Introduction

In 2015, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were approved by 193 Member States of the United Nations (UN, 2022). Among these goals, SDG target 3.8 focuses on achieving universal health coverage (UHC), including financial protection, access to quality essential healthcare services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all people by 2030. The financial hardship caused by high out-of-pocket (OOP) health spending is a major obstacle on the road to achieve UHC. According to the World Health Organization, about 100 million people are pushed into extreme poverty each year because of OOP health expenditures, which highlights the importance of financial protection for achieving UHC by 2030 (WHO, 2022).

In order to monitor the progress toward achieving UHC, WHO recommend an indicator, catastrophic health expenditure (CHE), defined as OOP health payments exceeding a special threshold of a household’s ability to pay for healthcare (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Evans, Kawabata, Zeramdini, Klavus and Murray2003). CHE means that the OOP health payments are so high that households have to reduce their basic expending (Sui et al., Reference Sui, Zeng, Tan, Tao, Liu, Liu, Ma, Huang and Yu2020). According to an observational study, the global incidence of CHE in 2000, 2005 and 2010 were estimated as 9.7%, 11.4% and 11.7%, respectively (Wagstaff et al., Reference Wagstaff, Flores, Hsu, Smitz, Chepynoga, Buisman, van Wilgenburg and Eozenou2018). A study using nationally representative data in China revealed that the incidence of CHE declined from 14.7% in 2010 to 8.7% in 2018 (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Liu, Nicholas and Wang2021). A series of studies indicated that the older people had a higher risk of CHE. Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Liu, Nicholas and Wang2021) found that household members aged 50–64 years were 2.09 times and those aged ≥65 years were 1.61 times more likely to incur CHE than those aged 16–24 years. Similarly, a study conducted in Kenya reported that compared with household head aged <25 years, those aged 25–34 (odds ratio [OR] = 1.30, 95% confident interval [CI]: 1.05–1.62), 35–44 (OR = 1.50, 95% CI: 1.08–2.08), 45–54 (OR = 1.88, 95% CI: 1.31–2.71), and ≥55 (OR = 1.72, 95% CI: 1.15–2.58) years were more likely to incur CHE (Barasa et al., Reference Barasa, Maina and Ravishankar2017). Hence, there are a number of people still facing financial hardship for OOP health spending, especially older people.

Depression is an increasingly common mental problem all over the world. According to the Global Burden of Disease Study, the number of disability adjusted of life years (DALYs) of depression increased 61.1% (95% uncertain interval: 56.9–65.0) in all ages from 1990 to 2019 (GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators, 2020). The prevalence of depression varies considerably across different subpopulation, severity grades, countries and diagnostic criteria, but the 12-month prevalence of major depressive disorder was approximately 6.0% overall, and the prevalence of any depression was 4.2% for ICD-10 in older adults (Kessler and Bromet, Reference Kessler and Bromet2013; Sjöberg et al., Reference Sjöberg, Karlsson, Atti, Skoog, Fratiglioni and Wang2017). Some studies reported that compared with older adults, the prevalence of major depressive disorder was two times higher in younger adults (Hasin et al., Reference Hasin, Sarvet, Meyers, Saha, Ruan, Stohl and Grant2018; Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas and Walters2005). However, the impact caused by depression in older population may be worse than in younger population because of the existence of comorbidities and other reasons (Alexopoulos, Reference Alexopoulos2005; Read et al., Reference Read, Sharpe, Modini and Dear2017). The significant association of depression with cognitive impairment was revealed in the older population by a lot of studies (Shimada et al., Reference Shimada, Park, Makizako, Doi, Lee and Suzuki2014; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Ma and Wang2021). Besides, depression has a robust connect with cardiovascular disease (CVD) incidence, severity and outcomes. Current studies indicated that compared with people without depression, those with depression had an increased risk of CVD incident, myocardial infarction and CVD mortality (Meng et al., Reference Meng, Yu, Liu, He, Lv, Guo, Bian, Yang, Chen, Zhang, Chen, Wu, Pan and Li2020; Rajan et al., Reference Rajan, McKee, Rangarajan, Bangdiwala, Rosengren, Gupta, Kutty, Wielgosz, Lear, AlHabib, Co, Lopez-Jaramillo, Avezum, Seron, Oguz, Kruger, Diaz, Nafiza, Chifamba, Yeates, Kelishadi, Sharief, Szuba, Khatib, Rahman, Iqbal, Bo, Yibing, Wei and Yusuf2020). The DALYs of depression for people aged 50–74 years was nearly 5.2 times than for those aged 10–24 years and 2.0 times than for those aged 25–49 years in 2019 (GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators, 2020). Therefore, depression is a pending and crucial issue in the elderly.

