Introduction

Hate crimes in the USA hit a record high, rising by 11.6 per cent in 2021 alone (Lybrand and Duster Reference Lybrand and Duster2023).Footnote 1 Since the COVID-19 outbreak, anti-Asian hate crimes have seen a particularly alarming rise, soaring by 124 per cent in 2020 and 339 per cent in 2021 (Yam Reference Yam2022). The Atlanta spa shootings in March 2021, targeting three Asian-owned spas and resulting in eight deaths, underscored these troubling trends.

Existing research on hate crimes has largely focused on their domestic impact (for example, Nam, Sawyer and Style Reference Nam, Sawyer and Style2022; Dipoppa, Grossman and Zonszein Reference Dipoppa, Grossman and Zonszein2023). However, racial hate crimes in the USA now extend beyond domestic concerns. Following the Atlanta incident, for example, world leaders, including those from the United Nations (Haq Reference Haq2021), South Korea (Martin and Yoon Reference Martin and Yoon2021), Japan (Yamanouchi Reference Yamanouchi2021), China (Global Times 2022), and the Philippines (Philippine Consul General 2022), expressed ‘grave concerns’ over ‘the rise of violence against Asians and people of Asian descent.’ The incident also received significant attention from international news outlets, with front-page coverage in major Asian newspapers.Footnote 2

We investigate how domestic racial hate crimes in the USA affect the foreign public’s perception. Hate crimes targeting Asian-Americans can shape the views of the foreign public toward the USA. To investigate this, we conducted a novel survey experiment across nine Asian countries – China, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam – where citizens often share a collective ‘pan-Asian’ identity or a sense of linked fate with Asian-Americans.Footnote 3 Respondents were randomly assigned to three groups: one group received information about the prevalence of racial hate crimes in the USA, another received the same information along with a message about U.S. Congress passing legislation to reduce hate crime incidents, and the last group served as the control.Footnote 4

The main findings are striking: information about hate crime incidents in the USA resulted in a significant increase in unfavourable views of the USA (−10.1pp), decreased confidence in the USA (−6.3pp), and increasingly negative perceptions of American democracy (−6.5pp), American ideas and customs (−11.0pp), and American people (−11.8pp). Importantly, this effect was not observed in views of American pop culture, suggesting that our experiment results are driven by relevant information rather than irrelevant factors such as the negative tone of the event. Furthermore, the message about the U.S. Congress passing anti-hate crime legislation helped alleviate unfavourable views towards the USA (+3.5 pp), increased confidence in the USA (+2.3 pp), and improved perceptions of American ideas and customs (+5.7 pp). The positive impact of the U.S. Congress passing anti-hate crime legislation indicates that people update their beliefs on the country’s reputation using relevant information, highlighting the crucial role of legislative actions in shaping foreign perceptions. We further investigate the individual-level variations and find that the negative impact is more pronounced among individuals with initially high confidence in the USA, who also exhibit the most significant positive response to legislative interventions.

Our research demonstrates that hate crimes against racial minorities can have far-reaching negative effects on a global scale. Prior studies show that the American public, who place a higher value on human rights and international law, tends to show a less favourable view of those states that violate individual freedoms (for example, Cao and Xu Reference Cao and Xu2015; Chu Reference Chu2021; Putnam and Shapiro Reference Putnam and Shapiro2017; Tomz and Weeks Reference Tomz and Weeks2020). Similarly, racial hate crimes in the USA can expose deep-rooted biases or widespread support for such behaviour in the US (Braun and Koopmans Reference Braun and Koopmans2014; Dancygier Reference Dancygier2023), resulting in mistreatment and marginalization of certain racial or ethnic groups. As indicators of social norms and values fostering violence against racial minorities (Green, Strolovitch and Wong Reference Green, Strolovitch and Wong1998), these hate crimes adversely affect the reputation of the USA. More broadly, these findings align with the literature on the impact of domestic political events on a country’s international reputation. For instance, Bateson and Weintraub (Reference Bateson and Weintraub2022) find that the election of Trump in 2016 led to a decline in trust in the US government among Latin American countries, likely due to his discriminatory rhetoric. Our findings, together with this literature, underscore how domestic discrimination can harm a nation’s reputation abroad across regions.

Second, racial crimes can have a profound impact on international audiences with close racial connections to the targeted minorities. An increase in anti-Asian hate crimes can signal a prevalent antagonism against the Asian community in the USA, leading to increasing perceptions of discrimination against Asians, extensively covered by news outlets in Asia. Such international attention to racial hate crimes in the USA can directly influence the perceptions of foreign citizens towards the USA. While our study cannot directly test the role of racial connections and whether the effects are more pronounced in Asian countries compared to others, we offer evidence that these incidents shape negative perceptions in Asian countries with strong ties to the Asian community in the USA.

