Introduction

Citizens’ satisfaction with democracy is vital for political stability, but a persistent gap exists between those who win and lose the election (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005; Anderson and Guillory Reference Anderson and Guillory1997; Blais and Gélineau Reference Blais and Gélineau2007; Daoust and Nadeau Reference Daoust and Nadeau2023; Esaiasson Reference Esaiasson2011; Kern and Kölln Reference Kern and Kölln2022; Singh et al. Reference Singh, Karakoç and Blais2012; van der Meer and Steenvoorden Reference van der Meer and Steenvoorden2018). Despite the robustness of this finding in the literature, it is still rather disputed to what extent this so-called winner-loser gap is problematic, for example, for democratic legitimacy or considering losers’ consent to the election outcome. In fact, little is still known about the actual consequences of the winner-loser gap. Understanding how winners and losers react to electoral defeat is therefore crucial for assessing broader challenges to democratic stability, particularly in times of growing political polarization and increasing dissatisfaction with traditional democratic institutions.

In established European democracies, we believe it is unlikely that citizens who lose the elections – electoral losers – would abandon democracy following an electoral defeat. Instead, in seeking alternative ways to influence political decisions while their preferred party is in opposition, they may desire more democracy. Specifically, they might be more inclined to support additional instruments to influence decision making, such as referendums. While studies have revealed that support for the use of referendums is generally high among European citizens (Schuck and de Vreese Reference Schuck and de Vreese2015; Werner et al. Reference Werner, Marien and Felicetti2020), little is known about the dynamic determinants of this support. Existing research has mainly focused on stable determinants such as political attitudes or sociodemographic backgrounds (Bowler et al. Reference Bowler, Denemark, Donovan and McDonnell2017; Coffé and Michels Reference Coffé and Michels2014; Gherghina and Geissel Reference Gherghina and Geissel2020; Már and Gastil Reference Már and Gastil2023). However, studies in the USA have found that instrumental considerations, rooted in electoral win and loss, can also play a key role in predicting support for referendums (Bowler and Donovan Reference Bowler and Donovan2007; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Tolbert and Keller2010). These explanations could similarly affect support for democratic reforms in Europe as well (Pilet et al. Reference Pilet, Bedock, Talukder and Rangoni2023; Werner Reference Werner2020).

In this article, we test whether electoral losers are more supportive of the use of referendums than electoral winners. In addition, we theorize that affective polarization plays an important moderating role in the winner-loser gap in support for referendums. Affective polarization refers to the extent to which politics generates prejudice, discrimination, and hostility among voters, marked by a strong emotional attachment to one’s own party and dislike or even hostility toward other parties. We expect that this emotional involvement in politics amplifies the winner-loser gap in referendum support. For affectively polarized electoral losers, referendums offer a promising alternative route to power, which partially mitigates the electoral defeat. By contrast, electoral winners should be displeased with the prospect of the disliked opposition influencing politics even when they are not in government.

We test this argument using a survey dataset collected in thirteen European democracies in the latter half of 2022. Our findings show that support for referendums is high overall, with electoral losers consistently more supportive of their use than electoral winners. Furthermore, we confirm that affective polarization has a strong amplifying effect. Specifically, when voters are not at all polarized, there is no significant difference in referendum support between electoral losers and winners – they express similar, high levels of support. However, as voters become more polarized, electoral winners start to become less supportive of referendums, while the attitudes of electoral losers remain stable. This suggests that the winner-loser gap in referendum support exists only among polarized voters who are strongly emotionally involved in politics.

The article proceeds as follows. First, we review the literature on the winner-loser gap in democratic satisfaction, theorize how this may extend to support for referendums, and argue that affective polarization should function as an important moderator. Next, we introduce our dataset and explain how variables are measured. We then begin with a descriptive analysis of attitudes towards referendums, followed by the presentation of our full fixed-effects linear regression models. Finally, we conclude and reflect on the broader implications of our findings.

The Winner-Loser Gap and Support for Referendums

A large body of literature has sought to unravel the effects of elections on democratic attitudes among citizens living in Western democracies. One of the most consistent findings in this literature is that citizens who voted for a party that joins the government (either alone or in coalition) after the election are more satisfied with democracy than citizens who voted for a party that ends up in the opposition (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005; Anderson and Guillory Reference Anderson and Guillory1997; Blais and Gélineau Reference Blais and Gélineau2007; Daoust et al. Reference Daoust, Ridge and Mongrain2023; Daoust and Nadeau Reference Daoust and Nadeau2023; Esaiasson Reference Esaiasson2011; Kern and Kölln Reference Kern and Kölln2022; Ridge Reference Ridge2023; Singh Reference Singh2014; Singh et al. Reference Singh, Karakoç and Blais2012). This so-called winner-loser gap in democratic satisfaction has been consistently observed, although its magnitude can vary across different contexts and among various subgroups of the electorate. Nonetheless, these variations reflect differences in the size of the gap, not its existence. For example, while the winner-loser gap is more pronounced in majoritarian democratic systems, it is also present in proportional systems (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005; Anderson and Guillory Reference Anderson and Guillory1997; Dahlberg and Linde Reference Dahlberg and Linde2016). In a similar vein, the winner-loser gap is larger in elections where voting is voluntary, but it is still present in compulsory voting systems likewise (Singh Reference Singh2023). Accordingly, Daoust and Nadeau (Reference Daoust and Nadeau2023, 51) recently referred to it as ‘arguably one of the most robust relationships in political science’.

