1 Introduction

The relationship between moralityFootnote 1 and the godsFootnote 2 has been a steadfast topic of discussion for at least as long as the written word. In fact, the earliest of preserved written records explicitly mention a relationship between prescribed moral rules and what the gods want. Written around the twenty-first century BCE, the oldest known legal code – the Sumerian Ur-Nammu code – claims inspiration from the gods. Inscribed 400 years later, the Code of Hammurabi begins with references to the gods Anu and Bel. In addition to reporting that Anu and Bel assigned the task of overseeing humanity to another god, Marduk, Hammurabi suggests that they also commanded him to promote his laws and to “destroy the wicked and the evil.” In claiming these gods encouraged him to “prevent the strong from oppressing the weak” (Harper, Reference Harper1904, 3), Hammurabi links gods, the moral order, and equality together in ways researchers have theorized since the dawn of the social sciences.

These documents explicitly connect the gods to moral codes, but many questions arise when we treat the nature of this relationship as a social scientific question. For instance, how common is the connection between the gods and morality? Is it present across the world’s religions or is it particular to a narrow subset of religious traditions? How is the connection expressed? Is it found in both beliefs and behavior? Does religion actually contribute to moral behavior or is it just a matter of how people talk? How should we even conceive religion and morality? Why associate gods with how we treat each other? This Element addresses these questions and how the social sciences and other fields have gone about addressing them.Footnote 3

This Element is outlined as follows. Section 2 details the deeper history of thought regarding the relationship between religion and morality. In doing so, it highlights important representative shifts in thinking and method and examines some of the forces that propelled the emergence of anthropological and sociological inquiry. These fields increased our knowledge of the kinds of cultural diversity exhibited by people around the world and created the demand for global, cross-cultural models and methods. Section 3 critically assesses the development of cross-cultural typologies and datasets, two pivotal resources that have had a lasting impact on how we see the relationship between morality, society, and the gods. In Section 4, we’ll then examine the contemporary cognitive and psychological sciences, fields of which have emphasized the importance of the biological foundations of morality and religious beliefs. Drawing from this, we’ll see how the scientific study of religious behaviors (Section 5) and beliefs (Section 6) embraced contemporary evolutionary theory. The concluding section offers some summary points and a survey of the horizon ahead.

2 History and Ethnography

We might never know just how long human beings have contemplated how the divine relates to how they should interact with each other (see Rossano, Reference Rossano2010).Footnote 4 As we saw, the oldest known writing clearly notes this relationship, but it most likely long predates writing. Interestingly, the earliest accounts of the New World’s indigenous populations include details of their religious traditions and moral sensibilities. These observations provide us with a glimpse of how the West’s ongoing fascination with morality and the gods evolved. As we’ll see, the more European observers interacted with non-Western populations, the greater the demand to account for human variation became. Central to this increased demand was the topic of morality and the gods.

2.1 Contact

The earliest written European observations of indigenous, “traditional,” or “non-state” populationsFootnote 5 include some striking claims about religion. For example, in his diary, Christopher Columbus suggested that the native Taíno (Arawak) “would become Christians very easily, for it seemed to [him] that they had no religion” (Dunn & Kelley Jr., Reference Dunn and Kelley Jr.1989, 69). A more nuanced view comes from Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas (1484–1566). Working in the New World throughout the 1500s, de las Casas agreed that American Indians lacked the “true faith” of Christianity, but argued that they would have no trouble learning it because they were so reasonable. In fact, de las Casas devoted much of his life to demonstrating that American natives were remarkably virtuous and their societies were diverse and socially complex in ways that matched or even surpassed the ancient civilizations so often adored by the West:

Did Plato, Socrates, Pythagoras, or even Aristotle leave us better or more natural or more necessary exhortations to the virtuous life than these barbarians delivered to their children? Does the Christian religion teach us more, save the faith and what it teaches us of invisible and supernatural matters? Therefore, no one may deny that these people are fully capable of governing themselves and of living like men of good intelligence and more than others well ordered, sensible, prudent, and rational.

Here, de las Casas rhetorically asks whether Christianity really does contain much of anything in the way of being a good person beyond what American Indians already taught their children. He also notes that the virtues to which he refers are those necessary for self-governance; American Indians already know all that is required to have self-sustaining societies. Alas, not all missionaries agreed and de las Casas remains a notable exception.

Nearly a century and a half later, two missionaries working among the native Martiniquez islanders left some curious insights into their method. One missionary suggested that “having lived without any knowledge of God, [the native Caribbeans] die without hope of salvation. It would be better for us to say that they have no religion at all, instead of describing as a cult of divinity all their trifling nonsense, superstitions, or more exactly sacrileges with which they honor all of the demons who seduce them” (Breton, Reference Breton and Armand de Turner1929 [1635–1647], 5, emphasis added). Another (Bouton, Reference Bouton1635) concurs, noting that the indigenous “do not trouble themselves with knowing what becomes of [the souls of the dead]; at least we have never been able to draw this information out of them” (1). Conveying the level of methodological sophistication of the time, Bouton notes that he and his fellow missionaries have had very little experience with the people, suggesting that they could perhaps “learn more if we were to live among them or they among us. At the present time they are greatly separated from us by inaccessible hills, so that we see them rarely and only when they come by sea to trade with the French” (Bouton, Reference Bouton1635).

Two hundred years later, one missionary who worked among the Abipón Indians of Paraguay held that “the American savages are slow, dull, and stupid in the apprehension of things not present to their outward senses. Reasoning is a process troublesome and almost unknown to them. It is, therefore, no wonder that the contemplation of terrestrial or celestial objects should inspire them with no idea of the creative Deity, nor indeed of any thing heavenly” (Dobrizhoffer, Reference Dobrizhoffer1822, 58). Even after spending eighteen years (1749–1767) among the Abipón, he maintained that they are “accustomed from their earliest age to superstition, slaughter, and rapine, and naturally dull and stupid as brutes.” Yet, in striking contrast to de las Casas’ sentiments, he notes that these “fools, idiots, and madmen” (64) are nevertheless capable of conversion “when the good sense of the teacher compensates for the stupidity of his pupils” (62).

These days, we might be considerably less credulous about past generations’ unsavory conclusions about indigenous peoples and their religions. If we are genuinely interested in what the religions of traditional societies are/were like and whether they were associated with morality, these authors’ motivations and worrisome methods (or lack thereof) should give us pause. Things have changed. The more the West interacted with the rest of the world, the more it had to come to terms with the dazzling variation that people exhibited. Eventually, the field of anthropology offered an antidote to the bigotry of generations past, thus paving the way for a more enlightened view and approach to understanding cultural variation. As we’ll see, however, these contributions did not come overnight. In fact, we’re still in the midst of the transition.

2.2 The Dawn of Professional Cross-Cultural Comparison

Professional anthropology developed as a means to come to grips with the West’s increasing awareness of humans’ remarkable diversity (Harris, Reference Harris1968). While fieldwork and direct inquiry took some time to become standard, the quest to understand the underlying commonalities of humanity amid our overwhelming variation was central to the field’s origins. In fact, anthropology’s genesis was specifically devoted to coming to terms with religious diversity.

In the earliest days of the discipline, researchers were motivated by a few competing cultural evolutionary theories. One was progressivism. A prototypical model of progressivism comes from early anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan (Reference Morgan1877), who argued that “mankind commenced their career at the bottom of the scale and worked their way up...through the slow accumulations of experimental knowledge” (3). The stages of this scale were threefold, including savagery, barbarism, and civilization, each of which have “lower,” “middle,” and “upper” designations.Footnote 6 Across these progressive stages, subsistence – or the way people procure food – “has been increased and perfected,” languages were increasingly articulate, and there was an increased cultural emphasis on private property (5–6).Footnote 7 In this view, cultural evolution was progressive; civilization was obviously inherently better than savagery. But this model of evolution was also unilinear; to become civilized, a society must have passed through a state of barbarism. Morgan’s view also offered a mechanism of change; humanity’s constant tinkering and drive for improvement contributed to a society’s passage from one state to another. Indigenous peoples in relatively smaller societies evidently hadn’t tinkered enough.

