Challenges in social communication and interaction constitute one of the defining diagnostic criteria of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5 (APA, 2013). Specifically, while there is substantial variability in structural language across the spectrum, pragmatic abilities related to organizing one’s discourse based on the listener’s needs appear to be difficult even for those autistic individuals with structural language within typical range, i.e., whose vocabulary and grammar are age-appropriate and equivalent to those of their typically developing (TD) peers (Colle et al., Reference Colle, Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright and van der Lely2008; Kenan et al., Reference Kenan, Zachor, Watson and Ben-Itzchak2019; Tager-Flusberg et al., Reference Tager-Flusberg, Paul, Lord, Volkmar, Paul, Klin and Cohen2005). Narratives offer a particularly suitable medium for assessing these pragmatic skills in autistic individuals. By engaging in a storytelling task, narrators are not only required to master structural language elements, but they also need to consider the listener’s knowledge and perspective to establish appropriate reference, to mention information that is relevant for the comprehension of the story, and to organize the story in a manner that elucidates clear causal and temporal connections between events (Capps et al., Reference Capps, Losh and Thurber2000; Colle et al. Reference Colle, Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright and van der Lely2008; Diehl et al., Reference Diehl, Bennetto and Young2006; Hudson & Shapiro, Reference Hudson, Shapiro, McCabe and Peterson1991; Kenan et al., Reference Kenan, Zachor, Watson and Ben-Itzchak2019; Tager-Flusberg & Sullivan, Reference Tager-Flusberg and Sullivan1995). Moreover, understanding the characters’ motivations and reactions is crucial for constructing an effective narrative that engages the listener (Colle et al., Reference Colle, Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright and van der Lely2008; Tager-Flusberg & Sullivan, Reference Tager-Flusberg and Sullivan1995). Therefore, narratives serve as a valuable tool for assessing not only language proficiency but also socio-pragmatic and cognitive abilities in autistic individuals, which may go unnoticed in standardized tests (Adams & Bishop, Reference Adams and Bishop1989).

Research on narrative production within autism has predominantly focused on aspects of both the microstructure of narratives (e.g., the total number of words or the mean length of utterance), and their overarching organization into coherent narratives or macrostructure.Footnote 1 As highlighted in the meta-analysis conducted by Baixauli et al. (Reference Baixauli, Colomer, Roselló and Miranda2016), the prevailing trend observed in previous research suggests that, while there is considerable variability in microstructural skills, challenges in macrostructure appear to be pervasive across the spectrum. These challenges have been attributed to difficulties in ascribing mental states to others, known as theory of mind (ToM) (Baron-Cohen et al., Reference Baron-Cohen, Leslie and Frith1985; Tager-Flusberg & Sullivan, Reference Tager-Flusberg and Sullivan1995; Beaumont & Newcombe, Reference Beaumont and Newcombe2006), strong focus on detail and difficulties in perceiving the overall context, known as local processing (Frith & Happé, Reference Frith and Happé1994; Happé & Frith, Reference Happé and Frith2006; Kenan et al., Reference Kenan, Zachor, Watson and Ben-Itzchak2019), and issues in executive functioning (Demetriou et al., Reference Demetriou, Lampit, Quintana, Naismith, Song, Pye, Hickie and Guastella2018; Reference Demetriou, DeMayo and Guastella2019; Greco et al., Reference Greco, Choi, Michel and Faja2023; Scionti et al., Reference Scionti, Zampini and Marzocchi2023). Addressing the intricacies of these hypotheses in detail goes beyond the scope of the present paper.

Narrative coherence

In typical development, narrative coherence skills show a gradual development, with notable improvements observed from early childhood to elementary school years. As shown in numerous studies, TD children begin to produce more complex, detailed, and structurally coherent narratives around the age of 9–10 years (Aksu-Koç & Aktan-Erciyes, Reference Aksu-Koç, Aktan-Erciyes, Dattner and Ravid2018; Berman & Slobin, Reference Berman and Slobin1994; Caballero et al., Reference Caballero, Aparici, Sanz-Torrent, Herman, Jones and Morgan2020; Hudson & Shapiro, Reference Hudson, Shapiro, McCabe and Peterson1991; Mäkinen, Reference Mäkinen2014; Sah, Reference Sah2015). These narratives are characterized by the inclusion of a greater number of relevant events, more story grammar components (characters, setting, resolution, etc.), establishment of logical connections between events, more frequent use of evaluative expressions referring to characters’ mental states, and improved use of referential expressions. Furthermore, TD children’s development of coherence skills coincides with advances in language ability (Berman & Slobin, Reference Berman and Slobin1994). Specifically, the pivotal role of vocabulary skills in predicting narrative performance (including macrostructure abilities) has been emphasized in the literature (Heilmann et al., Reference Heilmann, Miller, Nockerts and Dunaway2010; Ralli et al., Reference Ralli, Kazali, Kanellou, Mouzaki, Antoniou, Diamanti and Papaioannou2021). In contrast, autistic individuals have been noted to face more challenges than their TD counterparts in constructing coherent narratives even in adulthood (Dindar et al., Reference Dindar, Loukusa, Leinonen, Mäkinen, Mämmelä, Mattila, Ebeling and Hurtig2022; Geelhand et al., Reference Geelhand, Papastamou, Deliens and Kissine2020) and even when matched on language ability with the TD group (see, for instance, Diehl et al., Reference Diehl, Bennetto and Young2006). Research concerning the link between the development of language ability and coherence skills within the autistic group remains relatively limited, although insightful tentative findings have been reported by studies such as those by Peristeri et al. (Reference Peristeri, Andreou and Tsimpli2017) or Norbury et al. (Reference Norbury, Gemmell and Paul2014). Peristeri et al. (Reference Peristeri, Andreou and Tsimpli2017) found that autistic children with high language abilities (as measured by expressive vocabulary and verbal IQ scores on WISC-III, Wechsler, Reference Wechsler1992) performed better than those with lower language skills in some (e.g., use of ToM-related internal state terms) but not all (e.g., story structure complexity) macrostructural aspects. On the other hand, Norbury et al. (Reference Norbury, Gemmell and Paul2014) observed a negative correlation between expressive and receptive language ability (as measured by scores on the CELF-4, Semel & Wiig, Reference Semel and Wiig2006) and the mentioning of relevant story events within the autistic group. They suggest that this might be attributed to verbose autistic children being less likely to remain relevant to the task. However, these findings deserve further investigation.

As is apparent, coherence is not a straightforward binary concept but rather exists on a gradient influenced by many factors. This complexity has led to the adoption of a wide array of methodologies in the literature to explore and understand narrative coherence in autism, as shown in Harvey et al. (Reference Harvey, Spicer-Cain, Botting, Ryan and Henry2023)’s review. These include story grammar frameworks (Colozzo et al., Reference Colozzo, Morris and Mirenda2015; Govindarajan & Paradis, Reference Govindarajan and Paradis2022; Peristeri et al., Reference Peristeri, Andreou and Tsimpli2017; Stein & Glenn, Reference Stein, Glenn and Freedle1979), single scoring holistic rubrics (Heilmann et al., Reference Heilmann, Miller, Nockerts and Dunaway2010; King et al., Reference King, Dockrell and Stuart2014; King & Palikara, Reference King and Palikara2018), the main events approach (Carlsson et al. Reference Carlsson, Johnels, Gillberg and Miniscalco2020; Mäkinen et al., Reference Mäkinen, Loukusa, Leinonen, Moilanen, Ebeling and Kunnari2014), high-point analyses (McCabe et al., Reference McCabe, Hillier and Shapiro2013; Reference McCabe, Hillier, Dasilva, Queenan and Tauras2017), and the assessment of coherence in terms of causality (Diehl et al., Reference Diehl, Bennetto and Young2006; Ferretti et al., Reference Ferretti, Adornetti, Chiera, Nicchiarelli, Valeri, Magni, Vicari and Marini2018; Sah & Torng, Reference Sah and Torng2015). After conducting a thorough examination of the advantages and limitations associated with each approach, Harvey et al. (Reference Harvey, Spicer-Cain, Botting, Ryan and Henry2023) concluded that none of these frameworks fully captures all the dimensions that contribute to narrative coherence. To address this gap, they recommend that future research adopt a more comprehensive approach, considering key elements such as context, chronology, causality, congruence, characters’ mental/emotional states, and cohesion. Furthermore, they also emphasize the importance of using detailed rating scales to capture the complexity of narrative quality more effectively.

Within this diverse landscape, theories of rhetorical relations (RRs), also known as coherence or discourse relations (Asher & Lascarides, Reference Asher and Lascarides2003; Jasinskaja & Karagjosova, Reference Jasinskaja and Karagjosova2020; Mann & Thompson, Reference Mann and Thompson1988), offer an alternative way to conceptualize and analyze discourse coherence. In these theories, coherence is achieved when elementary discourse units (EDUs), the smallest units of discourse – typically clauses – that serve a clear discourse function, are interconnected through explicit or implicit RRs (Mann & Thompson, Reference Mann and Thompson1988; Reese et al., Reference Reese, Hunter, Asher, Denis and Baldridge2007). As defined by Jasinskaja and Karagjosova (Reference Jasinskaja and Karagjosova2020), an RR is a pragmatic function that one discourse segment (or multiple segments) fulfills with respect to another. However, RRs have been organized into a wide array of categories in the existing literature. In an effort to bring clarity and consistency to this varied body of work, Jasinskaja and Karagjosova (Reference Jasinskaja and Karagjosova2020) compiled a consensus list of core RRs: Narration, where the second EDU describes an event that follows the first; Parallel, where the content of the two EDUs is similar along some relevant dimension; Contrast, where the content of the two EDUs is opposite; Elaboration, where the second EDU provides additional detail about the first; Explanation, where the second EDU is the cause or reason for an event, belief or utterance; and Result, where the second EDU is the consequence for an event, belief or utterance. Despite this taxonomy being well-established in linguistic theory and discourse studies, no empirical research has, to our knowledge, explicitly employed it in the analysis of children’s narrative coherence.Footnote 2

The goal of this paper is to examine and compare the narrative coherence of Spanish-speaking autistic and TD children. Drawing upon established theories of discourse relations, our analysis focuses on the RRs present in their stories, with particular attention given to the number and type of causal RRs established.Footnote 3 By incorporating the RR approach to our study, we hope to provide a novel perspective on how coherence is achieved in autistic and TD children’s narratives. Furthermore, following Harvey et al. (Reference Harvey, Spicer-Cain, Botting, Ryan and Henry2023)’s recommendations, in this paper, we employ a rating scale to compare the overarching organization (i.e., macrostructure) of narratives by autistic and TD children, in line with more standard practices in the field. Including both measures (RRs and macrostructure scores) will enable us to explore whether a more traditional macrostructural approach and the RR approach to coherence yield similar results when examined on the same data (as also suggested by Harvey et al., Reference Harvey, Spicer-Cain, Botting, Ryan and Henry2023).

Causal connections in narratives

There is a general agreement on the idea that establishing causal connections between events is key to constructing and conveying coherent narratives (Adornetti et al., Reference Adornetti, Chiera, Altavilla, Deriu, Marini, Gobbo, Valeri, Magni and Ferretti2023; Aksu-Koç & Aktan-Erciyes, Reference Aksu-Koç, Aktan-Erciyes, Dattner and Ravid2018; Hudson & Shapiro, Reference Hudson, Shapiro, McCabe and Peterson1991; Karmiloff-Smith, Reference Karmiloff-Smith1985; Trabasso & Sperry, Reference Trabasso and Sperry1985). Building these connections requires taking the listener’s perspective and needs into account to provide the necessary explanations and details (Colle et al., Reference Colle, Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright and van der Lely2008; Diehl et al., Reference Diehl, Bennetto and Young2006; Hallin et al., Reference Hallin, Garcia and Reuterskiöld2016; Sah & Torng, Reference Sah and Torng2015). While TD children show a gradual increase in the number of causal connections in their narratives (Berman & Slobin, Reference Berman and Slobin1994; Sah, Reference Sah2015; Trabasso & Nickels, Reference Trabasso and Nickels1992), autistic children seem to struggle with the establishment of these connections, with indications that these difficulties persist into adulthood (Diehl et al., Reference Diehl, Bennetto and Young2006; Geelhand et al., Reference Geelhand, Papastamou, Deliens and Kissine2020; King & Palikara, Reference King and Palikara2018; Losh & Capps, Reference Losh and Capps2003). However, discrepancies across studies suggest that the evidence is not conclusive, possibly due to methodological issues.Footnote 4

In the existing literature on autistic individuals’ ability to establish causal connections within narratives, the predominant focus has been the quantification of causal connectives, which has been the source of conflicting findings (Adornetti et al., Reference Adornetti, Chiera, Altavilla, Deriu, Marini, Gobbo, Valeri, Magni and Ferretti2023; Baixauli et al., Reference Baixauli, Colomer, Roselló and Miranda2016; Tager-Flusberg, Reference Tager-Flusberg1995). While some studies observe fewer causal connectives in the narratives produced by autistic children and adults when compared to their age-matched and/or language-matched TD counterparts (Geelhand et al., Reference Geelhand, Papastamou, Deliens and Kissine2020; King et al., Reference King, Dockrell and Stuart2014; Losh & Capps, Reference Losh and Capps2003), others find a comparable number in both groups (Capps et al., Reference Capps, Losh and Thurber2000; Sah & Torng, Reference Sah and Torng2015; Suh et al., Reference Suh, Eigsti, Naigles, Barton, Kelley and Fein2014; Tager-Flusberg & Sullivan, Reference Tager-Flusberg and Sullivan1995). Beyond mere quantification of connectives, some studies also delve into the type of causal connection expressed. For instance, Losh and Capps (Reference Losh and Capps2003) and Capps et al. (Reference Capps, Losh and Thurber2000) distinguish between causal statements that explain the cause of an event (e.g., the jar broke because the dog fell), those that elucidate the cause of a behavior (e.g., the boy looked in the hole to try to find the frog) and those that focus on the cause of an internal state (e.g., the boy was mad because the dog broke the jar). Notably, Capps et al. (Reference Capps, Losh and Thurber2000) found that, despite producing a similar number of causal connectives, autistic children were less inclined than their language-matched TD peers to provide descriptions of the causal circumstances surrounding characters’ thoughts and emotions. Losh and Capps (Reference Losh and Capps2003), in turn, noted fewer of the three types of causal explanations within the autistic cohort, matched on age and verbal IQ with the TD group. Finally, in Kelley et al. (Reference Kelley, Paul, Fein and Naigles2006)’s study, causal explanations (defined as discussions about the cause of an action or an event) and discussion of goals were coded as distinct categories. They observed that the autistic group was significantly less likely to include both causal discussions and discussions of goals in their narratives compared to the TD group matched on age, sex, and receptive vocabulary. However, it remains unclear whether these classifications were solely based on the number of connectives produced.

Causal connections have also been analyzed through the lens of the causal network framework proposed by Trabasso and Sperry (Reference Trabasso and Sperry1985). In this framework, the importance of an event is determined by its number of causal connections – the number of other events it causes in the story (Diehl et al., Reference Diehl, Bennetto and Young2006). In essence, the coherence of a child’s narrative is postulated to be contingent upon the inclusion of important events, irrespective of whether these events are explicitly linked through causal language. The more important events a child mentions, the greater the number of causal connections manifested in their narrative, ultimately contributing to its overall coherence. Empirical studies employing this framework to investigate differences between autistic and TD children appear to encounter significantly fewer causal connections in the autistic group, regardless of whether the groups are matched on chronological age, language ability, and/or cognitive skills (Diehl et al., Reference Diehl, Bennetto and Young2006; Ferretti et al., Reference Ferretti, Adornetti, Chiera, Nicchiarelli, Valeri, Magni, Vicari and Marini2018; Sah & Torng, Reference Sah and Torng2015). Furthermore, within this framework, Trabasso and colleagues (Trabasso et al., Reference Trabasso, van der Broek and Suh1989; Trabasso & Nickels, Reference Trabasso and Nickels1992) also proposed a classification of types of causal relations. They follow the story grammar framework and distinguish four types of causal relations, which serve to connect events within a single episode or across multiple episodes: Enabling (e.g., then they search for it in front of a pile of wood. They find two frogs), Physical (e.g., the dog forcefully shakes the tree. It causes the beehive to fall off the tree), Psychological (e.g., the dog accidentally breaks the frog’s jar. The little boy is therefore very angry) (examples retrieved from Sah & Torng, Reference Sah and Torng2015: 211-212), and Motivational (e.g., she ran into the water because she wanted to save it) (example retrieved from Fichman et al., Reference Fichman, Altman, Voloskovich, Armon-Lotem and Walters2017: 77).Footnote 5 This classification was employed in studies such as Sah and Torng (Reference Sah and Torng2015)’s, who merged Motivational and Psychological relations into a single type (i.e., Psychological), arguing that both types convey information about internal states of characters (intentions, beliefs, thoughts or emotions). Contrary to the findings reported by Capps et al. (Reference Capps, Losh and Thurber2000) and Losh and Capps (Reference Losh and Capps2003), no notable differences were detected between autistic and TD groups (matched on language and cognitive abilities) in the frequency of Psychological causal relations.

In summary, the current body of research on autistic individuals’ ability to establish causal connections within narratives (and thus to construct coherent narratives) presents a mixed picture, and therefore, additional data and insights into the causal relations these children produce are needed. Furthermore, the vast majority of the existing studies focus on English-speaking children. Expanding this research to include children who speak other languages is essential for gaining a more comprehensive understanding of how narrative coherence is manifested across different linguistic and cultural contexts.

The present study

The overarching goal of the present study is to contribute to enhancing the understanding of the differences Spanish-speaking autistic and TD children exhibit in narrative coherence. Specifically, we intend to contribute to this research by addressing the following specific questions:

(1) Do autistic children differ from their TD peers in the total number of RRs they establish in their narratives?

A novelty of this study lies in the creation of an annotation scheme based on theories of discourse relations (Asher & Lascarides, Reference Asher and Lascarides2003; Jasinskaja & Karagjosova, Reference Jasinskaja and Karagjosova2020; Mann & Thompson, Reference Mann and Thompson1988) for coding the RRs present in children’s narratives. Building on the assumption that EDUs need to be rhetorically connected in coherent discourse, and based on previous evidence suggesting that autistic individuals exhibit difficulties in constructing coherent narratives, we predicted that autistic children would establish fewer RRs in their narratives (relative to the total number of EDUs) when compared to their TD peers, resulting in narratives with more disconnected utterances.

(2) Do autistic children differ from their TD peers in the number and/or type of causal RRs they establish in their narratives?

The primary focus of our investigation centers around addressing this second research question. In view of the inconclusive results concerning autistic children’s ability to causally connect events in a narrative (e.g., Capps et al., Reference Capps, Losh and Thurber2000; Losh & Capps, Reference Losh and Capps2003; Sah & Torng, Reference Sah and Torng2015), we aim to provide further insights on the ways these children structure and convey causal relations. Since there is a potential risk of overlooking valuable information if the analysis is exclusively centered on the number of causal connectives produced by each group, we additionally considered those causal RRs that remained implicit,Footnote 6 as well as factors such as the type of RR or the domain of causality expressed, largely adhering to the classification outlined in Jasinskaja and Karagjosova (Reference Jasinskaja and Karagjosova2020). We categorized causal relations into three primary RR types: Explanation, which, as previously mentioned, elucidates the cause of an event, belief or utterance (“x”); Result, where the emphasis is placed on the consequence of x; and Purpose,Footnote 7 which incorporates an intentional aspect, addressing the objective or aim behind x.Footnote 8 In addition, these causal RRs can pertain to various causality domains. For instance, Explanation can give “the cause or reason why the state of affairs presented in the context sentence takes place, or why the speaker believes the content of that sentence, or why the speaker chose to utter it” (Jasinskaja & Karagjosova, Reference Jasinskaja and Karagjosova2020:5). These correspond to the three domains identified by Sweetser (Reference Sweetser1990): Content causality, Epistemic causality and Speech-act causality, respectively. The content domain concerns instances of objective real-world causation, denoting cause–effect relationships between two objective events within the narrative. In contrast, the epistemic and speech act domains are characterized by subjectivity (i.e., instead of linking cause and consequences of objective events, they connect claims and conclusions, as outlined in Zufferey et al., Reference Zufferey, Mak and Sanders2015). Lastly, we also considered the relevance of the causal RR to the narrative’s main plot. The complete coding scheme, along with examples for each coded category, is provided in the Coding section.

By focusing on the expression of causality in language (causal RRs), we can go beyond merely assessing the presence of events causing other events (as done, for instance, in the study by Diehl et al., Reference Diehl, Bennetto and Young2006), which may introduce uncertainty regarding the true comprehension of the causal relation itself. For instance, a child may mention a prominent event in the narrative (i.e., an event with a large number of causal connections) due to its frequent recurrence within the story, which does not necessarily imply an understanding of the causal relation between this and other events – a limitation also acknowledged in Diehl et al. (Reference Diehl, Bennetto and Young2006). Focusing on the ways in which causality can be expressed can also reveal differences in the linguistic resources that each population handles more easily, which may relate to cognitive or communicational differences.

We predicted that autistic children would produce fewer causal RRs overall compared to their TD peers, in line with previous research indicating reduced narrative coherence in this population. In particular, we expected the differences to be particularly pronounced with respect to Purpose RRs, since this type of relation requires an understanding of characters’ goals/intentions, which may involve some level of ToM, an area that can present challenges for autistic individuals. In the same vein, we predicted that autistic children might produce fewer RRs expressing Epistemic causality, given that this domain also entails considering different perspectives. In addition, we expected to find fewer Relevant causal RRs in autistic children’s narratives (see, for instance, Diehl et al., Reference Diehl, Bennetto and Young2006). Finally, with regard to causal connectives (i.e., Explicit causal RRs), we did not have a clear prediction, as the literature presents conflicting findings (e.g., Capps et al., Reference Capps, Losh and Thurber2000; Losh & Capps, Reference Losh and Capps2003) and we lacked a principled reason to expect differences between autistic and TD participants in the marking of causal RRs.

(3) Do autistic children differ from their TD peers in the overall organization of their narratives (i.e., macrostructure)?

In order to gain a more comprehensive understanding of children’s macrostructure skills, narratives were coded following the macrostructure rubric Narrative Scoring Scheme (NSS) published in Heilmann et al. (Reference Heilmann, Miller, Nockerts and Dunaway2010), as detailed in the Coding section. While the main focus of our study is on evaluating coherence through the lens of RRs, the NSS offers a complementary, broad measure of narrative elements that are essential for constructing a coherent story and is particularly valuable for evaluating overall narrative quality. We anticipated that autistic children would obtain lower scores on the NSS (King et al., Reference King, Dockrell and Stuart2014; King & Palikara, Reference King and Palikara2018), and hence that they would show lower macrostructure skills when compared to TD children, as previous evidence (see Baixauli et al., Reference Baixauli, Colomer, Roselló and Miranda2016) suggests.

Methods

Participants

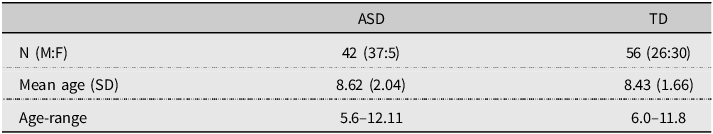

In this study, ninety-eight Spanish-speaking children aged between 5.6 and 12.11 were included (M = 8.51 years), categorized into two diagnostic groups: the ASD group and the TD group (see Table 1 below). The two groups were matched on chronological age (CA), as confirmed by a Mann–Whitney U test (W = 1269.5, p = 0.50).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of participants’ characteristics per diagnostic group.

The cohort of autistic children consisted of 42 children (37 boys and 5 girls) recruited via the Lindy Lab: Language in Neurodiversity Lab at the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU) in Vitoria-Gasteiz, the Biscayan autism association APNABI in Bilbao and the Matemáticas y Autismo Lab at the University of Cantabria (UC) (Spain). Inclusion criteria for the ASD group were the following: (1) CA falling within the range of 5.0 and 12.11 years; (2) ability to produce narratives consisting of more than one sentence (children who exclusively produced single words were excluded from participation); and (3) non-verbal IQ (NVIQ) score above 80 (M = 105, SD = 10.7) as assessed through the Leiter-3 scale (Roid et al., Reference Roid, Miller, Pomplun and Koch2013), to confirm the absence of intellectual disability. In addition, the receptive vocabulary test Peabody, PPVT-III (Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Dunn and Arribas2010) was used to assess autistic participants’ receptive language ability (raw scores: M = 99.8, SD = 21.2). Autistic children’s age equivalent of receptive vocabulary ranged from 6.0 to 11.11 years (M = 8.21, SD = 1.8).Footnote 9 All autistic participants had previously obtained a clinical diagnosis of autism from either a multidisciplinary assessment team external to our research group or by a certified practitioner within our team, who possessed the necessary expertise to administer the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule 2, ADOS-2 (Lord et al., Reference Lord, Rutter, DiLavore, Risi and Gotham2012).

The control group was formed by 56 TD children (26 boys and 30 girls) recruited from a local school in Basauri (Basque Country, Spain). None of them had a known history of psychiatric diagnosis. Specific data on receptive vocabulary or NVIQ could not be recorded due to logistic constraints.Footnote 10

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee for research with human beings (CEISH) of the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU), code M10_2019_205. All parents/caregivers signed the consent form for the treatment of the data and for the participation of their children in the study, which included an authorization to be recorded during the storytelling task.

Data collection

Narratives were elicited by using the wordless picture book Frog, Where Are You? (Mayer, Reference Mayer1969). All children were tested individually by the same examiner in a quiet room free of distractions. TD children were tested at their school, while autistic children were tested at our research center. Importantly, the center was familiar to the children, as they had visited it previously and associated it with positive experiences. Before narrating the story, it was explicitly indicated to participants that the examiner was not familiar with the story. Children were left some time to look through the pictures to familiarize themselves with the story and then told the story to the examiner, while looking at the pictures. If needed, children received assistance in initiating their narrative by being prompted with the question what happens in the story?, and only minimal prompts were given in cases where the participant did not continue narrating. If children overlooked a picture, the examiner redirected the child to that picture. Throughout the narration task, the examiner tried to motivate the children, either by echoing their utterances or by using neutral prompts such as mhm or very good.

Transcription

Each story was video-recorded and subsequently manually transcribed by the researcher using the CHAT transcription format of the Child Language Data Exchange System, CHILDES (MacWhinney, Reference MacWhinney2000). A first segmentation was done into c-units, defined as a main clause along with its dependent clauses (MacWhinney, Reference MacWhinney2000). Additionally, to facilitate the annotation of RRs, children’s productions were further segmented into EDUs, following Reese et al. (Reference Reese, Hunter, Asher, Denis and Baldridge2007)’s manual. Thus, an utterance like the jar broke because the dog fell would consist of a single c-unit but two EDUs (the jar broke <***> because the dog fell). All transcriptions and coding were done using CLAN (MacWhinney, Reference MacWhinney2000).

Coding

Story length, syntactic complexity, and lexical diversity

Despite not being the primary focus of the present paper, we coded several narrative microstructure variables to obtain a more complete picture of the linguistic properties of narratives generated by autistic and TD children within our sample. The assessment of story length involved analyzing the total counts of words and c-units. Repetitions of a word were counted as a single word. Moreover, fillers and non-word vocalizations (e.g., eh, pff, mhm) were not included in the total word count. To gauge syntactic complexity, we extracted the mean length of c-unit (MLCU). MLCU has traditionally served as a metric for assessing syntactic complexity, based on the assumption that the longer the c-unit is, the more likely it contains multiple clauses (Heilmann et al., Reference Heilmann, Miller, Nockerts and Dunaway2010; Mäkinen, Reference Mäkinen2014). Lastly, lexical diversity was measured by examining the number of different words (NDW).

Rhetorical relations

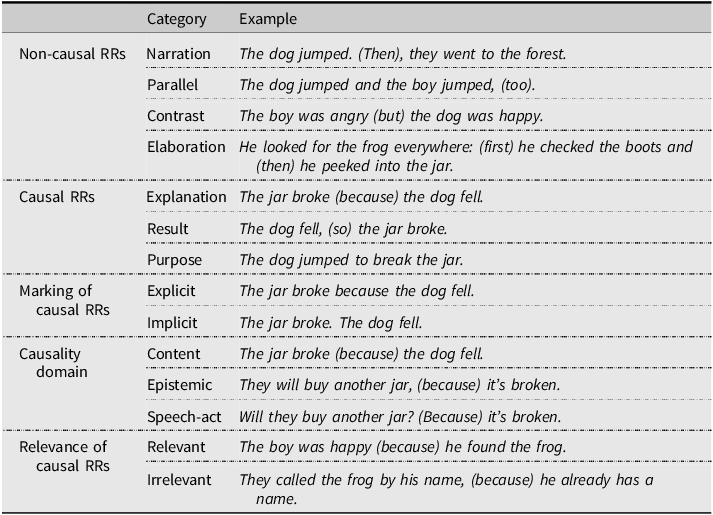

Following existing literature on RRs (Asher & Lascarides, Reference Asher and Lascarides2003; Jasinskaja & Karagjosova, Reference Jasinskaja and Karagjosova2020; Mann & Thompson, Reference Mann and Thompson1988), we coded the non-causal (Narration, Parallel, Contrast, and Elaboration) and causal (Explanation, Result, and Purpose) RRs produced by each child.

Each causal RR was further coded based on three additional key features: (i) marking, i.e., presence or absence of a connective (Explicit, Implicit), (ii) causality domain expressed (Content, Epistemic, Speech-act), and (iii) relevance (Relevant, Irrelevant). Causal RRs were coded as Relevant whenever they involved main or key events in the story. These key events were retrieved from the NSS addendum,Footnote 11 where major conflicts and resolutions specific to the story Frog, Where Are You? are outlined. Conversely, causal RRs were coded as Irrelevant if they did not involve key story events. Thus, only Relevant causal RRs contribute directly to the narrative’s main plot. Examples of each coded category are illustrated in Table 2 below (for detailed definitions of causal RR types and causality domains, see The present study section).

Table 2. Coding of rhetorical relations (RRs).

In some cases, ambiguity arose when determining whether an RR was genuinely causal. These cases mostly involved Implicit Result RRs (e.g., the dog fell. The jar broke), or Explicit Result RRs with the connective and (e.g., the dog fell and the jar broke). Since the connective is not unequivocal, coders found it challenging to ascertain whether the child was establishing a causal connection or merely narrating events in chronological order, for instance (especially in those cases where the child did not provide additional linguistic cues like intonation). These Ambiguous RRs were excluded from the total count of causal RRs.

Narrative Scoring Scheme

Narratives were coded following the NSS, which is based on an earlier version developed by the Madison Metropolitan School District SALT Working Group in 1998. The NSS was published in Heilmann et al. (Reference Heilmann, Miller, Nockerts and Dunaway2010). This holistic rubric evaluates essential story elements based on story grammar frameworks: Introduction, Character development, Mental states, Referencing, Conflict-resolution, Cohesion, and Conclusion. Unlike story grammar, however, NSS combines discrete coding criteria and examiner judgment to assess narrative quality; each of these components is rated on a scale from 0 to 5 points. This methodology, employed in studies by King et al. (Reference King, Dockrell and Stuart2014) and King and Palikara (Reference King and Palikara2018), for instance, provides a more comprehensive evaluation of children’s ability to construct a coherent narrative, going beyond merely identifying the presence or absence of story grammar components (Heilmann et al., Reference Heilmann, Miller, Nockerts and Dunaway2010). While there may be some overlap between the cohesion subcategory of the NSS and aspects of our coding of RRs (as explicit RRs contribute to cohesion), the two approaches have complementary purposes. The NSS provides a more global measure of narrative quality, including cohesion, which encompasses not only the use of connectives but also other aspects such as repetitions or reformulations, imbalance in detail (providing too much detail on supporting events), or the correct sequencing of events in the story. Our coding of RRs, on the other hand, offers a more fine-grained analysis of the underlying discourse structure and how the coherence of the narrative is constructed through both implicit and explicit RRs.

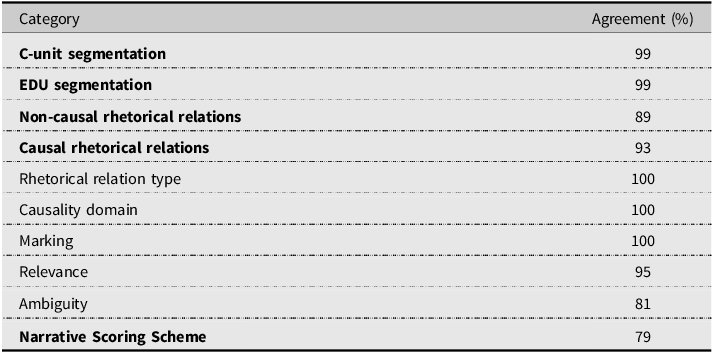

Coding reliability

To assess coding reliability, a second independent coder segmented and coded 15% of the narratives. All measures showed high reliability, with agreement exceeding the 80% in all cases except for the NSS, which showed an agreement of 79%. All disagreements were discussed and resolved. See Table A1 in the Appendix for the percentage of inter-rater agreement for each coding category, including the segmentation of c-units and EDUs.

Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted in R (R Core Team, 2023). For count data, a series of Poisson regressions were fitted using the glm function with feature type as dependent variable and diagnostic group (TD vs. ASD) as fixed effect.Footnote 12 Where necessary, the total number of EDUs or (causal) RRs was also controlled for by including them as fixed effects. When overdispersion was observed in the data, indicating a higher variability than expected under a Poisson distribution, negative binomial regressions were performed using the glm.nb function from the ‘MASS’ package (Venables & Ripley, Reference Venables and Ripley2002). This model is an extension of Poisson regression, which accommodates an additional parameter to account for overdispersion. The fit of negative binomial regressions against their respective Poisson models was assessed via the likelihood ratio test with the odTest function (see Winter, Reference Winter2019) from the ‘pscl’ package (Jackman, Reference Jackman2024). To model continuous data, a simple linear regression was conducted with the lm function, with diagnostic group as the fixed effect, mirroring the approach employed for modeling count data. The optimal models are reported in Tables A2-A3 in the Appendix.

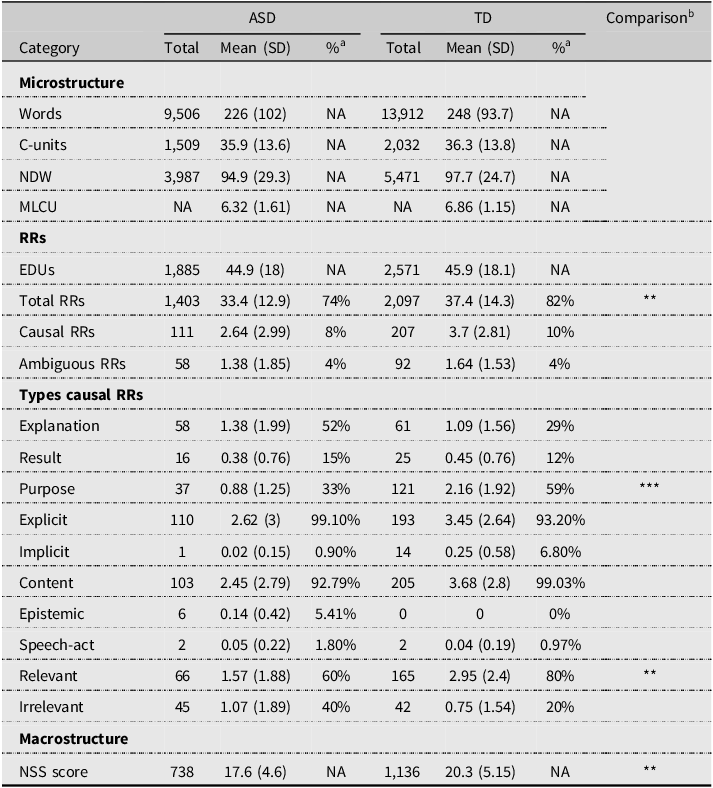

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of microstructure variables, rhetorical relations (RRs), types of causal RRs, and macrostructure scores (significant group differences indicated by significance codes).

Note: aPercentages were calculated by dividing the total number of RRs by EDUs, causal and ambiguous RRs by total RRs, and types of causal RRs by total number of causal RRs. b*=significance code when p < 0.05; **=significance code when p < 0.01; ***=significance code when p < 0.001.

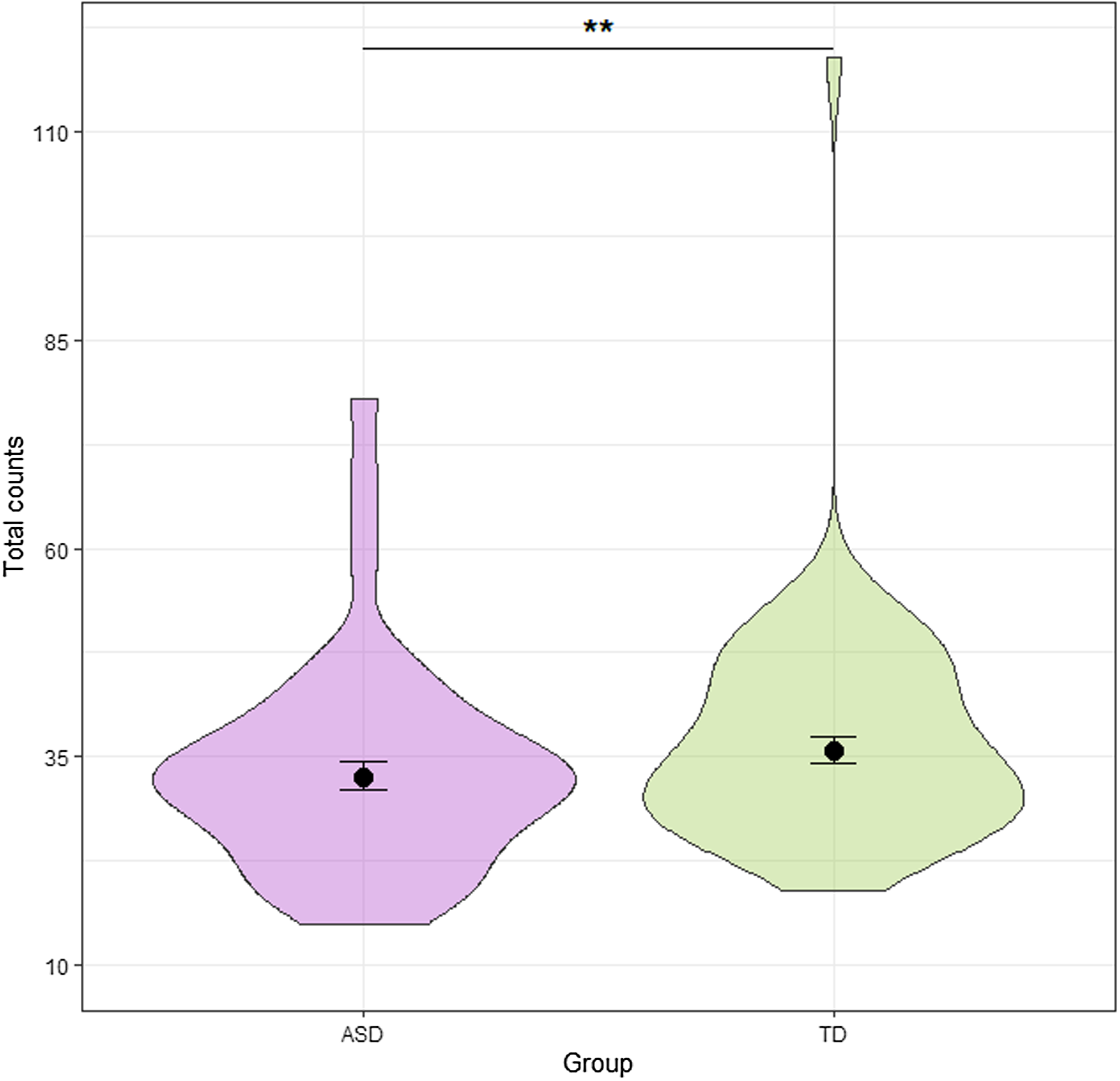

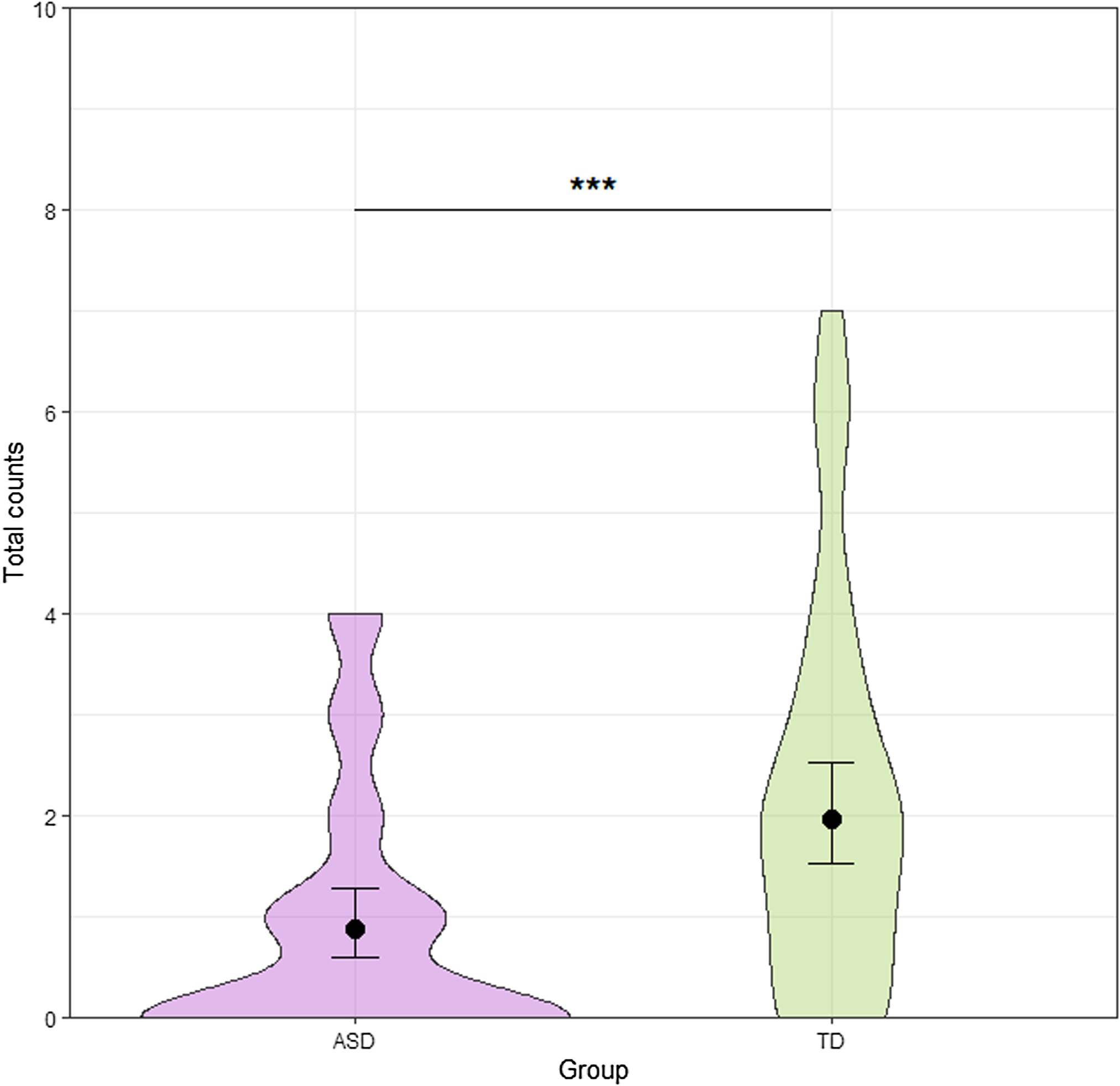

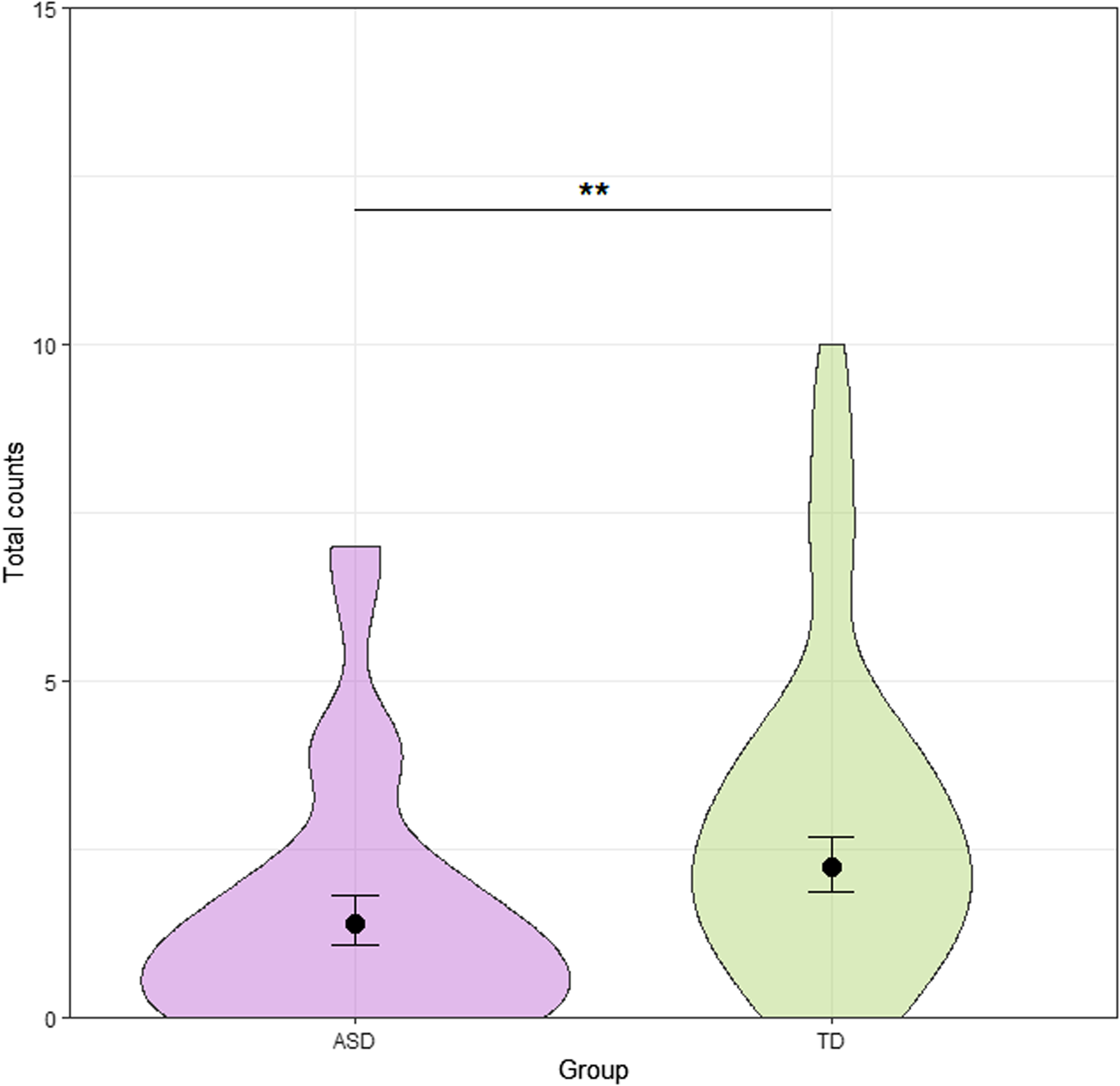

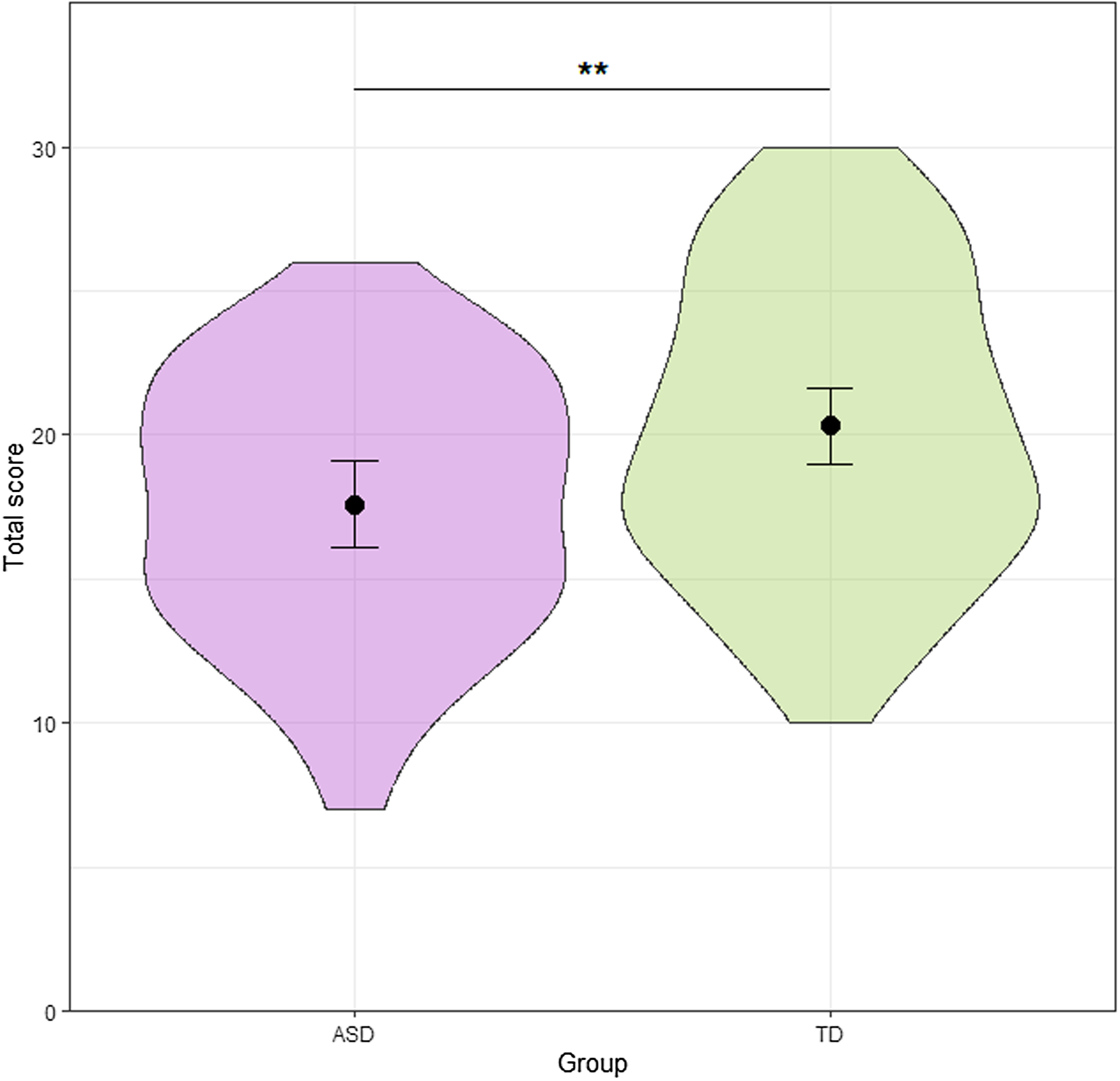

Given the inherent variability observed in counts, percentages were also calculated to facilitate a more standardized representation of the data. These percentage scores were computed by dividing the total count of the respective feature by the total number of EDUs, RRs, or causal RRs, depending on the specific variable under consideration. Descriptive statistics of all variables are shown in Table 3. Following Geelhand et al. (Reference Geelhand, Papastamou, Deliens and Kissine2020)’s methodology, models were developed employing the raw counts of the dependent variables. Violin plots are employed as a visual representation of raw data, as they offer a comprehensive depiction of the data distribution. The varying width of the shape within the violin plot indicates the density of data points, with wider sections indicating higher participant concentration and narrower sections indicating fewer data points. Dots indicate predicted means, and error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Study materials, data and code have been publicly made available on OSF at the following link: https://osf.io/whg2a/.

Story length, syntactic complexity and lexical diversity

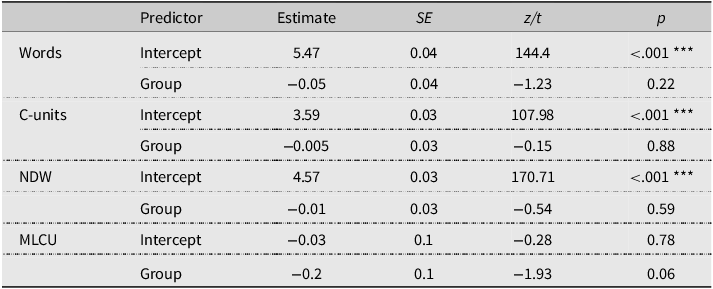

The models revealed no significant effects of diagnostic group on the total number of words, c-units, NDW, and MLCU. Thus, both autistic and TD children in our sample seem to be producing stories of a similar length, syntactic complexity, and lexical diversity (these null results are reported in Table A2 in the Appendix). These findings suggest that any observed differences in our main analysis (RRs and macrostructure scores) are unlikely to be due to structural language differences between the two groups.

Rhetorical relations

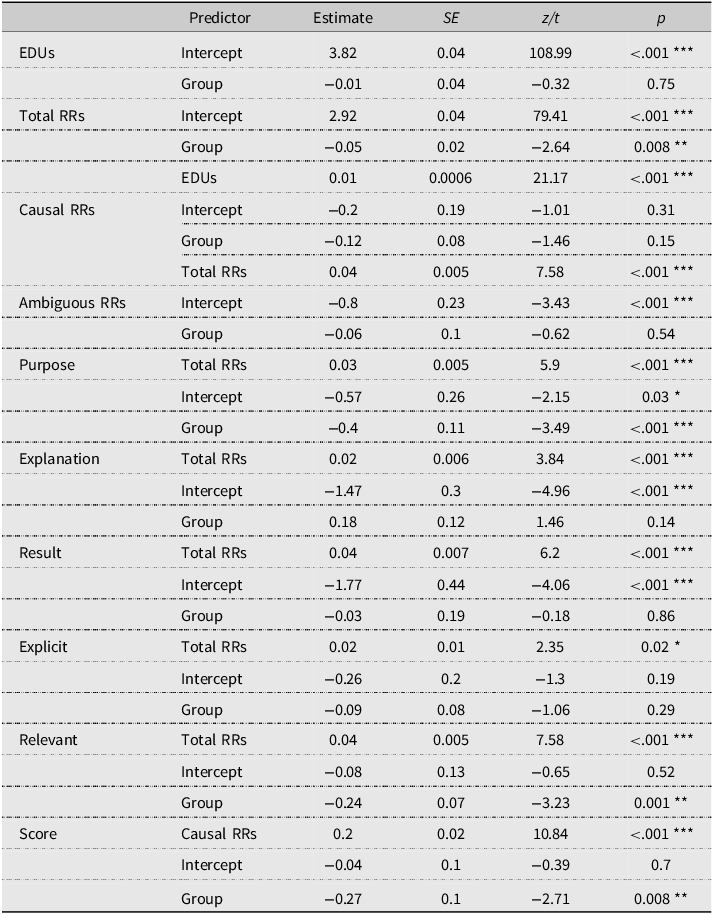

When examining the total number of RRs (while controlling for the total number of EDUs),Footnote 13 the model yielded a significant diagnostic group effect, with autistic children establishing significantly fewer RRs than TD children (β = −0.05, SE = 0.02, z = −2.64, p = 0.008), as illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Violin plots of total number of rhetorical relations per diagnostic group.

Causal rhetorical relations

No significant group differences were found when looking at the total number of causal RRs (after controlling for the total number of RRs); the two groups produced a comparable number of causal relations (β = −0.12, SE = 0.08, z = −1.46, p = 0.15).Footnote 14

Regarding causal RR types (i.e., Explanation, Result, Purpose), diagnostic groups significantly differed in the number of Purpose RRs (see Figure 2 below), with the ASD group establishing significantly fewer Purpose RRs than the TD group (β = −0.40, SE = 0.11, z = −3.49, p = <.001). No significant diagnostic group differences were observed with respect to Explanation (β = 0.18, SE = 0.12, z = 1.46, p = 0.14), and Result (β = −0.03, SE = 0.19, z = −0.18, p = 0.86) RRs.

Figure 2. Violin plots of total number of Purpose rhetorical relations per diagnostic group.

As for the total number of causal connectives (i.e., Explicit causal RRs), the model revealed no significant group differences (β = −0.09, SE = 0.08, z = −1.06, p = 0.29), mirroring those results observed when examining the total number of causal RRs (indeed, as shown in Table 3, the majority of causal RRs were explicitly marked).

With respect to causality domains, most of the causal RRs produced by autistic and TD children were objective in nature (i.e., expressing Content causality), as depicted in Table 3. There were very few RRs expressing Epistemic and Speech-act causality across both groups. This floor effect prevented the derivation of reliable parameter estimates and model fit statistics, thereby preventing an exploration of group performance for these causality domains.

Finally, the model examining the relevance of the causal RRs yielded a significant effect of diagnostic group, with the ASD group producing significantly fewer Relevant causal RRs than the TD group (β = −0.24, SE = 0.07, z = −3.23, p = 0.001) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Violin plots of total number of Relevant causal rhetorical relations per diagnostic group.

Narrative Scoring Scheme

When modeling the scores obtained on the NSS rubric, a significant effect of diagnostic group emerged in the linear regression, with the ASD group obtaining significantly lower scores compared to the TD group (β = −0.27, SE = 0.10, t = −2.71, p = 0.008), as illustrated in Figure 4 below.

Figure 4. Violin plots of total macrostructure scores (0/35) per diagnostic group.

Table 3 displays the descriptive statistics of the microstructure variables, RRs, types of causal RRs, and macrostructure scores per diagnostic group, with significance codes indicating significant group differences.

Discussion

The present study investigated the differences in narrative coherence between autistic and TD children by systematically analyzing their production of RRs (with particular attention given to causal RRs), as well as the overarching organization of their narratives (i.e., macrostructure). Our study contributes new data on Spanish-speaking children, for whom there is relatively limited research in the existing literature. The results show that the narratives of autistic children with age-appropriate receptive vocabulary and average non-verbal cognitive ability differed from those of age-matched TD children in several respects, despite being comparable in terms of story length, syntactic complexity, and lexical diversity. In addition, the findings of this study show that the coding of RRs can offer valuable insights into how autistic and TD children structure their narratives.

Total number of rhetorical relations

Concerning our first research question, relative to the total number of EDUs, autistic participants produced fewer RRs (encompassing both causal and non-causal RRs) than the TD participants, in line with our predictions. This result indicates that autistic children produced more non-connected or isolated utterances, which lines up with the findings reported in Diehl et al. (Reference Diehl, Bennetto and Young2006), where the retellings of autistic participants resembled a listing of discrete events rather than a structured narrative (see also Colle et al., Reference Colle, Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright and van der Lely2008). From the perspective of RR theories (Asher & Lascarides, Reference Asher and Lascarides2003; Mann & Thompson, Reference Mann and Thompson1988), this finding suggests lower coherence levels in the narratives of autistic children compared to those produced by their TD peers.

Causal rhetorical relations

For our second research question, we examined the number and type of causal RRs children established in their narratives. Contrary to our predictions, we found no significant diagnostic group differences in the total number of causal RRs. Despite total counts showing that autistic children produced fewer causal RRs than their TD counterparts, the difference failed to reach statistical significance. Thus, contrary to the conclusions drawn by, among others, Diehl et al. (Reference Diehl, Bennetto and Young2006), our findings do not seem to provide robust evidence showing that autistic children are less likely than their TD peers to establish causal connections when constructing a narrative. These discrepancies between studies do not appear to be attributable to participants’ profiles, as the age ranges of the participants in Diehl et al. (Reference Diehl, Bennetto and Young2006)’s study were comparable to those in ours, and autistic children’s language skills were within the typical range, as in our sample. Furthermore, they found no group differences in terms of story length or syntactic complexity, as also observed in our study. Thus, differences may stem from the coding schemes employed in the two studies. Notably, in their work, the coding of causal relations was specifically linked to the mentioning of important events (defined as those events that cause other events in the story). By contrast, we focused on the expression of causality in language.

Through our coding of different types of causal RRs, we were able to delve into the actual preferences regarding the specific ways in which each group of children established causal relations, providing insights that could not have been captured by simply examining causal RRs as a whole. As predicted, autistic children established fewer Purpose relations overall. This finding suggests an interesting divergence in narrative tendencies between autistic and TD children, which may reflect cognitive and socio-communicative differences. TD children appear to express causal connections that are primarily goal-oriented. In contrast, autistic children are less likely to signal characters’ intentions or goals, a finding which aligns with previous findings by, for instance, Kelley et al. (Reference Kelley, Paul, Fein and Naigles2006) and Losh and Capps (Reference Losh and Capps2003), and which could be attributed to the challenges autistic children may experience in understanding and interpreting intentions (ToM). Sah and Torng (Reference Sah and Torng2015), however, found no group differences in this respect. These inconsistent results may be due to variations in the criteria used to classify causal relations. Specifically, Sah and Torng (Reference Sah and Torng2015) merged Trabasso and colleagues’ (Trabasso et al., Reference Trabasso, van der Broek and Suh1989; Trabasso & Nickels, Reference Trabasso and Nickels1992) Psychological and Motivational causal relations into the same type. This could have led them to overlook Motivational relations alone, which may align more closely with our Purpose RRs (though not identically; see the discussion in footnote 8). Additionally, a difference in participants’ profiles should be noted, as Sah and Torng (Reference Sah and Torng2015)’s autistic participants were significantly older than their TD peers (group matching was done based on language ability), whereas our groups were age-matched.

Another significant diagnostic group difference emerged when examining causal RRs that involved central or pivotal elements in the narrative, coded as Relevant causal RRs. Autistic children produced fewer Relevant causal RRs in comparison to their TD counterparts, in line with our predictions. This finding is consistent with prior research observing a reduced focus on the “gist of events” among autistic children and adults (Dindar et al., Reference Dindar, Loukusa, Leinonen, Mäkinen, Mämmelä, Mattila, Ebeling and Hurtig2022; Geelhand et al., Reference Geelhand, Papastamou, Deliens and Kissine2020). Moreover, this result does align with those of Diehl et al. (Reference Diehl, Bennetto and Young2006) (and also Sah & Torng, Reference Sah and Torng2015), where the reduced causal connectedness found in autistic children was related to a decreased likelihood of using key events or the gist of the story to organize their narratives coherently. This reduced focus on central story elements may reflect the challenges autistic individuals experience in adapting speech to suit the listener’s informational needs (Colle et al., Reference Colle, Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright and van der Lely2008; Sah & Torng, Reference Sah and Torng2015) and/or differences in what they perceive to be relevant, which would support the Local Processing account (Dindar et al., Reference Dindar, Loukusa, Leinonen, Mäkinen, Mämmelä, Mattila, Ebeling and Hurtig2022; Kenan et al., Reference Kenan, Zachor, Watson and Ben-Itzchak2019).

On the other hand, no significant differences were found regarding Explicit causal RRs; both autistic and TD children produced a comparable number of causal connectives, in line with studies such as Capps et al. (Reference Capps, Losh and Thurber2000) or Sah and Torng (Reference Sah and Torng2015). This finding confirms our concern that solely analyzing the differences between the causal connections produced by TD and autistic children in terms of the total number of causal connectives may yield misleading and oversimplified results (note that both our study and Capps et al. (Reference Capps, Losh and Thurber2000)’s revealed differences in the types of causal relations, while no differences were found in the overall number of causal connectives).

Finally, the number of RRs expressing Epistemic causality was notably low in both diagnostic groups; as a result, drawing solid conclusions regarding group differences in the production of these RRs proves challenging. As highlighted by Evers-Vermeul and Sanders (Reference Evers-Vermeul and Sanders2011), context plays a crucial role in influencing the reference to different causality domains, and our storytelling task biased for Content relations. Future research should explore the different causality domains employing different methodologies.

Macrostructure scores

Regarding our third and last research question, which concerned children’s macrostructure skills as assessed through the NSS, the ASD group in our study obtained significantly lower scores than the TD group. This finding is in line with studies by King et al. (Reference King, Dockrell and Stuart2014) and King and Palikara (Reference King and Palikara2018), whose participants included autistic and TD children and adolescents matched on age, verbal, and non-verbal ability. Therefore, this result supports and provides further evidence suggesting that autistic children tend to exhibit weaker macrostructure skills in comparison to their TD counterparts (Baixauli et al., Reference Baixauli, Colomer, Roselló and Miranda2016). Furthermore, this finding is consistent with the results observed for the total number of RRs, which suggests that the RR approach captures meaningful aspects of coherence that complement more traditional measures of narrative macrostructure, reinforcing its validity as an assessment tool. Each framework provides unique insights, and their combined application allows for a more comprehensive understanding of narrative abilities in autistic children.

Limitations and future research

Finally, we would like to acknowledge some limitations of the present study. First of all, we observed a relatively low number of causal RRs overall, possibly due to the spontaneous nature of the storytelling task, as it does not inherently prompt the generation of causal RRs. Employing the coding scheme presented in this paper, further investigation with additional data could help to confirm the results obtained in this study. Furthermore, we are also aware that the singularities of the coding protocol employed in this work may limit direct comparisons with other studies in the field. However, our study presents a systematic approach to analyzing and coding narrative coherence based on influential linguistic theories focused on the expression of causal and non-causal relations, which can be easily applied in future research to ensure clear and consistent assessments of narrative coherence.

Conclusion

The present study contributes to the current body of research on the differences autistic and TD individuals exhibit in narrative coherence. In particular, our study adds to the existing literature by undertaking a detailed analysis of the causal RRs produced by Spanish-speaking autistic and TD children, informed by theories of discourse relations. Our results showed that while there was not a significant difference in the overall ability to establish causal RRs between events in a narrative, subtle differences existed in the types of causal RRs produced by each diagnostic group. Autistic children appeared to be less likely than their TD peers to causally connect key events in the story and to use causal language to refer to characters’ intentions or goals. These findings, coupled with the lower total number of RRs (causal and non-causal) and their lower scores on the macrostructure rubric, suggest that autistic narratives manifested lower levels of coherence compared to their TD counterparts.

Replication package

Study materials, data and code have been made publicly available on OSF at the following link: https://osf.io/whg2a/.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the Early Attention service and the Alava Autism Association in Vitoria-Gasteiz, to the Biscayan autism association APNABI in Bilbao, to the school Arizko Ikastola in Basauri (Basque Country, Spain), and to Irene Polo-Blanco, from the Matemáticas y Autismo Lab at Universidad de Cantabria (UC) (Cantabria, Spain), for helping us with recruitment and logistics. We are enormously indebted to all participants and families who generously dedicated their time and support to our research. We would also like to thank Melania S. Masià, from the Universitat de les Illes Balears (UIB), and Laura Vela-Plo, from the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU), for their essential role in double coding the narratives.

Funding statement

This research has been partially supported by project FUNLAT (PID2021-122233OB-I00), funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by “ERDF/EU,” and by the IT1537-22 Research Group (Basque Government).

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.

Appendix

Table A1. Percentage of inter-rater agreement for coding categories and segmentation.

Note: The percentages for rhetorical relation type, causality domain, marking, relevance and ambiguity represent the inter-rater agreement within the set of causal rhetorical relations identified by both coders.

Table A2. Model results for group comparisons in words, c-units, number of different words (NDW) and mean length of c-unit (MLCU).

Note: *=significance code when p < 0.05; **=significance code when p < 0.01; ***=significance code when p < 0.001.

Table A3. Model results for group comparisons in elementary discourse units (EDUs), rhetorical relations (RRs), causal RRs, types of causal RRs, and macrostructure scores.

Note: *=significance code when p < 0.05; **=significance code when p < 0.01; ***=significance code when p < 0.001.