Broadly speaking, there are two main reasons for the relevance of studying the winner-loser gap in democratic satisfaction. First, it touches on the broader discussion about citizens’ satisfaction with democracy, which is seen as a vital attitude for democratic survival. Scholars have argued that democracies need a certain level of public approval to remain relevant, functional, and stable (Easton Reference Easton1965; Lipset Reference Lipset1959). Consequently, much of the literature has focused on the factors that drive satisfaction with democracy among the public (Aarts and Thomassen Reference Aarts and Thomassen2008; Banducci and Karp Reference Banducci and Karp2003; Dahlberg and Holmberg Reference Dahlberg and Holmberg2014; Ezrow and Xezonakis Reference Ezrow and Xezonakis2011; Quaranta and Martini Reference Quaranta and Martini2016). At the individual level, winning and losing elections is one of the most important predictors (Singh and Mayne Reference Singh and Mayne2023). Democratic elections naturally create winners and losers, both among political parties and the voters that elect them. For democracies to remain legitimate and relevant, it is crucial that electoral losers assess their defeat as part of the democratic game, with a chance to perform better in the future. If, instead, they come to believe that the democratic system does not work for them, they may choose to abstain from future elections.

Second, while elections are central to the democratic system, they also serve as a test of the system’s resilience. Democracies can only thrive when electoral integrity is undisputed, there are no doubts about the legitimacy of the results, and the outgoing incumbent adheres to a peaceful transition of power. In essence, this means that electoral losers must accept the results, no matter how displeasing they may be. As Nadeau and Blais (Reference Nadeau and Blais1993, 553) already pointed out three decades ago, ‘the viability of electoral democracy depends on its ability to secure the support of a substantial proportion of individuals who are displeased with the outcome of an election.’ The level of democratic satisfaction among this group after an election is generally seen as an indicator of how likely it is that electoral integrity may be challenged (Nadeau et al. Reference Nadeau, Daoust and Dassonneville2023). While the mere presence of a winner-loser gap is not necessarily problematic, this gap should not become too large.

In sum, research into the winner-loser gap is generally driven by concerns about support for representative democracy and losers’ consent. Electoral losers who are too dissatisfied with the election outcome might be unwilling to accept it. Others might accept the outcome but lose faith in the ability of representative democracy to deliver for them. Despite the large scholarly attention devoted to the winner-loser gap and its potentially negative implications, surprisingly little is known about its actual consequences. In this regard, Esaiasson (Reference Esaiasson2011) criticized that the worrying impact of the winner-loser gap may be overstated, as it is largely driven by an increase in democratic satisfaction among electoral winners rather than a decrease among electoral losers.

While we acknowledge that dissatisfaction rooted in electoral defeat can potentially lead to dissatisfaction or even aversion to representative democracy, we do not believe that these voters would lose interest in their primary means of influencing politics in such systems. Electoral losers are not a monolithic group. Some may have won previous elections and maintain faith that they can win elections in the future. Others might have lost several elections already but still value their possibility of finding representation (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967), even if it does not produce clear results in terms of policies after the election.

Rather, we believe that citizens who find themselves on the losing side of national elections are more likely to desire even more democracy. That is, in a desire to find alternative routes to influence policies, they focus on alternative democratic instruments that can enhance their influence on decision making. This desire is rooted in utility: since national elections occur only once every several years, the ability of voters to influence politics is limited. This is particularly problematic for electoral losers, who are likely to expect that the incoming government will implement undesired policies. Accordingly, we suggest that electoral losers should be particularly supportive of alternative mechanisms to influence decision making.

Often presented as the main instrument inspired by direct democracy theories, one of the most well-known innovations aimed at providing citizens with more direct influence in politics is the referendum. In light of the various though increasing use of referendums among European countries (Hollander Reference Hollander2019; Leininger Reference Leininger2015), the referendum is likely the best-known democratic instrument among citizens beyond general elections. Cross-national survey results indicate that referendums are generally a popular instrument among the public (Bengtsson and Mattila Reference Bengtsson and Mattila2009; Bowler et al. Reference Bowler, Donovan and Karp2007; Dalton et al. Reference Dalton, Burklin and Drummond2001; Font et al., Reference Font, Wojcieszak and Navarro2015; Schuck and de Vreese Reference Schuck and de Vreese2015; Werner et al. Reference Werner, Marien and Felicetti2020). Although different types of referendums exist (Hug Reference Hug2004), all referendums bypass the government by asking citizens directly to vote on a specific policy and then present the government with the outcome. This process offers electoral losers a unique opportunity to express dissatisfaction with policy proposals and to steer the government in a desired direction. Furthermore, compared to other types of democratic innovations that provide electoral losers with possibilities to influence policies beyond general elections – especially talk-centric democratic innovations such as deliberative mini-publics – referendums exert more influence, are accessible to all electoral losers, and are less time-consuming. Electoral winners, however, should be less convinced of the use of referendums. Given that their party has ended up in government, they would expect that the government creates policies that align with their own preferences, leaving them with little incentive to advocate for (more) referendums. In fact, they might view these participatory tools as a threat to their preferred policy agenda precisely because referendums bypass their government. This should, in turn, lead to lower support compared to electoral losers. Indeed, prior research into the effects of direct democracy has shown that it has the ability to decrease the winner-loser gap in satisfaction with democracy, most likely because it softens the burden of electoral loss and weakens the strength of electoral victory (Leemann and Stadelmann-Steffen Reference Leemann and Stadelmann-Steffen2022). Greater use of direct democracy also reduces the importance of national elections for voters (Freitag and Stadelmann-Steffen Reference Freitag and Stadelmann-Steffen2010).

