INTRODUCTION

The understanding of early Aegean sealing practices and glyptic development in the Cyclades during the Early Bronze Age (EBA) has been limited by the scarcity of existing evidence. Major finds of direct object sealings from mainland Greece, such as those from Lerna (Heath Reference Heath1958; Wiencke Reference Wiencke1969; Reference Wiencke and Matz1974), Geraki in Lakonia (Weingarten et al. Reference Weingarten, Crouwel, Prent and Vogelsang-Eastwood1999; Reference Weingarten, MacVeagh Thorne, Prent and Crouwel2011) and Petri in Corinthia (Kostoula Reference Kostoula2000), along with others (cf. Krzyszkowska Reference Krzyszkowska2005, 36–56; Wilson Reference Wilson, Macdonald, Hatzaki and Andreou2015, 169), highlight the advanced nature of sealing practices on the mainland, particularlry when compared to those of EBA II Crete.Footnote 1

In contrast, the Cyclades and the wider Aegean present a more fragmented picture, with scarce and sporadic evidence of seals, sealings and stamp seal impressions on pottery and other artefacts (Fig. 1). This raises the question of whether this low visibility is due to gaps in archaeological knowledge or reflects diverse practices in the Cyclades, as compared to mainland Greece (Angelopoulou Reference Angelopoulou2005; Krzyszkowska Reference Krzyszkowska2005, 52; Wilson Reference Wilson, Macdonald, Hatzaki and Andreou2015, 172–4; Vlachopoulos Reference Vlachopoulos, Vlachou and Gadolou2017, 551–2). A limited number of seals have been discovered in various excavated contexts, such as Skarkos on Ios (Marthari Reference Marthari, Meller, Gronenborn and Risch2018, 187–90, fig. 34), Markiani on Amorgos (CMS V Supp. 3, nos 43–4; Angelopoulou Reference Angelopoulou, Marangou, Renfrew, Doumas and Gavalas2006),Footnote 2 Keros-DhaskalioFootnote 3 and Vathy on Astipalea (Vlachopoulos Reference Vlachopoulos, Vlachou and Gadolou2017, 547, figs 5–7), which indicate a wider spread of seal use in the Aegean. Additional sporadic examples have been reported from Naxos.Footnote 4 Specific evidence of Cycladic sealings is documented at Agia Irini Period III on Keos (CMS V.2, no. 479; Wilson Reference Wilson1999, 166, no. SF-409, pls 39 and 102), Markiani on Amorgos (CMS V Supp. 3.1, no. 46; Angelopoulou Reference Angelopoulou, Marangou, Renfrew, Doumas and Gavalas2006, 221–2) and the Cave of Zas on Naxos (CMS V Supp. 1B, nos 106–9; Zachos and Dousougli Reference Zachos, Dousougli, Brodie, Doole, Gavalas and Renfrew2008), as well as at Palamari on Skyros (Parlama Reference Parlama, Simantoni-Bournia, Lemou, Mendoni and Kourou2007, 36, fig. 18:2). These findings provide evidence of seal use in the Cyclades and the Aegean during the EBA II period and underscore the importance of chance preservation in understanding seal practices.

Fig. 1. Early Bronze Age sites with seals, sealings and stamp seal impressions mentioned in the text (K. Sbonias).

A separate category of finds includes seal impressions stamped before firing on the rims of fixed or portable hearths, vessels, handles of transport and storage jars and weights. The majority of these impressions come from Agia Irini on Keos in Period II contexts.Footnote 5 Additional examples of stamped pottery have been found at Chalandriani and Kastri on Syros (CMS I Supp., nos 171–2; CMS XI, no. 121), Keros (Tzavella et al. Reference Tzavella, Renfrew, Gavalas, Ugarković, Rowan, Dixon, Haas-Lebegyev, Renfrew, Nymo, Karali, Georgakopoulou, Renfrew, Philaniotou, Bordie, Gavalas and Boyd2015, 310–11, figs 10.13, 10.14) and Markiani on Amorgos (CMS V Supp. 3.1, nos 45, 47, 48). Stamped weights are known from Skarkos on Ios (CMS V Supp. 3.1, nos 169–74; Marthari Reference Marthari, Meller, Gronenborn and Risch2018, 189–91, figs 35–40; Krzyszkowska Reference Krzyszkowska and Ulanowskaforthcoming). These examples indicate the occasional stamping of vessels in the Cyclades and mainland GreeceFootnote 6 in the EBA II period, unlike Crete, where this practice appears in the late Prepalatial period and particularly in the Protopalatial period.Footnote 7 The role and function of these impressions – whether decorative or related to some purposes of identification and control – remain under discussion (cf. Krzyszkowska Reference Krzyszkowska2005, 52–6; Aruz Reference Aruz2008, 23–5; Wilson Reference Wilson, Macdonald, Hatzaki and Andreou2015, 172–4; Marthari Reference Marthari, Meller, Gronenborn and Risch2018, 191–3). Nevertheless, they offer valuable insights into the glyptic repertoire encountered on the Aegean islands and allow for comparisons with materials from other contexts.

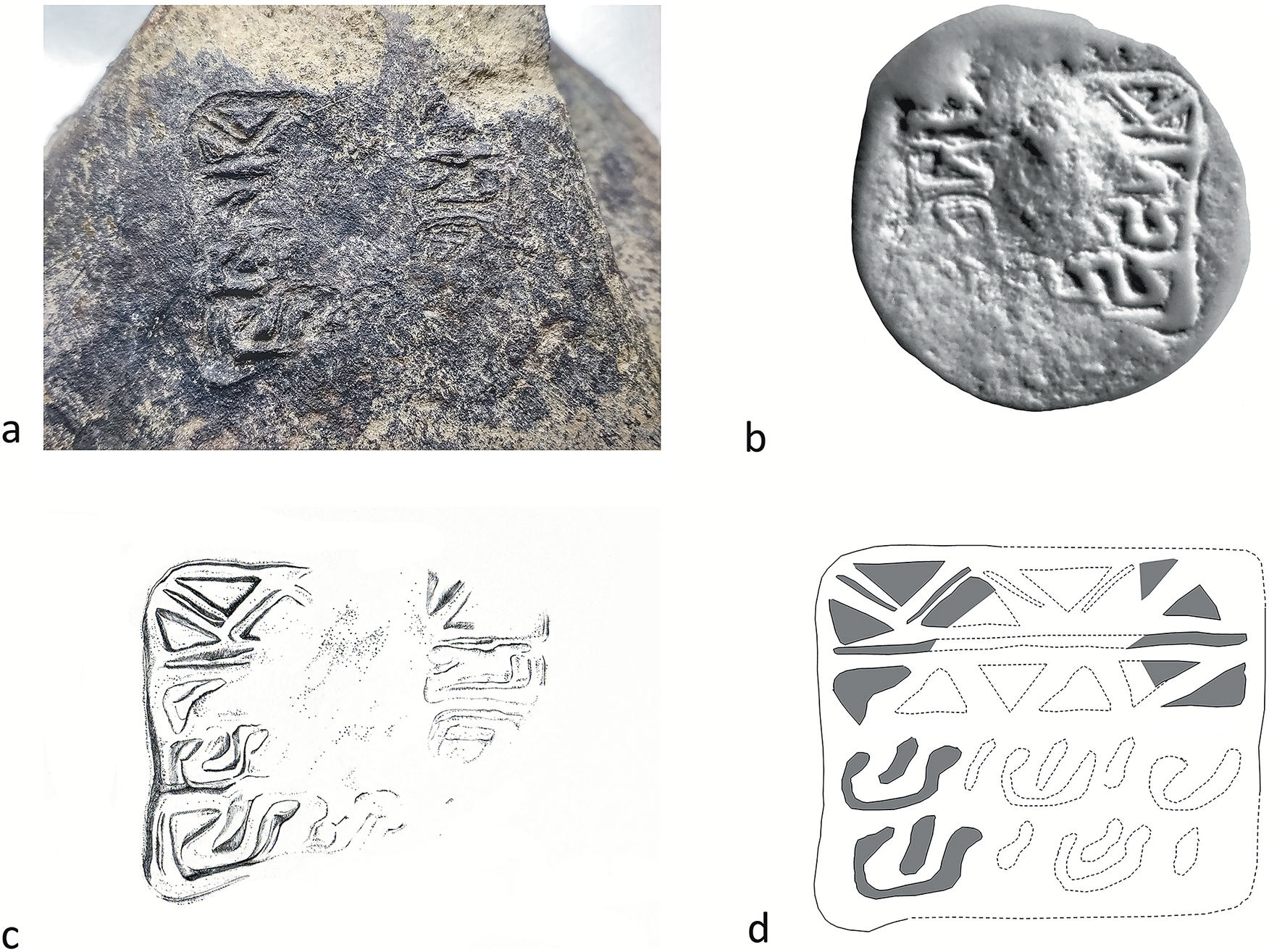

The excavation of the settlement site of Koimisis on Therasia has significantly advanced our understanding of materials from excavated Cycladic settlement contexts. A handle from a large, thick-walled storage jar was unearthed in a stratified Early Cycladic (EC) II context (Fig. 2). The preserved dimensions of the sherd under study (body and handle) are 10.6 x 10.3 cm, and the thickness of the body wall ranges from 0.6 to 0.9 cm. Its fabric is inconsistent with the local geology, suggesting it may have been imported (see below). The handle bears two distinct seal impressions. The first seal impression (THS.1), stamped on the upper part of the handle, features signs arranged in a linear sequence, creating the impression of an inscription (Fig. 2a). The second impression (THS.2), located on the lower end of the handle, displays a design consistent with the broader Cycladic and Aegean glyptic tradition (Fig. 2b). This study analyses the context of the find and examines the seal impressions in terms of iconography, style and potential seal shapes.Footnote 8 Additionally, it discusses the character, associations and meaning of the signs, alongside the broader context and possible origin of the vase, based on the petrographic analysis of the pottery fragment.

Fig. 2. Vertical strap handle with seal impressions THS.1 and THS.2 (drawing by V. Papazikou).

ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONTEXT OF THE SEAL-IMPRESSED HANDLE

The settlement site of Koimisis occupies the top and upper terraces of a hill at the south-east end of present-day Therasia. Systematic excavations on the southern and south-eastern hillsides have revealed the remains of an EC settlement, inhabited from the transitional EC I/II period (Kampos phase) throughout the EBA, and, to a lesser extent, until the end of the Middle Cycladic (MC) period (Sbonias et al. Reference Sbonias, Tzachili, Efstathiou, Palyvou, Athanasiou, Farinetti and Moullou2020; Reference Sbonias, Tzachili, Efstathiou, Palyvou, Athanasiou, Farinetti, Syrigou, Sbonias and Tzachili2021; Reference Sbonias, Tzachili, Athanasiou, Farinetti, Gkatzogia, Kordatzaki, Mavromati, Palyvou, Zavadil and Driessenforthcoming). The deposits from the Minoan eruption (Late Cycladic I/Late Minoan IA) partially sealed the remains of the abandoned site, contributing to the good preservation of its architecture.

The seal-impressed handle was discovered in Room X4, just above floor level, near a threshold connecting Rooms X3 and X4 (Fig. 3). These rooms were constructed against the internal east side of a thick external wall, which likely served both a retaining and defensive function. A staircase passing through the northern excavated section of the wall provided access to the hilltop. Spaces X3 and X4 form a cohesive unit that dates to the EC II period. To establish the chronological context of the seal-impressed handle, we should note that the area underwent a deliberate infilling after a destructive event in the later part of the EC II period, likely caused by the collapse of the interior face of the eastern wall of Room X3. Following this event, the area, which contains no MC material, was filled with stones and remained packed throughout the MC phase of the site. This stone packing functioned as a kind of supporting wall for the apsidal building X2 (Fig. 3), which contained pottery dating to the MC period. Ultimately, the Minoan eruption of the second millennium BC sealed the remains beneath volcanic deposits (Pearson et al. Reference Pearson, Sbonias, Tzachili and Heaton2023).

