1 Introduction

National economies that have been held up as exemplars of Western capitalism in the past, particularly the UK, are struggling. Alongside a general slowdown in economic growth, the growing polarisation in these advanced economies, between the beneficiaries of these forms of capitalism and disadvantaged communities that are being ‘left behind’, provides convincing evidence that we need to reinvent capitalism. Recent economic and political shocks have further revealed and worsened these trends, suggesting that ‘older’ varieties of capitalism are failing to adapt to a new and different global environment. Geopolitical disruption is arguably another symptom of underlying income inequalities. Political elites claim to be supporting deprived communities, focusing on short-term, popularist agendas, but wealth and health inequalities grow.

As a contribution to the ‘Reinventing Capitalism’ Elements Series, this Element will focus on the failure in the UK capitalist system to manage balanced growth across the economy. It is characterised by highly uneven regional growth rates, with city-regions experiencing persistent low productivity, alongside rising socio-economic inequalities. These in turn underlie disparities in health and welfare across the population, which contribute to the low-growth cycle. Some of the symptoms, the causes and potential solutions to these problems extend beyond the UK example to other advanced liberal democracies, so this Element has a wider relevance to other varieties of capitalism. Slower growth in Europe, particularly in Germany, and very high levels of inequality despite more robust growth in the United States, underpin the rationale for our focus.

Policy interventions to stimulate national and local economic growth, in the UK and elsewhere, have been focused too exclusively on high-growth regions, using current productivity and return-on-investment indicators as the preconditions for further investment and to guide regulation. These performance metrics are also applied in strategies to promote inward foreign direct investment (FDI) and the wider participation of multinational firms in global value chains. Something that has become much more difficult since Brexit, as foreign firms are more attracted to investing in mainland Europe.

This has helped drive the growing polarisation between high-growth and low-growth regions and widening disparities in household incomes and living standards. Such policies are an important focal point because they bridge the public principles and narratives of government with the realities of on-the-ground investments and interventions. These, in turn, shape business investment conditions, and the opportunities open to local communities. They set priorities and privilege one project, place or interest group above others. At the same time, in the UK system, they sit within a wider governance apparatus shaped and managed by a relatively small, centralised group of decision-makers at the heart of the fiscal infrastructure, which directs public spending.

Some of these selection mechanisms and performance metrics that govern public and private resource allocation in these capitalist systems may well be effective in the short term, but they are creating longer-term problems that are undermining the entire system. Long-run productivity in regions outside of London and the South-East of the UK is significantly below expected levels, and low compared with equivalent regions in Europe. A variety of other inequalities, in transport infrastructure, education and skills, household income, and levels of deprivation, health and welfare, match this spatial distribution, as the government fails to address these imbalances or ‘level up’ the UK economy. This contribution to the Elements Series argues that even if the dominant political agenda supported fundamental reform, the structural mechanisms and governance infrastructures that make up the UK capitalist system are not fit for purpose.

We summarise some of the work conducted at City-REDI, the City-Region Economic Development Institute at the University of Birmingham, to illustrate some of the challenges and solutions. It has a remit to produce the evidence needed to demonstrate how different structural mechanisms, more precise policy interventions and a greater degree of devolution or localisation would be better suited to driving balanced growth (Riley et al., Reference Riley, Collinson, Green, Ortega-Argiles, Vorley, Rahman, Tuckerman and Wallace2022). This requires interdisciplinary analytical approaches for a more holistic understanding of city-regions and the trade-offs between economic growth, social, health and welfare inequalities and the challenges of meeting net-zero targets in complex economic systems. It also requires new methods and tools to evaluate different policy approaches in the context of different places with different challenges and growth opportunities.

Coalitions of local stakeholders should lead new types of interventions with the support of central government, rather than the current system. These have a deeper understanding of local growth opportunities and challenges, and where the consensus lies regarding key priorities. They can also co-opt local organisations that are capable of co-delivering policies and engaging a wider range of local constituencies. This change would help improve the incentives and mechanisms that underlie local inclusive economic growth by more directly connecting the organisations whose role it is to intervene and those communities that would benefit from this improvement. This is a critical component of the reinvention of the UK-type of capitalist system we focus on here.

This contribution to the CUP Elements Series is timely given the impacts of a series of economic shocks on disadvantaged regions in the UK, and the state of UK government. Brexit, COVID-19, the Ukraine war and the emergence of a multi-polar world and trade blocks have revealed structural weaknesses in the UK and other capitalist systems. These are exacerbated by short-term decision-making and self-interested governance. None of the mainstream political parties are able to propose and deliver a broad national direction to galvanise the UK around major national goals. Signs of societal, political and ideological fragmentation, evident in the US, are growing in the UK.

In the following, we briefly review and summarise the empirical evidence that tells us that the capitalist model in the UK is failing (Section 2) and outline the key causes underlying the regional polarisation of wealth and opportunity (Section 3). We then outline how intelligent interventions require better evidence and analysis of how to stimulate local growth opportunities (Section 4) and provide some recommendations for reinventing this model (Section 5), before concluding (Section 6). The work of City-REDI, which has helped reveal some of the symptoms, causes and effects, features throughout. It has also highlighted the scale and seriousness of the challenge.

2 The Signs of Failure

The UK has experienced a significant slowdown in economic growth and lower average levels of productivity, particularly in the last fifteen years. This has evolved alongside, and is directly related to, a significant polarisation between regions that are more productive and create wealth, and those that are less productive, less wealthy and more deprived. For these ‘left behind’ regions, a simple logic chain goes something like this. They attract lower levels of private investment and are awarded lower levels of public investment. Highly skilled workers are not attracted to the region and/or do not stay in the region. Lower levels of per capita productivity are compounded by periods of rapid deindustrialisation and unemployment as these regions transition away from legacy industries (particularly mining and manufacturing), as described in Section 3 (see the data presented by Stansbury et al., Reference Stansbury, Turner and Balls2023). Weakening regional innovation systems (RIS) are less resilient and adaptive to external shocks or changing economic challenges. Lower skill levels, or the ‘wrong skills’, increase unemployment and drive down household incomes. This increases deprivation and a dependency on social benefits, lowering health outcomes, pushing up crime levels and overloading public services. The combination of economic and social challenges in such regions makes them much less resilient in the face of economic shocks (more recently, Brexit, COVID-19 and the Ukraine war) widening the gap with regions (particularly London and the South-East) that are more productive and less deprived (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Gardiner, Pike, Sunley and Tyler2021; Sensier et al., Reference Sensier, Rafferty and Devine2023). Failure, by central and regional governments, to attract foreign investment or compete as a location for high-end activities within global value chains as effectively as in the past has exacerbated these challenges. This sits alongside a weakened entrepreneurial culture, relative to many US states, and smaller economies such as Singapore, Israel or Switzerland.

This (simplified) path-dependent cycle of slow growth, no growth or decline in specific regions reflects not just the economic drivers of unfettered capitalist markets, but also the forms of government intervention in play. Government agencies direct public investment and influence private-sector investment to benefit particular places and socio-economic groups and not others. Rather than ‘levelling up’ or re-balancing the economy and reducing inequalities, government intervention appears to be having a neutral or even negative impact.

UK regional and urban divides have grown significantly over the last four decades (Carrascal-Incera et al., Reference Carrascal-Incera, McCann, Ortega-Argilés and Rodríguez-Pose2020; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Sunley, Gardiner, Evenhuis and Tyler2018; McCann, Reference McCann2016, Reference McCann2020). Both wealth and the capacity to create wealth are increasingly concentrated spatially in the UK, and in the USA (Kemeny and Storper, Reference Kemeny and Storper2023), with some of the same factors that drive differences between national economies driving these regional variations. The economic conditions for growth and for attracting companies, whose success depends on high skilled, high-income workers, are affected by differences in the social, political, legal and institutional contexts across different geographies. Moreover, the polarisation of wealth is mirrored by growing interregional disparities, in household income, skills and knowledge, occupational mobility, health and welfare, as well as in productivity (gross value added (GVA) per capita).