The idea that citizens’ support for referendums depends on instrumental considerations is not new. While existing explanations regarding the broader aspect of public support for democratic innovations and process preferences primarily focus on relatively stable determinants – such as political attitudes like distrust in representative institutions or dissatisfaction with democracy (Bedock and Pilet Reference Bedock and Pilet2023; Bertsou and Caramani Reference Bertsou and Caramani2022; Gherghina and Geissel Reference Gherghina and Geissel2020; Schuck and de Vreese Reference Schuck and de Vreese2015) or sociodemographic backgrounds (Coffé and Michels Reference Coffé and Michels2014; Már and Gastil Reference Már and Gastil2023; Schuck and de Vreese Reference Schuck and de Vreese2015) – some accounts emphasise the importance of more dynamic factors. Furthermore, Bowler and Donovan (Reference Bowler and Donovan2007) studied public support for democratic reforms in the USA, such as nationwide referendums or proportional representation in Congress. Despite general high support, framing the reform as an electoral risk for one’s own party reduced support only among electoral winners. By contrast, electoral losers were more willing to accept the risk of electoral reform regardless of the risk. In the same context, Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Tolbert and Keller2010) studied preferences for referendums around the 2008 US presidential elections. They found that independents – long-term structural losers in the US two-party system – strongly support the introduction of a national referendum regardless of the election outcome. In addition, they causally showed with a panel survey that even Republican voters, who had only just lost the presidency to the Democrats, already significantly increased their support for nationwide referendums in response to the electoral loss.

Although this argument has not been tested in Europe thus far, suggestive evidence from across the Atlantic does exist. Through an experimental design, Werner (Reference Werner2020) demonstrated that Dutch citizens are more likely to support referendums on policy proposals that they support themselves or for which they believe a majority of the electorate holds similar views on. In a similar vein, Brummel (Reference Brummel2020) studied the effects of winning or losing a referendum on citizens’ support for the instrument using panel survey data from five referendums held in three different countries (Germany, Finland, and the Netherlands). He found some limited evidence that a referendum victory leads winners to increase their support for the instrument, but stronger evidence that a defeat results in decreased support among the losers. While these findings are not directly related to the winner-loser gap generated by electoral outcomes, they do indicate that instrumental considerations are important predictors of support for referendums. Additionally, a recent study by Pilet et al. (Reference Pilet, Bedock, Talukder and Rangoni2023) examined the election-based winner-loser gap as an explanation for the support of deliberative mini-publics, a talk-centric form of democratic innovation in which citizens are selected by lot to participate in discussions about policy issues (Paulis et al. Reference Paulis, Pilet, Panel, Vittori and Close2021). Their main finding is that European voters from opposition parties, especially those that have never been in power, are more supportive of the use of DMPs. We expect a similar process among European voters in support for referendums.

H1: Electoral losers are more supportive of referendums than electoral winners.

The Moderating Role of Affective Polarization

We argue that the winner-loser gap in support for referendums depends on an important moderator: affective polarization. This concept is relatively new and refers to the increased political hostility between citizens that democracies have been witnessing recently. It is rooted in social identity theory (Tajfel Reference Tajfel1970; Tajfel et al. Reference Tajfel, Billig, Bundy and Flament1971), which posits that individuals tend to think along group lines. In this process, they are inclined to treat people of their own group favourably, while members of other groups are treated with bias or even outright hostility. Applied to the context of politics, Iyengar et al. (Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012) argue that partisan identities provide precisely such a group that conducts to group-thinking. Voters hold positive views of other voters who cast their ballot for the same party, while voters from other parties are strongly disliked. Though originally studied in the US two-party system (Iyengar and Westwood Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015; Mason Reference Mason2018), affective polarization is also widespread in European multi-party systems (Garzia et al. Reference Garzia, Ferreira da Silva and Maye2023; Reiljan Reference Reiljan2020).

Early studies on affective polarization predominantly focused on its effects on non-political behaviour and attitudes, such as social trust (Lee Reference Lee2022; Torcal and Thomson Reference Torcal and Thomson2023), discrimination (Iyengar and Westwood Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015; Westwood et al. Reference Westwood, Iyengar, Walgrave, Leonisio, Miller and Strijbis2018), or the willingness to engage in social relationships with voters of the other party (Huber and Malhotra Reference Huber and Malhotra2017; Lelkes and Westwood Reference Lelkes and Westwood2017). Importantly, though, affective polarization also influences political behaviour and attitudes, such as political trust (Skytte Reference Skytte2021; Torcal and Carty Reference Torcal and Carty2022), turnout (Harteveld and Wagner Reference Harteveld and Wagner2022; Phillips Reference Phillips2024), and satisfaction with democracy (Guedes-Neto 2022; Ridge Reference Ridge2022; Wagner Reference Wagner2021).

Affective polarization consists of two components: sympathy toward one’s own political group and hostility toward political outgroups. High levels of affective polarization are characterized by strong emotional responses toward different parties (and their voters) to such an extent that partisan identities become social identities. As such, the performance of someone’s party also becomes more personal (Ward and Tavits Reference Ward and Tavits2019). When someone’s party performs well, positive emotions are triggered; likewise, poor performance triggers negative emotions. In a similar vein, affectively polarized voters should be particularly happy when the disliked outparty performs poorly, regardless of their own party’s performance. While party performance can be assessed in several ways, the most obvious one is the election result. Indeed, Janssen (Reference Janssen2023) studied how the winner-loser gap is influenced by affective polarization. In a panel study of British voters, she showed that affective polarization amplifies the post-electoral winner-loser gap in democratic satisfaction; voters who are more affectively polarized respond more strongly to electoral wins and losses.

Accordingly, we expect that affective polarization also strengthens the winner-loser gap in support for referendums. That is, voters who are only mildly polarized will experience a moderate emotional response to the election result. By contrast, the emotional response among strongly polarized voters should be higher: positive for election winners and negative for election losers. This translates into their attitudes toward referendums, which essentially offer an alternative route to decision making alongside the traditional governmental one. Affectively polarized winners should thus be less supportive of referendums than non-polarized winners, and affectively polarized losers should be more supportive than non-polarized losers. We expect that this occurs because of two potential mechanisms: utility and emotions. With regard to utility, we expect that polarized election winners see referendums as a threat to their electoral victory and the ability of their party to govern without constraint. Since their preferred party is already in power, there is little need for additional mechanisms to steer policy making. In fact, since a referendum bypasses the government, it could actually harm the government’s policy agenda if its outcome directly conflicts with it. Non-polarized winners, however, are less invested in their government and should, therefore, see less threat in the use of referendums. Moreover, as they are less hostile toward other parties, they should see their potential use of referendums also as less problematic.

