Introduction

Many studies and several systematic reviews (Boden et al., Reference Boden, Cohen, Froelich, Hoggatt, Abdel Magid and Mushiana2021a; Chigwedere et al., Reference Chigwedere, Sadath, Kabir and Arensman2021; de Kock et al., Reference de Kock, Latham, Leslie, Grindle, Muñoz, Ellis, Polson and O'Malley2021; Phiri et al., Reference Phiri, Ramakrishnan, Rathod, Elliot, Thayanandan, Sandle, Haque, Chau, Wong, Chan, Wong, Raymont, Au-Yeung, Kingdon and Delanerolle2021; Santabarbara et al., Reference Santabarbara, Bueno-Notivol, Lipnicki, Olaya, Perez-Moreno, Gracia-Garcia, Idoiaga-Mondragon and Ozamiz-Etxebarria2021; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Wang, Song, Wu, Luo, Chen and Yan2021) suggest that prevalence of mental health problems was extremely high among healthcare workers during the first wave of the coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) pandemic, including depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, insomnia and other symptoms. Prevalence of anxiety was estimated to be 37% and of depression 36% pooled across 44 of these studies (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Wang, Song, Wu, Luo, Chen and Yan2021). However, substantial variability of results exists across studies. Mental disorders and suicidal ideation and behaviours among healthcare workers during the initial phases of the pandemic were higher than those among the general population (Mortier et al., Reference Mortier, Vilagut, Ferrer, Alayo, Bruffaerts, Cristobal-Narvaez, del Cura-Gonzalez, Domenech-Abella, Felez-Nobrega, Olaya, Pijoan, Vieta, Perez-Sola, Kessler, Haro and Alonso2021).

In the general population, several longitudinal studies suggest that initial high levels of anxiety, depression and other Covid-related psychopathology tend to remit with time (Hirten et al., Reference Hirten, Danieletto, Tomalin, Choi, Zweig, Golden, Kaur, Helmus, Biello, Pyzik, Calcogna, Freeman, Sands, Charney, Bottinger, Keefer, Suarez-Farinas, Nadkarni and Fayad2020; McFadden et al., Reference McFadden, Neil, Moriarty, Gillen, Mallett, Manthorpe, Currie, Schroder, Ravalier, Nicholl, McFadden and Ross2021; Miguel-Puga et al., Reference Miguel-Puga, Cooper-Bribiesca, Avelar-Garnica, Sanchez-Hurtado, Colin-Martinez, Espinosa-Poblano, Anda-Garay, Gonzalez-Diaz, Segura-Santos, Vital-Arriaga and Jauregui-Renaud2021; Sampaio et al., Reference Sampaio, Sequeira and Teixeira2021; Sasaki et al., Reference Sasaki, Asaoka, Kuroda, Tsuno, Imamura and Kawakami2021; Van Steenkiste et al., Reference Van Steenkiste, Schoofs, Gilis and Messiaen2021). But evidence about this trajectory among healthcare workers, who have continued to be exposed to a very high workload related to the pandemic, is more limited and results are mixed. Some studies suggest that distress and fear/worry of Covid-19 remained high or even increased in follow-up surveys (Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Shannon, Browne, Carroll, Maguire, Kerrigan, Hannan, McCarthy, Tully, Mulholland and Dyer2021; Lopez Steinmetz et al., Reference Lopez Steinmetz, Herrera, Fong and Godoy2022; McFadden et al., Reference McFadden, Neil, Moriarty, Gillen, Mallett, Manthorpe, Currie, Schroder, Ravalier, Nicholl, McFadden and Ross2021; Miguel-Puga et al., Reference Miguel-Puga, Cooper-Bribiesca, Avelar-Garnica, Sanchez-Hurtado, Colin-Martinez, Espinosa-Poblano, Anda-Garay, Gonzalez-Diaz, Segura-Santos, Vital-Arriaga and Jauregui-Renaud2021; Sasaki et al., Reference Sasaki, Asaoka, Kuroda, Tsuno, Imamura and Kawakami2021) while others indicate that depression and anxiety tended to decrease at follow-up (Hirten et al., Reference Hirten, Danieletto, Tomalin, Choi, Zweig, Golden, Kaur, Helmus, Biello, Pyzik, Calcogna, Freeman, Sands, Charney, Bottinger, Keefer, Suarez-Farinas, Nadkarni and Fayad2020; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Daniels, Hulme, Hirst, Horner, Lyttle, Samuel, Graham, Reyanrd, Barrett, Foley, Cronin, Umana, Vinagre and Carlton2021; Rodriguez et al., Reference Rodriguez, Montoy, Hoth, Talan, Harland, Eyck, MOwer, Krishnadasan, Santibañez and Mohr2021; Sampaio et al., Reference Sampaio, Sequeira and Teixeira2021; Van Steenkiste et al., Reference Van Steenkiste, Schoofs, Gilis and Messiaen2021). Some of these studies are based on a relatively small number of healthcare workers or on short follow-up periods (Hirten et al., Reference Hirten, Danieletto, Tomalin, Choi, Zweig, Golden, Kaur, Helmus, Biello, Pyzik, Calcogna, Freeman, Sands, Charney, Bottinger, Keefer, Suarez-Farinas, Nadkarni and Fayad2020; Sampaio et al., Reference Sampaio, Sequeira and Teixeira2021; Van Steenkiste et al., Reference Van Steenkiste, Schoofs, Gilis and Messiaen2021) or do not focus on specific mental disorders (Hirten et al., Reference Hirten, Danieletto, Tomalin, Choi, Zweig, Golden, Kaur, Helmus, Biello, Pyzik, Calcogna, Freeman, Sands, Charney, Bottinger, Keefer, Suarez-Farinas, Nadkarni and Fayad2020; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Daniels, Hulme, Hirst, Horner, Lyttle, Samuel, Graham, Reyanrd, Barrett, Foley, Cronin, Umana, Vinagre and Carlton2021; Sampaio et al., Reference Sampaio, Sequeira and Teixeira2021; Sasaki et al., Reference Sasaki, Asaoka, Kuroda, Tsuno, Imamura and Kawakami2021). Therefore, knowledge about the evolution of mental disorders among healthcare workers over the course of the pandemic is limited.

Many factors have been associated with the mental health impact of early Covid-19 pandemic phases among healthcare workers. Distal risk factors include existing mental disorders, female sex, nurse profession and lower income (Kunzler et al., Reference Kunzler, Rothke, Gunthner, Stoffers-Winterling, Tuscher, Coenen, Rehfuess, Schwarzer, Binder, Schmucker, Meerpohl and Lieb2021). Proximal risk factors include frequency/intensity of exposure to the Covid-19 pandemic, longer working hours in high-risk environments, inadequate/insufficient material and human resources, increased workload (Galanis et al., Reference Galanis, Vraka, Fragkou, Bilali and Kaitelidou2021). Given the scarcity of longitudinal studies among healthcare workers, knowledge about risk factors associated with poor mental health trajectories during Covid-19 is limited. One study among Portuguese nurses showed that fear of personal infection and of infecting others were both associated with higher depression, anxiety and stress scores (Sampaio et al., Reference Sampaio, Sequeira and Teixeira2021). Another study of 361 healthcare workers in New York reported increased levels of stress associated with a higher number of Covid-19 cases in the community, while stress was reduced among workers with high emotional support and high resilience at baseline (Hirten et al., Reference Hirten, Danieletto, Tomalin, Choi, Zweig, Golden, Kaur, Helmus, Biello, Pyzik, Calcogna, Freeman, Sands, Charney, Bottinger, Keefer, Suarez-Farinas, Nadkarni and Fayad2020). The influence of distal and proximal risk factors on the evolution of the mental health impact of Covid-19 among healthcare workers requires further research.

