In 1981, Thomas (Reference Thomas1981) developed the Monitor Valley Key to formalize Great Basin projectile point types, and he grouped the types within five projectile point series, two of which he defined at the time. The projectile point series concept was first applied by Heizer and Baumhoff (Reference Heizer and Baumhoff1961), later amplified by Lanning (Reference Lanning1963), then applied to Great Basin projectile point types by Hester and Heizer (Reference Hester and Heizer1973), and finalized into a chronology by Thomas (Reference Thomas1981).

It was also during this period that researchers in California and the Great Basin developed a binomial naming system for projectile point types known as the Berkeley typological system (Thomas Reference Thomas1981), which included a primary designator and a morphological form label. The first term refers to a primary site type name (e.g., Rose Spring site) or a generalized location name (e.g., Desert, Eastgate, Elko, Northern, etc.), with the second designator referring to some aspect of the morphological shape of the point—that is, corner-notched, side-notched, and others (Hester Reference Hester1973:24).

Underlying this binomial naming scheme was a shared, but incorrect, archaeological assumption that different morphological point forms recovered from the same excavation levels should share the same primary label. Archaeologists at the time tacitly assumed that prehistoric knappers at a site created multiple variant morphological forms that could be encompassed by a single primary label. Points that shared a primary label could be directly grouped into related series (sensu Lanning Reference Lanning1963) of point types, such as Desert Series, Elko Series, and Rose Spring Series.

Point types with different morphologies could be members of a series simply by virtue of sharing a primary designator, thereby generating a named projectile point series. According to Hester and Heizer (Reference Hester and Heizer1973), even though variant morphological forms are included within each projectile point series—for example, Little Lake Series, Elko Series, Rose Spring Series—the series are themselves time sensitive. Therefore, point types sharing the same primary designator share the same stratigraphic contexts, time spans, and geographic distributions.

Monitor Valley Key

Thomas (Reference Thomas1981) formalized Lanning's series concept into a chronological sequence for the central Great Basin by creating the Monitor Valley Key. Thomas's goal in creating this key was to identify types that are “morphological types that are found consistently to be associated with a particular span of time in a given area” (Thomas Reference Thomas1981:13–14); he noted, “Time markers must be bounded in space as well as time” (Thomas Reference Thomas1981:24).

