Comprehend, Cope and Connect (CCC) is an evidence-based, trauma-informed, transdiagnostic and cross-cultural psychological intervention designed to meet the needs of individuals in in-patient and other mental health settings, which has been extensively piloted in the South of England. Reference Clarke1,Reference Clarke and Nicholls2 CCC starts with a formulation: a way of making sense of mental health breakdown that encapsulates the individual’s circumstances, strengths and the unique maintaining factors for a mental health crisis in simple terms – and leads to new ways of coping for the individual. This formulation is either worked out collaboratively with the individual (co-produced) or provides a framework for a team to think together and make sense of the crisis. Where the formulation is co-produced, it is understood and owned by the individual but supported by the whole service. If it is a team formulation, it can inform the treatment plan for the service.

Growing evidence from empirical research, primarily conducted in the South of England, indicates that a CCC approach should be implemented more widely in acute psychiatric services across the UK. Reference Riches, Araci, Csehi, Saidel, Gatherer and Pierce3–Reference Durrant, Clarke, Tolland and Wilson12 Therefore, the aim of this article is to emphasise the benefits of implementing the CCC approach more widely across the country. Indeed, patients and mental health professionals have highlighted the need for more psychological interventions in acute and crisis mental health services, Reference Small, Pistrang, Huddy and Williams13 which is further outlined by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 14,15 and in the NHS Long-Term Plan. 16

Comprehend, Cope and Connect – a national approach to a national problem

Mental health crises are a significant problem for individuals, families and services across society. This is indicated through the subjective impact of crises (e.g. reduced quality of life, increased carer burden, reduced staff compassion and staff burnout), Reference Tane, Fletcher and Bensa17–Reference Basu20 clinical and risk outcomes (e.g. increase in symptoms of mental illness, risk to self and risk to others) Reference Penterman and Nijman21,Reference Bowers, Banda and Nijman22 and economic impact (e.g. cost of service provision, loss of productivity). Reference Knapp and Wong23 Unfortunately, this national problem is being steadily exacerbated by ongoing societal stressors, such as the UK cost-of-living crisis Reference Lawson, Haggar, Hewlett, Hall, Piggott and Hesketh24 and the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic. Reference Anaya, Howley, Waqas and Yalonetzky25 These pressures have a disproportionate impact on people from marginalised groups who are experiencing additional stressors such as racism, Reference Paradies, Ben, Denson, Elias, Priest and Pieterse26 homophobia, Reference Ventriglio, Castaldelli-Maia, Torales, De Berardis and Bhugra27 transphobia Reference Price, Hollinsaid, McKetta, Mellen and Rakhilin28 and multiple exclusion homelessness. Reference Pattison and McCarthy29 In response to these pressures, there are calls for the enhancement of current approaches. Reference Huber, Milton, Brewer, Norrie, Hartog and Glozier30–Reference Correll32

Development of the CCC approach

The second author (I.C.) took the opportunity, as lead psychologist in a then-new National Health Service (NHS) acute in-patient unit, to develop and pilot the CCC approach Reference Clarke1,Reference Clarke and Nicholls2 between 2004 and 2012 to meet precisely these challenges. Reference Clarke and Wilson11,Reference Durrant, Clarke, Tolland and Wilson12 The consequent publications and recognised success of this initiative led to its extension across four acute services in a large NHS trust Reference Araci and Clarke9 and its subsequent embedding in acute and other services in ten other NHS trusts, predominantly in the South of England. Reference Bullock, Whiteley, Moakes, Clarke and Riches8,Reference Paterson, Karatzias, Dickson, Harper, Dougall and Hutton33 The approach itself has remained largely as originally developed, with the important addition to the formulation diagram of a prominent role for strength and spiritual connection, which arose from cross-cultural collaboration. Reference Phiri, Clarke, Baxter, Yutain, Shi and Yuan6 Evidence indicates that this trauma-informed and person-centred approach may be the next step in solving the problem of mental health crisis.

