LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this article you will be able to:

-

describe the key elements of dialogical practice

-

explain how a Mental Health Act assessment may incorporate some of these elements

-

describe how a dialogical approach to a Mental Health Act assessment ties in with some of the key recommendations for legal reform in England and Wales.

There is established and increasing support for the notion that attention to relationships, and the therapeutic alliance, are central to the practice of psychiatry. It is perhaps natural to expect this focus on the therapeutic alliance within the context of longer-term therapeutic mental healthcare, which may be characterised by psychotherapeutic and psychosocial approaches. However, the positive impact of stronger rapport on outcomes is also seen across different diagnostic pathways and at different levels of acuity (Martin Reference Martin, Garske and Davis2000). In line with this established evidence base, calls have been made for greater attentiveness to relationships in service design and operation at all levels, and for more focused training and support to be made available to staff to develop this as a central area of their practice (Priebe Reference Priebe and McCabe2008).

One area of psychiatric practice where there is great potential for the disruption of therapeutic relationships, and subsequent erosion of the potential for positive outcomes, is the use of compulsory detention and treatment under the Mental Health Act 1983 (MHA). There have been multiple problems identified with the way in which the MHA is applied in practice in England and Wales, and the 2018 Independent Review of the MHA (Department of Health and Social Care 2018) sought to understand these in more detail, with a particular focus on:

-

rising rates of detention under the Act

-

the disproportionate number of people from Black and minority ethnic groups detained under the Act

-

processes that are out of step with a modern mental healthcare system.

Towards better practice?

One such process out of step with a modern and progressive mental healthcare system is that which oversees the formal detention of people under sections of the MHA: the MHA assessment. We believe that a modern and progressive mental healthcare system is one that prioritises the fundamental human rights and dignity of those who receive its services, through strongly embedding the five overarching principles of the MHA Code of Practice for England (Box 1) across all levels (a separate Code applies in Wales). In our experience, the way in which MHA assessments are set up and conducted very often makes it difficult to properly promote ‘empowerment and involvement’, the ‘least restrictive option’ and, sadly, sometimes even ‘respect and dignity’. It is also important to note here, for clarification, that there is no statutory definition of what constitutes an MHA assessment. The work of Simpson et al (Reference Simpson, Lewis and Mitchell2024) is of growing influence in orienting the approved mental health professional (AMHP) community towards the variety of creative and often less-restrictive ways in which AMHPs can respond to referrals into their services. After all, their primary duty is to ‘consider the patient’s case’ on behalf of the local authority (MHA, section 13(1)) and there may be very legitimate reasons for not involving medical practitioners as part of this work (section 13(1)). However, for the purposes of detention under the Act, an MHA assessment must include a medical examination by one, or more likely two, registered medical practitioners, one of whom must be approved under the provisions of section 12 of the MHA, demonstrating ‘special experience in the diagnosis or treatment of mental disorder’ (section 12(2)). The AMHP is tasked with interviewing the patient ‘in a suitable manner’ (Department of Health 2015: statute 13(2)), before making an application for admission under the Act. In practice, these two aspects of an MHA assessment, the ‘medical examination’ and the ‘AMHP interview’, are usually conducted together, and indeed the Code of Practice states that ‘Unless there is good reason for undertaking separate assessments, patients should, where possible, be seen jointly by the AMHP and at least one of the two doctors involved in the assessment’ (para 14.45). It is this joint endeavour that is the subject of this article.

BOX 1 The five guiding principles when applying the Mental Health Act 1983

All decisions in relation to care, support or treatment provided under the Act should be considered in the light of:

-

the least restrictive option and maximising independence

-

empowerment and involvement

-

respect and dignity

-

purpose and effectiveness

-

efficiency and equity.

