The investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanism has come under intense scrutiny, prompting widespread debate and calls for reform from various stakeholders, including investors, governments, and advocacy groups.Footnote 1 A significant proposal in this discourse involves the introduction of an appellate mechanism aimed at providing an additional layer of assessment for arbitral awards. Advocates of this mechanism argue that it could address the fundamental issues within ISDS and bolster the legitimacy of international investment law.Footnote 2 However, divided between competing objectives of finality and efficiency, divergent views of different states on its utility, and the existing political environment after the crisis of the World Trade Organization (WTO) Appellate Body create uncertainty for the introduction of an appellate mechanism for ISDS. Critical questions arise about how the advantages of such an appellate mechanism can be maximized while mitigating potential risks.

One key consideration in this debate is the issue of inconsistent legal interpretations within the ISDS decisions, which undermines the predictability that investors and states rely upon. Consistency in legal interpretation remains a cornerstone of any adjudicative system. Yet, ISDS tribunals frequently render inconsistent decisions on identical or materially similar treaty provisions, reflecting the fragmented nature of the regime.Footnote 3 These inconsistencies have led to widespread critique and calls for systemic reform, particularly within the framework of the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) Working Group III.Footnote 4 Addressing these inconsistencies through an appellate mechanism could significantly bolster the regime’s perceived legitimacy.

The existing ISDS framework replicates international commercial arbitration in salient ways, such as allowing inconsistent awards and lacking avenues for appeal. There is a limited annulment process only for ISDS proceedings at the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), that too has faced criticism.Footnote 5 This lack of uniformity and logical consistency in ISDS arbitral decisions makes the ISDS system inefficient. It can instil fear of legal action, hindering regulatory initiatives due to the possibility of substantial financial liabilities. To address these challenges, the idea of implementing an appellate mechanism has gained traction, offering a potential solution to enhance the reliability, effectiveness, and predictability of the ISDS mechanism.Footnote 6

Although the inconsistency of outcomes has raised significant concerns about the legitimacy of the ISDS system, which the proposed appellate mechanism aims to address, the existing substantial technical issues can also undermine the credibility of this proposed appellate mechanism. Any proposals for designing an appellate mechanism must ensure a balance of interests between developed and developing countries. Equal participation allows for a diversity of perspectives, which can lead to more balanced and equitable decision-making. It will ensure an equitable development of the ISDS framework, which is equally important to enhance the legitimacy of the system and should be regarded by the UNCITRAL Working Group III as one of the primary objectives of an appellate mechanism. Ensuring that both developed and developing countries have a say in the appellate mechanism will help to maintain the fairness and legitimacy of the ISDS system. It will prevent the perception that the system is biased towards the interests of more powerful developed nations.Footnote 7 This is important because the economic and social contexts of developed and developing countries can be quite different, and these differences need to be considered in investor-state dispute resolution.Footnote 8 This article argues that the absence of a structured method in the existing proposals to evaluate equal participation in the institutional design for the appellate mechanism poses significant challenges.

If all parties feel that they are fairly represented, their confidence in the ISDS system will increase. This is essential for the system’s long-term sustainability and effectiveness.Footnote 9 Historically, developing countries have often been on the receiving end of ISDS claims. Equal participation in the new appellate system will help to address these power imbalances and ensure that the interests of developing countries are adequately protected.Footnote 10 These considerations underscore the critical need to balance party autonomy with centralized oversight and ensure that procedural reforms do not unintentionally disadvantage developing nations. While a permanent appellate mechanism may resolve the issue of inconsistency of outcomes, there are significant concerns regarding the concentration of power it could bring, potentially leading to an unchecked institution that could reshape legal norms in ways that were not initially anticipated. This is exacerbated by the lack of clarity surrounding the selection procedures and specific responsibilities for the appellate mechanism’s members. On the other hand, a fair and balanced ISDS system with equal participation of developed and developing countries will provide a reliable mechanism for resolving disputes. It can encourage more foreign investment in developing countries. This can contribute to economic growth and development.Footnote 11

The financial and temporal burdens in ISDS also undermine its legitimacy by limiting access for low-income states and smaller enterprises. With average costs exceeding USD 6 million for claimants and a tribunal fee averaging USD 1 million, the current process is both financially prohibitive and time-consuming, often taking up to 4.15 years in cases favourable to investors.Footnote 12 To enhance credibility, reforms must ensure that cost-reduction and efficiency are balanced with the fairness of the proceedings, particularly for resource-constrained states. Outcome trends reveal that 47.2 percent of cases result in full or partial investor wins, with awarded amounts averaging USD 482.5 million but often showing inconsistencies.Footnote 13 Systemic issues such as limited arbitrator diversity and inconsistent awards undermine neutrality and equity. Reform must enhance diversity and efficiency and encompass procedural and substantive fairness alongside fairness and equity in the overall design and structural elements of the ISDS framework.Footnote 14

These concerns pose serious complexities to the creation of an ISDS appellate mechanism.Footnote 15 There is a need for a more nuanced and comprehensive analysis of the advantages associated with an appellate mechanism for ISDS.Footnote 16 Key challenges include: (1) the overall institutional design of the appellate mechanism ensuring equal participation and representation by developing countries; (2) the financial burden associated with appellate procedures, particularly for developing countries; (3) the risk of increased procedural delays; (4) the need for impartial and diverse tribunal composition; and (5) reconciling party autonomy with centralized oversight. These challenges form the analytical framework for this article’s examination of the proposed ISDS appellate mechanism’s feasibility and design.

The proposed appellate mechanism, advocated by the European Union (EU) and supported by the UNCITRAL Working Group III, promises to enhance consistency and correctness in ISDS awards.Footnote 17 However, these potential benefits must be weighed against significant concerns highlighted by the historical lack of representation of developing countries and empirical evidence. For instance, the average duration of ISDS proceedings already exceeds three years, and an appellate mechanism could further extend this timeline, exacerbating access to justice concerns.Footnote 18 Moreover, cost implications – where party costs constitute over 90 percent of total expenses – pose significant barriers, particularly for resource-constrained states.

In light of these considerations, this article examines the existing proposals for the ISDS appellate mechanism. This examination provides valuable insights into the ongoing reform initiatives within the UNCITRAL by analyzing the potential consequences within procedural, substantive, and conflict resolution domains.Footnote 19 It is essential to recognize that while the appellate mechanism is a crucial component of broader reform efforts, its impact depends on various factors including its specific scope, powers, and responsibilities and the method of member selection, which is yet to be defined. It is crucial to prioritize balancing the interests of developed and developing countries by introducing special cost allocation rules for developing states, ensuring that the creation of an appellate mechanism does not disproportionately burden developing countries. Likewise, addressing the phenomena of ‘procedural misconduct’ by defending states is equally essential because such practices disproportionately burden small- and medium-sized investors in developing countries.

The UNCITRAL Working Group III acknowledges that while an appellate mechanism may enhance legal consistency, it risks exacerbating procedural delays and cost burdens.Footnote 20 These procedural inefficiencies, combined with structural concerns such as the lack of diversity among arbitrators, undermine the interests of developing countries. Presently, arbitrator representation is skewed towards high-income nations, marginalizing voices from developing states that are often the respondents in ISDS cases.Footnote 21 To ensure equitable access, future reforms must integrate cost-mitigation strategies, address procedural inefficiencies, and promote inclusivity, restoring trust in the ISDS regime and enabling a fairer system for all stakeholders.