Understanding crisis the CCC way

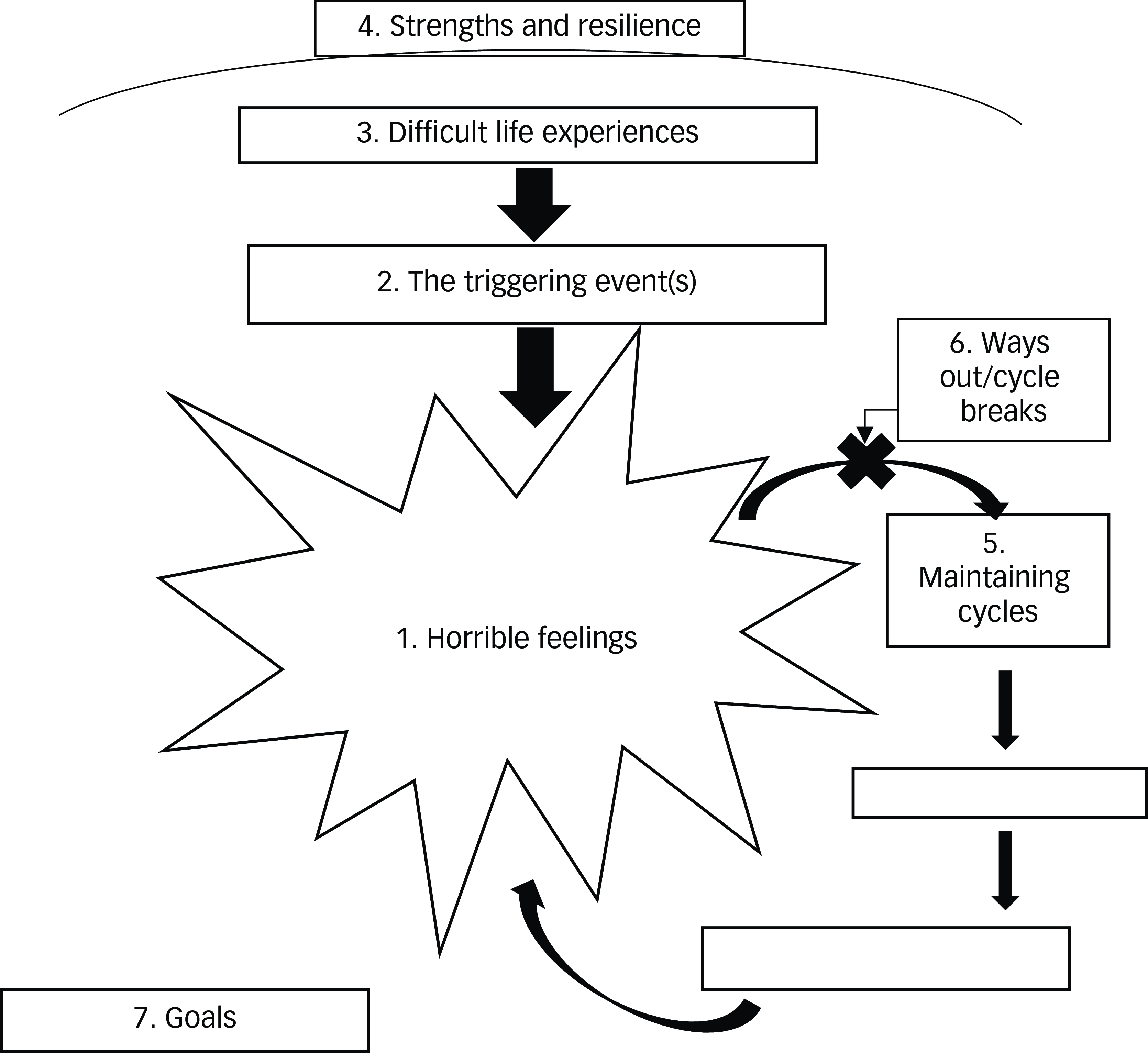

Within the CCC framework, mental health crisis is seen as arising when current stressors, combined with past trauma, lead to the individual’s coping resources becoming overwhelmed. A simple explanation for this interaction is informed by the organisation of human neural circuitry, as delineated in the interacting cognitive subsystems (ICS) model of cognitive architecture. Reference Clarke34,Reference Teasdale and Barnard35 The CCC formulation (Fig. 1) illustrates how current attempts at coping with this interaction (e.g. substance use, dissociation) are understandable yet perpetuate the crisis.