Lastly, our findings emphasize the positive effect of taking public action against racial hate crimes. This underscores the significance of addressing hate crimes in the USA, not only as a domestic concern but also as a matter of global importance for the country’s reputation and soft power. With the recent concerns about the American commitment to upholding liberal democratic norms in its domestic politics (Przeworski Reference Przeworski2019; Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2019), emerging works show how domestic events in the USA can play a crucial role in shaping the perceptions of foreign nationals towards the USA (Goldsmith and Horiuchi Reference Goldsmith and Horiuchi2022). Our findings suggest that, in the face of challenging domestic events, how political elites respond with policy discourses can play a crucial role in tackling the potential erosion of trust and confidence.

Design

We conducted survey experiments in nine Asian countries – China, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. By performing the same poll in nine countries with diverse political structures, geographic regions, adherence to democratic standards, and human rights policies, we intend to incorporate purposive C-variations (Egami and Hartman Reference Egami and Hartman2022), lessening the possibility that our main findings are a result of particular political characteristics in some countries. The survey experiment was administered through Qualtrics from March to June 2022. In total, 15,452 adults successfully completed the survey and passed the attention checks.Footnote 5

Respondents were assigned to one of three conditions – one control group (Control) and two treatment groups (Hate Crime and Hate Crime+Congressional Action). All respondents received a set of questions asking their attitudes toward the US favorability, confidence in the USA, views toward American ideas and customs, American democracy, and American people. Participants in the control group answered these questions based on their prior beliefs. Participants in the two treatment groups were presented with a news brief-style vignette based on an FDI report, detailing the recent surge in hate crimes in the USA, particularly racially motivated attacks targeting Black and Asian Americans (Hate Crime). The second treatment group (Hate Crime+Congressional Action) received additional information about the U.S. Congress passing legislation aimed at addressing anti-Asian hate crimes and reducing the number of such incidents.Footnote 6 We chose the congressional action information over other possible alternatives (for example, the Presidential address) for three main reasons. First, it accurately reflects the fact that the U.S. Congress passed the COVID-19 Hate Crimes Bill with overwhelming support from both chambers, which was signed into law by President Biden on May 20, 2021. Second, the bipartisan support for the bill in Congress can serve as a clear signal that US elites as a whole reject anti-Asian hate crimes. Elite responses with policy discourses play a crucial role in tackling the potential erosion of trust and confidence (Goldfien, Joseph and McManus Reference Goldfien, Joseph and McManus2022; Agadjanian and Horiuchi Reference Agadjanian and Horiuchi2020), to the extent of changing social norms and reducing racist and intolerant discourse by signalling the efforts to build a new social consensus (Siegel and Badaan Reference Siegel and Badaan2020; Marble et al. Reference Marble, Mousa and Siegel2021). Lastly, even symbolic actions often carry more weight than words when it comes to addressing challenging social issues like racial hate crimes. If international audiences interpret US congressional action as a serious elite-level attempt to heal the wound caused by the rise in racial hate crimes, exposure to information about congressional action is expected to mitigate the negative effects of Hate Crime information.

Our experimental treatments are based on ‘real-world’ events that preceded the experiment. Given that hate crimes targeting Asians in the USA were widely reported in Asian countries, it is plausible that some individuals had exposure to information about these incidents prior to their participation in the experiment. Consequently, the effects of treatment information on the rise of hate crime incidents might capture both priming effects, whereby individuals previously informed about hate crime incidents are primed to consider hate crime events in their assessment of the USA, and genuine information effects, which reflect first-time exposure to hate crime information (or re-exposure to news they had previously encountered but forgotten). It should also be noted that due to the potential ‘pretreatment effect’ (Druckman and Leeper Reference Druckman and Leeper2012), the estimated ‘treatment effects’ in our experiment may underestimate the ‘true’ information effects.

One potential concern regarding our design is the potential influence of a mood effect or satisficing. Respondents may evaluate the USA negatively, not necessarily due to the content of the information on hate crimes but because of its negative tone. Also, respondents may infer the experimenter’s intentions from the hate crime information and provide negative responses to all the questions. To address these possibilities, we included an additional question regarding respondents’ attitudes toward American music, movies, and television, which can serve as a non-equivalent dependent variable that should not respond to the treatment information (Campbell and Cook Reference Campbell and Cook1979; Goldsmith, Horiuchi and Wood Reference Goldsmith, Horiuchi and Wood2014; Lyall Reference Lyall2019). We expect that exposure to information on anti-Asian hate crimes may not significantly impact respondents’ attitudes toward American pop culture compared to their attitudes toward the USA and its people, ideas, norms, and institutions. This helps us understand if respondents are responding to the content of the information rather than its tone or their perceived experimenter’s intention.

