1 Introduction

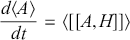

1.1 The Third Revolution

Mechanics is not matter in motion. It is geometric structure in possibility. For more than a century, the principal mode of representation for mechanical theory has been via higher dimensional possibility spaces. Primary amongst these are phase spaces. This Element is about the structure of these spaces and the manner in which this structure affords representations of mechanical systems. Our intention is to set out the core mathematical and physical content of classical and quantum phase space mechanics as a staging post for future foundational investigation. Whilst we confine ourselves to phase space representations in finite dimensions, the content of this Element is relevant to the foundations of essentially all areas of modern physics. Each of classical mechanics, statistical mechanics, quantum theory, and general relativity admits phase space formulations and, as such, foundational questions from each of these areas can be reformulated in phase space terms. Moreover, the phase space representation is perhaps uniquely positioned to provide formal means to explore the connection between physical theories, most significantly the complex of relationships between open and closed, and statistical and quantum theories which is one of the primary motivation for our study.

From a more historical perspective, it is worth remarking that the transition to the study of physical theory in terms of phase spaces can be understood to mark third revolutionary change in physical theory, foundationally as important and almost coincident with the quantum and relativity revolutions, but vastly less studied by historians and philosophers of science. This is the transformation from the quantitive to the qualitative methods in the study of dynamical systems that ran from the late nineteenth century to the mid twentieth century and had as its crowning achievement the celebrated Kolmogorov–Arnold–Moser (KAM) theorem which establishes, under certain conditions, the persistence under small perturbations of quasi-periodic motions in ‘most’ initial states of a Hamiltonian dynamical systems (Arnold, Kozlov, & Neishtadt, Reference Arnold, Kozlov and Neishtadt2006, §6.3).

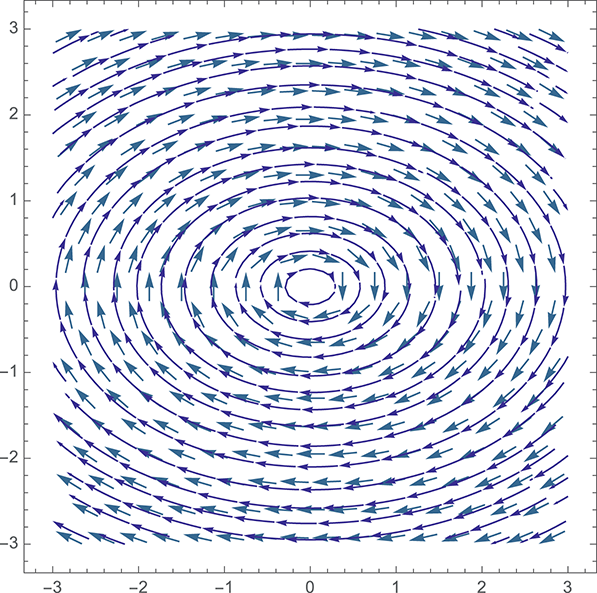

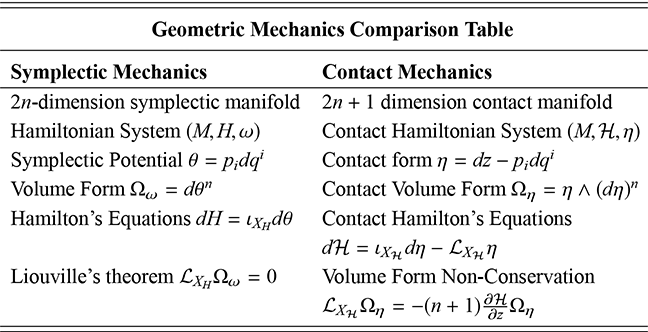

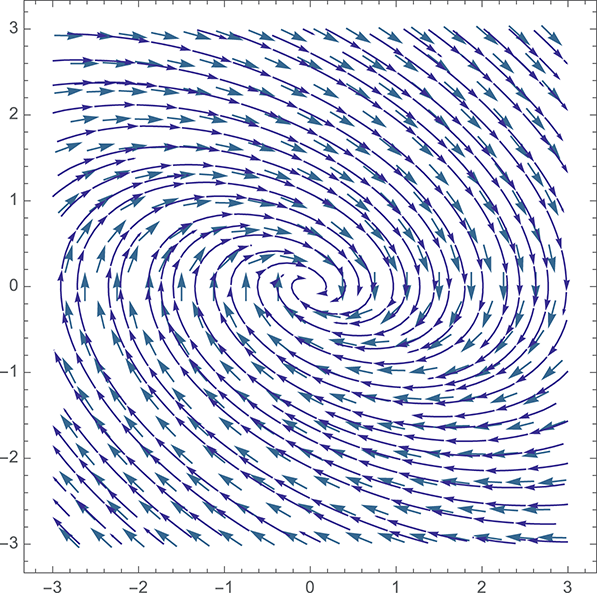

The quantitive to qualitative revolution was initiated by a series of results concerning the stability of the solar system in the last decade of the nineteenth century by Henri Poincaré and brought together in his monumental Les Méthodes Nouvelles de la Mécanique Céleste (New Methods of Celestial Mechanics) published in three volumes between 1892 and 1899. The essence of Poincaré’s qualitative approach was a set of new methods for the study of features of sets of solutions to a mechanical problem in terms of properties of flows on phase spaces. As noted by Abraham and Marsden in the introduction to their textbook, this qualitative approach then immediately suggests a connection between physical properties such as stability, and the geometric structure of phase space:

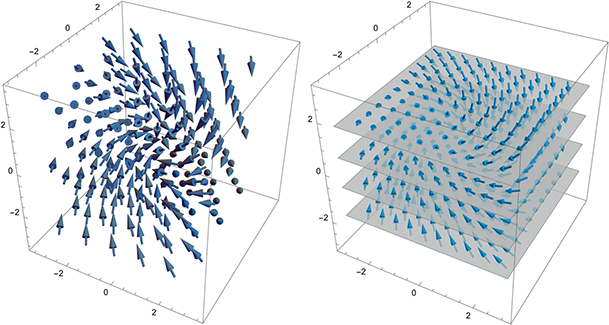

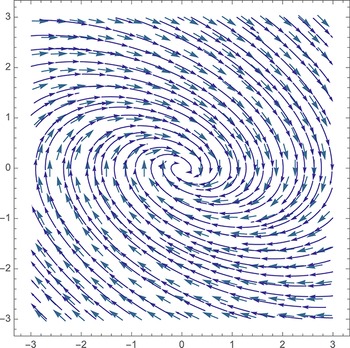

[Poincaré] visualised a dynamical system as a field of vectors on a phase space, in which a solution is a smooth curve tangent at each of its points to the vector at that point. The qualitative theory is based on geometric properties of the phase portrait: the family of solution curves, which fill up the entire phase space. For questions such as stability, it is necessary to study the entire phase portrait including the behaviour for all values of the time parameter. Thus it was essential to consider the entire phase space at once as a geometric object

![]() [The] special geometric structure pertaining to the occurrence of phase variables in canonical conjugate pairs [is] a symplectic structure.

[The] special geometric structure pertaining to the occurrence of phase variables in canonical conjugate pairs [is] a symplectic structure.

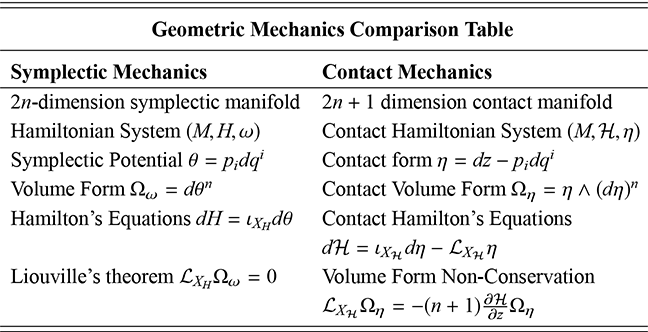

One of the key stepping stones to Poincaré’s stability results was his demonstration of the generic existence of an integral invariant, equivalent to symplectic volume form, under the dynamics (Goroff, Reference Goroff1993, p. I79). This result was earlier proved by both Liouville (1838) and Boltzmann (1871) and is now known as Liouville’s theorem. It is the first and arguably most basic result of qualitative mechanics. Liouville’s theorem and its failure will be one of the three interconnected themes that run throughout this Element.

The other two themes are, first, more generally, the conceptualisation of phase spaces as structured possibility spaces and, second, more specifically, the connection between the notions of ‘open’ and ‘closed’ mechanical systems, dissipation and decoherence, and the idea of probability and quasi-probability flows on phase spaces as incompressible fluid flows. Whilst the first topic has been subject to a limited discussion in the philosophical literature, the second is a novel intervention, and, as such this Element can be understood, in part, as a short research monograph setting out a novel interpretative stance on these topics.

Our main focus is didactic not dialectic. This Element is primarily intended for researchers and graduate students in the philosophy and foundations of physics with an interest in the conceptual foundations of phase space formulations of mechanics. As such, our primary goal is a pedagogical and expository one. An array of formal and conceptual machinery for the analysis of phase space mechanics is introduced and it is hoped that a suitable platform for further studies and research on the topic has been provided.

