This article interrogates the slippage between subject matter and musical affect in works for the parlour written in response to the Mexican–American War. Using the concept of musical witness established by Amy Lynn Wlodarski, I discuss how musical works written in response to the war, particularly laments and battle pieces, use musical affect to transform the violence of the battlefield. Many works anesthetize that violence or conjure up a patriotic sensibility that affirms the mission and values of the United States, but some emphasize the traumatic pain and violence of the battlefield, bringing it into the home. These pieces mirror the reports of suffering endured by soldiers found in media coverage of the war during its second year, which fuelled a growing anti-war voice among the public. Trauma is brought to the foreground through lyrics focused on suffering, death and grief, musical depictions of pain, and through the embodied act of performance. Drawing on scholarship concerned with the embodiment of trauma, especially the work of Maria Cizmic and Jillian Rogers, I explore the ways that the corporeal act of playing musical works about the war encouraged its performers and audience members to identify physically with the suffering soldiers of the battlefield.

So sings the narrator of Orramel Whittlesey's 1849 ‘The Dying Soldier of Buena Vista’. The song depicts a soldier at the Battle of Buena Vista two years earlier, narrating his final thoughts of his parents and sweetheart to a fellow soldier as he dies.Footnote 1 Beneath the mournful text, the piano rolls sweet major chords in a lilting harmonic progression, seemingly more suited to an amorous love song than to a tragic lament. This song, like countless other musical works about the war between the United States and Mexico, envisions the events of the battlefield, inviting its performers and audience members to imagine the conflict as well. Its musical affect – here, pleasant and lyrical – seems to treat the tragic death in a sentimental fashion.

The Mexican–American War (1846–48) led to the composition and publication of numerous musical works on topics related to the conflict. These include music for use on the front lines as well as choral tunes and other pieces for public performance, but the vast majority of works related to the war are for solo piano or solo voice with keyboard accompaniment, most suited to parlour performance.Footnote 2 This repertoire comprises laments, battle pieces and patriotic songs and dances, some of which include graphic depictions of battlefield events. Pieces remember specific battles, such as Buena Vista, Vera Cruz, Monterrey and Palo Alto; include tributes to military heroes, especially General Zachary Taylor; and also craft fictional narratives surrounding historical events. Musical works reflect mid-nineteenth-century American taste in parlour music, which was mass-produced for amateurs, mainly women, to enjoy in the domestic setting. The body of pieces about the war between the United States and Mexico is not enormous, but the conflict itself was less than two years long. Its repertoire foreshadows the genres and larger number of works that would appear during the Civil War.

Like ‘The Dying Soldier of Buena Vista’, most musical pieces about the war, including those depicting violence and physical pain, are in major keys, featuring lyrical melodies and upbeat dance rhythms – the typical fare of parlour music of this period. Their upbeat musical affect affirmed nineteenth-century values associated with domestic music-making, which participated in an idealized construction of femininity and gendered domesticity.Footnote 3 The cheerful and celebratory musical qualities of works about the war mirrored the voice of pro-war propaganda, which sought to make a contentious conflict palatable to the American public. Like newspaper reports, musical works about the war arrived on the heels of the events that they depicted, with the sheet music industry churning out pieces about the conflict as quickly as it could.Footnote 4 Composers’ and publishers’ efforts were clearly opportunistic, commodifying the events of war to profit financially, and embodying musical characteristics typical of mass-produced parlour music for amateur consumption, ensuring the commercial success of their works.

It is a challenge to reconcile the gruesome and morally unsettling reality of the Mexican–American War with the musical language of parlour pieces that depict the conflict. The absence of primary source documentation about parlour performance of pieces on the topic of the war during the 1840s furthers possibilities for misunderstanding. Why did composers embrace musical idioms so much at odds with the material they sought to represent, and what did performers and listeners at home make of the repertoire? How did it contribute to their understanding of the events unfolding to the south?

This article interrogates the slippage between subject matter and musical affect in works for the parlour written in response to the Mexican–American War. Using the concept of musical witness established by Amy Lynn Wlodarski, I discuss how musical works written in response to the war, particularly laments and battle pieces, use musical affect to transform the violence of the battlefield. At times, they anesthetize that violence or conjure up a patriotic sensibility that affirms the mission and values of the United States and its armed forces. While most musical works about the war mimic the patriotism and emphasis on heroism found in pro-war voices of the time, some emphasize the traumatic pain and violence of the battlefield, bringing it into the home. These pieces mirror the reports of suffering endured by soldiers found in media coverage of the war during its second year, which, as I will discuss, fuelled a growing anti-war voice among the public. Trauma is brought to the foreground through lyrics focused on suffering, death and grief, musical depictions of physical and emotional pain, and through the embodied act of performance. Drawing on scholarship concerned with the embodiment of trauma, especially the work of Maria Cizmic and Jillian Rogers, I explore the ways that the corporeal act of playing musical works about the war encouraged its performers and audience members to identify physically with the suffering soldiers of the battlefield.

One of the challenges of this project is the absence of period documentation relating to the musical works on which I am focused. I do not know how performers interpreted music about the war or what audiences made of them. Incomplete historical information is a common obstacle in the study of private-sphere music-making. The importance of speculation or constructivist history and the ‘historical imagination’, an idea most associated with R.G. Collingwood, in the study of domestic music-making, is paramount.Footnote 5 Throughout this project, I use conjecture to fill in gaps in historical data; this includes speculating about how performers and audiences responded emotionally to musical works and the level of playing on the part of the performer. I also use theories from trauma studies to construct plausible modes of understanding for the historical music-making on which I am focused.

