Wray, Skarabis, Huang, Neale, Daly, Mattheisen and Ripke2020). Analyses were restricted to individuals most genetically similar to European reference populations, to match the ancestry makeup of the discovery GWAS. Further details are provided in the Supplement.

Each cognitive outcome (e.g., general cognitive ability, learning and memory, executive function, fluid intelligence), was regressed onto the two SES indicators, the three PGS, age, sex, and the first 10 ancestrally informative principal components (PCs), with a family identifier, and study site included as random effects. Of note, there was no evidence of multicollinearity in these models despite expected correlations between variables (variance inflation factor <2 for every variable in all models, see Supplement Table 1, Supplement Figure 1 for correlations). All continuous variables were standardized before analysis, with SES indicators standardized at the level of the family (i.e., level 2). The false discovery rate was used to correct across all SES p-values (n = 8) and, separately, all PGS p-values (n = 12).

To test whether any significant PGS effects were inflated by population stratification, assortative mating, and/or passive gene-environment correlation, we conducted within-sibling analyses in which each PGS was decomposed into between- and within-family variance (Selzam et al., Reference Selzam, Ritchie, Pingault, Reynolds, O’Reilly and Plomin2019). Specifically, both the family average PGS and each individual’s deviation from that family average PGS were included in linear mixed-effects models with the SES variables and covariates. Individual-level (within-family) estimates more closely approximate direct, or causal, genetic effects, whereas family-level estimates represent the portion of PGS effects that are confounded (Selzam et al., Reference Selzam, Ritchie, Pingault, Reynolds, O’Reilly and Plomin2019). The false discovery rate was used to correct across all SES p-values (n = 12) and, separately, all PGS p-values (n = 24).

To examine whether SES moderates the effects of PGS on cognitive abilities, a series of linear mixed-effects models were run in which each SES variable was interacted with each PGS variable (i.e., six models per cognitive outcome). Moderation models covaried for all covariate-by-SES and covariate-by-PGS interactions (Keller, Reference Keller2014). FDR was used to correct across all interaction p-values, separately for each SES and PGS (e.g., four income × EduA PGS, four NAdv × cEF PGS, etc.). All analyses were conducted in R version 4.3.2 using the lme4 package, with p-values calculated using lmer Test (Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker, Walker, Christensen, Singmann, Dai, Grothendieck, Green and BolkerD. Bates et al., Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker, Walker, Christensen, Singmann, Dai, Grothendieck, Green and Bolker2015; Kuznetsova et al., Reference Kuznetsova, Brockhoff and Christensen2017). Bootstrapped (n = 200) confidence intervals were computed for all beta estimates.