The formal material presented here is designed to be largely self-contained. The first section focuses upon introducing some key geometric ideas clearly and with a degree of rigour. We will not attempt to offer a comprehensive introduction to differential geometry but rather seek to build up the key conceptual tools assuming some familiarity with manifolds and maps. When we draw on key concepts from topology and analysis we will provide reference to good discussions rather than formal definitions. This will allow the reader a degree of formal foundation from which to understand what it means to formulate the Hamiltonian formulation of classical mechanics in terms of symplectic geometry. Similarly, later we will introduce some basic concepts from measure theory such that the reader can situate the use of probability density functions in stochastic phase space formulations of mechanics in a suitably rigorous mathematical context without requiring an entire course in analysis.

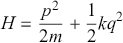

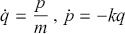

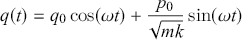

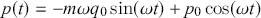

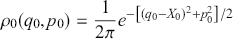

Our goal is to provide the reader with both physical and mathematical intuitions for the structure of classical and quantum phase space representations in finite dimensions. To that end, we will return in each context to the specific example of simple harmonic motion. Each section will include the explicit study of this system and we invite the reader to run through the straightforward calculations themselves. We will largely proceed without step-by-step proofs but with provide reference to relevant results in the literature. Each section concludes with a list of topics for future study with an aim of both establishing connections to existing literature and highlighting issues that are suitable topic for creative graduate work on the topic.

1.2 Modal Structure and Representation

Before we commence our project proper, it will prove useful to provide some ancillary philosophical motivation in terms of the exploration the conceptual foundations of possibility spaces and their role in the representation of modal structure. The concept of modal structure has been much discussed in the context of Ontic Structural Realism (Berenstain & Ladyman, Reference Berenstain and Ladyman2011; Ladyman, Reference Ladyman1998, Reference Ladyman2024; Ladyman & Lorenzetti, Reference Ladyman and Lorenzetti2023; Ladyman & Ross, Reference Ladyman and Ross2007). In that context, it is understood as a general term that subsumes causal structure, mechanisms, nomological structure, probabilistic and statistical structures. Here we will always and only use the term in a much more restrictive sense as relating to the interpretation of mathematical structures on a possibility space. Such a notion requires no consideration of the metaphysics of causation, laws, mechanisms, or dispositions – a metaphysics which has little, if any, relevance to scientific practice in the context of phase space mechanics (and arguably more widely).

The idea of explicitly interpreting phase spaces as possibility spaces can be found in Rickles (Reference Rickles2007). In particular, Rickles suggests that we should understand geometric spaces as being used to represent the ‘possibility structures’ of theories. On this account, the models given by a space and geometric structure function as ‘possibility spaces’ in sense that one starts with a set of possibilities, as represented by the ‘bare’ manifold, and then imposes a geometrical structure on the manifold to give space that represents relationships between these possibilities (Rickles, Reference Rickles2007, p.10).

A further idea that proves useful here is the distinction between material and formal modes as introduced by Ladyman and Ross (Reference Ladyman and Ross2007) following Carnap (Reference Carnap1934), cf. Ladyman & Thebault (Reference Ladyman and Thebault2024). The idea is very simple yet deceptively powerful. Concepts and terms are used in the material mode when applied to concrete systems, and in the formal mode when applied to representations, that is, linguistic or mathematical structures. We thus have that to discuss a physical system

![]() in the material mode is to make an ontological claim about the properties of

in the material mode is to make an ontological claim about the properties of

![]() . To discuss

. To discuss

![]() in the formal mode is to refer to the representations (linguistic or mathematical structures) of

in the formal mode is to refer to the representations (linguistic or mathematical structures) of

![]() . If

. If

![]() is a possible state of the world in material mode, then, in the formal mode, we can think then think of any given phase space point as a representation of such a possibility.

is a possible state of the world in material mode, then, in the formal mode, we can think then think of any given phase space point as a representation of such a possibility.

Next, following Weatherall (Reference Weatherall2018) and Fletcher (Reference Fletcher2020), we can define the representational capacities of a scientific model as the states of affairs that the model may be used to represent well. The representational capacities of a possibility space are then understood to be the structured set of possible states of affairs that the space may be used to represent well. The structures imposed upon this space then correspond to constraints or prescriptions with regard to the space’s representational capabilities. For example, Liouville’s theorem tells us that the possible states of affairs that can be repented by a Hamiltonian phase space must be represented as occupying a stable volume of possibility space over time.

One then arrives at the immediate and highly challenging question: what is the material mode correlate of the constraints or prescriptions with regard to a space’s representational capabilities? In other words, if we consider the part of the model that encodes how the possibilities it can represent relate to each other, can we still think of there being a material mode counterpart to which it corresponds. Let us call this material mode counterpart modal structure.

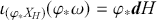

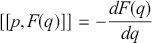

This idea brings to mind the trailblazing discussion of Saunders (Reference Saunders, French and Kamminga1993). Saunders considers what Post (Reference Post1971) had earlier called the generalized principle of correspondence: what is taken over from preceding theories is not only those laws and experimental facts which are well-confirmed, but also ‘patterns’ and ‘internal connections’. He then suggests that a strong candidate for such internal connections are structures such as the Poisson bracket in phase space formalism of classical mechanics which was, of course, ‘deformed’ through theory change into the commutator of quantum theory. Saunders emphasises the historical heuristic fruitfulness of focusing upon structures such as the Poisson bracket, and pivotally their heuristic plasticity.

This idea is further emphasised by French (Reference French2011), who indicates that precisely these structures are the dynamical structures that an Ontic Structural Realists should be realists about cf. Ladyman (Reference Ladyman1998, Reference Ladyman, Zalta and Nodelman2023). We thus have a straightforward response to our question: the aspect of a phase space model that encodes how the possibilities it can represent relate to each other represents ontic modal structure and such structure can ontology promoted to a ‘thing’ along the lines discussed by Berenstain and Ladyman (Reference Berenstain and Ladyman2011) cf. Thébault (Reference Thébault2016). One major attractive feature of such a view of ontic structural realist approach to phase space is that it allows us to make sense of the truth-makers for highly significant modal claims regarding physical systems. One of the features of the world that the truth of modal claims, such as the stability of the solar system, depends upon is the existence of ontic modal structure that is represented by (is the material model correlate of) the satisfaction of Liouville’s theorem. The theorem encodes real structure relating to how possibilities relate to each.

Such a metaphysically thick approach to modal structure may not, however, sit well with all. A healthy, Humean scepticism warns us to be wary of interpreting modal talk metaphysically. It would, however, strain the bonds of philosophical naturalism to seek to diminish the scientific explanatory role of possibility space structure by attempting to either reduce away or eliminate its modal character cf. Lyon and Colyvan (Reference Lyon and Colyvan2008). After all, if the qualitative revolution in mechanics has given us anything it is an ability to make precise modal claims regarding physical systems based upon geometric features of phase spaces.

This sentiment against both realism and eliminativism regarding modal structure brings to mind a general strategy for responding to tricky philosophical ‘placement’ problems: expressivism. Following Price (Reference Price2008), we can understand such problems to occur when we have trouble locating the ‘placement’ of a particular class of things that feature in our vocabulary without our ontology. For example, moral or causal facts. The standard expressivist response to such problems, which Price traces back to Hume, is to argue that the placement issue originates from a category error. Our tendency to seek to ‘place’ moral or causal facts within the world reflects a mistaken understanding of the function of causal or moral vocabulary within our discourse. We note that this language is not in the business of ‘describing reality’ and offer some other positive account of what functional role this vocabulary plays in our linguistic lives.

What prospect is there for offering an expressivist account of the modal structure of possibility spaces that avoids the placement problem? The most detailed discussion of the idea of a modal expressivism can be found in the extended exegeses of the ideas of Wilfred Sellars due to Brandom (Reference Brandom2015) and is encapsulated within what Brandom calls the modal Kant-Sellars thesis (see in particular p. 26 & p.212). The thesis can be expressed in terms of a claim articulated in three stages. First, that there is a relation between the use of modal vocabulary and the use of empirical descriptive vocabulary. Second, that this relation is one of pragmatic dependence in which the use of modal vocabulary can be elaborated from the use of descriptive vocabulary. Third, that this elaboration does no more than make implicit features of the descriptive vocabulary explicit. According to the thesis ‘in being able to use ordinary empirical descriptive vocabulary, one already knows how to do everything that one needs to know how to do, in principle, to use alethic modal vocabulary – in particular subjunctive conditionals’ (p.26). Thus, ‘[m]odal expressivism tells us that modal vocabulary makes explicit normatively significant relations of subjunctively robust material consequence and incompatibility among claimable (hence propositional) contents’ (p.212).

To what extent can we appeal to modal expressivism in the context of the modal structure of possibility spaces? The first and most basic challenge is to recover the basic modal notions that Sellars and Brandom are concerned with. This is most straightforward in the case of the core ‘alethic’ modal vocabulary of natural language: necessity, possibility, impossibility, and contingency. In a possibility space model, what is necessary holds of all points in the state space; what is possible holds of at least one point in the state space; what is impossible holds of no points in the state space; and what is contingent holds of some but not all points in the phase space. Next, and also fairly straightforward, are the relations of concepts of material consequence and incompatibility. For Brandom these are normatively significant relations made explicit by our ordinary language modal vocabulary. In a possibility space representation, these relations can be framed via reference to generic properties that constrain the dynamics to surfaces in possibility space. Most significantly surfaces of constant value in some integral of motion (tantalisingly Brandom even makes reference to Noether’s theorem but draws the connection only to laws rather than possibility space constraints, ibid. p.196).

The modal structure that can be encoded in a possibility space is, however, immeasurably richer than the modal vocabulary of natural language. There is much more than can be said about the structure of possibility in a possibility space representation than in our ordinary modal talk. We might thus understand, geometric and measure theoretic tools to provide us with novel modal concepts that build upon the intuitive idea of structured relations between possibilities. This is precisely the function notions such as volume of possibility space or dynamical stability are designed to play.

Significantly, these expanded modal concepts are such that it is not obvious how one would explicate them from our ordinary empirical descriptive vocabulary of quantities in space and time. We thus find an interesting tension with the third stage of articulation of Brandom’s modal Kant-Sellars thesis. Plausibly, it might not be true that in being able to use ordinary empirical descriptive vocabulary, one already knows how to do everything that one needs to know how to do, in principle, to use modal vocabulary. Rather, one might run the pragmatic dependence the other way round. The novel modal vocabulary that possibility space representations afford us with equip us with new ways of expanding our empirical descriptive vocabulary. One can might thus understand the modal expressivism motivated by the structure of possibility spaces as a more fluid kind than Brandom describes. Modal vocabulary still has a pragmatic dependence on descriptive vocabulary, in this case the descriptions of states of the world encoded in points in possibility spaces, but it can do much more than simply make explicit already acquired functions of that vocabulary. It can equipped us with new expressive tools.

An alternative interpretation, more in keeping with Brandom’s approach, would to frame the novelty of the relevant modal concepts as being with respect to the natural vs. scientific language rather than the empirical descriptive vocabulary per se. The idea would be to seek to preserve the third stage of the modal expressivist account and insist that modal language can only make implicit features of the descriptive vocabulary explicit. In this context, it is descriptive features of scientific language, not contained in ordinary descriptive language, that are made explicit via the modal structure of phase space. Thus, the modal concepts that the structure of phase space equips us with are novel with respect to ordinary descriptive language, and the ordinary modal concepts implicitly contained therein, but are not genuinely novel with respect to scientific descriptive language. Whilst providing such an account of modal structure of phase spaces would fit better with Brandom’s modal Kant-Sellars thesis, it appears to require a rather sophisticated meta-semantic account of how the process of ‘making explicit’ functions in the scientific context. In particular, a meta-semantic account how scientific modal concepts might be explicated from a descriptive vocabulary that lacks, for example, the inherently modal concept of phase space structure. In either case, there is an interesting project of applying the ideas of modal expressivism to scientific language in general and phase space mechanics in particular.

We will return to the articulation of modal expressivist ideas in context of the specific formal features of phase space representations of classical and quantum mechanics in Section 8. We invite the reader to keep idea of modal structure of possibility spaces in mind when navigating the mathematical and physical material that follows.

1.3 Section Summaries

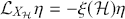

The remainder of this Element consists of seven sections. In Section 2 we provide a skeleton overview of key ideas from differential geometry. Most significantly we will introduce the notion of a two-form as a geometric means of equipping a phase space with an orientated volume and the Lie derivative as a special kind of derivative operator. The Lie derivative allows us to define how a geometric object, such as a function or a two-form, changes along a particular set of directions in a phase space, corresponding to a vector field. The directions picked out by a vector field are directly analogous to flow lines in a fluid and thus a Lie derivative can tell us how a geometric object changes under a flow associated with any vector field.

Section 3 then introduces the formalisation of phase space in terms of symplectic manifolds. These are even-dimensional manifolds equipped with symplectic two-forms. Hamilton’s equations of motion are then defined simply by the special Hamilton vector field associated to the Hamiltonian function by the symplectic two-form. Dynamics is a flow on phase space. The famous result of Liouville (and Poincaré) is then simply that for any Hamiltonian system, the Lie derivative of the symplectic two-form along the flow associated with the Hamiltonian function is zero. The dynamics preserves the volume form. This is a qualitative result that can be stated without reference to any coordinate system. The structure of a Hamiltonian theory in the symplectic representation is encoded in intrinsic geometric facts invariant under the class of transformations called symplectomorphisms.

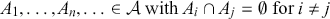

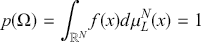

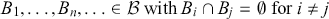

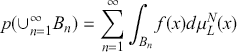

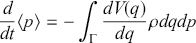

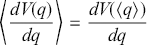

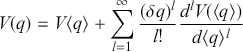

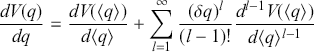

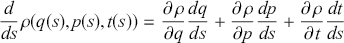

Section 4 introduces a little more mathematical machinery to allow us to discuss measures on phase space via the integration of probability density functions. We then show how these objects can be combined with the symplectic version of Hamiltonian mechanics in order to define a set of stochastic phase space models that provide a perspicacious formulation of classical statistical mechanical theory. In this context, Liouville’s theorem has a natural presentation in terms of the incompressibility of a probability ‘fluid’ – which admits no local sources or sinks – and is formally equivalent to statement that the total derivative of the probability density is always vanishing in a stochastic Hamiltonian system. A further important result that can be derived in this formalism under restricted circumstances is a classical stochastic version of the Ehrenfest equations in which the first moments of position and momentum obey Newton’s first two laws of motion. This provides a simple and direct means to connect stochastic and deterministic models and, moreover, a precise language to understand divergence from the Ehrenfest equations in stochastic models that is also found in quantum theories.

Section 5 considers the geometric formalism for the study of open classical systems that display dissipative behaviour. Our analysis will bring in the tools of contact geometry which are a natural extension of symplectic geometry and allow us to formulate mechanics in odd dimensional phase spaces. Such phase spaces are uniquely suited to the representation of dissipative systems since they provide possibility space models of systems that are mechanically non-conservative, such as an oscillator with a velocity-dependent damping factor. Moreover, contact geometry provides us with a set of geometric models which provide phase representations with structure beyond that encoded in Liouville’s theorem. We are able to represent phase space dynamics with compression (or expansion) of the volume form under the contact Hamiltonian flow. This is to represent structured sets of possibilities which occupy a shrinking (or expanding) volume of possibility space over time.

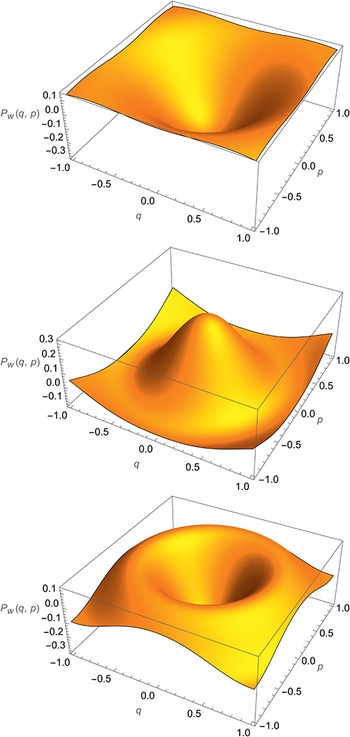

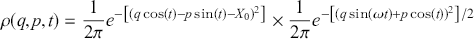

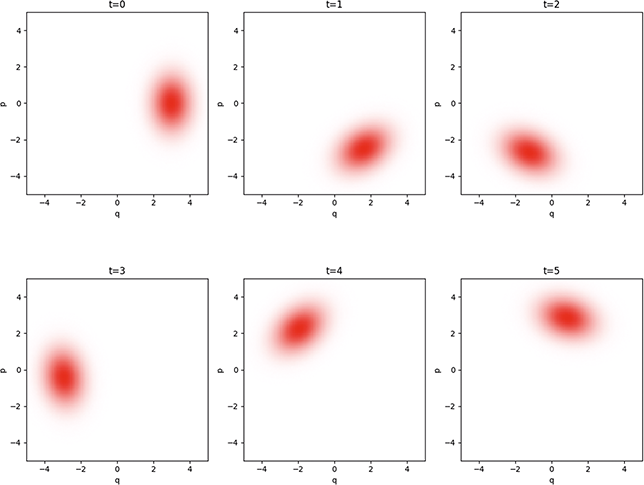

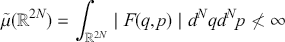

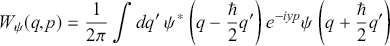

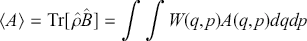

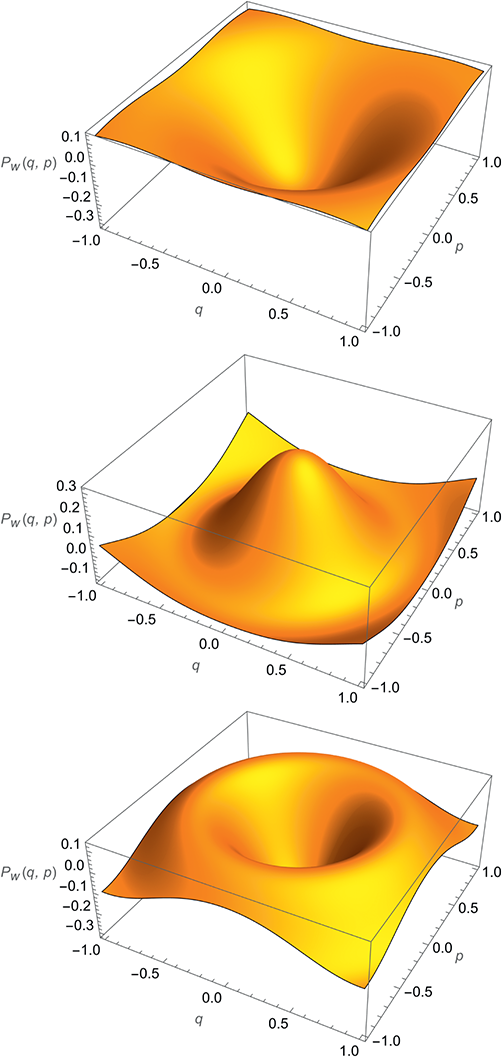

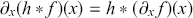

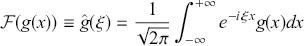

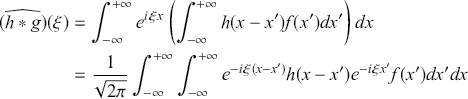

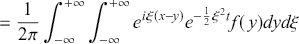

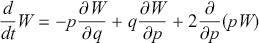

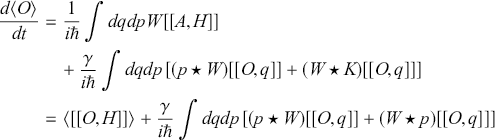

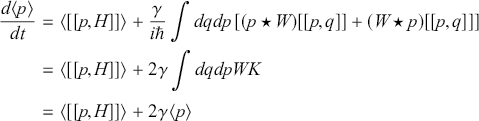

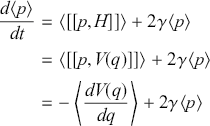

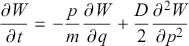

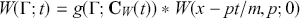

Section 6 introduces the phase space formulation of quantum mechanics focusing on the Wigner function. We first consider some formal ideas relating to the generalisation from a probability density function to a quasi-probability density function and some subtle features of the finite signed measure that is induced by such functions. We next build up the quantum phase formalism step by step noting the crucial differences with the stochastic phase space theory in terms of the negativity and non-localisability of the Wigner quasi-probability density function. We then return to our theme of Liouville’s theorem and its failure by showing how the local compressibility of the quasi-probability density is directly connected to the structure of the Moyal bracket that equips the quantum phase space observables, the Weyl symbols, with a non-commutative structure. Finally, we demonstrate the sense in which the Ehrenfest-type relations for the first moments in the quantum phase space formalism correspond to those derived in the context of the stochastic theory.

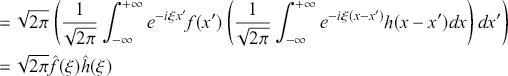

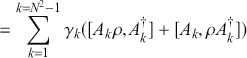

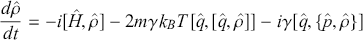

Section 7 considers the quantum phase space representation of open quantum systems. Such systems are generically represented as having non-unitary dynamics and provide the basis for the study of the phenomena of decoherence. We start with a final piece of mathematics based upon Fourier transforms that leads to the formal idea of a Gaussian smoothing. We then consider the general formal structure of an open quantum systems and the relationship between non-unitarity and probability conservation. The successive discussions then introduce the three most important classes of open quantum system master equations the Lindblad equation, the Caldeira-Leggett equation, and the Joos-Zeh equation. The latter two equations are considered in their quantum phase space form. This analysis allows us to demonstrate the formal connections to classical damping via Ehrenfest relations in the case of the Caldeira-Leggett equation and to decoherence and Wigner positivity via Gaussian smoothing in the case of the Joos-Zeh master equation.

The final Section 8 then returns to our theme of representation and possibility and provides an interpretative summary of our results and their implications for the ideas of representational capacity and modal structure.

2 Elements of Differential Geometry

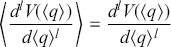

Our main goal in this section is to introduce the idea of differential forms together with the four basic operations on differential forms that define the theory of exterior calculus. These are the wedge product,

![]() , interior product,

, interior product,

![]() , exterior derivative, d, and Lie derivative,

, exterior derivative, d, and Lie derivative,

![]() . We will follow Olver (Reference Olver2000), Arnol’d (Reference Arnol’d2013), and Holm (Reference Holm2011), supplemented by Abraham and Marsden (Reference Abraham and Marsden1980). Additional sources are noted where relevant. We will assume basic concepts from differential geometry such the definition of a differential manifold. The Einstein summation convention is used throughout.

. We will follow Olver (Reference Olver2000), Arnol’d (Reference Arnol’d2013), and Holm (Reference Holm2011), supplemented by Abraham and Marsden (Reference Abraham and Marsden1980). Additional sources are noted where relevant. We will assume basic concepts from differential geometry such the definition of a differential manifold. The Einstein summation convention is used throughout.

We start by recapping the idea a of vector field and flow on a manifold. When combined with the language of differential forms this will allow us to provide a fully geometric rendering of phase space mechanics. A vector field,

![]() , on a manifold,

, on a manifold,

![]() , assigns a tangent vector

, assigns a tangent vector

![]() to each point

to each point

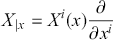

![]() . In local coordinates a vector field has the form:

. In local coordinates a vector field has the form:

(2.1)

(2.1)

where each

![]() is a smooth function of

is a smooth function of

![]() . In what follows we will often write a vector fields simply as

. In what follows we will often write a vector fields simply as

![]() for short. We will write the space of vector fields on a manifold

for short. We will write the space of vector fields on a manifold

![]() . Formally, the space of vector fields on a manifold can also be defined in terms of smooth sections of the tangent bundle

. Formally, the space of vector fields on a manifold can also be defined in terms of smooth sections of the tangent bundle

![]() (Abraham & Marsden, Reference Abraham and Marsden1980).

(Abraham & Marsden, Reference Abraham and Marsden1980).

An integral curve of a vector field is a smooth parametrised curve

![]() whose tangent vector

whose tangent vector

![]() at any point,

at any point,

![]() , coincides with the value of

, coincides with the value of

![]() , so we have:

, so we have:

(2.2)

(2.2)

If we visualise a vector field as an array of arrows on a manifold, then the integral curves are the curves that ‘thread’ the arrows such that at any point the curve is tangent to the arrow at that point. The parametrised maximal integral curve passing thought

![]() is the flow generated by

is the flow generated by

![]() which we will write as

which we will write as

![]() . The flow generated by a vector field is equivalent to the local group action of the Lie group

. The flow generated by a vector field is equivalent to the local group action of the Lie group

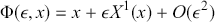

![]() on that manifold. The vector field is then the infinitesimal generator of the group action since the Taylor expansion takes the form:

on that manifold. The vector field is then the infinitesimal generator of the group action since the Taylor expansion takes the form:

(2.3)

(2.3)

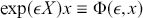

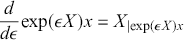

We can express the flow in terms of the exponentiation of the vector field as:

(2.4)

(2.4)

The property that

![]() is tangent to

is tangent to

![]() for fixed

for fixed

![]() ,

,

(2.5)

(2.5)

can thus be written as:

(2.6)

(2.6)

This way of thinking about the flows in terms of exponentiation will prove crucial for the definition of the fourth operation on differential forms, the Lie derivative. Before we get to that point, let us first introduce the idea of forms itself.

We will focus on giving simple and intuitive definitions. A more formal and concise approach is taken in the following box. In the most general sense, differential forms are a special type of tensors on manifolds. They have the property that they are anti-symmetric under exchange of any pair of indices. Differential forms are the crucial formal object that allow for the standard integral theorems, such as those due to Gauss and Stokes, to be generalised to manifolds of arbitrary dimensions. They are also the central object that allow for the geometrisation of Hamiltonian mechanics. Like tensors in general, differential forms have a rank. Intuitively, we can think of this rank as the number of independent dimensions that can be simultaneously associated with a magnitude by the tensor. For our purposes it will be important to understand the formal definition of differential forms of rank 0, 1 and 2. These intuitively correspond a specific type of generalisations of functions, vectors, and matrices respectively.

A rank-

![]() differential form, or

differential form, or

![]() -form, on a manifold

-form, on a manifold

![]() is just a smooth real valued function

is just a smooth real valued function

![]() . The differential of the function

. The differential of the function

![]() at a point

at a point

![]() is a linear map,

is a linear map,

![]() , from the tangent space

, from the tangent space

![]() of

of

![]() at

at

![]() to the real numbers. If we write a local coordinate basis of the tangent space as

to the real numbers. If we write a local coordinate basis of the tangent space as

![]() ,

,

![]() , then a dual basis can be written as a local coordinate basis as

, then a dual basis can be written as a local coordinate basis as

![]() . The differential of a function is then written as:

. The differential of a function is then written as:

(2.7)

(2.7)

A differential

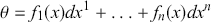

![]() -form then has a local coordinate expression in terms of linear combinations of differentials of the coordinates:

-form then has a local coordinate expression in terms of linear combinations of differentials of the coordinates:

(2.8)

(2.8)

As such, the space of

![]() -forms at a point

-forms at a point

![]() is just the space of linear functions on the tangent space

is just the space of linear functions on the tangent space

![]() , This is, by definition, the cotangent space

, This is, by definition, the cotangent space

![]() , or dual vector space to the tangent space at

, or dual vector space to the tangent space at

![]() . A

. A

![]() -form on a manifold

-form on a manifold

![]() is then a smooth section of the cotangent bundle

is then a smooth section of the cotangent bundle

![]() . Geometrically we can understand a

. Geometrically we can understand a

![]() -form as defining an orientated line segment.