The development of trauma studies as a critical field is intertwined with Holocaust studies, and much of the work applying critical understandings of trauma has focused on the Holocaust and events since that time. Many of the musical works that respond to the horrors of the twentieth century are large-scale pieces for public performance like Henryck Gorecki's Symphony No. 3, John Corigliano's Symphony No. 1 and Krzysztof Penderecki's Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima. Despite the significant visibility of large, public compositions, there are countless musical works written in response to trauma in small, private genres as well – and scholars who are deeply engaged with these works.Footnote 6 Similarly, despite the dominance of the Holocaust in trauma studies, musicologists, as well as scholars in other disciplines, can apply twentieth-century conceptions of trauma to earlier conflicts and to works of art associated with them – an approach discussed by Michelle Meinhart and Jillian Rogers in their introduction to this volume.Footnote 7 Throughout this article, I use conceptions of witnessing and embodiment to understand musical representations of trauma, illustrating how musical works about the Mexican–American War reveal a conflicted and sometimes contradictory American public wrestling with the brutal realities of war.Footnote 8

Reactions to the War Among the American Public

In 1845, the United States annexed the Republic of Texas, which created an intense border dispute, with both Mexico and the United States laying claim to the area between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande. Early in 1846, President James Polk ordered United States forces, led by Zachary Taylor, to occupy the disputed territory. The Mexican Army responded by attacking a US Army outpost and then a fort along the Rio Grande, killing twelve Americans. Congress declared war in May 1846.

The Mexican–American War was one of the most contentious conflicts in American history.Footnote 9 In the first year of the military campaign, public support was generally strong, but as the war drew on, opinion shifted, and a heated debate played out in the media.Footnote 10 Whereas anti-war reporting had been present mostly in northern and abolitionist newspapers early in the war, it became widespread, with prominent political and cultural figures, including Frederick Douglas, Margaret Fuller, Abraham Lincoln and Henry David Thoreau, voicing their opposition.Footnote 11

A sense of moral ambiguity pervaded the public's feelings about the conflict as it dragged into a second year.Footnote 12 The president had justified the war in the wake of an attack on Americans, but it became increasingly clear to the public that there were many additional reasons for the conflict.Footnote 13 The war was an attempt to gain more slave territory for southern states and to increase the power of the South within the Union.Footnote 14 It was also a seizure of land from a country that claimed the territories in question as its own.Footnote 15 As the war progressed, so did divisions between the northern and southern states and between Whigs and Democrats. A faction grew advocating for the total annexation of Mexico, which was then crushed by southern Democrats who feared that this would bring too many Mexicans to the United States.Footnote 16 Citizens took aim at the president for inciting a war of aggression and questioned the morality of going to war in the interest of territorial expansion and the preservation of slavery.Footnote 17

As Americans grappled with the ethics of their country's position, reports began circulating in newspapers of atrocities committed by American soldiers, including the robbery, rape and murder of Mexican civilians.Footnote 18 General Winfield Scott describes these acts of violence in a letter to the Secretary of War, William L. Marcy: ‘Our militia & volunteers, if a tenth of what is said to be true, have committed atrocities – horrors – in Mexico, sufficient to make Heaven weep, & every American, of Christian morals, blush for his country. Murder, robbery & rape of mothers & daughters, in the presence of the tied up males of the families, have been common all along the Rio Grande’.Footnote 19 Reports of such barbaric acts committed by American soldiers made ‘national news’, contributing to the shifting tides of public opinion.Footnote 20 For instance, the Mercury of Charleston, South Carolina, published a letter written by a soldier, that stated: ‘The majority of the Volunteers sent here, are a disgrace to the nation; think of one of them shooting a woman while washing on the bank of the river – merely to test his rifle; another tore forcibly from a Mexican woman the rings from her ears’.Footnote 21 Although pro-war propaganda still dominated the press, these reports of atrocities fuelled rising disenchantment among civilians.Footnote 22

The increase in opposition to the war also mirrored growing awareness of the conflict's human cost, manifested in losses on both sides. John M. Belohlavek has written in detail about the anxieties experienced by Americans at home, particularly women, during the war between the United States and Mexico. Using diary entries and letters as sources, he demonstrates the predominance of fear among American women about the fate of their loved ones – and all American soldiers – serving in the war to the south.Footnote 23 He reveals that ‘The common anxiety of many women, [was] that of simply not knowing whether a loved one had survived a celebrated contest with heavy casualties’.Footnote 24 Similarly, Peggy Cashion concludes from extensive archival research that most American women opposed the conflict at some point during the war.Footnote 25

With an army of 80,000 drawn from a population of 21 million, most American families did not have personal ties to soldiers in the conflict.Footnote 26 That said, the vivid nature of war reporting contributed to the public's concern about and awareness of the drama unfolding to the south.Footnote 27 Newspapers from throughout the Union had sent reporters to Mexico, and civilians learned about the grave human cost of the war in part from reading the paper. Particularly vivid were the dispatches from the front communicated by journalists via telegraph, bringing information from the front lines, often rendered in highly descriptive prose, to the public; these include the well-known dispatches written by George Wilkins Kendall for the New Orleans Picayune.Footnote 28 This was the first war in which news was communicated via telegraph, and this new technology transformed the experience of civilians following the conflict at home.Footnote 29 They read gruesome accounts of the battlefield in the newspaper, and they also learned details from returning soldiers. Peter Guardino writes:

Even many volunteers who had joined during the war fever found the actual war itself disheartening. They watched friends die violent deaths or waste away with disease in boring camps, and they wondered if it was all worth it. As the vicious conflict with civilians and its endless series of crimes, reprisals, and counter-reprisals raged in northern Mexico, volunteers began to wonder about how the war had changed their friends and neighbours. Reports of the crimes committed by volunteers seeped into the U.S. press, making civilians back home fear the damage that the war was doing to the men's morality.Footnote 30

