1. The reconstruction of tense vowels in Tangut

Nishida (Reference Nishida1964) first proposed that the Tangut rhymes in what is traditionally called the “first minor cycle” had a specific contrast in sound quality with other rhymes.Footnote 2 Based on Chinese and Tibetan transcriptions of Tangut, he posited that these rhymes could be reconstructed with “tense vowels (はり母音)”, as opposed to “lax vowels (ゆるみ母音)”. This view is supported by Wang (Reference Wang1982: 3–4), who suggested that the absence of fanqie spelling connections between the rhymes in the “first minor cycle” and other minor cycles could be attributed to their “laryngeal constriction (緊喉元音)”, equivalent to Nishida's “tense vowel”. Wang (Reference Wang1982) further deemed that his proposal aligned well with relevant phenomena found in Lolo-Burmese languages. The reconstruction of tense vowels has received wide acceptance ever since, reused by some of the most influential Tangutologists (Arakawa Reference Arakawa and Hill2012, Reference Arakawa2014; Gong Reference Gong1999; Li Reference Li1997).

Gong (Reference Gong1999) observed that a considerable number of word pairs in Tangut exhibit alternation between tense and lax vowels. For instance, the two members in the pair ![]() 1475 bji1 “to be thin” and

1475 bji1 “to be thin” and ![]() 1789 bjị1 “to make thin” are not only semantically related but also distinguished solely by vowel tensing. This observation leads to the hypothesis that at least some tense vowels in Tangut result from morphological operations, which Gong (Reference Gong1999) identified as having four functions, summarized in Table 1. By analysing internal and external evidence, Gong (Reference Gong1999: 550) proposes that the phonological origin of vowel tensing in Tangut is an old sibilant pre-initial *s.Ci- (where Ci represents the initial consonant of a syllable).

1789 bjị1 “to make thin” are not only semantically related but also distinguished solely by vowel tensing. This observation leads to the hypothesis that at least some tense vowels in Tangut result from morphological operations, which Gong (Reference Gong1999) identified as having four functions, summarized in Table 1. By analysing internal and external evidence, Gong (Reference Gong1999: 550) proposes that the phonological origin of vowel tensing in Tangut is an old sibilant pre-initial *s.Ci- (where Ci represents the initial consonant of a syllable).

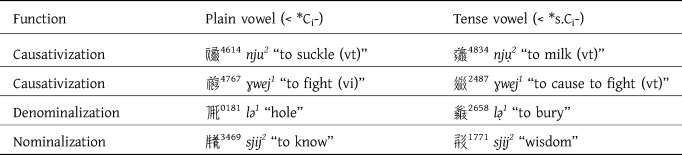

Table 1. Functions of Tangut vowel tensing according to Gong (Reference Gong1999)

Gong's seminal work, although widely accepted, still leaves many instances of tense vowels in Tangut unexplained. For instance, Jacques (Reference Jacques2014) demonstrates, through the examination of cognates shared between Tangut and modern Gyalrongic languages, that tense vowels in Tangut may also have originated from pre-initials that are intrinsic components of lexical roots (e.g. the numeral “ten”: Tangut ![]() 1084 ɣạ2 :: Geshiza Horpa zɣa :: Japhug sqi). On the other hand, tense vowels involving morphological functions have different origins, as evidenced by the causative/denominalizing *S- and nominalizing *S-, which clearly come from distinct sources. This point highlights the eroded features of Tangut, wherein tense vowels represent a merger of different morphological functions and different pre-initial consonants.

1084 ɣạ2 :: Geshiza Horpa zɣa :: Japhug sqi). On the other hand, tense vowels involving morphological functions have different origins, as evidenced by the causative/denominalizing *S- and nominalizing *S-, which clearly come from distinct sources. This point highlights the eroded features of Tangut, wherein tense vowels represent a merger of different morphological functions and different pre-initial consonants.

Building upon the previous hypothesis that vowel tensing results from the transphonologization of pre-initial elements, this paper proposes new origins of Tangut tense vowels in terms of nominal morphology, specifically a collective prefix *S- and a compound linker *-S-. It integrates the internal evidence from the study of Tangut textsFootnote 3 with comparative data from modern Sino-Tibetan languages, particularly from modern West Gyalrongic languages.Footnote 4

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 outlines the reconstruction conventions employed in this paper. Sections 3 and 4 present Tangut internal evidence supporting the existence of a collective prefix *S- and a compound linker *-S-, respectively. Both morphemes left only a few traces in Tangut, pointing to once-productive morphological processes which are crucial for reconstructing regular morphological processes in historical linguistics (Meillet Reference Meillet1925). Drawing on comparative data from Sino-Tibetan languages, Section 5 demonstrates that the collective *S- may represent an ancient inherited morphological process, while the compound linker *-S- emerged as a stage of morphological merging in West Gyalrongic. These findings not only contribute to the reconstruction of Tangut morphology but also shed light on the origins of compounding morphology in Sino-Tibetan, an area that remains understudied.

2. Conventions of Tangut and Pre-Tangut reconstructions

Since both Tangut and Pre-Tangut forms are used in the present paper, it is necessary to elucidate the conventions adopted for these reconstructions. Tangut forms are provided with IPA transcriptions based on Gong's (Reference Gong, LaPolla and Thurgood2003) reconstruction and are referenced by their corresponding numbers in the Tangut–Chinese Dictionary (Li Reference Li1997).

Pre-Tangut forms generally follow the reconstruction by Jacques (Reference Jacques2014) and are preceded by an asterisk *. Uncertain phonetic values are indicated with square brackets [ ], following Baxter and Sagart (Reference Baxter and Sagart2014). Periods, as in *Cə.Ci-, indicate a non-morphological separation between a pre-initial element and an initial. Hyphens after a pre-initial element indicate that it is considered a prefix.

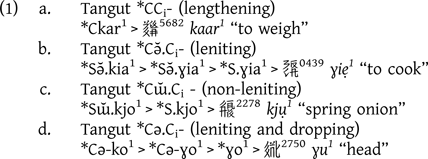

The treatment of initial lenition in Pre-Tangut follows Lai (Reference Lai2023; Reference Lai2024), who proposes that the occurrence of lenition depends on the syllabicity of the pre-initial element (including pre-initial consonants and pre-syllables) and distinguishes four types of Pre-Tangut pre-initial elements.

First, non-syllabic pre-initial consonants, noted as *CCi- (without the period to differentiate them from the *S.Ci- consistently used in this paper), yield long vowels in Tangut. Second, syllabic pre-initials *Cə̆.Ci- yield various phonation types, including tensing, rhoticizing and labial medializing, and result in initial lenition. Third, syllabic pre-initials *Cɯ̆.Ci- yield the same phonation types but without initial lenition. Fourth, pre-initials with a neutral vowel Cə.Ci- cause lenition before dropping entirely. Note that the vowel distinction in the reconstructed presyllables represent pure phonological contrasts rather than actual phonetic values. See (1) below for distinctive examples of these four pre-initial types in Tangut.

Since the second type *Cə̆.Ci- (in 1b) and the third type *Cɯ̆.Ci- (in 1c) both transphonologize into tense vowels, they can be reconstructed as *S[ɯ̆/ə̆].Ci-. For the sake of brevity, the distinction between *-ə̆ and *-ɯ̆ in the vowel tensing pre-initial elements will be mentioned only when necessary. In most cases, we unify our notation with a simple *S.Ci- when referring to the vowel tensing pre-initials in Pre-Tangut, corresponding to the third stage in (1b) and the second stage in (1c), while keeping *Cə.Ci- as the pre-syllable disappeared in Tangut.

3. Collective prefix *S-

In Tangut, some compounds have initial syllables with a tense vowel, which may originate from a compound initial element *S-. This element undergoes transphonologization, resulting in a tense vowel in the subsequent syllable, as illustrated in (2).

(2) *S-CV-CV > CṾ-CV

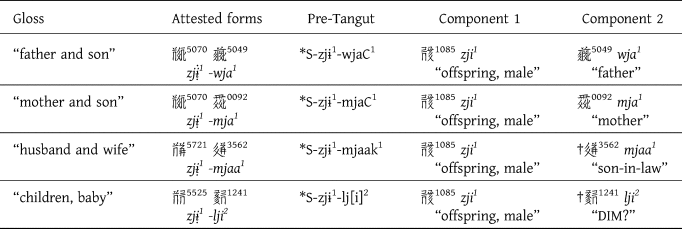

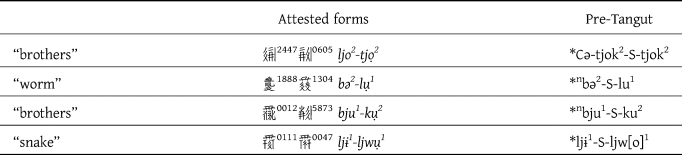

In some cases, it is expected that the compound initial *S- is not an intrinsic part of the root but rather a prefix used to derive collective nouns. The four compounds listed in Table 2 are among the few remaining traces of this collective morphology in Tangut. At the synchronic level, the *S- collective prefix has become lexicalized as an inseparable component.

Table 2. Traces of compound initial *S- in Tangut

Note: the symbol

* represents reconstructed forms,

† forms without unbound attestation, [ ] uncertain phonetic value. The lenited consonants z- and w- are retailed in Pre-Tangut forms to aid in readability.

The first component of the four compounds listed in Table 2 shares the same phonological form, zjɨ̣¹, which is etymologically related to ![]() 1085 zji1 (Pre-Tangut *zja) “son, offspring, male”. The form

1085 zji1 (Pre-Tangut *zja) “son, offspring, male”. The form ![]() 1085 zji1 reflects the Proto-Gyalrongic etymon for “offspring, male” and corresponds regularly to tə-tsa in Cogtse Situ, tə-ziɛ̂ in Bragbar Situ, and zî in Siyuewu Khroskyabs. The vowel alternation -ji :: -jɨ̣ observed between

1085 zji1 reflects the Proto-Gyalrongic etymon for “offspring, male” and corresponds regularly to tə-tsa in Cogtse Situ, tə-ziɛ̂ in Bragbar Situ, and zî in Siyuewu Khroskyabs. The vowel alternation -ji :: -jɨ̣ observed between ![]() 5070/

5070/![]() 5721/

5721/![]() 5525 zjɨ̣¹ and

5525 zjɨ̣¹ and ![]() 1085 zji1 is explained by two morpho-phonological processes.

1085 zji1 is explained by two morpho-phonological processes.

First, the rhyme -ji in the base form ![]() 1085 zji1 shifts to a weakened sound -jɨ when occurring in the bound state, i.e. as the non-final component of a compound. This vowel alternation pattern is regular in Tangut and is also found with other compounds, such as

1085 zji1 shifts to a weakened sound -jɨ when occurring in the bound state, i.e. as the non-final component of a compound. This vowel alternation pattern is regular in Tangut and is also found with other compounds, such as ![]() 4669

4669![]() 2541 bjɨ1-dzjwo2 (below-people) “servant” (with the first component

2541 bjɨ1-dzjwo2 (below-people) “servant” (with the first component ![]() 4669 bjɨ1 based on

4669 bjɨ1 based on ![]() 3791 bji2 “below”), as well as in reduplication, e.g.

3791 bji2 “below”), as well as in reduplication, e.g. ![]() 4669

4669![]() 3791 bjɨ1-bji2 “below” (Gong Reference Gong1993; Jacques Reference Jacques2014: 262; Wei Reference Wei2022).

3791 bjɨ1-bji2 “below” (Gong Reference Gong1993; Jacques Reference Jacques2014: 262; Wei Reference Wei2022).

Second, the alternation between the lax vowel -ji and the tense vowel -jɨ̣ is explained by the transphonologization of the compound initial *S- “collective prefix”, as explained in (2).

The four collective compounds in Table 2 can be classified into two categories based on their semantics. The first category includes ![]() 5070

5070 ![]() 5049 zjɨ̣1 -wja1 “father and son”,

5049 zjɨ̣1 -wja1 “father and son”, ![]() 5070

5070 ![]() 0092 zjɨ̣1 -mja1 “mother and son”, and

0092 zjɨ̣1 -mja1 “mother and son”, and ![]() 5721

5721 ![]() 3562 zjɨ̣1 -mjaa1 “husband and wife”, which are collectives representing social relations. The second category includes

3562 zjɨ̣1 -mjaa1 “husband and wife”, which are collectives representing social relations. The second category includes ![]() 5525

5525![]() 1241 zjɨ̣1-lji2 “children”, which is a general collective. However, the collective meanings are not always explicit in Tangut texts due to lexicalization accompanied by multiple semantic changes, which will be elaborated on in the following sections.

1241 zjɨ̣1-lji2 “children”, which is a general collective. However, the collective meanings are not always explicit in Tangut texts due to lexicalization accompanied by multiple semantic changes, which will be elaborated on in the following sections.

3.1.  5070

5070 5049 zjɨ̣1-wja1 “father and son”,

5049 zjɨ̣1-wja1 “father and son”,  5070

5070 0092 zjɨ̣1-mja1 “mother and son”

0092 zjɨ̣1-mja1 “mother and son”

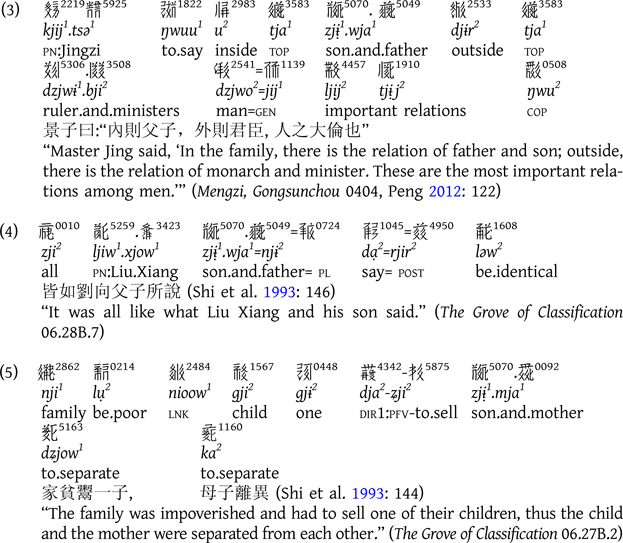

The two compounds ![]() 5070

5070![]() 5049 zjɨ̣1-wja1 “father and son” and

5049 zjɨ̣1-wja1 “father and son” and ![]() 5070

5070![]() 0092 zjɨ̣1-mja1 “mother and son” exhibit transparent semantics, representing the two most prominent social relationships: father-son (examples 3 and 4) and mother-son (example 5). Both compounds follow the same word formation pattern, in which the collective prefix *S- precedes the two components overtly referring to the two participants in the denoted social relations, i.e.

0092 zjɨ̣1-mja1 “mother and son” exhibit transparent semantics, representing the two most prominent social relationships: father-son (examples 3 and 4) and mother-son (example 5). Both compounds follow the same word formation pattern, in which the collective prefix *S- precedes the two components overtly referring to the two participants in the denoted social relations, i.e. ![]() 5070 zjɨ̣1- “son” and

5070 zjɨ̣1- “son” and ![]() 5049 wja1 “father”/

5049 wja1 “father”/![]() 0092 mja1 “mother”.

0092 mja1 “mother”.