This paper aims to assess the evolution of mental disorders (prevalence, incidence and persistence) after the Covid-19 pandemic in a large cohort of healthcare workers after 4 months follow-up in Spain. The paper also examines the association of proximal and distal risk factors with follow-up mental disorders. The period studied corresponds with the final part of wave 1 and the initial part of wave 2 of the pandemic in Spain.

Methods

Study design, population sampling and follow-up

A multicentre, observational cohort study of healthcare workers was carried out in a convenience sample of 18 healthcare institutions from 6 Autonomous Communities in Spain including hospitals, primary care and public healthcare centres. Institutional representatives invited all employed workers to participate using the institution's administrative email distribution lists (i.e., census sampling) to a web-based survey platform (qualtrics.com). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Up to two reminder emails were sent within a 2–4-week period after the initial invitation. Workers completing the baseline interview (May 5th through September 7th, just after the peak of the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic in Spain) and providing an e-mail address were re-contacted for the follow up interview approximately 4 months after, between October 9th and December 11th 2020, at the ascending curve of the pandemic's second wave (mean follow-up time of 120 days; median = 118; IQ range = 105–136 days). More information can be found elsewhere (Alonso et al., Reference Alonso, Vilagut, Mortier, Ferrer, Alayo, Aragon-Peña, Aragones, Campos, Cura-Gonzalez, Emparanza, Espuga, Forjaz, Gonzalez-Pinto, Haro, Lopez-Fresneña, Salazar, Molina, Orti-Lucas, Parellada, Pelayo-Teran, Perez-Zapata, Pijoan, Plana, Puig, Rius, Rodriguez-Blazquez, Sanz, Serra, Kessler, Bruffaerts, Vieta and Perez-Sola2021; Mortier et al., Reference Mortier, Vilagut, Alayo, Ferrer, Amigo, Aragonès, Aragón-Peña, Asúnsolo del Barco, Campos, Espuga, González-Pinto, Haro, López Fresneña, Martínez de Salázar, Molina, Ortí-Lucas, Parellada, Pelayo-Terán, Pérez-Gómez, Pérez-Zapata, Pijoan, Plana, Polentinos-Castro, Portillo-Van Diest, Puig, Rius, Sanz, Serra, Urreta-Barallobre, Kessler, Bruffaerts, Vieta, Pérez-Solá and Alonso2022).

Measures

We used a conceptual framework to study the mental health impact of Covid 19 considering: (i) current mental disorders (negative mental health status), (ii) proximal (pandemic) risk factors (infection, work-related factors and health-related stress), assessed in the baseline survey and distal (pre-pandemic) risk factors (social and economic characteristics and clinical vulnerabilities) (Boden et al., Reference Boden, Zimmerman, Azevedo, Ruzek, Gala, Abdel Magid, Cohen, Walser, Mahtani, Hoggatt and McLean2021b).

Probable current mental disorders

Major depressive disorder (MDD): We used the Spanish version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8), with the cut-off point = 10+ of the sum score to indicate current MDD. The PHQ-8 shows high reliability (>0.8) and good diagnostic accuracy for MDD (AUC > 0.90) (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Levis, Riehm, Saadat, Levis, Azar, Rice, Boruff, Cuijpers, Gilbody, Ioannidis, Kloda, McMillan, Patten, Shrier, Ziegelstein, Akena, Arroll, Ayalon, Baradaran, Baron, Bombardier, Butterworth, Carter, Chagas, Chan, Cholera, Conwell, Ginkel, Fann, Fischer, Fung, Gelaye, Goodyear-Smith, Greeno, Hall, Harrison, Harter, Hegerl, Hides, Hobfoll, Hudson, Hyphantis, Inagaki, Jette, Khamseh, Kiely, Kwan, Lamers, Liu, Lotrakul, Loureiro, Lowe, McGuire, Mohd-Sidik, Munhoz, Muramatsu, Osorio, Patel, Pence, Persoons, Picardi, Reuter, Rooney, Santos, Shaaban, Sidebottom, Simning, Stafford, Sung, Tan, Turner, van Weert, White, Whooley, Winkley, Yamada, Benedetti and Thombs2020). Nevertheless, the instrument can overestimate the prevalence of depressive disorders (Levis et al., Reference Levis, Benedetti, Ioannidis, Sun, Negeri, He, Wu, Krishnan, Bhandari, Neupane, Imran, Rice, Riehm, Saadat, Azar, Boruff, Cuijpers, Gilbody, Kloda, McMillan, Patten, Shrier, Ziegelstein, Alamri, Amtmann, Ayalon, Baradaran, Beraldi, Bernstein, Bhana, Bombardier, Carter, Chagas, Chibanda, Clover, Conwell, Diez-Quevedo, Fann, Fischer, Gholizadeh, Gibson, Green, Greeno, Hall, Haroz, Ismail, Jetté, Khamseh, Kwan, Lara, Liu, Loureiro, Löwe, Marrie, Marsh, McGuire, Muramatsu, Navarrete, Osório, Petersen, Picardi, Pugh, Quinn, Rooney, Shinn, Sidebottom, Spangenberg, Tan, Taylor-Rowan, Turner, van Weert, Vöhringer, Wagner, White, Winkley and Thombs2020).

Generalised anxiety disorder (GAD): We used the seven-item GAD scale (GAD-7), which has a good performance to detect anxiety (AUC > 0.8) (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroene, Spitzer, Williams and Lowe2010; Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Santiago, Colpe, Dempsey, First, Heeringa, Stein, Fullerton, Gruber, Naifeh, Nock, Sampson, Schoenbaum, Zaslavsky and Ursano2013). We used the Spanish version of the GAD-7 (Garcia-Campayo et al., Reference Garcia-Campayo, Zamorano, Ruiz, Pardo, Perez-Paramo, Lopez-Gomez, Freire and Rejas2010) and considered the cut-off point of 10+ to indicate a current GAD.