As soldiers returned to the United States, the human cost of the conflict affected the public greatly. While US forces won every major battle of the campaign, the war had one of the highest casualty rates in American history.Footnote 31 13,283 Americans died, which amounts to 16.87 per cent of American troops who fought in Mexico.Footnote 32 The vast majority of these deaths were the results of illness and disease.Footnote 33 Mexico suffered at least 25,000 deaths, including those of many civilians.Footnote 34 Americans at home, particularly women, saw evidence of trauma as troops returned. As Belohlavek has pointed out, ‘[Women] became more actively engaged as the army shipped the sick and wounded soldiers to the United States. The plight of these returning troops, maimed, ragged, half-starved, caused an outpouring of sympathy in city after city. In Baltimore, women formed a charitable society to help feed the troops, and in Boston an outraged press demanded to know why soldiers were permitted to ‘come home, as it were, in disgrace’.Footnote 35 Belohlavek describes the return of the Massachusetts 1st: ‘Almost a third of the outfit had died in Mexico; the remainder encamped outside Boston in late July, hungry, threadbare, and in “a wretched plight”. Thousands of people visited the site and concluded that the men had been subjected to “brutal treatment” and “cross neglect”’.Footnote 36 The ruthless war had been ingrained in the minds and imaginations of the American public.

Parlour Music and Other Creative Responses to the War with Mexico

Musical works were part of a large body of creative responses to the war with Mexico. In many of these responses, the creators used imagination in the place of first-hand experience, crafting inventive testimonies about the events that they depicted. Some of the more imaginative responses were literary, including poetry, works for the theatre, novelettes and dime novels, all seizing on the public's appetite for war news, which had been fuelled by extensive newspaper coverage. Works of fiction, which were often set in Texas and structured around events related to the war, told tales of adventure, courage and romance, but they also expressed many of the anxieties of the time.Footnote 37 Authors treated Mexicans largely as racialized others, drawing on racist stereotypes and propagating the imperialist ideals of Manifest Destiny and westward expansion.Footnote 38 To this end, they mirrored the pro-war rhetoric of politicians, particularly that of Democrats and those in President Polk's administration. For instance, novelettes about the war frequently included derogatory portrayals of Mexicans as bandits and other similar characters who were untrustworthy threats to social order.

A close reading of these books, however, reveals that they can also be sympathetic toward the enemy. For example, in The Mexican Ranchero (1847), author Charles E. Averill treats the main Mexican character, General Rafael Rejon, sympathetically throughout the novelette. Rejon is a rival of an American military hero, and the two men share numerous similarities, including the tragic deaths of their parents years earlier. During the story, they fall in love with and marry each other's sisters and by the end of the novelette, the two heroes learn that they are actually cousins.Footnote 39 Other fiction of the time also presents some sympathetic – and often chivalrous – Mexican characters. Literary scholar Jaime Javier Rodriguez ties this sympathy to class, with upper-class Mexican characters commanding respect from the works’ authors. He notes, also, that sentiments conveying admiration for the Mexican army's persistence in the fight were circulating in American newspapers of the time.Footnote 40 These differing representations of the enemy, from violent and untrustworthy thieves to valiant members of Americans’ own families, and varied portrayals of the conflict itself, have analogues in the ways that musical works depict the war.

The main genres of parlour music written in response to the Mexican–American War were patriotic songs and dances, laments and battle pieces. Composers included established figures known for both their stage and parlour works, such as Stephen Foster, Charles Grobe and Augusta Browne.Footnote 41 Publishers were also well-known figures in sheet music printing of the day, including W.C. Peters (Cincinnati) and Oliver Ditson (Boston). In other words, musical works about the war were popular entertainment composed for a large audience, and they looked and sounded the part. Like other mass-produced works for the parlour, pieces about the war featured elements like catchy dance tunes and sentimental melodies, perfect for the amateur pianist and her audience. Composers’ interest in the war may have been chiefly opportunistic, attaching references to battles and events of the war to their music as a marketing ploy; many pieces satisfied the public appetite for music about the war with numerous references to patriotism and heroism. Perhaps this explains why some pieces named after a battle seem to have little musically to do with that event. Their composers had not fought in the conflict themselves, but obtained their war news through the newspaper, like most members of the American public. Other works claim a direct connection to the war, with annotations on their title pages declaring that they were heard at the front or composed by a soldier.Footnote 42 This undoubtedly gave audiences a sense of immediacy and a tangible connection to military action, much like newspaper coverage of the conflict, particularly telegraph reporting.

Dances and marches for the piano were a favourite genre of parlour music in mid-nineteenth-century America, and those about the war featured musical elements typical of this repertoire. These popular dances for the keyboard include polkas, waltzes, quick steps and quadrilles, often with titles tying them to a particular location or battle, such as J.A. Frothingham's Buena Vista Quick Step (1848) and J.A. G'schwend's Jalapa Waltz (1851). Some feature dedications to soldiers, officers and regiments, and others claim on their covers to be transcriptions of pieces played at the front. There are also numerous marches related to the war, some of which mimic the sounds of regimental bands. These include Ludwig Hagemann's Gen. Twigg's Grand March (1849) and T.H. Chambers's Grand Triumphant March in the Battle of Palo Alto (1847). Like dances, a number of these, such as Gen. Twigg's Grand March, craft portraits of particular officers noted for their bravery. These musical portraits mythologize the war heroes after whom they are named, reflecting sentiments found throughout pro-war propaganda. Some works were arranged for four-hands piano, a favourite mode of parlour keyboard performance. Examples include W.C. Peters's version of Santa Anna's March (1850) and an arrangement of L. Mey's Monterey by J.C. Viereck (1846). Similarly, patriotic songs, including ‘The Storming of Chapulapec’ (1848) and ‘Cerro Gordo: A New National Song’ (1846), often feature popular dance rhythms, which drive them forward and deliver their messages of support for the war effort with vigour and drive.

