Introduction

On 5 March 2020, South Africa reported its first coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) case, which was followed by the detection of clusters of cases and high rates of community transmission (Moonasar et al., Reference Moonasar, Pillay, Leonard, Naidoo, Mngemane, Ramkrishna, Jamaloodien, Lebese, Chetty, Bamford, Tanna, Ntuli, Mlisana, Madikizela, Modisenyane, Engelbrecht, Maja, Bongweni, Furumele, Mayet, Goga, Talisuna, Ramadan and Pillay2021). In response to the pandemic, South Africa introduced a stringent set of restrictions, called (level 5) ‘lockdown’ on 27 March 2020, entailing the suspension of all non-essential activities and a complete ban of tobacco and alcohol sales. On 1 May 2020, restrictions were eased to level 4, allowing people to buy more than essential goods, have food delivered, and exercise outside for a brief period. With the move to level 3 on 1 June 2020, limited alcohol sales were allowed, and more businesses could open, but the beauty and tourism sectors remained closed (Greyling et al., Reference Greyling, Rossouw and Adhikari2021).

The COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns negatively impact the mental health and well-being of the general population (Brooks et al., Reference Brooks, Webster, Smith, Woodland, Wessely, Greenberg and Rubin2020; Winkler et al., Reference Winkler, Formanek, Mlada, Kagstrom, Mohrova, Mohr and Csemy2020; Xiong et al., Reference Xiong, Lipsitz, Nasri, Lui, Gill, Phan, Chen-Li, Iacobucci, Ho, Majeed and McIntyre2020; Liao et al., Reference Liao, Fan, Zhang, Guo, Lee, Wang, Li, Gong, Lui, Li, Lu and McIntyre2021). A systematic review reported high rates of symptoms of anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic (Xiong et al., Reference Xiong, Lipsitz, Nasri, Lui, Gill, Phan, Chen-Li, Iacobucci, Ho, Majeed and McIntyre2020). Fear and uncertainty associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, and the drastic implications of the response to the pandemic on people's life and the economy, including social isolation, loneliness, confinement, physical inactivity, frustration, boredom, limited access to basic supplies and services, loss of jobs and financial worries, exacerbate the risk of incident of mental health disorders and the severity of existing mental health conditions (Moreno et al., Reference Moreno, Wykes, Galderisi, Nordentoft, Crossley, Jones, Cannon, Correll, Byrne, Carr, Chen, Gorwood, Johnson, Kärkkäinen, Krystal, Lee, Lieberman, López-Jaramillo, Männikkö, Phillips, Uchida, Vieta, Vita and Arango2020).