In the two compounds, the younger generation participant consistently precedes the elder generation participant. This order is reversed compared to the Chinese terms 父子 fù-zǐ (father-son) and 母子 mǔ-zǐ (mother-son) in the source text, indicating that these collective forms have become fossilized in Tangut. In particular, in (3), the Tangut translation mostly adheres to a literal rendering of the original Chinese text. Terms like ![]() 5306

5306![]() 3508 dzjwɨ1-bji2 “ruler and minister” and

3508 dzjwɨ1-bji2 “ruler and minister” and ![]() 4457

4457![]() 1910 ljịj2tjɨ̣j2 “important relations” are adapted to match the word order of the Chinese original 君臣 jūn-chén and 大倫 dà-lún. In contrast, only

1910 ljịj2tjɨ̣j2 “important relations” are adapted to match the word order of the Chinese original 君臣 jūn-chén and 大倫 dà-lún. In contrast, only ![]() 5070

5070![]() 5049 “son and father” retains the native word order of Tangut.Footnote 5

5049 “son and father” retains the native word order of Tangut.Footnote 5

3.2.  5721

5721 3562 zjɨ̣1-mjaa1 “husband and wife, couple”

3562 zjɨ̣1-mjaa1 “husband and wife, couple”

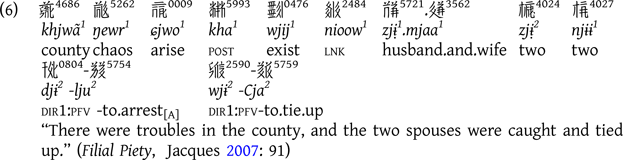

The collective ![]() 5721

5721![]() 3562 zjɨ̣1-mjaa1 “husband and wife, couple” follows a different word formation pattern. Nonetheless, the social relation between husband and wife, as represented in its meaning, is prominent in Tangut texts (e.g. 6).Footnote 6

3562 zjɨ̣1-mjaa1 “husband and wife, couple” follows a different word formation pattern. Nonetheless, the social relation between husband and wife, as represented in its meaning, is prominent in Tangut texts (e.g. 6).Footnote 6

The two components of ![]() 5721

5721![]() 3562 zjɨ̣1-mjaa1 “husband and wife, couple” both refer to the husband, with the wife unexpressed in the compound. The first component

3562 zjɨ̣1-mjaa1 “husband and wife, couple” both refer to the husband, with the wife unexpressed in the compound. The first component ![]() 5721 zjɨ̣1 represents the bound state of

5721 zjɨ̣1 represents the bound state of ![]() 1085 zji1, based on its semantics of “male”. The second component

1085 zji1, based on its semantics of “male”. The second component ![]() 3562 mjaa1 is etymologically related to

3562 mjaa1 is etymologically related to ![]() 4820 mạ1 “son-in-law”, reflecting the etymon for “son-in-law, bridegroom”, cognate with ɣmɑ́ɣ “son-in-law, husband” in Siyuewu Khroskyabs, a-me-nmaʁ “son-in-law” in Japhug, tə-nmak “son-in-law” in Cogtse (Lin You-jing's field data), and མག་པ། mag.pa “son-in-law, bridegroom” in Tibetan (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang2010: 2053).

4820 mạ1 “son-in-law”, reflecting the etymon for “son-in-law, bridegroom”, cognate with ɣmɑ́ɣ “son-in-law, husband” in Siyuewu Khroskyabs, a-me-nmaʁ “son-in-law” in Japhug, tə-nmak “son-in-law” in Cogtse (Lin You-jing's field data), and མག་པ། mag.pa “son-in-law, bridegroom” in Tibetan (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang2010: 2053).

An alternative etymology proposed by Shi (Reference Shi2020: 461) suggests that ![]() 3562 mjaa1, occurring in the compound

3562 mjaa1, occurring in the compound ![]() 5721

5721![]() 3562 zjɨ̣1-mjaa1, might be related to

3562 zjɨ̣1-mjaa1, might be related to ![]() 2436 mjaa1 “fruit”. However, our proposal that

2436 mjaa1 “fruit”. However, our proposal that ![]() 3562 mjaa1 is etymologically related to

3562 mjaa1 is etymologically related to ![]() 4820 mạ1 “son-in-law” better aligns with the semantics of this collective. The term

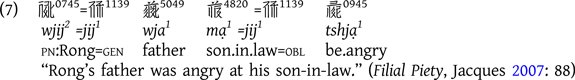

4820 mạ1 “son-in-law” better aligns with the semantics of this collective. The term ![]() 4820 mạ1 “son-in-law” is often used independently, as illustrated in (7).

4820 mạ1 “son-in-law” is often used independently, as illustrated in (7).

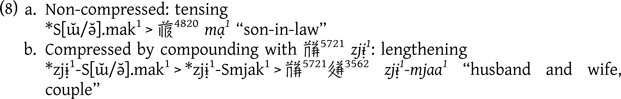

The rhyme alternation observed between ![]() 3562 mjaa1 and

3562 mjaa1 and ![]() 4820 mạ1 can be explained by the compounding morphology that involves syllable compression. As previously explained in Section 2 (see also Lai Reference Lai2023; Reference Lai2024), the alternation between

4820 mạ1 can be explained by the compounding morphology that involves syllable compression. As previously explained in Section 2 (see also Lai Reference Lai2023; Reference Lai2024), the alternation between ![]() 4820 mạ1 (<*S[ɯ̆/ə̆].mak1) and

4820 mạ1 (<*S[ɯ̆/ə̆].mak1) and ![]() 3562 mjaa1 (<*Smjak1) can be attributed to the syllabicity in the pre-initial element (see the first stages in 1a, 1b and 1c). It can be posited that the syllabic pre-initial would have been compressed in compounding, as

3562 mjaa1 (<*Smjak1) can be attributed to the syllabicity in the pre-initial element (see the first stages in 1a, 1b and 1c). It can be posited that the syllabic pre-initial would have been compressed in compounding, as ![]() 3562 mjaa1 (<*Smjak1) is exclusively found in the compound

3562 mjaa1 (<*Smjak1) is exclusively found in the compound ![]() 5721

5721![]() 3562 zjɨ̣1-mjaa1.

3562 zjɨ̣1-mjaa1.

For an illustration of the compressing processes, see the sound changes presented in (8), with the non-compressed ![]() 4820 mạ1 “son-in-law” in (8a) and the compressed

4820 mạ1 “son-in-law” in (8a) and the compressed ![]() 5721

5721![]() 3562 zjɨ̣1-mjaa1 “husband and wife, couple” in (8b) (note that the tensing process of

3562 zjɨ̣1-mjaa1 “husband and wife, couple” in (8b) (note that the tensing process of ![]() 5721 zjɨ̣1 is omitted for clarity). The alternation between a Grade I rhyme -ạ in

5721 zjɨ̣1 is omitted for clarity). The alternation between a Grade I rhyme -ạ in ![]() 4820 mạ1 and a Grade III rhyme -jaa, reconstructed with a medial -j- in

4820 mạ1 and a Grade III rhyme -jaa, reconstructed with a medial -j- in ![]() 3562 mjaa1, could be explained by a harmonizing process mirroring the Grade III rhyme of

3562 mjaa1, could be explained by a harmonizing process mirroring the Grade III rhyme of ![]() 5721 zjɨ̣1-.

5721 zjɨ̣1-.

In modern Gyalrongic languages, social relation collectives can be formed by including both parties involved in the relation, or more commonly, by including only one of the parties. For instance, in Bragbar Situ, the term koɕə-tɕa-jâ “brothers and sisters, siblings” is derived from tɕetɕé “younger siblings” and a-jâ “elder siblings” (Zhang Reference Zhang2020: 218, see also Section 5.1.1 for examples in Siyuewu Khroskyabs). Alternatively, in Japhug, kɤndʑi-ɣe “grandparents and grandchildren” is based on tɤ-ɣe “grandchild” (Jacques Reference Jacques2021: 177). Notably, Tshobdun Gyalrong has two collective terms for “married couple”, one of them, kɐndʒe-nmə́-nma, is derived solely from tɐ́-nma “husband”, whereas the other, kɐndʒe-rɟə́-rɟev, is based only on tɐ́-rɟev “wife” (Sun Reference Sun1997), which corresponds exactly to the Tangut case.

3.3.  5525

5525 1241 zjɨ̣1 -lji2 “children, baby”

1241 zjɨ̣1 -lji2 “children, baby”

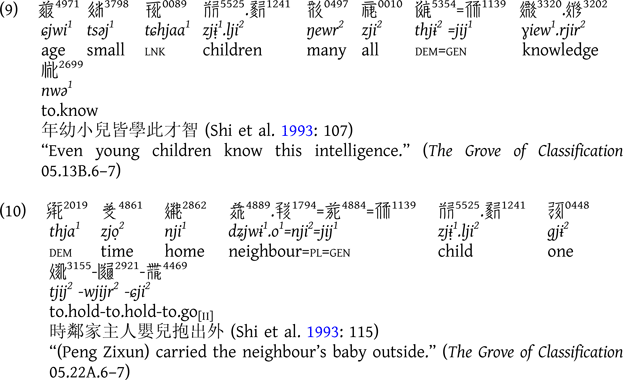

The compound, ![]() 5525

5525![]() 1241 zjɨ̣1-lji2 “children, baby” does not denote a specific social relation but rather serves as a general collective term. However, it is noteworthy that in Tangut texts,

1241 zjɨ̣1-lji2 “children, baby” does not denote a specific social relation but rather serves as a general collective term. However, it is noteworthy that in Tangut texts, ![]() 5525

5525![]() 1241 zjɨ̣1-lji2 can refer both to the collective concept of “children” and to an individual entity, such as a “small child”. For instance, in (10),

1241 zjɨ̣1-lji2 can refer both to the collective concept of “children” and to an individual entity, such as a “small child”. For instance, in (10), ![]() 5525

5525![]() 1241 zjɨ̣1-lji2 is followed by the singular indefinite marker

1241 zjɨ̣1-lji2 is followed by the singular indefinite marker ![]() 0448 gjɨ2.

0448 gjɨ2.

It is likely that ![]() 5525

5525![]() 1241 zjɨ̣1-lji2, as the result of collective derivation in an earlier stage, has undergone semantic evolution, transitioning from a term for a group to a more general term. Semantic shifts of this nature are common; for instance, in Mandarin Chinese, the term 觀眾 guān.zhòng “audience” originally denoted a collective concept exclusively, but has gradually evolved into a general noun that can refer to both a group and an individual, as evidenced by the modern usage of 一個觀眾 yí-gè guān.zhòng (one-CLF audience) “a spectator”.

1241 zjɨ̣1-lji2, as the result of collective derivation in an earlier stage, has undergone semantic evolution, transitioning from a term for a group to a more general term. Semantic shifts of this nature are common; for instance, in Mandarin Chinese, the term 觀眾 guān.zhòng “audience” originally denoted a collective concept exclusively, but has gradually evolved into a general noun that can refer to both a group and an individual, as evidenced by the modern usage of 一個觀眾 yí-gè guān.zhòng (one-CLF audience) “a spectator”.

Another point worth noting is the etymology of the two components of ![]() 5525

5525![]() 1241 zjɨ̣1-lji2. The first component is the bound state of

1241 zjɨ̣1-lji2. The first component is the bound state of ![]() 1085 zji1 “male, offspring, son”, while the second component

1085 zji1 “male, offspring, son”, while the second component ![]() 1241 lji2 is likely a diminutive suffix, as found in Siyuewu Khroskyabs zî-lo “son (hypocoristic)” and mæ̂-lo “darling (addressing younger generations)”. The meaning “small” in

1241 lji2 is likely a diminutive suffix, as found in Siyuewu Khroskyabs zî-lo “son (hypocoristic)” and mæ̂-lo “darling (addressing younger generations)”. The meaning “small” in ![]() 5525

5525![]() 1241 zjɨ̣1-lji2 may originate from this diminutive suffix. However, due to the obscurity of the collective morphology and the decreased productivity of the diminutive suffix, the lexical meaning of

1241 zjɨ̣1-lji2 may originate from this diminutive suffix. However, due to the obscurity of the collective morphology and the decreased productivity of the diminutive suffix, the lexical meaning of ![]() 5525

5525![]() 1241 zjɨ̣1-lji2 indicating “small child, infant” has been transferred to the character

1241 zjɨ̣1-lji2 indicating “small child, infant” has been transferred to the character ![]() 5525 zjɨ̣1. This character then contrasts semantically with its base

5525 zjɨ̣1. This character then contrasts semantically with its base ![]() 1085 zji1, which is used as a kinship term meaning “son, offspring”.Footnote 7 Additionally,

1085 zji1, which is used as a kinship term meaning “son, offspring”.Footnote 7 Additionally, ![]() 5525 zjɨ̣1 continues to be used in later compounding mechanisms, such as in

5525 zjɨ̣1 continues to be used in later compounding mechanisms, such as in ![]() 5619

5619![]() 5525 mjɨ2- zjɨ̣1 meaning “mischievous child” (see Li Reference Li2012: 670).

5525 mjɨ2- zjɨ̣1 meaning “mischievous child” (see Li Reference Li2012: 670).

4. Compound medial linker *-S-

A handful of compounds in Tangut have a tense vowel occurring in the second component. In such cases, the tense vowel likely originates from an *-S- element, which serves as a morphological linker connecting the two components. This compound medial *-S- later underwent transphonologization, resulting in a tense vowel in the second syllable. This process is represented in (11).

(11) Transphonologization of the compound linker *-S-

*CV-S-CV > CV-CṾ

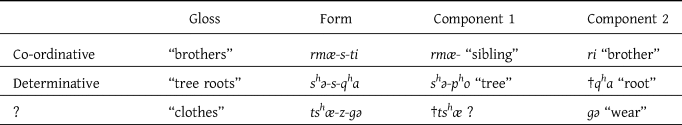

Table 3 provides a list of compounds in Tangut that potentially contain a compound linker *-S-. As the etymology of each component is not entirely transparent, we will offer detailed etymological analyses in the subsequent sections.

Table 3. Traces of compound linker *-S- in Tangut

4.1.  2447

2447 0605 ljo2-tjọ2 “brothers”

0605 ljo2-tjọ2 “brothers”

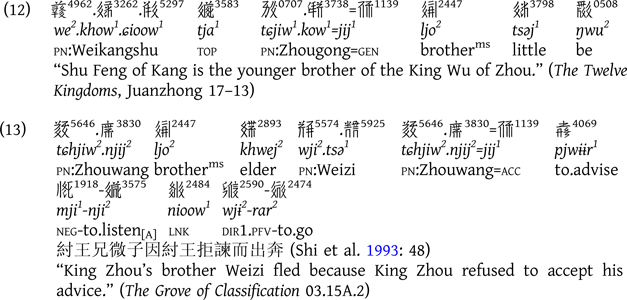

There is general agreement that the two characters ![]() 2447 ljo2 and

2447 ljo2 and ![]() 0605 tjọ2 both refer to “brother” in the context of male speakers (ms). However, there is some disagreement regarding their specific semantic representation. Kepping (Reference Kepping1991: 5) interprets

0605 tjọ2 both refer to “brother” in the context of male speakers (ms). However, there is some disagreement regarding their specific semantic representation. Kepping (Reference Kepping1991: 5) interprets ![]() 2447 ljo2 as a term for the brothers of a male speaker, while

2447 ljo2 as a term for the brothers of a male speaker, while ![]() 0605 tjọ2 is considered a collective term, meaning “brothers”. Jacques (Reference Jacques and Hill2012), among others, suggests that

0605 tjọ2 is considered a collective term, meaning “brothers”. Jacques (Reference Jacques and Hill2012), among others, suggests that ![]() 2447 ljo2 and

2447 ljo2 and ![]() 0605 tjọ2 encode relative age distinction, with the former denoting an elder brother and the latter a younger brother of a male speaker.

0605 tjọ2 encode relative age distinction, with the former denoting an elder brother and the latter a younger brother of a male speaker.

