Communities around the world strive to preserve their homes, landscapes, and cultural and historic sites from externally driven change. For nearly a century anthropologists and preservationists have sought ways to limit conflict, boost cooperation, and balance proposals for economic and community development with mandates to safeguard special places and the senses of identity, beauty, belonging, and security they provide (Goodenough Reference Goodenough1963; Grillo Reference Grillo, Desai and Potter2002). Despite advances in social and environmental impact management and promulgations of international and national policies—conventions, statutes, regulations, and official rules and guidance—that promote the preservation of historic and cultural sites and landscapes, consequential conflicts over places persist (Aronsson and Price Reference Aronsson and Price2024; Spears et al. Reference Spears, Dongoske, Seowtewa, Hopkins and Ferguson2024).

This article examines cultural landscape studies as widely recognized yet underused tools for assessing the importance of places that are threatened by region-scale change and are not readily identified or assessed by archaeologists or other specialists who lack local knowledge. We conducted an expert opinion survey and analyzed available cultural landscape studies to identify ways to improve the processes, products, and applications of cultural landscape studies in the context of proposals for change. The catalyst for our research is a thus far unfulfilled obligation to conduct a cultural landscape study as part of the impact assessment process for an interstate powerline. Pattern Energy, an applicant to the US Bureau of Land Management (BLM), agreed to complete a cultural landscape study before constructing the SunZia transmission line from central New Mexico to central Arizona. To encourage Pattern Energy and the BLM to complete the required study in accord with professional standards, we sought to understand the attributes of an effective cultural landscape study and how such a study could have improved region-scale understanding of SunZia impacts and resulted in more effective place protections.

Section 106 Process and Evolution

The National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 (NHPA) is the principal US policy for important places that may be affected by federal agencies’ proposed actions (“undertakings”). The NHPA aspires to “foster conditions under which our modern society and our historic property can exist in productive harmony and fulfill the social, economic, and other requirements of present and future generations” (54 U.S.C. § 300101). Yet in practice, the NHPA is procedural: it mandates due consideration, not place preservation. Federal agencies must “stop, look, and listen” to find and assess the effects of their undertakings on historic properties—that is, sites, districts, buildings, structures, or objects—listed in or eligible for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places (often known as the Section 106 process; 36 Code of Federal Regulations Part 800; 54 U.S.C § 306108). In addition, NHPA Section 110 requires federal agencies to establish preservation programs, integrate historic preservation into agency activities, designate federal preservation officers to coordinate NHPA responsibilities, and build historic property inventories for lands under agency control (54 U.S.C § 306101–306114; 63 F.R. 20499–20508).

Federal agency compliance with Section 106 of the NHPA drives about 100,000 undertaking reviews annually (National Park Service 2022). Undertakings range from projects with footprints smaller than one acre to regionally transformative proposals like highways and pipelines. Reviews are carried out primarily by federal agency staff, State and Tribal Historic Preservation Officers (S/THPOs), the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, and professional environmental contractors (36 CFR 800.2). Included in these reviews are archaeologists, historians, architects, landscape architects, cultural anthropologists, and planners (48 Fed. Reg. 44738–44739). Once initiated, Section 106 reviews have three key elements: identification of historic properties, assessment of adverse effects, and resolution of adverse effects (Alexander Reference Alexander2012:6–13).

Section 106 regulations require reviews to be commensurate with “the scale and nature of an undertaking” (36 CFR 800.16(d)). The regulations use the word “appropriate” 42 times, primarily to encourage agencies and applicants to “match” the review process to the undertaking’s context and complexity, to potential effects’ prior uses and users, and to the number, integrity, and significance of the historic properties potentially affected. Regardless of scale or complexity, Section 106 reviews require public engagement and consultations with Tribes, S/THPOs, and interest groups (Alexander Reference Alexander2012:6–7).

Section 106 reviews have changed in accord with public policy preferences for inclusivity in government decision-making. Through most of the 1980s, federal agencies tended to simplify Section 106 mandates by dispatching architects and archaeologists to “survey” lands slated for alteration by undertakings (“area of potential effects,” or APE) and to document discrete buildings, structures, objects, districts, and sites and evaluate these potential historic properties in terms of dominant-society aesthetics, histories, and sciences (McManamon Reference McManamon and Ellis2000). Advocacy by Tribes and other place-centered communities, coupled with shifts in international policy, led to calls for Section 106 reviews to consider greater ranges of historic properties, adverse effects, APEs, and options for avoiding and reducing undertakings’ adverse effects on historic properties (Hogg et al. Reference Hogg, Welch and Ferris2017; Welch Reference Welch1997).

In response, in 1992 the US Congress amended the NHPA to require that historic properties of religious and cultural significance to Tribes and other traditional communities be considered in the Section 106 process and may be listed in the US National Register of Historic Places (Section 101(d)(6)(A); Ferguson Reference Ferguson1996). The amendments also require consultation with “any Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization that attaches religious or cultural significance” to historic properties associated with an undertaking (54 U.S.C § 302706). The distinctive definition of consultation in the Section 106 regulations affirms consensus as the objective: “Consultation means the process of seeking, discussing, and considering the views of other participants, and, where feasible, seeking agreement with them” (36 CFR 800.16(f)). Section 106 consultations are to be “appropriate to the scale of the undertaking and the scope of Federal involvement” (36 CFR 800.2(a)(4); see also 36 CFR 800.8(c)(1)(ii)).

During the same period, and in response to a lack of consideration of large-scale historic properties significant to living communities, the US government issued National Register Bulletin 38 to guide the identification and evaluation of traditional cultural properties, also known as traditional cultural places (TCPs; King Reference King2003). TCPs are historic properties eligible for inclusion in the National Register because of their significance to a living community and their associations with cultural practices and beliefs rooted in that community’s history and important in maintaining the community's cultural identity (National Park Service 2023; Parker and King Reference Parker and King1998). These developments—in sync with 1992 recognition by the World Heritage Convention of cultural landscapes as representations of the “combined works of nature and of man”—elevated the importance of the identification and assessment of traditional cultural landscapes and other landscape-scale historic properties during the Section 106 process (Ball et al. Reference Ball, Clayburn, Cordero, Edwards, Grussing, Ledford and McConnell2017; Dongoske and Damp Reference Dongoske and Damp2007; Evans et al. Reference Evans, Roberts and Nelson2001:54; Fowler Reference Fowler2003; Suagee and Bungart Reference Suagee and Bungart2013; Welch et al. Reference Welch, Riley and Nixon2009).

The broadening of historic property identification and assessment efforts in the Section 106 process, in conjunction with the 1992 regulations and the initial publication of National Register Bulletin 38, gave rise to investigations designed to complement the archaeological and architectural survey methods that had previously dominated Section 106 reviews. Federal agencies sponsored or required ethnographic and ethnohistorical studies (Jackson and Burns Reference Jackson and Burns2006), traditional use studies (Deur et al. Reference Deur, Evanoff and Hebert2018), and cultural landscape studies as tools for meeting Section 106 proportionality and consultation mandates.

Only a small percentage of undertakings entail adverse effects to historic properties, and most Section 106 reviews proceed smoothly (Alexander Reference Alexander2012:3). Where conflicts arise, public and consulting party claims of inadequate consultation and proportionality are common drivers for administrative, political, and legal campaigns to preserve places (Advisory Council on Historic Preservation 2001). Such claims are not uncommon in Section 106 reviews for undertakings that involve landscape-scale historic properties or cultural landscapes (see Welch et al. Reference Welch, Riley and Nixon2009). Despite decades of advocacy by Tribes and others for adequate consideration of TCPs and cultural landscapes in Section 106 reviews, these types of properties continue to be under-considered and overly affected by major undertakings (Advisory Council on Historic Preservation 2012a).

SunZia Undertaking Consultation and Proportionality

The Section 106 review process for the SunZia Southwest Transmission Project offers insights into issues of consultation, proportionality, and cultural landscapes. The 885 km transmission line, which was initially proposed in 2009 and began construction in 2023, intends to transport up to 4,500 megawatts of wind, solar, and fossil fuel energy produced in New Mexico to California. Although the BLM is the lead federal agency for the project, the SunZia route traverses the territories of more than a dozen Tribes and required approvals from multiple federal and state agencies. Many of these parties participated in the development of the 2014 programmatic agreement to facilitate the Section 106 review. The project entails adverse effects to more than 40 identified historic properties and to an undetermined number of TCPs (Bureau of Land Management 2013, 2023).