There is increasing evidence suggesting that the response to the COVID-19 pandemic led to a disruption of health services. Several studies, mainly from Europe, North America and Asia, reported a substantial decrease in the rates of emergency department visits (Jeffery et al., Reference Jeffery, D'Onofrio, Paek, Platts-Mills, Soares, Hoppe, Genes, Nath and Melnick2020; Wongtanasarasin et al., Reference Wongtanasarasin, Srisawang, Yothiya and Phinyo2021) and hospital admissions for acute medical conditions including cardiovascular diseases (Esenwa et al., Reference Esenwa, Parides and Labovitz2020; Pelletier et al., Reference Pelletier, Rakkar, Au, Fuhrman, Clark and Horvat2021) and mental health problems (Boldrini et al., Reference Boldrini, Girardi, Clerici, Conca, Creati, Di Cicilia, Ducci, Durbano, Maci, Maone, Nicolò, Oasi, Percudani, Polselli, Pompili, Rossi, Salcuni, Tarallo, Vita and Lingiardi2021; Gómez-Ramiro et al., Reference Gómez-Ramiro, Fico, Anmella, Vázquez, Sagué-Vilavella, Hidalgo-Mazzei, Pacchiarotti, Garriga, Murru, Parellada and Vieta2021; McDowell et al., Reference McDowell, Fry, Nisavic, Grossman, Masaki, Sorg, Bird, Smith and Beach2021; Wyatt et al., Reference Wyatt, Mohammed, Fisher, McConkey and Spilsbury2021) following the introduction of COVID-19 lockdowns. The effect of COVID-19 related lockdowns on outpatient care is less well researched. Studies from high-income countries report reduced outpatient care contacts for physical and mental health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Jenkins, Ashcroft, Brown, Campbell, Carr, Cheraghi-sohi, Kapur, Thomas, Webb and Peek2020; Mansfield et al., Reference Mansfield, Mathur, Tazare, Henderson, Mulick, Carreira, Matthews, Bidulka, Gayle, Forbes, Cook, Wong, Strongman, Wing, Warren-Gash, Cadogan, Smeeth, Hayes, Quint, McKee and Langan2021; Seo et al., Reference Seo, Kim, Lee and Kang2021). Less is known from the low- and middle-income country context (Knipe et al., Reference Knipe, Silva, Aroos, Senarathna, Hettiarachchi, Galappaththi, Spittal, Gunnell, Metcalfe and Rajapakse2021; Kola et al., Reference Kola, Kohrt, Hanlon, Naslund, Sikander, Balaji, Benjet, Cheung, Eaton, Gonsalves, Hailemariam, Luitel, Machado, Misganaw, Omigbodun, Roberts, Salisbury, Shidhaye, Sunkel, Ugo, van Rensburg, Gureje, Pathare, Saxena, Thornicroft and Patel2021). A study from South Africa found a sharp decline in HIV testing and antiretroviral therapy initiation rates but no decline in antiretroviral therapy collection visits in primary care HIV clinics after the introduction of the lockdown (Dorward et al., Reference Dorward, Khubone, Gate, Ngobese, Sookrajh, Mkhize, Jeewa, Bottomley, Lewis, Baisley, Butler, Gxagxisa and Garrett2021). The effect of the lockdown on inpatient and outpatient mental health care utilisation in African countries is unclear.

We aimed to quantify the impact of the introduction of the lockdown (levels 5 and 4) on mental health care utilisation in private sector care in South Africa. We assessed the effect of lockdown measures on weekly hospital admission and outpatient consultation rates for selected mental disorders. In addition, we tested the hypothesis that the ban on alcohol sales led to an increased rate of hospital admissions and outpatient consultations for alcohol withdrawal syndrome.

Methods

Study design

We conducted an interrupted time-series analysis on the effects of the level 5 and 4 COVID-19 lockdowns on mental health care use in South Africa's private health sector using outpatient and hospital claim data with corresponding ICD10 diagnoses from a large private sector medical scheme. We analysed data from 1 January 2017 to 28 June 2020. We adopted the study design from a previous study evaluating the effect of COVID-19 measures on health care use in the UK (Mansfield et al., Reference Mansfield, Mathur, Tazare, Henderson, Mulick, Carreira, Matthews, Bidulka, Gayle, Forbes, Cook, Wong, Strongman, Wing, Warren-Gash, Cadogan, Smeeth, Hayes, Quint, McKee and Langan2021). The Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Cape Town and the Cantonal Ethics Committee of the Canton of Bern granted permission to analyse the data.

Study population

We followed beneficiaries of one of South Africa's largest open medical schemes that insured over 700 000 individuals as of 2019 (Council for Medical Schemes, 2020). It has a young membership base with an average age of about 33 (Council for Medical Schemes, 2020). We included beneficiaries aged 18 years or older who had an active health care plan between 1 January 2017, and 28 June 2020. Individuals with missing information on sex or age were excluded. Follow-up ended at the termination of the insurance contract, the date of death, or the end date of the study period.

Exposures, outcomes and stratifying variables

The exposure of interest was the introduction of the national lockdown in South Africa on 27 March 2020. We defined the start of the lockdown as the beginning of week 14 (30 March 2020).