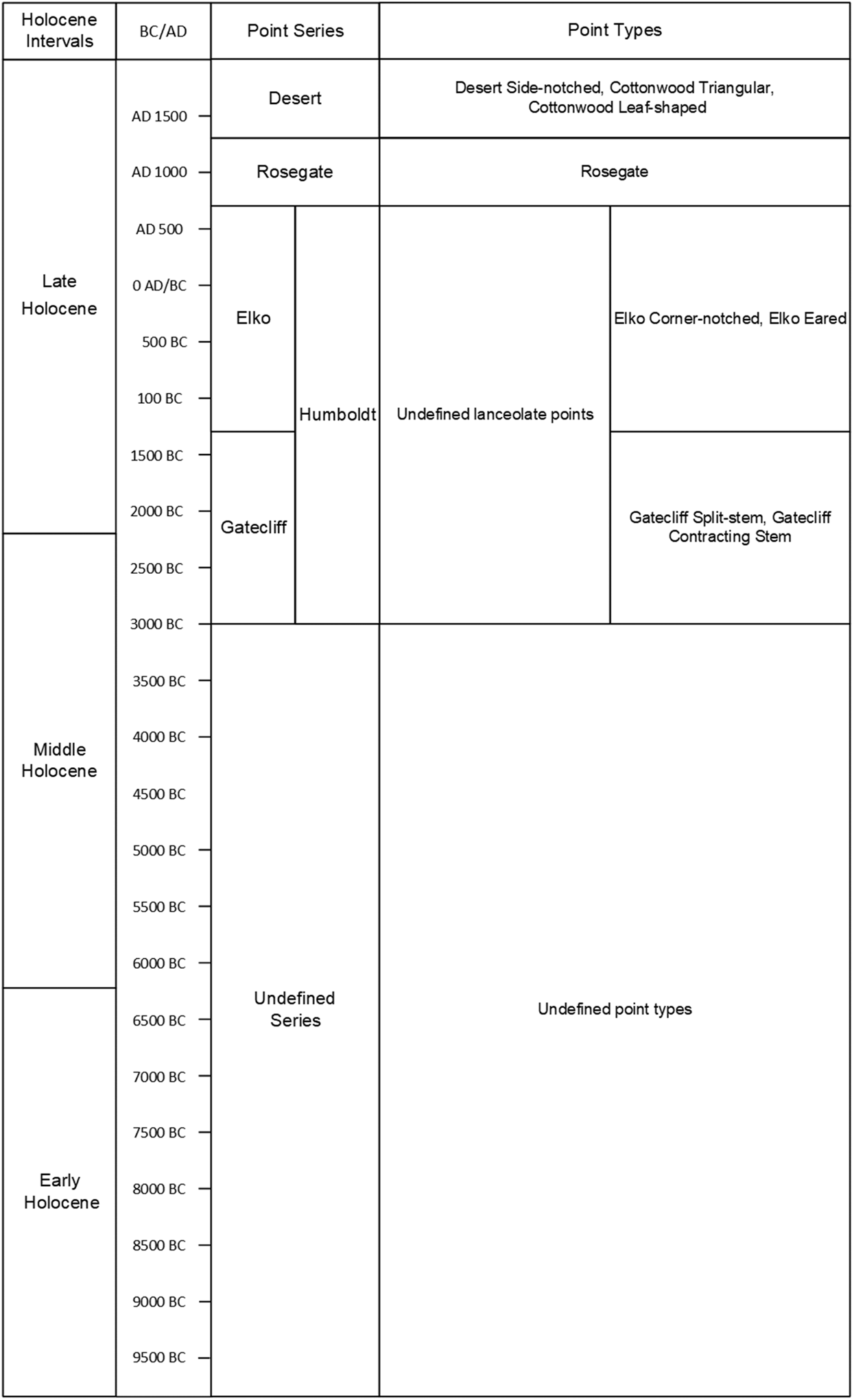

By using various cut points and parameters, the classification key formally defined 10 morphologically variant point types that were combined into five different chronological series. Thomas (Reference Thomas1981) assigned a discrete time span to each of the five series: the Desert Series (post-AD 1300), Elko Series (1300 BC–AD 700), Humboldt Series (ca. 3000 BC–AD 700), and two newly defined series within the key—the Gatecliff Series (3000–1300 BC) and the Rosegate Series (AD 700–1300). These series formed the projectile point chronology for the central Great Basin (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The 1981 projectile point series chronology and associated point types for the Great Basin, derived from Thomas (Reference Thomas1981). The Large Side-notched point type was not assigned a time span by Thomas, nor was it included in any point series.

Thomas (Reference Thomas1981:24) stated that the five series were sufficient to characterize over 95% of the nearly 1,000 projectile points in his initial analysis of points from the Monitor Valley in Nevada. Although Thomas stated that the key was only applicable to the Monitor Valley area, he used radiocarbon-dated points from sites located outside of the Monitor Valley and central Great Basin—including sites from the Colorado Plateau—to confirm his types and create the date ranges for the five series, implicitly suggesting that the key and the series were applicable to well beyond the central Great Basin (see Thomas Reference Thomas1981:Figure 12).

These five projectile point series—Desert, Elko, Gatecliff, Humboldt, and Rosegate—are still widely applied in the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau, and some of the series are treated as composite point types (e.g., Bettinger and Eerkens Reference Bettinger and Eerkens1997; Bischoff and Allison Reference Bischoff and Allison2020; Holmer Reference Holmer, Condie and Fowler1986; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Barker, Hattori, Raymond and Goebel2013). By assigning a specific time span to each series, Thomas and others who use the series chronology accept that all variant point types in the same series are contemporaneous and presumably geographically and culturally coincident.

However, extensive excavations throughout the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau coupled with the widespread application of radiocarbon dating since 1981 have conclusively demonstrated that various morphological point types sharing the same primary series designators (e.g., Gatecliff points, Elko points, Rosegate points) do not always share either consistent temporal spans or coincident geographic distributions. Below, Thomas's series are discussed demonstrating (1) the nomenclature problems, (2) inconsistencies between the assigned time spans of the series relative to individual point types, and (3) the differential geographic distributions of individual point types within some of the series.

Gatecliff Series (3000–1300 BC)

Based on excavations in the Monitor Valley, Thomas (Reference Thomas1981) created a new projectile point series, the Gatecliff Series. It includes a previously undefined bifurcate stem point—the Gatecliff Split Stem point—now generally accepted as a diagnostic temporal type. Thomas labeled it the Gatecliff Split Stem point type to differentiate it from temporally earlier Pinto or Little Lake series bifurcate stemmed points (Holmer Reference Holmer, Condie and Fowler1986:98).

Because of the stratigraphic co-occurrence of the Gatecliff Split Stem points with Gypsum points at Gatecliff Shelter (Thomas Reference Thomas1983), Thomas relabeled the Gypsum Contracting Stem point as the Gatecliff Contracting Stem point so as to create a series that included two different point types sharing the same primary designator. The relabeling of the stemmed dart points (Gypsum points) from Gatecliff Shelter as Gatecliff Contracting Stem points was a contravention of the Berkeley typology nomenclature. Gypsum points had already been defined in the Berkeley typology based on Gypsum Cave, the type site where this point type was first described (Harrington Reference Harrington1933). The relabeling of a Gypsum point as a Gatecliff Contracting Stem point does not validate its shared membership within the defined time span or restricted geographic distribution of the newly defined Gatecliff Series.

Despite Thomas's attempt to rename the Gypsum point as Gatecliff Contracting Stem to support a new series, the Gypsum point and the Gatecliff Split Stem point do not share either the same temporal span or the same stratigraphic contexts across the Great Basin, the Colorado Plateau, or elsewhere. The Gatecliff Series was assigned a time range of 3000–1300 BC, but the Gypsum point has a much more restricted time span of 2360–720 cal BC (Coulam Reference Coulam2022) and is much more widespread across the West than Gatecliff Split Stem points are. Holmer (Reference Holmer, Condie and Fowler1986:105) notes that Gypsum points are found far beyond the central Great Basin, including the Colorado Plateau and portions of the southern Basin and Range Province (Coulam Reference Coulam2022). The Gatecliff Split Stem point appears to be restricted to central Great Basin (e.g., Gatecliff Shelter [Thomas Reference Thomas1983] and Hidden Cave [Thomas Reference Thomas1985]) and is not found in association with Gypsum points on the Colorado Plateau (e.g., Sudden Shelter [Jennings et al. Reference Jennings, Schroedl and Holmer1980], Cowboy Cave [Jennings Reference Jennings1980]) or elsewhere in the southern Basin and Range Province (Miller and Graves Reference Miller, Graves and Maloof2019). As defined, the Gatecliff Series does not include point types that share a consistent time span nor are they geographically coincident.