It was in this progressivist milieu that came what is often hailed as the founding document of anthropology, namely, E. B. Tylor’s two-volume Primitive Culture (Reference Tylor1871a, Reference Tylor1871b). Drawing from a wide range of cross-cultural observations – albeit of the time’s quality – Tylor’s work disputed the then-held conviction that indigenous societies lack religion. This bears repeating: Tylor spent two volumes arguing, among other things, against the centuries-old idea that “primitive peoples” had no religion.

Like Morgan, Tylor viewed the development of societies as progressive, considering that “the savage state in some measure represents an early condition of mankind, out of which the higher culture has gradually been developed or evolved, by processes still in regular operation as of old, the result showing that, on the whole, progress has far prevailed over relapse” (32). Despite this tendency toward progression, so-called “higher culture” nevertheless contains what Tylor called “survivals,” that is, “processes, customs, opinions, and so forth, which have been carried on by force of habit into a new state of society different from that in which they had their original home, and they thus remain as proofs and examples of an older condition of culture out of which a newer has been evolved” (16). So, while societies might progressively evolve from “lower” to “higher,” there remain vestiges of “lower” traditions in the “higher” populations. One such survival is animism, “the doctrine of souls and other spiritual beings in general” (23). In Tylor’s view, animism is the essence of religion and he spent hundreds of pages addressing the prospect that belief in spiritual beings might be found in all “stages” of cultural evolution.

Despite all of this attention and effort, in a matter of a few short passages, Tylor simply dismisses the possibility that the animism of the “lower” traditions includes a moral component, maintaining that “lower animism is not immoral, it is unmoral” and is “almost devoid of that ethical element which to the educated modern mind is the very mainspring of practical religion” (Tylor, Reference Tylor1871b, 360). Further:

One great element of religion, that moral element which among the higher nations forms its most vital part, is indeed little represented in the religion of the lower races. It is not that these races have no moral sense or no moral standard, for both are strongly marked among them, if not in formal precept, at least in that traditional consensus of society which we call public opinion, according to which certain actions are held to be good or bad, right or wrong. It is that the conjunction of ethics and Animistic philosophy, so intimate and powerful in the higher culture, seems scarcely yet to have begun in the lower.

After appealing to a simple lack of evidence, Tylor reminds us of the virtues of the synthesis of ethics – “actions held to be good or bad, right or wrong” – and animism found in “higher culture.” Models of the good and bad are separate from the religions of the “lower” cultures.

Tylor suggests that this separation accounts for another primary contrast between “savage” and modern religions, namely, their views of death. Here, the adherents of modern religions believe that where one goes after death is contingent on what one does in this life (the “retribution-doctrine”) whereas traditional religions simply go to another place (the “continuance-doctrine”):

Looking at religion from a political point of view, as a practical influence on human society, it is clear that among its greatest powers has been its divine sanction of ethical laws, its theological enforcement of morality, its teaching of moral government of the universe, its supplanting the ‘continuance-doctrine’ of a future life by the ‘retribution-doctrine’ supplying moral motive in the present. But such alliance belongs almost wholly to religions above the savage level, not to the earlier and lower creeds.

Here, Tylor notes that religion can have “a practical influence on human society,” the “greatest” of which is bolstering the moral order. Believing in an afterlife that is based on what you do in this life was one such mechanism bolstering the social order, a mechanism that exists “almost wholly” in societies that have risen above states of savagery.

Again, it is not the case that Tylor denied that indigenous peoples lacked a moral sense. He emphatically holds that both religion and morality are human universals. Furthermore, it was not the case that Tylor saw no relationship between religion and society at all. In fact, he suggests that “Among nation after nation it is still clear how...human society and government became the model on which divine society and government were shaped” (Tylor, Reference Tylor1871b, 248). Presaging later views (see Section 3), Tylor suggests that the structure of a society’s religious worldview is a reflection of their actual social world. This betrays Tylor’s intellectualism, the view that religion functions to help explain the world. In particular, religion’s role was to help people account for themselves.

So over the two volumes that gave birth to a new academic field, Tylor managed to dismantle the then-prevalent idea that traditional populations lack religion. He maintains the view that native religions do not “supply moral motives” that guide constituents’ interactions with appeals to repercussions. This had to evolve independently or, as he argues elsewhere, learned from other “higher cultures” (Tylor, Reference Tylor1892). To the extent that progressivist theory influenced his views of religion, we can surmise that Tylor viewed the supplying of “moral motives” among the religions of those “above the savage level” as an improvement over those of the “earlier and lower creeds.”

There was, however, some explicit resistance to Tylor’s claims about “savage” or “primitive” religions and their connection to morality. For example, Andrew Lang – one of Tylor’s students – was skeptical of his mentor’s “high a priori line that savage minds are incapable of originating the notion of a moral Maker” (A. Lang, Reference Lang1909, xiv). He did not argue against Tylor on the grounds that we should not consider entire cultural groups as having intrinsically better qualities than others. Rather, Lang endorsed a competing view, namely, the “degenerationist” or “devolutionary” theory. This theory posited that all humans were originally united in one common culture and all contemporary cultural diversity represents deviations from that common source (a religiously couched corollary of this view held that all of humanity were once united in Babylon and have since strayed). The goal of anthropology, then, was to search for the original cultural complex and examine how various traits had either maintained or dispensed with the original society’s ways. Of course, this view has long since been discarded, as there is no evidence of such a culture and we know that modern humanity’s common ancestors were foragers who lived in southern Africa some 300,000 years ago (Schlebusch et al., Reference Schlebusch, Malmström and Günther2017).

In this devolutionary spirit, Lang pondered the possibility that beliefs in spiritual beings with “high moral attributes” might be one of Tylor’s “survivals” of our original state and thus could have predated spirits and gods who play “silly or obscene tricks [or are] lustful and false” (xv). In other words, Lang saw beliefs in moralistic gods as not only common, but also indicative of humanity’s once-united cultural state. Drawing upon his review of information about Australian Aboriginal traditions, he points to the “high moral attributes” of their deities, including one deity’s moral precepts. Among them include prescriptions “To share everything they have with their friends” and “To live peaceably with their friends” (181).

Lang also argued against Tylor’s view that “savage high gods” necessarily have their origins in cultural borrowings from “higher” cultures. To do this, he reviewed the then-extant cross-cultural evidence of traditions with gods thought to be models of morality and those believed to directly punish people for engaging in immoral behavior (193–210). Summarizing the state of the field at the time, Lang goes on the offensive: “Anthropology holds the certainly erroneous idea that the religion of the most backward races is always non-moral” (256). In notably stark terms, Lang indicts the then-prevailing view of the nascent field of anthropology. For different theoretical and methodological reasons, the social sciences grew to concur with Lang’s conclusions.

For instance, one of the founders of modern sociology, Émile Durkheim (Reference Durkheim2001 [1912]) saw morality as a central component to both conceptions of the soul (194) and religion more generally. He even treated religion as a mechanism for society:

No society can exist that does not feel the need at regular intervals to sustain and reaffirm the collective feelings and ideas that constitute its unity and its personality. Now, this moral remaking can be achieved only by means of meetings, assemblies, or congregations in which individuals, brought into close contact, reaffirm in common their common feelings: hence those ceremonies whose goals, results, and methods do not differ in kind from properly religious ceremonies.