Outcomes were the proportion of beneficiaries (1) admitted to a hospital, (2) consulting outpatient care, or (3) receiving any mental health care (either being admitted to a hospital or consulting outpatient care) for selected mental disorders. The South African Health Profession Council embraced telemedicine to overcome shortages in health care delivery and to protect health care staff on 26 March 2020. With the amendments of 3 April 2020, telemedicine could also be used for first-time consultations and allowed for reimbursement for telemedical services through the insurance system (Kwinda, Reference Kwinda2020). Our definition of outpatient care consultations, therefore, included both, in-person and telemedical consultations.

We identified mental disorders based on ICD10 diagnoses from outpatient and hospital claims: organic mental disorders (ICD10 codes F00-09), substance use disorders (F10-F19), serious mental disorders such as Schizophrenia spectrum disorders, psychotic, delusional, or bipolar disorders (F20-F29 and F31), depressive disorders (F32, F34.1 and F54) anxiety and related disorders (F40-F48), other mental disorders like a single manic episode, persistent mood affective disorders, eating disorders, sleep disorders, or unspecified mental disorders (F30, F34.0, F34.8, F34.9, F50-F99), and alcohol withdrawal syndrome (F10.3 and F10.4). Finally, we defined any mental disorder as being diagnosed with any ICD10 F00-F99 diagnosis and self-harm as being diagnosed with any ICD10 X60-X84 diagnosis.

Statistical analysis

We described the sociodemographic characteristics of the study population under follow-up on 1 January of each year using summary statistics. We calculated and plotted weekly mental health care utilisation rates defined as the percentage of beneficiaries receiving care for a defined condition in each week between 1 January 2017, and 28 June 2020.

We conducted interrupted time-series analyses to assess changes in weekly mental health care utilisation rates during the level 5 and 4 COVID-19 lockdowns. In these analyses, we did not use data from the last four weeks before database closure (1 June 2020–28 June 2020) to account for delays in reporting. In addition, we did not use data from weeks 12 to week 13 (15 March–29 March 2020) to account for the anticipatory behaviour of beneficiaries following the announcement of the National State of Disaster in South Africa on 15 March 2020. The interrupted time-series analysis assumes that under the counterfactual scenario, the pre-lockdown time series continues during the lockdown and compares the extrapolated pre-lockdown time series to the observed post-lockdown time series. We modelled weekly health care utilisation rates using binomial generalised linear regression models with logit link and robust standard errors (Papke and Wooldridge, Reference Papke and Wooldridge1996). Models included a linear effect of time and an indicator variable for calendar months to account for long-term trends and seasonal variation in mental health care use. In addition, models included a binary indicator for the lockdown to measure the immediate change in health care use following the introduction of the lockdown and an interaction term between time and the binary indicator to measure the slope change in health care use during the lockdown (Mansfield et al., Reference Mansfield, Mathur, Tazare, Henderson, Mulick, Carreira, Matthews, Bidulka, Gayle, Forbes, Cook, Wong, Strongman, Wing, Warren-Gash, Cadogan, Smeeth, Hayes, Quint, McKee and Langan2021). Results are presented as odds ratios (ORs) for the immediate effect of the lockdown on mental health care use and for the weekly change in the utilisation during the lockdown period (Mansfield et al., Reference Mansfield, Mathur, Tazare, Henderson, Mulick, Carreira, Matthews, Bidulka, Gayle, Forbes, Cook, Wong, Strongman, Wing, Warren-Gash, Cadogan, Smeeth, Hayes, Quint, McKee and Langan2021). We stratified interrupted time-series analysis of the change in mental health care use for any mental disorders by sex. In sensitivity analysis, we implemented the model used by Mansfield and colleagues and compared the results to our primary analysis (Mansfield et al., Reference Mansfield, Mathur, Tazare, Henderson, Mulick, Carreira, Matthews, Bidulka, Gayle, Forbes, Cook, Wong, Strongman, Wing, Warren-Gash, Cadogan, Smeeth, Hayes, Quint, McKee and Langan2021). The Mansfield model uses conventional standard errors and adjusts for autocorrelation by including first-order lagged residuals (Mansfield et al., Reference Mansfield, Mathur, Tazare, Henderson, Mulick, Carreira, Matthews, Bidulka, Gayle, Forbes, Cook, Wong, Strongman, Wing, Warren-Gash, Cadogan, Smeeth, Hayes, Quint, McKee and Langan2021). Finally, to validate our model, we performed the same interrupted time-series analysis (week 14–22) of mental health care utilisation for 2019, expecting no changes in this period. We implemented the Mansfield model in R version 4.1.1 (R Core Team, 2021). All other analyses were done in Stata version 16 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Statistical code is available under https://github.com/AndreasDHaas/ECMHC.

