1 Introduction: Putting Climate Change on Trial

Barely a decade ago, the idea of suing governments and corporations for the profound impacts of climate change on human rights was met with skepticism at best and with derision at worst. Legal scholars and practitioners were among the skeptics. Indeed, most legal observers at the outset of the pioneering cases of the early 2010s thought such cases were unlikely to succeed. For instance, when the environmental organization Urgenda sued the Dutch government in 2013 to demand that it increase the ambition of its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions cuts, many observers assumed the case would be too radical a claim for the courts.Footnote 1

In 2019, the Dutch Supreme Court proved the skeptics wrong: It ruled in favor of Urgenda and the 866 citizens that participated in the case as co-plaintiffs and ordered the government to raise the country’s GHG emissions reduction target in line with the prescriptions of the United Nations (UN) Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the goals of the 2015 Paris climate agreement.Footnote 2 Crucially, one of the pillars of the court’s decision was the recognition that the government’s insufficient ambition with regard to climate mitigation violated regional and international human rights duties.

Following this major win, Urgenda went on to establish the Climate Litigation Network in order to advise the growing number of litigants interested in replicating the idea in other jurisdictions. This legal strategy has spread like wildfire. As shown in the full list of cases in the Online Appendix, similar suits have been filed, with mixed results, in Belgium, Canada, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Ireland, Poland, Romania, Russia, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.Footnote 3

Strikingly, human rights advocates were particularly incredulous about climate litigation. As the lawyers who participated in the pioneering cases recalled in our interviews, initially human rights organizations were indifferent and even hostile to the possibility of framing global warming as a human rights issue, let alone going to court over it. For instance, in 2003, when the attorney Paul Crowley was working with the Indigenous leader Sheila Watt-Cloutier and the attorneys Donald Goldberg (Center for International Environmental Law, CIEL) and Martin Wagner (Earthjustice) on their legal petition against the United States government before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) – the first-ever case seeking to hold a government accountable for human rights violations stemming from global warming – they tried to collaborate with some of the largest human rights international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs). They did not get far, as those groups failed to see global warming as a human rights problem. In fact, human rights INGOs tended to view the application of human rights norms to climate change as a distraction – a potential overextension of the rights frame that would take attention away from violations of civil and political rights. In Crowley’s words, “pretty well [the] universal reaction we got from the traditional groups was … those aren’t human rights, these are human rights – it’s individuals who are being tortured, who are in prison, that’s what this is about and you’re diluting that by lumping everything into this [human rights] discourse.”Footnote 4

The legal profession in countries like the United States tended to see the idea as far-fetched. “People thought it was crazy,” said Kelly Matheson, Deputy Director of Global Climate Litigation at Our Children’s Trust (OCT), referring to OCT’s initiative to sue the United States’ federal and state governments in the early 2010s for contributing to the climate emergency in a way that allegedly violated young people’s basic rights as well as their obligation to hold the natural environment in trust for their citizens.Footnote 5

I remember the skepticism beginning to subside around the time that I first participated in discussions among climate and human rights scholars and advocates. At a closed-door workshop at the University of São Paulo in 2016, human rights organizations like Conectas, environmental organizations like Greenpeace, and children’s rights collectives like Alana came together to discuss the feasibility of filing a rights-based climate lawsuit in Brazil. Encouraged by the success of Urgenda in the first instance of the case (including a favorable ruling from The Hague District Court in 2015), as well as by OCT’s filing of its first federal case on behalf of young people (Juliana v. United States) in 2015, workshop participants began to lay the legal groundwork and forge the ties of collaboration that would be needed to pursue climate cases in Brazil. Although the process would take four more years and a second event where we reconvened in São Paulo in 2019, some of those organizations would go on to file one of the pioneering lawsuits of this sort in 2020. The Climate Fund case challenged the Bolsonaro administration’s anti-environmental policies, specifically its decision not to implement a law that had established a fund to finance climate mitigation and anti-deforestation programs in the Amazon region. In ruling for the plaintiffs in 2022, Brazil’s Supreme Court (Supremo Tribunal Federal) advanced what is perhaps the most categorical articulation that any supreme court has offered of climate change as a human rights issue. By declaring that “there are no human rights on a dead or sick planet” and that “environmental law treaties constitute a subset of human rights treaties,” the Supreme Court accorded the Paris Agreement the supra-legal status that human rights treaties have in Brazilian constitutional law.Footnote 6 The filing of Climate Fund helped open the door to a spate of cases that has turned Brazil into one of the most active jurisdictions for this sort of litigation anywhere in the world.

Two decades after the Inuit petition before the IACHR, twelve years after the filing of Urgenda, and almost a decade after that initial workshop in São Paulo, rights-based climate change (RCC) litigation has moved from the margins to the mainstream. In a single month in 2024, the two leading international human rights courts – the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR) – gave their stamp of approval to what scholars have called the “rights turn” in climate litigation.Footnote 7 A few weeks after the ECtHR handed down its first climate ruling – declaring that Switzerland’s insufficient climate policies had violated the rights of elderly women who are particularly vulnerable to extreme heatFootnote 8 – the IACtHR heard from lawyers, scientists, advocates, and youth leaders from across the Americas at a three-day hearing in Barbados, the first of three that the Court convened as part of the process leading to its advisory opinion on climate change and human rights. For those of us presenting to the Court and answering the probing questions of the robed judges, it seemed that climate change itself was on trial.

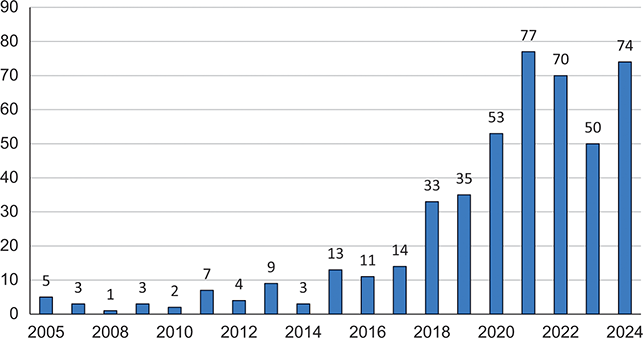

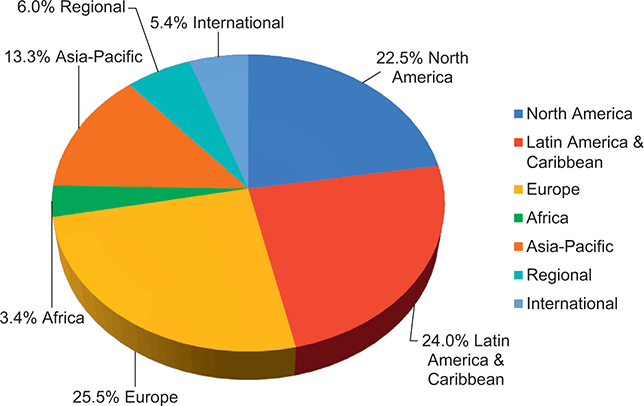

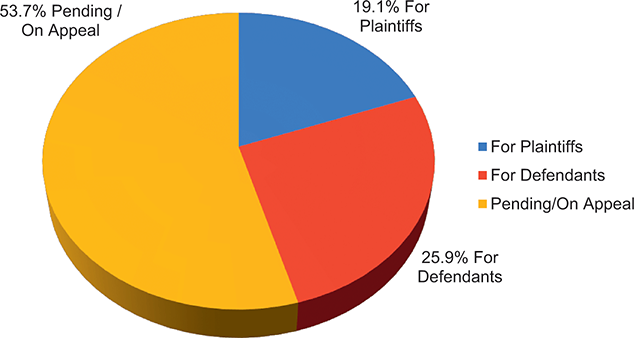

Between January 2005 and December 2024, a total of 467 RCC cases have been filed in 50 national courts and 13 regional and international courts and quasi-judicial bodies. This rights turn has been particularly salient since the mid 2010s. Indeed, 93 percent of cases have been filed since 2015. A wide range of scholarly, advocacy, scientific, journalistic, and funding initiatives have emerged to undertake, document, report, or support this type of legal action.

