Introduction

Following Morris’s (Reference Morris2003) notion of ‘Mediterraneanisation’—a process that shaped the Mediterranean in ways somewhat analogous to globalisation—some scholars began to revisit preconceptions surrounding the Mediterranean in the first millennium BC, including the nature of relationships between coastal and inland areas (e.g. Hodos Reference Hodos2020; López-Ruiz Reference López-Ruiz2022; Riva & Grau-Mira Reference Riva and Grau-Mira2022; Blanco-González et al. Reference Blanco-González, Padilla Fernández and Dorado-Alejos2023). A critical reappraisal of the Late Iron Age (fourth–first centuries BC) archaeology from El Cerrón (Illescas, Toledo), in the Middle Tagus Valley (ancient Carpetania) of central Iberia, fits within this scholarly trend.

Both Strabo, writing in the first century BC (Geography 3.3.1; Jones Reference Jones1923: 61–65), and Pliny the Elder, in the first century AD (Natural History 3.3.25; Rackham Reference Rackham1942: 22–23), distinguish Carpetania from Celtiberia, to the north-east of the peninsula. However, in academic literature, Carpetania is often examined through the lens of surrounding, better-known districts—the Vaccaean region, Vettonia and Celtiberia—suggested to exhibit a higher degree of power centralisation and social stratification (Urbina Martínez Reference Urbina Martínez1998; De Torres Rodríguez Reference De Torres Rodríguez and Baquedano Pérez2014; Ruiz Zapatero Reference Ruiz-Zapatero and Baquedano Pérez2014; Álvarez Sanchís & Ruiz Zapatero Reference Álvarez Sanchís, Ruiz Zapatero, Romankiewicz, Fernández-Gótz, Lock and Buchsenschutz2019). This has led to a traditional view of Carpetania as a marginal, heterarchical territory where cultural development can be explained through acculturation, imitation and diffusionism (Blasco Bosqued & Blanco García Reference Blasco Bosqued, Blanco García and Baquedano Pérez2014). Although Polybius (The Histories 3.14.2; Paton et al. Reference Paton, Wallbank and Habicht2010: 36–37), writing in the second century BC, described the Carpetanians as “the strongest tribe in the district” during the Hannibalic Wars of the late third century BC, El Cerrón was initially interpreted as a ‘Celtiberian hillfort’ based on its “structures and pottery evidence” (Valiente Cánovas & Balmaseda Muncharaz Reference Valiente Cánovas and Balmaseda Muncharaz1981: 217; see below). Other scholars link the Carpetanians to either the Celtic peoples of the Meseta Central or the Southern Iberian peoples (Blasco Bosqued & Blanco García Reference Blasco Bosqued, Blanco García and Baquedano Pérez2014; Ortega Ruiz Reference Ortega Ruiz and Baquedano Pérez2014; Álvarez Sanchís & Ruiz Zapatero Reference Álvarez Sanchís, Ruiz Zapatero, Romankiewicz, Fernández-Gótz, Lock and Buchsenschutz2019).

The site of El Cerrón is an atypical ‘Celtiberian hillfort’ for three reasons: the presence of three overlapping—possibly sacred—buildings of non-Celtic tradition; Mediterranean and northern Iberia elite imports; and a decorated terracotta relief showing a ‘Mediterraneanising’ taste. By critically re-evaluating the published evidence for elite artefacts and architecture, and their contexts of discovery at the site, this article aims to shed new light on Carpetanian elite identity and agency in the Late Iron Age.

The site of El Cerrón (Illescas, Toledo, Spain)

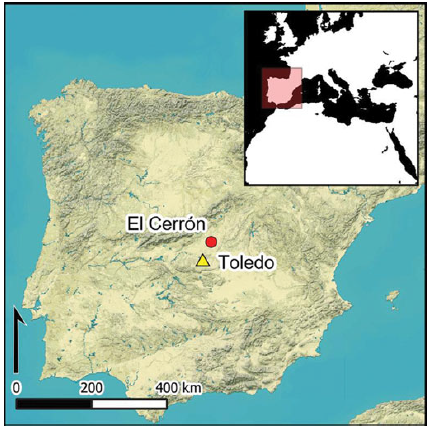

Located in the southern part of the Meseta Central, the site of El Cerrón sits upon a small oval-shaped mound (about 1ha) rising between 2m and 8m above the surrounding area (Balmaseda Muncharaz & Valiente Cánovas Reference Balmaseda Muncharaz and Valiente Cánovas1979: 159). Though investigated over multiple field seasons (in 1977, 1979–1980, 1982, 1985, 1989, 2005–2006), excavation typically focused on small trenches (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The site of El Cerrón (Illescas, Toledo, Spain): A) location in central Iberia along the river Tagus valley (red dot); B) map of the mound showing the location of trenches; the relief was discovered in the trench marked in red (adapted from Valiente Cánovas Reference Valiente Cánovas1994: fig. 4) (figure by authors).

Valiente Cánovas (Reference Valiente Cánovas1994) relies on material culture, especially pottery, and three radiocarbon dates from charcoal (CSIC-568: 2100±50 BP, 351 cal BC–cal AD 22; CSIC-569: 2160±50 BP, 362–53 cal BC; CSIC-570: 2280±50 BP, 413–197 cal BC; Alonso Reference Alonso and Valiente Cánovas1994: 205—dates subsequently modelled in OxCal v.4.4.4 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2021), using IntCal20 calibration curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer2020)) to suggest three continuous phases of occupation: the emergence of the settlement at the beginning of the fourth century BC (first phase), and its continuation through the mid and late fourth century BC (second phase) into the third and the early second centuries BC (third phase). Structures found near the site suggest a more widespread occupation of the area in the third phase (Martín Bañón Reference Martín BaÑón, Madrigal Belinchón and Perlines Benito2010; see Figure 1). After an extended period of abandonment, the site was resettled during the Middle Ages (twelfth–thirteenth centuries AD) (Valiente Cánovas & Balmaseda Muncharaz Reference Valiente Cánovas and Balmaseda Muncharaz1981: 217). Although radiocarbon dates from charcoal must be viewed with caution (e.g. potential for earlier estimates due to the burning of old timber—the old-wood effect; Schiffer Reference Schiffer1986), published material culture seems to confirm the proposed Late Iron Age occupation phases (Balmaseda Muncharaz & Valiente Cánovas Reference Balmaseda Muncharaz and Valiente Cánovas1979; Valiente Cánovas & Balmaseda Muncharaz Reference Valiente Cánovas and Balmaseda Muncharaz1981, Reference Valiente Cánovas and Balmaseda Muncharaz1983; Valiente Cánovas Reference Valiente Cánovas1990, Reference Valiente Cánovas1994, Reference Valiente Cánovas, Sanz Gamo, Abad Casal and Gamo Porras2021).