Results

Of 1 013 033 beneficiaries who had an active health care plan with the medical insurance scheme during the study period, 710 367 were eligible for analysis. We excluded 296 155 children and adolescents aged 17 years or younger at the end of their follow-up and 6511 beneficiaries with incomplete data on sex and age. The median follow-up time was 153 weeks [interquartile range (IQR) 57–178]. At the beginning of 2017, 53% of the study population were women, and the median age was 43 years (IQR 32–56) (Table 1). The number of beneficiaries, and their age, sex, and population group distributions, remained relatively stable throughout the study period.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study population at the beginning of each year, 2017–2020

IQR, Interquartile range.

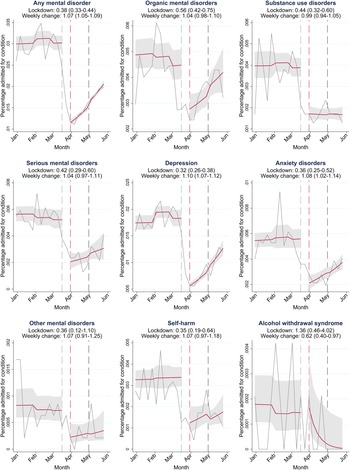

Results from the interrupted time-series analysis on the effect of the COVID-19 lockdown on psychiatric hospital admission are shown in Fig. 1. Overall, hospital admission rates for any mental disorder (ICD10 codes F00-F99) decreased substantially after the introduction of the lockdown (OR 0.38; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.33–0.44) and did not recover to pre-lockdown levels until 1 June 2020 (Fig. 1). Admission rates for all groups of mental disorders (i.e. organic mental disorders, substance use disorders, serious mental disorders, depression and anxiety disorders) and self-harm decreased substantially after the introduction of the lockdown. Admission rates for alcohol withdrawal syndrome increased after the introduction of the lockdown (OR 1.36; 95% CI 0.46–4.02).

Fig. 1. Interrupted time-series analysis for changes in hospital admissions during the lockdown. Solid grey lines represent percentages of the study population admitted for the condition in each week between 1 January 2020, and 1 June 2020. Solid red lines depict the estimated average percentage admitted per week with 95% confidence intervals (grey shaded areas). Area between the dashed grey and dashed red line: data not used to account for anticipatory behaviour. Dashed red line: first Monday during lockdown level 5 (30 March 2020). Dashed black line: beginning of lockdown level 4 (30 April 2020). Lockdown: odds ratios (OR) for the immediate effect of the lockdown on admission rates. Weekly change: OR for the weekly change in the odds of hospital admission during the lockdown (week 14–22 in 2020). 95% confidence intervals for ORs in parentheses.

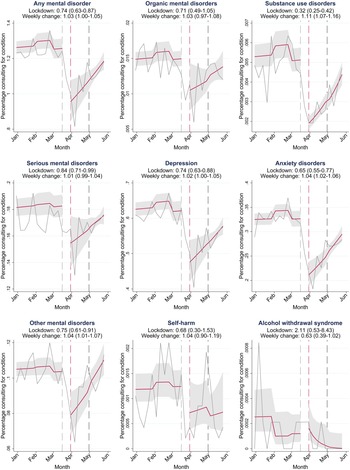

Results from the interrupted time-series analysis on the effect of the COVID-19 lockdown on outpatient consultation rates are shown in Fig. 2. Overall, outpatient consultation rates for any mental disorder (ICD10 F00-F99) decreased after the introduction of the lockdown (OR 0.74; 95% CI 0.63–0.87) and did not fully recover to pre-pandemic levels during the study period (Fig. 2). There was no strong evidence of an effect of the lockdown on outpatient consultation rates for self-harm. Rates of outpatient consultations for alcohol withdrawal syndrome doubled after the introduction of the lockdown, but the statistical uncertainty around the estimates was large (OR 2.11; 95% CI 0.53–8.43). Outpatient consultation rates for all groups of mental disorders increased after the initial drop, but rates for alcohol withdrawal syndrome declined during the lockdown.