The study of institutional design undertaken in this article is timely as the UNCITRAL Working Group III is actively deliberating on draft provisions for an appellate mechanism. Acknowledging the complexity of the reform process, this article does not advocate for any specific international establishment, forum, or institution for an ISDS appellate mechanism. However, it offers a comprehensive overview of the challenges posed to the creation of an appellate mechanism. The contribution of this article is in the form of specific proposals for ensuring a balance of interests between developed and developing countries in various design elements of an ISDS appellate mechanism. This analysis and proposals made in this article aim to contribute meaningfully to the ongoing ISDS reform discussions by highlighting potential issues in the institutional design of an appellate mechanism and suggesting ways to address them. Understanding the trade-offs and imperfections associated with different institutional options is crucial to ensuring an effective reform process and favourable public policy outcomes.Footnote 22

The discourse in this article is structured methodically, commencing with an exposition of the need for an appellate mechanism in Section I. Following that, Section II probes the international perspectives on an ISDS appellate mechanism, analyzing various positions taken by states as compared to the EU’s proposals to the UNCITRAL Working Group III for an ISDS appellate mechanism. Highlighting the political challenges posed to the creation of an ISDS appellate mechanism, this section also presents a brief comparison of the proposed appellate mechanism with the political crisis faced by the WTO Appellate Body. Section III delves deeply into the innovative design elements for an ISDS appellate mechanism, examining the challenges inherent to such an appellate mechanism and exploring potential options to mitigate them. Last, Section IV provides a concise summary and conclusion, encapsulating the overall analysis presented in this article.

I. Why do we need an ISDS appellate mechanism?

The prevailing ISDS system is marred by numerous challenges that pose potential threats to its legitimacy as a fundamental practice within international law.Footnote 23 The absence of a formal application of stare decisis means that specific rulings may appear inconsistent with the broader body of ISDS case law or even contradict established principles of international law. The lack of an appellate mechanism adds to the list of those challenges. As disputing parties have limited avenues for challenging arbitral findings, this potentially leads to a lack of incentive for arbitrators to adhere to a consistent legal doctrine across cases. This potential of substantive inconsistency is exacerbated by the institution’s design factor, which is that arbitrators are appointed on an ad hoc basis, giving rise to pressures that may influence their decisions in favour of the party selecting them. The fact that arbitrators have the incentive of reappointment by the same parties in subsequent cases and can advise clients in multiple arbitrations may lead them to align with the interests of their clients in some instances. These substantive and design factors collectively cast a shadow over the integrity of the ISDS system and warrant careful consideration for solutions within international legal discourse.Footnote 24

An appellate mechanism in the ISDS system is a reform proposal that aims to address concerns such as lack of consistency, coherence, predictability, and correctness of arbitral decisions. An appellate mechanism would allow the parties, or a third party, to challenge the awards issued by arbitral tribunals on certain grounds, such as errors of law or manifest errors of fact, and have them reviewed by a higher body. Some of the advantages of an appellate mechanism have been emphasized in the existing literature. For example, it could enhance the legitimacy and credibility of the ISDS system by providing a higher level of legal scrutiny and quality control over arbitral awards.Footnote 25 It could promote the development and harmonization of international investment law by creating a body of jurisprudence that could guide future arbitrators and parties.Footnote 26 It could reduce the need for annulment or set-aside proceedings before national courts, which could vary in their standards and outcomes and thus increase the finality and enforceability of awards.Footnote 27 Likewise, it could balance the interests of investors and states by ensuring that both parties have an equal opportunity to challenge and defend the awards.Footnote 28 These advantages underscore the necessity of an appellate mechanism, aligning with our position in this article that its implementation can enhance the rule of law, provided it is supported by robust institutional design and stakeholder collaboration, including effective representation by both developed and developing countries.

On the other hand, some disadvantages of an ISDS appellate mechanism have also been identified in the existing literature, which can be summarized as follows. It is claimed that an ISDS appellate mechanism could increase the cost and duration of cases, as the parties would have to bear the expenses of an additional layer of proceedings and face possible delays in resolving their disputes.Footnote 29 It could undermine the autonomy and diversity of the parties and arbitrators, as they would have less freedom to choose the applicable law, the rules of procedure, and the decision-makers for their cases.Footnote 30 It could create new sources of inconsistency and unpredictability, as the appellate body may not have a uniform composition, mandate, or interpretation of the law and may face conflicting or overlapping jurisdictions with other courts or tribunals.Footnote 31 It could also raise practical and political challenges, such as the design, establishment, and funding of the appellate body, the selection and appointment of its judges, and the acceptance and implementation of its decisions by the parties and other stakeholders.Footnote 32 While these challenges are significant, this article argues that a balanced approach to the institutional design of the proposed appellate mechanism can mitigate these risks through innovative procedural reforms and equitable cost-sharing measures, ensuring consistency, efficiency and inclusivity.

The arguments for and against an ISDS appellate mechanism must be evaluated in the context of international investment disputes, governed by the principles of equity, effectiveness, and stability within the ISDS framework, being intricately linked with the foundational principle of the rule of law in international law.Footnote 33 This symbiotic relationship shapes doctrines such as the “Minimum Standard of Treatment” and “Fair and Equitable Treatment” and their contemporary arbitral interpretations.Footnote 34 We believe implementing an appellate mechanism in ISDS can improve the rule of law. However, the actual achievement of this goal will depend on the institutional design of the appellate mechanism. In this regard, both the “legitimacy” and “credibility” of an ISDS appellate mechanism are primary parameters that require satisfaction. Appellate mechanisms can provide security, predictability, and strategic planning but must navigate a complex trajectory to achieve legitimacy.Footnote 35 Likewise, an appellate mechanism must meet the credibility test, which is crucial for the efficacy of a dispute resolution system and imparts intangible advantages, elevating overall legal practice.Footnote 36 From the legitimacy and credibility standpoints, perceived advantages of an appellate mechanism in ISDS can be categorized as “substantial” and “abstract” in nature, as discussed below.

A. Substantial advantages

1. Precision versus scope: ensuring balance in legal interpretation

Scholars and practitioners observe ISDS decisions frequently deviating from precise treaty language, leading to either excessively expansive or unduly restrictive interpretations.Footnote 37 The Metalclad case, for example, emphasizes the need for investment treaties to incorporate more explicit definitions and precise language, ensuring fairness and transparency and preserving the defending state’s autonomy. Balancing investor interests with a state’s right to regulate and effect policy changes calls for a nuanced approach within international investment law, promoting a more equitable global investment landscape.Footnote 38 Advocates of the appellate mechanism argue for its incorporation to redress misinterpretations by introducing an added layer of evaluation.Footnote 39 By mirroring a traditional appellate body, an ISDS appellate mechanism would enhance clarity about appropriate methods of interpretation, ensuring a more accurate delineation of binding obligations.Footnote 40 The WTO Appellate Body offers a precedent for integrating appellate review into international dispute resolution. However, unlike the WTO, the ISDS framework must navigate the additional complexity of bilateral and multilateral treaty obligations, which may limit the uniformity and predictability that an appellate mechanism seeks to achieve. This necessitates a more nuanced institutional design, prioritizing tailored procedural rules over a one-size-fits-all approach. UNCITRAL’s ongoing deliberations in Working Group III emphasize the need for a balanced approach that addresses efficiency, legitimacy, and diverse stakeholder representation.Footnote 41 Similarly, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development’s stocktaking of ISDS reforms highlights the importance of addressing the financial and procedural implications of appellate mechanisms, particularly to accommodate the needs of developing countries and ensure equitable access to justice.Footnote 42

2. Precluding implications of overreach

Arbitral tribunals have the authority to interpret investment agreements and treaties by the Vienna Convention of the Law of Treaties.Footnote 43 However, arbitrators may transgress their jurisdictional boundaries in cases without explicit textual foundation or legal precedent, leading to decisions beyond their authorized purview.Footnote 44 The Impregilo case highlighted the potential overreach of tribunals where the tribunal invoked a “Most-Favoured-Nation Treatment” provision and employed specific language, potentially stretching the boundaries of permissible interpretation.Footnote 45 To mitigate these issues, an ISDS appellate mechanism would ensure that arbitral tribunals adhere to their predefined boundaries and overturn awards that deviate from sound interpretative procedures or treaty text. However, the practical feasibility of this recourse is limited within the existing ICSID review process under the ICSID annulment procedure, which prioritizes integrity and fairness. The challenge lies in balancing due process with consistency and fidelity to the law.Footnote 46

3. Preventing illogical outcomes

One of the critical issues an appellate mechanism could help resolve is the vague and ambiguous nature of treaty commitments. When treaty terms are unclear, arbitrary interpretations can lead to specific meanings that are practically and politically problematic to implement. The Metalclad case highlighted the importance of disclosing relevant information according to the “Minimum Standard of Treatment”.Footnote 47 According to this interpretation, states were obligated to inform investors about potential legal or administrative duties. However, this requirement was deemed excessively burdensome, especially considering the challenges in determining the appropriate notification period for investors.Footnote 48 An appellate mechanism could discourage illogical conclusions by providing nuanced perspectives and contextualizing issues. This contextualization can significantly contribute to policy formulation and enhance the coherence of international treaties and agreements.

4. Clarity and consistency in legal interpretation

Tribunals play a crucial role in understanding the investment-related obligations of investors and states within the broader framework of international legal principles.Footnote 49 However, some tribunals have demonstrated a lack of understanding in this context, leading to misinterpretations or misapplications of treaty articles. A notable example of this occurred in the RDC case, where the tribunal acknowledged relying on an outdated interpretation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) while determining the meaning of the “Minimum Standard of Treatment”.Footnote 50 This decision was made despite discrepancies between NAFTA and the relevant treaty instrument, that is, the Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR).Footnote 51 An appellate mechanism in ISDS can potentially prompt tribunals to identify key aspects of legal agreements meticulously. This anticipation of potential appellate review compels tribunals to systematically analyze these elements within the broader context of international law. Failing precise interpretation by arbitrators, the appellate mechanism serves as a corrective mechanism, inherently predisposed to appreciate the broader contextual underpinnings when issuing decisions after tribunal rulings. This symbiotic relationship encourages a more refined analysis of legal agreements and contributes to the development of robust and contextually informed jurisprudence within ISDS.

B. Abstract advantages

The advantages discussed above centre on the potential of an appellate mechanism to address tangible challenges within current ISDS judgments. Yet, the utility of an appellate mechanism extends beyond resolving overt issues, as it also holds the promise of mitigating subtler but contentious concerns that undermine the legitimacy and credibility of the ISDS system. One such problem revolves around the perceived lack of arbitrator freedom and impartiality, while another pertains to scepticism regarding the authority of the ISDS system, both internally and externally. Advocates for implementing an appellate mechanism argue that a secondary layer of review could rectify these concerns, reshaping the public and institutional perceptions of foreign investment rules. Considering these potential benefits is of paramount importance. In practical terms, the efficacy of the rule of law hinges significantly on its implementation, a process intricately linked with societal institutions and legal frameworks. Introducing an appellate mechanism into the existing ISDS framework can, therefore, offer additional advantages, reinforcing the contested domain of law and enhancing the overall functionality of ISDS.

Procedural fairness in the selection of arbitrators is a prime concern in this regard. The contentions surrounding partiality and bias within ISDS primarily stem from the arbitrator appointment process, particularly when the parties involved are empowered to select them. This system allows limited constraints on factors such as preconceived legal judgments and subsequent reappointments, creating potential biases to manifest.Footnote 52 Notably, in the ad hoc model where arbitrators are reimbursed based on hourly rates, a strong inclination toward perpetuating this approach to appointments emerges, raising concerns about the neutrality of decisions. Reappointments further complicate matters, as arbitrators may become predisposed to favour the interests of the appointing parties over rendering accurate judgments.Footnote 53 Four fundamental biases or impacts are particularly salient within ISDS:Footnote 54

1. Selection of arbitrators: Parties’ ability to select arbitrators allows them to choose individuals favourably disposed toward their case, potentially compromising impartiality.

2. Affiliation effect: Arbitrators appointed by parties may exhibit unconscious bias, leading them to favour the nominating party, compromising their impartiality and independence.

3. Compensation effect: The prospect of reappointment and financial incentives can influence arbitrators’ decisions. This effect can be intensified by the remuneration received from appointments and other forms of capital, such as social standing.

4. Cognitive impact: Various factors, including procedural norms, diplomatic standards, and societal ideals, shape the pool of potential candidates. This influence may lead to prioritizing certain legal ideals, such as predictability, over others, such as fairness, exacerbating biases. External pressures from peers and conformity further compound this issue.

Proponents of an appellate mechanism posit that establishing a permanent body can mitigate biases arising from the nomination process and the informal structure of arbitral tribunals.Footnote 55 A permanent group of members, selected for fixed terms irrespective of tendencies evident in judgments, can curtail the impact of arbitrators’ selections, affiliations, and compensation. Additionally, diversifying appellate mechanism membership could mitigate the epistemic and cultural influences, fostering a more balanced and unbiased adjudicative process.Footnote 56

Mitigating the challenges above and bolstering the legitimacy and credibility of ISDS mechanisms may entail the establishment of an appellate mechanism staffed by impartial and tenured professionals. These individuals would operate autonomously, free from affiliations with arbitrators and external stakeholders such as law firms.Footnote 57 Refining the selection processes of arbitrators and severing their affiliations with disputing parties can cultivate an atmosphere of fairness and objectivity, mirroring the judicial functions inherent in traditional legal systems.Footnote 58 In a parallel vein, akin to the structure of the appellate mechanism, which is devoid of reappointment incentives, this analysis seeks to establish a framework that is both consistent and predictable, thereby mitigating potential biases.

II. International perspectives on the ISDS appellate mechanism

This section presents an analysis of positions taken by states on the proposed ISDS appellate mechanism. Specifically, based on key aspects of state submissions to UNCITRAL, we reflect on how positions taken by different states align with or differ from each other, as well as with the EU’s proposal to UNCITRAL on the creation of an appellate mechanism for ISDS. This section then compares the potential ISDS appellate mechanism and the WTO Appellate Body, considering whether the cessation of the WTO Appellate Body’s function in 2019 impacts the political support for the ISDS appellate mechanism.

A. Analysis of state positions on the ISDS appellate mechanism

As the ISDS has faced criticism for its perceived lack of consistency, transparency, and fairness, the idea of an appellate mechanism within ISDS has emerged as a potential reform to address these concerns. However, the ISDS appellate mechanism debate reveals a spectrum of perspectives shaped by economic interests, policy priorities, and international dispute resolution experiences of different states.

The EU has staunchly supported a structured and transparent appellate mechanism. Since 2015, the EU has advocated for a multilateral investment court with an appellate body to enhance the legitimacy and consistency of ISDS.Footnote 59 Drawing inspiration from the WTO Appellate Body, the EU envisions a permanent multilateral investment court with an impartial judiciary, a clear selection process for judges, and transparent procedures. In its submission to UNCITRAL, the EU outlined its proposal emphasizing consistency and judicial independence as fundamental pillars of reform.Footnote 60 However, developing countries have expressed reservations on the EU’s proposal.

In its submission to UNCITRAL Working Group III, the Government of Indonesia emphasized the need for a balanced reform of the ISDS mechanism that protects both investors’ rights and states’ regulatory autonomy. Indonesia underscored that the procedural and substantive elements of ISDS are inherently intertwined, cautioning against any reform that might inadvertently increase costs or extend the dispute resolution timeline.Footnote 61 Indonesia argued that procedural law is inherently substantive and vice versa, making it difficult to separate the two without undermining the effectiveness of the ISDS mechanism. Additionally, Indonesia raised several other critiques against the proposed appellate mechanism for ISDS. Indonesia highlighted the issue of exaggerated claims by investors, which can lead to significant economic pressure on developing states. It suggested establishing guidelines to curb such risks, including a checks-and-balances mechanism for claims and a code of conduct for arbitrators. Indonesia expressed concern that the threat of ISDS could lead to a “regulatory chill”, where governments hesitate to undertake legitimate regulatory measures for fear of legal claims by investors. This could hinder the government’s right to regulate in the public interest. Indonesia proposed several options for reform, including providing more safeguards in both substantive and ISDS provisions, allowing investors to make claims to international arbitration only after exhausting local remedies, requiring separate written consent for investors to make ISDS claims, and introducing mandatory mediation as an alternative dispute resolution method before proceeding to ISDS. These critiques reflect Indonesia’s broader concerns about how creating an appellate mechanism alone will resolve the issues with the current ISDS mechanism and suggest a more balanced and equitable approach to ISDS reform.

The submission by Chile, Israel, and Japan emphasizes a flexible “suite” approach to ISDS reform, allowing states to adopt a tailored mix of procedural measures based on their unique needs.Footnote 62 This approach offers tools such as early dismissal of frivolous claims, enhanced arbitrator ethics, and mechanisms for consistent treaty interpretation through non-disputing party submissions. It emphasizes preserving procedural flexibility to prevent prolonged disputes and rising litigation costs. While these states did not outright reject an appellate mechanism, they cautioned against any reform that might inadvertently prolong disputes or raise costs, particularly for developing countries. This approach contrasts with more rigid reform proposals by offering a customizable and pragmatic pathway to ISDS reform.

Likewise, in their submission to UNCITRAL Working Group III, developing nations such as Chile, Mexico, and Peru, who are also joined by Japan, have prioritized systemic reforms through procedural flexibility rather than a rigid appellate mechanism.Footnote 63 They cautioned against any reform that might inadvertently prolong disputes or raise costs, particularly for developing countries.

South Africa, by contrast, has taken a more fundamental approach, advocating for the replacement of ISDS with alternative dispute settlement mechanisms.Footnote 64 South Africa’s submission emphasizes the need for a comprehensive and inclusive approach to ISDS reform, focusing on sustainable development and public policy issues. Unlike other countries that proposed a flexible “suite” approach, South Africa advocates for systemic reform that integrates human rights and environmental considerations into investment treaties. They stress the importance of policy space for host states to regulate in the public interest and propose alternatives to ISDS, such as dispute prevention policies, alternative dispute resolution, and the exhaustion of local remedies. South Africa also highlights the need for investor obligations and counterclaims to balance the rights and responsibilities of investors and states. While they acknowledge the potential benefits of an appellate mechanism or a multilateral investment court, they caution against reforms that do not address the substantive inequities and imbalances in the current ISDS system. Overall, South Africa’s approach contrasts with other submissions by emphasizing the integration of sustainable development goals and human rights into the investment dispute resolution framework.

China, on the other hand, has adopted a more flexible but cautious approach.Footnote 65 While China has acknowledged the potential benefits of an appellate mechanism in improving legal certainty, it emphasized the importance of state sovereignty and the diversity of legal systems. China’s proposals for reform include establishing a permanent appellate mechanism to improve error-correcting processes, retaining the right of parties to appoint arbitrators, improving rules for arbitrators, promoting alternative dispute resolution measures, implementing pre-arbitration consultation procedures, and ensuring transparency in third-party funding. China advocates for a multilateral approach to ISDS reform, supporting joint efforts of Member States and cooperation with international organizations to develop multilateral rules. Overall, China’s approach focuses on enhancing the stability, predictability, and fairness of the arbitration process while maintaining the core functions of the ISDS mechanism. In line with its overall approach of propagating incremental adoption of international law norms by developing countries,Footnote 66 China has advocated for a gradual, step-by-step reform process that allows states to opt in according to their circumstances and preferences.Footnote 67

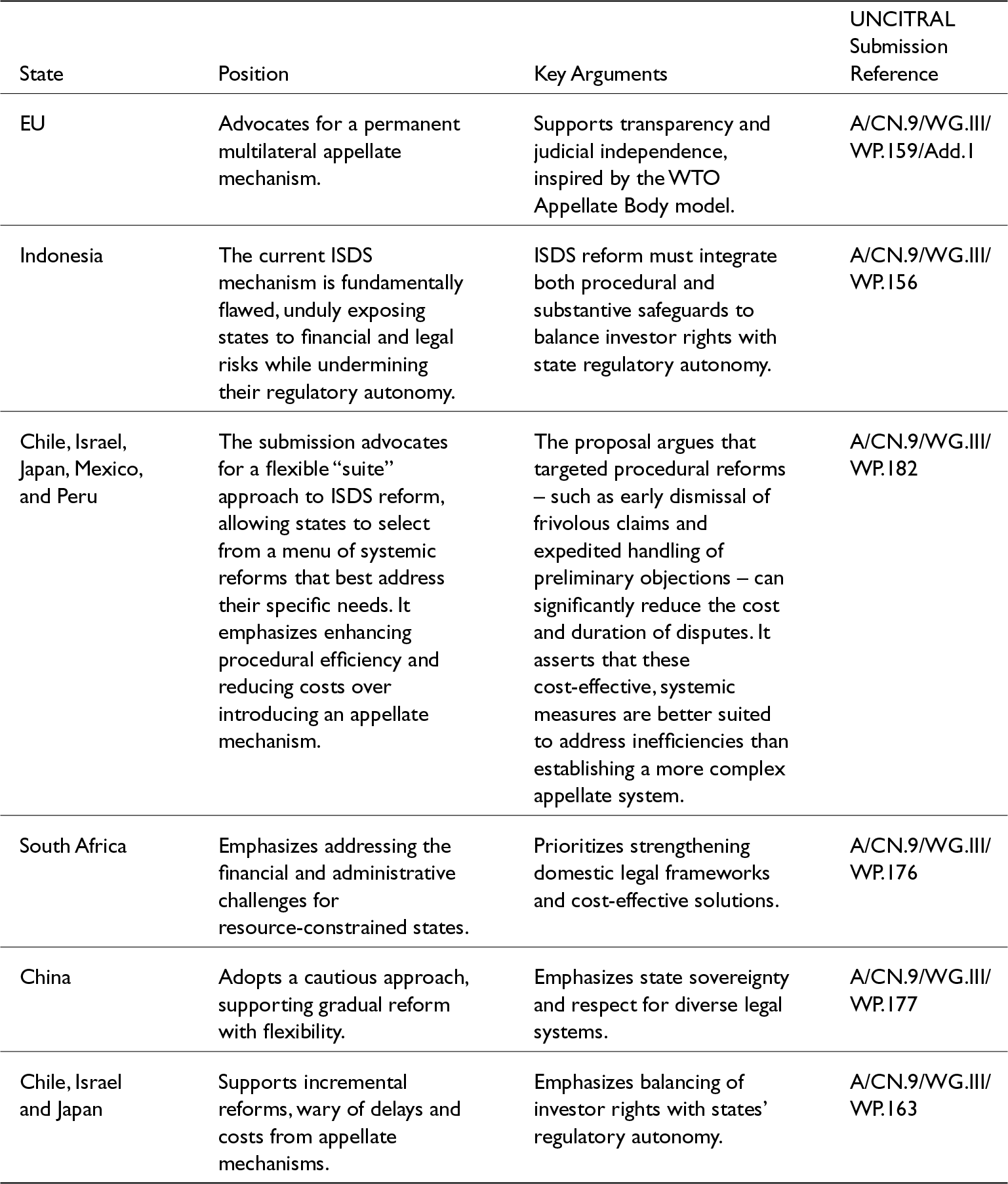

Table 1 below presents a comparative chart of divergent priorities and interests of these states on the proposed ISDS appellate mechanism.

Table 1. Major states’ positions on ISDS appellate mechanism.

Several alignments and divergences emerge when comparing these state positions with the EU’s proposal. The EU and China recognize the potential advantages of an appellate mechanism in enhancing consistency and predictability in investment arbitration. However, they also differ in their approaches, with the EU advocating for a comprehensive and immediate establishment of an appellate mechanism (which the EU refers to as a multilateral investment court). At the same time, China prefers a flexible and incremental reform process. In contrast, Japan, along with Chile and Israel, shares concerns about the need for reform but remains cautious about the practical implications – such as increased costs and delays – that a rigid appellate system might entail.

Effective representation typically requires broad and diverse participation to ensure that the interests and concerns of all stakeholders are adequately addressed. The exact number of developing countries actively participating in UNCITRAL Working Group III discussions varies by session. However, it is known that a significant portion of the 116 states involved includes developing countries. Based on the latest sessions of UNCITRAL Working Group III, approximately 40 developing countries actively participated in the discussions. This includes countries from Africa, Asia, and Latin America, reflecting a broad interest in the reform process.