(Adapted from Department of Health 2015: p. 22)

The patient’s experience of MHA assessments

In 2018, some months before the Independent Review was published, the AMHP service covering the county of Devon (in south-west England) had already begun to turn its attention to notions of good and poor practice in MHA assessments, encouraged do so in a series of workshops entitled ‘Conversations across the Divide’, co-produced with local experts by experience group The Bridge Collective. The aim of these sessions was to create dialogue and shared understanding regarding our different experiences of receiving and undertaking MHA work. It quickly became apparent, through moving testimonies of what it was like to be subject to an MHA assessment, that this was an area of crisis care work in need of reimagining. A light was shone on practices such as excluding the person of concern from the discussion between professionals at the end of the interview process, practices that had hitherto been unquestioned. Therefore, it did not come as a surprise when the Independent Review reported later that year that:

‘One of the recurring messages from our extensive engagement with service users is that the process of being detained under the Act is too often experienced as awful. Just as truth is often described as the first casualty of war, the same is true of dignity when compulsive powers are being invoked. The person affected, the service user, stands to lose authority over him or herself, loses self-determination and as a result, quite apart from other features of the system, can be stripped of their dignity and self-respect’ (Department of Health and Social Care 2018: p. 17; emphasis in original).

This makes for very uncomfortable reading for the AMHPs and medical professionals involved in this work, demonstrating the harsh reality that a person’s liberty is often not the only precious good removed from them by an MHA assessment – their dignity can be taken away too. A recent piece of co-produced research has helped us to understand what might be happening in these assessments, by exploring the experiences of ten people who had received an MHA assessment in the previous 6 months (Blakley Reference Blakley, Asher and Etherington2021). The key themes were that the assessments are often rushed and clinical encounters; that there may be a lack of transparency or even a veil of secrecy with respect to what the assessment is for; and a fundamental sense of not having one’s own narrative listened to, validated and understood. For the clinicians involved and subsequently for those being interviewed or examined it can, simultaneously, feel like a very formal process, driven by the objective of determining whether the statutory criteria for detention are met and, if so, whether an application for detention should be made (Department of Health 2015, para. 14.33). Again, this may contribute to the experience the person and their family have of not having their perspective acknowledged and responded to.

Similarly, an anonymously authored article in the BMJ described how the experience of detention under the MHA had lasting impacts on the loss of trust in healthcare services and an anxiety about seeking help of any form in the future. This effect occurred in part because professionals involved were not transparent or honest about the process or their rationale for the decision. The author encourages those involved in MHA assessments to consider the gravity and impact of a decision to remove someone’s liberty and appeals to the need to inform the person of concern as to why they are taking that step. Furthermore, they ask that care be given to maintaining and rebuilding trust, so that access to healthcare is possible in future for people who have experienced detention (Anonymous 2017).

Some of the ways in which we may restore and maintain trust in MHA processes were pinpointed in a 2019 systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis looking at the experience of assessment and detention under the MHA (Akther Reference Akther, Molyneaux and Stuart2019). Better experiences were characterised by the quality of information provided to the person, the extent to which they were supported to be involved in decision-making about their care, and the quality of relationships with staff. Here, the involvement of people’s families supported a continuing sense of who that person was, as well as feeling listened to, understood and believed. Other important factors reported as contributing to a better experience were staff not reducing patients to a diagnosis and their use of a more trauma-informed perspective.

Introducing dialogical and relational practice into the assessment process

Given the consistency of the message across all these accounts and the gravity of the impacts described, we believed that it would be fruitful to consider how the quality of attention given to relationships and relational aspects influences the process of the MHA assessment. This may be done with particular regard to the experience for people of concern, their families and carers, and the quality of the information gathered informing the decision-making process. A reorientation towards dialogical and relational practice in MHA assessments certainly has strong salience with the recommendations of the Independent Review, which identified ‘epistemic injustice’ at multiple levels in the way in which decisions about care and treatment under the MHA are arrived at and then delivered (Department of Health and Social Care 2018). In addition to these developments, we are already guided by the aforementioned five overarching guiding principles in the MHA Code of Practice (Box 1), which speak to the vital need to listen to patients and their families and to fully involve them in decision-making.

Running concurrently with the above co-produced initiative within the Devon AMHP Service, work has been taking place in Devon Partnership Trust with involvement in the ODDESSI trial in Torbay since 2018 (Pilling Reference Pilling, Clarke and Parker2022). ODDESSI aims to examine Peer-supported Open Dialogue (POD) as a way of organising and delivering a socially networked care planning approach in adult mental healthcare. The rich learning from the ‘Conversations across the Divide’ sessions pointed very much towards AMHPs and doctors finding ways to prioritise open, participatory, transparent and jargon-free conversations with the person and their social network, and this is exactly what POD is designed to do. Curiosity then emerged about the potential for joint AMHP and doctor MHA assessments to use elements of dialogical practice and for the development of more specific practice guidance about how the AMHPs and doctors could conduct the assessment (Manchester Reference Manchester2022).

This is not to deny or discount the useful direction for AMHPs in the MHA Code of Practice about what is meant by the section 13(2) instruction to ‘interview in a suitable manner’, which focuses AMHPs’ minds on the importance of establishing whether patients have particular communication needs or difficulties and then taking steps to meet these, for example by arranging a signer or a professional interpreter (Department of Health 2015: para. 14.42). Transparent explanations about professional roles and the purpose of the meeting at the start of the assessment (para. 14.51) and securing the presence of people significant to the patient if the patient wishes (para. 14.53) must also feature in an AMHP’s approach to their interview. Likewise, we know it is mandatory for the medical examination to involve ‘direct personal examination of the patient and their mental state, and consideration of all available relevant clinical information, including that in possession of others, professional or non-professional’ (para. 14.71). The notion of examining a patient in person was further delineated by the case law ruling Devon Partnership NHS Trust v SSHSC [2021], in which it was determined that remote assessments were unlawful. This was, in part, because parliament understood the medical examination as necessarily involving physical presence, not least because psychiatric assessment may involve the reading of body language and a discernment of a range of non-verbal and multi-sensorial cues. In this respect, existing mental health law sets the parameters and restrictions on the manner in which AMHPs and medical practitioners carry out their assessments, creating an important safeguard for the patient’s liberty. We sought to drill down further, beyond the broad parameters of the legal guidance, to explore how dialogical skills and principles can improve clinical practice in this area.

Establishing key elements

We drew on the 12 key elements of fidelity to dialogical practice described by Olson et al (Reference Olson, Seikkula and Ziedonis2014) and outlined Box 2: a number of these are transferrable to the setting of the MHA assessment, not least because good communication and a social network approach are considered priorities in the MHA Code of Practice. Our identification and translation of key dialogical skills happened as a progressive process of trial and error initially. Using our experience of Peer-supported Open Dialogue, we attempted to integrate elements into our MHA practice, reflecting on the success or otherwise of the approach with other members of the assessing team, and at times the people and their networks being interviewed and examined. The process produced seven elements (listed in Box 3 and discussed below) that are either identical to a key fidelity element in Box 2 or a composite of several of them. Three of the 12 key fidelity elements are neglected (1 – two or more therapists in the meeting; 5 – emphasising the present moment; and 8 – responding to problem discourse in a matter-of-fact style) because of the contextual differences between an Open Dialogue network meeting and an MHA assessment.

BOX 2 The 12 key elements of fidelity to dialogical practice in Open Dialogue

-

1 Two (or more) therapists in the team meeting

-

2 Participation of the person’s family and/or network

-

3 Use of open-ended questions

-

4 Responding to the person’s verbal and non-verbal utterances (including silences)

-

5 Emphasising the present moment

-

6 Eliciting multiple viewpoints (polyphony)

-

7 Using a relational focus in the dialogue

-

8 Responding to problem discourse or behaviour in a matter-of-fact (‘normalising’) style that is attentive to meaning

-

9 Emphasising the person’s own words and stories, not symptoms

-

10 Conversation among professionals in the treatment meetings (the reflecting process, making treatment decisions, and asking for feedback)

-

11 Being transparent

-

12 Tolerating uncertainty

(Adapted from Olson et al, Reference Olson, Seikkula and Ziedonis2014, and used with permission of Professor Jaakko Seikkula)