Panic attacks: the number of panic attacks in the 30 days prior to the interview, assessed with an item from the World Mental Health-International College Student-WMH-ICS (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Santiago, Colpe, Dempsey, First, Heeringa, Stein, Fullerton, Gruber, Naifeh, Nock, Sampson, Schoenbaum, Zaslavsky and Ursano2013; Blasco et al., Reference Blasco, Castellvi, Almenara, Lagares, Roca, Sese, Piqueras, Soto-Sanz, Rodriguez-Marin, Echeburua, Gabilondo, Cebria, Miranda-Mendizabal, Vilagut, Bruffaerts, Auerbach, Kessler and Alonso2016). A dichotomous variable indicated the presence/absence of panic attacks.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): assessed using the 4-item version of the PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) (Blasco et al., Reference Blasco, Castellvi, Almenara, Lagares, Roca, Sese, Piqueras, Soto-Sanz, Rodriguez-Marin, Echeburua, Gabilondo, Cebria, Miranda-Mendizabal, Vilagut, Bruffaerts, Auerbach, Kessler and Alonso2016; Zuromski et al., Reference Zuromski, Ustun, Hwang, Keane, Marx, Stein, Ursano and Kessler2019) which generates diagnoses that closely parallel those of the full PCL-5 (AUC > 0.9), making it well-suited for screening (Weathers et al., Reference Weathers, Litz, Keane, Palmieri, Marx and Schnurr2013). We used the Spanish version of the questionnaire (Resick et al., Reference Resick, Monson and Chard2020), and considered a cut-off point of 7 to indicate current PTSD.

Substance Use Disorder (SUD): We used the CAGE adapted to include drugs questionnaire (CAGE-AID), that consists of 4 items focusing on Cutting down, Annoyance by criticism, Guilty feeling, and Eye-openers, proven useful in helping to make a diagnosis of Alcohol Use Disorder (Dohrenwend et al., Reference Dohrenwend, Krasnoff, Askenasy and Dohrenwend1978; Hinkin et al., Reference Hinkin, Castellon, Dickson-Fuhrman, Daum, Jaffe and Jarvik2001; Zuromski et al., Reference Zuromski, Ustun, Hwang, Keane, Marx, Stein, Ursano and Kessler2019) and Substance Use Disorder (Hinkin et al., Reference Hinkin, Castellon, Dickson-Fuhrman, Daum, Jaffe and Jarvik2001). The questionnaire has been adapted into Spanish (Diez Martinez et al., Reference Diez Martinez, Martin Moros, Altisent Trota, Aznar Tejero, Cebrian Martin, Imaz Perez and del Castillo Pardo1991). Cut-off point of 2+ was considered to indicate current SUD (Mdege and Lang, Reference Mdege and Lang2011).

Proximal risk factors

Covid-19 exposure and infection status: Whether the respondent had been hospitalised for Covid-19 infection and/or had a positive Covid-19 test or medical diagnosis not requiring hospitalisation, whether the respondent had been isolated or quarantined because of exposure to Covid-19 infected person(s), and whether they had loved ones infected with Covid-19.

Work-related factors: Perceived lack of care centre preparedness (i.e., lack of coordination, communication, personnel, supervision at work, training for assigned tasks) using four 5-level Likert-type items ranging from ‘none of the time’ to ‘all of the time’ (summed score rescaled to a 0.0–4.0; Cronbach α = 0.86); average weekly hours worked; changes in assigned functions, team, or working location; changes of a team or assigned functions, and no changes; perceived frequency of lack of protective equipment into a 5-level Likert scale from 0 (‘none of the time’) to 4(‘all of the time’), having to make decisions regarding prioritising care among Covid19 patients, having patients in care that died from Covid-19 infection. We also assessed the frequency of direct exposure to Covid-19 infected patients during professional activity, 5-level Likert type item, ranging from 0 (‘none of the time’) to 4(‘all of the time’).

Health-related stress: Personal health-related stress, as the mean of two items on a 5-level Likert type scale ranging from 0 to 4 with higher values indicating higher levels of stress (Cronbach α = 0.80); and health-related stress of loved ones assessed with two items on a 5-level Likert type scale (concern about loved ones being infected with Covid-19, and concerns about the health of loved ones). The mean value of the corresponding items is obtained with a range from 0 (lower levels of stress) to 4 (higher levels of stress) (Cronbach α = 0.85).

Financial factors: Having suffered a significant loss in personal or familial income due to the Covid-19 pandemic; financial stress, calculated using two 5-level Likert-type items (Dohrenwend et al., Reference Dohrenwend, Krasnoff, Askenasy and Dohrenwend1978), and stress regarding job loss or loss of income because of Covid-19, obtaining a 2-item combined score (Cronbach α = 0.82).

Interpersonal stress: Mean score of four 5-level Likert type items (i.e., love life, relationships with family, problems getting along with people at work or school, other problems experienced by loved ones) ranging from 0 to 4, with higher values indicating higher levels of stress (Cronbach α = 0.79).

Family functioning: The Brief Assessment of Family Functioning Scale (BAFFS) (Mansfield et al., Reference Mansfiedl, Keitner and Sheeran2019), a three-item version of the general functioning scale from the Family Assessment Device (FAD) (Epstein et al., Reference Epstein, Baldwin and Bishop1983) that was developed to assess perceived satisfaction or distress with general family functioning. The Spanish version of the scale is available with good psychometric results (Barroilhet et al., Reference Barroilhet, Cano-Prous, Cervera-Enguix, Forjaz and Guillen-Grima2009). Cronbach's α for internal consistency in our study was α = 0.50.

Parental stress: 4-item version derived from the Parental Stress Scale (Berry and Jones, Reference Berry and Jones1995). Items were summed and re-scaled ranging from 0 (lower parental stress) to 4 (highest parental stress). The Spanish version has been developed showing adequate psychometric properties (Oronoz et al., Reference Oronoz, Alonso-Arbiol and Balluerka2007). Internal consistency obtained in our study was α = 0.74.

Distal risk factors

Demographics and professional characteristics: Age category; gender; country of birth; marital status; having children in care; profession; and workplace.

Prior lifetime mental disorders: Lifetime mental disorders prior to the onset of the Covid-19 outbreak assessed using a checklist from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (Navarro-Mateu et al., Reference Navarro-Mateu, Moran-Sanchez, Alonso, Tormo, Pujalte, Garriga, Aguilar-Gaxiola and Navarro2013) screening lifetime mood, anxiety, substance use problems and ‘other’ mental disorders. The number of chronic physical health conditions was also assessed for a list of conditions considered as vulnerable to Covid-19.

Ethical considerations

The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Code of Ethics and was approved by the IRB Parc de Salut Mar (2020/9203/I) and by the corresponding IRBs of all the participating centres. Registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04556565).

Statistical analysis

Missing item-level data among respondents were imputed using multiple imputations (MI) by chained equations (Van Bureen, Reference Van Bureen2012) (12 imputed datasets, 10 iterations per imputation).

Sample characteristics are reported as weighted percentages and s.e. Differences of baseline characteristics between those who did and those who did not participate in the follow-up survey (lost to follow up) were evaluated using the modified Rao-Scott χ 2 test. To correct the bias caused by lost to follow up missing values, inverse-probability weighting (IPW) (Seaman et al., Reference Seaman, White, Copas and Li2012) was applied, as the inverse of the probability of completing the follow-up survey on observed related baseline covariates, estimated using a logistic regression model. Additionally, post-stratification weights through raking were used to adjust for potential deviations from target population distributions in terms of age, gender, profession and healthcare centre. Pooled MI-based parameter estimates and standard errors (s.e.) and statistical inferences were obtained from the weighted analysis of these MI datasets.