Results

Associations between SES and PGS and cognitive outcomes

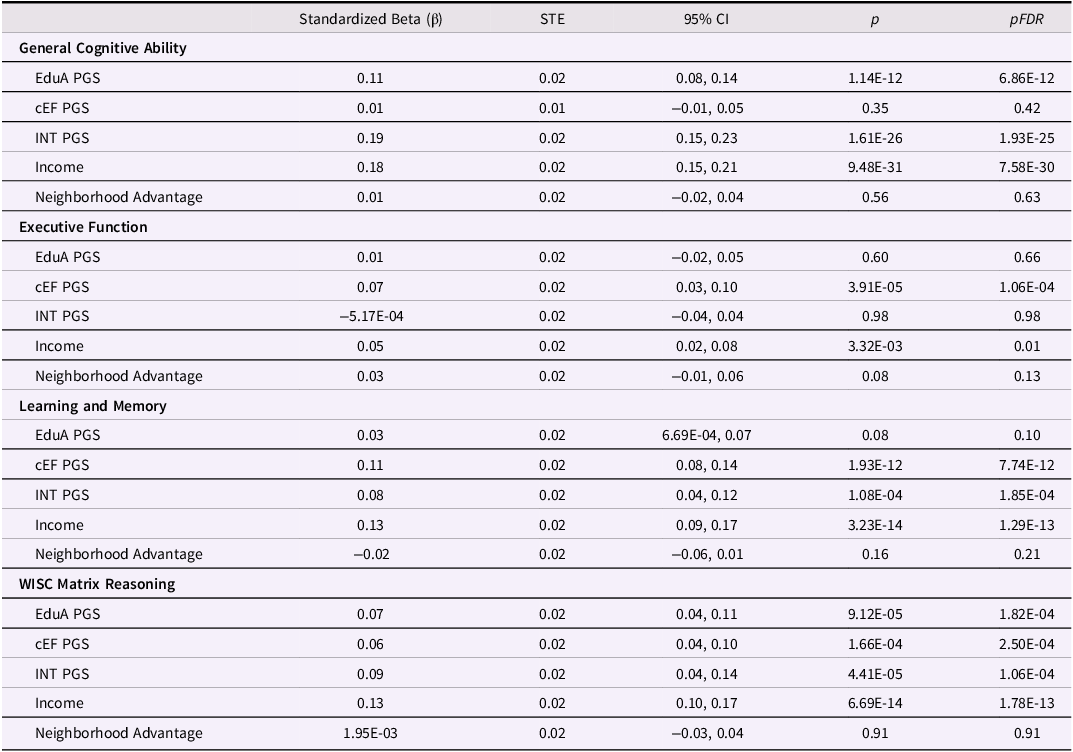

Family income was significantly and positively associated with cognitive performance across all four examined outcomes (Table 2 , Figure 1, (β) ≥ 0.05, ΔR 2 ≥ 4.00e-04, p ≤ 3.32e-03, p FDR ≤ 0.01), with the largest effect observed for general cognitive ability (β = 0.18, ΔR 2 = 0.031) and the smallest for executive function (β = 0.05, ΔR 2 = 4.00e-04). Neighborhood advantage, by contrast, showed no significant associations with cognitive outcomes (|β| ≤ 0.03, ΔR2 ≤ 1.60e-03, p ≥ 0.081) independent of family income.

Figure 1. Associations between PGS, family income, and neighborhood advantage and cognitive performance. Polygenic score (PGS) associations are shown in blue, and SES associations are shown in orange. Estimates are standardized betas, with 95% confidence intervals. Edu Attain = educational attainment; cEF = common executive function; PGS = polygenic score.

Table 2. Associations between PGS, family income, and neighborhood advantage and cognitive performance

PGS = Polygenic Score; EduA = educational attainment; cEF = common executive function; INT = intelligence. pFDR represents FDR-corrected p-values, separately for Income/Neighborhood Advantage (n = 8 tests) and the PGS (n = 12 tests).

EduA PGS was significantly and positively associated with general cognitive ability and matrix reasoning (β ≥ 0.07, ΔR 2 ≥ 3.73e-03, p ≤ 9.12e-05, p FDR ≤ 1.82e-04) but not with executive function or learning and memory (β ≤ 0.03, ΔR 2 ≤ 7.30e-04, p ≥ 0.08). cEF PGS was positively linked to executive function, learning and memory, and matrix reasoning performance (β ≥ 0.06, ΔR 2 ≥ 3.07e-03, p ≤ 1.66e-04, p FDR ≤ 2.50e-04) but not general cognitive ability (β = 0.01, ΔR 2 = 6.26e-05, p = 0.35). Intelligence PGS was positively associated with general cognitive ability, learning and memory, and matrix reasoning (β ≥ 0.08, ΔR 2 ≥ 2.94e-03, p ≤ 1.08e-04, p FDR ≤ 1.85e-04) but not executive function (β = –5.17e-04, ΔR 2 = –1.26e–5Footnote 2 , p = 0.98). Overall, except for cEF PGS, the largest effect sizes between income and PGS and cognition were observed for general cognitive ability, and the smallest for executive function (Figure 1). Significant income and PGS associations were comparable in effect size, with a one standard deviation increase in each linked to 0.05 – 0.19 standard deviation increases in cognitive ability.

