Introduction

Due to the history of colonization, many speakers of African languages who do not speak a language of colonial origin, such as English or French, are inequitably excluded from participating in the reception, dissemination and reproduction of modern STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) knowledge. Efforts to indigenize modern STEM in Africa began mainly in the realm of education within the huge body of work on mother tongue education (MTE) (see, for example, UNESCO 1978; Bamgbose Reference Bamgbose1983; Akinnaso Reference Akinnaso1993; Ouane and Glanz Reference Ouane and Glanz2010; Brock-Utne and Alidou Reference Brock-Utne and Alidou2006; Prophet and Dow Reference Prophet and Dow1994; Wilmot Reference Wilmot2009; Fafunwa et al. Reference Fafunwa, Macauley and Sokoya1989). This body of knowledge has shown the effectiveness of teaching school subjects, including STEM, to African students in their local languages. This means that the indigenization of modern STEM in Africa has been largely limited to the domain of formal education. However, efforts have now emerged that seek to indigenize STEM not for the classroom but for the general African public, taking advantage of the affordances of social media.

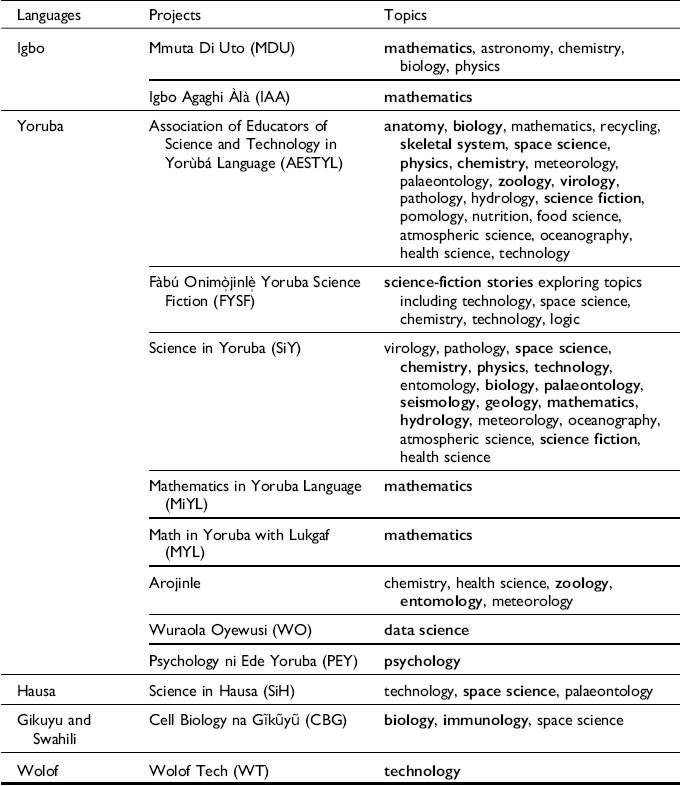

These efforts, as far as I am aware, began around 2016. Science in Hausa (SiH; L-1Footnote 1) and Fàbú Onímò̩jìnlè̩ Yoruba Science Fiction (FYSF; L-2; L-17) emerged on Facebook in 2016. Then, in 2017, the Association of Educators of Science and Technology in Yorùbá Language page (AESTYL; L-3) also emerged on Facebook. One thing that these projects have in common is that their STEM contents (explanatory or fictional) are short, written articles accompanied by some images. ‘STEM-for-the-public’ content in African languages adhered to this basic form until 2020, when Science in Yoruba (SiY; L-4; L-5) and then Mathematics in Yoruba Language (MiYL; L-6) appeared on Facebook. STEM-for-the-public projects that emerged after these initiatives include Wolof Tech (WT; L-7) and Cell Biology na Gĩkũyũ (CBG) in 2020 (L-8), Math in Yoruba with Lukgaf (MYL) in 2021 (L-9), and Arojinle (L-10) and Wuraola Oyewusi (WO) in 2022 (L-11). Psychology ni Ede Yoruba (PEY; L-12), Mmuta Di Uto (MDU; L-13) and Igbo Agaghi Àlà (IAA; L-14) all emerged in 2023 and were the most recent STEM-for-the-public projects when this article was written.

Given this trend where STEM-for-the-public projects have consistently been appearing every year in different contexts in Africa since 2016, it seems safe to assume that the near future will see a proliferation of STEM-for-the-public projects. In fact, while this article was under review, four new projects emerged across different platforms: Olùkọ́ Kẹ́mísírì in 2024 (L-25), Tech in Yoruba in 2023 (L-26), and Agọ Imọ Ayelujara (L-27) and Usiro Nede Ujebu in 2024 (L-30). STEM-for-the-public projects are not simply translation endeavours. What they do is take a STEM concept and explain it in an African language to a local African public, sometimes drawing on locally meaningful knowledge and oral culture.

The analyses below are based on more than three years of digital ethnography. I have been following these projects since 2017 out of personal curiosity, but it was not until 2020 that I started engaging actively in online participant observation. My virtual participant observation includes sharing, reposting and commenting on the videos and articles posted by the projects. I interacted actively with social actors involved in some of the projects (some of whom became personal friends), but for anonymity and privacy concerns, and since ethical protocols guiding data collection in digital spaces are not yet well developed (Delfino Reference Delfino2021: 243), I have limited my descriptions to what is publicly available online. This article contributes to a growing body of work on cultural and linguistic practices in digital spaces by showing that findings in academic studies (MTE in this case) can take a practical turn in informal digital spaces. As I show below, some STEM-for-the-public projects demonstrate a substantial connection with pioneering MTE efforts in Africa.

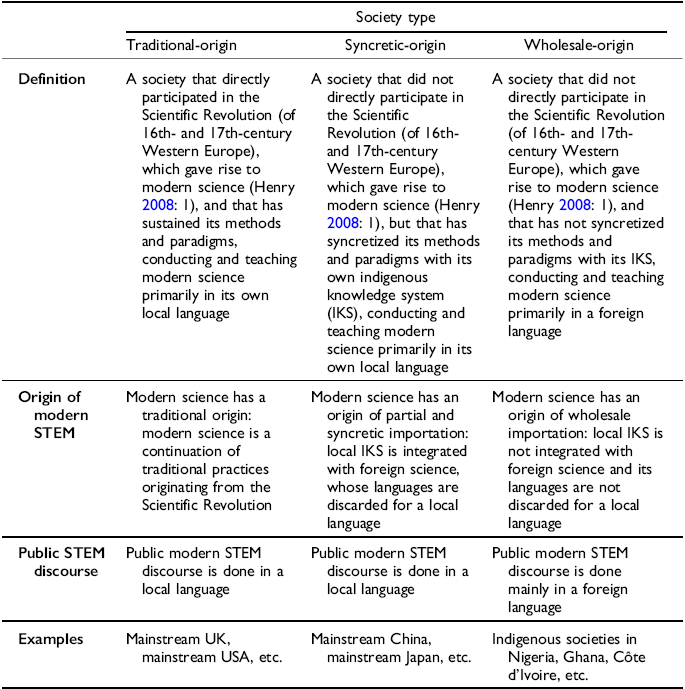

In what follows, I first situate the projects within the indigenization literature and show that, just as the MTE that came before them constitutes a pedagogical solution, STEM-for-the-public projects constitute a cultural intervention that emerged in the fashion of Cohen (Reference Cohen and Jenks2003) as an attempt to solve a cultural problem: the unequal access to modern STEM knowledge that characterizes the modern world, where societies that I describe as ‘wholesale-origin’ societies (like those in Africa, south of the Sahara) have restricted access to this knowledge since it is not available in the language of the common public, in contrast to ‘traditional-origin’ societies (such as mainstream USA and UK) and ‘syncretic-origin’ societies (such as mainstream China). I have proposed these types of society, based on historiographic considerations (Henry Reference Henry2008), as a heuristic to provide a context for the emergence of these projects. I outline their basic distinctions in Table 1 and provide more context in the next section.

Table 1. Types of society.

Then, I draw a distinction between two lines of research in the indigenization literature (the L (language) paradigm and the MCD (methodology–conclusion dyad) paradigm) and show that STEM-for-the-public projects primarily fit within the L paradigm even when they sometimes exhibit the aspirations of the MCD paradigm. Next, I provide an ethnographic description of the projects, highlighting their modes of operation, the topics they cover, their linguistic approaches, their modalities, their impacts, and the pushback they encounter. I have done this to provide initial conceptualizations that can be investigated further in future work. Ethnographic description is my major focus in this article; all other conceptualizations are meant to aid this description. My digital fieldwork reveals that, although three modes of operation can be identified (individual, association and collaboration modes), these projects are driven by single individuals without whom a project might collapse. A review of post topics shows that, apart from STEM content, some projects post about things like advertisements and competitions. I note that this can increase the value of a local language as a form of linguistic capital. While the projects can be grouped into three categories according to their linguistic approaches (monolingual, bilingual and translanguaging approaches), all of them make use of a colonial language in their titles, suggesting that these foreign languages are still indispensable for these projects. The projects operate in three modalities: audio, written–pictorial and audiovisual frames. I observe that projects adopting the audiovisual frames attract significantly more engagement than those adopting the written–pictorial frame. Finally, I show that, while they appear to be making some recognizable impacts, these projects, in their current forms, are not an ultimate solution to the problem of unequal access and relevance. I also note that some followers of these projects still believe in the expressive superiority of colonial languages.

Traditional-origin, syncretic-origin and wholesale-origin societies

Every society has its own body of STEM knowledge. There is no question about these traditional bodies of knowledge being valid and legitimate STEM in their own right. However, we must distinguish between this form of knowledge, which has been variously described as traditional knowledge, indigenous knowledge, native science, traditional ecological knowledge, indigenous knowledge systems and indigenous environmental knowledge (see, for example, Rajasekaran Reference Rajasekaran1993; King and Schielmann Reference King and Schielmann2004; Morgan Reference Morgan2006; Hikuroa et al. Reference Hikuroa, Slade and Gravley2011; Owusu-Ansah and Mji Reference Owusu-Ansah and Mji2013; David-Chavez and Gavin Reference David-Chavez and Gavin2018; Garcia Jr et al. Reference Garcia-Olp, Nelson, Hinzo and Young2020; Garcia-Olp et al. Reference Garcia-Olp, Nelson, Hinzo and Young2020; Alexiades et al. Reference Alexiades, Haeffner, Reano, Janis, Black, Sonoda, Howard, Fiander and Buck2021; Sumarni et al. Reference Sumarni, Sudarmin, Sumarti and Kadarwati2022; Chahine Reference Chahine2022), and modern STEM, which is what is taught to students in schools around the world.

In this article, I follow Chahine (Reference Chahine2022) and simply refer to the form of STEM knowledge produced by each society as an indigenous knowledge system (IKS). Modern STEM is nothing more than an IKS (the European IKS – what Elshakry (Reference Elshakry2010) calls ‘European sciences’) that originated in the Europe of the 1600s (Betz Reference Betz2011: 21; Henry Reference Henry2008: 1) and was globalized through colonization, imperialism, capitalism, Christian missionaries and hegemony. We must recognize two aspects of this European IKS: its language and its MCD. This recognition is important since the importation of the European IKS around the world differs from one context to another principally because of these two aspects. In some places, the importation was characterized by what Elshakry (Reference Elshakry2010) describes as conceptual syncretism, where the local IKS merged successfully with the MCD of the incoming European IKS but discarded its language (e.g. English). This was the case in China, where the MCD of the European IKS (but not its language) was incorporated into the local IKS (see Elman Reference Elman2003; Elshakry Reference Elshakry2010: 102). The Chinese did this importation through a form of conceptual appropriation (Elshakry Reference Elshakry2010: 102) that frames the methodology of the European IKS as being originally Chinese. The same conceptual syncretism can be found in the incorporation of the MCD of the European IKS in Egypt in the 1800s (Elshakry Reference Elshakry2010: 101). Here, too, the European IKS was adapted to the language of the local IKS.

In other places, however, the spread of the European IKS was characterized by what I call ‘wholesale importation’, where both the language and the MCD of the European IKS were instituted through various kinds of coercion, often in the form of settlement and exploitation colonization. Modern STEM, therefore, cannot be a homogeneous concept when considered historiographically. For some societies, it is a continuation of traditional ways of knowing. For others, it is a blend of the foreign and the local; while for yet others, it is a foreign epistemology that must be employed to explore the natural world. For ease of reference, let us refer to societies whose IKS became global (i.e. those in Europe) as traditional-origin societies, those with blended IKSs (such as China) as syncretic-origin societies, and those that experienced wholesale importation (like many African countries) as wholesale-origin societies.

There appear to be some differences between these three types of societies, but these differences seem to be dyadic in nature, with traditional-origin and syncretic-origin societies on one side and wholesale-origin societies on a seemingly polar opposite side. First, unlike children in traditional-origin and syncretic-origin societies, children in wholesale-origin societies must overcome a language barrier to gain access to modern STEM. Second, traditional-origin and syncretic-origin societies have literate publics that include people with and without advanced academic degrees who engage with new STEM knowledge and innovations in various ways. In wholesale-origin societies, people who do not speak a colonial language, and some without advanced degrees, are excluded from engaging with new scientific discoveries. Third, in wholesale-origin societies, the local language (and its IKS) is seen as inferior to modern STEM and its language and as useful only for vernacular interactions, not for deep thinking (Táíwò Reference Táíwò2022: 21). The unequal valuation of these knowledge systems (and their respective languages) then results in diminished identities (see, for example, Shizha Reference Shizha2010). Children in traditional-origin and syncretic-origin societies do not suffer the same kind of identity devaluation. Fourth, traditional-origin and syncretic-origin societies are at the forefront of STEM innovations, while wholesale-origin societies lag behind.

The indigenization framework and its two paradigms

The gaps between traditional-origin and syncretic-origin societies on the one hand and wholesale-origin societies on the other constitute an anthropological problem. Let us call it the problem of unequal access and relevance (Problem-UAR). Problem-UAR has attracted significant scholarship in the indigenization literature. The indigenization literature is different from the indigenous/traditional education literature, whose purpose is to conceptualize the various forms of indigenous education that predate both Islamic and European education systems in Africa and other wholesale-origin societies such as those in the Americas. Fafunwa (Reference Fafunwa1974) and Szasz (Reference Szasz2007) are good examples of this body of work. While the overarching goal of the indigenization literature is to change the nature of how modern STEM (and, more broadly, education and scholarship in general) is practised in wholesale-origin societies, we must not lump all of the studies together for the purpose of clarity and to be able to engage more critically with Problem-UAR.

We must recognize at least two research paradigms in the indigenization literature. One paradigm (the MCD paradigm) seeks to infuse modern STEM with local IKS.Footnote 2 Examples include:

the call for African indigenous knowledge ‘to be integrated into the global stage as part of the knowledge of the people of the world because it is time for the African voice to be heard’ (Owusu-Ansah and Mji Reference Owusu-Ansah and Mji2013);

the debate about ‘whether we should call for greater inclusion of Indigenous knowledge in research, which is for the most part driven by a western science paradigm, or should we call for a paradigm shift under which Indigenous knowledge and western science are on a more equal footing’ (Pearce Reference Pearce2018: 127);

the research practice of including ‘indigenous knowledge in climate change and other environmental change research and decision-making’ (Pearce Reference Pearce2018: 130);

the call to incorporate indigenous knowledge in disaster reduction research (Mercer et al. Reference Mercer, Kelman, Taranis and Suchet-Pearson2010);

the call to integrate ‘traditional weather forecasting renowned indigenous knowledge system (IKS) [sic] into modern weather forecasting methods to be used for planning farming activities’ (Irumva et al. Reference Irumva, Twagirayezu and Nizeyimana2021: 55);

the argument that ‘indigenous knowledge systems need to be incorporated into agricultural research and extension organizations’ (Rajasekaran Reference Rajasekaran1993: 7);

a study ‘on how indigenous knowledge related to Indonesian traditional medicines could be incorporated into STEM-integrated science learning’ (Sumarni et al. Reference Sumarni, Sudarmin, Sumarti and Kadarwati2022: 472);

a project that aims ‘to systematically document the Indigenous knowledge systems of Alaska Native people and to develop pedagogical practices and school curricula that appropriately incorporate Indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing into the formal education system’ (Barnhardt and Kawagley Reference Barnhardt and Kawagley2005: 15);

the argument that ‘[t]he integration of biomedicine, traditional healing, western medicine (integrative approach) can yield extensive results in healing the physical body and psychological illnesses’ (Shizha and Charema Reference Shizha and Charema2011: 167);

and several other arguments and calls from around the world.

Pedagogical approaches with similar goals, such as funds of knowledge (Moll and González Reference Moll and González1994), also primarily fall within the MCD paradigm.

The major concern of this body of work is not so much the language of the local IKS but the IKS itself. Whether the goal is to ‘create the necessary conditions for hitherto unknown knowledge to be revealed’ (Mazzocchi Reference Mazzocchi2006: 465) or for students to ‘feel empowered by what is taught’ (Garcia-Olp et al. Reference Garcia-Olp, Nelson, Hinzo and Young2020: 210) or ‘to help Indigenous students engage with STEM’ (ibid.: 212), the focus of this body of work is not to do modern STEM in the local language of an IKS but to incorporate a local IKS within modern STEM practices. This same paradigm can be found in the ‘indigenization of sociology’ literature, particularly in the scholarship of Akínṣọlá Akìwọwọ (Akiwowo Reference Akiwowo1999; Adésínà Reference Adésínà2002; Táíwò Reference Táíwò2021a; Reference Táíwò2021b; Connell Reference Connell2021; Pearce Reference Pearce2021, among many others). Adésínà (Reference Adésínà2002) calls this the Akiwowo Project, which argues that ‘mainstream world sociology can be enriched by insights brought from African oral literature, in general, and a genre of Yoruba oral poetry, in particular’ and that ‘Yoruba and other African languages can provide systematically linguistic and metaphysical representations of knowledge … for the development of … the body of explanatory principles of the social sciences’ (Akiwowo Reference Akiwowo1999: 116). Although the Akiwowo Project exhibits the second paradigm in the indigenization literature (L paradigm, described below), this is probably not the main thrust or significance of Akiwowo’s scholarship (see Táíwò Reference Táíwò2021b: 364). The major aim of the MCD paradigm is to complement mainstream epistemologies with insights from indigenous knowledge.

The second paradigm (the L paradigm), on the other hand, aims to make modern STEM (and other fields, such as sociology) accessible in the local language of an IKS. The second ‘pole’ of the Akiwowo Project, which aims to ‘do sociology in an African language’ (Táíwò Reference Táíwò2021a: 311), is a good example of this paradigm. However, the bulk of work in this paradigm has been done within the research tradition known as MTE. A classic example of this paradigm is the Ife Six Year Primary Project (Fafunwa et al. Reference Fafunwa, Macauley and Sokoya1989), which taught all subjects, except English, to elementary school pupils in south-west Nigeria using the Yoruba language throughout their primary education. Fafunwa et al. (ibid.: 134) found that ‘the child learns better and more effectively in his [sic] mother tongue or first language than in a second language’. Similar results have been reported from around Africa in countries including Botswana (Brock-Utne and Alidou Reference Brock-Utne and Alidou2006; Prophet and Dow Reference Prophet and Dow1994), Tanzania (Mwinsheikhe Reference Mwinsheikhe2002), Ethiopia (Heugh et al. Reference Heugh, Benson, Bogale and Gebre Yohannes2007) and South Africa (Wilmot Reference Wilmot2009). The main objective of MTE is to reproduce STEM and other forms of knowledge in a local language and teach this reproduction to students with the assumption that doing this will help them ‘to develop curiosity, manipulative ability, spontaneous flexibility, initiative, industry, manual dexterity, [and] mechanical comprehension’, to be ‘a better integrated and adjusted citizen in his [sic] community’ (Fafunwa et al. Reference Fafunwa, Macauley and Sokoya1989: 10, 143), and to be more attractive in the labour market (Pillay Reference Pillay2010: 106). So, unlike the MCD paradigm, it is not the objective of the L paradigm to infuse IKS into modern STEM. To be sure, Fafunwa et al. (Reference Fafunwa, Macauley and Sokoya1989) did not set out to teach local IKS as opposed to modern STEM. In fact, the original plan of the project was to simply translate existing textbooks for subjects such as mathematics and science into Yoruba (ibid.: 18), not to create mathematics or science curricula that are based on the Yoruba IKS. It appears, then, that the main goal of MTE is to enhance learning of school subjects (including modern STEM) by using local languages in the classroom, which in turn would produce a better society.

Although MTE is institutionalized in the form of national education policies in different countries around Africa, this institutionalization does not appear to have succeeded in producing publics who are literate in modern STEM in local languages, and especially not ones who can syncretize modern STEM with local IKS. While this failure may be due primarily to the fact that such institutionalization is often limited to pre-secondary and sometimes pre-college levels of education and to the fact that the resulting education policies are largely poorly implemented (Ojetunde Reference Ojetunde2012; Okebukola et al. Reference Okebukola, Owolabi and Okebukola2013; Igboanusi and Peter Reference Igboanusi and Peter2016) and even scrapped in some instances (Opoku-Amankwa Reference Opoku-Amankwa2009), I do not pursue the details of this failure in this article.

However, STEM-for-the-public projects might have just begun to inspire the emergence of common publics who can engage (i.e. comment on, reproduce, question and spread) modern STEM in local African languages. Taking advantage of the affordances of social media, these projects explain STEM topics in Yoruba, Wolof, Hausa, Gikuyu, Igbo and Swahili. Because their primary objective is to render modern STEM in the local language of the people, these projects, like MTE, fall within the indigenization paradigm. However, they differ in their focus. While STEM-for-the-public projects focus on STEM, MTE focuses not only on STEM but also on other knowledge areas, including the humanities. Whereas the focus of MTE is the classroom, the focus of these emerging projects is the general public. Their audience includes both literate (in the Western sense) and non-literate publics. If we conceive of classroom teaching simply as a form of knowledge reproduction (Parker Reference Parker2009: 152), then we can conclude that MTE seeks to reproduce modern STEM (and other forms of knowledge) in the local language for the classroom, while STEM-for-the-public projects seek to reproduce this knowledge in the local language for the general public. Both MTE and STEM-for-the-public projects constitute attempted solutions to Problem-UAR. This line of reasoning aligns with Cohen’s (Reference Cohen and Jenks2003) general theory of subcultures, which posits that subcultures emerge as a means to solve cultural problems. While MTE is primarily a pedagogical solution, STEM-for-the-public projects are primarily a cultural one. It is important to note that the only commonality between STEM-for-the-public projects and MTE is the desire to render knowledge in the native language of a local population.Footnote 3 STEM-for-the-public projects are not MTE projects. Generally, these projects did not derive from MTE, nor do they implement well-structured MTE projects domiciled within an institution, nor have they run any project that is anywhere close to the classic MTE projects that initially demonstrated the efficacy of mother tongue in knowledge transfer. As a result, STEM-for-the-public projects remain largely a matter of entertainment rather than formal education, a fact that is consistent with STEM-for-the-public programmes in other cultures, such as mainstream USA and China. Clear exceptions exist, however. Of all the STEM-for-the-public projects examined, only two (AESTYL and SiY) demonstrate any connection with MTE.

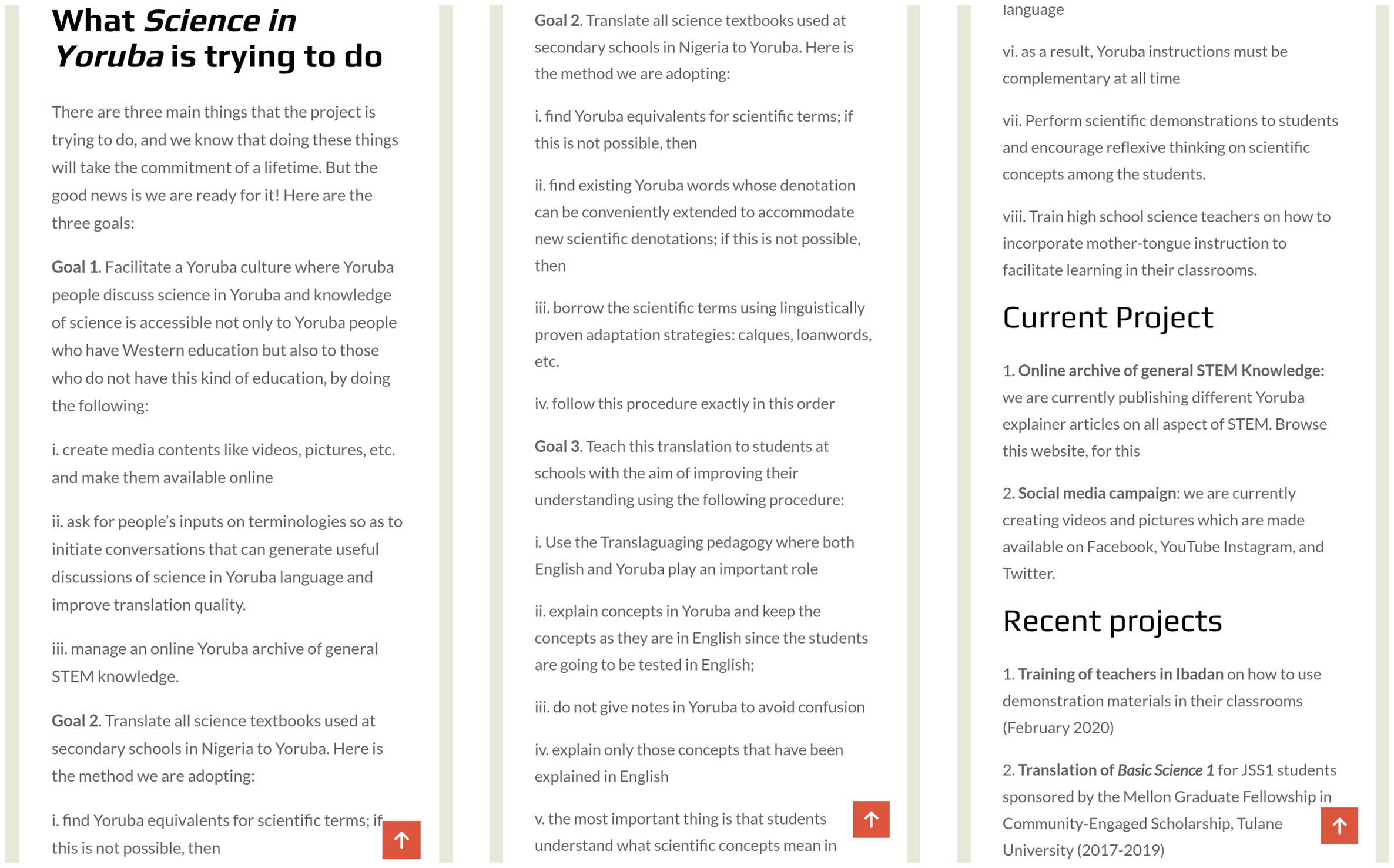

In L-22, the founder of SiY describes how SiY started in 2017 with an MTE project that translated a seventh-grade basic science textbook (for students aged ten to thirteen) into Yoruba and taught it to students in three schools in Ibadan, noting that the STEM-for-the-public phase of the project started in 2020. The implication of this project for MTE in Africa was recently published in the journal Language and Education (see Adebayo Reference Adebayo2024). L-22 also demonstrates that the current STEM-for-the-public phase of the project is meant to facilitate future MTE initiatives. This is also evident in Figure 1 (L-24). SiY exemplifies an MTE project that directly led to a STEM-for-the-public project.

Figure 1. SiY’s goals (L-24).

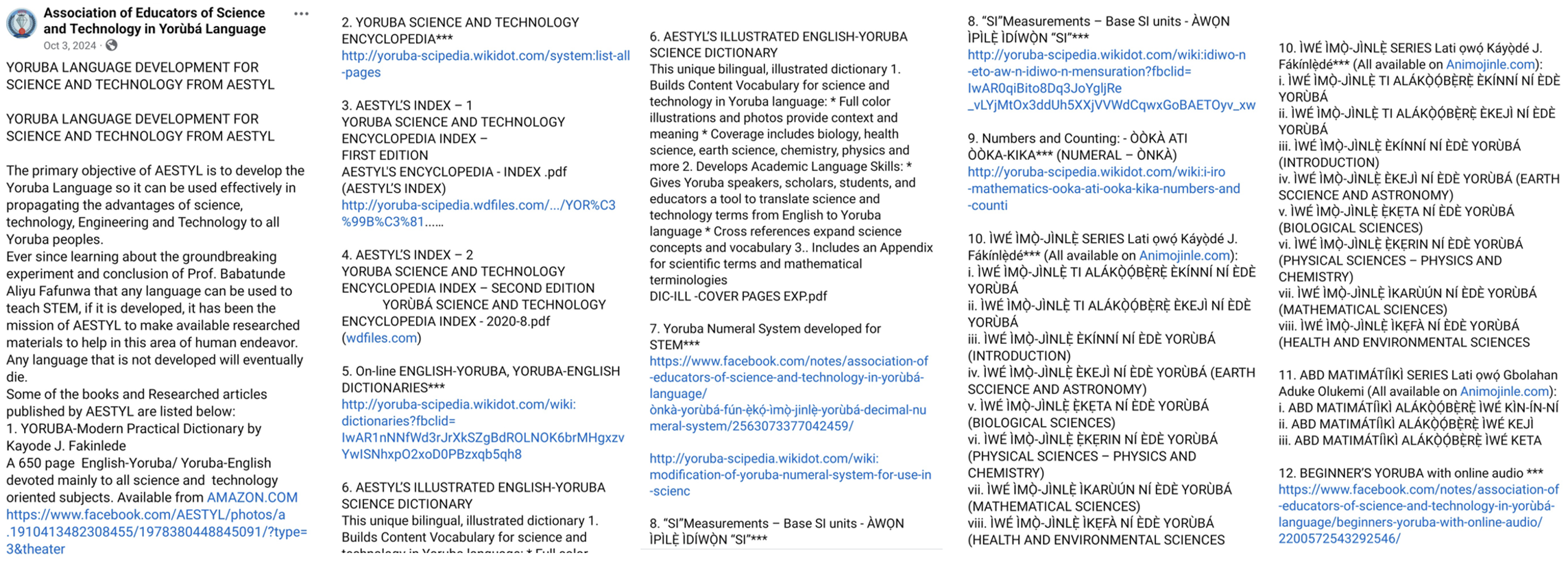

AESTYL is a clear case of a STEM-for-the-public project driven by MTE aspirations. In Figure 2 (L-23), AESTYL’s founder states that the MTE work of Fafunwa et al. (Reference Fafunwa, Macauley and Sokoya1989) was the main motivation for the project’s activities. AESTYL’s mission is to provide instructional materials that teachers can use to implement MTE in classrooms, and the project has generated several MTE materials, including books.

Figure 2. AESTYL’s goals (L-23).

It is also only these two projects that demonstrate any critical awareness of pioneering MTE efforts, such as the Ẹgbẹ-Onimọ-Ede-Yoruba that generated the Yoruba Metalanguage series (Bamgboṣe Reference Bamgboṣe1984; Awobuluyi Reference Awobuluyi1990; Adébọ̀wálé and Adélékè Reference Adébọ̀wálé and Adélékè2021), the adoption of Yoruba for thesis and other tertiary work at Obafemi Awolowo University’s Institute of African Studies (Táíwò Reference Táíwò2021a: 310; Crowder Reference Crowder1969), the Ife Primary Education Research Project (Fafunwa et al. Reference Fafunwa, Macauley and Sokoya1989), and other initiatives across Africa (Ouane and Glanz Reference Ouane and Glanz2010). In L-22, the SiY founder mentions Fafunwa et al. (Reference Fafunwa, Macauley and Sokoya1989) as one of the foundational bases for the project. In Figure 2, AESTYL also mentions that their motivation is Fafunwa’s work. These two projects, then, are good examples of projects that have a clear connection with MTE.

Problem-UAR has two sides, the public side and the classroom side, both of which need to be addressed to solve this problem. Most STEM-for-the-public projects do not have any plan for the classroom side of Problem-UAR. With a lack of clear pedagogical plans or awareness of pioneering MTE efforts, STEM-for-the-public projects do not come close to an ultimate solution to Problem-UAR. In the remainder of this article, I describe these STEM-for-the-public projects in detail as a way to chart the course for a new kind of scholarship on this phenomenon. I note that STEM-for-the-public projects have the potential to create much needed dialogue and integration (even if informal) between modern STEM and the IKSs of wholesale-origin African societies.

STEM-for-the-public projects

This section provides a digital ethnography of STEM-for-the-public projects, highlighting modes of operation, topics, linguistic approaches, engagement, impacts, and pushbacks.

Modes of operation

STEM-for-the-public projects adopt three modes of operation: the one-person mode, the association mode and the collaboration mode. The contents of STEM-for-the-public projects that operate in the one-person mode are created by just one person. From writing, filming, recording, editing and proofreading to production, everything is handled by the creator of the project. The one-person mode is characterized by some kind of expert-to-public flow, where the creator of the project relays information to their followers without much input from the audience. Projects operating in this mode include IAA, FYSF, SiH, MDU, MiYL, MYL, CBG, WT, Arojinle and PEY.

The association mode is an operation mode in which more people are involved. However, although more people are involved, each article is entirely produced by single individuals. AESTYL is the only project that operates in this mode. The page includes a lot of articles that do not have author identifiers (and articles with unknown authors; see L-15), but since the majority of the author-identified articles are written by the founder of the association, one could assume that authorless articles are written by him too. It seems, then, that the purpose of the page is to provide a platform for members to publicize content. Like the one-person mode, the association mode, as exemplified by AESTYL, is also characterized by expert-to-public flow, where the public has limited opportunity to contribute to knowledge reproduction.

The collaboration mode is similar to the association mode in that more people are involved, but it differs in the sense that much of the content that is published is jointly produced by those involved. SiY is the only STEM-for-the-public project that has adopted this mode. The Facebook page and the webpage of the project have videos and articles, where four types of roles are often identified: ‘writer’, ‘reviewer’, ‘voice’ and ‘producer’. What this means is that, in the content that is produced, the writer is often different from the peer reviewer. While the writer and reviewer roles are always taken by different individuals, the same person may perform the roles of writer, voice (i.e. voiceover in videos) and producer, or the roles of reviewer, voice and producer. It is worth noting that, for SiY, the founder is always the producer. Although SiY is characterized by a unidirectional expert-to-public flow, as in the one-person and association modes, it sometimes exhibits some form of bidirectional expert-public flow, where both the project and the public work to reproduce STEM knowledge in Yoruba. The page occasionally asks the public what they would call a particular STEM concept in Yoruba (see L-21, for example).

Although I have identified three modes of operation here, I note that it is possible for a project to exhibit more than one of these modes. For instance, while SiY operates initially within the collaboration mode, it has increasingly become a one-man show. In recent times, the founder has simultaneously functioned as writer, voice and producer. The AESTYL page also exhibits the one-person mode in those instances where all the activities are performed by its president. So, while all of the projects exhibit the one-person mode of operation to various degrees, none of them operates purely in the association or collaboration modes. This means that all of these projects are driven by passionate single individuals who may work alone, provide a platform for others to produce, or work with others to jointly produce. Without these individuals, a project might collapse.

STEM topics

So, within the short time over which they have emerged, how far have the existing STEM-for-the-public projects gone in their quest to indigenize modern STEM? We can classify the projects into two broad categories according to the STEM topics that they have indigenized so far. These are discipline-focused projects and general-focus projects. Discipline-focused projects explain topics that are relevant only to one area of STEM. Examples include MiYL, IAA and MYL, all of which explain only mathematical topics; CBG, whose focus is on cellular biology; WT, which focuses only on technology; and PEY, which explains only psychological concepts.

General-focus STEM-for-the-public projects are not restricted in their scope. They touch on various topics in STEM depending on the interests of their audience. AESTYL, SiY, Arojinle and SiH are examples of general-focus projects. In Table 2, I provide representative samples of the STEM areas that have been explained so far in each language; if a project has at least an article or a video that talks about a given STEM area, the project is indicated as having covered that area. While a project could have extensive content in one area, it is also common for the same project to have scant materials in other areas. For example, CBG has extensive content on biology but only one video on space science. To show that a given project has at least two posts in a particular STEM area, I have put the area in bold in Table 2.

Table 2. STEM topics.

In explaining these topics, the projects sometimes draw on local oral cultures (e.g. proverbs) and indigenous knowledge (e.g. traditional medicine). For example, while explaining gravity, SiY often draws on the Yoruba proverb laalaa to roke ilẹ lo n bọ (‘whatever goes up comes down’), and the producer of Arojinle, who also always includes proverbs to contextualize descriptions of animal behaviour, sometimes includes details of how an animal or insect is used in traditional medicine and spirituality so that his descriptions are not simply an exact regurgitation of what is contained in modern zoology but a synthesis of the modern and the indigenous.

While STEM topics are the main concern of these projects, they also post about other topics. MDU posts about Igbo folktales for children and an Igbo physics textbook that was recently published, while IAA has a lot of videos that explain the Igbo language, people and culture. AESTYL posts about things like Yoruba sudoku, the importance of studying STEM in Yoruba, topics of national interest in Nigeria, notable Yoruba people and scholars, non-STEM stories, STEM poems, advocacy for the spread of STEM in Yoruba, AESTYL’s media appearances, STEM-in-Yoruba competition announcements, and the goals of the project. FYSF posts about subjects including advocacy for the spread of STEM in Yoruba, advertisements, calls for paid advertisement, and STEM-in-Yoruba competition announcements. SiY posts about classroom demonstrations of science being taught to students in Yoruba, demonstrations of STEM instructional materials, how other languages become the language of science, locally made technologies, STEM materials being donated to schools, inquiries from the public on what to call a STEM concept in Yoruba, exhibitions of other people’s STEM-for-the-public projects, SiY’s mission, followers’ feedback, SiY’s media appearances, STEM-in-Yoruba competition announcements, and advocacy for the spread of STEM in Yoruba.

As well as maths topics, MiYL posts about things such as their appreciation of followers’ donations, discussions of economics topics in Yoruba, and the project’s media appearances, while MYL posts about R programming language and follower appreciation. Arojinle also posts comedy skits, paid advertisements, motivational speeches and birthday eulogies, and debunks hoaxes about animal behaviour. Apart from discussions of data science, WO makes posts about careers in tech, tech-enabled industries, personal tours and follower appreciation. Although PEY has posted only eight times on psychology, it too has two posts on follower appreciation. CBG posts about subjects including Christmas celebrations, celebrations of STEM-related international days, subscriber and general appreciation, goals of the project, and the project being shortlisted for an award. WT, too, posts about things like the history of the internet, mobile apps, computers, how to create a website, tech in Senegal and writing a doctoral thesis. Finally, SiH has one post celebrating its followers.

So what do these other things that the projects post about tell us about this new form of STEM knowledge reproduction in Africa? First, we see that these projects serve as a platform for MTE advocacy and the promotion of African languages and cultures. Pages such as AESTYL, MDU and SiY are constantly reminding people of why children need to learn in their first language. AESTYL, in particular, has made posts explicitly calling for the adoption of MTE in the area of STEM, while highlighting the benefit of this approach to the Yoruba people. SiY has published videos of actual science classes being taught in Yoruba, which generated responses from followers showing that they have now realized how effective MTE in STEM can be in arousing students’ curiosity and increasing their willingness to participate in class discussions.

Second, it is noteworthy that these projects are capable of generating income for those who wish to make money in their effort to indigenize modern STEM. For instance, Arojinle runs adverts for people, sometimes as independent posts and sometimes in the middle of STEM-for-the-public videos. FYSF runs advertisements and even invites people to advertise on the page. The possibility that STEM-for-the-public projects can generate income is good news for wholesale-origin societies since it means that the value of their language as linguistic capital (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1991) can increase in the linguistic marketplace in which it finds itself. According to Bourdieu (ibid.: 18), linguistic marketplaces (or contexts in which languages are used) endow linguistic products (that is, language varieties) with certain values so that some products are more valued than others. The typical scenario in wholesale-origin societies is that the language of modern STEM (a language of foreign origin), which often also doubles as the language of government, education and trade, is largely more valued than the indigenous languages. For example, in the linguistic marketplace of Yoruba-speaking states in Nigeria, English is valued, on balance, more highly than Yoruba, since it is the language of education, government, trade, modern STEM, etc. In other words, English is more valued because, as linguistic capital, it can be converted to ‘economic capital (i.e. material wealth in the form of money, stocks and shares, property, etc.)’ (ibid.: 14). That is, knowledge of how to use English appropriately in appropriate contexts can be the basis for earning income that helps secure material wealth. Now that Yoruba is used in STEM-for-the-public projects that can bring in income (similar to how its use in traditional media and publications of all genres has significantly increased its status), it follows that the value associated with Yoruba in this linguistic marketplace has increased, even if only slightly (see Appendix B). By also holding science competitions in local languages, the projects have the capacity to imbue local languages with more value as linguistic capital. Recently, SiY conducted the Yoruba Onímọ̀-ìjìnlẹ̀ science competition, which awarded about US$230 to winners. Competitions like this have the potential to increase the value that is attached to local languages in the linguistic marketplaces of wholesale-origin societies.

Third, we have also seen that these projects can be a platform for social commentary. We see this in the case of AESTYL and WT. AESTYL has several posts commenting on various issues of national interest in Nigeria. For example, when the government of Nigeria announced in 2022 that local languages would be used throughout primary education, AESTYL issued a press release pointing out certain issues that the government needed to address. WT, too, has several episodes that explore the connection between nation building and technology in Senegal. Fourth, the project also provides an avenue to showcase local ingenuity. SiY has videos highlighting technologies that were locally produced in Africa. Finally, the projects also provide a platform for the social actors involved to appreciate others and celebrate their own achievements.

Linguistic approaches

These projects do not indigenize the language of modern STEM in the same way. We can recognize at least three linguistic approaches that are adopted. These are the bilingual approach, the translanguaging approach and the monolingual approach. Bilingualism is the use of two languages in context. Projects that adopt the bilingual approach make use of two languages: the local language and a foreign language, such as English or French. For a project to qualify as adopting the bilingual approach, one of three things needs to be satisfied: (1) the project makes use of code-switching; (2) it uses subtitles in a language that is different from the spoken language; or (3) it publishes articles and/or videos in two languages interchangeably.

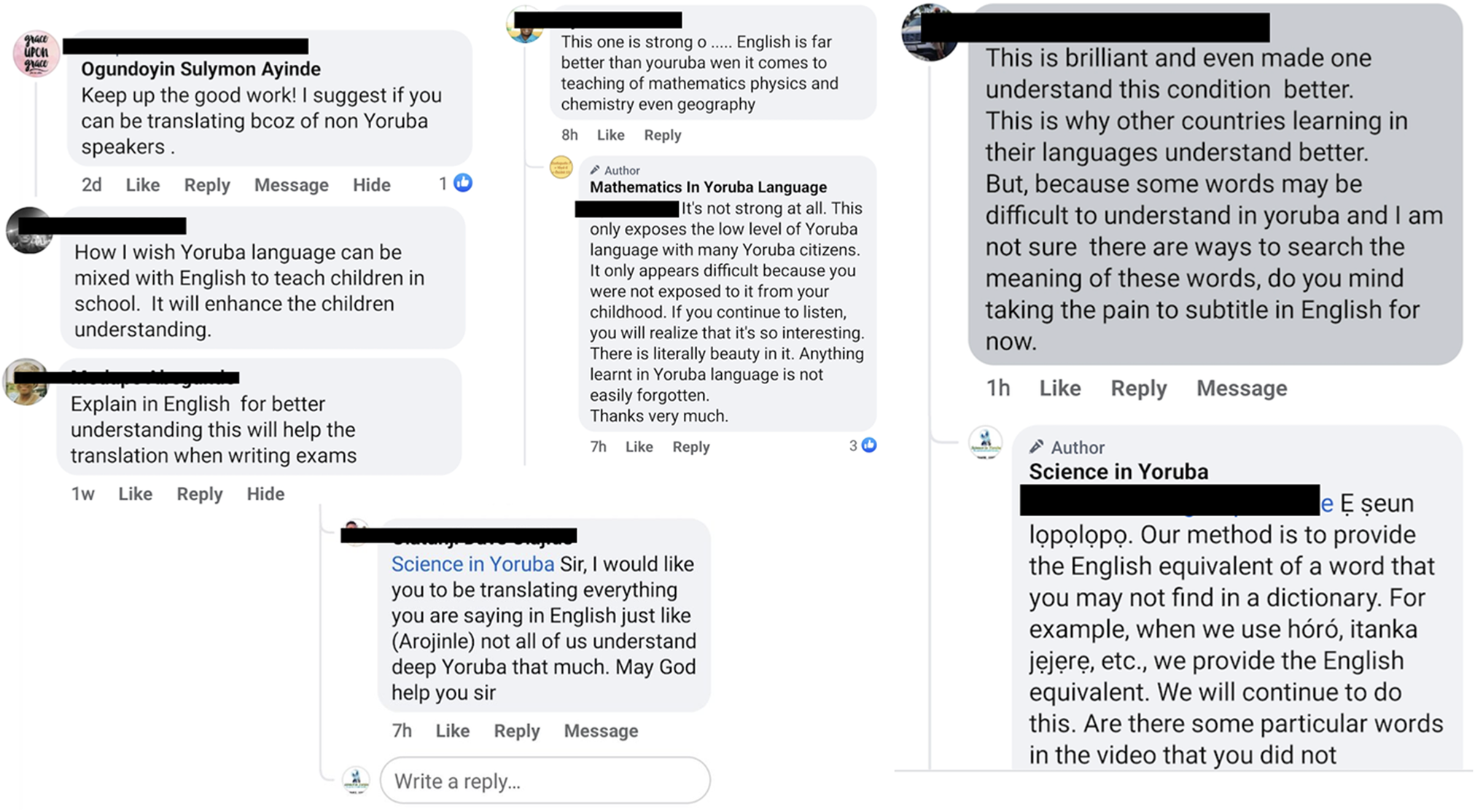

AESTYL is an example of a project that adopts the bilingual approach. The project falls into this category for two reasons. First, it publishes some articles written in Yoruba and some others written in English. Second, it publishes articles that are written in both Yoruba and English. In the article in L-16, the first paragraph is written in English. This is followed by a paragraph written in Yoruba, which in turn is followed by a paragraph written in English, and so on. Arojinle, CBG and WO also adopt the bilingual approach. Although Yoruba and Gikuyu/Swahili are spoken in the STEM videos produced by these projects, the videos are subtitled in English. This seems like an attempt to reach a larger audience compared with the use of a local language only. A look at the comments sections of posts by Arojinle and SiY, for example, reveals that people sometimes request that the producers provide English subtitles on two grounds: to help the content reach more people (including those who do not speak Yoruba) and to help people whose Yoruba proficiency is low (see Appendix E). Arojinle even sometimes code-switches briefly into English in some of its videos. MYL also adopts a form of bilingual approach where it makes posts in Yoruba and sometimes in English.

Translanguaging occurs when a speaker uses their linguistic repertoire without regard for the artificial social and political boundaries that exist among named languages (Wei Reference Wei2018: 19). The translanguaging approach to language frames languages as resources used according to one’s situational needs. Sometimes, a person holds a conversation in one language, and then they come to a point where they have to express a concept but do not know how the concept is expressed in the current language. If this person expresses the concept in the second language and then moves back to the original language of the conversation, they would be said to have engaged in translanguaging. They would be said to have taken full control of their linguistic repertoire, deploying the linguistic resources at their disposal as the need arises. This is precisely what happens with projects that adopt the translanguaging approach. They explain STEM topics in the local language but use STEM terms from English or French when such terms are not available yet in the local language. Since they do not assume their audiences’ familiarity with English or French technical terms, they use the local language to explain their meanings. Unlike projects adopting the monolingual approach, which I discuss below, translanguaging STEM-for-the-public projects do not seek to find local equivalents for STEM terms that are not available yet in the local language. They use the local language as long as it has the words and phrases that are needed. When it does not, they take words and phrases from either English or French without any phonological adaptation. Examples include MYL, PEY, SiH, CBG and WT.

Monolingualism is the use of one language in social contexts. Projects that adopt the monolingual approach use only the local language in their explanations. They find existing words in the local language and recombine and recontextualize them to express concepts for which the local language does not have words. When they take words from a foreign language like English, these are phonologically adapted so that they fit the native grammar of the target language. MiYL, MDU, FYSF, IAA and SiY are the projects that stick to this approach. Although AESTYL, WO and Arojinle adopt a bilingual approach, as observed above, they also use the monolingual approach in various ways. In its articles written entirely in Yoruba, AESTYL exhibits the monolingual approach: it recombines and recontextualizes existing Yoruba words, and it nativizes words imported from English. While WO and Arojinle mainly adopt the bilingual approach in that their spoken explanations are in Yoruba and their written explanations are in English, they exhibit the monolingual approach in their spoken explanations for the simple reason that they too recombine and recontextualize existing Yoruba words and nativize foreign ones. Also, note that both adopt the translanguaging approach. They sometimes fall back on English without attempting to nativize. Table 3 highlights which of the projects fall into which linguistic approach.

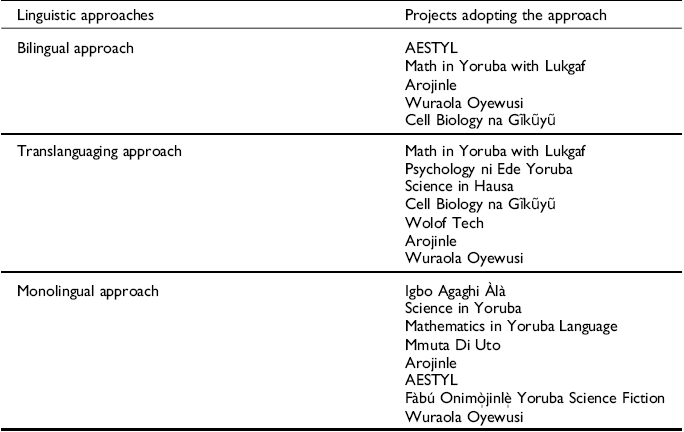

Table 3. Linguistic approaches.

One generalization in Table 3 is that some projects adopt more than one of these approaches while some projects stick to one approach. Arojinle and WO adopt all three approaches. CBG and MYL adopt both the bilingual and translanguaging approaches. AESTYL adopts both the bilingual and monolingual approaches. Projects that stick to only one approach include PEY and WT (the translanguaging approach) and SiY, MDU, IAA and MiYL (the monolingual approach). The categorization in Table 3 is based only on the content of the STEM posts produced by these projects. A totally different picture emerges when one examines the titles that accompany these posts. All of these projects use a foreign language in their titles. While projects such as AESTYL, SiY, MiYL, SiH, CBG and PEY mostly combine Yoruba, Gikuyu/Swahili, Igbo or Hausa with English in their titles, WO, Arojinle, WT and MYL adopt the monolingual approach of using titles constructed in English or French for the most part. What is clear is that these foreign languages are still indispensable for STEM-for-the-public projects, especially in advertising the work they do to a public that has become so entangled with those languages. This can also be seen in the names of some of these projects. This implies that languages of foreign origin are part of the resources the projects mobilize in their quest to advance indigenous languages.

Modality and audience engagement

Modality is an important factor in measuring the effectiveness of STEM-for-the-public projects. The projects adopt one or two of three types of modality: (1) the written–pictorial frame; (2) the audio frame; and (3) the audiovisual frame. Projects such as SiH, AESTYL and FYSF that adopt only the written–pictorial frame publish only short articles that are accompanied by images. WT, which uses only voice, is the only project that has adopted the audio frame so far. All other projects (SiY, MDU, IAA, MiYL, MYL, Arojinle, WO, CBG and PEY), which communicate with their audience using videos, adopt the audiovisual frame. However, SiY combines the audiovisual frame with the written–pictorial frame. It publishes videos as well as image-accompanied articles on its website.

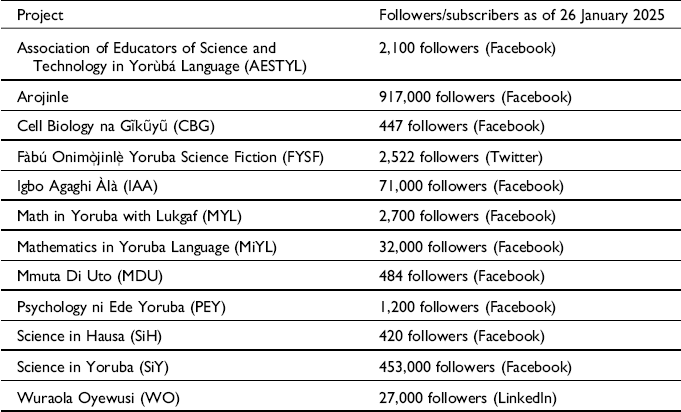

For the most part, the kind of modality adopted by a STEM-for-the-public project seems to correlate with how much engagement it is able to generate. In the following paragraphs, I consider the audience sizes of these projects in terms of followership and subscription. WT is not included in this discussion because Podchaser.com, where its episodes are published, does not provide engagement data.

Table 4 shows the audience size for each of the projects. Where a project is present on more than one social media platform, the platform with the highest number of followers/subscribers is included in the table. Projects adopting the audiovisual frame appear to have more audience members than those adopting the written–pictorial frame. Based on the number of followers/subscribers, we can recognize two distinct groups of projects: Group 1 with a high audience size (with 27,000 or more followers) and Group 2 with a low audience size (fewer than 3,000 followers/subscribers). All four projects in Group 1 (Arojinle, IAA, MiYL and SiY) primarily adopt the audiovisual frame, while all of the projects adopting the written–pictorial frame fall within Group 2. This generalization seems to suggest that the audiovisual frame might be more effective than the written–pictorial frame.

Table 4. Audience size.

The question, however, is why does it matter to measure how much engagement these projects attract? First, STEM-for-the-public projects can be conceived as a form of social movement. One way to establish them as a force for social change is to determine how much attention people pay to them. With posts made by some of these projects generating upwards of 32,000 reactions, 2,200 comments and 11,000 shares, this social movement might be in a position to influence cultural productions in wholesale-origin societies. Second, by examining post engagement, we are able to make generalizations that can help guide similar projects in the future. Learning from the generalization that the audiovisual frame is more effective at reaching more people on social media platforms than the written–pictorial frame, a future project might consider adopting the former and not the latter. Third, doing this also allows for cross-cultural comparisons. STEM-for-the-public projects are developing in wholesale-origin societies outside Africa (e.g. Native American and aboriginal wholesale-origin societies), although they are not yet as robust as the projects discussed in this article (see L-28 and L-29). Comparisons can be drawn between these societies and those of Africa. However, such a comparison is beyond the scope of this article.

Impacts and pushbacks

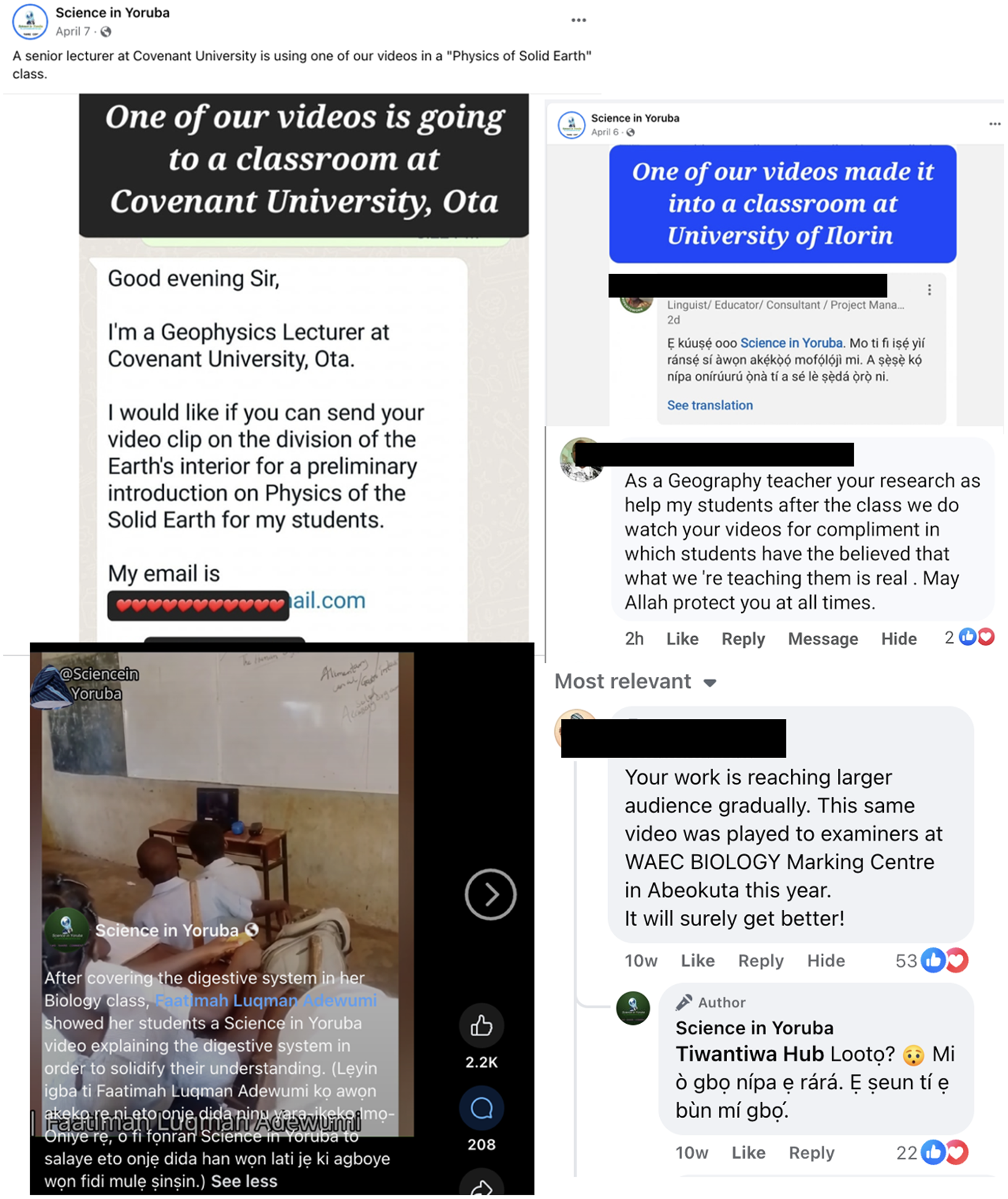

Using a variety of linguistic approaches, operating in different modes, covering various STEM topics and adopting different modality frames, the projects appear to have made the following impacts. First, it appears that STEM-for-the-public projects may have the potential to ultimately make their way into the classroom and influence instructional practices, even if informally. Figure 3 shows how two videos made by SiY became part of classroom instruction (as illustrations) at two universities in Nigeria. Figure 3 also shows that high school teachers used SiY videos to complement their instruction in geography and biology classes.

Figure 3. The use of STEM-for-the-public content in classrooms.

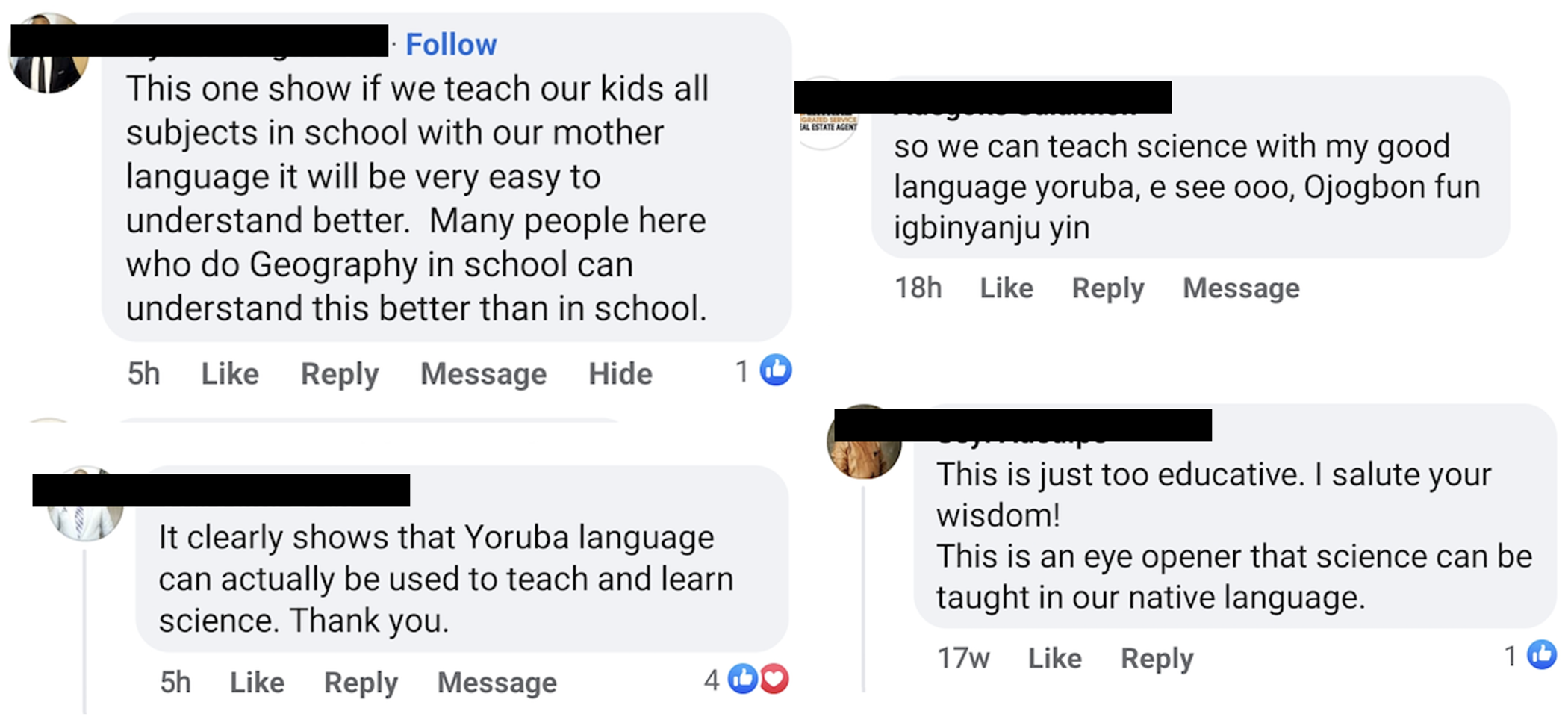

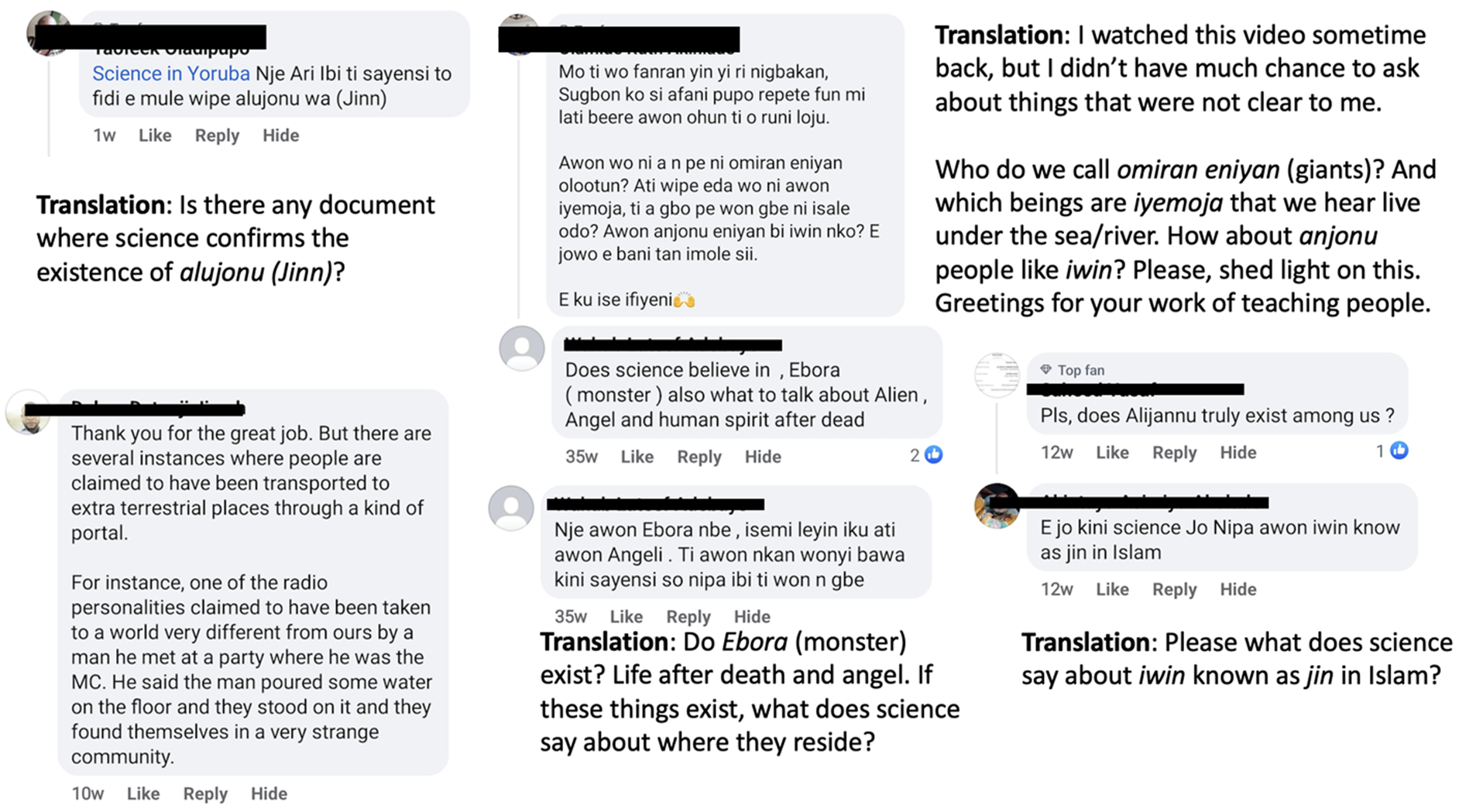

Second, it seems that STEM-for-the-public projects may be able to combat the erroneous belief that African languages are incapable of expressing modern STEM (see Figure 4). Third, the comments that these projects have generated show that they may have increased some people’s confidence and sense of identity in their wholesale-origin society (Appendix B). They may also have increased accessibility to modern STEM for people who otherwise lack access to this body of knowledge (Appendix C). They seem to inspire dialogue between modern STEM and the local IKS. The comments in Appendix D show conversations asking about the position of modern STEM on iwin, ẹbọra, yemọja and àlùjọ̀nú (invisible beings), which are said to exist in a different dimension within the Yoruba IKS. Questions like these have the potential to lead to deeper conversations about the connection between IKSs and string theory in physics. The projects have also started to generate conversations around the localization of modern STEM. The post in L-18 shows that WO’s videos are part of the conversation about how to express ‘artificial intelligence’ in Yoruba. It also seems that these projects have the potential to make their way into different institutions in these societies. For instance, MYL’s videos were recently made available to high school students at a local library in Iseyin, Oyo State (L-19). Also, in April 2023, Ekiti State TV started broadcasting MYL’s videos (L-20).

Figure 4. Comments showing the belief that local languages are capable of expressing modern STEM concepts.

Despite some positive reception for these projects, we see comments that show that there are some people in these societies for whom the local language is still inadequate. Appendix E shows comments indicating that some people still believe in the expressive superiority of English when it comes to modern STEM. STEM-for-the-public projects attempt to solve Problem-UAR, but despite some impacts that can be recognized, as noted above, it does not appear that STEM-for-the-public projects in their current forms are the ultimate solution to this problem. First, the presence of these projects on social media remains relatively insignificant. If we consider the number of followers/subscribers that they have so far against the number of people available online in those wholesale-origin societies, we see that they have reached only a small percentage of these online populations. Consider Nigeria, for example. About 80.7 million Nigerians are on the internet as of March 2022 (Adepetun Reference Adepetun2022). Followers of all STEM-for-the-public projects in Nigeria combined are a little above 1.5 million (as of January 2025), and that does not account for follower overlap. Second, these projects remain largely on social media. In fact, only one of them has made it to a local library and a local TV station. These projects then exclude offline publics. Even if their followers increase exponentially, a huge percentage of the population in these societies (who are not on social media) will still be excluded. For example, according to an estimate (Adepetun Reference Adepetun2022), 81 per cent of Nigerians lack meaningful internet connectivity as of 2022. STEM-for-the-public projects are still in their infancy. It will be interesting to study their reach and their contribution to the resolution of Problem-UAR in future work.

Conclusion

In this article, I have provided the first documentation of recent efforts seeking to indigenize STEM not necessarily for the African classroom but for the general African public. Because these STEM-for-the-public projects have consistently emerged in different African contexts since 2016, it seems that more of them will appear in African digital spaces in the near future. I situated these projects within the indigenization literature and showed that they are an attempt to solve Problem-UAR. Based on a digital ethnography, I provided some initial frameworks to conceptualize them in terms of their modes of operation, linguistic approaches and modalities. I explored some recognizable impacts they have made so far, highlighting that they seem to increase STEM accessibility, enhance the sense of identity, informally complement classroom instruction, facilitate discussions about the indigenization of STEM, inspire dialogue between modern STEM and IKSs, and are incorporated in some offline spaces. Despite these impacts, I showed that these projects still largely depend on colonial languages to market their products and that some followers still believe in the expressive superiority of colonial languages. I also note that STEM-for-the-public projects in their current form may not be the ultimate solution to Problem-UAR, since, on balance, they have excluded offline publics, have not significantly addressed the classroom side of Problem-UAR, and have reached only a significantly small portion of their target online populations. Future research will be in a much better position to test the generalizations in this article, show how these projects have evolved over time, and provide more ethnographic assessments of their impacts in wholesale-origin societies.

Appendix A: Links

-

• L-2 https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=1855689081399234&set=pb.100063998140822.-2207520000

-

• L-7 https://www.podchaser.com/podcasts/wolof-tech-1319516/episodes/recent

-

• L-8 https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC8OqmTZ-kemmMtu7LBYdpXQ

-

• L-14 https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100083532407319

-

• L-15 https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=579068237562784&set=a.483736083762667

-

• L-16 https://www.facebook.com/AESTYL/photos/pb.100063788371284.-2207520000./4533393390010438/?type=3

-

• L-17 https://twitter.com/FIjinle

-

• L-19 https://www.facebook.com/Lukgaf/videos/1353292678582127

-

• L-21 https://www.facebook.com/scienceinYoruba/videos/606016561000720

-

• L-28 https://language.cherokee.org/posters/science-and-health/?term=&page=2&pageSize=7

Appendix B: Comments showing increased sense of identity

Appendix C: Comments showing increased STEM accessibility

Appendix D: Comments showing dialogue between modern STEM and an IKS

Appendix E: Comments showing the belief that English is still indispensable in STEM-for-the-public projects

Taofeeq Adebayo is an Assistant Professor of Linguistics at California State University, San Bernardino. Adebayo leads the ‘Science in Yoruba’ project, an ongoing community-engaged research project that seeks to make modern STEM accessible in the Yoruba language for both the classroom and the general public.