B. Comparison with the WTO appellate body

The potential ISDS appellate mechanism draws parallels with the WTO Appellate Body, particularly in its aim to enhance consistency and predictability in rulings. Incidentally, the cessation of the WTO Appellate Body in 2019 has considerable implications for the political support of an ISDS appellate mechanism. The WTO Appellate Body, once a cornerstone of the multilateral trading system, ceased to function effectively due to the inability to appoint new members, primarily because the US blocked appointments over concerns of judicial overreach and procedural issues.Footnote 68 This development has eroded confidence in multilateral adjudicative mechanisms and underscores the political challenges inherent in establishing and maintaining such bodies.Footnote 69

The paralysis of the WTO Appellate Body serves as a cautionary example, reinforcing scepticism among powerful states like the US regarding the delegation of adjudicative authority to international institutions.Footnote 70 It highlights the risks of political disagreements undermining the effectiveness of appellate mechanisms,Footnote 71 thereby affecting the enthusiasm of some states in supporting similar structures in the ISDS context. Although the EU appears to remain steadfast in its commitment to judicial settlement of international disputes,Footnote 72 the challenges faced by the WTO Appellate Body provide lessons for designing a more robust and resilient appellate system for investment disputes, with clearer mandates and safeguards against political interference. The cessation of the WTO Appellate Body has introduced additional considerations into the debate on the creation of an ISDS appellate mechanism, highlighting the potential vulnerabilities of international appellate mechanisms to political disputes. While it may have dampened the political support for an ISDS appellate mechanism among some states, powerful proponents like the EU continue to argue for its necessity in fostering a fair and predictable investment environment.Footnote 73

In the current political climate, a balanced institutional design for an ISDS appellate mechanism that addresses the diverse concerns and priorities of both developed and developing countries can help foster a broader consensus. As favoured by China, adopting a flexible and incremental approach can accommodate the varying levels of readiness and acceptance among countries. This allows for gradual adjustments and reforms, making it easier for both developed and developing nations to adapt without feeling overwhelmed by immediate, comprehensive changes. This approach, backed by a structurally balanced appellate mechanism, should effectively address the sovereignty and national interest concerns highlighted by the US. Simultaneously, it would enhance consistency and predictability in investment arbitration, aligning with the common goals of the EU and China.

The following section presents specific proposals to ensure a balanced institutional design for an ISDS appellate mechanism. These proposals aim to bridge the gaps between different national positions, fostering a more cooperative and mutually acceptable international investment dispute resolution system.

III. Institutional design for an ISDS appellate mechanism

A multilateral instrument is under consideration to harmonize ISDS reforms globally, offering provisions and mechanisms for states to adopt and create a cohesive framework. This instrument seeks to address systemic issues and promote uniformity in investment dispute resolution.Footnote 74 Recent Working Group III meetings and their accompanying annotated agendas provide valuable insights into deliberations and progress.Footnote 75 These documents detail the topics discussed, decisions made, and future work plans, offering a comprehensive view of the reform trajectory.Footnote 76

The complexity associated with establishing an appellate mechanism in the context of ISDS stems from its inherent impracticality and the imperative need to rectify the lack of neutrality within the ISDS framework. A fundamental inquiry arises: can an increased number of hearings serve as a viable solution to this challenge? Or would it inadvertently exacerbate the issues of prolonged timelines and heightened financial burdens? This inquiry necessitates carefully examining the complicated balance between accommodating the dual public-private nature of investor-state disputes and reconciling the divergent demands of party autonomy and centralized control. The design of the appellate mechanism must balance party autonomy with the efficiency needed to preserve legitimacy. Addressing issues such as arbitrator selection and time constraints will be key to ensuring the system is accessible without undermining the legitimacy of the dispute resolution process. It requires a nuanced approach that balances practicality, fairness, and cost-effectiveness, considering the tribunal’s composition, expeditious adjudication, and affordability for all stakeholders involved.

A. Ad hoc or permanent appellate tribunal

The “revolving door” phenomenon of arbitrators, where the same individuals frequently serve across multiple tribunals, raises significant credibility concerns. This practice can undermine impartiality and erode the perceived legitimacy of ISDS, especially when arbitrators may feel influenced by party affiliations or their future reappointments.Footnote 77 Ensuring the appellate tribunal’s independence and impartiality is crucial for effectively addressing these issues and upholding its functions.

The institution’s nature shapes the tribunal’s composition and alters the arbitrators’ intent. Two views exist: interim or ad hoc and permanent appellate tribunals. Permanency, having a stable and enduring framework, fosters consistency and clarifies norms, which is crucial in uncertain investment contexts where legal frameworks, regulatory environments, or geopolitical landscapes are subject to frequent changes or ambiguity. The repetition of similar cases in investment disputes, along with unclear interpretations of rules and the public law aspect of ISDS, requires a permanent tribunal for the appellate mechanism instead of an ad hoc tribunal to resolve issues of legitimacy and inconsistent decisions.Footnote 78 Ad hoc arbitration in investor-state disputes has shadowed the legitimacy and compromised neutrality of arbitrators, which will remain a concern in ISDS appeals. Repeated appointments in this model can impact award neutrality.

In addressing the legitimacy and neutrality challenges inherent in ad hoc arbitration, a novel approach involves synergizing arbitrators’ aspirations for reappointment with a comparative public law mindset.Footnote 79 Although the acceptance of comparative public law by states and society has not influenced arbitrators’ decisions, leveraging their desire for continuity can steer them towards a public law path of analysis.Footnote 80 This strategic alignment can be achieved despite necessitating an appellate body, enhancing consistency in ISDS awards. However, this tactic should coincide with comprehensive institutional reforms. The institutional design significantly shapes the landscape of ad hoc arbitration, and integrating public law mechanisms becomes imperative for compatibility.Footnote 81 By combining arbitrators’ motivations with systemic changes, the investment in institutional reform becomes an essential precursor, ensuring a harmonious blend of arbitrators’ expertise and the application of public law principles in arbitration proceedings.

Introducing a permanent appellate tribunal requires that arbitrators abstain from affiliations with other organizations, ensuring unwavering neutrality. In this setup, arbitrators’ focus transcends recurrent appointments, honing in on the case’s legal intricacies. The permanency guarantees insulation from external influences, fostering a reliance on established precedents and bolstering judicial independence, akin to the robust framework of the WTO appellate mechanism.Footnote 82 Notably, the shift towards a permanent appellate tribunal recalibrates arbitrators’ attention from party affiliations to shaping influential legal precedents. This contrasts with commercial arbitration and underlines the tribunal’s dedication to unwavering legal application and institutional prestige. A permanent tribunal forges stable rules by championing consistency across numerous cases, mitigating arbitrator discretion.Footnote 83 Crucially, this structure curtails conflicts of interest and potential injustices, underscoring the imperative need for concrete, permanent mechanisms that guide and confine arbitrators’ application of the law, an indispensable endeavour amid the inherently nuanced landscape of ISDS.Footnote 84

Integrating comparative public law principles into investment arbitration presents a pivotal opportunity for enhancing fairness and coherence.Footnote 85 The proposal to establish a permanent appellate tribunal for ISDS aims to enhance fairness, consistency, and transparency. This reform envisions a permanent appellate body capable of interpreting treaties with a public law approach, offering a more consistent and impartial mechanism for resolving investment disputes. By redefining the institutional design of investment arbitration, this reform proposal seeks to balance the interests of investors and states, foster predictability, and ensure prudent dispute resolution. Additionally, the proposal emphasizes the creation of a permanent body to address concerns about impartiality and consistency in ISDS, detailing the selection process, qualifications, and ethical standards for tribunal members.Footnote 86 Reforming procedural aspects of ISDS is a central focus of ongoing efforts, addressing issues such as transparency, third-party participation, and the conduct of proceedings. Draft provisions provide detailed explanations and rationales, facilitating a deeper understanding of the proposed changes.Footnote 87

The proposed establishment of a permanent appellate tribunal aims to address the inconsistencies and lack of predictability in the current ISDS system, which relies on ad hoc arbitration panels. A permanent appellate tribunal would provide a permanent expert body that enhances fairness, coherence, and transparency in adjudication. Integrating comparative public law methodology, a permanent appellate tribunal can create a more consistent framework for interpreting treaties and resolving disputes, drawing on established norms from various legal systems.Footnote 88 This approach would balance investor protections with states’ regulatory rights, improving the overall predictability and legitimacy of ISDS outcomes.Footnote 89 Furthermore, the establishment of a permanent appellate tribunal would contribute to greater transparency and accountability, offering a more equitable process through permanent tribunal members and consistent decision-making.Footnote 90

B. Selection of appellate tribunal members

In establishing a permanent appellate tribunal akin to the WTO, addressing complexities in composition is vital. The details of member selection pose significant challenges, requiring careful consideration and sensitivity. The selection process for appellate tribunal members necessitates a nuanced approach, intertwining legal and domestic policy considerations for effective implementation.

1. The selection criteria for appellate tribunal members

A novel perspective in this context highlights the intricate balance necessary in arbitrator selection, particularly in ISDS. Emphasizing Lord Denning’s wisdom, choosing arbitrators is pivotal in dispute resolution, demanding independence, impartiality, and profound legal acumen.Footnote 91 Stringent procedural criteria are imperative to prevent the appointment of potentially biased arbitrators. The appellate mechanism enhances decision consistency and influences various aspects of the first-instance interim tribunal, including the adequacy of arbitral award reasoning, arbitrators’ neutrality, and appointments. The existence of the appellate mechanism itself binds the interim tribunal. At the same time, the review function improves arbitration quality and disciplines arbitrators; the mechanism’s design guards against external influences. However, potential biases exist in the appellate tribunal’s composition. Guided by their position, members spontaneously uphold a higher standard of reasoning and neutrality, ensuring legal understanding prevails.

Canada-European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA)Footnote 92 and European Union–Vietnam Investment Protection Agreement (EVIPA)Footnote 93 share common principles in the selection of members for their appellate tribunals. CETA mirrors the rules for appointing members of the WTO Appellate Body, requiring judicial qualifications or recognized expertise in relevant fields and adherence to internationally accepted norms. In contrast, EVIPA stipulates that members must be the “highest judicial officer” in their home country. For the ISDS appellate body, ensuring impartiality and expertise is paramount, necessitating permanent members with a strong judicial reputation, professional competence, and specialized knowledge in investment law, with a preference for former judges from domestic appellate mechanisms. Reference to the practice of “high-ranking” appellate body arbitrators in EVIPA further supports this criterion. The arbitral tribunal within the appellate mechanism should consist of qualified individuals with strict restrictions on other professional activities, recognized expertise in law, and a background in public law, aligning with the mechanism’s purpose of thorough legal scrutiny in the context of investment treaties and international investments.

2. How to select appellate tribunal members

As per Article 3 of the ICSID Convention,Footnote 94 the centre is mandated to have mediators and arbitrators appointed by each state party, along with the chairman of the centre’s administrative committee. However, the appellate mechanism should be modelled after the EU’s approach to the appeals system adopted in CETA and the WTO appellate body.Footnote 95 Furthermore, the investment chapter in the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) outlines the process for selecting judges for the Tribunal of First Instance, which provides another practical example that can be considered.Footnote 96 Article 9 of the TTIP’s investment chapter provides that the Tribunal will comprise five judges from EU Member States, five from the US, and five from nationals of third countries. Article 9(6) further states that the Tribunal shall hear cases in divisions consisting of three Judges, of whom one shall be a national of a Member State of the European Union, one a national of the United States and one a national of a third country. The division shall be chaired by the Judge who is a national of a third country.Footnote 97 The CETA provisions are similar to those of the TTIP’s investment chapter.Footnote 98 Article 17 of the WTO’s Dispute Settlement Understanding requires the Appellate Body to comprise individuals broadly representative of WTO membership but not affiliated with any government.Footnote 99 Compared with the above two options, the design of the WTO appellate mechanism is worth consideration. This is because the appellate mechanism needs to be widely accepted.

3. Adequate representation of different stakeholders

Although only some countries may initially support the establishment of the appellate mechanism, the design of an ISDS appellate tribunal should prioritize balancing the representation of developed and developing countries and capital-exporting and importing countries in its composition.Footnote 100 The different regional and legal patterns and the conflicting interests of investors and countries, capital-exporting and capital-importing countries, the local public as key stakeholders, and relevant interest groups should also be considered.Footnote 101

4. Number, appointment process, and tenure of appellate tribunal members

The number of appellate tribunal members could be fifteen, as in CETA and TTIP’s investment chapter, with the selection committee interviewing and negotiating a recommendation. The candidate will not be approved and appointed if the disputing parties disagree with the recommendation. The proposed term of office for the judges of the Tribunal of First Instance in TTIP’s investment chapter is six years,Footnote 102 while the term of office of CETA members is five years,Footnote 103 and the term of office of WTO Appellate Panel members is four years,Footnote 104 all renewable once. The ISDS appellate tribunal could follow these examples and set the term of office at five years, renewable once.

If a fair and transparent process is established for the selection of members of the appellate tribunal, the tribunal constituted through that process will be more willing to undertake measures and rules that enhance greater transparency, which will enhance not only the legitimacy and transparency of the mechanism but also satisfy the requirements of due process. These measures and rules drawn up by the appellate tribunal will be more flexible and up-to-date than the case-by-case appointment tribunals in the present ISDS system.Footnote 105 With a formal process for deciding on the appointment of appellate adjudicators, this model would be more transparent than the original ISDS commercial arbitration designation mechanism, which requires establishing a transparent selection process and a selection committee with the Contracting States recommending candidates.

C. Mixed (ad hoc and permanent) composition of members in appellate tribunal

Selecting members marks just the outset of resolving disputes through the ISDS appellate mechanism. It is pivotal to deliberate whether an appellate tribunal should comprise solely permanent members or a chosen subset. This decision must align with established norms for arbitrator appointments in the first instance, mindful of the ISDS appellate mechanism’s unique blend of public and private dimensions.

In ISDS, diverse methodologies have emerged in arbitrator appointment practices, each offering unique advantages and challenges. The conventional avenues include cross-appointments, ad hoc selections, circular appointments, institution-driven choices, and hybrid models integrating party and institutional appointments.Footnote 106 A notable innovation is the random appointment approach introduced by the TTIP’s investment chapter, which injects an element of unpredictability into the arbitration tribunal’s composition.Footnote 107 While this unpredictability poses challenges, circular appointments offer a degree of foresight. Disputing parties can anticipate arbitral tribunal’s compositions by scrutinizing past cases.

Notably, the emergence of party-appointed and institution-appointed approaches to arbitrators has reshaped the landscape. Institution-appointed models, where the institution designates the presiding arbitrator while parties choose the remaining arbitrators, have gained traction, enhancing transparency and accountability.Footnote 108 Recent treaties like CETA have embraced this approach, enabling treaty-based institutions to select the presiding arbitrator from a limited pool when parties disagree. This shift significantly influences the parties’ selection process, compelling them to navigate within defined parameters. Consequently, the evolving landscape for an appellate tribunal demands a nuanced understanding of these methods, encouraging stakeholders to adapt and strategize effectively within the framework of these innovative appointment mechanisms. For instance, the ICSID appellate mechanism proposes an institutional designation with a fifteen-member appeals panel. The Administrative Committee will select and appoint the panel members. At the same time, the Secretary-General will determine the panel’s Composition for each case, typically consisting of three members unless the parties agree otherwise.Footnote 109

The process of appointing arbitrators in ISDS involves complex considerations, balancing party autonomy, institutional authority, and the demands of a public law context.Footnote 110 The current debate centres around how parties should be allowed to exercise their autonomy versus institutional intervention in the selection process. The nature of the appellate mechanism significantly impacts this power dynamic, often limiting party autonomy and necessitating institutional arrangements.Footnote 111 There are divergent approaches to existing ISDS frameworks. Some advocate for a fixed composition, eliminating party choice, while others propose a compromise where parties can select arbitrators from a pool of permanent members. While preserving some autonomy, the latter approach faces criticism for potentially constraining party control.Footnote 112 This tension between autonomy and control becomes more pronounced than in ad hoc arbitration, where parties enjoy more freedom in arbitrator selection.

However, the concept of party autonomy is constrained by the public law essence of investment disputes.Footnote 113 This inherent limitation is geared toward ensuring due process and fairness and necessitates a delicate balance. One solution is allowing parties to select an appellate tribunal from a predetermined pool, preserving a measure of autonomy while respecting the hybrid nature of ISDS. The pivotal role of appointments of appellate tribunals cannot be overstated; it significantly impacts their diligence and impartiality. In this context, reputation emerges as a powerful motivator. Mindful of their perceived bias, appellate tribunal members may struggle to secure appointments just as they do with the appointment of the arbitral tribunal itself, compelling them to uphold fairness and justice. However, to maintain credibility, it is imperative to establish strict time limits for appointments and clear criteria for challenging arbitrators. The measures aim to reduce delays and promote transparency in the ISDS framework, balancing party autonomy, institutional authority, and public law, ensuring a fair and acceptable appellate mechanism for international investment disputes.

D. Ethical guidelines and incentives for appellate tribunal members

The professional ethics of arbitrators are crucial for the legitimacy and credibility of the ISDS mechanism. A higher ethical standard for arbitrators would reinforce these considerations and protect public interest.Footnote 114 However, the ad hoc system of arbitrator appointments in the current ISDS has limitations in optimizing the award process, leading to the arbitrator neutrality problem and public interest challenge.Footnote 115 The ethical requirements for members of the arbitral tribunals are higher in both CETA and TTIP, emphasizing that personal interests, external pressures, and political considerations should not influence arbitrators.Footnote 116

As an ISDS appellate tribunal will be a more public law judicial body, its members should have a higher standard of ethics than in commercial arbitration.Footnote 117 The code of ethics for an appellate tribunal should be distinguished from other commercial arbitration codes, incorporating the public interest into the code of ethics. Members of appellate tribunals should adhere to other codes of conduct on issues such as disclosure, neutrality, and confidentiality.Footnote 118 The presence of full-time arbitrators in international investment law introduces concerns regarding economic incentives. Advocates argue that investment treaty norms promote investment by mitigating investment risk and lowering dispute-related costs. However, the economic impact on ISDS arbitrators prompts questions about whether reputational concerns sufficiently replace financial incentives.Footnote 119 The potential incentive for arbitrators to expand the ISDS mechanism into a for-profit mechanism raises concerns about potential ethical issues for arbitrators.

Concerns about economic incentives for arbitrators in investment arbitration also require attention. While some argue that investment treaty norms reduce dispute-related costs and risks, others highlight the potential for arbitrators to exploit the system for financial gain. To mitigate this, remuneration structures such as those in TTIP, which combine a fixed retainer and variable fees, can balance financial security with fairness and neutrality. Remuneration can be set comparable to the WTO (approximately USD 200,000 annually), which is supplemented by per diem fees.Footnote 120 This remuneration structure ensures consistency, balancing financial efficiency with adjudicative demands. Likewise, the judges of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) receive a base salary supplemented by additional compensation for ad hoc services. This dual approach maintains judicial independence and ensures financial concerns do not compromise decision-making.Footnote 121 Similarly, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) offer examples of how remuneration arrangements can be managed in permanent adjudicative bodies. Judges at the ICJ receive a fixed annual salary determined by the United Nations. As of 2023, this base salary amounts to USD 191,263, with the President receiving an additional special supplementary allowance of USD 25,000.Footnote 122 Judges of the ECtHR receive a fixed annual salary, which the Council of Europe determines.

These remuneration arrangements reflect the significant responsibilities and workload of the tribunal associated with their roles. The proposed ISDS appellate mechanism could adopt a similar model to enhance its credibility and efficiency. The ISDS Appellate Tribunal’s reputation as a permanent arbitrator, contributing to rule harmonization, attracts professionals to prioritize reputation over financial gains. Aligning with the WTO model, this reputation-centric approach motivates arbitrators to make impartial decisions. A crucial consideration is establishing a recusal system for permanent arbitrators, especially when cases involve their country of nationality.Footnote 123 The reputation of an ISDS appellate tribunal member and its function of harmonizing and reshaping rules would be attractive to potential arbitration professionals.

E. Time limit control of ISDS appellate mechanism

A key critique of implementing an appellate mechanism is that it may exacerbate procedural delays. Such delays undermine the system’s legitimacy, particularly for developing countries facing financial constraints and requiring timely dispute resolution. Any appeal process must be carefully structured to ensure speed without sacrificing due process. Investment arbitration, a process fraught with complexities and various involved parties, often results in a final award taking four to five years to be rendered.Footnote 124 This extended timeframe is a core issue within the ICSID and the broader international investment dispute resolution field.Footnote 125 In adherence to prevailing conventions, it is customary for an arbitration hearing to endure for approximately 3.3 years before a conclusive resolution is reached.Footnote 126 However, where one of the parties opts for the annulment of the award, an additional period of eighteen months is typically appended to the proceedings, while WTO disputes typically take six to nine months.Footnote 127 However, the length of procedures varies due to the complexity of investment disputes and the involvement of different parties, arbitrators, lawyers, witnesses, and experts. As such, addressing the issue of time efficiency within investment arbitration remains a critical area for improvement.

The delays inherent in investment arbitration often stem from the intricate nature of involving states as respondents.Footnote 128 Unlike private parties, states must navigate complex bureaucratic channels, engaging senior officials and government agencies to formulate a cohesive defence strategy. This intricate decision-making process is rooted in political and practical realities, considering that arbitral tribunals typically grant states a grace period. When contemplating the establishment of an appellate mechanism, it is imperative to focus on its efficiency. A streamlined process enhances legitimacy and ensures timely resolution, safeguarding the parties’ rights. However, it is crucial to strike a balance. While efficiency expedites justice, the appellate process must remain firmly grounded in principles of due process.Footnote 129 In light of the absence of detailed rules in agreements like CETA and TTIP, it becomes vital to dissect the delay nodes in ICSID proceedings and glean insights from mechanisms such as the WTO and domestic justice systems to craft an effective and fair ISDS appellate mechanism.

1. Time limit for application and registration

To enhance the efficiency of international arbitration procedures, it is imperative to address the delays encountered in the preliminary stages of the process. A significant source of these delays lies in examining the case and determining the arbitral tribunal’s jurisdiction, often leading to protracted procedural timelines. One viable solution is to implement an “agreed-upon” appellate mechanism that can help speed up the filing process by eliminating the need for a thorough jurisdictional review.

Under Article 36, paragraph 3 of the ICSID Convention, the Secretary-General must assess whether ICSID has jurisdiction over the disputes upon request.Footnote 130 Introducing an appellate mechanism where parties mutually consent to its jurisdiction would prevent the necessity for a stringent jurisdictional review during the filing process. Once the parties submit the required appeal materials within a stipulated time frame, they can promptly initiate the appeal procedure. To ensure swift progression, it is essential to impose legal deadlines for both parties to file appeals after receiving the award. Drawing inspiration from existing models such as CETA and TTIP, which limit a ninety-day appeal period, a deadline would encourage parties to promptly exercise their right of appeal and seamlessly integrate the initial arbitration and appeal processes.Footnote 131

However, introducing an appellate mechanism raises questions about the appealability of jurisdictional objections. It becomes crucial to determine whether such complaints can be appealed and, if so, how to expedite their review during the appeal stage to prevent prolonged procedures. To address this concern, a careful examination of arbitration filing and jurisdictional review is necessary in the first instance. Paragraph 5 of Article 41 of the ICSID Arbitration Rules permits the arbitral tribunal to judge whether a claim lacks legal interest, including assessing ICSID’s jurisdiction.Footnote 132 To prevent redundancy and conflicts, it is imperative to differentiate between the Secretary-General’s filing review and the tribunal’s review. Ensuring consistency and efficiency in arbitration proceedings requires a nuanced approach to the Secretary-General’s role. To avoid unnecessary delays, the Secretary-General’s review should focus on excluding cases clearly beyond the dispute settlement’s scope, not conducting substantive reviews. To streamline the process, a fixed thirty-day review period is proposed, with the option for automatic filing if no decision is reached. Parties should retain the right to appeal within ten or fifteen days if the Secretary-General does not file a case. Addressing concerns of unqualified cases, allocating expenses becomes pivotal, with plaintiffs bearing costs for non-jurisdictional claims. The appellate body should focus on inadmissibility and jurisdictional objection appeals within a sixty-day review period.Footnote 133 Implementing these reforms can streamline the appeals process, ensuring a fair, efficient, and expeditious resolution of international disputes.