Prevalence of any probable mental disorder at baseline and at follow up was estimated overall and stratified by distal and proximal risk factors. Prevalence of any probable mental disorder at follow-up stratified among individuals with a negative baseline screen (i.e., incidence) and among individuals with a positive baseline screen (i.e., persistence) were also estimated. Logistic regression estimated the association of each proximal risk factor with probable mental disorders adjusting each time for all distal risk factors, health care centre and time of baseline survey. Regression coefficients were exponentiated to obtain odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All Likert-type variables were analysed as continuous. Potential deviations from a continuous linear effect in the logit were assessed graphically. Population-attributable risk proportions (PARP) (Krysinska and Martin, Reference Krysinska and Martin2009) and associated 95% confidence intervals obtained with bootstrap resampling (200 replications), were simulated based on individuals’ predicted probabilities estimated by the multivariable logistic regression equations(Nock et al., Reference Nock, Stein, Heeringa, Ursano, Colpe, Fullerton, Hwang, Naifeh, Sampson, Schoenbaum, Zaslavsky, Kessler and Army2014). PARP provide estimates of the proportions of mental disorders that could potentially be attributed to specific predictor variables assuming a causal pathway between these predictor variables and the outcome.

All analyses were adjusted by the week of the interview (entered as a continuous variable) to account for possible differences of baseline predictor variables by the time of assessment at baseline. Since the correlation between the response time at baseline and the time of follow up was r = −0.93, we only adjusted by one of these variables.

Variance estimates were obtained using the Taylor series linearisation method considering weighting and within-health care centre clustering of data. MI were carried out using package mice from R (Van Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn, Reference Van Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn2011) Analyses were performed using R v4.1.032 (Team, Reference Team2021) and SAS v9.4 (INC SI, 2014).

Results

Participation

A total of 8996 healthcare workers participated in the baseline evaluation. The survey participation rate, calculated as unique individuals who agreed to participate (n = 10 360) divided by unique first survey page visitors (n = 11 507), was 90.0%, and of them, 8328 professionals finalised the baseline interview, representing a survey completion rate of 80.4% (Eysenbach, Reference Eysenbach2004). Of the total 8996 unique healthcare workers that provided sufficient information of the baseline evaluation, n = 7318 provided their email to be re-contacted and n = 4809 (cooperation rate = 65.7%) answered the follow-up interview between 9th of October and 11th of December 2021, with a mean number of 120.1 days (s.d. = 22.2) between baseline and follow up assessments. Those participating in the follow-up survey differed only marginally in some baseline study characteristics (follow-up participants were older, with higher income, with a higher proportion being medical doctors, and having suffered of Covid-19 on their own or their loved ones and had suffered less health-related and financials stresses). These differences were very small, although statistically significant due to the high numbers involved (online Supplementary Table 1). Inverse probability weights were applied to restore these differences as explained above.