The seven elements that we identified are aspirational at this stage, and we stress that we do not wish to communicate a sense that an interview is either ‘dialogical or monological’, ‘good or bad’. Efforts to communicate dialogically and to support the development of an understanding of what the person feels, why they feel as they do and how this then informs a plan for care can often feel faltering and have to be highly flexible to the circumstances that the interaction takes place in. This can be especially true in the stressful environments and circumstances in which MHA assessments often take place, with people who may be acutely distressed and/or mentally disordered and with assessors who are often not clinically or therapeutically involved in that person’s care. There is an argument that an MHA assessment is not, and was never intended to be, a therapeutic intervention, although we believe every human interaction has potential to be therapeutic or traumatic. We acknowledge that there are unignorable responsibilities placed on the assessing team and the aim of the dialogical approach is not to alter the outcome of the assessment. Instead, it is about giving care, attention and skill back to the process itself, underpinned by a belief that an MHA assessment is an intervention in itself because it represents an opportunity, at a critical time, to really hear, understand and respond to a person in crisis and their network. This is particularly important for those people and communities who are most at risk of coercion and control within the psychiatric system, including some racialised communities.

The seven elements that may be transferable and useful in most circumstances are as follows.

1 Taking a social network perspective (drawn from key fidelity element 2)

It is important that the AMHP takes a social network perspective when meeting the person in advance as well as during the joint assessment itself. When meeting with the person in advance without the medical assessors (as directed by para. 14.54 of the MHA Code of Practice; Department of Health 2015) the AMHP may consider not only whether the person being assessed is aware of the process to be conducted, but also whether there is anyone else who cares or could help who may be useful to include in the interview in some way (para. 14.53) (if not addressed in the advance meeting these points must be considered at the start of the assessment itself). Can the AMHP contact them and enable them to be present in person, on the telephone or via video call? During the assessment conversation, heed can be paid to the voices of people who may not be physically present by asking about them. What would they have said in response to that? What would they have liked to have said if they were here? Mobilising resources in this way can be important for understanding and managing risk, with information being drawn from multiple viewpoints and engaging those people around the person in developing the plan and seeing it through. This applies equally to the medical examination as it does the AMHP interview, given that we know that the examination must involve a consideration of relevant non-professional information (para. 14.71).

The assessment conducted using a social network perspective reflects the potential that all members of a chosen network may have to contribute meaningfully to care planning. We can all be experts in some areas some of the time. A key idea in Open Dialogue is that the person of concern and their network know best about a number of things useful to assessment and care planning: for instance, what has led to the current crisis, what would need to happen for the crisis to resolve and how the network itself can contribute to the resolution. In addition, because the ‘social graces’ (Burnham Reference Burnham and Krause2012) of the assessors are potentially different from those of the person being examined and interviewed, the person of concern and their network are of paramount importance to informing clinicians about social and cultural aspects which they are unaware of. This explains why this approach might be useful in reducing epistemic injustice and enhancing good practice with people from diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds, including members of racialised communities, who are experts in their own cultural background.

For people involved in supporting someone in the process of assessment the sense of being included and feeling that their voices are sought and heard can be very important. In our experience, it is not an uncommon theme of complaints raised by carers and families that they did not get a chance to express their views and were marginalised or disregarded in the process of the assessment and care provided to their loved one. For the assessors, the reliability of referenced accounts and information, and increased validity achieved by having multiple reference points in relation to often critical and significant events precipitating these assessments, is highly valuable. One of the six key clinical messages delivered by the National Confidental Enquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health (NCISH) was that:

‘Families and carers should have as much involvement as possible in the assessment process, including the opportunity to express their views on potential risk. The management plan should be collaboratively developed where possible’ (NCISH 2018).

It is worth remembering here that AMHPs are well placed to work in this systemic way, guided as they are by the MHA and the Code of Practice to work proactively with a person’s social network, including statutory responsibilities towards informing and consulting with nearest relatives.

2 Enabling as a many voices as possible to be heard (polyphony) (drawn from key fidelity element 6)

A little preparation in what may be a group of people unfamiliar with working closely together who, because of their roles, may be independent in their decision-making can be helpful. In our practice in Devon it is becoming increasingly common to discuss with colleagues in an assessing team prior to the interview whether they would like to conduct the MHA assessment dialogically. This does seem to help assessors cooperate more successfully with the approach and elicit as many voices as possible, both from those being examined and interviewed and from the assessing team, in a coordinated and mutually supportive manner. It may be helpful to consider who may lead the interaction initially, how turns may be taken, and what availability and competing pressures on time team members have. It has been our experience that when only one or two of the assessing team are familiar with dialogical practice, they offer to take a lead with the approach initially. It is also common in such circumstances to brief those new to the approach that we may, if we all feel comfortable doing so, discuss the outcome of the assessment and our recommendations in the presence of the person concerned, giving them an opportunity to respond.

3 Being transparent from the start (drawn from key fidelity element 11)

Being transparent with the person and their network at the start of the interview about what the assessors have read, why they have been called and what their roles are can be a helpful way to start the assessment. It is important to invite the person of concern and their chosen network to respond to the summary and rationale for the assessment. There is an opportunity to acknowledge the power imbalance present within the assessment structure and the roles of those present by making it clear from the very beginning what the overall purpose of the meeting is, including the potential for the AMHP to make an application for admission should they be furnished with valid recommendations from the medical assessors. Although power cannot be evenly distributed in this context, acknowledging the imbalance is a way of giving name to a feature of the transaction that in our experience appears to have a strong influence on how people choose to engage, and allow themselves to be engaged. By doing this we are permitting people to talk about what it feels like in the present moment, what it is like to be interviewed by two doctors and another professional with the power to take away their liberty. This dynamic and potentially threatening experience may actually be the most powerful part of their experience at that time, whatever has preceded the interview, and so may need to be expressed for them to be present and heard in this context.

Setting the scene in such a way can be helpful in reducing people’s anxiety as well as clarifying key components of the timeline leading to the assessment. It is not uncommon in our experience to have had multiple agencies involved with a person, and for their observations and concerns to motivate the assessment. As is also possible in such circumstances, information may become de-contextualised or distorted or may even be inaccurate. Giving people the opportunity to understand how and why the assessment has been called, and to question, correct or challenge the understanding the assessing team have, can be very helpful in generating more accurate, and therefore safe and effective, overall assessment by drawing on as many sources of reference as possible.

4 Using relational questions during the interview (drawn from key fidelity element 7)

These are questions arising from the development of systemic practice in health and social care and they focus on understanding the ‘gap’ between things or points in time. Asking relational questions is an approach that seeks to explore how an idea, object, event or experience is regarded in separate people, times or places. Examples include: ‘What would your mum/sister/daughter/partner/… say to this if they were here now? ‘What has your friend said about that/what happened then, and what do they say now?’

Relational questioning can support the development of insight for everyone into the meaning of behaviour and events, again addressing epistemic injustice. People can have the opportunity to hear how specific behaviours, events or objects have meanings that can be different for different people and at different times. This in turn can support understandings of others’ beliefs and behaviour, how we have come to find ourselves here and now, and what responses and resources may be helpfully brought to alleviate the situation.

5 Encouraging the person of concern to describe and discuss what they feel are important events, experiences, understandings, needs and concerns (drawn from key fidelity elements 3, 4 and 9)

BOX 3 Seven key elements of a dialogical approach to the Mental Health Act (MHA) assessment

-

1 Taking a social network perspective

-

2 Enabling as a many voices as possible to be heard (polyphony)

-

3 Being transparent from the start

-

4 Using relational questions during the interview

-

5 Encouraging the person of concern to use the MHA interview to describe and discuss what they feel are important events, experiences, understandings, needs and concerns

-

6 Tolerating uncertainty

-

7 Concluding the assessment meeting with full transparency where possible

This should be facilitated for as much of the interview as possible, and at least in the early part, by using a combination of the following tactics.

-

Ask open-ended questions: After the assessors have set the scene with the information and events that led to the assessment being called, and the person and their chosen network have responded to this introduction, an assessor might ask something like ‘Can you tell us how and why you think we came to be having this meeting today?’ This allows the person to start from where they are and welcomes their perspective as an equal voice alongside those of the assessors.

-

Repeat a word or words that have struck you or feel central to someone’s account. This sends a strong signal that you are listening and encourages them to say more, should they wish to. This does not direct the dialogue and so does not assert the power of the interviewers and examiners to define the topics covered themselves, as an open-ended question might. It also is not a process of summarising and demonstrating that you have understood what someone is saying – this may come later, druing the reflection when better context to the understanding can be given.