2.1 Productivity

There is general acknowledgement that advanced economies have experienced a slowdown in labour productivity growth since the 2010s, linked to lower (or negative) total factor productivity growth and lower growth in capital per worker hour. The larger, emerging economies, including China and India, are not only growing but also experiencing some of these effects (van Ark et al., Reference van Ark, de Vries and Pilat2024).

In terms of economic performance, from 2010 to 2022, the annual average growth in UK GDP per hour was 0.5%. Labour input growth (total hours worked) is projected to slow to 0.3% per year between 2023 and 2035. Relative to its Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) comparators, the UK economy is suffering from persistently low average productivity levels. Failure to increase average productivity growth from 2012–2022 levels would mean that GDP growth from 2023–2035 would be limited to 0.8% per year. To achieve the same GDP growth rate in 2023–2035 as the UK experienced in 1996–2006 would require productivity growth to be raised to 2.2% per year (Coyle et al., Reference Coyle, van Ark and Pendrill2023, quoting data from the Office for National Statistics).

Average growth levels are constrained by very low productivity in regions outside of London and the South-East of England – a pattern that has emerged in recent decades. Carrascal-Incera et al. (Reference Carrascal-Incera, McCann, Ortega-Argilés and Rodríguez-Pose2020) apply a spatial Theil Index to plot the long-run evolution of interregional inequality in GDP per capita across European countries (1900–2010) and point to a U-shaped trend. The UK shows small levels of variation in interregional productivity for nine decades, until 1990 when the growing divergence between regions sets it apart from other countries. By 2010, the UK shows very high interregional differences by international standards. Specifically, the trend lines from 2000 to 2016 show Germany converging and the UK diverging.

Additional data comes from a report for the Industrial Strategy Council in the UK (Zymek and Jones, Reference Zymek and Jones2020) showing that the most productive region (West Inner London, one of the wealthiest boroughs) was 70% higher than Northumberland in terms of income per hour. The least productive region, Cornwall in the South-West, was 25% lower than Northumberland. Only eleven out of forty-one NUTS2 regions have productivity higher than the UK average because a small number of high-productivity regions skew the average productivity statistics. The gap between the UK regions with the highest and lowest productivity is bigger than the equivalent gaps in Germany, France, Italy and Spain. But it is the case that regional divergence is occurring in a wider range of countries, just to a lesser extent than in the UK (Gómez-Tello, Murgui-García and Sanchis-Llopis, Reference 51Gómez-Tello, Murgui-García and Sanchis-Llopis2020). Education and skills, alongside the state of RIS, are part of the underlying dynamics of this weakness.

2.2 Education and Skills

Education and skills have a significant impact on firm-level productivity and performance, which underpins economic growth and wealth creation at the regional level. The share of the population with a tertiary education correlates significantly with regional productivity, as does the share with a secondary qualification (Coyle, et al., Reference Coyle, van Ark and Pendrill2023). Some studies suggest that this correlation can explain ‘mechanically’ much of the average income differences between regions (Overman and Xu, Reference Overman and Xu2022).

But education and skills also represent a critical link, via employment and salaries, to household income, which determines relative levels of deprivation, socio-economic equality and community resilience. Inequalities in education attainment levels and skills by region contribute to regional differences in wealth creation, income distribution and household deprivation across the UK (and most economies).

The UK generally has seen investment in education decline, with spending as a share of national income falling from 5.6% in 2010–2011 to 4.4% in 2022–2023 (Drayton et al., Reference Drayton, Farquharson and Ogden2024). Total adult skills spending in 2024–2025 is expected to be 23% below 2009–2010 levels. 33.8%, or 16.4 million people aged sixteen years and over in England and Wales had Level 4 or higher-level qualifications, including Higher National Certificate, Higher National Diploma, Bachelor’s degree or post-graduate qualifications in 2021. 18.2% (8.8 million) are reported as having no qualifications. London, with 46.7% (3.3 million), has the highest percentage of the population in the UK with Level 4 or above qualifications. Moreover, this unequal distribution and the socio-economic inequalities in education and skills generally, have worsened since the COVID-19 pandemic (Blundell et al., Reference Blundell, Costa Dias, Joyce and Xu2020).

When we focus on the later stages of pre-employment education, the share of eighteen-year-olds who are ‘not in education, employment or training’ (known as NEETs) reached 16% in 2022, close to the levels seen in economic recession of the late 2000s. Around a third of young people have completed all of their education by the age of eighteen, compared to 20% in France and Germany (Thwaites and Try, Reference Thwaites and Try2023). Blundell et al. (Reference Blundell, Cribb, McNally, Warwick and Xu2021) also describe big differences in the proportion of people with or without post A-level qualifications across the country. In many places, less than a quarter of the population have post A-level qualifications, but in large parts of London, the South and South-East of England, almost half of the people have a post A-level education.

Some commentary notes that disadvantaged areas receive higher levels of spending for students in further education (FE) colleges, up to 9% higher in the most deprived areas than in the wealthiest areas. However, these account for 5% of UK students. For the other 95% in higher education (HE) funding is unequally distributed and favours wealthier regions. In terms of the area that students come from, HE-spending per young person is highest in London (£15,800) and lowest in Northamptonshire (£5,800) and Blackpool (£6,250) (Drayton et al., Reference Drayton, Farquharson and Ogden2024). This is due to spatial differences in university participation rates, with young people from wealthier areas more likely to attend higher education.

The distribution of education levels relates to other kinds of inequality. This includes wages and wider measures of deprivation. A slightly dated but very robust study by Gibbons et al. (Reference Gibbons, Overman and Pelkonen2013) found that 90% of the differences in area-level wages can be explained by differences in the dispersion of highly skilled workers. Similarly, Davenport and Zaranko (Reference Davenport, Zaranko, Bourquin, Johnson and Smith2020) use four variables to generate a ‘left behind’ index and find that the ‘share of individuals with a degree’ is more unequally dispersed than ‘incapacity benefit claimants’, ‘employment’ and ‘wage levels’, but all are related. Agrawal and Philips (Reference Agrawal and Phillips2020) draw on UK Department for Education data to link the percentage of young people going to higher education by region and Free School Meal status, which is used as a proxy measure of deprivation by many studies.