Results

Effects of Racial Hate Crime on the USA’s Image in Asian Countries

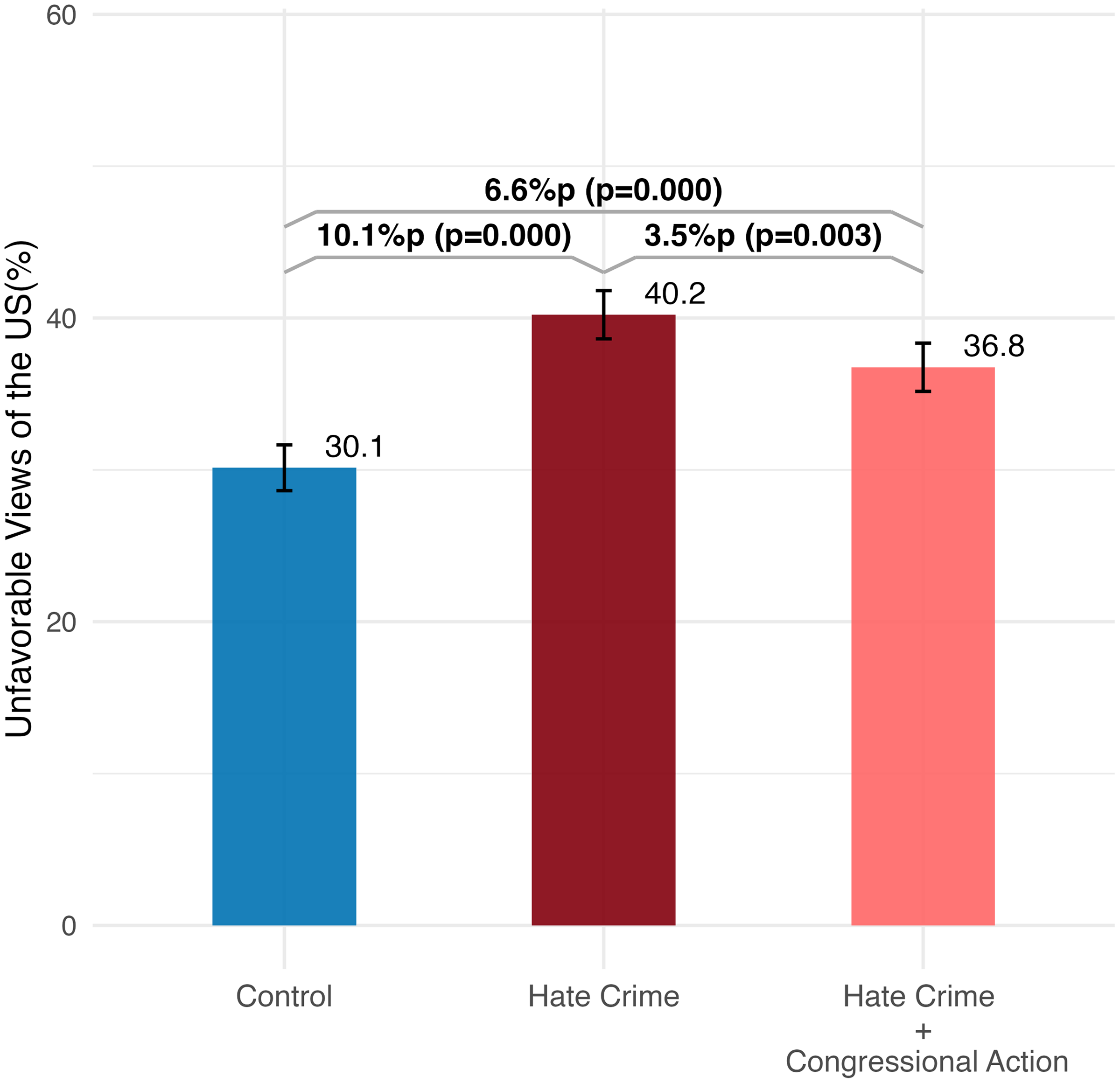

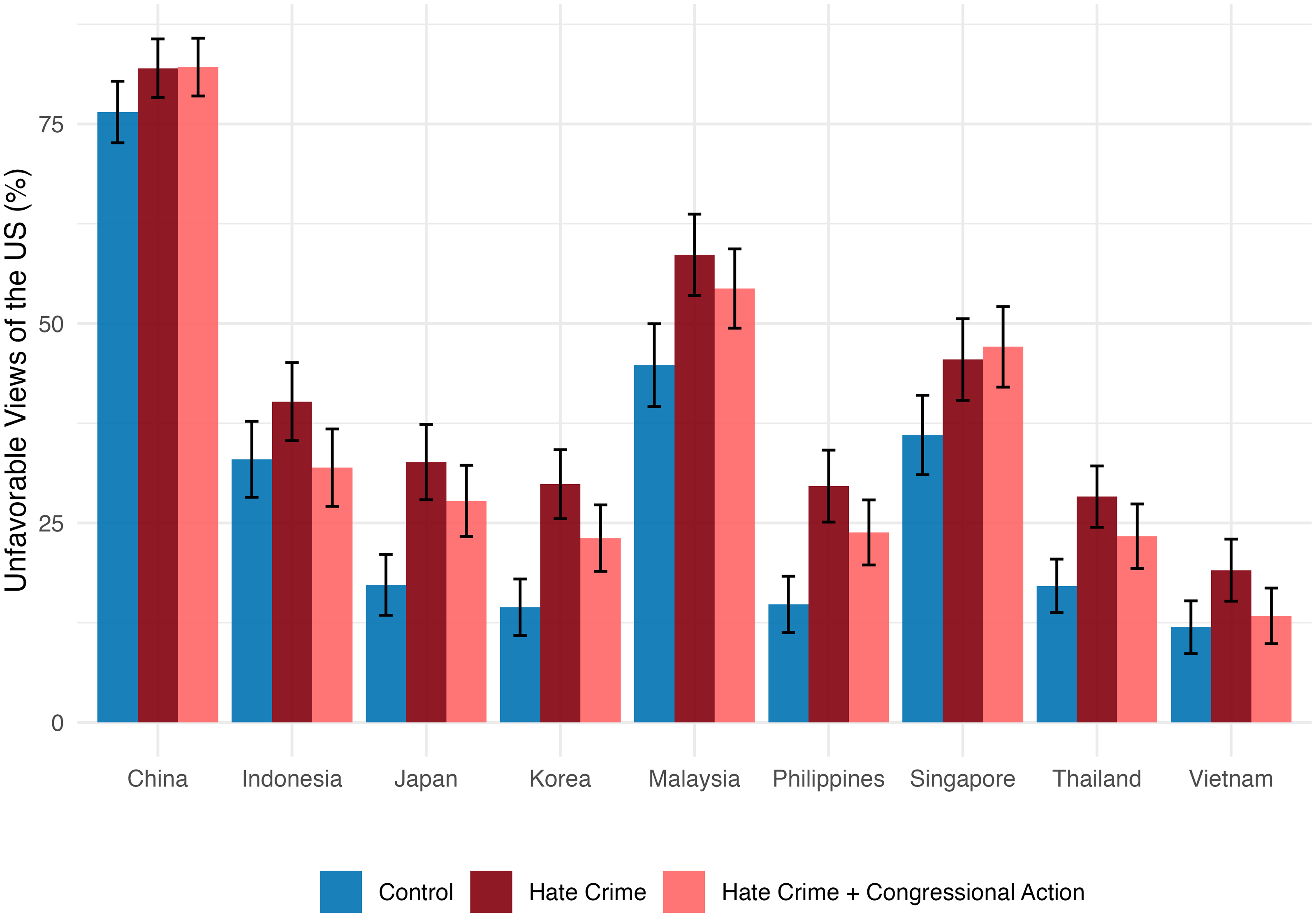

We display the results of our experiment following the style of Figure 1. The first blue bar represents the percentage of respondents who hold negative views toward the USA without the treatment information (Control). The dark red bar represents the percentage of respondents who received information on the rise of racial hate crime incidents (Hate Crime). The bright red bar at the rightmost indicates the percentage of respondents who received the identical treatment along with additional information about the U.S. Congress passing legislation aimed at addressing hate crimes (Hate Crime + Congressional Action). Mean differences are displayed at the top of bar graphs.

Figure 1. General views on the USA.

Figure 1 shows that exposure to Hate Crime information increases the likelihood of holding unfavourable views toward the USA by 10.1 percentage points.Footnote 7 By contrast, the additional exposure to the congressional action information decreases the likelihood of holding unfavourable views toward the USA by 3.5 percentage points. This indicates that the congressional action information can significantly mitigate the negative effects of racial hate crimes on attitudes toward the USA. However, it is also clear that the effect of the congressional action information is insufficient to counteract the negative impact of Hate Crime information. Compared to the control group, the exposure to Hate Crime+Congressional Action information still increases the likelihood of holding unfavourable views toward the USA by 6.5 percentage points.