Humboldt Series (ca. 3000 BC–AD 700)

Because the variables in the Monitor Valley Key cannot differentiate distinct lanceolate points from the region, Thomas (Reference Thomas1981) describes the Humboldt Series as a catch-all category of unnotched, lanceolate, concave-base projectile points from the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau. He states, “The Humboldt series is a “residual” category, . . . This definition operates strictly at the series level” (Thomas Reference Thomas1981:17). According to the Monitor Valley Key, any unnotched lanceolate point from the Great Basin or Colorado Plateau can only be assigned to the Humboldt Series. Named lanceolate point types, such as Humboldt Concave Base A, Humboldt Concave Base B, Humboldt Basal-notched, are “undefined” according to Thomas and are not differentiated by the Monitor Valley Key; they are only included within the Humboldt Series by reference.

Holmer (Reference Holmer, Condie and Fowler1986:101) demonstrates conclusively that morphologically distinct lanceolate point types have differential temporal spans in the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau, undermining the use of the Humboldt Series label as a temporal marker. The fact that morphologically similar lanceolate point types (as classified by the Monitor Valley Key) share the same series label does not a priori demonstrate that they share the same geographic distribution or temporal span of 3000 BC–AD 700.

Elko Series (1300 BC–AD 700)

The Elko Series was the first identified projectile point series in the Great Basin (Heizer and Baumhoff Reference Heizer and Baumhoff1961:135), and it continues to be widely referenced today. Large corner-notched points are now recognized as the most common dart point across the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau after the end of the Terminal Pleistocene / Early Holocene. Whereas various other styles of dart points such as side-notched, stemmed, and lanceolate points arose and declined in popularity and frequency in the past (Holmer Reference Holmer, Condie and Fowler1986), the large corner-notched points labeled Elko Corner-notched points functioned as the generic or default stone dart point for thousands of years until the introduction of the bow and arrow.

The Elko Series includes the eponymous Elko Corner-notched point as well as the Elko Eared, Elko Contracting Stem, and later, the Elko Side-notched point (Baumhoff and Clewlow Reference Baumhoff and Clewlow1968), but these point types do not all share the same geographic distribution or time span. The Elko Side-notched point is geographically restricted to northeastern Great Basin (Beck Reference Beck1995:Figure 4) and the Colorado Plateau (Holmer Reference Holmer, Condie and Fowler1986). Elko Eared points are more widespread, followed by large corner-notched dart points, which are found over much of the West and often identified as Elko points.

Holmer (Reference Holmer, Condie and Fowler1986:101–104) discusses in detail the differential time spans of Elko Series points. There is a time differential for the Elko Corner-notched type in central Great Basin, the eastern Great Basin, and northern Colorado Plateau in which he contrasts a “long” versus “short” series chronology for Elko points. At stratified caves and rockshelters in the eastern Great Basin and Colorado Plateau, Elko Corner-notched and some Elko Side-notched points exhibit a “long” series chronology with three distinct temporal florescences beginning in the Early Archaic dating as early as 6000 BC and continuing to as late as AD 500 or possibly later (Holmer Reference Holmer, Condie and Fowler1986). In the central Great Basin, the “short” Elko Series prevails, where Elko Corner-notched points only date from about 1300 BC to AD 700 (Thomas Reference Thomas1981). Consequently, Elko series points do not share the same time span across the Great Basin or the West (Holmer Reference Holmer, Condie and Fowler1986).

The lack of an Early Archaic Elko florescence in the central Great Basin is not surprising. Excavations at several stratified sites in the region—including Gatecliff Shelter (Thomas Reference Thomas1983), South Fork Shelter (Baumhoff and Clewlow Reference Baumhoff and Clewlow1968), and Pie Creek Shelter (McGuire et al. Reference McGuire, Delacorte and Carpenter2004)—demonstrated that substantial prehistoric occupation in this region began no earlier than 4600 BC in the Middle Holocene compared to Terminal Pleistocene / Early Holocene occupations present at a number of stratified and open sites in the eastern Great Basin, such as Bonneville Estates Rockshelter (Hockett and Goebel Reference Hockett and Goebel2019), Danger Cave (Jennings Reference Jennings1957), Hogup Cave (Aikens Reference Aikens1970), and Old River Bed (Field Reference Field2014). The limited occupational sequence from the central Great Basin, which lacks evidence of Terminal Pleistocene / Early Holocene and Early Archaic occupations, cannot be used to develop a projectile point chronology that is applicable to the entire Great Basin proper and beyond.

Although Thomas (Reference Thomas1981:21) states that Elko Corner-notched and Elko Eared points share the same time span, Elko Series points are assigned an ending date of AD 700 in the central Great Basin, whereas Elko Eared projectile points cease being manufactured after about 500 BC in the region (Schroedl Reference Schroedl1995:49). Whereas the Elko Eared point type is a significant temporal marker, the Elko Series as a whole is not.

In summary, given the temporal variations discussed here, the Elko Series is probably the least temporally diagnostic of any projectile point series proposed by early researchers. In fact, the inability of the Elko Series to function as a temporal marker in the Great Basin was recognized as early as 1973 by Hester and Heizer, who stated, “In fact, the data from Hogup [Cave] suggest that the Elko corner-notched may be completely useless as a time-marker” (Reference Hester and Heizer1973:6). The inclusion of multiple temporally and geographically differentiated point types within this series demonstrates the lack of utility of the Elko Series as a temporal marker.

Rosegate Series (AD 700–1300)

Large stone dart points, mostly corner-notched dart points, dominated projectile point assemblages for thousands of years in the Great Basin until the diffusion of the bow and arrow in the region around AD 700 (Thomas Reference Thomas1981). Even though the propulsive mechanism of the atlatl and bow are different (Whittaker Reference Whittaker, Iovita and Sano2016), arrow projectiles are just diminutive analogs of larger dart projectiles, tipped with proportionately smaller stone arrow points (e.g., Fenenga Reference Fenenga1953; Shott Reference Shott1997; Thomas Reference Thomas1978). As with generic corner-notched dart points, once the bow was sufficiently refined to replace the atlatl as a lethal hunting weapon, corner-notched arrow points became the generic arrow point form, known today to compose a significant portion of arrow point assemblages across the West (Eckles Reference Eckles2022; Geib and Bungart Reference Geib and Bungart1989; Holmer Reference Holmer, Condie and Fowler1986; Holmer and Weder Reference Holmer, Weder and Madsen1980; Jennings Reference Jennings1980).

One of the earliest primary labels applied to arrow points in the Great Basin region was Rose Spring, after the Rose Spring site (CA-INY-372), first reported by Lanning (Reference Lanning1963). It has been widely applied across the West (Justice Reference Justice2002), not just in the Great Basin (Heizer and Baumhoff Reference Heizer and Baumhoff1961) but also in the Mojave Desert (Sutton Reference Sutton2017), the Snake River Basin in Idaho (Webster Reference Webster1980), the Colorado Plateau (Holmer and Weder Reference Holmer, Weder and Madsen1980; Reed and Metcalf Reference Reed and Metcalf1999), the Upper Colorado River Basin (Eckles Reference Eckles2022), and further north to at least the Big Horn Basin in Wyoming (Husted and Edgar Reference Husted and Edgar2002). The Rose Spring label is not restricted to corner-notched arrow points in southern California or the Great Basin.

An arrow point type that is geographically restricted to the Great Basin is the Eastgate Expanding Stem point (Hamilton et al. Reference Hamilton, Buchanan and Walker2019; Spencer Reference Spencer2015). Spencer (Reference Spencer2015) describes the modal or “classic” Eastgate Expanding Stem point as often having a slightly convex base with symmetrical deep narrow parallel-sided basal notches. Basal notching on these points results in a distinctive square-barbed shoulder unlike any other arrow point type in the West. The primary distinctive characteristic of Eastgate points is not its unique plan view morphology but its thickness—or rather, its thinness. Classic Eastgate points are thin or extremely thin, often only 2.5 mm thick or less (Spencer Reference Spencer2015). Woods (Reference Woods2015) notes that the planned production of an archetypal Eastgate point with square-barbed shoulders was established early in the preform stage by creating a thin finished preform prior to the notching. Thicker preforms unsuitable for narrow basal notching followed a secondary reduction trajectory that usually resulted in a generic corner-notched form (La Fond Reference La Fond and Schroedl1995; Woods Reference Woods2015), a form often referred to as Rose Spring points. Basal-notched arrow points, such as modal Eastgate points, are morphologically distinguishable from modal corner-notched arrow points.

Heizer and Baumhoff (Reference Heizer and Baumhoff1961) recognized the morphological distinction between basal-notched and corner-notched arrow points at Wagon Jack Shelter and assigned the Eastgate label to the basal-notched points and the Rose Spring label to the corner-notched points; however, they failed to follow the conventions of the Berkeley binomial naming system. Heizer and Baumhoff deviated from the standard nomenclature procedures by incorrectly labeling the corner-notched points at Wagon Jack Shelter as Rose Spring Corner-notched points (Heizer and Baumhoff Reference Heizer and Baumhoff1961:129).

Under the Berkeley naming conventions, stratigraphically contemporaneous morphological point forms (e.g., arrow points) from a type site must share the same primary designator. All variant morphological forms of arrows at this type site should carry the same primary designator—Eastgate. It is not clear why Heizer and Baumhoff chose to label the corner-notched points from this type site as Rose Spring Corner-notched points rather than Eastgate Corner-notched points. Even though the morphological differences between the corner-notched points and basal-notched points at Wagon Jack Shelter resulted from different reduction trajectories, Heizer and Baumhoff should have retained the same primary Eastgate label for these two arrow point types.

Had Heizer and Baumhoff correctly applied the Berkeley nomenclature conventions to the arrow point assemblage at Wagon Jack Shelter, the resulting binomially named arrow points from the Late Archaic at this type site would be labeled Eastgate Expanding Stem, Eastgate Split Stem, and Eastgate Corner-notched, all within the Eastgate Series. Thomas (Reference Thomas1981) failed to indicate that Heizer and Baumhoff had mistakenly identified the corner-notched points at the site as Rose Spring points. Instead, Thomas created the new Rosegate Series, a combination of the Rose Spring and Eastgate types. He stated, “The types obviously grade into one another, and it is extremely difficult in practice to separate the two consistently; . . . There is also no known difference in time range between the two types. As a result, the Eastgate and Rose Spring types are merely morphological designations, and I suggest that they be combined into a single temporal indicator” (Thomas Reference Thomas1981:19). At the time, the Rose Springs Series and Eastgate Series were recognized as two separate series (Hester and Heizer Reference Hester and Heizer1973).

Thomas's assertions that Eastgate Series points and Rose Spring Series points shared a common time span, had a similar geographic distribution, and represent a morphological continuum are incorrect: there is no archaeological basis for a hybrid Rosegate point type. The inability of the classification variables of the Monitor Valley Key to distinguish the square-barbed shoulder of an Eastgate Expanding Stem point (a basal-notched point) from the shoulder of a corner-notched point is insufficient justification for the creation of a new hybrid type.Footnote 1

Although the nomenclature issue of Eastgate versus Rose Spring versus Rosegate may have not been significant 40+ years ago in the Great Basin, it has had a significant impact on understanding the diffusion of the bow and arrow across the West. In the central Great Basin, the Eastgate Expanding Stem / Split Stem point and associated corner-notched points (labeled as Rose Spring points) date no earlier than AD 650 (Bettinger and Eerkens Reference Bettinger and Eerkens1997; Hildebrandt et al. Reference Hildebrandt, McGuire, King, Ruby and Young2016; Hockett and Goebel Reference Hockett and Goebel2019). Outside of the central Great Basin, the bow and arrow arrived much earlier, but the continued use of both the Rose Spring and Rosegate Series labels throughout the region has obscured archaeologists’ understanding of the spread of bow and arrow technology throughout the West.

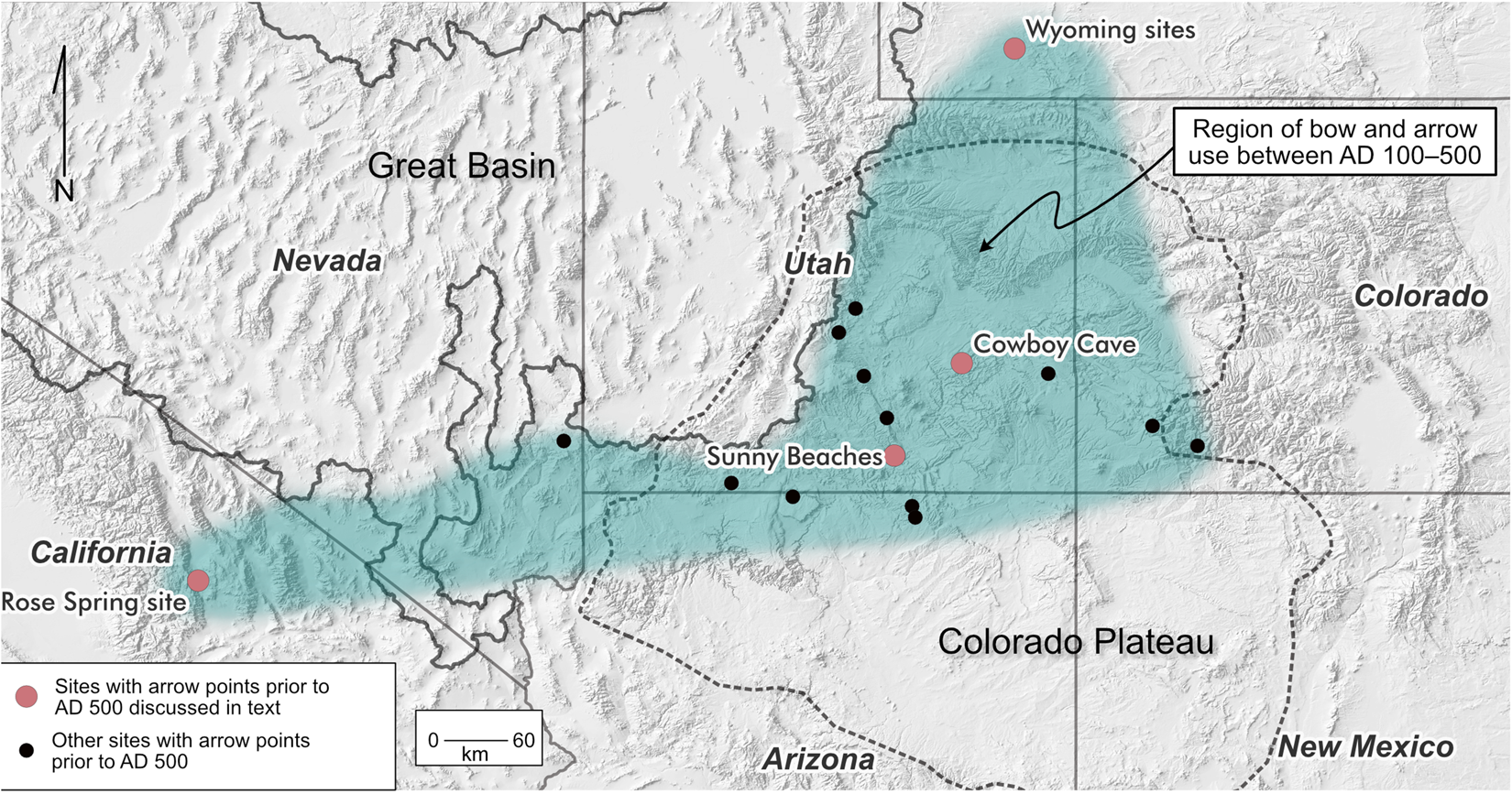

On the Colorado Plateau and beyond, various morphological forms of arrow-sized points have been reported at sites dating earlier than AD 500. For example, at Cowboy Cave on the Colorado Plateau, arrow points, originally identified as Rose Spring Corner-notched points, date to as early as AD 100–250 (Jennings Reference Jennings1980; Schroedl and Coulam Reference Schroedl and Coulam1994). Geib and Bungart (Reference Geib and Bungart1989) identify several arrow-sized points at the Sunny Beaches site in south central Utah dating to about AD 160. Eckles (Reference Eckles2022) reviewed various arrow points from sites in southwestern Wyoming, some of which date to about AD 310. At the Rose Spring type site in the Mojave Desert in California, Rose Spring points may date to about AD 490 (Garfinkel Reference Garfinkel2007:45; Yohe Reference Yohe1998:28).

Because of the limited use of the bow and arrow during this early period (pre–AD 500), arrow point assemblages at these sites usually only include a few points. A review of arrow points from these early sites demonstrates that the first bow hunters were experimenting with a variety of arrow point forms, including corner-notched, stemmed, side-notched, triangular, and irregularly shaped arrow points. Although arrow points from this time period are often referred to as Rose Spring points or Rose Spring variants, assigning formal type labels to arrow points before about AD 500 is unwarranted.

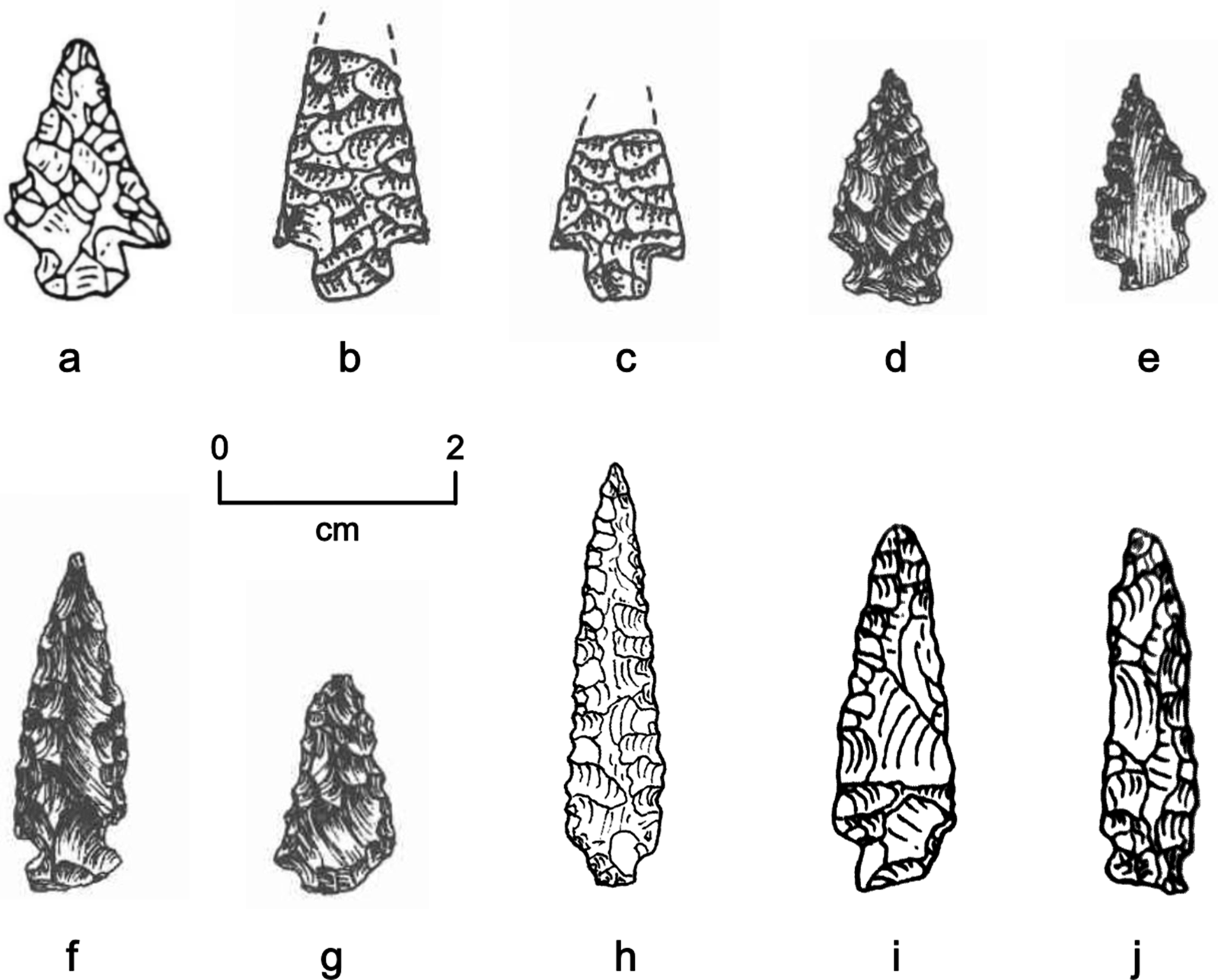

Figure 2 depicts the range of morphological variation of arrow points from several sites with dates earlier than AD 400 on the Colorado Plateau. During this early period, these morphologically variable points are best identified simply as Early Arrow (EA) points rather than any formal, named types. Figure 3 shows that bow and arrow use was widespread in the West—from the Colorado Plateau to the Mojave Desert—decades and perhaps centuries before the bow and arrow diffused into the Great Basin after AD 650. Therefore, the first temporally diagnostic arrow point in the Great Basin is the Eastgate Expanding Stem point, which was possibly introduced from maize horticulturalists in the eastern Great Basin (see Bischoff and Allison Reference Bischoff and Allison2020).

Figure 2. Examples of morphological variation of Early Arrow (EA) points from the northern Colorado Plateau dating prior to AD 350: (a) site 42GA456 (Janetski et al. Reference Janetski, Kreutzer, Talbot, Richens and Baker2005); (b and c) Sunny Beaches (Geib and Bungart Reference Geib and Bungart1989); (d–g) Sandy Ridge (Richens and Talbot Reference Richens and Talbot1989); (h–i) Mountainview site (Geib Reference Geib2011).

Figure 3. Map of the geographic extent of sites with arrow-sized projectile points in the West prior to AD 500. Sites discussed in the text are identified on the map.

The melding of two typologically distinct arrow point types—a basal-notched point and a corner-notched point—with different temporal spans and geographic distributions under a single Rosegate label has hampered the understanding of the transition from the atlatl and dart to the bow and arrow in the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau for the past 40-plus years. The Rosegate label has been misapplied not just in the Great Basin but also on the eastern Colorado Plateau (e.g., Diederichs Reference Diederichs2020; Reed and Metcalf Reference Reed and Metcalf1999). Ironically, the Eastgate portion of the Rosegate portmanteau has no relevance on the Colorado Plateau. As early as 1980, Holmer and Weder (Reference Holmer, Weder and Madsen1980) specifically noted that Eastgate points are not found on the Colorado Plateau and are generally restricted to the Great Basin proper.

Desert Series (AD 1300–Historic Period)

Thomas's Desert Series is another amalgamation of two previously defined series—the Desert Side-notched Series and the Cottonwood Series as distinguished by Hester and Heizer (Reference Hester and Heizer1973). A small side-notched arrow point, informally labeled a Shoshone point, was recognized as a protohistoric arrow point type in the 1950s in the Great Basin and surrounding regions. Baumhoff (Reference Baumhoff1957) was the first to apply the binomial label of Desert Side-notched to these small arrow points at the Payne Cave in California. Two years later, several subtypes of the Desert Side-notched points were defined by Baumhoff and Byrne (Reference Baumhoff and Byrne1959), who formally recognized the utility of Desert Side-notched points as late prehistoric to protohistoric time markers.

In addition to defining the Rose Spring Series at the Rose Spring site, Lanning (Reference Lanning1963) also defined the Cottonwood Series based on a reanalysis of arrow points from the Cottonwood Creek site (CA-INY-2), a Paiute village site in Owens Valley (Riddell Reference Riddell1951). The Cottonwood Series consisted of two varieties of unnotched arrow points: one with a triangular form (Cottonwood Triangular) and the other with a leaf-shaped form (Cottonwood Leaf-shaped).

Thomas (Reference Thomas1981) redefined the Desert Series to include the Desert Side-notched, the Cottonwood Triangular, and the Cottonwood Leaf-shaped arrow points. In contrast to the chronologically earlier series—where the Gypsum point was renamed with the primary label of Gatecliff, and the Rosegate Series label was applied to an artificial combination of Eastgate points and Rose Spring points—Thomas did not require all members of the Desert Series to share the same primary label or designator.

Whereas the Desert Side-notched point variants and the Cottonwood Triangular points frequently co-occur in archaeological assemblages in the Great Basin, the Cottonwood Leaf-shaped point is notably absent. It is not clear why Thomas chose to include the Cottonwood Leaf-shaped point as a representative type within the Desert Series. This point was not reported from Gatecliff Shelter, the site that provided the projectile point assemblage for developing the Monitor Valley Key, nor has it been reported from elsewhere in the central Great Basin (e.g., Elston and Budy Reference Elston and Budy1990; McGuire et al. Reference McGuire, Delacorte and Carpenter2004). The Cottonwood Leaf-shaped arrow point, one of 10 point types distinguished by the Monitor Valley Key, appears to be an idiosyncratic morphological form found only in the vicinity of the Cottonwood Creek site in southern California.

Summary

The projectile point series presented by Thomas represent artificial groupings that have no archaeologically intepretive value. The projectile series concept relies on an underlying false premise that knappers throughout the past simultaneously created multiple morphological forms that shared specific time spans and restricted geographic distributions, thereby requiring these point types to be grouped together under the series rubric.

The series concept, subsuming variant point forms under a common series designator (e.g., Desert, Elko, Gatecliff, Humboldt, and Rosegate), obscures rather than clarifies the differences in the chronological and geographic ranges of individual point types that compose each series. Also, since 1981, some of the identified series have been transformed from aggregations of individual points types; now, these series are treated as if they were a single composite point type (i.e., the Humboldt type, the Rosegate type, etc.). However, a named projectile point series cannot be a taxonomic equivalent of an individual point type, which, by definition, represents a single discrete morphological form associated with a known time span and known geographic distribution.