-form as defining an orientated line segment.

In order to define the next rank of differential form, the

![]() -form, it is convenient to introduce the first of our four operations of exterior calculus. This is the wedge product,

-form, it is convenient to introduce the first of our four operations of exterior calculus. This is the wedge product,

![]() . Its most basic operation is the multiplication of two

. Its most basic operation is the multiplication of two

![]() -forms in order to construct a

-forms in order to construct a

![]() -form, that is, it is such that

-form, that is, it is such that

![]() is a

is a

![]() -form. In a local

-form. In a local

![]() -form basis

-form basis

![]() ,

,

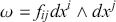

![]() we have that:

we have that:

(2.9)

(2.9)

where the sum over repeated indices is ordered so that it is taken for all

![]() satisfying

satisfying

![]() . The local coordinate expression for a

. The local coordinate expression for a

![]() -form on

-form on

![]() is thus:

is thus:

(2.10)

(2.10)

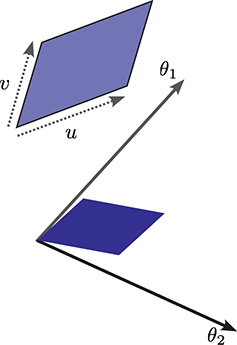

Geometrically we can understand the wedge product as allowing us to compose orientated line segments (

![]() -forms) to construct orientated surface elements (

-forms) to construct orientated surface elements (

![]() -forms), then orientated volume elements (

-forms), then orientated volume elements (

![]() -forms), and so on for arbitrary dimensions (rank of form). That these elements are orientated is equivalent to the fact that the wedge product is anti-symmetric under exchange of indices and so we have that

-forms), and so on for arbitrary dimensions (rank of form). That these elements are orientated is equivalent to the fact that the wedge product is anti-symmetric under exchange of indices and so we have that

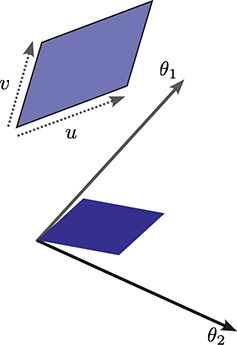

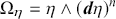

![]() . See Figure 1 for illustration.

. See Figure 1 for illustration.

Figure 1 Geometric illustration of

![]() -form as an orientated area element:

-form as an orientated area element:

![]() .

.

Formally, the anti-symmetry is implied by the fact that the wedge product is the multiplication operation of alternating algebra, which by definition, means that we have that

![]() which implies

which implies

![]() . The interpretation

. The interpretation

![]() -form as an orientated surface between two

-form as an orientated surface between two

![]() -forms obviously matches with the property that the orientated area of a

-forms obviously matches with the property that the orientated area of a

![]() -form with itself is zero. If we consider a two form

-form with itself is zero. If we consider a two form

![]() acting on a pair of vectors

acting on a pair of vectors

![]() and

and

![]() then the alternating property is that

then the alternating property is that

![]() and

and

![]() which is the property of skew-symmetry. See the following box for more details.

which is the property of skew-symmetry. See the following box for more details.

Let

![]() by a smooth manifold and

by a smooth manifold and

![]() its tangent space at

its tangent space at

![]() . The space

. The space

![]() of differential

of differential

![]() -forms at

-forms at

![]() is the set of all

is the set of all

![]() -linear alternating functions:

-linear alternating functions:

(2.11)

(2.11)

A smooth differential

![]() -form

-form

![]() on

on

![]() is then the collection of smoothly varying alternating

is then the collection of smoothly varying alternating

![]() -linear maps

-linear maps

![]() where we require that the evaluation of the

where we require that the evaluation of the

![]() -form on

-form on

![]() smooth vector fields is a smooth real function of

smooth vector fields is a smooth real function of

![]() . (Olver, Reference Olver2000, p. 54)

. (Olver, Reference Olver2000, p. 54)

Differential

![]() -forms on a manifold

-forms on a manifold

![]() form an exterior algebra. The wedge product is as an associative, bilinear, anticomputative map that is the product operation on the exterior algebra of differential forms. The wedge product is defined such that if

form an exterior algebra. The wedge product is as an associative, bilinear, anticomputative map that is the product operation on the exterior algebra of differential forms. The wedge product is defined such that if

![]() and

and

![]() for

for

![]() then

then

![]() where the explicit form of the

where the explicit form of the

![]() operation can be defined in terms of the tensor product operation as

operation can be defined in terms of the tensor product operation as

(2.12)

(2.12)

where A is the alternating map. (Abraham & Marsden, Reference Abraham and Marsden1980, §2.3-4).

The second operation on differential forms is the interior product,

![]() . The interior product is also called the contraction and allows us to compose a differential form with a vector field such that we lower the rank of the form in question. For our purposes the most important application of the interior product is the contraction of a

. The interior product is also called the contraction and allows us to compose a differential form with a vector field such that we lower the rank of the form in question. For our purposes the most important application of the interior product is the contraction of a

![]() -form with a vector field to give a

-form with a vector field to give a

![]() -form. In components, the explicit form of the product can be written:

-form. In components, the explicit form of the product can be written:

(2.13)

(2.13)

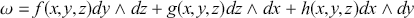

In two dimensions, the contraction of a vector field,

![]() , with a

, with a

![]() -form,

-form,

![]() then takes the simple form:

then takes the simple form:

(2.14)

(2.14)

We have thus combined a

![]() -form with a vector field in order to product a

-form with a vector field in order to product a

![]() -form. The contraction of a

-form. The contraction of a

![]() -form always yields a

-form always yields a

![]() -form (or zero). Later we will find that Hamilton’s equations can be expressed in terms of the contraction of a canonical

-form (or zero). Later we will find that Hamilton’s equations can be expressed in terms of the contraction of a canonical

![]() -form on phase space.

-form on phase space.

The contraction of a

![]() -form is then defined by the interior product of a

-form is then defined by the interior product of a

![]() -form with a vector field, which gives us a

-form with a vector field, which gives us a

![]() -form. As already noted, a

-form. As already noted, a

![]() -form is just a function. The contraction of a

-form is just a function. The contraction of a

![]() -form is always zero, so

-form is always zero, so

![]() . The interior product of a vector field with a

. The interior product of a vector field with a

![]() -form is equivalent to the dot product between a covariant and contravariant vectors:

-form is equivalent to the dot product between a covariant and contravariant vectors:

(2.15)

(2.15)

where the indices

![]() indicate vector components and we assume the Einstein summation convention.

indicate vector components and we assume the Einstein summation convention.

The third operation on differential forms is the is the exterior derivative, d. The exterior derivative is the unique family of mappings that raise the rank of a differential form. In this sense it can be thought of the opposite or dual operation to the interior derivative. The exterior product is a linear, local operator and is such that

![]() . The exterior derivative of a

. The exterior derivative of a

![]() -form is a

-form is a

![]() -form and the exterior derivative of a

-form and the exterior derivative of a

![]() -form is a

-form is a

![]() -form, and so on. We have already given the formula for the exterior derivative of a

-form, and so on. We have already given the formula for the exterior derivative of a

![]() -form in terms of the expression for the differential of a function Equation (2.7). The exterior derivative of a

-form in terms of the expression for the differential of a function Equation (2.7). The exterior derivative of a

![]() -form is given in coordinates by the expression:

-form is given in coordinates by the expression:

(2.16)

(2.16)

The class of

![]() -forms, which are such that they can be written as the exterior derivative of a one form,

-forms, which are such that they can be written as the exterior derivative of a one form,

![]() , are called exact. A two form that is such that

, are called exact. A two form that is such that

![]() is called closed. Since

is called closed. Since

![]() we have that all exact

we have that all exact

![]() -forms are necessarily closed.

-forms are necessarily closed.

The exterior product allows us to express the following attractive generalisation of Stokes theorem due to Élie Cartan:

Theorem 2.1 Stokes-Cartan Theorem: Suppose

![]() is a compact oriented

is a compact oriented

![]() -dimensional manifold with boundary

-dimensional manifold with boundary

![]() and

and

![]() is a smooth

is a smooth

![]() -form on

-form on

![]() . Then:

. Then:

(2.17)

(2.17)

As well as generalised Stokes’s original theorem in vector calculus, the Stokes-Cartan Theorem also embodies the fundamental theorem of calculus and the Gauss divergence theorem. We can see the first relation rather trivially by considering the integration of the differential of a function,

![]() , along a curve in

, along a curve in

![]() with endpoints

with endpoints

![]() and

and

![]() . That is, applying Theorem 2.1 in the case of a

. That is, applying Theorem 2.1 in the case of a

![]() -form integrated over a

-form integrated over a

![]() -dimensional manifold with

-dimensional manifold with

![]() -dimensional boundaries

-dimensional boundaries

![]() :

:

(2.18)

(2.18)

Let

![]() be a manifold. Then there is a unique family of mappings

be a manifold. Then there is a unique family of mappings

![]() , and

, and

![]() is open in

is open in

![]() , such that the exterior derivative, denoted

, such that the exterior derivative, denoted

![]() , has the properties of being a closed, local, anti-derivation of the exterior algebra that reduces to the differential for

, has the properties of being a closed, local, anti-derivation of the exterior algebra that reduces to the differential for

![]() . The property of being an anti-derivation in this context means that:

. The property of being an anti-derivation in this context means that:

(2.19)

(2.19)

for

![]() and

and

![]() (Abraham & Marsden, Reference Abraham and Marsden1980, Theorem 2.4.5). Let

(Abraham & Marsden, Reference Abraham and Marsden1980, Theorem 2.4.5). Let

![]() be a manifold,

be a manifold,

![]() a tangent vector field, and

a tangent vector field, and

![]() a

a

![]() -form. Then the interior derivative

-form. Then the interior derivative

![]() is defined by:

is defined by:

(2.20)

(2.20)

where

![]() for

for

![]() . The interior product is an anti-derivation of the exterior algebra and can be proved to be such that it maps

. The interior product is an anti-derivation of the exterior algebra and can be proved to be such that it maps

![]() -forms to

-forms to

![]() -forms. That is, we have that

-forms. That is, we have that

![]() . (Abraham & Marsden, Reference Abraham and Marsden1980, Theorem 2.4.13).

. (Abraham & Marsden, Reference Abraham and Marsden1980, Theorem 2.4.13).

The fourth and final operation on differential forms is the Lie derivative,

![]() . The Lie derivative of a differential form with respect to a vector field,

. The Lie derivative of a differential form with respect to a vector field,

![]() , is a linear, derivation operation on the space of differential forms that commutes with the exterior derivative and is such that it maps

, is a linear, derivation operation on the space of differential forms that commutes with the exterior derivative and is such that it maps

![]() -forms to

-forms to

![]() -forms. The Lie derivative allows us to analyse how a geometric object on a manifold varies under the flow induced by a vector field on that manifold. In particular, the Lie derivative provides us with a means of comparing vector fields and differential before and after they are acted upon by the flow of a vector field.

-forms. The Lie derivative allows us to analyse how a geometric object on a manifold varies under the flow induced by a vector field on that manifold. In particular, the Lie derivative provides us with a means of comparing vector fields and differential before and after they are acted upon by the flow of a vector field.

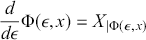

Most straightforwardly, we can understand the Lie derivative of a function,

![]() , with respect to the flow induced by a vector field,

, with respect to the flow induced by a vector field,

![]() , as telling us how

, as telling us how

![]() changes under the infinitesimal flow generated by

changes under the infinitesimal flow generated by

![]() . In the exponential representation of a flow what we are doing in calculating the Lie derivative is then equivalent to evaluating

. In the exponential representation of a flow what we are doing in calculating the Lie derivative is then equivalent to evaluating

![]() as

as

![]() varies. We thus have that:

varies. We thus have that:

(2.21)

(2.21)

(2.22)

(2.22)

so for

![]() we have that:

we have that:

(2.23)

(2.23)

The Lie derivative of a function therefore reduces to the ordinary directional derivative in the direction picked out by the vector field. (Abraham & Marsden, Reference Olver2000, p.85).

The Lie derivative of a vector field with respect to another vector field is called the Lie bracket of two vector fields. It is the unique vector field

![]() satisfying:

satisfying:

(2.24)

(2.24)

for

![]() and

and

![]() . We can conceive the Lie bracket of two vector fields geometrically as the infinitesimal commuter of one-parameter groups associated with the two vector fields,

. We can conceive the Lie bracket of two vector fields geometrically as the infinitesimal commuter of one-parameter groups associated with the two vector fields,

![]() and

and

![]() .

.

The Lie bracket defines an algebraic structure called a Lie algebra. In particular, if we consider the space of vector fields on a manifold

![]() then the Lie bracket

then the Lie bracket

![]() on

on

![]() together with the real vector space structure of

together with the real vector space structure of

![]() induces a Lie algebra since satisfies the three conditions:

induces a Lie algebra since satisfies the three conditions:

1. Bilinear:

for all real scalars

for all real scalars

2. Alternativity:

3. Jacobi Identity:

These conditions imply that the Lie bracket is skew symmetric, so

![]() and it is possible to define a Lie algebra via bilinearity, skew symmetry and the Jacobi identity. See (Abraham & Marsden, Reference Abraham and Marsden1980, p.85) and (Holm, Reference Holm2011, §1.7) for more details.

and it is possible to define a Lie algebra via bilinearity, skew symmetry and the Jacobi identity. See (Abraham & Marsden, Reference Abraham and Marsden1980, p.85) and (Holm, Reference Holm2011, §1.7) for more details.

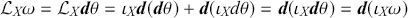

The Lie derivative of

![]() -forms can be calculated straightforwardly based upon the fact that the

-forms can be calculated straightforwardly based upon the fact that the

![]() and d operations commute. This means that we have that:

and d operations commute. This means that we have that:

(2.25)

(2.25)

a short calculation shows that the final expression on the right is equivalent to:

(2.26)

(2.26)

The final expression is a special case of Cartan’s magic formula which gives us a general equivalence between Lie derivatives and the combination of interior and exterior derivatives:

(2.27)

(2.27)

A second important special case of Cartan’s magic formula is for closed

![]() -forms

-forms

![]() :

:

(2.28)

(2.28)

since

![]() . Thus the Lie derivative of a closed

. Thus the Lie derivative of a closed

![]() -form with respect to a vector field

-form with respect to a vector field

![]() , is equivalent to the exterior derivative of the contraction of that vector field with that

, is equivalent to the exterior derivative of the contraction of that vector field with that

![]() -form.

-form.

The Lie derivative is uniquely suited to expression of the invariance properties of a differential forms since we have that a differential

![]() -form

-form

![]() on a manifold

on a manifold

![]() is invariant under the flow of a vector field

is invariant under the flow of a vector field

![]() if and only if

if and only if

![]() . (Olver, Reference Olver2000, Proposition 1.65). A similar result holds for vector fields. Intuitively the idea is that since the Lie derivative gives us an expression for the behaviour of a geometric object (form, vector field, or more general tensor field) as it is dragged along the flow generated by a vector field. The vanishing of the Lie derivative is necessary and sufficient for invariance under the relevant flow.

. (Olver, Reference Olver2000, Proposition 1.65). A similar result holds for vector fields. Intuitively the idea is that since the Lie derivative gives us an expression for the behaviour of a geometric object (form, vector field, or more general tensor field) as it is dragged along the flow generated by a vector field. The vanishing of the Lie derivative is necessary and sufficient for invariance under the relevant flow.

It will be useful to be able to talk precisely about how maps on manifolds transfer onto the differential objects defined on them.Footnote 1 A diffeomophisms is an invertible

![]() -mappings between the manifolds:

-mappings between the manifolds:

![]() . The transfer of a diffeomorphism onto vector fields of the same rank defined on

. The transfer of a diffeomorphism onto vector fields of the same rank defined on

![]() and

and

![]() is then the push-forward of the diffeomorphism which we write

is then the push-forward of the diffeomorphism which we write

![]() . The transfer of a diffeomorphism onto a differential form of the same rank defined on

. The transfer of a diffeomorphism onto a differential form of the same rank defined on

![]() and

and

![]() is then the pull-back of the diffeomorphism which we write

is then the pull-back of the diffeomorphism which we write

![]() .

.

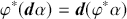

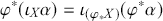

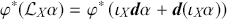

We can then specify the transfer of a diffeomorphism onto the exterior derivative as

(2.29)

(2.29)

and onto the interior derivative as:

(2.30)

(2.30)

The first expression simply amounts to saying that the exterior derivative operation commutes with the pull-back of a diffeomorphism. The second, implies that we can construct the pull-back of a diffeomorphism onto the interior derivative by applying the push-forward operation to the vector field and the pull-back operation to the differential form.

If we combine these expressions with Cartan’s magic formulae then we can write the pull-back of the Lie derivative of a differential form with respect to a vector field simply as:

(2.31)

(2.31)

(2.32)

(2.32)

These relations will prove of particular value later.

Define the pull-back of the flow of a vector field X as:

(2.33)

(2.33)

Let

![]() be a vector field on

be a vector field on

![]() and

and

![]() be a differential

be a differential

![]() -form defined on

-form defined on

![]() . The Lie derivative of

. The Lie derivative of

![]() with respect to

with respect to

![]() is the

is the

![]() -form whose value at

-form whose value at

![]() is given by:

is given by:

(2.34)

(2.34)

(Olver, Reference Olver2000, Definition 1.63).

This concludes our brief review of differential forms and the four basic operations of wedge product, interior product, exterior derivative, and lie derivative. In the next section we will see how the language of differential forms allows for a natural geometric rendering of Hamiltonian mechanics defined by a special type of

![]() -form called the symplectic

-form called the symplectic

![]() -form.

-form.

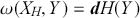

3 Symplectic Geometry and Phase Space Mechanics

![]() la physique est de la géométrie — géométrie symplectique.

la physique est de la géométrie — géométrie symplectique.

3.1 Symplectic Geometry and Hamiltonian Systems

In this section we will analyse the geometric structure of Hamiltonian mechanics understood as symplectic structure. In particular, we will show how Hamilton’s equations can be written in the language of differential forms with the operations on differential forms defined in the previous section applied to the symplectic

![]() -form that is intrinsic to the geometric structure of phase spaces.

-form that is intrinsic to the geometric structure of phase spaces.

The world ‘symplectic’ was coined by Herman Weyl and means interwoven or plaited. As we shall see, the term is an apposite one since it is precisely the symplectic structure that encodes the interweaving of the canonical position and momentum coordinates with both each other and the dynamics. Here we will primarily follow Abraham and Marsden (Reference Abraham and Marsden1980).

We start by introducing the idea of a non-degenerate differential

![]() -form. Consider a

-form. Consider a

![]() -form acting on a pair of vector fields

-form acting on a pair of vector fields

![]() . We say that

. We say that

![]() is non-degenerate when we have that

is non-degenerate when we have that

![]() implies that

implies that

![]() . Conversely, a degenerate

. Conversely, a degenerate

![]() -form is such that there is a

-form is such that there is a

![]() such that

such that

![]() . This is equivalent to a non-degenerate

. This is equivalent to a non-degenerate

![]() -form having a trivial kernel, or nullspace, and a degenerate

-form having a trivial kernel, or nullspace, and a degenerate

![]() -form having a non-trivial kernel. These definitions generalise to

-form having a non-trivial kernel. These definitions generalise to

![]() -forms. However, the

-forms. However, the

![]() -form case is all we will need for the definition of symplectic structure.

-form case is all we will need for the definition of symplectic structure.

It can be proven that a

![]() -form on a manifold

-form on a manifold

![]() is non-degenerate if and only if

is non-degenerate if and only if

![]() has an even dimension,

has an even dimension,

![]() , and

, and

![]() is a volume form on

is a volume form on

![]() that we write as:

that we write as:

(3.1)

(3.1)

A manifold admits a nowhere-vanishing volume form if and only if it is orientable and thus we have that the existence of a non-degenerate two form on a manifold is necessary and sufficient for the manifold to be orientable. See (Abraham & Marsden, Reference Abraham and Marsden1980, §3.1) for more details.

We are now able to state the pivotal theorem of Darboux which, in this context, means that given a closed, non-degenerate

![]() -form on a manifold, there is a local coordinate system at every point in which the form has a canonical coordinate expression. The theorem can be stated as follows:

-form on a manifold, there is a local coordinate system at every point in which the form has a canonical coordinate expression. The theorem can be stated as follows:

Theorem 3.1 Darboux’s theorem: Suppose

![]() is a non-degenerate

is a non-degenerate

![]() -form on a

-form on a

![]() -dimensional

-dimensional

![]() . Then

. Then

![]() if and only if there is a chart

if and only if there is a chart

![]() at each

at each

![]() such that

such that

![]() and with

and with

![]() we have that:

we have that:

(3.2)

(3.2)

(Abraham & Marsden, Reference Abraham and Marsden1980, Theorem 3.2.2)

Let us then define a symplectic form as a closed, non-degenerate

![]() -form,

-form,

![]() , on a manifold,

, on a manifold,

![]() . A symplectic manifold,

. A symplectic manifold,

![]() , is then given by a pairing of a manifold,

, is then given by a pairing of a manifold,

![]() , together with a symplectic form on

, together with a symplectic form on

![]() . Application of Darboux’s theorem to symplectic manifolds establishes the existence of a special set of symplectic charts where the component functions

. Application of Darboux’s theorem to symplectic manifolds establishes the existence of a special set of symplectic charts where the component functions

![]() are canonical coordinates, which we will write as

are canonical coordinates, which we will write as

![]() to foreshadow the application to Hamiltonian systems. We are thus guaranteed to be able to locally express the symplectic form as:

to foreshadow the application to Hamiltonian systems. We are thus guaranteed to be able to locally express the symplectic form as:

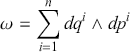

(3.3)

(3.3)

and volume form as:

(3.4)

(3.4)

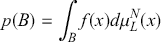

By the Riesz representation theorem (Abraham & Marsden, Reference Abraham and Marsden1980, Theorem 2.6.9). we are guaranteed that for any orientable manifold,

![]() , with volume form

, with volume form

![]() , there is a unique measure

, there is a unique measure

![]() such that for every continuous function of compact support we have that:

such that for every continuous function of compact support we have that:

(3.5)

(3.5)

See (Souriau, Reference Souriau2012, §16) for a detailed introduction to the definitions of measures on manifolds. N.B. strictly the measure

![]() should be defined on the Borel sets

should be defined on the Borel sets

![]() of

of

![]() . We will provide an explicit definition of the Borel sets of

. We will provide an explicit definition of the Borel sets of

![]() in the context of probability measures in Section 4.1.

in the context of probability measures in Section 4.1.

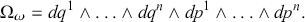

For a symplectic manifold the unique measure associated to the volume form,

![]() , is the Liouville measure

, is the Liouville measure

![]() . In coordinates, the Liouville measure can be expressed as:

. In coordinates, the Liouville measure can be expressed as:

(3.6)

(3.6)

For most physical purposes we are interested in symplectic manifolds that are phase spaces. That is, symplectic manifolds that are the cotangent bundles,

![]() , to a configuration space,

, to a configuration space,

![]() . Cotangent bundles of manifolds are always symplectic manifolds. This is because a canonical

. Cotangent bundles of manifolds are always symplectic manifolds. This is because a canonical

![]() -form or symplectic potential,

-form or symplectic potential,

![]() , is defined on the cotangent bundle to any manifold and we can we can always define a symplectic two form,

, is defined on the cotangent bundle to any manifold and we can we can always define a symplectic two form,

![]() , in terms of the exterior derivative of the symplectic potential,

, in terms of the exterior derivative of the symplectic potential,

![]() (Abraham & Marsden, Reference Abraham and Marsden1980, Theorem 3.2.10).

(Abraham & Marsden, Reference Abraham and Marsden1980, Theorem 3.2.10).

In finite dimensions with

![]() coordinates on

coordinates on

![]() and

and

![]() coordinates on

coordinates on

![]() we can provide local expressions for symplectic potential of the form:

we can provide local expressions for symplectic potential of the form:

(3.7)

(3.7)

which means the symplectic

![]() -form is given by:

-form is given by:

(3.8)

(3.8)

The matrix representation of symplectic 2-form

![]() is given by:

is given by:

(3.9)

(3.9)

where

![]() is the identity. The matrix is easily seen to be skew-symmetric and non-singular.

is the identity. The matrix is easily seen to be skew-symmetric and non-singular.

We can now define a Hamiltonian system as follows. Let

![]() by a symplectic manifold and

by a symplectic manifold and

![]() a

a

![]() function. Define the Hamiltonian vector field,

function. Define the Hamiltonian vector field,

![]() by the condition:

by the condition:

(3.10)

(3.10)

then

![]() is a Hamiltonian system and

is a Hamiltonian system and

![]() is the Hamiltonian function. Given an arbitrary vector field

is the Hamiltonian function. Given an arbitrary vector field

![]() we can write this equation equivalently as:

we can write this equation equivalently as:

(3.11)

(3.11)

The non-degeneracy of

![]() guarantees that

guarantees that

![]() exists. On connected symplectic manifolds any two Hamiltonians for the same Hamiltonian vector field differ by a constant.

exists. On connected symplectic manifolds any two Hamiltonians for the same Hamiltonian vector field differ by a constant.

Now, let

![]() be coordinates for

be coordinates for

![]() so that we have that

so that we have that

![]() then the Hamiltonian vector field takes the form:

then the Hamiltonian vector field takes the form:

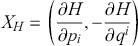

(3.12)

(3.12)

The integral curves of

![]() are the

are the

![]() for which Hamilton’s equations hold:

for which Hamilton’s equations hold:

(3.13)

(3.13)

for

![]() . Thus we can understand (3.10) as Hamilton’s equations.

. Thus we can understand (3.10) as Hamilton’s equations.

The skew symmetry of

![]() together with (3.11) then directly implies conservation of the Hamiltonian function, typically interpreted as an energy function, since for any Hamiltonian system

together with (3.11) then directly implies conservation of the Hamiltonian function, typically interpreted as an energy function, since for any Hamiltonian system

![]() we have that the evaluation of the Hamiltonian function on the integral curves

we have that the evaluation of the Hamiltonian function on the integral curves

![]() will be constant in

will be constant in

![]() :

:

(3.14)

(3.14)

(Abraham & Marsden, Reference Abraham and Marsden1980, Proposition 3.3.3)

We thus see that the basic dynamical features of Hamiltonian mechanics are encoded in the symplectic structure of phase space. In particular, symplectic structure is in an important sense intrinsic to phase spaces and given such structure and an energy function we are guaranteed to be able to define a Hamiltonian system that in turn provides a unique (up to a constant) representation of energy-conserving dynamics. In the following section we will consider a mild generalisation of the conversation property of the dynamics in terms of the conversation of phase-space volume in a Hamiltonian system, as implied via a geometric version of Liouville’s Theorem.