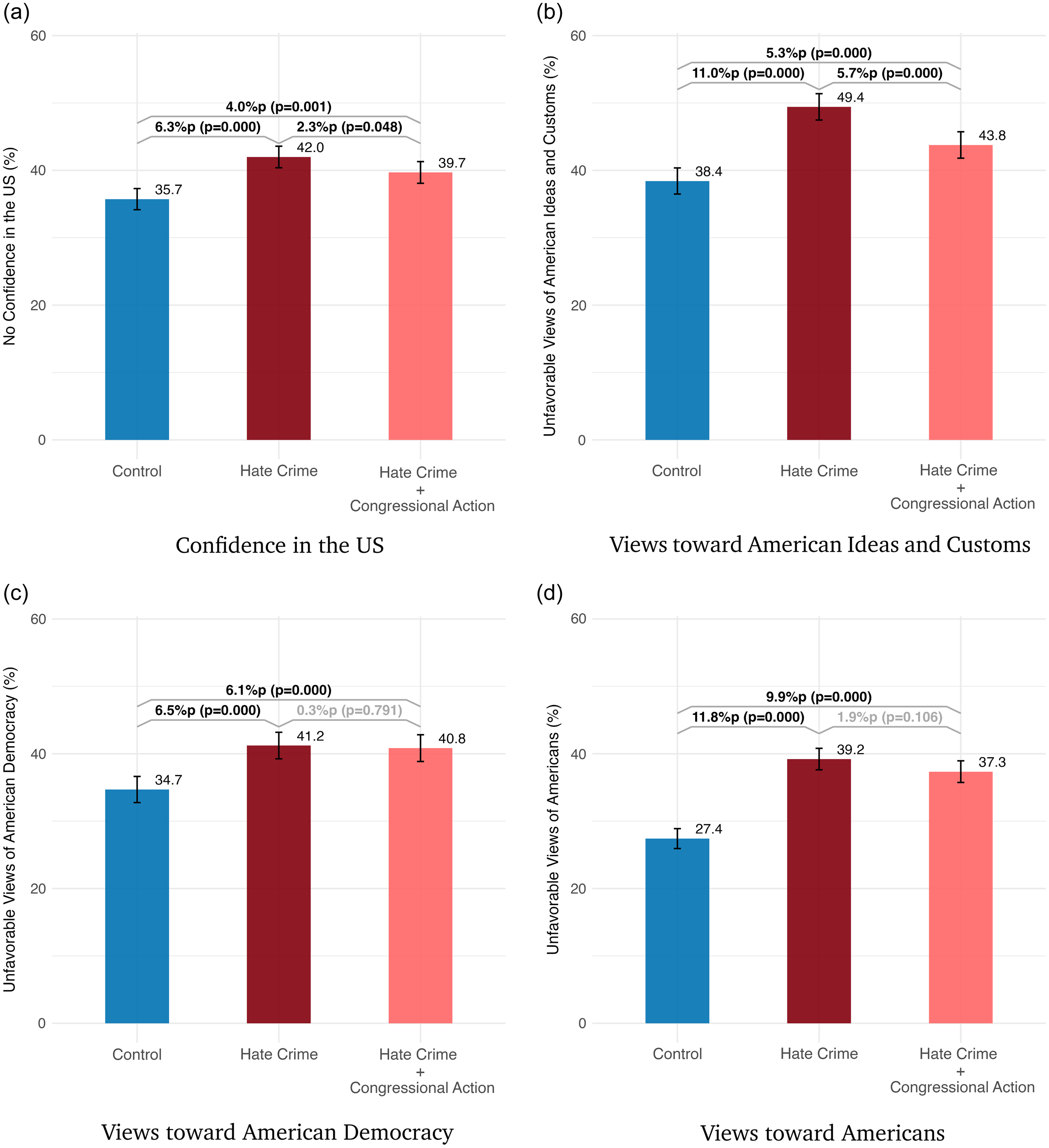

Figure 2 presents the effects on four additional attitudinal variables. Panels 2a and 2b demonstrate that exposure to Hate Crime information increases the likelihood of holding unfavourable views toward the USA, and providing information on congressional action partially mitigates this negative effect. The impact of Hate Crime information and the mitigating effect of Congressional Action appear to have a more substantial influence on views toward American ideas and customs compared to confidence in the USA. Panels 2c and 2d reveal a similar pattern in the effect of Hate Crime information, but there is no statistically significant mitigating effect of congressional action information. While exposure to Hate Crime information leads to an increase of 6.5 percentage points in negative views toward American democracy and 11.8 percentage points in negative views toward Americans, information on Hate Crime+Congressional Action does not appear to mitigate the negative effect of hate crimes on these attitudes.

Figure 2. Effects of Hate Crime and Hate Crime+Congressional Action on four negative attitudinal variables toward the USA.