Here, Durkheim equates “morality” with a society’s sense of “unity” and identity; morality is what holds societies together, makes them what and who they are. As complexes of regulatory practices and beliefs, Durkheim sees religion as a means by which societies maintain this sense of unity. As it includes mechanisms found in the secular world and organizes people into “meetings, assemblies, and congregations,” religion forges moral bonds between people and can thus contribute to the sustainability of a society.

In summary, then, while Tylor saw no relationship between morality and “savage” religions, Lang saw this relationship manifest in beliefs about the gods and their espoused principles, and Durkheim saw it in the way religious institutions contribute to social solidarity. Over the next half century, anthropological consensus grew to side with the facts stressed by Lang and Durkheim, though having long-abandoned the theoretical commitments of Lang and Tylor. A confluence of new developments shaped the social scientific view of religion and morality, namely, ethnographic fieldwork, increased appreciation of the relationship between society and subsistence, and the commitment to understanding societies’ traditions on their own terms.

2.3 Society, Function, and Fieldwork

In the 1930s, fueled by what a generation of ethnographic field researchers had learned directly from traditional people, celebrated anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski witnessed and theorized the close association between religious beliefs, practice, and morality: “Every religion, primitive or developed, presents the three main aspects, dogmatic, ritual, and ethical...It is equally important to grasp the essential interrelation of these three aspects, to recognize that they are only really three facets of the same essential fact” (Malinowski, Reference Malinowski and Strenski2014, 134–135). Even commenting on how long it had taken scientists of humanity to come to terms with this, he expounds on this interrelation:

That every organized belief implies a congregation, must have been felt by many thinkers instructed by scholarship and common sense. Yet...science was slow to incorporate the dictates of simple and sound reason...[that find] that worship always happens in common because it touches common concerns of the community. And here...enters the ethical element intrinsically inherent in all religious activities. They always require efforts, discipline, and submission on the part of the individual for the good of the community.

In this passage, Malinowski sees the relationship between morality and the gods as encoded in religious behavior. Here, he explicitly associates “worship” with exerting individual “effort, discipline, and submission” to benefit one’s community; the “ethical element...inherent in all religious activities” contributes to the “good of the community.” These contributions come at a cost to individuals – they take “efforts, discipline, and submission” and are therefore neither obviously nor immediately in individuals’ immediate self-interest. As we’ll see in Section 5, this economic emphasis of religion’s costs and benefits has since become standard in some contemporary evolutionary views of religion. For now, let’s attend to the theory underlying Malinowski’s observations.

Generally, Malinowski sought to account for the rise and persistence of certain cultural traits. In his view, such traditions fulfill different needs. Defining function as the process of satisfying those needs (Malinowski, Reference Malinowski1944, 159), he spells out an early functionalist theory of culture:

“Culture is essentially an instrumental apparatus by which man is put in a position to better cope with the concrete specific problems that face him in his environment in the course of the satisfaction of his needs.

“It is a system of objects, activities, and attitudes in which every part exists as a means to an end.

“Such activities, attitudes and objects are organized around important and vital tasks into institutions such as family, the clan, the local community, the tribe, and the organized teams of economic coöperation, political, legal, and educational activity” (150)

Here, Malinowski asserts that culture is a tool with which people fix problems. Some of those challenges stem from social organization and domains such as economy, law, and education. Much like Durkheim’s (Reference Durkheim2001 [1912]) view of religion as fulfilling the “need...[for society] to sustain and reaffirm the collective feelings and ideas that constitute its unity and its personality” (322), Malinowski saw religion as addressing “common concerns of the community” (Malinowski, Reference Malinowski and Strenski2014, 137). This conviction – and the theory underlying it – became standard for anthropology. The recognition of this inextricable link between morality and religion became so standard, in fact, that major voices in the field eventually treated it as self-evident.

Consider the sentiments of E. E. Evans-Pritchard (Reference Evans-Pritchard1965), the leading anthropologist of religion of his time. In a poignant critique of previous generations’ efforts, he notes that:

it was [once] held that primitive people must have the crudest religious conceptions...This may further be illustrated in the condescending argument, once it was ascertained beyond doubt that primitive peoples, even the hunters and collectors, have gods with high moral attributes, that they must have borrowed the idea, or just the word without comprehension of its meaning, from a higher culture, from missionaries, traders, and others...Modern research has shown that little value can be attributed to statements of this sort.

Here, Evans-Pritchard identifies the relationship between morality and the gods by their utility as models of morality and virtue. Not only does Evans-Pritchard acknowledge that small-scale foragers “have gods with high moral attributes,” but he characterizes the view that they must have borrowed such a belief from outsiders as “condescending” (see Schebesta & Schütze, Reference Schebesta and Schütze1957, 1–10, for a detailed treatment of this issue).

Indeed, it is not difficult to find links of various kinds between religion and morality in the ethnographies of various societies around the world. A casual scan of ethnographic records suggests many hints and explicit accounts of gods having some association with behaviors that might be construed as “moral”:

the Inuit (global Arctic) Sedna myth is about the supernatural consequences of selfishness where white bears punish people for ancestral Inuits’ moral transgressions (Turner, Reference Turner1894, 261–262)

the Siouan (American Great Plains) notion of wakan tanka (lit. sacred vastness) is recorded in 1896 as an omnipresent and omniscient entity interested in human behavior (Walker, Reference Walker1980, 75) and Siouan religion is indigenously characterized as forbidding “the [avaricious] accumulation of wealth and the enjoyment of luxury” (Eastman, Reference Eastman1911, 9)

in Nuer society (East Africa), “such moral faults as meanness, disloyalty, dishonesty, slander, lack of deference to seniors, and so forth, cannot be entirely dissociated from sin, for God may punish them even if those who have suffered from them take no action of their own account” (Evans-Pritchard, Reference Evans-Pritchard1956, 193)

Paliyan (South India) gods are believed to “punish incest, theft, or murder with an accident or illness” (Gardner, Reference Gardner and Bicchieri1972, 434)

a G/wi (Southern Africa) god’s “anger is expected if some taboos are broken and as a result of certain acts...in order to show man’s lack of arrogance and thereby to avoid [N!adima’s] displeasure...Death and other misfortunes are sometimes attributed to his anger” (Silberbauer, Reference Silberbauer and Bicchieri1972, 319)

some members of the related Dobe Ju/’hoansi report that spirits “expect certain behavior of us. We must eat so, and act so. When you are quarrelsome and unpleasant to other people, and people are angry with you, the //gangwasi see this and come to kill you. The //gangwasi can judge who is right and who is wrong” (Lee, Reference Lee2003, 129–130)

among the Dogrib (Canadian Northwest), “Wrongdoing [e.g., ‘slacker[s], womanizer[s], and other transgressors of...norms’] might incur the visitation of supernatural illness” (Helm, Reference Helm and Bicchieri1972, 79)

elements of moralistic punishment are in Matsigenkan (northwestern South America) folktales (Izquierdo, Johnson, and Shepard Jr, Reference Izquierdo, Johnson, Shepard Jr, Beckerman and Valentine2008; A. Johnson, Reference Johnson2003).

For at least two reasons, none of them would surprise the likes of Malinowski and Evans-Pritchard. First, they witnessed theorized the moral content and/or function of traditional religions first-hand and theorized about it. Second, they would appreciate that these observations come from ethnographic fieldwork, synthetic anthropological works, and directly from indigenous people themselves rather than explorers, missionaries, and armchair anthropologists. Even if these were exceptional views, the content of these observations nevertheless run counter to the strong sentiments of early missionaries and social theorists like Tylor.

So, the first century of anthropology included a debate about how central and universal morality was in the religious sphere. Even contemporaneous researchers with access to the same ethnographic record achieved remarkably divergent views, often even drawing from the same theoretical orientation. How then would we go about reasonably reconciling these views?

