1 Introduction

History is replete with efforts to reform American policing, yet this institution continues to suffer from a “crisis of legitimacy.” This Element begins by defining police legitimacy and the various ways that legitimacy has been jeopardized by police practices. The costs associated with the current model of policing are summarized, including the adverse impact on community members, police officers, and public safety. Some constitutionally protected populations are particularly vulnerable to police mistreatment, including people of color, the LGBTQ+ community, persons with mental illness, victims of crime, the homeless, and youth.

This review is followed by an analysis of reform efforts and why they have been ineffective in changing street-level policing and increasing public trust in the police. Weak implementation has contributed to this failure, but the primary barrier to success has been the overreliance on enforcement statistics to evaluate police performance. When evaluating the police, our society needs to “measure what matters” to the public, namely, how they are treated by the police. Giving voice to service recipients is critical for improving service and reducing any biases in treatment.

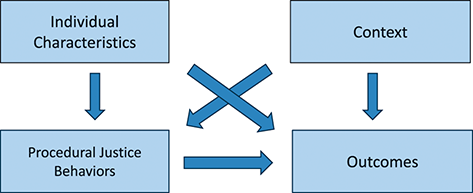

Hence, this Element offers a new, evidence-based approach to police innovation that should yield significant changes in police culture and improvements in police-community relations. New systems of measurement are described that focus on procedural justice and effective communication skills during police-public encounters. These reforms will require the routine collection, analysis, and utilization of data, along with advanced data analytics and artificial intelligence, to assess differences in policing across different types of calls for service, geographic areas, police units, supervisors, individual officers, and community members. Thus, new approaches to analyzing new datasets are proposed to advance our knowledge of policing and our understanding of police-public encounters. Bringing together two camps in criminology, this framework offers a clear link between process and outcome metrics, between officers’ treatment of the public and public safety.

Policing scholars have been outstanding in measuring specific constructs, like procedural justice, but the collection of good data will have absolutely no impact on police behavior or police legitimacy unless they are applied to police organizational practices. Translational criminology requires that we translate evidence into practice. Hence, this Element proposes evidence-based organizational changes that use new data to incentivize “good policing.”

Finally, this Element proposes “big science” to test the feasibility of this model prior to full-scale implementation. A proof-of-concept demonstration, with rigorous evaluations in multiple cities, will provide a road map for institutionalizing a national system of performance measurement and accountability. This level of innovation, with strong implementation fidelity, should increase procedural justice, increase police legitimacy, strengthen police-community relations, and increase public safety throughout the United States.

2 Police Legitimacy

Over a century ago, Max Weber conceived of legitimacy as something that people with power and authority must earn from those who are expected to follow them (Waeraas, Reference Waeraas, Ihlen and Fredriksson2009). In the policing field, legitimacy is judged, to a large extent, by whether the public believes that the police will act in the best interest of the community and whether they feel obligated to obey legal authorities (Tyler, Reference Tyler2006, Reference Tyler and Fischer2014; Tyler & Jackson, Reference Tyler and Jackson2013). Thus, police authority is not defined entirely by the badge, gun, or their legal powers but is also based on the public’s perception of them and is authorized by the “consent of the governed.” Police legitimacy is defined by the hearts and minds of the public.

Along these lines, the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing (2015) opened its report by underscoring the importance of public trust: “Trust between law enforcement agencies and the people they protect and serve is essential in a democracy. It is key to the stability of our communities, the integrity of our criminal justice system, and the safe and effective delivery of police services” (p. 1).

3 The Cost of Modern Policing

Emerging from the southern slave patrols in 1704 (Dulaney, Reference Dulaney2015; Reichel, Reference Reichel2022), American policing has an ugly history of brutality and political corruption that repeatedly undermined the legitimacy of the institution. Officers who worked for city police in the nineteenth century had unlimited authority to administer “street justice” and were part of a corrupt system of government (Walker, Reference Walker1977). After the civil war, the police were called upon to enforced “Jim Crow” laws for nearly 100 years. As a result, police brutality, deviance, and racial bias have been the subject of critical analysis for more than a century (Johnson, Reference Johnson2003; Kappeler et al., Reference Kappeler, Sluder and Alpert1998; Nelson, Reference Nelson2000).

Essentially, American policing failed to follow some of the basic principles of modern policing as articulated by Sir Robert Peel when the London Metropolitan Police Force was created in 1829. In terms of legitimacy, the Peelian principles emphasized the importance of “policing by consent” and gaining the public’s respect by minimizing use of force and arrests and maximizing crime prevention. That has not happened. Consequently, we have seen a rapid growth in publications that criticize police militarization and police violence, such as Rise of the Warrior Cop (Balko, Reference Balko2014), Our Enemies in Blue (Williams, Reference Williams2015), Police State (Spence, Reference Spence2015), and many others. Public dissatisfaction with police performance has also resulted in calls to “defund” and even “abolish” the police among social justice advocates (Purnell, Reference Purnell2021).

The costs of police misconduct and biased enforcement against vulnerable members have been significant, including the adverse effects of investigatory stops, use of force, arrests, and general mistreatment of the public. This has resulted in anti-police movements, as well as negative effects on public safety, officer safety, and taxpayers.

To deter future crime, we want the police to enforce the law, but as Lum and Nagin (Reference Lum, Nagin, Tonry and Nagin2017, p. 344) point out, “arrests are costly to all involved – the police who make them, the public who must pay for the ensuing punishment, and the individual who must endure that punishment.” Local and county law enforcement cost taxpayers roughly $100 billion per year (Buehler, Reference Buehler2021). However, that figure does not include the cost of human life or police misconduct lawsuits. In the United States, there are more than 1,000 fatal police shootings each year (Washington Post, 2024), and lawsuits cost taxpayers billions of dollars in misconduct settlements (Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Rich and Thacker2022).

Aggressive policing and misconduct are not only financially expensive – they are also costly in terms of police legitimacy and public safety. As discussed in this Element, when the public does not view the police as legitimate authority figures who “do the right thing,” a number of adverse consequences occur, and these effects can undermine public safety.

3.1 Bias Against Vulnerable Groups

I am most concerned about the unconstitutional treatment of the vulnerable classes. The 14th Amendment of the US Constitution guarantees “due process” and “equal protection” of the law for all groups, including those defined by race, color, sex, gender identity, age, religion, mental health, disability, national origin, sexual orientation, and other at-risk groups. Clearly, not all Americans are treated equally by the police. Today, police critics are insisting on fairer and more respectful treatment of vulnerable, constitutionally protected classes. Mistreatment has been highlighted recently in our national dialogue, so we must understand better how these vulnerable groups are being treated and what can be done to improve the police services they receive.

The history of racism in American is well documented in classic works such as The Souls of Black Folk (Du Bois, Reference Du Bois1903), The Nature of Prejudice (Allport, Reference Allport1954), and The Warmth of Other Suns (Wilkerson, Reference Wilkerson2011). Racial bias during enforcement is nothing new and is also well documented. The National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorder (1968) – called the Kerner Commission – attributed the national race riots of 1967 to white racism and blamed police mistreatment of Black Americans as the spark that started the riots. The Commission recommended that agencies “[r]eview police operations in the ghetto to ensure proper conduct by police officers, and eliminate abrasive practices” (p. 8). In the context of racial inequality and poverty and growing frustration and anger over discrimination, white officers making arrests and engaging in brutality against Black community members was enough to trigger numerous protests and riots (Evans, Reference Evans2021). The reports from multiple commissions, beginning with the 1919 Chicago riots, all reached a similar conclusion.

The problem of racial discrimination by the police has continued in recent decades. Racial profiling and violations of civil liberties during the drug war in the 1980s and 1990s contributed significantly to the problem of disproportionate arrest and incarceration of Black community members (Rosenbaum, Reference Rosenbaum, Davis, Lurigio and Rosenbaum1993). The incidents of extreme police violence against Black people that have resulted in protests over the past sixty years do not capture the widespread nature of the problem today. National data collected through the Police-Public Contact Survey have consistently revealed that Blacks and Hispanics are more likely than whites to experience either the threat of force or actual force during their contact with the police, more likely to receive enforcement actions, and more likely to feel that the officer engaged in misconduct, such as slurs, bias, or sexual misbehavior (Harrell & Davis, Reference Harrell and Davis2020; Tapp & Davis, Reference Tapp and Davis2022).

