Introduction

Concerns over growing hostility across party lines – that is, affective polarization (Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012, Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019) – have proliferated in recent years. These concerns originated in the American context, where scholars have argued that affective polarization is linked to negative outcomes such as low trust in government and the erosion of democratic commitments (Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021, Reference Druckman, Green and Iyengar2023; Graham and Svolik Reference Graham and Svolik2020; Hetherington and Rudolph Reference Hetherington and Rudolph2015; Kingzette et al. Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021; Levendusky and Stecula Reference Levendusky and Stecula2021), although evidence of its effects on democratic norms is mixed (Broockman et al. Reference Broockman, Kalla and Westwood2023; Voelkel et al. Reference Voelkel2023). Comparative scholarship reports intense affective polarization across many Western polities (Boxell et al. Reference Boxell, Gentzkow and Shapiro2024; Gidron et al. Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2020; Reiljan Reference Reiljan2020; Wagner Reference Wagner2021, Reference Wagner2024).

Research on American politics analyzes the relationship between affective polarization and ideological disputes (Lelkes Reference Lelkes2021; Orr and Huber Reference Orr and Huber2020), and there is comparative evidence that cultural disagreements are increasingly associated with negative out-party affect (Gidron et al. Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2023; Harteveld Reference Harteveld2021). Yet we lack comparative causal evidence on these relationships. Moreover, prior work has not yet parsed out which specific issues drive this process.

We experimentally evaluate whether cultural and economic disputes intensify partisan animosity by analyzing novel survey data collected across ten Western publics. The survey includes a priming experiment asking some respondents to provide open-ended answers to a question about economic policy disagreements, and others to discuss cultural disagreements, while respondents in the control group receive a non-political prompt. We find that respondents in the economic and cultural priming conditions express significantly greater distrust of partisan opponents, compared to those in the control group, and that respondents who discuss immigration in their open-ended answers express greater distrust towards out-partisans, particularly those who are primed to view immigration through a cultural lens. The latter effect is entirely driven by those right-wing respondents who discussed immigration. Our findings substantiate that economic and cultural policy disputes cause out-party animus, and highlight immigration as a key cultural driver of this hostility among citizens with right-wing ideologies.

Which ideological disagreements drive affective polarization?

Scholars of affective polarization have analyzed its relationship to ideological disagreements (Algara and Zur Reference Algara and Zur2023; Homola et al. Reference Homola, Rogowski, Sinclair, Torres, Tucker and Webster2023; Lelkes Reference Lelkes2021; Orr and Huber Reference Orr and Huber2020; Rogowski and Sutherland Reference Rogowski and Sutherland2016),Footnote 1 with several recent studies concluding that cultural issue debates are associated with especially intense partisan animosity (Harteveld et al. Reference Harteveld, Mendoza and Rooduijn2022; Sides et al. Reference Sides, Tausanovitch and Vavreck2022; Gidron et al. Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2023).

The reason may be that cultural issues activate deeply held identities. Norris and Inglehart (Reference Norris and Inglehart2019, 54) observe that “economic issues are characteristically incremental, allowing left and right-wing parties to bargain […] By contrast, cultural issues, and the politicization of social identities, tend to divide into “Us-versus-Them” tribes.” Sides et al. (Reference Sides, Tesler and Vavreck2019, 10; emphases added) summarize this point in the American context:

Issues like immigration, racial discrimination, and the integration of Muslims boil down to competing visions of American identity and inclusiveness. To have politics oriented around this debate—as opposed to more prosaic issues like, say, entitlement reform—makes politics ‘feel’ angrier.

This point about immigration deserves attention. Immigration debates have gained prominence following the rise of radical right parties whose anti-immigration policies are at the core of their platforms (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; Mudde Reference Mudde2007), and scholars document intense animosity between mainstream parties and these anti-immigration parties (Gidron et al. Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2023; Harteveld et al. Reference Harteveld, Mendoza and Rooduijn2022; Helbling and Jungkunz Reference Helbling and Jungkunz2020). Immigration is not always perceived as a cultural issue, however, in that parties often frame it in economic terms (Dancygier and Margalit Reference Dancygier and Margalit2020).

We extend the observational studies discussed above to analyze experimental data across ten Western publics, pertaining to the questions: To what degree do economic and cultural issue debates affect out-party hostility? Is immigration an especially strong driver of this animus?

Empirical Strategy and Data

We analyze data collected online during June-July 2021 by the survey firm Latana in the following countries: the USA, Sweden, Poland, the Netherlands, Italy, Greece, the UK, France, Spain, and Germany.Footnote 2 We sampled roughly 1,000 respondents per country, 11,001 respondents in total, balanced on population distributions with weights on age, gender, and rural-urban residence. We capture party identification using the standard two-stage party ID question used in the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems survey, which asks respondents if they feel closest to a particular political party, and then follows up by asking if they feel a little closer to any political party. Respondents who name a party in either stage are coded as partisans, such that we include both weak and strong partisans. We also collect a range of other relevant pre-treatment variables, including gender, age, political interest, education, rural/urban residence, self-placement on a left-right scale, and pre-treatment affective evaluations of both in- and out-parties. We check both treatment groups for balance against the control group (and each other) and find that we have good balance for most of the variables, with slight deviations from balance on two variables that we control for in our analyses as described below. The case selection covers parliamentary, presidential, and premier-presidential democracies; a variety of plurality and proportional electoral rules; and systems with varying numbers of parties and democratic histories.

Respondents were randomly assigned to two treatment conditions and one control condition (Table A1 in the online Supplementary Information [SI] memo shows samples across groups). We had balance on most of our pre-treatment variables across treatment groups, with the exception of out-party feeling and political interest (see Figure A1 in the Supplementary Materials), which we control for in our regression models when estimating effects. In the two treatment conditions, we asked respondents to describe how parties compete on either economic or cultural issues. The cultural issues condition (N = 3549) question reads:

The last few years have witnessed dramatic political developments. Specifically, parties have clashed over cultural issues such as multiculturalism, immigration and national identity. Different parties hold very different views on these important issues. Can you describe to us what you think are the key cultural issues on which different parties disagree?

The economic issues condition (N = 3659) question wording was:

The last few years have witnessed dramatic political developments. Specifically, parties have clashed over economic issues such as taxes, economic inequality and the welfare state. Different parties hold very different views on these important issues. Can you describe to us what you think are the key economic issues on which different parties disagree?

Respondents in the control group (N = 3793) were asked to describe upcoming vacation plans:

Many people enjoy taking vacations. Some people like to go to the beach, some people like to go into nature and some people like to explore a new city. Think about the next place you would like to go on vacation. Where would you like to go and why?

To analyze how and whether immigration debates influence affective polarization, we explored the issues respondents raised in their open-ended responses. We translated replies into English using the DeepL API and classified respondents according to whether they mentioned immigration. To classify responses, we created dictionaries for each treatment condition based on our careful reading of about 15 per cent of the responses in each condition (Section 2, Table A2 in the online SI memo). We chose different dictionaries for each condition to avoid misclassification across conditions. Thirty-seven per cent of respondents in the cultural condition were classified as mentioning immigration, versus 12 per cent in the economic condition. Given that some of this difference may be due to our cultural conditions question specifically mentioning immigration, we examine the effects of mentioning immigration for both groups. Respondents mentioning immigration in the cultural condition often discussed a sense of cultural threat, for instance, in this response: ‘Immigrants are a threat to many, our country cannot afford immigrants, immigrants do not want our culture.’ In the economic condition, respondents mentioning immigration often referred to perceived welfare burdens, as in the following example: ‘The costs of immigration are not being addressed, as well as crime among those of foreign origin.’

To capture our dependent variable, we asked respondents about trust in rival parties’ supporters:

How much of the time do you think you can trust supporters of opposing political parties to do what is right for your country? Footnote 3

We adopt this question from an influential affective polarization study, which showed that distrust is associated with other commonly used measures of affective polarization (Druckman and Levendusky Reference Druckman and Levendusky2019, 116; see also Levendusky and Stecula Reference Levendusky and Stecula2021; Kingzette et al. Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021).Footnote 4 While this question captures distrust toward all opposing parties without differentiating between different out-parties, it allows us to balance the experimental groups based on the more common measure of partisan affect, the feeling thermometer (Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019), which was collected prior to the experimental treatments. By collecting the thermometer scores pre-treatment and controlling for them in our analyses, we produce especially convincing evidence of the experimental treatment effects. We provide descriptive statistics on the distribution of this variable in Figure A8 (overall sample) and Figure A9 (by country) in the online SI memo.

Results

Main treatment effects

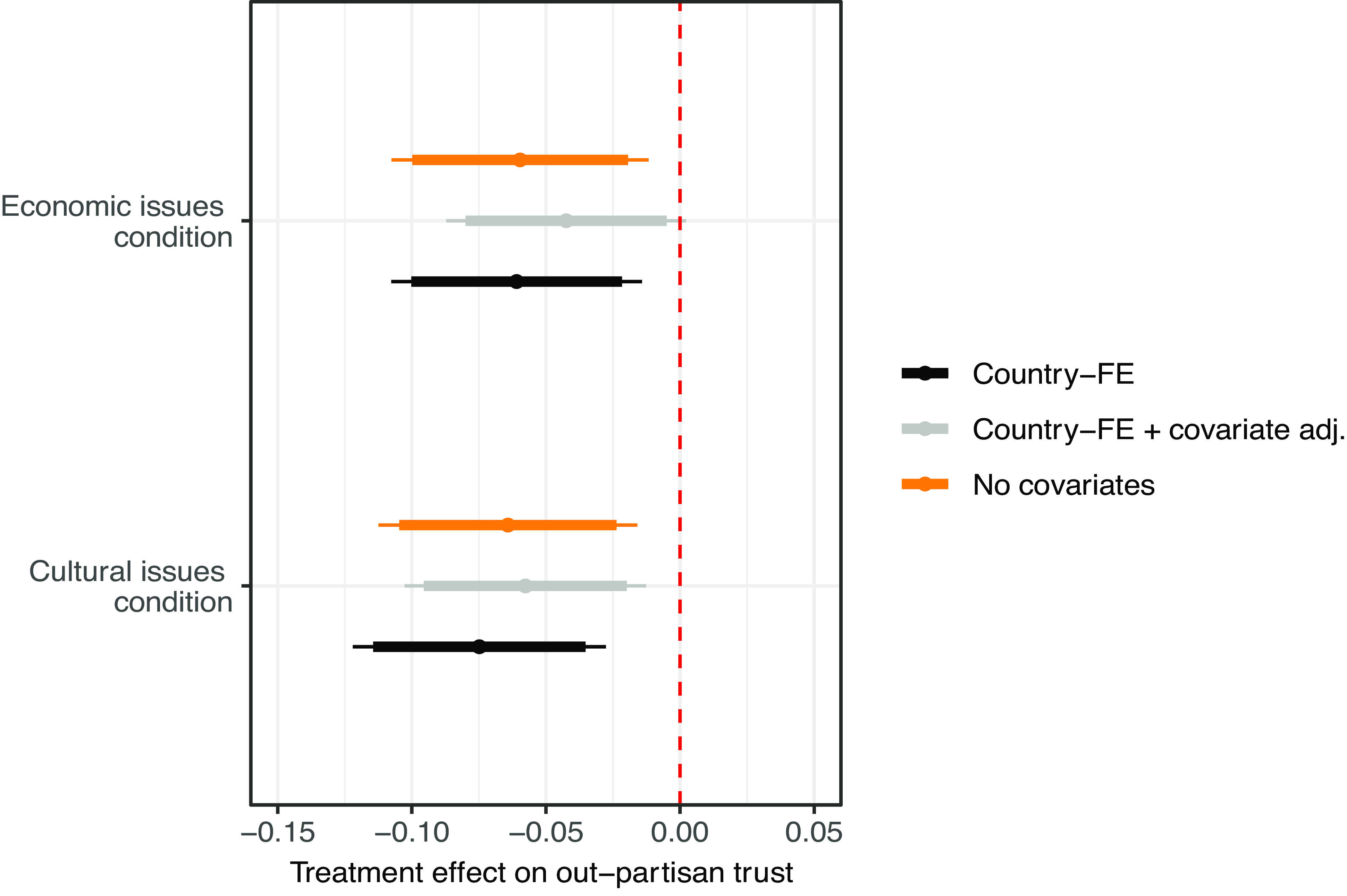

We first report the treatment effects of being primed to think about either cultural or economic issues, relative to the baseline condition (the vacation prompt). For these analyses, we regressed our outcome of interest, trust in out-partisans’ willingness to do what is best for the country,Footnote 5 on the two experimental treatment dummies. Figure 1 displays the coefficient estimates for three models: one with no covariates, one with country fixed-effects only, and one which additionally adjusts for the two unbalanced covariates, namely political interest and out-party affective evaluations based on thermometer scores (the samples are balanced for all other variables included in the data). This latter model provides an especially demanding test, since we balance respondents’ expressed affect towards other parties – obtained prior to the experimental prompts – when predicting how the experimental prompts influence respondents’ trust of political opponents. Both the economic and cultural treatments significantly reduced trust in opposing partisans, and, to a similar degree, the negative coefficient point estimates denote that trust declines by 0.04 to 0.06 standard deviations (in the covariate-adjusted models) for these issue treatments, providing evidence that both economic and cultural debates cause out-party distrust.Footnote 6

Figure 1. Economic and cultural issue treatment effects on trust of out-partisans.

Notes: Horizontal lines denote 95 per cent (thin) and 90 per cent (thick) confidence intervals. The dependent variable was the respondent’s level of trust in opposing parties’ supporters (standardized). The baseline condition was one where respondents were prompted to discuss their vacation plans, relative to the results for the economic and cultural issue treatment conditions, discussed in the text. Detailed regression results are provided in Table A5. We also estimate treatment effects for each country (see Figure A7 in the online SI memo). Results are robust to dropping one country at a time (see Figure A5 in the online SI memo) and to including only partisans (see Figure A10 in the online SI memo).

While the point estimates imply that our issue prompts exerted substantively small (although detectible) effects, our primary interest is in whether, not how much, economic and cultural debates drive out-party distrust because we cannot convincingly answer the latter question experimentally. On the one hand, our experimental prompts were designed to focus subjects’ attention on issue debates beyond the degree to which subjects weigh them in everyday life, and, moreover, some experimental treatments that prime out-party (dis)liking dissipate over time (for a review of this research, see Holliday et al. Reference Holliday, Iyengar, Lelkes and Westwood2024). On the other hand, our prompts could not (and were not intended to) capture the long-term effects of citizens’ exposure to economic and cultural issue debates over a period of years (or decades), which might considerably exceed any effect we can induce in a brief survey experiment. Hence, we explore whether our economic and cultural debates drive out-party distrust, leaving the question of the magnitude of these effects in real-world politics for future research.

Effects of mentioning immigration

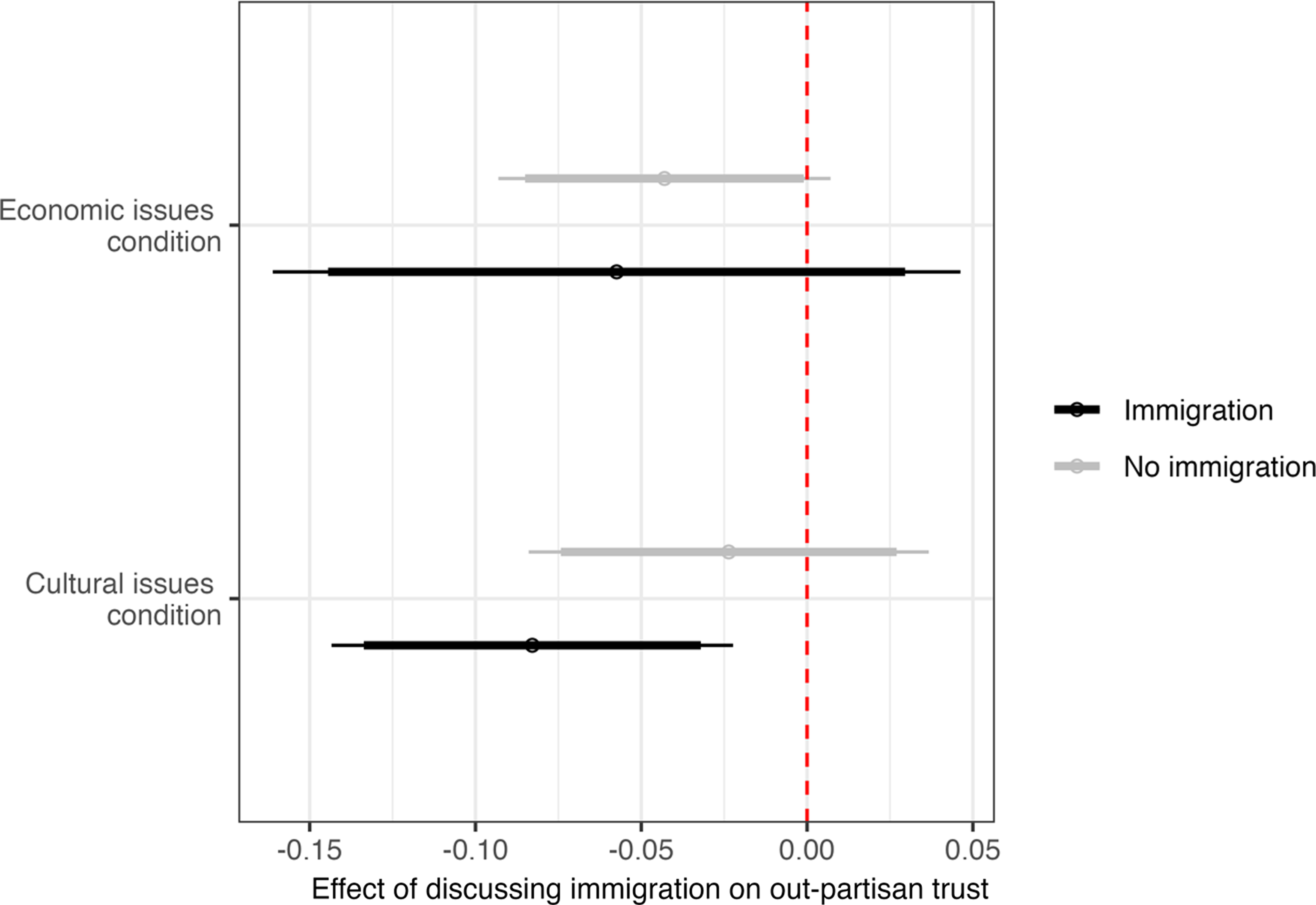

Next, to explore the specific effect of the immigration issue, we analyzed subgroups within each treatment condition, separating respondents who discussed immigration in their open-ended responses from those who did not. Because mentioning immigration may not be randomly distributed in the sample – which would hamper our ability to make causal inferences – we first identified predictors of discussing immigration (see Table A3 in the online SI memo). In a second step, we used entropy balancing to ensure that we compared the subgroups within the treatment conditions to a control group that was balanced on the predicting variables. We also balance our subgroups based on two pre-treatment measures of partisan affect, namely out-party feeling thermometers and preference for partisan social distance.Footnote 7 Figure 2 displays these analyses. We note that our results are robust to balancing on alternative specifications including balancing on additional variables like gender, self-reported left-right placement, a rural-urban dummy, dummy variables for all party families (see Figure A2 in the online SI memo), and using matching instead of entropy balancing (Figure A3 in the online SI memo).

Figure 2. Effect of discussing immigration (using entropy balancing).

Notes: The dependent variable is the respondent’s level of trust in opposing parties’ supporters (standardized). Horizontal lines denote 95 per cent (thin) and 90 per cent (thick) confidence intervals. Treatment and control groups are balanced on predictors of discussing immigration (see Table A3 in the online SI memo), including age, average out-party feeling thermometer ratings and social distance preferences, education, income, political interest, dummies for partisans of nationalist parties, and country dummies. Table A6 reports detailed regression results. Results are robust to only include partisans (see Figure A11 in the online SI memo).