From a methodological perspective, we could be skeptical about any position; both generalize about a wide range of traditional societies and it is easy to make sweeping generalizations or cherry-pick examples to substantiate one’s views. The essential question here, then, is how safe such conclusions are. Framed probabilistically, the question becomes: what is the likelihood that a small-scale society links morality to their religious tradition? To address this question, the subsequent generation of social scientists developed cross-cultural datasets. As we’ll see, these resources allowed researchers to assess global patterns of culture, thus bringing a more systematic empirical approach to bear on such debates. However, they also carried considerable baggage that subsequent generations unfortunately inherited.

3 Societal Typologies and the Quantification of Culture

In their quest to understand human variation, previous generations developed standards for documenting and theorizing about the world’s cultural traditions.Footnote 8 As this documentation increased in detail and sophistication, researchers increasingly abandoned the erroneous conceits of progressive models of cultural evolution. The more cross-cultural data anthropologists accumulated, the less satisfying casual observation and hasty generalizations became. Newer, more nuanced models linked cultural traits together. Furthermore, theory steadily became more inclined to examine traditions in light of the functions they served and the processes that contributed to their development.

Are there common cultural traditions found around the world? What explains them? Are some kinds of societies more likely to have some specific cultural traits than others? Why? With the expectations of rigorously collected ethnographic data and a global perspective afforded by the belvedere of academia, researchers began to categorize societies and cultural traits in discrete and formally comparable ways. This facilitated the quantitative study of sociocultural evolution. As we’ll see, the link between religion and morality played a major role in the development of these tools.

3.1 Societal Typologies

Societal typologies subsequent to those of Morgan and Tylor grounded human organization in a society’s economy. Rather than the gradual trial-and-error improvement of making a living as suggested in previous models, newer approaches explained many cultural traits by virtue of the way societies made a living. One influential model came from Elman Service (Reference Service1962), who discussed four society types – bands, tribes, chiefdoms, and states (Table 1). These society types were linked to subsistence; bands are foragers, tribes engage in horticulture or herding (pastoralism), agriculturalists tend toward chiefdoms, and industrialized states typically have market economies. In this model, the domestication of food represents a primary mechanism for increasing population size. The intensification of food production fostered economic and professional specialization; as we go from bands to states, there are more possible roles that people can fill by virtue of the fact that fewer people can produce enough to sustain greater numbers.

Table 1 Service’s model of societal variation with Wallace’s corresponding religious types. Economic specialization increases from bands to states. Note that population sizes are inferred based on Service’s discussion throughout the text (see pp. 58–59).

| type | economy | pop. size | decisions | religion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| band | foraging | 25–100 | egalitarian | shamanic |

| tribe | hort./herding | collective | communal | |

| chiefdom | agriculture | representative | Olympian | |

| state | industrial | lots | top-down | monotheistic |

Again, as is appreciated now, such a model is not progressive; societies are not naturally developing toward inherently better industrial states and there are many pathways to societal change. There have been many cases of massive state-level societies breaking down into agglomerations of small-scale societies (e.g., the Maya) or complex chiefdom societies from previously horticultural-hunting contexts that became subsistence hunters when introduced to new contexts (e.g., Siouan groups dominating the American Great Plains and adopting bison-hunting).

Service’s scheme continues to be useful; while crude and can still tempt us to think progressively, this model nonetheless helps generate new inferences about a wide range of cultural traits, particularly when coupled with other theoretical frames and observations (for a more contemporary view, see Kaplan, Hooper, & Gurven, Reference Kaplan, Hooper and Gurven2009). If we know how a society procured food, for example, we can make reasonable predictions about its predominant form of political decision-making. Bands, for example, are typically egalitarian and make decisions collectively (Boehm, Reference Boehm1993) whereas states tend to make decisions in a top-down fashion. Furthermore, the model offers a mechanism – food production – as an important driver of societal change. In other words, if we know something about how a society makes a living, we can predict a lot about cultural forms, including aspects of religion.

Take, for instance, how anthropologist A. R. Wallace (Reference Wallace1966) built upon this general scheme. While he did not explicitly appeal to Service’s model, Wallace’s typology of religions certainly corresponds to it (see Table 1). Here, the content and structures of religion and society co-evolve; egalitarian bands with a more equitable distribution of decision-making power also tend to have shamanic traditions where spirits are distributed throughout the landscape. In contrast, the structures of chiefdoms correspond to structures of polytheism where important figureheads are “at the top” with increasing numbers of those with less influence are “at the bottom.” According to the model, states – societies with hyper-concentrations of power – trend toward having monotheistic high gods with supreme power. Like we saw with Tylor and Durkheim, Wallace’s model really suggests that these religious types are reflections of how a society is structured.

Regarding the relationship between morality and religion, Wallace’s view is in keeping with the anthropological wisdom of the time, asserting that “In every society there is a sacred oral or written literature which asserts what is truth in religion. This code...contains the moral injunctions of prophets and of gods” (57). Thus, the moral dictates of the gods are central to all religious traditions. Further, he notes that “Contrary to some popular impressions and to Tylor’s early summary of observations (1871a, 1871b), even the most primitive peoples often regard violation of the moral code as entailing the threat of supernatural punishment,” qualifying that “Supernatural sanctions for morality are more likely to be invoked in societies where there are, between persons, considerable social differences derived from differences in wealth” (193). Unlike his predecessors, Wallace could appeal to cross-cultural, quantitative data. Citing a landmark achievement, namely, sociologist Guy Swanson’s (Reference Swanson1964) cross-cultural study, The Birth of the Gods, Wallace effectively united the anthropology of religion with a revolution in cross-cultural inquiry.

3.2 The Birth of Cross-Cultural Datasets

As the Service-Wallace model suggests, once worldwide observations of other, non-European populations became more commonplace, patterns in the beliefs, practices, and other cultural traits became easier to make. However, while Service and Wallace’s models are useful, how reliable are they? How representative are they of the populations they claim to describe? How reliable and robust are the relationships we think are out there? As noted earlier, it is easy enough to cherry-pick examples and counter-examples to support or refute a specific argument. It is another task entirely to systematically and reliably assess whether a pattern exists.

Because of the uncertainty and informality associated with single-shot qualitative observations, social scientists increasingly embraced the used of quantitative data and its analysis (Murdock & White, Reference Murdock and White1969). Interestingly, this demand led to the compilation and development of cross-cultural repositories and databases of materials about far-flung populations. Central to their process was the quantification of previous generations’ qualitative reports.

As it turns out, one of the first – if not the first – quantitative cross-cultural databases was devoted to understanding the relationship between religion and society (for what may be the first cross-cultural database using categorical codes, see Murdock, Reference Murdock1957). Swanson’s The Birth of the Gods (Reference Swanson1964) represents a remarkable step forward in the social sciences.

Swanson and his two assistants scoured ethnographic materials from fifty diverse societies from around the world (32–37). Focusing on a host of variables ranging from whether societies had debt and social classes to supernatural sanctions for morality and beliefs in magic, this small team converted qualitative ethnographic observations into quantitative data (e.g., Is reincarnation present?; 0 = absent; 1 = present – in human form; 2 = present – in animal form).Footnote 9 The book then applies a variety of statistical tests to assess various hypotheses of interest.

Swanson’s dataset – and others like it – is really about the available and/or sampled ethnographic record, not necessarily the ethnographic reality behind it. We’ll revisit this point later, but it helps to remind ourselves how some information might be lost, ignored, or created by virtue of the production of ethnographic materials and its subsequent quantification (Cronk, Reference Cronk1998; Watts et al., Reference Watts, Jackson and Arnison2022). What happens when an ethnographer doesn’t mention a particular trait? In Swanson’s view, we might treat the absence of evidence as evidence of absence for two reasons (51). First, he assumes that Western ethnographers would be likely to report, for example, a “high, monotheistic god” because such gods are similar to their own cultural backgrounds. Second, he assumes that ethnographers would only bother to document the absence of a trait only when that absence is surprising or notable in some important way. He recognizes that maintaining this set of assumptions “will undoubtedly lead us into some errors,” though the severity and prevalence of such errors are left unaddressed. Swanson ultimately appeals to the utility of the assumption on the grounds that a proper study needs data, that is, “we need as many judgements about as many of the societies in our sample as possible” (51–52). So, there might be some errors by adopting these assumptions, but to him, the benefits of doing a study with more data outweigh the costs of introducing errors in that data.

To his credit, Swanson makes these assumptions explicit. But how safe are they? We might just as easily assume the converse idea that ethnographers would not bother reporting things that are common or well understood by their anthropological peers. Considering the ethnographer’s primary job is to document and account for human variation, they might naturally emphasise the differences found in the societies they study rather than the similarities, even if they are present (Naroll & Naroll, Reference Naroll and Naroll1963). Furthermore, it might be the case that some topics are ignored because of more salient activities. So, for example, beliefs in a “high god” might be present in a society, but they might have been ignored because, say, ancestor spirits were more often discussed in daily activities and ritual activities were more notable. We’ll return to this issue later. Keeping these issues in mind, let us first examine Swanson’s theoretical motivations behind the topic at hand.

In the chapter “The Supernatural and Morality,” Swanson briefly surveys the intellectual history of the topic, suggesting that “The people of modern Western nations are so steeped in these beliefs which bind religion and morality, that they find it hard to conceive of societies which separate the two” (153). He proceeds to discuss Tylor’s, Malinowski’s, and other influential thinkers’ views on the subject (see Section 2), concluding that “We can be certain that Tylor’s view is not universally valid for primitive societies, but that it does fit some of them” (155). Swanson suggests that much of the disagreement between Tylor and Malinowski are to be found in their unclear and inconsistent use of “morality.”

Unfortunately, Swanson does not help us much in the effort to clarify what “morality” refers to. In summarizing the differences between Tylor’s and Malinowski’s views, he rests on the following: “Morals are social rules which specify the behaviours required of those who enter moral relationships and seek to maintain them” (156) and “a moral relationship exists to the extent that self-conscious beings intentionally and freely facilitate the achievement of one another’s goals and intentionally and freely accept this facilitation from each other” (157). So, “moral relationships” are partnerships that allow the involved parties to achieve each other’s goals. “Moral rules” are the guidelines that must be followed to facilitate the moral relationships. It is anything one ought to do when helping others achieve their desires. Thus, this particular definition allows just about anything interpersonal to fall under the aegis of “moral” (e.g., sitting in one’s seat in a classroom would thus be a “moral” issue with respect to facilitating a teacher’s job).

Drawing from this, he concludes that “It would be strange indeed if the deities which represent sovereign groups were totally indifferent to actions which violate the bonds of loyalty that bind members to those groups” (159) and while “the ethnographic evidence supports the judgment that moral relations between particular individuals are not always subjected to supernatural sanctions...in some respects, the supernatural is frequently involved in supporting human morality” (ibid.). Thus, there remains variation to be explained. In his quest to understand this variation, Swanson offers three theoretical predictions:

“Any important but unstable moral relationship between individuals...will evoke supernatural sanctions to buttress their fragile association” (159)

“Supernatural controls cannot be exercised over interpersonal relations unless the number of persons having interests peculiar to themselves has become great enough to create a large number of social relations in which people interact as particular individuals, rather than as members of some group” (160)

“Supernatural controls are exercised over interpersonal relations in all societies, but this belief becomes explicit only when the conditions cited under the first hypothesis force people to become aware of the facts” (160).

In terms of theory, while these three hypotheses all have functional implications inasmuch as they suggest that appeals to supernatural punishment can have an effect, Swanson stresses the conditions under which gods and other spiritual agents (e.g., karma or mana) will be explicitly associated with moral relationships: (a) when moral relationships are important and delicate; (b) when there are considerable competing interests among individuals to manage; and (c) when people are aware of how important and delicate their moral relationships are. The third hypothesis is notable for a few reasons. First, it declares that all societies exhibit supernatural controls over interpersonal relations. Second, it brings hypotheses to a measurable, almost psychological level by identifying the conditions under which religion becomes explicitly – rather than tacitly – about morality. We will revisit this distinction between religion’s implicit and explicit moral relevance in the next section.

Swanson admits that he can’t directly test these hypotheses using his data. Instead, he operationalizes (i.e., converts concepts into measurable units) moralistic supernatural sanctions by examining the reported presence of supernatural sanctions across indices of things that might threaten moral relationships such as “debt relations, social classes, [and] individually owned property” (162). This is a curiously narrow subset of the moral domain! He also admits that one of the more sizeable problems with coding this data is

the absence of direct evidence that particular relationships between people meet our criteria of morality or that the persons concerned are interacting as particular individuals rather than as members of a group. All one can say is that the records contain those instances in which sanctions of supernatural origin are applied to persons because these persons help or harm other members of the same society.

In this admission, “moral” now means “help or harm,” thus offering something a little more concrete and precise in the way of what “moral” means that he offered earlier. In terms of method, Swanson once again points to the gulf between ethnographic reality, theoretical constructs, their operationalization, and the source material used to create data. Given these sizable caveats, what do the data show?

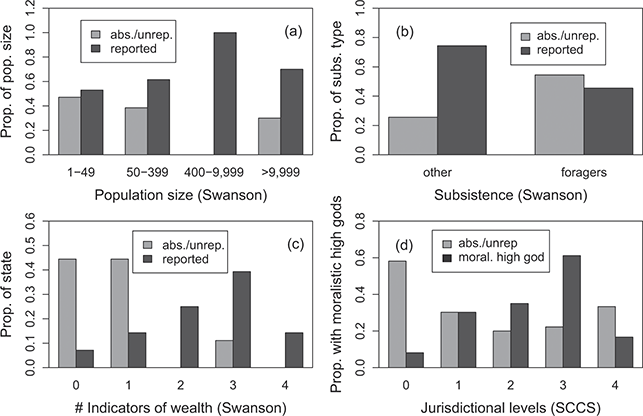

According to Swanson’s data, 67% of the groups have sampled records mentioning supernatural sanctions for behaviors that “help or harm other members of the same society” (33/49 as one’s population size was uncertain). That means that only sixteen societies’ records lacked mention or reported the absence of supernatural sanctions for morality. Figure 1a shows this across population sizes. If we take Service’s model seriously, even among those smallest of societies with populations under fifty people (likely foragers), there are roughly as many with (53%) moralistic supernatural sanctions as those without (47%). In other words, half of the smallest societies were reported to have moralistic supernatural punishment. Furthermore, it is clear that the presence of supernatural sanctions for morality is at least at this level across population sizes. Figure 1b shows that roughly half (45%) of all societies whose principal source of food is collecting and gathering, fishing, or hunting have reported instance of moralistic supernatural punishment.

Figure 1 Barplot of distribution of supernatural sanctions for morality across (a) population sizes, (b) foraging, and (c) indicators of wealth in Swanson’s data set. Panel (d) is the distribution of absent or unreported “high” gods and reported moralistic high gods across number of jurisdictional levels (i.e., column proportions from Table 2; missing values not considered) in the SCCS.

Swanson also assessed the relationship between the number of indicators of wealth disparities and the presence of supernatural sanctions for “help or harm [toward] other members of the same society” (164; Figure 1c). Out of the fifty societies studied, only thirty-seven had “pertinent data” (168).Footnote 10 While the numbers are low, 76% of this truncated sample have records indicating the presence of supernatural sanctions, suggesting that “these sanctions are widespread in our sample” (168). After conducting a multitude of tests, Swanson concludes that, “Contrary to Tylor’s formulation, a considerable proportion of the simpler peoples do make a connection between supernatural sanctions and moral behavior” (174, emphasis added).