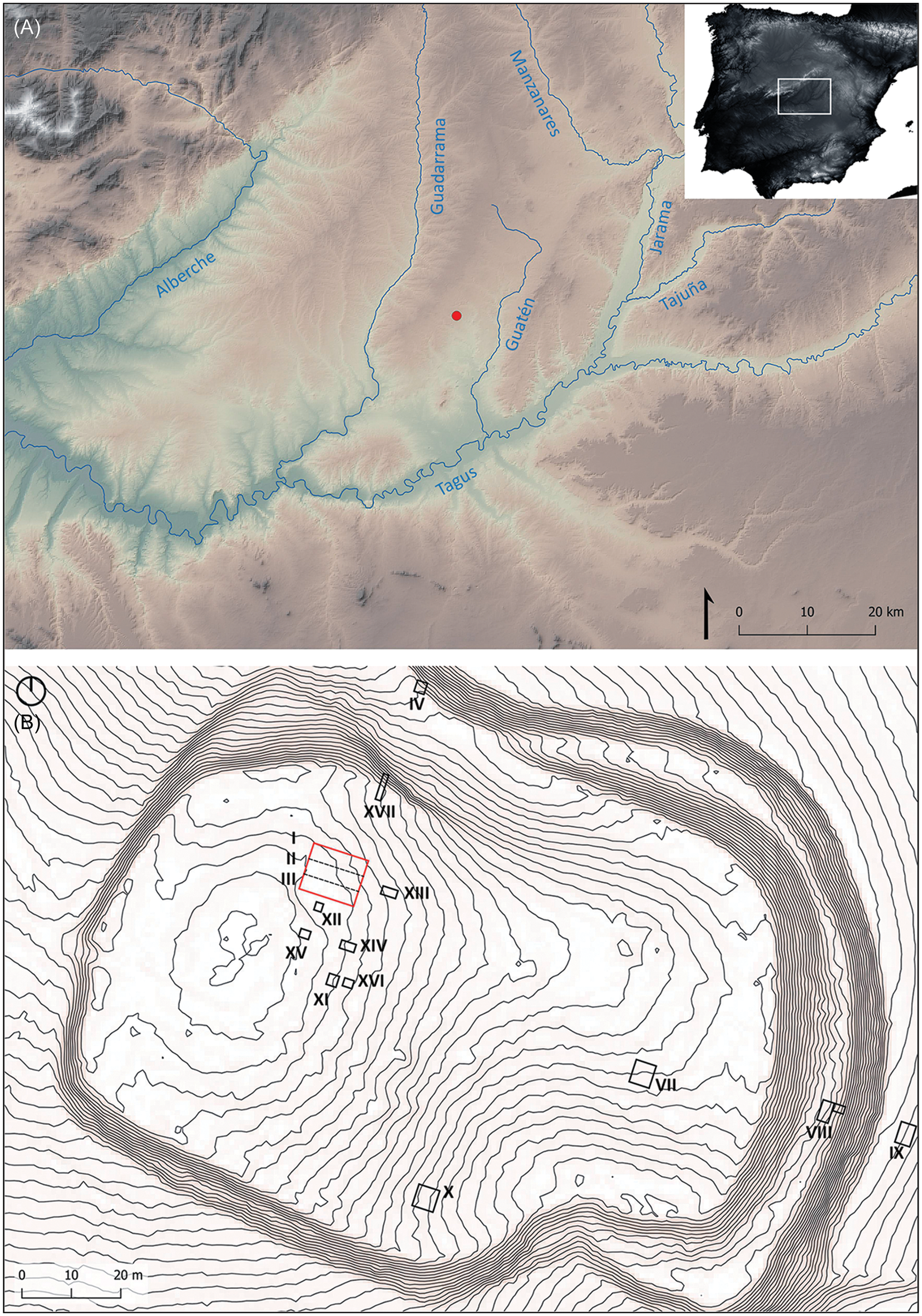

A few Late Iron Age structures, only partially preserved, were found during the small-scale excavations at El Cerrón; these followed the local building tradition, with stone foundations and mudbrick walls (Valiente Cánovas & Balmaseda Muncharaz Reference Valiente Cánovas and Balmaseda Muncharaz1981: 215). In the north-west sector of the site, close to the top of the mound, one building (Structure 2) contained a bench-mounted terracotta relief. The prominent location of Structure 2 may indicate its social and/or political importance, particularly as excavation revealed that it was preceded and superseded by similar building structures; the three structures linked to the three phases of occupation (Valiente Cánovas & Balmaseda Muncharaz Reference Valiente Cánovas and Balmaseda Muncharaz1981: 215–17). The earliest structure (Structure 1) had an east–west orientation, a rectangular layout (8.6 × 4.8m), stone foundations and adobe walls (Valiente Cánovas & Balmaseda Muncharaz Reference Valiente Cánovas and Balmaseda Muncharaz1981: 216–17; Figure 2). The floor was made of compact clay and the presence of postholes suggests wooden columns; a rectangular hearth occupied the central area (Valiente Cánovas & Balmaseda Muncharaz Reference Valiente Cánovas and Balmaseda Muncharaz1981: 217). The lack of an eastern wall might indicate that it was a lean-to structure (Valiente Cánovas Reference Valiente Cánovas1994: 45). A fire event seems to have marked the end of the use of Structure 1 (Valiente Cánovas & Balmaseda Muncharaz Reference Valiente Cánovas and Balmaseda Muncharaz1981: 216–17), and Structure 2 was built on top soon after.

Figure 2. Sections and suggested reconstructions of Structures 1 to 3 (sections after Valiente Cánovas Reference Valiente Cánovas1994: 184–85, figs. 63 & 64; Almagro-Gorbea & Berrocal-Rangel Reference Almagro-Gorbea and Berrocal-Rangel1997: 574, fig. 3; reconstructions by F. Checa Valles).

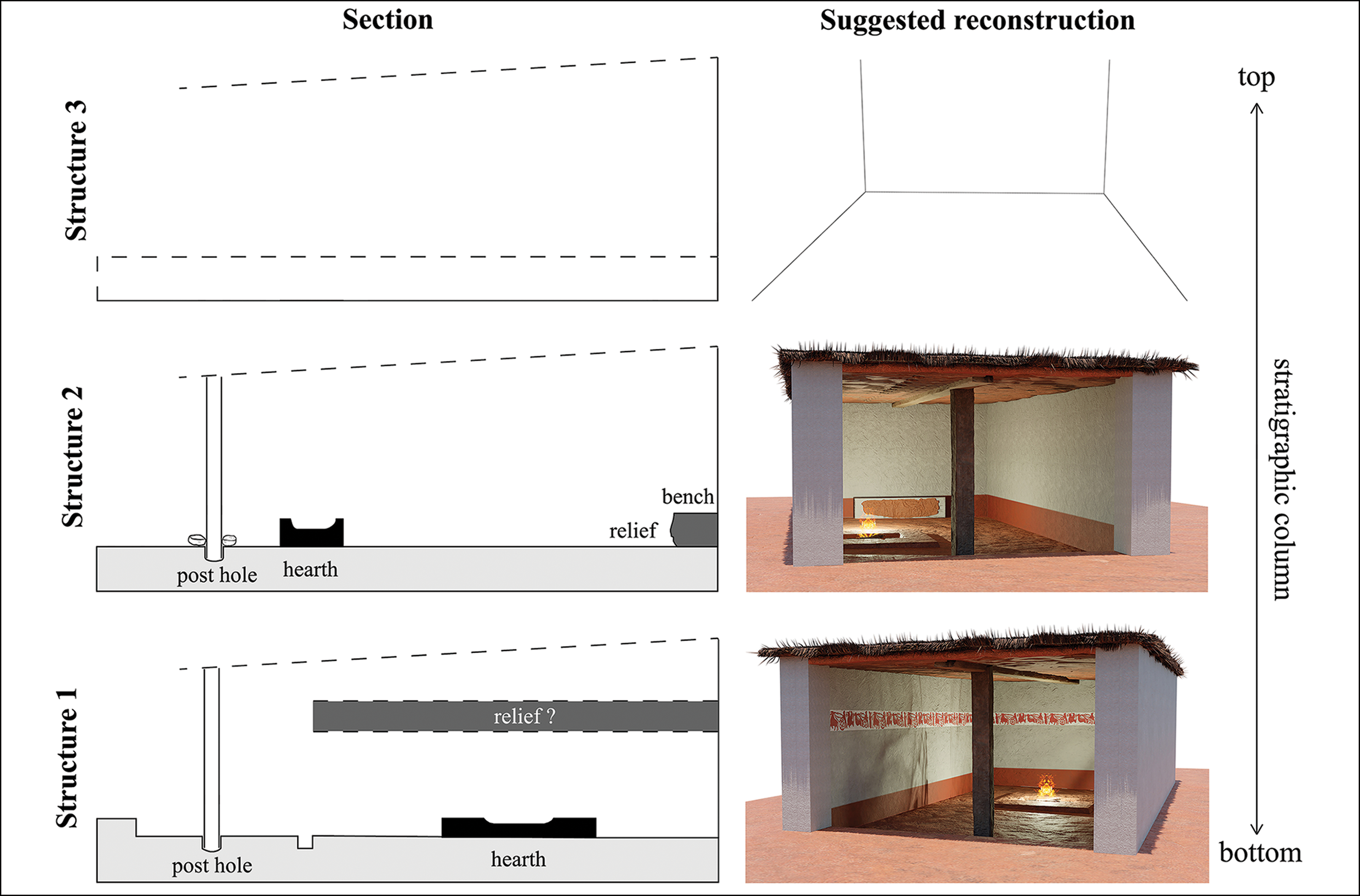

Structure 2 had an orientation (east–west), layout and dimensions (9 × 4.8m) similar to Structure 1 and was also probably a lean-to building (Valiente Cánovas Reference Valiente Cánovas1994: 45, 184; Figure 2). Postholes were dug into the floor but, this time, stone wedges kept the wooden columns in place (Valiente Cánovas & Balmaseda Muncharaz Reference Valiente Cánovas and Balmaseda Muncharaz1981: 216). In the south-east part of the structure, a clay hearth and pottery sherds were unearthed, as well as metal objects and animal bones (Balmaseda Muncharaz & Valiente Cánovas Reference Valiente Cánovas and Balmaseda Muncharaz1981: 194). Remnants of white (limestone) and red paint may have been preserved on the walls and floors of Structures 1 and 2 (Valiente Cánovas Reference Valiente Cánovas1990: 331). The terracotta relief discovered in this building fitted within a continuous mudbrick bench/altar attached to the western wall and was covered by wall and roof debris (Balmaseda Muncharaz Reference Balmaseda Muncharaz and Valiente Cánovas1994: 171–72; Figure 3). The end of the use of this structure is also marked by a fire event (Valiente Cánovas & Balmaseda Muncharaz Reference Valiente Cánovas and Balmaseda Muncharaz1981: 216) and a third structure (Structure 3) with a similar layout and dimensions was built on top. No archaeological finds are associated with this final structure (Valiente Cánovas & Balmaseda Muncharaz Reference Valiente Cánovas and Balmaseda Muncharaz1981: 215–16; see Figure 2).

Figure 3. Colour and greyscale images of the relief shortly after its discovery in 1979 (after Valiente Cánovas & Balmaseda Muncharaz Reference Valiente Cánovas and Balmaseda Muncharaz1981: 53, fig. 1).

The function of Structure 2 has been debated since its discovery. It has been interpreted as a house (Valiente Cánovas & Balmaseda Muncharaz Reference Valiente Cánovas and Balmaseda Muncharaz1981: 217), a place of worship and pilgrimage (Valiente Cánovas Reference Valiente Cánovas, Sanz Gamo, Abad Casal and Gamo Porras2021: 268) or a shrine (Almagro-Gorbea & Berrocal-Rangel Reference Almagro-Gorbea and Berrocal-Rangel1997: 573, 577–82; Almagro-Gorbea & Moneo Rodríguez Reference Almagro-Gorbea and Moneo Rodríguez1999: 55–56). Similarities in the mound-top location, rectangular layout, internal spatial organisation and associated finds permit close comparison with the shrine at Castrejón de Capote (Higuera la Real, Badajoz; see Figures 1, 2 & 4)—located about 400km southwest of El Cerrón and dated to the mid-second century BC—suggesting that the interpretation of Structure 2 as a shrine is perhaps most probable.

Figure 4. A) Layout of the hillfort at Castrejón de Capote with the location of the shrine highlighted; B & C) stamps depicting griffins/Pegasus found within the shrine; and D) plan of the shrine of Castrejón de Capote and the distribution of finds (figure by authors; A & D after Berrocal-Rangel Reference Berrocal-Rangel, Gillies and Harding2006: 19, fig. 2; photographs B & C by G. Cabanillas de la Torre).

Terracotta relief: a critical discussion of the decorative motif

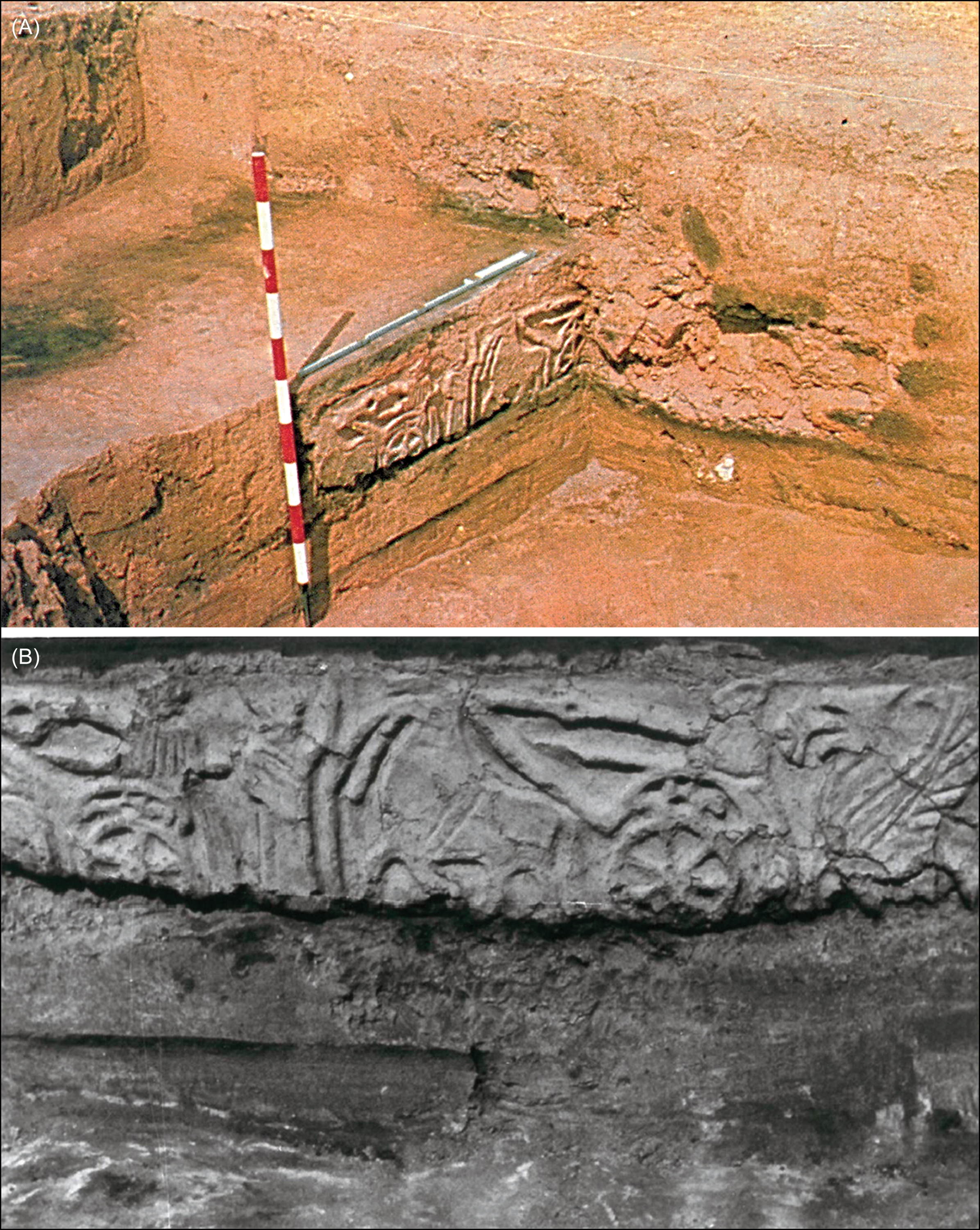

The terracotta relief discovered within Structure 2 appears to be a fragment (1.35 × 0.33m; Figure 5A) of a larger composition. The scene shows a parade proceeding from right to left, with the rightmost figure a griffin, depicted standing or in movement with a possibly floral motif (a lotus flower?) stemming from its open mouth (Figure 5). Left of the griffin is the first of two, probably male, charioteers, each wearing oval-shaped headgear and a long dress, the lower part seemingly decorated with a herringbone pattern in the first instance and longitudinal lines in the second. Each rides a two-wheeled chariot, with six spokes per wheel and part of the forecarriage visible above the wheels. The charioteers hold reins that are connected by rings to the horses’ bits; the draught pole is visible below the reins. The first horse is represented as a chubby four-legged animal with a girth strap crossing its back and belly, and two oblong floral elements sprouting from its mouth (possibly part of the horse’s harness); the horse to the left of the scene is incomplete, the girth strap is its only visible decoration. A second horse probably also pulled each chariot, but is not visible in the relief due to the lack of perspective. Between the two chariots is a standing human figure wearing a long tunic/cloak—probably originally decorated—and pointed headgear. The preserved scene ends with the second horse described above.

Figure 5. The relief from Structure 2 at El Cerrón, comparing a digital photograph (A), a filtered photograph (B) and an artistic rendering (C) (Museo de Santa Cruz de Toledo; Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte; inventory number: CE23580; photograph by J. Blánquez Pérez; drawing by P. Sánchez de Oro).

Parallels for the scene at El Cerrón are found on the Mediterranean coast of the Iberian Peninsula (Vidal de Brandt Reference Vidal de Brandt1975; Le Meaux Reference Le Meaux2010; Figure 6). The griffin is a frequent decorative motif in this area; the earliest example identified to date being the sixth-century BC stone relief at Pozo Moro (Almagro-Gorbea Reference Almagro-Gorbea1983: 204, pl. 23a). Griffins are found on sculptures at the cemetery of Cerrillo Blanco at Porcuna (Figure 7A) and the sanctuary of El Pajarillo at Huelma, both in Jaén (Figure 7B), and at the sites of Redován and La Alcudia in Alicante (Figure 7C); all dated between the late sixth and the early fourth centuries BC (Izquierdo Peraile Reference Izquierdo Peraile, Izquierdo and Le Meaux2003: 268). The fourth-century BC stone larnax found at the cemetery of Tútugi in Galera also shows a griffin (Figure 7D; Blázquez Martínez Reference Blázquez Martínez1957: fig. 2). Griffins are further attested on pottery vessels: on a fifth-century BC urn held at the Museum of Cabra in Córdoba (Figure 7E; Blánquez Pérez & Belén Deamos Reference Blánquez Pérez, Belén Deamos and Blánquez Pérez2003: 100–101, 130–37), and on the so-called ‘winged carnassiers (carnivores)’ found in the south-east of the Iberian Peninsula that date to the end of the second and the beginning of the first century BC (Figures 6 & 7F; Uroz Rodríguez Reference Uroz Rodríguez2007).

Figure 6. Distribution map showing parallels for the motifs depicted on the relief found at El Cerrón (figure by authors).

Figure 7. Selected comparisons to the relief of El Cerrón: A) the ‘Griphomaquia’ of Cerrillo Blanco, Porcuna, Jaén (https://ceres.mcu.es/pages/Viewer?accion=4&Museo=&AMuseo=MJ&Ninv=CE/DA01683/E08&txt_id_imagen=3); B) the griffin of El Pajarillo, Huelma, Jaén (https://ceres.mcu.es/pages/Viewer?accion=4&AMuseo=MJ&Ninv=DJ/DA02923/06); C) the griffin from La Alcudia (LA-688), Elche, Alicante (https://web.ua.es/es/laalcudia/las-piezas-que-hablan.html); D) the larnax from the cemetery of Tútugi, Galera, Granada (https://ceres.mcu.es/pages/Viewer?accion=4&Museo=MAN&AMuseo=MAN&Ninv=1940/27/GALER/T76/1A&txt_id_imagen=2&txt_rotar=0&txt_contraste=0); E) vessel from Cabra, Córdoba (Blánquez Pérez Reference Blánquez Pérez2002: 45, fig. 2); F) the kalathos from La Alcudia (Uroz Rodríguez Reference Uroz Rodríguez2007: pl. 1); G) the kalathos of Elche de la Sierra (Eiroa Reference Eiroa García1986: 77, fig. 2).

The kalathos of Elche de la Sierra, Albacete, dated to the late second century BC (Figure 7G; Eiroa GarcíaReference Eiroa García1986), provides a possible parallel for the parade scene, though in this instance characterised by the movement of goods, most probably gifts, including one horse and items transported on a two-wheeled cart. Yet, differences in the medium—a painted pottery vessel—and the date of the kalathos, as well as its possible funerary interpretation (Eiroa GarcíaReference Eiroa García1986: 84), mean that it is not a close parallel for the relief found at El Cerrón. Chariots pulled by horses are, however, well attested on Phoenician scarabs from the fifth–fourth centuries BC (Gubel Reference Gubel1988: 160–63, pls. XXVIIIb & XXXII; Boardman Reference Boardman2003: 81–82; Elayi & Elayi Reference Elayi and Elayi2014) that are also found in Spain (Boardman Reference Boardman1984: 49, nos. 80, 81, pl. XIV, nos. 80–88; Conde Reference Conde and Celestino Pérez2003: 237–40).

In the relief at El Cerrón, particular emphasis is given to the figure standing between the two charioteers. Valiente Cánovas and Balmaseda Muncharaz (Reference Valiente Cánovas and Balmaseda Muncharaz1981: 219; see also Balmaseda Muncharaz Reference Balmaseda Muncharaz and Valiente Cánovas1994) interpret this figure either as a female in the act of greeting the charioteer facing them or as a deity, characterised by their different dress and headgear compared to the charioteers (Balmaseda Muncharaz Reference Balmaseda Muncharaz and Valiente Cánovas1994: 231–32). The oblong feature held by the standing figure can be interpreted either as a spear or as a bâton the commandment (command staff). Bronze votive figurines with conical headgear are not uncommon in Iberian sanctuaries between the eighth century BC and the Roman period (Nicolini Reference Nicolini1969; Prados Torreira Reference Prados Torreira1992). Moreover, an enthroned deity with a spear is depicted on an early-fifth-century BC Phoenician scarab found at Alconchel de la Estrella at Cuenca, near El Cerrón (Almagro-Gorbea & Millán Martínez Reference Almagro-Gorbea and Millán Martínez2013). A female enthroned deity holding a spear is also depicted on a late-fifth/early-fourth-century BC stone box found in grave 76 at the cemetery of Galera in Granada (Chapa Brunet Reference Chapa Brunet, Pereira, Chapa Brunet, Madrigal, Uriarte and Mayoral2004: 247, fig. 3). Standing gods with a spear, or bâton the commandment, are also well documented on scarabs from Ibiza (Boardman Reference Boardman1984: 44–47, pls. XI–XIII, nos. 60, 62, 68–72). Culican (Reference Culican1960: 47–48) suggests that the spear can be linked to the gods Melqart and Baal, as documented in several Phoenician seals; notably, a temple dedicated to Melqart is found in Gadir, modern-day Cádiz (Mierse Reference Mierse2012: 288–90).

Discussion

The terracotta relief found in Structure 2 at El Cerrón may be the most inland example of ‘Mediterraneanisation’ found, to date, in the Iberian Peninsula (Figures 5 & 6). Its stratigraphic location and associated pottery sherds, including a fragment of Attic pottery (Figure 8A), indicate that the relief was probably housed in Structure 2 during the second phase of occupation at El Cerrón, between the mid and late fourth century BC (Valiente Cánovas Reference Valiente Cánovas1994). Nevertheless, the preservation of the relief itself and its location—fitted within the bench/altar made of mudbrick (see Figure 3)—suggests that it originally belonged to a larger composition and its presence in Structure 2 represents reuse. The full relief could originally have hung inside Structure 1 and, after the fire, the best-preserved section was retained and placed inside Structure 2, emphasising the continuity of place. It is also possible that the relief originally decorated an aristocratic residence—possibly located near Structure 2, though not yet identified—or a cultic place, similar to the terracotta plaques from Archaic (sixth–fifth centuries BC) Etruria and Latium in central Italy (Roth-Murray Reference Roth-Murray2007: 142), which depict elite activities (Roth-Murray Reference Roth-Murray2007: 139, 145). Although geographically distant, the complex scenes of elite activities shown on the Italic terracotta plaques—horse/cart races, banquets, processions/parades and assemblies (Roth-Murray Reference Roth-Murray2007: 145)—are similar to those depicted on the relief found at El Cerrón. Moreover, these plaques represent the only contemporaneous use of terracotta as a medium for such scenes, although this could reflect a preservation bias in the archaeological record of the Iberian Peninsula.

Figure 8. Imports and local imitations of exotica and Iberian products found at El Cerrón: A) Attic pottery, probably a kylix or a skyphos dated to the fourth century BC found in Trench I; B) Iberian imitation of a red-slip bowl found in Trench II; C) Iberian grey pottery unguentarium found in Trench II; D) glass bead found in the ploughsoil; E) bronze Iberian style ex-voto found in the ploughsoil; F) bronze horse-shaped fibula probably from northern Italy found in Trench IX (photographs A–E by P. Sánchez de Oro; F: https://cultura.castillalamancha.es/patrimonio/catalogo-patrimonio-cultural/yacimiento-arqueologico-de-el-cerron-de-illescas).

Two possible interpretations for the relief found at El Cerrón have been suggested by Balmaseda Muncharaz and Valiente Cánovas (Reference Balmaseda Muncharaz and Valiente Cánovas1979: 231–34). Focusing on the charioteers, they may have been two heroic figures or two deities whose totemic/apotropaic animal was the griffin, or possibly two deceased individuals journeying to the Underworld; in the latter case, the griffin could have been their psychopomp (spirit guide), and the standing figure is gesturing farewell. Although this interpretation finds parallels in the Iberian Peninsula (Eiroa García Reference Eiroa García1986), a funerary scene does not well fit with the context of discovery. On the contrary, the first interpretation better fits local and Mediterranean parallels, where elite power is strongly tied to cults of (heroised) ancestors, used for legitimation and protection purposes (Almagro-Gorbea & Lorrio Alvarado Reference Almagro-Gorbea and Lorrio Alvarado.2011).

Whatever the purpose of the original structure that hosted the full scene—be it an elite residence or a cultic place—it is probable that the relief hung in a clearly visible position. Maintenance of a fragment within the bench/altar that stood opposite the entrance to Structure 2, a possible shrine, suggests that although the relief was not entirely preserved, it continued to play an important role for the community living at the site. Valiente Cánovas (Reference Valiente Cánovas1994) suggests that the settlement emerged at the beginning of the fourth century BC; given the current absence of evidence for an older occupation at the site, this is also the most probable date for the production of the relief.

The fourth century BC was a period of instability and turmoil in Carpetania, with an increase in social complexity and conflict for power in the Middle Tagus Valley possibly linked to a surplus in crop production and a growing population favoured by the late sub-Atlantic climate phase (De Torres Rodríguez Reference De Torres Rodríguez2013: 107–108, 351–52, and references therein). The material culture at this time is characterised by wheel-made pottery, suggesting a standardised local production that included vessels better suited for storage; iron tools, mainly related to ploughing and farming, which allowed the cultivation of heavier soils; and imports, showing an increase in the wealth of local communities (De Torres Rodríguez Reference De Torres Rodríguez2013: 351–52; Urbina Martínez 2014: 182–85). A new settlement pattern also emerged; while previous sites were placed on plains close to fresh-water streams and productive land, from the fourth century BC onwards settlements also occupied more defensive locations such as hilltops, surrounded by ramparts, walls and moats (Urbina Martínez Reference Urbina Martínez2005: 45–46). The first occupation phase at El Cerrón contains imports and local imitations—at least two of them recovered in the ploughsoil (Figure 8D & E)—of both Mediterranean and Iberian goods dated between the fourth and second centuries BC (Figure 8). It is, however, possible that this pattern of import and imitation could have already started by the end of the fifth century BC, as indicated by discoveries at other inland Iberian sites (Pereira Sieso Reference Pereira Sieso, López Ruiz, Parra Camacho and Prados Torreira2012; Celestino Pérez Reference Celestino Pérez2013, Reference Celestino Pérez, Rodríguez González, Gutiérrez García and Dorado Alejos2023; Martín Ruiz Reference Martín Ruiz2020; Vives-Ferrándiz Sánchez Reference Vives-Ferrándiz Sánchez and Olcina Domenech2021; Cebrián Fernández Reference Cebrián Fernández2022; Blanco-González et al. Reference Blanco-González, Padilla Fernández and Dorado-Alejos2023; Celestino Pérez et al. Reference Celestino Pérez, Rodríguez González, Gutiérrez García and Dorado Alejos2023; Miguel-Naranjo et al. Reference Miguel-Naranjo, Rodríguez González and Celestino Pérez2023; see also Figure 6).