A closer examination of the usage of these two characters in Tangut texts shows that the semantic distinction between ![]() 2447 ljo2 and

2447 ljo2 and ![]() 0605 tjọ2 does not pertain to relative age. As illustrated in (12) and (13),

0605 tjọ2 does not pertain to relative age. As illustrated in (12) and (13), ![]() 2447 ljo2 can refer to both the younger or elder brothers of a man.

2447 ljo2 can refer to both the younger or elder brothers of a man.

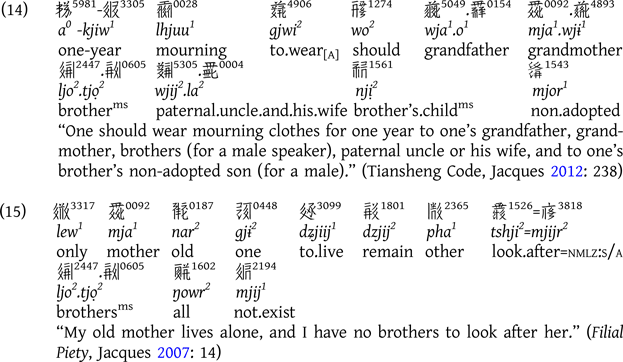

In most cases, ![]() 0605 tjọ2 is used as a bound morpheme. The two characters

0605 tjọ2 is used as a bound morpheme. The two characters ![]() 2447

2447![]() 0605 ljo2-tjọ2 appear together as a compound, representing the collective concept of “brothers”, as in examples (14) and (15).

0605 ljo2-tjọ2 appear together as a compound, representing the collective concept of “brothers”, as in examples (14) and (15).

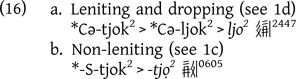

The compounding morphology also accounts for the two phonological alternations between the terms ![]() 2447 ljo2 and

2447 ljo2 and ![]() 0605 tjọ2: (i) initial lenition alternation between l- and t-, and (ii) the tense vowel alternation between -jo and -jọ. According to the transphonologization rule, these alternations are due to the presence of the compound linker *-S-.

0605 tjọ2: (i) initial lenition alternation between l- and t-, and (ii) the tense vowel alternation between -jo and -jọ. According to the transphonologization rule, these alternations are due to the presence of the compound linker *-S-.

The sound changes in (16) suggest that ![]() 0605 tjọ2 and

0605 tjọ2 and ![]() 2447 ljo2 share the same stem *-tjok2 “brother (male speaker)” in Pre-Tangut. The lenition observed in

2447 ljo2 share the same stem *-tjok2 “brother (male speaker)” in Pre-Tangut. The lenition observed in ![]() 2447 ljo2 is due to the loss of a presyllable (the fourth type shown in (1d) in Section 2), for instance, the possessive prefix *tə- still present in East Gyalrongic. Conversely, the tense vowel in

2447 ljo2 is due to the loss of a presyllable (the fourth type shown in (1d) in Section 2), for instance, the possessive prefix *tə- still present in East Gyalrongic. Conversely, the tense vowel in ![]() 0605 tjọ2 results from the original *-S- blocking lenition (see the third type (1c) in Section 2).

0605 tjọ2 results from the original *-S- blocking lenition (see the third type (1c) in Section 2).

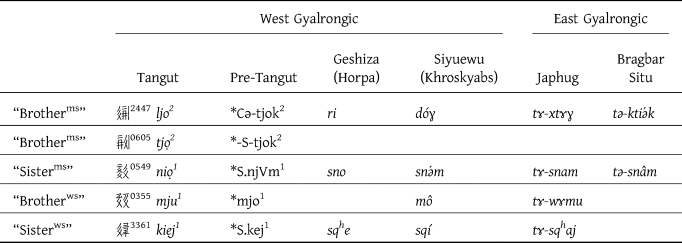

This argument is further supported by comparative evidence. First, sibling terminology in Tangut is characterized by a clear opposition between male and female speaking subsystems (Jacques Reference Jacques and Hill2012; Kepping Reference Kepping1991; Shi Reference Shi2020: 462–3), a feature inherited from Proto-Gyalrongic. As illustrated in Table 4, this terminological system is also preserved in modern Gyalrongic languages, such as Siyuewu, Japhug, and Situ (with Bragbar Situ having lost the female-speaking sub-system, see Zhang and Fan Reference Zhang and Fan2020), where no relative age distinction is evident.

Table 4. Sibling terms in Gyalrongic languages

Second, similar initial lenition alternations observed in Tangut ![]() 2447 ljo2 and

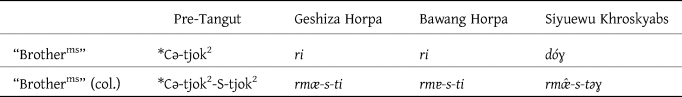

2447 ljo2 and ![]() 0605 tjọ2 are also found in cognate “brother (male speaker)” terms in Horpa languages (West Gyalrongic). As illustrated in Table 5, the lenited form ri (from *Cə-to, see Lai Reference Lai2023) is used as an unbound form, while the non-lenited form sti (from *s-to) with an s- pre-initial occurs as the second component of the collective compound “brothers” (See Lai Reference Lai2023: 362–5 for a detailed explanation). The pre-initial s- is comparable to the tense vowel in Tangut

0605 tjọ2 are also found in cognate “brother (male speaker)” terms in Horpa languages (West Gyalrongic). As illustrated in Table 5, the lenited form ri (from *Cə-to, see Lai Reference Lai2023) is used as an unbound form, while the non-lenited form sti (from *s-to) with an s- pre-initial occurs as the second component of the collective compound “brothers” (See Lai Reference Lai2023: 362–5 for a detailed explanation). The pre-initial s- is comparable to the tense vowel in Tangut ![]() 0605 tjọ2, with both reflecting a compound linker *-S- (see Section 5.2 for further comparison).

0605 tjọ2, with both reflecting a compound linker *-S- (see Section 5.2 for further comparison).

Table 5. Initial lenition alternation of the terms for “brothers (male speaker)” in West Gyalrongic languages

4.2.  1888

1888 1304 bə2-lụ1 “worms”

1304 bə2-lụ1 “worms”

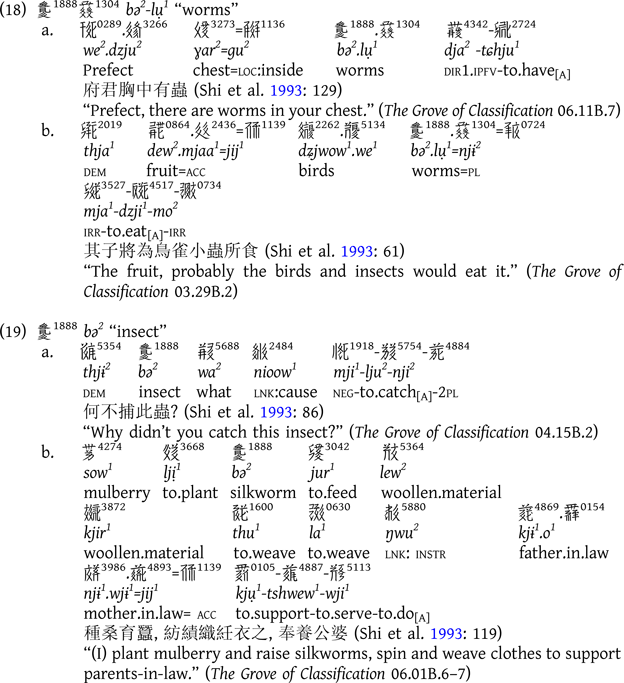

The second component of the compound ![]() 1888

1888![]() 1304 bə2-lụ1 “worms” also carries a tense vowel,Footnote 8 which likely originates from a compound linker *S- that transphonologized onto the second syllable, as illustrated in (17).

1304 bə2-lụ1 “worms” also carries a tense vowel,Footnote 8 which likely originates from a compound linker *S- that transphonologized onto the second syllable, as illustrated in (17).

The compound ![]() 1888

1888![]() 1304 bə2-lụ1 “worms” and

1304 bə2-lụ1 “worms” and ![]() 2447

2447![]() 0605 ljo2-tjọ2 “brothers” may share the same compounding mechanism. This involves bisyllabification through stem reduplication or juxtaposition of different roots, linked by *-S-, to form a compound representing a collective concept. The semantic differences between the compound

0605 ljo2-tjọ2 “brothers” may share the same compounding mechanism. This involves bisyllabification through stem reduplication or juxtaposition of different roots, linked by *-S-, to form a compound representing a collective concept. The semantic differences between the compound ![]() 1888

1888![]() 1304 bə2-lụ1 “worms” and the unbound root

1304 bə2-lụ1 “worms” and the unbound root ![]() 1888 bə2 “worm” can be observed in textual examples. The compound

1888 bə2 “worm” can be observed in textual examples. The compound ![]() 1888

1888![]() 1304 bə2-lụ1 involves a collective reading (e.g. 18), whereas

1304 bə2-lụ1 involves a collective reading (e.g. 18), whereas ![]() 1888 bə2 denotes singular concepts, such as a particular type of insect such as locusts in (19a) and silkworm in (19b).

1888 bə2 denotes singular concepts, such as a particular type of insect such as locusts in (19a) and silkworm in (19b).

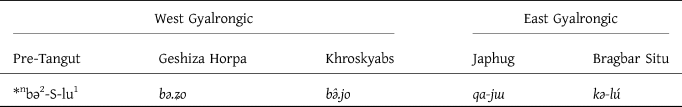

Comparative evidence supports the hypothesis that the tense vowel in the second component ![]() 1304 lụ1 originates from a linker *-S- rather than being an inherent part of the root. As illustrated in Table 6, the bisyllabic form for “worm(s)” in West Gyalrongic contains a shared innovative root bə- as the first component. The second component corresponds to the Gyalrongic etymon for “insect, worm”, which is preserved as unbound lexemes in East Gyalrongic with the animal prefix, such as Japhug qa-jɯ “worm” (Jacques Reference Jacques2014: 72) and Bragbar Situ kə-lú “worm”. While the correspondence of the initials is regular,Footnote 9 the tense vowel (< *S-) in Tangut

1304 lụ1 originates from a linker *-S- rather than being an inherent part of the root. As illustrated in Table 6, the bisyllabic form for “worm(s)” in West Gyalrongic contains a shared innovative root bə- as the first component. The second component corresponds to the Gyalrongic etymon for “insect, worm”, which is preserved as unbound lexemes in East Gyalrongic with the animal prefix, such as Japhug qa-jɯ “worm” (Jacques Reference Jacques2014: 72) and Bragbar Situ kə-lú “worm”. While the correspondence of the initials is regular,Footnote 9 the tense vowel (< *S-) in Tangut ![]() 1304 lụ1 lacks a counterpart in modern Gyalrongic. This suggests that the tense vowel (< *S-) in Tangut comes from an extra-root element, most likely the compound linker *-S- necessary for lexical bi-syllabification.Footnote 10

1304 lụ1 lacks a counterpart in modern Gyalrongic. This suggests that the tense vowel (< *S-) in Tangut comes from an extra-root element, most likely the compound linker *-S- necessary for lexical bi-syllabification.Footnote 10

Table 6. Comparison of the terms for “insect(s), worm(s)” in Gyalrongic languages

4.3.  0012

0012 5873 bju1-kụ2 “brothers”

5873 bju1-kụ2 “brothers”

The compound ![]() 0012

0012![]() 5873 bju1-kụ2 “brothers” is not found in textual attestations but is recorded in dictionaries such as Homophones and Sea of characters, where it is defined as a collective term meaning “brothers”. Although there is no textual evidence that the two components can be used individually in Tangut, both components have potential cognates in other Sino-Tibetan languages.

5873 bju1-kụ2 “brothers” is not found in textual attestations but is recorded in dictionaries such as Homophones and Sea of characters, where it is defined as a collective term meaning “brothers”. Although there is no textual evidence that the two components can be used individually in Tangut, both components have potential cognates in other Sino-Tibetan languages.

The first component, ![]() 0012 bju1, is likely related to the first syllable of Tibetan བུ་སྤུན། bu.spun “brothers” (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang2010: 1830).Footnote 11 Note that the Tibetan form contains a collective prefix s- in the second component spun (see Section 5.1.2).

0012 bju1, is likely related to the first syllable of Tibetan བུ་སྤུན། bu.spun “brothers” (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang2010: 1830).Footnote 11 Note that the Tibetan form contains a collective prefix s- in the second component spun (see Section 5.1.2).

The second component ![]() 5873 kụ2 is related to Burmese အကို akui (Proto-Burmish *kuiw) “elder brother” and is further connected to Tibetan ཁུ khu, which originally meant “maternal uncle” (see Nagano Reference Nagano1994), and Old Chinese 舅 *[g](r)uʔ “maternal uncle” (Hill Reference Hill2019: 77, 239; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Jacques and Lai2019).Footnote 12 The semantic discrepancy is similar to the case of སྐུད་པོ skud-po “brother-in-law”, derived from ཁུ khu “maternal uncle” with the circumfix s-Σ-d (< *s-khu-d, see Benedict Reference Benedict1942, Section 5.1.2).

5873 kụ2 is related to Burmese အကို akui (Proto-Burmish *kuiw) “elder brother” and is further connected to Tibetan ཁུ khu, which originally meant “maternal uncle” (see Nagano Reference Nagano1994), and Old Chinese 舅 *[g](r)uʔ “maternal uncle” (Hill Reference Hill2019: 77, 239; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Jacques and Lai2019).Footnote 12 The semantic discrepancy is similar to the case of སྐུད་པོ skud-po “brother-in-law”, derived from ཁུ khu “maternal uncle” with the circumfix s-Σ-d (< *s-khu-d, see Benedict Reference Benedict1942, Section 5.1.2).

Comparative evidence suggests that both roots lack a pre-initial element, and the tense vowel in the second component of ![]() 0012

0012![]() 5873 bju1-kụ2 “brothers” likely originates from a compound linker *-S-, serving to link the two co-ordinative roots. However, this proposal remains to be verified with clearer etymological evidence.

5873 bju1-kụ2 “brothers” likely originates from a compound linker *-S-, serving to link the two co-ordinative roots. However, this proposal remains to be verified with clearer etymological evidence.

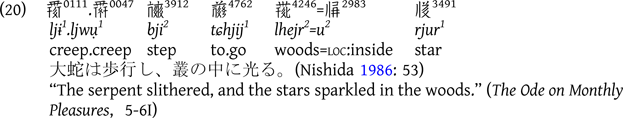

4.4.  0111

0111 0047 ljɨ1-ljwụ1 “snake”

0047 ljɨ1-ljwụ1 “snake”

The compound ![]() 0111

0111![]() 0047 ljɨ1-ljwụ1 in Tangut typically signifies “snake”, as evidenced in (20), with no instances of its components being used independently. This term likely originates from an ideophone, capturing the serpentine movement characteristic of a snake, later extending its meaning to the animal itself. It is potentially related to Wobzi Khroskyabs z-bæ-ljə̂~ljɑ “to lie prone, to crawl”.

0047 ljɨ1-ljwụ1 in Tangut typically signifies “snake”, as evidenced in (20), with no instances of its components being used independently. This term likely originates from an ideophone, capturing the serpentine movement characteristic of a snake, later extending its meaning to the animal itself. It is potentially related to Wobzi Khroskyabs z-bæ-ljə̂~ljɑ “to lie prone, to crawl”.

Should the hypothesized ideophonic origin of this compound hold true, its formation process can be elucidated by reduplication. Although Gong (Reference Gong1993) does not document the -jɨ :: -jwu alternation pattern,Footnote 13 it is plausible to hypothesize that the first component ![]() 0111 ljɨ1 serves as the reduplicant, while the second component

0111 ljɨ1 serves as the reduplicant, while the second component ![]() 0047 ljwụ1 represents the root. Thus, the tense vowel in the second component is likely not inherent to the root but instead results from the transphonologization of the compound linker *-S-. However, this hypothesis requires validation through the establishment of phonological alternation rules.

0047 ljwụ1 represents the root. Thus, the tense vowel in the second component is likely not inherent to the root but instead results from the transphonologization of the compound linker *-S-. However, this hypothesis requires validation through the establishment of phonological alternation rules.

5. Origins of the *S elements in Tangut compounds

Internal evidence suggests that the collective prefix *S- and the compound medial *-S- serving as a linking element in Tangut must be distinguished synchronically. These two morphological processes are attested with only a few traces, which provide important clues for revealing the regular morphology of an earlier stage.

This section provides a comparative study of the corresponding morphemes, showing that the two morphological processes are also distinct at the West Gyalrongic level, shared among Tangut, Horpa and Khroskyabs. The collective *S- likely represents inherited morphology with parallels in Tibetan (Section 5.1), whereas the compound medial *-S- represents a stage of morphological merging in West Gyalrongic, with an unclear origin (Section 5.2).

5.1. Historical status of the collective prefix *S-

In both West Gyalrongic and Tibetan, traces of a collective prefix *S- have been retained, indicating that this morphology is likely archaic.

5.1.1. West Gyalrongic

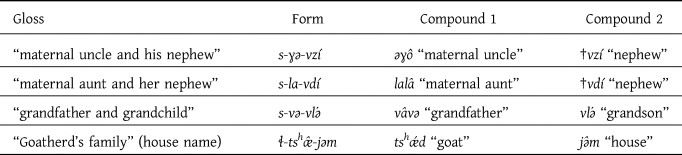

Within West Gyalrongic, Siyuewu Khroskyabs retains a collective prefix s-, observed in a few collectives of social relations (see Table 7). Similar to Tangut, social relation collectives in Siyuewu also involve kinship terms, with both parts in the denoted social relation overtly expressed by the two components (see Table 5).

Table 7. Social relation collective s- in Siyuewu Khroskyabs

Note: the † indicates forms without unbound attestation.

The first compound s-ɣə-vzí “maternal uncle and his sister's children” is composed of ɣə- (the bound state of əɣô “maternal uncle”) and a bound root †vzí “sister's children (for a male speaker)”. Both components are inherited Proto-Gyalrongic kinship terms. The Siyuewu əɣô “maternal uncle” reflects the Gyalrongic etymon for maternal uncle, as in Tangut ![]() 0597 ɣjɨ1 (Pre-Tangut *CV-kjɨ1) “maternal uncle” and a-kû “maternal uncle” in Bragbar Situ (Zhang and Fan Reference Zhang and Fan2020). Although Siyuewu †vzí is unattested as an unbound morpheme, it is related to Tangut

0597 ɣjɨ1 (Pre-Tangut *CV-kjɨ1) “maternal uncle” and a-kû “maternal uncle” in Bragbar Situ (Zhang and Fan Reference Zhang and Fan2020). Although Siyuewu †vzí is unattested as an unbound morpheme, it is related to Tangut ![]() 2134 zjwị 1 (Pre-Tangut *S-pə̆.tsa) “cross nephew, child of different-sex siblings”.Footnote 14

2134 zjwị 1 (Pre-Tangut *S-pə̆.tsa) “cross nephew, child of different-sex siblings”.Footnote 14

The second collective s-lɑ-vdí “maternal aunt and her sister's children” is built upon lɑ- (the bound state of lɑlɑ́ “maternal aunt”) and †vdí “nephew, sister's children (for a female speaker)”. The unbound root †vdí is cognate with vdé in Njorogs Khroskyabs (Yin Reference Yin2007) and tə-mdi “nephew” in Cogtse Situ (Lin You-Jing's field note), among others.

In the third collective s-və-vlə́ “grandfather and grandchild”, the first component və- represents the Proto-Gyalrongic term for “grandfather”, preserved in Bragbar ta-wû and Japhug tɤ-wɯ, and also occurs as the second component of vɑ̂-və “grandfather” in Siyuewu.

Since the three collectives mentioned above contain bound roots that are not attested individually, it is likely that the collective prefix s- in Siyuewu is archaic. However, it is worth noting that this morphological process seems to have lost its productivity in Siyuewu only recently. A remnant of the s- collective is found in a Siyuewu house name ɬ-tshæ̂-jəm (col-goat-house), in which the initial consonant ɬ- is a conditioned variant of the collective s- prefix (see Lai Reference Lai2016 on the Siyuewu s- allomorphy). The ɬ-tshæ̂-jəm family are goatherds, and the house name reflects the close relation between goats and their owners.Footnote 15 The ɬ-tshæ̂-jəm family became goatherds during the people's commune period in China (1950–60s), and the house name was thus created during that time. This indicates that the collective prefix s- remains productive in Siyuewu up to that time.

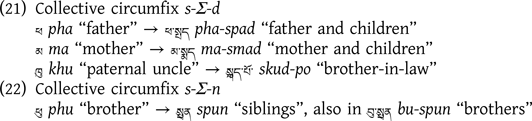

5.1.2. Tibetan

The preservation of the collective prefix *S- in both Tangut and Siyuewu suggests that this morphology dates back to Proto-West-Gyalrongic. Moreover, the presence of potential cognate morphemes in Tibetan further supports the antiquity of the West Gyalrongic collective prefix *S-.

In Tibetan, there are two collective circumfixes s-Σ-d and s-Σ-n (Benedict Reference Benedict1942: 323–5; Hill Reference Hill, Lieber and Štekauer2014: 628), in which the s- element is comparable to the West Gyalrongic collective *S-. Both circumfixes in Tibetan are unproductive and appear in only five collective terms derived from kinship terms, as listed in (21) and (22).Footnote 16 It is worth noting that the loss of aspiration in the derived forms with the s- pre-initial is explained by Shafer's law, i.e. *s-kh- > sk-, *s-ph- > sp- (see Hill Reference Hill2011; Li Reference Li1933; Shafer Reference Shafer1950–51).

Except for སྐུད་པོ skud-po “brother-in-law”, which bears a non-transparent semantic relationship with the base form ཁུ khu “paternal uncle”,Footnote 17 the other forms in (21) and (22) clearly convey collective meanings. It is plausible to assume that the collective meaning in these forms likely originates from the s- prefix. However, the exact mechanism by which this prefix interacts with the nominal suffixes -n and -d to form a circumfix remains unclear.

5.2. Historical status of the compound linker *-S-

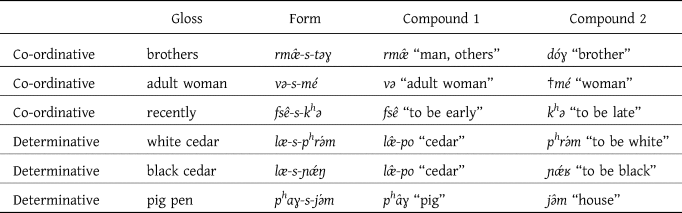

The compound linker *-S-, while leaving only a few traces in Tangut, appears to be a morphological process shared among West Gyalrongic languages. Data from modern West Gyalrongic languages further indicate that the linker *-S- is used not only to derive co-ordinative compounds with collective meaning, as seen in Tangut, but also to form determinative compounds.

Table 8 shows compounds with a linker -s- in Siyuewu Khroskyabs, along with glosses of their components.

Table 8. Traces of compound linker *-S- in Siyuewu Khroskyabs

Co-ordinative compounds in Siyuewu juxtapose two synonymous or antonymous components. For example, the compound rmæ̂-s-təɣ “brothers” combines two synonymous components: rmæ̂ “man, others” and dóɣ “brother”, connected by the linker -s- (for a discussion of the etymology see Section 4.1, Table 5).

The compound və-s-mé is formed through a similar process.Footnote 18 Its first component və-, though unattested as a free morpheme, is related to the second component in gə-və̂ “wife” (further related to Tangut ![]() 2455

2455![]() 2129 gji2-bjij2 “wife”, see Lai et al. Reference Lai, Gong, Gates and Jacques2020). The second component -s-mé reflects the Gyalrongic etymon for “woman, girl”, as in Japhug tɯ-me and Bragbar Situ tə-mí.

2129 gji2-bjij2 “wife”, see Lai et al. Reference Lai, Gong, Gates and Jacques2020). The second component -s-mé reflects the Gyalrongic etymon for “woman, girl”, as in Japhug tɯ-me and Bragbar Situ tə-mí.

The compound fsê-s-khə juxtaposes two antonymous components, fsê “to be early” and khə̂ “to be late”, linked by -s-. This compound expresses a collective meaning “early or late”, hence “recently”.

Siyuewu determinative compounds can be further divided into two types based on their internal syntax – left-headed and right-headed.Footnote 19 An example of a left-headed compound concerns læ-s-phrə́m “white cedar” and læ-s-ɲǽŋ “black cedar”, which denote two sub-species of cedar. In such compounds, the linker -s- connects the head læ- “cedar” and the modifiers, pʰrə́m “to be white” and ɲǽʁ “to be black”.

The term phɑɣ-s-jə́m “pig pen” is a case of right-headed compound, in which the linker -s- connects the modifier phɑ̂ɣ “pig” and the head jə̂m “house”.Footnote 20

Traces of the compound linker *-S- are also found in Horpa languages, as exemplified by Geshiza Horpa in Table 9.Footnote 21

Table 9. Traces of compound linker *-S- in Geshiza (data from Honkasalo Reference Honkasalo2019)

Geshiza rmæ-s-ti “brothers”, which is cognate with Siyuewu rmæ̂-s-təɣ, is a co-ordinative compound, in which the two synonymous components are linked together by -s-.

The determinative compound shə-s-qha “tree roots” is right-headed, in which the linker -s- connects the modifier shə- “tree, wood (bound state)” and the head †qha “root”, a bound root. The second component is related to Guanyinqiao Khroskyabs qé “root”, sɲi-qhé “tongue root”, and Japhug Gyalrong ɯ-qa “root”). These Gyalrongic cognates suggest a proto-form for “root” without a sibilant pre-initial. Thereby the presence of the linker -s- in shə-s-qha “tree roots” suggests the productivity of the compound linker -s- after the branch-off of Horpa.

The third compound tshæ-z-gə “clothes”, in which the linker -s- is assimilated to -z-, is currently only found in Geshiza and Bawang (tshɐ-z-gwə “clothes”). Parallel compounds with cognate roots but lacking a sibilant linker morpheme exist within Gyalrongic, such as Khang.gsar Stau (Horpa) tsə-gə, Siyuewu Khroskyabs tshə-gí, Tangut ![]() 5610

5610![]() 5598 tshjɨ1-gjwi2 “clothes” (Li Reference Li2012: 667, 669), and beyond, Pengbuxi Minyag tse-ŋgə (Gao Reference Gao2016), Guiqiong tshɛ33-wɛ53 (Zàngmiǎnyǔ Yǔyīn hé Cíhuì Biānxiězǔ Reference Biānxiězǔ1992), all meaning “clothes”. In the Geshiza form tshæ-z-gə “clothes”, while the second component -gə is related to the verb “to wear”, the first component tshæ- is not attested as a free lexeme. The sporadic appearance of the compound linker -s- in Geshiza and Bawang forms resembles the case of “worms”, where the sibilant linker is found only in Tangut

5598 tshjɨ1-gjwi2 “clothes” (Li Reference Li2012: 667, 669), and beyond, Pengbuxi Minyag tse-ŋgə (Gao Reference Gao2016), Guiqiong tshɛ33-wɛ53 (Zàngmiǎnyǔ Yǔyīn hé Cíhuì Biānxiězǔ Reference Biānxiězǔ1992), all meaning “clothes”. In the Geshiza form tshæ-z-gə “clothes”, while the second component -gə is related to the verb “to wear”, the first component tshæ- is not attested as a free lexeme. The sporadic appearance of the compound linker -s- in Geshiza and Bawang forms resembles the case of “worms”, where the sibilant linker is found only in Tangut ![]() 1888

1888![]() 1304 bə2-lụ1 “worms” (see Table 6). It suggests that the compound linker *-S- was still productive upon the separation of Tangut and Horpa.

1304 bə2-lụ1 “worms” (see Table 6). It suggests that the compound linker *-S- was still productive upon the separation of Tangut and Horpa.

While the compound linker *-S- probably began to emerge during the stage of Proto-West-Gyalrongic, such morphology is not expected to have arisen spontaneously; it may have resulted from the merger of multiple morphemes. For example, the -s- linker in co-ordinative compounds might be related to a collective prefix, re-analysed from a compound medial context like Tibetan མ་སྨད ma-smad “mother and daughter”. However, re-analysing this pattern from a collective prefix to a linker in determinative compounds would require generalization.

Alternatively, the Geshiza compound tshæ-z-gə “clothes” might suggest another possibility. If we consider tshæ cognate with Ersu tshɑ 55 “classifier for clothes” (Zàngmiǎnyǔ Yǔyīn hé Cíhuì Biānxiězǔ Reference Biānxiězǔ1992), then Geshiza tshæ-z-gə “clothes” can be analysed as a left-headed determinative compound, with the second part being a nominalized verb. Thus, the linker -z- likely originates from a sibilant nominalizer (*S-) used to derive oblique nouns (i.e. the instrument with which to wear).Footnote 22 This oblique nominalizer is no longer productive in West Gyalrongic but leaves traces in Wobzi Khroskyabs s-phə́m “lid” (derived from phə́m “to cover”) (Lai Reference Lai2017: 158, 511), as well as in the nominalizing tense vowel in Tangut, e.g. ![]() 5205 ɣạ1 “sword, weapon” (derived from

5205 ɣạ1 “sword, weapon” (derived from ![]() 5653 ɣa1 “to butcher, chop”) (Jacques Reference Jacques2014: 256).Footnote 23 We defer a full exploration of this issue to future research.

5653 ɣa1 “to butcher, chop”) (Jacques Reference Jacques2014: 256).Footnote 23 We defer a full exploration of this issue to future research.

6. Conclusion

The present research uncovers two previously unrecognized sources of vowel tensing in Tangut: the collective prefix (*S-) and the compound linker (*-S-). These findings not only deepen our understanding of Tangut nominal morphology but also shed light on the approximate age of these two morphemes. Comparative evidence suggests that the collective prefix *S- can be traced back at least to the common ancestor of Burmo-Qiangic and Tibetic, while the compound linker *-S- appears to have emerged during the West-Gyalrongic period.

This study also raises questions about the historical status of linker elements in Sino-Tibetan compounding morphology, which are often discerned through traces with obscure origins (see for instance Downer Reference Downer1959: 289–90 on the non-final qusheng in Old Chinese compounds; Bialek Reference Bialek2018: 233–45 on the linker elements in Old Tibetan). Evidence from West Gyalrongic further supports the idea that compound linkers were historically unstable, potentially resulting from morphological merger and subject to rapid disappearance.

By investigating Tangut tense vowels, this study underscores the importance of combining careful analysis of textual attestations with comparative studies of related languages for the morphological reconstruction of highly eroded languages. We do not, however, claim to have definitely resolved the origins of Tangut tense vowels. Future research with new examples will be necessary to refine or amend our conclusions.

Funding information

This research is supported by the Horizon Europe Marie-Skłodowska-Curie Actions Postdoctoral Fellowship (101110215 Kinship Systems in Gyalrong: History and Transformation; Zhang Shuya), the Irish Research Council under the SFI-IRC Pathway Programme (Project ID: 21/PATH-A/9374, Gyalrongic unveiled: Languages, Heritage, Ancestry; Yunfan Lai) and Nanyang Technological University, Singapore under the Nanyang Assistant Professorship (NAP 2024, #024576-00001; Yunfan Lai).