Fig. 1 Template for the ‘Comprehend, Cope and Connect’ formulation.

As shown in Fig. 1, the CCC formulation understands the crisis state of ‘horrible feelings’ (1) as brought on by a precipitating event (2) that triggers previous trauma (3). CCC prioritises strengths to increase motivation (4) and draws on these to change the unhelpful coping that maintains the crisis state (5), leading naturally to the identification of alternative coping (6). These changes are used to identify behavioural goals that can be owned by the individual, incorporated into the multidisciplinary team care plan and then supported by the entire staff group, along with family, carers and community supporters (7). Both the necessary behaviour change and the rationale for it can be made clear and evident to all. Training, reflective practice, case discussion and co-working ensure that the individual (or team) trauma-informed formulation is linked to the practice of the entire service, thus promoting a psychologically informed approach and circumventing the disconnect that can exist between therapeutic services and the rest of an organisation. All admissions to acute care can be viewed by the team through the CCC lens, but co-produced individual formulations will be suitable for those who are able to engage and where resources enable this. CCC has been shown to complement the routine responsibilities of psychiatric wards, ensuring safety and effective pharmacological interventions through strengthening engagement between the individual and the team, thus enhancing treatment adherence.

Furthermore, CCC influences the whole milieu by linking an individually tailored approach to communication across the service, with interventions to break perpetuating cycles (such as arousal management, self-compassion) deliverable by all mental health staff after brief training and with ongoing supervision. It further disseminates a compassionate and psychological understanding of crisis. In our clinical opinion, it involves the wider staff group, develops their skills, increases job satisfaction, mitigates against risk of compassion fatigue and supports staff retention.

Evidence for the approach

Since its initial pilot, Reference Durrant, Clarke, Tolland and Wilson12 CCC has been introduced into numerous acute services, developed for other services (e.g. community mental health teams, psychotherapy services) and introduced into some primary care networks. The ten acute NHS mental health trusts that have received training and embedded the approach have opted to join the new CCC Research Network, a commitment that further evidences the utility of CCC and the feasibility of embedding it in routine services. Importantly, CCC is empirically supported by a continuously growing evidence base. With a large sample of 131 patients in Hampshire, Araci & Clarke Reference Araci and Clarke9 provided quantitative evidence of both efficacy, with pre- and post- measures showing improvement, and feasibility, with delivery of CCC interventions by staff from both psychological and non-psychological professions. Expanding on this, Riches et al Reference Riches, Araci, Csehi, Saidel, Gatherer and Pierce3 provided evidence of its impact on and acceptability to acute and crisis staff. In Bristol, Wasiewska et al Reference Wasiewska, Wilkinson-Tough, Stephens and Abdi4 provided evidence that when CCC is utilised as a team formulation model in an in-patient setting, it has a positive effect on staff perceptions of patients, subsequent care provided, staff confidence and motivation. In addition, a feasibility study in Lothian, Reference Paterson, Karatzias, Dickson, Harper, Dougall and Hutton33 conducted before the label CCC had been adopted, of 96 patients in in-patient settings showed promising results and also highlighted factors that would be important to consider when implementing and evaluating a whole-service approach. The South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust has produced the rest of the formal evidence to date: Bullock et al Reference Bullock, Whiteley, Moakes, Clarke and Riches8 reported that CCC resulted in significant improvements in mood and goal-related outcomes in patients, and was both acceptable and feasible to deliver; Riches et al Reference Riches, Csehi, Steer, Azevedo, Vasile and Lokhande36 reported that CCC is feasible and acceptable to deliver to patients as a remote video call-based therapy, with positive quantitative and qualitative outcomes; and qualitative research undertaken by Harris et al Reference Harris, Clarke and Riches5 found that CCC is viewed favourably by patients, carers and multidisciplinary staff. More data is being collected in other services across the UK, and in Pakistan, and with the recent organisation of the CCC Research Network, future research will provide further evidence of the impact CCC is currently having in routine practice. In particular, Harris et al Reference Harris, Clarke and Riches5 brought patient and carer voices into the foreground: both patients and carers perceived the CCC model as seeing the whole person, beyond labels, while bringing clarity to crisis and highlighting the important role of emotion. Additionally, patients and carers highlighted what they believed to be important for staff being trained in the CCC approach, emphasising that compassion, empathy and a need to understand the patient experience are priority.

