Adolescence is a crucial period for mental health, as young people undergo significant physical, emotional, cognitive and social changes. During this time, they may experience intense emotions, stress and pressure from various sources, including academic expectations, peer relationships and personal identity formation. It is also a time when mental health problems such as anxiety, depression and non-suicidal self-injury often emerge. Reference Smith-Fromm and Evans-Agnew1 A meta-analysis of 29 studies involving a total of 80 879 children and adolescents worldwide found that the pooled prevalence estimates of clinically elevated anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic were 20.5 and 25.2% respectively. Reference Racine, McArthur, Cooke, Eirich, Zhu and Madigan2

High school teachers play a crucial role in supporting adolescents’ mental health and well-being, given the significant time students spend in school. Reference Hoover and Bostic3 To effectively recognise and respond to mental health problems, teachers need a comprehensive understanding of mental disorders. Reference Liao, Ameyaw, Liang, Li, Ji and An4 However, educators juggle numerous responsibilities, and their prioritisation of mental health literacy might not be as high as necessary. Studies also suggest that teachers attribute their ignorance of mental health problems to their heavy workloads and other commitments. Reference Frauenholtz, Mendenhall and Moon5 However, the role of schools and teachers in adolescent mental health cannot be overstated. Understanding risk factors and causes, identifying and managing mental health problems, and promoting behaviours that encourage seeking help are all included in mental health literacy. Unfortunately, despite the increasing rates of internalising disorders among adolescents, research has shown that high school teachers in various regions, including Europe, the USA, Asia and Africa, often lack robust knowledge about mental health problems and feel uncertain about aiding students who suffer from them. Reference Liao, Ameyaw, Liang, Li, Ji and An4,Reference Yamaguchi, Foo, Kitagawa, Togo and Sasaki6 In a study conducted in Kenya, teachers recognised learning difficulties (intellectual disability and specific problems such as dyslexia), externalising and internalising problems, bizarre behaviour and problem substance use among students but reported lack of skills and time as the main challenges in dealing with students’ mental health problems. Reference Mbwayo, Mathai, Khasakhala, Kuria and Vander Stoep7 A study from Pakistan highlighted the necessity of specialised training programmes to improve mental health literacy among teachers, particularly in locations with limited resources. Reference Ali, Gul and Irshad8 With the right information and resources, teachers can contribute to creating a school environment that promotes mental health and helps students thrive academically and personally. Therefore, the present study aimed to estimate and evaluate levels of knowledge and attitudes regarding anxiety and depression held by a sample of high school teachers in three countries (Colombia, Kenya and Pakistan) and to investigate any potential associations between a few chosen sociodemographic variables. In addition, we looked at possibilities to pinpoint areas in which teachers may be deficient in fundamental understanding of mental illnesses and in which they might exhibit prejudice towards students with these illnesses, in order to develop teacher training programmes.

Method

The proposed study was conducted in selected schools in three countries (Pakistan, Kenya and Colombia). Initially, seven countries were invited to participate, but only these three agreed to take part and were therefore included. The selection of schools was based on feasibility, taking into account the limited resources and funding available for the study. School selection was also influenced by the willingness of administrators to participate, facilitate access to teachers and support the project’s objectives, particularly in training teachers to enhance their mental health literacy. All the high school teachers in the participating schools were provided information about the study and those who voluntarily agreed to participate were chosen for the study. There was no compulsion to participate. Exclusion criteria include lack of informed consent and teachers who had not engaged in active teaching during the previous 6 months.

Ethical approval

The study was part of an initiative by the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), which gave formal ethical approval for the project (23 April 2023). Ethical approval was also obtained from institutional review boards in the three participating countries: the Institutional Review Board of King Edward Medical University (approval no: 110/RC/KEMU); Kenyatta University’s Ethics Research Committee (approval no. PKU/2627/E1752); and the National Commission for Science, Technology, and Innovation (NACOSTI) (license number NACOSTI/P/23/23559). Schools and teachers were asked to participate in the study after being informed about the research. The study was conducted according to the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Procedure and participants

Following written informed consent, a self-administered questionnaire was used to assess teachers’ mental health literacy. It was in the English language and comprised the following parts.

Demographic variables

Demographic information about the teachers was collected, including age, gender, academic degree, length of teaching experience and prior participation in mental health seminars.

Knowledge about anxiety and depression

The next section of the questionnaire asked questions about anxiety and depression. The Anxiety Literacy Questionnaire (A-Lit) and Depression Literacy Questionnaire (D-Lit) are scales used to assess mental health literacy specific to anxiety and depression. Reference Gulliver, Griffiths, Christensen, Mackinnon, Calear and Parsons9–Reference Griffiths, Christensen, Jorm, Evans and Groves11 Both are 22-item tools, answered with ‘true’, ‘false’ or ‘don’t know’. Sample items include ‘People with anxiety disorder often speak in a rambling and disjointed way’ and ‘Being easily fatigued may be a symptom of anxiety disorder’. Each correct response receives one point and all items are summed to produce a total score (range 0–22). Higher scores indicate higher literacy regarding anxiety or depression. The scales have been used in community settings. Reference Hurley, Allen, Swann, Okely and Vella12–Reference Sebbens, Hassmén, Crisp and Wensley13 In the current study the A-Lit and D-Lit both had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.7. This section also included 17 questions related to anxiety and depression from the quiz in the Mental Health and High School Curriculum Guide, which were answered ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Reference Kutcher, Wei, McLuckie and Bullock14

The last part of questionnaire asked about confidence in providing help. Teachers were asked ‘How confident do you feel in helping a student with a mental health problem?’ (answered on a 5-point Likert scale: ‘not at all’, ‘a little bit’, ‘moderately’, ‘quite a bit’ and ‘extremely’). Reference Imran, Rahman, Chaudhry and Asif15

Data entry and analyses were completed using the SPSS 26 statistical package for Windows. Descriptive statistics were computed for the teachers and responses to questionnaires were evaluated. Independent samples t-tests and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to examine differences in knowledge and attitudes scores between participants as per gender and country. To explore the determinants of the teachers’ knowledge about anxiety and depression, normality of the data was checked using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Since the data were not normally distributed, Spearman’s correlation coefficient was computed. Medians of anxiety and depression literacy scores in the three countries were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test. Multiple comparison between countries was computed if significant group differences in median scores were found. The level of significance was set at α = 0.05.

Results

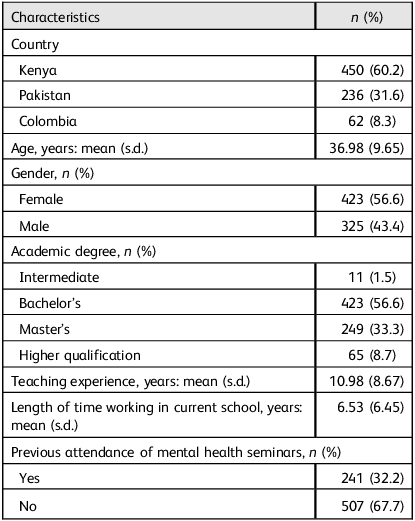

Table 1 shows participants’ demographic data. The sample (n = 748 high school teachers) was predominantly female (56.6%) and most had Bachelor’s qualification (56.6%). Approximately 60% were from Kenya, 31% from Pakistan and 8% from Colombia. The number of years participants had been teaching ranged from 1 to 35 years (mean 10.98, s.d. = 8.67). When asked about sources of previous knowledge about mental health, 18% reported that they had read and learned about mental health on their own, and 32.2 % had attended seminars related to mental health.

