Introduction

Business can be either a formidable opponent or powerful advocate of policy reform. In the area of environmental policy, business has often been a policy opponent.Footnote 1 Environmental policy, which I also refer to as environmental regulation, imposes costs on firms to prevent environmental damages and thus often engenders resistance from profit-motivated business actors.Footnote 2 However, business coalitions have sometimes splintered with some companies breaking ranks to support environmental policy of some form, with significant implications for the type of environmental regulation that emerges.Footnote 3 This pattern of business opposition and fragmentation has been observed in other significant policy areas, including health care, employment and financial regulation.Footnote 4

Business unity and division emerged as a central theme in political science and political sociology after World War II.Footnote 5 More recent debate over the determinants of firm position-taking on public policy is framed by three major theoretical perspectives that emphasize economic, strategic and institutional factors respectively. Substantial research has been conducted within each theoretical tradition. However, with a number of notable exceptions,Footnote 6 few studies have advanced systematic propositions about how different factors interact to shape firm position-taking.Footnote 7 Further, little theoretical attention has been devoted to position-taking by coalitions of firms, rather than individual firms.

This article seeks to advance theory on business position-taking on environmental policy,Footnote 8 making two significant contributions. First, I develop a theory of firm position-taking from the existing literature,Footnote 9 integrating major theoretical perspectives and identifying new influences on firm policy positions. Second, building on these firm-level micro-foundations, I provide a theory of position-taking by business coalitions that explains coalition unity and fragmentation in the face of environmental policy reforms. I coin the term “coalition splintering” to describe a situation where some firms break ranks from their business coalition to support environmental regulation.

My firm-level model identifies three drivers of position-taking: distributional effects, stakeholder pressure and policy inevitability. In developing this model, I empirically identify and theorize three new dynamics affecting firm position-taking. First, I show that stakeholder pressure can influence firms’ genuine preferences for environmental policy when firms see regulation as a way of lifting the environmental performance of an industry and improving an industry’s shared reputation—a reputation which can have significant commercial value to firms. This empirical finding suggests that a broadening of the traditional conception of a firm’s genuine preferences as always dictated by the distributional effects of public policy is required. Second, while the influence of NGOs and public opinion on position-taking is well-established, I find that investors can wield substantial influence. Third, I show that firms consider their relationships with peers in how they position themselves on environmental policy. Firms want to maintain an effective business coalition and their influence within it given the multi-domain, multi-round policy-making contests in which they engage, and can consequently be reluctant to break ranks to support environmental policy, even if they have a genuine preference for regulation. Internal business coalition dynamics, in other words, can lead firms to adopt a position of “strategic opposition” to environmental policy.

My firm-level model provides the micro-foundations for a theory of position-taking by business coalitions: a group of firms that have durable relationships and coordinate activities across multiple issues, including through industry-specific associations.Footnote 10 I delineate three ways business coalitions can be positioned on environmental regulation: unified opposition, division and unified support. Unified opposition to environmental policy results from a combination of widespread negative distributional effects, low policy inevitability, and anti-regulatory stakeholder pressure on firms, including from business coalition peers. Division or “coalition splintering” is most likely when some firms within a business coalition either benefit economically from regulation (or can easily absorb its costs) and are under intense pro-regulatory stakeholder pressure over an environmental issue. Stakeholder pressure can lead firms to see environmental regulation as reputation-enhancing for their industry, and ensures a policy position in support of regulation delivers reputational benefits. Finally, unified business support is driven by high policy inevitability and pro-regulatory stakeholder pressure, which shift oppositional members of a coalition to positions of strategic support despite the distributional costs they incur from environmental regulation.

I substantiate my theoretical model using an original case study of oil and gas company position-taking on the federal regulation of methane emissions in the United States between 2014 and 2021. My case represents a significant empirical contribution as one of the only political-economy studies of this substantively important area of climate policy;Footnote 11 globally, oil and gas methane emissions need to decline by almost 80 percent between 2020 and 2030 to limit global warming to 1.5°C.Footnote 12 Further, my case is one of few to go beyond a static, point-in-time assessment of business position-taking to analyze the dynamic nature of firm and coalition positions in multi-round environmental policy-making.Footnote 13

Existing theoretical accounts of business position-taking

Three theoretical perspectives frame the debate over the determinants of business position-taking on public policy.Footnote 14 All start from the point that firms are rational actors that pursue economic goals to ensure their ongoing survival.Footnote 15

Neo-materialist studies take the view that the distributional effects of an environmental policy—generally construed as the direct economic consequences of a policy for a firm—determine business position-taking.Footnote 16 A second group of scholars—rational choice institutionalists—emphasize that firm position-taking has a strategic dimension, distinguishing between a firm’s “genuine” or “sincere” preferences and its “strategic,” “induced” or “policy” preferences.Footnote 17

A third theoretical perspective—historical institutionalism—suggests that firms often confront situations of great uncertainty where their economic interests are unclear, and that institutional context therefore shapes firms’ view of their economic self-interest.Footnote 18 In historical institutionalist explanations, the impact of institutional context on firm behavior is often mediated by firm-level factors, including organizational culture and historical experience,Footnote 19 organizational structure,Footnote 20 and internal policy expertise.Footnote 21

The business management literature offers conceptual tools to enrich these existing theoretical perspectives on firm position-taking—a literature that remains largely untapped in political science.Footnote 22 While business scholars have rarely been concerned with position-taking specifically, they have generated a substantial literature exploring stakeholder influence on firm behavior.Footnote 23 Stakeholders exert such influence because a firm’s relationships and reputation have a financial value, helping firms to hire, retain and motivate employees;Footnote 24 attract investors and lower borrowing costs;Footnote 25 and influence policy.Footnote 26 The next section brings this strand of the business management literature to bear on firm and business coalition position-taking.

Theorizing firm and business coalition position-taking

A model of firm position-taking

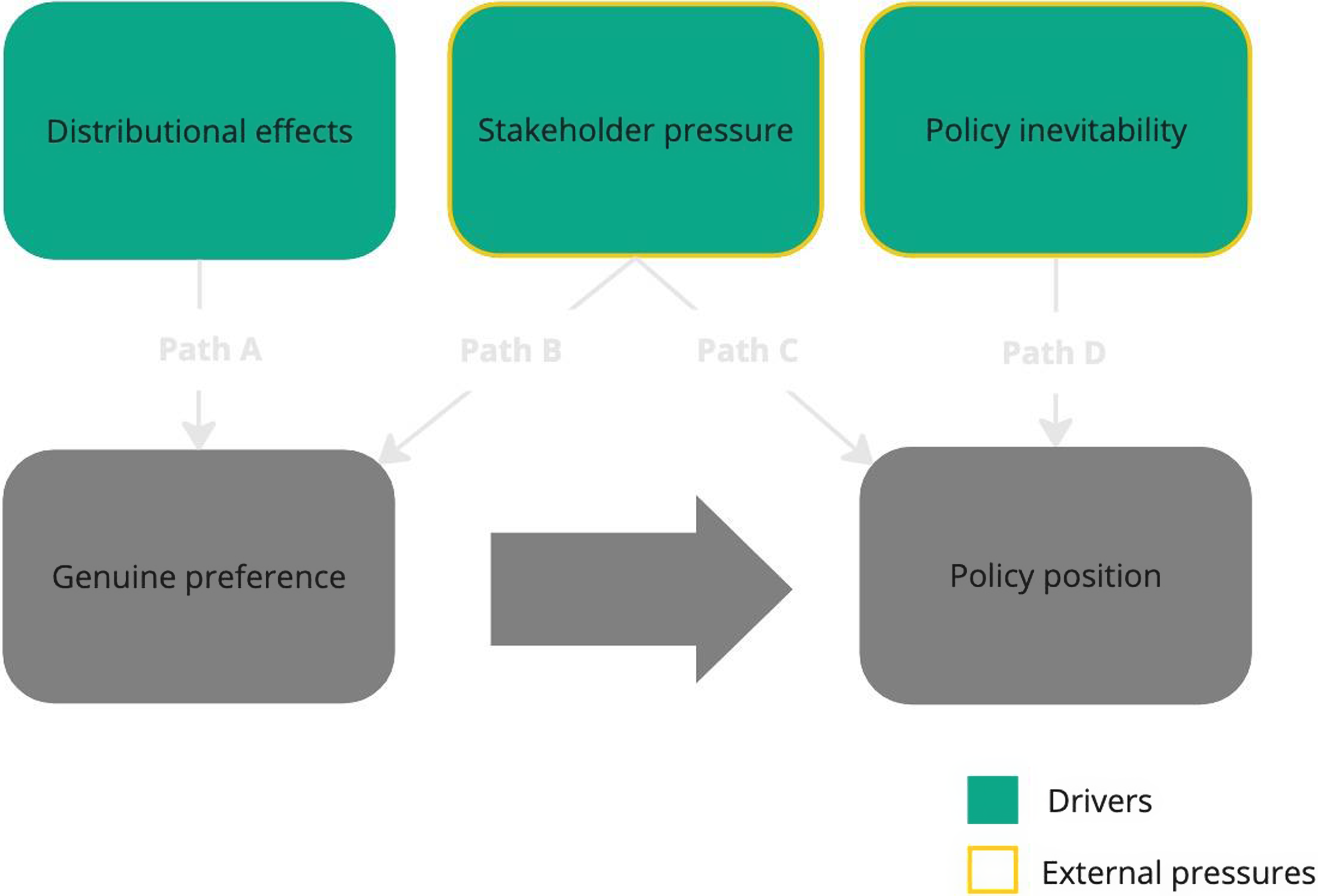

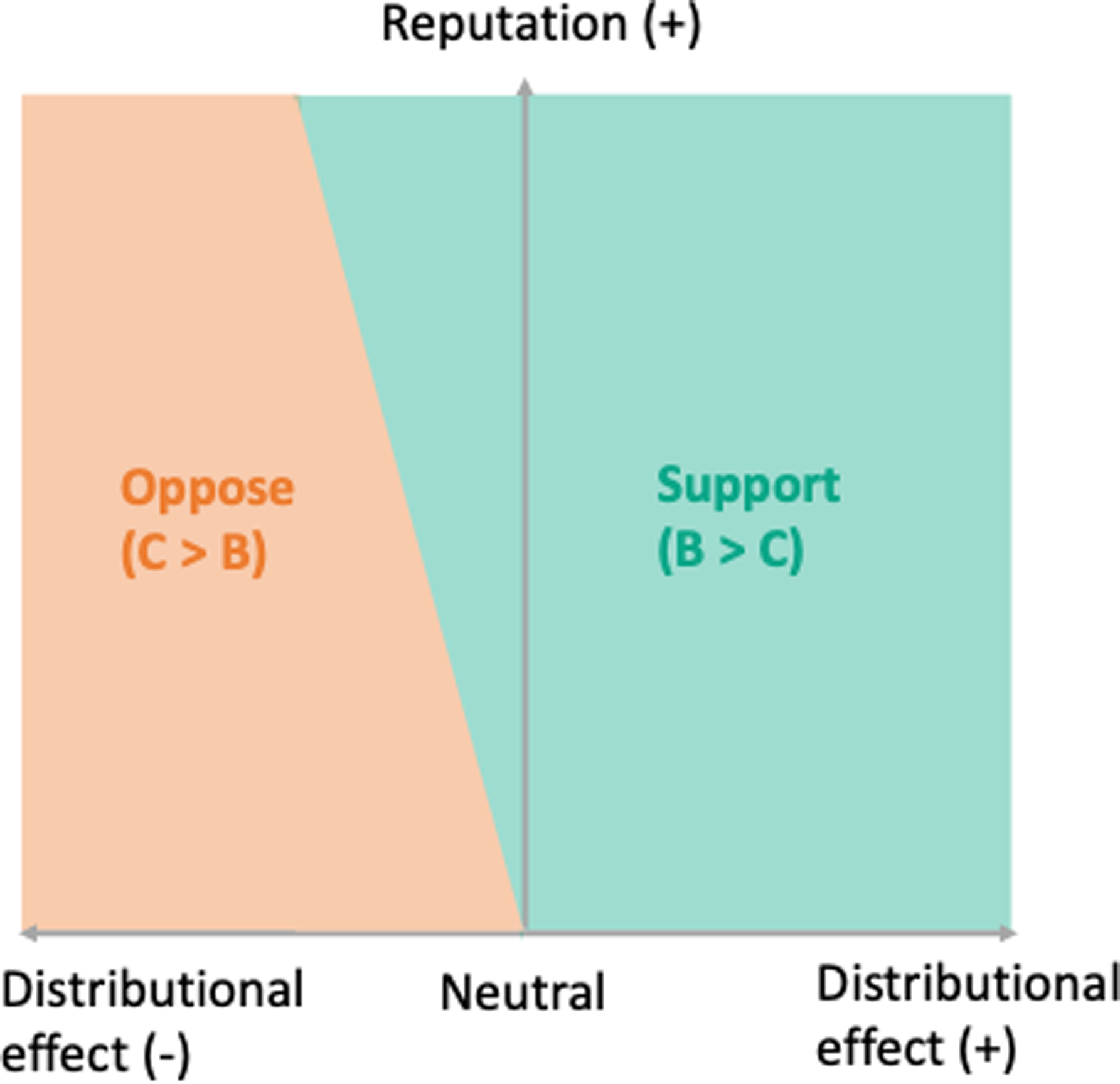

This section provides an explanatory model for firm position-taking on environmental policy, building on a model proposed by Vormedal and Meckling (Reference Vormedal and Meckling2023) by offering conceptual modifications and identifying new influences on firm policy positions. Figure 1 sets out the model. The model distinguishes between a firm’s genuine preference for environmental policy and its policy position (i.e., its “position-taking”). Three key drivers shape firm position-taking: the distributional effects of the policy, stakeholder pressure, and policy inevitability. These three drivers influence firm position-taking through four pathways (A, B, C and D). Figure 2 and Figure 3 specify the functional relationship between the model’s five variables: the three drivers, and a firm’s genuine preference and policy position. Finally, each driver works through different mechanisms to influence position-taking, as set out in Table 1.

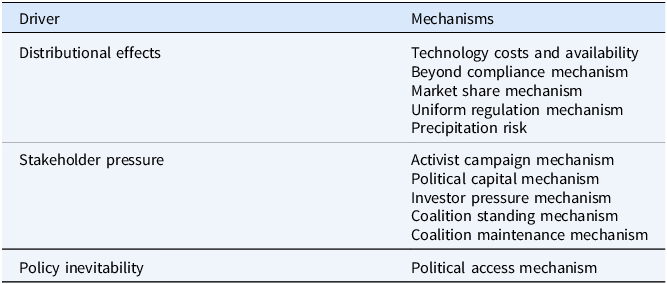

Table 1. Drivers of firm position-taking and associated mechanisms

Notes: builds on Vormedal and Meckling (Reference Vormedal and Meckling2023)

Figure 1. Model of firm position-taking on environmental policy.

Figure 2. Firm’s genuine preference for environmental policy. Notes: Trade-off between reputation and distributional effect indicative only. C = costs of policy; B = benefits of policy.