A parallel development has applied CCC to the challenge of complexity in NHS psychotherapy services, and a pilot project has evaluated its application to therapy for people from non-Western cultures in Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust. Reference Phiri, Clarke, Baxter, Yutain, Shi and Yuan6 CCC was found to be suitable for such adaptation, being less individualistic than much Western therapy, facilitating involvement of family and community, and incorporating faith and spirituality.

This research indicates that CCC warrants further piloting and clinical research across the UK because of its ability to embed routine holistic, trauma-informed practice into acute settings, to engage individuals as partners in their own recovery and to create clear routes to that recovery that can be communicated across the care pathway. It demystifies the psychological approach by breaking down interventions into straightforward packages that can be delivered by a wider spectrum of staff, thus increasing their availability in a context of restricted psychology resources. Indeed, staff have expressed that, with the right support, they would feel confident to deliver CCC interventions and integrate these into standard care planning procedures. Reference Harris, Clarke and Riches5 Members of the CCC Research Network are involved in further grass roots research and evaluation projects, with further inclusion of the patient and carer perspective, which is needed to be brought into the CCC literature more deeply.

CCC across the UK

In line with this, CCC has already successfully been taken up by many different services across the UK. Services in the South East, South West, East and North West of England, and services in Ireland, are all supporting patients and staff teams the ‘Comprehend, Cope and Connect’ way. The following accounts were contributed by members of the CCC Research Network, set up by the first (J.H.) and last (S.R.) authors in 2023, and which now has over 70 members.

South East England

Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust has embedded CCC throughout its care pathways to operationalise the trust’s strategic objective for trauma-informed working. Here, CCC is the foundation for the overarching trauma-informed approach. For instance, in Southampton’s Acute and Crisis Mental Health Pathway, CCC is the model used for psychological formulations, therapy groups and brief interventions. With nursing and senior management, a new care plan has been developed that incorporates CCC, offering collaborative conversations about distress, risk and safety. This is being piloted in a psychiatric intensive care unit (PICU), with good initial outcomes; individuals report feeling more heard, understood and supported. The Isle of Wight NHS Trust has also implemented CCC across its acute and community services. Formulations are developed with individuals on wards, under the home treatment team and within the community mental health team, with individuals sharing formulations with significant others and keyworkers to ensure ongoing support. In Solent NHS Trust, Portsmouth’s Acute Care Pathway has embedded CCC on its wards: CCC groups are accessed across the pathway, CCC formulations facilitate multidisciplinary team working and inform care planning, CCC treatment is delivered in the community and a CCC passport follows individuals through the system to reduce repeated assessments. The Solent community mental health team service also uses CCC as a ‘foundation intervention’; here, it is effective for mapping out an individual’s distress and how they have become stuck in unhelpful ways of coping. In the Portsmouth and South East Hampshire Older Persons Mental Health Service, in-patient staff value the CCC formulation to better understand individuals and increase staff compassion.