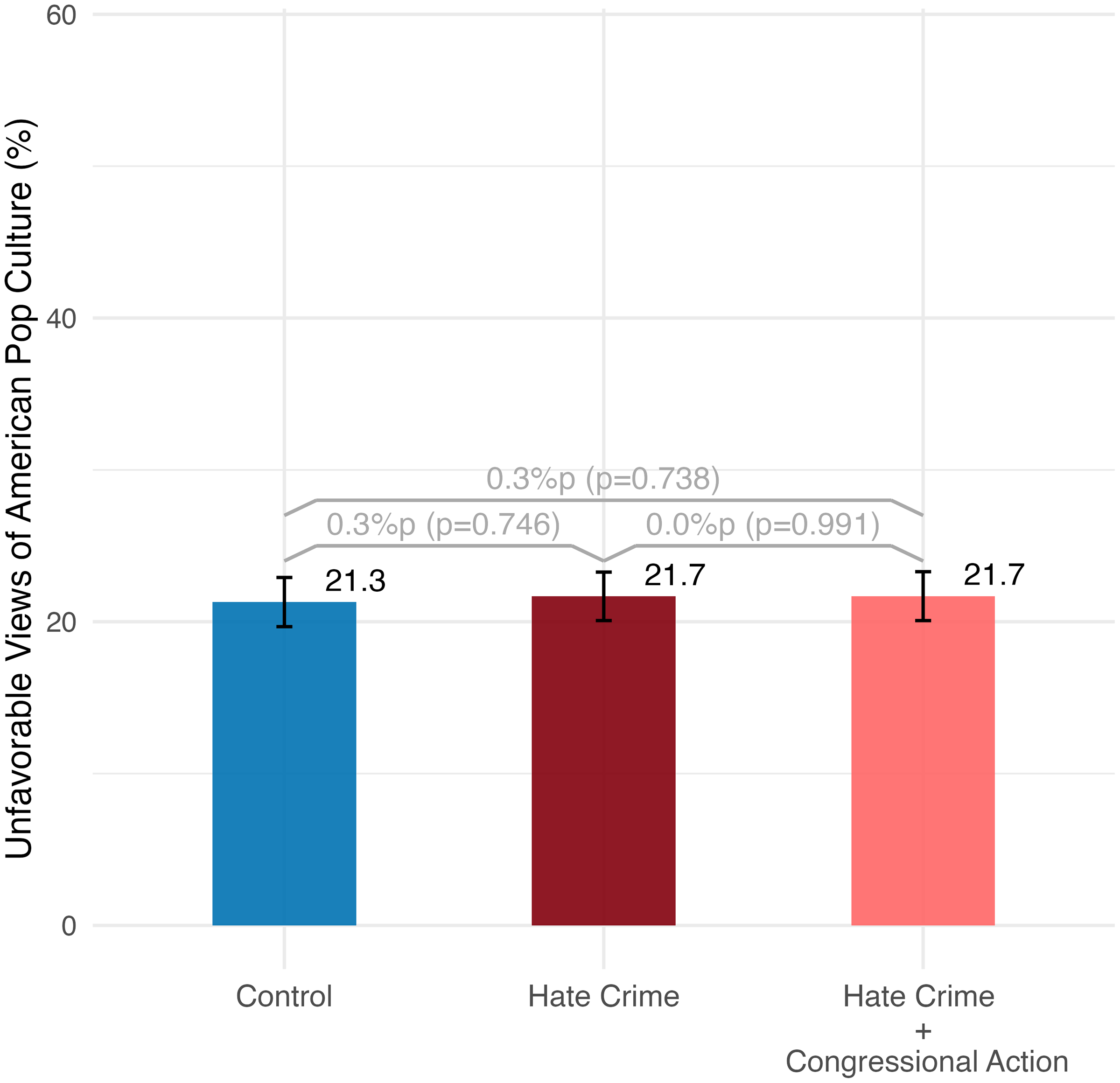

An important concern in our experiment is the potential influence of the negative tone conveyed by hate crime information, which could lead respondents to simply shift their attitudes toward the USA due to mood changes or satisficing behaviour rather than genuinely updating their beliefs based on the message. To rigorously assess this possibility, we included a question asking respondents about a somewhat irrelevant issue: the views toward American music, movies, and television. If respondents’ attitudes on this topic also changed, it would suggest a mood effect rather than genuine information updating. Conversely, if there is no change in attitudes toward American pop culture, it supports the validity of our findings, indicating that hate crime information genuinely impacts attitudes toward the USA through information updating. This cautious approach ensures the reliability of our results in understanding how hate crime-related information affects the foreign public’s belief update on the USA. Figure 3 shows that the exposure to Hate Crime information or Hate Crime+Congressional Action information does not affect respondents’ views on American popular culture.

Figure 3. Results on the views toward American popular culture.

To summarize, we find that exposure to information about hate crimes has a negative impact on attitudes toward the USA across all aspects we examined: general views of the USA, confidence in the USA, views on American ideas and customs, views on American democracy, and views on Americans themselves. There is no doubt that the increasing incidence of racial hate crimes targeting Asian individuals in the USA has worsened the reputation of the USA among citizens in Asia. However, we also find that congressional action to address the deep-rooted racial violence targeting Asian Americans has significant effects in mitigating the negative impact of anti-Asian hate crimes in the USA on the attitudes of Asian citizens toward the country.