In terms of accounting for the variation in types of beliefs, moralistic “sanctions are more likely to appear in societies in which there are interpersonal differences according to wealth” (174). The most generous we can be about this particular finding is that there is a correlation; we do not know what causes what (for critique, see Peregrine, Reference Peregrine1996). Do such beliefs develop in response to the accumulation of wealth? Do they function to reduce inequality? Or do such beliefs curb self-indulgence? These two traits – moralistic supernatural sanctions and wealth disparities – could also co-evolve. As we’ll see, subsequent efforts have tried to address these questions more rigorously.

Swanson’s text also includes a chapter dedicated to monotheism, which he defines “as the first cause of all effects and the necessary and sufficient condition for reality’s continued existence” (55). Here, Swanson also defines “high gods” as creator deities that are “ultimately responsible for all events, whether as history’s creator, its director, or both” (56). Merging these two criteria into a single “high gods” construct, Swanson finds that the presence of such gods tends to be associated with societies with more sovereign, hierarchically structured organization and those with more than a single sovereign communal group (Figure 1d). This resonates with the Service-Wallace model; hierarchical societies with bureaucracies have gods that resemble chairmen. While these aspects of social complexity indicate the presence of high gods, others, such as occupational specialization, are less clear. As it turns out, Swanson’s high gods variable contributed to resources that spawned decades of cross-cultural research. Unfortunately, due to the heavy reliance on “high gods,” this research lost sight of the global ubiquity of moralistic supernatural sanctions that had been appreciated for generations and tested and confirmed by Swanson’s important contribution.

3.3 High Gods, Morality, and Social Complexity

With Swanson’s help, anthropologists Murdock and White developed the Standard Cross-Cultural Sample (SCCS), a cross-cultural database of many variables regarding 186 different societies. The SCCS is a calculated subsample of the more encompassing Ethnographic Atlas (EA, Murdock, Reference Murdock1967). Murdock and White designed this subsample specifically to avoid what is known as “Galton’s Problem” (Naroll, Reference Naroll1961, Reference Naroll1965).

In response to a lecture by E. B. Tylor (Reference Tylor1889), Francis Galton raised the issue that when trying to functionally explain the cross-cultural presence of certain traditions, one must be sure to attend to the possibility that cultural parentage or borrowing might explain why two or more populations share the target trait. Having a massive number of populations in a database – some of which are interacting with each other, were historically the same group, or are learning traits from a common source (e.g., colonial powers or missionaries) – might muddy any analyses that presume cultural independence.

Like Swanson’s data, the EA and SCCS consist of quantitative data derived from qualitative reports. Unlike Swanson’s data, however, both draw from a wider range of source types beyond ethnography, including reports from missionaries and travelers and holy books (e.g., the Bible is one source for the Hebrews).Footnote 11 Furthermore, while the data in The Birth of the Gods were largely devoted to religious data, the EA and SCCS have only a few variables pertaining to religion and only one variable that addresses gods’ association with morality.

Coming directly from Swanson (Reference Swanson1964), the “high god” variable (V34 and V238 of the EA and SCCS respectively) indicates the presence of various states of having a “high god” as recorded and coded in the records from which the EA and SCCS drew. According to these sources, a “high god” is: “a spiritual being who is believed to have created all reality and/or to be its ultimate governor, even though his/her sole act was to create other spirits who, in turn, created or control the natural world” (Swanson, Reference Swanson1964, 210). In addition to “data unavailable” (see Dow and Eff, Reference Dow and Eff2009 for discussion of missing data in the SCCS), there are four categorical options as possible values for high gods:

0. absent or not reported [in the materials]

1. present but not active in human affairs

2. present and active in human affairs but not supportive of human morality

3. present, active, and specifically supportive of human morality

Recall the earlier issue regarding the absence of evidence Swanson raised. Since these are data coded from qualitative materials – and we know a little about the quality of such records (Section 2) – we might adopt a little more caution and maintain that just because a trait is not reported doesn’t mean it should be considered absent. The authors of some sources might have overlooked a trait, perhaps they didn’t ask, or perhaps they had their own agendas. In fact, the sources characterizing the Abipón Indians as “slow, dull and stupid” were among those that led to the coding of their high gods as “absent or not reported” in the EA and SCCS! Oddly, this coding scheme explicitly conflates the options of “absent” and “not reported” and without looking at the source material, we wouldn’t know why the data wound up being coded this way. Even when we do, the answers are not immediately forthcoming.

Furthermore, as previous generations would anticipate, there are numerous cases of gods and spirits that are clearly associated with morality that aren’t specifically high gods. Consider the traditionally horticulturalist Orokaiva of Papua New Guinea and the foraging Ainu of Japan. Both societies are coded as having “absent or unreported” high gods. The former are coded as having one level of jurisdictional hierarchy, while the latter are coded as having two. Yet, the literature used to code these values reveals an explicit association between traditional gods and morality:

If the Orokaiva, by and large, order their lives by the same moral principles, they would explain this by their common belief in certain demigods whom they all regard as their ancestors and as sources of authority, and who created certain institutions embodying moral norms to which they all subscribe. Not only do they obey the precepts of these demi-gods, they also re-enact their feats in ritual and identify with them during ceremonies, and in many of their regular expressive activities (Schwimmer, Reference Schwimmer1973, 51).

The power of the deities is demonstrated to the Ainu not only through their beneficial power in providing abundant food and general welfare but also through their power to punish by causing an illness if offended … The ultimate cause of these illnesses lies with humans, who can please these beings so that they remain beneficial or benign or break a taboo and bring about their own misfortune. Thus, an illness is incurred by breaking moral codes against deities or other soul-bearing beings of the universe, or by breaking social codes against fellow Ainu with the use of offensive remarks.

So, even if these traditions lack high gods, they do include gods that are unambiguously associated with morality. As such, if our interest lies in the relationship between morality and the gods, relying on the high gods variable will mislead.

With these words of caution in mind, what do the data tell us? Table 2 reports the raw data across different levels of “jurisdictional hierarchy,” a variable often used to denote social complexity. Just by eyeballing these data, we can see that over half of the societies in the SCCS have one level of jurisdictional hierarchy or less. Sixty-eight (37%) societies were coded with “absent or not reported” high gods with nearly a quarter (43) of the entire sample were societies lacking high gods and had no levels of jurisdictional hierarchy. In terms of the distribution of moralistic high gods in the sample, there really isn’t much of a pattern to see across jurisdictional hierarchy (see Figure 1d). The proportion of moralistic high gods present increases slightly as we increase jurisdictional levels, but drops again at the highest level of societal complexity.

Table 2 Frequencies of high god code types across levels of jurisdictional hierarchy levels from SCCS. High god code types correspond to categories detailed earlier. NA refers to “data unavailable.” Row proportions do not include NA values.

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | NA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| abs./unreported | 43 (63%) | 13 (19%) | 4 (6%) | 4 (6%) | 4 (6%) | 0 |

| inactive | 17 (36%) | 15 (32%) | 6 (13%) | 3 (6%) | 6 (13%) | 0 |

| active, nonmoral | 8 (62%) | 2 (15%) | 3 (23%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 |

| active, moral | 6 (15%) | 13 (33%) | 7 (18%) | 11 (28%) | 2 (5%) | 1 |

| NA | 8 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Many studies have exploited this variable in the EA and SCCS data sets (see Table 3). Notably, while each report offers a novel spin on the subject, all find that social complexity and/or its correlates predict moralistic high gods. Some find that subsistence predicts the presence of high gods (e.g., Simpson, Reference Simpson1984; Underhill, Reference Underhill1975), but given the concentration of “absent/not reported” values among societies with no levels of jurisdictional hierarchy (presumably foragers), this should be unsurprising.

Table 3 Resources and empirical works on the topic of morality and the gods including cross-cultural data or data from non-Western societies. Sources are as follows: EA – Ethnographic Atlas; SCCS – Standard Cross-Cultural Sample; AWC – Atlas of World Cultures; WVS – World Values Survey; DRH – Database of Religious History; ERM – Evolution of Religion and Morality Project

In one article, Snarey (Reference Snarey1996) looks beyond social complexity and mode of subsistence and assesses the relationship between water scarcity and the presence of high gods “specifically supportive of human morality.” Snarey’s hypothesis is stated as follows: “In societies in which ensuring a sufficient supply of water is difficult, the members of that society will be significantly more likely to conceive of a Supreme Deity who is concerned with, and supportive of, human morality”’ (88). While the prediction is relatively clear, the reason why “Supreme Deities” – rather than any type of morally concerned deity – matter here is not explained. So, the relationship between morality, the gods, and water scarcity is actually measured in terms of high gods. Snarey found evidence consistent with his hypothesis.

Nearly a decade later, Roes and Raymond (Reference Roes and Raymond2003) used the EA and SCCS to assess the relationship between population size, external conflict, and religion. Drawing from evolutionary biologist Richard D. Alexander’s theory of morality (1987, see below) that holds that intergroup conflict over resources boosts population size, the authors wager that one mechanism to hold such large populations together are beliefs in “moralizing gods.” Specifically, “Belief in these gods signals acceptance of the rules and...we expect more support for the rules (and thus more belief in moralising gods) in larger societies” (128). Using jurisdictional hierarchy as an index of society size, the authors indeed find a positive relationship between society size and the presence of moralizing high gods. Like Snarey, the authors make no clear justification for why moralizing high gods would matter more or less than any moralizing god. Thus, we see the recurrence of the conflation of moralizing gods with moralizing high gods. As we’ll see, this conflation has had a lasting impact on contemporary inquiry.

In summary, quantitative cross-cultural databases arose as a response to a need for tools to examine global patterns of cultural variation. This resource was specifically developed to address questions of religious variation, and it found that supernatural involvement in moral affairs was commonplace in the ethnographic world. Subsequent, more expansive databases primarily limited their focus to high gods, of which many studies had taken advantage, finding again and again a positive association between social complexity and high gods that were “specifically supportive of human morality.” Despite this narrow focus on high gods, its troubling coding scheme, at least some dubious source material, the repeated exploitation of these cross-cultural databases eclipsed generations of dedicated inquiry.

Many of the later group-level reports using cross-cultural databases came out at a time of increased interest in the evolutionary psychological foundations of religion. Rather than focusing on coarse, group-level phenomena coded from various texts, evolutionary research emphasized individual cognition and behavior in experimental and field contexts. As we’ll see, this new focus also generated new and more precise ways of thinking about and measuring the relationship between morality and the gods.

4 Cognition and Religion

4.1 Genesis of New Fields

4.1.1 Cognitive Science

While the division has existed in various guises for centuries, in the 1980s and 1990s, some sectors of the social sciences witnessed a widening gulf between those who embraced various forms of nativism (i.e., a position that emphasizes innate cognitive systems) and those who emphasized cultural learning as the ultimate explanation for human behavior.Footnote 12 Drawing from the ideas of linguist Noam Chomsky and philosopher Jerry Fodor, who pointed to innate cognitive systems to account for much of human thought and language, many social scientists began to propose a wide range of inborn cognitive mechanisms underlying other domains of culture. Much of this literature alludes to what is called the “poverty of the stimulus argument” which points to just how much isn’t taught that children nevertheless express (Chomsky, Reference Chomsky1965). For example, children don’t have to be taught what language is or that objects fall when they reach the edge of a table or that solid objects can’t pass through each other. Rather, they infer what language is, they infer that an object will fall, and they infer that solid objects will collide. Similarly, the grammar of a language emerges from deeper structures and knowledge of syntax that the child already has. According to some views, such inferences are made possible by virtue of innate cognitive systems.

Some theories specified particular features that defined these cognitive systems. Sometimes referred to as cognitive “modules,” these mental instincts were thought to be innate, handle a narrow range of inputs, and relatively automatic in their functioning (Fodor, Reference Fodor1983). Some held that the mind was only minimally modular in this sense, where modules were restricted to perhaps emotional responses, the perception of optical illusions, and some aspects of human language. Others took this view further and, in relaxing some of the criteria for what counts as a “module,” suggested that the mind is replete with modular structures that underlie a wide range of human traits (e.g., Pinker, Reference Pinker1997; Sperber, Reference Sperber1996).

4.1.2 Evolutionary psychology

Alongside a well-organized critique of the “standard social science model” – the view that most human behavior is socially learned and that the mind is effectively an all-purpose tabula rasa (i.e., blank slate) – researchers deduced the presence of a wide range of modules, including those dedicated to numbers, music, spatial cognition, and many others (Barkow, Cosmides, & Tooby, Reference Barkow, Cosmides and Tooby1995; Hirschfeld & Gelman, Reference Hirschfeld and Gelman1994). Some took this view even further and theorized that many such mechanisms evolved by way of natural selection; these modules were advantageous for our ancestors to have and this explains their universality and often context-specific functioning. Among others, these commitments were core to the nascent state of “evolutionary psychology.”

This field heavily influenced major theories of culture as well. In one approach, culture was made possible – and more likely to be a part of a group’s repertoire – because of these evolved cognitive structures. With the suggestion that evolved cognition functioned to generate intuitive inferences about our world and these mechanisms have the capacity to attract corresponding cultural information, theory increasingly minimized the significance of learning and trial-and-error in accounting for human thought and behavior.

Some drew from this increased interest in instinct to develop models of human cognition. Popular “dual-process” models made the distinction between “fast” intuitive cognition on the one hand, and “slow,” more deliberate reasoning on the other (see Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2003). Building on this, other models made the distinction between intuitive and reflective beliefs (see Sperber, Reference Sperber1996, Reference Sperber1997). Here, “beliefs” refer to any general mental idea or inference about our world that one might hold to be at least partly true. Roughly speaking, intuitive beliefs are rapidly produced and the source of or process behind producing such beliefs is not a part of one’s experience of the belief. For example, we might quickly infer that because the ground is wet and the sky is dark and cloudy, it has recently rained. We are not likely aware of the process behind that inference (e.g., logic, the structure of the syllogism of the inference, the recall of previous experience, etc.).

Intuitive beliefs are often conflated with beliefs that emerge from evolved cognition. As philosopher Dan Sperber (1996) notes: “Intuitive beliefs owe their rationality to essentially innate, hence universal, perceptual and inferential mechanisms; as a result, they do not vary dramatically, and are essentially mutually consistent or reconcilable across cultures” (91–92). Reflective beliefs, on the other hand, are more effortful and the process by which we arrive at them is very much a deliberate, conscious process. So, dividing 600 by 12.98 requires some effort and the means we arrive at our belief in the answer is the process of division. Thinking through one’s top ten favorite songs takes some reflection as the reasons why certain songs appear is a conscious part of the process. Of course, if we relax the association between “intuitive beliefs’ rationality” and “innate”, there is an intuitive-reflective continuum and one person’s reflective beliefs might be perfectly intuitive for someone else. As we’ll see, the cognitive science of religion crystallized these ideas and applied them in various ways to religious phenomena.