Risk factors of depression include social, psychological and biological factors, as well as their interactions (Heim and Binder, Reference Heim and Binder2012; Malhi and Mann, Reference Malhi and Mann2018). Because of physiological differences, older people are more vulnerable to incur depression than younger people. Ageing-related and disease-related processes, including arteriosclerosis and inflammatory, endocrine and immune changes, comprise the function of brain and increase the vulnerability to depression among the elderly (Alexopoulos, Reference Alexopoulos2005). Furthermore, psychosocial adversity, like economic impoverishment, changes the physiological performance and intensifies the susceptibility to depression in older people with poor socioeconomic status (Alexopoulos, Reference Alexopoulos2005; Langer et al., Reference Langer, Crockett, Bravo-Contreras, Carrillo-Naipayan, Chaura-Marió, Gómez-Curumilla, Henríquez-Pacheco, Vergara, Santander, Antúnez and Baader2022). Obviously, CHE is just one form of psychosocial adversity, which pushes household into poverty and financial pressure. Hence, there may be a correlation between CHE and depression in the elderly. Nevertheless, current studies about the outcomes of CHE mostly concentrated on the economic influence, such as the countermeasures for coping with high costs of OOP health spending but rarely on the mental health of family members (Kasahun et al., Reference Kasahun, Gebretekle, Hailemichael, Woldemariam and Fenta2020).

Our study used all waves (2011, 2013, 2015, and 2018) data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), which collected data from socioeconomic status to self-health condition among people aged ≥45 years, in order to analyze the association of CHE with long-dated depression among middle-aged and old people. In this way, our study was the first one focusing on the relationship between CHE and the risk of depression in middle-aged and elderly population of China.

Methods

Study design and participants

Data in this study were obtained from the nationally representative database (CHARLS), which is implemented by the National School of Development of Peking University to collect social, economic and health circumstances among individuals aged ≥45 years and their spouses/partners via face-to-face interviews with structured questionnaires (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Hu, Smith, Strauss and Yang2014). Considering sample lost to follow-up and the long-time investigation, CHARLS included some people aged <45 years if they meet the inclusion criteria as reserved sample. The baseline survey was conducted between June 2011 and March 2012 among participants who were selected by multistage stratified probability-proportionate-to-size sampling in 150 counties of 28 provinces in China, and CHARLS respondents were followed every 2 years. All data were available to be downloaded from CHARLS official website (http://charls.pku.edu.cn/). The CHARLS was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Review Committee of Peking University (IRB00001052-11015).

Our study used longitudinal data from all waves (2011, 2013, 2015 and 2018) of CHARLS. Baseline survey included 17,708 individuals with valid interview responses. Participants who aged <45 years (n = 415), had missing data of depression symptoms at baseline (n = 1607), had depression at baseline (n = 5816), were lost to follow-up (n = 1254), died during follow-up without information of depression (n = 47), had missing data of baseline characteristics (n = 53) and had missing data of depression at the end of follow-up (n = 580) were excluded. Besides, 2171 participants not the main respondents of households, who were selected randomly among those participants meeting the inclusion criteria, were excluded. Finally, a total of 5765 individuals (main respondents) were included in this study (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of the study population.