-

Utilise silences: try not to step in too soon when silences occur. Instead, use them as a means to prompt the person to say more. It can be uncomfortable, but it is important not to rush. Having a conversation about this part of the approach with other members of the assessing team in advance may be important, to enable this aspect to be more reliably achieved.

-

Avoid jumping in with technical talk about symptoms and diagnostic labels, or with judgements, ideas or solutions early on. Doing so can further compound the power imbalance. Inevitably, an MHA interview has to arrive at an outcome later, but as the conversation unfolds, tolerate some uncertainty and respond instead by showing genuine interest in the person’s story and their words and in learning more from them.

6 Tolerating uncertainty (drawn from key fidelity element 12)

It is important to tolerate uncertainty, which can in turn lead to the adoption of a ‘not-knowing’ stance. In our (T.C.’s) experience of medical examinations, it is possible at times to find oneself thinking in advance that the pending assessment will be likely to follow a particular line. Perhaps this is based on previous history, diagnosis, setting and the reported rationale for the assessment, from which certain assumptions may arise. Remaining as aware as possible of potential assumptions, bias and sources of uncertainty is something those approved under the MHA try to do. By just noticing this thought process, and not necessarily trying to remove it, we enable recognition of the extent to which we can be drawn to a desire to exclude uncertainty and to avoid a sense of not knowing how things will be before we engage with them. By trying to spot things we did not know or expect we can generate more of an awareness of our ‘unknowingness’, thereby improving our ability to really hear and explore what is being said.

7 Concluding the meeting with full transparency where possible (drawn from key fidelity elements 10 and 11)

Where possible, conclude the assessment meeting with full transparency, using reflective practices in the decision-making discussion in the presence of the person of concern and their network and then inviting them to respond should they wish. This ensures that the person of concern and their network are included in the process of planning an outcome from the assessment.

The following steps should structure the concluding process.

-

1 Inform the person and their network that you are about to discuss what you have heard. Ask them to listen for the time being, but say that you will return to them once the discussion has concluded and would like to hear any responses they have at that point.

During the discussion, look at your colleagues in the assessing team, not at the person of concern or their network.

-

2 Try to make some positive or grateful comment about everyone in the room who has contributed to the assessment and try to use their names not roles; mention what struck you and why about what was said in the room, and how this may influence your decision-making and opinion. You can share what feelings you may have noticed inside yourself, for example a sense of sadness, or feelings of anxiety or worry, or hope. These feelings may be linked to the opinion as to whether detention is proportionate and appropriate and why, including honest reflections about risk.

-

3 Ask the person and their network whether they have any feedback about the discussion. This may lead to a return to a discussion between the assessors and the person of concern focusing on clarifying components of the assessment. Should this happen then returning to step 1 above may be appropriate.

Conclusion

The MHA interview and examination represent a very significant assessment and decision-making forum in mental health crisis care, and one that has received little in the way of attention in practice, training or research. This is despite the fact that tens of thousands of these interviews take place nationally every year, in which decisions are being made to subject ever-increasing numbers of people to compulsion, disproportionately affecting some racialised communities. In England and Wales during 2023–2024, an incomplete data-set showed that there were 52 458 new detentions (an estimated 2.5% rise on the year before), the vast majority of which were new admissions under section 2 or 3 of the MHA following assessment by an AMHP and two doctors (NHS England 2024). There are also a large number of assessments whose outcome is informal admission or community care, not captured in the data. Emerging evidence strongly suggests that experiences of being subject to MHA assessments are too often very poor – they can be rushed affairs, lacking both transparency and a genuine interest in the person and their own narrative, prioritising instead expediency in identifying clinical and risk factors. Applying dialogical practice skills and principles can, in our experience, change this for the better.

Currently, a dialogical approach to the MHA interview is undergoing development and refinement in AMHP services in Devon, Dorset, Gloucestershire and London, among other local authority areas, and there is an open national quarterly network meeting for dialogical and relational MHA practice attended by medical professionals, AMHPs, people with experience of receiving secondary mental health care and other interested parties, which is chaired by R.M. A number of local authorities have commissioned training on these ideas for their AMHP services, and there is a growing recognition that future training initiatives need to aspire to bring AMHPs and section 12 approved doctors together. This step could generate more shared understanding of why MHA work requires our attention and what skills and attitudes are needed to improve practice. Access to good-quality training will be hugely important for both AMHPs and doctors to be equipped with the skills and confidence to embed this approach in their work in a consistent way, with cooperation across professional disciplines being imperative.

However, as with any innovation requiring some investment of time and financial resources in the training and development of staff, perhaps what is more important in terms of next steps is to formally evaluate the impact in MHA assessments of the seven dialogical elements presented in this article, taking into account professional, patient and carer experiences, as well as outcomes, so that there is an evidence-base to draw on and an even greater standardisation of the methodology underpinning this model. Experience thus far is that although the approach remains an aspiration, and one that is variably achieved, the key elements are applicable in many more assessments than not. We (T.C. and R.M.) have undertaken numerous MHA assessments using this methodology, sometimes together, and on occasion there has been very positive feedback from people being assessed, thanking the assessing team for their assessment, despite not welcoming the outcome. It has been the experience of senior clinicians that the longer-term relationships with people and their families can benefit from taking this approach. This may, in turn, lay foundations for improved outcomes in the longer term.

The dialogical or relational approach to MHA work may not always be possible in its entirety and neither is it geared towards reducing the likelihood of people being detained (although a social network model of care will naturally open up more possibilities in crises). What it is first and foremost is a practical way of improving the experiences of people using psychiatric services and their carers by improving the inclusion and participation of those people and their families and wider relationships involved in the assessment. This is not only in line with what people and their families want and need from professionals when in crisis, it is also in line with the central recommendations of legal reform. Fundamentally, it represents a vital attempt to humanise the process and reduce the veil of secrecy that serves only to sharpen the already steep power gradients in these assessments.

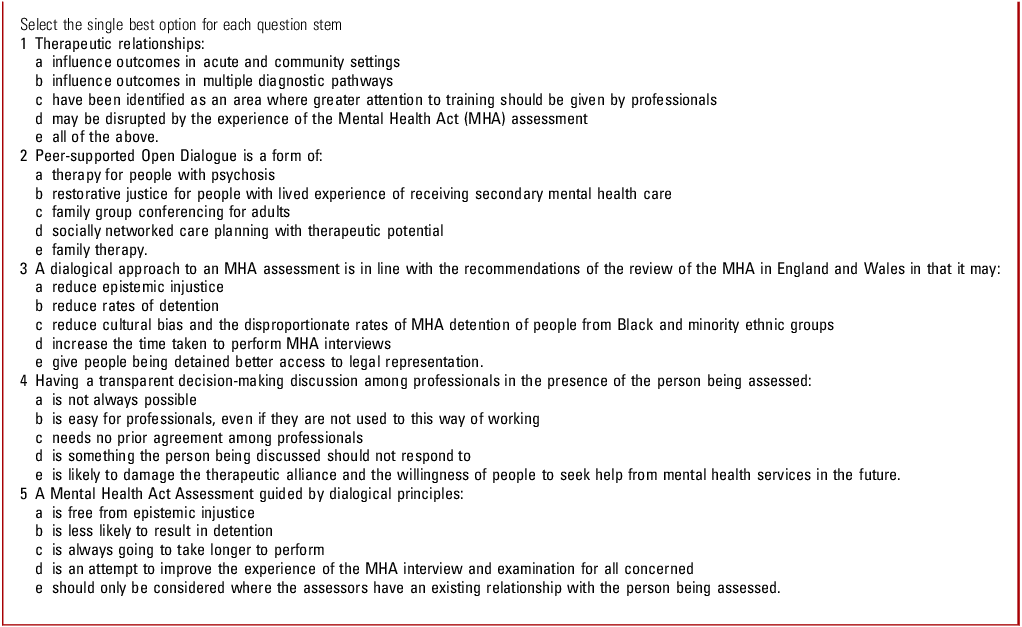

MCQs

MCQ answers

-

1 e

-

2 d

-

3 a

-

4 a

-

5 d

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this work.

Acknowledgements

Professor Russell Razzaque, Tracy Lang and Yasmin Ishaq kindly participated in technical editing of the manuscript.

Author contributions

T.C. and R.M. have contributed equally to the development of practice principles outlined in this article, as well as the processes of manuscript drafting and submission.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.