In his work on twentieth-century Berlin, Andreas Huyssen ponders how places – particularly urban places – experience and remember trauma. Huyssen analyses the city as palimpsest, one whose ruins mark ‘absences’ just as much as the visible presence of past violence is preserved by bullet and shrapnel marks on buildings. Berlin is both ‘saturated with memory’ and marked by ‘willful forgetting’, a dichotomy which seems just as pertinent to Paris a century before.Footnote 1 In the 1870s and 1880s, Paris was marked by the visible ruins of the Commune, most famously the gutted Tuileries palace, which remained at the centre of the city for 12 years (Fig. 1). Dr Thomas Evans, an American dentist, wrote of the palace:

For many long years one huge pile of blackened ruins, the remains of what was once the Palace of the Tuileries, loomed up in the very centre of the city, solemn, grand, and mysterious, like a funereal monument, to remind the world of the uncertain life of governments – in France. It was only in 1883 that, becoming apparently ashamed of this startling exhibition of the savagery of the mob, of this vestige of the reign of the Commune in the Ville Lumière, the Government ordered the demolition of these ruins, and covered with fresh turf and flowers the ground on which had stood the home of the most famous kings of France. Every trace of the palace has been removed, effaced, or carefully covered up. And here it is, in this new and formal garden, that to-day children with their nurses gather together in hushed silence.Footnote 2

If the visual reminders of violence and trauma leave ‘absent presences’ in the heart of an urban space, how might the memories of the sounds of conflict be similarly understood as leaving traces – sonic scars – in individual and collective memories? In this article, I consider how the inhabitants of Paris experienced sound as trauma during the war year of 1870–71, and how that sonic trauma was processed, remembered and memorialized.

Fig. 1 Tuileries Palace (Main Hall, Garden Side), Photograph by Auguste Bruno Braquehais, Thereza Christina Maria Collection, Biblioteca Nacional do Brasil

As discussed in this issue's introduction, trauma has emerged (largely in the last 40 years) as a powerfully interdisciplinary subject of cultural, psychiatric and medical study marked by pivotal events – including the inclusion of the term ‘posttraumatic stress disorder’ in the DSM-III issued by the American Psychiatric Association in 1980 – and groundbreaking publications such as Judith Herman's Trauma and Recovery (1992), Dominick LaCapra's Writing History, Writing Trauma (2001) and Jeffrey Alexander and others on cultural trauma (2004).Footnote 3 Indeed, the concept of trauma has been shaped over the past 75 years by many of the catastrophic events of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries – the Holocaust in particular, but also the Vietnam War, 9/11, and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, just to note a few. As illustrated by this special issue, several conference panels in the last few years and a number of recent or forthcoming publications, trauma's broader implications are the subject of much current discussion and analysis.

Studying trauma in the late nineteenth century presents a different set of historiographical problems, however. In an analysis of the ‘practices, technologies, and narratives with which it [trauma] is diagnosed, studied, treated, and represented’, Allan Young has argued that trauma is not a timeless, universal phenomena. Rather, it is essential to analyse trauma through a constructivist, temporally appropriate manner.Footnote 4 Assessing how traumatic events of 1870–71 were contextualized in contemporary discourse is difficult – we cannot uncritically transplant terminology and concepts we use today to all periods of the past. Yet the late nineteenth century, including events in France in 1870–71, is a particularly fruitful period for a historical study of trauma. In his work, Young focuses not precisely on the emotions of fear or suffering or loss, but on the ways these experiences impacted memory. He argues that a new type of ‘painful’ memory emerged at the end of the nineteenth century: ‘it was unlike the memories of earlier times in that it originated in a previously unidentified psychological state, called “traumatic”, and was linked to previously unknown kinds of forgetting, called “repression” and “dissociation”’.Footnote 5 Mark Micale explicitly places the beginnings of the trauma concept in psychological medicine in the 1870s, noting that political events in tandem with social problems and emerging medicalized discourses helped forge the ‘proto-science of mental trauma’.Footnote 6

While it is unlikely that the events of 1870–71 were the single causative agent for this development, the formative debates and concepts about trauma emerged at precisely the moment Parisians experienced and processed the aftermath of a year of war, siege, bombardment, civil war and mass slaughter. Studying this year offers a specific nineteenth-century case study of how individuals understood, discussed and remembered these events at the dawn of the ‘trauma concept’. In assessing reactions by Parisians and period medical discourse, it is clear that there are many important continuities between this nineteenth-century conflict and la grande guerre (World War I) nearly 50 years later. My analysis, therefore, highlights some ways the emergence of trauma during 1870–71 presaged discourse from 1914–18. Foregrounding sound's role in the traumas of 1870–71, I demonstrate that these memories of wartime sounds not only marked the urban landscape of Paris for decades to come, but that the sounds of war also marked the minds and bodies of Parisians themselves. Ultimately, I argue sound is a critical element in assessing historical understandings of trauma.

Hearing Nineteenth-Century Paris

As part of the ‘sensual turn’ in the humanities more broadly, as well as the ‘sonic turn’ in music studies, Mark M. Smith, Jennifer Stoever and other authors have analysed how the understanding and experience of sound is raced, gendered and classed.Footnote 7 Scholars such as Maria Cizmic, Joshua Pilzer, Amy Lynn Wlodarski and J. Martin Daughtry have published foundational work considering sound's and music's connections with trauma, largely focused on the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.Footnote 8 But studying sounds of the more distant past – particularly in the era before sound recordings – is fraught with difficulties, as we struggle to find traces of ‘vanished’ sounds in the remaining historical evidence. Despite these obstacles, certain sonic vestiges abound in nineteenth-century sources. Building on Lisa Gitelman's concept of the ‘inscription’ of sound into writing, Ana María Ochoa Gautier's work on aurality in Colombia beautifully details methodological approaches for nineteenth-century sound, including both an ‘acoustically tuned exploration of the written archive’ and historical sounds inscribed beyond the archive or the written text.Footnote 9 In his work on the history of the senses, Smith notes the primacy of sight in the nineteenth century, yet demonstrates how period visual culture often reveals tantalizing traces of the sonic – a particularly fruitful suggestion in the case of 1870–71, a year exhaustively chronicled throughout the world in lithographs, illustrated newspapers and photography.Footnote 10

Studying sound's relationship to trauma in 1870–71 also incorporates elements of both urban studies and the sounds of war. In her study of Parisian street cries during the nineteenth century, Aimée Boutin argues that Walter Benjamin's influential approach to the flâneur – an observant individual walking leisurely through urban streets – has perhaps overemphasized the role of visuality.Footnote 11 Drawing on contemporary sources such as Balzac and Victor Fournel, Boutin instead calls for a concept of ‘aural flânerie’, arguing that sounds and soundmarks were essential to understanding a city.Footnote 12 Indeed, Parisians meticulously listened to their city, particularly the changing sounds of nineteenth-century urban spaces. Throughout most of the Second Empire, Paris was in the midst of massive renovation projects: Baron Haussman overhauled much of medieval Paris in favour of new broad, expansive boulevards, forever changing the city's soundscape.Footnote 13 Boutin notes that these new Haussmanian boulevards – ‘as wide as their buildings were tall (18 meters)’ – echoed and resonated quite differently than the older narrow, resonant streets.Footnote 14 These changing urban sounds were understood in markedly oppositional ways; as Shelley Trower discusses, scholars had considered the potentially negative effects of vibrations on the human body since the mid-eighteenth century.Footnote 15 By the time of the Franco-Prussian War, many commentators worried how unregulated urban noise could affect the nerves. French hygienist Jean-Baptiste Fonssagrives, for example, argued that noise from omnibuses and other vehicles ‘caused windows and nerves to vibrate’, creating nervous problems in ‘susceptible’ individuals.Footnote 16 On the other hand, French medical professionals had investigated ways to utilize vibration as a therapeutic process since the Revolution, a focus that intensified throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. As Jillian Rogers notes in her work on World War I, it is often when sounds become traumatic (as in times of war) that there is a concomitant effort to harness the positive or soothing effects of sound.Footnote 17

Within its dense layers of soundmarks, Paris had a particularly rich relationship with the sounds of revolution. In 1789, 1830, 1848 and so on, the city echoed with the singing of century-old revolutionary songs, bells calling the populace to arms, the rappel or générale, bugle calls and the ringing of stone as Parisians constructed barricades.Footnote 18 These sounds were both a language and an inherited memory routinely revisited over a century or more, a sonic vocabulary of revolution written into the aural history of Paris.Footnote 19 Thus, certain events during 1870–71 had a sort of sonic familiarity, though other new, horrifying sounds disoriented Parisians. From the declaration of war on 19 July 1870, when Parisians flooded the streets singing, to the bloody final battles when detonations, shots and screams resounded street by street, Paris in 1870–71 was riven by what Daughtry has broadly termed ‘belliphonic’ sounds – sounds produced by armed combat.Footnote 20 Scholars have closely examined certain aspects of Parisian musical culture during this period, such as popular song and concert life.Footnote 21 What remains understudied is the broader sonic experience of battle, bombardment, siege and civil war within a nineteenth-century urban soundscape, a focus on what Martin Kaltenecker has noted as the ‘phonosphères of war’.Footnote 22 These sounds both marked the streets of the French capital with ‘aural ruins’ – memories or scars of the events of 1870–71 – and marked the minds and bodies of some Parisians with traumatic memories. Time constraints necessitate only a capsule review of the sonic experience of this pivotal year; while I mention a number of sonic episodes, my main focus is on two periods: the Prussian bombardment of Paris in January 1871 and the sounds of the Commune.

I. ‘Le trouble des esprits’: Parisian Sounds During l'année terrible

The Fall of Empire: Sounds and Psychological Impacts in Autumn 1870

What Victor Hugo deemed France's ‘terrible year’ (l'année terrible) began in July 1870 with the declaration of war with Prussia.Footnote 23 The climactic loss at Sedan came in early September, followed swiftly by the fall of France's Second Empire. Residents of the French capital were forced to rapidly assess their options as the Prussian army marched to encircle Paris. Most dug in their heels, preparing for siege or occupation by stockpiling provisions in cellars and burying or hiding valuables. In his memoir, French psychiatrist Dr Henri Legrand du Saulle, who worked at the Dépôt de la Préfecture de Police, noted that in these days of early September 1870, ‘disturbance of the spirits is at its highest point’.Footnote 24 People reacted in different ways, from fear to trembling, repetitive motions and speech, shouting, weeping or, conversely, silence. Some, wrote Legrand du Saulle, experienced true sensory illusions: ‘they think they hear hoofbeats of the cavalry scouts, the sinister chiming of the tocsin or the whistles of the enemy's front lines. Imagining that they are going to be captured and immediately attacked, they run to hide somewhere dark. At this moment, we observe some cases of sudden suicide’.Footnote 25

Throughout four months in autumn and winter 1870, the entire soundscape of Paris shifted. The Prussians encircled the city on 19 September 1870, initiating a devastating siege in hopes of forcing capitulation. Paris became unnaturally quiet, with distant sounds echoing through the stone streets. Théophile Gautier noted the ‘terrifying solitude’ of this ‘deathly silence’, adding that, ‘you would think you were in a medieval city, at the hour when curfew sounds’.Footnote 26 An anonymous published account added that ‘drilling, the rattle of the drum and the booming of distant cannon were the only sounds that disturbed the silence’.Footnote 27 In his journal, Edmond de Goncourt noted how the siege's horrors even interfered at times with his ability to mourn the recent death of his brother.Footnote 28 De Goncourt believed many French citizens struggled to process the autumn's events. On 4 October, he wrote, ‘opening the paper this morning, I read that Callou, the director at Vichy, has had a mental breakdown. He is only forty-two. This year there have been so many minds of forty worn out and done for by pressures of business, politics, literature.’Footnote 29

The winter of 1870–71 was especially cold; in frozen Paris, sounds echoed in unusual ways off the hard angles of cold stone and the icy river. De Goncourt reported:

In spite of the deadening effect of the snow which falls in dispersed, fluffy, crystalline flakes you can hear everywhere a distant and continuous cannonade from the direction of Saint Denis and Vincennes. In front of Montmartre cemetery the hearses are lined up, their horses breathing noisily, the coachmen in black silhouette against the white snow as they stamp their feet.Footnote 30

With the combined effects of the siege's starvation, a smallpox epidemic and the freezing weather, Paris's death toll skyrocketed. English newspaper correspondent Felix Whitehurst wrote on Christmas Day of ‘hospitals crowded with the dying; heaps of dead on our surrounding heights; hardly a family which is not in mourning, and even in grief, which quite another thing; starvation staring us in the face; fuel burnt out; meat a recollection, and vegetables a pleasing dream’.Footnote 31 De Goncourt believed that not all of these Parisian deaths were the result of physical privations, but from the interaction of the body and the mind, noting that ‘much of this mortality comes from grief, displacement, homesickness’.Footnote 32

Sickness and Shelling: The Bombardment of January 1871

At the beginning of 1871, the Prussians installed artillery pieces – including new steel ‘Krupp’ guns – in forts around Paris. At 3am on 5 January they commenced shelling the city, with fire concentrated on the commune of Montrouge and the 5th and 14th arrondissements, including the Barrière d'Enfer, the Faubourg Saint-Jacques, the Observatoire and the Panthéon.Footnote 33 Between 300 and 600 shells hit central Paris each day, with more than 12,000 shells fired into the city over a 23-day bombardment.Footnote 34 As a National Guard sentry patrolling Paris's fortifications, composer Vincent d'Indy listened intently to the shelling (indeed he claimed the Prussian guns were pitched in B-flat). In an 1872 memoir on his wartime experience, d'Indy devoted lengthy passages to the bombardment, detailing both the sounds he heard and the somatic response of French soldiers.Footnote 35 Narrating a timeline of wartime listening, d'Indy begins with an almost hour-by-hour account of the first days of the bombardment. On the evening of 6 January, he singled out the whistling of shells as especially frightening; hearing the sound almost felt like a sickness.Footnote 36 After several days of shelling in January, d'Indy noted his desensitization to many of the horrible sights and sounds of battle, except the horrible whistling of the shells. Despite hearing this sound thousands of times he ‘could not help but shiver’, and ‘feel a cold sweat run through the body upon hearing this terrible crescendo’. He hastened to add that this wasn't fear, but a ubiquitous bodily sensation felt even by veteran naval gunners.Footnote 37

The potential physical and psychological effects of shelling were not entirely new concerns in 1871. Since the Napoleonic wars, the phrase ‘le vent du boulet’ – literally, being ‘in the draft of a cannonball passing by’ – was used as a catchall category to describe soldiers who suffered effects from close proximity to shelling. Soldiers might freeze, have difficulty with motor coordination, collapse or lose consciousness, generally without being struck by the gunfire.Footnote 38 By the mid-to-late nineteenth century, however, some medical professionals analysed the psychological effects of shelling on non-military personnel.Footnote 39 As he worked treating Parisians suffering from physical and psychological conditions, for example, Dr Henri Legrand du Saulle noted that the people living in the quartiers most affected by the January bombardment indeed suffered from extreme terror and inability to sleep.Footnote 40 These Parisians hid in their cellars, paced and spread the wildest rumours. Legrand du Saulle noted that the most strongly affected were:

prey to a true panophobia, to visual hallucinations and illusions of hearing, to the most dismal delirious conceptions, to hyperesthesia and tremblings of the entire body, they arrive at the Dépôt municipal des aliénes with their bodies bent forward, in the position of the most extreme grief. They are weeping, moaning and always repeating the same words: ‘Ah, my God, my God. – Everything is lost! – What's going to happen to me’?Footnote 41

Legrand du Saulle also noted that over the course of several days in January 1871, he treated multiple cases of a rare type of mélancolie avec stupeur. Describing this condition as an intense disruption of the senses – these individuals could barely see, hear or speak – Legrand du Saulle argued that ‘this kind of suspension or temporary annihilation of all the faculties … [is] seen in cases of profound upset, sudden extraordinary events, excessive joy or extreme fear’.Footnote 42

Elements of Legrand du Saulle's writings illuminate a clear connection between traumatized Parisians of 1871 and analyses which would emerge nearly half a century later in the midst of World War I. Legrand du Saulle believed in ‘adverse heredity’ as a predisposing factor in these conditions, arguing that individuals who were easily impressionable, hypochondriac, melancholic or suffered from other hereditary mental issues were particularly susceptible to terror – an idea that would still have currency in 1914.Footnote 43 Legrand du Saulle's accounts of Parisian residents certainly described a familiar cluster of hyperarousal symptoms and problems of perception: insomnia, tremblings and tremors, inability to straighten the body, extreme hypervigilance of the nervous system and – in the more intense cases of mélancolie avec stupeur – mutism, loss of sensory function, incontinence and thoughts of self-harm or suicide. His description of the bent bodies of suffering Parisians is particularly suggestive. In 1915, neurologists Achille-Alexandre Souques and Inna Rosanoff-Saloff coined the term ‘camptocormia’ for the ‘stooped posture of the trunk’ of soldiers injured in the trenches of World War I. Souques and Rosanoff-Saloff noted the injury could be a conversion disorder caused by neurosis, especially from anxiety related to the battle, and that the patients might remain in this bent-forward position for extended periods of time.Footnote 44 While Legrand du Saulle's account from the bombardment period of l'année terrible did not create a specific term for the prostrate positions of the terrorized Parisians he treated, his narrative certainly forges a link between the embodied reactions to shelling in 1871 and the later ‘traumatic neuroses’ suffered by soldiers during the grand guerre.

Sounds both Carnivalesque and Catastrophic: The Paris Commune

Broken by the bombardment, France's interim government signed an armistice, agreeing to crippling war indemnities and the loss of Alsace and much of Lorraine. In elections following the armistice, France mainly sought moderate candidates or the restoration of a monarchy, yet Paris selected radical deputies. Unrest – which had roiled Paris through 1870 and 1871 – came to a head over cannons belonging to the Parisian National Guard. On 18 March 1871 the regular French army deployed at dawn to working-class Parisian neighbourhoods such as Montmartre, planning to seize cannons held by the National Guard.Footnote 45 Accounts of this day's events resonate with a web of Parisian revolutionary sounds: the drum beats of the rappel and générale called for the National Guard to assemble, bugle calls warned the citizenry to disperse, enumerated gunshots spelled additional warnings.Footnote 46

As the regular army failed to seize the cannons and eventually fraternized with the citizenry of Montmartre, chroniclers detailed a sonically chaotic, carnivalesque atmosphere in strongly gendered narratives. Georges Clemenceau described the scene as ‘perfect bedlam’, and Edmond Lepelletier noted the ‘noisy confusion’ of the cheering, jeering, singing crowd.Footnote 47 Gay Gullickson's fascinating analysis of the 18 March crowds analyses how women of Montmartre were remembered as noisier than men, issuing a series of ‘reproaches, demands, inarticulate sounds and insults’.Footnote 48 In his work on the US Civil War, Smith has analysed how white upper-class Southerners equated quietude with virtue, whereas a woman ‘unsexes herself’ through unsuitable noise.Footnote 49 As Smith demonstrates, noise is often a particularly telling marker of the aural abject, denoting what a particular listener finds objectionable about the class, gender or race of specific subjects. In this foundational triumph for the creation of the Commune, the hill of Montmartre noisily resounded not just with the sonic marks of revolution, but also with sounds that bourgeois commentators constructed and remembered as the abject noises of working-class female revolutionaries.

Due to this failed attempt to seize weaponry from the National Guard, and related violence such as the deaths of Generals Clément-Thomas and Lecomte, the regular army and government fled and established a stronghold at Versailles, while leftists, workers and the National Guard proclaimed a ‘Commune’ in Paris. Again noting the sonic character of such revolutionary moments, De Goncourt wrote in his journal on 20 March, ‘Three in the morning. I am awakened by the alarm bell, the lugubrious tolling that I heard in the nights of June 1848. The deep plaintive lamentation of the great bell at Notre Dame rises over the sounds of all the bells in the city, giving the dominant note to the general alarm, then is submerged by human shouts’.Footnote 50 Prosper-Olivier Lissagaray, a Communard, remembered the sounds of the official inaugural ceremony of the Commune on 27 March as resounding with battalion drums, trumpets, cannons and the singing of the ‘Marseillaise’ and the ‘Chant du Départ’, all blending in ‘one formidable vibration’.Footnote 51

After the proclamation of the Commune in March 1871, the Versailles army besieged and bombarded Paris for a second time in an attempt to retake the city, startling inhabitants already unnerved by the earlier months of siege and bombardment from the Prussians. During the three months of the Commune, new soundmarks emerged in Paris. As Communard fighters perished during battles with the regular army camped outside the city, the Commune venerated their memory and fuelled resentment against the Versaillais by conducting large-scale public funerals. These daily processions began on 6 April; Lissagaray detailed the thousands of men, women and children in the streets, ‘immortelles in their button-holes, silent, solemn, marched to the sound of the muffled drums. At intervals subdued strains of music burst forth like the spontaneous mutterings of sorrow too long contained.’Footnote 52

Atypical soundmarks intensified by late April 1871. The US minister to France, Elihu Benjamin Washburne, described a Paris marked by unusually silent places: all the factories, workshops and sounds of industry were quieted, the Champs-Elysées was deserted and the noisy cafés closed at ten o'clock. Yet the city also vibrated with strange sounds; from his residence at No. 75 Avenue Uhrich, Washburne heard the omnipresent ‘roar of cannon, the whizzing of shells and the rattling of musketry’.Footnote 53

Like d'Indy's attentive listening during the January siege, De Goncourt tuned his ears to listen carefully to the shelling from Versaillais forces. He noted on 16 April, ‘Yesterday provided me with a serious study of acoustics. I did not know what caused a sort of agonizing wail which I once took for a moaning man. I had read in the paper that it was the special sound of shells. I had heard it was a whistling in the grooves of the lead sheath. Now I know that this wail comes when a concave shell fragment is projected a very long distance’.Footnote 54 He commented, nearly a month later, on the psychological toll of these events on Paris's inhabitants, writing ‘all the people you meet on the street talk to themselves aloud like crazy people – people from whose mouths come words like desolation, misfortune, death, ruin – all the syllables of despair’.Footnote 55

During the infamous semaine sanglante (‘bloody week’) of late May 1871, the Versaillais army entered the capital and, in a bloody civil war, suppressed the Commune in violent fighting, street by street. Accounts of the semaine sanglante note the covert entrance of the Versaillais army into western Paris early in the morning of 21 May. Lissagaray recalled this moment as an ominous cessation of noise: ‘the cannon were everywhere hushed – a silence unknown for three weeks’.Footnote 56

Communard leaders gradually acknowledged the breach of their defences by a resumption of noise: the rappel was beaten all night on 21 May in the working-class district of Batignolles. The next morning, the tocsin rang throughout the city while Communard soldiers beat the générale. Footnote 57 Alain Corbin notes that the tocsin – generally hurried, redoubled and discontinuous strokes on a small bell – elicited physical and psychological effects in nineteenth-century auditors, including ‘fear, panic and horror’.Footnote 58 Indeed, the Commune's ministry had debated sounding the tocsin at all, ‘on the pretext that the population must not be alarmed’.Footnote 59 Anti-Communards, however, welcomed the tocsin as a sound of deliverance. During the long night of 21 May, De Goncourt wrote in his journal:

I go back to bed, but this time it really is the drums, it really is the bugles! I hurry back to the window. The call to arms sounds all over Paris; and soon above the drums, above the bugles, above the clamor, above the shouts of ‘To Arms!’ rise in great waves the tragically sonorous notes of the tocsin, which has begun to ring in all the churches – a sinister sound which fills me with joy and marks the beginning of the end of the hateful tyranny for Paris.Footnote 60

Legrand du Saulle, still stationed in Paris, reported that the tocsin chimed day and night while cannons thundered in the streets, powder magazines exploded and the sounds of shots echoed everywhere.Footnote 61

In addition to the tocsin, layers of belliphonic sounds horrified many Parisians during the semaine sanglante. Augustine-Melvine Blanchecotte, hiding during an endless night on 23 May, wrote of the awful combination of machine guns, cannon fire, the screams of shells, the racket of paving stones, yells from combatants, the falling of bodies, the certainty of an explosion. Like many, she drew particular attention to the terrifying new sound of the mitrailleuse, a volley gun that could fire multiple rounds in rapid succession.Footnote 62 In a suggestive account, Lillie Hegermann-Lindencrone, a singer and banker's wife, detailed the sounds of violent revolt and her state of profound nervous anxiety during the semaine sanglante. In letters to her family, she lamented her inability to sleep, to function normally, even to change her clothes. She mentions that singing – usually a source of comfort – was unable to assuage her anxiety. On 25 May, she noted the horrid sounds of the fighting in the Faubourg St. Honoré: ‘when I open the door of the vestibule, I can hear the yelling and screaming of the rushing mob; it is dreadful, the spluttering of fusillades and the guns overpower all other noises’.Footnote 63 Notably, not all Parisians were traumatized by the city's chaotic sonic violence: some became accustomed to the sounds, while others found them mesmerizing. Louise Michel, ardent Communard and anarchist, noted the ‘beauty’ of revolutionary sounds and chattering machine guns, stating: ‘barbarian that I am, I love cannon, the smell of powder, machine-gun bullets in the air’.Footnote 64

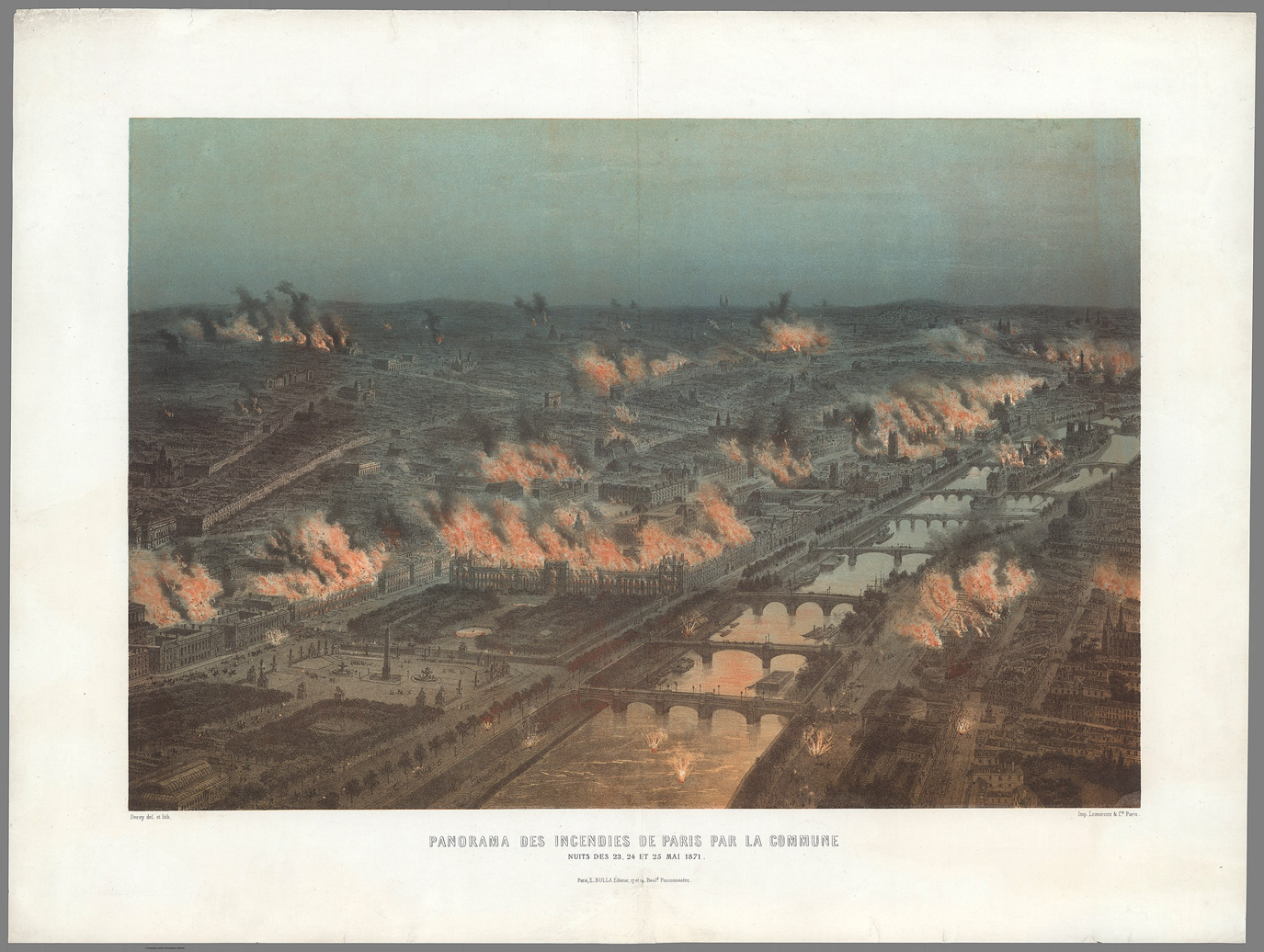

Fires swept Paris during the Commune, increasing the sensory chaos, filling the city with ash and smoke and clouding the vision of Parisians (Fig. 2).Footnote 65 This foul miasma had two effects: first, it rendered sound as a more cogent means of information than the uncertainties of sight. Parisians listened hard for reports of gunfire around the corner or shouts of troops progressing down the street, knowing that sonic vigilance would increase their chances of survival.Footnote 66 Yet the loss of clear vision also enhanced the sense of confusion, intensifying the psychological effects of the belliphonic noises that filled Paris.Footnote 67 Benoît Malon, a Communard, explained the powerful combined effects of the city's sounds, sights and smells on the mind. Malon described the sound of shells, clanging bayonets and Gatling guns mixing with cries of agony, ‘all of that in an atmosphere of fire, under a crimson sky; divided by billowing flames that rise above the burning palaces, reducing even the strongest men to a stupor’.Footnote 68 On 24 May, Edwin Child noted in his diary:

about 1/2 past 9 we began to hear the roaring of the cannon, the gnashing of the mitrailleuses and the continual roar of the fusillade which towards the afternoon became terrible, at the same time the bombs whistled overhead, spreading terror in the whole neighborhood … it seemed literally as if the whole town was on fire, and as if all the powers of hell were let loose upon the town, all day we could hear that terrible din that never ceased for an instant not knowing at what moment our own turn might arrive.Footnote 69

The sounds of Paris's fiery destruction were themselves rendered into a musical metaphor by actress Marie Colombier, who wrote that ‘the fire roared like a basso continuo, interrupted from time to time by sharp crackling sounds’.Footnote 70

Fig. 2 Panorama des incendies de Paris par la Commune. Nuits des 23, 24 et 25 mai 1871, lithograph by Isidore Laurent Deroy

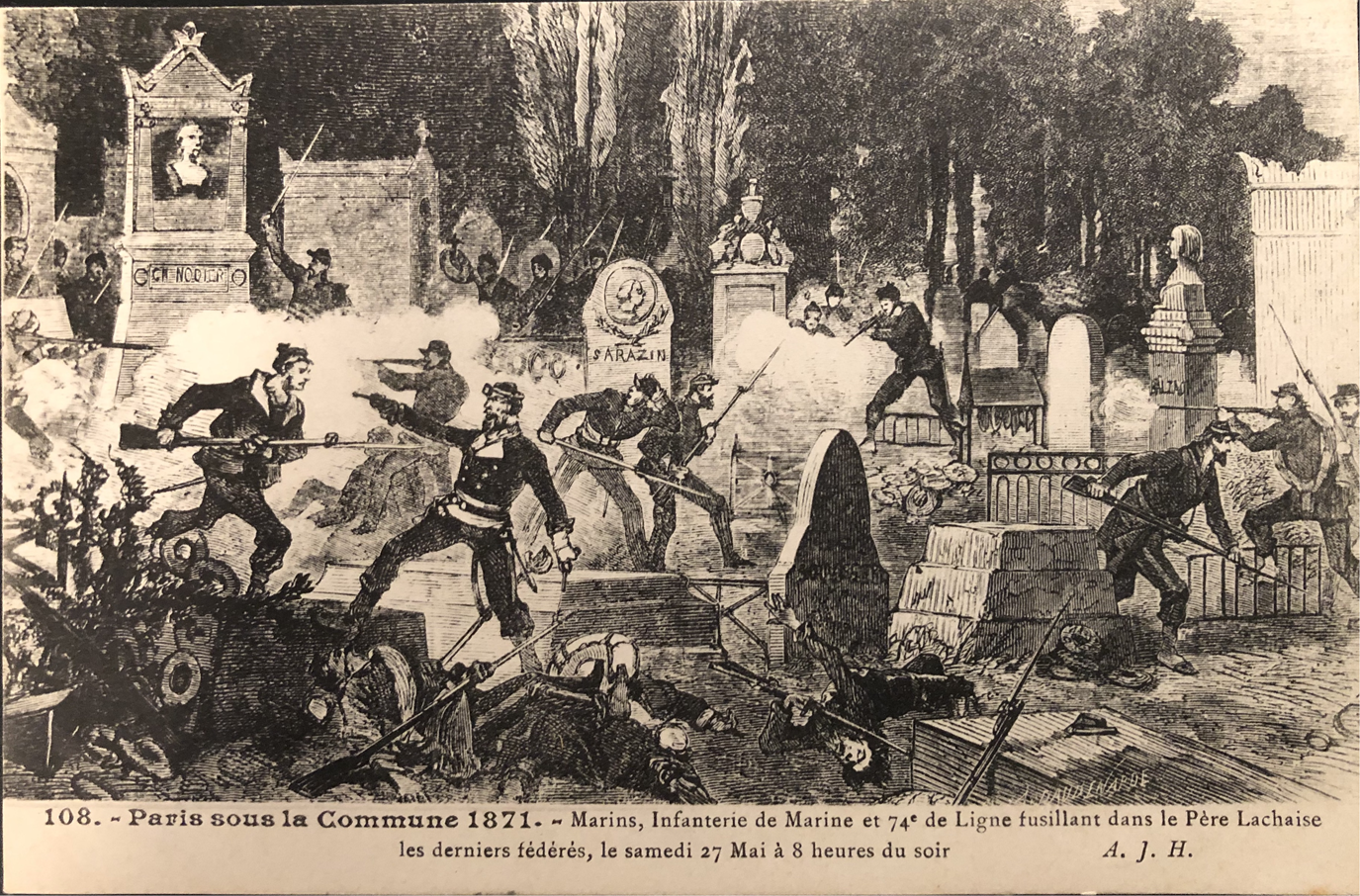

As the Versaillais army pursued the last Communards eastward through the city – finally ending in bloodshed in Père Lachaise on 28 May (Fig. 3) – Parisians moved through an urban landscape filled with death. Killed by firing squad, Communard corpses were buried en masse at the prison of La Roquette, the École Militaire, the Parc Monceaux, Lebau Barracks, the Luxembourg Gardens, the Jardin des Plantes and many others.Footnote 71 Renowned photographer Félix Nadar recalled the sights and sounds of huge numbers of Communard prisoners marched out of Paris to internment camps, where they were shot, imprisoned, deported or freed.Footnote 72 While exact numbers are difficult to ascertain, the Versaillais government murdered somewhere between 10,000 to 30,000 Parisians during this savage repression. Accounting for the dead was particularly contentious: both contemporary tallies and later analyses by historians varied widely on the actual number of Communards killed during the conflict. These discrepancies made it more difficult to mourn loved ones who disappeared and were presumably buried in unknown places.Footnote 73

Fig. 3 L'agonie de la Commune’, engraving by Amédée Daudenarde for Le Monde illustré, 24 June 1871, collection of the author

Though the conflict officially ended in late May, Émile Zola recalled that the sounds of gunfire still resonated throughout the streets of Paris in June, as army firing squads meted out ‘justice’ by shooting Communards. Carts, coaches and wagons filled with corpses rattled across the city for weeks, while other mass casualties were buried quietly at night.Footnote 74 Augustine-Melvine Blanchecotte drew specific attention to horrifying new sounds of the Parisian summer of 1871. Though she had thought the sound of shelling incomparable, she heard even more chilling sounds after the semaine sanglante – sounds that served as an ever-increasing series of traumas for some Parisian listeners. In her entry for 13 June, she detailed:

Between midnight and one o'clock a.m., singular rolling sounds of a muted, strange and mournful omnibus, a sound which cannot be mistaken once it has been heard; these are, throughout Paris, the exhumations of the dead … [the] sound of shells, which I thought incomparable, was only innocent music beside these most recent noises. The most heartbreaking, the most unforgettable has been – between the Pantheon and the Luxembourg Gardens – these nocturnal noises, for an entire week, these incessant shots of the firing squad, these hasty decisions of human justice.Footnote 75

Blanchecotte then notes, ‘Parisians are supposed to be asleep. Blessed, oh! yes, blessed are those who sleep! The dreadful task imagines it is silent, as it imagines itself to be without witnesses.’Footnote 76 While the coverup of a massacre was hidden by darkness, Parisians could not close their ears entirely to these macabre sounds.

In fact, the difference between the sounds and sights of violence was one of the strongest markers of trauma for Parisians versus those outside the city. The rest of the world was privy to sights – rather than sounds – of catastrophic violence. As Howard Brown analyses in his study of visual representations of the Commune, graphic lithographs of corpses and executions – ‘every gory aspect described in shocking detail’ – fed an avid desire for macabre sights of a society coming undone.Footnote 77 After May 1871, tourists bought photographs of Paris's smouldering ruins, and the photographed corpses of Communards were likewise readily available for purchase. These images perpetuated an iconography of violence that lacked the sounds (and smells) of the first-hand accounts. Smith's work on the Civil War reminds us that images retain ‘tantalizing traces’ of the sonic, but it is essential to consider that the very technologies that preserved the visible violence of the year's events often occluded the sonic traumas endured by those within earshot.

II. Sound and Nineteenth-Century Trauma

There is ample testimony that the sounds of 1870–71 lingered in the minds and ears of Parisians. When Émile Zola described the sounds of gunfire still resonating throughout the streets in June 1871, he commented on the millions of Parisians left with nightmares, terrors that could only begin to heal once the sounds quieted. Blanchecotte similarly noted that despite the end of the conflict, ‘the cannon's vibration still lingered in the ears, the shaking of the spirits did not ebb away and the despondency of the dead city persisted’.Footnote 78 Years later, as Colette Wilson has analysed, the noisy fireworks of the 1878 Exposition Universelle – which sounded like bombshells – may have been triggering for listeners who had experienced the sound of gunfire in those precise Parisian locales.Footnote 79

Attending to sound reveals how constant noise or abject silence tortured Paris's inhabitants during l'année terrible. In his writing on sonic warscapes, Martin Kaltenecker defines a ‘pathological kind of hearing’ in wartime, a constant listening through which a subject strains to hear and interpret sounds. Kaltenecker notes that war can (temporarily) create ‘sound displacements, where ordinary sounds arise in places where they wouldn't in peacetime’.Footnote 80 Indeed, the sonic effects of 1870–71 rendered the familiar unfamiliar, unsettling Parisians as their city was shattered and remade not just by bullets, but also by sound. Paris seemed divided in two by sound as much as by ideology, a city with dualistic phonosphères. This city's sonic discourse was both familiar – the recurrent barricades, century-old revolutionary songs, the tapestry of bells, bugle calls, the rappel and the générale – but also riven by the uncanny new sounds of the mitrailleuse and the Krupp siege guns. Paris's sonic discourse was displaced, with sounds occurring in ‘seemingly impossible’ places, such as those of the bullets and cannons that ultimately silenced the last Communards in Père Lachaise. In his study of the US Civil War, Smith notes that the ‘introduction of new noises and the muting of old sounds’, or noises ‘that threaten the customary soundmarks of a particular locale’, can actually fatigue listeners to the point of hastening capitulation and increasing trauma during a conflict.Footnote 81 Moreover, there was no distinction between home-front and battlefield during this conflict: whether soldier, civilian, revolutionary or citizen – categories which were considerably muddied – all residents of Paris contended with the sounds of 1870–71.Footnote 82

Responses: Illness and the Asylums

Numerous Parisians were hospitalized due to the year's events. In an 1872 presentation to the Académie des sciences, a Dr Laurent noted the explosion of more than 1,700 cases of folie (madness) in 1870–71; Laurent also notes that 13 per cent of those hospitalized between July 1870 and July 1871 were interned due to ‘diseases’ related to the events of the year. Breaking down his numbers more precisely, he notes that the percentage was about 15 per cent for men and 9 per cent for women. During the Commune in particular, Laurent reported that French asylums took in hundreds of patients who had become mad due to the year's events. These statistics are tantalizingly incomplete – and linked with mental illness and insanity in problematic ways, as discussed below – but they nevertheless suggest that many Parisians found the sights, sounds and experiences of the année terrible unbearable, some to the point of hospitalization.Footnote 83

Reportage, memoirs and fictionalized accounts alike suggest that Parisians were intensely affected by the year's events physically and psychologically. In his popular novel Les Amours d'un interne, journalist Jules Claretie sensationally detailed affairs between women ‘hysterics’ and doctors at La Salpêtrière. In one scene featuring a woman interned during 1871, Claretie wrote, ‘the sinister days of the end of this year and the fierce crisis that shook Paris at the beginning of the following year, rekindled the poor woman's frightful neurosis, exacerbated by the suffering of the siege and the terrors of the Commune’. He continues by noting that for these many girls in the hospital, ‘science’ almost always indicates that their maladies were caused by ‘this heartbreaking thing: the civil war. It not only kills bodies, but also minds, and we think of walking corpses.’Footnote 84

While not based in Paris – he was director of the asylum at Saint-Yon in Rouen – French psychiatrist Bénédict-Augustin Morel observed numerous men and women in states of overwhelming anxiety and terror due to the invasion by Prussian troops in late 1870.Footnote 85 Isolated and vulnerable, residents in the path of the army feared requisitions, pillage, destruction by fire and sexual violence. While analysing these factors, Morel includes an intriguing aside: describing the topography of the Pays de Caux plateau in the department of Seine-Maritime, he notes: ‘the houses, surrounded by large trees to protect them from the ocean winds, are generally quite far from each other. From one farm to the other it was sometimes difficult to know what was happening, yet this isolation did not keep the most alarming noises from being audible.’Footnote 86 Morel's comment suggests particular soundscapes might – in tandem with other factors – intensify the impacts of war.

In a report to the Société médico-psychologique on 26 June 1871, Morel argued the year's horrible events had strikingly increased cases of a distinct type of intense anxiety (panophobie gémissante). Struck by the terror of these ‘panophobes’, Morel observed that ‘their faces grimace like they will cry, but they do not shed tears. Some squat with their clothes raised above their heads. The only sign of life that they demonstrate is to moan in an incessant rhythm accompanied by automatic gestures that become tics in time with their moans.’ Morel added that some individuals who spent months in this state lapsed into ‘an extreme immobility, a lack of motion that I find almost cadaverous in certain cases’.Footnote 87 Earlier in his career, Morel understood this kind of delirium as madness, but now – in 1871 – he categorized this particular panophobia as markedly different from either ancient ideas of melancholy or the kind of depressive state (lypémanie) more recently defined by Jean-Étienne Dominique Esquirol.Footnote 88 Though careful to explain this panophobia was not a new condition, nor solely caused by war, Morel unequivocally argued that the war of 1870–71 unusually increased its impact.

Contexts: Folie, maladie mentale, and connecting politics to the mind

Like Morel, other French commentators turned to preexistent psychological and medical models in an attempt to come to terms with the events of 1870–71. As Catherine Glazer summarizes in her analysis of the Commune as ‘maladie mentale’, French physicians, historians and other writers reflected at length about relationships between l'année terrible and madness. Borrowing an old framework dating back to early nineteenth-century works on folie by Étienne-Jean Georget and Esquirol, commentators newly pondered the relationship between political events and disorders of the mind.Footnote 89 Specific positions varied from author to author, but many connected social class, political events and madness, questioning whether people who are already ‘mad’ take part in revolutions, or whether revolutions cause those with a predisposition to insanity to become ill.Footnote 90

Comparing adherents to a cause to people driven insane by religious fervour, Claude-Joseph Tissot and Claude-Étienne Bourdin described the revolutionary crowd as mad, suggesting that political upheaval was the cause of mental chaos.Footnote 91 Suspicion of two groups – ‘pathological crowds’ and the working classes – drove much of this late nineteenth-century analysis. The historian Hippolyte Taine, writing in the years immediately after l'année terrible, forged an influential ‘biohistorical’ model of revolutionary crowds as pathological, monstrous, bestial forces of chaos.Footnote 92 A plethora of other works on crowd psychology – many in reaction to the events of the Commune – appeared in the 1880s and 1890s, including Gustave Le Bon's Psychologie des foules.Footnote 93 In addition, certain French writers pathologized working-class participants in the Commune as the ‘dangerous classes’, drawing on degeneracy theories by Bénédict-Augustin Morel and others.Footnote 94 The physician Jean-Baptiste Vincent Laborde's 1872 book on ‘morbid psychology’ and Parisian insurrection similarly defined maladie mentale as a kind of collective social insanity that could cause certain individuals to create societal disasters such as the Commune.Footnote 95 In their 1905 work La contagion mentale, the doctors Auguste Vigouroux and Paul Juquelier argued that psychological states were contagious.Footnote 96

A number of writers throughout the nineteenth century questioned whether individuals exposed to intense fear and terror might transmit these states to their descendants. Esquirol, in his influential 1838 definition of lypémanie – a specific subset of monomania, namely an extreme melancholy or sadness – not only noted that political events could greatly increase both monomania and the number of suicides, but that children conceived or born during the horrors of 1793 were much more likely to exhibit mental health problems.Footnote 97 Authors later in the century borrowed and retooled Esquirol's ideas, including Bénédict-Augustin Morel and Legrand du Saulle, who pondered how events of l'année terrible might be bequeathed to subsequent generations. ‘Revolutions can create terror’, Legrand du Saulle noted, ‘and terror can not only change the intellectual state of present generations, but also weigh heavily (by means of heredity) on the mental dispositions of future generations’.Footnote 98 Legrand du Saulle was writing within the framework of ‘predisposition’ and degeneracy theories; for instance, he compared the effect of terror to that of a child born to a parent addicted to alcohol. Even so, his musings might evoke (to us) hints of current epigenetic theories that suggest that trauma's effects can indeed be passed down through multiple generations.Footnote 99

Contexts: Early Trauma Theories

Within the chaotic soundscape of Paris, eminent French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot not only experienced the horrors of war first-hand, he also began to transform his pivotal ideas on hysteria into concepts which would revolutionize early medicalized discourse on trauma. Charcot gave his first lecture on hysteria at the Salpêtrière in June 1870, just before the outbreak of the war; the conflict interrupted his teachings for almost two years. According to a later account by his son Jean-Baptiste Charcot, during the January 1871 siege Dr Charcot travelled by carriage from his home in the 9th arrondissement to the Salpêtrière in the 13th. Passing by the Jardin des Plantes in the 5th arrondissement one morning, Jean-Baptiste Charcot recalled that his father ‘was disturbed in his reading by a shell that passed through both windows of his carriage’.Footnote 100 Afterwards, Charcot was close-mouthed about l'année terrible: he only referred to the cataclysms as ‘the events about which you know’.Footnote 101

In the late 1870s, Jean-Martin Charcot began to work on what he deemed ‘male hysteria’ – variously characterized as ‘névrose traumatique, hystérie traumatique, hystéro-traumatique, or hystéro-neurasthénie traumatique’. All of these diagnoses focused on nervous crises prompted by a triggering traumatic event. Charcot believed that ‘intense fright, mediated through a kind of quasi-hypnotic unconscious mental process, could precipitate physical symptoms in individuals with premorbid constitutions’.Footnote 102 Charcot diagnosed around 90 cases of male hysteria, almost exclusively of working-class men who suffered paralyses, contractures, sensitivity or lack thereof to touch, melancholia and alterations in vision after an accident.Footnote 103

One of the most provocative narratives in Charcot's 1889 Leçons du mardi à la Salpètrière concerned ‘D…cy’, a 45-year-old former soldier traumatized after being struck by lightning.Footnote 104 Charcot noted that ‘D…cy’ had served at the Battle of Puebla in 1862 – ‘where the thunder roared as loudly as the cannons’ – fought in multiple campaigns of the Franco-Prussian War, and was not only part of the Versaillais army during la semaine sanglante, but also was wounded during the final battle in Père-Lachaise, ‘where shells rained down’.Footnote 105 As Charcot questioned the patient during his demonstration, ‘D…cy’ recounted that the sound of the traumatic thunderclap ‘was like a cannon shot, accompanied by the clatter of a thousand plates falling to the ground’, causing the patient to ‘tremble and cry like a child’. Charcot pointed out that this was not a man known for nervous susceptibility or sensitivity to the sounds of war, noting that ‘D…cy’ ‘had not cried or trembled at the Battle of Puebla when thunder and cannon had raged together, nor did he cry at Père Lachaise, when a shell burst quite close to him’. The thunderclap and lightning, however, radically transformed him into one of Charcot's most demonstrative examples, a man who ‘shakes, stammers and bursts into tears incessantly’.Footnote 106 Charcot did not pursue the question of whether ‘D…cy's earlier experiences might have precipitated the traumatic reaction to the lightning strike; he was primarily interested in considering how the lightning's electricity might have prompted the neurological symptoms. Yet what is striking in this case study is Charcot's casual admission that the man had already been exposed to much more ‘dramatic’ and ‘terrifying’ episodes during wartime, and that some of these terrifying experiences were sonic, namely the sounds of cannon fire.

Through Charcot's work on male hysteria, he established several important observations on trauma, namely that an event or injury may create a loss of sensation seemingly unrelated to any physical wound, and that patients often suffered a delay between the injury and the onset of symptoms.Footnote 107 Other than the case of ‘D…cy’, few of Charcot's case studies made any connection between wartime traumas and ‘hysteria’. Yet Micale notes that Charcot's first publication on traumatic male hysteria dates from 1878, with publications on the subject continuing through the 1880s and early 1890s. Micale highlights a chronological similarity that ‘the lag in time between the military experiences of 1870–71 and the appearance of these writings is the same as the duration between the American involvement in the Vietnam War and the formulation of the diagnostic category of post-traumatic stress disorder’.Footnote 108 It does seem likely that there are links between the events of l'année terrible and the causation, discovery and theorization of male hysteria. Charcot was not the only French neurologist concerned with new understandings of male hysteria at this time: 16 French medical dissertations on male hysteria appeared between 1875 and 1895. Numerous researchers – most notably Emile Duponchel in the 1880s and 1890s – searched for hysteria in the army in particular, while civilians remained largely understudied as victims of wartime traumas.Footnote 109

Pierre Janet, who studied under Charcot at the Salpêtrière in the late 1880s and early 1890s, combined his interests in philosophy, medicine and psychology in an influential series of publications in the 1890s on ‘automatic’ (involuntary) actions and obsessions or fixations (idées fixes).Footnote 110 Janet spent the last years of the nineteenth century pondering the nature of ‘painful memories subconsciously fixed in the psyche’, inaccessible due to dissociation.Footnote 111 In his text Névroses et idées fixes (1898), Janet, like Charcot, provided a tantalizing example of an individual traumatized by the events of 1870–71. Almost 30 years after the Franco-Prussian War, Janet detailed the physical and psychological problems of a former French soldier who contracted frostbite in 1870. The man had a ‘horrendous memory’ of that freezing night, but no immediate psychological problems. Several years later, he served as garde-malade of a delirious typhoid patient; due to a frightening night spent in close proximity to the patient, the man became extremely agitated, paranoid and suffered from night terrors. After this second event, he suffered from fright and ‘dysesthesia’, unusual feelings of cold in the calf of his leg, in precisely the same location as the frostbite. In his case study, Janet called attention to the confusing connection between these two seemingly unrelated events, noting:

The dysesthesia seems to have nothing to do with the second adventure, the night spent near the typhoid patient, and yet it is after this second emotion that the condition appeared. This is, as we have often said, an extremely frequent event: an emotion weakens the strength or resistance of these patients and brings about the development, the manifestation of another long-ago phenomenon, caused by a much older emotion which (remaining latent in the brain) was more valid.Footnote 112

Both Charcot and Janet analysed former soldiers’ experiences of traumatic circumstances related to the war – whether sonic or a physical injury such as frostbite – that were then reignited by later events. Both doctors are clearly intrigued by these cases, and by the delay in onset or the connections between seemingly ‘unrelated’ events. Yet they fail to ask questions that might allow us a clearer glimpse at how physiological reactions might connect to psychological phenomena, or, indeed the ways these patients were traumatized through unexpected recollections. Moreover, Charcot and Janet were silent about (and perhaps unaware of) the ways in which non-combatants might have had similarly triggering experiences. Ultimately, their accounts offer tantalizing evidence, but also demonstrate obvious ways in which contemporary studies were limited by the cultural frameworks of the era.

III. Postlude: Memory, Sound, and Silence in Parisian Spaces

The sheer amount of coverage of l'année terrible marked a turning point in narrating trauma. Brown notes:

the flood of deeply personal accounts that so quickly followed the end of the fighting provided an unprecedented sense of what Parisians had experienced both physically and emotionally. Never before in France had there been such detailed, graphic, and personal accounts of suffering as accompanied the destruction of the Commune.Footnote 113

In an attempt to control the narrative, in December 1871 the Third Republic passed a decree ‘banning all representations of the Commune which the censors deemed to be “de nature à troubler l'ordre public” [of the sort to upset public order]’.Footnote 114 This attempt to muzzle memory reminds us of the critical connections between trauma and silence (scholars have theorized this in many twentieth-century contexts, ranging from Freudian repressive silences, to Dori Laub's analysis of the struggles of witnessing versus ‘not telling’ in relation to the Holocaust, to Cizmic's study on politicized silence in Soviet contexts).Footnote 115 Despite the Third Republic's decree, by the 1910s there were thousands of accounts of this period.

The flood of testimony recounted in this article demonstrates the extent to which l'année terrible served as a collective trauma for contemporary witnesses.Footnote 116 Jeffrey C. Alexander says that collective trauma occurs when a group has ‘been subjected to a horrendous event that leaves indelible marks upon their group consciousness, marking their memories forever and changing their future identity in fundamental and irrevocable ways’.Footnote 117 Kai Erikson has also demonstrated how a disaster or other event might connect a community but also damage the ‘tissues’ of the community, just like a wound to a body.Footnote 118 The damaging collective experience of 1870–71 spawned countless narrative, artistic and scientific reactions, testimonies which invoke Shoshana Felman and Dori Laub's observation that ‘issues of biography and history are neither simply represented nor simply reflected, but are reinscribed, translated, radically rethought and fundamentally worked over’ by texts.Footnote 119

Within these texts, acts and responses, however, collective trauma was processed in vastly different ways. Political ideologies (Communards versus Versaillais) alone radically shaped understandings of l'année terrible. Micale reminds us of trauma's ‘spectrum of responses’, how individuals often experience it non-traumatically, or in ways ‘not deemed medically noteworthy in their time’.Footnote 120 This plethora of responses underscores that not all contemporaneous experiences were traumatic ones, yet evidence certainly suggests that many Parisians were traumatized by the sounds and experiences of this year of war. As Parisians moved beyond the immediate aftermath of l'année terrible, they remembered its events in very different ways, just as the nature of memory itself was shifting.Footnote 121 And as they remembered, they fought over these memories, not just for their political import, but also through the very sounds and spaces where they could remember or reconnect with the traumatic past.

Two sites in Paris – the mur des fédérés (Wall of the Communard troops) in Père Lachaise cemetery and the Basilica of Sacré-Cœur on the butte of Montmartre – demonstrate how spaces served as intensely symbolic territory for continued debates about nineteenth-century trauma, sound and cultural memory. Throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, each of these spaces reverberated with remembered sounds from the period of the Commune. Moreover, opposite sides of the French political spectrum – supporters of the Communard cause versus adherents of Versaillais government policies – used sound almost as a weapon of commemoration in these spaces.

In the initial years after the violent ending of la semaine sanglante, Communard supporters began to call for a sacralization of space at Père Lachaise. While he did not mention any specific sites within the cemetery, Lissagary noted in 1876 that fédéré victims were buried in mass graves at Père Lachaise, Montmartre and Mont-Parnasse, ‘where the people in pious remembrance will annually come as pilgrims’.Footnote 122 After the general amnesty of Communards in 1880, an annual commemorative ritual gradually emerged at the mur des fédérés in Père Lachaise.Footnote 123 The rite began in silence, as a cortège filed through the streets of eastern Paris and entered the cemetery. Participants then listened to political speeches accompanied by cries of ‘Vive la Commune’.Footnote 124

Continuous fears of another uprising, however, led Parisian authorities to aggressively repress portions of this ritual. By 1895 processions and wreathes were allowed but speech was forbidden: participants filed by in silence under the watchful eyes of the police. In 1900, participants wrested some measure of sonic control by obeying the prohibition on political speeches but nevertheless sang ‘La Carmagnole’ and ‘L'International’. Sonic policing then expanded to explicitly forbid certain revolutionary songs such as ‘La Ravachole’.Footnote 125 At the mur des fédérés, silence was simultaneously an act of mourning commemorating earlier violence and a tool of state repression. Sound was equally multivalent as both politicized occupation and a revolutionary refusal to be repressed.

The basilica of Sacré-Cœur represents the other extreme of contested sonic remembrance of the Commune. The campaign to erect this sanctuary to the Sacred Heart originated with the monarchist Catholic right in 1871. Appropriating the site high on the butte of Montmartre necessitated an 1873 vote of ‘public utility’; the National Assembly noted that, ‘it was necessary to efface by this work of expiation, the crimes which have crowned our sorrows’.Footnote 126 The project's leaders explicitly described Montmartre as hallowed ground of recent martyrs, namely the Versaillais generals killed during the 18 March uprising in 1871.Footnote 127

Though Sacré-Cœur's cornerstone was laid in 1875, construction dragged on for more than 30 years. On 24 November 1918, composer Jean Roger-Ducasse attended the ‘Te Deum’ in the newly completed basilica. Thrilled by the brilliant Magnificat and the tolling of the church's giant ‘Savoyarde’ bell, Roger-Ducasse imagined winds carrying these most Catholic sounds from the heights of Montmartre to the tombs of France's soldiers fallen in the first World War.Footnote 128 It is difficult to contemplate a more conclusive sonic repudiation of the noisy Communard sounds of Montmartre. Crowned by an enormous white marble testament to ‘enduringly Catholic’ France, by the late 1910s the butte of Montmartre resounded with ecclesiastical sounds mourning the ‘great’ war.

Neither of these stories ends in the early twentieth century. The annual montée au Mur continues today on the Sunday closest to 28 May, accompanied by speeches and the singing of ‘Les temps des cérises’.Footnote 129 Sacré-Cœur still dominates the Parisian skyline, today accompanied by a new noisy din, not of revolution, but the chatter of tourists who fill the basilica's steps. Despite continuities and changes to both spaces, their histories testify to Daughtry's comment that ‘sound lives on in human memory far after its physical vibrations die away’.Footnote 130 Indeed, we might analyse the rites, memorials and design of these spaces as a way in which sounds themselves continue to inform intergenerational understandings of trauma.

***

In 1870–71, Parisians gathered in the streets, agonized, shuddered, hid from the bombs and looked on with horror at the nightmarish transformation of their Ville Lumière. They not only watched, they listened. Through this listening, they garnered crucial information, but also failed to shut out the noises of horror, the belliphonic sounds that rendered them sleepless, sick and, in some cases, unable to function. French neurologists and psychiatrists attempted to assess the ways in which these wartime injuries affected French minds and bodies, some drawing on earlier frameworks of madness and hereditary insanity while others forged newer models of understanding. Over the next 20 years, Charcot's work on male hysteria, a huge subsequent corpus of French medical work on traumatic hysteria, and Janet's publications on dissociation and involuntary memories each contributed to early understandings of the trauma concept, all works conceived amidst the cultural memories and traumatized populations impacted by the events of 1870–71.Footnote 131

As Parisians after the war struggled to banish the sounds of the year from their minds, they engaged in a decades-long battle over how to remember the terrible events of 1870–71. From the 1870s through the 1910s, thousands of narratives of the war, the siege, the bombardment and the Commune appeared; certainly these accounts represent political wrangling over the ‘truth’, but many likewise demonstrate a desire to testify, to remember, to account for those horrible days and weeks. As Parisians conversed with their pasts, the city itself bore not just visual reminders of the events, but sonic scars of remembered gunfire, screams, or shelling.

We have so many French testimonies from the later grande guerre, ranging from musician-soldiers carefully attending to the dangers of shells whizzing overheard to the plethora of medical examinations and analyses of soldiers suffering from shell shock, commotion and other neurological effects caused by war. Less well-understood are the ways in which that early twentieth-century war connects to this pivotal collective trauma of the late nineteenth century – the events of l'année terrible. When the tocsin sounded on 2 August 1914, how many Parisians froze, remembering the clanging bells of decades before?Footnote 132 When long-range German guns fired on Paris in March 1918, how many residents suddenly remembered the echoes of those earlier siege shells? As pioneering psychiatrists such as Janet continued to research and publish well into the mid-twentieth century, how did they incorporate their own knowledge of this nineteenth-century collective trauma into emerging twentieth-century discourse on trauma? These are challenging questions, but seeking to connect sound, the events of 1870–71, and early conceptions of trauma critically integrates these decades with the subsequent experiences of la grande guerre. Though attention to the traumatic effects of sound and war on human minds and bodies exponentially increased during World War I, these concerns were not new – they had been resonating in Paris decades before.