2.3 Regional Innovation Systems

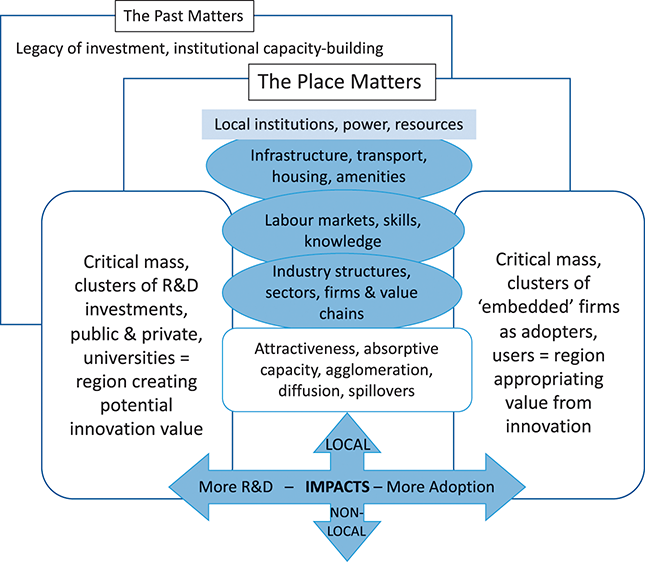

Skills and productivity are strongly connected to RIS and agglomerations or clusters of economic growth. Strong RIS provide resilience and adaptability in the face of external shocks as well as underpinning high-productivity economic activities in sectors such as automotive and aerospace manufacturing, pharmaceuticals and software development. There is a strong consensus that research and development (R&D) activity boosts general productivity in regions (Aitken et al., Reference Aitken, Foliano and Mariona2021; Coyle et al., Reference Coyle, van Ark and Pendrill2023; Griffith et al., Reference Griffith, Huergo, Mairesse and Peters2006) and that public R&D investments ‘crowd-in’ private investment (Aitken et al., Reference Aitken, Foliano and Mariona2021; Moretti et al., Reference Moretti, Steinwender and Van Reenen2019). There is also strong evidence that public and private R&D investment together create localised spillover effects, benefitting both productivity levels and RIS more generally. Moreover, universities act as a strong catalyst for these spillovers (Kantor and Whalley, Reference Kantor and Whalley2014), via both the funding of R&D directly and investments in RIS commercialisation mechanisms such as technology transfer agencies (Collinson, Reference Collinson2020; Hausman, Reference Hausman2022; Johnston et al., Reference Johnston, Wells and Woodhouse2022). Innovation is also key to improving sustainability and reaching net-zero targets, but sometimes with the cost of lowering productivity. Different innovation strategies or business models can lead to more or less inclusivity through impacts on employment and wage levels. We examine some of these policy trade-offs in Section 5.

In 2020, the UK spent 2.93% of GDP on R&D. Businesses fund just under 60% (£38.7 billion in 2021) and perform just over 70% (£46.9 billion) of R&D, while the public sectors fund 19% (£12.8 billion) and perform 5% (£3.4 billion). Higher education institutions, primarily the research-intensive universities, are key in that they fund 8% (£5.6 billion) but perform 25% (£14.9 billion) of R&D (Panjwani, Reference Panjwani2023).

The evidence shows that specific areas of discretionary government R&D funding, including direct public R&D expenditure and higher education R&D, are heavily skewed towards already productive and wealthier regions. Direct government R&D expenditure in 2016 was £60 per capita in London and the South-East of England, but only £21 in the North of England, £14 in the Midlands, and £7 and £5 in Northern Ireland and Wales, respectively (Forth and Jones, Reference Forth and Jones2020). More recent public R&D funding data, using a different definition (so not directly comparable), shows that 52% of the total in 2021 was spent in London, the East and South-East of England (£34.4 billion). This amounts to £1,406 per person, which is well above the UK average of £987 per person, and contrasts to £534 of R&D funding per person in Wales (46% below the UK average) (Panjwani, Reference Panjwani2023). At least part of the reason for this concentration is that many leading research-intensive universities are based in London or in the ‘golden triangle’ linking the capital city with Oxford and Cambridge. But this illustrates the ‘catch-22’ cycle of reinvestment in more productive places, which underlies the spatial polarisation we are discussing (Collinson et al., Reference Collinson, Hoole and Newman2023a).

Comparisons with the United States are generally incomplete, but they do suggest that success in attracting high-end investment, particularly R&D-intensive assets to ‘peripheral regions’, can be partly attributed to significant state-level support, including tax breaks and subsidies. Co-investment by central government can also pump-prime wider effects. The Research Triangle Park in North Carolina, for example, originally attracted IBM, Burroughs Welcome and others alongside government laboratories such as EPA NIEHS. There are similar success stories in Tennessee and Texas and more recently Arizona.

Germany provides a more useful comparator, in that public sector and higher education R&D investments are explicitly targeted at less-well-off places to counteract regional economic inequalities. The UK’s approach has tended to worsen these inequalities. Moreover, there is evidence that city-regions such as Manchester and Birmingham have much higher potential to link university-based R&D with local absorptive capacity, given the large hinterland of firms across a wide range of sectors (compared to Oxford or Cambridge, for example). Birmingham, in the West Midlands, attracts disproportionately more private R&D investment than public investment, suggesting a difference between the market drivers for locating R&D activities and the selection mechanisms for targeting public R&D resource allocation (Forth and Jones, Reference Forth and Jones2020).

2.4 Income, Assets and Wealth

In terms of income and deprivation, the spatial distribution patterns match those of high and low economic growth and productivity. Geary and Stark (Reference Geary and Stark2016) show that the South-East has been the richest region of the UK since at least the 1860s, though regional inequalities reduced gradually between the 1860s and the 1970s, since when they have increased again. In Capital in the 21st Century, Thomas Piketty (Reference Piketty2014) also takes a long-term view using data on income distribution for the US and European countries (including the UK) between 1910 and 2010. This shows a U-shaped curve of decreasing and then increasing inequality for all countries, but one that is particularly pronounced for the UK and even more so for the United States. At the start and end of this trend line, the top 10% of US earners receive 50% of total incomes. The relative Gini coefficients show a worsening trend in recent decades, and the inequality of income distribution in the United States now is fairly similar to that of Tanzania and Peru, for example. Piketty’s seminal work has been criticised and even contradicted (e.g. Hudson and Tribe, Reference Hudson and Tribe2017), but it triggered a stream of work on the topic, including many more fine-grained and sophisticated empirical studies.

A robust, systematic comparison of spatial wage disparities ‘between and within similarly defined local labour market areas (LLMAs)’ for Canada, France, Germany, the UK, and the United States between 1975 and 2019 is conducted by Bauluz et al. (Reference Bauluz, Bukowski and Fransham2023). By the end of this period, spatial inequalities in average wages across these LLMAs are similar in Canada, France, Germany and the UK, whereas the United States exhibits the highest degree of spatial inequality. However, they have nearly doubled in all these countries, over the forty years analysed, except for France where they are closer to 1970s levels. Notably, this study suggests that the contribution of spatial geography or place in explaining national wage inequality has stayed constant in all except in the UK where there is a significant increase.

Real wages grew by 33% each decade from 1970 to 2007 in the UK, but low or no growth since 2007 has worsened income inequality. As a result, UK households are 9% poorer on average than French counterparts and 27% poorer for low-income families. In 2019, income per person in the wealthiest local authority (Kensington and Chelsea) was £52,500, over four times that of the poorest, which was Nottingham at £11,700 (Thwaites and Try, Reference Thwaites and Try2023).

Household wealth, which accounts for assets (including house ownership), savings and investments, is perhaps a better general indicator (than income) of inequality and relative resilience in the face of economic shocks. In the United States, this has now reached a level whereby an estimated 67% of wealth is owned by the top 10% of earners, with the lowest 50% of earners owning 2.5% (Sullivan, Hays and Bennett, Reference Sullivan, Hays and Bennett2023). In the UK, 43% of wealth in the UK is owned by top 10% of earners and the lowest 50% of earners own 9% (ONS, 2022). Some of Piketty’s detailed explanation is summarised in Section 3. Separate studies have identified a similar pattern in emerging economies, notably China (Dunford, Reference Dunford2022). As in the US example, growth rates are stronger than the global average, but inequalities are also growing faster.

2.5 Poverty, Social Mobility and Health

By one definition, 22% or 14.4 million people in the UK were in poverty in 2021/2022. The West Midlands had the highest rate at 27%, followed by the North-East, Yorkshire and The Humber, the East Midlands and the North-West. But also, near the top sits London at 25%, standing out from the least-poor regions of the South of England. As by far the largest city in the UK, London combines the most productive and wealthiest, with some of the poorest in the country (JRF, 2024).

The poorest places are also those regions with the lowest levels of social mobility and opportunity, indicating the likelihood of moving out of poverty into higher-income socio-economic groups. Out of the twenty-four at the bottom of the list, twenty-one are in the North (East and West), Yorkshire and The Humber, and the Midlands (East and West). London, the South-East and the South dominate the rankings of the most socially mobile areas and only three are in the above regions (Social Mobility Commission, 2020). So, despite having some of the poorest neighbourhoods in the country, Londoners have a much higher level of social mobility relative to counterparts in other regions.