Laments, including ‘The Heroine of Monterey’ and ‘The Dying Solider of Buena Vista’, both of which are discussed later in this article, depict the deaths of soldiers on the battlefield, foreshadowing the lamentation ballads for voice and piano of the Civil War.Footnote 43 Their musical language is typical of parlour ballads: generally composed in major modes with long phrases and lilting, sentimental melodies. In contrast, the narratives contained in the texts of laments can be violent and stirring, sometimes depicting the final moments of a young man's life in affecting detail. Many laments focus on the death of a single soldier. He might be a well-known public figure, as is the case in Joseph Turner's ‘The Death of Ringgold’ (1846), which memorializes the final moments in the life of artillery officer Samuel Ringgold, who died at the Battle of Palo Alto.Footnote 44 Other laments depict deaths of fictitious soldiers and civilians; some of these focus on individuals while others emphasize the great number of casualties at certain battles. In a discussion of Civil War lamentation ballads, Richard Leppert writes: ‘These sounds (textual and musical), too easily dismissed as sentimental and cliché-ridden, stay with us for deep-seated social and cultural reasons, however we might choose to judge them as artworks via the troubled (and troublesome) protocols of philosophical aesthetics.’Footnote 45 The ballads of the Mexican–American War share the musical and narrative sentimentality of those from the 1860s, and, like later ballads, they also attest to real pain and grief suffered during the war.

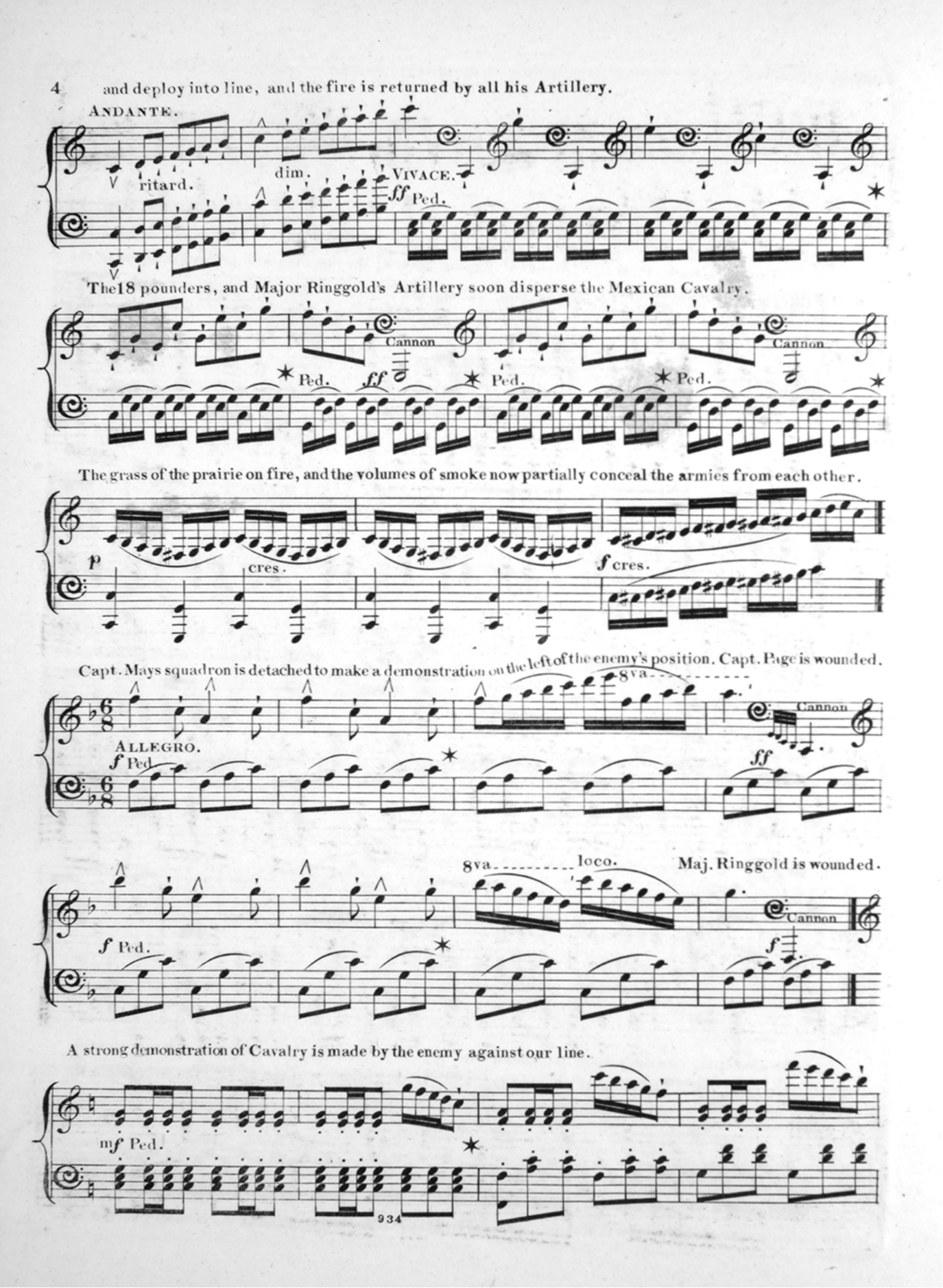

A final genre of sheet music about the war comprises battle pieces: programmatic works depicting fighting at major battles of the war. By the time of the Mexican–American War, battle pieces had a long history of popularity in the United States.Footnote 46 These solo keyboard works represent events such as marching troops, bugle calls, firing guns and canons, battlefield deaths and victory dances.Footnote 47 Many quote well-known patriotic songs. Some are bravura in nature, featuring visual elements like wide leaps and fast fingerwork as elements in their narratives. Often battle pieces have descriptive section headings, which label battlefield action in the score, while others include lengthy texts associated with the war or military. For example, Charles Grobe's ‘The Battles of Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma’ features text adapted from a dispatch written by General Taylor on 16 May 1846 to the ‘Adjutant-General of the Army’, which was published by the media soon after. The use of quotations from a dispatch published in the newspaper attests to the connection between war repertoire and war reporting, demonstrating how both media seek to relay the events of the war to a broad audience in a vivid fashion. It is unclear whether or not pianists would have included this lengthy text in their performances, reciting it from the keys or asking a friend or family member to narrate.Footnote 48 Regardless of whether or not the pianist incorporated them into a performance, such vivid texts would have helped her to truly engage with the reality of the events that she depicted musically.