By contrast, polarized election losers are likely to be very disappointed with the electoral result. Losing elections is painful, especially for voters who are heavily attached to their party and their desired policies. This makes the prospect of being unable to influence policies for several years even more difficult. In addition, other strongly disliked parties will create these policies instead. Electoral losers who are less attached to their party will also experience disappointment with the electoral result, but less severely. Given that they identify less strongly with the party for which they voted, coping with the electoral defeat should be easier, as they may be less attached to the party’s policy agenda, for example, because they do not care that much about politics or because they cast a strategic vote. As such, we would expect that polarized electoral losers view referendums as potential avenues to soften the burden of the election result by means of an alternative instrument. They provide a way to influence policies despite the electoral defeat and counter the disliked government parties in the pursuit of their policy agenda.

With regard to emotions, we know that affectively polarized citizens strongly like their own party but dislike other parties. Winning an election, therefore, becomes a personal victory for polarized voters, and seeing the electoral loss of disliked other parties should also provide certain joy. Yet, referendums offer these parties the possibility to still influence politics, which diminishes the pain of the electoral defeat. We expect that polarized winners are displeased with this, and thus do not want to grant these parties any alternative possibility to become meaningful in politics again. For electoral losers, we expect the opposite. While losing the election in itself was already painful, it hurts even more to see parties in power that are strongly disliked. Gaining the possibility to frustrate these parties through a referendum while increasing the relevance of the own party should, therefore, be an attractive possibility. For both winners and losers, these emotional responses should be less present with low levels of affective polarization, simply because these voters do not care that much about the own party and also do not feel large hostility toward other parties.

Admittedly, the two mechanisms of utility and emotions are closely related and intertwined and probably cannot be completely disentangled. Emotions tied to electoral performance are, at least to some extent, likely to be driven by considerations about future policies. Our goal here is not to see which mechanism applies but rather to acknowledge that both likely operate simultaneously. We do not have differential expectations with regard to the effects of affective polarization on electoral winners and losers. As we described above, similar mechanisms should apply to both.

H2a: The decrease in support for referendums among electoral winners is stronger for citizens with higher levels of affective polarization.

H2b: The increase in support for referendums among electoral losers is stronger for citizens with higher levels of affective polarization.

Data and Methods

Dataset

To test our argument, we rely on survey data collected in thirteen European democracies: Belgium (with samples in both Flanders and Wallonia), the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, and the UK. The survey was fielded between June 2021 and March 2022 and used country-specific quotas for age, gender, education, and region. This ensured that the sample filling out the questionnaire was representative of the larger population in each country at the time of the survey. Most sample sizes range from 1,200 and 1,400, with only the Czech Republic (N=1,985) and Flanders (N=1,066) somewhat deviating. This dataset is particularly suitable for our research purpose because it includes both variables on support for referendums and affective polarization. While there are some other cross-national datasets (such as the European Social Survey) that measure referendum support, they do not capture affective polarization.

Importantly, we exclude two countries that were originally part of the dataset: Bulgaria and Italy. In both cases, it is difficult to assign voters into groups of electoral winners and losers. In Bulgaria, fieldwork took place during the third parliamentary election of November 2021, as parties had been unable to form a coalition after the previous elections in April and July of that year. In Italy, the survey was conducted between June and August 2021, during which the government was headed by Mario Draghi. This government consisted of a supermajority of nearly all parties, representing almost 90 per cent of the seats in both houses of parliament. As a result, nearly all respondents in our sample would be classified as electoral winners.

Still, for generalization, the country selection ensures contextual diversity in several aspects. First, it covers European democracies with different political systems and government structures (ranging from single-party to broad coalition governments), with varying degrees of experience with the use of referendums. Second, all geographical regions of Europe are represented. Finally, the countries exhibit different average levels of affective polarization (Garzia et al. Reference Garzia, Ferreira da Silva and Maye2023). The obvious trade-off that comes with the generalizability of these data is their limited ability to support strong causal claims. Given the cross-sectional nature, unobserved confounders could be driving the relationship between electoral loss and referendum support. To partially address this, we provide multiple additional analyses in the robustness section that control for potential confounders.

Dependent Variable

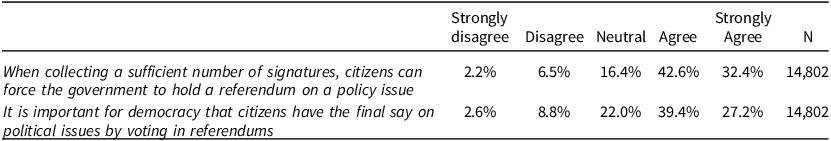

To test our argument, we rely on two variables that capture attitudes toward referendums. Respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement on a 5-point Likert scale in response to a series of statements. The first statement we use to measure our dependent variable is: When collecting a sufficient number of signatures, citizens can force the government to hold a referendum on a policy issue. The second statement is: It is important for democracy that citizens have the final say on political issues by voting in referendums. Higher values on these statements signal greater support for referendums. Given the low proportion of ‘Don’t know’ responses (∼ 3 per cent), we are confident that respondents are familiar with the principle of a referendum.