This Element tells the socio-legal story of this field. Theoretically, it combines insights from global governance, international relations, international law, and legal mobilization studies in order to offer an account of RCC litigation. Empirically, it draws from a combination of sources, including a systematic compilation and analysis of all RCC cases filed before national and international judicial and quasi-judicial bodies, semi-structured interviews with litigants and other key actors in RCC litigation, and participant observation in court hearings, strategy meetings, and public events with RCC actors around the world.

As lawsuits have proliferated, so too have scholarly studies on them. However, the literature on this type of legal mobilization – that is, the mobilization of human rights law and litigation to advance climate action – consists mostly of accounts of one case or a few particularly successful cases.Footnote 9 In the absence of systematic, theoretically informed analyses of RCC litigation, we lack a comprehensive understanding of its origins, legal doctrines, and practical effects. This Element seeks to contribute to filling this gap by studying the universe of RCC cases and offering an analytical account of the rise, trajectory, and results of RCC litigation. In terms of international law and international relations theory, it views RCC litigation as a “transnational legal process,”Footnote 10 that is, as an iterative set of interactions among a wide range of public, private, and civil society actors who formulate, interpret, disseminate, and internalize new norms about the human rights implications of climate change. As RCC lawsuits and rulings have proliferated and articulated new legal norms around the world, the rights turn has given rise to a “norm cascade”Footnote 11 with tangible impacts on climate governance.

This Element also seeks to address another gap in the existing literature. Just as environmental lawyers spearheaded RCC litigation and human rights advocates only later came on board, environmental law and governance scholars have been at the forefront of studies on the matter, with human rights scholars having played a less active role thus far. This asymmetry has resulted in two analytical gaps. First, we have a considerably better understanding of one aspect of RCC litigation (that is, its impact on climate governance) than the other (that is, its effect on human rights norms and concepts). In reality, however, RCC litigation has shaped (and been shaped by) international human rights as much as it has shaped climate governance. As RCC litigants, judges, advocates, UN specialists, and other norm entrepreneurs have reframed global warming as a rights issue and thus influenced climate governance, they have also had an impact on the human rights field by advancing new doctrines such as the rights of future generations and the right to a stable climate system. Therefore, this Element investigates developments in both the climate governance field and the human rights field in order to examine their two-way relationship and hybridization.

Second, since environmental governance scholars have had the leading role in the study of RCC litigation, the literature on the matter has yet to fully incorporate insights from human rights scholarship that are directly relevant to understanding climate litigation. I contribute to filling this gap by applying lessons from the rich literature on the emergence and dissemination of other fields of human rights norms and advocacy that predated RCC litigation, such as socioeconomic rights.

In engaging equally with these two bodies of knowledge and practice, I intend to offer analytical tools and empirical evidence that question the view that the climate and the human rights global regimes are stuck in a dysfunctional equilibrium and that very little can change in both fields.Footnote 12 While RCC litigation certainly falls short of the speed and scale of legal transformation that are required to deal with the climate emergency, and while I dwell on its blind spots and shortfalls, I also show how new rights frames and norms have emerged and cascaded in a relatively short period of time – one that even RCC norm entrepreneurs, let alone the skeptics of the early years, could not have anticipated. Contrary to sweeping statements about the “end times” of human rights, I show how the climate emergency, one of the crucial challenges of our time, has been effectively reframed as a human rights issue.Footnote 13

Sheila Watt-Cloutier, the Indigenous leader who spearheaded the Inuit petition, rightly noted that, despite being dismissed by the IACHR, the case succeeded in bringing the attention of the world to the climate emergency and the plight of the Inuit. The public visibility and impact of the case took her and her lawyers by surprise. “We had cast our line to see what fish we would catch, and instead we caught a whale,” she wrote.Footnote 14 This Element is an attempt to illustrate how dynamic and contingent transnational legal processes can be even when it comes to dealing with the most complex planetary challenges like climate change. At a time when whales – both literal and figurative – are endangered, it shows that they still exist.

1.1 The Argument of the Element

This Element asks the following questions: What accounts for the rights turn in climate litigation? What norms are emerging from this transnational legal process? What are the impacts and limitations of this type of legal action in advancing climate action? Drawing on theories of global governance and legal mobilization, I argue that the rights turn was enabled by the eventual convergence of two very different and distinct global regulatory regimes – climate governance and human rights – that had developed largely along parallel tracks until the mid 2010s. The fresh legal opportunities and additional mobilization frames made available by this convergence facilitated the rise of RCC litigation. They also produced an array of legal norms in this growing field of practice, as well as tangible impacts on climate policy and movements. Although the lead-up to the 2015 Conference of the Parties (COP) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) – and the resulting Paris Agreement – served as the focal point for this convergence, the legal norms and the framing of climate change as a human rights issue originated in longer-term processes, namely the gradual incorporation of environmental issues into the international human rights regime, on one hand, and the revamping of the climate regime that followed the failure of the 1998 Kyoto Protocol and led to the adoption of the Paris Agreement, on the other.

The Paris Agreement is the first global climate accord to explicitly recognize the relevance of human rights in climate action. But rather than its (relatively weak) language on rights, the Agreement’s role in catalyzing RCC litigation lies in the legal opportunities associated with its structure. While the Kyoto Protocol established mandatory targets and timetables for (developed) states’ emissions cuts, the Paris Agreement allows states to determine their own non-binding individual emissions reduction targets. Under the Paris Agreement, climate outcomes depend on states periodically reviewing and increasing their contributions through a “Pledge and Review” iterative process. Currently, even if all states complied with the pledges they made pursuant to the Paris Agreement the planet would almost certainly still warm by about 2.3℃.Footnote 15 This would be dire for the world and could, among other impacts, force as many as a billion people to migrate by 2050 and diminish per capita economic output by between 15 percent and 25 percent by 2100, a trough as deep as the depression of the 1930s.Footnote 16 Collective ambition within the international community must increase accordingly: The current policy trajectory would result in emissions at an estimated 57 percent higher in 2035 than needed to achieve the Agreement’s goal of limiting global warming to 1.5℃ and to avoid the more extreme scenarios of climate change.Footnote 17

With planet-warming emissions still on the rise and the large majority of states missing even their grossly insufficient targets, incentives for states to carry out and upwardly revise their contributions need to come not only from peer pressure (at the international periodic reporting and stocktaking meetings envisaged by the Paris Agreement) but also from domestic civil society pressure, including through litigation. As Keohane and Oppenheimer conclude, “the climate outcomes after Paris [follow] from what can be characterized as a ‘two-level game’, involving a combination of international strategic interaction and domestic politics.”Footnote 18

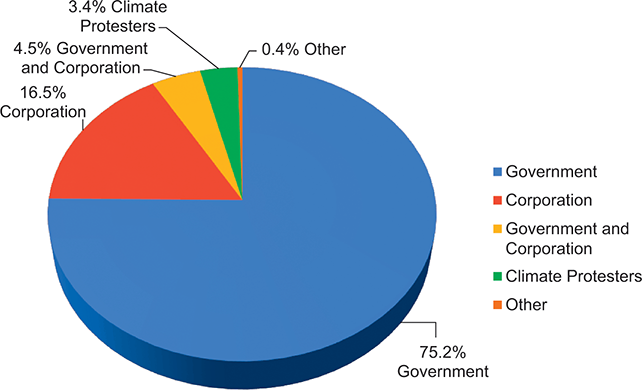

Based on evidence from the totality of RCC lawsuits, I argue that litigants have sought to leverage this two-level structure of opportunities for legal mobilization by (1) asking courts to take the goals and principles of the climate regime (as laid out in the Paris Agreement and IPCC reports) as benchmarks to assess governments’ (and, to a lesser extent, corporations’) climate actions and omissions and (2) invoking the norms, frames, and enforcement mechanisms of human rights to hold them legally accountable to such goals and principles and thus accelerate climate action.

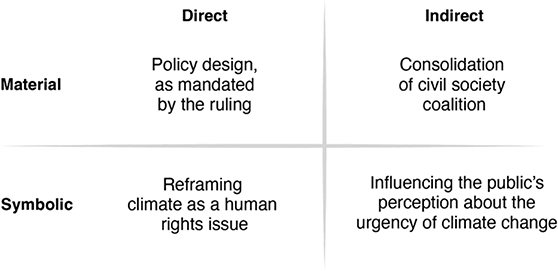

Indeed, most rights-based lawsuits explicitly integrate the standards and regulatory logic of the climate regime, notably the Paris Agreement and the IPCC assessments (as updated by the quickly evolving and improving climate science). This type of RCC litigation can provide material incentives for governments to overcome policy gridlock, increase compliance and ambition, and foster transparency and participation in climate policy. Further, by publicly reframing the problem of climate change as a source of grievous impacts on identifiable human beings and as a violation of universally recognized norms, it can create symbolic incentives for governments and other domestic actors to align their actions with the goals of the global climate regime.

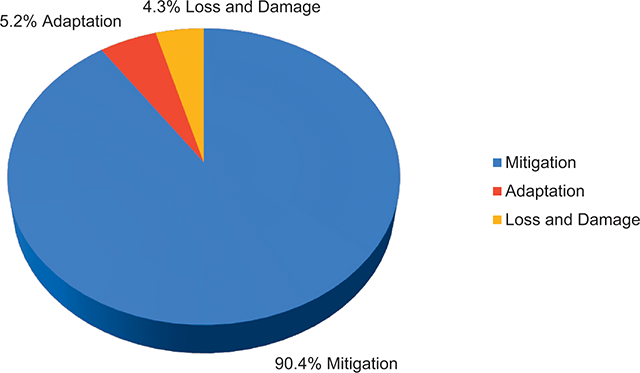

The failure of international diplomacy to produce even modest progress on climate action has exposed the enforcement gaps of the Paris Agreement and prompted a slew of lawsuits that aim to fill some of those gaps – and, increasingly, go beyond the Paris framework. However, climate change is too complex a problem for any single regulatory tactic to adequately address. Rights-based litigation is only one tool in a broader governance toolkit that involves a wide array of actors and approaches, including government representatives engaged in periodic negotiations around the UNFCCC, grassroots activists protesting on the streets to demand climate action and justice, scientists refining the data and sounding the alarm on global warming and its impacts on humans and nonhumans, corporate actors contributing to the transition to clean energies, and so on. RCC litigation has its own challenges and blind spots, including insufficient attention to climate adaptation and reparations as well as the limitations of human rights norms in dealing with the complex causality and temporality of global warming.

1.2 The Element’s Structure and Methodology

The remainder of the Element is divided into five sections. Section 2 places the legal stock and frames of RCC litigation in the context of longer-term processes within the human rights and climate governance regimes – namely, the incorporation of environmental rights into international human rights and comparative constitutional law, on one hand, and the regulatory convergence in the climate regime around the Paris Agreement and the IPCC’s scientific assessments, on the other. Section 3 takes a deep dive into RCC litigation. The first part of the section offers a typology of cases, documents their thematic and regional distribution, and tracks their evolution and results. The second part characterizes the RCC field by examining its actors as well as their roles and interactions. Section 4 offers an analysis of the legal norms and doctrines emerging from RCC lawsuits and court decisions. Although it is too early to make hard and fast inferences about the individual and aggregate impacts of RCC cases, Section 5 proposes a typology of impacts and offers preliminary evidence based on case studies of four of the most prominent lawsuits of this sort. Section 6 recaps the argument, the evidence, and the conclusions about the potential contributions and challenges of RCC litigation in advancing climate action.

A final word on methods: As noted, this Element’s empirical point of departure is the systematic compilation and analysis of an original database of all the RCC cases that have been brought before judicial bodies (including domestic, regional, and global courts) and quasi-judicial bodies (including national human rights commissions and UN human rights treaty bodies). Following the convention in the literature, the list includes cases in which the terms “climate change” and “rights” appear explicitly in the petition or the judicial decision.Footnote 19 The cutoff date is December 31, 2024. The database was compiled and is regularly updated by the research team that I lead at New York University School of Law’s Climate Law Accelerator (CLX). The database is available to the public on CLX’s website.Footnote 20 In order to maximize the chance of capturing the totality of relevant cases, we use a triangulation of sources, including the comprehensive databases on climate litigation curated by Columbia University’s Sabin Center and LSE’s Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment. Our narrower focus on rights-based litigation allows us to carry out a more granular search that identifies additional cases through a combination of internet searches, reading of secondary materials, and interviews with expert informants. Given the explosion and global diffusion of this sort of litigation, our database, just like other well-established databases, needs to be constantly complemented and updated and is likely to miss a few cases at any given time.

In addition to the analysis of the texts of all the petitions and rulings that are available online, this study is based on formal semi-structured interviews with a range of key actors in RCC litigation. The list of interviewees includes litigants, advocates, media experts, climate negotiators, human rights and environmental law NGO leaders, UN special rapporteurs, youth and Indigenous activists, and funders from around the world who have participated in or supported RCC cases.

I also draw on evidence from almost a decade of participant observation in in-person and online meetings and events with actors in the RCC field. In my capacity as a legal scholar and occasional participant in litigation, I have had the opportunity to participate in strategy meetings, court hearings, expert consultations, public panels, trainings, community consultations, and other convenings in venues as diverse as the annual COPs, Indigenous territories in the Amazon, the headquarters of the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva, and communities of climate refugees in Bangladesh. I have also conducted fieldwork with plaintiffs, lawyers, judges, and other relevant actors in a number of countries, including Argentina, Australia, Bangladesh, Barbados, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Dominica, Ecuador, Germany, India, Italy, Kenya, Mexico, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Norway, Peru, South Africa, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

This triangulation of methods combines an external and an internal perspective on this dynamic field of study and practice. I take a step back (or two) from the intense pace and the particularities of any given case in order to offer a global picture of RCC litigation and explain its origins, norms, effects, and shortcomings with the help of concepts and theories from global governance, international law, international relations, and legal mobilization.

This view, however, risks missing the richness of the transnational legal process that underlies it: the myriad local and international actors that participate in it; the social interactions through which new strategies and norms are constructed; the high-paced learning and cross-fertilization among litigants and judges located in very different jurisdictions; and the impact that RCC litigation is having on a range of places and actors, from the climate movement to corporate boards to diplomats and human rights organizations. Therefore, I draw on in-depth interviews and participant observation to offer a more granular, ethnographic view of RCC litigation. This is reflected in vignettes, stories, and deep dives into specific cases that the reader will find throughout the Element.

I would like to think that the combination of numbers, concepts, and stories provides a nuanced account of the use of human rights and courts to address the climate emergency – one that does justice to its notable achievements while also capturing its fits and starts, serendipitous evolution, and open questions. Once a legal or political strategy catches on, it is tempting for analysts and practitioners to see it as an inevitable development and focus on studying or promoting its replication around the world. To counter this temptation, I seek to capture the experimental nature of RCC litigation, including its uncertainties, learning processes, and multifarious outcomes.

This sense of experimentation was there from the beginning. At a side panel in Milan during the 2003 COP, Sheila Watt-Cloutier, Paul Crowley, and Donald Goldberg addressed a crowd that spilled into the hallway. As Watt-Cloutier recounts, in announcing the filing of their petition before the IACHR, “we described the changing reality of Inuit life and the human suffering that accompanied the melting Arctic. The audience responded enthusiastically. The power of the rights-based approach was that it moved the discussion out of the realm of dry economic and technical debate that too often overtakes discussion at UN climate change conferences.”Footnote 21 The reframing of global warming as a human rights issue became even clearer to the Inuit leader during an interview after the event, when she realized that her claim and that of her people could be described as “the right to be cold.” Two decades later, at a time of record-breaking heat waves and unprecedented forest fires, we will embark on a journey into the legal experiment that made the right to be cold, and the new norms it entails, a universal human rights cause.

