At a March 2018 United Nations Security Council (UNSC) debate on improving peacekeeping efforts, Secretary-General Antonio Guterres expressed concern for the growing complexity of the UN’s peacekeeping operation (PKO) mandates. Speaking of the UN’s effort in South Sudan, Guterres stated that an abundance of operational tasks had crowded the mission’s mandate in much the same way that ornaments crowd the branches of a Christmas tree.

I urge Security Council members to sharpen and streamline mandates. Please put an end to mandates that look like Christmas trees. Christmas is over, and the United Nations Mission in South Sudan cannot possibly implement 209 mandated tasks. By attempting to do too much, we dilute our efforts and weaken our impact (United Nations 2018a).

Recent research also reveals a clear trend toward increasingly complex mandates (Lloyd Reference Lloyd2021). What is the consequence of this trend?

While Guterres’s primary expressed concern was that mandate complexity inhibits success, we suspect complex mandates have additional consequences for the UN’s ability to outfit its PKOs. Complex mandates change states’ incentives to contribute peacekeeping personnel, and we argue that these mandates particularly incentivize non-democratic states to increase their personnel contributions. Non-democratic troop contributors are motivated by process benefits such as reimbursement (Boutton and D’Orazio Reference Boutton and D’Orazio2020), training (Albrecht Reference Albrecht2020), and reputation (Levin Reference Levin2023). Complex mandates extend the scope and duration of peacekeeping, creating greater opportunity for process benefits to accumulate. We therefore expect that non-democratic regimes are uniquely encouraged to contribute UN peacekeeping personnel in the face of increasingly complex mission mandates.

While some work argues that democracies have retreated from peacekeeping, research largely fails to point out that non-democracies have become more enthusiastic contributors. As the ‘Christmas tree’ expansion of mandates has grown over time, increasing commitments by non-democracies have led to a gap in the size of contributions from democratic and non-democratic countries.

We begin by describing trends in mandate complexity as well as contributions to peacekeeping. We then discuss member state incentives to contribute peacekeeping personnel, arguing that non-democratic member states are motivated more by process benefits and will contribute more personnel relative to democratic states as mandate complexity increases. We test this expectation on a global dataset of personnel contributions and PKO-mandated tasks from 1990–2022. Since increasing mandate complexity coincides with other relevant global trends, we present several tests to show that even when accounting for time trends, there is a clear correlation between mandate complexity and the size of non-democratic contributions.

The results have implications for peacekeeping effectiveness and the UN’s ability to pursue a liberal international order. Large contributors of peacekeepers often demand agency in what peacekeepers are asked to do (Tull Reference Tull2023). For example, as China has become a top-five contributing country, it has begun to ask for human rights to be removed from mandates (Coleman and Job Reference Coleman and Job2021). Recent work indicates that UN PKOs can enable authoritarian governance (von Billerbeck et al. Reference von Billerbeck2025). Moreover, regional and ad hoc coalitions focusing on counterterrorism and counterinsurgency are increasingly supplanting UN operations that promote liberal values (Karlsrud Reference Karlsrud2023). If UN mandates are increasingly implemented by non-democratic personnel, the UN’s prospects for promoting democratic norms and values through peacekeeping may be further undermined.

Trends in Mandate Complexity and Peacekeeping Participation

Mandates have become increasingly complex as the number of tasks assigned to PKOs has grown substantially (Oksamytna and Lundgren Reference Oksamytna and Lundgren2021). Figure 1 reports the average number of tasks assigned to PKOs over time, using updated information from the Tasks Assigned to Missions in their Mandates dataset (Lloyd Reference Lloyd2021). Tasks include broad responsibilities such as monitoring a ceasefire or protecting human rights and are often teamed with more narrowly defined subtasks, such as monitoring a buffer zone.

Figure 1. Average Number of Tasks Mandated to UN PKOs by Year.

Figure 1 reveals that, from the end of the Cold War, PKOs have been assigned an increasing number of tasks on average. For example, from 2009 to 2010, the United Nations Organization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUC) was assigned thirty-three total tasks, including establishing good offices, protecting women and children, assisting with security and justice sector reform, and monitoring the disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) of combatants. Moreover, the activities in which peacekeepers engage have become more comprehensive and complex, moving beyond traditional peacekeeping. Powerful democratic members of the UNSC are the most common ‘penholders’ in drafting peacekeeping mandates (Oksamytna and Lundgren Reference Oksamytna and Lundgren2021). As such, peacekeeping tasks reflect the political objectives of these democracies. Mandated tasks expand even further as UNSC members follow suggested additions from the Secretariat and calls for more assertive peacekeeping reform, like those of the Brahimi Report (United Nations 2000). The post-Cold War era is thus characterized by an increasing number of PKO deployments that are increasingly complex undertakings.

Implementing mandated tasks is not easy, can be costly, and comes with considerable risk to peacekeepers. Since 1991, 56 per cent of PKOs were deployed to countries where violence was ongoing (Hultman, Kathman and Shannon Reference Hultman, Kathman and Shannon2019). PKOs are deployed to locations where executing complex mandates is made difficult by instability. It is in these dangerous environments that member states must deploy personnel in order to sufficiently outfit PKOs in pursuit of UN objectives. Personnel deployments are voluntary. They are not directed by institutional requirements of any sort. Historically, peacekeepers were largely provided by Western consolidated democracies (Daniel and Caraher Reference Daniel and Caraher2006; Lebovic Reference Lebovic2004). This fact supported a general perception that member states use peacekeeping as a way to support a liberal international order, spreading democratic norms and institutions. Today, however, peacekeepers are more commonly provided by non-democracies like Ethiopia, Bangladesh, and Rwanda, and it is uncommon for democracies to be among the top contributors.

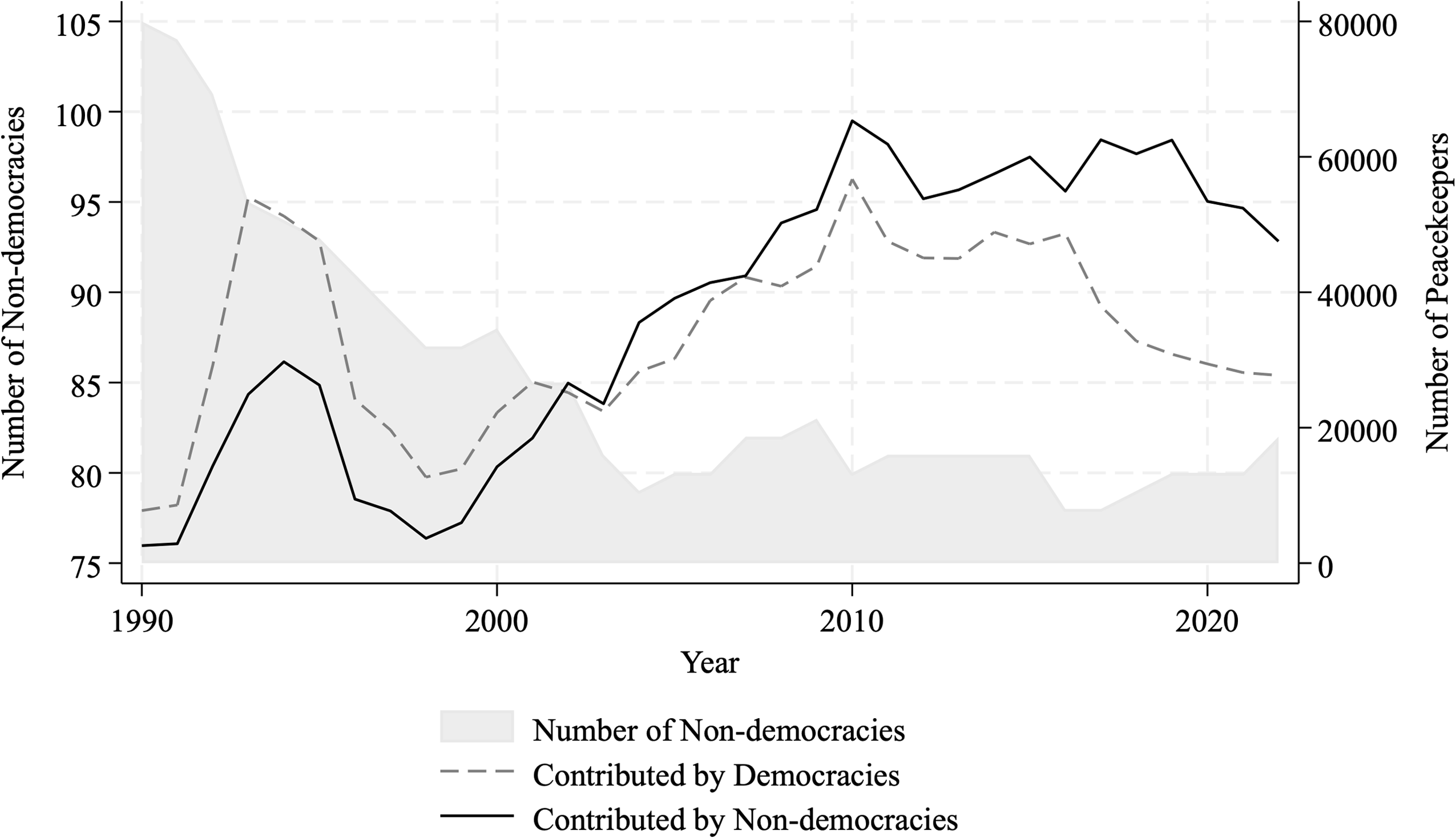

This has led some to argue that to avoid dangerous operational efforts, democracies have retreated from peacekeeping (Duursma and Gledhill Reference Duursma and Gledhill2019). However, the retreat of democracies is inaccurate. The demand for peacekeepers exploded after the Cold War, as the global number of civil wars grew dramatically (Davies et al. Reference Davies, Pettersson and Öberg2022). The UN responded with an increase in PKOs, increasing demand for personnel and putting greater pressure on members to contribute. While their contributions ebb and flow somewhat, democracies have consistently contributed blue helmets to meet global demand. Instead, the most significant change is that non-democracies have greatly expanded their commitments to peacekeeping. As shown in Figure 2, non-democratic contributions have exceeded democratic contributions every year since 2002, even as the pool of non-democracies has declined in the post-Cold War era.

Figure 2. Number of Peacekeepers Contributed by Non-democracies and Democracies.

Thus, providing peacekeepers is no longer primarily the enterprise of democracies. Rather, non-democratic states disproportionately bear the burden of peacekeeping in pursuit of liberal objectives. We suggest that this transformation is a product of the differential motivations that democratic and non-democratic states have for contributing peacekeepers in the face of increasingly complex mandates.

Member State Motivations for Peacekeeping Contributions

Complex mandates can influence the willingness of states to contribute personnel to UN operations. Research suggests that member states are motivated by the pursuit of tangible benefits, like financial and economic rewards, that derive directly from the process of participation (Passmore et al. Reference Passmore, Megan Shannon and Hart2018). We argue that democracies and non-democracies are driven by different incentives for providing peacekeepers (Levin Reference Levin2023), as benefits accrue to democracies and non-democracies differentially during peacekeeping.

‘Process benefits’ are gains realized by member states in the course of peacekeeping. Rather than rewards contingent upon peacekeeping success, process benefits are continually earned while peacekeeping personnel are deployed. A process benefit often mentioned in the literature is the monthly personnel reimbursement earned by member states for every deployed blue helmet (Gaibulloev et al. Reference Gaibulloev, Sandler and Shimizu2009). Additional process benefits include field experience and equipment training, which are valuable to contributors in need of a ready, capable military for which domestic resources are scarce (Albrecht Reference Albrecht2020).Footnote 1 Further, contributors obtain process benefits from deploying dangerous military contingents that threaten political instability at home (Kathman and Melin Reference Kathman and Melin2017). Deploying personnel to PKOs can allow member states to improve their status in the international community, even ‘whitewashing’ their human rights reputations to avoid sanction (Levin Reference Levin2020).

Non-democratic Regimes, Process Benefits, and Motivation for Peacekeeping Deployments

Delineating process benefits is important for understanding democratic and non-democratic contributions because different regimes’ constituent bases gain from the process of peacekeeping differently. As the most common penholders in writing operation mandates, democratic member states often include such mission goals as democratic reforms and human rights protections, including various associated tasks. Yet, as mandated tasks mount, the time and energy necessary to pursue them with peacekeeping personnel also mount. Such demands may be challenging to meet in democracies. Democratic leaders are dependent upon the mass public for their political futures, and research has shown that extended foreign engagements can cause democratic constituencies to turn against them (Gartner and Segura Reference Gartner and Segura1998). This can make substantial personnel deployments less attractive for democracies as mandate complexity increases.

By contrast, non-democracies have narrower constituencies that commonly include national militaries. Unlike consolidated, liberal democratic regimes with institutionalized civil-military relations, the military in non-democracies is often not subservient to civilian rule. Thus, the military is generally a significant constituent element of the ‘selectorate’ for choosing and replacing leaders (cf. Bueno de Mesquita Reference Bueno de Mesquita2003). Political leaders in non-democracies are, therefore, more sensitive to the interests of the military, given the military’s ability to affect a leader’s hold on power.

The process benefits inherent in continued peacekeeping engagements, consequently, are a more powerful motivator for participation by the narrow segments of political power in non-democracies. Research points to key peacekeeping process benefits for contributing states’ militaries. Deployed soldiers can receive higher wages from UN reimbursement pay and improve the military’s status domestically (Wyeth Reference Wyeth2018). Military units get field experience and training with advanced equipment that is often in short supply at home. These process benefits can also serve to expand the military’s role in domestic politics (Copetas Reference Copetas2007).

Domestically, elites benefit because financial revenues from peacekeeping are fungible and can be used to support repression to solidify their rule (Levin et al. Reference Levin, MacKay and Nasirzadeh2016). Internationally, benefits come in the form of reputation building that diverts foreign attention away from a contributor’s human rights abuses (Levin Reference Levin2020). These benefits mount and are sustained so long as contributing states maintain their deployments. It is reasonable to believe that non-democracies are more fully motivated by these process benefits relative to democracies. The greater the commitment and the more time necessary for fulfilling mandates, the greater are the prospects for non-democracies to profit from the process benefits available through participation in peacekeeping operations.

This is important because as operational tasks mount, mandates become more complex, making it more difficult for PKOs to achieve success (Blair et al. Reference Blair, Di Salvatore and Smidt2022). A larger number of mandated tasks increases the list of objectives to be satisfied. This requires more time and resources via extended, substantial personnel deployments. Increased mandate complexity thus increases process benefits. As non-democratic member states are motivated by process benefits, complex mandates should be associated with greater financial rewards, extended opportunities for training with advanced technologies and military equipment, and more meaningful field experience. These process benefits advantage important domestic constituencies in non-democratic states. This incentivizes larger personnel deployments, especially given the task requirements. For example, a smaller contingent of peacekeepers may be insufficient to monitor borders or assist with DDR. Modern operations with many mandated tasks require large, mobile, and professional troop battalions (Williams Reference Williams2020). Larger personnel contributions reap greater financial, training, and experience benefits and can even more fully whitewash a non-democratic member state’s own domestic abuses.Footnote 2

Given the above reasoning, we argue that the increased availability of process benefits associated with complex mandates incentivizes non-democracies to make greater personnel contributions to UN PKOs. As an example, when MONUC received a significantly more complex mandate by the end of 2004, Pakistan (a non-democratic UN member country) increased its contribution from 1,135 to 3,570 troops. While the largest troop contributor, India, was still a democracy at the time, Pakistan stood out by tripling the number of troops it deployed to MONUC following the revised mandate. We hypothesize that this reflects a more general pattern among troop contributing countries:

As PKO mandate complexity increases, non-democratic contributors will make relatively larger personnel contributions.

Research Design

We test the hypothesis with data that includes all country contributions to UN PKOs for the period 1990–2022. The unit of analysis is the PKO-potential contributor-year. A potential contributor is any UN member state.

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable is the number of peacekeepers contributed by a country to a particular operation, ranging from 0 to 6,364 (Kathman Reference Kathman2013). The distribution is over-dispersed. We utilize a negative binomial model to analyze the data since this model accounts for heterogeneity and contagion in over-dispersed data (Long Reference Long1997).

Primary Independent Variables

To test the hypothesis, we begin with a variable that counts the number of mandated tasks assigned to a mission in each month (Lloyd Reference Lloyd2021). We then average the number of mandated tasks over a year, resulting in Mandated tasks, which range from 1 to 33. As more tasks are mandated to a mission, the mission becomes more complex.Footnote 3 According to the hypothesis, mission complexity should incentivize non-democracies to make larger contributions. This suggests an interaction effect, so we include Non-democracy*tasks in the model, where Non-democracy is a dummy variable coded 1 for all countries scoring lower than 0.5 on the V-Dem electoral democracy index (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge2024).

Control Variables

We control for a number of factors shown to influence country peacekeeper contributions, and that may confound the effect of our interaction variable. First, we include a country’s logged GDP Per Capita (World Bank 2019), as poorer states may contribute more peacekeepers for reimbursement benefits. We control for logged Population, as states with large populations may have large personnel resources (World Bank 2019). Similarly, we account for the number of military personnel relative to the state’s population, Military Personnel/Population, using data from the Global Militarization Index (Bayer and Rohleder Reference Bayer and Rohleder2022). Next, we control for whether the potential contributor has a Shared region with the PKO host state, according to the Correlates of War State System Membership Data (2017) as well as Colonial ties (Duursma and Gledhill Reference Duursma and Gledhill2019). Both may make a country more likely to contribute.

We also control for whether the country is a Permanent five (P5) member of the UNSC, as P5 members are less likely to contribute. We control for whether each mission has been given Chapter VII mandate authorization and the number of Mission fatalities suffered in the previous year (United Nations 2018b), as violent environments may make countries less willing to contribute. We also account for whether the contributor country has an ongoing Armed conflict as recorded by the Uppsala Conflict Data Programme (Davies et al. Reference Davies, Pettersson and Öberg2022), expecting those countries to be more reluctant contributors. Finally, we control for temporal dynamics, including a count of years starting in 1990, as well as squared and cubic terms.

Results and Discussion

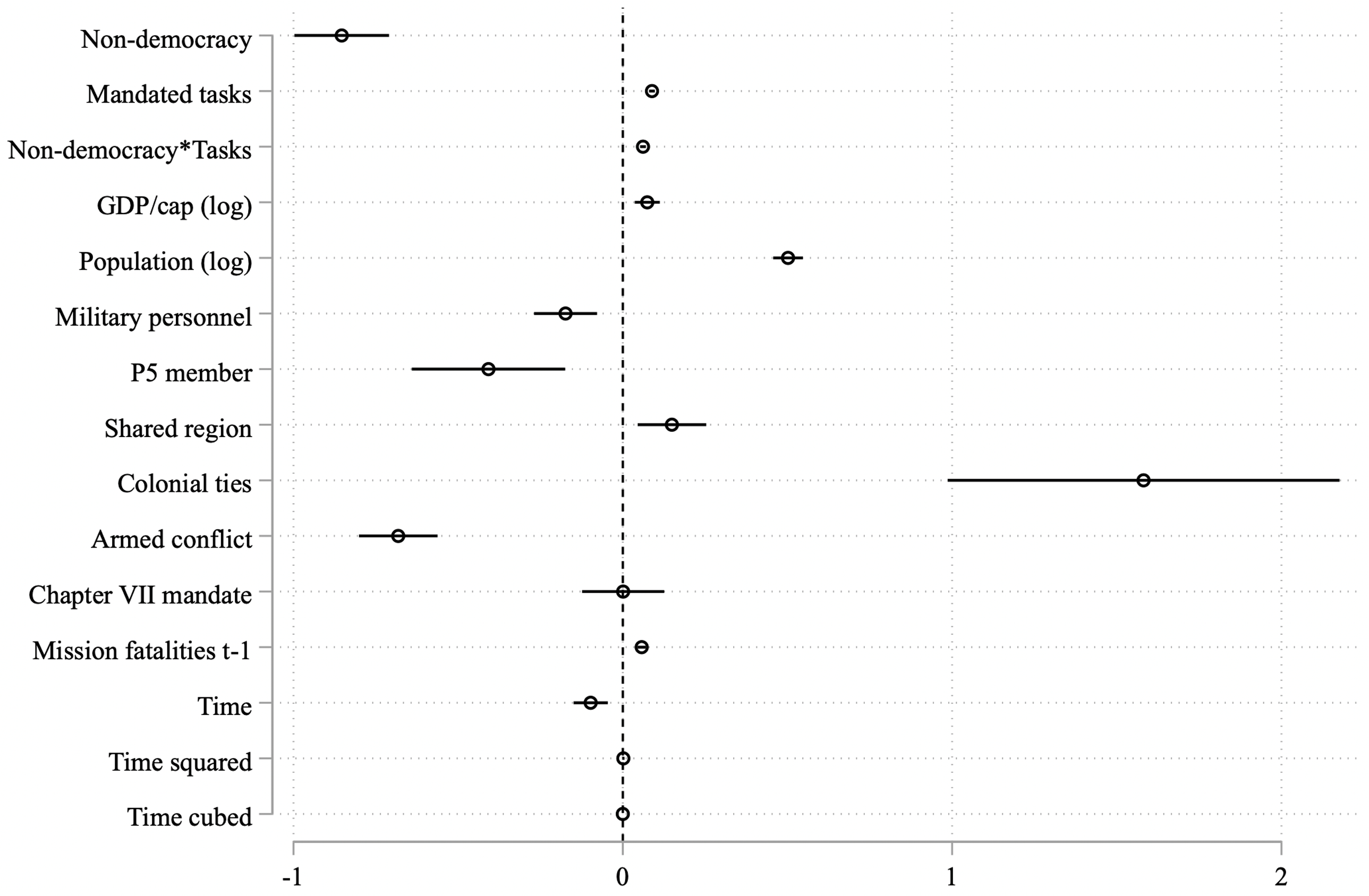

The full results from the analysis are reported in the Appendix. Figure 3 shows a coefficient plot for the main model, including point estimates and 95 per cent confidence intervals. The interaction term is positive, indicating that non-democratic UN member states make larger contributions as missions become more complex.

Figure 3. Effect of Mandate Complexity and Regime Type on Personnel Contributions, 1990–2022.

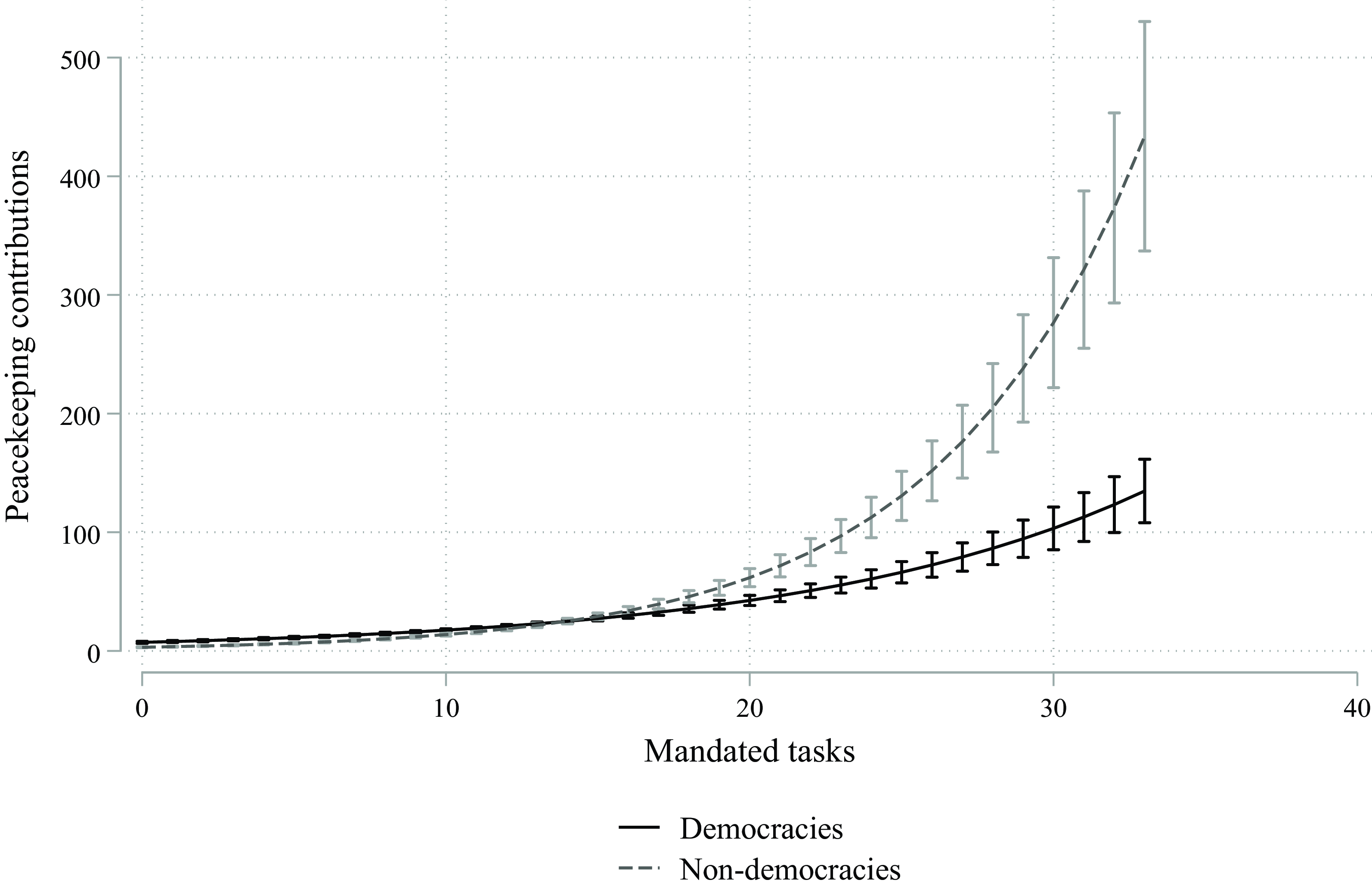

Figure 4 plots the interaction effect. As mandate complexity increases, non-democracies increase their peacekeeper contributions much more than democracies. The difference between them is significant at eighteen or more mandated tasks. In highly complex missions with thirty or more tasks, the predicted size of non-democratic contributions is between 180 and 220 per cent larger than democracies. This is an extraordinary increase, as these are the average effects for all potential contributors.

Figure 4. Interaction Effect of Non-democracy and Mandate Complexity.

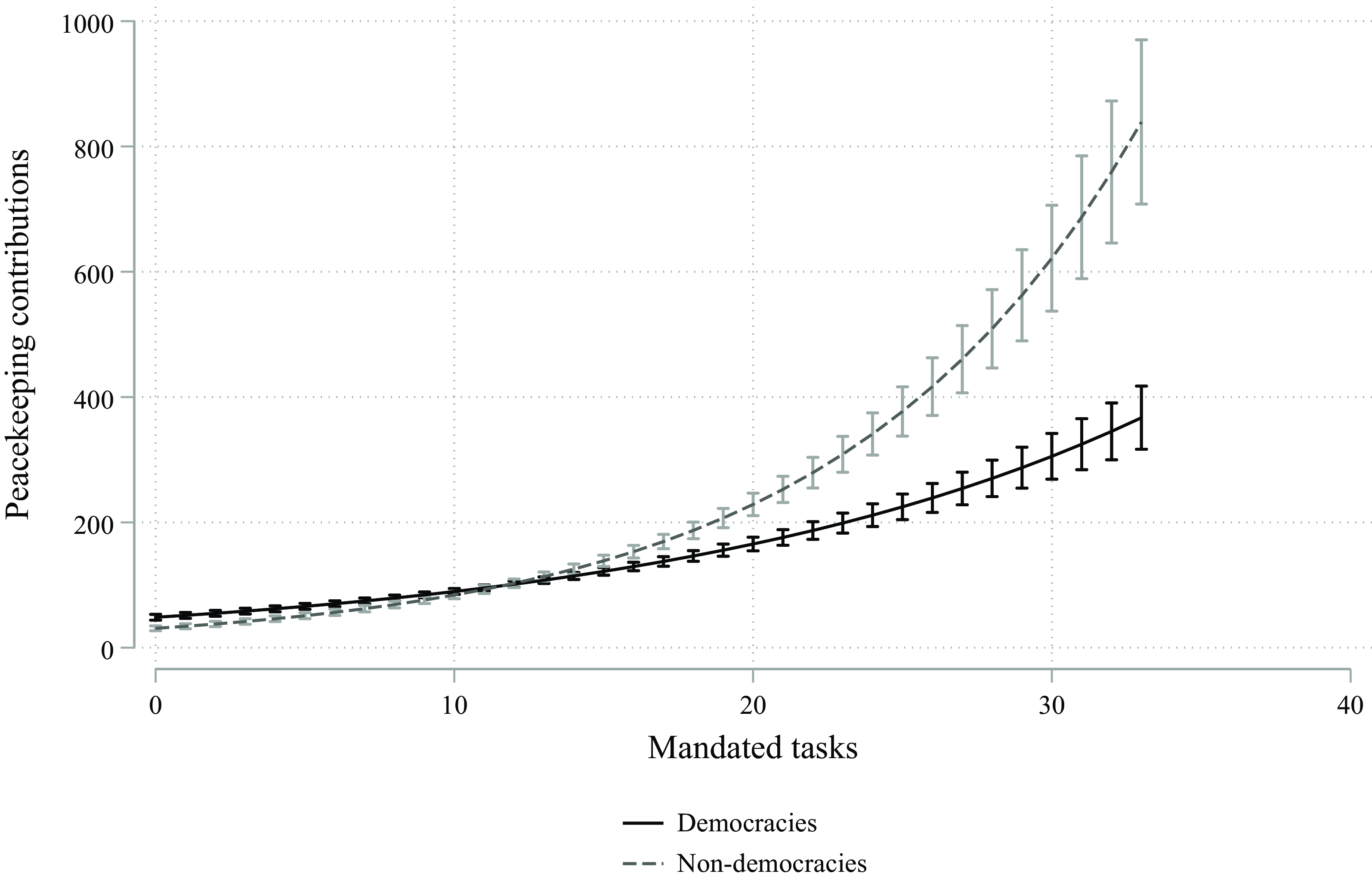

In Figure 5, we limit the sample to actual contributors, assessing contribution size among countries that have deployed peacekeepers at a previous point in time to a peacekeeping operation. We find that non-democracies contribute twice as many peacekeepers as democracies in complex missions, as non-democracies more substantially increase contributions as mandates become complex.

Figure 5. Interaction Effect of Non-democracy and Mandate Complexity: Contributor Sample.

The Appendix presents the results of robustness checks. First, we address a potential concern about differentiating the effect of mandate complexity from more general time trends using year fixed effects (Table A2, Models 1 and 2). The result for the interaction term is unaffected, providing confidence that non-democracies are more willing to contribute to missions as tasks increase. We also split the sample into pre- and post-2000 to ensure the results are unaffected by a parallel trend since 2000 (Table A2, Models 3 and 4). We find a significant interaction effect in both periods, supporting the theorized mechanism.

Second, if states first decide whether to make any contributions at all to a mission and thereafter decide how many troops to contribute, a Heckman selection model can capture this two-stage decision process for all potential contributor states (Table A3). The results are similar, reporting a positive coefficient for the interaction of non-democracy and mandate complexity. Additionally, the zero values in contribution observations could be driven by different processes relative to non-zero values. In other words, some states may never contribute while others may be likely to contribute but do not in a given year. Employing a zero-inflated negative binomial model, we simultaneously estimate the likelihood of a non-zero contribution and the contribution size for all potential contributor states (Table A4). Again, the results are consistent.

Third, we include alternative specifications of independent variables (Table A5). Model 1 uses Polity to measure nondemocracy, denoting countries scoring 6 and below on the Polity scale (Marshall and Gurr Reference Marshall and Gurr2020). We find a significant interaction effect of non-democracy and mandate complexity. Next, we drop military personnel, given the large number of missing values. We also measure mission fatalities at time t, to avoid dropping the first year of each mission. In both specifications, the results are very similar.

The analyses suggest that complex mandates incentivize personnel contributions from non-democracies for peacekeeping’s process benefits. Williams (Reference Williams2020) notes that the UN’s liberal peace agenda requires larger, more robust operations. We have shown that the UN is increasingly relying on its illiberal members to pursue this agenda.

Conclusion

This paper shows that the increasing complexity of UN peacekeeping mandates comes with increasing peacekeeper contributions by non-democratic states. This changing nature of peacekeeping contributions has profound implications for policymakers. Democracies are often penholders in writing mandates. What does it mean when democracies rely on non-democracies to execute their agenda? This dynamic may undermine the effectiveness of peacekeeping in promoting liberal values (Duursma and Gledhill Reference Duursma and Gledhill2019, 1179). More concerning is the prospect of peacekeeping becoming a tool of Western imperialism (Cunliffe Reference Cunliffe2013). Our findings cohere with research showing that peacekeepers from non-white countries tend to perform more dangerous tasks than peacekeepers from majority white countries (Oksamytna and von Billerbeck Reference Oksamytna and von Billerbeck2024; Karlsrud and Novosseloff Reference Karlsrud and Novosseloff2020). It seems that the UN increasingly relies on non-democracies to do the dangerous work of peacekeeping. This unequal division of labour should be taken seriously.

One might also reflect on recent challenges to UN peacekeeping in light of these findings. Thousands of Malians protested the peacekeeping force in May 2023 (Al Jazeera Reference Jazeera2023), and it eventually withdrew at the end of the year. The UN’s Congo mission has also been asked to withdraw from South Kivu and eventually leave the country completely. Both operations were perceived as ineffective by the populations they sought to protect, with exceptionally low levels of support (Trithart Reference Trithart2023). We know that peacekeeping composition is closely connected to peacekeeping effectiveness in various ways (Bove, Ruffa and Ruggeri Reference Bove, Ruffa and Ruggeri2020). The UN must balance the willingness of countries to contribute with the effectiveness of contributed personnel.

These withdrawals are indicative of Williams’s (Reference Williams2020) peacekeeping trilemma, where the UN tries to pursue broad mandates while minimizing peacekeeper casualties and maximizing cost-effectiveness. Williams argues that it is unlikely the UN can achieve all three at once. Indeed, the operations in Mali and the Congo are cautionary tales of the difficulty associated with heavily mandated operations. Our findings suggest that one way the UN tries to balance these objectives is to rely on personnel deployments from non-democratic members. These members engage in continued deployments to reap the process benefits of peacekeeping. But their interests may conflict with those of democratic member states who support PKO outcomes of local democratic progress, regional stability, and the maintenance of the liberal international order. What are the consequences of this tension? What does it mean for UN peacekeeping effectiveness and its future deployments? The UN must grapple with these questions, as they are inherent elements of the increasing reliance upon illiberal members for perpetuating the institution’s liberal peacekeeping agenda.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123425000316.

Data availability statement

Replication data for this paper can be found at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/9B1SKJ.

Acknowledgements

We thank participants at the Conditions of Violence and Peace brownbag series at the Peace Research Institute Oslo, the International Development speaker series at the Institute for Behavioral Science at CU Boulder, the Conflict Management in a Regional Context workshop at the Peace Science Society International 2022 meeting, and the Jan Tinbergen European Peace Science Conference 2023.

Financial support

This work was supported by the United States Fulbright Association (MS) and the Swedish Research Council (LH, award number 2018-00835 and award number KAW 2018.0455).

Competing interests

No competing interests to disclose.