Fig. 2. Interrupted time-series analysis for changes in outpatient consultations during the lockdown. Solid grey lines represent percentages of the study population consulting outpatient care for the condition in each week between 1 January 2020, and 1 June 2020. Red lines depict the estimated average percentage consulting outpatient care per week with 95% CIs (grey shaded areas). Area between the dashed grey and dashed red line: data not used to account for anticipatory behaviour. Dashed red line: first Monday during lockdown (30 March 2020). Dashed black line: beginning of lockdown level 4 (30 April 2020). Lockdown: odds ratios (OR) for the immediate effect of the lockdown on outpatient consultation rates. Weekly change: OR for the weekly change in the odds of outpatient consultation rates during the lockdown (week 14–22 in 2020). 95% confidence intervals for ORs in parentheses.

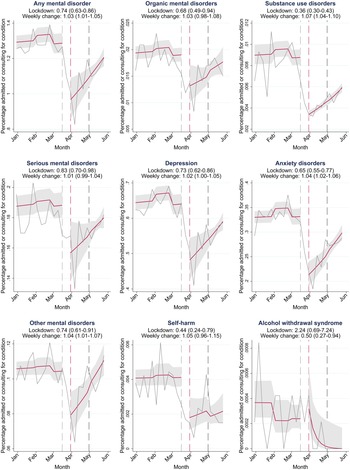

Results from the interrupted time-series analysis on the effect of the lockdown on the overall mental health care utilisation rates including hospital admission and outpatient consultation rates are shown in Fig. 3. Similar to outpatient consolation rates, overall mental health care utilisation rates for any mental disorders (ICD10 codes F00-F99) decreased after the introduction of the lockdown (OR 0.74; 95% CI 0.63–0.86) and did not fully recover to pre-pandemic levels during the study period. The combined rates of hospital admissions and outpatient care consultations for alcohol withdrawal syndrome doubled after the introduction of the lockdown, but the statistical uncertainty around the estimates of the combined rates remained large (OR 2.24; 95% CI 0.69–7.24).

Fig. 3. Interrupted time-series analysis for changes in mental health care use during the lockdown. Solid grey lines represent percentages of the study population admitted to a hospital or consulting outpatient care for condition in each week between 1 January 2020, and 1 June 2020. Red lines depict the estimated average percentage admitted or consulting outpatient care for the condition in a week with 95% CIs (grey shaded areas). Area between the dashed grey and dashed red line: data not used to account for anticipatory behaviour. Dashed red line: first Monday during lockdown (30 March 2020). Dashed black line: beginning of lockdown level 4 (30 April 2020). Lockdown: odds ratios (OR) for the immediate effect of the lockdown on hospital admission and outpatient consultation rates. Weekly change: OR for the weekly change in the odds of hospital admission and outpatient consultation rates during the lockdown (week 14–22 in 2020). 95% confidence intervals for ORs in parentheses.

Decreases in mental health care use for any mental disorder were slightly greater in men (OR 0.39; 95% CI 0.30–0.53) than in women (OR 0.44; 95% CI 0.37–0.52) (online Supplementary Fig. S1). The effect of the lockdown on outpatient consultations was also slightly more pronounced in men (OR 0.77; 95% CI 0.65–0.91) than in women (OR 0.79; 95% 0.68–0.92).

The results from the sensitivity analysis in which we implemented the statistical model developed by Mansfield and colleagues were comparable to the results of our primary analysis (online Supplementary Table S1). In further sensitivity analysis, we showed that, as expected, there was no evidence for changes in mental health care utilisation in the same period in 2019 (weeks 14–22) as the lockdown was introduced in 2020 (online Supplementary Table S2).