Average mortality rates for men and women in England are now worse than most European counterparts (although not Poland, for example), but better than the United States. Again, the regional distribution patterns described earlier in this Section also apply to mortality rates and general health data across the UK. Male life expectancy in England in 2020 was 10.3 years (8.3 years for females) shorter in the most deprived areas (Glasgow for the UK and Blackpool for England) compared to the least deprived (Islington, London). This gap was a full year larger compared to 2019 because of COVID-19, which exacerbated existing health inequalities. However, this is still the largest health inequality gap recorded by Public Health England after over two decades of comparable records. Although COVID-19 contributed significantly as a major cause of death in 2020, higher mortality rates from heart disease, lung cancer and chronic lower respiratory diseases in deprived areas were still important contributors (Public Health England, 2024). Other barriers to social mobility follow this distribution including the prevalence of mental illness, learning and other disabilities, obesity and diabetes.

2.6 Connecting Wealth Creation and Wealth Distribution

When we integrate data and evidence connecting spatial and socio-economic inequalities in a systematic way, we can see the significance of these trends in terms of the growing pressure on society and political systems in capitalist economies. A widely cited analysis by McCann (Reference McCann2020; McCann and Ortega-Argilés, Reference McCann and Ortega-Argilés2021; McCann et al., Reference McCann, Ortega-Argilés, Sevinc and Cepeda-Zorrilla2021) gave rise to the term ‘the geography of discontent’ linking economic, social and political polarisation across the UK following Brexit, and later COVID-19. This concludes that the UK is ‘almost certainly the most inter-regionally unequal large high-income country’ on the basis of twenty-eight measures of regional economic inequality compared across industrialised economies. He also concludes that the UK’s interregional inequality is particularly notable given that it occurs over small geographic distances.

McCann (Reference McCann2020) shows that relative to counterparts, the UK is in the top half for all twenty-eight measures, is in the top quarter for twenty-one of the twenty-eight measures and is the most unequal on five of the twenty-eight measures. These are: (1) GDP per capita, ratio of highest-to-lowest OECD TL3 regions; (2) GDP per capita divided by national GDP per capita, taking the difference between the highest and lowest OECD TL3 area; (3) RDI (regional disposable income) per person, taking the ratio of highest-to-lowest 20% across OECD TL3 regions; (4) Gini index of regional GDP per capita across OECD TL3 regions; (5) Gini index of regional RDI per capita across OECD TL3 regions. The comparison shows that the United States is more unequal than the UK on five measures, and the UK is more inter-regionally unequal than the United States on six measures (which we can ‘score’ as 6–5), while they are equal on two measures. Similar comparisons with other OECD countries show that the UK is more unequal than the following countries: Spain 3–19, Japan 0–18, Germany 4–17, South Korea 2–16, France 4–15 and Italy 10–11.

McCann and colleagues make the empirical link between low productivity and inequality. Much of this is reaffirmed and extended in a detailed analysis by Stansbury et al. (Reference Stansbury, Turner and Balls2023), who conclude that the UK’s current ‘regional economic inequality problem is primarily a productivity problem’ rather than an (un)employment problem, which was a key factor in previous periods such as the 1980s. They map productivity differences between London and the South-East against other regions (including Europe) using comparisons of population-weighted coefficient of variation in regional GVA per worker. The underperformance of most city-regions outside of London is a key focus. These cities, and Manchester and Birmingham in particular, ‘do not appear to benefit from the agglomeration economies seen in other industrialised countries, where scale and population density are strongly associated with higher productivity’ (McCann and Yuan, Reference McCann and Yuan2022; Rossi et al., Reference Rossi, Baines and Lawton Smith2023). This analysis also points to historical periods of rapid deindustrialisation, relative to counterparts in the South-East of England and across Europe. But while education and skills are a factor affecting both productivity and income differentials, ‘there is still a large regional productivity gap even controlling for education’.

3 The Causes of Failure

Prior analyses of capitalism (and there are a lot) commonly emphasise the need to understand the system as a whole. But it is a complex adaptive system at any scale (firm, sector, region, nation) with a wide variety of relationships between many components, with both the components and the relationships changing rapidly. Moreover, the lack of an understanding of how individual or combined interventions impact many parts of this system is a contributing factor behind the failure of many policy interventions (Balland, et al., Reference Balland, Broekel and Diodato2022).

The excellent ‘Varieties of Capitalism’ (Hall and Soskice, Reference Hall and Soskice2001) provides a framework for understanding how and why capitalist systems vary around the world and has led to further systemic research on these combined effects. Differences across five ‘spheres’, industrial relations, vocational training and education, corporate governance, inter-firm relations and relations with employees, underpin distinctive types of capitalist system. Writing some time ago, the authors also proposed that liberal market economies (such as the United States, UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Ireland) tend to distribute income and employment more unequally than coordinated market economies (e.g. Germany, France, Japan). The institutional arrangements of a nation’s political economy tend to push its companies towards particular kinds of corporate strategy and innovation, and so help explain different models of wealth creation. But these forms of institutional, financial and governance structures are also important determinants of wealth distribution, underpinning path dependencies that help concentrate wealth in particular groups and places.

In a subsequent analysis, Hall and Gingerich (Reference Hall and Gingerich2009) construct indices to assess whether patterns of coordination in the OECD economies conform to the predictions of the theory and compare the correspondence of institutions across sub-spheres of the political economy. Differences in shareholder power, dispersion of control, size of stock market, level of wage coordination, degree of wage coordination and labour turnover help explain differences in wealth distribution. More recent research has built on this to add further insights into economic growth and inequality (Behringer and van Treeck, Reference Behringer and van Treeck2022; Movahed, Reference Movahed2023).

In Capital in the 21st Century, Thomas Piketty (Reference Piketty2014) maps long-term patterns of economic growth over periods of both convergence and divergence of incomes and well-being across households in different nations. His overarching conclusion is that the ‘rapid accumulation and concentration of wealth allowing top earners to separate themselves from the majority’ can continue ‘even when all conditions of market efficiency for economists are satisfied’. Specifically relevant to the current trends in the US and UK economies (which are Piketty’s key examples), ‘even when low growth dominates, return on capital can be high but only benefits the wealthy’. He points to the diffusion of knowledge and skills as the most important force in favour of greater equality, and something that does not happen automatically.

Several factors help explain this growing polarisation. Piketty suggests that top managers have either increased their productivity relative to that of other workers or, more likely, are able to set their own wages ‘without limit and without connection to productivity’. Perhaps more significantly in the current era, private wealth accumulation in terms of real estate (particularly in the UK), financial assets, and professional capital net of debt all takes on a disproportionate weighting at times of slow growth and when wages lag inflation. This drives divergence.

Economists and management theorists have also noted the dangers and imperfections with capitalist models for a long time. As noted by Diane Coyle (Reference Coyle2023), Adam Smith famously noted the risks as well as advocating the benefits of the dynamism of increasing specialisation. Collusion among producers at the expense of consumers undermined competition and allowed the benefits of wealth creation to be captured by those with market power. Others have noted similar tendencies within evolving business models as we have ‘… transitioned into the era of financialization, with shareholder value replacing customer value as the purpose of the corporation, leaving managers to divert resources to their own enrichment and that of shareholders, at the expense of investment in future innovation’ (Denning and Hastings, Reference Denning and Hastings2024).