The development of the Berkeley binomial naming system for projectile points was an advancement as a mnemonic aid for the names of different projectile point types. The Berkeley system, however, had the unfortunate side effect of—a priori—implying geographic, temporal, and cultural associations that may or may not exist among point types sharing the same primary designator (such as Elko or Gatecliff, or as discussed in the Rosegate example above).

An earlier generation of Great Basin archaeologists recognized the potential for unintended but imputed cultural, temporal, or geographic associations by using type site-named point types, which explains why these researchers used alphanumeric type designators to forestall implying any cultural, geographic, or temporal associations among different point types (e.g., Heizer and Krieger Reference Heizer and Krieger1956; Jennings Reference Jennings1957; Shutler and Shutler Reference Shutler and Shutler1963). Using series designations only magnifies any implied cultural, temporal, or geographic associations among unrelated morphological point forms within a series.

Heizer, Hester, Lanning, Thomas, and other researchers have failed to explain what particular benefits accrue from analyzing projectile point types within a chronological framework of named series rather than simply analyzing and comparing the chronology and geographic distribution of each named morphological type separately. Some archaeologists might suggest that earlier generations of researchers who developed and used the projectile point series concept understood there would be some variations in the temporal spans of some of the individual types within a series and that these series point types might or might not share similar geographic distributions. But this raises a critical question: what is the utility of grouping different point types into a named series if the individual types within a series do not share at least one common element, such as geographic range, temporal span, morphological form, or cultural association?

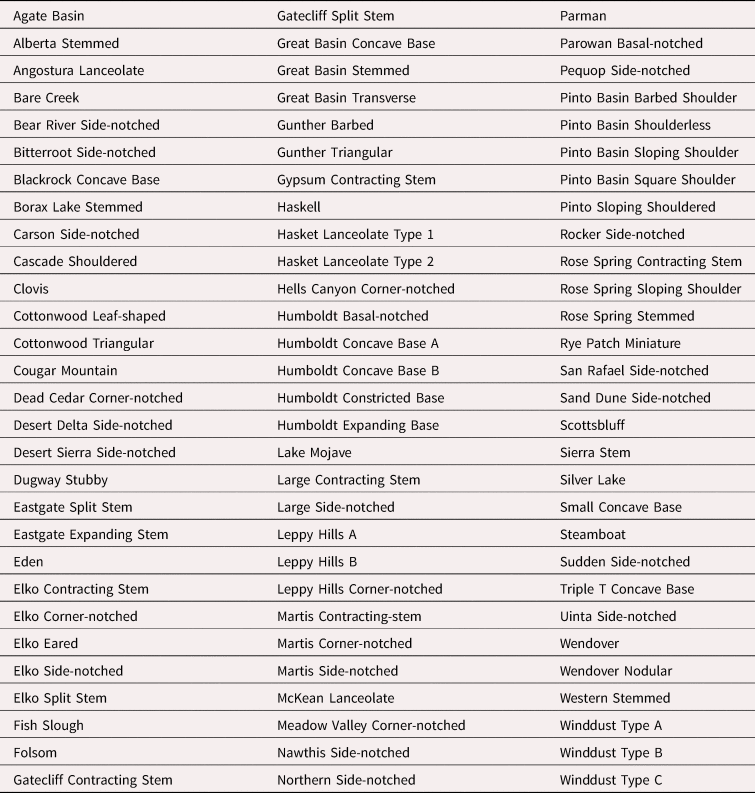

The current chronological scheme of projectile point series is simplistic, incomplete, and incorrect. Projectile point typology in the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau has become much more temporally and geographically complex since the development of the Monitor Valley Key in 1981 (e.g., Beck Reference Beck1995; Bettinger et al. Reference Bettinger, O'Connell and Thomas1991; Bischoff and Allison Reference Bischoff and Allison2020; Holmer Reference Holmer, Condie and Fowler1986; Hockett Reference Hockett1995; Hockett and Goebel Reference Hockett and Goebel2019; Hockett and Spidell Reference Hockett and Spidell2022; O'Connell and Inoway Reference O'Connell and Inoway1994; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Barker, Hattori, Raymond and Goebel2013, etc.). Only 10 projectile point types were identified within the Monitor Valley Key among the five defined series. Today, based on a review of past and current archaeological literature, there are almost 90 named projectile point types, including dart points, arrows points, and Paleoindian points from across the Great Basin and surrounding regions (Table 1). Yet, the Monitor Valley Key has no provisions for incorporating these other point types into the projectile point chronology for the Great Basin or the adjacent Colorado Plateau.

Table 1. Alphabetical List of Named Projectile Types Previously Identified in the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau

The continued use of the series concept and the series chronology detracts from the important tasks of clarifying the morphological variation, temporal span, and geographic distribution of the numerous individual projectile point types now known to occur within these regions. It is time to abandon the projectile point series concept and develop chronological sequences based on analyses of differential forms, time spans, and geographic distributions of individual point types across the West.

Acknowledgments

A number of reviewers have provided critical comments on several earlier drafts of this article, which have greatly improved the discussions presented here.

Funding Statement

This research received no specific grant funding form any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this analysis are available in published research by cited authors.

Competing Interests

The author declares none.