In South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust’s acute in-patient services, CCC has been used in individual psychology sessions to support individuals in making sense of their crises and learning more helpful coping, with support from staff teams to work towards behavioural goals. Here, CCC was adapted into a single-session intervention to suit short ward stays and brief contacts with the home treatment team, Reference Bullock, Whiteley, Moakes, Clarke and Riches8 adapted for video call delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic, Reference Riches, Csehi, Steer, Azevedo, Vasile and Lokhande36 and a co-produced training for multidisciplinary staff was also developed. Reference Harris, Clarke and Riches5

In South West Hampshire, CCC training is being rolled out across the community mental health teams, to support staff in using CCC formulations with all patients and learning basic intervention skills to help break identified cycles. In the newly formed primary care mental health teams, CCC is used across Southampton’s Enhanced Mental Health Primary Care Team. CCC formulation sessions are offered as an intervention and preparatory step before entering individual or group programmes. The approach is also employed in Hampshire primary care networks: for instance, in Totton it is the overarching approach that guides brief psychological interventions. CCC formulations have facilitated team-working, helping to coordinate support with peer support workers, well-being assessors and social prescribers.

More specialist secondary care services have also adopted CCC in Hampshire. For example, the Hampshire Perinatal Team uses CCC to train mother and baby unit in-patient staff and community perinatal staff, to help build relationships with parents, work collaboratively, and identify and break maintenance cycles. In Southern Health’s specialist Homeless Healthcare Service, CCC has been implemented through supervision and team formulation when thinking about individuals who the team may be unable to progress with, eliciting their strengths and providing a CCC-informed shared language in the team.

South West England

In the South West, Avon and Wiltshire Mental Health Partnership NHS Trust’s Bristol in-patient services use the CCC formulation model across all nine of their acute, PICU and rehabilitation wards – both in team formulation and in individual sessions. This has proved to be an effective and accessible way of understanding the crisis and it allows further communication when the individual is transferred between wards or is discharged. Additionally, within the Acute Care service in Wiltshire, staff experience of PICU CCC team formulation sessions has been evaluated over the past year using the Team Formulation Quality Scale; initial results indicate that particular strengths of the team formulation are that it is collaboratively developed, key problems and needs are elicited, and there is exploration of significant life events and social and cultural aspects of individuals. In the Devon Partnership NHS Trust’s North Devon Urgent and Inpatient Care Services, CCC guides multidisciplinary team formulations and individual psychology work across adult acute in-patient and rehabilitation units. In University Hospitals Dorset NHS Foundation Trust’s Acute Inpatient Service, the CCC formulation serves as a cornerstone for guiding interventions across the wards, along with offering recommendations to the community mental health teams on discharge, ensuring a seamless transition process.

Other areas and services

On the borderline between primary and secondary care, CCC has been beneficial in providing a tool and a common language in the East London NHS Foundation Trust’s Bedfordshire Talking Therapies Service. CCC is helping to join up psychotherapy services with community mental health teams, and the benefits of collaboratively working across the system are already being reaped. In the North West, Pennine Care NHS Foundation Trust has been using CCC as the formulation model in Stockport’s in-patient wards for the past 6 years. More recently, community mental health teams (including drug and alcohol services) have adopted the model for use in team formulations and direct joint work with care coordinators, creating a shared language across the Stockport Care Hub. In Ireland, Belfast Health and Social Care Trust’s Acute Inpatient Mental Health Services use the formulation component of CCC as part of their assessment process.

Clearly, CCC has been – and continues to be – innovating mental health services across the UK. Both empirical evidence and the clinical impact in a wide range of acute, in-patient, community and specialist services indicate that piloting CCC on a national level is the next step.

Overcoming challenges to implementation

Implementation of CCC for a national pilot would be relatively light on resources. Dissemination of CCC within routine practice is achieved by 1- or 2-day training for the whole staff group, with additional training for the therapist group providing support and team formulation. Reference Clarke10 In the spirit of co-production, Harris et al Reference Harris, Clarke and Riches5 provide perspectives from patients, carers and staff on what this training should involve. CCC formulations and interventions can be fitted into the regular work of the ward or service as it complements routine care, leading to a trauma-aware and compassionate workforce. Although there are challenges with embedding any approach across a service, including lack of appropriate resources and training, Harris et al Reference Harris, Clarke and Riches5 provide additional staff-generated recommendations for successful implementation of CCC. These include embedding CCC into the culture of a service, integrating CCC into standard care planning procedures, and support from senior staff.

Conclusion and recommendations

Overall, there is a need for a transdiagnostic, psychological, trauma-informed approach in acute and crisis mental health services. This has been emphasised repeatedly by patients, carers and professionals alike. Mental health crisis is a national issue and deserves a national solution. So far, CCC has been richly piloted in a diversity of services in the South of England and has begun to expand to other regions of the UK. A nationwide approach to this piloting is now warranted. Indeed, CCC is likely to be the next step in overcoming the public health problem of mental health crises, as indicated by a continuously growing evidence base and the widespread uptake of CCC. Helping people in crisis to understand the relevance of their past trauma, how it interacts with current hardship and how their attempts at coping may be what is keeping the crisis state alive, will enhance the good work already being undertaken to support individuals accessing acute mental health services, and other services, who are in distress. To achieve all this, more research is needed, comparing impact across sites, and in particular focusing on the patient experience of the CCC approach. Implementing CCC will open up avenues for greater collaboration between mental health professionals, patients and their families, and offer greater continuity of care assisted by a shared psychologically informed formulation, enabling in-patient and community services to adopt a trauma-sensitive approach. This will likely transform acute wards in the direction of compassion, empathy and understanding, as staff teams and individuals using services join up to overcome crises the Comprehend, Cope and Connect way.

About the authors

Joseph Harris is a specialist clinical psychologist at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, UK. Isabel Clarke is a consultant clinical psychologist and clinical lead for the Comprehend, Cope and Connect Programme at Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust, UK. Pedro Aniceto is a practitioner psychologist and team coordinator at Dorset Healthcare University Foundation Trust, UK. Lydia Baxter is a counselling psychologist at Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust, UK. Marisol Cavieres is a lead clinical psychologist for Avon and Wiltshire Mental Health Partnership NHS Trust, UK. Helen Courtney is consultant clinical psychologist with the Community Mental Health Teams, Solent NHS Trust, UK. Catherine Donaldson is a consultant lead clinical psychologist at Belfast Health and Social Care Trust, UK. Mark Draper is a consultant clinical psychologist and acute care lead for psychology and psychological therapies at Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust, UK. Alison Farr is a psychological therapist and Comprehend, Cope and Connect lead for Isle of Wight NHS Trust, UK. Kathryn Gaussen is a consultant clinical psychologist and community lead for Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust, UK. Elke Haworth is a principal clinical psychologist for Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust, UK. Rose Hooper is a principal psychologist for Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust, UK. Holly Jones is a principal clinical psychologist and clinical lead and service manager for Pennine Care NHS Foundation Trust, UK. Hasina Khatun is a consultant clinical psychologist and lead for psychology on the acute care pathway at Solent NHS Trust, UK. Lorna Lennon is a clinical service lead for East London NHS Foundation Trust, UK. Matthew McNaught is a psychological therapist at Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust, UK. Hazel Nicholls is chief psychological professions officer for Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust, UK. Katherine Pearson is a clinical psychologist at Devon Partnership NHS Trust, UK. Jodi Pitt is a principal clinical psychologist for Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust, UK. Megan Wilkinson-Tough is a principal clinical psychologist and head of Bristol Inpatient Psychology for Avon and Wiltshire Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust, UK. Davina Wong is a principal clinical psychologist for Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust, UK. Simon Riches is a clinical psychologist and lead psychologist for research and development at the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King’s College London, UK.

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Author contributions

S.R. conceived the article, its structure and argument. J.H. and I.C. led on the writing of the manuscript. J.H. wrote the section on the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. D.W., J.P., L.B., K.G., M.M., H.N., E.H., M.D. and R.H. wrote sections on Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust. A.F. wrote the section on the Isle of Wight NHS Trust. H.K. and H.C. wrote the section on Solent NHS Trust. M.W.-T. and M.C. wrote the section on Avon and Wiltshire Mental Health Partnership NHS Trust. K.P. wrote the section on Devon Partnership NHS Trust. P.A. wrote the section on Dorset Healthcare University NHS Foundation Trust. L.L. wrote the section on East London NHS Foundation Trust. H.J. wrote the section on Pennine Care NHS Foundation Trust. C.D. wrote the section on Belfast Health and Social Care Trust. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.