Witnessing Testimony Through Parlour Music

The creators of musical works about the Mexican–American War, like authors of fiction, generally used imagination in place of first-hand experience as they crafted testimonies about the events they depicted. They represented and translated events at the front, seeking to move their performers and listeners with the emotional impact of their musical language. Many compositions about the war depicted incidents of trauma, portraying soldiers suffering and dying on the battlefield.

Narratives of trauma assuming the guise of witness are an essential way that societies commemorate and process traumatic events like war. These narratives parallel the psychological process of confronting trauma in its aftermath. Drawing on Freud's concept of a latency period, psychologists studying trauma, including Cathy Caruth, Judith Herman, Nicolas Abraham and Maria Torok, have demonstrated how individuals often repress traumatic experiences.Footnote 49 While the memory of a traumatizing event remains deep in the survivor's unconscious, it eventually starts to surface in forms like nightmares and flashbacks. Traumatic memories compel the individual to acknowledge them; as Cathy Caruth puts it, memory of trauma ‘demands our witness’.Footnote 50 Many individuals seek a medium for bearing witness to the experience – and that medium is often creative.

Literary works, as well as music, poetry and visual art about traumatic events, often assume the voice and viewpoint of witness too. These forms of witness give voice to the experiences of survivors and parlay the memory of individual traumatic events to a broad public. In the wake of the world wars and the Holocaust, for instance, the twentieth century saw numerous projects seeking to use individuals’ testimonies to create large-scale representations of and engagement with the collective experiences of survivors.Footnote 51 These projects included some responses in the form of fiction: pieces of literature and narrative films that bore witness to the Holocaust through the lens of fictive imagination.Footnote 52 The comingling of fictive imagination and testimony in the body of responses to the Holocaust has been analysed through the lens of trauma theory by Shoshana Felman and Dori Laub, most notably in Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis, and History. Felman and Laub observe that ‘issues of biography and history are neither simply represented nor simply reflected, but are reinscribed, translated, radically rethought and fundamentally worked over by the text’.Footnote 53 In other words, testimonies perform and construct representations of trauma as they seek to communicate traumatic events to others. In Felman's and Laub's work, these include the testimonies of survivors or primary witnesses themselves.

The personal narratives found in laments of the Mexican–American War also act as a form of testimony, constructing a sense of immediacy and authenticity, even though their creators were generally not primary witnesses. These songs, most of which were written for solo singer with piano accompaniment, narrate traumas from the battlefield, often employing the first-person voice and including vivid eyewitness detail. ‘The Dying Soldier of Buena Vista’, for instance, is narrated from the perspective of a witness whose own observations on the battlefield introduce the song, giving the fictional tale the character of testimony. I borrow here Wlodarski's concept of musical witness. In her work on musical reactions to the Holocaust, Wlodarski defines witness ‘as an intellectual concept that has the potential to inform and guide analytical considerations of secondary musical representations, rather than its more accepted usage of an eyewitness to or a testimonial account of a historical event’.Footnote 54 Wlodarski examines the works of composers who are not primary witnesses or survivors; their musical representations of the Holocaust constitute ‘secondary imaginative accounts’ of trauma.Footnote 55

Wlodarski draws a parallel between Laub's three categories of Holocaust witness and the three kinds of witness she identifies in music. According to Laub, himself a Holocaust survivor and a psychiatrist whose work was foundational to the field of trauma studies, there were three distinct levels of being a witness to the Holocaust: the ‘level of being a witness to oneself within the experience, the level of being a witness to the testimonies of others, and the level of being a witness to the process of witnessing itself’.Footnote 56 Wlodarski poses the idea that there are three similar categories of witness in music: ‘the composer as imaginative witness, the artwork as an expression of that witness, and the audience as the receiving body for the witness performance’.Footnote 57 As musical works represent trauma of the Mexican–American War, they engage these modes of witnessing, which in turn intersect with public discourse about the war. Whether musical works ignite pro-war feelings of patriotism through an emphasis on heroism or anti-war sentiment as they dwell on physical and emotional pain, most pieces assuming the guise of witness offer their interpreters and audience a sense of immediacy in their depiction of the war.

One technique employed by composers to contribute to a feeling of immediacy and testimony is the depiction of battlefield action, with representations of the sounds of firing guns and canons. These depictions also include the representation of death and mourning. Prior to the Mexican–American War, composers of battle pieces, including Americans James Hewitt in his ‘Battle of Trenton’ (1797) and Peter Weldon in the ‘Battle of Baylen’ (c. 1808), often included a section depicting the deaths of soldiers on the battlefield and the grief of their fellow men.Footnote 58 Composers writing battle pieces on the Mexican–American War sometimes followed their lead. John Schell's ‘Battle of Resaca de la Palma’ (1848), for instance, included a brief section entitled ‘Cries of the Wounded’ followed by a lengthier ‘Burial of the Slain’ (Ex. 1). The music in the second section is a lyrical melody written with a homophonic texture, evoking the harmonies and character of a brass or military band. It creates a diegetic soundtrack for the burial scene, which perhaps explains its major mode sonority and peaceful character. This diegetic music contributes to the listener's reception of the work as testimony; the composer has conjured up a feeling of the burial scene by replicating the music that he imagines might have been heard. He expresses his ‘imaginative witness’ in the way he depicts the scene, which in turn fosters the sense of immediacy for the audience, engaging Wlodarski's three subjects – the composer; the artwork or compositional subject; and the audience – as it constructs a musical testimony.

Ex. 1 John Schell, ‘Battle of Resaca de la Palma’ (Baltimore: George Willig Jr., 1848), bars 168–204.