Table 1 Participants’ demographic data (n = 748 high school teachers)

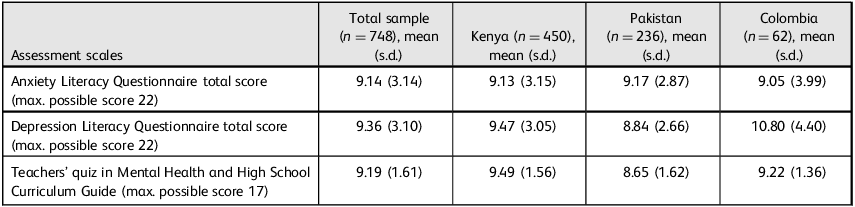

Table 2 shows the teachers’ mean literacy scores regarding anxiety and depression in the three countries. There were no statistically significant differences between genders regarding anxiety and depression literacy in the three countries.

Table 2 High school teachers’ knowledge about anxiety and depression

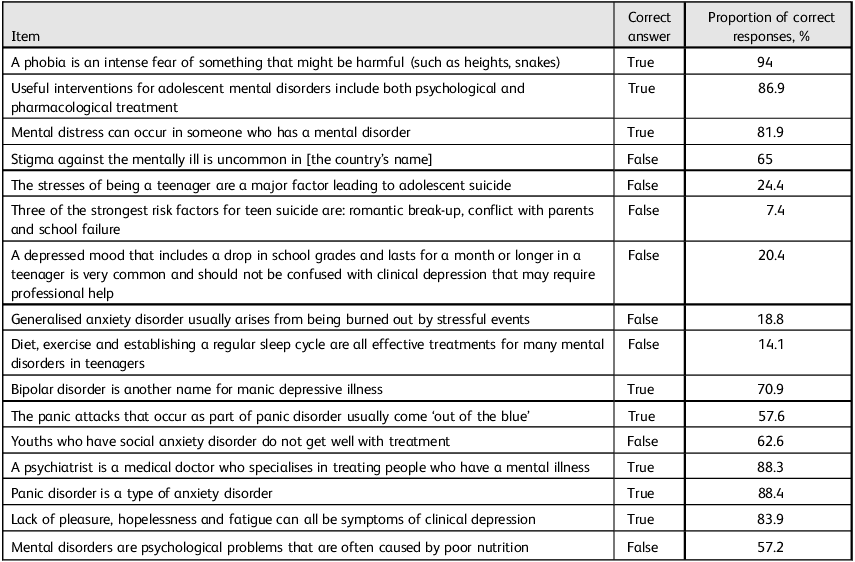

Regarding specific questions about emotional problems (from the teachers’ quiz in the Mental Health and High School Curriculum Guide) many items had low proportions of correct answers. The three items with the lowest proportions of correct answers were: ‘Three of the strongest risk factors for teen suicide are: romantic break-up, conflict with parents and school failure’ (false; 7.4% answered correctly); ‘Diet, exercise and establishing a regular sleep cycle are all effective treatments for many mental disorders in teenagers’ (false; 14.1%); and ‘Generalised anxiety disorder usually arises from being burned out by stressful events’ (false; 18.8%) (Table 3).

Table 3 High school teachers’ knowledge about mental illnesses (emotional problems) a

a. Items are taken from the teachers’ quiz in the Mental Health and High School Curriculum Guide.

Associations between demographic variables and knowledge about anxiety and depression