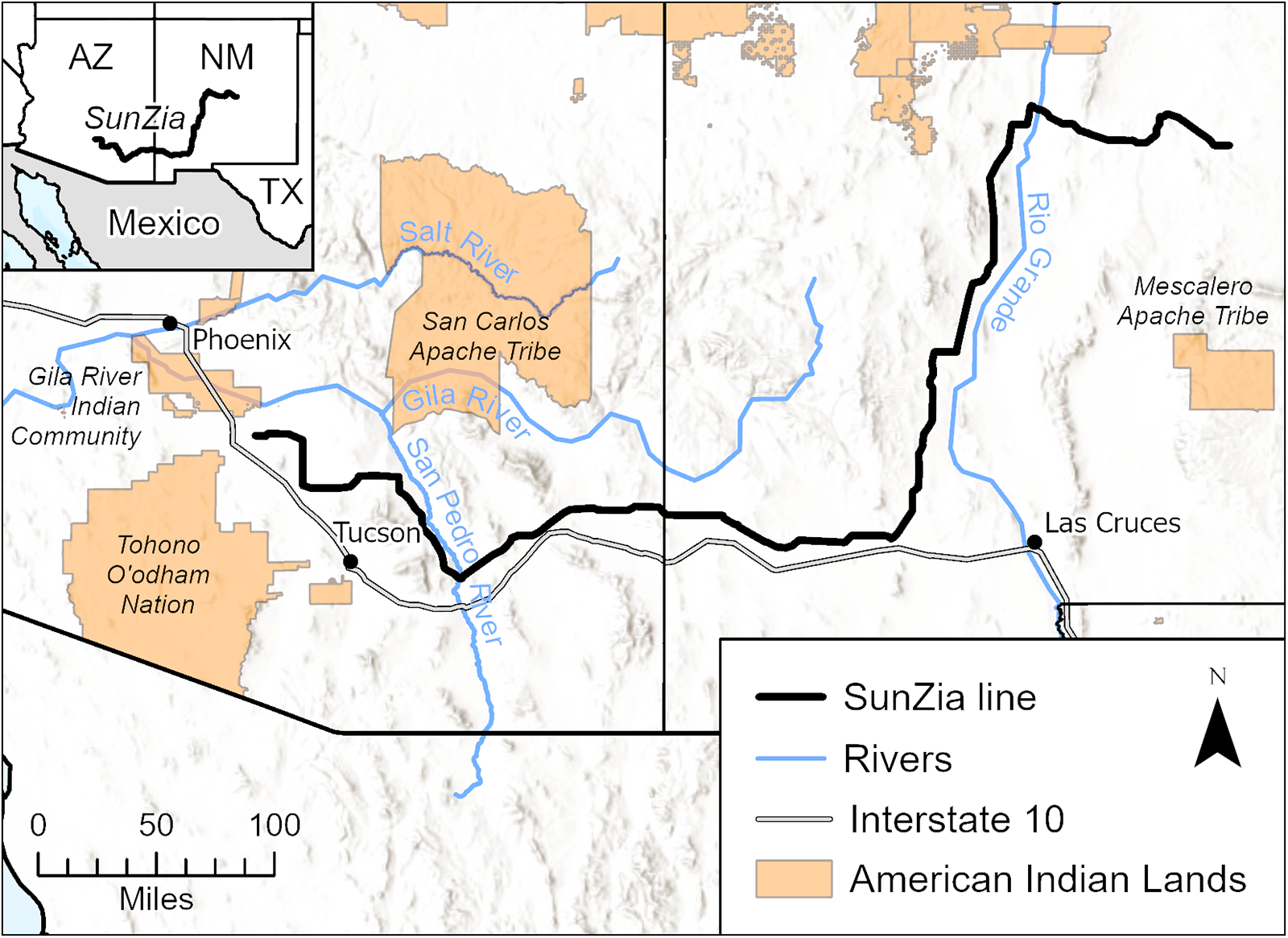

Conflict over this complex, landscape-scale undertaking has centered on Tribes’ concerns about SunZia’s adverse effects on Arizona’s San Pedro Valley, where the transmission line departs from existing industrial corridors and traverses this previously unfragmented and historically significant valley for 80 km (Figure 1). Welch et alia (Reference Welch, Spears, O'Meara, Portman and Binford-Walsh2024) show SunZia’s Section 106 consultations in relation to the San Pedro Valley and is the source for the quotations and communications referenced in the following section.

Figure 1. SunZia transmission line route and Tribal lands mentioned in the text.

The San Pedro Valley Cultural Landscape

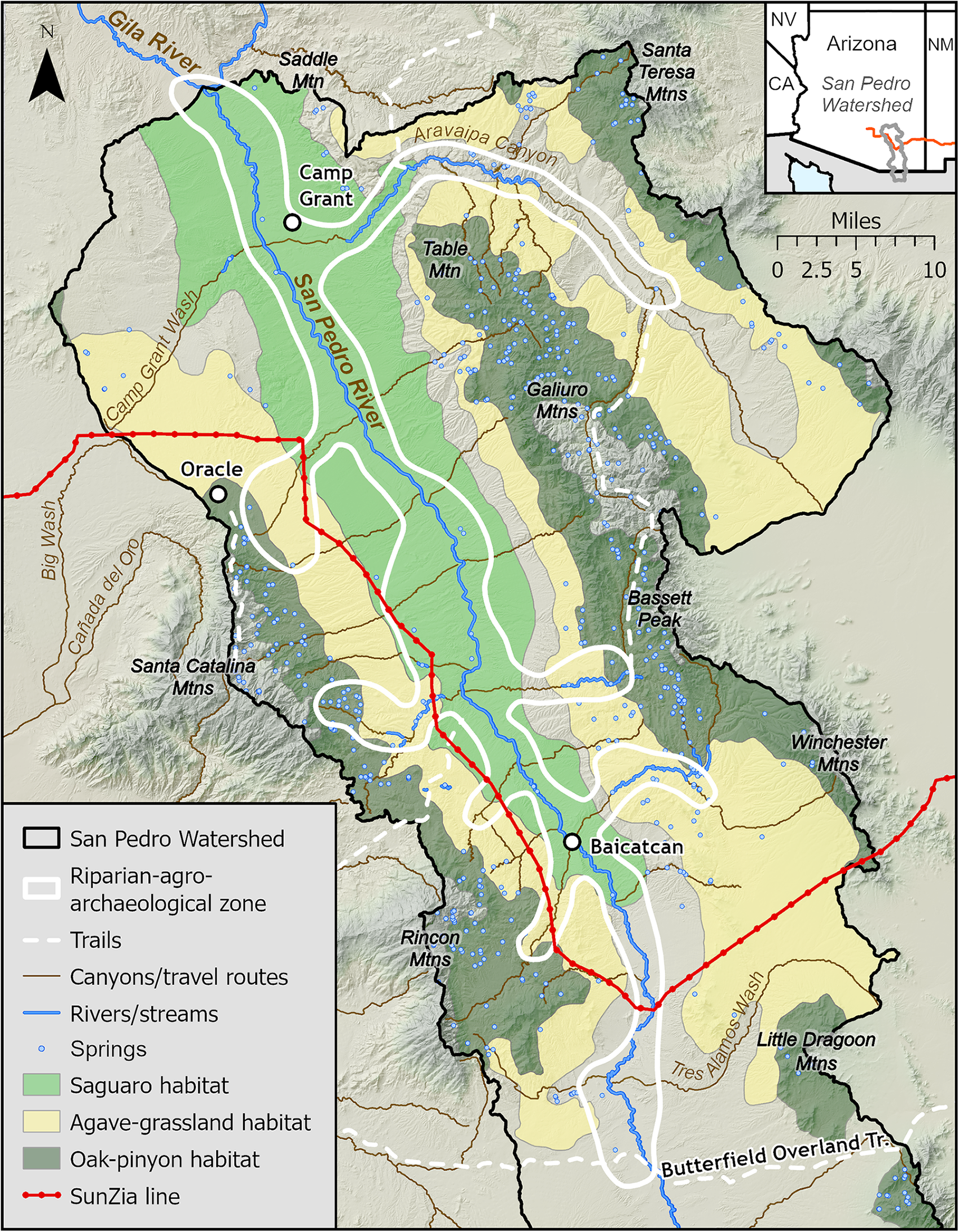

The San Pedro River is among the last free-flowing perennial rivers in the Southwest (Stromberg and Tellman Reference Stromberg and Tellman2009). Figure 2 depicts the cultural landscape of the lower San Pedro Valley, centered on about 210 km of perennial streams and 700 springs and seeps (Ledbetter et al. Reference Ledbetter, Stevens and Brandt2024; Turner Reference Turner2010). Within the riparian corridor and adjacent canyons are nearly 500 documented archaeological sites, hundreds of acres of irrigable farmlands, and hundreds of miles of Indigenous and historic period travel routes, including canyon corridors (Clark and Lyons Reference Clark and Lyons2012; Sayre Reference Sayre2011). High-quality upland habitats for saguaro, agave, oak, and pinyon pine provide extensive food-gathering areas (Griffith et al. Reference Griffith, Omernik, Burch Johnson and Turner2014).

Figure 2. Elements of the Lower San Pedro Valley cultural landscape.

The valley persists as a place of cultural significance in Zuni, Hopi, O’odham, and Apache cultural traditions (Ferguson and Colwell Reference Ferguson and Colwell-Chanthaphonh2006). Place names affirm Indigenous peoples’ deep and ongoing connections to the valley’s geography, flora, and history (Colwell-Chanthaphonh Reference Colwell-Chanthaphonh2015:31–32; Ferguson and Colwell Reference Ferguson and Colwell-Chanthaphonh2006:219–220; Kino Reference Kino and H1919:123; Record Reference Record2008:20–21, 58–59, 86). Places with Apache names include Tł'ohk'aa Tú Bił Nlịị (“Cane Water with It Flowing”–Aravaipa Creek), Túdotł'ish Sikan (“Blue Water Pool”–Camp Grant), Tse Da'iskán (“Rock with Flat Top”–Table Mountain), Túdiłhił Bebishé (“Coffee Pot”–Saddle Mountain), and Dził Nazạạyú (“Mountain Sits Here and There”–Bassett Peak; Colwell-Chanthaphonh Reference Colwell-Chanthaphonh2015:31–32; Ferguson and Colwell Reference Ferguson and Colwell-Chanthaphonh2006:219–220; Record Reference Record2008:20–21, 58–59). Named O’odham places include Babad Do'ag (“Frog Mountain”–Santa Catalina Mountains) and Baicatcan, a Sobaipuri-O’odham village (Ferguson and Colwell Reference Ferguson and Colwell-Chanthaphonh2006:86; Kino Reference Kino and H1919:123). The San Pedro River’s first Anglo name, “Beaver River,” highlights the interest in commodity extraction of most early American visitors (Pattie Reference Pattie, Flint and Wood1831:63; Sayre Reference Sayre2011).

SunZia Adversely Affects the San Pedro Valley

Apache, O’odham, and Spanish place names and associated stories are one of many layers of information available to understand the cultural and ecological geographies affected by SunZia. The BLM, the lead federal agency for the project, is responsible for finding such information and listening to knowledgeable and concerned people before making decisions. The BLM began consultation with about a dozen Tribes and various other parties about SunZia “early in the undertaking's planning, so that a broad range of alternatives may be considered” (36 CFR 800.1(c)). After Tribes and other consulting parties expressed concerns with any SunZia construction in the San Pedro Valley, the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Center for Desert Archaeology advised the BLM on November 25, 2009, to co-locate SunZia within existing industrial corridors and to “avoid the unique, intact and regionally significant natural and cultural resources and landscapes in the … San Pedro River Valley.”

Multiple Tribes provided clear, consistent, and timely feedback and critiques of the proposed undertaking, including advice to the BLM to restrict most of the right-of-way to existing industrial corridors and to conduct an ethnographic study. Ak Chin Indian Community officials requested a designated BLM Tribal Liaison for the project (July 21, 2009). The Mescalero Apache Tribe requested a BLM contract to identify TCPs (October 16, 2009). In no fewer than 21 separate oral and written communications, Tohono O’odham Nation officials advised the BLM of the need for ethnographic or cultural landscape studies to identify other-than-archaeological historic properties and other-than-scientific values (Welch et al. Reference Welch, Spears, O'Meara, Portman and Binford-Walsh2024:Table S.1).