Many battle pieces representing traumatic events at the front employ a sonic language that largely avoids dissonance and the minor mode, offering, instead, depictions of high energy romps across the battlefield in a peppy aural language. This approach is typical to keyboard battle music from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and the sanguine musical affect of these works is also, of course, the favoured musical rhetoric of the parlour itself: domestic audiences typically seek repertoire that is pleasing and light. In ‘The Battle of Buena Vista’ by William Striby, for instance, the composer spends a great deal of time leading up to the battle, during which he employs the typical fare of works in the genre, such as musical evocations of bugle and trumpet calls, drum rolls, and marches of the troops on both sides. The battle itself, however, is just 15 bars in length (Ex. 2). It begins on a diminished seventh chord, but rapidly transitions into a section that swings between the tonic and dominant seventh chord, an alternation it maintains for much of its 15 bars. This simple harmonic vacillation between the tonic and dominant chords is typical of lullabies, hardly what a listener would expect from a piece depicting fighting. Following the battle scene there is a section mimicking drums and fifes playing ‘Yankee Doodle’ and quick steps from both sides.Footnote 59

Ex. 2 William Striby, ‘The Battle of Buena Vista’ (Louisville: H.J. Peters and Co., 1850), bars 94–116.

The unyielding happy affect of battle pieces like ‘The Battle of Buena Vista’ makes these works suitable parlour entertainment while mimicking pro-war propaganda in their optimistic musical language.Footnote 60 We might also understand the unrelenting happiness of battle works by considering the audience for pieces about the war. Scores of wartime keyboard music indicated that the intended consumers for this repertoire – meaning both its performers and listeners – were families. The cover illustration to Parlour Duets, a collection featuring ‘Monterey: A Military Rondino’ by L. Mey (1846), depicts this intended audience. Women and children dominate the wartime parlour, with a man present in this depiction as well. The number of grown women suggests that it might be an extended family or a gathering of friends or neighbours. It also feminizes the space, affirming the parlour's status as women's domain and a refuge from the outside world. Two of the younger children sit side by side at the piano, but the way that the family gathers informally around the instrument, with another child waiting just behind her siblings or friends, suggests that members of the group likely take turns playing the keyboard. (Fig. 1). In this context of family performance, the sanitized musical affect of pieces about the war makes a good deal of sense.Footnote 61 By sharing these works, families, including their youngest members, might participate in a conversation about the war without facing its grimmest realities. Here, the pleasant musical affect works to avoid a sonic representation of trauma when depicting fighting and even death. Similarly, many battle pieces suit the parlour in their upbeat musical affect, transforming the horrors of war into material appropriate for the domestic setting.

Fig. 1 The Parlour Duets for Two Performers on One Piano (Philadelphia: A. Fiot, 1846).

At times, however, pieces of music emphasize the suffering of the battlefield while still affirming the pro-war cause. This is the case in J. Hunter's lament, ‘The Heroine of Monterey’ (1847), which narrates a tale of a Mexican woman tending to a wounded American soldier on the battlefield at Monterrey.Footnote 62 The ‘good and gentle’ woman is struck by a bullet and dies. The American soldiers then bury her, weeping over her loss. This narrative is based on the story of a real woman, María Josefa Zozaya, who brought food and water to both American and Mexican troops at Monterrey, and who was killed while helping an American soldier. The depictions of the battlefield in the song's text are gruesome, emphasizing the trauma of the soldier and the tragic death of Zozaya; the heroine has to ‘bind the bleeding soldier's vein’ and ‘wet his parch'd and fever'd lips’ before she is struck by the ‘booming shot’ that kills her. The song attributes responsibility in large part by contrasting the American troops with Mexico's army, playing up the qualities of sensitivity and earnestness in the US soldiers, whose ‘sighs were breath'd, and tears were shed’ as they ‘wept over her untimely fall’. Meanwhile, the Mexican troops fire the shot that fell ‘with wild rage’. Like some portrayals of Mexicans from fiction of the time, this musical depiction of the enemy mimics racist, pro-war propaganda of the time, suggesting that the enemy soldiers are heartless and solely responsible for the suffering at the scene. In its depiction of a savage enemy and its mode of musical witnessing, this piece mirrors many of the arguments of pro-war politicians, encouraging feelings of moral correctness and racial superiority. The brutality of Mexico's forces was made all the more vivid by the fact that the central protagonist of the song is a Mexican woman herself, and someone who, in the role of selfless caregiver, embodied the gendered values of her time (Ex. 3).Footnote 63

Ex. 3 J. Hunter, ‘The Heroine of Monterey’ (Baltimore: F.D. Benteen, 1847).

Other narratives of battlefield trauma utilize musical witness to emphasize the war's brutality to a different end. Like accounts from war correspondents and returning soldiers, they focus on soldiers’ trauma without emphasizing patriotic fervour. Whittlesey's ‘The Dying Soldier of Buena Vista’, discussed briefly at the opening of this article, for instance, tells the story of two soldiers on the battlefield at Buena Vista. As one of the soldiers is dying, he tells his friend that he is thinking of his family, hoping that his friend will have a chance to tell his parents about his final moments. The F major ballad features a melody reminiscent of folk songs from England, Scotland, and Ireland, delivered over lilting arpeggios in the accompanying piano. The solo piano introduction and interludes are slightly martial in character, giving way to a more lyrical style when the voice enters. The ballad features some surprising moments in the Lydian mode, perhaps meant to conjure a sense of folksiness or even an exotic quality that might represent the foreign setting (Ex. 4).Footnote 64

Ex. 4 Orramel Whittlesey, ‘The Dying Soldier of Buena Vista’ (New York: O. Whittlesey, 1849), bars 35–58.