Catastrophic health expenditure

The head of the household was identified as the main respondents in our study. The household OOP medical expenditure was measured as the self-paid medical expenditure (excluding reimbursed expenses, including the expenditure paid by household members) of outpatient services, inpatient services and self-treatment medicine of respondents and their spouses/partners in the past 12 months. The yearly household food expenditure was estimated by the weekly meal expenses collected from the questionnaire, and the total household expenditure in the past 12 months was calculated as the sum of monthly daily expenditures (food, transportation, communication and so on) multiplied by 12 plus yearly special expenditures (heating, medical care, clothing, education and so on).

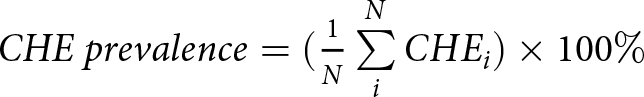

Household who incurred CHE was defined as household OOP medical expenditure that exceeded 40% of a household’s capacity to pay (defined as total household expenditure minus household food expenditure) (Cylus et al., Reference Cylus, Thomson and Evetovits2018). CHE prevalence at baseline was measured as the percentage of the number of household heads incurring CHE to total participants. The formula was  $CHE\ prevalence = ({1 \over N}\mathop \sum \limits_i^N CH{E_i}) \times 100\% $, where N is the total number of participants, CHEi is 1 when the ith household occurred CHE, and 0 otherwise.

$CHE\ prevalence = ({1 \over N}\mathop \sum \limits_i^N CH{E_i}) \times 100\% $, where N is the total number of participants, CHEi is 1 when the ith household occurred CHE, and 0 otherwise.

Depression

Depression was measured by the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), which is a shortened version of the original 20-item CES-D (Table S1) (Andresen et al., Reference Andresen, Malmgren, Carter and Patrick1994). CES-D was not designed as a diagnostic tool but was widely used to identify individuals at high risk of depression in the general population and various subpopulations (Smarr and Keefer, Reference Smarr and Keefer2020). The score of each item in the 10-item CES-D, as same as the 20-item CES-D, ranges from 0 to 3 according to the answer of ‘how often you felt this symptom during the past week’, where 0 = rarely or none of the time (<1 day), 1 = some or a little of time (1–2 days), 2 = occasionally or a moderate amount of time (3–4 days) and 3 = most or all of the time (5–7 days) (Smarr and Keefer, Reference Smarr and Keefer2020). The score of the 10-item CES-D ranges from 0 to 30, and total score ≥10 is recommended as a cutoff for depression (Andresen et al., Reference Andresen, Malmgren, Carter and Patrick1994).

Covariates

Covariates in this study include demographic characteristics: gender (men and women), age group (45–54, 55–64 and ≥65), marital status (married/partnered and other), education (illiterate/semiliterate, primary school, middle school, high school and above), medical insurance (without any insurance, urban employee basic medical insurance [UEBMI], urban resident basic medical insurance [URBMI], new rural cooperative medical scheme [NRCMS] and other); health-related characteristics: chronic diseases (yes and no), body mass index ([BMI]; normal, lower, overweight and obesity), outpatient services (yes and no), inpatient services (yes and no), smoking status (smoked, smoking and never) and current drinking (yes and no); socioeconomic characteristics: residence (urban and rural), family economic level (four classes), family size (1–2, 3–4 and ≥5) and economic development level (four classes).

The family economic level was classified by the quartiles of household annual income (lowest: <4000 yuan; lower: 4000–16,799 yuan; higher: 16,800–38,399 yuan; highest: ≥38,400 yuan). Similarly, the economic development level was identified by the quartiles of 2011 per capita gross regional product (lowest: <27,250 yuan; lower: 27,250–33,231 yuan; higher: 33,232–48,200 yuan; highest: ≥48,201 yuan), which were obtained from the 2011 China Statistical Yearbook (National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China, 2011).