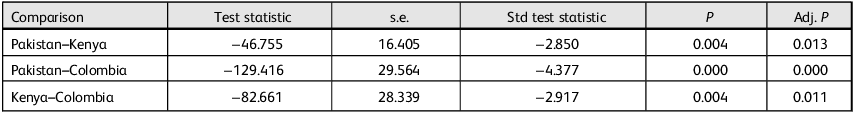

In our exploration of the determinants of teachers’ knowledge about anxiety and depression, we employed Spearman’s correlation coefficient (ρ). We found that literacy about depression and about anxiety were correlated (ρ = 0.545; P < 0.001); total depression literacy was negatively correlated with Pakistan (ρ = −0.135 (P < 0.001) and positively correlated with Colombia (ρ = 0.137; P < 0.001); years of teaching experience was negatively correlated with total depression literacy (ρ = 0.082; P < 0.05); and prior training was positively correlated with depression literacy (ρ = 0.084; P < 0.05) and anxiety literacy (ρ = 0.139; P < 0.001). The Kruskal–Wallis test showed a non-significant difference between the countries in anxiety literacy (z = 0.062; d.f. = 2; P = 0.97) and a significant difference between the countries in depression literacy (z = 21.341; d.f. = 2; P < 0.001). The mean rank of the total depression literacy score for each country was 441.22 for Colombia, 358.96 for Kenya and 311.80 for Pakistan. Multiple pairwise analysis of depression literacy scores between the countries is reported in Table 4.

Table 4 Pairwise comparison of countries on Depression Literacy Questionnaire total scores

Std, standardised; Adj., adjusted.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate knowledge about anxiety and depression held by high school teachers in Kenya, Pakistan and Colombia. Understanding teachers’ perceptions and awareness is crucial, as schools play an integral role in adolescent mental health support and intervention. Reference Eisenberg, Hunt and Speer16 Our study revealed that teachers had limited knowledge about mental health. Most teachers were not aware of the common symptoms of mental illnesses or of basic treatments. In addition, only few teachers felt confident in helping students struggling with mental health problems. This lack of knowledge, low recognition and low confidence may lead to difficulty/inability in supporting students who have mental health problems. It also raises questions about existing support systems and resources available to students who are struggling with anxiety and depression.

Mental disorders such as anxiety, depression and non-suicidal self-injury are prevalent among adolescents and can have significant negative impacts on their overall well-being and academic performance. Reference Mofatteh17 Adolescents spend considerable time with their teachers, who are likely to know them well because of their regular interaction over extended periods. It is therefore crucial for teachers to have a basic understanding of these mental health problems in order to provide appropriate support and intervention for their students. Reference Hoover and Bostic3 Most of the participants in our study did not correctly identify the symptoms of anxiety and depression, believing, for example, that people with depression and anxiety speak in a rambling way and that hearing voices may be a common sign of these illnesses. This finding indicates that there is an urgent need to work with teachers and teaching professionals to help them understand common mental illnesses.

Regarding the treatment of mental illnesses in adolescence, most teachers believed that antidepressants are addictive and that they start working straight away and that acupuncture is as effective as cognitive–behavioural therapy for depression. The majority of teachers also seemed unaware of risk factors for mental illnesses and suicide. This finding is consistent with earlier research indicating gaps in teachers’ preparedness and training in recognising and supporting students’ mental health needs. Reference Patalay and Gage18 A study on mental health literacy among Japanese high school teachers revealed that they generally had low correct recognition rates for major mental illnesses, and relatively few (19%) felt confident in their ability to help students with depressive symptoms. Reference Yamaguchi, Foo, Kitagawa, Togo and Sasaki6 Teachers often feel ill-prepared to support students with mental health problems because of their lack of information and skills in this area. Studies suggest an association between less stigmatising views with better knowledge of depression and suicide and more favourable attitudes towards prevention efforts. Reference Quick19

Our study highlights the importance of sociodemographic factors in understanding teachers’ knowledge and attitudes towards mental health problems. Findings of differences in literacy based on country of residence highlight the potential impact that cultural, educational and systemic factors within different countries can have on mental health literacy. We found no statistically significant differences between genders regarding anxiety and depression literacy, perceived knowledge and information across the three countries studied. Yamaguchi et al noted that correct recognition of specific mental illnesses was significantly lower among male teachers compared with female teachers. Reference Yamaguchi, Foo, Kitagawa, Togo and Sasaki6 In general, although some studies have found gender differences in the recognition of and literacy about mental disorders like anxiety and depression, Reference Yamaguchi, Foo, Kitagawa, Togo and Sasaki6,Reference Ghadirian and Sayarifard20,Reference Gibbons, Thorsteinsson and Loi21 such differences are not always consistent across different populations or settings. The fact that prior attendance of child mental health seminars specifically addressing anxiety and depression improved knowledge scores in those areas in the current study points to the effectiveness of targeted educational interventions in increasing mental health literacy. Reference Dang, Lam, Dao and Weiss22–Reference Nalipay, Chai, Jong, King and Mordeno23 This is also in line with previous studies suggesting a significant association between improved levels of knowledge about mental illnesses and how to deal with students who have mental health problems among teachers who participate in mental health training programmes. Reference Alshammari, Alenezi, Alanzan, AlHawamdeh, Alsulaiman and Alqarni24 It underscores the importance of such training for educators, as it equips them with the knowledge necessary to address these problems in students. Reference Atilola, Ayinde, Obialo, Adeyemo, Adegbaju and Anthony25–Reference Cruz, Lamb, Giri, Vanderburg, Ferrarone and Bhattarai26 Both teacher training in mental health literacy and standardised screening tools have benefits in early detection of student mental health problems. Since teacher training equips educators to recognise problems and offer assistance without the need for more funding, it is more economical and sustainable. On the other hand, screening tools provide organised evaluations but necessitate budgetary outlay and skilled staff. It may be helpful to combine screening tools for focused assessments with empowering teachers through training to support students’ well-being.

Limitations and strengths

The current study has several limitations. It focuses on high school teachers’ knowledge related to anxiety and depression in three selected countries, with uneven sample distribution, which may limit the applicability of findings to other teacher groups as well as generalisability to other geographical areas or countries. Also, although the tools in the study are widely used to assess literacy about depression and anxiety and have shown reliability in study settings they have not been validated in these countries. Another limitation of this study is the potential for cultural biases in self-reported data, particularly given their cross-country nature. Self-administered questionnaires may be subject to bias as participants may not always provide accurate information because of a desire to conform to social norms or because they misunderstand the questions. The cross-sectional nature of the study means it can establish correlation but not causation. It captures knowledge at a single point in time, not allowing for the assessment of changes over time. The study also did not explore the reasons behind the low levels of mental health literacy among teachers, such as potential barriers or challenges they may face in addressing students’ mental health problems. Despite these limitations, the diverse sample from three countries and the large sample size might increase the reliability of the results. Furthermore, association of various demographic factors with knowledge about common mental illnesses provides a more comprehensive understanding of the issues around mental health literacy.

Implications

Our study can inform policy and practice in high school settings so that teachers are able to identify adolescents at risk of mental illness and steer them towards the right type of help. Comprehensive strategies are required to improve teachers’ knowledge and attitudes regarding common mental disorders among adolescents. By understanding mental health problems and the potential impact they can have on students, high school teachers can play a vital role in mental health promotion and illness prevention efforts in schools.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (N.I.) on request.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dinesh Bhugra, Emeritus Professor of Mental Health and Cultural Diversity at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London, for review and suggestions regarding manuscript, and to Dr Usman Ali for helping with statistical analysis. We thank all the administrative staff and teachers in the schools that participated in the study.

Author contributions

Concept/design: N.I., D.M.N., R.N.C.R., A.J.; data acquisition: N.I., D.M.N., R.N.C.; data analysis and interpretation: N.I., D.M.N., R.N.C.R., A.J.; drafting manuscript: N.I.; critical revision of manuscript: D.M.N., R.N.C.R., A.J.; final approval and accountability: N.I., D.M.N., R.N.C.R., A.J.; supervision: A.J.; securing funding: A.J.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the World Psychiatric Association’s School Mental Health Project.

Declaration of interest

D.M.N. is a member of the BJPsych International editorial board and did not take part in the review or decision-making process of this paper.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.