A meta-analysis of twenty-seven separate datasets shows clearly that suspects of color have been arrested at higher rates than white suspects (Kochel et al., Reference Kochel, Wilson and Mastrofski2011). Furthermore, Black and Hispanic community members are shot and killed by the police at a much higher rate than white community members (Washington Post, 2024). Even when guns are not used, an analysis of 1,000 deaths shows that Black persons, who comprise 12 percent of the US population, represented one-third of all deaths involving physical force by the police across many cities (Dunklin et al., Reference Dunklin, Foley and Martin2024).

Some have argued that the racial disparities in enforcement are largely the result of the concentration of crime in low-income neighborhoods where people of color are overrepresented rather than expressions of racial prejudice by the police (Engel & Swartz, Reference Engel, Swartz, Bucerius and Tonry2014). Taking a longitudinal look at the criminal histories of roughly 1,000 youth over time, Sampson and Neil (Reference Sampson and Neil2024) conclude that persistent racial disparities in arrest rates can be attributed to “concentrated and cumulative forms of neighborhood disadvantages and advantages that are spatially concentrated” (p. 198). Clearly, higher crime rates in underresourced communities has resulted in more concentrated policing and arrests, regardless of whether the arrestees have a history of criminality or the police are expressing racial bias. However, for this Element, my point is that the methods of aggressive policing are real and enforcement is problematic regardless of the cause.

There are long-term consequences of enforcement. In addition to death or injury, police enforcement over time has resulted in the mass incarceration of Black people (Alexander, Reference Alexander2011). Critics have also argued that the criminal justice system, including arrest and sentencing disparities, reinforces a caste system of racial control that produces second-class citizens with fewer rights (Alexander, Reference Alexander2011; Lerman & Weaver, Reference Lerman and Weaver2014). There is also an extensive literature on the numerous collateral consequences of involvement in the justice system, especially the adverse effects of monetary sanctions, which are most detrimental to disadvantaged populations and can contribute to re-offending as they accumulate (See Ostermann et al., Reference Ostermann, Link and Hyatt2024, for a review).

Police traffic stops offer the best example of how police enforcement has adverse effects on vulnerable populations. American law enforcement has placed enormous emphasis on “stop and frisk” as a tool for fighting crime (Meares, Reference Meares2014; White & Fradella, Reference White and Fradella2016), but racial disparities in police decision-making during traffic stops have been documented repeatedly across dozens of agencies. Black drivers are stopped more often, stopped more often for nonsafety reasons (“pretextual stops”), searched more often, and subjected to force more often than white drivers (Graham, Reference Graham2024; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Neath and Buchanan2024; Langton & Durose, Reference Langton and Durose2013; Pierson et al., Reference Pierson, Simoiu and Overgoor2020). Young Black and Hispanic males are particularly at risk of citations, searches, arrests, and use of force (Engel & Calnon, Reference Engel and Calnon2004). We must also recognize that traffic stops can be costly in other ways, such as the price of fines, fees, court summons, and incarceration, which can contribute to poverty (Alabama Appleseed Center for Law & Justice, 2023). Thus, the Center for Policing Equity has emphasized that the effects of police stops are compounding as “disparities at each step increase the risks of harm at subsequent decision points” (Graham, Reference Graham2024, p. 1).

As a psychologist, I would like to underscore the fact that investigatory stops are embarrassing and upsetting for the drivers, who are often questioned and searched in front of family members, friends, or bystanders. As Epp and his colleagues (Reference Epp, Maynard-Moody and Haider-Markel2014) document, drivers are often asked where they are going, why they need to go there, and what they are carrying in their glove compartment or trunk. Flashlights run through the windows in every conceivable section; people are asked to get out; personal items are strewn on the ground nearby. The psychological impact can be enormous, resulting in resentment, loss of trust, and growing anger toward the police, especially in communities of color.

In general, we now know from research that contact with the police can have adverse mental health consequences, especially for people of color, youth, and transgender populations (DeVylder et al., Reference DeVylder, Oh and Nam2017). Police enforcement actions can have a range of adverse effects on youth, including increased school absenteeism (Geller & Mark, Reference Geller and Mark2022), increased recidivism (Klein, Reference Klein1986), and reduced options for gainful employment (Bushway, Reference Bushway1996). These effects are especially large for young Black males, as they tend to be heavily policed, and thus hold very negative views of the police (Gau & Brunson, Reference Gau and Brunson2010; Geller, Reference Geller2021; Suddler, Reference Suddler2019). The negative perceptions in the Black community are the result of both direct contact with the police (Tapp & Davis, Reference Tapp and Davis2022), and vicarious experience, such as conversations among friends and family (Rosenbaum et al., Reference Rosenbaum, Schuck, Costello, Hawkins and Ring2005).

Poor communities of color have long been the focus of police intrusion in large cities, as police seek to reduce crime. Unfortunately, we have known for half a century that police work often involves officers seeking to confirm their prejudicial suspicions about criminality (Rubinstein, Reference Rubinstein1973) and create a case of probable cause and enforcement using their own set of rules (Skolnick, Reference Skolnick1975). Police are usually interacting with complete strangers, and in these settings, human beings feel a need to make snap judgments based on limited information – judgments that are often inaccurate (Gladwell, Reference Gladwell2005). In general, people tend to attribute certain attitudes, beliefs, and behavioral traits to strangers (Baum et al., Reference Baum, Fisher and Singer1985), and this prejudice can lead to discrimination. For decades, psychologists have studied how we enhance our self-identity and preserve the status quo by using social stereotypes that emphasize the positive attributes of our “ingroup” while devaluing the attributes of the “outgroup” (Allport, Reference Allport1954; McGarty et al., Reference McGarty, Yzerbyt and Spears2002; Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979). Today, we distinguish between “explicit” and “implicit” bias, with the understanding that all humans suffer from implicit bias that can lead to discrimination, and the police are no exception (see Fridell, Reference Fridell, Lynch, Patterson and Childs2008, Reference Fridell2017).

Today, with the increased polarization of political attitudes (Edsall, Reference Edsall2024), I am concerned about the national rise in expressions of prejudice toward outgroups and how this trend might affect police-community interactions. For example, we see a nationwide effort to abolish diversity, equity, and inclusion (D.E.I.) programs in education, as well as a broader anti-“wokeism” movement – organized efforts that run counter to social justice for all vulnerable groups (see Confessore, Reference Confessore2024). With the rise of homophobia, transphobia, antisemitism, xenophobia (around immigration), and other forms of prejudice, we must remember that police officers are susceptible to these attitudes as well. A study of 220,000 officers from 98 of the 100 largest local agencies found that police officers tend to be more conservative than the civilians they serve (Ba et al., Reference Ba, Kaplan, Knox, Komisarchik and Lanzalotto2023). Thus, those interested in changing police culture should be prepared for some backlash, such as the “Blue Lives Matter” movement, as well as the possibility of additional forms of discrimination.

Thus, to better understand the needs of all vulnerable and constitutionally protected classes, we need to consistently create space for them to voice their concerns and be prepared to hear about their interactions with the police. Furthermore, the community wants evidence that progress is being made to reduce these problems, as too much ambiguity remains about how to measure progress. Here, I will argue that, in the interest of impartial policing and transparency, cities should collect and publicize data on the quality of police services, with breakdowns by the demographic characteristics of the community members being served.

3.2 The Cost to Police Officers

My criticism here is focused largely on the failure of police reform, not on the majority of police officers who are simply trying to do a difficult job within their existing organizational structure. After four decades of observation, I fully understand that police work can be very difficult and it is made more difficult today because of the public outcry and calls for greater police accountability. On the job, officers can face violent and traumatic incidents that are hard to forget, from homicides to traffic fatalities to suicides. As a group, police officers are more likely to commit suicide than die on the job (Stanton, Reference Stanton2022), and they have a suicide rate higher than civilians (McAward, Reference McAward2022). The national trend to introduce officer wellness programs (U.S. Department of Justice, 2024) is a clear indication of the stressfulness of police work. Hopefully, the new management model proposed here will help to reduce some of the stress of police work.

4 The Ineffectiveness of Police Reform

From crime commissions to consent decrees, the United States has sought to increase police accountability and transparency for nearly a century. Some improvements have been noted (Skogan & Frydl, Reference Skogan and Frydl2004), but the general mistreatment of the public remains problematic. We have summarized the problem in one sentence: “American policing progressed from an unregulated politicized entity that eventually enforced ‘Jim Crow’ laws to an organized, quasi-military bureaucracy focused on law enforcement” (Rosenbaum & McCarty, Reference Rosenbaum and McCarty2017, p. 71).