We report the frequencies in Table 1 for all countries combined. Support for both variables is high, consistent with previous research on public support for referendums (Bengtsson and Mattila Reference Bengtsson and Mattila2009; Bowler et al. Reference Bowler, Donovan and Karp2007; Dalton et al. Reference Dalton, Burklin and Drummond2001; Font et al., Reference Font, Wojcieszak and Navarro2015; Schuck and de Vreese Reference Schuck and de Vreese2015; Werner et al. Reference Werner, Marien and Felicetti2020). Although the aggregated distribution of responses for both variables shows a strikingly similar pattern, support for the first variable is slightly higher. Crucial to our paper is the expectation that the same effects apply to both variables. Therefore, we combine the two variables into a single dependent variable by summing the responses for each respondent and dividing them by 2, resulting in a robust measure of referendum support ranging from 1 (strongly opposed) to 5 (strongly supportive).

Table 1. Distribution of attitudes toward the use of referendums

Independent Variables

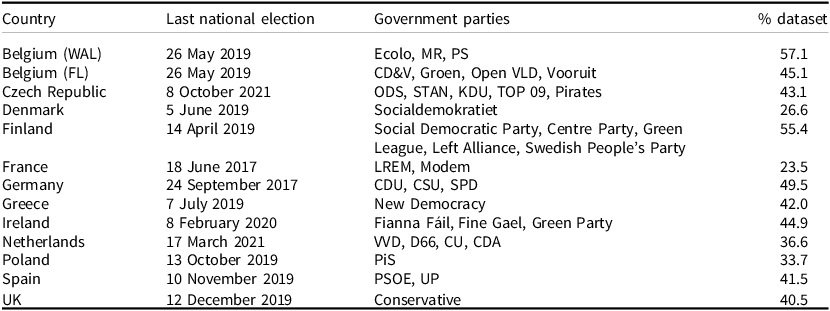

Following existing literature on the winner-loser gap (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005; Esaiasson Reference Esaiasson2011; Singh Reference Singh2014), we operationalize election winners as those who voted for a party that is currently in government. We used a variable in the dataset that asked respondents about their vote choice during the last national election. This choice is not without criticism. For example, winning and losing elections may have meanings that transcend the simple classification of being in government or not. Another important aspect, for example, could be the seat share (or its growth) obtained in the last election (van der Meer and Steenvoorden Reference van der Meer and Steenvoorden2018). Nevertheless, since subjective feelings about winning elections are strongly driven by voting for a party in government (Plescia Reference Plescia2019), we are confident that this approach is suited for our research purpose. In Table 2, we present which parties were in government at the time the survey was fielded, and thus which voters are classified as electoral winners.

Table 2. Government parties by country

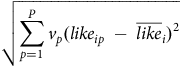

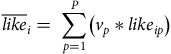

Regarding affective polarization, we rely on the commonly used party thermometer like-dislike question, which asks respondents how they feel about the various political parties in their system, ranging from 0 (very negative) to 100 (very positive). This question is widely used in affective polarization research, particularly in studies focusing on multi-party systems (Garzia et al. Reference Garzia, Ferreira da Silva and Maye2023; Reiljan Reference Reiljan2020; Wagner Reference Wagner2021). More importantly, the party thermometer question has been validated as a reliable measure of affective polarization (Gidron et al. Reference Gidron, Sheffer and Mor2022). To calculate affective polarization at the individual level, we use the spread-of-scores approach suggested by Wagner (Reference Wagner2021). This approach is especially suited for multi-party systems as it acknowledges that voters may feel positively toward multiple parties, for example, because they are closely aligned ideologically (Algara and Zur Reference Algara and Zur2023). To remain consistent with the original approach, we divide the scores by 10. The theoretical range of the variable is 0 to 5, with 5 reflecting the most polarized citizens. It is calculated in the following way:

$$\sqrt {\mathop \sum \limits_{p = 1}^P {v_p}{{(lik{e_{ip}}\; - \;{{\overline {like} }_i})}^2}} \;$$

$$\sqrt {\mathop \sum \limits_{p = 1}^P {v_p}{{(lik{e_{ip}}\; - \;{{\overline {like} }_i})}^2}} \;$$

Where p represents the particular party for which the like score is given, i the respondent, like ip a respondent’s sympathy toward a party, and v p the vote share of the particular party. The mean like score, as reflected at the end of the equation, should also be weighted according to party size:

$${\overline {like} _i} = \;\mathop \sum \limits_{p = 1}^P \left( {{v_p}*lik{e_{ip}}} \right)$$

$${\overline {like} _i} = \;\mathop \sum \limits_{p = 1}^P \left( {{v_p}*lik{e_{ip}}} \right)$$

We also control for several variables that we expect to influence support for referendums based on previous literature (Bengtsson and Mattila Reference Bengtsson and Mattila2009; Coffé and Michels Reference Coffé and Michels2014; Font et al., Reference Font, Wojcieszak and Navarro2015; Gherghina and Geissel Reference Gherghina and Geissel2020). Concerning political variables, we control for internal political efficacy (to what extent a respondent agrees that politics is too complicated for them, 4-point scale of agreement), political interest (1–4, ranging from not at all to very), and a respondent’s left-right self-placement (0–10). Additionally, we account for sociodemographic background through gender, education, age (seven categories), and occupational status (unemployed, not in labour force, employed).

Modelling Strategy

Despite the hierarchical data structure (with respondents nested in countries), we believe that using a multilevel model is ill-suited because of the low number of clusters (thirteen). In addition, our independent variables are not measured at the country-level, which is one of the primary reasons to use a multilevel model. We therefore opt for a regular linear model, including country-fixed effects. This approach removes all variation that might be caused by contextual factors at the country level.