Fig. 3. Western sector of excavation with Spaces X3–X4 (plan by C. Athanasiou).

The ongoing study of the pottery is revealing a stratigraphic sequence in Rooms X3 and X4 as follows: the upper layer, stratified above the layer containing the seal-impressed handle, is associated with the building’s destruction phase and includes material likely dating to the late/final EC II period (Fig. 4a). In Room X4, characteristic pottery from the destruction level includes several shallow bowls (Fig. 4:1), fragments of a flat circular hearth with a slightly raised rim (Fig. 4:5), which parallels similar finds from Agia Irini Periods II and III (compare Wilson Reference Wilson1999, 57–8, 117, pl. 61:II-438 and pl. 82:III-235), a slashed, pushed-through handle (Fig. 4:2), a type that became common in the late EC II period (Kariotis Reference Kariotis, Doumas and Devetzi2021, 64), the rim of a large open pot in talc ware with deeply incised herringbone decoration (Fig. 4:3) and several baking pans (Fig. 4:4).Footnote 9 In the related stratigraphic layer of Room X3, the significantly higher presence of talc ware compared to the underlying layer suggests that the destruction layer of these rooms belongs to the late EC II Kastri Group phase.Footnote 10

Fig. 4. Pottery from the context of the seal-impressed handle: (a) pottery from the stratigraphic layer above the layer of the handle; (b) pottery from the layer of the handle (drawings by V. Papazikou; pottery study with the contribution of M. Zavadil).

Thus, a late EC II date likely represents the terminus ante quem for the seal-impressed handle found on the underlying floor level of Room X4. The handle was situated just above the floor, near the threshold, suggesting a likely connection to objects associated with the floor’s use. Pottery from the floor level of X4 (Fig. 4b) primarily consists of dark burnished, polished and plain vases, vessels related to the talc ware and a dark-on-light pattern-painted example (Fig. 4:11). Notable shapes identified include a red-slipped and polished sauceboat (Fig. 4:7), a plain saucer/bowl (Fig. 4:8; similar to examples from Daskalio Phase B; cf. Sotirakopoulou Reference Sotirakopoulou2016, 62, fig. 3.1:6), a grey burnished bowl with an incurving rim (Fig. 4:9), a dark burnished bowl with a lug (Fig. 4:10; similar to Wilson Reference Wilson1999, pl. 16:II-513) and various jars. Of particular importance is a polished bowl or pyxis with a flat-topped rim and ring base (Fig. 4:6), decorated with a grooved herringbone pattern and dated to the EC II phase.Footnote 11 Given the pottery found in the layer, it is likely that the context of the seal-impressed jar dates to the advanced EC II period. The layer beneath the floor is characterised by pottery from the Keros-Syros phase (i.e. EC II), with some older material from the Kampos group, which dominates the lowest deposit above the bedrock.

ANALYSIS OF SEAL IMPRESSIONS

The seal-impressed handle bears two distinct impressions, one on each side, providing insights into seal practices and the broader context of the emergence of writing in the Aegean.

Seal Impression THS.1

Seal Impression THS.1 is a rectangular stamp impressed on the upper attachment area of the handle where it connects to the jar body (Fig. 5). It measures 2.5 x 1.6 cm and consists of three horizontal fields (A–C). The misaligned edges on the left side of these fields suggest that each one comes from a different seal face, likely part of a multi-facial seal.

-

Field A: measuring 0.4 x 2.1 cm, this field is incomplete on the right side due to the narrowing of the handle at that point.

-

Field B: measuring 0.4 x 2.5 cm, this impression is complete.

-

Field C: measuring 0.4 x 2.4 cm, this field is located at the broader attachment area of the handle to the jar body, allowing for a complete impression.

Fig. 5. Seal impression THS.1 on the upper part of the handle, seen from above (drawing by V. Papazikou).

The outlines of the three seal faces are distinctly visible on the left side of the impression, though they do not align, indicating separate applications (Fig. 5). The irregular lines separating the fields were caused by the displacement of clay when each seal face was pressed into the wet clay. The similar dimensions of the three fields – each measuring 0.4 cm in height and 2.4–2.5 cm in length (excluding the incomplete impression on field A) – together with the consistent syntax, style and execution of the motifs across all three fields, as well as the misalignment of their left borders, suggest that a single multi-facial seal was used to create the impressions.

Judging from the orientation of the hook spiral motif hanging in the upper field A, we assume that this field represents the top field (Fig. 5). In this case, the three stamped fields (A–C) were intended to be viewed from above, as presented in Fig. 2a and Fig. 5. When viewing the jar in profile (Fig. 2c), the stamp THS.1 was oriented upside-down and the impression was not clearly visible due to its placement on the relatively horizontal upper attachment area of the handle. Conversely, in this profile view, the second stamp impression THS.2 (Fig. 2c) was properly visible.

Seal shape

Bi-facial and multi-facial seals with rectangular and circular faces have been documented in EBA II contexts in mainland Greece and Crete (e.g., CMS V.2, no. 526 from Asine; CMS II.1, no. 196 from Lentas). In Crete, multi-facial seals from the Prepalatial period, with squarish or ellipsoidal faces, have been associated with various forms, such as gables – a shape commonly linked to the Archanes Script Group (Yule Reference Yule1981, 56–8, Class 14). Other forms include rectangular plates (Yule Reference Yule1981, 72–3, Class 26) and a four-sided bone bar with raised seal surfaces on each face, also bearing signs of the Archanes Script (CMS II.1, no. 391). Aruz (Reference Aruz2008, 62) notes that gables were the most popular shape in Syria-Cilicia from the fourth to early third millennium BC. Gables in Crete often have faces of differing sizes, with engravings typically found on the main seal face (Anastasiadou Reference Anastasiadou2011, 20–2). However, examples of gables with signs on all three seal faces do exist (CMS II.1, no. 393), as do bone cuboid seals with several faces inscribed with motifs and formulae of the Archanes Script Group (CMS II.1, no. 64 from Agia Triada; Sbonias Reference Sbonias, Vasilakis and Branigan2010, 205, pl. 61:S35 from Moni Odigitria).

The elongated form of the three originating seal faces of THS.1 is reminiscent of prismatic seals from the Protopalatial period, specifically three-sided prisms (Yule Reference Yule1981, 66–9, Class 22; Anastasiadou Reference Anastasiadou2011) and four-sided prisms (Yule Reference Yule1981, 65), both of which feature signs of the Cretan Hieroglyphic script. While elongated seal faces with multiple signs appear on prisms in Crete from Middle Minoan (MM) IB–II onward (Yule Reference Yule1981, 170), no EBA examples of prismatic seals have been identified, and the Archanes Script of the late Prepalatial period is not documented on prisms (Yule Reference Yule1981, 171; Sbonias Reference Sbonias1995, 108).

Given the three elongated impressions of THS.1, the originating seal is more appropriately described as a multi-facial seal with three faces of equal dimensions. A three-sided seal of the gable type may have been used to stamp THS.1, but no such seal with elongated faces is known in the Aegean.Footnote 12 Alternatively, multi-facial rectangular plates made of soft stone, such as CMS V.2, no. 526 from Asine, provide another potential comparison. These seals, inscribed on both the upper and lower main faces as well as the narrow, elongated sides, may indicate the existence of multi-facial seals with elongated faces in the Aegean during the EBA.Footnote 13

Syntax and motifs

The decorative pattern of THS.1 is characterised by motifs arranged in a uniform, linear sequence along the length of a narrow field (Fig. 5). Yule notes that this specific syntax, resembling a frieze, is typically associated with prisms, particularly four-sided prisms, and the composition is dictated by the function of the seal surface for inscribing a communication (Yule Reference Yule1981, 187–8). THS.1 represents the earliest example from an EBA II context that combines multi-faciality with signs of roughly equal size, arranged in a linear sequence. This practice is also encountered in late Prepalatial Crete on seals of the Archanes Script Group, which exhibit sequences of signs, the so-called ‘Archanes formula’ (Grumach and Sakellarakis Reference Grumach and Sakellarakis1966; Decorte Reference Decorte2018a; Perna Reference Perna2019, 54–6; Ferrara, Montechi and Valério Reference Ferrara, Montechi and Valério2021; Karnava Reference Karnava and Bennet2021, 245–6).

In examining the motifs of THS.1, five to seven signs are visible in each field (Fig. 6). On face A, which is not fully imprinted, five signs are preserved. Faces B and C likely had seven signs each. On face B, six signs are clearly visible, with a gap where a probable missing sign would be located between signs B3 and B5. Alternatively, this gap might have separated two groups of three signs each. Face C shows seven signs, although two of them (C5 and C6) are indistinct.

Fig. 6. Individual signs of the three fields (A–C) of impression THS.1.

A key question arises regarding the nature of the depicted motifs: are they representational, reflecting actual physical forms that deviate from the observable world (as discussed by Anastasiadou Reference Anastasiadou2011, 161), schematised based on recognisable elements from the empirical world (such as vegetation, animals, humans or objects), or do they represent abstract designs? It can be argued that the individual motifs of THS.1 are both schematised and abstract, making it difficult to establish a direct connection with the physical world. For example, the scroll motif (Fig. 6:A3) may be purely ornamental, while one or two additional signs could be associated with a bifoliate motif (Fig. 6:A5,C7). Other motifs appear more abstract and could potentially correspond to various schematised objects (Fig. 6:A4,B3,B5,C1) or stylised elements of the natural world (Fig. 6:A2,B6). These motifs do not lend themselves to immediate recognition, unlike, for example, motifs of the Archanes Script Group or those found on Protopalatial seals bearing Hieroglyphic inscriptions, which combine both figurative icons and abstract designs (Ferrara Reference Ferrara2018). Further signs in THS.1 are highly abstract, resembling simple geometric or curvilinear forms (Fig. 6:A1,B1,B7,C2,C4,C5,C6).

In the following sections, each of the three fields and the individual signs (Fig. 6) will be discussed, with references made to potential parallels wherever possible.

Field A

-

Sign A1. This sign resembles a right triangle with an irregular left side and a protruding upper corner, possibly representing a schematised figure or object.Footnote 14 Traces of a vertical line parallel to the triangle’s right side may serve to separate it from Sign A2 (Fig. 5).

-

Sign A2. This sign could represent the cuttlefish symbol (CHIC sign 19)Footnote 15 seen in the Archanes Script (Decorte Reference Decorte2018a, 371, appendix I, sign AS 002; Ferrara, Montecchi and Valério Reference Ferrara, Montechi and Valério2021, 57, fig. 9) and Cretan Hieroglyphic (Jasink Reference Jasink2009, 69–71). The body inclines to the right, with a partially preserved forked protrusion at the lower end (cf. CMS VI.1, nos 13a, 14bc). An oblique straight line on the right separates it from Sign A3 (Fig. 5).

-

Sign A3. This sign is a hook spiral or scroll, a motif embedded in the Aegean glyptic tradition.Footnote 16 The central stem, which curves in an unusual leftward direction, forms an angle with the scroll.Footnote 17 The stem might depict a schematised leaf (cf. CMS VI.1, nos 7 and 11). This symbol appears on Minoan seals as a decorative motif and in association with signs of the Archanes Script (Decorte Reference Decorte2018a, 371, appendix I, sign AS*13) and Cretan Hieroglyphic signs (Jasink Reference Jasink2009, 137–8, 189, table 1; Decorte Reference Decorte and Steele2017, 43).

-

Sign A4. This sign, characterised by a narrow body and an exaggerated elongated spout, may represent a ceramic form; however, no handle is discernible and the abstract design makes the identification as a vase form uncertain.Footnote 18

-

Sign A5. This partially preserved sign may depict two joined leaves (bifoliate motif), a popular symbol on Prepalatial seals (Yule Reference Yule1981, 140, motif 19, pl. 12:1,3; CMS V.1, no. 24a; CMS II.1, nos 379, 385a and 387). The bifoliate motif might also appear in association with signs of the Cretan Hieroglyphic script (Yule Reference Yule1981, pl. 29, motif 54:1; Jasink Reference Jasink2009, 29, 189, table 1; CMS VI.1, nos 13a and 28b).