The ‘Mediterraneanising’ relief and imported artefacts suggest that the Carpetanian elite was capable of reaching Mediterranean markets, most probably through the southern Iberian Peninsula along the so-called Iberian Via Salaria (Almagro-Gorbea et al. Reference Almagro-Gorbea, Lorrio Alvarado and Torres Ortiz2021; Cebrián Fernández Reference Cebrián Fernández2022) and/or the rivers Tagus and Guadiana (Figure 6). Interaction with further areas is also attested by a bronze horse-shaped fibula found at El Cerrón (Figure 8F), which can be characterised as an import from northern Italy based on existing parallels (Sundwall Reference Sundwall1943: 256, fig. 8; Graells i Fabregat Reference Graells i Fabregat2022: 140). These finds contradict the traditional interpretation of a Late Iron Age Carpetania characterised by heterarchy or status quo (De Torres Rodríguez Reference De Torres Rodríguez2013: 442) and, instead, help support the idea of an active participation of the local elite in wider Mediterranean, and northern Iberian, influences that were consciously adopted and adapted to fit the elite needs.

The griffin motif in the relief at El Cerrón is telling, in this sense, as it appears to depict a lotus flower stemming from its open mouth (see Figure 5). To date, no close parallel for this motif has been found in the Iberian Peninsula, neither decorating locally made artefacts nor imported goods. Parallels are found, however, in Situla Art, a 660/650–275 BC artisanal tradition that arose between the Apennines and the Eastern Alps characterised by sheet-bronze objects with embossed and/or incised decoration given an eastern Mediterranean (i.e. Orientalising) taste depicting animals, plants and/or human figures generally distributed in friezes (Saccoccio Reference Saccoccio2023). Lotus flowers are prevalent in Situla Art, though griffins are rare; possibly only two examples exist (at Este and Oppeano, in north-east Italy) and neither are depicted with a lotus flower stemming from their mouth (Zaghetto Reference Zaghetto2017: 25, fig. 2, 98, fig. 48 c, 105). Floral features may also be recognised in the oblong elements stemming from the mouth of the fully preserved horse in the relief at El Cerrón; this motif is again found in Situla Art, including depictions of ungulates (e.g. Montebelluna situla, lowest frieze, north-east Italy; Saccoccio Reference Saccoccio2023: 84, fig. 10a2). Given the physical distance between the griffins of the Iberian Peninsula and the Situla Art of northern Italy (see Figure 6), a potential link between these disparate artistic phenomena is provided by Phoenician merchants and craftsmen who progressively spread knowledge and (eastern) ‘Mediterraneanising’ influence across the Mediterranean basin from east to west. In the case of the Iberian Peninsula, Phoenician scarabs seem to have played a major role in disseminating this ‘Mediterraneanising’ motif (see discussion above).

Given the available data, Structures 1 and 2 at El Cerrón could be interpreted as shrines (see Almagro-Gorbea & Berrocal-Rangel Reference Almagro-Gorbea and Berrocal-Rangel1997). Although little is known about Structure 3, its location—superimposed upon two previous possible shrines—might allow a similar interpretation. Moreover, we believe that the two distinct episodes of fire that affected Structures 1 and 2 are consistent with other indicators of instability and turmoil from the fourth century BC onwards in Carpetania (see above). Nevertheless, the reuse of the relief, even if only partially preserved, within Structure 2 could have acted as a means for the local elite to legitimise its power, power that possibly ultimately derived from the protection of heroised ancestors (see Almagro-Gorbea & Lorrio Alvarado Reference Almagro-Gorbea and Lorrio Alvarado.2011).

Conclusions

Critical re-evaluation of published archaeological evidence from El Cerrón allows us to suggest that, although traditionally viewed as a marginal district, Carpetania was fully embedded in networks of ‘Mediterraneanisation’ and northern Iberian exchange during the Late Iron Age. Through these connections, ‘Mediterraneanising’ and Iberian customs and goods were consciously adopted and adapted by the local elite, most probably to legitimise power and status. The ‘Mediterraneanising’ terracotta relief at El Cerrón indicates that these wider influences were apparent by at least the fourth century BC, coinciding with a period of instability and turmoil in Carpetania marked by the emergence of a more defensive settlement pattern associated with increased production, population size, conflict and social complexity.

Our findings highlight a critical need to challenge long-standing assumptions and confront biases that have shaped Mediterranean interaction studies, especially regarding districts traditionally labelled as ‘marginal’. By rethinking these perspectives, we create a more inclusive and nuanced view of historical dynamics, allowing us to gather insights into the complexities of the past and their lasting impact.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff at the Museum of Santa Cruz of Toledo, especially Dr Antonio Dávila Fernández and Mr Jaime Gallardo, and the staff at the Archive of Castilla-La Mancha, especially Mr Pedro Cobo. Finally, we are also very grateful to Prof. Juan Blánquez Pérez, Dr Raimon Graells i Fabregat and the three anonymous peer-reviewers for their valuable feedback.

Funding statement

The writing of this article has been supported by a Formación de Profesorado Universitario Grant (FPU2021/03441) from the Ministerio de Universidades of Spain and a Leverhulme Early Career Fellowship (ECF-2021-654).