We estimate that respondents in the cultural treatment who mentioned immigration (37 per cent of respondents) express significantly more distrust of out-partisans than a balanced control group (p<0.05). We cannot reliably estimate the effects for respondents in the economic treatment because so few respondents in this condition mentioned immigration (only 12 per cent). However, the point estimate of mentioning immigration in the economic condition is quite similar to that for the cultural condition. To ensure that results are not driven by a single outlier country, we also include jackknife analyses where we drop a single country. Those results, presented in Figure A6 of the supplementary memo, reveal a strongly consistent pattern across countries.

To summarize, mentioning immigration appears to drive out-partisan distrust for respondents who are primed to view immigration as a cultural issue. And, for respondents in both the cultural and economic conditions who did not mention immigration, the point estimates on these treatment effects are near zero and statistically insignificant.

Heterogeneous effects among left- and right-leaning respondents

Our finding that immigration-related concerns are especially potent drivers of out-partisan distrust raises the question: what are the characteristics of those respondents who mentioned immigration in their open-ended answers, and what types of concerns did they raise? As shown in Table A3 in the SI memo, such respondents tended to be older, more interested in politics and disproportionately supported conservative and radical right parties (see the classification into party families in Table A8 in the online SI memo).

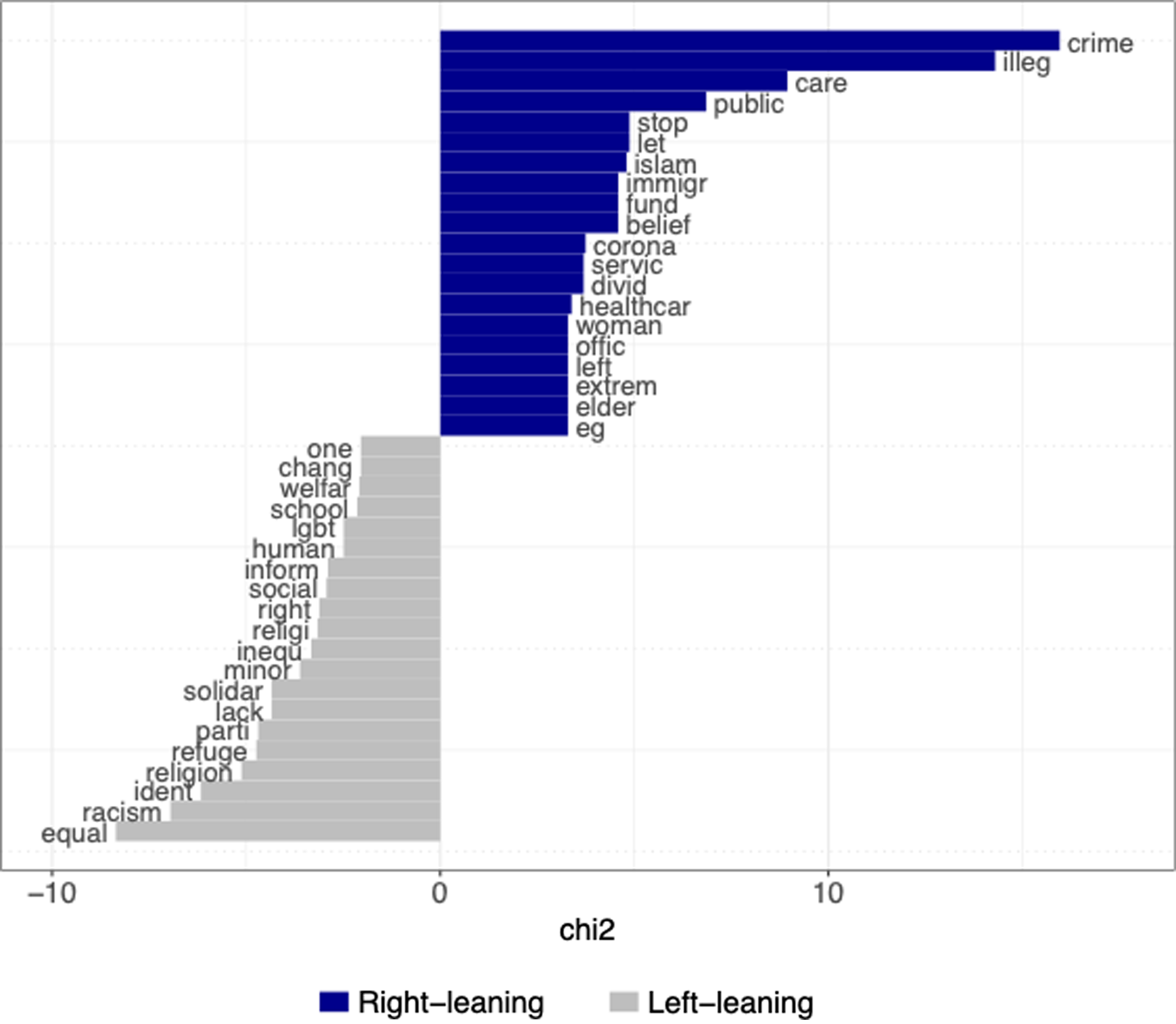

To further explore this issue, we split our sample using respondent’s self-reported left-right position on an 11-point scale, classifying respondents with values between 0–4 as left-wing and values between 6–10, which include most supporters of Conservative parties and nearly all radical right party supporters as right-wing, while excluding those who self-placed at 5, the centre of the scale. First, we assess based on keyness statistics whether right- and left-wing respondents use distinct words when discussing immigration. Figure 3 shows that they do. Right-wing respondents refer more often to illegal immigration (‘illeg’), crime, and strains on public services. Left-wing respondents more frequently address structural inequalities (racism, inequality), social justice and multiculturalism, and more often refer to refugees (‘refuge’).

Figure 3. Keyness statistics for open-ended responses referring to immigration.

Notes: The figure displays the terms mentioned with the greatest relative frequency by right-wing respondents who discussed immigration in their open-ended responses (dark blue) relative to left-wing respondents, along with the terms mentioned with greater frequency by left-wing respondents (light grey). Prior to the analysis, the text was tokenized and stemmed using the quanteda package. Stemming breaks down words to their stem, meaning that ‘immigr’ signals the use of words including ‘immigration’ but also, for example, ‘immigrants’.

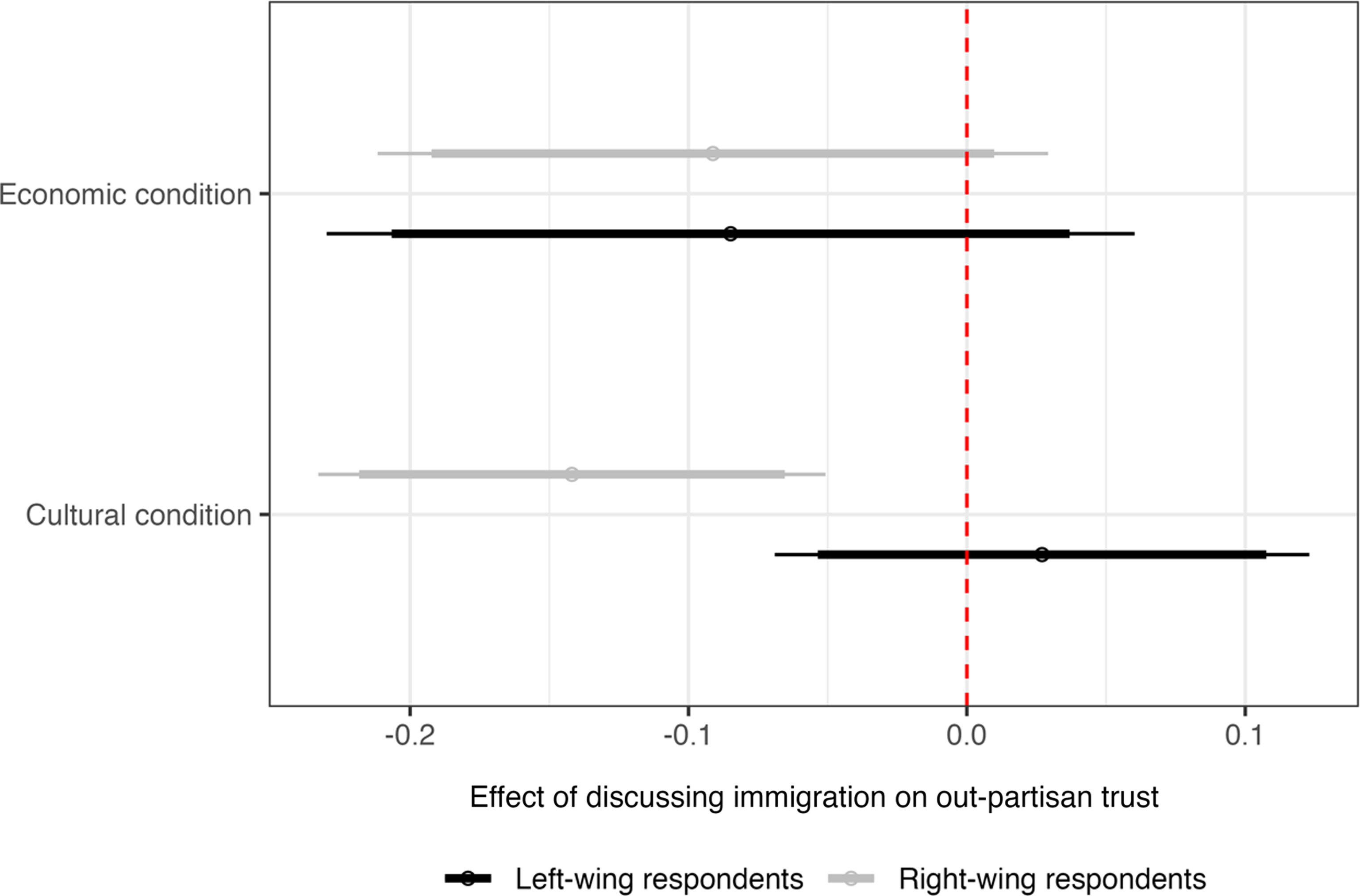

Second, we examine how mentioning immigration affects out-partisan trust differently for left versus right-leaning respondents. As displayed in Figure 4, among those who mention immigration in the cultural condition, right-wing respondents’ out-partisan trust is significantly lower compared to similar respondents in the control group (p<0.01). By contrast, left-wing respondents mentioning immigration in the cultural condition display no detectible trust differences compared to the control group. For the economic condition, we estimate no significant trust differences between left- and right-wing respondents who referenced immigration, although fewer respondents discussed immigration in the economic condition, leading to wider confidence intervals. This pattern holds when controlling for a full set of covariates (see Figure A4 in the online SI memo).

Figure 4. Effect of mentioning immigration among left- and right-leaning respondents.

Notes: The DV is the respondent’s expressed level of trust in opposing parties’ supporters (standardized). Horizontal lines denote 95 per cent (thin) and 90 per cent (thick) confidence intervals. Treatment and control groups were balanced on predictors of discussing immigration (see Table A3 in the online SI memo). Results are robust to include the full set of covariates (see Figure A4 in the online SI memo). Table A7 reports detailed regression results.

Discussion and conclusions

Which ideological disputes drive affective polarization? Our findings from a ten-country survey experiment suggest a nuanced answer: while both economic and cultural policy disputes cause out-party distrust, we find that among respondents who are primed to consider cultural issues, those who hold right-wing ideologies and who also reference immigration in their open-ended responses express especially deep distrust of political opponents. These citizens, who tend to view immigration through the lens of crime, strains on public services, and illegal immigration, are a core demographic of the radical right parties that are gaining support in many Western publics.

Our findings suggest that the growing emphasis on immigration in political debates across Western democracies, documented in previous work (de Vries et al. Reference De Vries, Hakhverdian and Lancee2013; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008), has not only reshaped the ideological space but also the emotional tenor of politics. Future research should consider how economic and cultural perspectives shape both public opinion and citizens’ feelings towards political opponents.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123425000158.

Data availability statement

Replication data for this paper can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ZIKPBD.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the helpful comments we received at the European Political Science Association and the UCL Migration Cluster seminar in 2023.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Israel Science Foundation (grant number 1806/19).

Competing interests

None.