Tribes readily understood that SunZia threatened their homelands and ancestral places and made clear that the identification and assessment efforts that the BLM and the SunZia applicant proposed were inadequate. Barnaby Lewis, the Gila River Indian Community THPO, told BLM officials, “The project would be very intrusive to the tribe’s cultural landscape … ‘don’t build it.’ Archaeological sites are not just physical remains of the past, but they also entail ancestral and religious values. The tribe objects to the diminishment of qualities of the cultural landscape and the natural world” (October 17, 2012). Terry Rambler, the San Carlos Apache Tribe chairman, expressed the “Tribe's concerns regarding the BLM's and SunZia's sensitivity regarding Apache cultural sites, sacred areas, plant gathering areas and identification of remains is only exacerbated by the complete lack of sensitivity in the description of cultural resources” (August 22, 2012).

The BLM did not act in accord with the Tribes’ and other consulting parties’ advice and requests, discounting Section 106 requirements for proportionality and for “seeking agreement.” Instead of requiring an ethnographic study, a cultural landscape study, or other investigation to understand SunZia impacts in their cultural, historical, and geographic contexts, the BLM endorsed the archaeology-only historic property identification and assessment methods that Pattern Energy, the undertaking applicant, commissioned for SunZia’s vast area of potential effects. The BLM’s historic property identification efforts continue to largely exclude the “background research, consultation, oral history interviews” informed by “past planning, research and studies,” called for by NHPA regulations (36 CFR § 800.4(b)(1)). As of late 2024, the BLM also continued to disregard peer-reviewed studies that establish the San Pedro Valley as a cultural landscape, as a home to diverse Indigenous Peoples for more than 12,000 years, and as an irreplaceable source of distinctive benefits to diverse living human communities (Bagstad et al. Reference Bagstad, Semmens, Winthrop, Jaworski and Larson2012; Ferguson and Colwell Reference Ferguson and Colwell-Chanthaphonh2006; Sayre Reference Sayre2011).

SunZia’s Section 106 review process has yet to match the scale and complexity of this federal undertaking. In contrast, the state permit for SunZia specifically requires investigation of its cultural-geographical contexts within Arizona. The Certificate of Environmental Compatibility (CEC) issued by the Arizona Corporation Commission on November 24, 2015, affirmed that the “Class III cultural resource survey and cultural landscape study shall be conducted to fully evaluate the impacts of the Project on the cultural landscape prior to the commencement of construction” (Welch et al. Reference Welch, Spears, O'Meara, Portman and Binford-Walsh2024:Table S.1). This binding condition separates two essential requirements: the site-focused archaeological inventory (largely completed in 2024) and the still-needed cultural landscape study.

The BLM did not consult with Tribes and other parties about when or how to complete the required cultural landscape study before authorizing SunZia construction. The BLM also disregarded confirmation from the independent “watchdog” agency for Section 106, the US Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, that the BLM, not the Tribes, is responsible for TCP identification and assessment (November 13, 2023). The BLM published the second SunZia environmental impact statement before completion of the archaeology-only historic property identification and assessment process. That impact statement claims that “no TCPs or sacred sites were identified within the analysis area” while also acknowledging that no effort was made to identify TCPs (Bureau of Land Management 2023:3–122). The BLM selected the San Pedro Valley to host SunZia and authorized SunZia construction before commencing TCP identification efforts or completing the archaeological site inventory surveys.

BLM inattention to Section 106 mandates for scale-appropriate historic property consideration and for TCP identification jammed the Tribes into a corner. In early 2024, the Tohono O’odham Nation, San Carlos Apache Tribe, Archaeology Southwest (formerly the Center for Desert Archaeology), and the Center for Biological Diversity filed a lawsuit in US District Court against the US Department of the Interior seeking to halt SunZia construction and require Section 106 compliance (Tohono O'odham Nation v. United States Dep't of Interior, No. CV-24-00034-TUC-JGZ, 2024). Later, the same parties, joined by San Pedro resident Peter Else, formalized a complaint with the Arizona Corporation Commission, pointing out that Pattern Energy had yet to comply with the 2015 CEC or to complete the cultural landscape study (Tohono O'odham Nation v. SunZia Transmission LLC, No. LO-00000YY-24-0042, 2024).

As of late 2024, Pattern Energy has completed virtually all ground-clearing construction activities but has yet to initiate a cultural landscape study, a TCP identification effort, or any other effort for historic property identification and assessment commensurate with the scale and complexity of the SunZia undertaking. The BLM and Pattern Energy are choosing to mitigate the adverse effects to identified historic properties almost exclusively through destructive excavation, including archaeological testing and data recovery within areas that Tribes have repeatedly identified as TCPs.

The lawsuits filed to force the BLM and Pattern Energy to match their Section 106 efforts to the scale and complexity of the project and to enforce the CEC have yet to overcome arguments by federal and corporate lawyers that the lawsuits should have been filed prior to 2020 (Bryan Reference Bryan2024). The courts’ dicta thus far is that the Tribes should have sued earlier, apparently in anticipation that the BLM and Pattern Energy would refuse to conduct the agreed-on cultural landscape study and to make good-faith efforts to identify TCPs. The following sections present the results of our survey of veteran Section 106 practitioners and our review of available cultural landscape studies.

Methods for Understanding Cultural Landscape Studies in Section 106 Reviews

To mitigate the ongoing conflict over SunZia, avoid future similar conflicts, and improve cultural landscape identification and assessment, we set out to identify emerging professional preferences and standards for applying cultural landscape studies in Section 106 reviews. We identified six central questions about what cultural landscape studies are and when, where, how, and to what ends they are to be completed in the Section 106 process:

1. How do historic preservation professionals conceptualize and define cultural landscapes and cultural landscape studies?

2. What conditions prompt cultural landscape studies in Section 106 processes, and what roles do these studies play in Section 106 reviews?

3. How prevalent are cultural landscape studies in Section 106 reviews, and what other types of studies are used to investigate complex, landscape-scale undertakings?

4. What guidance do historic preservation professionals follow in investigating cultural landscapes in Section 106 reviews?

5. What methods and lines of evidence are used in cultural landscape studies in Section 106 reviews?

6. What are the primary outcomes from investigating cultural landscapes as part of Section 106 processes? What should they be?

We addressed these questions through two data collection and analysis efforts. First, we conducted an online survey of historic preservation professionals to gather their perceptions on current practices and to identify recommended future practices for cultural landscape study methods and applications. Second, we analyzed the content of existing cultural landscape studies to document their methods and lines of evidence and how they are used in Section 106 reviews.

Expert Opinion Survey of Section 106 Practitioners

We developed our expert opinion survey using QualtricsXM to assess how historic preservation professionals think about, conduct, and apply cultural landscape studies in the Section 106 process. The survey questions solicited background information about the respondents, their experience with cultural landscapes in the context of Section 106 reviews, and ways to improve cultural landscape studies in that context.

We prepared an initial survey to address our six questions and “piloted” the survey with 10 historic preservation professionals, soliciting their responses and feedback. We used the results of this pilot study to revise the questions and then re-piloted the survey with 25 professionals and used their feedback to further refine the questionnaire. The final survey posed 16 open- and close-ended questions (Welch et al. Reference Welch, Spears, O'Meara, Portman and Binford-Walsh2024:Table S.2). We disseminated it to potential participants, including through Archaeology Southwest, the National Association of Tribal Historic Preservation Officers, the National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officers, and the American Cultural Resources Association, New Mexico Archaeological Council, and Arizona Archaeological Council listservs. Participation in the survey was voluntary. It was also anonymous, except in the few cases in which respondents elected to self-identify.

