Introduction

Stigma and discrimination are a complex and multifaceted phenomenon conceptualised in various ways across disciplines and literature. Conceptualisation of stigma includes problems related to knowledge (ignorance), attitude (prejudice) and behaviour (discrimination) (Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Rose, Kassam and Sartorius2007). This definition is evident also in how stigma is assessed using measures capturing these aspects of knowledge (e.g. Mental Health Knowledge Schedule (Evans-Lacko et al., Reference Evans-Lacko, Little, Meltzer, Rose, Rhydderch, Henderson and Thornicroft2010)), attitudes (e.g. Community Attitudes to Mental Illness scale (Wolff et al., Reference Wolff, Pathare, Craig and Leff1996)) and behaviour (e.g. Reported and Intended Behaviour Scale (Evans-Lacko et al., Reference Evans-Lacko, Rose, Little, Flach, Rhydderch, Henderson and Thornicroft2011)).

Stigma and discrimination may vary between cultures but are prevalent in all regions of the world (Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Brohan, Rose, Sartorius and Leese2009; Koschorke et al., Reference Koschorke, Evans-Lacko, Sartorius and Thornicroft2017; Winkler et al., Reference Winkler, Krupchanka, Roberts, Kondratova, Machů, Höschl, Sartorius, Van Voren, Aizberg and Bitter2017; Aliev et al., Reference Aliev, Roberts, Magzumova, Panteleeva, Yeshimbetova, Krupchanka, Sartorius, Thornicroft and Winkler2021). Stigma is a major part of frequently experienced personal distress, systematic disadvantages, economic loss and social exclusion linked to mental illness globally. The negative impacts of stigma can have widespread effects on the personal (Corrigan et al., Reference Corrigan, Watson and Barr2006; Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Brohan, Rose, Sartorius and Leese2009), social (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Kleinman, Link, Phelan, Lee and Good2007; Gonsalves et al., Reference Gonsalves, Hodgson, Michelson, Pal, Naslund, Sharma and Patel2019), economic (Sharac et al., Reference Sharac, Mccrone, Clement and Thornicroft2010) and other (Clement et al., Reference Clement, Brohan, Sayce, Pool and Thornicroft2011, Reference Clement, Schauman, Graham, Maggioni, Evans-Lacko, Bezborodovs, Morgan, Rüsch, Brown and Thornicroft2015) aspects of lives of people with mental health needs. Also, stigma and discrimination have important implications in policy with low investment, and political commitment towards mental healthcare programmes (Saraceno et al., Reference Saraceno, Van Ommeren, Batniji, Cohen, Gureje, Mahoney, Sridhar and Underhill2007) which reflect structural stigma (Pescosolido and Martin, Reference Pescosolido and Martin2015).

Strategies to reduce mental health-related stigma can use education, protest or social contact approaches (Corrigan et al., Reference Corrigan, River, Lundin, Penn, Uphoff-Wasowski, Campion, Mathisen, Gagnon, Bergman and Goldstein2001). Educational approaches targeting knowledge and beliefs about mental health-related problems have been shown to be effective and widely used (Mehta et al., Reference Mehta, Clement, Marcus, Stona, Bezborodovs, Evans-Lacko, Palacios, Docherty, Barley and Rose2015; Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Mehta, Clement, Evans-Lacko, Doherty, Rose, Koschorke, Shidhaye, O'reilly and Henderson2016; Rao et al., Reference Rao, Elshafei, Nguyen, Hatzenbuehler, Frey and Go2019). Protest strategies challenge negative representation and images of mental illness and people with mental health needs (Corrigan et al., Reference Corrigan, River, Lundin, Penn, Uphoff-Wasowski, Campion, Mathisen, Gagnon, Bergman and Goldstein2001). However, evidence on their effectiveness is limited (Corrigan et al., Reference Corrigan, Morris, Michaels, Rafacz and Rüsch2012). Social contact involves contact between the stigmatised group and those displaying stigmatising attitudes, knowledge or behaviour (London and Evans-Lacko, Reference London and Evans-Lacko2010), and is the most effective type of intervention to reduce mental health-related stigma and discrimination (Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Mehta, Clement, Evans-Lacko, Doherty, Rose, Koschorke, Shidhaye, O'reilly and Henderson2016).

Social contact interventions targeting mental health-related stigma take various forms and cover a range of intervention types. More recently, indirect social contact (ISC) interventions that do not entail in-person face-to-face contact have been developed and evaluated. ISC interventions have been broadly divided into those occurring through: (i) another person (e.g. someone who knows a person with mental health needs), (ii) media (e.g. the Internet) or (iii) imagined contact, or having passive or active interaction with ISC media (e.g. discussing videos or vignettes) (Paolini et al., Reference Paolini, White, Tropp, Turner, Page-Gould, Barlow, Gomez, Borinca, Vezzali, Reynolds, Blomster Lyshol, Verrelli and Falomir-Pichastor2021).

Yet there is a limited understanding of what defines ISC interventions or how various types of ISC differ. Some reviews have explored the effects of intergroup social contact (Maunder and White, Reference Maunder and White2019) or effects of certain types of ISC (Ando et al., Reference Ando, Clement, Barley and Thornicroft2011; Janoušková et al., Reference Janoušková, Tušková, Weissová, Trančík, Pasz, Evans-Lacko and Winkler2017), but no systematic reviews defining and comparing ISC in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) have been published. A focus on LMICs is important because of the broader mental health research and evidence gap on contact-based intervention in such contexts, and because the large majority of the world's population live in LMICs (Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Mehta, Clement, Evans-Lacko, Doherty, Rose, Koschorke, Shidhaye, O'reilly and Henderson2016).

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to an increase in risk factors for mental health conditions and exacerbated barriers to support for people with pre-existing mental health needs (Moreno et al., Reference Moreno, Wykes, Galderisi, Nordentoft, Crossley, Jones, Cannon, Correll, Byrne and Carr2020). Effects of the pandemic on mental health are more prominent in LMICs given other local endemics, stigma and pre-existing difficulties in mental healthcare (De Sousa et al., Reference De Sousa, Mohandas and Javed2020). ISC can be useful to target mental health-related stigma under current circumstances where face-to-face contact is restricted and the mental health burden is rising (Vigo et al., Reference Vigo, Thornicroft and Gureje2020; Naslund and Deng, Reference Naslund and Deng2021).

The aims of this systematic review are to address the gap in research on ISC in LMICs by categorising, comparing and defining ISC interventions to reduce mental health-related stigma in LMICs.

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The protocol for the systematic review was registered on PROSPERO, ID CRD42021248559. This review included studies with interventions containing an element of ISC aimed to reduce any type of mental health-related stigma or discrimination against people with mental health needs. Studies that focused on other stigmatised conditions such as HIV, substance use disorders and neurological conditions were excluded. ISC of any kind – including for example videos, presentations, personal narratives, photo-voice and theatrical performances – were eligible for inclusion. Comparators such as a non-exposed control group or a control group exposed to another type of stigma-reducing intervention were included as long as the effect of ISC specifically or its effect alongside one other stigma-reducing intervention could be analysed. Studies that did not have a comparator or control group were included as long as outcome measures were taken pre- and post-intervention. In this review, studies were considered to assess stigma if they explicitly stated they assessed stigma, or also if they captured stigma via the constructs of knowledge, attitudes and/or behaviour. Studies of all experimental designs were eligible for this review as long as at least one mental health-related stigma measure was collected pre and post intervention. Studies eligible for this review must have been conducted in a country classified as LMIC by the World Bank classification of gross national income (2019). Studies of any duration, size or follow-up were included. No restrictions were applied on target populations and publishing date. Searches were restricted to English language, and to human subjects.

Search strategy

The search strategy development was guided by other systematic reviews on stigma (Mehta et al., Reference Mehta, Clement, Marcus, Stona, Bezborodovs, Evans-Lacko, Palacios, Docherty, Barley and Rose2015; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Reavley, Ross, San Too and Jorm2018; Clay et al., Reference Clay, Eaton, Gronholm, Semrau and Votruba2020; Heim et al., Reference Heim, Kohrt, Koschorke, Milenova and Thornicroft2020). Five categories of terms (‘stigma’, ‘intervention’, ‘indirect social contact’, ‘mental health’ and ‘low- and middle-income countries’) were expanded with related subject headings and key words, connected with ‘OR’ within categories and ‘AND’ between categories. The full search strategy for databases used is provided within online Supplementary materials.

Records from MEDLINE, Global Health, EMBASE, PsychINFO, The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) were retrieved on 29 June 2021. In our review protocol we indicated that we could also conduct the search in Scopus; however, due to issues with feasibility and system errors at the time of the searches, Scopus was not used.

In addition to the database search, we performed backward and forward citation checking of included papers and checked reference lists of related systematic reviews (can be accessed in online Supplementary materials). Authors of included studies and other content experts were contacted for paper recommendations.

Study selection

All titles and abstracts were screened for potential relevance by the lead author, and 17% titles and abstracts were independently screened by the second reviewer to establish consistency. Reviewers resolved any disagreements through discussions, and a third person (GT or PCG) was involved as arbitrator when needed. Full-text versions of studies deemed potentially relevant were retrieved and screened against inclusion criteria. The second reviewer independently screened 13% full-text papers. Authors were contacted when full-texts were not available. If authors did not reply, the paper was excluded.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Hong et al., Reference Hong, Fàbregues, Bartlett, Boardman, Cargo, Dagenais, Gagnon, Griffiths, Nicolau and O'cathain2018). MMAT has two overall screening criteria and five criteria for each study design. One point was awarded for meeting the criteria indicators for each design-specific scoring domain. If papers mentioned some but not all of the criteria indicators 0.5 points were awarded (Gronholm et al., Reference Gronholm, Thornicroft, Laurens and Evans-Lacko2017). The MMAT score was used to determine the quality level of each paper, adapting the approach by Clay et al. (Reference Clay, Eaton, Gronholm, Semrau and Votruba2020). Included studies were assessed for quality by the lead author, 33% of those were assessed by another reviewer to assess for consistency. Studies were not excluded based on methodological quality.

Data extraction and analysis

A worksheet was developed to extract data from included papers (see online Supplementary materials). The classification of stigma by Pescosolido and Martin (Reference Pescosolido and Martin2015) was used for study characteristics. It included courtesy, public, provider-based, structural and self-stigma. Missing data or elaboration on the interventions was requested from original authors.

Ineffective interventions were described alongside effective interventions for the study characteristics section of results; however, studies that did not report an effect on the outcomes were considered separately for the categorisation of ISC interventions. In the comparison of categories section, ineffective interventions were included in the synthesis to compare any differences between categories and effective and ineffective interventions.

The method of synthesising information on ISC interventions was based on thematic synthesis (Thomas and Harden, Reference Thomas and Harden2008). Literal descriptions of how the interventions were conducted and what the process entailed were extracted and coded line-by-line according to the upcoming meanings, content or themes. No pre-existing framework was used; thus, broad themes came from the descriptions provided. Due to the exploratory nature of this review, a general narrative synthesis was used to synthesise and describe the findings.

Results

Search results

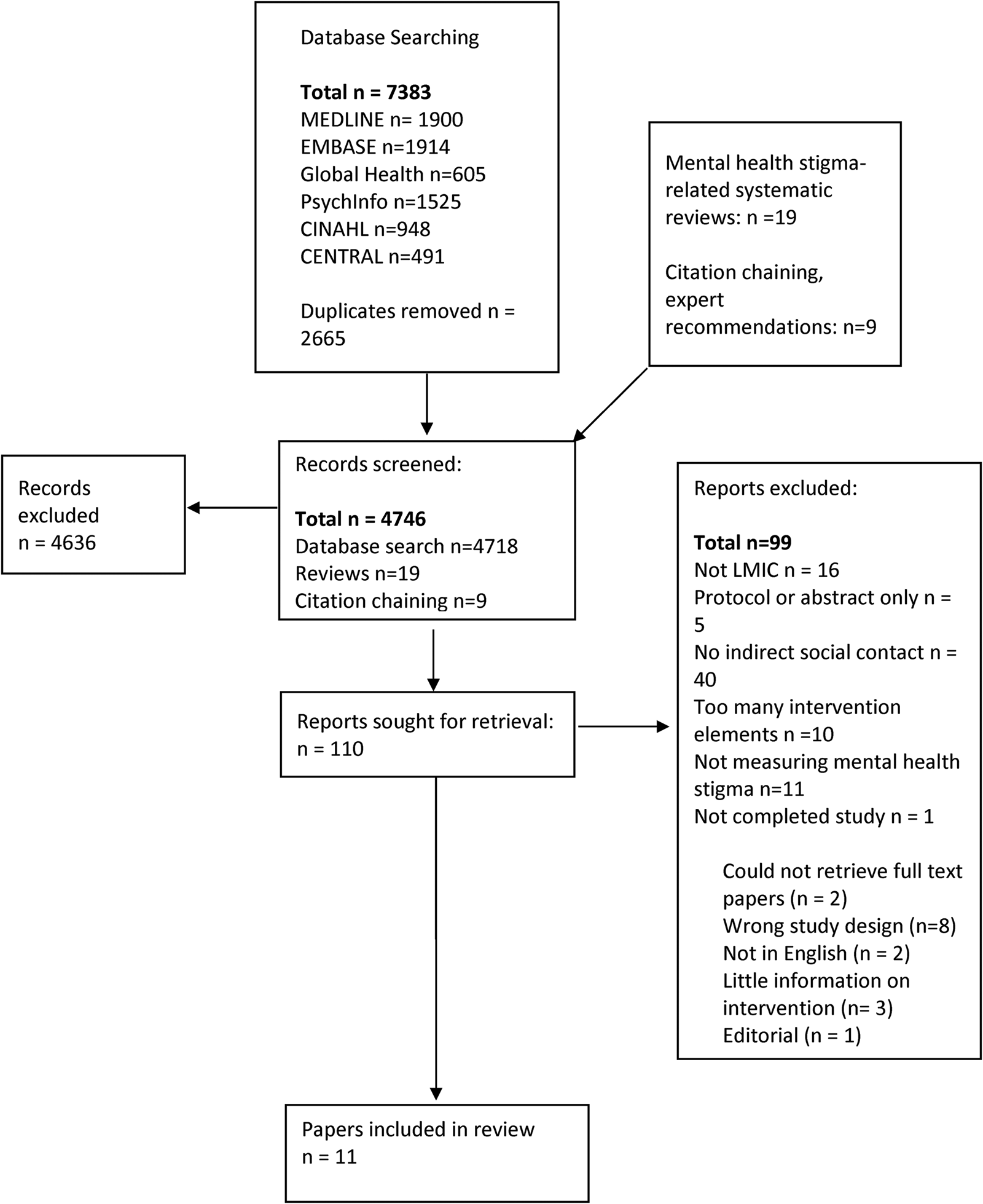

Of 7383 screened records, 11 papers (nine studies) were eligible for inclusion (Fig. 1). On two occasions, two papers referred to the same studies but with different follow-up points or different focus of outcome measures. These papers were considered jointly as reflective of one intervention study. Overall, 3630 participants were recruited through nine studies including healthcare workers, community leaders, families and members of the general population.

Fig. 1. PRISMA flow diagram of selection of papers.

Study characteristics

The main characteristics of the included studies are reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Key characteristics of included studies

RCT, randomised controlled trial; HCW, healthcare worker; GP, general population; CL, community leaders; V, video; PSV, problem-solving vignette; CAP, computer-assisted programme; PWLE, people with lived experience; C, contact; E, education; PRCT, pilot randomised controlled trial.

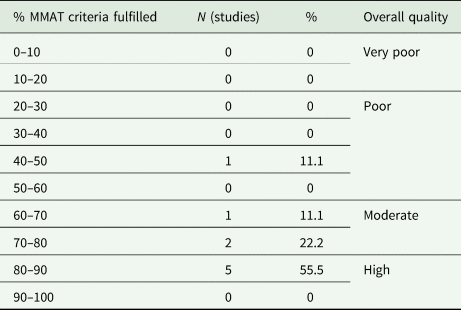

The quality of studies measured using MMAT varied (Table 2), with five high-quality papers fulfilling 80–90% of criteria, three moderate-quality papers fulfilling 60–80% of criteria and one of low quality fulfilling 40–50% of criteria.

Table 2. Summary of the study quality evaluated with MMAT

Five studies (55.6%) had a significant effect on all stigma-related outcomes, four had mixed results with small or medium effects and one randomised controlled trial (RCT) reported alongside a pilot RCT showed no significant effect. Studies included self-reported measures related to stigma that mainly included knowledge, attitudes or behaviour as proxy measures to evaluate changes in mental health-related stigma. These proxy measures were in accordance to the conceptualisation of stigma as issues of knowledge, attitudes and behaviour (Corrigan et al., Reference Corrigan, Morris, Michaels, Rafacz and Rüsch2012; Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Mehta, Clement, Evans-Lacko, Doherty, Rose, Koschorke, Shidhaye, O'reilly and Henderson2016).

ISC intervention categorisation

Medium of delivery and points of ISC

All but one intervention (n = 8) used video-based media on its own or as one of the points of ISC. Videos varied greatly in their duration, ranging from 3 to 40 min. The majority of interventions (n = 5) showed the videos only at one point.

Three studies used multiple channels to deliver ISC. The Time to Change Global campaign in Kenya and Ghana (Potts and Henderson, Reference Potts and Henderson2021) used multiple types of ISC by using social media for videos and radio to broadcast interviews with local mental health champions. A campaign in India (Maulik et al., Reference Maulik, Devarapalli, Kallakuri, Tewari, Chilappagari, Koschorke and Thornicroft2017, Reference Maulik, Devarapalli, Kallakuri, Tripathi, Koschorke and Thornicroft2019) engaged the public with ISC through posters and local theatre play about people with mental health needs. A study in Ghana (Arthur et al., Reference Arthur, Boardman, Morgan and Mccann2020a, Reference Arthur, Boardman, Morgan and Mccann2020b) used video-based contact and a problem-solving exercise about a person with mental health needs where participants had to come up with a solution for recovery.

The only intervention that did not include videos as its method of ISC was conducted in Russia (Finkelstein et al., Reference Finkelstein, Lapshin and Wasserman2008) with special education university students. This RCT looked at the effectiveness of the computer-assisted education system that had education and contact strategies. Contact was in the form of stories that would appear in the computer-assisted education system with follow-up questions.

Content and main themes

Only broad themes could be extracted from the information in the papers. Two studies (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Rashid and O'brien2017; Potts and Henderson, Reference Potts and Henderson2021) provided working links where videos could be accessed.

Seven interventions (Finkelstein et al., Reference Finkelstein, Lapshin and Wasserman2008; Vaghee et al., Reference Vaghee, Salarhaji and Vaghei2015; Fernandez et al., Reference Fernandez, Tan, Knaak, Chew and Ghazali2016; Maulik et al., Reference Maulik, Devarapalli, Kallakuri, Tewari, Chilappagari, Koschorke and Thornicroft2017, Reference Maulik, Devarapalli, Kallakuri, Tripathi, Koschorke and Thornicroft2019; Ng et al., Reference Ng, Rashid and O'brien2017; Arthur et al., Reference Arthur, Boardman, Morgan and Mccann2020b; Potts and Henderson, Reference Potts and Henderson2021) mentioned that during the videos or stories, person with lived experience described their personal experience of mental health needs. These experiences covered either mental health journeys, experiences with stigma or both. Information about caregiver videos mentioned personal experiences and reactions to the news about their family member having mental health problems, but further descriptions of the content were very limited.

Another commonly occurring theme was the use of a recovery story and seeking treatment (Finkelstein et al., Reference Finkelstein, Lapshin and Wasserman2008; Vaghee et al., Reference Vaghee, Salarhaji and Vaghei2015; Fernandez et al., Reference Fernandez, Tan, Knaak, Chew and Ghazali2016; Ng et al., Reference Ng, Rashid and O'brien2017; Arthur et al., Reference Arthur, Boardman, Morgan and Mccann2020a, Reference Arthur, Boardman, Morgan and Mccann2020b; Potts and Henderson, Reference Potts and Henderson2021; Tergesen et al., Reference Tergesen, Gurung, Dhungana, Risal, Basel, Tamrakar, Amatya, Park and Kohrt2021). Recovery was highlighted by people with lived experience, people in contact with them (caregivers or co-workers) or through a problem-solving exercise based on a vignette story. Treatment themes broadly covered the treatment options, the process and results of treatment or encouragement to seek treatment.

The study from Russia (Finkelstein et al., Reference Finkelstein, Lapshin and Wasserman2008) had a different approach of providing a personal story and recovery of a real-life person along historical facts and stories about negative treatment of people with mental health needs.

Another prominent theme on intervention effects was the presence of an emotional or empathetic response. The majority of effective or partly effective studies (Finkelstein et al., Reference Finkelstein, Lapshin and Wasserman2008; Vaghee et al., Reference Vaghee, Salarhaji and Vaghei2015; Maulik et al., Reference Maulik, Devarapalli, Kallakuri, Tewari, Chilappagari, Koschorke and Thornicroft2017, Reference Maulik, Devarapalli, Kallakuri, Tripathi, Koschorke and Thornicroft2019; Arthur et al., Reference Arthur, Boardman, Morgan and Mccann2020a, Reference Arthur, Boardman, Morgan and Mccann2020b; Potts and Henderson, Reference Potts and Henderson2021) mentioned that participants reported an emotional response towards the person with lived experience, or that the intervention aimed to elicit emotions from participants through ISC. The intervention conducted in Iran for families of service users (Vaghee et al., Reference Vaghee, Salarhaji and Vaghei2015) resulted in a discussion after the caregiver video during which people connected to experiences emotionally. In a study conducted in Russia (Finkelstein et al., Reference Finkelstein, Lapshin and Wasserman2008) qualitative data from students indicated that stories were an important part of the intervention. Qualitative results of a campaign in India (Maulik et al., Reference Maulik, Devarapalli, Kallakuri, Tewari, Chilappagari, Koschorke and Thornicroft2017) revealed that people felt that they could relate and better understand the challenges faced by service users through theatrical performance and videos.

Combinations of interventions

The majority of studies (n = 7) used psychoeducation and ISC strategies to reduce stigma. The types of psychoeducation alongside ISC included delivery mediums such as presentations (Arthur et al., Reference Arthur, Boardman, Morgan and Mccann2020a, Reference Arthur, Boardman, Morgan and Mccann2020b), lectures (Fernandez et al., Reference Fernandez, Tan, Knaak, Chew and Ghazali2016), videos (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Rashid and O'brien2017; Gürbüz et al., Reference Gürbüz, Yorulmaz and Durna2020), educational messages (Finkelstein et al., Reference Finkelstein, Lapshin and Wasserman2008), social media advertisements (Potts and Henderson, Reference Potts and Henderson2021) and printed materials such as posters and pamphlets (Maulik et al., Reference Maulik, Devarapalli, Kallakuri, Tewari, Chilappagari, Koschorke and Thornicroft2017, Reference Maulik, Devarapalli, Kallakuri, Tripathi, Koschorke and Thornicroft2019). One intervention compared the difference between direct social contact and education v. ISC (video) and education (Fernandez et al., Reference Fernandez, Tan, Knaak, Chew and Ghazali2016). Only one study in Iran used ISC intervention without combining it with another stigma-reducing strategy; this study compared ISC-only (video) and non-ISC interventions (psychoeducation and control) (Vaghee et al., Reference Vaghee, Salarhaji and Vaghei2015).

Delivery agent and interaction

In terms of delivery agents, the majority of interventions had people with lived experience as a delivery agent (Fernandez et al., Reference Fernandez, Tan, Knaak, Chew and Ghazali2016; Maulik et al., Reference Maulik, Devarapalli, Kallakuri, Tewari, Chilappagari, Koschorke and Thornicroft2017, Reference Maulik, Devarapalli, Kallakuri, Tripathi, Koschorke and Thornicroft2019; Ng et al., Reference Ng, Rashid and O'brien2017; Gürbüz et al., Reference Gürbüz, Yorulmaz and Durna2020; Arthur et al., Reference Arthur, Boardman, Morgan and Mccann2020a, Reference Arthur, Boardman, Morgan and Mccann2020b; Potts and Henderson, Reference Potts and Henderson2021). One intervention (Vaghee et al., Reference Vaghee, Salarhaji and Vaghei2015) targeting families of patients with schizophrenia had only a caregiver as a delivery agent. Some interventions included people with lived experience and other key stakeholders as delivery agents; namely family members or caregivers (Fernandez et al., Reference Fernandez, Tan, Knaak, Chew and Ghazali2016; Maulik et al., Reference Maulik, Devarapalli, Kallakuri, Tewari, Chilappagari, Koschorke and Thornicroft2017, Reference Maulik, Devarapalli, Kallakuri, Tripathi, Koschorke and Thornicroft2019; Gürbüz et al., Reference Gürbüz, Yorulmaz and Durna2020; Arthur et al., Reference Arthur, Boardman, Morgan and Mccann2020a, Reference Arthur, Boardman, Morgan and Mccann2020b), healthcare workers (Fernandez et al., Reference Fernandez, Tan, Knaak, Chew and Ghazali2016; Ng et al., Reference Ng, Rashid and O'brien2017) and celebrities known to have a mental health disorder, and a lay person talking about her co-worker with mental healthcare needs (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Rashid and O'brien2017). Two interventions did not have a delivery agent at all or in one of the components of indirect contact (Finkelstein et al., Reference Finkelstein, Lapshin and Wasserman2008; Arthur et al., Reference Arthur, Boardman, Morgan and Mccann2020a, Reference Arthur, Boardman, Morgan and Mccann2020b) as the ISC was presented as a story in a computer program or as a vignette with a problem-solving exercise.

Another characteristic of ISC interventions in LMICs related to active and passive interaction with content. Active engagement entailed discussions in groups after watching videos (Vaghee et al., Reference Vaghee, Salarhaji and Vaghei2015), problem-solving exercises based on a vignette (Arthur et al., Reference Arthur, Boardman, Morgan and Mccann2020a, Reference Arthur, Boardman, Morgan and Mccann2020b) or responding to questions (Finkelstein et al., Reference Finkelstein, Lapshin and Wasserman2008). Passive contact occurred when participants would watch a video or listen to a radio programme without subsequently actively engaging with one's attitudes or knowledge either through interactive exercises or group discussions (Fernandez et al., Reference Fernandez, Tan, Knaak, Chew and Ghazali2016; Ng et al., Reference Ng, Rashid and O'brien2017; Gürbüz et al., Reference Gürbüz, Yorulmaz and Durna2020; Potts and Henderson, Reference Potts and Henderson2021).

Comparison and effectiveness of interventions with ISC

Content and main themes

The studies explicitly mentioning the cultural relevance of interventions showed that their positive results were sustained after a month (Vaghee et al., Reference Vaghee, Salarhaji and Vaghei2015), and even after 2 years (Maulik et al., Reference Maulik, Devarapalli, Kallakuri, Tripathi, Koschorke and Thornicroft2019). Other effective interventions also had videos that either matched the local language, or that included local people with lived experience in the videos (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Rashid and O'brien2017; Potts and Henderson, Reference Potts and Henderson2021).

The study in Ghana looking at depression and schizophrenia (Arthur et al., Reference Arthur, Boardman, Morgan and Mccann2020a, Reference Arthur, Boardman, Morgan and Mccann2020b) produced no significant changes in knowledge related to depression, and only some subscales (attitudes, beliefs) had significant differences at follow-up (Arthur et al., Reference Arthur, Boardman, Morgan and Mccann2020b). Notably, the ineffective study (Tergesen et al., Reference Tergesen, Gurung, Dhungana, Risal, Basel, Tamrakar, Amatya, Park and Kohrt2021) also targeted two conditions (depression and psychosis). Authors theorised that different stigma reduction strategies should be developed for different types of mental illnesses, or that more severe mental illnesses should not be paired in interventions with other mental health needs.

Intervention strategy comparison

There was a limited number of interventions that used only ISC. From those that did one found no significant results (Tergesen et al., Reference Tergesen, Gurung, Dhungana, Risal, Basel, Tamrakar, Amatya, Park and Kohrt2021) and another (Vaghee et al., Reference Vaghee, Salarhaji and Vaghei2015) found significant changes in comparison to the control group for all subscales of Internalised Stigma of Mental Illness Scale (Ritsher et al., Reference Ritsher, Otilingam and Grajales2003). However, when compared to the psychoeducation group, significant changes were only detected for scores on the ‘social withdrawal’ and ‘discrimination experience’ subscales of the Internalised Stigma of Mental Illness Scale. Among the studies that used two strategies of education and contact (n = 7), four had significant effect on all the subscales of the stigma-related outcomes they used (Finkelstein et al., Reference Finkelstein, Lapshin and Wasserman2008; Fernandez et al., Reference Fernandez, Tan, Knaak, Chew and Ghazali2016; Ng et al., Reference Ng, Rashid and O'brien2017; Gürbüz et al., Reference Gürbüz, Yorulmaz and Durna2020), and the rest had mixed results (Maulik et al., Reference Maulik, Devarapalli, Kallakuri, Tewari, Chilappagari, Koschorke and Thornicroft2017; Arthur et al., Reference Arthur, Boardman, Morgan and Mccann2020a, Reference Arthur, Boardman, Morgan and Mccann2020b; Potts and Henderson, Reference Potts and Henderson2021).

As for the only ineffective study (Tergesen et al., Reference Tergesen, Gurung, Dhungana, Risal, Basel, Tamrakar, Amatya, Park and Kohrt2021), no improvements were observed for implicit or explicit attitudes or diagnostic accuracy among medical students between the service user video (where service users with depression or schizophrenia shared their personal experience and recovery story) and a didactic video (healthcare provider talking about the treatment process).

Active and passive interaction

When it comes to the effectiveness of active and passive interaction, of four studies with active engagement two had a significant effect on most scores of knowledge, attitudes and behaviour at a 2-year follow-up (Maulik et al., Reference Maulik, Devarapalli, Kallakuri, Tewari, Chilappagari, Koschorke and Thornicroft2017, Reference Maulik, Devarapalli, Kallakuri, Tripathi, Koschorke and Thornicroft2019), and one had significant effects on stigma and knowledge scores after 6 months (Finkelstein et al., Reference Finkelstein, Lapshin and Wasserman2008). Two other studies showed partial improvement in attitudes (Arthur et al., Reference Arthur, Boardman, Morgan and Mccann2020b), discrimination and social withdrawal (Vaghee et al., Reference Vaghee, Salarhaji and Vaghei2015).

Regarding studies with passive interaction with ISC, two produced significant positive effects on attitudes (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Rashid and O'brien2017), social distance and help-seeking (Fernandez et al., Reference Fernandez, Tan, Knaak, Chew and Ghazali2016). Partial effectiveness was shown for knowledge or attitudes only (Potts and Henderson, Reference Potts and Henderson2021). The ineffective study (Tergesen et al., Reference Tergesen, Gurung, Dhungana, Risal, Basel, Tamrakar, Amatya, Park and Kohrt2021) also involved passive interaction with service user videos.

Discussion

This review aimed to categorise, compare and define ISC interventions to reduce mental health-related stigma in LMICs. Most included studies of ISC interventions were shown to be effective in reducing stigma either on all measures or certain subscales of measures. Currently limited evidence exists on interventions using only ISC to reduce stigma (Vaghee et al., Reference Vaghee, Salarhaji and Vaghei2015; Tergesen et al., Reference Tergesen, Gurung, Dhungana, Risal, Basel, Tamrakar, Amatya, Park and Kohrt2021); more often ISC is paired with educational strategies (Finkelstein et al., Reference Finkelstein, Lapshin and Wasserman2008; Fernandez et al., Reference Fernandez, Tan, Knaak, Chew and Ghazali2016; Maulik et al., Reference Maulik, Devarapalli, Kallakuri, Tewari, Chilappagari, Koschorke and Thornicroft2017, Reference Maulik, Devarapalli, Kallakuri, Tripathi, Koschorke and Thornicroft2019; Ng et al., Reference Ng, Rashid and O'brien2017; Arthur et al., Reference Arthur, Boardman, Morgan and Mccann2020a, Reference Arthur, Boardman, Morgan and Mccann2020b; Potts and Henderson, Reference Potts and Henderson2021). Existing evidence of higher effectiveness of combining education and contact strategies (Rüsch et al., Reference Rüsch, Angermeyer and Corrigan2005; Patten et al., Reference Patten, Remillard, Phillips, Modgill, Szeto, Kassam and Gardner2012) was the rationale behind combining ISC with education. The included studies were all relatively recent, indicating a growing interest in this area. This review provides an important contribution through synthesising what is known to date about ISC interventions to reduce mental health-related stigma.

The most popular medium of ISC was videos, and indeed, previous reviews have shown that video-based contact can be effective in reducing stigma (Janoušková et al., Reference Janoušková, Tušková, Weissová, Trančík, Pasz, Evans-Lacko and Winkler2017). Interestingly, there was only one intervention (Maulik et al., Reference Maulik, Devarapalli, Kallakuri, Tewari, Chilappagari, Koschorke and Thornicroft2017, Reference Maulik, Devarapalli, Kallakuri, Tripathi, Koschorke and Thornicroft2019) that used a creative outlet such as theatrical performance. Examples of using creative means of ISC from high-income countries (Michalak et al., Reference Michalak, Livingston, Maxwell, Hole, Hawke and Parikh2014; Kosyluk et al., Reference Kosyluk, Marshall, Conner, Macias, Macias, Michelle Beekman and Her2021) show significant changes in stigma which potentially indicates that such an approach can also be effective in LMICs.

As for the active and passive engagement with ISC, active interaction might contribute to more favourable results, and qualitative data found ISC (Maulik et al., Reference Maulik, Devarapalli, Kallakuri, Tewari, Chilappagari, Koschorke and Thornicroft2017) being received as the most effective component of the intervention. However, it is difficult to judge as passive and active interactions produced both significant and mixed results.

Content and culture

Some interventions provided limited details about the content of the ISC intervention (Finkelstein et al., Reference Finkelstein, Lapshin and Wasserman2008). This poses problems for future replicability and development of interventions. The content of ISC interventions is comparable with the content of direct contact interventions, where some of the strategies might include people sharing personal experiences, recovery stories or caregiver experience (Clement et al., Reference Clement, Van Nieuwenhuizen, Kassam, Flach, Lazarus, De Castro, Mccrone, Norman and Thornicroft2012; Gonçalves et al., Reference Gonçalves, Moleiro and Cook2015). Sharing personal and recovery stories and experiences seems to be an important critical active ingredient for ISC in LMICs, as one or both of these themes have occurred in all interventions.

Cultural adaptation is likely to be important to produce effective and appropriate interventions for local communities. Given countries and cultures have differing sources of information that are considered appropriate or reliable (Semrau et al., Reference Semrau, Evans-Lacko, Koschorke, Ashenafi and Thornicroft2015), it is crucial for interventions to adapt how and through whom stigma-reducing messages are translated. For instance, video contact by a peer caregiver in Iran (Vaghee et al., Reference Vaghee, Salarhaji and Vaghei2015) helped to create an environment where other families could safely share their experiences. Authors specified that differences between the individualistic, Western, and collectivist, Eastern, cultures were important considerations, and there was a need to arrange a safe environment for families to discuss and self-expose beliefs and experiences. Another example from the study conducted in India by Maulik et al. (Reference Maulik, Devarapalli, Kallakuri, Tewari, Chilappagari, Koschorke and Thornicroft2017) who purposefully developed a culturally relevant intervention stated that ‘Many participants mentioned that the drama and videos made them realize that they should not desert or abuse persons suffering from psychological problem, rather provide support to them.’ This further emphasises the importance and role of intervention's relevance and acceptability to the local culture.

Defining ISC interventions in LMICs

After analysing the descriptions in the included papers, the following broad themes related to ISC interventions appeared: content, delivery agent, emotional response and effect on participants, cultural relevance or adaptation, interaction, delivery medium and effect on stigma. Given these broad themes we propose the following new definition of ISC in LMICs.

Indirect social contact entails a culturally/locally relevant active or passive interaction with real-life (or based on real-life) stories, narratives, or experiences of people with lived experience or those in contact or close to them (family or practitioners); and, uses online, technological, printed or other forms of traditional or new media for conveying information that elicits positive emotional or empathic responses.

Strengths and limitations of the review

This is the first systematic review examining ISC in LMICs, providing a categorisation of these studies and a novel definition of ICS interventions in LMICs. This is in contrast to previous reviews that have focused on subtypes of ISC (Ando et al., Reference Ando, Clement, Barley and Thornicroft2011; Clement et al., Reference Clement, Lassman, Barley, Evans-Lacko, Williams, Yamaguchi, Slade, Rüsch and Thornicroft2013; Janoušková et al., Reference Janoušková, Tušková, Weissová, Trančík, Pasz, Evans-Lacko and Winkler2017) and included studies from both HICs and LMICs, or considered different types of contact intervention strategies together (Clay et al., Reference Clay, Eaton, Gronholm, Semrau and Votruba2020; Hartog et al., Reference Hartog, Hubbard, Krouwer, Thornicroft, Kohrt and Jordans2020; Kaur et al., Reference Kaur, Kallakuri, Kohrt, Heim, Gronholm, Thornicroft and Maulik2020).

This work does, however, need to be considered in view of some limitations. The included studies varied greatly in the level of detail of intervention descriptions, which could lead to results being more reliant on some papers than others for categorisation and definition. However, to mitigate such impacts authors were contacted for added details and all relevant information was extracted to capture main ideas and themes about ISC of each included study. Also, as is common in much stigma research, nearly all effectiveness measures were self-reported which may increase social desirability bias, and not all studies reported if the measures were validated in the local context.

Implications and recommendations

A broader array of mediums and types of ISC interventions are seen in HICs compared to LMICs (Clement et al., Reference Clement, Lassman, Barley, Evans-Lacko, Williams, Yamaguchi, Slade, Rüsch and Thornicroft2013; Mehta et al., Reference Mehta, Clement, Marcus, Stona, Bezborodovs, Evans-Lacko, Palacios, Docherty, Barley and Rose2015; Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Mehta, Clement, Evans-Lacko, Doherty, Rose, Koschorke, Shidhaye, O'reilly and Henderson2016; Janoušková et al., Reference Janoušková, Tušková, Weissová, Trančík, Pasz, Evans-Lacko and Winkler2017; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Reavley, Ross, San Too and Jorm2018; Rao et al., Reference Rao, Elshafei, Nguyen, Hatzenbuehler, Frey and Go2019). More studies are needed to explore if these might be appropriate in LMICs while addressing culture and local relevance. Given many difficulties of providing in-person contact it is important to continue investigating the effectiveness of ISC interventions on their own or together with other stigma-reducing strategies.

When reporting on ICS interventions, more details need to be provided on intervention components and content to facilitate further refinement of the ICS definition and categories in LMICs. Such insights will support the development of more effective ICS interventions.

More research evidence is needed from different regions, particularly low-income countries, as the current evidence-base is dominated by a small number of countries. Studies examining the long-term effectiveness of ICS interventions are also lacking.

Conclusions

Based on current evidence from LMICs ISC can be categorised by content, combination of strategies, medium of delivery, delivery agent, condition and active/passive interaction. The most common way of delivering ISC was through video, but alternative ISC strategies were also effective. All interventions included recovery or personal experience, which seems to be an important part of ISC in LMICs.

ISC, specifically when paired with education strategies, is an effective approach for reducing mental health-related stigma in LMICs among the general population, healthcare workers and community leaders. At the moment, interventions with only ISC showed mixed or no significant changes in stigma. Active and passive interaction of participants with ISC needs to be explored further to reach more conclusive evidence. Thus, there is currently no conclusive evidence regarding the association between ICS intervention duration and effectiveness.

Our proposed definition of ISC can be refined further through consistency and clarity of future research.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796022000622.

Data

For access to data supporting this study, please email Akerke Makhmud: akerke.1.makhmud@kcl.ac.uk or akerkemakhmud@gmail.com.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jun Angelo Sunglao and Dr Sara Zarti for their support when screening the papers and quality reviewing papers.

Financial support

G. T. is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration South London at King's College London NHS Foundation Trust, by the NIHR Asset Global Health Unit award and the NIHR Hope Global Health Group award. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. G. T. is also supported by the Guy's and St Thomas' Charity for the On Trac project (EFT151101), and by the UK Medical Research Council (UKRI) in relation to the Emilia (MR/S001255/1) and Indigo Partnership (MR/R023697/1) awards. P. C. G. is supported by the UK Medical Research Council (UKRI) in relation to the Indigo Partnership (MR/R023697/1) award.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

Ethics approval was not required for this systematic review.