Results

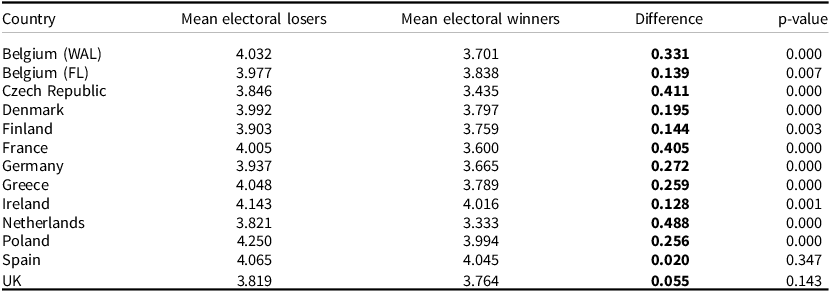

To provide an initial insight into the data, we begin with a descriptive analysis of the difference in support for referendums between electoral winners and losers. In Table 3, we display the mean scores for our dependent variables, split by electoral losers and winners and divided by country. This yields thirteen opportunities to analyse the differences in referendum support between electoral losers and winners. These first results indeed point toward a systematic difference, with electoral losers being more supportive of the use of referendums across all the countries under study. In particular, the differences are substantial in the Czech Republic, France, and the Netherlands, approaching half a unit of difference on the 1–5 scale. In addition, we conducted one-tailed t-tests to assess whether the higher support for referendums among electoral losers is statistically significant. In eleven out of the thirteen cases, the p-value is indeed below 0.01. The only two countries that show null results are Spain and the UK. Although electoral losers in these countries are more supportive of referendums, the differences are small and not statistically significant.

Table 3. Difference in support for referendum between electoral losers and winners

The p-values are based on a one-tailed t-test. Differences in bold are in the hypothesized direction.

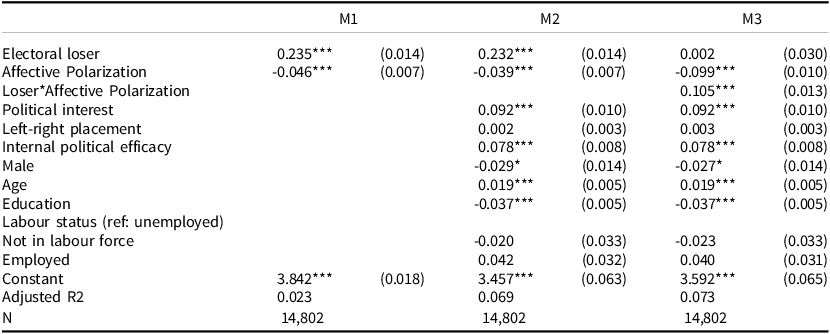

Thus, this analysis overall supports H1. To account for potential confounders, we now turn to the linear fixed-effects regression models in Table 4, where we also test the moderating effect of affective polarization, as outlined in H2. We present three models: first, we include the main independent variables (electoral loser and affective polarization); next, we add the control variables; and finally, we add the interaction term to test H2.

Table 4. Fixed-effects linear regression models explaining public support for referendums

Robust standard errors in parentheses. Country fixed effects are not displayed.

*p<0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001.

The results presented in Table 4 confirm that electoral losers are indeed more supportive of the use of referendums. In Model 1, we find a positive effect of being an electoral loser on support for referendums, which is highly statistically significant (p<0.001). Once we add the control variables to the regression in Model 2, this positive effect remains unchanged: both the effect size and statistical significance remain consistent. This indicates that the positive effect of being an electoral loser on support for referendums is robust, in line with H1 and the descriptive analyses of individual countries using one-tailed t-tests.

In addition, while we did not hypothesize a direct relationship between affective polarization and attitudes toward referendums, we find a small negative effect, which is statistically significant at the 0.001 level. However, we attribute this relationship to the interaction effect that we test in Model 3. Simply put, we believe that affective polarization (as hypothecized) has different effects on the relationship between being an electoral winner or loser and referendum attitudes. Therefore, the overall negative relationship between affective polarization and referendum attitudes is likely a reflection of the distribution of electoral winners and losers in the dataset. Nevertheless, recent studies have found a similar pattern – a small negative effect where polarized citizens are less inclined toward democratic innovations (van Dijk et al. Reference van Dijk, Turkenburg and Pow2023).

In Model 3, we include the interaction terms between affective polarization and being an electoral loser in the regression models. We hypothesized that affective polarization should have a positive effect on the winner-loser gap in attitudes toward referendums, which means that the difference in referendum support between electoral losers and winners should be larger for voters who are more strongly polarized. This is exactly what we find: the interaction term between affective polarization and being an electoral loser has a positive coefficient and is highly statistically significant (p<0.001). This confirms H2 and our expectation that affectively polarized voters show greater differences in their support for referendums, depending on whether they voted for a party in or out of government. The standalone coefficient for being an electoral loser becomes 0 in Model 3 and loses its statistical significance. Since this coefficient reflects the impact of scoring a 0 for affective polarization, this means that there is virtually no difference in referendum attitudes between electoral winners and losers when they are not affectively polarized.

To provide a clearer understanding of the interaction effect, we plot the predicted probabilities in Figure 1. We also overlay a histogram to show the distribution of affective polarization in the dataset, which offers a straightforward way to assess how different levels of affective polarization impact the winner-loser gap in referendum attitudes. This graph reveals that the moderating effect of affective polarization, as indicated in the regression models, is primarily driven by electoral winners. That is, electoral winners and losers indeed show nearly the same levels of support for referendums when affective polarization is low. However, as polarization increases, electoral winners become less supportive of referendums (though they remain above the neutral mid-point on average). By contrast, electoral losers maintain relatively stable attitudes toward referendums. Their support increases slightly with affective polarization, but the change is rather modest. Thus, the moderating effect of affective polarization on the winner-loser gap in referendum attitudes can be attributed largely to the decrease in support among electoral winners. The difference in support for referendums between electoral losers and winners becomes substantial at high levels of affective polarization, with the most polarized voters differing by approximately half a unit on the 1–5 scale. Accordingly, we conclude that H2a is confirmed, but we find no evidence for H2b.

Figure 1. Interaction effects on support for referendums, including 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Interestingly, our results suggest that referendum support among electoral losers is primarily driven by their structural position rather than their level of polarization. A ceiling effect may explain this: since referendum support among losers is already high, polarization leaves little room for further increases. Alternatively, while polarization intensifies in-group loyalty and out-group hostility, it may not shape losers’ strategic calculations in the same way as it does for winners. Regardless of how much they dislike the governing parties, losers consistently view referendums as a tool to influence policy from outside power. This contrasts with winners, for whom polarization increases defensiveness, making them less supportive of direct democracy.

Robustness Tests

To test the robustness of our results, we perform some additional analyses, with the full models available in the Appendix. First, instead of using a linear regression model, we replicated our analyses with ordered logistic models. This addresses potential criticism regarding our dependent variable, in particular that the 1–5 scale (from strongly disagree to strongly agree) should not be interpreted linearly (see Appendix B.1). The results of these models are nonetheless consistent with those obtained using linear regression.

Second, critical readers may argue that the gap in referendum support between electoral losers and winners is rather a reflection of their gap in satisfaction with democracy. As discussed earlier, the winner-loser gap in democratic satisfaction after elections is a well-documented phenomenon in the literature (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005). Therefore, we ran the same models and additionally controlled for satisfaction with democracy (Appendix B.2). Although the effect sizes indeed shrink visibly, the main effect of being an electoral loser, along with the interaction effect with affective polarization, remains positive (as hypothesized) and highly statistically significant (p<0.001). Thus, while part of the effect is indeed channelled through satisfaction with democracy, an independent effect persists between voters with the same level of democratic satisfaction.

Third, as discussed, we merged two variables to create our dependent variable of referendum support. To ensure that the results here are not driven by attitudes to only one of the two items, we conducted both the descriptive analysis and the fixed-effects regression analysis separately for each item. For both variables, we find very similar results (Appendix B.3–B.5). The effect of being an electoral loser, along with the interaction with affective polarization, exhibit comparable effect sizes and statistical significance throughout the analyses.

Fourth, there is ongoing debate in the literature regarding whether support for referendums is predominantly driven by voters of populist radical right parties (Bowler et al. Reference Bowler, Denemark, Donovan and McDonnell2017; Webb Reference Webb2013). Given that populist radical right parties often find themselves in opposition, higher support for referendums among electoral losers could simply be a reflection of this. We therefore reran our analyses and included a dummy for respondents who voted for a populist radical right party, based on the PopuList classification (Rooduijn et al. Reference Rooduijn, Pirro, Halikiopoulou, Froio, Kessel, Lange, Mudde and Taggart2024). While we indeed find that populist voters are significantly more supportive of referendums, it does not change our results in any meaningful way (Appendix B.6).

Fifth, in our main models, we coded abstainers as missing values. Some may argue that abstainers are also electoral losers. To address this, we replicated our models’ coding abstainers, in addition to voters who voted for an opposition party, as electoral losers. We again find substantively similar results, with directions of effects as well as significance levels unchanged (Appendix B.7).

Sixth, our cross-sectional design inherently raises questions about causality. While we cannot fully resolve this issue, we can account for it by controlling for two additional variables (Appendix B.8 and B.9) to assess the effects of more structural electoral loss. First, we add a binary variable that is coded 1 if voters were also electoral losers before the last election. Second, we add the parliamentary size of the party a respondent voted for into the models. Both variables have the expected effects: structural losers are even more supportive of referendums than one-time losers, while voters of larger parties are less supportive of referendums, most likely reflecting the larger size of governing parties. However, adding these variables does not change our main findings. We also run a final model (Appendix B.10) that includes all aforementioned control variables: satisfaction with democracy, populist radical right vote, structural electoral loss, and party size. Even with these additional controls, our main coefficients of electoral loss and its interaction with affective polarization remain unchanged.

Seventh, several countries in our sample are characterized by coalition governments. To account for this, we empirically test if there is a noticeable difference between voters of the largest coalition partner and voters of a junior coalition partner. It could be argued that voters of the largest coalition partner should witness stronger winner effects than junior coalition partners. We find, however, that the differences between both types of electoral winners are negligible (Appendix B.11)

Finally, we employed jackknife tests by replicating our analyses while excluding one country at a time from the regression models. This allows us to assess whether the results are driven by an important outlier. However, we found no meaningful changes in the coefficients of our key independent variables. We also used a more rigorous sensitivity analysis by analysing the results by country, where the direction of results is as expected in all countries (except for the region of Wallonia), and significance levels hold in most of the countries (Appendix B.12–B.15). Consequently, these additional tests reinforce confidence in the robustness of our results.

Conclusion

In this study, we examined how winning and losing elections shape citizens’ support for referendums. We theorized that electoral losers should be more supportive of referendums since they seek alternative avenues to power. Using cross-national survey data of thirteen European democracies, we found that citizens are significantly more likely to support referendums when they have voted for a party that ended up in the opposition. This finding aligns with earlier research on support for electoral reform in the USA, which similarly found that electoral losers are more likely to endorse the use of referendums (Bowler and Donovan Reference Bowler and Donovan2007; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Tolbert and Keller2010). More broadly, it speaks to voters’ instrumental considerations regarding alternative decision-making processes beyond general elections, a trend also observed in Europe (Pilet et al. Reference Pilet, Bedock, Talukder and Rangoni2023; Werner Reference Werner2020).