2 Explaining the Rights Turn: Legal Opportunities and Mobilizing Frames at the Intersection of Human Rights and Climate Governance

On a sunny morning in December 2023, Luís Roberto Barroso, Chief Justice of the Brazilian Supreme Court, addressed a panel of judges and a global audience of legal experts who had gathered in the packed conference room at the Dubai Expo where COP28 was held, as well as in the online room that the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) set up for the occasion. Drawing on case law from around the world and his own opinion in the Climate Fund ruling, Barroso opened his presentation with a confident assessment of the status of rights-based climate jurisprudence. To begin with, why should courts get involved in RCC cases? Barroso offered three reasons. First, “the protection of the environment and fighting climate change is now being perceived as an autonomous fundamental right, as has been recognized by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights.”Footnote 22 He was alluding to the IACtHR’s 2017 advisory opinion, which had indeed framed environmental protection and climate action as human rights duties. Second, courts need to intervene to redress and prevent climate-induced human rights violations given that “majoritarian politics does not have the proper incentive to move because they have short-term objectives.”Footnote 23 And third, according to the Chief Justice, judges “need to protect those who do not have vote or voice: we are talking about children, we are talking about the next generation, we are talking about people who have not been born yet.”Footnote 24

Barroso’s nuanced arguments evinced his long experience as a constitutional law scholar and practitioner. A casual observer could have missed their significance, instead seeing them as a rehashing of classic defenses of judicial activism in the face of government inaction. However, for those of us in the room who had followed the evolution of RCC litigation over the years, his remarks and the circumstances of his talk were anything but ordinary. After all, less than a decade earlier, the proposal to incorporate human rights language into international climate law had been met with such reticence that the Paris Agreement resulting from COP21 made only a passing mention of human rights in its preamble. And exactly twenty years had passed from COP9 in Milan, where the idea of filing an RCC case was so novel that it was treated like breaking news by the media, as we saw in the previous section.

Unlike the event that Sheila Watt-Cloutier and her lawyers had to organize in side rooms to present the Inuit petition, the Dubai panel was a major event at the heart of COP, co-sponsored by UNEP, the Global Judicial Institute on the Environment (GJIE), the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) World Commission on Environmental Law, and other global organizations. The panel featured chief justices and high court judges who spoke about climate law and jurisprudence, oftentimes quoting from landmark judicial decisions from jurisdictions on the other side of the world from theirs. I attended the event as the director of New York University (NYU) Law’s Climate Law Accelerator, which co-sponsored the panel as well as a full-day academic dialogue on climate science and law co-organized with the GJIE. The dialogue brought together climate scientists and legal scholars with judges from supreme and high courts from Brazil, Kenya, Nepal, Pakistan, and South Africa, as well as a judge of the International Court of Justice.

At both events, the judges posed sharp questions and offered thought-provoking insights on climate law issues, from standing and remedies to causality and extraterritorial responsibilities. Watching them and participating in their conversations, it was impossible to miss how much had changed in only twenty years, which is a relatively short period in the slow evolution of international and comparative law. In a clear sign that the RCC field had reached its maturity, high-level judges, who are understandably reluctant to engage publicly with emergent legal questions, were visibly comfortable and indeed keen to speak about climate change as a fundamental human rights issue that required decisive action, including by courts.

How did RCC litigation go from being dismissed by many to a safe topic for dialogue and debate among prominent judges? How did it move from the periphery to the legal mainstream?

2.1 An Unlikely Convergence

The convergence of climate governance and human rights was not a foregone conclusion. Rather, it is a remarkable development, given the litany of failed efforts to create linkages between human rights and climate action and the reluctance of major human rights organizations to take on climate change.Footnote 25

For a quarter of a century, human rights and climate change evolved along distinct and parallel tracks. Before the mid 2010s, no international climate agreement incorporated rights-based language, nor did any UN human rights instrument or domestic court decision frame climate harms as human rights violations, despite mounting scientific evidence on the massive impact of global warming on human life, bodily integrity, property, health, and other basic needs that have been universally recognized as human rights.

The trajectory of both regulatory regimes reflects this reluctance to link human rights and climate change. The 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development avoided any mention of rights in the Rio Declaration on sustainable development, as did the UNFCCC, the centerpiece of the global climate regime.Footnote 26 In 1994, the UN Human Rights Commission, then the UN’s main human rights body, rejected a draft declaration on human rights and the environment that incorporated “the right to a secure, healthy and ecologically sound environment.”Footnote 27

It would take fourteen more years for the UN Human Rights Council (which replaced the Human Rights Commission in 2006) to take on climate change. It did so at the request of the Maldives, the first state to frame global warming as a threat to human rights “to show the world the immediate and compelling human face of climate change,” in the words of then Foreign Affairs Minister, Abdulla Shahid.Footnote 28 The Council requested that the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights conduct the first systematic report on the impact of climate change on human rights.Footnote 29 Even then, the highest-ranking UN officer responsible for promoting human rights expressed ambiguity about the legal linkage. The Commissioner’s report concluded that “while climate change has obvious implications for the enjoyment of human rights, it is less obvious whether, and to what extent, such effects can be qualified as human rights violations in a strict legal sense.”Footnote 30

Against this background, the relatively rapid convergence between human rights and international climate governance since the mid 2010s is a striking turn of events. In 2015, the Paris Agreement included a reference to human rights considerations in its preamble. One year later, a report by the first UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment, a position created in 2015, spelled out in detail the substantive and procedural human rights obligations that states, as a matter of international law, have with regard to climate change.Footnote 31 In 2019, the second Rapporteur went beyond his predecessor by publishing a report on climate and human rights that asserted the “right to a safe climate” and made concrete recommendations for governments to end humanity’s “addiction to fossil fuels.”Footnote 32 And in 2021, the UN Human Rights Commission institutionalized the convergence by creating a dedicated Special Rapporteurship on human rights in the context of climate change.

How did human rights and climate change go from diverging to converging? And how does that convergence feed into the ongoing wave of RCC litigation? I tackle these questions with the conceptual tools of legal mobilization theory – that is, the use of the law by social movements and other actors to promote social change.Footnote 33 Studies of legal mobilization single out two factors that influence social movements’ decision to use litigation and other law-centered strategies: (1) the structure of legal opportunities and (2) the availability of law-centered frames of mobilization. Legal opportunity structures include international and domestic substantive norms (the “legal stock” on the relevant issue area) as well as procedural norms on access to justice that may facilitate or hinder bringing claims to court.Footnote 34 Mobilization frames are mental schemata that codify the experience of a social problem (like global warming) through legal categories (like human rights) and offer an organized way of perceiving and responding to the problem.Footnote 35 Together with litigants’ own resources, these two factors help explain the rise and outcomes of legal mobilization.

The norms and frames that are evident in RCC lawsuits and rulings resulted from internal developments in the human rights and climate governance regimes, namely the mainstreaming of environmental rights in international and constitutional law, on the one hand, and the turn toward a more experimentalist approach in climate governance, on the other. In what follows, I analyze each process in turn. In line with constructivist approaches to international law and international relations, I adopt a dynamic and broad view of norms. As Finnemore and Hollis argue, “norms have an inherently dynamic character; they continuously develop via ongoing processes in which actors extend or amend their meaning as circumstances evolve.”Footnote 36 This process-centered perspective focuses on “how norms evolve, spread and affect behavior.”Footnote 37 Here, norms are understood broadly as “expectations for the proper behavior of actors with a given identity”Footnote 38 – in our case, expectations about public and private actors’ behavior with regards to addressing the climate emergency in ways that are consistent with human rights. Importantly, this means that norms may or may not have the status of legal rules. Oftentimes, the legal standards of emergent global regimes (such as climate governance) are first formulated as norms before they are codified into law through global agreements, national legislation, court rulings, or other means. This has been the case with some of the key legal rules stemming from RCC litigation, such as states’ duty to increase the ambition of their climate mitigation targets in order to protect the rights of young and future generations.

In documenting developments in international environmental rights and climate governance that created suitable conditions for RCC litigation, I use Finnemore and Sikkink’s well-known account of the norm life cycle.Footnote 39 I investigate how new norms have emerged, how they have been debated and disseminated (and how they eventually “cascaded”) around the world, and whether and how they have been internalized by the relevant actors (that is, whether and how they have gained a taken-for-granted status).Footnote 40 I also examine the extent to which they have been incorporated into international and domestic law (be it soft law or hard law), and how the convergence between environmental rights and climate governance constitutes an instance of what Harold Koh calls a “transnational legal process” that set the stage for the reframing of climate change as a human rights issue.Footnote 41

2.2 The Environmental Rights Cascade and Legal Opportunities for Climate Litigation

2.2.1 Forging a New Right: The International Right to a Healthy Environment

Legal opportunities for the rights turn in climate litigation resulted partly from the broader, longer-term process of convergence between human rights and environmental governance. This process approximates a norm cascade, as one country after another added a right to a healthy environment to its constitution, and international human rights law eventually followed suit.Footnote 42 To date, at least 164 countries have recognized a legally binding right to a healthy environment in constitutions, legislation, and treaties, and only 32 have not.Footnote 43

At the global scale, this norm cascade reached its tipping point with the 2021 UN Human Rights Council and the 2022 UN General Assembly resolutions recognizing “the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment as a human right.”Footnote 44 This new universal right was the result of a two-decade process of norm creation. Among the key norm entrepreneurs were states such as Costa Rica, the Maldives, and Switzerland, as well as NGOs like CIEL, Earthjustice, and the Universal Rights Group. Interestingly, this process intersected in unexpected ways with the emergence of specific norms on climate and human rights.

Historically, states in both the Global North and the Global South believed that environmental and human rights issues should be kept as entirely separate fields of global governance. This conviction was clearly on display in the first debates on human rights and the environment that took place at the UN Human Rights Commission (the predecessor to the Council) in the mid 1990s. Starting in 1994, the Commission considered a series of proposals on the matter which, for different reasons, faced stiff resistance from leading countries from both the Global North and the Global South and ended in underwhelming Commission resolutions that effectively thwarted this initial attempt to link environmental and human rights governance at the global scale.Footnote 45

The environmental rights normative cascade was ultimately unleashed by specific concerns about climate change, which had become an existential threat to a number of Global South countries by the mid 2000s. Island countries like the small Pacific Island nations and the Philippines brought the issue of climate change and human rights to the newly established UN Human Rights Council.Footnote 46

The first step in this direction was the adoption by consensus of Council Resolution 7/23 in 2008. This was the first UN resolution to acknowledge that global warming raises “an immediate and far-reaching threat to people and communities around the world and has implications for the full enjoyment of human rights.”Footnote 47 It also requested that the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) prepare the aforementioned 2009 report on the matter.Footnote 48 The report was later followed by Council Resolution 10/4 in March 2009, which took note of the report’s findings and called for the organization of a panel discussion on climate change and human rights, which took place during the Council session of June 2009.

After that point, it became clear that political differences would stall further progress on climate and human rights at the Council, which led some norm entrepreneurs in government and civil society to conclude that the way out of this impasse would be a two-pronged strategy. First, they sought to build the climate–rights link into the climate governance regime. This resulted in the first mention of human rights in a COP agreement. “Parties should, in all climate change related actions, fully respect human rights,” read the agreement reached at COP16 in Cancun in 2010.Footnote 49 Second, in the domain of human rights governance, the strategy before the UN Human Rights Council consisted in returning to a focus on the broader linkage between human rights and the environment.

The institutional formula that unlocked the normative cascade on the environment and human rights was the Council’s decision to appoint, in 2012, an Independent Expert tasked with compiling, analyzing, and clarifying human rights norms relating to the enjoyment of a right to a clean and healthy environment.Footnote 50 The Council renewed the appointment of the Independent Expert (John Knox) for an additional three years and upgraded the mandate to a permanent Special Rapporteurship on human rights and the environment in 2015.

UN Special Rapporteurs (UNSRs) are textbook instances of norm entrepreneurship. In addition to conducting country missions, they produce thematic reports that clarify the state of international norms in their fields. In fragmented or emergent normative fields like the environment and human rights, they must strike a fine balance between norm clarification and norm creation. They need to track closely the existing level of interstate normative consensus, as they must report periodically to and seek the support of the Council and the international community of states at large. However, they also need to provide authoritative guidance on how to interpret and extend existing norms into new domains (like climate change) as well as suggest new norms that could fill the gaps that are common in global governance and international law regimes.

The story of this UN mandate was inextricably intertwined from the beginning with the idea of recognizing a new universal right to a healthy environment. Bearing in mind the successful effort of the UNSR on the right to water that led to the recognition by the UNGA of that right in 2010, state and civil society proponents of the Independent Expert (later Special Rapporteur) mandate on human rights and the environment hoped that it would play a similar role and achieve a similar result. The strategy paid off a decade later, with the 2021 UN Human Rights Council and the 2022 UNGA resolutions recognizing the universal right to a healthy environment.

The environment and human rights cascade is now coming full circle as it falls back down onto domestic law with renewed force. Several of the states that had not incorporated the right to a healthy environment into their legal system have recently done so. For instance, in 2023, Canada introduced substantial updates to its framework environmental law, the Canadian Environmental Protection Act. Among those changes is the explicit recognition of the right to a healthy environment and the government’s duty to protect it.Footnote 51 Importantly for our purposes, the right to a healthy environment has become one of the core arguments in many domestic RCC lawsuits. And it has figured prominently in the hearings and state submissions leading to the advisory opinions on climate change by the IACtHR, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS), and the International Court of Justice (ICJ). Tellingly, one of the four questions that ICJ justices asked during the December 2024 hearings on the matter in The Hague was precisely about the content and implications of the right to a healthy environment.Footnote 52

In addition to the crafting of a new universal right, the UNSR and other norm entrepreneurs have been actively interpreting and expanding the reach of existing human rights to address the ecological emergencies of the Anthropocene. This is the process that former UNSR Knox has called the “greening of human rights.”Footnote 53 I prefer to call it “climatizing human rights”Footnote 54 in order to home in on the ways in which human rights norms, rules, and institutions have been deployed in climate governance, including climate litigation. In investigating the linkage between climate and human rights, I also examine the extent to which a specific normative stream is emerging at the intersection of climate governance and human rights.

2.2.2 Climatizing Human Rights

This transnational process has proceeded in both directions of the climate–rights nexus. Advocates, litigants, courts, UN officials, and other norm entrepreneurs have climatized human rights by (1) assessing the impacts of global warming on the enjoyment of existing human rights and (2) articulating the need for climate policies to be consistent with human rights. The first direction entails assessing how current and future events induced by rising temperatures – for instance, heat waves, floods, wildfires, and hurricanes that are rendered more likely and more frequent by global warming – violate or create serious risks for the rights to life, physical integrity, health, food, water, housing, and other human rights. The opposite direction runs from human rights to climate change and hinges on the argument that effective climate action requires the respect, fulfillment, and protection of human rights. This entails, for instance, examining whether clean energy projects – from the extraction of minerals to the construction of massive facilities for renewable energy production – comply with substantive and procedural rights (e.g., Indigenous peoples’ rights to free, prior and informed consultation and consent). As renewable energies expand rapidly around the world, the deployment of human rights norms to ensure a “just transition” has become an important concern for advocates and, increasingly, courts.

The UN OHCHR has, since the mid 2010s, actively promoted the articulation of the link between climate action and human rights. The decisive language of its 2015 report on the matter illustrates this turn. “Simply put,” concluded the Commissioner, “climate change is a human rights problem and the human rights framework must be part of the solution.”Footnote 55

The OHCHR has not been alone in climatizing international human rights. As noted, the key norm entrepreneurs in this regard have been the UNSRs on human rights and the environment. Given the broad scope of their mandate, the UNSRs initially examined the environment–human rights connection in general, rather than the climate–rights nexus in particular.Footnote 56 The next UNSR, David Boyd, applied this analysis to climate change specifically. In his 2019 report on the matter, he went beyond legal doctrine and pointed to the policy consequences of reframing global warming as a human rights issue.Footnote 57

The culmination of integrating climate change into the formal UN human rights architecture was the establishment of the UNSR on climate change and human rights in 2021. In its initial report to the UN General Assembly in 2022, the first UNSR, Ian Fry, foregrounded the debate on financial compensation for losses and damages incurred by vulnerable countries and communities due to global warming, which would come to dominate intergovernmental negotiations at COP27 in Egypt later that year.

To sum up, in terms of legal mobilization theory, both the advances and the shortcomings of the climatization of rights constitute central components of the legal opportunity structures (the “legal stock”) that litigants, as well as some courts, are mobilizing in RCC cases.

2.2.3 Economic and Social Rights

A third normative stream feeding into the RCC litigation cascade has come from other quarters of human rights law and practice, especially economic and social rights. Lawsuits on rights like health, education, food, and housing exhibit several of the same traits as climate litigation in that they affect a large, geographically dispersed population, implicate numerous government agencies alleged to be responsible for pervasive policy failures that contribute to rights violations, and tend to involve structural injunctive remedies and supervisory jurisdiction mechanisms to monitor compliance with courts’ orders.Footnote 58

The nature of economic and social rights also raises climate-relevant conceptual and legal issues that litigants and courts have been dealing with for several decades. While economic and social rights are justiciable legal norms, they are also programmatic statements meant to guide state and societal efforts at progressively attaining material well-being. Since governmental and societal duties associated with these rights are partially indeterminate, in that they can be fulfilled through a range of policy actions and are subject to resource availability, such duties cannot simply be complied with peremptorily. As noted, progressive realization and open-ended duties are also hallmarks of climate governance after Paris. This explains why RCC litigants and courts have drawn on economic and social rights norms in their submission and decisions.

The UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has contributed to fleshing out the climate–rights connection.Footnote 59 Its 2018 statement on climate change noted that state duties under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights translated into obligations not only to adapt to but also to mitigate climate change. It also brought key principles of human rights law to bear on climate action by asserting that “a failure to prevent foreseeable human rights harm caused by climate change, or a failure to mobilize the maximum available resources in an effort to do so, could constitute a breach” of states’ obligations to respect, fulfill, and protect human rights.Footnote 60

In terms of the other direction of the rights–climate connection, the Committee has also highlighted the need for climate policies and programs to comply with human rights. For instance, in the 2019 joint statement on climate change that it issued with a number of human rights treaty bodies, it noted that in “the design and implementation of climate policies, States must also respect, protect and fulfil the rights of all, including by mandating human rights due diligence and ensuring access to education, awareness raising, environmental information and public participation in decision-making.”Footnote 61

The integration of climate governance and human rights has continued apace. However, as humans (and nonhumans) around the planet struggle to deal with or escape the highest temperatures the Earth has experienced in a million years,Footnote 62 the reality of the climate emergency has become painfully unavoidable. Since the legal stock of climate governance and human rights still falls short of what is needed to address those consequences, advocates have increasingly turned to courts to try to close the gap.

2.3 Riding the Wave: Human Rights Frames in Climate Litigation

The structure of legal opportunities is not the only relevant factor that influences advocates’ decision to take an issue to court. Equally important are the subjective understandings of that issue and litigants’ efforts to frame it in ways that resonate with courts and the larger public. This is evident in RCC legal actions, where the use of human rights language to frame climate harms as having a direct and individualized impact on basic human needs has been as relevant as the role of litigation in providing legal standards and institutional venues to advance those claims.

Indeed, reframing global warming in terms of its impacts on human individuals and communities was the central goal of the first-ever RCC case: the complaint filed by the Inuit people before the IACHR in 2005.Footnote 63 With the legal support of CIEL and Earthjustice, sixty-two Inuit based in Alaska and Canada asked the Commission to declare that, due to insufficient action on climate change and the promotion of fossil fuel extraction, the United States was responsible for human rights violations associated with the profound effects of global warming on the Inuit’s Arctic homeland.

The Commission summarily dismissed the petition one year later. Nevertheless, the case had a long-lasting influence on the articulation of the rights-based mobilization frame that would come to characterize RCC writ large. As Marc Limon notes, the Inuit litigation “introduced the idea that rather than being a global and intangible phenomenon belonging squarely to the natural sciences, global climate change is in fact a very human process with demonstrable human cause and effect. It could thus, like any other aspect of human interaction, be placed within a human rights framework of responsibility, accountability, and justice.”Footnote 64

Although it would take another decade for RCC litigation to take off in earnest, the Inuit petition helped lay the foundation for the emerging norms and frames on climate and human rights. After the petition was filed, the Maldives government reached out to lawyers at CIEL to request advice on drafting a declaration on the matter. The result was the 2007 Malé Declaration, in which Small Island Developing States made the international human rights law case for urgent climate action and exhorted the UN Human Rights Council to take on the issue. This resulted in the aforementioned report of the OHCHR on climate change in 2009, as well as the first Human Rights Council resolution on the matter in 2008.Footnote 65

The work of reframing climate change as a human rights issue involved a transnational advocacy network composed of a wide array of civil society organizations, state representatives, UN officials, funders, and other norm entrepreneurs. On the civil society side, the leading norm entrepreneurs were environmental organizations. They were involved not only in the foundational RCC cases but also in the broader efforts to formulate, disseminate, and internalize the international recognition of the right to a healthy environment and other norms at the intersection of environmental protection and human rights.

As someone who came to environmental law from a background in human rights, I remember feeling slightly out of place during the invite-only expert consultations convened by UNSR Knox early in his mandate to explore the connections between environmental law, climate change, and human rights. Over the course of two sweltering days in Panama in mid 2013, when we discussed normative standards for environmental defenders and other vulnerable groups, it became clear to me that the environment–rights nexus was a familiar topic of conversation for experts from environmental organizations, which made up the large majority of the group. The handful of us who initially came to this conversation from a human rights angle had missed the fruitful discussions taking place among environmental organizations since at least 2009, when the Friedrich Ebert Foundation sponsored an exploratory meeting on climate and human rights that was attended by environmental experts and policymakers, including former Prime Minister of Ireland Mary Robinson.Footnote 66 At a later UNSR expert consultation in Geneva in 2015, despite the welcoming atmosphere and the catch-up work that some of us had done in the interim, the impetus for mainstreaming climate and the environment as human rights issues in global governance was still coming from the environmental organizations in the room, including Earthjustice, Greenpeace, CIEL, and AIDA.

Interestingly, international human rights organizations such as Human Rights Watch (HRW) were conspicuously absent from or took a back seat in these formative years, as they resisted the expansion of the catalogue of rights and continued to focus on civil and political rights.Footnote 67 The contrasting views of human rights and environmental organizations were evident to the lawyers who sought to bridge the two fields through RCC litigation and other tactics. One of them was Peter Roderick, the environmental lawyer who, after working as a legal advisor to Friends of the Earth, co-founded with attorney Roda Verheyen the Climate Justice Programme in 2003 in order to use the law for climate justice. As he recounted in an interview for this study:

[T]here’s an environmental movement and there’s a human rights movement and ne’er the two shall meet. There’s always been this kind of artificial distinction. Although I tended to find that environmental people saw the human rights side of it quite easily and readily but not the other way around, and that’s perhaps not surprising as well because environmentalists saw the power, if you like, the rhetorical and political power of human rights for environmental purposes, whereas human rights activists saw the environment not as about people but as about animals and plants.Footnote 68

As this remark perceptively notes, environmental lawyers understood not only the material power of human rights – that is, the potential of mobilizing human rights law and institutions to pressure government and corporate actors to step up climate action – but also their symbolic power – that is, the potential of the rights frame as a narrative device that would put a human face to the climate emergency.

In retrospect, it is clear that the initial resistance of organizations like HRW to taking on environmental and climate issues was related to the broader debate within human rights circles about the desirability of expanding the catalogue of rights beyond civil and political rights. The domain where this debate most visibly played out was economic and social rights. Aryeh Neier, HRW’s co-founder and former executive director, vocally opposed mixing socioeconomic justice and human rights causes. As late as 2013, Neier opined that taking on distributive justice issues would be “misunderstanding our mission” – apparently speaking not only of HRW but of the human rights movement at large.Footnote 69 Ken Roth, HRW’s executive director for almost thirty years, famously wrote that many economic and social rights causes could not be productively tackled by HRW’s “naming and shaming” methodology, which required clarity about a violation, a violator, and a remedy.Footnote 70

Elsewhere, I offer a critique of this view and its contrast with the dominant view among Global South human rights organizations.Footnote 71 Here I highlight two implications of HRW’s and other INGOs’ resistance to or slowness in addressing issues other than civil and political rights. First, it reveals the priority given to methodology over substance. The strategy of naming and shaming recalcitrant governments into compliance has been central to the success of many human rights efforts. But it blindsided some key organizations to issues that apparently did not fit neatly into it, such as socioeconomic injustice. Moreover, as the world changed rapidly and elected authoritarian leaders rose to power in countries around the world and proceeded to dismantle the rights and democratic rules that brought them to public office, naming and shaming became increasingly ineffective against populist leaders who are very keen to be named but are shameless, and who more often than not also resist climate action. Second, the reluctance to expand human rights’ tactical toolkit helps explain not only HRW’s but also other organizations’ blind spot when it came to understanding climate change as a human rights issue. Indeed, climate change – with its nonlinear causality, planetary scale, and accelerating impacts – challenges the assumptions behind the conventional view of violation, victim, and remedy.

The disconnect was not lost on the environmental lawyers who puzzled at the cold reception they received when they approached human rights organizations to propose collaborations on the early RCC cases. As Roderick put it, those organizations questioned “whether environmental rights is a legitimate area for human rights. Many human rights activists don’t like the idea of diluting – they see it as diluting human rights.”Footnote 72

Just as in the realm of economic and social rights, organizations like HRW that held a restrictive view of the range of human rights issues and methodologies were eventually outnumbered by those that came to see climate change as an existential threat to human rights. Albeit more than a decade after the Inuit petition, many of them, including Amnesty International and leading domestic NGOs, not only joined the effort to reframe climate governance in terms of human rights language but also became litigants or supporters of RCC cases.

The catalytic moment was the lead-up to the Paris climate summit and the negotiation of a new global climate agreement, which provided opportunities for both environmental and human rights organizations to press the human rights frame. Although they aimed for human rights to be included in the operative provisions of the agreement, the ultimate reference to them in the preamble was nevertheless an acknowledgment of the climate–rights nexus. More importantly, the regulatory logic of the Paris Agreement created further opportunities for legal mobilization and domestic pressure on states to comply with and step up their mitigation targets and adaptation commitments. It is in the context of this hybrid climate–rights frame and structure of opportunities that litigation came to play a central role in the development of climate rights, as is evident in RCC lawsuits and rulings.

2.4 The Paris Regime and Rights-Based Climate Litigation

While the legal opportunities and frames of the global human rights regime have been crucial to RCC cases, developments in the climate regime have been equally as consequential to RCC litigation. In analyzing these developments, it is important to consider two core features of climate governance. First, climate change is not a single governance problem but rather consists of many regulatory issues. As Keohane and Victor argue, “climate change” is actually shorthand for several governance challenges: the coordination of emission regulation, the orchestration of common scientific assessments, financial compensation via emission control mechanisms like carbon markets or the Loss and Damage fund, and coordination of adaptation efforts.Footnote 73 Partly because of this, climate governance is characterized by a second trait: Rather than a hierarchically integrated regulatory system built around a single institution or normative framework, climate regulation is a “regime complex” – a loosely coupled set of institutional arrangements that govern narrower issues, from the production of authoritative scientific knowledge (through the IPCC) to states’ mitigation and adaptation goals (through the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement) to the financial regulation of loss and damage compensations and cross-border emissions trading, geo-engineering, and myriad other issues.

The climate regime complex has undergone two key processes that have been particularly impactful on RCC litigation: (1) the normative convergence around the Paris Agreement and its implementation process and (2) the scientific consensus around the 2014, 2018, and 2021 IPCC reports, which articulated the human impacts of climate change with greater clarity and precision.Footnote 74 Studies on transnational environmental advocacy have documented how activists gradually complemented the dominant natural science-based frame with a human-centered frame after the failure of the negotiations that sought to extend the Kyoto model in Copenhagen in 2009.Footnote 75 A parallel human-centered turn took place in internationally authoritative scientific assessments, as evidence of the profound impacts of global warming on humans – including threats to habitats, health, food systems, economies, and political systems – grew rapidly.Footnote 76 The 2018 IPCC report has been especially influential in RCC litigation, as it offers explicit evidence on the need to keep global warming to 1.5℃ (as opposed to 2℃) in order to save hundreds of millions of lives and to avoid other extreme effects on individuals and societies that are associated with that additional half-degree of global warming.Footnote 77

In what follows, in analyzing the evolution of climate governance since the mid 2010s and its impact on RCC litigation, I include under the post-Paris climate regime both the normative convergence around the Paris Agreement and the scientific consensus around IPCC assessments.

2.4.1 The Logic and Setbacks of the Paris Model

The Paris Agreement’s regulatory logic stands in contrast with the pre-Paris regime. In terms of Gráinne de Búrca, Robert Keohane, and Charles Sabel’s typology of global governance, the climate regime went from an unsuccessful effort to establish a comprehensive, integrated regime (Kyoto) to an ongoing attempt to consolidate an experimentalist regime (Paris) that creates incentives for states to act on climate through an iterative process of international negotiations, domestic civil society pressure, emissions reporting based on IPCC methodologies, and periodic stocktaking and peer review of progress on climate mitigation and adaptation.Footnote 78

Regarding climate mitigation, it aims to limit “the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2℃ above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5℃ above pre-industrial levels.”Footnote 79 As for adaptation, the Agreement aims to increase countries’ adaptive capacity to the consequences of climate change already being felt. Through this, it aims to increase resilience and reduce the vulnerability of people to increasing and compounding climate impacts.Footnote 80

In order to achieve the Agreement’s goals, states are required to submit nationally determined contributions (NDCs) which detail the GHG emissions reduction and adaptation targets they set and the measures through which they will achieve those targets. Though states are required to submit these NDCs, their precise content and implementation are voluntary. Nevertheless, the NDCs are supposed to reflect each state’s “highest possible ambition” and “represent a progression” in ambition over time.Footnote 81

Iterative stocktaking processes – where states monitor progress in implementation of the Agreement – are intended to ensure governments act with the ambition and urgency needed to limit global warming and increasingly adapt to climate change. According to the regulatory logic of this model, these processes would create material and reputational incentives for states to articulate adequate commitments and subsequently implement them.

After the failure of the command-and-control model of the Kyoto Protocol, experimentalist scholars tended to view the Paris Agreement as a promising fresh start for climate governance.Footnote 82 The Agreement’s reliance on decentralized and voluntary implementation of its key goals – crucially coupled with peer review and pressure to periodically ratchet up individual states’ contributions – was seen as resembling the model of the Montreal Protocol that successfully dealt with the depletion of the ozone layer.

Given the Paris model’s reliance on transparency and periodic ratcheting up of NDCs, it would succeed only if states have material and reputational incentives to deliver on their promises and to increase their ambition in order to reduce the considerable gap between the mitigation targets to which they committed in Paris and the emissions cuts that, according to the IPCC, are needed to keep global warming between 1.5℃ and 2℃.Footnote 83 However, since those incentives are largely absent in the design and the subsequent implementation of the Paris model, states’ NDCs have been grossly insufficient and there has been no real source of pressure for governments to ratchet them up as envisaged by the Paris Agreement. In practice, these gaps in the climate governance system were laid bare by the first five-year NDC stocktaking in Glasgow in 2021, where it became clear that virtually all governments had failed to implement even their plainly inadequate targets and that they had no plans to increase those targets to the levels recommended by science to avert climate catastrophe. While the agreements that resulted from the Glasgow COP failed to address these gaps, they did shorten the window for governments to propose new voluntary targets from five years to one year.Footnote 84

With the Paris Agreement marking its tenth anniversary, the structural shortcomings of its regulatory model are now painfully clear. These shortcomings are laid bare by the collective failure of state parties to reach a trajectory that would avert dangerous scenarios of climate change: Under the current GHG emissions trajectory, the planet is on track to experience 3℃ of warming this century.Footnote 85 Given that the central aim of the Paris Agreement is to limit warming to approximately 1.5℃, this gap between the current trajectory and the stated goal is evidence that the Paris model is in deep trouble. This conclusion is reinforced by the fact that “there has been negligible movement on NDCs since COP27,” as UNEP concluded in its 2023 Emissions Gap Report.Footnote 86

Climate negotiators who have been deeply invested in making Paris work acknowledge this model’s failure, as of yet, to produce the material progress needed on emissions reductions and other climate goals. One legal advisor to vulnerable countries during COP negotiations concluded that, given the continued absence of sufficiently robust rules around transparency and accountability, parties to the Agreement have settled into a dysfunctional equilibrium that is, as it stands now, unable to deliver the needed ambition.Footnote 87 As 2024 came to a close – marked by the failure of COP29, the alarming news that it was the first year to exceed 1.5℃ above pre-industrial temperatures, and the imminent withdrawal of the United States from the Paris Agreement – Elisa Morgera, the second UNSR on climate and human rights as well as an expert in international negotiations, assessed the status of the climate governance regime in refreshingly candid terms that evince the deep frustration of thoughtful insiders. “We can observe that some states are not acting in good faith in very clear ways, which is the basis of any international regime,” she said. “There is widespread disregard for the rule of international law, and also a very clear pushback on the science, and shrinking of civil spaces at all levels. Basically, the truth is out of the conversation. That is the problem – there is no space at COP for the truth.”Footnote 88

Looking back, from the outset, three structural features were incorporated into the Paris model in a bid to ensure that greater ambition materialized over time: (1) NDCs that would ratchet up over time; (2) an oversight mechanism comprised of rules and procedures that safeguarded transparency, including the Global Stocktake; and (3) climate finance. In the years following the adoption of the Agreement, state parties failed to articulate the concrete rules and procedures needed to fully operationalize each of these essential features, ultimately rendering the model ill-equipped to produce the transparency and accountability needed to secure sufficient ambition.

In particular, the evolution of the Global Stocktake illustrates how the model has entered into a state of stasis that is well off from where it needs to be to achieve the Agreement’s stated aims. When the Agreement was adopted in 2015, there was substantial ambiguity as to how the model would be operationalized, including with respect to the Global Stocktake, which was envisioned as a process that would put pressure on states to ratchet up their emissions reductions through a transparent accounting of progress on mitigation. The dominant thinking, however, was that this ambiguity would be resolved through the implementation process.

That has failed to materialize; instead, the ambiguity has “metastasized,” in the words of a seasoned COP negotiator.Footnote 89 With respect to the Global Stocktake, clear rules and procedures to ensure that the political realm takes into account technical information on the collective consistency of NDCs with the 1.5℃ target have not yet materialized. As a result, the stocktake process has failed to serve as a source of pressure, as originally envisaged, for states to progressively increase their climate ambition. Combined with states’ failure to pledge the needed levels of climate finance and meaningfully update their NDCs, this has produced an equilibrium wherein the international community is seriously off-track from the Paris temperature goal and yet has not yet grappled with how to get back on track.

2.4.2 Climate Litigation: Looking for Ways Forward in the Name of Paris

In retrospect, experimentalists’ enthusiasm for the Paris model was partially unwarranted. As Sabel and Victor have acknowledged more recently, while Paris moved away from Kyoto’s ineffective top-down model, it did not evolve into the central node of the climate governance regime, as states failed to develop a collaborative process of experimentation with climate solutions as well as to increase ambition backed by credible penalties against noncooperative governments. Since “the opposite of a failure does not make a success,”Footnote 90 the Paris model has fallen considerably short of its promise to catalyze climate action. As anyone who attends the annual COP meetings can attest, climate summits have become largely ritualistic convenings whose value is measured more in terms of rhetorical statements than in effective commitments and actions to address the climate emergency.

To my mind, one of the reasons why insightful experimentalists missed some of the design flaws of the Paris model is experimentalist theory’s relative inattention to the role of bottom-up pressure from non-state actors, from social movements to litigants to NGOs. For instance, while they rightly criticized Kyoto’s top-down approach and understood the success of Paris as requiring a “two-level game” that also included pressure for compliance from below, they have largely focused on inter-state negotiations and paid limited attention to the role of the climate movement and climate litigation in exerting bottom-up pressure for states to increase their ambition and deliver on their promises on mitigation, adaptation, and loss and damage.

Elsewhere, I offer a critique of this blind spot and propose a variant of experimentalism that foregrounds bottom-up political and legal pressure for compliance in global governance regimes.Footnote 91 For the purposes of this Element, I argue that the majority of RCC suits and complaints (which focus on emissions cuts) can be understood as strategies to provide the Paris climate regime with procedural and substantive mechanisms that accelerate climate action by translating global mitigation targets into legally binding commitments at the domestic level.

Evidence from RCC cases suggests that litigants have leveraged this two-level structure of opportunities by (1) prompting courts to take the quantitative goals of the climate regime (as specified in the Paris Agreement and IPCC reports) as authoritative benchmarks to assess governments’ climate action and (2) using the norms, frames, and enforcement tools of human rights to hold governments accountable to those benchmarks – and, increasingly, to go beyond Paris by acting with greater ambition and urgency when the Paris mechanisms and goals seem to be grossly insufficient to address human violations that particularly vulnerable communities are already experiencing. As Section 3 shows, this combination characterizes the large majority of RCC cases.

With the benefit of hindsight, experimentalist scholars have also come to the conclusion that the absence of penalties for noncompliance is a design flaw that has thwarted the efficacy of the Paris regime. Although not particularly enthusiastic about litigation, some of them have come to hold a view of the role of Paris that is similar to the one I see at play in many RCC lawsuits. According to Sabel and Victor, the UNFCCC consensus-based process of decision-making that frustrates advances on climate goals is also the source of legitimacy of Paris as the “climate conscience of the world.”Footnote 92 Rather than taking place within the Paris legal architecture, climate action happens in the name of Paris through other institutional mechanisms, like litigation, that put the requisite pressure for compliance with climate goals on governments and corporations.

This view on the setbacks of Paris and the role of courts in helping to address them has been embraced by leading human rights tribunals. Indeed, the ECtHR, in its 2024 ruling on Verein KlimaSeniorinnen v. Switzerland, found that prioritizing climate protection over other considerations was justified, among other factors, by “the States’ generally inadequate track record in taking action to address the risks of climate change that have become apparent in the past several decades.”Footnote 93 In light of this, the Court tellingly concluded that “the question is not whether, but how, human rights courts should address the impacts of environmental harms on the enjoyment of human rights.”Footnote 94

The road leading to this conclusion was paved by more than 400 legal actions that reframed climate change as a human rights issue. The next section takes a deep dive into those cases as well as the actors and tactics behind them.

3 The Shape of the Field: Issues, Venues, Actors, and Strategies in Rights-Based Climate Litigation