Researchers should avoid traumatization and re-traumatization when possible, minimize traumatization and re-traumatization when avoidance is not possible, and not conduct research when the potential for traumatization or re-traumatization is excessive.

(American Political Science Association 2022, 7)Introduction

Political scientists regularly study topics that relate to traumatic stress. We collect data from research participants about their experiences of being child soldiers (Beber and Blattman Reference Beber and Blattman2013; Banholzer and Haer Reference Banholzer and Haer2014; Blattman and Annan Reference Blattman and Annan2010), of socialization as (ex-)combatants (Annan et al. Reference Annan, Blattman, Mazurana and Carlson2011; Green Reference Green2017; Haer et al. Reference Haer, Banholzer, Elbert and Weierstall2013), and with sexual violence (Kreft Reference Kreft2019; Baaz and Stern Reference Baaz and Stern2009). And we increasingly do lab-in-field experiments in dangerous contexts where participants might experience distress (see for example, Gilligan et al. Reference Gilligan, Khadka and Samii2023; Young Reference Young2019, who made explicit advance provisions for harm or trauma counselling referrals). When discussing or addressing concerns about ethical conduct in such settings, researchers often invoke efforts to prevent retraumatization (for example, Cronin-Furman and Lake Reference Cronin-Furman and Lake2018; Fujii Reference Fujii2012; Revkin and Wood Reference Revkin and Wood2021; Kao and Revkin Reference Kao and Revkin2021; Lyall Reference Lyall2022).

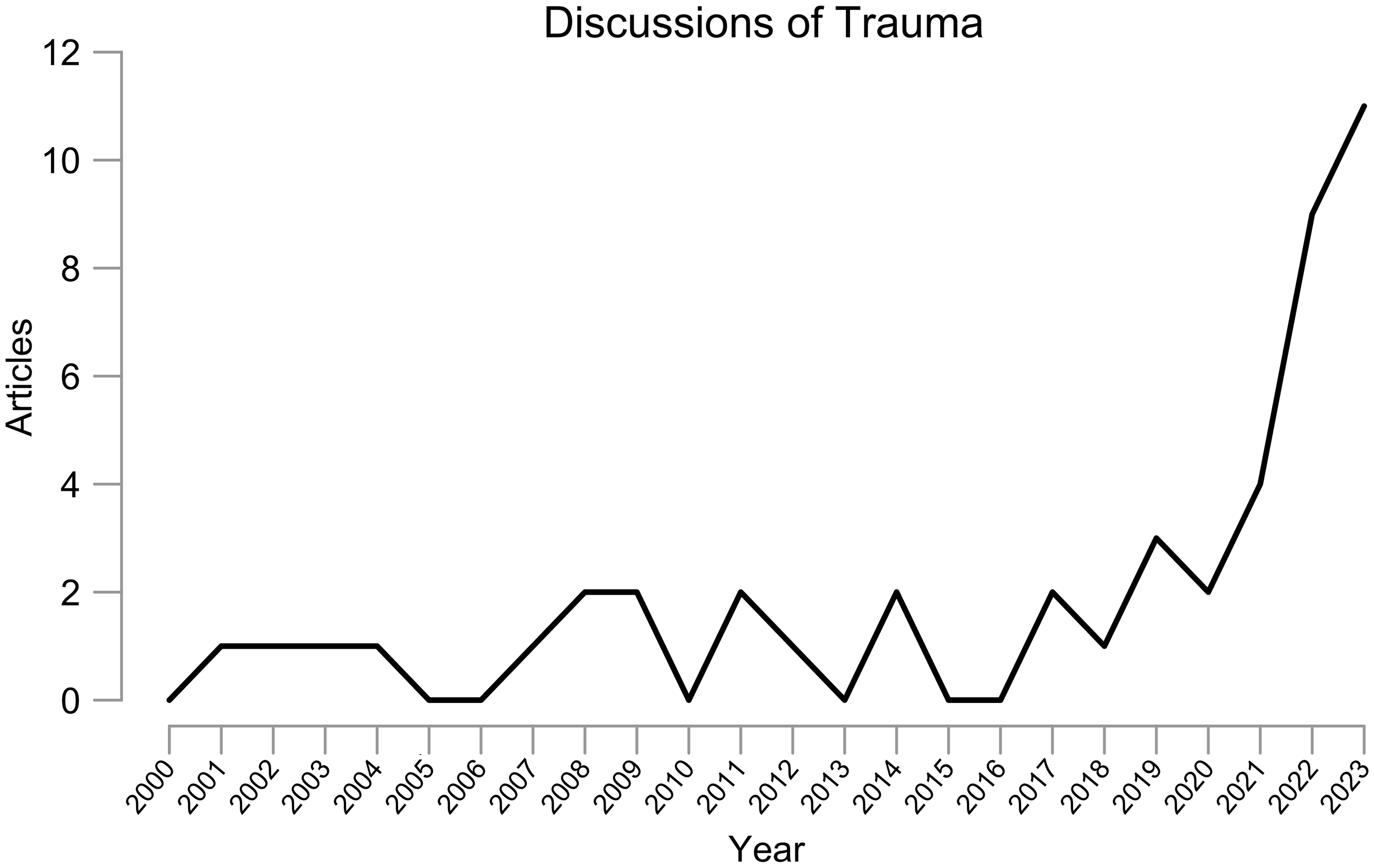

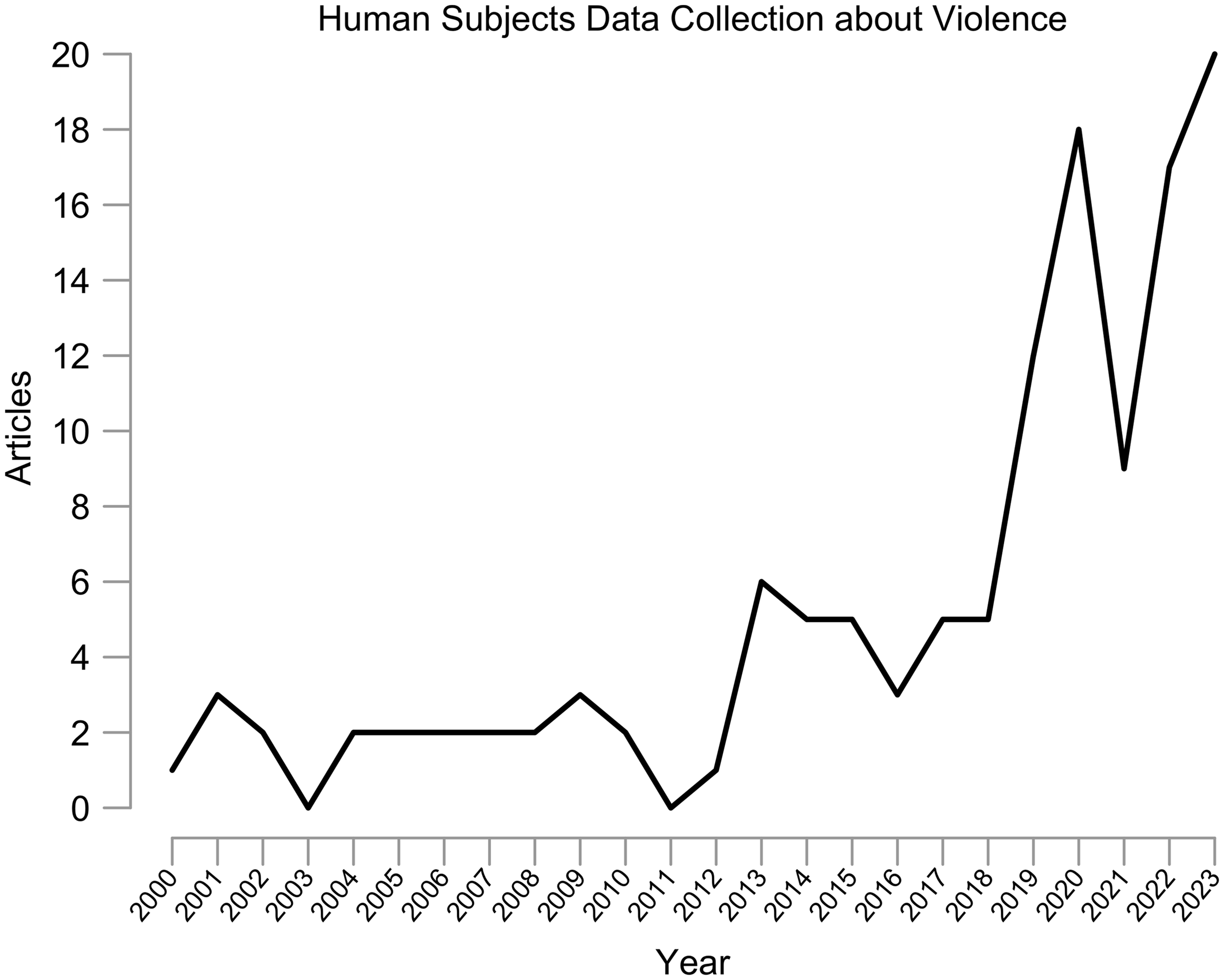

Indeed, the American Political Science Association’s (APSA) research ethics guide, in a section on harms and trauma, states: ‘Research may generate painful emotional or psychological responses from participants, as they are exposed to or asked to discuss sensitive topics. In some instances, the research study itself could cause trauma. In other cases (“retraumatization”), the research may ask participants to recall past injuries, such as human rights abuses In scholarly publications and presentations of their work, researchers should disclose how they assessed and managed the risk of trauma to participants’ (American Political Science Association 2020, 10). Some political scientists appear to be taking up the call. Mentions of trauma in the top three political science journals have increased substantially in recent years (Figure 1), with references to retraumatization specifically beginning in 2019. This trend has coincided with an even greater over- time increase in the number of articles that feature original human data collection on the topic of violence (see Figure 2; note the different scale), a classic case of research that might require a trauma-informed approach to data collection.