Observed weekly hospital admissions rates, outpatient consultation rates and overall mental health care utilisation rates for each of the conditions in each week between 1 January 2017, and 28 June 2020 are shown in the online Appendix (Supplementary Figs S2–S4).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study examining the effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on mental health care utilisation in an African country. Hospital admission, outpatient consultation rates and overall mental health care utilisation rates for mental disorders decreased after the introduction of the COVID-19 lockdown measures in South Africa in March 2020. The drop in rates was larger for hospital admissions than for outpatient consultations. We demonstrated that hospital admissions and outpatient care consultations for mental disorders dropped simultaneously, thereby excluding the possibility that either absorbed drops in the other. For most conditions, mental health care utilisation rates did not recover to pre-pandemic levels by 1 June 2020. Hospital admissions and outpatient consultations for alcohol withdrawal syndrome increased following the ban on alcohol sales in South Africa, but the statistical uncertainty around these estimates was too large to draw definite conclusions.

Our estimates of the magnitude of reductions in mental health care contacts during the lockdown are similar to estimates reported in other settings. A study from South Korea reported reductions in outpatient care visits for depression, anxiety disorders and serious mental disorders close to our estimates of 15% to 30% reduction (Seo et al., Reference Seo, Kim, Lee and Kang2021). A study from the UK reported a slightly higher reduction in psychiatric outpatient care visits from 20 to 46% (Mansfield et al., Reference Mansfield, Mathur, Tazare, Henderson, Mulick, Carreira, Matthews, Bidulka, Gayle, Forbes, Cook, Wong, Strongman, Wing, Warren-Gash, Cadogan, Smeeth, Hayes, Quint, McKee and Langan2021). Our estimate of the decline in psychiatric hospital admissions of 58% corresponds to a Canadian study that reported a 56–60% decline in psychiatric emergency presentations in children and adolescents (Finkelstein et al., Reference Finkelstein, Maguire, Zemek, Osmanlliu, Kam, Dixon, Desai, Sawyer, Emsley, Lynch, Mater, Schuh, Rumantir and Freedman2021). A study from Germany reported a lower reduction in psychiatric hospitalisations of 25% following the introduction of COVID-19 measures (Zielasek et al., Reference Zielasek, Vrinssen and Gouzoulis-Mayfrank2021).

Substantial reductions in health care utilisation rates likely represent a large unmet need for mental health care. It is unlikely that lower rates of health care utilisation reflect a decrease in underlying disease prevalence, given the evidence that COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns negatively impact mental health, with several countries reporting increased rates of mental illness and psychological distress during the pandemic (Brooks et al., Reference Brooks, Webster, Smith, Woodland, Wessely, Greenberg and Rubin2020; Xiong et al., Reference Xiong, Lipsitz, Nasri, Lui, Gill, Phan, Chen-Li, Iacobucci, Ho, Majeed and McIntyre2020; Santomauro et al., Reference Santomauro, Mantilla Herrera, Shadid, Zheng, Ashbaugh, Pigott, Abbafati, Adolph, Amlag, Aravkin, Bang-Jensen, Bertolacci, Bloom, Castellano, Castro, Chakrabarti, Chattopadhyay, Cogen, Collins, Dai, Dangel, Dapper, Deen, Erickson, Ewald, Flaxman, Frostad, Fullman, Giles, Giref, Guo, He, Helak, Hulland, Idrisov, Lindstrom, Linebarger, Lotufo, Lozano, Magistro, Malta, Månsson, Marinho, Mokdad, Monasta, Naik, Nomura, O'Halloran, Ostroff, Pasovic, Penberthy, Reiner, Reinke, Ribeiro, Sholokhov, Sorensen, Varavikova, Vo, Walcott, Watson, Wiysonge, Zigler, Hay, Vos, Murray, Whiteford and Ferrari2021). The unmet need for mental health care may have long-term consequences for people with mental illness and their families. Untreated serious mental disorders, including psychotic disorders and bipolar disorder, can lead to legal, social, emotional and financial problems or suicide (Altamura et al., Reference Altamura, Dell'Osso, Berlin, Buoli, Bassetti and Mundo2010; Penttilä et al., Reference Penttilä, Jaä̈skel̈ainen, Hirvonen, Isohanni and Miettunen2014). Timely treatment of mental disorders with a high prevalence, including anxiety disorders and depression, is also important. Patients with depression receiving timely treatment have better clinical outcomes and a faster recovery, higher stability in life and better social functioning (Ghio et al., Reference Ghio, Gotelli, Cervetti, Respino, Natta, Marcenaro, Serafini, Vaggi, Amore and Belvederi Murri2015). Untreated anxiety disorders tend to recur over time and increase in symptom severity (Craske and Stein, Reference Craske and Stein2016). Long-term consequences of untreated anxiety disorders may include social isolation, suicidality, substance abuse and physical comorbidity (Benatti et al., Reference Benatti, Camuri, Dell'Osso, Cremaschi, Sembira, Palazzo, Oldani, Dobrea, Arici, Primavera, Carpiniello, Castellano, Carrà, Clerici, Baldwin and Altamura2016; Craske and Stein, Reference Craske and Stein2016).