Country-Specific Effects of Racial Hate Crimes

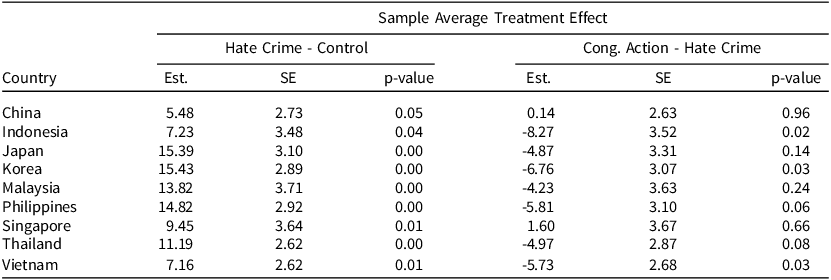

Next, we present the country-specific treatment effects. Table 1 and Figure 4 display the country-specific effects of hate crime information and information about congressional actions on general views toward the USA. In Table 1, the first three columns present the mean difference between the group that received no information (Control) and the group that received information on the rise of racial hate crime incidents (Hate Crime), along with the standard errors and p-values. The next three columns present the same set of information based on the difference between (Hate Crime) and (Hate Crime + Congressional Action). In all sampled countries, the country-specific treatment effects of receiving information about hate crimes are statistically significant at the 95 per cent confidence interval. The moderating effects of congressional action information are less pronounced but still substantial and statistically significant in a few sampled countries.

Table 1. Country-specific treatment effects: The response is whether a respondent holds an unfavourable view of the USA

Figure 4. General views of the USA across treatment groups: By country.

The magnitude of the country-specific effects varies significantly. The negative impact of hate crime information is most pronounced in South Korea, followed by Japan, the Philippines, and Malaysia. The negative effect is least pronounced in China, most likely due to ceiling effects attributable to the already low baseline favourability toward the USA in China compared to other surveyed countries.Footnote 8 The findings reveal that the effects of Hate Crime treatment are substantial for countries with initially more favourable attitudes, such as Japan and South Korea.Footnote 9 By contrast, Hate Crime treatment effects are less substantial in China and Indonesia than in others. These results imply that the USA may face a higher reputational cost due to an increase in racial hate crimes in countries where public opinion is more positively inclined toward the USA.

However, the mediating effect of congressional action is most substantial in Indonesia, followed by South Korea and the Philippines. While information about legislative responses against hate crimes does not fully mitigate their detrimental effects in all sample countries, it counteracts the rise in unfavourable attitudes toward the USA in Indonesia, South Korea, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam (with statistical significance at the 90 per cent confidence interval), underscoring the importance of taking public actions against racial hate crimes.

Greater Effects on Pro-USA Audiences

We provide additional analysis results using subgroup information. We begin by exploring how the treatment effects differ across groups of respondents depending on their pre-existing attitudes toward the USA. To capture pre-existing views on the USA, we asked respondents about their opinions on the USA-China competition. Specifically, we used a question on their views toward a USA-led world order (versus a China-led world order). SI Section A7 presents the actual wording of the questions, summary statistics, and subgroup analysis results. Based on the answers to the question, we divided respondents into three groups: pro-USA, pro-China, and indifferent.

Figure 5 illustrates that the treatment effects are greater for the pro-USA and indifferent groups compared to the pro-China group. While we find sizable effects of Hate Crime information on unfavourable views toward the USA for the pro-USA (10.0 percentage points) and indifferent groups (15.0 percentage points), the effect on the pro-China group (4.7 percentage points) is far smaller in terms of the effect size and its statistical significance. Information on Congressional Action appears to mitigate the negative effect of hate crime information for the pro-USA (3.0 percentage points) and indifferent groups (7.7 percentage points), but there is no effect of congressional action information for respondents with pro-China attitudes. Such limited effects for the pro-China group may be attributable to already-prevailing anti-USA views among them: many respondents with pro-China attitudes have unfavourable views of the USA while those in the pro-USA and indifferent groups are only 13 per cent and 31 per cent, respectively, in the control conditions.

Figure 5. Unfavourable views of the USA across different positions on the USA-China Competition.

Discussion

The findings of this paper are clear: the rise of hate crime in the USA harms the USA’s reputation in Asia. When foreign publics are informed about the increasing incidents of racial hate crimes in the USA, it not only leads to significantly more negative perceptions of the country as a whole, but also erodes confidence in American ideas, norms, institutions, and its people. What is particularly concerning is that this negative impact is even greater among those who initially had higher levels of confidence in the USA. At the individual level, individuals who perceive the USA as less responsible for the USA-China friction or those who favour a USA-led world order react more negatively to hate crimes information. At the country level, hate crime information has a significant negative impact across all countries in our sample, particularly in those where the public is more positively inclined toward the USA. In summary, domestic hate crimes in the USA are alienating countries with more favourable attitudes toward the USA.

At the same time, our findings emphasize the need for policy interventions that acknowledge the importance of an appropriate elite response. When the COVID-19 Hate Crimes Act was discussed and eventually introduced in March 2021, sceptics from both ideological spectrums raised doubts regarding its effectiveness in deterring hate crimes, or potential constitutional violations by encroaching on free speech rights or selectively protecting certain groups of people (Bokat-Lindell Reference Bokat-Lindell2021; Zhou Reference Zhou2021). However, as expressed by Elmer G. Cato, the Philippine Consul General in New York, during a press conference following the Atlanta shootings, what the broader Asian community demanded was for ‘[the U.S.] authorities to exert more efforts to remove violent and dangerous individuals from the streets and make everyone – not just Filipinos or other members of the Asian-American community – feel safe again’ (Philippine Consul General 2022). Despite the domestic political challenges, our survey experimental evidence clearly suggests that even symbolic actions of support, as captured by our treatment of congressional action, can partially address the negative consequences of hate crimes on how America and its ideas are perceived abroad. Moreover, our results indicate that such actions are particularly effective in regaining the trust and support of friends who tend to be the most dismayed by the rise of hate crimes in the USA.

This research also contributes to the literature on the effects of hate crime law and the symbolic politics surrounding it. A plethora of studies across various disciplines, such as political science, criminology, law, and sociology, have long investigated whether and how hate crime law successfully curbs hate crimes and promotes law enforcement activity on hate crimes in the USA (for example, Beale Reference Beale2000; Farrell and Lockwood Reference Farrell and Lockwood2023; Haider-Markel Reference Haider-Markel2002; Grattet and Jenness Reference Grattet and Jenness2008; Mason Reference Mason2014; Uhrich Reference Uhrich1999). In particular, since the seminal work by Jacobs and Potter (2000), scholars in this vein of research have predominantly focused on the symbolic rather than instrumental dimension of hate crime law. While the law itself may not significantly change law enforcement behaviours or deter bias-motivated crimes, it can appease two domestic audiences: (1) advocacy groups representing frequently victimized minorities, and (2) the general public, by signalling that legislators are fighting against prejudice and criminals (Grattet and Jenness Reference Grattet and Jenness2008; Mason Reference Mason2014; Beale Reference Beale2000). Our study extends this understanding of the symbolic effects of hate crime law by demonstrating that it can affect not only domestic but also international audiences. The symbolic effects transcend borders, potentially offsetting the negative impact of hate crime incidents on the USA’s image abroad.

Our findings also underscore the importance of taking race seriously in international relations (IR). Despite the importance of recognizing race in IR, there has been relatively little research on the role of race in public opinion about foreign policy (Kertzer 2018). Even in the small number of studies in IR that take the issue of race seriously, the vast majority of such work ‘see race through US lenses’ (Freeman, Kim and Lake Reference Freeman, Kim and Lake2022, 191). With a focus on the phenomenon of racial hate crime, a troubling indicator of racial discrimination within a given country, our study provides evidence of the significant role played by racial concerns in shaping the perceptions of foreign citizens when assessing a foreign nation. These perceptions can have profound and far-reaching implications, including the formulation of unfavourable foreign policies targeting countries where racial hate crimes are prevalent. By shedding light on the intricate relationship between racial hate crime and the evaluations made by foreign publics, our study makes a valuable contribution towards a deeper understanding of the complex dynamics at play in the realm of race in IR. Future research should explore how race shapes world politics in more diverse settings. In the context of our present work one such avenue may be to explore the specific mechanisms through which hate crime information affects the USA’s reputation in Asia, or to further investigate how alliance politics and the USA-China competition directly impact the effects of racial hate crimes on the USA’s reputation.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123424001030.

Data availability statement

Replication data for this article can be found in the Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/XZTVXM.

Acknowledgement

All authors contributed equally to this manuscript. We are grateful to Taeku Lee, Hye Young You, and the seminar participants at the 2023 annual meeting of the American Political Science Association. We also thank Seowoo Chung, Junwoo Suh, and Heesoo Yoon for their exceptional research assistance and the KDI School of Public Policy and Management for their administrative assistance. This research was supported by the KDI School of Public Policy and Management (20210075). Inbok Rhee was supported by the Yonsei University Research Fund (2024220404). Sung Eun Kim was supported by the Korea University Research Grant (K2419611). Jong Hee Park acknowledges the support of the Institute of International Studies at Seoul National University. Joonseok Yang also thanks the Korean Ministry of Education and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF2020S1A3A2A02092791) for supporting this research.