4.1.3 Cognitive Science of Religion

The cognitive science of religion grew directly out of evolutionary psychological thinking. While no one suggested we have a “religion” or “god” module, many argued that the cognitive foundations of religion stemmed from evolved and/or innate cognitive systems. Much of the early thinking in the cognitive science of religion endorsed the view that religious phenomena were largely by-products of our evolved minds (Atran, Reference Atran2004; Barrett, Reference Barrett2004; Boyer, Reference Boyer2007). Linguist Steven Pinker sums up this view nicely: “[humans] enjoy strawberry cheesecake, but not because we evolved a taste for it. We evolved circuits that gave us trickles of enjoyment from the sweet taste of ripe fruit, the creamy mouth feel of fats and oils from nuts and meat, and the coolness of fresh water” (Pinker, Reference Pinker1997, 524–525). In other words, humans have things like religion, music, and art because they have elements of things that had past value that we evolved to appreciate, but they remain attractive because they trigger these ancestral traits. Such things are found everywhere because of their intuitive appeal. This view treats cultural information like an epidemic; cultural things like music and literature spread like diseases because our innate cognition attracts them.

In the context of religion, these cognitive systems provide intuitive information that attracts beliefs and practices. For example, some examine whether intuitive mind-body dualism underlies beliefs in spirits (Chudek et al., Reference Chudek, McNamara, Birch, Bloom and Henrich2018). Others treat ritual as having its own “grammar” with corresponding cognitive foundations (Lawson & McCauley, Reference Lawson and McCauley1993) while others argue that the punctiliousness we so often exhibit with ritual stems from evolved “hazard precaution systems” (Liénard & Boyer, Reference Liénard and Boyer2006). Researchers have pointed to a variety of other cognitive foundations of religion, all united in suggesting that the curious elements associated with religion we find around the world emerge from the way our minds naturally work (C. White, Reference White2021).

One important set of religious beliefs comes from our ability to infer that other beings have mental states – beliefs, desires, and perceptions. While other species likely have this ability to some degree, humans’ mentalizing abilities are notably complex and nuanced (Call & Tomasello, Reference Call and Tomasello2008; D. C. Penn & Povinelli, Reference Penn and Povinelli2007). This “mindreading system” consists of a variety of sub-mechanisms ostensibly shaped by natural selection that animate the entities of our world with mental states (Baron-Cohen, Reference Baron-Cohen1997). One particularly influential idea is that among the central cognitive foundations of religion are our anthropomorphic or “mentalizing” tendencies; we are so good at detecting mental states and granting nonhumans the ability to symbolically communicate.

In this view, religious cognition is this trait in action. Building upon centuries of thought, anthropologist Stewart Guthrie (Reference Guthrie1980, Reference Guthrie1995) argued that our rapid perceptual biases toward detecting other minds accounts for our religiosity. In doing so, Guthrie grounded elements of Tylor’s theory of animism in human cognition (cf. Guthrie, Reference Guthrie2000). Guthrie added an evolutionary spin to his argument, suggesting that our ancestors – and other animals more generally – survived in the past because it was always better to detect another agent’s threat when there wasn’t one (i.e., a false positive) than it was to not detect a threat when there was one (i.e., a false negative). Individuals were more likely to survive when they erred on the side of caution. As such, it is effortless for us to find minds in the natural world. Psychologist Justin Barrett (Reference Barrett2004) pursued this idea, postulating the presence of a “hyperactive agency detection” system that detected minds with just a few of the right kinds of inputs. This device makes conveying the idea of a spirit or god – an anthropomorphic mind with unique properties – especially easy to learn and internalize. In order to believe that gods or spirits care about us, we must be able to infer that they have minds in the first place. Such inferences are fast, intuitive, and come to us naturally.

What about reflective and/or cultural beliefs? Surely religious beliefs and practices are more than what come naturally to our minds. The specifics of some beliefs are obviously cultural; from the Crucifixion to sacred garden groves, many central beliefs are culturally transmitted across the generations. Yet, some are bafflingly complicated and require generations of theologians to offer solutions. The indivisibility of the Trinity and the Problem of Evil, for example, are nontrivial problems on which theologians have expended considerable effort. Some of the founders of the cognitive science of religion point to a distinction between reflective and intuitive beliefs as useful to account for kinds of religious thought and practice, suggesting that much of religious expression stems from our intuitions (Slone, Reference Slone2007). We might have long, drawn out theological discussions about the nature of spirits and the universe, and these are deliberate reflective thoughts. However, the idea that a god knows things or the inference that a drum makes a louder sound when hit harder are both perfectly intuitive thoughts. What’s interesting about religious cognition is that sometimes our intuitions are inconsistent with our reflections; our own minds often get in the way of what we’re supposed to believe about the minds of gods.

One set of experiments (Barrett & Keil, Reference Barrett and Keil1996) showed that even though individuals claim that the Christian god knows and perceives everything, after reading a passage that describes some event, participants readily limit his ability as though he were a human. For example, participants read one scenario where God is admiring a colorful rock, but then a stampede runs by and covers it with dust. When recalling the story, individuals – who claim God perceives everything – suggest that God’s vision of the rock was obscured by the dust. What this inconsistency suggests is that people are using their intuitive beliefs about people – beings with limited perceptual abilities – to quickly make sense of a scenario even though they claim that the agent involved is omniscient; an all-knowing entity should still be able to see and appreciate the stone after it was covered with dust. Had individuals been using their more abstract theological statements when perceiving the story, they would have said as much. As we’ll see, this interplay between explicit religious beliefs and how individuals intuitively think in real-time plays a role in making sense of the relationship between morality and the gods. In order to appreciate these developments, we need to first briefly review the evolutionary psychology of morality.

4.2 Cognitive Foundations of Religion and Morality

4.2.1 Evolutionary Psychology of Morality

As we’ve already seen hints of, the subject of morality has had a long and diverse history (Malle & Robbins, Reference Malle and Robbins2025). As in any other field striving to understand elusive, multifaceted theoretical constructs, various researchers tend to emphasize different things. In keeping with philosopher Immanuel Kant’s (Reference Kant and Gregor1997 [1785]) categorical imperative, some appeal to universal applicability; morality involves prescriptive behaviors that are applicable to everyone at all times (Caton, Reference Caton1963). Such views attend to the scope of moral relevance. Others focus on the content of what counts as “moral.” For example, developmental psychologist Eliot Turiel (Reference Turiel1983, Reference Turiel, Killen and Smetana2006) famously considers morality as things concerning “justice, rights, and welfare.” However, the content and scope of what counts as moral is known to vary cross-culturally, and groups often lack abstract notions like “justice” and “rights,” or don’t specify or limit whom and to what situations moral prescriptions apply (Fessler et al., Reference Fessler, Barrett and Kanovsky2015; Schwartz, Reference Schwartz2007; Shweder et al., Reference Shweder, Much, Mahapatra, Park, Brandt and Rozin1997). Indeed, the difficulty in precisely delimiting what constitutes morality is only exacerbated by Western-centric approaches to the topic. As cultural and evolutionary anthropologist Christopher Boehm (Reference Boehm1980) mused, “when the subject is morality, possibilities for ethnocentric, personal, and theoretical biases of the ethnographer to distort indigenous ‘psychological realities’ are maximal” (3). However, there does appear to be an emerging consensus in the field.

Part of that consensus lies in the relationship between our mentalizing abilities and their relevance to morality. Many have examined the strong psychological link between mind perception and moral cognition (K. Gray, Young, & Waytz Reference Gray, Young and Waytz2012; Imuta et al. Reference Imuta, Henry, Slaughter, Selcuk and Ruffman2016; Young & Phillips Reference Young and Phillips2011). In particular, perspective-taking is essential to engage in “good” behavior and avoid “bad” behavior; this kind of empathizing is necessary for strong, stable relationships. So, when we use our mentalizing abilities, we engage our moral sensibilities by default.