The less pronounced decreases in the rate of outpatient consultations compared to hospital admissions might be explained by the shift from in-person consultations to telemedicine. Before the lockdown, health insurances would only reimburse in-person consultations, but this regulation was revised during the lockdown (Kinoshita et al., Reference Kinoshita, Cortright, Crawford, Mizuno, Yoshida, Hilty, Guinart, Torous, Correll, Castle, Rocha, Yang, Xiang, Kølbæk, Dines, ElShami, Jain, Kallivayalil, Solmi, Favaro, Veronese, Seedat, Shin, Salazar de Pablo, Chang, Su, Karas, Kane, Yellowlees and Kishimoto2020). According to a recently published study, in South Africa, 60% of patients used telepsychiatry, and 70% of psychiatrists practised telepsychiatry as of May 2020 (Kinoshita et al., Reference Kinoshita, Cortright, Crawford, Mizuno, Yoshida, Hilty, Guinart, Torous, Correll, Castle, Rocha, Yang, Xiang, Kølbæk, Dines, ElShami, Jain, Kallivayalil, Solmi, Favaro, Veronese, Seedat, Shin, Salazar de Pablo, Chang, Su, Karas, Kane, Yellowlees and Kishimoto2020). Nevertheless, the 25% reduction in outpatient consultations observed in this study still leaves a substantial void for many patients. On the upside, comparatively modest reductions in outpatient care compared to inpatient care could also signify that telepsychiatry services have the potential to ensure access to mental health care during lockdowns. Telepsychiatry outpatient care can also ensure access to prescription medicines, as doctors were also allowed to prescribe medication via telepsychiatry services (Kinoshita et al., Reference Kinoshita, Cortright, Crawford, Mizuno, Yoshida, Hilty, Guinart, Torous, Correll, Castle, Rocha, Yang, Xiang, Kølbæk, Dines, ElShami, Jain, Kallivayalil, Solmi, Favaro, Veronese, Seedat, Shin, Salazar de Pablo, Chang, Su, Karas, Kane, Yellowlees and Kishimoto2020).

Our estimate of the unintended effect of the ban on alcohol sales on health care contacts for alcohol withdrawal syndrome is broadly consistent with a study from India showing a doubling in hospital presentations for the management of alcohol withdrawal syndrome following the ban on alcohol sales. Although the statistical uncertainty of our estimate is too large to draw definite conclusions, it is remarkable that health care utilisation rates for alcohol withdrawal syndrome potentially doubled while rates for all mental disorders dropped. Further research is needed to evaluate the potential unintended effects of the alcohol sales ban on health outcomes.