Before looking more closely at the UK experience, Spain provides an interesting, brief example of a successful ‘turnaround’ economy. As one of the original European laggards, it suffered from slow GDP growth and very weak wage growth for many decades, until recently. In 2024, Spain’s GDP grew by 3.2%, which was about five times the eurozone average growth rate and more than the United States. A successful tourism industry, strong public investment (partly helped by the EU’s COVID pandemic recovery funding), increased services and industrial exports to the European single market, a stronger financial services and technology sector, and low energy costs due to investment in renewables, have driven this growth. Immigration has also brought in cheaper labour, but unemployment has declined. Productivity, however, has remained low relative to the OECD average (OECD, 2024).

Importantly, despite the influx of lower-paid immigrant labour, wage inequality has improved in Spain. Left-leaning governments since 2018 have strengthened wage-setting institutions, collective bargaining, employment protection and job retention support. Spain has also significantly increased its minimum wage (by over 50%) to promote a broader sharing of productivity gains with workers, particularly those with low wages. The minimum wage level was raised in 2019 and again more recently. This has increased the wages of directly affected workers by almost 6%, while (contrary to economists’ predictions) it reduced employment by only 0.6% (OECD, 2024). It may be a bit too early to tell, but this could be an example of strong government intervention triggering both high growth and reduced income polarisation, without impacting productivity levels.

3.1 UK-Specific Challenges

Alongside the general difficulties described in Section 2, the UK faces additional challenges, many of which are related to regional imbalances (Pike et al., Reference Pike, Rodríguez-Pose and Tomaney2016). Three have been identified recently by Coyle, van Ark and Pendrill (Reference Coyle, van Ark and Pendrill2023). The first is long-term underinvestment in the economy, referring to physical, human and intangible capital, public and private investment. UK companies have invested 20% less than those in the United States, France and Germany since 2005 (public investment is discussed in Section 3.2). This puts Britain in the bottom 10% of OECD countries and is estimated to have cost 4% of GDP (Thwaites and Try, Reference Thwaites and Try2023). This reflects both public-sector and private-sector choices and incentives. Second, the inadequate diffusion of productivity-enhancing practices between firms and places, despite world-leading science and technology. Third, institutional fragmentation and a lack of joined-up policies partly related to the centralisation of decision-making in London and the fragmented nature of governance structures elsewhere.

Dealing with each of these challenges benefits from a place-based approach as all three are negatively impacting regions outside of London and the South-East of England. This can also help reveal differences in the (sub-)varieties of capitalism operating at a local level, providing a better understanding of their distinctive challenges and the types of customised policy interventions needed to tackle these.

Aspects of both ‘localisation economies’ and ‘urbanisation economies’ appear to be failing to fully operate in some large UK city-regions outside of London. The former, also termed Marshallian externalities, are the agglomeration benefits that firms experience from being located near to many other similar firms, including access to skills and knowledge. The latter, also known as ‘Jacobs externalities’, stem from the proximity of many firms from different sectors in urban centres, providing access to a range of skills and knowledge and a pool of clients and consumers (Rossi et al., Reference Rossi, Baines and Lawton Smith2023).

Following an economic growth diagnostic approach developed by Hausmann, Rodrik, and Velasco (Reference Hausmann, Rodrik, Velasco, Serra and Stiglitz2008; and Hausmann, Klinger and Wagner, Reference Hausmann, Klinger and Wagner2008), several studies identify ‘binding constraints’ on regional growth. These aim to isolate factors that are key targets for effective policy interventions. After discounting some factors, Stansbury et al. (Reference Stansbury, Turner and Balls2023) find evidence that the following are key: a relative shortage of STEM degrees; binding transport infrastructure constraints within major non-London conurbations; a failure of public innovation policy to support clusters beyond the South-East, in particular through the regional distribution of public support for R&D; missed opportunities for higher internal mobility due to London’s overheating housing market. They subsequently focus on four key policy levers in the areas of education, infrastructure, support for R&D and access to finance.

In the UK, wealth accumulation through ownership of assets, notably house ownership, but also stock market and pensions investments, have helped drive polarisation. Those without assets experience a growing reliance on short-term earn–spend cycles and debt accumulation locks deprived communities in ‘left behind’ regions. Successive economic shocks (Brexit, COVID and Ukraine) have had a greater impact on low-income regions outside London and South-East England, particularly those with a higher dependence on manufacturing industries and the movement of physical goods. There is also some evidence that quantitative easing led by the UK government during and after the COVID pandemic indirectly helped wealthier places and/or households (Sensier et al., Reference Sensier, Rafferty and Devine2023).

Structural embeddedness and path dependency are also influenced by the longer-term effects of deindustrialisation on particular regions. Stansbury, Turner and Balls (Reference Stansbury, Turner and Balls2023) cite data from the EU ARDECO dataset mapping the biggest ten-year periods of deindustrialisation across all EU regions, 1980–2019 in terms of a ‘change in employment share’ (ranging from –0.1 to –0.17). With the transition from legacy industry sectors, especially mining and manufacturing, to financial and creative services, for example, regions across Europe experienced significant decline and pressure to restructure. This was partly related to their initial level of dependence on a specific industry sector in decline (i.e. not so ‘smart specialisation’ in retrospect) as well as the growth potential in other sectors. Three German regions, Sachsen-Anhalt, Sachsen and Thüringen, top this table, but only appear once, for the 1991–2001 decade. Any (NUTS2) region in Europe can be listed more than once, for each subsequent decade that a high level of change in employment share occurred. The key point for us is that sixteen out of the thirty-one regions listed are in the Midlands (nine in the West and seven in the East Midlands) and twenty in the UK (Stansbury, Turner and Balls, Reference Stansbury, Turner and Balls2023, table 1, P.65).

The term ‘development traps’ has been used to describe places that get stuck in persistent low-growth or stagnation, often linked to an extended dependence on legacy industries (mining and manufacturing in the UK case) and failure to transition into new growth sectors. Some studies emphasise a lack of capabilities to develop high-complexity activities in regions with industry structures that are dominated by low-complexity economic activities. This sits within a broader evolutionary framing that analyses regional differences in terms of the local mix, complexity and relatedness of industry activities (or industry portfolio) associated with ‘smart specialisation’ policy approaches (Balland et al., Reference Balland, Boschma, Crespo and Rigby2019, Reference Balland, Broekel and Diodato2022; Iammarino et al., Reference Iammarino, Rodriguez-Pose and Storper2019; Pinheiro et al., Reference Pinheiro, Balland, Boschma and Hartmann2022).

At the same time, a number of factors benefit London and the South-East to drive further wealth polarisation. The concentration of asset wealth (particularly property ownership and pensions), supported by increased house prices, sits alongside higher levels of disposable income and consumption, which creates stronger multipliers benefitting local goods and service providers. This is partly a result of where the wealthy live and spend their income, but also results from the economics of agglomeration that benefit places that are home to the largest or the most productive firms. In Keynesian terms, localised aggregate demand externalities benefit some places and not others, for considerable periods without market interventions. Because large agglomerations also benefit disproportionately from investment and spending that takes place elsewhere, via national value chains, London benefits more than any other city-region from economic activity and added value wherever it is created across the country.

Some of the same factors are driving the polarisation in other countries. As noted by Kemeny and Storper (Reference Kemeny and Storper2023), the significant increase in spatial inequality in the United States, particularly since 1980, is mainly driven by a small number of ‘resiliently high-income superstar city-regions’. Competition between states and cities has increased, but many US states have still managed to attract or stimulate entrepreneurship, and the overall national growth rate has been stronger than the UK’s. Perhaps this makes the increased inequality in the United States less noticeable.