Field B

-

Signs B1 and B2. These are elongated, irregular cuts. B1 is a straight vertical cut with a trapezoidal shape, while B2 is a wedge-shaped cut inclined to the right. A small triangular cut on the left side of B2 may represent either a separating sign or a supplemental mark.

-

Sign B3. This sign likely depicts a conical jug with an elongated, upward-pointing spout, reminiscent of CHIC sign 053. The base is narrower, and there are faint traces of what could be a handle on the left side of the vessel. Minor cuts are also visible to the left of B3 (Fig. 5).

-

Sign B4. This sign appears to be mostly obliterated due to abrasion, though some traces remain visible (Fig. 5).

-

Sign B5. This sign resembles the foot-shaped seals and amulets found in Prepalatial Crete (Branigan Reference Branigan1970; Yule Reference Yule1981, 96; CMS II.1, nos 212 and 407), mainland Greece (CMS I Supp., no. 52), Egypt, Anatolia and the Near East (Aruz Reference Aruz2008, 43; Schmandt-Besserat Reference Schmandt-Besserat1992, 232, table 16:6). It also appears as a script sign.Footnote 19 The Therasia example is a more compact version, lacking the emphasis on the leg, and is comparable to the Minoan foot amulets (Branigan Reference Branigan1970, 7–10, figs 1 and 3; CMS I Supp., no. 52 and CMS II.1, no. 212). However, the pointed, angled protrusion at the top suggests that it may depict a different object altogether.

-

Sign B6. This schematised sign has a curved body inclined to the right, with a crescent-shaped feature at the top and a pointed vertical edge at the lower end. It resembles representations of waterbirds with their heads bent backwards.Footnote 20 Jasink (Reference Jasink2009, 140–1) notes that some examples of this type may have functioned as script signs in Cretan Hieroglyphic.

-

Sign B7. This sign has an irregular trapezoidal form, also inclined to the right.

Field C

-

Sign C1. This sign resembles the ‘Trowel’ sign (CHIC sign 044) from Cretan Hieroglyphic, characterised by a bell-shaped body and a small round head. It frequently appears on three-sided prisms, often in combination with CHIC signs 049 and 005 (Anastasiadou Reference Anastasiadou2011, 245–6 and pl. 63; Decorte Reference Decorte and Steele2017, 39–40, fig. 3.3). The Therasia example has a straight lower side, differing from the typical concave base with upward-curved edges seen in CHIC sign 044 (cf. CMS II.1, no. 420b; CMS VI.1, nos 27ab; CMS VI, no. 88c).

-

Sign C2. This sign consists of two crescents forming an oval shape with a rightward tilt. It could potentially be a variant of the eye symbol (CHIC sign 005; Jasink Reference Jasink2009, 64–5). However, C2 is highly abstract, lacking eyelashes and having a discontinuous outline, making its connection to CHIC sign 005 unlikely. Moreover, the sequence of subsequent signs further distinguishes it from the typical Minoan sign sequence.

-

Sign C3. This two-forked shape, rendered in a calligraphic style, resembles the semantic complement for ‘walking legs’ in Egyptian script (Powell Reference Powell2009, 119, table 5, sign of ‘motion’). It may also resemble a two-forked branch, as seen in some Cretan Hieroglyphic signs (cf. Jasink Reference Jasink2009, 29). However, the Therasia example’s angular endings, reminiscent of feet, suggest a stronger link with the Egyptian sign.

-

Sign C4. This curvilinear cut, inclined to the right, is similar to the central part of Signs A2 and B6. As its upper or lower terminations differ, it appears to be a distinct symbol.Footnote 21

-

Sign C5. This triangular shape may represent a triangular chip-cut (see the discussion in ‘Seal Impression THS2’, below). It also bears some resemblance to the possible representation of a foot amulet in Sign B5.

-

Sign C6. This vertical crescent-shaped cut is poorly preserved, smaller and misaligned with the other signs, suggesting it may serve a complementary function.

-

Sign C7. This sign resembles two leaves joined at an angle, likely forming a bifoliate motif (cf. discussion of Sign A5; compare with CMS VI.1, no. 13a, a seal of the Archanes Script Group).

A key observation regarding the motifs and style of THS.1 is the scarcity of representational forms and pictorial designs, such as anthropomorphic figures, animals, schematic quadrupeds, plant forms, or other recognisable objects. Instead, the prevailing elements are predominantly abstract and geometric shapes, which have a non-regular appearance and are difficult to interpret. Even those motifs that can potentially be linked to recognisable designs are not figural but ambiguous, leaving them open to interpretation or conjecture. Moreover, these motifs consistently show a rightward inclination.

An important question arises: are the motifs on the Therasia impression purely decorative, or could they be interpreted as signs conveying some form of communication? To explore this, it is crucial to investigate whether these signs bear any resemblance to Aegean scripts engraved on seals from the early second millennium BC, such as the so-called Archanes Script of the late Prepalatial period (Grumach and Sakellarakis Reference Grumach and Sakellarakis1966; Sbonias Reference Sbonias1995, 109–13; Decorte Reference Decorte2018a; Ferrara, Montechi and Valério Reference Ferrara, Montechi and Valério2021) or the Cretan Hieroglyphic of the Protopalatial period (Olivier and Godart Reference Olivier and Godart1996, 387; Jasink Reference Jasink2009; Karnava Reference Karnava2000; Anastasiadou Reference Anastasiadou2016; Decorte Reference Decorte and Steele2017). Additionally, potential correspondences with other known writing systems from the Eastern Mediterranean in the third millennium BC, such as the Egyptian Hieroglyphic and Cuneiform script, should also be considered.

At first glance, the signs on the Therasia impression cannot be confidently categorised within any known corpus of script signs from the Eastern Mediterranean. Nevertheless, known signs from Aegean scripts might serve as a starting point for comparison, as they share some common characteristics with the Therasia impression: engraving on seals, multi-faciality of the seal shape associated with a sequence of signs on the seal face, and some comparable structural principles (e.g., the linear arrangement of same-sized signs, the possible existence of dividing signs and the potential presence of secondary or supplementary signs that may hold a sematographic significance).Footnote 22 In that respect, certain similarities might be identified. For example, Signs A2, C1 and possibly B3 resemble signs from the Archanes Script Group and Cretan Hieroglyphic script, while Sign C3 may correspond to the Egyptian hieroglyphic semantic indicator denoting rapid motion. Additionally, some schematised motifs with a possible iconic character, such as Signs A3, B5 and B6, are also found on Minoan seals in association with hieroglyphic signs. However, these resemblances do not form part of a coherent system recognisable in later developments of Aegean scripts.

Regarding the differences, one notable distinction is that THS.1 features a greater number of individual motifs per field compared to seals with signs from the Archanes Script and Cretan Hieroglyphic. The grouping of specific signs into structured sign sequence, as seen on seals bearing these scripts, does not align with the arrangement observed in the Therasia example. Additionally, while THS.1 is linked to a multi-facial seal, it lacks the combination of signs that might indicate a sequence of script signs with accompanying decorative, figural, or pictorial motifs on the other faces of the seal. Interestingly, all three fields of THS.1 consistently display the same arrangement of comparable signs, contrasting with the multi-facial seals bearing signs of the Archanes Script and Cretan Hieroglyphic, where a variety of motifs or sign combinations often appear across different faces. This suggests a different approach to the use of signs and imagery on seals in the Therasia example.

Seal Impression THS2

THS.2 is stamped on the lower end of the jar handle and has a rectangular shape, measuring 2.7 x 3.1 cm (Fig. 7). It originates from a single rectangular stamp seal, as indicated by the clear imprint of the continuously aligned edge of the seal face on the left side of the impression. The rounded corners of the seal face further reflect characteristics commonly found in seals with rectangular faces (e.g., CMS XI, no. 5; CMS XI, no. 139; CMS V.2, no. 526).

Fig. 7. (a) Seal impression THS.2 on the lower part of the handle; (b) modern mould showing the mirrored design of the original seal face (cut in relief); (c) drawing of the image (by V. Papazikou); (d) reconstruction of THS.2 with preserved parts of the motif highlighted (K. Sbonias).

The seal impression is only partially preserved, likely due to issues related to the stamping of the handle before the vessel was fired. The slightly concave surface in the central part of the handle may explain the incomplete impression. The left part of the design is well-preserved, featuring a decoration organised in four parallel zones (Fig. 7cd). Traces of the motifs are visible in the upper right corner, suggesting that the design continued across the entire seal face.

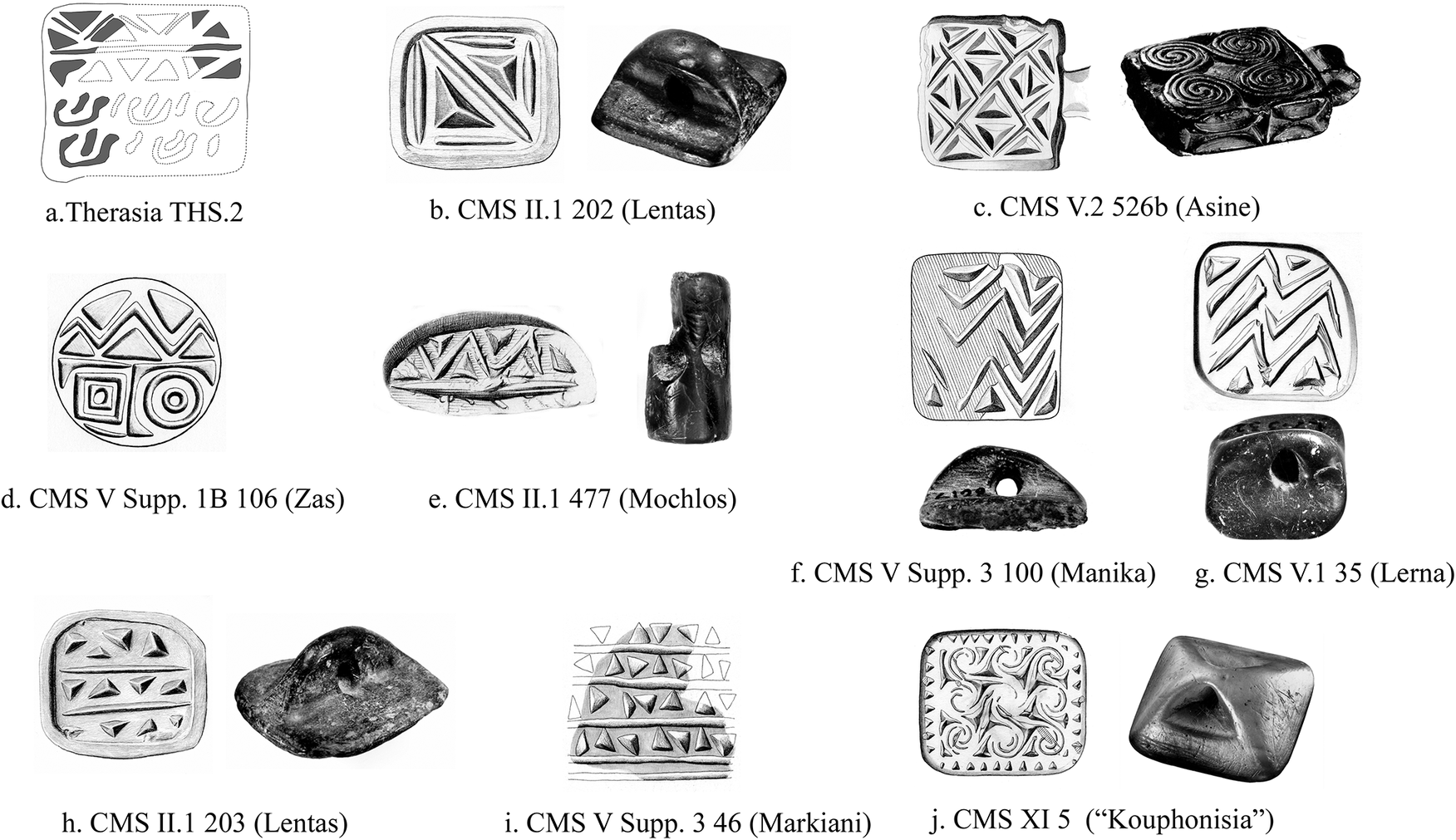

Seal shape

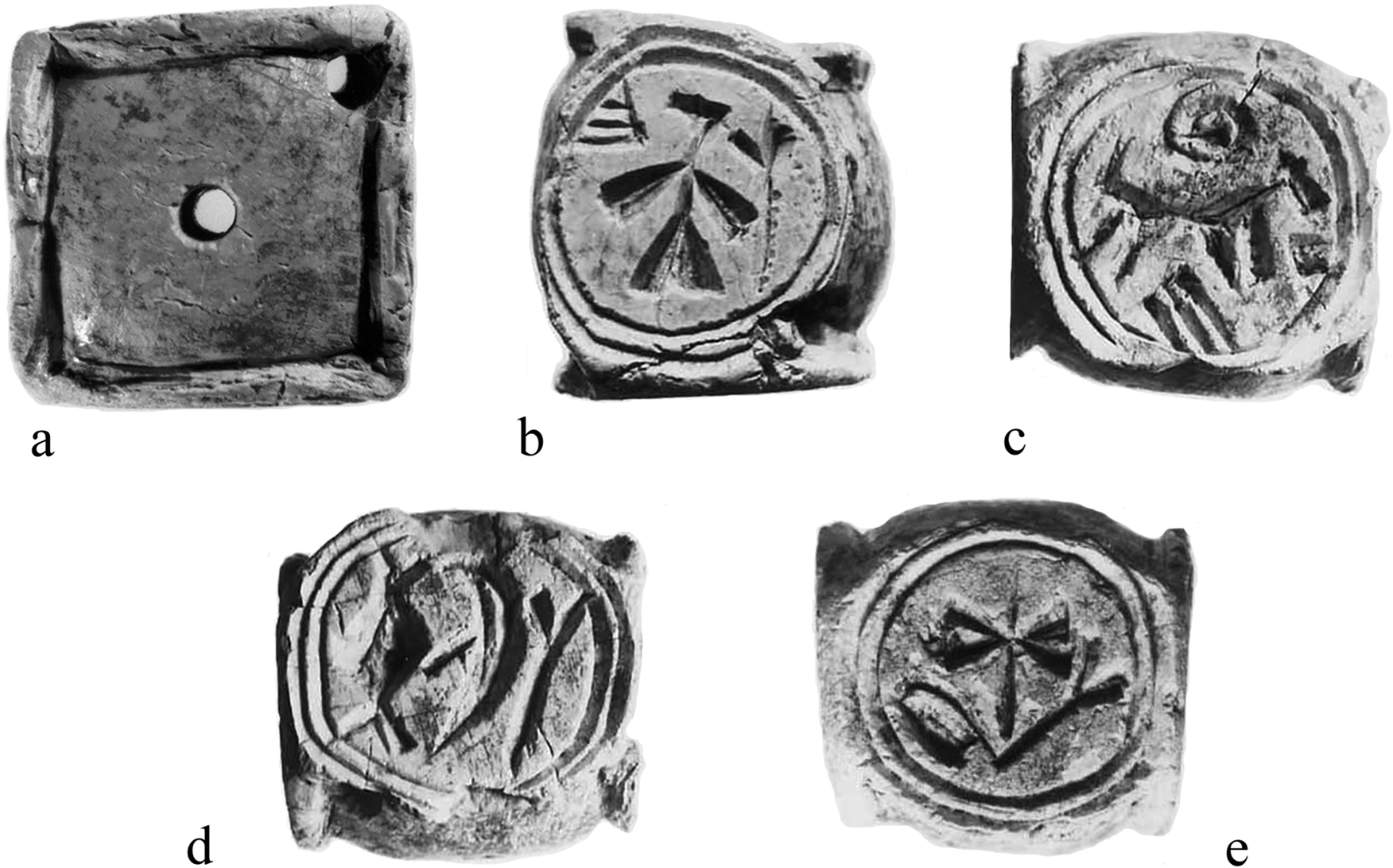

Rectangular seal faces are relatively rare in Aegean seals, where circular faces are more common (Krzyszkowska Reference Krzyszkowska2005, 39–40). However, examples of rectangular seals provide clues about the possible shape of the original seal associated with THS.2 (Fig. 8). A close parallel can be seen in the rectangular, multi-facial seal CMS V.2, no. 526 from Asine (Fig. 8c), which features a hammer-headed terminal and measures 3.2 x 3.2 cm. This seal shares similarities with THS.2 in both dimensions and iconography, particularly its triangular ‘chip carved’ decoration. Another possible parallel is the rectangular button seal with a pierced grip (Fig. 8b), a rare form in Crete (Yule Reference Yule1981, 83–4) found in two examples at Lentas (CMS II.1, nos 202–3) and possibly at ‘Knossos’ (CMS VII, no. 213). J. Aruz (Reference Aruz2008, 36, n. 153) highlights the Anatolian and Syrian influences of this type. Comparable seals have been discovered in EBA contexts across the Aegean, such as at Manika in Euboea (CMS V Supp. 3, nos 100–1) and Lerna (CMS V.1, no. 35), combining rectangular faces with triangular ‘chip-carved’ decoration (Fig. 8fg). A rectangular plate with rounded corners and a protruding grip, possibly originating from ‘Aigina’ (CMS XI, no. 139), provides another parallel for the shape. Additionally, pyramidal seals can also have quadrangular bases (Yule Reference Yule1981, 69–70). Examples include CMS XI, no. 5 from ‘Kouphonissia’ (Fig. 8j) and CMS V Supp. 3, no. 241, a stray find from Chimarros on Naxos. These pyramidal seals feature protruding grips and have Egyptian parallels (Aruz Reference Aruz2008, 35). Both examples are decorated with interlocking spirals engraved in relief, a Cycladic characteristic, and CMS XI, no. 5 (Fig. 8j) is surrounded by a border of triangular notches, another Cycladic feature (Aruz Reference Aruz2008, 35).

Fig. 8. Seals and sealings from EBA contexts, primarily featuring rectangular seal faces and triangular chip-cut decoration (Images courtesy of the CMS Heidelberg).

Seals with rectangular faces vary in size, ranging from 1.6 to 3.3 cm in length and 1.5 to 3.2 cm in height. At 2.7 x 3.1 cm, THS.2 is among the larger examples, comparable to the elaborately designed CMS V.2, no. 526 from Asine (Fig. 8c) and CMS V Supp. 3, no. 100 from Manika (Fig. 8f). All of the aforementioned examples were made from soft stone, and it is likely that the original stamp associated with THS.2 was also crafted from soft stone, based on the angular nature of the impressed motifs.

Syntax and decorative pattern

The primary structural principal of THS.2’s design is the division of the seal face into four parallel zones (Fig. 7cd). A horizontal line separates the upper zone from the second, visible at both ends of the impression. While the remaining fields feature horizontally arranged motifs, they are not divided by lines. The decorative pattern consists of two types of geometric designs: triangular chip-carving decoration in the two upper zones and meander motifs in the two lower zones.

Τhe motif in the upper zone is composed of triangular cuts or chip-carving (Yule Reference Yule1981, 156, motif 39). These triangles are arranged antithetically on either side of a diagonal line, and it is likely that the motif repeats across the entire length of the field, as indicated by the sections on the left and right sides of the impression. A close parallel to this motif can be found in CMS II.1, no. 202 from Lentas Tholos II (Fig. 8b). CMS V.2, no. 526b from Asine displays a more complex decorative syntax, featuring rectangular and triangular fields filled with triangular chip-cuts in a rapport pattern (Fig. 8c). In both cases, the triangular chip-cuts along the sides of the seal face closely resemble the principal motif observed in the Therasia impression – triangular chip-cuts separated by diagonal lines.

The second zone of THS.2, which is narrower and less well preserved, appears to feature a design consisting of antithetically arranged triangular cuts in a line (Fig. 7cd). Similar patterns are found in CMS II.2, no. 203 from Lentas (Fig. 8h), CMS V.2, no. 526c from Asine and CMS V.2, no. 527e from Midea. In CMS II.1, no. 203, the seal face is divided by lines into three parallel zones, each decorated with rows of triangular chip-cuts (Fig. 8h). A similar composition, with four zones divided by parallel lines, can be found on sealing CMS V Supp. 3, no. 46 from Markiani on Amorgos (Fig. 8i), which is associated with the Kampos phase (Angelopoulou Reference Angelopoulou, Marangou, Renfrew, Doumas and Gavalas2006, 220–2, fig. 8.25:069).

The chip-carving decoration, often associated with seals featuring rectangular faces and a protruding grip (Fig. 8bcfghj), serves as a principal identifying feature of Yule’s Early Minoan (EM) I?–II Chip-Cut/Small Plate Signet Group, a group with affinities to the Cyclades and mainland Greece.Footnote 23 Beyond Crete, the distribution of chip-cut decoration extends to mainland Greece,Footnote 24 the CycladesFootnote 25 and Euboea.Footnote 26 Triangular chip-cuts are arranged on the seal face in various syntactic patterns,Footnote 27 with several examples originating from the Cyclades, while the combination of rectangular seal faces and triangular motifs is rare in Cretan Prepalatial seals (cf. also Krzyszkowska Reference Krzyszkowska2005, 61).

The two lower zones of THS.2 are decorated with a meander pattern. The motif, more distinctly visible in the lower-left part of the impression, consists of a rectangularly wound meander with a central line, repeated across the field (Fig. 7cd). Although there are no exact parallels for this motif, a comparable example can be found in CMS V.1, no. 39 from Lerna, which displays two ovals with a central tongue encircled by lines (Wiencke Reference Wiencke1969, 509, no. 198). A more distant comparison can be drawn to CMS V Supp. 3, no. 101 from Manika. The design of THS.2 cannot be fully interpreted from the impression alone but becomes clearer when examining the modern mould in Fig. 7b, which reconstructs the original seal design. The motif appears to consist of a continuously wound meander cut in relief (positive) on the seal itself. On the impression, the design appears in the negative, formed by the engravings cut around the meander (Fig. 7ac).

In conclusion, several features suggest that THS.2 shares affinities with the Cyclades, such as the use of chip-carving decoration and the execution of the design in relief on the original seal – a characteristic of the Cycladic seal tradition (Krzyszkowska Reference Krzyszkowska2005, 42; Aruz Reference Aruz2008, 35; Weiberg Reference Weiberg2010, 198; Weingarten et al. Reference Weingarten, MacVeagh Thorne, Prent and Crouwel2011, 146–7, 154, design G-16). Chip-carving is particularly prevalent on Cycladic ceramic and stone vessels from the Grotta-Pelos and Keros-Syros cultures, and it is widely associated with Cycladic material culture (Yule Reference Yule1981, 208; Sbonias Reference Sbonias1995, 79). The overall synthesis and decorative syntax of THS.2, featuring the division of the seal face into separate zones, is a characteristic found on several seals and sealings from Cycladic contexts, including Zas Cave on Naxos (CMS V Supp. 1Β, no. 106), Markiani (CMS V Supp. 3.1, no. 46) and Skarkos on Ios (CMS V Supp. 3.1, no. 169). This type of decorative syntax is less common on mainland Greece, where motifs typically form closed compositions arranged around a central point (Heath Reference Heath1958; Krzyszkowska Reference Krzyszkowska2005, 42–5). The seal pendant from Asine (CMS V.2, no. 526), which bears similarities to THS.2, is considered a possible import from the Cyclades, as suggested by the rendering of the spiral motif in relief and the use of triangular notch decoration (Krzyszkowska Reference Krzyszkowska2005, 39; Weiberg Reference Weiberg2010, 198). Given the combination of shape and motif, along with the distribution of similar motifs across the region, a Cycladic origin for the seal associated with THS.2 from Therasia appears plausible. In particular, the triangular chip-cut decoration reflects broader Cycladic cultural practices, whereas examples from Crete, particularly those from Lentas, stand out as exceptional within the Cretan context.Footnote 28

PETROGRAPHIC ANALYSIS OF THE SEAL-IMPRESSED FRAGMENTFootnote 29

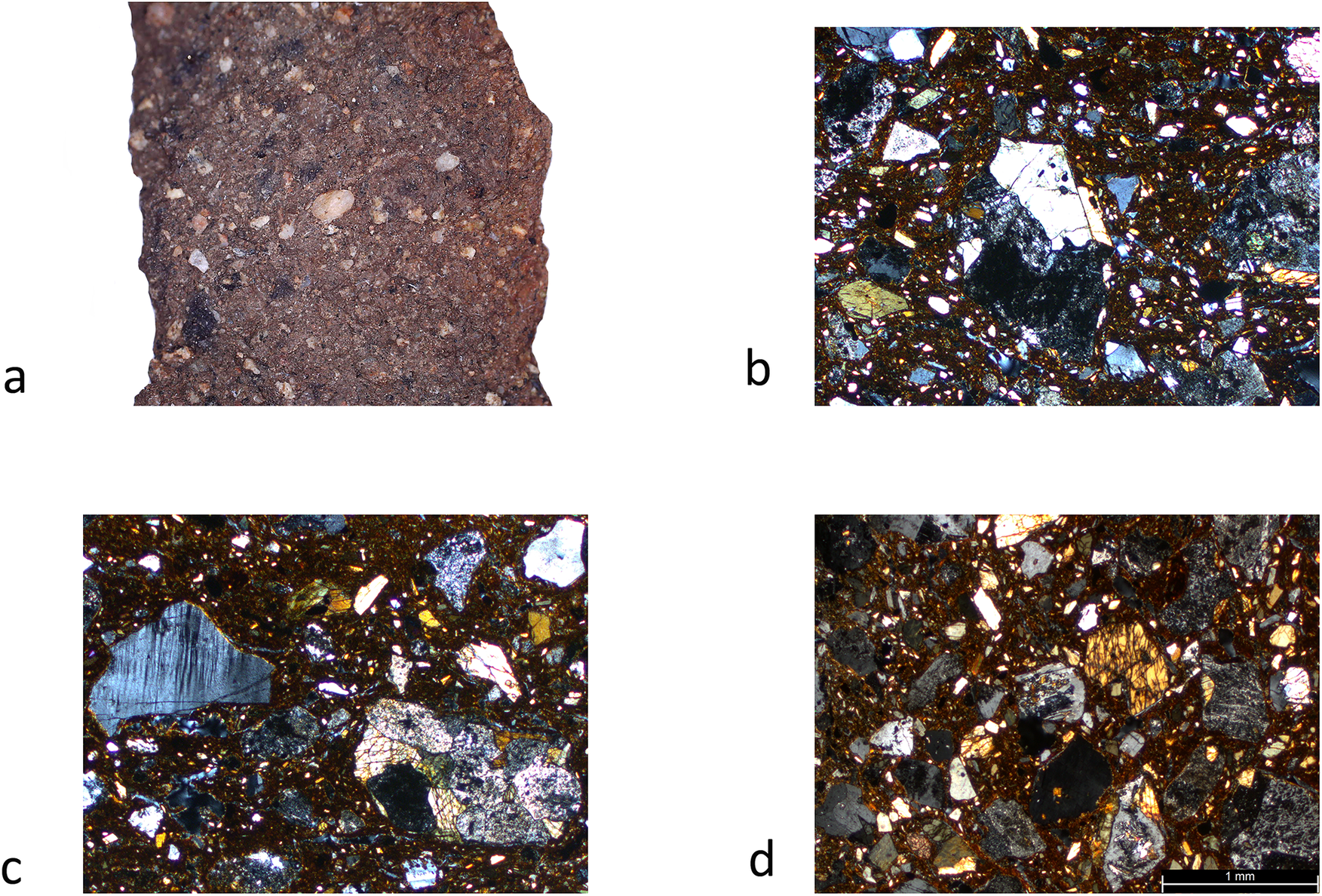

Macroscopic examination

The jar exhibits a coarse macro-fabric that is uncommon within the Therasia pottery assemblage. A macroscopic examination of the sampled sherd under an RS PRO USB handheld digital microscope revealed that the macro-fabric is characterised by densely packed, mostly rounded black and milky-white inclusions (Fig. 9a). The jar was likely produced using a mould, and the potter smoothed the interior while wiping the exterior for surface treatment. The interior of the sampled sherd has a yellowish-red hue (5YR 5/6),Footnote 30 while the exterior ranges from reddish-brown (2.5YR 5/4) to black (2.5Y 2/5/1). The fresh break appears very dark grey (5YR 3/1) throughout. After refiring the sample at 1000°C, the colour shifted to red.

Fig. 9. (a) Close up picture of the Therasia sample under a RS PRO USB digital handheld microscope (maximum body wall thickness 1.1 cm); (b) photomicrograph in cross-polarised light/XP of the Therasia sample (field of view 3.24 mm); (c) photomicrograph in XP of the Therasia sample (field of view 3.24 mm); (d) photomicrograph in XP of an EC II pottery sample from Akrotiri (G.S. Kordatzaki).

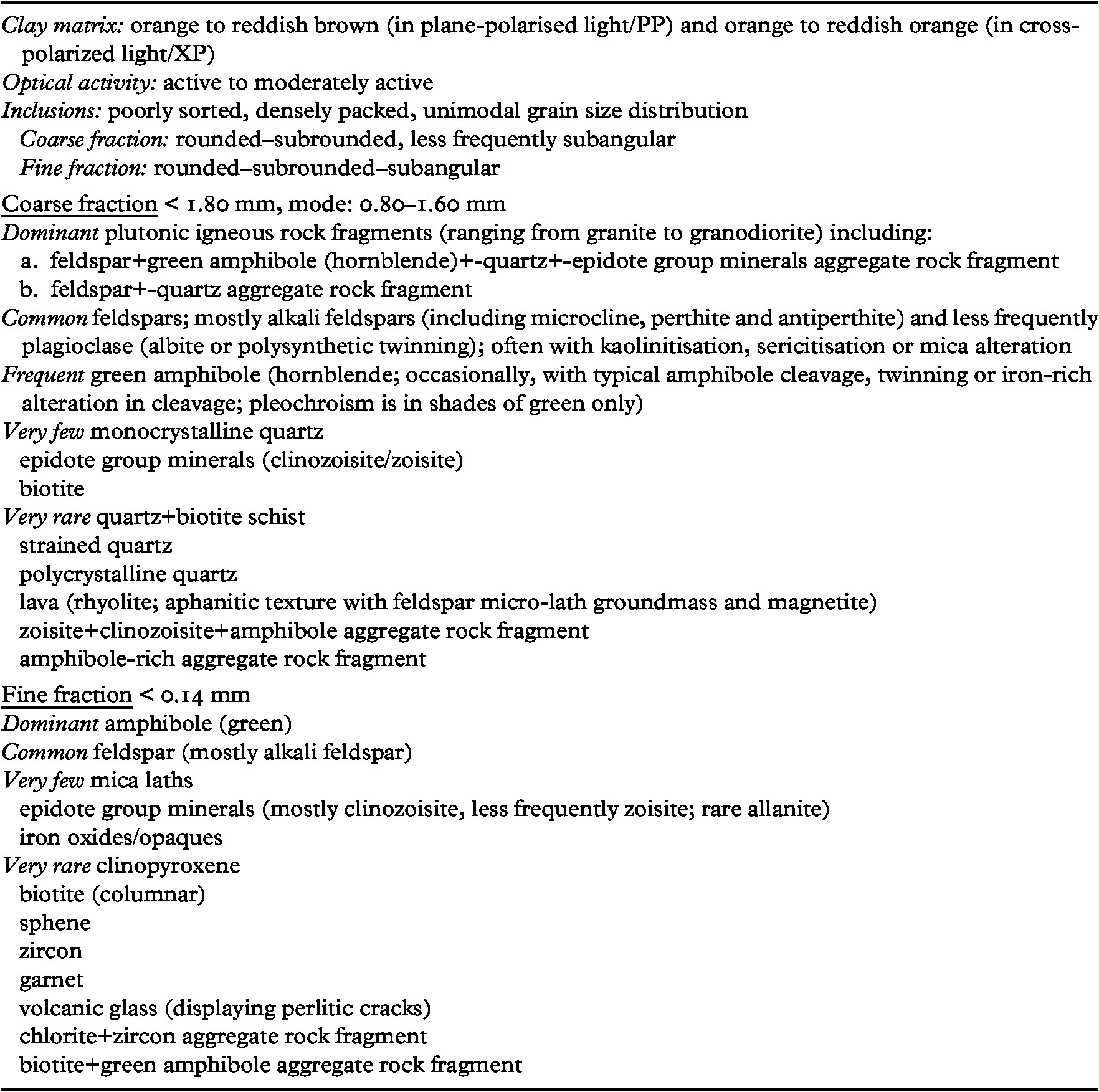

Thin section analysis

Pottery thin section analysis (for detailed results, see Table 1) confirmed that the jar relates to a coarse, low-calcareous fabric. The primary components are granitic plutonic igneous rock fragments, ranging in composition from granite to granodiorite, along with their constituent minerals, mainly feldspars and green amphiboles (hornblende) (Fig. 9bc). Feldspars, whether as part of the plutonic rock fragments or dissociated minerals, are predominantly alkali, with occasional plagioclase. The majority of the feldspars show heavy weathering, though some fresher examples are present. A few plutonic grains display slight deformation. The amphiboles, present both within the plutonic rock fragments and as individual inclusions, are pleochroic, consistently in shades of green. Epidote group minerals, though less frequent, appear as accessory components or individual inclusions from the plutonic sources. The analysis also revealed the very rare presence of schist and volcanic lava particles, as well as individual grains of sphene, zircon, and garnet.

Table 1. Detailed petrographic description (G.S. Kordatzaki).

The optically active to moderately active clay matrix suggests inconsistent firing conditions at relatively low temperatures (below 800°C). The red colour observed after refiring, along with the clay matrix’s appearance, indicates a low-calcareous clay paste. The overall composition, grain size distribution and matrix colour suggest the use of poorly sorted, immature low calcareous clayey sediments, likely derived from the decomposition of mostly intrusive plutonic rocks (ranging from granite to granodiorite).

Provenance determination

The provenance of the sampled jar was determined by considering the following factors:

-

1. Local and regional geology. The geology of Therasia and the surrounding area, as documented in Institute of Geology and Mineral Exploration of Greece (IGME) geological maps and published geological studies, was compared with the sampled sherd. This allowed for an initial assessment of the sherd’s compatibility with known geologies.

-

2. Previous petrographic analysis. A prior petrographic analysis by Kordatzaki (Reference Kordatzaki, Palyvou and Tzachili2015; Kordatzaki et al. Reference Kordatzaki, Sbonias, Farinetti and Tzachili2018) on a small selection of prehistoric ceramic samples from the Therasia survey pottery assemblage (see Sbonias, Farinetti and Kordatzaki Reference Sbonias, Farinetti, Kordatzaki, Palyvou and Tzachili2015) provided a comparative framework.

-

3. Comparative data from Cycladic islands. Published pottery fabrics of known provenance and comparative thin section data (including pottery samples and geomaterials) from different Cycladic islands were also examined. These comparisons were conducted by Kordatzaki, utilising the reference collection from the Fitch Laboratory, British School at Athens. Additional comparisons were made with pottery thin sections from EC Akrotiri, provided by P.M. Day and N.S. Müller, and with two thin sections of Early Iron Age Naxian fabrics, courtesy of X. Charalambidou, which was initially thought to bear some resemblance to the fabric under study from Therasia.

Distribution of granitic plutonic rocks across and beyond the Cyclades

The Cyclades are part of the Attic-Cycladic metamorphic belt (Higgins and Higgins Reference Higgins and Higgins1996, 170–2; Altherr et al. Reference Altherr, Kreuzer, Wendt, Lenz, Wagner, Keller, Harre and Höhndorf1982; Schliestedt, Altherr and Matthews Reference Schliestedt, Altherr, Matthews and Helgeson1987), characterised by blueschist facies and greenschist facies assemblages from the Eocene and Miocene, respectively. Shortly after these geological epochs, granitic rocks intruded on several islands, with compositions ranging from granodiorites and granites to monzonites. Subsequently, the subduction of the eastern Mediterranean seafloor beneath the Aegean led to volcanic activity along the South Aegean volcanic arc.

Santorini (Thera, Therasia, and Aspronisi) falls within this volcanic arc (Nomikou, Hübscher and Carey Reference Nomikou, Hübscher and Carey2019; Vougioukalakis, Satow and Druitt Reference Vougioukalakis, Satow and Druitt2019) and is dominated by volcanic lithologies (Pichler, Günther and Kussmaul Reference Pichler, Günther and Kussmaul1980; Higgins and Higgins Reference Higgins and Higgins1996, 187–95), including significant ash and pumice deposits. Thera’s lavas primarily range from andesite to dacite and rhyolite (Druitt, Pyle and Mather Reference Druitt, Pyle and Mather2019), while Therasia’s lavas are of quartz-andesitic composition (Vougioukalakis Reference Vougioukalakis, Palyvou and Tzachili2015).

Given the composition of the sample, special emphasis was placed on the distribution of plutonic intrusive rocks, ranging from granite to granodiorite, within and beyond the Cyclades, as well as in proximate and more distant areas. Such lithologies are absent in the nearby mainland regions of Greece but do occur on several Cycladic islands in considerable quantities (Altherr et al. Reference Altherr, Kreuzer, Wendt, Lenz, Wagner, Keller, Harre and Höhndorf1982, 100, fig. 1; Higgins and Higgins Reference Higgins and Higgins1996, 170–95, 171, fig. 15.1), including Mykonos and the adjacent small islands of Delos and Rheneia (Avigad, Baer and Heimann Reference Αvigad, Baer and Heimann1998; Avdis Reference Avdis2004), Seriphos (Zámolyi et al. Reference Zámolyi, Székely, Draganits, Timár, Grasemann, Petrakakis, Iglseder, Rambousek, Hubmann and Piller2004), and Naxos (Jansen Reference Jansen1973; Vanderhaeghe et al. Reference Vanderhaeghe, Hibsch, Siebenaller, Martin, Duchêne, de St Blanquat, Kruckenberg, Fotiadis, Lister, Forster and Ring2007). Less extensive granitic bodies are present within the metamorphic formations on Paros (Higgins and Higgins Reference Higgins and Higgins1996, 180–2) and on the island of Tenos (Avigad, Baer and Heimann Reference Αvigad, Baer and Heimann1998). Although Santorini is dominated by volcanic lithologies, extremely limited granite intrusions cut through the metamorphic basement of Thera at the port of Athenios (Skarpelis, Kyriakopoulos and Villa Reference Skarpelis, Kyriakopoulos and Villa1992) and along Therasia’s lowest cliffs (Kamvisis Reference Kamvisis2019, 23–4).

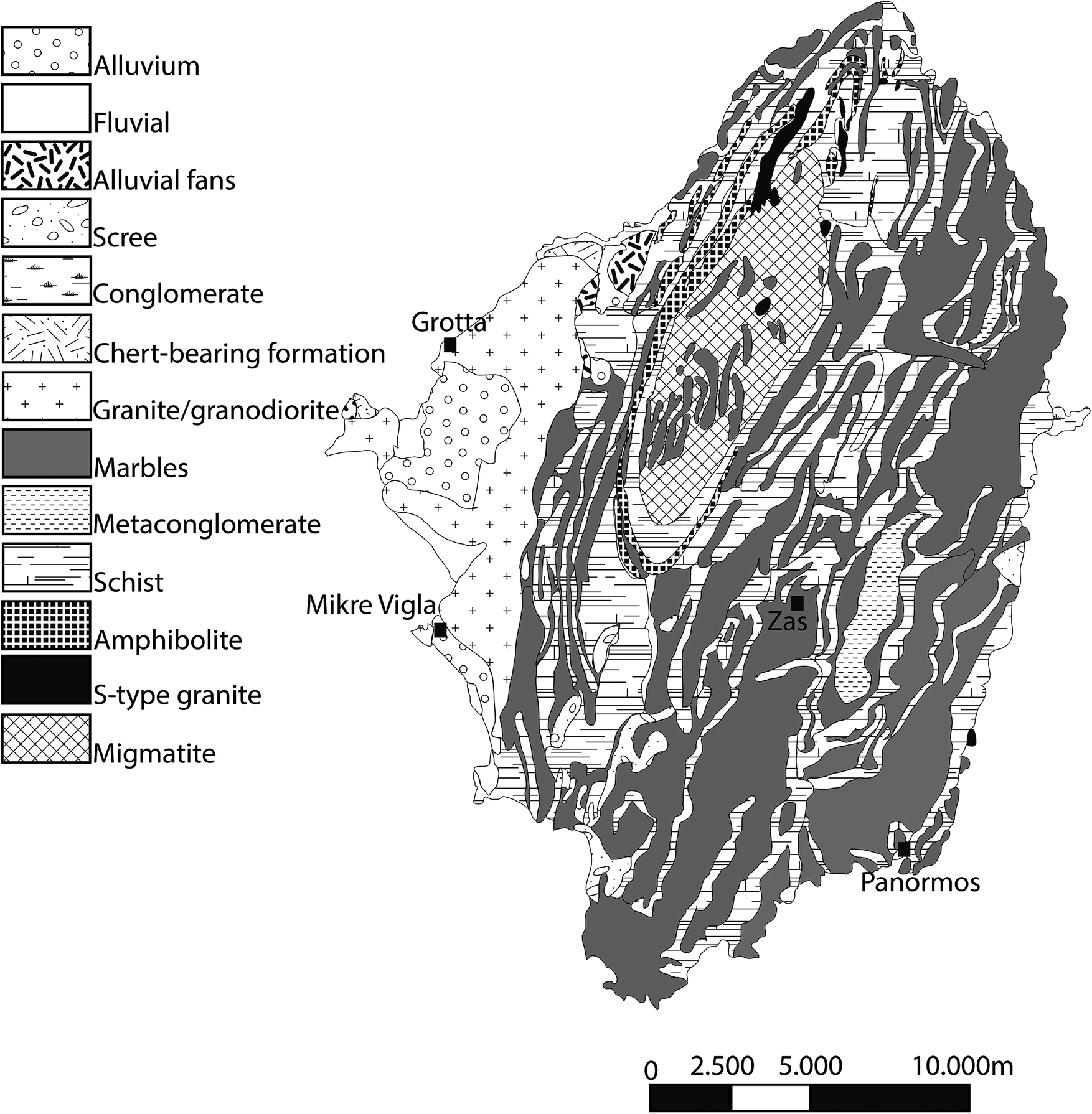

Naxos, the largest of the Cycladic islands, represents one of the closest sources of intrusive formations to Therasia (Fig. 10). Much of the island is dominated by metamorphic rocks of the Attic-Cycladic massif (Urai, Schuiling and Jansen Reference Urai, Schuiling, Jansen, Knipe and Rutter1990), while its western part is covered by plutonic rocks. The geology of the island consists of three distinct, main units that comprise: a) the upper non-metamorphic unit, including Miocene and Pliocene sedimentary rocks (e.g., chert-bearing formations, conglomerate etc.), b) the Cycladic blueschist unit, a metamorphic complex characterised by a migmatite core surrounded by sequences of marbles, metapelites/metaconglomerates, schists, amphibolites and gneiss, and c) the granite massif, covering the western part of the island, which compositionally ranges from granite to granodiorite.Footnote 31 Additionally, small S-type granitic formations occur in the northern part of the island.

Fig. 10. Modified map of Naxos (after Jansen Reference Jansen1973) showing the geological formations (G.S. Kordatzaki).

Beyond the Cyclades, in the central Aegean, granite outcrops are found in the western part of Ikaria (Higgins and Higgins Reference Higgins and Higgins1996, 144; Ring Reference Ring, Lister, Forster and Ring2007). In the southern Aegean, granite to granodiorite lithologies are found in small areas of Crete, including the north-eastern coast at Mirabello Bay (Papastamatiou Reference Papastamatiou1959).

Pottery fabrics: provenance considerations for the jar from Therasia

Prehistoric pottery fabrics local to Santorini are typically characterised by volcanic rock fragments – primarily lavas of andesitic composition – along with pumice, tuff and volcanic glass in varied quantities, and their constituent minerals (Williams Reference Williams and Doumas1978, 508–9; Vaughan Reference Vaughan, Hardy, Doumas, Sakellarakis and Warren1990, 471–4, 482–5; Müller Reference Müller2009, 61–7; Kordatzaki Reference Kordatzaki, Palyvou and Tzachili2015, 61–4; Müller, Kilikoglou and Day Reference Müller, Kilikoglou, Day, Spataro and Villing2015, 39–40; Kordatzaki et al. Reference Kordatzaki, Sbonias, Farinetti and Tzachili2018, 6–10; Day, Müller and Kilikoglou Reference Day, Müller, Kilikoglou and Nikolakopoulou2019, 335–40; Hilditch Reference Hilditch and Nikolakopoulou2019).

Thin section analysis of the sample suggests that the raw materials originate from outside Santorini, likely from areas dominated by lithologies ranging from granite to granodiorite. This source should be traced to regions where granitic plutonic rocks have decomposed and deposited alongside rare volcanic and metamorphic rock fragments within the same drainage systems. Geological prospection on Naxos has shown that certain drainages provide sediments with this distinctive mixed composition (Hilditch Reference Hilditch, Renfrew, Doumas, Marangou and Gavalas2007, 248). The plutonic-metamorphic-volcanic admixture of rock fragment inclusions is typical of certain clay pastes from Naxos (Vaughan Reference Vaughan1989, 151–4; Hilditch Reference Hilditch, Renfrew, Doumas, Marangou and Gavalas2007, 240–1, 248, 257–8; Müller Reference Müller2009, 295–7; Hilditch Reference Hilditch and Nikolakopoulou2019, 419–22). The varying rations of rock types, combined with micro-compositional diversity and varying degrees of deformation and weathering, have led to the identification of a broad range of distinct pottery fabrics from Naxos (Williams Reference Williams and Doumas1978, 509; Vaughan Reference Vaughan1989; Reference Vaughan, Hardy, Doumas, Sakellarakis and Warren1990, 476–8; Müller Reference Müller2009, 67–70, 295–7; Knappett et al. Reference Knappett, Pirrie, Power, Nikolakopoulou, Hilditch and Rollinson2011, 223–9; Charalambidou, Kiriatzi and Müller Reference Charalambidou, Kiriatzi, Müller, Handberg and Gadolou2017, 123–5; Day, Müller and Kilikoglou Reference Day, Müller, Kilikoglou and Nikolakopoulou2019, 350–1; Hilditch Reference Hilditch and Nikolakopoulou2019, 419–22, 446–9, 467–9). The remarkable variation of Naxian fabrics implies different sources of exploitation that are linked to several possible coexistent production centers (Vaughan Reference Vaughan1989, 151–4, 159; Charalambidou, Kiriatzi and Müller Reference Charalambidou, Kiriatzi, Müller, Handberg and Gadolou2017, 127; Hilditch Reference Hilditch and Nikolakopoulou2019, 420, 447–8).

Past systematic studies of Early and Middle Cycladic pottery fabrics from Naxos have shown that many local fabrics fall between meta-granite and granite compositions (Vaughan Reference Vaughan1989; Hilditch Reference Hilditch, Renfrew, Doumas, Marangou and Gavalas2007, 240–1). J. Hilditch (Reference Hilditch and Nikolakopoulou2019, 421–2) documented the prevalence of meta-granitic fabrics in EC sites such as Zas Cave and Grotta, while granitic fabrics dominate at Mikre Vigla. Examination by Kordatzaki of the Fitch Laboratory’s thin section and geomaterials collection did not yield an exact match for the Therasia sample. The same applies to the two Early Iron Age pottery thin sections from Tsikalario and Grotta, provided by Charalambidou. Notably, the EC felsic fabrics from Naxos do not contain as high a concentration of green amphiboles as the jar from Therasia. Moreover, the examined Naxian fabrics contain much more metamorphic grains (including meta-granite inclusions) than the fabric of the sample from Therasia.

Nevertheless, N.S. Müller documented the same granite–granodiorite, green amphibole-rich pottery fabric at Akrotiri and attributed it to Naxos (Müller Reference Müller2009, 61, 67–70, 70, fig. 4.6de, 296–7). Recent comparisons by Kordatzaki between this fabric from Akrotiri (Fig. 9d) and the jar from Therasia (Fig. 9bc) confirmed that they are identical. Müller’s analysis indicated that this fabric was primarily used for cooking vessels at Akrotiri and less frequently for storage pots, from the very beginning of the EC period through MC phase A. The compositional consistency between this fabric and the geology of Naxos was the main reason for Müller to attribute the rich-in-green amphiboles felsic fabric to Naxos. More recently, a pottery fabric from the site of Panormos on Naxos was also presented as directly comparable (Day, Müller and Kilikoglou Reference Day, Müller, Kilikoglou and Nikolakopoulou2019, 351, fig. 3.73), but Kordatzaki’s analysis revealed no similarities with the Therasia sample. It should be stressed that the fabric of the jar under study is not unique within the Therasia pottery assemblage; it has been identified petrographically among the survey pottery sherds (Kordatzaki et al. Reference Kordatzaki, Sbonias, Farinetti and Tzachili2018, 8, figs 7f and 10), though it appears very rarely.

Apart from Naxos, other Cycladic islands with granitic plutonic rocks, such as Mykonos and the adjacent islands of Seriphos, Paros, and Tenos, could potentially be sources of the raw materials used for the jar.Footnote 32 However, due to a lack of systematic studies on prehistoric pottery fabrics from these islands,Footnote 33 further support for this hypothesis is currently unavailable.

The same applies to the island of Ikaria, where data for the early habitational pattern is missing. Further south, in the east part of Crete, the well-known Mirabello fabrics – primarily of granite–granodiorite composition (Day et al. Reference Day, Joyner, Kiriatzi, Relaki, Haggis and KAVOUSI2005, 183–5; Nodarou and Moody Reference Nodarou, Moody, Molloy and Duckworth2014) – differ from the fabric under study, making a Cretan origin unlikely (Eleni Nodarou, pers. comm.).

Despite the absence of an exact match between the Therasia sample and known Naxian fabrics, Naxos remains the most likely source for the raw materials used in the jar under study. The fabric composition aligns with the geology of Naxos, and the island’s strong connections with Santorini during the Early and Middle Cycladic periods further supports this hypothesis. Naxian pottery reached sites such as Koimisis and Akrotiri in significant quantities, as confirmed by a broad range of other pottery linked to the island (Müller, Kilikoglou and Day Reference Müller, Kilikoglou, Day, Spataro and Villing2015, 39; Kordatzaki et al. Reference Kordatzaki, Sbonias, Farinetti and Tzachili2018, 12–13; Day, Müller and Kilikoglou Reference Day, Müller, Kilikoglou and Nikolakopoulou2019, 353; Hilditch Reference Hilditch and Nikolakopoulou2019, 447). Nevertheless, future pottery petrographic studies, combined with geological prospection and sampling, may shed additional light on whether other Cycladic islands could also be sources of granite–granodiorite, green amphibole-rich fabrics. In addition, the stylistic and iconographic analysis of one of the seal impressions stamped on the handle (THS.2) further supports the jar’s Aegean origin, demonstrating affinities with the Cycladic and broader Aegean glyptic tradition.

DISCUSSION

In the EBA Aegean, the use of seals for sphragistic purposes is associated with applying sealings to objects such as ceramic vessels, baskets and pegs, likely related to securing the closure of boxes or doors, thereby safeguarding stored goods and marking ownership (Krzyszkowska Reference Krzyszkowska2005, 46–52). This practice integrated seals into economic activities, as documented by a growing body of evidence from mainland Greece and the Aegean. The stamping of pottery before firing during the EBA II period, as seen in the Therasia jar, represents another occasional use of seals that deserves special attention (Aruz Reference Aruz, Ferioli, Fiandra, Fissore and Frangipane1994, 213–14; Reference Aruz2008, 23–5; Krzyszkowska Reference Krzyszkowska2005, 52–6; Wilson Reference Wilson, Macdonald, Hatzaki and Andreou2015). Some stamp impressions likely served purely decorative purposes, as seen in examples stamped around the rims of hearths and pithos bands (Wiencke Reference Wiencke1969; Younger Reference Younger and Matz1974) or on the bodies of Cycladic vases, where repeated stamp impressions are combined with incised decorative patterns (cf. the stamped pyxis CMS I Supp., no. 172 from Chalandriani on Syros; Bossert Reference Bossert1960, 12, fig. 11, 13, fig. 12). Roller impressions on hearths and large pithoi, while also decorative, have been associated with itinerant craftsmen (Krzyszkowska Reference Krzyszkowska2005, 55). At Agia Irini, stamp impressions on hearths have been interpreted as symbolic markers, possibly signifying individuals or family units within the community (Wilson Reference Wilson, Macdonald, Hatzaki and Andreou2015, 173). Another practice involved stamping pierced cubic objects, identified as loom-weights, which are known from Skarkos on Ios (CMS V Supp. 3, nos 169–74; Marthari Reference Marthari, Meller, Gronenborn and Risch2018, 189–91), Palamari on Skyros (Parlama Reference Parlama, Simantoni-Bournia, Lemou, Mendoni and Kourou2007, 38, fig. 18:1), Lerna and Crete (Krzyszkowska Reference Krzyszkowska2005, 52; Reference Krzyszkowska and Ulanowskaforthcoming).

Stamping the handles of storage and transport jars, while infrequent, may have held special significance and could be linked to the tradition of potters’ marks.Footnote 34 Known examples of stamped vessel handles, necks and rims in the Aegean come from several sites (Fig. 1), including Skarkos II on Ios with fewer than a dozen examples (Marthari Reference Marthari, Meller, Gronenborn and Risch2018, 191, fig. 40), Poliochni on Lemnos (CMS I Supp., no. 170; CMS V Supp. 3, nos 212, 213), Chalandriani and Kastri on Syros (CMS I Supp., nos 171–2; CMS XI, no. 121), Markiani on Amorgos (CMS V Supp. 3, nos 45, 47, 48), Skotini Cave at Tharrounia on Euboea (CMS V Supp. 1B, no. 351), Agia Irini on Keos (CMS V.2, nos 458, 460, 467, 475), Palamari Phase I on Skyros (Parlama Reference Parlama, Simantoni-Bournia, Lemou, Mendoni and Kourou2007, 38, fig. 18:3), Mikro Vouni on Samothrace (CMS V Supp. 3, no. 342) and Troy (CMS V Supp. 1B, no. 479). The jar handle from Therasia, stamped by two different seals, adds to these examples, documenting the practice of dual stamping in an EC II context.

Stamp impressions on the handles and bodies of jars can be traced back to the Syro-Levantine region during the Eneolithic and the Early Bronze Age (Aruz Reference Aruz2008, 23). On Crete, seals and direct object sealings are documented in EM II contexts,Footnote 35 but evidence of stamped pottery does not appear until later, during the MM I period.Footnote 36 Stamped impressions on vessels are primarily a Protopalatial phenomenon, with examples from sites in eastern Crete such as Malia, Myrtos-Pyrgos, Palaikastro, Petras and Gournia.Footnote 37 The later appearance of stamped handles on Crete further supports the non-Cretan origin of the seal-impressed jar from Therasia, as indicated by the petrographic analysis.

The Therasia vessel likely originates from the Cycladic region and was imported to Koimisis. This conclusion is supported by the petrographic analysis, which points to a probable Naxian provenance or potentially another Cycladic island with lithologies ranging from granite to granodiorite. The stylistic and iconographic analysis of impression THS.2 further supports a Cycladic origin. Additionally, the granite–granodiorite, green amphibole-rich fabric of the stamped Therasia jar is not unique. It has also been documented at Akrotiri, where it was used primarily for cooking vessels, and less frequently for storage pots, and is considered to be Naxian in origin (Müller Reference Müller2009, 67–70; cf. ‘Petrographic Analysis of the Seal-Impressed Fragment’ above). While it is possible that THS.1 was stamped with a seal imported to the Cyclades, the probable Naxian origin of the jar, the likely Cycladic provenance of impression THS.2 and the association of THS.1 with a multi-facial seal – a type documented in both the Cyclades and the Aegean – strongly support the conclusion that both the stamped vase and the seal impressions are of Aegean, likely Cycladic, origin.

Regarding the meaning of stamping vessels before firing, O. Krzyszkowska (Reference Krzyszkowska2005, 52) suggests that such impressions could be related ‘to ownership or origin of the vessel or the vessel’s contents’, while D.E. Wilson (Reference Wilson, Macdonald, Hatzaki and Andreou2015, 174) argues for the symbolic use of seal stamping as a social marker of identity. Similarly, M. Marthari (Reference Marthari, Meller, Gronenborn and Risch2018, 191), in discussing the rare practice of seal-stamped pottery at Skarkos II, supports this interpretation for both seal-stamped pottery and pierced weights. J. Aruz (Reference Aruz2008, 24–5), while acknowledging the unclear interpretation of this practice, points to the Cycladic impression on Aegean ware from Troy IIb as potential evidence of commerce involving commodities that required some form of identification or control. J. Weingarten (Reference Weingarten, Macdonald, Hatzaki and Andreou2015, 73–4), noting the unsystematic nature of this practice on Minoan stamped vases and the occasional carelessness in stamping or covering impressions with wash, concludes that ‘it is hard to imagine that the seals were meant to indicate the craftsman, product, origin or destination of the few seal-impressed jars’. Instead, she proposes that the practice originated in the pottery workshop before firing and that ‘the seal(s) belonged to the potter and/or family or workshop’. Since the practice was rare, and stamped vases were the exception, she argues that ‘the pots are marked because they will be put to some special use’.

In the case of the Therasia impressions, if vessel stamping was intended to identify the production of a specific workshop, we would expect to find multiple vessels of the same imported fabric at Therasia and Akrotiri stamped with impressions similar to THS.1 and THS.2, which is not the case.Footnote 38 Thus, the stamping and identification of the vase are not linked to mass production or a large-scale import of jars to Therasia and/or Akrotiri but may have had a special meaning or purpose, as J. Weingarten (Reference Weingarten, Macdonald, Hatzaki and Andreou2015) suggests. This may indicate a more confined production or an association with a specific authority or individual, highlighting the need to make a particular vase recognisable. Insights can be drawn from vessels from the Old Assyrian Period, which bear signs similar to those found on seals from the eighteenth/seventeenth century BC. These may indicate the names of owners (Waal Reference Waal2012, 298–300). In Old Assyrian debt notes, the amounts of grain or barley due were to be measured in specific vessels belonging to the creditor, reinforcing the idea that certain vessels needed to be distinctive and marked with their owner’s name (Waal Reference Waal2012, 300). Similarly, a seal bearing an inscription and its impression on a jar handle could have been used to make a specific vase recognisable, serving the function of identifying the individual or authority to whom it belonged. Notably, on the Therasia jar, the impression that is most clearly ‘read’ from above on the upper part of the handle is THS.1, suggesting that the positioning and visibility of this specific impression were intentional.