Strengths of our study include the large sample size, longitudinal data with extended pre-pandemic follow-up, and the quasi-experimental study design. The use of a large national private-sector care database enabled us to study the effect of the lockdowns on health care utilisation for uncommon serious mental disorders. The long pre-pandemic follow-up allowed us to compare trends of the previous three years to 2020. Although we worked with observational data, the use of interrupted time series models allowed for a quasi-experimental design, taking full advantage of the longitudinal nature of the data, and allowing for adjustment for long-term temporal trends and seasonality in health care utilisation. Finally, our findings were robust in several sensitivity analyses.

Our results have to be considered in light of the following limitations. First, we could not study the recovery of service utilisation as restrictions were eased to lockdown level 3 in July 2020 because our study period ended in end-June 2020. Second, our study only included data from a private-sector medical insurance scheme, and thus our findings are not necessarily applicable to the public sector. Third, we could not distinguish between in-person and virtual outpatient care consultations and therefore could not evaluate to what degree telemedicine compensated for drops in in-person outpatient care consultations. Fourth, since we used routine insurance claim data, we cannot exclude the possibility that changes to administrative procedures or reimbursement practices that may have occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic have influenced our results. Fifth, we had no information on the geographic location of health care providers or the residence of beneficiaries and could not examine regional differences in health care utilisation.

Further studies are needed to examine the underlying mechanisms that limited access to mental health care during the lockdown. Such mechanisms may include changes in the care-seeking behaviour of patients, transport-related and financial barriers, decreased psychiatric bed capacity to reduce the risk of in-hospital COVID-19 transmission, and other changes in service delivery possibly due to the reallocation of health care staff to care for COVID-19 patients. In addition, qualitative work is needed to understand how people living with mental illness and their primary care-takers coped without access to mental health care – whether they self-managed or sought support from social networks, traditional healers, or religious communities (Kola et al., Reference Kola, Kohrt, Hanlon, Naslund, Sikander, Balaji, Benjet, Cheung, Eaton, Gonsalves, Hailemariam, Luitel, Machado, Misganaw, Omigbodun, Roberts, Salisbury, Shidhaye, Sunkel, Ugo, van Rensburg, Gureje, Pathare, Saxena, Thornicroft and Patel2021). Future studies should also evaluate the long-term consequences of delayed mental health treatment due to COVID-19 lockdowns on clinical outcomes. Finally, strategies for delivering essential mental health services during pandemics are a critical area for future research.

Conclusions

Mental health care utilisation rates for inpatient and outpatient services decreased substantially after the introduction of the lockdown. Hospital admissions and outpatient consultations for alcohol withdrawal syndrome increased after the introduction of the lockdown, but statistical uncertainty precludes strong conclusions about this potential unintended effect of the alcohol sales ban. Governments should integrate strategies for ensuring access and continuity of essential mental health services during lockdowns in pandemic preparedness planning.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796022000270.

Data

All data were obtained from the IeDEA-SA. Data cannot be made available online because of legal and ethical restrictions. To request data, readers may contact IeDEA-SA for consideration by filling out the online form available at https://www.iedea-sa.org/contact-us/. Statistical code and simulated data are available under https://github.com/AndreasDHaas/ECMHC.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mansfield and colleagues (Mansfield et al., Reference Mansfield, Mathur, Tazare, Henderson, Mulick, Carreira, Matthews, Bidulka, Gayle, Forbes, Cook, Wong, Strongman, Wing, Warren-Gash, Cadogan, Smeeth, Hayes, Quint, McKee and Langan2021) for making their statistical code publicly available.

Author contributions

A. H. and A. W. wrote the first draft of the study protocol. All authors contributed to the final version of the protocol. N. M. prepared the database. A. H. and A. W. performed the statistical analysis. A. W. and A. H. wrote the first draft of the manuscript, which was revised by all authors. All authors approved the final version of the paper for submission.

Financial support

This study is supported by the US National Institutes of Health (the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and the Fogarty International Center) under award number U01AI069924 (Drs Egger and Davies). Dr Haas was supported by an Ambizione Fellowship (award number 193381) and Dr Egger by special project funding (award number 189498) from the Swiss National Science Foundation.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.