Figure 1. Articles that discuss trauma, from the American Political Science Review, American Journal of Political Science, and Journal of Politics (2000–2023).

Figure 2. Articles that feature original human subjects data collection about violence, from the American Political Science Review, American Journal of Political Science, and Journal of Politics (2000–2023).

This paper assesses the evidence about retraumatization in political science research. Its contributions are four-fold. First, it clarifies what retraumatization is (see “Defining Retraumatization”). Second, it evaluates the extent to which retraumatization is a risk in empirical political science research (see “Does Research Retraumatize People?”). Third, it asks how much risk – however minimal – we should accept (see “Is It Wrong to Ask People about Trauma?”). Fourth, it provides a framework for applying ethical concerns about trauma (see “A Framework for Trauma-Informed Political Science Research”).

Questions about the trauma and retraumatization potential of research have become more urgent amid efforts to curtail human subjects research on sensitive topics. For example, political scientists have drawn attention to cases in which research should be discontinued or not started because of harms including including retraumatization. Discussions around discontinuing research because of trauma/retraumatization, like discussions about retraumatization more broadly, cross quantitative and qualitative research (see, for discussions in quantitative and qualitative research respectively, Lyall Reference Lyall2022 proposing the pre-registration of ‘ethical redlines’ for research and Revkin and Wood Reference Revkin and Wood2021 discontinuing human data collection). Some ethnographers have identified ‘refusal’ of research as a critical innovation in studying pain narratives and marginalized groups (for example, Mitchell-Eaton and Coddington Reference Mitchell-Eaton and Coddington2022; Tuck and Yang Reference Tuck and Yang2014b; Tuck and Yang Reference Tuck and Yang2014a). Other efforts to curtail research may reflect overreaching. Institutional review boards often refuse to certify or place onerous demands on research perceived as remotely associated with trauma or retraumatization (Dragiewicz et al. Reference Dragiewicz, Woodlock, Easton, Harris and Salter2023; Schrag Reference Schrag2011) – with experimentalists and qualitative scholars often facing the greatest difficulties (Briggs Reference Briggs2022). An Evidence in Governance and Politics (EGAP) memorandum on APSA’s ethics guidelines calls the harm and trauma section ‘overly vague’ and notes ‘IRBs have denied surveys because they ask attitudinal questions about abortion or sexual assault for fear that mentioning the words might trigger trauma’ (Nickerson et al. Reference Nickerson, Platas, Robinson, Samii and Sinmazdemir2019, 8).

This ‘vagueness’ in professional ethics guidelines reflects both a gap in the political science literature and uncertainty in the psychology literature about what retraumatization is – as opposed to clinical diagnoses like post-traumatic stress disorder. As Baron and Young (Reference Baron and Young2022) note, in an article on transparency in political violence research: ‘Re-traumatization is often used as a shorthand by social scientists for various forms of distress. Yet, the empirical basis for assessing and avoiding the risk of adverse psychological outcomes or any positive psychological benefits in political science research is surprisingly small’ (842). To overcome that gap in the political science literature, this paper draws considerably on work from related social science disciplines, particularly psychology.

Work by clinical psychologists has highlighted that many concerns about retraumatization in research are not well supported. Nevertheless, because this scholarship (1) is from outside of political science and (2) has largely been conducted with participants not experiencing extreme need or ongoing suffering, and living in geopolitically stable environments, this paper carefully evaluates the portability of the optimistic conclusions. It does so by considering what political scientists have written about trauma in the course of research (even if the research was not targeting trauma as such) and what theorists have written about the ethics of risk-benefit tradeoffs for research participants.

What this critical literature suggests is that even if retraumatization as such is not a well-validated concept, the trauma of research participants should be a significant concern in the research process. Scholarship by Green and Cohen (Reference Green and Cohen2021); Gordon (Reference Gordon2021); Roll and Swenson (Reference Roll and Swenson2019); and Fujii (Reference Fujii2012) among others indicates that researchers should do no harm and offer benefits to participants because those are the right things to do – but also because failing to account for participant distress can produce significant biases in data. Separate from the narrow concern about retraumatization, these concerns about participant wellbeing and measurement accuracy provide strong grounds for motivating greater attention to trauma in the research process.

Defining Retraumatization

One of the challenges in talking about ‘retraumatization’ is that the term lacks (1) a consistent definition and (2) clinical and construct validity for any proposed definitions (Follette and Duckworth Reference Follette, Duckworth, Duckworth and Follette2012; Batten and Naifeh Reference Batten, Naifeh, Duckworth and Follette2012). The text revision of the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) – the key reference guide for physicians, psychologists, social workers, and others in identifying and treating mental health issues – does not mention ‘retraumatization’. The touchstone trauma diagnosis in the DSM-V is Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Scholars sometimes mention PTSD in relation to retraumatization as either a risk factor or a similar condition (Becker-Blease and Freyd Reference Becker-Blease and Freyd2006; Ullman Reference Ullman2007; Newman et al. Reference Newman, Walker and Gefland1999; Johnson and Benight Reference Johnson and Benight2003). Batten and Naifeh (Reference Batten, Naifeh, Duckworth and Follette2012) relate retraumatization to complex PTSD, a diagnosis that is not recognized by the DSM-V but has been proposed as a diagnosis to capture severe, refractory, or exacerbated PTSD. The DSM-V defines PTSD in relation to the happening ‘actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence’ (American Psychiatric Association 2013, 271). Some scholars say, in order for retraumatization to occur, that an event that could have also produced PTSD must have occurred in the past (Follette and Duckworth Reference Follette, Duckworth, Duckworth and Follette2012).

The political science literature has used a definition of retraumatization as ‘reactivation’ of traumatic stress as a result of retelling or emotionally engaging with a narrative of past trauma (see Leshner and Foy Reference Leshner, Kelly, Schutz, Foy and Figley2012 in Pearlman 2022). Past trauma, per this definition, is understood broadly; for example, people can be traumatized either from witnessing, enacting, or experiencing violence. (Note, however, that retraumatization here is distinct from revictimization – that is, when victims of a traumatic event experience the actual event again.) Follette and Duckworth (Reference Follette, Duckworth, Duckworth and Follette2012), in their book on retraumatization, which is also the only scholarly book on retraumatization exclusively, define it as ‘traumatic stress reactions, responses, and symptoms that occur consequent to multiple exposures to traumatic events that are physical, psychological, or both in nature’ (p. 2). They indicate that traumatic events can include assault, abuse, accidents, violence enactment, or exposure. They specify that they do not use the term ‘to capture distress that occurs with the retelling of a trauma narrative’ (p. 2) – that is, the reactivation process to which Leshner and Foy allude.

Newman et al. (Reference Newman, Kaloupek, Keane, Folstein, Kaufman Kantor and Jasinski1997), in an examination of the ethics of trauma research, warn against the tendency to equate ‘talking about trauma’ with ‘trauma’: ‘It is essentially a distinction between distress that emanates from recall and, for example, the ‘intense fear, helplessness, or horror’ (American Psychiatric Association, 1994, 424) that emanates from direct experience. Failure to maintain this distinction undermines all efforts to understand the risks and benefits of such research’ (274). Moreover, past traumatic experiences and/or questions about traumatic experiences are not necessary for participants to feel emotions consistent with traumatic distress or retraumatization. Research suggests that participants in any project can become distressed as a result of, for example, talking about their health status or thinking about the security of their participant data (Legerski and Bunnell Reference Legerski and Bunnell2010). Cromer et al. (Reference Cromer, Freyd, Binder, DePrince and Becker-Blease2006) found that college students report similar levels of distress whether talking about emotional and sexual abuse or other sensitive topics such as grades and body image.Footnote 1 Such work implies that if retraumatization were a cause for concern in research, the concern would not be limited to trauma- or violence-specific research.

This paper attends to the full range of concerns about retraumatization that the literature has identified. That is, I try to address retraumatization in the sense of reactivation, regardless of the precipitating factor. I also, however, draw on the literature about distress, upset, and other sequelae of talking about trauma in the research context – whether or not this literature refers explicitly to retraumatization – because talking about trauma is thought to be the primary potential driver of retraumatization and some sequelae of talking about trauma are indistinguishable from some definitions of retraumatization.

Does Research Retraumatize People?

Social scientists have long wondered the extent to which their research can hurt participants. This section of the paper traces scholarship on traumatic distress and what has come to be called retraumatization in research. The section first details the methods used to review relevant scholarship (see “Scoping Review Methods”). It takes up early psychology studies of participant reactions to trauma questionnaires – the ‘trauma meta-research’ programme (see “Insights from Clinical Psychology and Related Fields”) – then considers research participant retraumatization in political science (see “Challenges for Political Science”).

Scoping Review Methods

The literature on trauma as an outcome of the research process is large. Section “Does Research Retraumatize People?” of the paper provides a representative overview of the empirical treatments of retraumatization and related concepts, with a discussion tailored to the contexts and concerns of political science. I use a scoping review method to provide this overview rather than a systematic review or some other meta-analytic method for two related reasons. First, scoping reviews are appropriate when studying topics for which ‘universal study definition or definitive procedure has not been established’ (Pham et al. Reference Pham, Rajić, Greig, Sargeant, Papadopoulos and McEwen2014, 371). As a I discuss in more detail in Section “Defining Retraumatization”, the term ‘retraumatization’ is less a well-validated clinical concept than a byword for concern about asking about trauma (Batten and Naifeh Reference Batten, Naifeh, Duckworth and Follette2012). Second, although I could build a meta-analysis around studies that used a narrow definition of retraumatization (as one group of scholars essentially has, see Jaffe et al. Reference Jaffe, DiLillo, Hoffman, Haikalis and Dykstra2015), in doing so I might exclude concerns that political scientists might be thinking of when they use the word ‘retraumatization’. As Nickerson et al. (Reference Nickerson, Platas, Robinson, Samii and Sinmazdemir2019) note, political science ethics guidelines have left definitions of trauma-related concepts open to interpretation, so different political scientists might understand retraumatization very differently from each other – and from clinical psychologists.

This scoping review has a two-pronged approach. The first prong takes advantage of the trauma meta-research programme in clinical psychology and related fields (see Section “Insights from Clinical Psychology and Related Fields”). That is, I try to glean insights from several decades of studies that have had, as their primary outcomes, participant reactions to the research itself. The second prong investigates work by political scientists who may not have been trying to do meta-research as such but recorded key insights about the reactions of their participants to political science research specifically (Section “Challenges for Political Science”). This prong crucially complements the first prong by allowing me to see whether the findings of clinical psychology meta-research hold up outside of clinical psychology settings.

The research articles that I ultimately cite for the first prong of my scoping review all ask some form of the question ‘what negative reactions do participants have in the course of trauma-related research?’ (see Appendix F for additional details about the literature search and article selection criteria). But they vary on dimensions including exact design, type of trauma-related exposure, precise definition of trauma/distress, and participant population. As noted above, given the importance of the question that these studies target (protecting research participants from harm) and the different ways of defining harms related to retraumatization, I did not want to risk drawing conclusions that were conditional on highly specific research designs or definitions.Footnote 2 The review tries to exploit the relative diversity of articles – which have all been selected to be high-quality, regardless of experimental or non-experimental design – to evaluate whether the results in this section point in the same direction even while varying on some dimensions. For example, my scoping review includes both quantitative and qualitative research designs (see for respective examples Decker et al. Reference Decker, Naugle, Carter-Visscher, Bell and Seifert2011; Hamberger et al. Reference Hamberger, Larsen and Ambuel2020). If the results of both types of studies point in the same direction, this allows me to say that any conclusion is robust to the exact type of data collection.Footnote 3 Then, because the articles in the first prong still only have relative diversity (all being in the general mode of clinical psychology), I can further evaluate the applicability and robustness of the results when I introduce the second prong of the scoping review related to research in political science research specifically.

Insights from Clinical Psychology and Related Fields

Clinical psychologists, psychiatrists, and a subset of scholars in related fields like sociology have conducted many studies that query research participants’ retraumatization or experiences of distress when being asked about trauma. (This type of scholarship on the nature or experience of research itself is often called ‘meta-research’.) Most of these studies are observational (exceptions exist, for example, Ferrier-Auerbach et al. Reference Ferrier-Auerbach, Erbes and Polusny2009; Paing et al. Reference Paing, O’Keefe, McMurtrie and Williams2023) and conducted in university laboratory settings (for example, Lawyer et al. Reference Lawyer, Holcomb and Přhodová2021; Johnson and Benight Reference Johnson and Benight2003; Decker et al. Reference Decker, Naugle, Carter-Visscher, Bell and Seifert2011) or medical clinics (for example, Newman et al. Reference Newman, Walker and Gefland1999), though some research has involved an in-home component (for example, Murdoch et al. Reference Murdoch, Kehle-Forbes and Partin2017). That is, most of the psychology research detailed in this subsection was conducted in structured institutional settings with onsite research team monitoring. They also have all been conducted in the USA or other industrialized, rich nations in the Global North. And, participants in these studies are relatively sheltered from active geopolitical conflict. The types of traumatic events experienced by participants in these studies were mostly personal as opposed to geopolitical (for example, child abuse or domestic violence rather than war), although some scholarship has focused on the experiences of veterans (Murdoch et al. Reference Murdoch, Kehle-Forbes and Partin2017). Most participants were not experiencing traumatic events during the study periods, though many participants were experiencing ongoing traumatic stress and receiving psychological treatment related to their past traumas.

Most of the studies discussed here involve questionnaires and/or interviews (Murdoch et al. Reference Murdoch, Kehle-Forbes and Partin2017; Decker et al. Reference Decker, Naugle, Carter-Visscher, Bell and Seifert2011; Newman et al. Reference Newman, Walker and Gefland1999). The independent variable under consideration is usually being asked about a sensitive topic (notably, although scholars have written about other presumed moderators or causes of distress or retraumatization in research, such as power differentials – see Poopuu Reference Poopuu2020, for an overview – the focus of the trauma meta-research literature in clinical psychology and related fields has been either the asking of sensitive questions or the bundled treatment of participating in research). Researchers assessed participants for their experiences of retraumatization or other negative reactions by asking participants directly about their experience of the research process, often taking advantage of standard instruments like the Reactions to Research Participation Questionnaire (Newman et al. Reference Newman, Willard, Sinclair and Kaloupek2001).Footnote 4 This type of outcome measurement has both advantages and disadvantages. An advantage is that – given the subjective nature of psychology – negative/positive emotions are defined by reference to whether the participant experiences them as negative or positive. Prioritizing self-reports of distress or pleasure on the part of the participant is, ideally, a way to prioritize the participant’s autonomy and agency in narrating their experiences.Footnote 5 One disadvantage is that if participants are not comfortable with research, they may not respond honestly to questions about their experiences with research. Another disadvantage is that the standard direct, self-report questions about feeling traumatized do not measure physical symptoms.

One of the most-cited empirical treatments of the question of trauma research was performed in the 1990s with a sample of survivors of childhood sexual abuse recruited in a hospital setting (Newman et al. Reference Newman, Walker and Gefland1999). Newman et al. aimed to investigate both retraumatization – in their words, ‘whether the process of investigation elicits potentially disabling memories of painful experiences to which subjects have already adapted’ (Newman et al. Reference Newman, Walker and Gefland1999, 187) – and, if distress occurred, how patients could recover from it during interviews or questionnaire completion. They asked, at various points in the survey process (spaced out over the course of days), for participants to respond via the Likert scale to three statements (table A1). Newman et al. (Reference Newman, Walker and Gefland1999) found considerable approval for the research. Only 5% reported regret and 10.5% reported unexpected ‘upset’. A substantial proportion also reported benefits. Those who did experience upset had higher rates of preexisting PTSD.

Several subsequent studies have similarly considered the impact of research asking women about past experiences of abuse. Disch (Reference Disch2001) studied women who survived abuse at the hands of professionals, finding greater rates of distress (80%) than Newman et al. (Reference Newman, Walker and Gefland1999) but also very high rates of perceived benefit (96%). Disch (Reference Disch2001) presents evidence that participants use the distress in service of healing and states that the findings ultimately support those of Newman et al. (Reference Newman, Walker and Gefland1999). A few years later, Johnson and Benight (Reference Johnson and Benight2003) asked questions about experiences of domestic violence to fifty-five women, then evaluated them with three items similar to those of Newman et al. (Reference Newman, Walker and Gefland1999). Forty-five per cent of women reported benefit, 25% reported unexpected upset (a group with higher rates of PTSD, depression, and lifetime trauma), and 6% reported regret in participating (Johnson and Benight Reference Johnson and Benight2003).

Other studies have looked at heterogeneous experiences of research on sensitive topics by prior child abuse victimizations. Using a within-subjects design and a sample of female college students, Savell et al. (Reference Savell, Kinder and Young2006) looked at whether nonabused participants exhibited greater increases in state distress than abused participants after answering explicit questions about sex and experiences of sex abuse. Thirteen out of 207 participants became meaningfully distressed in the course of the research, but they were distributed across groups of participants (see Savell et al. Reference Savell, Kinder and Young2006, 169; also note the authors define ‘distress’ as an upward shift of more than ten points on a hundred-point state anxiety scale). Rojas and Kinder (Reference Rojas and Kinder2007) replicated Savell et al. (Reference Savell, Kinder and Young2006) with a larger sample that included men as well as women and found similar results. In a qualitative study with multiple sessions, Decker et al. (Reference Decker, Naugle, Carter-Visscher, Bell and Seifert2011) administered questionnaires and performed about past experiences of victimization and current personal data (including sexual behaviour) and exposed participants to emotional stimuli (photographs and sounds) to undergraduate women (thirty-six of whom had experienced maltreatment and forty-three of whom had experienced not), and evaluated their reactions, over three sessions. Most of the participants experienced ‘bother’ at some point during the research process, with most of the bother arising from the auditory and visual stimuli; most also reported benefit. Nevertheless, ‘[n]early three-quarters’ of research participants reported that they were mostly unbothered during the study (Decker et al. Reference Decker, Naugle, Carter-Visscher, Bell and Seifert2011, 59). Differences between the experiences of women with and without child abuse history were generally not statistically significant from session to session.

Murdoch et al. (Reference Murdoch, Kehle-Forbes and Partin2017) looked at the retraumatization potential of large-scale, quantitative trauma research featuring mailed questionnaires. They used two samples of veterans who had applied for PTSD benefits. Less than half of respondents reported increased sadness or tenseness post-survey – and evidence suggested that some of the measured sadness would have emerged regardless of research. For example, female respondents with a history of military sexual assault were likelier than others to exhibit negative affect changes after completing a survey that did not ask about sexual assault. The authors conclude, ‘While a substantial minority of [v]eterans reported more sadness or tenseness post-survey, the net change in affect was small. Most hypothesized risk factors were actually associated with higher baseline sadness or tenseness scores’ (Murdoch et al. Reference Murdoch, Kehle-Forbes and Partin2017, 1 – see also for a similar insight, Rosenbaum and Langhinrichsen-Rohling Reference Rosenbaum and Langhinrichsen-Rohling2006). They also note a possibility that survey recipients who select out of responding are engaging in self-protective behaviours, and note that ‘separate protections for [v]eterans with the risk factors studied here do not seem necessary’ (Murdoch et al. Reference Murdoch, Kehle-Forbes and Partin2017, 1). This is consistent with other research finding that external risk factors need not automatically disqualify potential participants in trauma research (see Grubaugh et al. Reference Grubaugh, Tuerk, Egede and Frueh2012; Carlson et al. Reference Carlson, Newman, Daniels, Armstrong, Roth and Loewenstein2003).

The aforementioned studies have looked at samples at least partially recruited for having experienced a specific trauma. Labott and Feeny (Reference Labott, Johnson, Fendrich and Feeny2013), by contrast, created a random sample of respondents. The project screened out anyone with PTSD, recent loss, current depression, or risk of suicide, and asked the remaining 395 participants a battery of items to elicit traumatic experiences specific to them and manipulate mood negatively. Most participants across two follow-ups reported that the research experience was positive. Only 30% of participants requested resources. Those who did requested the resources because they wanted to address the underlying trauma, not because they were distressed by the survey (this is a significant theme in the trauma meta-research literature – that preexisting traumatic stress symptoms can emerge at any time, which may be independent of but happen to coincide with research – see Batten and Naifeh Reference Batten, Naifeh, Duckworth and Follette2012). Labott and Johnson (Reference Labott and Johnson2004) conclude, ‘interviews on distressing topics can result in negative moods and stress, but they do not harm respondents’ (p. 33).

Two sets of scholars have also conducted meta-studies of the retraumatization literature in clinical psychology and related fields: Jorm et al. (Reference Jorm, Kelly and Morgan2007) and Jaffe et al. (Reference Jaffe, DiLillo, Hoffman, Haikalis and Dykstra2015). The Jorm et al. review, while not concerned with retraumatization as such, includes forty-six studies targeting participants’ experience of psychiatric research, half of which were trauma studies. They found a greater prevalence of distress across studies and greater rates of benefit among the trauma research participants than among the non-trauma participants, suggesting that short-term trauma research is emotionally more intense than other research (Jorm et al. Reference Jorm, Kelly and Morgan2007). The only study to find close to a 50% rate of participant distress was one that included neurological laboratory procedures as well as a questionnaire or an interview. Perceptions of benefit (high across studies, see Jorm et al. Reference Jorm, Kelly and Morgan2007, 921–922) could co-occur with distress. Although Jorm et al. (Reference Jorm, Kelly and Morgan2007) only look at psychiatry research, much political science research is comparable in format to the survey, interview-based, experimental, and quasi-experimental research considered by Jorm et al. (Reference Jorm, Kelly and Morgan2007).

Jaffe et al. (Reference Jaffe, DiLillo, Hoffman, Haikalis and Dykstra2015), a statistical meta-analysis with seventy separate samples, produces similar findings to those suggested by Jorm et al.’s Reference Jorm, Kelly and Morgan2007, systematic review. Victims of trauma were minimally but statistically significantly likelier to experience distress during research, an effect heightened for patients with diagnosed PTSD. Average rates of benefit were moderate to high and, as in Jorm et al. (Reference Jorm, Kelly and Morgan2007), not precluded by short-term distress. Participants who had experienced sexual trauma felt slightly better than participants who had non-sexual traumas. The review also finds no evidence of participant regret or resentment toward research participation. The authors conclude: ‘Together, these findings indicate that individuals generally tolerate participation well and do not feel “retraumatized” by their involvement in trauma research’ (Jaffe et al. Reference Jaffe, DiLillo, Hoffman, Haikalis and Dykstra2015, 52).

Notwithstanding their positive conclusions, Jaffe et al. (Reference Jaffe, DiLillo, Hoffman, Haikalis and Dykstra2015) note that the literature on retraumatization is ‘nascent’ (p. 54). They especially identify a need for experimental studies and studies that assess participant reactions on an ongoing basis. Work by Paing et al. (Reference Paing, O’Keefe, McMurtrie and Williams2023) addresses the former need. Paing et al. (Reference Paing, O’Keefe, McMurtrie and Williams2023) studied whether participants who were randomly assigned to complete a trauma survey experienced greater state distress or remembering of traumatic events than the participants who had not done the survey. They found that participants in the treatment did not report meaningfully more state distress, but did agree more with the statement ‘The research made me think about things I didn’t want to think about’ (Paing et al. Reference Paing, O’Keefe, McMurtrie and Williams2023, 18). These results are interesting in light of the definition of retraumatization as the reactivation of traumatic stress as a result of engaging with a narrative of past trauma (see the discussion of Leshner et al. Reference Leshner, Kelly, Schutz, Foy and Figley2012 in “Defining Retraumatization”). What Paing et al. (Reference Paing, O’Keefe, McMurtrie and Williams2023) seem to have found is that research participants can engage with memories of past trauma (with which they do not want to engage) without reactivating traumatic stress.

Other work has tried to fill the second gap identified by Jaffe et al. (Reference Jaffe, DiLillo, Hoffman, Haikalis and Dykstra2015) – the lack of scholarship with multiple follow-ups. Lawyer et al. (Reference Lawyer, Holcomb and Přhodová2021) exposed a group of female rape survivors (

![]() $N = 62$

) and a control group of women who had not experienced a rape (

$N = 62$

) and a control group of women who had not experienced a rape (

![]() $N = 79$

) to an audio recording of a sexual assault, then measured their psychological reactions both immediately after and 3–8 weeks after the initial study. In line with prior research (for example, Decker et al. Reference Decker, Naugle, Carter-Visscher, Bell and Seifert2011; Lawyer et al. Reference Lawyer, Holcomb and Přhodová2021) found that rape survivors reported more intense personal reactions and perceived participation as being more beneficial than controls. These results held for both waves of the study. Large majorities of study participants (93.6% in the first wave and 87.2% in the second wave) responded positively to the question ‘Had I known in advance what participating would be like I still would have agreed to participate’ (Lawyer et al. Reference Lawyer, Holcomb and Přhodová2021, 317). These results imply that the kind of clinical psychology research that is low-risk and beneficial in the short term will also be low-risk and beneficial in the long term.

$N = 79$

) to an audio recording of a sexual assault, then measured their psychological reactions both immediately after and 3–8 weeks after the initial study. In line with prior research (for example, Decker et al. Reference Decker, Naugle, Carter-Visscher, Bell and Seifert2011; Lawyer et al. Reference Lawyer, Holcomb and Přhodová2021) found that rape survivors reported more intense personal reactions and perceived participation as being more beneficial than controls. These results held for both waves of the study. Large majorities of study participants (93.6% in the first wave and 87.2% in the second wave) responded positively to the question ‘Had I known in advance what participating would be like I still would have agreed to participate’ (Lawyer et al. Reference Lawyer, Holcomb and Přhodová2021, 317). These results imply that the kind of clinical psychology research that is low-risk and beneficial in the short term will also be low-risk and beneficial in the long term.

In aggregating the conclusions of studies that feature different methods and exact types of participant reactions to research, I am relying on the methods that I used to put together this scoping review ensuring that the studies are sufficiently comparable in that they study the costs and benefits of research in terms of retraumatization and related issues like traumatic stress (see Section “Scoping Review Methods” and Appendix F). With these caveats, it seems fair to say that findings from clinical psychology and related fields suggest that the risk of retraumatization and distress from trauma-related research is low, while the perceived benefits of the research for participants are relatively high. Nevertheless, the researchers interested in relying on these findings should note that they were mostly produced in a very particular type of setting with a particular type of research participant – generally, university laboratories in the Global North with research participants who were not currently experiencing major traumatic events. In the following subsection, I discuss what these scope conditions might mean for political scientists.

Challenges for Political Science

The modal research participant in studies from the preceding Section is not actively experiencing traumatic events and is likely to receive benefits from research that are personal and psychological in nature (for example, catharsis). Yet much political science research takes place in contexts with ongoing, widespread suffering, instability, lack of services, and/or significant surveillance and repression. All of these contextual characteristics can make the job of the researcher more difficult and make for participants who are more on edge. In this subsection, I focus especially on those characteristics that are theoretically related to retraumatization, in particular the presence of ongoing suffering and extreme need.Footnote 6

Members of these communities with ongoing suffering and instability may not be receiving sufficient psychosocial support, may be prone to have higher hopes for research, may be likelier to feel like they are at a disadvantaged end of a power differential with the researcher, and may also be burnt out from interviews by other researchers, aid organizations, or journalists. For example, participants in political violence research may hope that the research will draw attention to a conflict or crisis and lead to the end of the conflict or crisis (for example, Foster and Minwalla Reference Foster and Minwalla2018; Robins Reference Robins2010; Wood Reference Wood, Mazurana, Jacobsen and Gale2013; Aroussi Reference Aroussi2020, see also Appendix C). Disappointment at not seeing an end of a conflict or at not having needs met – yet again – can in theory manifest as retraumatization.

All of these challenges can be exacerbated by the sense of an extreme power differential – beyond the usually inequitable power dynamic of research (see, for a general discussion, Ben-Ari and Enosh Reference Ben-Ari and Enosh2013) – in which the researcher but not the participant has access to resources and can leave a site of conflict or unhappiness (Hedström Reference Hedström2019; Jok Reference Jok, Mazurana, Jacobsen and Andrews Gale2013, see also Foster and Minwalla Reference Foster and Minwalla2018 on the journalist/interviewee power differential), not to mention extract career benefits from the knowledge obtained onsite. The power differential can affect research participants’ experience and possible risk of retraumatization or distress in two ways. First, research participants who experience a power differential in which they are disadvantaged are likely to feel less able to opt out of research – they may not feel able to refuse consent or shape the flow of a research interaction (Gordon Reference Gordon2021), which may mean that they become exposed to a part of research that they find traumatizing or otherwise upsetting. Second, research participants who sense a power differential in research may experience the power differential as inherently upsetting or retraumatizing (this is discussed by Castor-Lewis Reference Castor-Lewis1988, see also Aroussi Reference Aroussi2020 who attributes the success of her research vis-à-vis this concern to trying to level the power differential).

Given the challenges faced by their participants, political scientists have asked how well clinical psychology findings from the preceding section (“Insights from Clinical Psychology and Related Fields”) translate to their research. I take up the challenges of retraumatization risks in the presence of ongoing suffering and extreme need here in turn. Studying people with ongoing suffering raises two questions related to retraumatization: first, are these participants more traumatically affected by the research than other participants? Second, even if any traumatic feelings are minimal and no greater than those experienced by other participants, is it right to add to the burden of people who are already suffering? Empirical research can shed little light on the second question, which is deeply normative. It can, however, inform answers to the first.

Few scholars have conducted the type of studies described in Section “Insights from Clinical Psychology and Related Fields”, which directly target the question of research participant distress and traumatization, in conflict zones or other settings of ongoing suffering. The part of clinical psychology research with the most to say about this topic might be studies on the research participation experience of women actively experiencing domestic violence. Hamberger et al. (Reference Hamberger, Larsen and Ambuel2020), for example, conducted a year-and-a-half-long qualitative study of women experiencing intimate partner violence. They aimed to study the safety risks of participating while suffering abuse, any changes the participation experience inspired in participants, and the participants’ recommendations for researchers (Hamberger et al. Reference Hamberger, Larsen and Ambuel2020). Notably, several volunteers hesitated to join the study – fearing their own retraumatization, in so many words – but did not end up experiencing retraumatization.Footnote 7 Most described the experience as positive (Hamberger et al. Reference Hamberger, Larsen and Ambuel2020; see also participant quotations in Table A2). We might see this as the best-case scenario for research on participants with ongoing suffering: when sufficient resources are accessible (for example, domestic violence shelters, counsellors, interviewers with a high degree of clinical training) and participants live in a politically stable environment, research can be non-(re)traumatizing and positive even for participants currently experiencing violence.

It is possible to provide an acceptable research environment even in what Gordon (Reference Gordon2021) calls ‘conflict-affected environments’. But it may be more difficult than the challenge faced by Hamberger et al. (Reference Hamberger, Larsen and Ambuel2020), who had participants with ongoing suffering but less extreme need. Availability of resources (in the community or provided by the researcher) and interviewer/enumerator sensitivity seem to significantly moderate the extent of distress experienced by participants (Gordon Reference Gordon2021; Kamel Reference Kamel2017). Nevertheless, conflict researchers have narrated many cases of frustration or distress on the part of people being interviewed during conflicts or other traumatic events (whether by researchers or journalists, see Gordon Reference Gordon2021; Foster and Minwalla Reference Foster and Minwalla2018). The frustration or distress may be especially acute among participants who have been repeatedly interviewed or subject to frequent questionnaires as part of receiving aid (Jok Reference Jok, Mazurana, Jacobsen and Andrews Gale2013; Jok Reference Jok1996). Scholars frequently discontinue interactions in which participants become distressed, but Hedström (Reference Hedström2019) notes a concern that unilaterally stopping an interview can itself be distressing and disempowering, particularly if participants interpret the stop as a sign that their reactions are ‘not normal’ (Hedström describes terminating an interview when participant ‘breaks down, hitting her head with her hands, saying she wants it empty’, pp. 672–673). Another approach is suggested by Revkin and Wood (Reference Revkin and Wood2021) – not necessarily stopping data collection in the middle of an interaction, but discontinuing future human data collection.

Political scientists working in conflict zones have also shared many insights about the problem of what they can give to research participants who need and hope for so much (Gordon Reference Gordon2021) – what I refer to as the challenge of research in the presence of extreme need. Honesty on the part of researchers is crucial to avoid raising the hopes of participants who are suffering from conditions that may be slow to improve. Wood notes that she was explicit in telling participants in her qualitative research on the El Salvadoran civil war that the only benefit of the research was the account that she was producing (Wood Reference Wood2006).Footnote 8

Other scholars evaluating the impacts of their longitudinal qualitative work in vulnerable contexts (even if they are not necessarily doing trauma meta-research as such) report similar concerns and practices around reciprocity and trying to provide benefits to respondents (for example, Fujii Reference Fujii2012; Robins Reference Robins2010; Stanley Reference Stanley, Gadd, Karstedt, Messner and Stanley2011; Aroussi Reference Aroussi2020). Aroussi (Reference Aroussi2020) notes difficulties related to financial boons. Many survivors of wartime sexual violence are extremely low-income, and financial incentives to participate in research can feel exploitative or coercive in a way that, according to some scholarship (for example, Aroussi Reference Aroussi2020), can increase the risk of retraumatization. Aroussi, in qualitative work with survivors of sexual violence in Eastern Congo, declared repeatedly, at the time of recruitment and on the day of participation, that respondents would not receive money other than compensation for costs incurred by participating (Aroussi Reference Aroussi2020). Even with these reminders, many participants still expected additional benefits from participation – a testament to the desperation and expectations that political scientists must sensitively manage. (Quotations from some of Aroussi’s (Reference Aroussi2020) participants are highlighted in Table A2.)

Working Conclusions

The working conclusion for political scientists working with participants who are experiencing ongoing suffering or who have extreme needs is that distress is not an inevitable consequence of the research process. Research design choices having to do with researcher honesty, expectation management, and informed consent can mitigate many risks. Even so, several limitations and areas for future research exist. First, the researchers cited here had significant control over data production, so could directly ensure ethical practices. In some cases in political science, researchers may have less direct control over data production and collection. For example, they may use preexisting administrative sources or collaborate with community partners or non-governmental organizations to administer an intervention. (See also discussion of ‘desk research’ in Section “Trauma-Informed Political Science Data Collection”) Second, there is a lack of randomized experimental research on trauma during the research process. Jorm et al. (Reference Jorm, Kelly and Morgan2007) and Jaffe et al. (Reference Jaffe, DiLillo, Hoffman, Haikalis and Dykstra2015) note that few studies on whether research participants experience distress as an outcome of research have control groups.Footnote 9

Is It Wrong to Ask People about Trauma?

The empirical literature tells us a great deal about risks such as retraumatization (and benefits such as catharsis) in trauma-related research or research on sensitive topics. It does not tell us, however, whether to accept a given risk or what we should actually, ethically provide to our research participants. This section of the paper explores theoretical resources for normatively evaluating what we know about the risks and benefits of trauma-related research and research on sensitive topics.

Standard modern research ethics is usually described as a mix of consequentialism and, to a lesser extent, deontology (Kitchener and Kitchener Reference Kitchener and Kitchener2009). Where deontology would have to evaluate the goodness of an act by reference to rules and principles, consequentialism would have us look to the consequences of an act in deciding whether it is ethical. Concerns about retraumatization generally emerge in the course of consequentialist risk-benefit analyses of research.

The role of consequentialism in guiding research ethics is, in many countries, legally regulated. In the USA, the Common Rule tasks institutional review boards with ensuring not only that risk be ‘minimized’ but that ‘[r]isks to subjects are reasonable in relation to anticipated benefits, if any, to subjects, and the importance of the knowledge that may reasonably be expected to result’ (45 CFR 46, subpart a). The question for many critical research ethicists is whether the consequentialist logic of the Common Rule’s risk-benefit tradeoff is enough to protect participants, or whether it needs supplementing.

Many of the scholars discussed in this section of the paper are also sceptical of empirical research. As I discuss in the subsection “Insights from Feminist Ethics”, many feminist scholars do not necessarily reject any possibility of doing empirical research on sensitive topics but doubt that empirical meta-research – that is, research on the research experience itself – has sufficiently explored the ways in which research on sensitive topics might be problematic. However, unlike the scholars discussed in the preceding section, “Does Research Retraumatize People?”, the scholars that I discuss in this section of the paper are not critiquing the empirical literature because of per se empirical objections. Instead, they are critiquing the literature on the basis of prior theoretical and normative commitments.

Insights from Feminist Ethics

Feminist research and feminist ethics broadly prioritize ‘empowerment, reflexivity, and reciprocity’ (Kingston Reference Kingston2020, 532). Many scholars identify specific responsibilities of researchers to empower and enrich participants and advance the wellbeing of marginalized groups – above and beyond minimizing risk relative to benefit (Kingston Reference Kingston2020). Moreover, perhaps because feminist ethics orients researchers toward thinking about intangible or decommodified features of the participants – in the words of Ackerly and True (Reference Ackerly and True2008), their ‘subjectivity’ (p. 695) – feminist researchers have tended to doubt that subjective experiences like trauma can be adequately identified in research, let alone counterbalanced.

For example, theorists have criticized efforts by Newman et al. (Reference Newman, Kaloupek, Keane, Folstein, Kaufman Kantor and Jasinski1997) and other empiricists to evaluate the challenges of trauma and trauma research ‘rationally’. Hlavka et al. (Reference Hlavka, Kruttschnitt and Carbone-López2007) reject what they call Newman et al.’s ‘notion of objectivity and [belief in] the existence of an emotionless reality’ that can be detected through standardized questions (Hlavka et al. Reference Hlavka, Kruttschnitt and Carbone-López2007, 895). Scholars, such as Campbell and Adams (Reference Campbell and Adams2009) have also commented on the limited scope of the trauma meta-research programme. Fontes (Reference Fontes2004) writes, ‘[I]t appears that even the trauma-focused interviews [described in Newman et al. Reference Newman, Walker and Gefland1999] were of short duration and medically focused, which may have led to fewer disclosures and therefore less sensitive discussions’ (Fontes Reference Fontes2004, 166). Fontes further argues that ‘stirring up more memories of trauma’ has ‘potentially pernicious effects’ that are perhaps not yet understood (Fontes Reference Fontes2004, 166).

Feminist concerns about trauma and violence research (Newman et al. Reference Newman, Kaloupek, Keane, Folstein, Kaufman Kantor and Jasinski1997; Hlavka et al. Reference Hlavka, Kruttschnitt and Carbone-López2007; see Edwards and Mauthner Reference Edwards and Mauthner2002 on feminist critiques of research ethics more broadly) extend beyond even the concerns about distress mentioned already. Fontes (Reference Fontes2004),Footnote 10 for example, writes about the power dynamics of the research process as it relates to informed consent, observing some women and girls who have been victims of violence may not be equipped to give informed consent (an idea also suggested by Campbell and Adams Reference Campbell and Adams2009). Such objections recall a much-cited paper by Castor-Lewis (Reference Castor-Lewis1988), which argues that questionnaire-based research can substantively recreate the experience of trauma – specifically incest – by creating a power dynamic in which a researcher is ‘on top’ (74). Castor-Lewis points out that the harm of the power differential is ‘proportionate to the amount of ‘power’ societally granted to the investigator (for example, if white, heterosexual, male) and denied to the participant (for example, non-white, female, lesbian, ‘nonprofessional’)’ (74).Footnote 11

Insights from Postcolonial Theory

As discussed in the section, “Challenges for Political Science”, much political science involves researchers from institutions in the Global North coming to study the Global South, particularly parts of the Global South experiencing political violence. These researchers may bring with them practices, norms, or ideas that are unfamiliar or inappropriate in local contexts (Pain Reference Pain2021; Nguyen Reference Nguyen2011; Jayawickrama Reference Jayawickrama2014; Haas Reference Haas2012). This element of the trauma-related research environment is what has concerned many theorists working in postcolonial and related traditions.

Postcolonial theorists and other scholars that critically conceptualize research in the Global South have especially drawn attention to the possibility that human subjects’ research on sensitive topics could retraumatize or upset participants by denying them the option of practising avoidance. That is, once a sensitive topic that might trigger traumatic feelings is mentioned, that topic can no longer be avoided. Avoidance entails not emotionally engaging with a memory of a traumatic past event (Rosenbaum and Langhinrichsen-Rohling Reference Rosenbaum and Langhinrichsen-Rohling2006). People might seek avoidance either because they lack the resources (communal, medical, institutional, personal) that enable successful coping (Gordon Reference Gordon2021) or because avoidance is a culturally conditioned emotional strategy (Robins and Wilson Reference Robins and Wilson2015). Robins and Wilson suggest that expectations of positive catharsis informed by Western counselling approaches are inappropriate or inapplicable in much of the world (cf. Hedström Reference Hedström2019, on informed consent).

Nguyen (Reference Nguyen2011) argues that not only is Western professionals’ treatment of non-Western trauma victims retraumatizing, the West’s entire conception of trauma is retraumatization. The very fixation on trauma as a subject of research and humanitarian endeavour is voyeuristic, and so innately problematic (Nguyen Reference Nguyen2011). Worse still, the positivism of the trauma ‘industry’ compels the traumatized subject to fit a prior definition of trauma to receive sympathy and treatment (Nguyen Reference Nguyen2011, 29). The author, drawing on work with former Abu Ghraib detainees, observes that asking about trauma can be retraumatizing, not because thinking about trauma is traumatizing but because the asking or the manner of the asking is bizarre or insulting (‘the psychic injuries of Muslim men who had been forced to pray naked or whose genitals had been stepped on were “verified” by their scores on test items such as, Over the past 7 days, how much were you distressed by feeling inferior to others?’ (Nguyen Reference Nguyen2011, 34). The case of the questioning of the Abu Ghraib detainees seems like an example of a case in which the intentionality of the questioning (in this case, to verify a clinical finding) had far-reaching implications for the prisoners’ experience. (We should, nevertheless, note that prisoners’ voices are absent in this account and that the setting was clinical rather than research-oriented.)

Critiques of Legalistic Research Ethics

Although feminist and postcolonial schools of thought have provided significant theoretical resources for assessing the ethics of asking about trauma, even they do not represent the universe of alternatives to Common Rule consequentialism. In this section, I discuss normative perspectives that proceed from a kind of immanent critique of trauma research as practised under laws like the Common Rule.

One immanent critique – given in Affleck (Reference Affleck2017) – assesses the role of cost-benefit analysis in trauma research. Citing 35 studies (including many of those discussed in Section “Does Research Retraumatize People?”), Affleck suggests that Common Rule-Style cost-benefit analysis is inappropriate for non-clinical trauma research: ‘The benefits cited by participants in trauma-focused research do not hold the moral weight to offset risk’ (385). The problem is that social science research lacks the ‘therapeutic warrant’ (Affleck Reference Affleck2017, 396). The therapeutic warrant demands that participant benefit must be the goal of the research, not a side effect. Talking about the trauma, he notes, is a therapeutic benefit that is merely incidental to research participation. (Of course, even if we accepted the validity of risk/benefit calculations, it would be a concern that political scientists have no objective way to measure risk and benefit, much less in the same units – see Phillips Reference Phillips2021 and Campbell and Adams Reference Campbell and Adams2009.) Affleck (Reference Affleck2017) ultimately calls for researchers to be more precise when defining the risks and benefits of research for participants, so to ensure a greater balance between personal risks and impersonal benefits (he cites, on this point, a ‘Component Analysis’ framework for assessing the harms and benefits of research proposed by Weijer Reference Weijer2000).

Where Affleck (Reference Affleck2017) takes aim at the consequentialist, cost-benefit logic contained in the Common Rule, other scholars criticize the Common Rule for being a rule. Clark and Walker (Reference Clark and Walker2011) describe the dominant approach in research ethics not as reflecting consequentialism or utilitarianism, but as reflecting a ‘[d]eontological principalism’ (p. 1493). On this account, scholars of victimization have come to prioritize following the rules over preventing exploitation (Clark and Walker Reference Clark and Walker2011). Like Affleck (Reference Affleck2017), Clark and Walker want scientists studying traumatized populations to think harder about the risks and benefits of their research, but they want specifically for scientists to start from a point of reflecting on the lived experiences of research participants. For scientists to do this successfully, Clark and Walker argue that they must adopt a sort of virtue ethics – trying to be deeply good, flexible ethical thinkers who can assess different challenges (2011).Footnote 12

A Minimal Risk of Retraumatization Does Not Ethical Research Make

What we learn from the normative theorists (feminist, postcolonial, and anti-legalistic) is that the standard consequentialist/deontological research ethics framework – associated with the Common Rule and legal codes – is not always enough. A large empirical literature (see Section “Does Research Retraumatize People?”) suggests that retraumatization and related experiences are not common or serious occurrences in many human subjects’ research on sensitive topics. Trauma-related research and research on sensitive topics therefore seem to fall within the confines of an institutional review board’s ‘minimal risk’ criterion as long as the research is thoughtfully designed and participants have adequate resources. Moreover, within a consequentialist cost-benefit analysis, it seems likely that the minimal risk of retraumatization and distress is outweighed by the psychological benefits of research participation for participants who have experienced traumatic events, not to mention the benefits of crucial social scientific research on topics like war and domestic violence. But trauma and traumatizing power dynamics are difficult to study and describe objectively (see “Insights from Feminist Ethics”), what counts as mental wellbeing is culturally conditioned (see “Insights from Postcolonial Theory”), and cost-benefit analysis might not even be the right framework to talk about protecting research participants amid trauma-related concerns (see “Critiques of Legalistic Research Ethics”).

Given these concerns about the prevailing consequentialist logic, we have normative reasons – as empirical scientists – to wonder whether we are doing enough about trauma just by evaluating the risk of retraumatization and finding it to be low. The APSA guidelines have chosen to prioritize retraumatization as a potential trauma-related harm of the research process (American Political Science Association 2020; 2022), but we should view this as an entryway to a larger discussion about doing ethical, trauma-informed political science that prioritizes participant wellbeing holistically rather than narrowly.

A Framework for Trauma-Informed Political Science Research

The consensus of the scholars cited in Sections “Does Research Retraumatize People?” and “Is It Wrong to Ask People about Trauma?” is that trauma-related research and research on sensitive topics can and should continue in many cases, notwithstanding cautions or objections laid out by Tuck and Yang (Reference Tuck and Yang2014b), among others. Systematizing how to do that research well is the focus of this section of the paper. First, I discuss possible extreme cases in which human data collection truly is or becomes infeasible or inappropriate. Second, I offer a general framework of different practices for doing trauma-informed human subjects research in political science (Section “Trauma-Informed Political Science Data Collection”). Additional special cases – research with victims of conflict, research with children, and research approaches that significantly overhaul standard research practice – are discussed in the appendices (see Appendix Sections C–E).

When to Curtail Human Data Collection Because of Trauma

A large literature tells us that retraumatization and related traumatic or otherwise negative emotional side effects of research are uncommon in short-term research in clinical psychology and related fields and that, if they do occur, minimal and brief (see Section “Insights from Clinical Psychology and Related Fields”). In considering whether pursuing human subjects research is ever infeasible because of trauma-related concerns, we must ask what it is that makes trauma side effects rare. Most participants in research on the emotional effects of research have had access to key resources and medical services, have not been actively experiencing major traumatic events (though they often have in the past), and have been living amid geopolitically stable areas. Although we have less systematic knowledge of the emotional effects of research on other populations, it seems likely that these types of conditions – access to health and mental health resources, relatively stable environments, and absence of active threats to wellbeing – lower the prior risks of research for participants. As noted in Section “Challenges for Political Science”, scholars who work with participants experiencing extreme need and ongoing suffering have had to work very hard to provide emotionally safe research environments.

Other scholars have, at times, elected not to pursue, or stopped, original human data collection. By definition, minimizing human data collection minimizes risk. And in many cases, researchers might want to study a phenomenon yet lack the capacity to provide a safe environment for human subjects. This may occur, for example, because participants could encounter retaliation for research participation, because participants have no access to mental health services or support, or because researchers cannot find a reliable community partner organization.

As Green and Cohen (Reference Green and Cohen2021) note, ‘desk research’ that sidesteps human data collection is very appealing (they do not find it to be a perfect solution) when ‘[a]lternatives such as field-based methods, including experiments, surveys, or ethnographic research, [which] often are logistically difficult, costly, or ethically fraught by comparison’ (p. 2). With respect to retraumatization and trauma-related risks, logistics, cost, and ethics are entangled, because providing safe and ethical environments is expensive and difficult. For example, in a war zone, furnishing counsellor referrals is often impossible – either counsellors are in short supply or the distances too great to travel. And people may be separated from their families or lack access to supportive communities, so have no one with whom they could talk through something upsetting that came up in an interview.

Or research participants may, simply, be tired of telling an upsetting story again and again. Revkin and Wood (Reference Revkin and Wood2021) describe the choice to stop interviewing victims of the Islamic State’s genocide of the Yazidi. They explain that they were concerned about retraumatization and the safety of the women and their families (Revkin and Wood Reference Revkin and Wood2021). They cite a paper by Foster and Minwalla (Reference Foster and Minwalla2018), which recounts Yazidi women’s distressing experiences of being repeatedly interviewed by journalists and the women’s fear that journalistic accounts included identifying information that put them or their families at risk of retaliation or other violence. In this case, the researchers did not cease all human data collection (Revkin and Wood still interviewed a number of civilians, ex-Islamic State combatants, and others) or turn entirely to desk research, but they did make an informed decision that part of their human data collection was infeasible.

In some cases, scholars have reported being prepared to pause or stop human data collection in the case of significant reported distress, not reaching the point of needing to do so. The articles from Figure 1 provide useful examples here: for their experimental research on the incentives of non-state armed groups, Gilligan et al. (Reference Gilligan, Khadka and Samii2023) note ‘we made provisions to suspend the research and refer subjects to counsellors had they experienced any emotional distress in the research, but this never occurred’ (authors’ Appendix E, page 18). Similarly, Young, in a lab-in-field experiment testing how fear affects political dissent among 671 Zimbabweans, asked enumerators to record, at the end of each interaction, whether the participant had been retraumatized (Young Reference Young2019, see Supplementary Materials), but notes that no participants needed to be referred for counselling (Young Reference Young2019).

In other cases, researchers have paused or stopped human data collection because of observed participant distress, if not retraumatization per se. Hedström (Reference Hedström2019) reports that she stopped an interview and suggested counselling referrals because a participant – in a conflict zone in northern Myanmar – was experiencing emotional distress but afterwards was unsure that she should have unilaterally stopped the interview. In Hedström’s telling, the interviewee’s distress might have been her normal and proportionate reaction to an extreme situation and Hedström could have asked the interviewee whether she wanted to continue, before deciding to stop the interview.

What we learn from these cases is the importance of being prepared to stop or not do human data collection, even in cases where human data collection ends up proceeding. If scholars do encounter a situation such as Revkin and Wood’s Reference Revkin and Wood2021 where they decide not to do some or any human data collection to answer a question, preparation for the possibility can help them both protect existing participants and pivot toward other data. The value of mixing different data streams is also apparent in Gilligan et al. (Reference Gilligan, Khadka and Samii2023), which brings together experimental human data collection (that monitored participants for distress) with qualitative insights based on desk research. And if scholars end up in a situation where they are unsure whether to discontinue human data collection, as Hedström (Reference Hedström2019) describes, falling back on preparation might help them know how to proceed. As a general matter, preparing protocols detailing when a given instance of human subjects data collection might need to be curtailed helps researchers to design more ethical studies, because they are forced to think about what makes for a study that can continue (this insight is closely related to Lyall Reference Lyall2022’s proposal that researchers ‘preregister their ethical redlines’, see p. 1).

Trauma-Informed Political Science Data Collection

Needing to stop or not start human data collection is not the ideal case, either for researchers seeking to build crucial knowledge or even for participants who stand to gain something from it (Gordon Reference Gordon2021). This subsection of the paper outlines two approaches for doing trauma-informed political science research on sensitive topics. The approaches are distinguished by their applicability to what I call less-vulnerable and vulnerable contexts. Vulnerability exists on a continuum (Bracken-Roche et al. Reference Bracken-Roche, Bell and Racine2016). For the purposes of this paper, what I mean by it is the following: less vulnerable contexts provide key resources, have participants who are not experiencing major traumatic events, and are geopolitically stable. ‘Key resources’ here means food, shelter, and key resources relevant to psychosocial wellbeing, such as having friends or family with whom one can talk supportively or ways of accessing mental healthcare. I do not use the terms as synonyms for living in the Global North versus living in the Global South. A participant who is a victim of current domestic violence is experiencing a major traumatic event and a participant who is a migrant crossing the Rio Grande is not in a geopolitically stable environment, and that context should be classed as vulnerable even if the participants are in the USA.

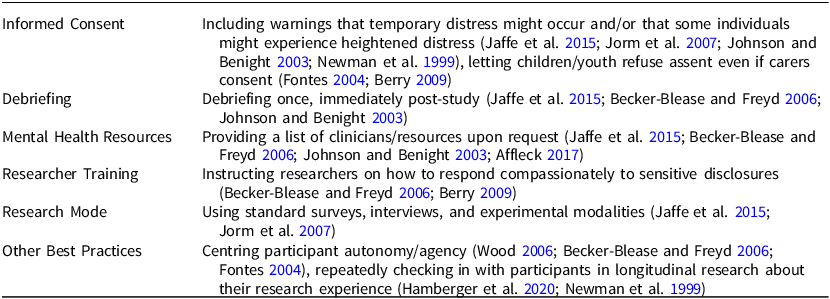

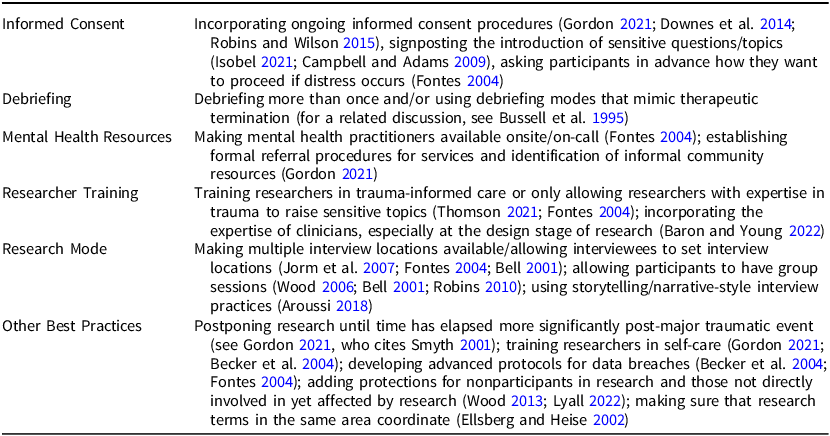

The first approach (Table 1) reflects the insights of scholars who have identified a minimal risk of retraumatization and other trauma-related negative effects in their research in less vulnerable contexts (like those discussed in Section “Insights from Clinical Psychology and Related Fields”). The second approach (Table 2) is informed by the recommendations of political scientists and other scholars working in vulnerable contexts. (Scholars other than me also use the term ‘vulnerable’ to describe comparable research participant populations but they might or might not mean something slightly different by it; see for example, Lyall Reference Lyall2022.) The recommendations that I associate with the second approach are, to a large extent, oriented toward providing the very minimal baseline of resources (for example, people to talk to) and stable environments (for example, safe rooms for interviewing) that less vulnerable contexts might already have.

Table 1. Less-vulnerable contexts: Trauma-informed practices for research on sensitive topics

Table 2. Vulnerable contexts: Trauma-informed practices for research on sensitive topics

By grouping recommendations into two approaches associated with different context characteristics, I intend to make it easier for researchers to find options appropriate for their methods and research environments. As Baron and Young (Reference Baron and Young2022), Morris MacLean et al. (Reference Morris MacLean, Posner, Thomson and Wood2019), Wood (Reference Wood2006), and many other scholars have noted, there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution for research ethics. For each approach, I identify recommendations for informed consent, debriefing, provision of mental health resources, researcher training, and any other general practices. However, researchers can and should mix practices as they see fit for their case. An important caveat is that most of the best practice recommendations have not been tested as interventions. That is, many scholars cited here conducted research on the experience of being a research participant, then – usually in a paper’s discussion section – offered a holistic impression of ideal methods even if those methods were not per se being tested. (Some, for example, Hamberger et al. Reference Hamberger, Larsen and Ambuel2020, also asked participants for suggestions about improving the research experience.)

The components of the first approach should be familiar to most political scientists. Review boards and journals regularly expect that researchers develop context-specific informed consent procedures and debrief participants. We do not observe the counterfactual world in which these research ethics practices are not standard – except to the extent we know what happened before the advent of modern research ethics – so it seems likely that these research ethics practices have enabled numerous clinical psychologists to find a low risk of retraumatization in research in less-vulnerable contexts.

Even so, scholars have suggested that we can improve how we approach the most standard research practices and customize them to different research programmes. Informed consent deserves special mention here. Thomson (Reference Thomson2021) writes that this usual informed consent standard – though strict and established in US federal law – should still be understood as narrow in scope because it is too easily treated as just one item on a ‘procedural checklist’ (p. 530). Even in seemingly low-risk research settings (for example, survey experiments on attitudes) and especially in more complex or higher-risk ones (for example, interviews that take place in areas of conflict), doing trauma-informed research entails giving participants a clear and detailed picture of what to expect in the specific study and, of course, reminding them that they may opt-out at any time (Jaffe et al. Reference Jaffe, DiLillo, Hoffman, Haikalis and Dykstra2015; Thomson Reference Thomson2021).

Other research practices that I associate with the first approach might be less commonly implemented in some political science settings, for understandable reasons. For example, although resource lists are easy to provide when research participants have national insurance or are already connected in an institution such as a hospital or university, they might be more difficult to develop for US survey respondents on Lucid or YouGov. In that specific setting, researchers might refer to resources such as the ‘Find Help’ page on the website of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, see samhsa.gov. And ‘centering participant agency/autonomy’ is a common recommendation in the research ethics literature, but an uncommon language in applied scholarship (cf. Nickerson et al. Reference Nickerson, Platas, Robinson, Samii and Sinmazdemir2019). Practically, it usually entails reminding participants of their right to opt out of research (which is also part of informed consent, see Jaffe et al. Reference Jaffe, DiLillo, Hoffman, Haikalis and Dykstra2015; Gordon Reference Gordon2021) and, in interviews, allowing participants to control the flow of a conversation as much as possible (Thomson Reference Thomson2009).

Where the first approach contains the recommendations of many clinical psychologists working in relatively low-risk contexts, the second approach (Table 2) draws on scholarship by political scientists and practitioners doing work adjacent to conflict or repression, including Wood (Reference Wood2006), Thomson (Reference Thomson2013), Bell (Reference Bell2001), and Robins and Wilson (Reference Robins and Wilson2015). The specific practices minimize harm and enhance benefits in different ways. Multiple debriefings or check-ins may make participants living in vulnerable contexts feel supported in longitudinal research (these additional debriefings can be either opt-in or default, see Hamberger et al. Reference Hamberger, Larsen and Ambuel2020). Making mental health service providers immediately available, restricting the researcher or interviewer pool to trauma experts, and/or trauma-training researchers may help research subjects with PTSD or extremely complex or recent traumatic experiences (Thomson Reference Thomson2013).Footnote 13 Developing advanced breach-of-confidentiality procedures or creating room for flexibility in interview locations or modes may be especially critical for the safety of people who are currently experiencing violence or whose families are at risk (for example, recall Foster and Minwalla Reference Foster and Minwalla2018 on the concern of Yazidi interviewees for the safety of their families after inappropriate disclosures by interviewers). And training researchers in self-care (Gordon Reference Gordon2021) can help researchers to stay focused and supportive, and avoid burnout, even in difficult environments.

Although practices in the second approach are most essential for vulnerable contexts – that is, contexts in which key resources are lacking, that feature traumatic events, and/or that are geopolitically unstable – these practices could still be applied in other settings (see Peter and Friedland Reference Peter and Friedland2017). Moreover, IRBs often require practices that I associate with the second approach even for research not in vulnerable contexts. For example, the EGAP memorandum on research ethics cites a case of attitudinal questions about abortion triggering IRB concern (Nickerson et al. Reference Nickerson, Platas, Robinson, Samii and Sinmazdemir2019). A survey experiment on abortion attitudes in a stable environment could include multiple follow-ups, trauma care-trained researchers, and group research settings. However, the abortion attitudes survey might not need to include those protocols in the way that a series of in-depth interviews with refugees living in a UNHCR camp would.