The shape of the vessel to which the handle belonged, along with its intended use,Footnote 39 may have a bearing on the interpretative meaning of the seal impressions. Since the Therasia jar bearing the impressions is likely of Naxian origin, these impressions may denote the origin of either the vase or its content. Within the context of Koimisis, the impressions may have served as symbols of provenance and/or possibly of ownership of the vase. These marks may have functioned as emblems rather than signs meant to be properly ‘read’ on the vase’s handle. Given that the site of Koimisis has not provided any evidence of complex administrative functions, the meaning of the impressions should be understood in relation to the primary context of the vase at its place of origin or within the framework of Aegean maritime networks, where vases and commodities circulated.

The practice of dual stamping, where two different seals are applied to a single object, as observed on the Therasia jar handle, is also documented in other contexts, such as direct object sealings at Lerna.Footnote 40 In the case of the Therasia jar, one seal impression may be linked to the potter or manufacturer, akin to the use of potter’s marks on vase handles, while the other might indicate ownership or the origin of the vase. This is particularly relevant in the context of pottery circulation and the emergence of maritime transport jars in the EBA Aegean (Day and Wilson Reference Day, Wilson, Demesticha and Knapp2016). However, the absence of widespread vessel stamping complicates the idea of a systematic sphragistic function associated with pottery circulation. Nevertheless, the dual stamping on the Therasia jar, combined with the use of a seal bearing signs for identification – whether indicating ownership, control over the jar’s contents or marking its origin and/or manufacture – reflects a significant and sophisticated use of seals in the Cyclades during the EBA II period.

The Therasia stamp impression and early Aegean script development

The evidence from Koimisis on Therasia is less tangible, with the impression THS.1 constituting a unique example from the EBA II period. While THS.1 does not confirm the existence of a developed proto-script, it highlights developments related to the broader process of the emergence of writing in the EBA Aegean. The consistent arrangement of signs across all three faces of the seal associated with THS.1 suggests a deliberate and standardised configuration, rather than a random or accidental one. The sequence of uniformly sized signs, arranged linearly on the seal, may correspond to elements of speech, potentially conveying meaning as part of an early writing or notation system.

However, the precise nature of these signs remains unclear. It is uncertain whether they served an ideographic or logographic function, conveyed phonetic values or were linked to a specific language. Alternatively, they could represent sematographic or non-glottic symbols within a visual communication system. They do not appear to imitate any known script. The sequence of signs engraved on seals likely held specific symbolic functions, possibly related to identification, prestige or expressions of authority, rather than the systematic transcription of language. These may have represented personal names or broader conceptual markers during an early phase of script development. Such systems may not have required grammar, phonetic endings or a direct representation of spoken language.Footnote 41 Early writing systems often differed significantly from their later, more standardised counterparts, with the transcription of speech emerging as a secondary process (Schmandt-Besserat Reference Schmandt-Besserat1992, 139–54; Regulski Reference Regulski2014; Stauder Reference Stauder and Polis2023, 34). In this context, THS.1 could represent a preliminary stage in the development of a more complex communication system, rooted in the socio-economic and cultural practices of the Aegean during the EBA II period.

When examining comparable practices in the Aegean related to the emergence of possible ‘writing’, there is some controversial evidence, such as the EC II impression on a hearth rim from Agia Irini in Keos (CMS V.2, no. 478; Wilson Reference Wilson1999, 56, no. II-422, pl. 59:II-422). Younger (Reference Younger and Matz1974, 169–70 and figs 75–6) interpreted this impression as the earliest example of a ‘hieroglyphic’ seal in the Aegean, though its status as a true hieroglyphic seal remains debated (Aruz Reference Aruz2008, 36). The placement of signs in an ordered sequence on this impression may suggest an attempt to imitate script.

Beyond this debated example, the earliest evidence of possible writing in a non-palatial context in the Aegean comes from seals bearing signs of the so called ‘Archanes Script’ (Fig. 11), dating to the late Prepalatial period (Grumach and Sakellarakis Reference Grumach and Sakellarakis1966; Perna Reference Perna, Nakassis, Gulizio and James2014, 252–3; Decorte Reference Decorte2018a; Ferrara, Montechi and Valério Reference Ferrara, Montechi and Valério2021; Karnava Reference Karnava and Bennet2021, 245–50). We use the term ‘Archanes Script Group’ in a broader sense to refer to a style-complex of the late Prepalatial period that, in addition to script signs, includes pictorial motifs such as schematised quadrupeds, standing figures, leaves, spiral ornaments and individual symbols later associated with the Cretan Hieroglyphic script (Fig. 11bc; Sbonias Reference Sbonias1995, 107–13; Krzyszkowska Reference Krzyszkowska2005, 70–2; Decorte Reference Decorte2018a; Reference Decorte, Ferrara and Valério2018b). The term ‘Archanes Script’ or ‘Archanes Formula’ (Grumach and Sakellarakis Reference Grumach and Sakellarakis1966; Perna Reference Perna2019, 54–6; Ferrara, Montechi and Valério Reference Ferrara, Montechi and Valério2021; Karnava Reference Karnava and Bennet2021, 245–6) specifically refers to distinct sign sequences (Fig. 11de), associated with the later Cretan Hieroglyphic and Linear A scripts (Karnava Reference Karnava2000, 195–7; Anastasiadou Reference Anastasiadou2016, 171–4; Decorte Reference Decorte2018a, 367–8). Considering the nature of the signs, there is ongoing debate about whether the ‘Archanes Script’ and the limited repertoire of signs engraved on seals constitutes a true script, capable of expressing a range of words through syllabic signs that might be considered ancestral to Cretan Hieroglyphic (Krzyszkowska Reference Krzyszkowska2005, 70–2; Ferrara Reference Ferrara2015; Decorte Reference Decorte, Ferrara and Valério2018b, 36–42; Perna Reference Perna2019; Karnava Reference Karnava and Bennet2021). It also remains uncertain whether the pictorial and decorative motifs on the seal faces had any lexical value (Ferrara Reference Ferrara2018; Karnava Reference Karnava and Bennet2021, 247–9).

Fig. 11. Seal of the Archanes Script Group from Moni Odigitria on Crete (Sbonias Reference Sbonias, Vasilakis and Branigan2010, pls 61:S35, 70:S35).

Although the precise relation between the Archanes Script and the later Cretan writing systems remains unclear, some common elements can be identified between seals of the Archanes Script Group and Protopalatial seals bearing Cretan Hieroglyphic inscriptions. These include: i) the use of multi-facial seals to convey meaning through combinations of pictorial, decorative or abstract motifs – a feature evident in both the Archanes Script Group and the three- and four-sided prisms of the Protopalatial period with hieroglyphic inscriptions (Anastasiadou Reference Anastasiadou2016, 162–7); and ii) the presence of inscriptions on one or more faces, with the ‘Archanes Formula’ serving as a link between Prepalatial and Protopalatial seals in the context of the origins of the Cretan Hieroglyphic script (Decorte Reference Decorte2018a, 367–8; Kanta, Palaima and Perna Reference Kanta, Palaima and Perna2022, 69–71).

The use of seals as early media associated with development of writing in the Aegean establishes a shared link with impression THS.1 from Therasia. Multi-faciality in seal design also emerges as a common factor, as both the Archanes Script Group and the Cretan Hieroglyphic traditions demonstrate structured and standardised arrangements of script signs and motifs across different faces. The stamp impression THS.1 from Therasia, originating from a multi-facial seal, shows some parallels with these practices. In both traditions, signs were arranged linearly, sometimes separated by other signs or supplemented by additional motifs with a possible sematographic significance (Decorte Reference Decorte, Ferrara and Valério2018b, 39). In the case of THS.1, the possibility that its motifs function as signs within a system of communication – or even as part of an emerging writing or notation system – is supported by these parallels. However, the arrangement of signs into specific, recognisable sequences or sign-groups, as seen in later scripts, is not present in the Therasia impression. Each of the three fields of THS.1 displays different sign sequences. While some motifs on THS.1 may resemble signs from the Archanes Script, these similarities do not necessarily indicate a direct genetic relationship between the Therasia impression and later Aegean scripts. Rather, they suggest shared elements in the broader concepts and processes of script development in the Aegean during the late third and early second millennia BC.Footnote 42

To understand the socio-political background and possible external stimuli behind the emergence of writing, it is important to consider the broader context of script formationFootnote 43 and the interconnections between the Aegean, Anatolia, the Near East, and Egypt, particularly in relation to seal shapes, motifs, and sphragistic practices. Weingarten (Reference Weingarten1997) suggested that the introduction of sealing practices at Lerna IIIC might be linked to a trade route between western Anatolia and Lerna. This connection to Anatolia is further supported by the presence of fortifications with bastions at sites like Liman Tepe and Bakla Tepe in western Anatolia, as well as Lerna, Palamari and Kastri in mainland Greece and the Aegean, which have been attributed to West Anatolian international contacts (Şahoğlu Reference Şahoğlu2005; Kouka Reference Kouka2008, 318–19). However, tracing the origins of an Aegean script within this context is problematic, as Anatolian hieroglyphs are generally considered to have been invented in the second half of the second millennium BC (Mora Reference Mora1991), though some suggestions point to an earlier origin (Waal Reference Waal2012). Despite these debates, it seems unlikely that Aegean script directly originated from Anatolian traditions. Instead, stronger influences may have come from the Near East and Egypt, where certain seal types found in the Aegean have close parallels, suggesting occasional contact with developed writing systems. For instance, rectangular buttons with pierced grips show affinities with Anatolian and Syrian forms (Aruz Reference Aruz2008, 36), while pyramidal seals with protruding grips resemble Egyptian types (Aruz Reference Aruz2008, 35). These seal types, documented in the Aegean, could be linked to the originating seals of the Therasia impressions (cf. discussion above). Additionally, a loop-handled green stone cylinder seal, possibly from Amorgos (CMS VI.1, no. 1), is thought to imitate Syro-Cilician stamp-cylinders (Aruz Reference Aruz2008, 35–6), while a cylinder impression from Markiani on Amorgos (CMS V Supp. 3, no. 48) further suggests external influences on Aegean seal-making practices. Moreover, the resemblance of Sign C3 from THS.1 to the semantic complement of ‘walking legs’ in Egyptian writing suggests that this influence may have extended beyond seal shapes to the imitation of motifs as well.

In conclusion, the evidence from Koimisis on Therasia is less tangible and does not definitively support the existence of a proto-script in the Aegean during the EBA. However, it highlights developments linked to script formation, particularly in relation to the use of seals as the earliest medium for the emergence of early writing in the Aegean. Summarising the characteristics of the Therasia impression that support its interpretation as an inscription, we propose the following: i) the arrangement of consecutive signs in a coherent sequence, where symbols are juxtaposed rather than appearing as isolated motifs,Footnote 44 implying a structured and meaningful order; ii) the consistent placement of symbols across all three faces of the seal associated with THS.1, suggesting a degree of standardisation and repetition in structure; and iii) the combination of abstract signs and stylised iconic signs within the sequences, marking a departure from purely figurative or ornamental seal motifs. When compared with later Bronze Age script systems, the signs of the Therasia impression, while displaying some notable similarities, do not align with any established corpus of script signs from Eastern Mediterranean writing systems. However, the characteristics of THS.1 above, along with formal resemblances to seals bearing signs from the Archanes Script and Cretan Hieroglyphic traditions, suggest that the Aegean may have been undergoing a process of script formation as early as the developed EBA II period. This interpretation supports the idea that the evolution of complex communication systems was underway in the Aegean, in association with the marking of identity, control of commodities and increasing social complexity, particularly within the context of glyptic practices (Salgarella Reference Salgarella2021, 68–71). A continuation of this process may be later observed with the so called ‘Archanes Script’ (Decorte Reference Decorte, Ferrara and Valério2018b, 39–42), representing another step along the path to script formation in the Aegean.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS