Background

In the DSM-5, a dissociative subtype was added to the classification criteria of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This subtype describes patients who meet diagnostic criteria for PTSD, and additionally have persistent or recurrent symptoms of depersonalisation (i.e. experience of unreality or detachment from one's thoughts, feelings, sensations, body or actions, for example, unreal or absent self) and derealisation (i.e. experience of unreality or detachment from one's surroundings, for example dreamlike or foggy1). The addition of a dissociative subtype to the DSM-5 was based on multiple sources of evidence, pertaining to factor analyses, brain activation patterns and response to treatment.Reference Friedman2

Approximately 14% of the patients with PTSD meet criteria for the dissociative subtype.Reference Stein, Koenen, Friedman, Hill, McLaughlin and Petukhova3 Although this subtype was only recently added to the DSM-5, research on dissociative symptoms in the context of trauma dates back to the nineteenth century.Reference Janet4 Several studies have shown that PTSD is associated with high levels of dissociation, both compared with non-clinical samples and patients with other psychiatric disorders.Reference Lyssenko, Schmahl, Bockhacker, Vonderlin, Bohus and Kleindienst5–Reference Kratzer, Heinz, Schennach, Schiepek, Padberg and Jobst8 Additionally, several studies have shown that dissociation is strongly related to the other PTSD symptoms and that these clusters wax and wane together, also in response to treatments.Reference Lynch, Forman, Mendelsohn and Herman9–Reference Zoet, Wagenmans, van Minnen and de Jongh13

A review of brain-imaging studies has shown that dissociative symptoms/states are related to activation of brain areas related to neurological overmodulation of affect.Reference Lanius, Vermetten, Loewenstein, Brand, Christian and Bremner14 This overmodulation of affect could, among others, reduce emotional engagement with the trauma memory, which is considered to be a relevant factor in understanding the effectiveness of current psychotherapies for PTSD.Reference Schnyder, Ehlers, Elbert, Foa, Gersons and Resick15 This lack of engagement may be specifically relevant for exposure-based psychotherapy as fear activation is thought to be a crucial mechanism underlying the treatment effect.Reference Lanius, Vermetten, Loewenstein, Brand, Christian and Bremner14,Reference Ebner-Priemer, Mauchnik, Kleindienst, Schmahl, Peper and Rosenthal16–Reference Cooper, Clifton and Feeny20

Aims

Currently, there is no consensus about (a) whether patients with PTSD and who dissociate benefit as much from psychotherapy as patients with PTSD who do not dissociate and (b) whether some forms of psychotherapy are particularly ineffective for patients with PTSD and dissociation. Some authors have suggested that treatment programmes need to be tailored for patients with PTSD who have dissociative symptoms, because, as a result of their limited emotion regulation capacities, trauma-focused treatments might even lead to an increase in PTSD symptoms, overall distress and functional impairment.Reference Lanius, Vermetten, Loewenstein, Brand, Christian and Bremner14 Others have argued that there is no evidence for an impeding effect of dissociation on the effectiveness of psychotherapy for PTSD.Reference van Minnen, Harned, Zoellner and Mills21 The aim of this study is to provide more clarity to this ongoing debate by quantifying the moderating effect of dissociation on the effectiveness of psychotherapy for PTSD in a meta-analysis.

Method

This project was pre-registered at Prospero (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=86575).

Search strategies

We conducted systematic searches in the following databases up to the 28 August 2018: Cochrane trials register, Embase, PILOTS, PsycINFO, PubMed and Web of Science. Relevant results during the search of review articles, book chapters and studies were searched for further studies and additionally, key authors and research groups were contacted via email to request any data relevant to the study. Search terms were based on (MeSH) terms for PTSD [AND] dissociation [AND] psychotherapy and were adapted to every specific search engine to ensure inclusion of all relevant studies. The search includes the following terms for:

(a) PTSD: Posttrauma* Stress Disorde*, Post-Trauma* Stress Disorde*, Post Trauma* Stress Disorde*, DESNOS, CA-PTSD, C-PTSD, PTSD;

(b) dissociation: Dissocia* Depersonali* Derealization* Derealisation* Fugue* Psychogenic amnesia, and

(c) psychological treatment: Psychotherap*, Therap*, Posttraumatic Growth, Interven*, Treat*, Exposure, EMDR, CBT, STAIR, Recover*.