A final driver is public spending and investment, which privileges London and the South-East both through subsidies to reduce the ‘natural’ market costs of agglomeration, for example, through very high per capita funding for transport. But also, through higher levels of support for education and low-income communities compared to other UK city-regions. The cycle of attraction, central to market economies, whereby private investment and high-skilled, high-income workers tend to concentrate in increasingly prosperous city-regions, is intensified in the current political system by incentives for public investment, which prioritise the most productive places (Collinson et al., Reference Collinson, Hoole and Newman2023a; Newman et al., Reference Newman, Driffield, Collinson, Gilbert and Hoole2023). This is examined more thoroughly in the following section.

Arguably, as the capacity of the UK economy to create value has declined, mechanisms that enable value appropriation by smaller numbers of (spatially clustered) people have become more prevalent. At the same time, central government has directed public-sector spending to boost the most successful regions and underfunded the others. The point is not only that this is unfair or immoral; it is not sustainable, in economic or political terms.

3.2 Regional Governance Structures and Public Spending Patterns

In terms of tax raising and spending powers, and many other areas of governance, the UK is one of the most centralised governments of any advanced economy. It has a smaller number of sub-regions with local governance structures, overseeing relatively large number of inhabitants. Moreover, on average and compared to OECD counterparts, these sub-national government bodies have the responsibility for investing a much lower proportion of public expenditure than central government.

The OECD breaks down sub-national governments into three levels: municipal (the UK has 374), intermediary (35) and regional or state level (three, being England, Scotland and Wales). The average size of a ‘municipality’ in the UK is 180,564 people compared to an average for the thirty-eight OECD countries of 10,016. The average number of municipalities per 100,000 inhabitants in the UK is 0.6, compared to an OECD average of 10.0. Only Korea and Ireland are similar in having a small number of sub-regions with large populations. Public expenditure accounts for 48.6% of GDP in the UK (the OECD average is 45.5%) and the sub-national government investment as a proportion of public investment overall is 28.8% in the UK compared to an OECD average of 54.5% (OECD, 2023a).

In parallel with these patterns of spending, the scale of central government, partly indicated by the proportion of civil service employees based in London, has grown while declining in every other English region. One estimate shows that the civil service headcount in London increased by 22% between 2010 and 2022 and by almost 8% in Wales and 1% in Scotland (as devolved governments) but fell by over 30% in some other English regions during this period. Central government in the UK now employs more people than at any time in its past while local government employment is at its lowest point since 1963 (Forth, Reference Forth2023).

Alongside a highly centralised governance structure controlling public spending, we note significant imbalances in the proportion of public spending going to different regions. Data on education, skills and public R&D investments are presented in Sections 2.2 and 2.3. Alongside these, housing and transport infrastructure are underpinning factor endowments that support local economic growth. Moreover, public investments in these and other endowments and amenities can ‘crowd in’ private-sector investment and stimulate wider multiplier effects (Crafts, Reference Crafts2009; Vasilakos et al., Reference Vasilakos, Pitelis, Horsewood and Pitelis2023).

Transport provides a clear illustration of both an overall decline in investment and a strong regional bias in government support. Transport infrastructure investment as a share of GDP overall has been low in the UK by international standards. UK cities outside of London have less extensive and less reliable public transport networks than other Western European cities. Taking into account population differences, ‘the share of the total city population that can reach the city centre within 30 minutes by public transport is 23 percentage points lower in the UK’s cities than in Western Europe’ (Coyle et al., Reference Coyle, van Ark and Pendrill2023). Data on total public transport investments across regions shows that since 2010 £1,500 per person has been spent in North England compared to £3,000 per person in the South-East of England and £6,000 per person in London (Coyle et al., Reference Coyle, van Ark and Pendrill2023; Forth, Reference Forth2023). Alongside this, lower housing density in UK cities amounts to weaker agglomeration economies, including lower levels of accessibility to available jobs in city centres for lower-income households (Rodrigues and Breach, Reference Rodrigues and Breach2021). Further analysis and empirical evidence describing the interregional imbalance in public investment and spending and outlining some of the causes and implications are in Newman et al. (Reference Newman, Driffield, Collinson, Gilbert and Hoole2023) and Collinson et al. (Reference Collinson, Driffield, Hoole and Kitsos2022).

The ‘Green Book’ investment evaluation and appraisal process, which is a set of procedural guidelines used by Treasury and other government departments to assess the benefit–cost ratio or trade-offs for a public investment proposal, is an important example. At the general level, and acknowledged now by Treasury, the approach is too focused on measurable monetary quantities in terms of value for money at local, regional and national levels. A mechanistic modelling approach habitually leaves out social value and other contextual factors for which there are no market prices. It is also applied in attempts to measure likely outcomes when the complexity of causal linkages is too great for reductionist models.

More specifically, economic growth investment appraisals guided by Green Book have tended to take productivity (GVA per capita) as the main, or only, indicator of success. As such, regions with the highest potential to improve productivity with investment in factor endowments like transport infrastructure, housing, education or R&D assets have received the most funding from central government. These are the regions with already high levels of productivity, and superior factor endowments, that is, London and the greater South-East of England (Brown, Reference Brown2023; Coyle and Sensier, Reference Coyle and Sensier2020; Mealy and Coyle, Reference Mealy and Coyle2022). This is part of a wider, entrenched path dependency created by a policy regime that privileges places that are more productive, rather than enabling growth in lagging regions. It is embedded in the political economy of the country and in the selection mechanisms for resource allocation, or wealth distribution, across the country. These are important ‘rules of the game’ that maintain imbalances that need to be reversed.

Some would say that these rules of the game are politically motivated by an entrenched elite that uses them to maintain privileged access to the mechanisms of rent appropriation. Clear evidence for this is difficult to find or build, partly because of the indistinct nature and increased ‘churn’ in the members of the controlling elite. But the evidence does show a more centralised government, with more civil service employees and elected leaders based in London, plus patterns of investment strongly preferencing London and the South-East. As indicated throughout this Section, both political structures and economic patterns need to be understood in tandem to provide insights into socio-economic inequalities. It is important to both distinguish and to connect political agendas (which can be short-lived or persistent), institutional and governance infrastructures for raising and spending public finance (which tend to evolve and become path-dependent), and market forces. The latter act across a changing geography of investment and disinvestment as capital and skills move around, influenced more or less by policy interventions.

Structural weaknesses in the UK capitalist system are now being revealed and exacerbated by short-term decision-making, rapidly changing policy agendas and weak governance under successive national governments. Policy churn and short termism, relative to both other advanced economies and the UK in the past, have been noted in a number of studies (Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, Sensier and Pike2022). This has undermined the economic resilience and worsened the impact of recent economic shocks on some places, alongside the effects of long-term specialisation in lagging industry sectors (Qamar et al., Reference Qamar, Collinson and Green2022; Sensier et al., Reference Sensier, Rafferty and Devine2023). The spatial geography of these impacts and subsequent increases in polarisation between the ‘haves and have nots’ provides a useful framing, following the ‘geography of discontent’ across UK regions (McGann and Ortega-Argiles, Reference McCann and Ortega-Argilés2021).

The concentration and centralisation of decision-making power over the allocation of public resources, the lack of devolution and the presence of ‘weak institutions’ outside of the centre compound these challenges (Collinson et al., Reference Collinson, Hoole and Newman2023a; Rodríguez-Pose and Muštra, Reference Rodríguez-Pose and Muštra2022). The mechanisms of metagovernance present structural challenges to the ‘levelling up’ agenda that the country needs. A complex and ineffective mix of quasi-market approaches, like the Green Book approach, and the continual reinforcement of state hierarchies, with different flavours brought in by successive political leaders, prevents the development of local sovereignty (Fransham et al., Reference Fransham, Herbertson, Pop, Bandeira Morais and Lee2023; Tomaney and Pike, Reference Tomaney and Pike2020). Restrictions around local government activity significantly constrain local capacity to build public–private coalitions to deliver economic development in the ‘left behind’ regions (Coyle and Muhtar, Reference Coyle and Muhtar2023; Lumpkin et al., Reference Lumpkin, Meléndez and Bacq2024; Newman et al., Reference Newman, Driffield, Collinson, Gilbert and Hoole2023).

At the time of writing this, the stark change of leadership in the United States with the embedding of President Trump and acolytes into a wide range of governance structures is partly driven by perceptions of systemic bias in previous administrations. The new regime is certainly embarked on a wholesale restructuring of the government apparatus, from new targeted outcomes to incentive structures, funding mechanisms, the allocation of decision-making power, radical shake-ups of the administration and its practices, alongside changes to the federal relationship with individual states, and a fundamental reboot in relations with other nation states. Salter (Reference Salter2024) in a contribution to this Element series directly comments on this change and the need for greater political equality, underpinned by reciprocity and power sharing. It is too soon to see where this might lead, but any reduction in the current level of socio-economic inequality in the United States seems highly unlikely at this stage. The opposite seems the more probable outcome.

We might ask whether this type of radical political solution could support positive change in the UK context. There do seem to be fewer scenarios in the UK context where this radical type of political change seems viable, but ‘never say never’. The real question, given the central concerns of this Element, is whether such a power shift and/or a fundamental change in the style of government could trigger a significant improvement in both productivity and socio-economic equality in the UK. The answer is probably yes, at least as regards the latter, a major transformation in the structure, style and mechanisms of government, is a requirement. The current government has made policy changes with some of these targets in mind but once again does not appear to be changing enough of basic structural conditions that underpin the the range of challenges presented here. As described throughout this Element, the problems facing the UK are so entrenched, long-term and path dependent that a turnaround requires something new.

Putting politics and the wider considerations to one side, we return to the more limited scope of this Element. Regardless of the kind of governance regime in place, a specific set of practical policy interventions are needed to tackle the challenges outlined in Section 3. The next section (Section 4) describes why and how these need to be ‘intelligent interventions’. Precisely targeted investments and intercessions that are going to leverage very limited resources to engineer significant change need to be based on data, evidence and intelligence.

4 A Need for Intelligent Intervention

Policymaking is a complex (imperfect, organic, contested) selection environment, and successive UK governments have been failing to invest in the right ways and in the right places for long-term balanced (inclusive) economic growth. A wider range of changes need to be made than we can capture in this Element. We could focus on agency and incentive structures that have supported the concentration of wealth, particularly asset ownership, or the selection environment responsible for directing politicians to allocate public resources in ways that have increased inequalities. But we chose to focus on a specific sub-set of practical recommendations in this section and the next (Section 5).

Policy interventions that have any chance of improving the development pathways of regions trapped in low-growth cycles need to be precise and customised for the challenges and growth potential of these regions. Currently, there are gaps in, and between, (1) data on the symptoms and evidence of specific areas of failure in capitalist systems, (2) a comprehensive understanding of the underlying causes of failure, and (3) feasible, realistic options for selectively intervening in different parts of these economic systems to improve the outcomes. More generally, a gap exists between well-meaning but naïve calls focused on the ‘destruction of capitalism’, and practical but path-breaking changes to put economic systems on better growth trajectories.

Much of the public narrative is grandiose and idealistic, calling for a wholesale change in the values and behaviours of corporations, consumers and political leaders. This may well be needed, but it will not happen without real-world changes to the incentive structures and selection mechanisms that underlie their behaviours. Alongside the evangelising, among the growing number of studies on corporate social responsibility and ethical capitalism, this gap is now being filled with more insightful analyses. Selected writings are starting to bridge high-level proselytising about culture, trust and values with interventions that are based on real-world evidence of the problems and potential solutions.

For example, a recent book by Lavie (Reference Lavie2023) calling for a cooperative economy, which initially appears to be overly idealistic, does provide ideas for some intelligent interventions. The ‘ideal’ is ‘an ethical community-driven exchange system that relies on collective action (‘prosocial behaviour’) to promote societal values while accounting for resource constraints …’ and ‘moves away from a materialistic orientation, limiting overconsumption and excessive profit-making’. All obviously desirable, but in explaining the design principles for a cooperative economy, more realistic, evidenced interventions to enhance economic equality are outlined. These include the use of price subsidisation, effective barriers to prevent the emergence of monopoly platforms, and legally limiting disparities in income and wealth accumulation.

Another analysis, ‘The Profiteers’ (Marquis, Reference Marquis2024), clearly and helpfully articulates how firms have managed to privatise, or ring-fence, profits and the rewards from wealth creation while socialising or externalising the ‘costs of environmental damage, low wages, systemic discrimination, and cheap goods’. This provides clear targets and mechanisms for intervening, underpinned by a strong understanding of how firms have been able to limit their own exposure to the full social and environmental costs of economic activity to maximise profits. It also comes with a starting point for change in the form of the ‘B Lab’ certification process committing companies to putting the rights of workers, community impact, social benefits and environmental stewardship on an equal footing with financial shareholders (Marquis, Reference Marquis2020). This sits alongside other contributions that seek to understand the trade-offs between shareholder- and stakeholder-driven structures, and private-sector versus government-mandated solutions to social problems (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Waldman, Siegel and Pepe2022). For many authors, a core aim is to address the declining trust in capitalism, which could lead to less intelligent interventions and significantly worse future outcomes, driven by short-term political ambition and/or ‘mob rule’ through social media.

A final example comes from the work of Mazzucato, who is known as an advocate of mission-driven economic change with innovation at the heart of growth, and government taking a key role (Mazzucato, Reference Mazzucato2021; Mazzucato and Perez, Reference Mazzucato, Perez, Reinert and Kvangraven2023). A deep understanding of innovation systems and the historical success and failure of related government interventions through time and across various national contexts underpins this analysis and helps to connect grand macro-level shifts with practical tools for driving change. Mazzucato also adds robustness by applying policy evaluation approaches to estimate fiscal multipliers and crowding-in effects, for example, from private investment in R&D (Deleidi and Mazzucato, Reference Mazzucato2021). This provides a link to the work of City-REDI, as does a shared belief that ‘without smart government at the organisational level, smart (innovation-led) growth is impossible’.

From these accounts, it is clear that targeted interventions that are going to leverage limited resources to engineer significant change need to be based on data, evidence and intelligence. This principle underpins the work of City-REDI, the City-Region Economic Development Institute, at the University of Birmingham. It provides a real-world example of an attempt to improve the precision of policy interventions to improve regional economic growth pathways.

4.1 City-REDI

The UK’s over-centralised government structure and a lack of devolved power and resources at the local level have reduced the ‘quality’ and capacity of institutions in regions outside of London and the greater South-East. Local agencies lack the resources, capacity and capability to intervene intelligently to improve their growth pathways. This means both analyse and deliver precise, targeted investments and interventions customised for the challenges and potential growth opportunities that their region offers.

This is the gap that City-REDI at the University of Birmingham was designed to fill, and examples of its work feature throughout this Element.Footnote 1 A key aim, driven by regional stakeholders as the main research users, has been to increase the precision of policy interventions, across a wide range of areas, from business support or skills and training programmes to public R&D investments. Helping policymakers select locally appropriate interventions, and evaluate the relative costs, benefits and trade-offs in terms of different kinds of growth outcomes (productivity, inclusivity and/or sustainability) supports the better use of scarce public funds.

In the UK context, the growing need to improve productivity (wealth-creation capacity) while reducing inequality (improving wealth distribution) and improving sustainability also presented a set of policy trade-offs and challenges that policymakers needed additional analysis and evaluation tools to resolve. The spatial geography of economic impacts provides a distinctive, overarching theme to the institute’s work. With policy insights revealed by examining the dynamics of regional growth at multiple levels. This includes deep-dive case studies to assess the effects of public investments into start-up incubators, STEM assets or ‘innovation intermediaries’, for example (referenced in this Element). Industry sector surveys and comparative surveys on, for example, productivity constraints or business support programmes sit alongside the analysis of socio-economic change over time in households and communities.

4.1.1 REDI Toolkits

Within the portfolio of methodological approaches, there are a number of frameworks and tools, including logic chains, cost–benefit analysis, modelling, economic impact and multiplier effects. One example is the City-REDI multi-regional input–output (MRIO) model. This provides insights into the input–output relationships between industries at the regional level, and interregional trade spillovers to show the transmission of impacts from one region to another. The model has been applied, for example, to university student spending across UK regions to show significant regional variation in the resulting multiplier effects on GVA (and per capita GVA, a measure of productivity) and jobs created. London benefits the most from all spillover flows, because of the scale of its local economy and the number of firms based there. But Greater Manchester and the Birmingham city-region also benefit more from student spending, relative to other places because of the higher levels of absorptive capacity in these regions. That is, more firms involved in the value chains that supply the products and services that students spend their money on are local to these bigger city-regions (Carrascal Incera et al., Reference Carrascal Incera, Kitsos and Gutierrez Posada2022). As a focused example of the value of the model, the study shows how comparable patterns of spending create different local growth impacts depending on the industry structure of the region. More broadly, the MRIO model, alongside other evaluation tools, enables City-REDI analysts to estimate the multiplier effects of changes in spending or different kinds of new investments in a region, to that region. This then provides insights for policymakers wanting to understand the growth impacts of different kinds of government investments.

As background, it is worth noting that policymakers tend to assume that a £1 million public investment or subsidy into skills, transport infrastructure, science parks, R&D or amenities exclusively benefits the region receiving the investment. In fact, the interregional direct and indirect production and consumption multipliers are difficult to trace without modelling the relevant interregional effects. This complexity is often missing from policy analysis. It also helps us understand how, and to what degree, dominant cities like London, which host most firms (and headquarters), receive larger relative shares of the spillovers from consumption spending and investment in all regions.

4.1.2 When We Aim to Become Part of the Solution, We Often Reveal More of the Problem

The work of City-REDI outlined in this Section has undoubtedly made a positive difference to regional growth policy in the UK. But in the process, the scale and the entrenched, path-dependent nature of the problem has become clearer. The analysis of the local economic impacts of student spending patterns described in Section 4.1.1 provides a good example of this.

The accumulated experience of City-REDI researchers alongside a wide range of studies point to the need to take a systemic approach to understanding regional economic growth. These also show that changing the trajectory of city-regions that have persistently low productivity and high levels of inequality requires more resources and a very different level of intervention than has been tried in the past. No less, we would argue, than a reinvention of the capitalist system. Failure to intervene will leave left-behind communities with worsening levels of deprivation.

City-REDI has taken a systemic approach in a number of ways. As indicated, long-term and short-term, multilevel and multidisciplinary research is needed. But it is also valuable to assess the impacts of growth along a broader logic chain than is often attempted. This means connecting the drivers of economic growth not just with the outputs, such as improved productivity, greater GDP, higher firm-level profitability, more and/or higher-income jobs, and so on, but also with the outcomes, including increased household income, reduced social benefits dependency in deprived communities, greater economic resilience at the regional level, and so on. Similarly, the impacts of slow or no-growth in regions, which leads to an equal and opposite logic chain of negative outcomes, can be tracked and measured. When places fail to attract investment, firms or skilled workers, the cycle of decline can mean lower productivity, fewer or lower-income jobs, increased social benefits dependency, worsening health and welfare, higher crime and mental health problems.

Different interventions would probably be selected if the full, long-term costs of declining regions were fully understood, but academic research and policy analysts have tended to specialise on one or the other side of this cycle. The UK Treasury and government departments also tend to disconnect economic growth from socio-economic safety nets, in the same way as most governments.

Studying the ‘economic epidemiology’ or regional transmission effects of the COVID pandemic to the West Midlands region, alongside other economic shocks (Brexit, the Ukraine war), helped reveal these kinds of dynamic connections. City-REDI studies have shown that the region, and others like it, have higher levels of exposure and lower levels of resilience, in the face of such shocks (Billing et al., Reference Billing, McCann and Ortega-Argilés2019; Kitsos et al., Reference Kitsos, Grabner and Carrascal-Incera2023; Qamar et al., Reference Qamar, Collinson and Green2022). For example, Qamar et al. (Reference Qamar, Collinson and Green2022) show how the West Midlands’ economy is highly dependent, perhaps over-dependent, on the automotive manufacturing sector. Another study charts the knock-on effects of insolvencies, particularly among low-productivity, low-skilled small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), to low-income communities and household deprivation levels (Collinson et al., Reference Collinson, Lyons and Ma2023b). These estimate the wider socio-economic impacts of firm failure and increased unemployment, on local communities, that result from such shocks in the absence of specific kinds of intervention. But they also provide insights into what kinds of ‘defensive’ policies provide the best safety nets in difficult times, and which proactive policies can help overcome the barriers to growth in periods of opportunity.

The team at City-REDI shares a collective belief that more intelligent and targeted policy interventions can make a difference. The irony is that beliefs increasingly appear to be as important or possibly more important than data and empirical evidence as a foundation for driving large-scale change, for better or for worse. Some groups of people seem to be entrenched in beliefs that have no empirical basis and have little or no trust in those producing the evidence. This also needs changing.

For those without a strong belief in the current system of capitalism, we might be preaching to the converted when we call for change. But complete alternatives to market capitalism are very rare. For those with some belief in the capitalist systems of different varieties that dominate in every economy on the planet, we hope that the evidence above goes some way to convincing you that a major reinvention is needed.

5 Recommendations for New Varieties of Capitalism

Alternatives to capitalism are rare, but different varieties of capitalism thrive. However, the evidence summarised in Sections 2 and 3 tells us that a major reinvention is needed to make advanced economies like the UK fit for purpose in a changing world. Incremental changes to current structures are unlikely to bring about the level of change in the timeframe needed. Further evidence on why change is now imperative comes from studies that show a persistent relationship between inequality, slower economic growth, weaker social cohesion and political instability (Eatwell and Goodwin, Reference Eatwell and Goodwin2018; Piketty, Reference Piketty2020; Rodríguez-Pose, Reference Rodríguez-Pose2018).

This is not just about spending public funding more effectively and efficiently. It is also more than a moral imperative to reduce inequality. Failure to address these serious socio-economic imbalances will fuel further discontent, which could be increasingly voiced outside of the current channels for challenging the political and economic elites. It will also contribute to a longer-term decline in economic efficiency and therefore living standards. Finally, it will reduce the chances that the kinds of decisive, stable and trusted governance that is needed to tackle climate change will be established in the timescale required.

A fundamental shift to government structures that proactively enable, rather than simply react, monitor and control, is required to support the implementation of these recommendations. The institutions, governance mechanisms and wider political arena that underpin the selection mechanisms for directing resource allocation and moderating wealth distribution need to change. But enabling more distributed growth clusters will be more viable in the long run than providing an increasingly expensive safety net to limit the damaging effects of socio-economic inequalities.

Enabling inclusive growth means creating the conditions for higher levels of wealth creation in regions outside of London and the South-East of England. It also means policy interventions to promote a more even distribution of the benefits of wealth creation, including from national public investments. In the following, we first outline the kind of policy regime that could make a difference to uneven growth patterns in the UK context. If the evidence presented in the previous sections answer the question of ‘why’ change is needed, this is the ‘how’. Then we examine the need for local industry strategies as the focus of policy interventions (the ‘what’). These two elements are combined in a final section on RIS. Stronger RIS would support productivity and economic growth at the local level and particular kinds of innovation would enable more inclusivity.

5.1 The Policy Regime