2. Limiting the time of the arbitrator selection phase

The selection and challenge of arbitrators is a crucial aspect of time compression in arbitration. The disputing party places great importance on selecting arbitrators to ensure their position is favoured, resulting in significant time spent on this procedure. Party autonomy and institutional limitation can be further accelerated in the appellate mechanism. International arbitration has a significantly longer composition time than domestic courts, with an average duration of 220 days for tribunal composition, and this timeframe ranges from 91 days in the fastest cases to 546 days in the slowest scenarios.Footnote 134 The lengthy process of composing the arbitration tribunal is costly for disputing parties choosing arbitrators. While many view arbitrator selections as beneficial, some ICSID member states may prefer limiting this right. This consideration affects the appellate mechanism’s design, striving to balance disputing parties’ choice of arbitrators with efficiency. Importantly, maintaining the disputing party’s right to select an arbitrator does not imply an overly prolonged appointment procedure.

Article 2 of the ICSID arbitration rulesFootnote 135 outlines the tribunal composition. If parties cannot agree on arbitrator appointments, the suing party proposes names within ten days, and the respondent replies within twenty. If an arbitral tribunal is not established within sixty days, either party may request one under Article 37(2)(b) of the ICSID Convention, and the Secretary-General shall automatically agree. If an arbitral tribunal is not formed within ninety days, a party may request ICSID for arbitrator appointments in thirty days. However, in practice, arbitrator selection times exceed four months due to Article 3 lacking time constraints. The cancellation procedure exacerbates time issues, as the chairman appoints an Interim Committee faster than disputing parties nominate a tribunal.Footnote 136 While still longer than court or WTO processes, this streamlines the initial arbitrator appointment for disputing parties. A mandatory institution designation rule would replace the current optional procedure, curtailing cross-appointment time. Due to the limited scope, the time frame for cross-appointments is strictly set at twenty days, and for the selection of two arbitrators in the cross-appointment, it should not exceed ten days. Failure to reach an agreement within this time prompts direct appointment by the institution, preserving disputing parties’ autonomy but encouraging timely action, adhering to the principle of “use it or lose it”. The organization’s designated time should be further restricted to ten days.

Furthermore, the ICSID ConventionFootnote 137 allows parties to challenge arbitrators, halting proceedings until a decision on the arbitrator’s qualification is reached. This right is vital for investment arbitration, preserving fairness and legitimacy. Challenges must be raised promptly, preferably before proceedings conclude. The ICSID Arbitration Rules state that unchallenged members should proceed without the challenged arbitrator if they form a simple majority and within thirty days for cases of a challenged arbitrator before the pre-arbitration constitution.Footnote 138 For the above problem, a reform proposition suggests a thirty-day limit for filing challenges, aligning ICSID’s rules with international standards set by institutions like the International Criminal Court (ICC),Footnote 139 UNCITRAL,Footnote 140 International Centre for Dispute Resolution (ICDR),Footnote 141 Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre (HKIAC),Footnote 142 and China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (CIETAC),Footnote 143 allowing only fifteen to thirty days for similar challenges.Footnote 144 Professor Schreuer, in his comments on the ICSID Arbitration Rules, emphasized that Article 9, paragraph 1, requires the challenging party to raise a disqualification challenge as soon as it identifies a potential ground for disqualification.Footnote 145 Nevertheless, he deems this rule unreasonable and proposes its amendment within the appellate mechanism. To enhance transparency, the arbitration tribunal is required to furnish the list of its members and relevant personnel to the parties before the hearing. Additionally, before court proceedings, the arbitrator must inquire whether either party perceives any ineligibility or reason for avoidance. Failure to raise objections at this stage implies acceptance of the tribunal’s composition. Notably, the burden of providing conclusive evidence to establish the arbitrator’s ineligibility rests with the challenging party. This procedural refinement aligns with the overarching aim of ensuring fairness and clarity in the arbitration process.

3. Limiting the duration of formal arbitration proceedings

The process from tribunal constitution to award issuance is a critical juncture demanding enhanced efficiency in formal arbitration. Specific measures need to be adopted within the appellate mechanism to achieve this. First, instituting a mandatory initiation of proceedings within sixty days of an appellate tribunal’s formation can mitigate unnecessary delays caused by parties or the tribunal. This mandatory timeline ensures a swift commencement, eliminating deliberate postponements.

Second, addressing the time-consuming aspect of filing pleadings is crucial. Establishing fixed deadlines for written submissions, such as sixty days for memoranda and counter-memoranda, followed by a thirty-day response limit, accelerates the process. Notably, setting page limits on written submissions can further encourage focused and expeditious arguments, fostering a more streamlined process.Footnote 146

Third, improving the review standard for extension requests is crucial, with strict criteria for granting extensions and thorough scrutiny of extension reasons. The arbitration rules lack a specific review standard for extensions, allowing the tribunal discretion. To address this, the appellate mechanism should establish a clear extension standard with strict limitations on reasons for extension. Deferred hearings often arise from obstacles in the arbitration process, and a rigorous examination of the necessity for extensions is crucial to prevent delays.Footnote 147

Fourth, the American appeal court’s practice can be used to improve efficiency. The court allows three briefs: one each for the appellant and appellee and one reply brief for the appellant.Footnote 148 The appellant must submit a brief within forty days after filing the case, the appellee must submit a reply within thirty days, and the appellant should submit opinions within fourteen days of reply.Footnote 149 The overall procedure can be completed in at most eighty-four days. The briefs have a limit on word count, with the first two being 14,000 words and the last being 7,000 words.Footnote 150 Oral arguments are limited to twenty minutes; double that time is allowed in complex cases.Footnote 151 The ISDS appellate mechanism may need to be refined to avoid a lengthy first-instance appellate mechanism. For hearings, post-trial submissions can be limited to one round, allowing arbitrators to focus on award drafting.

Fifth, the ICSID Arbitration Rules do not limit the time to render the award. Article 36 stipulates that an award must be rendered within 120 days of the hearing, with a 60-day extension if it cannot be completed. However, this Rule does not require the tribunal to conclude the proceedings. The tribunal may wait until the award is written before closing the proceedings. Article 38(1) states that proceedings are closed when parties have completed their submissions, but the tribunal may reopen if new facts emerge. In 2012, the average time between the last hearing and award issuance was thirteen months, with the fastest being five and a half months and the slowest being thirty-two months.Footnote 152

Lastly, a clear timeline for award rendering is crucial, including the point of concluding proceedings and counting the writing period. A strict timeline, similar to the WTO Appellate Body’s sixty to ninety-day deadline for final decisions, and a limit not exceeding nine months from panel establishment to decision issuance would ensure expeditious resolutions.Footnote 153 Furthermore, transparency in award submission times can promote accountability, encourage timely completions, and facilitate informed decisions. This transparency benefits arbitrators and aids disputing parties in appointments and reappointments, enhancing the efficiency of the arbitration process.

F. Costs of the ISDS appellate mechanism

The financial implications of an appellate mechanism are a significant concern, often overlooked by tribunal composition and timeframes. The cost of an appeal is a more practical issue than the tribunal’s composition and the time frame. It is of immediate interest to the parties to consider using an appellate mechanism in the future. Opposition arises from concerns that it might disproportionately burden developing countries and specific dispute categories.Footnote 154 The focus should shift to the existing ISDS mechanism at ICSID, learning from precedents like CETA and TTIP to address this. As emphasized by Working Group III, addressing financial disparities is crucial to ensuring fairness and accessibility in a multilateral framework.Footnote 155 The Working Group III has proposed institutionalized financial relief measures aimed at reducing costs for small and medium-sized investors and developing countries, enabling them to participate effectively in appellate mechanisms without undue burden.Footnote 156 By defining clear procedural rules and transparently allocating costs, the financial aspect can be rationalized, ensuring equal treatment for investors and countries in economic distress.