We manually searched for studies in prior meta-analyses and reviews to ensure that no studies were missed in the systematic search. We de-duplicated data of the search following the protocol of Bramer and colleagues.Reference Bramer, Giustini, de Jonge, Holland and Bekhuis22

Inclusion criteria

The criteria for individual papers for inclusion were: (a) inclusion of patients who were 18 years of age and older; (b) assessment of PTSD according to the DSM-5, DSM-IV, DSM-III-R or DSM-III criteria; (c) evaluation of psychotherapy with PTSD symptom severity as main outcome; (d) inclusion of validated self-report measures or structured clinical interviews to assess both PTSD symptom severity and dissociation severity; (e) assessment of PTSD symptom severity at pre- and post-treatment; (f) assessment of pre-treatment dissociation severity; (g) inclusion of at least ten participants per treatment condition which is analysed; (h) published in a peer-reviewed journal; and (i) written in English, Dutch, German, Italian, Spanish or French.

Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

Eligible studies were screened twice and data were extracted twice by two independent screeners. All discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus. Risk of bias of the studies was assessed independently by two of the authors using the Cochrane risk of bias tool, which resulted in a methodological score for each study included.Reference Higgins and Green23 The Cochrane scale assesses sources of bias including selection bias, detection bias and attrition bias. We added two items to this measure about: (a) the type of the PTSD measurement (clinical interview versus self-report); and (b) treatment integrity (whether the original article reported on treatment integrity, yes versus no). Consequently, the adapted Cochrane scale consisted of eight items (see supplementary Table 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.30). Two raters scored each item, and their scores were summed into a risk of bias score (range 0–16; with higher scores indicating higher risk of bias). The risk of bias score was used as a moderator. High bias scores were not considered an exclusion criterion for further analysis.

Potential moderators

To investigate potential moderators of the effect of dissociation on psychotherapy outcome, we coded several study characteristics: (a) completely trauma-focused treatment (yes versus no); (b) randomised controlled trial (yes versus no); (c) sample size (continuous variable); and (d) risk of bias score (continuous variable). The potential moderators were independently coded by two authors and differences were resolved through discussion and consensus.

We compared treatments that were exclusively trauma focused versus those that were not. As dissociation is thought to be because of failing emotion regulation capacities, exposure to traumatic memories would result in emotional overmodulation and consequently impede fear activation and emotional learning. This may prevent the therapeutic effect of exposure, unless emotion regulation or other coping skills are also addressed.Reference Lanius, Vermetten, Loewenstein, Brand, Christian and Bremner14 The treatment was coded as trauma focused if it comprised only evidence-based trauma-focused treatment strategies as described in the manuscript (i.e. prolonged exposure, cognitive processing therapy or eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing). Treatments that also comprised other treatment components (i.e. physical activity or stabilisation) or treatments that did not include trauma-focused treatment strategies were coded as not exclusively trauma focused. If a trial included both types of treatments, we extracted the effect size for the two conditions separately for this moderation analysis (see supplementary Fig. 1 for details).

Statistical analysis

The R package meta was used for all analyses.Reference Schwarzer24 The effect of dissociation on PTSD treatment was determined using pooled effect sizes of the moderating effect of dissociation measured with the Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) between pre-treatment dissociation and change in PTSD symptoms from pre- to post-treatment (post-treatment minus pre-treatment PTSD symptom severity score). A positive correlation would indicate a negative relationship between dissociation and treatment effectiveness, whereas a negative correlation would indicate a positive effect of dissociation on treatment effectiveness. Where needed, we calculated the reported effect size from the data provided into r as common metric.

In cases where we were unable to calculate the effect size from the publication, we contacted the researchers for additional data. We contacted 38 researchers of whom 27 responded. Twelve of these researchers did not provide the data for various reasons (for example no access to data, no time to get data, not willing to share data). Fifteen researchers provided the requested data. Twelve of these studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis.

We used a random-effects model that allows heterogeneity between studies (assessed with the Q index) and performed a rank test to detect asymmetry in the funnel plot, which is an indication of publication bias. If we had any indications of publication bias either by the rank tests or by visual inspection, we used a trim and fill procedure to correct for bias because of missing studies. In case of a statistically significant main finding of dissociation on treatment effectiveness, we performed the fail-safe tests of Rosenthal and Orwin to assess the robustness of the results. We conducted moderation analyses with a meta-regression approach by fitting mixed-effect models including potential treatment moderators to test for differences in the effect size associated with characteristics of the studies.

Results

Selection and inclusion of studies

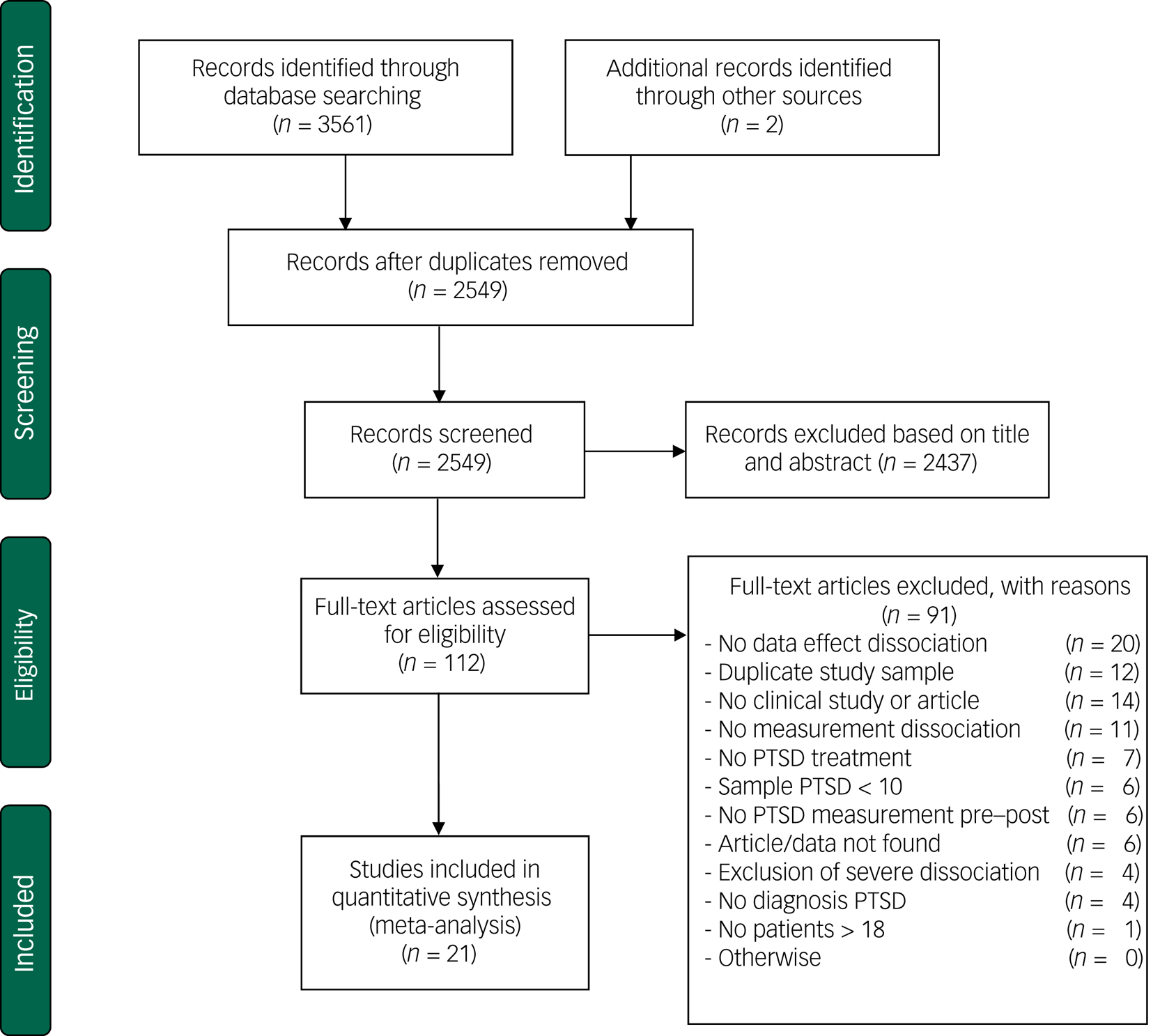

The systematic searches yielded a total of 3563 papers (2549 after removal of duplicates). Of these 2549 papers, 2437 were excluded based on title and abstract as they did not meet inclusion criteria. In total, 112 full-text papers were retrieved of which 91 were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria (see Fig. 1 for details). The remaining 21 articles were included in this meta-analysis. Note that none of the included studies used severe levels of dissociation or diagnosis of dissociative (identity) disorder as exclusion criterion.

Fig. 1 Flow chart of inclusion of studies.

Characteristics of included studies

The 21 included studies contained a total of 1714 patients from 9 RCTs and 12 uncontrolled clinical trials or treatment cohort studies.Reference Kratzer, Heinz, Schennach, Schiepek, Padberg and Jobst8,Reference Lynch, Forman, Mendelsohn and Herman9,Reference Zoet, Wagenmans, van Minnen and de Jongh13,Reference Abramowitz and Lichtenberg25–Reference Wolf, Lunney and Schnurr42 Table 1 shows the study characteristics and potential moderator variables (see supplementary Table 2 for more study details).

Table 1 Selected characteristics of studies examining the effect of dissociation on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) psychotherapy treatment outcome

NR, not reported; IES, Impact of Events Scale; DES, Dissociative Experiences Scale; DES-T, DES-taxon; RCT, randomised controlled trial; EMDR, eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing; CAPS, Clinician-Administered PTSD scale; Stair: skills training in affective and interpersonal regulation; NST, narrative story telling; ITT, intention to treat; TSI-DIS: Trauma Symptom Inventory-Dissociation; NET, narrative exposure therapy; TAU, treatment as usual; DBT, dialectical behaviour therapy; DBT-PTSD, DBT for PTSD; PSS, PTSD Symptom Scale; PITT, psychodynamic imaginative trauma therapy; PDS: Post-Traumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale; CBT, cognitive– behavioural therapy; TBE, treatment by experts of borderline disorder; CPT, cognitive processing therapy; CPT-C: cognitive therapy only; WTA, written trauma accounts only; SIC, standard inpatient care; SWT: structured writing therapy; PCT, present-centred therapy.

a. These studies provided additional data for a subsample of patients who met inclusion criteria of this meta-analysis so patient characteristics stated in this table are an estimation based on complete study sample.

Risk of bias score

The overall risk of bias of the included studies was modest (mean 6.6, s.d. = 2.94). Table 2 lists item and total scores for the risk of bias scores for each of the included studies. Agreement between two independent assessors regarding risk of bias of individual studies was high (Cohen's kappa = 0.81, s.e. = 0.04, P < 0.001).

Table 2 Risk of bias scores of included studies with higher scores indicating a higher risk of bias.

Item 1, random sequence generation; item 2, allocation concealment; item 3, selective reporting; item 4, masking of outcome assessment; item 5, incomplete outcome data; item 6, outcome measurement type; item 7, treatment integrity; item 8, other bias.

Effect of dissociation on PTSD treatment

Figure 2 depicts the main results of the meta-analysis. The pooled correlation between pre-treatment dissociation and decrease in PTSD symptoms during treatment was 0.04 (95% CI −0.04 to 0.13, P = 0.32). The heterogeneity between studies was moderately high: I² = 68.90, P < 0.001. Visual inspection of the funnel plot did not indicate asymmetry in any direction (Fig. 3), which was confirmed by Kendall's tau based on the rank correlation (P = 0.46) and by Eggers’ test (P = 0.25). The funnel plot shows two potential outliers: Harned et al (2014)Reference Harned, Korslund and Linehan32 (positive effect of dissociation) and Abramowitz & Lichtenberg (2016)Reference Abramowitz and Lichtenberg25 (negative effect). The study sample of Harned et al (2014)Reference Harned, Korslund and Linehan32 was very small and the drop-out was high. The study of Abramowitz & Lichtenberg (2016)Reference Abramowitz and Lichtenberg25 was an open study with a relatively small sample size. Therefore, both studies may have yielded an effect size that is not so reliable.

Fig. 2 Pearson's Correlation coefficient (r) between baseline dissociation and change in post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms from pre- to post-treatment.

Fig. 3 Funnel plot with Pearson's correlation coefficient between dissociation and change in post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms from pre- to post-treatment.

Effect of potential moderators of the effect of dissociation on PTSD treatment outcome

Table 3 shows the results of the moderation analyses. We did not find that a higher risk of bias resulted in a larger effect of dissociation, although this effect was borderline significant (slope r = 0.03, 95% CI −0.002 to 0.06, P = 0.07). In addition, we found no difference in the effect of dissociation on the effectiveness of completely trauma-focused treatments compared with non-trauma-focused/multicomponent treatments (P = 0.76). Similarly, we did not find that the effect of dissociation was different for randomised controlled trials compared with non-randomised studies (P = 0.18), nor did we find an effect of sample size (P = 0.38).

Table 3 Effect of dissociation on improvement in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and moderation analysesa

a. Positive correlation (Pearson's correlation) indicates negative effect of dissociation on PTSD improvement.

b. P-value indicates whether effect size of subgroups differ significantly.

To explore the effect of risk of bias on the results, we performed a post hoc analysis including only studies with a low–moderate risk of bias (i.e. risk of bias score ≤ 8 (n = 14)). The correlation between pre-treatment dissociation and decrease in PTSD symptoms during treatment for higher-quality studies was −0.01 (95% CI −0.13 to 0.10, P = 0.80) and not different from the results derived over all studies.

Discussion

Main findings

We found no evidence for a moderating effect of dissociation on psychotherapy outcome in patients with PTSD. Furthermore, differences between studies in the effect size of dissociation on treatment outcome were not explained by study characteristics. We conclude that comorbid dissociative symptoms do not reduce the effectiveness of psychotherapy in patients with PTSD. Although we did not specifically examine the dissociative subtype of PTSD, the present findings suggest that this subtype may not be associated with worse treatment outcomes as was suggested by the introduction of this subtype in the DSM-5.

Most included studies found non-significant effects of dissociation on the treatment outcome, which corresponds to the null finding of this meta-analysis. The results from the studies reported in this meta-analysis may differ from the conclusion from the individual papers. Some of these studies were hampered by methodological limitations, including incorrect moderation analyses. We assessed dissociation as a treatment moderator. Some individual studies, however, did not test moderation, but reported the association between dissociation and post-treatment PTSD severity.

We were able to include a relatively large number of recently published clinical trials. The addition of the dissociative subtype to the DSM-5 seems to have increased awareness and research into dissociation. We found a moderately high heterogeneity among studies, indicating that the effect of dissociation varied because of systematic differences rather than chance. Despite this variation, the pooled effect size allows a uniform conclusion since the error bars (95% CI) of the effect sizes of most studies include the pooled effect size.Reference Fletcher43 Moreover, we did not find indications for publication bias.

We examined whether the following study characteristics explained the heterogeneity between studies: type of treatment (exclusively trauma focused or not), risk of bias score, study design and sample size. We observed no effect of type of treatment, study design and sample size. Only a borderline significant effect of bias score was observed. The effect of dissociation on treatment outcome tended to be smaller in the higher-quality studies. No less than one-third of the studies (33%) had a low study quality score, however a post hoc analysis including only those studies with a low or moderate risk of bias again revealed no moderating effect of dissociation. We conclude that this meta-analysis provides no evidence for the idea that dissociation specifically reduces the effectiveness of trauma-focused treatment in those with PTSD.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, a meta-analysis can only be as convincing as the quality of the individual studies. In most studies, the effect size of dissociation is based on completer samples (n = 19), thereby limiting the conclusions to those patients who complete treatment. However, all included studies that reported on the effect of dissociation on treatment drop-out found that dissociation was not related to higher treatment drop-out.Reference Lynch, Forman, Mendelsohn and Herman9,Reference Bae, Kim and Park26,Reference Cloitre, Petkova, Wang and Lu27,Reference Hagenaars, van Minnen and Hoogduin30,Reference Halvorsen, Stenmark, Neuner and Nordahl31,Reference van Minnen, van der Vleugel, van den Berg, de Bont, de Roos and van der Gaag41,Reference Wolf, Lunney and Schnurr42 Cloitre and colleagues (2012) even found that patients with high dissociation were less likely to drop-out from treatment.Reference Cloitre, Petkova, Wang and Lu27 We observed quite a few studies of less than optimal quality, however, results were independent of study quality.

As we included several non-controlled clinical trials or cohort studies, we evaluated whether the effect sizes of the included treatments were comparable with previous meta-analyses of psychotherapy for PTSD. The psychotherapies of the included studies showed large within-participant effect sizes from pre- to post-treatment (Cohen's d or Hedges’ g) for treatment completers (mean 1.42) and intention-to-treat samples (mean 1.39). These effect sizes are comparable with those found in meta-analyses investigating the effectiveness of psychotherapy for PTSD as such (and including only randomised clinical trialsReference Lee, Schnitzlein, Wolf, Vythilingam, Rasmusson and Hoge44).

General limitations of the current studies in patients with PTSD are a lack of long-term follow-up measurements and the use of exclusion criteria (for example suicidality, psychosis or substance misuse), which limits the generalisability of the results. We encourage future studies to use non-restrictive in- and exclusion criteria.Reference Ronconi, Shiner and Watts45 Second, most (67% of) studies measured dissociation broadly with the Dissociative Experience Scale, which includes depersonalisation, derealisation, amnesia and absorption. Only a few studies measured the dissociative subtype (depersonalisation and derealisation) specifically (n = 5). Furthermore, a recent study indicated that broad and specific measures have a large overlap and high correlation.Reference Swart, Wildschut, Draijer, Langeland and Smit46 Future studies could focus on other instruments with a different timing of dissociation, for example within-session (state) dissociation.Reference Kleindienst, Priebe, Gorg, Dyer, Steil and Lyssenko33

Thirdly, we exclusively focused on the effect of only one moderator, that is dissociation, on treatment effects. This specific hypothesis was based on clinical experience and theoretical considerations. Possibly, a combination of patient characteristics (i.e. dissociation, depressive symptoms and functional impairment) is more predictive of treatment responsiveness.Reference Deisenhofer, Delgadillo, Rubel, Bohnke, Zimmermann and Schwartz47 Future work may consider examining combinations of moderators to detect patients who do not (fully) recover with psychotherapy and to detect differential treatment responses.Reference DeRubeis, Cohen, Forand, Fournier, Gelfand and Lorenzo-Luaces48 However, the sample sizes will need to be substantial and the risk of spurious or population-specific findings increases if research is not hypothesis-driven. Finally, we did not have the power to evaluate how moderators of the effect of dissociation interact. This could provide more insight into the effect of dissociation under specific conditions.Reference Li, Dusseldorp and Meulman49

Interpretation

Despite these limitations, the strength of our meta-analysis is that it is the first to systematically review the effect of dissociation on psychotherapy outcome in patients with PTSD across different types of psychotherapies. Psychotherapy for PTSD is generally effective but there is room for improvement since about half of the patients still meet criteria for PTSD after treatment.Reference Bradley, Greene, Russ, Dutra and Westen50 About half of clinicians believe that any degree of dissociation is a contraindication for psychotherapeutic treatment of PTSD.Reference Ronconi, Shiner and Watts45,Reference Becker, Zayfert and Anderson51 Importantly, the results of our meta-analysis contrast this supposition. We found that pre-treatment dissociation did not reduce the effectiveness of psychotherapy in patients with PTSD.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.30.

Acknowledgements

We thank Djana Nesselaar for her help with the screening of the studies and we want to thank Franka Steenhuis for her help with the systematic search terms.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to formulating the research questions and design of the study. C.M.H. carried out the study, C.M.H. and M.L.M. analysed the data and C.M.H. and R.A.D.K. wrote the first draft of the article. All authors read and approved the final version.

Funding

ZonMW (W.V.d.D., M.S., grant number 843001 705) and Innovatiefonds Zorgverzekeraars (D.A.C.O, M.S., grant number 3.180)

Declaration of interest

D.A.C.O., C.M.H., W.V.d.D. and M.S. report grants from ZonMW, grants from Innovatie fonds Zorgverzekeraars, during the conduct of the study; others authors have nothing to disclose.

ICMJE forms are in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.30.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.