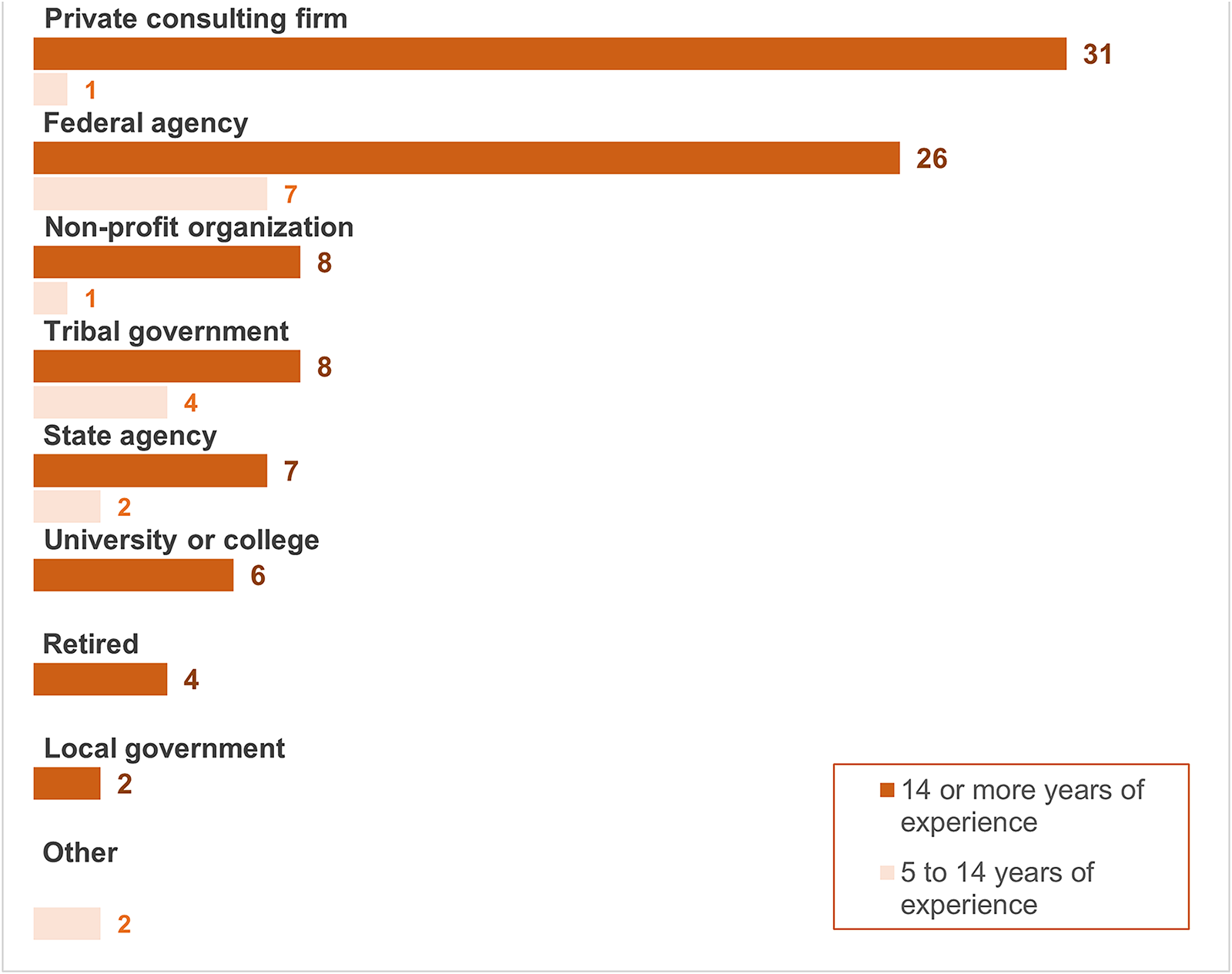

The survey was open for three weeks and netted 179 responses. We excluded from analysis 70 responses that were incomplete or provided by respondents who had less than five years of experience in Section 106 practice. We analyzed the 109 retained responses using IBM SPSS statistical software (Welch et al. Reference Welch, Spears, O'Meara, Portman and Binford-Walsh2024). The respondents represent a cross-section of the historic preservation field with a collective 1,500 years of experience in Section 106 reviews. Employers ranged from government agencies and private consulting firms to non-profit organizations and universities (Figure 3). We were unable to assess the presence of confirmation bias stemming from the likelihood that those practitioners with prior interests in cultural landscapes may have been more inclined to complete the survey.

Figure 3. Survey respondents by employer type and years of experience.

Content Analysis of Cultural Landscape Studies

We also reviewed existing cultural landscape studies to understand their rationales, methods, products, and impacts of completed investigations. We limited the sample to those prepared for the purpose of Section 106 compliance and included cultural landscape studies that we had prior knowledge of, that surfaced in internet searches, and that were identified by survey respondents. We focused on publicly available reports, except where project proponents granted permission to use unpublished works. We found no reliable way to learn about unpublished studies and quickly determined that few denominated “cultural landscape studies” done in conjunction with Section 106 reviews were publicly available (e.g., King Reference King2004; Nesper et al. Reference Nesper, Willow and King2002). In response, we expanded our definition of “cultural landscape study” to include anthropologically grounded landscape-scale study types, such as expansive archaeological studies (e.g., Elson Reference Elson2011), ethnographic studies (e.g., Bean et al. Reference Bean, Dobyns, Kay Martin, Stoffle, Brakke Vane and White1978), traditional cultural property studies (e.g., Anyon Reference Anyon2001), and National Register nominations (e.g., Nez Reference Nez2016). Welch et alia (Reference Welch, Spears, O'Meara, Portman and Binford-Walsh2024) display a full list of the included studies and the results of our analysis.

We excluded studies tied to the National Park Service (NPS) Cultural Landscape Program (e.g., Torkelson et al. Reference Torkelson, Mason and Nasta2023; WLA Studio Reference Studio2023, Reference Studio2024). Although many of these excluded studies address NHPA Section 106 and 110 compliance, most address protected areas rather than lands subject to industrial alteration. Most also use Western landscape architecture or narrowly archaeological information, rather than methods to assess a broader spectrum of places, including TCPs and associated values. As one survey respondent wrote, “NPS cultural landscape theory and action comes out of the Landscape Architecture world and does not work well with the non-built environment.”

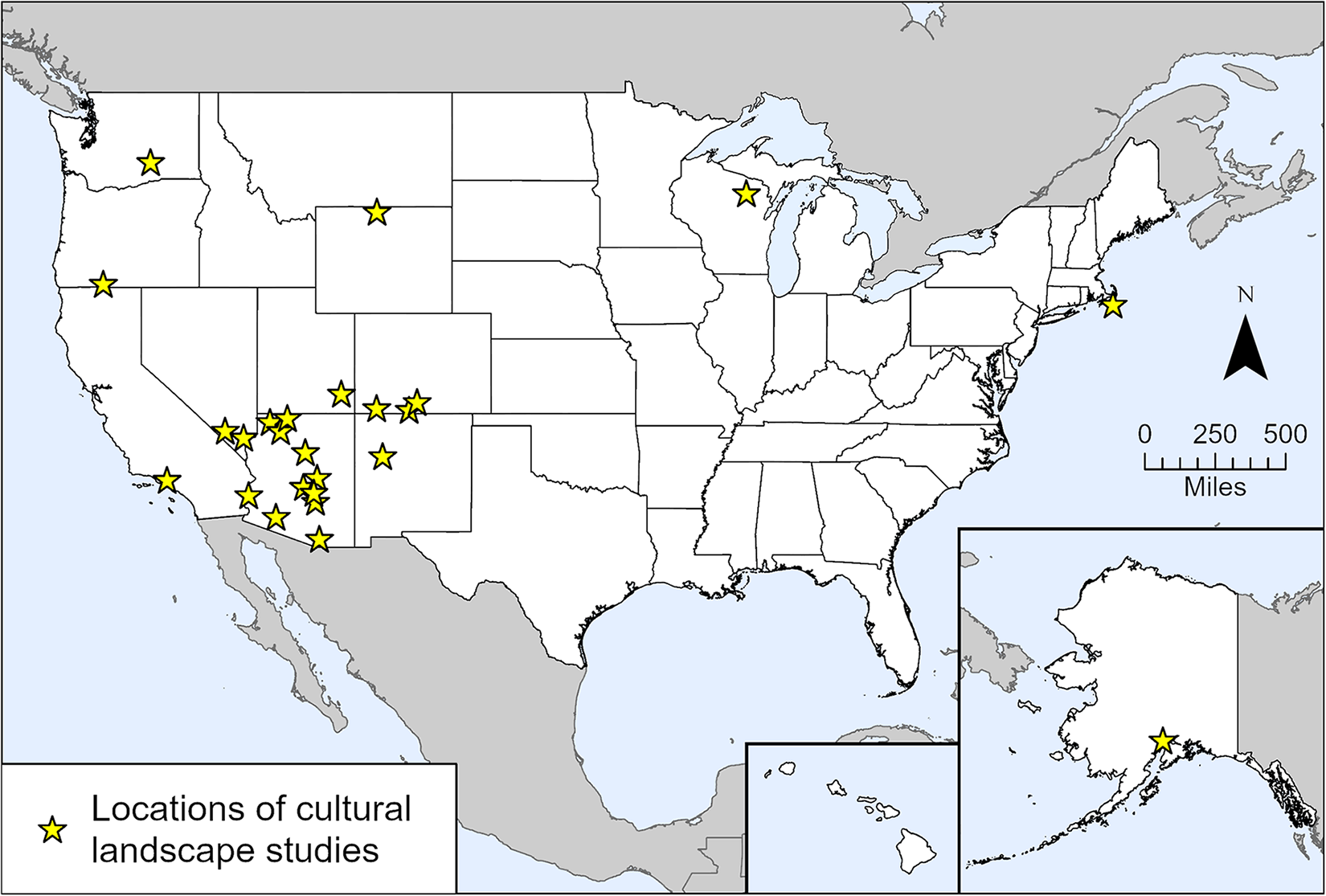

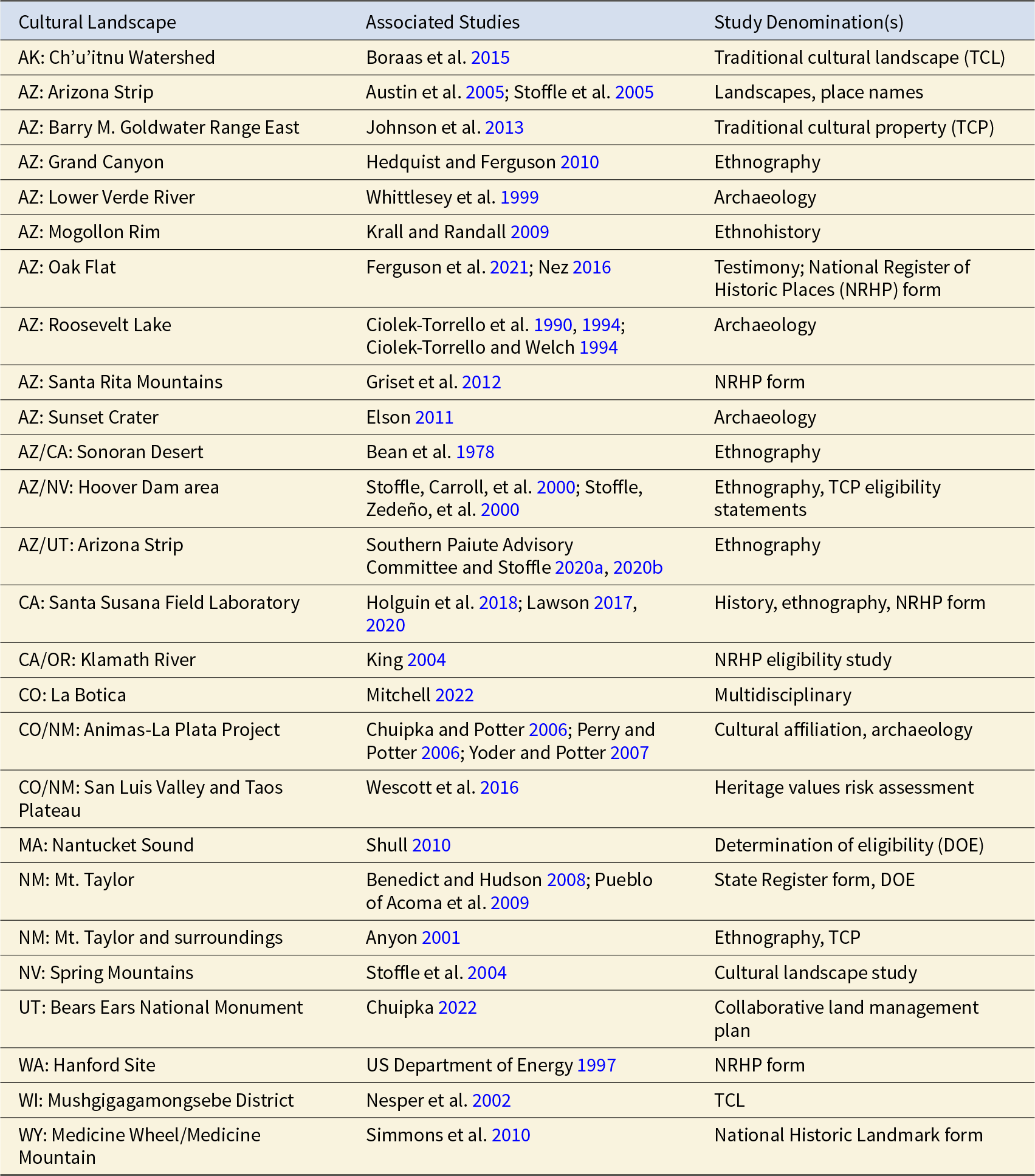

Based on these criteria, we selected and analyzed 37 landscape-scale studies pertaining to 26 federal undertakings within 12 US states (Table 1; Figure 4). Our sample encompasses varied theoretical and methodological approaches, geographies, and community engagements. Because we found no means to identify with confidence every previous landscape-scale study driven by Section 106, we have no basis for assessing the sample’s representativeness. Almost half the studies occurred at least partially in Arizona.

Figure 4. Locations of analyzed cultural landscape studies.

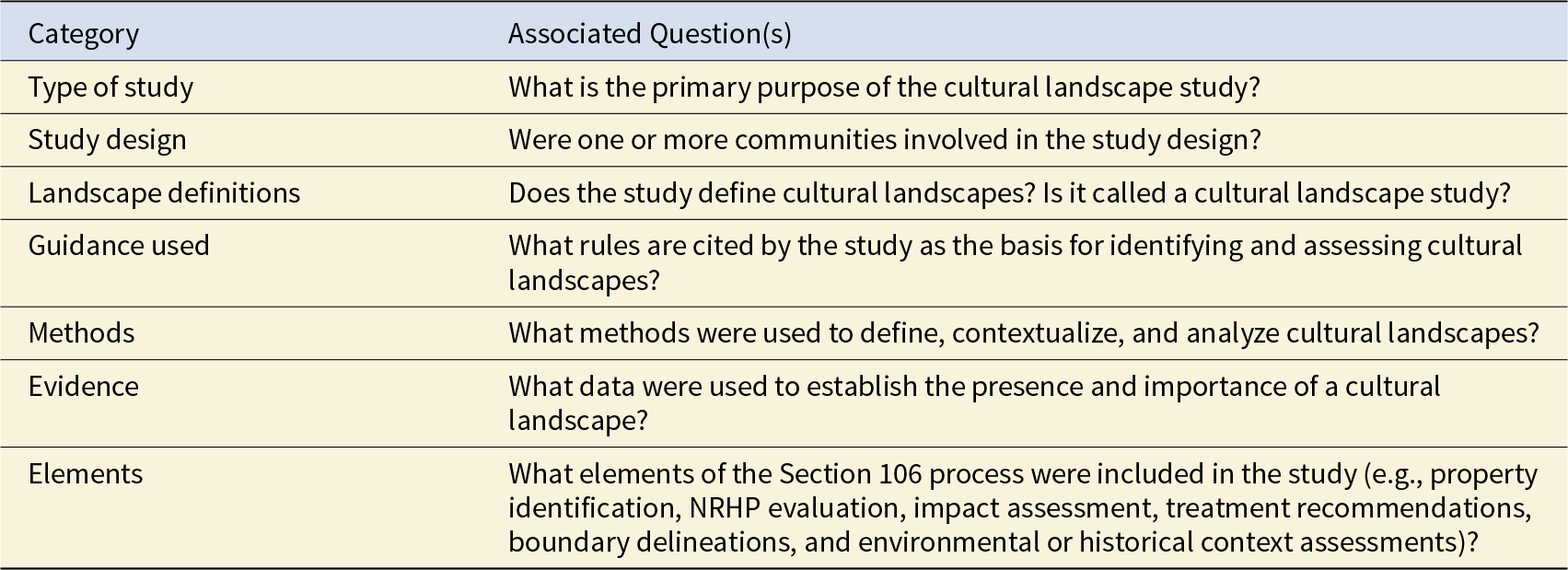

We analyzed each selected study to understand why and how it was conducted and how its results were used. We coded each study using 44 presence-absence attributes representing seven major categories (Table 2). We combined the tabulation of multivolume studies and studies driven by the same undertaking.

Table 1. Cultural Landscape Studies Included in This Analysis.

Note: AK (Alaska), AZ (Arizona), CA (California), MA (Massachussetts), NM (New Mexico), NV (Nevada), OR (Oregon), UT (Utah), WA (Washington), WI (Wisconsin), WY (Wyoming)

Table 2. Categories of Attributes Used to Analyze Cultural Landscape Studies.

Results of Survey and Content Analyses

The results of the expert opinion survey and cultural landscape study analysis shed light on our research questions: What are cultural landscape studies? What circumstances warrant their application? What study methods are appropriate? What purposes do such studies serve and what contributions do they make to Section 106 reviews? The following sections highlight convergences and divergences between preferences expressed in the survey responses and the actual practices and products of cultural landscape studies. The final section defines emerging standards and essential attributes for cultural landscape studies employed in Section 106 reviews.

Defining Cultural Landscapes

To understand how practicing professionals conceptualize cultural landscapes, we analyzed the definitions in available cultural landscape studies and asked survey respondents to consider the National Park Service’s (2024) definition of a cultural landscape: “a geographic area that includes cultural and natural resources associated with an historic event, activity, person, or group of people.” Sixty-four percent of our 109 survey respondents said they were satisfied or very satisfied with this definition. Five of the 13 available studies that included a cultural landscape definition used the NPS definition.

Survey respondents also provided 77 recommendations for how the NPS definition of cultural landscapes could be expanded or improved. Respondents indicated that cultural landscape definitions should emphasize relational aspects of cultural landscapes that connect communities to places (seven responses), encompass tangible and intangible landscape elements (seven responses), acknowledge traditional ecological knowledge (six responses), and recognize the historical depth and multicultural dimensions of many landscapes (nine responses).

Considering Cultural Landscapes in Section 106 Reviews

Our review of available studies focused on how past projects had identified, accessed, and treated cultural landscapes within the Section 106 process. The results indicate how cultural landscapes have been identified and considered in relationship to federal undertakings and how that does or does not align with the preferences of survey respondents. Several respondents noted inadequacies in the Section 106 process. One wrote, “Section 106 is imperfect … not well suited to being responsive to indigenous communities' values and ways of knowing in regard to heritage resources including cultural landscapes.” Another respondent suggested “shifting focus from the National Historic Preservation Act to the National Environmental Policy Act where agencies must consider all aspects of the human environment and their linkages.”

Regardless of whether Section 106 is an ideal venue for cultural landscape studies, 87% of survey respondents indicated that cultural landscapes should be considered to be part of the Section 106 process in all cases, and 94% said that cultural landscape studies should be conducted part of Section 106 reviews for large-scale undertakings. Yet, only 72% percent of respondents had actually seen cultural landscape studies conducted as part of a Section 106 review, and our sample includes only six denominated cultural landscape studies. Thus, despite practitioner preferences, cultural landscape studies have yet to be systematically implemented as part of Section 106 processes, even for complex, region-scale undertakings.

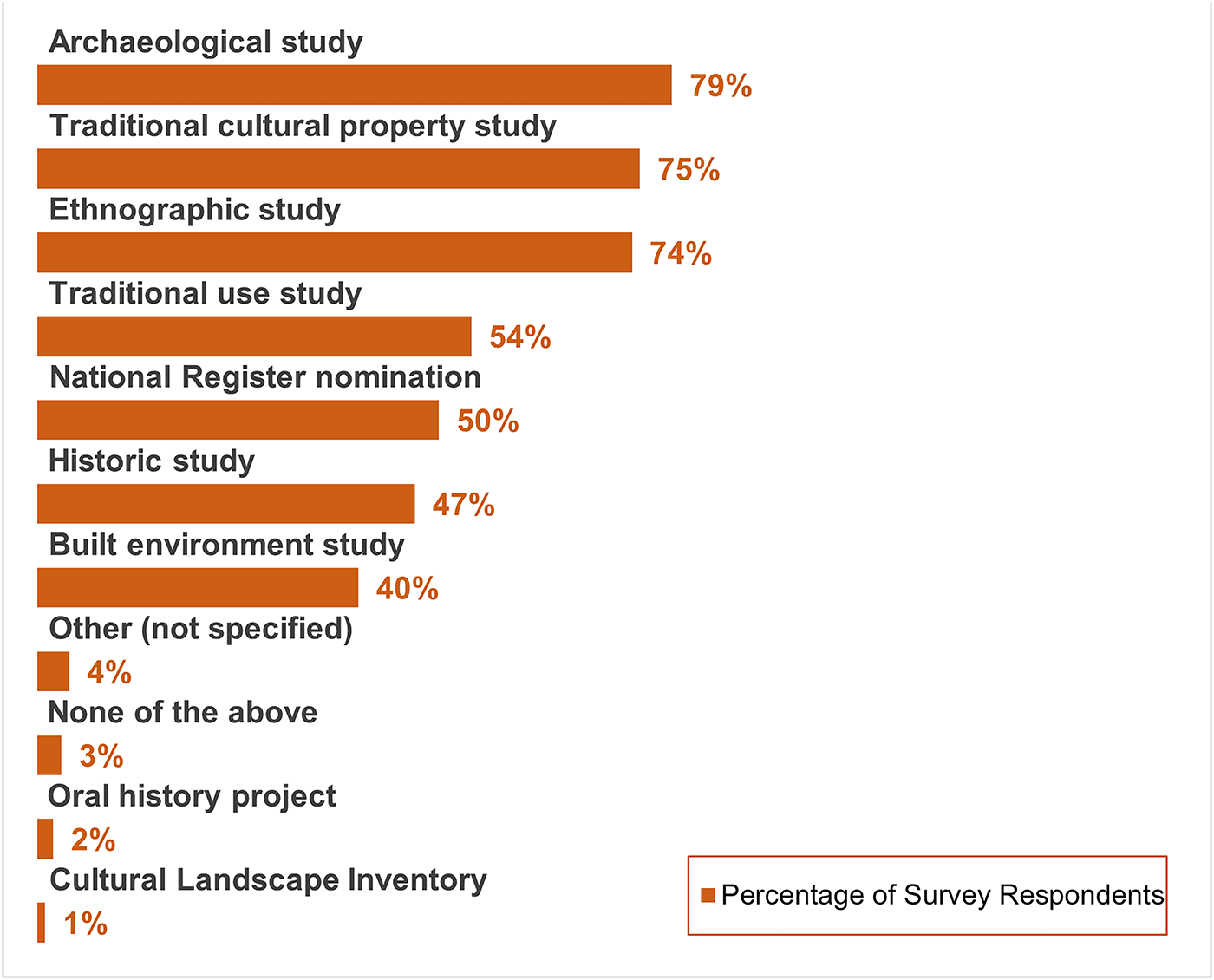

The survey responses further indicate perceptions that types of investigations other than cultural landscape studies are commonly used to identify, assess, and guide treatments for cultural landscapes. As depicted in Figure 5, approximately three-quarters of our respondents noted that they had seen cultural landscapes considered through archaeological studies (79%), TCP studies (75%), and ethnographic studies (74%). Roughly half of respondents had seen traditional use studies (54%), National Register nominations (50%), or historic studies (47%) used to identify and document cultural landscapes. Only 40 respondents had seen landscapes considered during built environment studies.

Figure 5. Percentages of survey respondents who reported cultural landscapes addressed in various types of studies.

Our results show that cultural landscape studies prepared for Section 106 reviews are used primarily to identify historic properties. All but one of the analyzed studies included historic property identification, and 46% of respondents indicated they had seen cultural landscapes studies used for historic property identification. Although historic property identification is a common contribution of cultural landscape studies, boundary delineation was a function in only 42% of the analyzed studies. This contrasts with our survey results, in which 73% of respondents said boundary delineation was “important” or “very important.” This discrepancy may have a practical explanation: National Register Bulletin 38 notes that defining the boundaries of large landscapes is often challenging (Parker and King Reference Parker and King1998:18). In many cases it is more practical to treat an entire APE as part of a larger cultural landscape with undefined edges (e.g., Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Juan, Hopkins, Ferguson and Mankel2013). One study went further: “Do we need to define [boundaries] in order to consider impacts? If we don’t, there’s no earthly reason to get involved in the complex, usually arbitrary, exercise of defining them” (King Reference King2004:13).

Furthermore, only 31% of the analyzed studies assessed the potential effects of individual undertakings on identified historic properties, and only 27% proposed treatments for those properties. Most of the studies were apparently designed to provide context for Section 106 reviews, rather than to advise agency officials concerning the evaluation, assessment, or treatment of historic properties. Without reviewing the broader administrative record of the federal undertakings behind these studies, our analysis could not assess how these studies’ findings were integrated (or not) into outcomes from their respective Section 106 processes.

Methods Used in Cultural Landscape Studies

The broad support for cultural landscape studies that make diverse contributions in the Section 106 process invites attention to why and how such studies are conducted. We quantified methods used in available cultural landscape studies and asked survey respondents about their preferences for conducting a hypothetical cultural landscape study. We sought to understand the guidance that investigators follow, the lines of evidence they use, and the benefits produced by cultural landscape studies.

Guidance. Beyond the guidance provided by the NPS’s Cultural Landscape Program, which focuses on built environments, authoritative recommendations on how to identify and evaluate cultural landscapes and their contributing elements are limited. To understand cultural landscape research methodologies, we examined citations in the available cultural landscapes studies and asked survey respondents to tell us how likely they were to use existing guidance for a cultural landscape study (Advisory Council on Historic Preservation 2012a, 2012b; National Park Service 1997; Parker and King Reference Parker and King1998; Seifert et al. Reference Seifert, Little, Savage and Sprinkle1997).

We found convergence in the guidance used in completed studies and that recommended by survey respondents. Most studies used, and most respondents said they would use, National Register Bulletin 38 (Parker and King Reference Parker and King1998) to guide cultural landscape investigations. Nearly 60% of the studies used National Register Bulletin 38 as guidance. Similarly, 65% of respondents said they were very likely to use the National Register Bulletin 38 for guidance when conducting a cultural landscape study.

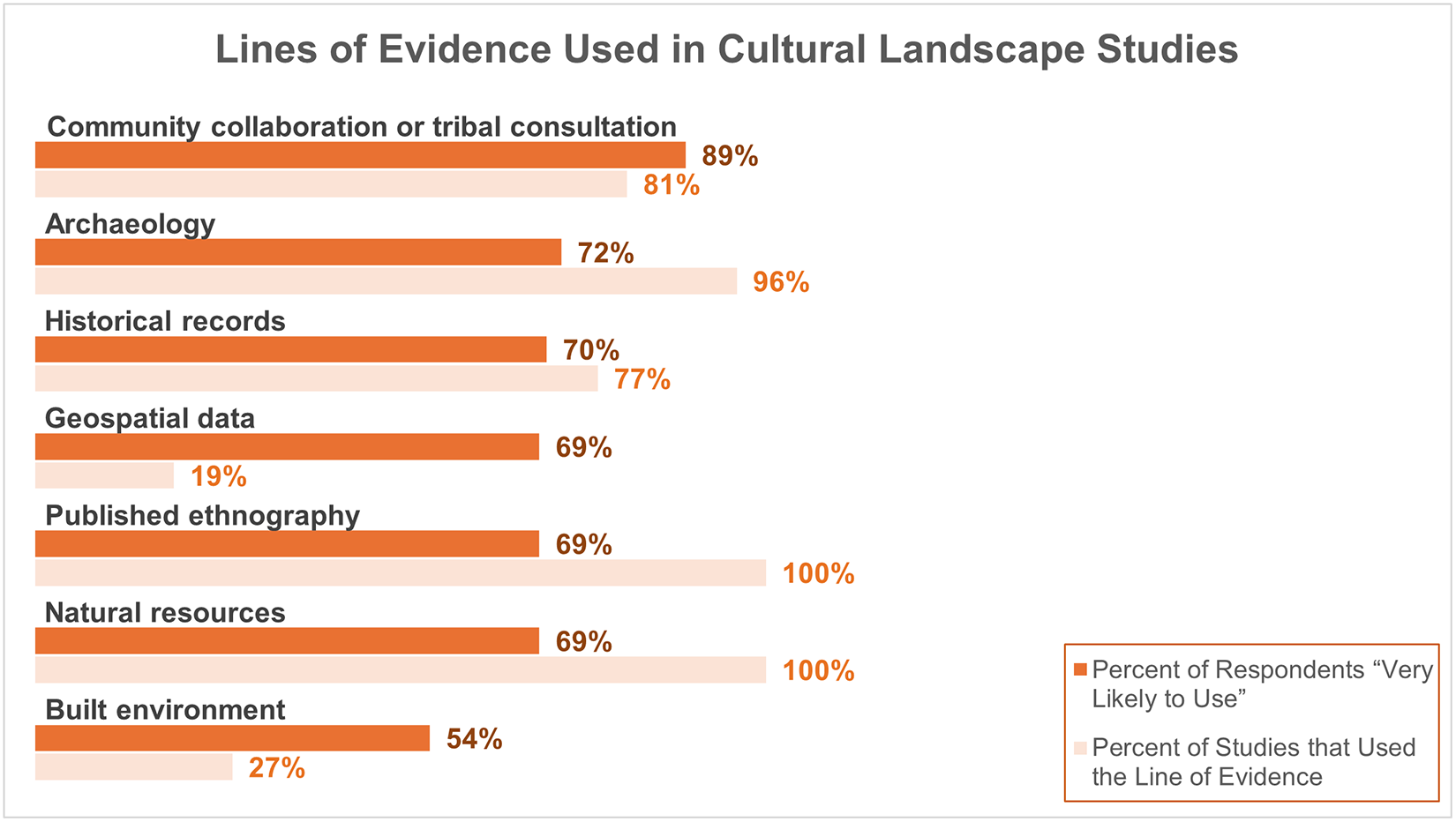

Lines of Evidence. Our analysis of available cultural landscape studies indicates that they generally rely on community collaboration or consultation and are multidisciplinary, meaning inclusive of ethnographic, archaeological, natural resource, and historical methods and data. Every study we assessed used at least two methods, with an average of 4.7 methods per study. This comports with the survey results: respondents said they were very likely to draw on a range of evidence for a hypothetical cultural landscape study, including community collaboration or consultation, archaeology, historical records, published ethnography, and geospatial data (Figure 6). One respondent wrote, “I think you'd want to integrate and synthesize all available data and try to break [landscapes] from the shackles of individual sites.”

Figure 6. Percentages of survey respondents who reported various lines of evidence as “very important” in cultural landscape studies and the percentage of analyzed studies that used the line of evidence.

Although the available studies are predominantly multidisciplinary, each was tailored to distinctive suites of cultural resources and community ties associated with a specific landscape. Our survey respondents also emphasized this need for adaptability, as one respondent wrote, “Don't try for a one-size-fits-all set of practices since cultural landscapes are usually extensive, often complex in their conception and use, and vary by culture and group.” Put simply by another respondent, “The source of data you use depends on the context.”

One important throughline in guidance policy, the assessed reports, and the survey results is the need for direct community collaboration or Tribal consultation in cultural landscape studies. National Register Bulletin 38 stresses the need for engagement with “individuals and groups who may ascribe traditional cultural significance to locations within the study area” (Parker and King Reference Parker and King1998:6). More than 75% of the studies included ethnographic fieldwork or interviews. Nearly 90% of survey respondents said that they would very likely employ community collaboration or Tribal consultation in a hypothetical study. One respondent wrote, “What is most important to me is to try to understand from traditional knowledge holders how and why a cultural landscape is important and then try to work through the (very imperfect) Section 106 process to try to find ways to protect those important things.”

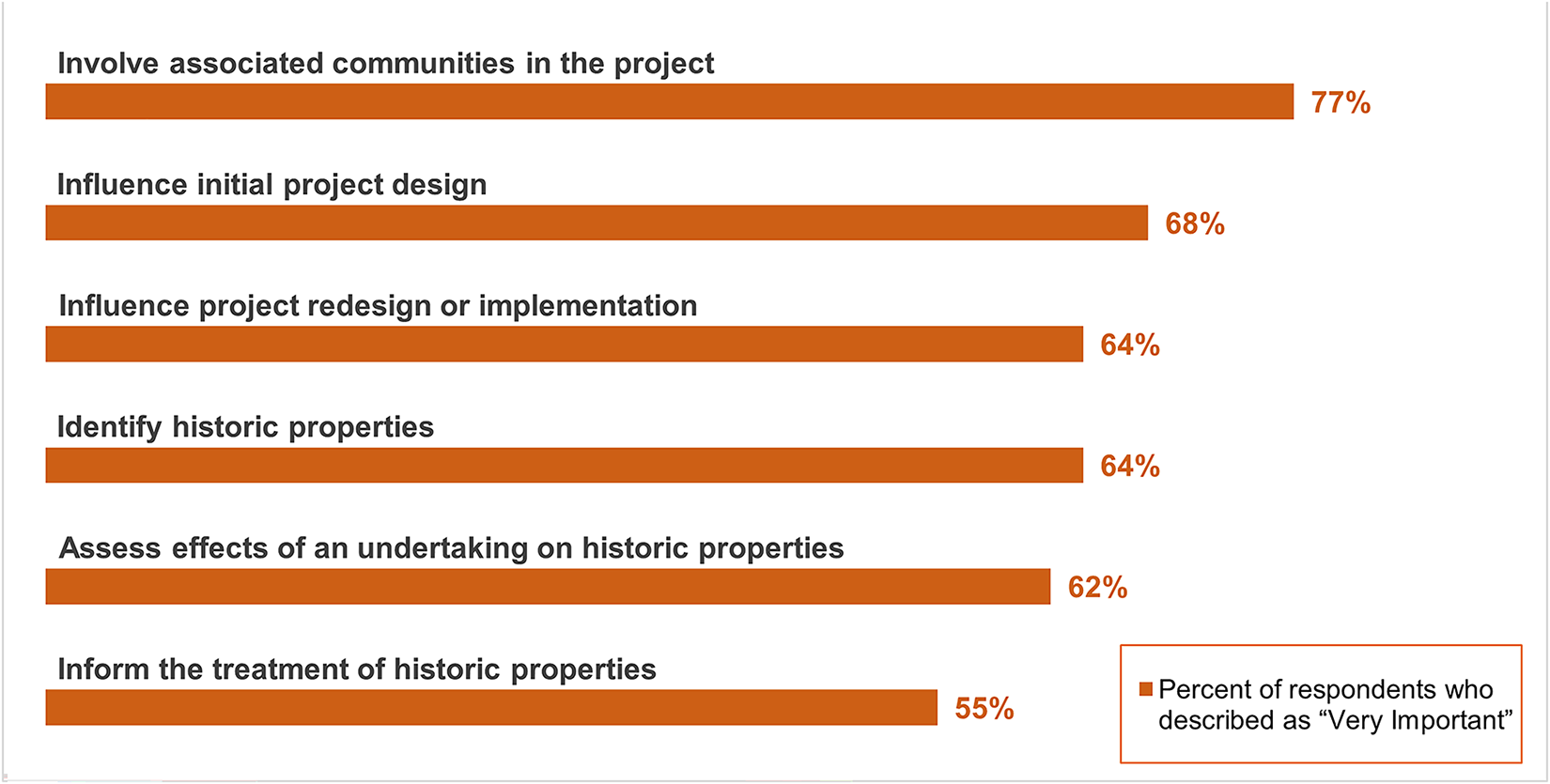

Benefits. Our assessment of available studies and answers from survey respondents suggests that these studies were primarily used for historic property identification. When asked to rate the importance of multiple outcomes of cultural landscape studies used in Section 106 reviews, however, respondents reported diverse benefits beyond historic property identification (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Percentages of survey respondents who reported benefits from cultural landscape studies as “very important.”

When asked about benefits from cultural landscape studies, roughly two-thirds of respondents reported that influencing initial project design (68%), identifying historic properties (64%), influencing project redesign or implementation (64%), and assessing the effects of an undertaking on historic properties (62%) were all very important. Most respondents think cultural landscape studies should be used to inform all aspects of the Section 106 process and should be undertaken early in project development. One respondent wrote, “To manage land you must manage landscapes. Landscapes can dictate what types of projects are appropriate … for the environment of the landscape.” Another respondent stressed the importance of considering cultural landscapes in the initial project design, writing, “Nobody considers cultural properties, much less landscapes, during the initial project design process, when they should because it could save considerable headache and money later.”

A robust 77% of respondents think involving associated communities in undertaking reviews is a very important benefit of cultural landscape study. One respondent wrote, “For tribal communities especially, [cultural landscapes studies] provide an opportunity for their perspectives on the landscape and a project to be recognized and incorporated.” Another respondent noted how cultural landscape studies can build relationships between agencies and communities: “The process of conducting a [cultural landscape] study … should establish good working relationships between the agency and the traditional communities. These relationships can be retained and maintained through collaboration on implementation of the action items of the [cultural landscape] study.”

Some respondents indicated that cultural landscape studies are most valuable as holistic planning tools detached from specific undertakings. One respondent wrote, “It would be ideal if these were done prior to the beginning of any project design phase. Almost like a [Section] 110 process.” To some respondents, completing cultural landscapes beyond the confines of the Section 106 process would help realize the potential for landscape-scale approaches to cultural resource management. One respondent noted, “The reason to consider a landscape perspective is to identify those values important to various groups and to empower the parties to think broadly and comprehensively about appropriate measures to protect heritage values irrespective of any single undertaking.” Another respondent wrote, “Looking at things from a landscape scale also makes it possible to assess cumulative effects of multiple undertakings on a landscape that would otherwise go unidentified and unmitigated.”

Discussion and Recommendations

Section 106 regulations and guidance instruct federal agencies to “match” historic property identification and assessment efforts to the scale and complexity of undertakings and to the values and preferences of affected communities. Even so, some federal agencies perpetuate a pre-1992 “checklist” approach to the Section 106 process that privileges archaeological and architectural methods for historic property identification and assessment, devalues community perspectives, and discounts regulatory mandates to scale investigations to the scope and complexity of individual undertakings (Welch Reference Welch, Ryan, Jones, Koerner and Lee2012). Critical responses to the “checklist” approach, including global shifts in heritage conservation policy and local advocacy for more holistic approaches to Section 106, have brought cultural landscape studies to the fore as means for understanding co-developments in human and ecological systems (Cleland Reference Cleland, Goetcheus and MacDonald2008; Douglass and Manney Reference Douglass and Manney2020; Hogg et al. Reference Hogg, Welch and Ferris2017; Spears et al. Reference Spears, Dongoske, Seowtewa, Hopkins and Ferguson2024). Cultural landscape studies have evolved from their initial focus on parks to become practical tools to assist federal agencies in deepening and broadening contextual considerations of undertakings by learning from and seeking agreement with Tribes, consulting parties, and stakeholders.

Most cultural landscape studies mobilize suites of cultural, historical, and geographic information to illuminate places threatened or otherwise affected by federal actions. For example, Boraas and coworkers’ (Reference Boraas, Stanek, Reger and King2015) study of the Ch’u’itnu Traditional Cultural Landscape in Alaska addresses ancient and recent cultural contexts, integrating archaeological, ethnographic, and historical records with interviews with community members. The study employs guidance from National Register Bulletin 38 (Parker and King Reference Parker and King1998) to identify historic properties significant to affected communities, establishing its relevance to the Section 106 process. In another example, the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition’s collaborative land management plan draws on information provided by five Tribal Nations and was collaboratively designed and implemented from conception to completion (Chuipka Reference Chuipka2022). The study integrates perspectives on and preferences for multiple aspects of Bears Ears National Monument management, thus establishing a useful framework for Section 106 reviews.

In part because of creative and diligent attention to making landscape-scale knowledge relevant to on-the-ground decisions (see Altschul [Reference Altschul2016] and co-published articles), as of 2024, there is near-consensus among policymakers, historic preservation professionals, Tribes, and researchers that cultural landscape studies can and should be employed in planning and evaluating region-scale proposals for change. Federal policy, expert opinion, the content of previous cultural landscape studies, and our professional experience establish cultural landscape studies as valuable additions to Section 106 review “tool kits.” Such studies effectively integrate and mobilize the diverse data and perspectives needed to understand undertakings in their cultural, historical, and geographic contexts; to identify TCPs that most archaeologists cannot “see”; and to anticipate the ways that proposed changes may harm places and communities. Used effectively, cultural landscape studies support federal agencies in meeting both consultation and proportionality standards for Section 106 reviews of complex or large-scale undertakings. Despite these benefits, cultural landscape studies are not systematically conducted for major undertakings and are sometimes inadequate when they are.

Why Aren’t Cultural Landscape Studies Common?

The wide appreciation for and demonstrated advantages of cultural landscape studies prompt questions about why these studies have yet to be consistently applied, even for undertakings that are large, complex, and located within areas having known importance to Tribes or local communities. Although our data do not speak directly to this question, it is noteworthy that the same attributes of cultural landscape studies that make them useful to Tribes and preservationists may explain the lack of adoption by some applicants for landscape-scale change and some government agencies. Although some federal agencies embrace NHPA Section 110 responsibilities and proactive planning in some circumstances, reactions to proposals from industrial undertaking applicants often prioritize Section 106 processes that are familiar, systematic, and predictable; that is, the “checklist” approach. Customary agency practices for Section 106 reviews before there were mandates to consider TCPs emphasized the identification of individual, spatially discrete archaeological and architectural localities. As open-ended, context-sensitive investigations that place Indigenous and local community perspectives on par with those of professional archaeologists, cultural landscape studies can add uncertainty to Section 106 reviews.

Fear of the unknown may explain resistance to cultural landscape studies by some federal agencies, including BLM, and some undertaking applicants, including Pattern Energy. Even as most practitioners (including federal agency archaeologists who responded to our survey) affirm the need to consider cultural landscapes, and even as federal policy directs federal agencies to tailor Section 106 processes to undertakings and their contexts, the results of Section 106 reviews for individual undertakings too often lack community sensitivity and context specificity at meaningful spatial and cultural scales. Without firmer and more readily applicable guidance to federal agencies and more consistent implementation in accord with recognized standards, the benefits of cultural landscape studies to Section 106 processes cannot be realized. The roots of failures to proactively identify, evaluate, and manage cultural landscapes outside the Section 106 process lie in systemic inattention, on the part of BLM and other agencies, to compliance with the inventory provisions of NHPA Section 110 (U.S.C. 54 § 306102). Compliance with Section 110 by the BLM may not have averted the SunZia conflict, but closer attention to the NHPA’s Section 106 mandates—that is, to look for and assess TCPs and to seek agreement in consultations—would surely have helped.

SunZia is just one example of a complex undertaking affecting areas having known significance to Tribes and local communities in which the Section 106 process unfolded without a cultural landscape study or any effort to understand the project and the affected historic properties in their cultural, historical, and geographical contexts. BLM and SunZia officials ignored highly salient published studies, explicit declarations from Tribes, and specific requirements from the Arizona Corporation Commission in favor of preordained and archaeology-centered Section 106 process completion. The checklist focus of the Section 106 review for SunZia is resulting in unanalyzed and unmitigated adverse effects and significant impacts to various TCPs, including the San Pedro Valley itself. The preferences exhibited by the BLM and Pattern Energy evolved through early commitments to the identification of spatially discrete archaeological and architectural localities, followed by either avoidance or information-salvaging “mitigative excavation” of properties slated for destruction (Douglass and Manney Reference Douglass and Manney2020; Spears et al. Reference Spears, Dongoske, Seowtewa, Hopkins and Ferguson2024; Suagee and Bungart Reference Suagee and Bungart2013; Welch et al. Reference Welch, Riley and Nixon2009).

For SunZia and other complex and landscape-scale undertakings, the time is ripe to dispense with procedural biases and resistances that are inconsistent with the letter and spirit of NHPA and associated policies, harmful to places and people, and unworthy of their outsized influences in public land decision-making. Cultural landscape studies are not perfect, but they are recognized and available tools for escaping the confines of archaeology-centered Section 106 reviews and pursuing the NHPA’s stated mission, “Protection of Historic Properties.”

Toward Standards for Cultural Landscape Study Adequacy

Even as Section 106 practitioners express preferences for inclusive, open-ended, integrative cultural landscape studies, most are well aware of pressures for efficiency and feasibility in Section 106 processes. Practitioner opinions suggest emerging standards for implementing cultural landscape studies and for assessing their adequacy. Even though there can be no rigid or context-independent rules for specifying when, where, or how to conduct cultural landscape studies, the obvious overlaps among government policies, practitioner preferences, and completed studies converge on a set of draft standards for applying cultural landscape studies in the Section 106 process.

The foremost standard is study completion. Study denominations, report titles, and specific methods generally matter less than some form of systematic consideration in Section 106 reviews for large and complex undertakings of the full spectrum of historic properties, including TCPs, and of the interrelations among individual historic properties in landscape contexts. Cultural landscape studies provide sturdy and flexible frameworks for engagement among federal agencies, project applicants, and communities and for the integration of diverse information into larger historical, cultural, and geographical contexts.

Our experience and our analyses of prior studies and practitioner survey responses point to six additional standards for cultural landscape studies that contribute effectively to Section 106 processes:

1. Early adopted: completed soon enough in the planning stages for alternative designs to be considered

2. Community engaged: reflective of the values, interests, and preferences of the groups of people who maintain the cultural landscapes and are affected by proposed changes

3. Context focused: attentive to landscape-specific human and ecological systems, their co-development, and their physical and cultural manifestations

4. Multidisciplinary: inclusive of available information, including ecological, cultural, historical, oral-traditional, and geospatial

5. Integrative: a creative synthesis of diverse information for use in the Section 106 process and related compliance, research, and preservation efforts

6. Consequential: influential in decision-making, especially in the identification of National Register–eligible historic properties, in the modification of undertaking plans, and in the translation of community values into recommendations for historic property treatments

A Cultural Landscape Study for SunZia?

In the context of the SunZia transmission line, our analyses and the standards they suggest generate four specific insights into how the Section 106 process could have been more informative and less contentious if the cultural landscape study had been conducted before construction, as required for the Arizona portion of the project by the Arizona Corporation Commission:

1. Engagement with Tribes and Other Communities: The cultural landscape study would have provided additional opportunities for Tribes and other communities to understand the SunZia proposal in local geographical contexts. Such understandings would have allowed community representatives to offer feedback to the BLM and the Pattern Energy applicant on diverse subjects, including alternative routes; the range, distribution, and magnitude of project effects; and the places and traditions affected by alternate and preferred routes. The agreed-on cultural landscape study would have gathered, organized, and presented information relevant to specific places, land uses, and geographical and cultural changes through time. Ongoing government-to-government consultation requirements are avenues for Tribes to inform the BLM about these and related matters.

2. Identification of the San Pedro Valley as a Significant Cultural Landscape: Completion of the required cultural landscape study would have provided the BLM, Pattern Energy, consulting parties, and affected Tribes with a multidisciplinary lens to understand the project’s geographic, cultural, and historical contexts in holistic ways. Although it seemed obvious to some Tribes and consulting parties that the San Pedro Valley is a fragile and irreplaceable cultural landscape that is ill suited as an industrial corridor, the BLM’s historic property identification efforts and other factors apparently prevented agency officials from seeing the (landscape) forest for the (archaeological site) trees and from understanding the significance of the San Pedro Valley to Tribes and local communities.

3. Identification of Non-archaeological and Non-architectural Historic Properties: A cultural landscape study could have enabled opportunities for the identification of TCPs, cultural landscapes, and other historic properties less likely to be identified by archaeologists and architectural historians. This study would have obliged the BLM and Pattern Energy to consider the values that Tribes and other communities attach to archaeological, architectural, and other cultural resources within the project area. Such a study would likely have revealed interconnections among spatially discrete historic properties and situated individual places in relation to others and to geographic features. Tribes called for the BLM to follow the Section 106 regulations and identify TCPs as part of the historic property identification efforts as early as 2009, but these calls went unheeded. In keeping with Tribes’ requests, the BLM could have required a community-engaged historic property identification effort as a basis for a cultural landscape study. Such an effort would have gathered primary source information for alternate SunZia routes and made use of prior studies to identify, record, evaluate, and consider TCPs and cultural landscapes, including the San Pedro Valley and other SunZia impact areas.

4. Information on Adverse Effects to Historic Properties and Culturally Appropriate Treatments: A cultural landscape study would have informed the BLM’s consideration of the adverse effects of SunZia on historic properties by integrating data and perspective on local and regional history, culture, land uses, place names, and associated values, including those shared by Tribes and local communities. The BLM and Pattern Energy would have had opportunities to use such information (1) to broaden understandings of the indirect and cumulative impacts on both places and communities of SunZia construction and (2) to design and implement actions, possibly in collaboration with Tribes, to avoid and reduce adverse effects and significant impacts, including the significant and incompletely mitigated erosion, stream siltation, and native vegetation displacement and fragmentation already underway in late 2024.

We are not suggesting that a cultural landscape study for SunZia would have resolved every issue in the undertaking’s Section 106 review and impact assessment. We are convinced, however, that a cultural landscape study would have complemented the BLM’s Section 106 and National Environmental Policy Act compliance processes by providing a multidisciplinary and community-engaged lens through which the agency could “stop, look, and listen” as part of its planning efforts. The BLM and the SunZia applicant might still have included San Pedro Valley in the SunZia route, even after completing an agreed-on cultural landscape study. Nevertheless, a cultural landscape study would have bolstered BLM claims that it appropriately considered historic properties affected by the SunZia undertaking and Pattern Energy’s assertions of compliance with the Arizona Corporation Commission Certificate of Environmental Compatibility. The vigorous legal defense mounted by the BLM and Pattern Energy to counter the Tribes’ requests to complete the agreed-on cultural landscape study and treat the San Pedro Valley as a TCP, or multiple TCPs, stands as both a cautionary tale and a warning to those who would seek Section 106 protections for treasured places.

Conclusion

Until Section 110 replaces Section 106 as the prime catalyst for historic property identification, Section 106 practitioners should rigorously exploit opportunities to identify and consider cultural landscapes and TCPs during the Section 106 process in consultation with Tribes and other knowledgeable parties. Cultural landscape studies have emerged as widely appreciated yet underused tools for achieving US policy mandates to match Section 106 review processes to the scale and complexity of specific undertakings. A one-size-fits-all approach to Section 106 reviews tends to leave cultural landscapes and TCPs under-identified, landscape-scale effects under-considered, and local and Tribal communities disproportionately harmed.

Cultural landscape studies should be included in the Section 106 process for most or all landscape-scale undertakings or those having widely distributed adverse effects. BLM’s commitment to a cultural landscape study for proposed solar energy infrastructures is a case in point (Van Der Linden Reference Van Der Linden2023). Further opportunities exist to reform federal agency policy and practice to consistently enlist cultural landscape studies in Section 106 reviews wherever indicated and to thereby give all due consideration to America’s spectacular landscapes, to the highly significant places that enrich those landscapes, and to the people who rely on, venerate, and dwell within historied places.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully recognize that our knowledge of cultural landscapes and our appreciation for their manifold values derive primarily from Apache, O’odham, Hopi, Jemez, and Zuni experts in traditional knowledge and law. Skylar Benedict expertly translated the abstract into Spanish. Special thanks for review/comments and other kindnesses to Lee Clauss, Bill Doelle, Kurt Dongoske, Chris Dore, Peter Else, T. J. Ferguson, Jami Macarty, Ian Milliken, Steve Nash, Michael V. Nixon, Paul Reed, Alex Ritchie, Kate Sarther, Howard Shanker, Peter Steere, Bern Velasco, Aaron Wright, the 179 respondents to our survey, the Advances editors and reviewers, and the colleagues we have undoubtedly forgotten to mention. No permits were required for this work.

Funding Statement

The Center for Biological Diversity, Heritage Business International, National Association of Tribal Historic Preservation Officers, New Mexico Archaeological Council, and Archaeology Southwest provided financial or administrative support for our research.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available in the Digital Archaeological Record (tDAR) at https://doi.org/10.48512/XCV8502232. The dataset includes an Excel file containing three supplemental tables that provide the underlying data used in the article and are archived for public access and future research.

Competing Interests

Archaeology Southwest is a co-plaintiff with the Tohono O’odham Nation, the San Carlos Apache Tribe, and the Center for Biological Diversity in litigation to compel the US Bureau of Land Management to follow Section 106 regulations for SunZia and the Arizona Corporation Commission and to enforce the SunZia Certificate of Environmental Compatibility.