Within-sibling results

In a reduced sample of siblings (n = 1,816, excluding singletons and 36 participants with within-family differences in neighborhood advantage values), intelligence PGS continued to predict general cognitive ability at both the between-family (β = 0.22, ΔR 2 = 0.020, p = 6.08-08, p FDR = 1.46e–07) and within-family (β = 0.06, ΔR 2 = 2.39e–03, p = 2.98–04, p FDR = 2.05e–03) levels (Table 3 , Figure 2). Between-family (β = 0.13, ΔR 2 = 8.09e–04, p = 3.42e–04, p FDR = 2.05e–03), but not within-family (β = 0.019, ΔR 2 = 2.95e–04, p = 0.23), EduA PGS was significantly associated with general cognitive ability. Similarly, between-family (β = 0.16, ΔR 2 = 0.021, p = 2.38e–06, p FDR = 2.86e–05), but not within-family (β = 0.026, ΔR 2 = 6.21e–04, p = 0.12), effects of cEF PGS were associated with learning and memory (Table 3, Figure 2). No other PGS associations were significant following false discovery rate correction (|β| ≤ 0.10, ΔR2 ≤ 5.42e-03, p ≥ 0.011, p FDR ≥ 0.052). Income remained significantly and positively associated with general cognitive ability, learning and memory, and matrix reasoning (β ≥ 0.11, ΔR 2 ≥ 7.80e–03, p ≤ 7.49e–03, p FDR ≤ 2.00–03; Table 3, Figure 2) but not with executive function (β = 0.037, ΔR 2 = –9.98e–04, p = 0.27; Table 3, Figure 2).

Figure 2. Between- and within-family PGS associations with cognition. Polygenic score (PGS) associations with cognition are decomposed into between- (blue) and within- (purple) family estimates; SES associations are shown in orange. Estimates are standardized betas, with 95% confidence intervals.

Table 3. Results for within-sibling analyses

PGS = Polygenic Score; EduA = educational attainment; cEF = common executive function; INT = intelligence. pFDR = FDR-corrected p-values, separately for Income/Neighborhood Advantage (n = 8 tests) and the PGS (n = 24 tests).

Interactions between SES and PGS

No interactions between SES (i.e., income, neighborhood advantage) and PGS (i.e., EduA, cEF, intelligence) were significant following FDR correction (|β| ≤ 0.03, ΔR 2 ≤ 7.52e–04, p ≥ 0.04, p FDR ≥ 0.39; Tables 4–7).

Table 4. Interactions between PGS & SES in models predicting general cognitive ability

PGS = Polygenic Score; EduA = educational attainment; cEF = common executive function; INT = intelligence. pFDR represents FDR correction across all interaction p-values, separately for each SES and PGS (e.g., 4 Income × EduA PGS, 4 Neighborhood Advantage × cEF PGS, etc).

Table 5. Interactions between PGS & SES in models predicting executive function

PGS = Polygenic Score; EduA = educational attainment; cEF = common executive function; INT = intelligence. pFDR represents FDR correction across all interaction p-values, separately for each SES and PGS (e.g., 4 Income × EduA PGS, 4 Neighborhood Advantage × cEF PGS, etc).

Table 6. Interactions between PGS & SES in models predicting learning and memory

PGS = Polygenic Score; EduA = educational attainment; cEF = common executive function; INT = intelligence. pFDR represents FDR correction across all interaction p-values, separately for each SES and PGS (e.g., 4 Income × EduA PGS, 4 Neighborhood Advantage × cEF PGS, etc).

Table 7. Interactions between PGS & SES in models predicting wisc matrix reasoning

PGS = Polygenic Score; EduA = educational attainment; cEF = common executive function; INT = intelligence. Betas are standardized. pFDR represents FDR correction across all interaction p-values, separately for each SES and PGS (e.g., 4 Income × EduA PGS, 4 Neighborhood Advantage × cEF PGS, etc).

Discussion

The present study had three aims: (a) test whether indicators of family and neighborhood socioeconomic status (SES) are independently associated with different aspects of cognitive ability in a large sample of youth, beyond contributions from polygenic scores (PGS) of educational attainment (EduA), intelligence (IQ), and common executive function (cEF); (b) test whether any significant PGS effects are attributable to between-family and/or within-family effects through within-siblings analyses; and (c) test whether SES moderates associations between PGS and cognitive outcomes. Broadly, family income, but not neighborhood advantage, and PGS were significantly and independently associated with cognitive abilities with similar effect sizes, with some variability across PGS indicators and cognitive outcome. Except for Intelligence PGS and general cognitive ability, no within-family PGS effects were detected. Finally, no significant interactions between SES and PGS were observed after correction for multiple comparisons. These findings provide further evidence for the importance of modifiable environmental factors and genetic influences in the development of cognitive abilities.

Concerning SES, family income was robustly associated with all cognitive outcomes, accounting for indicators of genetic propensity, whereas neighborhood advantage was not. The magnitude of the associations between income and each cognitive outcome was 1.18 to 2.17 times larger than most significant PGS associations with the same outcomes, with the exceptions of intelligence PGS and general cognitive ability and cEF PGS and executive function (1.06–1.40 times larger than income associations). Altogether, these results show that family income and estimates of genetic propensity for cognitive phenotypes derived from current GWAS in youth genetically similar to European reference populations show similar magnitudes of association with cognitive outcomes.

The lack of significant neighborhood advantage associations is not consistent with previous evidence of independent contributions of family SES and neighborhood resources (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Cooper, Jackson and Barch2020) and area deprivation (Park et al., Reference Park, Lee, Cho, Hwang, Kim, Kim, Joo and Cha2023) to cognition in the ABCD dataset or with other investigations of putative effects of neighborhood disadvantage on performance on various cognitive tasks (Kalb et al., Reference Kalb, Lieb, Ludwig, Peterson, Pritchard, Ng, Wexler and Jacobson2023; Wodtke, Ard, et al., Reference Wodtke, Ard, Bullock, White and Priem2022; Wodtke, Ramaj, et al., Reference Wodtke, Ramaj and Schachner2022). There are several potential explanations for this divergence. First, the variability of NAdv among Black participants in ABCD is greater than that among White participants (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Cooper, Jackson and Barch2020). Although race and genetic ancestry should not be conflated, it may be that the present study’s reliance on individuals most genetically similar to European reference populations may have truncated the variability in NAdv and thus the magnitude of association with cognitive outcomes. Further, Taylor and colleagues (Reference Taylor, Cooper, Jackson and Barch2020) utilized the full ABCD sample in analyses, so the present study in the smaller subsample may have simply been underpowered to detect such effects. Second, Taylor and colleagues (Reference Taylor, Cooper, Jackson and Barch2020) did not account for PGS in their analyses, possibly inflating income and neighborhood poverty estimates. Third, Park and colleagues (Reference Park, Lee, Cho, Hwang, Kim, Kim, Joo and Cha2023) used the area deprivation index rather than a latent neighborhood poverty factor like that in our analyses, and they did not appear to account for family relatedness. Other investigations did not account for family income as was done in the present study, possibly explaining our null findings relative to other investigations.

Similar to prior work (Judd et al., Reference Judd, Sauce, Wiedenhoeft, Tromp, Chaarani, Schliep, van Noort, Penttilä, Grimmer, Insensee, Becker, Banaschewski, Bokde, Quinlan, Desrivières, Flor, Grigis, Gowland, Heinz, Ittermann and Klingberg2020; Merz et al., Reference Merz, Strack, Hurtado, Vainik, Thomas, Evans and Khundrakpam2022; Park et al., Reference Park, Lee, Cho, Hwang, Kim, Kim, Joo and Cha2023; Peñaherrera-Aguirre et al., Reference Peñaherrera-Aguirre, Woodley, Sarraf and Beaver2022; Raffington et al., Reference Raffington, Czamara, Mohn, Falck, Schmoll, Heim, Binder and Shing2019), the present study found that EduA PGS was associated with cognitive ability. The largest effect found was for general cognitive ability and no significant association was detected for executive function, similar to Merz and colleagues (Reference Merz, Wiltshire and Noble2022), or for learning and memory. Building upon this literature, the current study found that intelligence PGS mirrored these associations, showing larger effects than EduA for general cognitive ability and matrix reasoning and also showing a significant association with learning and memory. PGS for common executive function (cEF) was associated with larger effects than the other PGS for executive function and learning and memory and was also associated with matrix reasoning. Altogether, these findings suggest that matrix reasoning is most broadly associated with estimates of genetic propensity toward cognitive ability and educational attainment and that executive function is the least strongly predicted by PGS overall and specifically linked to cEF PGS. These findings support the importance of examining multiple indicators of cognitive ability and genetic propensity to parse differences across cognitive domains.

In this study, results highlight that in middle childhood both income and genetic propensity are independently associated with both relatively stable cognitive abilities (e.g., fluid intelligence and IQ) as well as those that undergo substantial development through adolescence (e.g., EF). More explicitly, each cognitive domain examined (i.e., general ability, fluid intelligence, executive function, learning/memory) has varying trajectories of development from middle childhood through adulthood (Diamond, Reference Diamond2006, Reference Diamond2013; Ferrer et al., Reference Ferrer, O’Hare and Bunge2009; Greiff et al., Reference Greiff, Wüstenberg, Goetz, Vainikainen, Hautamäki and Bornstein2015; McKean et al., Reference McKean, Mensah, Eadie, Bavin, Bretherton, Cini and Reilly2015; Petscher et al., Reference Petscher, Justice and Hogan2018). Despite stability differences between domains there is ample evidence that adolescent cognitive ability strongly predicts ability across the lifespan (Icenogle et al., Reference Icenogle, Steinberg, Duell, Chein, Chang, Chaudhary, Di Giunta, Dodge, Fanti, Lansford, Oburu, Pastorelli, Skinner, Sorbring, Tapanya, Uribe Tirado, Alampay, Al-Hassan, Takash and Bacchini2019), and that adolescent cognitive ability may mediate associations between early-life SES and later-life cognition (Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Chen, Wang and Zhou2019), underscoring the importance of examining relationships between income, genetic propensity, and cognition in adolescence. Moreover, there is evidence that the same genes are associated with domains of cognition throughout the lifespan and that cognitive ability at different ages is genetically correlated (Haworth et al., Reference Haworth, Wright, Luciano, Martin, de Geus, van Beijsterveldt, Bartels, Posthuma, Boomsma, Davis, Kovas, Corley, Defries, Hewitt, Olson, Rhea, Wadsworth, Iacono, McGue, Thompson and Plomin2010; Mollon et al., Reference Mollon, Knowles, Mathias, Gur, Peralta, Weiner, Robinson, Gur, Blangero, Almasy and Glahn2021; Trzaskowski, Yang, et al., Reference Trzaskowski, Yang, Visscher and Plomin2014). Altogether, although some change may occur due to increasing heritability of cognition over the lifespan (Mollon et al., Reference Mollon, Knowles, Mathias, Gur, Peralta, Weiner, Robinson, Gur, Blangero, Almasy and Glahn2018, Trzaskowski et al., Reference Trzaskowski, Harlaar, Arden, Krapohl, Rimfeld, McMillan, Dale and Plomin2014) and increasing correlation between genetic influences and specific measured environments, the effects presented here can be generally expected to persist and likely increase in magnitude into adolescence and young adulthood.

Notably, results of the within-siblings analyses suggested that most of these significant PGS associations were attributable to between-family, but not within-family, variability in PGS. That is, accounting for the family PGS means, individual-level PGS for EduA was not associated with general cognitive ability or matrix reasoning, nor was individual-level intelligence PGS with learning and memory or matrix reasoning or cEF PGS with executive function or learning and memory. In these cases, the observed PGS effects may be attributable to population stratification, assortative mating, or passive gene-environment correlation, rather than to direct genetic effects (Selzam et al., Reference Selzam, Ritchie, Pingault, Reynolds, O’Reilly and Plomin2019). Both between- and within-family PGS effects were detected for intelligence PGS in association with general cognitive ability, with the between-family PGS association being approximately four times larger than the within-family PGS association. These findings converge with prior work showing that, particularly for cognitive phenotypes, between-family PGS effects eclipse within-family PGS effects (e.g., Okbay et al., Reference Okbay, Wu, Wang, Jayashankar, Bennett, Nehzati, Sidorenko, Kweon, Goldman, Gjorgjieva, Jiang, Hicks, Tian, Hinds, Ahlskog, Magnusson, Oskarsson, Hayward, Campbell and Young2022; Selzam et al., Reference Selzam, Ritchie, Pingault, Reynolds, O’Reilly and Plomin2019). Shared environment has been shown to capture a particularly large amount of variability in phenotypes such as IQ and educational attainment, relative to some physical and mental health phenotypes, suggesting that PGS of IQ and EduA may be especially confounded by gene-environment correlation (Polderman et al., Reference Polderman, Benyamin, De Leeuw, Sullivan, Van Bochoven, Visscher and Posthuma2015; Selzam et al., Reference Selzam, Ritchie, Pingault, Reynolds, O’Reilly and Plomin2019).

The hypothesis that SES may moderate the effect of genetic propensity on cognitive outcomes was not supported by the present data. Although inconsistent, particularly across countries, much of the evidence for what has been named the Scarr-Rowe hypothesis has come from twin studies showing that SES moderates the heritability of cognitive ability (e.g., Reference Bates, Lewis and WeissT. C. Bates et al., Reference Bates, Lewis and Weiss2013; Harden et al., Reference Harden, Turkheimer and Loehlin2007; Rowe et al., Reference Rowe, Jacobson and Van den Oord1999; Tucker-Drob et al., Reference Tucker-Drob, Rhemtulla, Harden, Turkheimer and Fask2011; Turkheimer et al., Reference Turkheimer, Haley, Waldron, D’Onofrio and Gottesman2003). Using polygenic scores allows this hypothesis to be tested among singletons as well as twins and overcomes the erroneous (in this case) twin assumption that there is no covariance between additive genetic and shared environmental influences on a trait. At the same time, the variance explained by PGS is substantially less than heritability estimates and does not fully capture an individual’s full genetic propensity. Further, interactions in general, and in particular those involving potentially noisy measures, such as polygenic scores, are often quite small and difficult to detect (e.g., Vize et al., Reference Vize, Baranger, Finsaas, Goldstein, Olino and Lynam2023). The present findings align with some prior research estimating interactions between PGS and SES in association with cognitive ability (e.g., Merz et al., Reference Merz, Strack, Hurtado, Vainik, Thomas, Evans and Khundrakpam2022; von Stumm et al., Reference von Stumm, Malanchini and Fisher2023), including in the ABCD sample (e.g., Judd et al., Reference Judd, Sauce, Wiedenhoeft, Tromp, Chaarani, Schliep, van Noort, Penttilä, Grimmer, Insensee, Becker, Banaschewski, Bokde, Quinlan, Desrivières, Flor, Grigis, Gowland, Heinz, Ittermann and Klingberg2020), but contrasts other work detecting PGS-by-SES interactions, also using the ABCD sample (e.g., Peñaherrera-Aguirre et al., Reference Peñaherrera-Aguirre, Woodley, Sarraf and Beaver2022). The latter study was limited by analyses that used different genotype quality control standards and did not correct for multiple testing in assessing statistical significance of the interactions. Overall, these results contribute to a complicated literature by showing that, in a large sample of children from across the U.S. who are genetically similar to European reference populations, genetic influences on cognition derived from three GWAS of aspects of cognition are not moderated by childhood family SES or neighborhood poverty across a range of cognitive measures.

Strengths of this study include the large sample size; the decomposition of polygenic score variance into between- and within-family variance to better account for potentially confounding influences of population stratification, assortative mating, and or passive gene-environment correlation; and the use of both family- and neighborhood-level SES, multiple polygenic scores, and multiple cognitive outcomes. Further, by leveraging genome-wide data and measured SES, we were able to estimate the independent effect of SES on cognitive abilities, accounting for genetic influences on cognition that may share variance with SES.

Limitations to the present study should be considered in interpreting the results. First, our sample is restricted to individuals most genetically similar to reference populations from Europe. Given the intersectionality between SES and race (which is correlated with but distinct from ancestral background) alongside typically higher levels of both familial and neighborhood poverty among BIPOC populations, our findings may not generalize to all ancestral backgrounds or racial groups. There is a dearth of well-powered GWAS of cognitive phenotypes in individuals with less genetic similarity to European reference populations, precluding the estimate of PGS in these groups in ABCD, but the exclusion of these individuals from research on this topic is a major limitation. Second, polygenic scores include information only from common genetic variants, and thus, in conjunction with the still-limited power of PGS to explain the common variant heritability, are underestimates of the true genetic effect on cognition. Further, rare genetic variants and de novo mutations not incorporated into the PGS may interact with SES (Ganna et al., Reference Ganna, Genovese, Howrigan, Byrnes, Kurki, Zekavat, Whelan, Kals, Nivard, Bloemendal, Bloom, Goldstein, Poterba, Seed, Handsaker, Natarajan, Mägi, Gage, Robinson and Neale2016; Rask-Andersen et al., Reference Rask-Andersen, Karlsson, Ek and Johansson2021), and our approach was not able to account for this possibility.

Third, the data used in this study are cross-sectional due to the availability of certain cognitive tasks at baseline but not follow-up waves of ABCD (Luciana et al., Reference Luciana, Bjork, Nagel, Barch, Gonzalez, Nixon and Banich2018; Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Barch, Bjork, Gonzalez, Nagel, Nixon and Luciana2019). Prior work examining specific cognitive measures in ABCD suggested that despite age-related change, there is considerable stability in individual differences of cognitive performance from ages 9–10 to 11–12 (Anokhin et al., Reference Anokhin, Luciana, Banich, Barch, Bjork, Gonzalez, Gonzalez, Haist, Jacobus, Lisdahl, McGlade, McCandliss, Nagel, Nixon, Tapert, Kennedy and Thompson2022). Here, we were interested in broad cognitive constructs that mapped most closely onto the GWAS used for our PGS, and because these broader cognitive components can only be computed at one time point, we were restricted to baseline cognitive and SES data. The nascent literature indicates that early life and sustained exposure to poverty has differential associations with cognition relative to those with more transient or later development poverty (Brooks-Gunn & Duncan, Reference Brooks-Gunn and Duncan1997; Korenman et al., Reference Korenman, Miller and Sjaastad1995; Najman et al., Reference Najman, Hayatbakhsh, Heron, Bor, O’Callaghan and Williams2009; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network, 2005), and thus it is unclear whether the effects associated with SES in this study reflect persistent or temporally limited relationships. Given possible changes in SES and in the strength of associations between polygenic propensity and SES and cognitive ability over the lifespan (Brooks-Gunn & Duncan, Reference Brooks-Gunn and Duncan1997; Korenman et al., Reference Korenman, Miller and Sjaastad1995; Najman et al., Reference Najman, Hayatbakhsh, Heron, Bor, O’Callaghan and Williams2009; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network, 2005), it will be important for future work to whether changes in SES are associated with changes in cognitive ability accounting for, or in interaction with, polygenic propensity.

wFourth, the observed associations were relatively small in effect (β ≤ 0.193, R 2 ≤ 0.031 in primary analyses), suggesting that large proportions of variance in the cognitive abilities examined are still unexplained. Other influences, including but not limited to maternal exposure to adversity and stress effects on the fetus, caregiver and child stress, mental health, parenting behavior, cognitive stimulation in the home, nutritional deprivation, greater exposure to environmental toxins, and parent genetic variants for cognition that were not passed to their children but shaped their cognitive environment, are also important factors to consider (See reviews: Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Riis and Noble2016; Merz et al., Reference Merz, Wiltshire and Noble2019; Pace et al., Reference Pace, Luo, Hirsh-Pasek and Golinkoff2017; Perkins et al., Reference Perkins, Finegood and Swain2013). Each of these aforementioned factors (e.g., household stress, increased risk of mental health diagnoses, parental behaviors) are correlated with childhood poverty and are potential environmental mechanisms linking childhood poverty with adverse outcomes, including lower performance on cognitive measures. Future work may address some of these limitations through the incorporation of parental cognitive performance measures, in addition to measures of other influences that may shape child cognition and cognitive environment. Fifth, the inclusion of PGS and heritable environmental factors (e.g., SES) in the same regression can create spurious associations (Akimova et al., Reference Akimova, Breen, Brazel and Mills2021). In that case, the effect of the environment should increase, while the effect of genetics should decrease. We did not find this to be the case in our models, suggesting that the associations we observed are not spurious or driven by conditioning on a collider. Relatedly, prior work shows that gene × environment interactions may be inflated in the case of gene-environment correlations (Akimova et al., Reference Akimova, Breen, Brazel and Mills2021; Kazma et al., Reference Kazma, Babron and Génin2011; Lindström et al., Reference Lindström, Yen, Spiegelman and Kraft2009). Because we did not detect any significant interactions, we do not believe this is a concern in our analyses.

Broadly, this study extends prior work by examining multiple SES, PGS, and cognitive outcomes and testing whether PGS associations may be attributable to direct genetic effects or, rather, are confounded. We show that the PGS effects are largely confounded (e.g., by population stratification, assortative mating, and/or gene-environment correlation) and are smaller than the effects observed for family income. These findings highlight the unique importance of a modifiable environmental factor, SES, to childhood cognitive ability and lend further empirical support to those investigating the effects of interventions designed to alleviate childhood poverty, such as direct payments designed to increase family financial stability and enhance child cognitive and psychosocial functioning (Rojas et al., Reference Rojas, Yoshikawa, Gennetian, Rangel, Melvin, Noble, Duncan and Magunson2020). This work emphasizes the continued need for public policy solutions to the problem of childhood poverty. Future work is needed to examine mechanisms through which genes and SES may influence cognitive ability (e.g., brain structure, stress, physical and mental health), which may also hold implications for intervention efforts and local and federal policy aimed at reducing child poverty and its sequelae.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579424001573.

Author contributions

S.E. Paul and N.M. Elsayed contributed equally to this work. A.S. Hatoum and D.M. Barch share senior authorship.

Funding statement

Data for this study were provided by the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study, which was funded by awards U01DA041022, U01DA041025, U01DA041028, U01DA041048, U01DA041089, U01DA041093, U01DA041106, U01DA041117, U01DA041120, U01DA041134, U01DA041148, U01DA041156, U01DA041174, U24DA041123, and U24DA041147 from the NIH and additional federal partners (https://abcdstudy.org/federal-partners.html). This work was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism ((SEP, F31AA029934), (ASH, K01 AA030083)), the National Institute on Drug Abuse, ((RB R01 DA054750), (DMB, U01DA041120)), and the National Science Foundation ((NME, NSF DGE-1745038), (SMCC, NSF SGE-1842169)).

Competing interests

None.