Although the song's lyrics emphasize the dying soldier's honour and loyalty to his country, this musical testimony stresses suffering above all else. The representations of pain include the physical pain of the injured soldier and the emotional pain of his friend, to whose testimony we are witness. They also gesture to the inevitable suffering of the young man's family as the dying soldier mentions his parents, including his mother's ‘wail’. His metaphor that compares her teardrops to his dripping blood, as well as his mention of the fact that he is an only child, contribute to the agony of the scene. In the final two verses, the soldier moves beyond his family to mention a love interest back home as well; the imagery in this section emphasizes his innocence, and implicitly his youth, as he regrets that he

The works addresses three categories of sufferers: the dying soldier, his friend on the battlefield, and the family and friends at home. By including the soldier's family and friends, ‘The Dying Soldier of Buena Vista’ uses a mode of musical witnessing that addresses parlour listeners and performers themselves. The song invites them to identify with the soldier's family members and friends, who become agents in the drama. They are the cherished community of the soldiers at war and their stake in the scene described before them is imprinted through the sweet conventions of parlour music.

The discord between the lyrical affect and the brutal scene depicted brings the violence of war to the domestic hearth. The pleasant major mode and lyrical affect can be heard as a softening of the violence, but they also invite an oppositional interpretation. Perhaps the conventions of parlour music signify that the parlour itself could not be separated from the brutality of the war: it, too, was home to war's miseries. Heard this way, as emphasizing the war's cruelty and impact on all Americans, the piece can be tied to anti-war rhetoric, which, as discussed earlier in this article, also emphasized the violence of the conflict.

Both the ‘Heroine of Monterey’ and the ‘Dying Solider of Buena Vista’, like other laments, are imaginative representations of battlefield events, where invented details provide the character of eyewitness experience. The story told in ‘The Dying Soldier of Buena Vista’ is, presumably, apocryphal, and the descriptive details in Hunter's ballad are the lyricist's invention. It is in part these invented details that render the narratives so emotionally potent and give them some claim to authenticity; they encourage the performer and audience member to imagine the individual suffering that took place at the battles, with the physical pain and brutality of fighting depicted in graphic terms. That emphasis on trauma might have fired up listeners’ patriotic support of the American cause. Alternatively, the emphasis on violence mirrors the growing focus on the war's brutality in anti-war reporting, which fed disillusion with the brutal, aggressive and contested conflict unfolding to the south.

Embodying Counternarratives in the Performance of Battle Pieces

When we consider not what battle pieces sounded like, but what they looked like to an audience and what they felt like for the pianist performing them, we see further evidence of how the works speak to trauma. A narrative emerges that addresses the harsh realities of war.

Athleticism plays a central role in the performance of battle pieces about the Mexican–American War. The physicality central to playing battle pieces is performative drama, which invites audiences to imagine soldiers’ physical experiences at war. At first glance, many pieces seem to feature the typical fare of intermediate repertoire. They contain scales, often in C Major, Alberti bass and tremolos, arpeggios and repeated figures. However, other musical elements heighten their level of difficulty, and, more importantly, the ways in which the works flaunt their performer's physicality. In ‘The Battles of Palo Alto & Resaca de la Palma’ (1846) by Charles Grobe, for instance, the composer writes numerous leaps at top speed. Beginning in the third bar of Example 5, the hand crossings between treble and bass clefs, marked Vivace, are very difficult to execute at speed without hitting a wrong note. Similarly, the left-hand leaps in Example 6 (Lines 4–5, bars 3–4) are enormously difficult to play without a wrong note if the pianist observes the tempo marking. In his ‘Battle of Buena Vista’, (Example 7, Line 4, from bar 3), Grobe takes the language of the intermediate player – arpeggiated major triads – and transforms it into something very challenging to play without error: unison arpeggios in both hands, marked allegro, that shift harmonies with each measure. William Striby transforms repetitious tremolos in a similar fashion in his ‘Battle of Buena Vista’. Tremolos, while not particularly difficult in themselves, become a test of endurance when written for several continuous bars, even on the lighter action of a nineteenth-century piano. In Striby's ‘Battle of Buena Vista’, the tremolos go on without a break for 12 bars, at which point they transform into semiquaver broken octaves. They also include the inner notes of the chords, requiring the pianist to maintain tension in her fingers. This element, as well as the length of the passage, means that the pianist's forearm will grow tired. Adding to the excitement of the passage, all the while, her left hand jumps back and forth over her right arm (see Ex. 2).

Ex. 5 Charles Grobe, The Battles of Palo Alto & Resaca de la Palma (Baltimore: F.D. Benteen, 1846), bars 22–44.

Ex. 6 Charles Grobe, The Battles of Palo Alto & Resaca de la Palma (Baltimore: F.D. Benteen, 1846), bars 68–89

Ex. 7 Charles Grobe, Battle of Buena Vista (Baltimore: George Willig Jr., 1847), bars 107–127

Of course, the parlour pianist is not under pressure to play perfectly, nor is she necessarily playing for anyone but herself or an audience of a few family members and friends. That said, these battle pieces use the body of their performer as a component of their musical narratives. Her athleticism works to a descriptive end, bringing dramatic narratives to life. Her risks add to the excitement of her performance. If she makes mistakes, hitting wrong notes as she leaps or slowing down during a tremolo passage as her arm grows tired, her pianistic flaws bring the parlour audience's attention to the physical challenges of performing the work.Footnote 65 As the pianist plays, and as her listeners – which might include family members or friends who are pianists themselves – witness the performance of a work that draws attention to the pianist's body, they see a theatrical enactment of battlefield fighting unfold, with the performer's hands flying through the air, jumping from register to register and executing fast scales and arpeggios. The visual elements of performance create ‘theatrical mimesis in which drawing room became battlefield and pianist became soldier’.Footnote 66 Moreover, the physical challenges, necessary endurance and drama suggest the possibility that the performer herself might have identified with the soldiers whom she depicted.

The physical challenges of performing battle music invite what Maria Cizmic has called ‘bodily identification’ between the pianist and the subjects represented in musical compositions. In her work on Galina Ustvolsyaka's final piano sonata, composed in St Petersburg in 1988, Cizmic proposes that the pianist performing the piece remembers and empathizes with the victims of human rights violations during the Soviet Era through the enactment of several physical gestures that induce pain, particularly as she executes harsh tone clusters that can bruise the fingers, fists and forearms.Footnote 67 While Cizmic is careful not to equate the pain of the pianist with the kinds of trauma experienced throughout the Soviet era, she frames the pianist's experience as a form of testimony, which addresses the pain of others through embodiment and raises the possibility of knowing someone else's suffering.Footnote 68 She expands the parameters of empathy to include audience members, who, by imagining the pain of the pianist, might experience ‘bodily empathy’ themselves.Footnote 69 Cizmic places this kind of embodied pain in the context of witnessing, arguing that the sonata ‘bears witness to bodies in pain and functions as a form of testimony’.Footnote 70 It does so in contrast to the ubiquitous political narratives spun by the Russian government in the 1980s, which questioned people's stories of suffering during the Soviet era or recast their trauma as patriotic. Jillian Rogers makes an analogous argument in her analysis of the ‘corporeal struggle’ found in Maurice Ravel's Toccata from Tombeau de Couperin. She argues that the pianist performing the work, which was composed for Marguerite Long as she mourned the death of her husband, experiences physical discomfort that mirrors the pain of grief. In Ravel's piano roll recording of the same movement, the listener can hear his struggle to perform accurately; that struggle is part of the musical meaning conveyed to the listener.Footnote 71

Battle pieces of the Mexican–American War feature a language of pianism that is typical of the nineteenth century, a world apart from that seen in Ustvolsyaka's late-twentieth-century experimental rhetoric and Ravel's compositions for piano. While it is unlikely that these pieces cause the pianist any pain beyond growing tired at times, the physical requirements – endurance, dexterity, accuracy – mean that the drama of the programmatic narratives is manifested in the pianist's body. The physical demands here invite the pianist to imagine the battles she enacts not just as exciting tales of victory, as represented in many acoustic qualities of the works, but as physical events that induced physical reactions in corporeal bodies like her own. As she played battle works into 1847 and after the war ended, she bore witness to the physical tolls of war that she was undoubtedly already aware of, having read about them in national news.

The War's Poison

Ralph Waldo Emerson said of the war with Mexico: ‘The United States will conquer Mexico, but it will be as the man who swallows the arsenic which brings him down in turn. Mexico will poison us.’Footnote 72 Indeed, the war fostered increasing fissures between factions of American society. Just as the media enlightened Americans to the real costs of the war, musical works crafted testimonies that offered complex portraits of the conflict. Even as compositions about the conflict seemed to affirm the pro-war cause, they also fashioned counternarratives focused on the violence and suffering of war. The use of parlour music conventions in laments transported the brutal war to the home, assuming the voice of witness as it addressed the parlour performer and audience. Meanwhile, the performative physicality central to playing battle pieces asked citizens separated from the war to imagine soldiers’ physical experiences – which include pain. As they simultaneously crafted both pro-war narratives and anti-war counternarratives, musical works of the Mexican–American War depicted competing attitudes toward the conflict. They begged their audiences – both in the 1840s and now – to approach them critically, with an awareness of their multiple levels of musical meaning. Their competing narratives also reflected growing partisan divides in the United States, largely along geographic lines, that eventually would lead to the secession of 11 states from the Union. The war with Mexico was indeed a traumatic moment in history, not only because of the traumas experienced by individuals, but because it would contribute to a fundamental breakdown of the Union itself.

Appendix 1: Lyrics to Orramel Whittlesey's ‘The Dying Soldier of Buena Vista’

Appendix 2: Musical Works About the Mexican–American War Mentioned in the Text

An American Officer in Camp. ‘The Storming of Chapulapec’. Philadelphia, PA: E. Ferrett and Co., 1848.

Browne, Augusta. ‘The Mexican Volunteers Quickstep’. New York: C. Holt Junr, 1847.

Chambers, T. H./ Bassford, S. W. ‘Grand Triumphant March in the Battle of Palo Alto’. New York: Atwill, 1847.

Clifton, William. ‘The Banner of the Free: A Duet as Sung by the Alleganians’. New York: Jaques and Brother, 1847.

Foster, Stephen. ‘Santa Anna's Retreat from Buena Vista Quick Step’. Louisville, KY: W.C. Peters & co., 1848.

Frothingham, J.A. ‘Buena Vista Quick Step’. Boston, MA: A. and J.P. Ordway, 1848.

G'Schwend, J. A. ‘Jalapa Waltz’. Baltimore, MD: F.D. Benteen, 1851.

Grobe, Charles. ‘Battle of Buena Vista’. Baltimore, MD: George Willig Jr., 1847.

Grobe, Charles. ‘The Battles of Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma’. Baltimore, MD: F.D. Benteen, 1846.

Hageman, Ludwig. ‘Gen. Twigg's Grand March’. 1849.

Hewitt, John Hill. ‘The Maid of Monterey’. Baltimore, MD: F.D. Benteen, 1851.

Hunter, J. ‘The Heroine of Monterey’. Baltimore, MD: F.D. Benteen, 1847.

Mey, L./ Viereck, J. C. ‘Monterey: A Military Rondino’. Philadelphia, PA: A. Fiot, 1846.

Peters, W.C. (arr). ‘Santa Anna's March’. Cincinnati, OH: W.C. Peters, 1847.

Schell, John. ‘Battle of Resaca de la Palma’. Baltimore, MD: George Willig, Jr., 1848.

Sitgreaves, G. (arr). ‘Cerro Gordo: A New National Song’. New York, NY: Millets Music Saloon, 1847.

Striby, William. ‘The Battle of Buena Vista’. Louisville, KY: H.J. Peters and Co., 1850.

Turner, Joseph. ‘The Death of Ringgold’. Boston, MA: H. Prentiss, 1846.

Whittlesey, Orramel. ‘The Dying Soldier of Buena Vista’. New York: O. Whittlesey, 1849.