3.2 Liouville’s Theorem and the Poisson Bracket

The defining feature of the geometrisation of mechanics as we have explored it thus far is the consideration of properties of families of solutions in a state space. It is the structure of such families that the symplectic structure of phase space pertains. This feature will prove crucial to our more interpretative discussion of geometric representations of mechanical systems in Section 8. In the present section we will focus our attention a key formal property of families of solutions in phase space: the conversation of phase space volume.

A simple intuitive picture of the content of Liouville’s Theorem can be provided by considering the instantaneous state of a finite ensemble of identical mechanical systems with differing initial conditions, corresponding to a finite region of phase space. Consider the flow of the Hamiltonian vector field at every point in our region and imagine following this flow for a finite time. In such a way we can define a second region of phase space corresponding to the time evolution of our ensemble. The theorem states that the two regions occupy the same volume. In formal terms, following (Abraham & Marsden, Reference Abraham and Marsden1980, Proposition 3.3.4), we can state the result as follows:

Theorem 3.2 Liouville’s Theorem : Let

![]() be a Hamiltonian system and

be a Hamiltonian system and

![]() be the flow of the Hamiltonian vector field

be the flow of the Hamiltonian vector field

![]() . Then for each

. Then for each

![]() we have that

we have that

![]() and thus that

and thus that

![]() also preserves the volume form

also preserves the volume form

![]() .

.

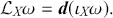

A geometric basis for the theorem is straightforward to establish if we recall that Cartan’s magic formula for closed

![]() -forms

-forms

![]() given in (2.28) was:

given in (2.28) was:

The geometric form of Liouville’s Theorem then immediately follows from the definition of the Hamiltonian vector field, the Lie derivative, and the exterior product, since we have that:

which implies that

![]() which, in turn, implies that

which, in turn, implies that

![]() preserves the volume form

preserves the volume form

![]() . We have thus distilled the geometric essence of Liouville’s theorem to the simple statement that:

. We have thus distilled the geometric essence of Liouville’s theorem to the simple statement that:

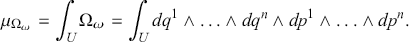

(3.15)

(3.15)

which is true for any Hamiltonian system

![]() .

.

A further important result, which is also often called Liouville’s Theorem, is that the unique Liouville measure

![]() , associated to the volume form,

, associated to the volume form,

![]() , is also conserved under the infinitesimal transformation associated with any Hamiltonian vector field defined on a symplectic manifold. This means that the Liouville measure is conserved by the dynamics and, more generally, under any symplectomorphism (Souriau, Reference Souriau2012, Theorem 16.99).Footnote 2

, is also conserved under the infinitesimal transformation associated with any Hamiltonian vector field defined on a symplectic manifold. This means that the Liouville measure is conserved by the dynamics and, more generally, under any symplectomorphism (Souriau, Reference Souriau2012, Theorem 16.99).Footnote 2

We will return to this important result in the context of our discussion of probability and phase space statistical mechanics in Section 4.3.

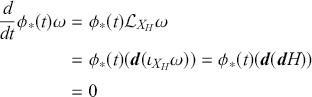

Let

![]() be a symplectic manifold and

be a symplectic manifold and

![]() and

and

![]() be functions on

be functions on

![]() . We can then define the Poisson bracket of

. We can then define the Poisson bracket of

![]() and

and

![]() via the action of the

via the action of the

![]() on the induced vector fields

on the induced vector fields

![]() and

and

![]() :

:

(3.16)

(3.16)

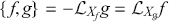

Which can be expressed in terms of the Lie derivative as:

(3.17)

(3.17)

The Poisson bracket of two functions thus corresponds to the Lie bracket of the associated vector fields.

The space of real valued smooth functions over a symplectic manifold forms a particular type of Lie algebra called a Poisson algebra where the Lie bracket satisfies the usual conditions given earlier together with the further condition of obeying Leibniz’s rule:

![]() . Manifolds equipped with such a bracket operation are called Poisson manifolds and all symplectic manifolds can be shown to be Poisson manifolds (the converse does not hold). For more details see (Marsden, Reference Marsden1992, §2).

. Manifolds equipped with such a bracket operation are called Poisson manifolds and all symplectic manifolds can be shown to be Poisson manifolds (the converse does not hold). For more details see (Marsden, Reference Marsden1992, §2).

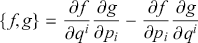

Using the relation between the Lie derivative and Poisson bracket, it is not difficult to show that in canonical coordinates

![]() the Poisson bracket takes the familiar form:

the Poisson bracket takes the familiar form:

(3.18)

(3.18)

(Abraham & Marsden, Reference Abraham and Marsden1980, Corollary 3.3.14)

Let us then consider the Hamilton vector,

![]() field on a symplectic manifold, and associated flow

field on a symplectic manifold, and associated flow

![]() . For any function on the manifold,

. For any function on the manifold,

![]() , we have that:

, we have that:

(3.19)

(3.19)

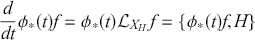

A more concise and familiar expression is to write (3.19) simply as:

(3.20)

(3.20)

which is the equation of motion in Poisson bracket form (Marsden & Ratiu, Reference Marsden and Ratiu2013). We can then express energy conversation in the form

![]() and express that a function

and express that a function

![]() on

on

![]() is a constant of motion relative to

is a constant of motion relative to

![]() by writing simply

by writing simply

![]() .

.

A simple way to approach the more general question of invariants functions is to consider a vector field

![]() that is such that

that is such that

![]() and

and

![]() . That is, a symplectomorphism that preserves the Hamiltonian. Such transformations will preserve the integral curves of

. That is, a symplectomorphism that preserves the Hamiltonian. Such transformations will preserve the integral curves of

![]() and thus the infinitesimal transformations generated by

and thus the infinitesimal transformations generated by

![]() are symmetry transformations in the generalised sense that they map dynamically possible models into dynamically possible models (Gryb & Thébault, Reference Gryb and Thébault2023).

are symmetry transformations in the generalised sense that they map dynamically possible models into dynamically possible models (Gryb & Thébault, Reference Gryb and Thébault2023).

In such circumstances, we will have that

![]() where

where

![]() is the Hamiltonian function defined by relation

is the Hamiltonian function defined by relation

![]() . This means that every symmetry transformations generated by the flow of some vector field

. This means that every symmetry transformations generated by the flow of some vector field

![]() that preserves

that preserves

![]() has an associated conserved charge

has an associated conserved charge

![]() . This result has been called the symplectic Noether theorem and expresses the deep interweaving between symmetry, conversation, and the symplectic structure of Hamiltonian systems.

. This result has been called the symplectic Noether theorem and expresses the deep interweaving between symmetry, conversation, and the symplectic structure of Hamiltonian systems.

3.3 Symplectomorphisms

The final feature of symplectic mechanics that we shall consider is the perhaps the most subtle and certainly the most beautiful. In simple terms, the feature in question is that the canonical coordinate charts that we lay upon a symplectic manifold do not have physical significance. Rather, the structure of a mechanical theory within the symplectic representation is encoded in the Hamilton vector field which is independent of the canonical coordinate chart.

We can capture the content of this idea more precisely by considering the general form of transformations between manifolds defined by diffeomorphisms. Recall that diffeomorphisms are invertible

![]() -mappings between the manifolds:

-mappings between the manifolds:

![]() . Let us consider a pair of symplectic

. Let us consider a pair of symplectic

![]() -dimensional manifolds,

-dimensional manifolds,

![]() and

and

![]() . If the push-forward of the diffeomorphism

. If the push-forward of the diffeomorphism

![]() preserves the symplectic structure, that is, we have that

preserves the symplectic structure, that is, we have that

![]() , then we say that

, then we say that

![]() is a symplectomorphism or canonical transformation.

is a symplectomorphism or canonical transformation.

The most crucial feature of symplectomorphisms is their action on the Hamilton vector field defined via (3.10). The general form of this action can be proved via a theorem attributed to Jacobi i (Abraham & Marsden, Reference Abraham and Marsden1980, Theorem 3.3.9) and can be concisely stated as:

(3.21)

(3.21)

Since, as noted earlier, on connected symplectic manifolds any two Hamiltonians for the same Hamiltonian vector field differ by a constant, we then have that the symplectomorphisms leave the dynamical structure encoded in the Hamiltonian vector field unchanged. The proof of (3.21) is straightforward and instructive so we will provide a brief reconstruction here.

First, re-write Hamilton’s equations (3.10) for the Hamiltonian function given by the composition

![]() :

:

(3.22)

(3.22)

Second, apply the push-forward of the symplectomorphism to the original form of Hamilton’s equations (3.10) using our transfer equations (2.29) and (2.30):

(3.23)

(3.23)

(3.24)

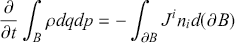

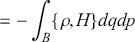

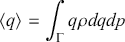

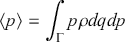

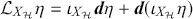

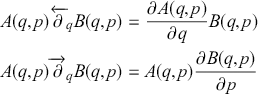

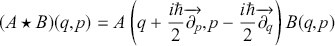

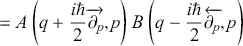

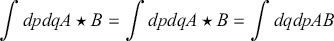

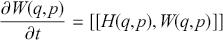

(3.24)