Statistics analysis

This study used mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables or frequencies and percentages for categorical variables to describe the baseline characteristics of participants. The Pearson χ 2 test was employed to compare distribution of CHE according to different baseline characteristics. We applied a multivariate logistical regression model to analyze the determinants of CHE.

To analyze the association of CHE with the risk of depression, we first calculated the unadjusted incidence rates (number of events divided by accumulated person-month) during follow-up time (described by median and interquartile range [IQR]). Second, we used Cox proportional hazard regression models to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs of depression among participants with CHE, compared with those without CHE.

We did four sensitivity analyses to evaluate the robustness of our estimations. First, we established three multivariate Cox proportional hazard models adjusted for different confounding factors. In model 1, we adjusted demographic characteristics, including gender, age group, marital status, education and insurance. Model 2 further contained health-related characteristics, including chronic diseases, BMI, outpatient services, inpatient services, smoking status and current drinking. In model 3 (final fully adjusted model), in addition to those factors included in model 2, we also adjusted socioeconomic characteristics, including residence, family economic level, family size and economic development level. Second, we transferred the categorical variables age group and family economic level into continuous variables and conducted the same analysis in the final model. Third, we used the threshold of 25% for the definition of CHE in the final model. Fourth, we changed the original main respondents of households with two eligible respondents to the 2171 excluded participants in the final model.

To explore the differential effect in population groups, we did subgroup analyses stratified by gender, age group, insurance, chronic diseases, residence, economic development level and family economic level, using the same model but with the stratification variable removed.

All of the data were analyzed in R 4.2.1 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria). Two-side P value less than 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 5765 participants were enrolled in this study, of which 3080 (53.4%) were male. The mean (SD) age was 58.8 (9.4) years old. A total of 5044 (87.5%) participants were married/partnered, 4162 (72.2%) participants had NRCMS and 2318 (40.2%) participants had an education level of illiterate/semiliterate (Table 1).

Table 1. Distribution of CHE events according to baseline characteristics

* P < 0.05

Catastrophic health expenditure

Among 5765 participants, the prevalence of CHE was 19.24%. The distribution of CHE prevalence by province at baseline was shown in Figure 2. Heilongjiang, Jilin, Liaoning, Henan, Hubei, Chongqing, Sichuan and Xinjiang had higher CHE prevalence than other provinces.

Figure 2. Distribution of catastrophic health expenditure prevalence among middle-aged and old participants at baseline by province.

As the results of chi-square test and logistical regression analysis revealed (Table 1 and Table S2), male participants, participants aged 55–64 years, who were married/partnered, with chronic diseases, with outpatient services, with inpatient services and with lower and highest economic development level had higher prevalence of CHE than the reference group (all P < 0.05). Moreover, those with family size of 3–4 and lower and higher family economic level were less likely to experience CHE than others (all P < 0.05).

Risk of depression

During the median 50 (IQR: 25–84) person-month of follow-up, 2379 of 5675 participants developed depression, of which 1873 people had no CHE and 506 people had CHE. The incidence rate of depression among participants with CHE (8.00 per 1000 person-month) was higher than those without CHE (6.81 per 1000 person-month, P = 0.001, Table 2). In the unadjusted analysis, participants with CHE had an 18% higher risk of depression than those without CHE (crude hazard ratio = 1.18, 95% CI: 1.07–1.30). In the multivariate analysis, fully adjusted for demographic characteristics, health-related characteristics and socioeconomic characteristics, compared with participants without CHE, those with CHE had a 13% increased risk of depression (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] = 1.13, 95% CI: 1.02–1.26, Table 2).

Table 2. Association of CHE with risk of depression in univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard models

a Adjusted for demographic characteristics (gender, age group, education, marital status and insurance), health-related characteristics (smoking status, drinking, chronic disease, body mass index, outpatient and inpatient services) and socioeconomic characteristics (residence, family economic level, family size and economic development level).

In the sensitivity analyses, the significant association of CHE with risk of depression was stable in multivariate models adjusted for only demographic characteristics or further adjusted for health-related characteristics, or in model where the categorical variables age group and family economic level were transferred to continuous variables, or in model where the threshold of CHE definition was changed into 25%, or in model where the originally selected main respondents from households with two eligible respondents were replaced by the excluded ones (Table S3).

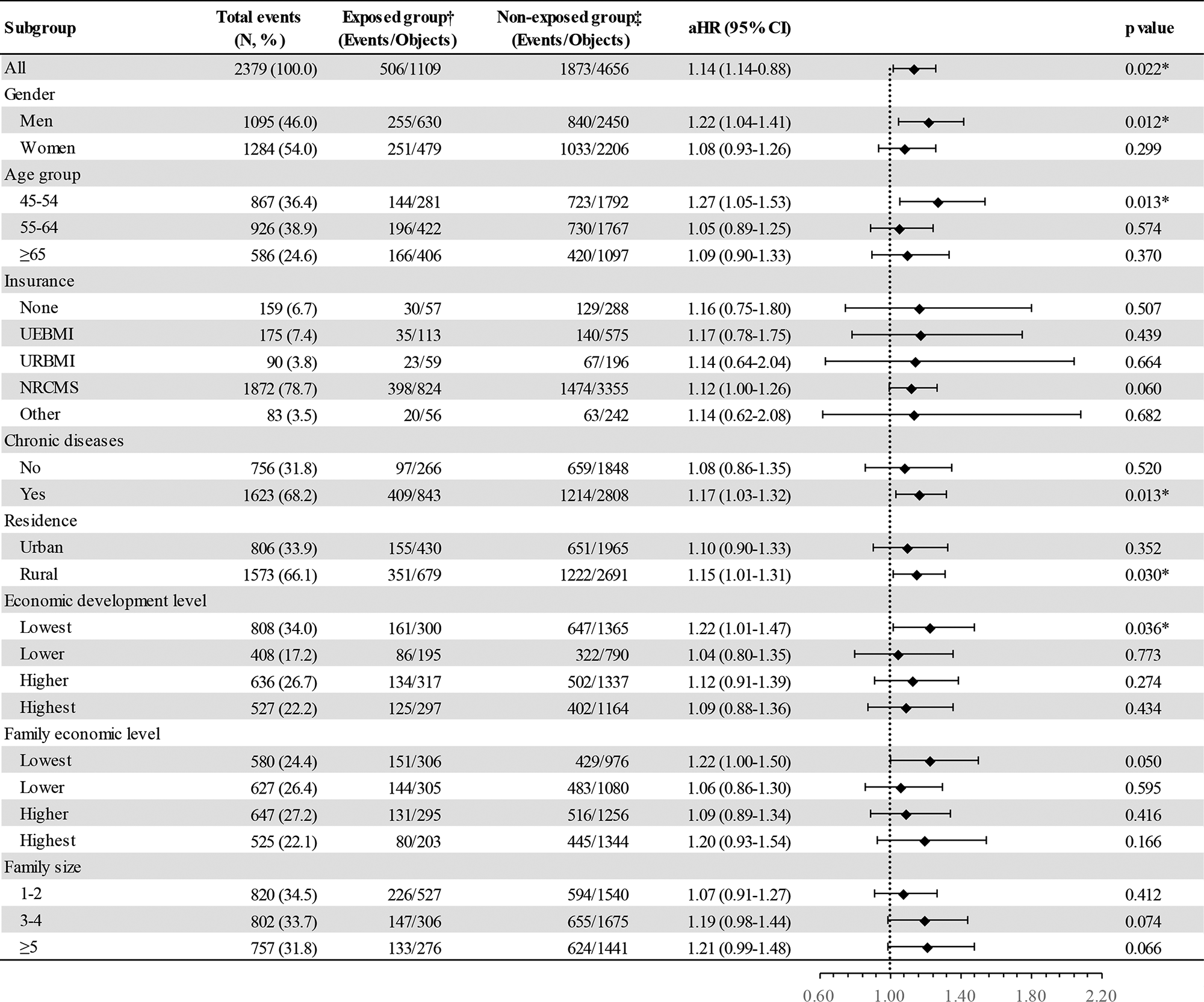

Subgroup analysis

The subgroup analysis was stratified by gender, age group, insurance, chronic diseases, residence, economic development level, family economic level and family size using the same model but with the stratification variable removed. The association of CHE with risk of depression was significant in male participants and in participants of younger age, with chronic diseases, living in rural areas, and with lowest economic development level (all P < 0.05, Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Subgroup analysis of the association between catastrophic health expenditure and the risk of depression.

Discussions

With ageing, people are more likely to develop physical comorbidities and neurodegenerative diseases (Niccoli and Partridge, Reference Niccoli and Partridge2012), leading to a great amount of OOP health expending and pushing household into financial hardship, which may intensify the susceptibility to depression in middle-aged and old people (Alexopoulos, Reference Alexopoulos2005; Langer et al., Reference Langer, Crockett, Bravo-Contreras, Carrillo-Naipayan, Chaura-Marió, Gómez-Curumilla, Henríquez-Pacheco, Vergara, Santander, Antúnez and Baader2022). Therefore, in order to achieve UHC by 2030 and prevent depression among middle-aged and old people, exploring the association of CHE with depression is really urgent. Our study is the first one to explore the impact of CHE on long-dated depression in the middle-aged and old population in China. We found that participants with older age, married/partnered, chronic diseases, outpatient services, inpatient services, lower and highest economic development level had higher prevalence of CHE than others, and CHE had a negative impact on depression episode. More economic interventions on the incidence of depression need to be implemented and intensified.

Our study found that the CHE prevalence of participants was 19.24%, which was higher than in the general population in China in the same period (14.7% in 2010) (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Liu, Nicholas and Wang2021). Moreover, according to other studies, participants with older age, married/partnered, chronic diseases, outpatient services, inpatient services, lower and highest economic development level had higher prevalence of CHE than others (Atake and Amendah, Reference Atake and Amendah2018; Njagi et al., Reference Njagi, Arsenijevic and Groot2018). Obviously, due to a decline of physical function, age-related diseases in middle-aged and old people are more and more prevalent, increasing the frequency of accessing to outpatient and inpatient care, which leads to a high OOP health expense (Jaul and Barron, Reference Jaul and Barron2017; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Atun, Oldenburg, McPake, Tang, Mercer, Cowling, Sum, Qin and Lee2020). A number of studies revealed that compared with younger participants, the incidence of CHE can be two times higher in older participants (Khan et al., Reference Khan, Ahmed and Evans2017; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Liu, Nicholas and Wang2021). As for the reasons that participants with higher economic development level were more likely to incur CHE than those with lowest economic development level, it may be that the diagnostic technology of most illnesses is experienced in high economic growth areas. In addition, people in rapid economic development areas may be paid more attention to early detection of diseases and other preventive healthcare services (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Zhang, Wang, Tan, Bai and Liu2020). Hence, in order to eliminate CHE and further reduce the effects caused by CHE, we should promote health education to primary prevention of illnesses and enhance the financial protection of chronic diseases for those who have to go to see a doctor frequently.

Results of this study revealed that middle-aged and old people with CHE had a 13% increased risk of depression than those without CHE (aHR = 1.13, 95% CI: 1.02-1.26). CHE, a form of financial hardship, as well as a kind of psychosocial adversity, is caused by high costs of OOP health services and forces family to cut short basic expenditure, increasing the vulnerability of depression among middle-aged and old individuals (Alexopoulos, Reference Alexopoulos2005). The first point, in order to cut off the linkage of CHE and depression, is preventing the incidence of CHE. As discussed above, first of all, health promotion needs to be on the key position for reducing OOP health expenditure directly. Zhao et al. (Reference Zhao, Atun, Oldenburg, McPake, Tang, Mercer, Cowling, Sum, Qin and Lee2020) found that a higher number of chronic diseases was associated with increased likelihood of CHE (aHR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.26–1.32). Second, comprehensive financial protection, like medical insurance, should be intensified and expanded in all population, especially in those who have special diseases with high medical costs. Most studies about CHE concentrated in a subset of diseases, such as cancers, chronic diseases, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and tuberculosis because of their unaffordable medical costs (Assebe et al., Reference Assebe, Negussie, Jbaily, Tolla and Johansson2020; Jung et al., Reference Jung, Kwon and Noh2022; Njagi et al., Reference Njagi, Arsenijevic and Groot2018; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Shi, Fu, Zhang, Liu, Chen and He2021). Moreover, to reduce the medical costs of these diseases, for example, China has launched catastrophic medical insurance (critical illness insurance) in 2012 and implemented nationwide in 2016 after city-based testing, which aimed to reimburse patients whose OOP health expenditure exceeded a predetermined basic medical insurance level (Li and Jiang, Reference Li and Jiang2017). In addition, China even offered treatment for free or at a reduced price for some diseases, like HIV infection (Cao et al., Reference Cao, Hsieh and Li2020). However, as middle-aged and old people are vulnerable to incur CHE, these measures should be spread and strengthened among them.

The second point is to prevent the occurrence of depression when CHE is inescapable. As per current evidence about financial hardship and depression, not all people experiencing financial hardship will develop depression (Frankham et al., Reference Frankham, Richardson and Maguire2020). This divergent outcome to CHE may be explained by various socioeconomic and psychological variables in the process, like social support, self-esteem, personal agency and personal ability to manage difficulties (Drentea and Reynolds, Reference Drentea and Reynolds2015; Frankham et al., Reference Frankham, Richardson and Maguire2020; Wickrama et al., Reference Wickrama, Surjadi, Lorenz, Conger and Walker2012). Hence, prevention interventions of depression should be introduced widely among the middle-aged and old people. In addition, based on the results of subgroup analysis, the relationship between CHE and depression was significant in males participants and in participants of younger age, with chronic disease, living in rural areas and of lowest economic development in our study. Measures mentioned above plus living subsidies should be implemented with great effort in those key population.

Our study has several limitations. First, as the limitation from original data, household with CHE did not include extremely poor households who cannot receive health services. Second, expenditure data for calculating CHE were mainly collected using the participants’ answers, which cannot reveal the real condition with the recalling bias. Third, the depression was measured by the 10-item CES-D in CHARLS, which may have a deviation from clinical diagnosis, though CES-D was the most widely used scale to evaluate depression in epidemiology studies. Forth, there may be many potential confounders we did not adjust because of the limited data, which need be further studied.

To sum up, nearly one of five middle-aged and old people in China incurred CHE, and people with older age, married/partnered, chronic diseases, outpatient services, inpatient services, lower and highest economic development level had higher prevalence of CHE than others. CHE was associated with a risk of depression. Concerted efforts should be made to monitor CHE events and related depression episode. Moreover, timely preventive interventions about CHE and depression need be implemented among middle-aged and old people to receive UHC by 2030.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at 10.1017/S2045796023000240.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the CHARLS project website (http://charls.pku.edu.cn).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study for providing data and training in using the database. We also thank all the interviewers, respondents and volunteers in the survey. All authors acknowledge the helpful advice by the editors and reviews.

Author contributions

J.L. conceptualized and designed the study, Y.W. did literature search, analysis and interpretation, compiled tables and figures and drafted the manuscript. M.L. and J.L. did writing, reviewing and editing. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 72122001).

Competing interests

None.

Ethical standards

The CHARLS was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Review Committee of the Peking University (IRB00001052-11015).