The reforms led by August Vollmer and O. W. Wilson in the twentieth century were designed to insulate the police from long-standing corruption and improve effectiveness in fighting crime. I have summarized the professional model of policing in this way: “Uniforms, military ranks, written policies and procedures, centralized control and command, highly trained specialized units (including detectives), motorized patrols, and modern technology were expected to eliminate corruption, professionalize the police, and above all, prevent crime through rapid response, random patrol, and forensic investigations” (Rosenbaum, Reference Rosenbaum2007, p. 14). This professional model seems to have reduced corruption, but has been ineffective in fighting crime or building police legitimacy. Within this framework, police organizations have used symbols, dress, and ceremonies to maintain their legitimacy and promote their image and values as fair, professional crime fighters (Crank & Langworthy, Reference Crank and Langworthy1992; Gau, Reference Gau2014). However, as Gau (Reference Gau2014) notes, these images and values “are decoupled from task performance,” and thus are essentially myths created to ensure police legitimacy.

In fact, this detached, quasi-military model of policing has contributed directly to the crisis of legitimacy that continues to fester. From Rodney King in 1991 to Tyre Nichols in 2023, the beatings and deaths have continued and calls for police reform have intensified (e.g., Balko, Reference Balko2014; Morrison et al., Reference Morrison, Lauer and Sainz2023). The typical requests for more “accountability” and “transparency” will be insufficient. I am pleased that the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) has established new guidelines for police use of force, especially when restraining persons who are having a medical, mental, or drug crisis (Seewer & Dunklin, Reference Seewer and Dunklin2024), but I remain skeptical that these guidelines will significantly change behavior on the streets without changes to the police culture and performance standards.

For decades, policing scholars have associated excessive force and mistreatment of the public with this militaristic culture and the war-like mentality used to combat crime and drugs (e.g., Skolnick, Reference Skolnick1975; Skolnick & Fyfe, Reference Skolnick and Fyfe1993). Yes, there are a few rotten apples, but mistreatment of the public by a large segment of the police force is associated with the social norms within the police culture. Psychological and physical training to be a warrior with a “bulletproof mind” is important for surviving in battle (Grossman & Christensen, Reference Grossman and Christensen2008), but the job of police officers is very different. Most police officers never fire their weapon during their entire career and attempts to kill them are extremely rare. Yet the training for new police recruits in the United States exposes them to videos showing officers being ambushed or killed during traffic stops (Kirkpatrick et al., Reference Kirkpatrick, Eder, Barker and Tate2021), reinforcing the mindset of being hypervigilant and suspicious of everyone they encounter. Academy evaluations with pretests and posttests have shown that recruits develop a significantly greater desire to use physical force to solve problems and have less respect toward the community after six months of training (Rosenbaum & Lawrence, Reference Rosenbaum and Lawrence2017). Another pre–post study found that recruits become more inclined to believe that police misconduct and the code of silence are less serious problems after academy training (Schuck & Rabe-Hemp, Reference Schuck and Rabe-Hemp2021). Thus, from the start, the socialization process strengthens their cultural identity as tough warriors who must be on guard against hostile community members, demand obedience, use force to solve problems, and maintain secrecy within the group. Too often, this socialization process undermines, rather than builds, community trust.

Thus, police reform must directly confront this culture and style of policing to achieve widespread public trust. In this Element, I argue that the focus and priorities of police organizations must change. Lum and Nagin (Reference Lum, Nagin, Tonry and Nagin2017) make a compelling case that policing in a democratic society should be built on two basic principles. The first is that crime prevention should be prioritized over arrests, consistent with Peelian principles. The second is that “citizens’ views about the police and their tactics for preventing crime and disorder matter independently of police effectiveness” (p. 339). The authors contend that these two principles are equally important and “neither has standing to trump the other.” Consistent with Lum and Nagin’s conclusion, I am calling on reformers and police researchers to acknowledge the importance of public perceptions of the police and do something about it to advance knowledge and “evidence-based policing” (cf. Sherman, Reference Sherman and Tonry2013). My position is also consistent with Klose’s (Reference Klose2024) revised definition of evidence-based policing that includes “community values, preferences, and circumstances” in the decision-making process.

Since the 1980s, there have been many reforms and innovations in policing (Rosenbaum, Reference Rosenbaum2007). Most of these reforms have been ineffective and some even harmful. I will give some attention to reforms that are relevant to the organizational and research agenda proposed here, seeking to give more attention to policing processes rather than policing outcomes, although the two can be, and should be, connected.

Since the death of George Floyd, there have been nearly 300 state laws that seek to reform the police in various ways, including more civilian oversight, limitations on use of force, anti-bias training, and alternatives to arrest in mental health cases (Monnay, Reference Monnay2022). There has been considerable pushback by law enforcement personnel against these changes, and the general focus of these reforms is the misuse of force, not other police-public interactions.

4.1 Police Accountability and Public Safety

Individual cities have tried to control behavior through discipline and even firing officers for misconduct, but with little success. For most agencies, less than 10 percent of the misconduct complaints are investigated (Kelly & Nichols, Reference Kelly and Nichols2020). The cases investigated by Internal Affairs are usually cleared and police reports often lack important details. When deaths are involved, officers are usually exonerated by reports from medical examiners and coroners (Dunklin et al., Reference Dunklin, Foley and Martin2024). When punishments are recommended, strong union contracts allow appeals to arbitration, which rarely result in sanctions. In one New York Times review, roughly half of the fired officers were reinstated (Barker et al., Reference Barker, Keller and Eder2021). Even most police officers agree that accountability systems are not working. In our national survey of more than 13,000 police officers in 89 large agencies, only 1 in 5 officers felt that “officers who do a poor job are held accountable” (Cordner, Reference Cordner2017). With qualified immunity, police officers are not financially responsible for their misconduct (Yancey-Bragg, Reference Yancey-Bragg2023). Furthermore, thousands of officers who have been fired by one agency are rehired by another, as decertification systems are rarely in place (Stecklow, Reference Stecklow2024).

Although ineffective, this entire process, including public outcry, leaves many officers feeling mistreated, which affects their work-related attitudes and behavior. Our national survey found that when officers are upset about organizational injustice, such as unfair discipline, they are less committed to organizational goals, express less job satisfaction, and are less willing to comply with agency rules (Rosenbaum & McCarty, Reference Rosenbaum and McCarty2017). In the larger context of anti-police sentiment in the media and public protests, many police officers have become demoralized (Bello, Reference Bello2014). In a national survey, police officers expressed anger toward the public and fear of being unfairly disciplined or fired (Pew Research Center, 2017). These sentiments resulted in significant “de-policing” after the George Floyd protests in 2020 (Nix et al., Reference Nix, Huff, Wolfe, Pyrooz and Mourtgos2024). Today, many police prefer to “lay low” and avoid unnecessary risks, which can reduce public safety. For example, in New Jersey, a huge drop in traffic-related citations by the state police (due to criticism of their agency) was followed by a dramatic increase in traffic accidents (Tully, Reference Tully2024). Thus, we can see how police behavior and public safety can be negatively influenced when reforms are not handled properly. Later, I will revisit the issue of police effectiveness in fighting crime.

The complaints filed by community members provide insight into police-public interactions and how these encounters can escalate. One of the most common complaints is that the officer was discourteous, including used offensive language (e.g., Seron et al., Reference Seron, Periera and Kovath2006; Terrill and Reisig, Reference Terrill and Reisig2003). But as Seron and colleagues (Reference Seron, Periera and Kovath2006) note after reviewing complaints against the New York Police, “alleged misconduct often escalates into behavior that is asserted as having been abusive or unnecessarily forceful” (p. 928). This might include verbally threatening civilians or using force ranging from pushing to beating. Research has shown that police respond in a punitive manner when civilians fail to comply or are judged to be disrespectful of police authority (Klinger, Reference Klinger1997; Mastrofski et al., Reference Mastrofski, Reisig and McCluskey2002; Worden & Shepard, Reference Worden and Shepard1996). The real problem is that, aside from these few studies, we know very little about what transpires during daily police-public encounters in American cities. Here I propose to fix this problem.

After negative media coverage of deadly force incidents, many police agencies have tried to increase accountability by changing their use of force policies, conducting more thorough internal investigations of these incidents, creating early intervention systems (EIS) to identify officers at risk, and offering new training on when force is appropriate. While these reforms have been helpful in some ways (see Walker & Archbold, Reference Walker and Archbold2020), they have serious limitations. There are many reasons why these internal changes have had limited impact on street-level policing and public trust, including internal resistance to change, a lack of expertise needed to analyze data, deficiencies in data quality, lack of objectivity when evaluating other officers, weak training, and administrative turnover.

Early intervention systems (EIS) programs are now popular and have potential for identifying and intervening with officers who are at risk of misconduct (Walker & Archbold, Reference Walker and Archbold2020). However, we do not have a standard set of metrics to define “at risk,” and those currently used are not good predictors of problematic behaviors (Russek & Fitzpatrick, Reference Russek and Fitzpatrick2021; Worden et al., Reference Worden, Harris and McLean2014). As La Vigne (Reference La Vigne2022) notes, even if EIS uses fancy algorithms to identify patterns, relying on existing police records will lead to “garbage in, garbage out.” My own experience as a consent decree monitor suggests that EIS personnel are forced to rely on their own judgment or “rules of thumb” rather than “predictive analytics.” Also, supervisors are often free to do whatever they want to satisfy the requirements of an EIS intervention. Often, they do very little beyond having a brief talk with the officer.

I want to point out that focusing on the behavior of a few “rotten apples” doesn’t help us understand the problematic behavior patterns of a larger segment of the police force as shown in contact surveys. To be clear, excessive force incidents are extremely rare, and minor force incidents often go unreported due to the “code of silence” or they are reported with justification from the officer’s perspective. Furthermore, the civilians who file complaints are not representative of the much larger group of unhappy service recipients who are afraid of police retaliation. Thus, a much broader set of performance metrics with predictive validity is needed, including metrics that give greater voice to the community and metrics that rely on indisputable video data.

Existing training is also problematic for police reform. More than a half century ago, following the crisis of legitimacy in the 1960s, psychologists were critical of the standard police training programs and proposed an approach that would focus on “basic skills of being helpful to another” (Danish & Ferguson, Reference Danish, Ferguson, Snibbe and Snibbe1973, p. 499), but little progress followed. Today, a few hours of classroom training on de-escalation and proper communication is a drop in the bucket. A nationwide survey found that recruits in state and local law enforcement training academies receive an average of 168 hours of training on firearms, self-defense, and use of force, compared to only 10 hours on communication and 8 hours on ethics and integrity (Reaves, Reference Reaves2016). In addition to a stronger “dosage” of training on these topics, we need new community-based metrics to assess the impact of training on job performance.

Performance evaluations conducted by supervisors are also problematic and lack credibility. Researchers have recommended ways to improve performance evaluations (e.g., Oettmeier & Wycoff, Reference Oettmeier and Wycoff1997), but the reality is that police work is largely unsupervised. Supervisors are rarely present during most police encounters with the public, and with new BWC data, a few agencies are requiring supervisors to review only a small and unrepresentative sample of footage. Also, performance is difficult to evaluate with existing police records, which have little to do with the quality of police service overall and are based on selective community complaints and use of force incidents. Even when agencies require supervisors to evaluate the quality of police service by individual officers, the results are not credible without observational data to validate these judgments. Furthermore, for decades, the police culture has encouraged supervisors to be loyal to their officers (Engel, Reference Engel2001) and protect them from criticism by headquarters (Skolnick & Fyfe, Reference Skolnick and Fyfe1993). For example, after reviewing more than 2,000 ratings of performance in one large police department, I discovered that supervisors never once gave a rating of “Needs Improvement” on any of the dozens of performance metrics. How are officers supposed to improve their performance if they don’t receive any helpful feedback? Anecdotally, I have asked many officers today how they are evaluated, and the typical response is “Whether I can stay out of trouble.”

External civilian oversight and auditing have been recommended for years (Mastrofski, Reference Mastrofski1999; Reiss, Reference Reiss1971), and have potential, but they are usually opposed by the police and lack critical data needed to accurately evaluate police performance (Walker & Archbold, Reference Walker and Archbold2020). Also, the composition and expertise of these groups is sometimes questionable. Nevertheless, civilian oversight is needed in some capacity, as articulated in this publication.

Beginning in the 1990s, consent decrees by the US Department of Justice have required that police agencies correct a “pattern or practice” of unconstitutional policing against protected groups. While these legal agreements have resulted in some improvements to policies and training regarding the use of force in more than forty agencies involved (US Department of Justice, 2017; Lawrence & Cole, Reference Lawrence and Cole2019; Walker, Reference Walker2017), thousands of police agencies without consent decrees are not required to make these changes. Sometimes, the force training involves teaching officers to include in their force reports that “I feared for my life.” These consent decrees are not only very costly but they are also slow to get started and typically drag on for years because of failure to comply fully with the terms of the agreement (Ravani, Reference Ravani2022) or because of local opposition and national politics (Lynch & Goudsward, Reference Lynch and Goudsward2024). Reaching beyond the focus of consent decrees, here I will emphasize the need for additional changes in accountability and performance assessments that have a better chance of influencing police behavior on the street and thus enhancing police legitimacy.

4.2 Key Innovations in Policing

Various innovations have been proposed to either fight crime more effectively and/or enhance police legitimacy. Most police work since the 1960s has been reactive, namely, responding to calls, taking reports and conducting investigations of crimes already committed. However, since the 1980s, innovation in policing has transitioned to more proactive attempts to prevent crime and engage the community. Here I take a quick look at some of the main strategies and why they have largely failed to change the style of policing or the police culture.

4.2.1 Community Policing

Many reform efforts were introduced in the 1980s to address the legitimacy problem through community engagement and community policing (Cordner, Reference Cordner, Alpert and Piquero1997; Green & Mastrofski, Reference Green and Mastrofski1988; Rosenbaum, Reference Rosenbaum1988, Reference Rosenbaum1994; Skogan & Hartnett, Reference Skogan and Hartnett1997). Community policing remains very popular, but the obstacles to full-scale implementation have been numerous (see Fridell & Wycoff, Reference Fridell and Wycoff2004; Mirzer, Reference Mirzer1996; Skogan, Reference Skogan2003). Community policing initiatives were conceived primarily as community relations programs to demonstrate police interest in community concerns, but they were never fully integrated into the daily practice of policing. Furthermore, observational studies in Chicago (Skogan & Hartnett, Reference Skogan and Hartnett1997), Seattle (Lyons, Reference Lyons1999), and Los Angeles (Gascon & Roussell, Reference Gascon and Roussell2019) have documented how these programs can be insensitive to many of the concerns raised by community members. Although community policing programs remain very popular, neither the structure nor the function of American police organizations has changed significantly as a result of these initiatives (Maguire, Reference Maguire1997; Mastrofski, Reference Mastrofski, Weisburd and Braga2019).

4.2.2 Problem-Oriented Policing

Also emerging in the 1980s was problem-oriented policing (POP), pioneered by Herman Goldstein (Reference Goldstein1979, Reference Goldstein1990). Goldstein argued that the time has come for police to focus on solving crime-related problems and addressing their causes, rather than being obsessed with incident-driven, law enforcement actions such as making arrests. Eck and Spelman (Reference Eck and Spelman1987) articulated a four-step process to implement POP called the SARA model (Scanning to identify the problem, Analysis to collect information about the problem, Response to implement solutions, and Assessment to evaluate effectiveness). Problem-oriented policing was a great idea, but the management structure did not change to support this approach to policing. As Braga and Weisburd (Reference Braga, Weisburd, Weisburd and Braga2019) note, “it seems unrealistic to expect line-level officers to conduct in-depth problem-oriented policing” (p. 198) without the support of researchers and administrators. Furthermore, POP has focused on reducing crime and disorder problems, but rarely other problems that concern the community. Nevertheless, the most rigorous evaluations suggest that intensive POP with full organizational support can produce short-term reductions in crime and disorder (Hinkle et al., Reference Hinkle, Weisburd, Telep and Petersen2020; Weisburd & Majmundar, Reference Weisburd and Majmundar2018). In the present context, however, POP has failed to address the problem of public anger and distrust of the police, and police agencies have failed to adequately seek or respond to community feedback on this issue. Nevertheless, I see the SARA model as very applicable to the organizational changes outlined in Section 7.2.3, with the goal of increasing police legitimacy.

4.2.3 Information Technology and Outcome-Based Policing

Policing in the twenty-first century can be viewed as “the Information Technology era” (Rosenbaum, Reference Rosenbaum2007) because of the focus on geo-based crime-fighting and the surveillance of suspects with the aid of computers. Multiple technologies are being used to predict and fight crime, including body-worn cameras (BWCs), data mining systems, heat sensors, biometrics, nonlethal weapons, GPS tracking, electronic monitoring, telecommunication systems, Internet searches, facial recognition software, drones, and data analytics with artificial intelligence.

The public has complained about secrecy and the lack of transparency in police work for many years. Body-worn cameras represent a significant attempt to address this concern using technology (White, Reference White2014), allowing us to see what happens during police-public encounters. However, a large body of research has failed to identify stable effects of BWCs on the behavior of police officers or community members, with the exception of a reduction in community complaints (Lum et al., Reference Lum, Stoltz, Koper and Scherer2019, Reference Lum, Koper and Wilson2020). Furthermore, the original BWC goals of transparency and accountability have not been achieved at the organizational level. Videos tend to be reviewed by Internal Affairs only when an incident involves a serious public complaint, high level of use of force, or an officer-involved shooting – estimated at less than 1 percent of all encounters. For the other 99 percent, the millions of hours of BWC footage remain untouched.

However, BWC data have changed the ball game by introducing a totally new source of evidence about what transpired during police-public encounters. As I will stress in this publication, BWC data has great potential for identifying patterns of behavior that contribute to, or undermine, public trust and confidence in the police. Such data can also be used to understand why force or violence occurs in some face-to-face interactions, but not in others.

One of the original pillars of the information technology revolution was CompStat, introduced in the New York Police Department in 1994 (Bratton, Reference Bratton and Langworthy1999; Walsh, Reference Walsh2001). With computers used to analyze crime patterns, New York’s CompStat model became extremely popular. Arguably, this was the first time that police managers were held accountable for performance on the street, but unfortunately, it encouraged an increase in traditional methods of aggressive, reactive policing to improve the crime statistics in each district. It also encouraged a punitive environment within the organization, which encouraged dishonesty in reporting performance data. Most importantly, CompStat systems failed to gauge in any meaningful way the quality of policing – only the volume of law enforcement activities and crime statistics for large geographic areas.

Given the calls for greater transparency and community voice in policing, the Vera Institute and the National Policing Institute sought to upgrade the CompStat model with a national conference in 2016 and a series of papers to follow in 2018 (Shah et al., Reference Shah, Burch and Neusteter2018). Acknowledging the original criticism of CompStat (e.g., Willis et al., Reference Willis, Mastrofski and Kochel2010), the recommendations for “CompStat 2.0” sought to incorporate community policing (with regular meetings between the police and community stakeholders), incorporate problem-oriented policing (with a broader focus on identifying and addressing local problems), and expand performance measures beyond crime statistics to problem-solving. Unfortunately, the quality of police services and the treatment of individual community members by the police was not given much attention.

Since the 1990s, other police innovations have since competed for dominance, including broken windows policing, hot spots policing, pulling levers policing, predictive policing, and specialty unit policing, with most of these aided by advances in information technology to target geo-based hot spots of crime and disorder or individuals (see Weisburd & Braga, Reference Weisburd and Braga2006). Controlled experiments have taught us that hot spots policing is one of the few policing strategies that is effective in reducing crime (Braga et al., Reference Braga, Turchan, Papachristos and Hureau2019; Weisburd & Braga, Reference Weisburd, Braga, Weisburd and Braga2019; Weisburd & Eck, Reference Weisburd and Eck2017), at least for short periods of time. However, I have argued that this wave of geo-targeted policing strategies tends to be aggressive and inequitable as practiced by most police agencies (Rosenbaum, Reference Rosenbaum, Davis, Lurigio and Rosenbaum1993, Reference Rosenbaum2007, Reference Rosenbaum, Weisburd and Braga2019). A recent National Academies (2025) workshop on the use of predictive policing approaches cautioned police regarding the potential risk of disparate impact and violations of civil liberties, and the need for a more holistic approach that gives attention to community trust as well as crime reduction.

Because of the focus on aggressive enforcement, these “outcome-based performance models” are more likely to undermine public trust in the police, especially in minority and marginalized communities, than “process-based policing models” (Tyler, 2005). Hence, this Element focuses on advancing knowledge and practice of process-based policing, and, where appropriate, linking it to outcome-based policing models, as Weisburd and his colleagues have done (Weisburd et al., Reference Weisburd, Telep and Vovak2022).

4.2.4 Traffic Stops and Public Safety

Since the late 1990s, American police organizations have believed that stopping, questioning, and frisking (SQF) individuals is the most effective method of achieving their primary goal of reducing crime. If weapons, drugs, and other contraband can be recovered and criminals can be stopped and arrested, this will reduce crime (For details on these tactics, see Remsberg, Reference Remsberg1995). However, the widespread adoption of this proactive enforcement strategy stems, in large part, from a misinterpretation of research on hot spots policing, where studies found that such police interventions can be effective in reducing crime when applied to very small geographic areas or “hot spots” (Weisburd & Braga, Reference Weisburd, Braga, Weisburd and Braga2019; Weisburd & Eck, Reference Weisburd and Eck2017). The success of the pioneering Kansas City Gun Experiment (Sherman & Weisburd, Reference Sherman and Weisburd1995), with four officers intensely producing stops, citations, and arrests on specific street segments of one district, received widespread attention. As a result, many police organizations dramatically increased stops in entire neighborhoods, precincts, or large areas – a bad translation of evidence-based policing and one that leads to many good people feeling harassed by intrusive police tactics. In the United States, we have reached a point where police make roughly 50,000 traffic stops per day or 20 million per year (Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, Epp and Shoub2018).

Many of these stops are “pretextual stops” for minor violations, such as a broken taillight or tinted windows, which are employed to ask additional questions and make observations to justify a search of the vehicle or person for evidence of criminal activity (Graham, Reference Graham2024). These investigatory stops require “reasonable suspicion” that the person has committed or is in the process of committing a crime. However, research clearly indicates that (1) these stops are more common and include more enforcement against Black drivers (Graham, Reference Graham2024; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Neath and Buchanan2024; Langton & Durose, Reference Langton and Durose2013; Pierson et al., Reference Pierson, Simoiu and Overgoor2020); (2) “reasonable suspicion” is often lacking before the search is conducted (Skogan, Reference Skogan2023); (3) hit rates for finding contraband are very low and officers are less likely to seize contraband from Black drivers than white drivers (e.g., Engel & Calnon, Reference Engel and Calnon2004; Lofstrom et al., Reference Lofstrom, Hayes, Martin and Premkumar2022; Pierson et al., Reference Pierson, Simoiu and Overgoor2020; Weiss & Rosenbaum, Reference Weiss and Rosenbaum2009); (4) mental and physical health effects on community members can be substantial (as noted earlier); and, perhaps most importantly, (5) traffic stops are ineffective at controlling crime, whether conducted in the United States (McCann, Reference McCann2023) or England and Wales (Tiratelli et al., Reference Tiratelli, Quinton and Bradford2018), and thus waste substantial police resources that could be devoted to other crime-fighting methods.

Gladwell (Reference Gladwell2019) illustrates this last point very clearly using the North Carolina State Highway Patrol as an example. Learning of this new approach to fighting crime, the agency increased its traffic stops from 400,000 to 800,000 over seven years. Gladwell reports that 400,000 searches resulted in only 17 cases where guns or drugs were recovered, begging the question, “[i]s it really worth alienating and stigmatizing 399,983 [drivers] … to find 17 bad apples?” (p. 337). Thus, these pretextual stops rarely produce anything that could be helpful in solving crimes and most are irrelevant to traffic safety. Stops for speeding, drunk driving, or running traffic lights would be a much better use of officers’ time, or devoting these hours to more effective crime prevention work. In fact, unarmed drivers who are not being pursued for a violent crime are killed at a rate of more than one per week (Kirkpatrick et al., Reference Kirkpatrick, Eder, Barker and Tate2021).

The damage to police image can be consequential. The national contact survey shows that Black and Hispanic drivers are less likely than whites to believe that the reason for their stop was legitimate (Langton & Durose, Reference Langton and Durose2013). This perceived lack of fairness can place an upper limit on the level of cooperation and compliance that can be expected from the public, which, in turn, has serious consequences for public safety. Consistent harassment and perceived lack of fairness can contribute to legal cynicism in the community (Kirk & Papachristos, Reference Kirk and Papachristos2011), which can undermine public safety. Thus, we need to systematically measure how vulnerable groups feel about their encounters.

Pedestrian stops are also controversial. These proactive crime control programs have stimulated an important debate among academics about the costs and benefits of the common policing tactic of SQF when applied to pedestrians (Ratcliffe et al., Reference Ratcliffe, Braga, Nagin, Webster and Weisburd2024). Some argue it should be used only to reduce gun violence in high-crime neighborhoods, but these tend to be neighborhoods of color (Kegler et al., Reference Kegler, Simon and Sumner2023). Weisburd and his colleagues (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Weisburd, Fay, Eggins and Mazerolle2023; Weisburd et al., Reference Weisburd, Petersen and Fay2023) conducted a Campell Collaborative Systematic Review of pedestrian stops. While these SQFs reduced crime (roughly 13 percent), they also were associated with mental and physical harm to the community members who were stopped, as well as more negative views of the police and increased delinquency. Consequently, the authors of the review concluded that “existing scientific evidence does not support the widespread use of SQFs as a proactive policing strategy” (p. 2). The concerns about SQFs, including adverse legitimacy effects, not only suggest the need for more dialogue with the community about SQF tactics (see Sherman, Reference Sherman2023) but also underscores the need for new systems of measurement that will allow researchers to monitor the impact of policing practices.

4.2.5 Responding to Persons with Mental Illness

In response to police killing or mistreating persons suffering from mental illness, many police departments have introduced training programs for officers. Crisis Intervention Teams (CIT), based on the 1988 “Memphis Model,” have spread rapidly across the United States, with some good police training to de-escalate tension with individuals facing a mental health crisis (Watson et al., Reference Watson, Compton and Pope2019). However, management has inadequate mechanisms in place to ensure that the behaviors being recommended in training have translated into street-level behaviors. Even the Memphis Police Department has been accused by the U.S. Department of Justice of unlawfully discriminating against people with behavioral health disabilities (Department of Justice, 2024).

Given the proven danger of armed police responding to mental health crises, we have witnessed a national movement to create community responder programs that employ unarmed public officials to handle nonviolent mental health calls for service (Beckett et al., Reference Beckett, Stuart and Bell2021). I am supportive of these programs, but there is much work to be done to decide which calls they are qualified to handle and how they will interact with the police. One famous policing scholar argued that the primary function of the police is to handle situations that require “coercive force” (Bittner, Reference Bittner1970), that is, when someone needs to be restrained with force or is judged to be a threat to someone else’s safety. However, these are rare calls for service, and the unarmed community responders are not prepared to handle all remaining nonforce incidents. Thus, we still need to more directly address the problem of how to produce a kinder, gentler, and more empathetic response from police officers.

4.3 Summary of Past Reforms

We have witnessed dozens of strategies to reform police organizations over the past century, including one of my favorites, community policing. Unfortunately, these interventions have achieved little success at changing police culture or police behavior on the streets. Despite all the new attention on managing use of force, the number of fatal police shootings continues to increase, reaching a record high of more than 1,200 deaths in 2023 (Washington Post, 2024). Also, the 378 police officers shot in the line of duty in 2023 is the highest in history (National Fraternal Order of Police, 2024).

To make matters worse, the public is both critical of aggressive crime-fighting and, at the same time, asking for more enforcement. This happened in the 1980s with drug enforcement (Rosenbaum, Reference Rosenbaum, Davis, Lurigio and Rosenbaum1993), and is happening again with cities and states returning to “tough on crime” policies and increasing police powers (Hernandez, Reference Hernandez2024), despite overall declines in crime. This includes recriminalizing drug activity in public places, returning to pretextual traffic stops, and arresting the growing homeless population for camping in public spaces (e.g., Hernandez, Reference Hernandez2024; VanSickle, Reference VanSickle2024; Woolington & Lewis, Reference Woolington and Lewis2018).

Unfortunately, the growth in rigid bureaucratic controls and external criticism of the police seems to have increased police solidarity and their psychological distance from the communities they serve. Research on group dynamics reminds us that external threat leads to internal group cohesion (Lang et al., Reference Lang, Xygalatas and Kavanagh2021). Today, we see “de-policing” to “stay out of trouble,” along with negative attitudes toward the community being served.

Here I make the argument that progress in police organizations has been restricted by failure to explore new measures of performance and new methods of accountability that are less punitive, grounded in social science knowledge, and give attention to the community’s voice when evaluating police services.

5 Measuring What Matters to the Community

What do we mean by “good policing?” The police mission is “to serve and protect” and the public would like a better definition of “to serve.” To achieve marked improvements in public satisfaction with police performance, others have joined me in making the argument that performance metrics must be expanded to incorporate new measures of the quality of policing as defined by the community (Engel & Eck, Reference Engel and Eck2015; Langworthy, Reference Langworthy1999; Lum & Nagin, Reference Lum, Nagin, Tonry and Nagin2017; Mastrofski, Reference Mastrofski1999; McCarthy & Rosenbaum, Reference McCarthy and Rosenbaum2015; Moore et al., Reference Moore, Thacher, Dodge and Moore2002). For many years, the limitations of traditional measures of performance have been well documented in the scholarly literature (Alpert & Moore, Reference Alpert, Moore, Alpert and Piquero1993; Blumstein, Reference Blumstein and Langworthy1999; Goldstein, Reference Goldstein1990; Grant & Terry, Reference Grant and Terry2005; Maguire, Reference Maguire2004a; Masterson & Stevens, Reference Masterson, Stevens and Stevens2002; Moore & Poethig, Reference Moore, Poethig and Langworthy1999; Moore et al., Reference Moore, Thacher, Dodge and Moore2002; Reisig, Reference Reisig1999; Skolnick & Fyfe, Reference Skolnick and Fyfe1993; Sparrow, Reference Sparrow2015; White, Reference White2007). Official statistics, such as reported crime rates, clearance rates, citations, arrests, and other enforcement activities, not only suffer from inaccuracy, but more importantly, they provide a very incomplete picture of police work. Within the framework of policing in a democratic society, police scholars and practitioners have called for greater attention to policing processes rather than policing outcomes (Mastrofski, Reference Mastrofski1999; Moore et al., Reference Moore, Thacher, Dodge and Moore2002). Specifically, traditional measures fail to capture what is most important to the public, namely, how they are treated by the police. Thus, policing scholars have called upon the field to “measure what matters” to the community (Dunworth et al., Reference Dunworth, Cordner and Greene2000; Langworthy, Reference Langworthy1999; Masterson & Stevens Reference Masterson, Stevens and Stevens2002; Mastrofski, Reference Mastrofski1999; Rosenbaum, Reference Rosenbaum, Fridell and Wycoff2004). What matters most is procedural justice.

5.1 Procedural Justice

In the pursuit of evidence-based policing, we should use public satisfaction with police encounters, and the sense of procedural justice that drives this satisfaction, as core metrics to define “good policing.” The pioneering work of Tom Tyler and his colleagues (Lind & Tyler, Reference Lind and Tyler1988; Tyler, Reference Tyler1990; Tyler & Huo, Reference Tyler and Huo2002) has paved the way for numerous studies in many countries showing that people’s judgments about the police and police legitimacy are heavily influenced by their sense of whether the process is fair and the officer’s behavior is appropriate (Bradford, Reference Bradford2014; Bradford et al., Reference Bradford, Murphy and Jackson2014; Hough et al., Reference Hough, Jackson, Bradford, Tankebe and Liebling2013; Mazerolle et al., Reference Mazerolle, Sargeant and Cherney2014; Quattlebaum et al., Reference Quattlebaum, Meares and Tyler2018; Tankebe, Reference Tankebe2013; Tyler, Reference Tyler2004; Tyler & Fagan, 2008). Although community residents want safer streets and less violence, most importantly, they want a police force that is fair and sensitive to their needs (Rosenbaum et al., Reference Rosenbaum, Schuck, Costello, Hawkins and Ring2005; Skogan & Frydl, Reference Skogan and Frydl2004; Tyler, Reference Tyler2005; Weitzer & Tuch, Reference Weitzer and Tuch2005).

When evaluating police performance from the public’s perspective, the police response to crime incidents should be placed in the larger context of daily police work. In ten cities examined by the New York Times, serious violent crime comprised only about 1 percent of the calls for service (Asher & Horwitz, Reference Asher and Horwitz2021). In nine cities, the Vera Institute of Justice found that less than 3 percent of all 911 emergency calls involved violent crime situations and only 37 percent involved any type of criminal activity (Dholakia, Reference Dholakia2022). Hence, the detached crime-fighting model has little relevance to the vast majority of calls for service, yet the treatment of the public during these noncrime situations remains very important to their assessment of police legitimacy and public cooperation. For example, the traffic stop is the most common method of police-public contact and, as described earlier, it is a setting where multiple problems can develop regarding fair and respectful treatment.

I will acknowledge here that some policing scholars have debated whether there is a causal link between procedural justice and police legitimacy, given that most studies are correlational and do not involve experimental designs (e.g., Nagin & Telep, Reference Nagin and Telep2017). I acknowledge this issue, but simply point out that procedural justice, legitimacy, and many other human perceptions have been strongly linked in hundreds of studies (for a review, see Tyler & Nobo, Reference Tyler and Nobo2022), and that causality has been demonstrated in one randomized trial (Jonathan-Zamir et al., Reference Jonathan‑Zamir, Perry, Kaplan‑Damary and Weisburd2024). Also, researchers have used a “subjective causality approach” by conducting in-depth interviews of protestors and concluded that the fairness of treatment influences their judgments of police legitimacy and not the reverse (Perry et al., Reference Perry, Jonathan-Zamir, Willis, Weisburd, Jonathan-Zamir, Perry and Hasisi2023).

Another debated issue is whether procedural justice should be given priority over fighting crime. I want to emphasize that this is not a “zero-sum game” or trade-off. We don’t need to pick between procedural justice and public safety, and others agree with me (Engel & Eck, Reference Engel and Eck2015). The police should continue to fight crime but do so in a manner that is less harmful to the community. In addition, we have reason to believe that procedural justice and crime control are connected. We know from many studies that when the police act in a procedurally just manner, the public is more likely to view the police as legitimate and trustworthy (Donner et al., Reference Donner, Maskaly, Fridell and Jennings2015), less cynical about the law (Gau, Reference Gau2015), more likely to obey the law (Tyler, Reference Tyler1990), and more likely to cooperate with the police (Maguire & Lowrey, Reference Maguire and Lowrey2017; Murphy & Cherney, Reference Murphy and Cherney2012; Rosenbaum et al., Reference Rosenbaum, Maskaly and Lawrence2017; Tyler, Reference Tyler2004, Reference Tyler2006). This also means the community is more likely to comply with police requests (Walters & Bolger, Reference Walters and Bolger2018), thus avoiding the need to use force, and is more likely to cooperate by reporting criminal activity (Bolger & Walters, Reference Bolger and Walters2019).

Perhaps the most compelling evidence of the linkage between procedural justice and crime comes from a study by Weisburd and his colleagues (Reference Weisburd, Telep and Vovak2022) in three cities where officers were randomly assigned to hot spots with or without five days of procedural justice training. Officers in the training condition showed more respectful treatment of community members, made fewer arrests, and received fewer perceptions of police harassment and violence than officers in the control group. Most importantly, there was a significant relative 14 percent reduction in crime incidents in the experimental hot spots where officers received the procedural justice training.

Procedurally just behaviors by the police should contribute to more complete and effective investigations of crime due to increased cooperation, thus contributing to deterrence. Also, when the public views the police as trustworthy, they are more likely to exhibit community engagement and collective efficacy (Tyler & Meares, Reference Tyler and Meares2021). A community’s “collective efficacy” and “willingness to intervene” are associated with lower levels of neighborhood violence and less fear of crime (Sampson et al., Reference Sampson, Raudenbush and Earls1997). For these reasons, I have repeatedly encouraged the “co-production” of public safety by engaging community members in crime prevention and multiagency partnerships (Rosenbaum, Reference Rosenbaum1986, Reference Rosenbaum2002; Rosenbaum et al., Reference Rosenbaum, Lurigio and Davis1998; Schuck & Rosenbaum, Reference Schuck, Rosenbaum and Fulbright-Anderson2006).

The police could use more help from the community in fighting crime. Clearance rates are low and have continued to decline over the ten-year period beginning in 2013 (Gramlich, Reference Gramlich2024). Police now clear only 52 percent of homicides, 41 percent of aggravated assaults, and 23 percent of robberies. Clearance rates for rape have declined dramatically from 41 percent to 26 percent during this period. If public trust in the police were higher, we could expect greater public cooperation in solving crime and weaken the “No Snitch” culture present in many high-crime neighborhoods.

For this Element, the key elements of procedural justice need to be defined (for an introduction, see President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, 2015; Rosenbaum et al., Reference Rosenbaum, Maskaly and Lawrence2017; Yale Law School Justice Collaboratory, 2023). Essentially, procedural justice research shows that the public’s perceptions of police are strongly influenced by the quality of their encounter with the police. Tyler and other policing scholars have identified four key components of procedural justice when interacting with the police:

(1) Dignity and Respect: Are community members treated with dignity and respect by the officers?

(2) Voice: Are community members given a voice or chance to express their concerns? Are they allowed to participate in the decision-making process?

(3) Neutrality: Are the officers neutral or unbiased in their decisions, guided by consistent and transparent reasons? Are decisions based on the facts and legal procedures, rather than personal biases about race/ethnicity, gender, age, sexual orientation, mental health, religion, or other factors that are not legally relevant?

(4) Trustworthiness: Are the officers conveying trustworthy motives and showing concern about the well-being of those who are affected by their decisions?

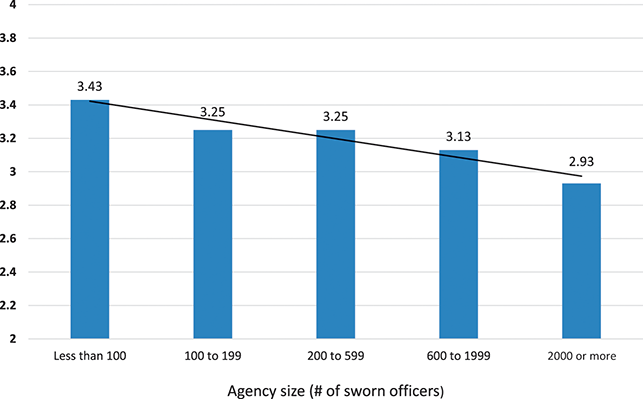

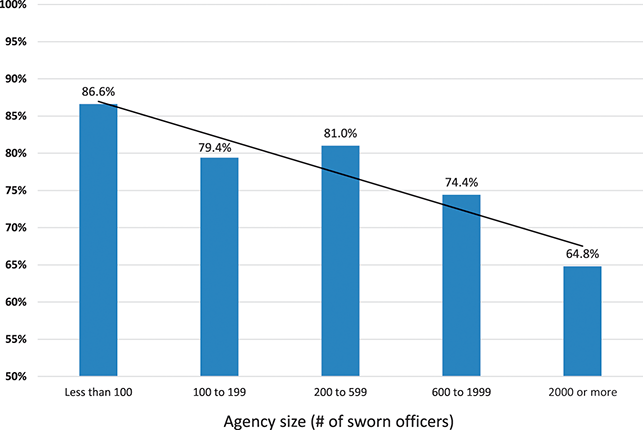

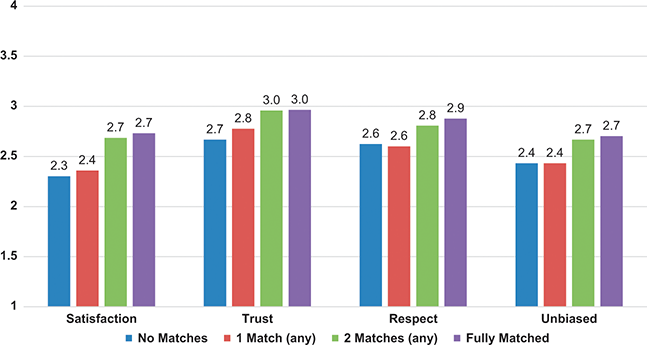

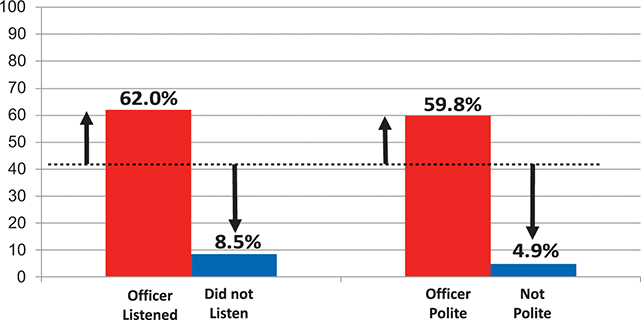

These components can be combined into a single Procedural Justice (PJ) Index, as we did under the National Police Research Platform with fifty-eight agencies. As you can see from Figures 1 and 2, the larger the agency, the lower the procedural justice ratings received by officers and the lower the overall public satisfaction with the encounter. Thus, the problem of procedural injustice is greater in larger, urban areas with larger crime problems and more diversity. Across all agencies, procedural justice reported by white residents on four key measures was roughly 12 percentage points higher than Black residents and 8 percentage points higher than Hispanic residents.

Figure 1 Overall procedural justice index.

Figure 1 Long description

The bars and the data depicted are as follows: 1. Agencies with less than 100 sworn officers: 3.43. 2. Agencies with 100 to 199 sworn officers: 3.25. 3. Agencies with 200 to 599 sworn officers: 3.25. 4. Agencies with 600 to 1999 sworn officers: 3.13 and 5. Agencies with more than 2000 sworn officers: 2.93. The height of each bar reflects the overall procedural justice index score for agencies within that group, where multiple survey questions were combined to produce a procedural justice index. The bars get smaller as the agency size increases, thus indicating that procedural justice within law enforcement agencies, as perceived by officers, decreases as agency size increases. This is also referred to as organizational justice (Rosenbaum and McCarty, 2017).

Figure 2 Overall satisfaction by agency size. (% satisfied and very satisfied).

Figure 2 Long description

The bars and the data depicted are as follows: 1. Agencies with less than 100 sworn officers: 86.6 percent. 2. Agencies with 100 to 199 sworn officers: 79.4 percent. 3. Agencies with 200 to 599 sworn officers: 81.0 percent. 4. Agencies with 600 to 1999 sworn officers: 74.4 percent. 5. Agencies with more than 2000 sworn officers: 64.8 percent. The height of each bar reflects the level of employee job satisfaction for agencies in that group. The bars get smaller as the agency size increases, thus indicating that job satisfaction among officers within these agencies decreases as agency size increases.

Next I will review research in the social sciences that underscores the importance of each of these components, and how interpersonal communication skills are the key to successful procedural justice in practice. The systems proposed here should be able to measure the main components of procedural justice by capturing relevant information from verbal and nonverbal behavior. The importance of this interpersonal communication should be clear – it can lead to the escalation of conflict and use of force or to mutual respect, trust, and cooperation. After reviewing the scientific literature on police programs seeking to improve police legitimacy, Mazerolle and colleagues (Reference Mazerolle, Bennett, Davis, Sargeant and Manning2013a) concluded that frontline procedurally just communication with the public “is important for promoting citizen satisfaction, confidence, compliance and cooperation with the police.”

5.1.1 Respectful Treatment

All human beings have a strong psychological need to be treated with dignity and respect. Regardless of the circumstances, no one wants to be embarrassed, humiliated, demeaned, or dismissed, especially in the presence of others. We know from social psychology that this motivation stems from our desire to maintain a positive social identity and self-esteem (Lind & Tyler, Reference Lind and Tyler1988). Interactions that are not respectful and threaten our self-identity will not be received positively.

Respectful treatment can be understood in the context of interpersonal communication, where each action usually causes a reaction. Communication is often received with positive or negative emotional reactions. Social psychologists have identified the social norms of positive and negative reciprocity (Gouldner, Reference Gouldner1960). According to the positive reciprocity norm, you are expected to respond to a positive action with another positive action. In other words, when someone says or does something nice to you, usually there is a feeling of gratitude, and you feel a need to repay them, which then contributes to equity in relationships, cooperation, and other positive outcomes (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Chen and Portnoy2009). Conversely, if the person responds to you in a negative or hostile way, you are inclined to respond in the same way – which is called negative reciprocity.

I have observed both positive and negative reciprocity in police-public communication, and the latter can easily lead to escalation of tensions. Many officers are trained to believe that their legal authority and power does not require them to play by these social rules. However, the adverse effects of disrespect are clear – research shows that when someone is disrespected by the police, they typically respond in a negative manner, exhibiting disobedience and resistance (Terrill & Reisig, Reference Terrill and Reisig2003).

Similarly, holding stereotypes can often lead to disrespectful treatment by the police. I have already discussed racial bias in enforcement. No one wants to be questioned, searched, and treated as if they are a suspected criminal, which happens too often in high-crime neighborhoods where the vast majority of residents are law-abiding community members. This well-documented reality may help to explain the results of a meta-analysis by Bolger and colleagues (Reference Bolger, Lytle and Bolger2021), which found that satisfaction with the police is lower for people of color, younger people, and those who have been victims of crime.

Interpersonal communication skills are critical for giving and receiving respect. Routinely, police officers interview victims, suspects, and bystanders to gather information, but there are good and bad methods of interviewing and procedural justice is essential. Considerable scientific knowledge regarding effective interviewing techniques can be applied to police work (Stewart & Cash, Reference Stewart and Cash2008).

One study offers some insight regarding effective police communication styles when interacting with suspects. Foster and colleagues (Reference Foster, Zimmerman, Terrill and Somers2024) analyzed 438 BWCs and dashcam video recordings from two police agencies. They found that when patrol officers “presented a positive tenor/demeanor or employed noncoercive verbal tactics,” suspects were significantly more likely to comply with their requests. In contrast, officers’ use of “coercive verbal tactics or accusatory language” did not improve compliance levels. Furthermore, such negative communication may escalate the tension and lead to use of force, but will certainly lower procedural justice evaluations.

When evaluating police-public interactions, I also emphasize the importance of basic conversational etiquette for gaining respect. As you know, etiquette is a set of rules or practices endorsed by society regarding appropriate behavior in interpersonal settings (e.g., Muja, Reference Muja2014; Sia, Reference Sia2023). All social interactions should have a beginning, middle, and end. The conversation should have a beginning where you identify yourself and greet the person, a middle where you listen and wait your turn to talk (“turn taking”), and an ending, where you close the conversation by saying something like “thank you” or “take care.” Differential power dynamics can also cause officers to skip over some of the social etiquette requirements that are normally expected in social exchanges, thus undermining procedural justice.

Importantly, when you realize that something is not going right in a conversation (e.g., the other person has been offended), you engage in “conversation repair” (Albert & De Ruiter, Reference Albert and de Ruiter2018), such as “I’m sorry I interrupted you – go ahead and finish what you were saying about your neighbor” or “I’m sorry I offended you – I didn’t mean to imply that you were at fault.” Conversational repair requires emotional intelligence to recognize that a problem has occurred and know how to fix it.

While interpersonal communication styles can easily influence respect and other aspects of procedural justice, organizational research has found that verbal and nonverbal communication can be easily misunderstood or distorted, and can even contradict each other (Clampitt, Reference Clampitt1991; Vasu et al., Reference Vasu, Stewart and Garson1998). This communication breakdown can have serious consequences for these encounters. Sometimes the words used by the sender can mean something different to the receiver. Body-worn camera data and survey data can help us determine if and when miscommunication occurs.

Also, nonverbal communication can send a message or attitude (Bolton, Reference Bolton1985; Leathers, Reference Leathers1992), such as when arms are folded across the chest, facial frowning or head shaking, eyes rolling, or conversely, smiling, eye contact, positive tone of voice, and head nodding. Whether it is facial expressions or body language or tone of voice, the person is sending a message. Again, all of this remains unmeasured at this point.

Over many years, Paul Ekman and Wallace Friesen created a taxonomy of facial expressions, finding forty-three distinct muscular movements (Gladwell, Reference Gladwell2005). The basic point here is that our face can express our emotions, whether it be anger, fear, sadness, surprise, disgust, happiness, or other emotions. During police-public contacts, if officers become better at quickly identifying and understanding emotional expressions, they can strengthen their communication skills and manage their own emotions. Of course, we need to reliably measure some of these facial expressions and how they are interpreted before police training.

5.1.2 Voice