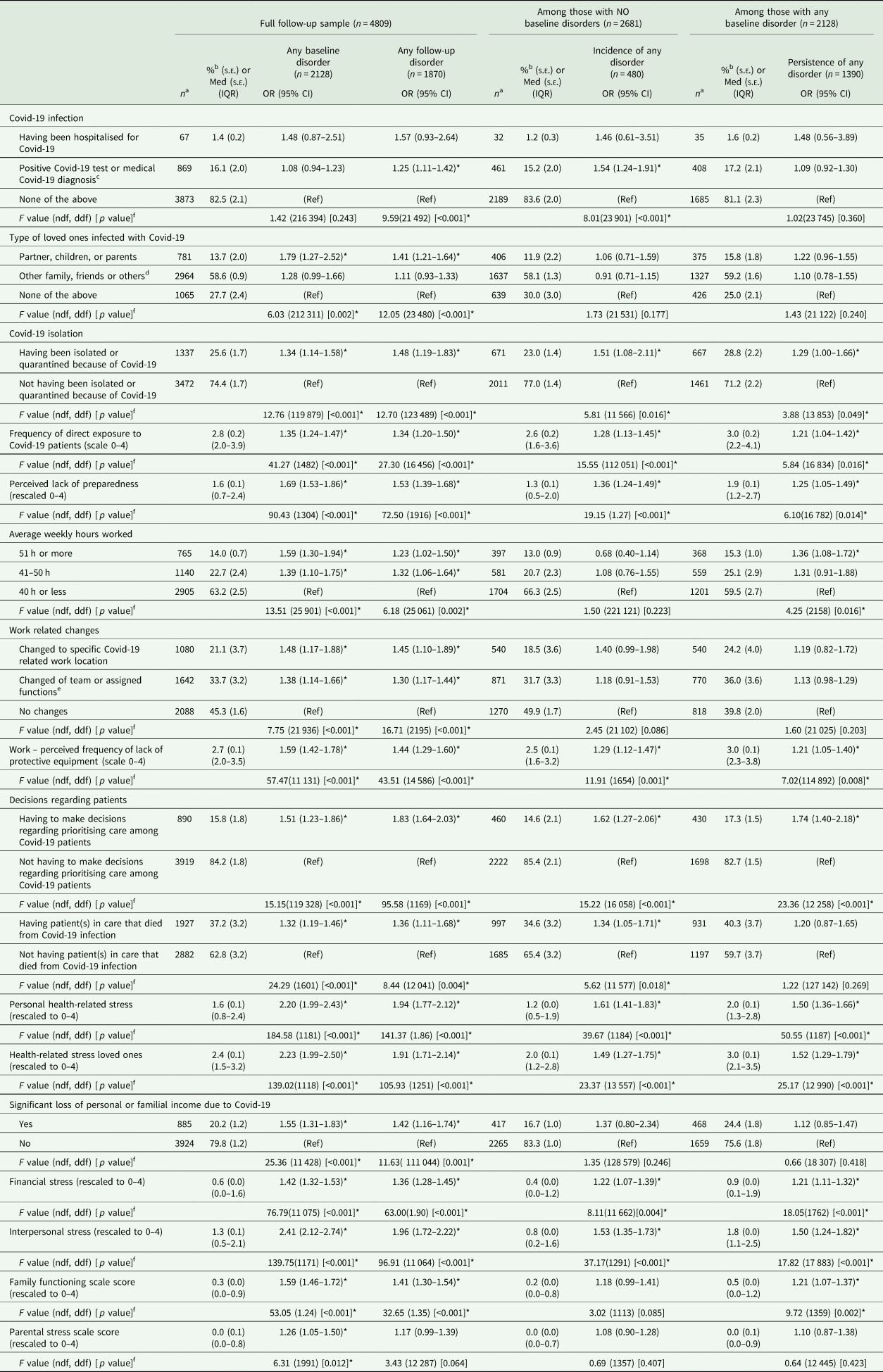

Any mental disorder prevalence, incidence and persistence

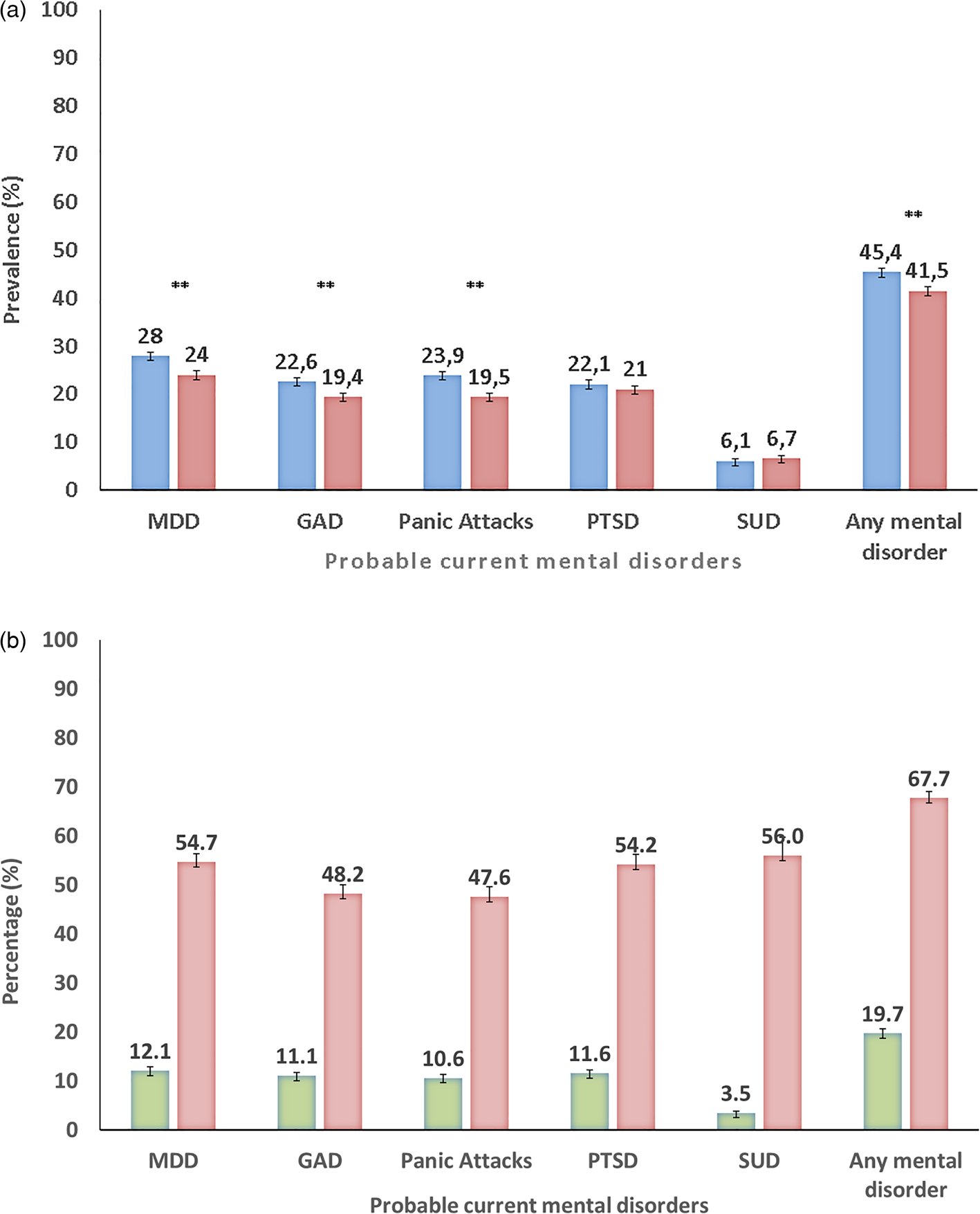

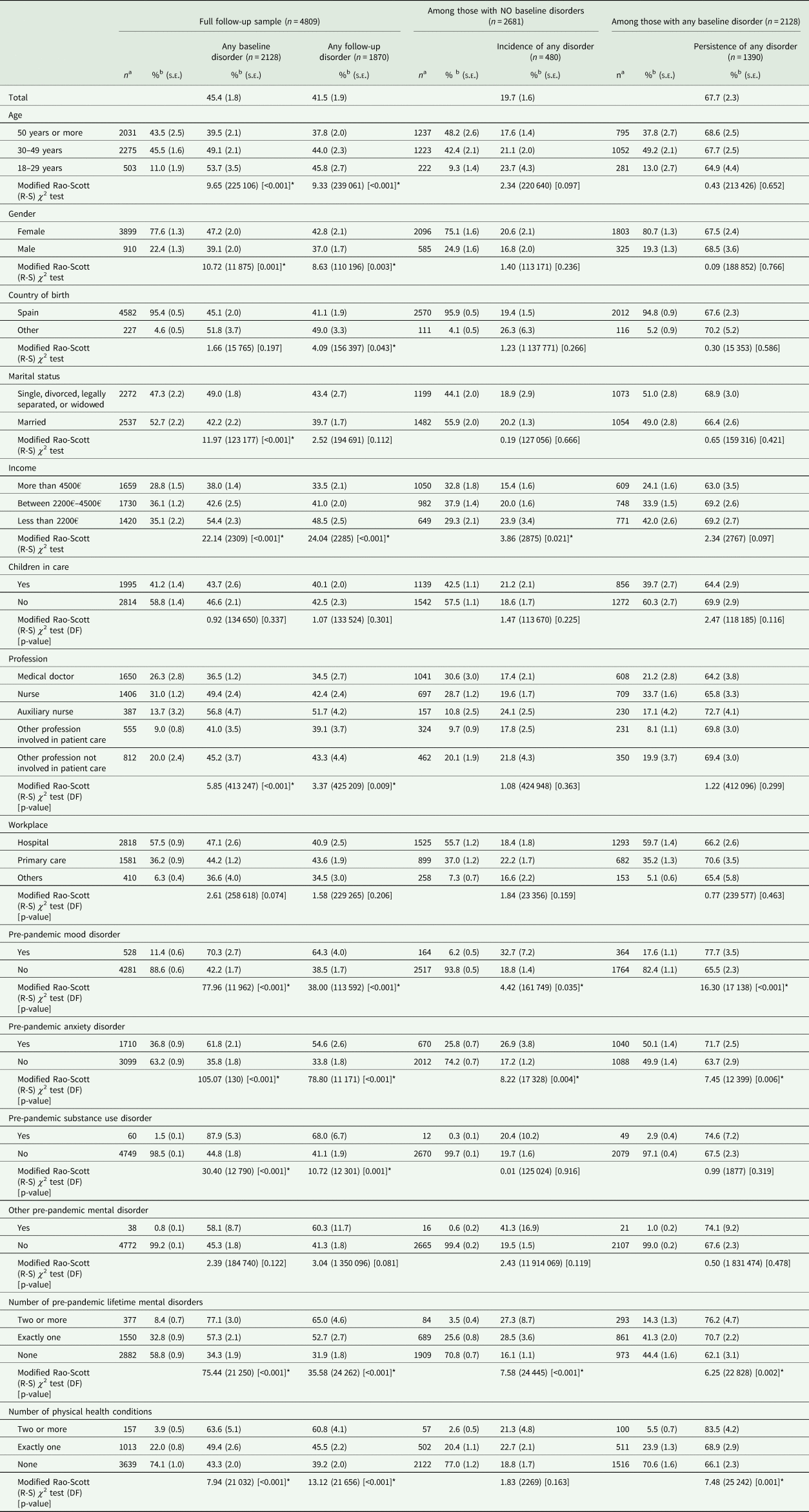

At 4-month follow-up, the prevalence of any probable mental disorder was 41.5%, somewhat lower than at baseline (45.4%, Mc Nemar test p-value < 0.001) (Table 1 and Fig. 1a). Prevalence at follow-up was higher for younger age groups, female gender, country of birth other than Spain, lower income, auxiliary nurse profession, and several pre-pandemic mental disorders and higher number of chronic physical health conditions. Incidence of probable mental disorder (among those without baseline disorder) was 19.7% (s.e. = 1.6), being significantly higher among those with lower income and those with some pre-pandemic mental disorders (Table 1, middle, and Fig. 1b). More than two thirds (67.7%; s.e. = 2.3) with a baseline probable mental disorder, persisted with a disorder at follow-up. Persistence was significantly associated to the same distal factors than incidence, except for lower-income levels, for which higher persistence frequency did not reach statistical significance, and except for a number of chronic physical health conditions, significantly associated to persistence, but not to incidence (Table 1, three last columns, and Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1. (a) Prevalence of probable current mental disorders among Spanish Healthcare Workers [n = 4809, baseline (blue bars); 4-month follow-up (red bars)]. (b) Probable current mental disorders among Spanish healthcare workers at 4-month follow-up survey: Incident/New Disorder Onset (green bars) and Persistent/Recurrent Disorder (red bars) (n = 4809). MDD, major depressive disorder; GAD, generalised anxiety disorder; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; SUD, substance use disorder. **p-value <0.001 for the multiple imputation chi-square pooling of the McNemar's test comparing paired prevalence at baseline and follow up for the mental disorders evaluated. *p-value <0.05 for the multiple imputations χ 2 pooling of the McNemar's test comparing paired prevalence at baseline and follow up for the mental disorders evaluated.

Table 1. Prevalence, incidence and persistence of any of mental disorders, total and by distal risk factors. Spanish healthcare workers, MINDCOVID study (absolute numbers and weighted proportions)

R-S, Rao-Scott; DF, Degrees of freedom.

Note. Covid-19, coronavirus disease 2019; s.e., standard error.

a Unweighted numbers.

b Weighted percentage [using post-stratification weights and inverse-probability weighting (IPW)].

*Statistically significant (α = 0.05).

There was a trend towards a lower severity of both PHQ-8 and GAD-7 scores between baseline and 4-months follow-up assessments (see online Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). Online Supplementary Tables 4 and 5 present unadjusted and adjusted, respectively, associations between distal risk factors and probable mental disorders prevalence, incidence and persistence.

Association between proximal risk factors and any mental disorder

Table 2 presents associations of prevalence, incidence and persistence of any probable mental disorder with each proximal and work-related risk factor in our study, adjusting by all distal factors (i.e., those presented in Table 1). Each row presents a different model. An overall multivariate model was not primarily attempted, in order to minimise over adjustment bias (Schistermann et al., Reference Schisterman, Cole and Platt2009). (Online Supplementary Table 6 shows the bivariate associations, and online Supplementary Table 7, the fully adjusted model.) All risk factors evaluated were significantly associated with a higher follow-up prevalence of probable mental disorders, except for having been hospitalised for Covid-19 (probably due to low numbers in the sample), and for having other family, friends or others infected with Covid-19. The same risk factors showed a positive association with the prevalence of any probable mental disorder after the 1st wave of the pandemic (baseline assessment) as with prevalence during the 2nd wave (follow-up assessment) (see columns 3 and 4 of Table 2). Nevertheless, associations tended to be marginally higher for baseline than for follow up data, for work-related factors (number of hours worked), for personal health-related stress, for health-related stress of loved ones and for interpersonal stress. Covid-19 own infection was a risk factor for new onset (OR = 1.54 95% IC = 1.24, 1.91) but not for persistence (1.09; 95% IC = 0.92, 1.30), while a larger number of hours worked was a risk factor for persistence but not for new onset (Table 2, columns 7 and 10).

Table 2. Adjusted associations between proximal risk factors and any probable mental disorders diagnosis (bivariate adjusted for all distal factors). Spanish healthcare workers, MINDCOVID study (absolute numbers and weighted proportions)

CI, confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range; Med, median; s.e., standard error; ndf, numerator degrees of freedom; ddf, denominator degrees of freedom.

Note. OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; Covid-19, coronavirus disease 2019; s.e., standard error; IQR, interquartile range. All analyses adjust for time of survey (weeks), health centre membership, and all distal factors.

a Unweighted numbers.

b Weighted percentage (using post-stratification weights and inverse-probability weighting (IPW)).

c The category ‘positive Covid-19 test or medical Covid-19 diagnosis’ excludes those having been hospitalised for Covid-19.

d The category ‘other family, friends, or others’ excludes having a partner, children, or parents infected with Covid-19.

e The category ‘changed of team or assigned functions’ excludes those that changed to a specific Covid-19-related work location.

f F-test to evaluate joint significance of categorical predictor levels base on multiple imputation.

*Statistically significant (α = 0.05).

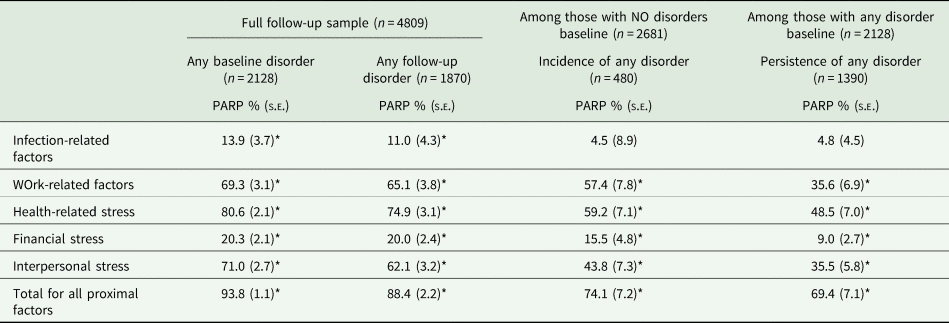

Population attributable risk proportions (PARPs)

Table 3 shows attributable risk proportions (PARPs) of proximal risk factors of any probable mental disorder, adjusting by distal factors. Health-related, work-related, and interpersonal stress presented the highest association with both prevalence, incidence and persistence. PARPs were generally higher for incidence of probable mental disorders than for persistence of baseline probable disorders.

Table 3. Adjusted population attributable risk proportions (PARP) for the association between proximal risk factor domains and any probable mental disorders diagnosis. Spanish healthcare workers, MINDCOVID study

PARP, population-attributable risk proportion; s.e., standard error.

*Statistically significant (α = 0.05).

Discussion

This study is, to our knowledge, the first one to estimate the prevalence of probable mental disorders among healthcare workers during the second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic focusing on the most relevant mental disorders and including a large sample. Two major results arise from this longitudinal study. First, the prevalence of probable mental disorders during the second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic was high and very similar to that during the first wave. This was mainly due to the high persistence of baseline disorders (more than two-thirds of those with disorders at baseline continued to have these disorders at follow-up); nevertheless, the incidence of new probable mental disorders was also important (one in 5 of healthcare workers free of mental disorders during the first wave developed one in the second wave). And second, health-related and work-related factors as well as interpersonal stress were important risk factors for both onset and persistence of mental disorders. Some of these factors are potentially preventable (Kisely et al., Reference Kisely, Warren, McMahon, Dalais, Henry and Siskind2020). Thus, adequately addressing these factors might be effective in reducing the high prevalence of mental disorders in this critical segment of the population.

Our results in context with previous knowledge

Frequency of mental health impacts

As noted in the introduction, longitudinal studies assessing the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic among healthcare workers are scarce and results are mixed. Some studies indicate the persistence of psychological stress (Sasaki et al., Reference Sasaki, Asaoka, Kuroda, Tsuno, Imamura and Kawakami2021) while others suggest a lowering of depression and anxiety, in particular after 5 or more months from the beginning of the pandemic (Paul et al., Reference Paul, Wan Mak, Fancourt and Bu2021). In general, evidence is limited due to a small number of studies, very short follow-up periods and with a small number of cases (Hirten et al., Reference Hirten, Danieletto, Tomalin, Choi, Zweig, Golden, Kaur, Helmus, Biello, Pyzik, Calcogna, Freeman, Sands, Charney, Bottinger, Keefer, Suarez-Farinas, Nadkarni and Fayad2020; Sampaio et al., Reference Sampaio, Sequeira and Teixeira2021; Van Steenkiste et al., Reference Van Steenkiste, Schoofs, Gilis and Messiaen2021). Our study captures a longer follow-up than most of the previous studies among healthcare workers with a considerably larger sample, and it clearly suggests that mental health impact is maintained during the second wave of the pandemic (4 months after the baseline assessment). This finding contrasts with studies in the general population, which show that the high impact at the beginning of the first wave of the pandemic tends to decline after 3–5 weeks of the first wave (Gonzalez-Sanguino et al., Reference Gonzalez-Sanguino, Ausin, Castellanos, Saiz, Lopez-Gomez, Ugidos and Muñoz2020; Daly and Robinson, Reference Daly and Robinson2021; Fancourt et al., Reference Fancourt, Steptoe and Bu2021; Robinson and Daly, Reference Robinson and Daly2021). Nevertheless, some general population studies show a persistently high level of mental health impact through the initial phases of the pandemic (Kikuchi et al., Reference Kikuchi, Machida, Nakamura, Saito, Odagiri, Kojima, Watanabe, Fukui and Inoue2020; McGinty et al., Reference McGinty, Presskreischer, Anderson, Han and Barry2020) while still another study shows that a substantial proportion of the general population maintained high levels of symptoms (McPherson et al., Reference McPherson, McAloney-Kocaman, McGlinchey, Faeth and Armour2021). A possible explanation of the different trajectory among healthcare workers is the maintained levels of proximal stressors they faced, like other essential workers (Paul et al., Reference Paul, Wan Mak, Fancourt and Bu2021). Also, we found that Panic Attacks and GAD tended to be less persistent than MDD and PTSD. This might indicate they will become the more lasting mental health impacts of Covid-19 among healthcare workers. But the 4-month follow-up period in our study might be short to assess stable trends. More research is needed, assessing proximal stressors and mental health outcomes using longer follow-ups and large enough samples, to assess the extent to which the likely mental health impact due to the Covid-19 pandemic may become sustained in time among healthcare workers.

Risk factors

Most proximal risk factors analysed in our study were associated with the prevalence of probable mental disorders after the 1st wave (baseline assessment) and during the 2nd wave of the pandemic. Covid-19 infection, which was frequent among healthcare workers, increased the risk of new onset of probable mental disorders. These associations suggest that it is necessary to implement interventions to mitigate the mental health impact of the pandemic among healthcare workers. Large population attributable risk proportions found indicate a potentially high benefit, if a causal interpretation can be assumed. Although many interventions have been suggested to mitigate the effects of infectious disease epidemics on population mental health (Leon et al., Reference Leon, Olfson, Portera, Farber and Sheehan1997; North and Pfefferbaum, Reference North and Pfefferbaum2013; Kisely et al., Reference Kisely, Warren, McMahon, Dalais, Henry and Siskind2020), evidence of their effectiveness among healthcare workers is very limited and of insufficient quality (Pollock et al., Reference Pollock, Campbell, Cheyne, Cowie, Davis, McCallum, McGill, Elders, Hagen, McClurg, Torrens and Maxwell2020). Specific e-health interventions for healthcare workers are of increasing interest (Drissi et al., Reference Drissi, Ouhbi, Marques, de la Torre Diez, Ghogho and Janati Idrissi2021). Our results support previous recommendations that when selecting interventions aimed at supporting frontline workers' mental health, organisational, social, personal and psychological factors may all be important (Pollock et al., Reference Pollock, Campbell, Cheyne, Cowie, Davis, McCallum, McGill, Elders, Hagen, McClurg, Torrens and Maxwell2020).

Persistent and new-onset probable cases

We stratified the analyses according to the mental health status after the first wave of the pandemic (baseline assessment). This has allowed us to estimate the ‘persistence’ of probable mental disorders and the rate of appearance of ‘incident’ disorders. This approach is quite novel in the literature of the impact of Covid-19, and our results suggest: (a) that most of the prevalent disorders at follow up are at the expense of workers that had already a disorder at baseline; and (b) that, nevertheless, new probable cases appear during the second wave and they are associated with almost exactly the same proximal risk factors that are associated with persistence. The first finding suggests that persistent mental disorders may be an emergent issue among healthcare workers after the Covid-19 pandemic. And the second, strongly suggests the need to implement more effective attenuation of work-related and health-related factors during the evolution of the pandemic. Similar to a recently published study with Spanish healthcare workers (Mediavilla et al., Reference Mediavilla, Fernández-Jiménez, Martinez-Morata, Jaramillo, Andreo-Jover, Morán-Sánchez, Mascayano, Moreno-Küstner, Minué, Ayuso-Mateos, Bryant, Bravo-Ortiz and Martínez-Alés2021), our results suggest a high persistent negative mental health impact of Covid-19. Mental health monitoring and facilitating access to services are needed to decrease the likelihood of chronicity among healthcare workers.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths. First, it is based on a large sample of healthcare workers of a wide distribution of public health services in Spain, including hospitals, primary care and emergency and public health departments. All workers in each institution were invited to the study, based on a clear sampling frame and providing a wide picture of exposure to acute stressors. Our study is unique in following the same healthcare workers and differentiating new onset of probable disorders and persistence of disorders present after wave one.

The study has also some limitations that should be considered. First, the follow-up cooperation rate was incomplete (65.7%). In addition, the cooperation at baseline was even lower (Alonso et al., Reference Alonso, Vilagut, Mortier, Ferrer, Alayo, Aragon-Peña, Aragones, Campos, Cura-Gonzalez, Emparanza, Espuga, Forjaz, Gonzalez-Pinto, Haro, Lopez-Fresneña, Salazar, Molina, Orti-Lucas, Parellada, Pelayo-Teran, Perez-Zapata, Pijoan, Plana, Puig, Rius, Rodriguez-Blazquez, Sanz, Serra, Kessler, Bruffaerts, Vieta and Perez-Sola2021), although the real figure is difficult to assess, since data from one large hospital in our study showed that the proportion of emails ‘seen’ by target workers was just over 26% at baseline. Although differences between workers participating in the follow-up survey and those not participating were very small, inverse probability weighting has been applied to correct for differential probabilities of participation at follow up surveys based on baseline characteristics. Additionally, we used post-stratification so that each survey matches the distribution of age, gender and profession in each of the health institutions included in the study. Moreover, response rates across the 18 participating institutions were not correlated with the prevalence of any mental disorder (Spearman R = −0.12, p = 0.65). Also, data come from one country only which limits the external validity. Second, it is important to note that we used screening measures of mental disorders. While they have shown to have acceptable validity for identifying individuals with a high risk of a particular mental disorder, results cannot be interpreted as clinical diagnoses. Moreover, the PHQ might overestimate the prevalence of depression (Levis et al., Reference Levis, Benedetti, Ioannidis, Sun, Negeri, He, Wu, Krishnan, Bhandari, Neupane, Imran, Rice, Riehm, Saadat, Azar, Boruff, Cuijpers, Gilbody, Kloda, McMillan, Patten, Shrier, Ziegelstein, Alamri, Amtmann, Ayalon, Baradaran, Beraldi, Bernstein, Bhana, Bombardier, Carter, Chagas, Chibanda, Clover, Conwell, Diez-Quevedo, Fann, Fischer, Gholizadeh, Gibson, Green, Greeno, Hall, Haroz, Ismail, Jetté, Khamseh, Kwan, Lara, Liu, Loureiro, Löwe, Marrie, Marsh, McGuire, Muramatsu, Navarrete, Osório, Petersen, Picardi, Pugh, Quinn, Rooney, Shinn, Sidebottom, Spangenberg, Tan, Taylor-Rowan, Turner, van Weert, Vöhringer, Wagner, White, Winkley and Thombs2020). Thus, we consider them only ‘probable’ mental disorders. But it is important to clarify that a positive result in each of these measures indicates relevant psychopathology. One advantage of using these particular measures is that results can be compared with many existing data with other populations and time periods. Nevertheless, two-phase studies would provide a more valid estimation (Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Pickles, Tansella and Vazquez Barquero1999). Third, both distal and proximal factors used in the analyses were gathered at baseline. While there is the possibility that proximal factors varied during the follow-up, we assumed this was minimal given the follow-up period was 4 months on average. Moreover, in the analysis, we wanted to ensure that all proximal/distal factors occurred before the outcome (incidence/persistence). Finally, 4 months of follow-up is a short time period for a complete understanding of the mental impact dynamics of the Covid-19 pandemic. Longer follow-up periods are necessary. A paper indicates that 56% of Spanish healthcare workers remained symptomatic or worsened over time in terms of psychological distress (Mediavilla et al., Reference Mediavilla, Fernández-Jiménez, Martinez-Morata, Jaramillo, Andreo-Jover, Morán-Sánchez, Mascayano, Moreno-Küstner, Minué, Ayuso-Mateos, Bryant, Bravo-Ortiz and Martínez-Alés2021). In addition, length of follow-up differed by healthcare workers. This was due to an extended duration of the baseline assessment because of a slow roll-in period of health institutions. But we did adjust by a centre and by assessment date to minimise any possible bias.

Conclusions

Notwithstanding the above-mentioned limitations, our study indicates that the prevalence of probable mental disorders among Spanish healthcare workers during the second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic was similarly high to that after the first wave. This was in good part due to the persistence of mental disorders detected at the baseline, but with a relevant incidence of about 1 in 5 of HCWs without mental disorders during the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic. Health-related factors, work-related factors and interpersonal stress are important risks of persistence of mental disorders and of incidence of mental disorders. Adequately addressing these factors might have prevented a considerable amount of mental health impact of the pandemic among this vulnerable population.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796022000130

Data

The data will be available in the future in a repository that the funding institution (Instituto de Salud Carlos III) is currently developing. For any additional information contact with the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to sincerely thank all healthcare workers participating in the study. They also thank Puri Barbas for the management of the project and Carme Gasull for helping with the manuscript preparation.

Author contributors

J. A., G. V. and P. M. reviewed the literature. J. A., G. V., P. M., M. F., E. A., V. P. S., J. M. H., R. C. K. and R. B. conceived and designed the study. E. A., J. D. M., N. L., T. P., J. M. P. T., J. I. P., J. I. E., M. E., N. P., A. G. P., C. R., E. A., I. C. G., A. A. P., M. C., A. P. Z., E. V., C. S. and V. P. S. acquired the data. G. V., I. A., F. A. and PM cleaned and analysed the data. J. A., G. V. and P. M. drafted the initial version of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the initial draft and made a critical contribution to the interpretation of the data and approved the manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Financial support

Instituto de Salud Carlos III/ Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación/ FEDER (J. A., grant number COV20/00711); Project “PI17/00521”, funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) and co-funded by the European Union, PERIS, Health Dpt, Generaliat de Catalunya (I. A., grant number SLT017/20/000009); ISCIII-FSE+, Miguel Servet (P. M., grant number CP21/00078); ISCIII-FSE, Sara Borrell (P. M., grant number CD18/00049), Generalitat de Catalunya (2017SGR452). Additional partial funding was received from the Gerencia Regional de Salud de Castilla y León (SACYL) (J. M. P. T., grant number GRS COVID 32/A/20).

Conflict of interest

E. A. reports personal fees from Lündbeck, Esteve, Schwabe and Roche. E. V. reports personal fees from Abbott, Allergan, Angelini, Lundbeck, Sage and Sanofi, grants from Novartis and Ferrer and grants and personal fees from Janssen, outside the submitted work. J. D. M. reports personal fees from Janssen and Angelini, personal fees and non-financial support from Otsuka, Lundbeck and Accord, outside the submitted work. J. M. P. T. reports personal fees from Angelini, Janssen and Lunbeck, and grants from Janssen, outside the submitted work. R. C. K. was a consultant for Datastat, Inc., Holmusk, RallyPoint Networks, Inc., Sage Therapeutics and he has stock options in Mirah, P. Y. M., and Roga Sciences. All other authors reported no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this study comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.