In addition, we demonstrated that the winner-loser gap in support for referendums is strongly moderated by affective polarization – the extent to which voters view their own party favourably while treating other parties and their supporters with hostility. More precisely, electoral winners become less supportive of referendums as their levels of affective polarization increase. Their emotional engagement with politics makes them protective of their party’s government, resulting in decreased support for an instrument that can bypass it. Conversely, electoral losers maintain consistent support for referendums regardless of their level of affective polarization. This finding is crucial because, even though the winner-loser gap in democratic satisfaction has been widely documented, the measure of voting for a party in or out of government is rather crude. We nuance the impact of the winner-loser gap on attitudes toward referendums, showing that there is virtually no gap in attitudes between electoral winners and losers who are not polarized.

To a certain extent, we believe that our findings identify three groups of voters in terms of referendum support. First, (long-term and short-term) electoral losers consistently support referendums, regardless of their level of polarization. This is in line with previous research (Bowler and Donovan Reference Bowler and Donovan2007; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Tolbert and Keller2010) in the American context and suggests that losing elections triggers a desire to influence politics beyond representative democracy. Second, electoral winners can be divided into two groups. On the one hand, non-polarized winners support referendums similarly to electoral losers. Their low level of polarization suggests a weaker attachment to their party and might, for some, even reflect political apathy or disenchantment with representative actors. As a result, they may view mechanisms that enhance direct influence, particularly at the expense of parties and politicians, positively. On the other hand, polarized electoral winners strongly identify with their preferred party in government and hold intense negative feelings toward other parties that are not in power. These voters are thus more motivated to support their government from outside interference, which is translated into lower support for alternative forms of decision making such as referendums.

These findings contribute to debates about the potential implications of affective polarization for democracy and democratic attitudes. More specifically, recent research suggests that affective polarization may weaken the accountability relationship between parties and voters (Ward and Tavits Reference Ward and Tavits2019), increasing voters’ willingness to tolerate undemocratic behaviour from their own party if it keeps them in power (Andrews and Huang Reference Andrews and Huang2024). Our results support this concern: strongly polarized election winners are more willing to shield their party from outside interference once in power, which can be problematic for democracy in the long term. Nonetheless, our findings only indicate an indirect effect. Further research is needed to unpack the precise role of affective polarization in undermining the willingness of voters to hold their own party accountable. Furthermore, it would be interesting to examine whether our results are unique to attitudes about referendums or also travel to other forms of democratic reform.

It is also important to mention that the winner-loser gap in satisfaction with democracy might be less alarming than it seems. Our results suggest that electoral losers, even when polarized, do not turn their back on democracy; if anything, they seek additional ways to engage and turn toward participatory forms of democracy. Concerns about the winner-loser gap should perhaps rather be focused on electoral winners instead (Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Smith, Moseley and Layton2023; Moehler Reference Moehler2009).

One key limitation of our study is the limited ability to establish causality. Whereas reversed causality seems less likely (that is, referendum support leads to losing elections), our research might suffer from omitted variable bias, where another non-measured variable is actually driving our results rather than losing elections and affective polarization. We have attempted to mitigate this issue by including a range of control variables, but future research should further scrutinize our findings with more causal designs. For example, the use of panel data seems a promising avenue for future research, as is often the case in the literature on the winner-loser gap. Panel designs would also address another limitation of our study: the possibility that respondents switched party affiliation since the last election. Because panel surveys are conducted closer to elections, they can help improve causal inference while also accounting for party-switching dynamics.

To conclude, our study contributes to the literature in three key aspects. First, we add to the body of research on public support for referendums and democratic innovations, which has primarily focused on stable determinants such as political attitudes or sociodemographic backgrounds (Coffé and Michels Reference Coffé and Michels2014; Gherghina and Geissel Reference Gherghina and Geissel2020; Már and Gastil Reference Már and Gastil2023; Schuck and de Vreese Reference Schuck and de Vreese2015). Our findings indicate that dynamic, instrumental factors related to election cycles can also play an important role in explaining support. Second, we contribute to the literature on the winner-loser gap, which has robustly established its existence (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005; Anderson and Guillory Reference Anderson and Guillory1997; Daoust and Nadeau Reference Daoust and Nadeau2023; Esaiasson Reference Esaiasson2011) but has largely overlooked its consequences. By affecting attitudes toward alternative democratic instruments such as referendums, we demonstrated that this gap is consequential for citizens’ democratic preferences yet dependent on the level of affective polarization. In other words, winning or losing elections influences people’s views on how democracy should work – especially when they are polarized – and whether the democratic status-quo, that is, representative democracy, should remain unchanged or be revised to allow alternative instruments based on the direct participation of citizens in decision making. Finally, we contribute to research on the political impact of affective polarization, particularly its effects on democratic attitudes (Janssen Reference Janssen2023; Kingzette et al. Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021; Wagner Reference Wagner2021). While this research agenda has only recently started to emerge, it has raised concern about the negative impact of affective polarization on democratic attitudes, especially among electoral losers. Our results suggest, however, that it is mostly electoral winners that are impacted by affective polarization.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123425000365.

Data availability

Replication data for this paper can be found in the Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/VECW81.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2024 Direct Democracy Workshop in Zürich. We would like to thank all the participants for their very useful discussion and feedback. We also thank the members of the POLITICIZE research team, Jean-Benoit Pilet, Sebastien Rojon, and David Vittori. Finally, we would like to thank the reviewers and editors of the British Journal of Political Science for their detailed comments and feedback, which greatly improved the quality of this article.

Financial support

This study has received financial support from the European Research Council (ERC Consolidator Grant) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 772695) for the CURE OR CURSE?/POLITICIZE project. Bjarn Eck acknowledges funding received from the FNRS.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this article.

Ethical standards

This study received ethical approval from the Data Protection Officer (N° R2019/001) and from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Philosophy and Social Sciences at the Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB).