The number of older people living with dementia is increasing as the population agesReference Luengo-Fernandez, Leal and Gray 1 and around 70% of those people live at home and are supported in the main by their families.Reference Schneider, Hallam, Murray, Foley, Atkin and Banerjee 2 In the middle and later stages of the illness, over 50% of people with dementia will experience agitation,Reference Ryu, Katona, Rive and Livingston 3 – Reference Mega, Cummings, Fiorello and Gornbein 5 a range of behaviours including repetitive vocalisations, verbal abuse, shouting, motor restlessness and aggression.Reference Small, Rabins, Barry, Buckholtz, DeKosky and Ferris 6 These suggest emotional distress and are a major cause of families relinquishing care and of care home admission.Reference Mega, Cummings, Fiorello and Gornbein 5 , Reference Yaffe, Fox, Newcomer, Sands, Lindquist and Dane 7 – Reference Kaufer, Cummings, Ketchel, Smith, MacMillan and Shelley 9 Agitation is associated with carer distress, and the breakdown of care is mediated by family carer distress.Reference Okura, Plassman, Steffens, Llewellyn, Potter and Langa 10 – Reference Coen, Swanwick, O'Boyle and Coakley 14 Furthermore, agitation in people with Alzheimer's disease represents a substantial monetary burden over and above the costs of health and social care associated with cognitive impairment, accounting for 12% of the costs.Reference Morris, Patel, Baio, Kelly, Lewis-Holmes and Omar 15 Trials of non-pharmacological interventions for reducing agitation in people with dementia living in domestic settings have failed, and these comprised teaching family carers behavioural management for severe agitation or cognitive–behavioural management. The former was unsuccessful immediately or in the longer term in one large randomised controlled trial of severe agitation, and inconclusive in a group with less severe symptoms. The latter was unsuccessful in two large randomised controlled trial studies of severe agitation and in one small study.Reference Livingston, Kelly, Lewis-Holmes, Baio, Morris and Patel 16 We therefore aimed to explore family members’ strategies when a family member with dementia was agitated in order to inform future interventions.

Method

This study is part of the MARQUE (Managing Agitation and Raising Quality of life) programme, funded by the ESRC/NIHR. We obtained ethics committee permission from NRES Committee London – Camberwell St Giles 15/LO/0267. Research governance permissions were obtained from National Health Service trusts. All family carers gave written informed consent.

Study design

Stage 1: Focus group

The purpose of the focus group was to refine the individual interview schedule. The Research Engagement Manager for the Alzheimer's Society recruited participants from the Alzheimer's Society Research Network. They were spouses (×3) or child (×3) family carers, and were caring or had cared for relatives with dementia and symptoms of agitation. We developed a topic outline to guide the discussion. Participants described their own experience of caring for a relative with dementia and symptoms of agitation. Additionally, they suggested topics for inclusion in the individual interview schedule and discussed the feasibility of family carers collecting data about their relative with dementia. Data from the focus groups were used to help refine the interview schedule and were not included in the thematic analysis. The feasibility of family carers collecting data was thought too burdensome, but, at their suggestion, carers were invited to make notes beforehand, if they wanted to, which they could discuss at the time of interview.

Stage 2: Individual in-depth interviews

We defined family carers as an adult family member or friend who gave unpaid support for the person with dementia and who regarded themselves as the primary carer. Participants were recruited through five memory services from London mental health trusts. We used purposive sampling to ensure maximum variation in sociodemographic characteristics: gender, ages, ethnicity, relationships (spouses, children, others) and living arrangements (i.e. either living together or in separate households).Reference Bryman 17 We stopped recruiting new participants when we were unable to find any new ideas or perspectives (theoretical saturation).

Initially, memory service clinicians approached family carers of people with dementia and symptoms of agitation, providing an information sheet to those interested in the study. Following contact and informed consent, we arranged individual interviews in participants’ homes or in a preferred location. We used a semi-structured interview guide with open-ended questions (see Data supplement) and audio-recorded interviews. We asked carers to talk about their experiences and explored the agitation (type, severity, duration, provocation factors and reaction) and the effectiveness of strategies used. In addition, we enquired about biographical details of the person with dementia and the carer, family milieu and culture, current circumstances and support networks (paid and family).

Analysis

We transcribed the interviews verbatim, checked for accuracy and anonymised them. We sent each participant their transcript to verify that it was a true record. We used NVivo 18 to assist coding, management and analysis of data. We used a thematic content analytic approachReference Braun and Clarke 19 to identify emerging themes and label them with codes. Two researchers cross-coded all data independently to ensure reliability.Reference Smith 20 The coding framework included themes that reflected the questions we had asked in the interviews and emergent themes that we identified in transcripts. We held frequent thematic discussions to review the coding, consider emergent themes and evaluate second-level interpretations. Any coding discrepancies were discussed until we reached consensus.

Results

Demographic data

We interviewed 18/31 family carers (FCs) who expressed interest in taking part in the study when approached by memory clinic staff. All were caring for a relative with dementia and symptoms of agitation. Of those not included, one carer did not fulfil the inclusion criteria as they were a paid caregiver, three carers were too busy, three were unreachable by the researchers, one was unavailable because of legal safeguarding issues and one decided not to participate without giving a reason. An additional four carers were not interviewed, as recruitment finished when theoretical saturation was reached.

Sixteen family carers were currently caring for people with dementia living at home and two were recently bereaved, but their relative with dementia had lived at home (see Table 1). The median age of carers was 70 (range 51–77) years. Most (N=13) were living with their relative. The people with dementia had a median age of 83 (range 61–94) years.

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

| Focus group participants N (%) | Individual interviewees N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 3 (50) | 11 (61) |

| Relationship to person with dementia | Wife | 1 (17) | 6 (33) |

| Husband | 2 (33) | 5 (28) | |

| Daughter | 2 (33) | 3 (17) | |

| Son | 1 (17) | 2 (11) | |

| Daughter-in-law | 0 | 1 (6) | |

| Sister | 0 | 1 (6) | |

| Living together | Yes | 2 (33) | 13 (72) |

| No | 4 (67) | 5 (28) | |

| Caring role | Current carer | 3 (50) | 16 (89) |

| Former carer | 3 (50) | 2 (11) | |

| Length of time caring (years) | 0–1 | 0 | 2 (11) |

| 1–3 | 2 (33) | 6 (33) | |

| 3–5 | 0 | 4 (22) | |

| 5–10 | 0 | 4 (22) | |

| 10+ | 4 (67) | 2 (11) | |

| Carer occupation | Retired | 4 (67) | 10 (55) |

| In paid work/studying | 2 (33) | 5 (28) | |

| Not in paid work | 0 | 3 (17) | |

| Highest level of education | Primary | 0 | 1 (6) |

| Secondary | 0 | 11 (61) | |

| Post-secondary | 6 (100) | 6 (33) | |

| Ethnicity | White (British, Irish, Other White) | 5 (83) | 14 (78) |

| Black (British, Caribbean, African, Other Black) | 0 | 3 (17) | |

| Asian (British, Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Myanmar) | 1 (17) | 1 (6) |

Types of agitated behaviour and responses to frequency, severity and unpredictability

We found that carers reported a range of agitated behaviours and many had continued to manage despite frequent, severe or unpredictable agitation. The most commonly described agitated behaviours were repetitive behaviours, which included repetitive speech, repeatedly handling things and wandering. This was followed by verbal aggression, which included swearing and making verbal threats, shouting, screaming and belligerence. Less common were acts of physical aggression, which included hitting people, hitting objects, attempted strangulation, throwing objects and inadvertent self-harm.

People described their distress in coping with increasing severity, frequency and unpredictability of agitated behaviour. Although some behaviours were not dangerous, family carers often had to intervene to calm things, such as during the delivery of personal care:

…she has to have a hoist… She's very abusive [swearing] when they [home carers] try to put that on and… nine times out of ten I have to intervene. (Husband FC3)

More frequent behaviours tended to be less severe, but were difficult to live with and sometimes to understand:

…the shouting. I couldn't understand some of the words he was saying, and I used to keep running down and checking…thinking he was calling me or something was wrong. (Wife FC10)

More serious physical and verbally aggressive behaviours, although infrequent, could be terrifying:

He always gets me by the throat. And… and I think one of these days is he going to get me by the throat and finish me off, you know. (Wife FC12)

At times, carers found it very difficult to cope. Agitation at night was a particular problem as it disrupted the carer's sleep too:

…he's awake in the night more… There was one point where I could barely get him to bed before four. (Wife FC6)

Most people described times when they felt unable to cope, sometimes because of the impact on their health:

All I was worried about, you know, was that I was going to get the colitis back … I have to walk away and have a good cry… I thought, I can't cope with this. I'm going to end up in hospital again… (Wife FC7)

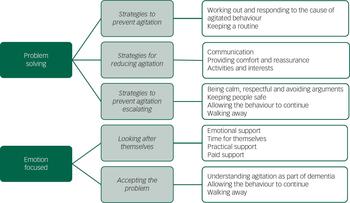

Overall approaches to caring

Carers felt that it took time for them to accept that agitation was part of the dementia (see Table 2 for carers’ examples and comments). The gradual realisation that agitation was part of dementia rather than being wilful or provocative helped people come to terms with such behaviours. Commonly, participants attributed agitated behaviours to underlying emotions (anger, anxiety and sadness) or changes because of dementia (irritability and disinhibition). Knowing that other families had similar experiences also helped reassure carers that it was not an internal family problem. Carers developed flexibility in their approach and an increasing appreciation that effective responses tend to be time and context specific, and they sought to determine possible causes in order to manage it more effectively. This led carers to try to find meaning in the behaviour. They sought multiple sources of information and valued sharing their experiences with other people in the same situation, searching for patterns in behaviour and concluding that agitation often arose from their relative needing or wanting something. Several strategies (Fig. 1) were suggested, and successful strategies can broadly be divided into problem-solving and emotion-focused coping.Reference Li, Cooper, Bradley, Shulman and Livingston 21 , Reference Li, Cooper, Austin and Livingston 22 Although some relatives used dysfunctional strategies, these were rare.

Table 2 Caring for a relative with agitated behaviour

| Strategy | Carer's comments |

|---|---|

| Working out and responding to the cause of agitated behaviour | ‘If he's hungry … and throwing a tantrum, I… put food on the table, and I get my kids… to start eating. And then he realises, oh it's time for me to eat, maybe that's why I'm upset’. (Daughter-in-law FC5) |

| Keeping a routine | ‘… and I realised that I shouldn't [take him on holiday] anymore, he was writing me notes saying please, please, please will you take me home’ (Wife FC6) |

| Being calm, respectful and avoiding arguments | ‘It is very hard because you get really stressed out… it… gets you emotional, then you react emotionally… and it could escalate’. (Daughter FC14) |

| ‘…my advice would be to be calm, if they can…’ (Husband FC13) | |

| Keeping people safe | ‘But I've got an alarm fitted, so that if she calls, which she does, not every night but quite often, I… go down, what's the matter’. (Husband FC3) |

| Allowing the behaviour to continue | ‘…let him rummage… it keeps him quiet and he feels as if he's doing something…’ (Wife FC12) |

| Walking away | ‘I was getting upset, he was getting more agitated. So that's when I started to walk away’. (Wife FC7) |

| Communication | ‘…one of the things that I do when he's got caught in something, I try and get him to look at me and… then I can, sort of, pull him… away from what he's doing on the table or something’. (Wife FC6) |

| Providing comfort and reassurance | ‘She's quite difficult to reassure… we've tried so many different things, but I think it's… just time, and just calm, and just holding her hand, and just almost not even replying to some of her agitation and anxiety’. (Son FC2) |

| Activities and interests | ‘She loves them [puzzle] books. She'll sit there for hours. That is one blessing… my friends all buy her books…’ (Husband FC11) |

| ‘He loves his music… His favourite piece of music is The Marriage of Figaro… he will listen to it and it seems to be a calming factor’. (Wife FC16) |

Fig. 1 Strategies for coping with agitation in dementia.

Problem-solving

Problem-solving refers to the carer's ability to solve or change the agitation. Carers reduced agitated behaviour by introducing routine to prevent uncertainty which led to agitation. In addition, carers averted agitation by considering and addressing triggers to agitation and engaging people in activities that provided occupation and distraction from these triggers.

I'll start reading to my kids… he'll try and see what I'm reading… I'll say, oh dad do you want to join in? Come on let's, let's read together. (Daughter-in-law FC5)

How carers responded to repetitive behaviours, such as wandering and repeatedly handling things, was particularly significant, as this could lead to a reduction or escalation of agitation. They emphasised being calm, respectful and avoiding conflict as ways of preventing the agitation escalating. Trying to stop the behaviour often provoked conflict. Some people found that letting their relative continue with the behaviour was the better approach, if it was safe to do so, monitoring their safety all the while.

…wasn't anything I could do to calm her down other than… let her go… So, in the end I would… get dressed and let her go, and I would follow her. (Son FC17)

Strategies to prevent agitation

The importance of establishing a routine to avoid agitation was described by several participants. Thus, maintaining active routines within the home and local community provided reassurance and focused activity for their relative and helped dispel boredom.

All his life he's been busy… had a routine. Work, pray, Koran…he wants things to do. … I think that's the key…giving them a routine. (Daughter-in-law FC5)

Strategies for reducing agitation

Carers described various responses to their relatives’ agitation. Clear communication was crucial. This included focusing the attention of the person with dementia, observing non-verbal cues and repeating things if needed. Sometimes, simplifying the language helped clarify meaning, to ensure the person with dementia could understand.

If… he doesn't understand what I'm saying. He will get agitated… so I… think about explaining it in a different way… It calmed him down… (Wife FC12)

When a relative was particularly agitated and distressed, the use of reassuring touch such as holding hands or putting their arms around the person was often effective at reducing agitation. Showing concern and offering affection were also helpful for reducing agitation, even when the cause of distress was unknown.

Sometimes I'll go in and she'll… ‘can I have a hug, I need a hug’, and I'll say, oh, what's the matter, Mum, what are you feeling down about? ‘I don't know. I did know, but I don't know, I can't remember’… (Daughter FC1)

Carers tried to respond to the underlying cause, including hunger, boredom, worry or pain.

We had the power cut… and it was total silence… he was getting really agitated and he went, turn the music, put the telly on… and what I've done is, got the radio out. He was all calm; so it proved to me that silence was no good for him… (Wife FC10)

Finding activities that the person with dementia enjoyed doing, including new interests and previous hobbies, was helpful both for avoiding agitation and as a distraction when agitated. Activities such as gardening, walking, listening to music, watching television or doing crosswords and puzzle books were popular. Several carers used such activities to maintain relationships with the person with dementia or construct new relationships within the family, particularly with younger children.

Strategies to prevent agitation escalating

Carers described learning how best to respond to their relative when they became agitated. Participants highlighted the need to keep calm and respectful and avoid confrontation by not arguing or correcting.

Now I just completely ignore what she's done, and… walk her back into the front room and… get on with cleaning it up. She doesn't feel as though she's constantly being told off, or… being picked on. (Son FC17)

Challenging their relative or becoming irritated generally led to an escalation of the agitation.

At first, I tried to reason. I've now learnt, shut your mouth, because there's no point in reasoning; if it's not harming her, let her think it. (Daughter FC1)

Making adaptations to the environment helped to maintain both the carers’ and their relative's independence and safety. A few people reported various means of knowing when their relative was leaving the house (e.g. door alarm/squeaky gate) or became distressed at night (e.g. by using a monitor). This allowed them to respond to their relative's agitated behaviour quickly without having to be present all the time. One carer described how a noticeboard saying where she was and when she would return helped reduce her husband's agitation while she was out.

If I want to open the front door, I can switch the alarm off, if I want it on when she's going to go walkabouts… (Husband FC8)

Emotion focused

This refers to the carer's ability to accept and manage the intensity of their negative emotions rather than change the situation. Sometimes, the carers accepted that they could not change the agitation but protected themselves from the experience and their relative from harm or injury. This was shown by carers allowing the person to continue agitated behaviour if they were safe, but walking away, leaving themselves physically and emotionally safe. They also decided that some level of risk was preferable to safer, but potentially upsetting, restrictions.

Many a time she'll go out without even saying… The only blessing is the fact that she knows the area… and she always finds her way back. (Husband FC11)

This was considered too dangerous when the dementia became more advanced, but further restriction of their relative's freedom was likely to exacerbate the agitation.

…she was always trying to get out, and when I took to locking the front door, she started banging on windows, and… the door and kicking the door and screaming, and neighbours used to call the police… (Son FC17)

Participants commonly reported that some agitated behaviour was exceptionally hard to manage, and the best way to avoid escalation of agitation was to walk away, allowing time to defuse the situation. This was essential if their relative was becoming physically aggressive and the carer felt in danger.

…he lifted his hand up, it felt like he was going to hit someone… I told everyone to get out the room, and… let him calm down. (Daughter-in-law FC5)

Looking after themselves

Table 3 gives quotes from family members who regulated their emotional responses by accepting emotional support from others.

Table 3 Looking after themselves

| Strategy | Carer's comment |

|---|---|

| Emotional support | ‘I think it's just talking and, we're all in the same boat’. (Wife FC12) |

| ‘There were times when I was finding it very difficult… my wife really helped out, my friends… just offloading… helps, it's all good’. (Son FC2) | |

| ‘Go and get help earlier’. (Wife FC7) | |

| Time for themselves | ‘It is a strain, it is a strain because I can't go off and do things… I'd like to… take my dogs for walk and things like that… I love walking… but I can't do that now because he's forever calling, or if he cannot hear me…’ (Wife FC10) |

| ‘… I keep telling myself I've get to get out, some time out because I think it will be better for [wife] because… you get a bit bad-tempered’. (Husband FC3) | |

| ‘I do write a lot, I like poetry. I write my poetry. For me, that's an avenue’ (Wife FC16) | |

| ‘…I pray a lot and ask God to help me, not to solve the problem but to cope with the problem because I can't solve the problem, you've got to cope with it’. (Husband FC18) | |

| Practical support | ‘…it is good, because it gets her out of the house… it's every other Saturday… My son [takes her] one session my daughter the next session, to give me a break. Family do get involved’. (Husband FC18) |

| ‘It gives everyone a break… that's the best thing… take it in turns. Like when I needed the help, they were there’. (Daughter-in-law FC3) | |

| Paid support | ‘… the carers that come in, when I couldn't… because to give him a bath, and like that, I just drew the line’. (Sister FC15) |

| ‘…he doesn't get agitated that often. And I think it's because we've got a very good routine with him and I've got very good carers and myself. So… he says he's happy… the carers are very intuitive sort of people and very natural with him’. (Wife FC6) |

Talk; the biggest advice: talk. Get what's in your head out. Find someone… someone to talk to, cry to, whatever, because it's a very lonely world, being a carer – very lonely… (Daughter FC1)

People felt better if they were able to have time away doing things they enjoyed like walking or writing and were able to tell themselves correctly that it made them better carers as they were calm.

Just to go swimming because I love swimming… Just something simple as that, without having to worry to rush back because he's indoors, or because I haven't been able to get somebody to sit with him… that's all it is. (Wife FC10)

Carers found that taking time for themselves was often difficult because of the demands placed on them by their relative's agitation. The acceptance of emotional and practical support from family, friends or services was essential to continue managing.

What I really do get a lot out of is when I've just dropped her off at the day care centre, I buy the paper and have a coffee and do the crossword. (Son FC17)

Sometimes, other relatives were more able to calm things down. However, some people were reluctant to seek family support, particularly when they perceived other members of the family as having competing responsibilities.

Table 4 Agitation and professional support

| Difficulty | Carer's comments |

|---|---|

| Feeling abandoned | ‘I was rather down-hearted when the Memory Clinic said, we've diagnosed him now…. I mean, they were terribly nice… but they kind of realised that they were dumping us once there had been a diagnosis’. (Daughter FC4) |

| Knowing what help is available | ‘If someone was to talk to me about this sort of stuff, it would have really helped, back then… I've learned it the hard way, whereas if someone told me… if he gets agitated try this, try that’. (Daughter-in-law FC5) |

| Barriers to seeking professional help | ‘You just get on with things, that's what people of my generation do… You don't know where to go for help’. (Wife FC9) |

| Time taken to receive support | ‘…really all I needed, was just somebody to help… I asked for this in January, the social worker came in April… I need somebody now, not for you to decide in a week's time whether you've got somebody… I got a little bit irate…’ (Wife FC9) |

| Home and hospital care | ‘…they had totally unrealistic expectations… they failed to… recognise that they had to look at his physical condition… in the context of him being an old man with dementia’. (Daughter FC4) |

| ‘…she gets really angry if… they talk in their own language [homecarers] …she thinks they're talking about her’ (Husband FC3) | |

| ‘…I mean the carers are, we've got… very lucky, a brilliant agency, brilliant management and the carers are… lovely’. (Son FC2) | |

| ‘The doctor at the Memory Clinic was excellent, very sympathetic’. (Daughter FC4) ‘…the admiral nurse that comes round, very helpful he is, very, very helpful, you know’. (Wife FC10) |

Table 4 shows the varying experiences of professional support. Many people felt it would have helped to be told that agitation was a likely symptom of dementia.

Yes, floundering to find your way through things, and nobody says, look, you could have this, this is available. (Daughter FC1)

Where family carers had positive experiences of services, they often described the help received as being essential to being able to continue with caring. Some would have liked to know where to go for help, although others found it difficult to ask for or accept help, or thought their relative would not want it. Commonly, people were disinclined to accept additional support, as they were unsure about its benefits or felt that they had a duty to provide the care themselves.

…the way I look at it is, what can people do that I'm not doing? (Husband FC11)

Others were anxious that their relative would feel embarrassed or reject help.

…obviously nobody wants a stranger washing, dealing with you… she was worried they would be foreign… she's not racist, it's the accent. She's hard of hearing, so if you speak with an accent, it's… very hard to understand. (Daughter FC1)

Where carers received specialist, timely and appropriate support, they often found this invaluable, both in terms of receiving emotional support and putting practical resources in place. In addition to practical help, family carers appreciated the extra time and flexibility it gave them to pursue their own interests.

I was able to not entirely abandon the rest of my life but be responsive enough for him, which, again, is partly to do with being able to ring up the agency and say, there's no one going in on Friday night, please can you send someone in. (Daughter FC4)

Discussion

Main findings

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to ask carers specifically about caring for a relative with dementia and agitation at home. We found that family carers experienced significant levels of agitated behaviour and, at least initially, felt unprepared for this and unaware that agitation was part of dementia. Once they had learned this, they employed varying and flexible strategies, and those we interviewed, atypically, continued to care for their relative at home.

Carers learnt to deal with the agitation by accepting it was part of dementia. They sought out ways to prevent agitation by, for example, using a calendar and supporting their relative to have an active routine. When agitation occurred, they tried to reduce it by working out and addressing the underlying cause. They also attempted to prevent it from escalating by consciously being respectful and avoiding arguments. If it continued, they ensured their family member and other people were safe and worked on managing their own emotions. Overall, offering comfort and reassurance, being non-confrontational and seeking to maintain the person with dementia's dignity were key in both prevention and de-escalation of agitation. Carers also kept themselves emotionally and physically safe by leaving their relative alone, after ensuring they were safe, and walking away from volatile situations.

Carers recognised the need to look after themselves, but needed support from family, friends and professionals for respite and to reduce isolation. Sometimes, carers did not know how to access professional support or waited a long time for services to respond. Carers judged that good professional support helped them to cope longer with supporting their relative at home.

Behaviours such as physical aggression were often unpredictable and frightening, but non-threatening repetitive behaviours such as wandering, shouting out and repeatedly handling things were frequent and also hard to cope with. Although some carers expressed sadness at this, others found that caring brought them and their relative closer together. Overall, they were flexible in their approach, finding different tactics worked at different times. By seeking to better understand agitation and adapting their approach, carers became very skilled at dealing with agitated behaviour.

Our findings are consistent with but add to the previous literature, which found that it is important that family carers understand agitation as part of dementia, as otherwise this undermines their ability to careReference Feast, Orrell, Charlesworth, Melunsky, Poland and Moniz-Cook 23 and leads to a decline in the quality of interaction and feelings of loneliness. The strategies suggested are different approaches to the previous unsuccessful trials at home.Reference Livingston, Kelly, Lewis-Holmes, Baio, Morris and Patel 16 We note that a third of carers in an earlier study reported feelings of aggression in response to aggressive behaviour and about a fifth had responded aggressively to the person for whom they cared,Reference Ryden 24 further highlighting the need to communicate effective strategies for coping with agitation to family carers.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

Although our participant carers came from a range of socio-demographic backgrounds, they were all London area residents; none lived far away from any services. The study was about people caring for someone in their own homes in order to find out what works and so we did not interview carers of people with dementia and agitation recently placed in care homes. Although it may be that the agitated behaviour these carers encountered was more challenging, many of our carers were coping with high frequency and severity of agitation. Several of our carers had considered care home placement, when they found the agitated behaviours particularly hard to cope with, but had not pursued this option. These carers wanted to care for their relative at home, but recognised that care home placement might be necessary in the future if the agitation became too difficult to manage.

Further research

Overall, family carers devised, learned and implemented effective strategies to reduce or avoid agitated behaviour, and this enabled them to continue caring for their relative at home for longer. These interviews provide valuable information on potentially helpful components for the intervention that we seek to develop and test. In addition, support from specialist services and voluntary agencies was a key factor in family carers feeling able to cope for longer. Policy makers and commissioners should be aware that family carers of those with more moderate to severe stages of dementia need to know that agitation is part of the illness and may need help when it occurs. Although our study suggests there are successful ways to manage when people with dementia are agitated at home, it is important that these strategies are tested in a randomised controlled trial. Future research should also take into account carers’ different cultural and religious backgrounds.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the family carers who participated in the study together with all the memory services who provided us with support and help with recruitment.

Funding

ESRC/NIHR Grant Ref: ES/L001780/1. This is a independent research commissioned by ESRC/NIHR ES/L001780/1. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR, ESRC, NHS or the Department of Health. The studies are sponsored by UCL. Neither funders nor sponsors had a role in the study design and the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and the writing of articles.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.