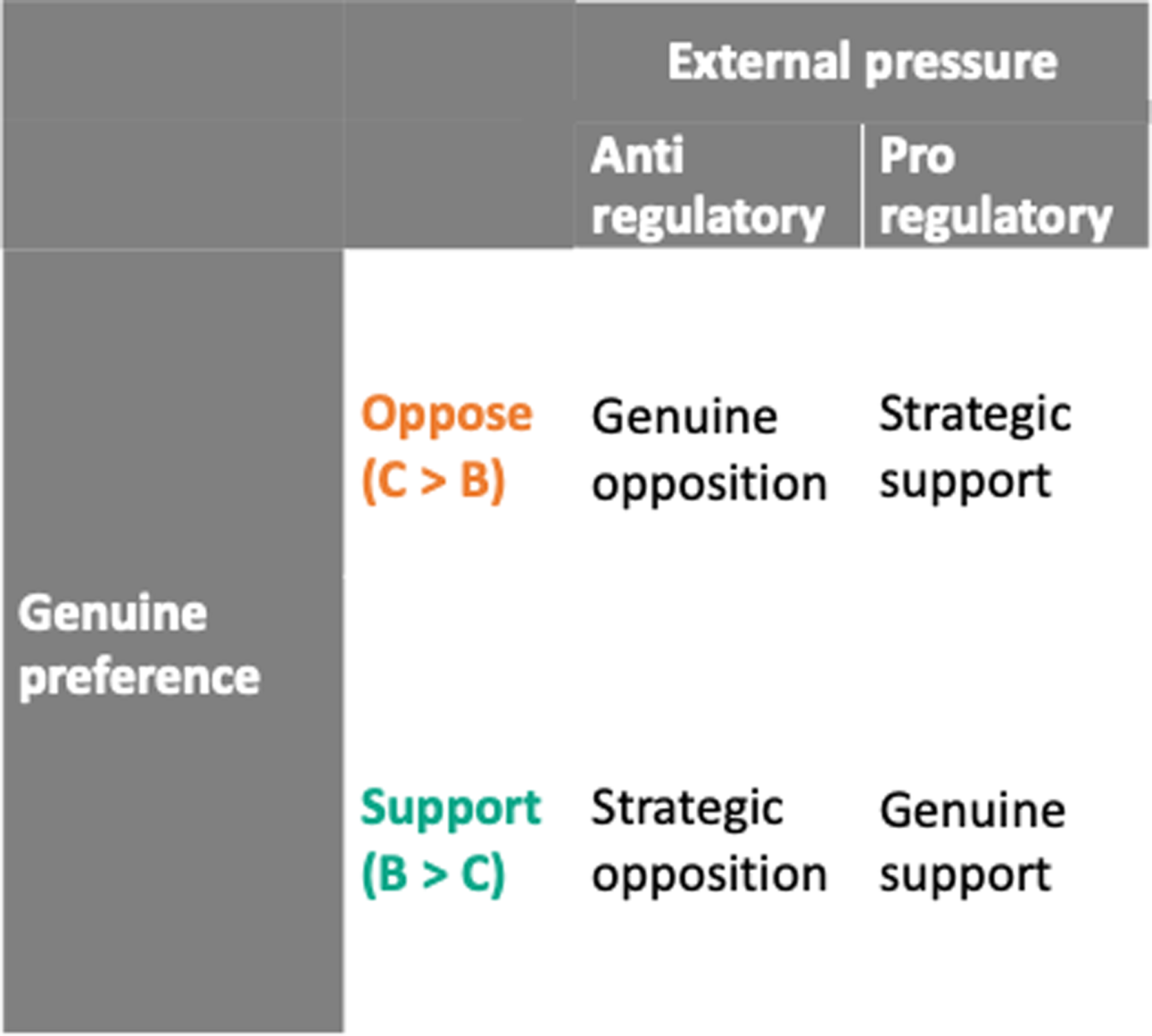

Figure 3. Firm’s policy position on environmental policy. Notes: Based on Meckling (Reference Meckling2015); Vormedal and Meckling (Reference Vormedal and Meckling2023).

Genuine preferences

A firm’s genuine preference reflects its preferred policy outcome. I consider a firm’s genuine preference to take one of two values: support or opposition to an environmental policy. I assume genuine preferences are determined by a firm’s assessment of the overall costs and benefits of a policy. In my model, a firm’s assessment of overall policy costs and benefits takes into account both the anticipated distributional effects of a policy (Figure 1, path A) and the anticipated effects of the policy on a firm’s reputation among its stakeholders (Figure 1, path B).

The distributional effects of environmental policy shape firm preferences because firms are driven by economic goals. The extant literature shows that technology costs and availabilityFootnote 27 and the extent to which firms are already taking “beyond compliance” action in line with a proposed environmental regulationFootnote 28 are two key mechanisms affecting firms’ adjustment costs to new regulation (Table 1). Firms evaluate their adjustment costs relative to their competitors, and may support regulation to impose a cost on competitors if the costs they face under regulation are offset by gains in market share (market share mechanism).Footnote 29 For example, environmental regulation can present large firms with “predatory opportunities” to gain market share from smaller rivals who are asymmetrically burdened.Footnote 30 Firms may also back environmental regulation at a higher-level jurisdiction to avoid the costs of multiple regulatory regimes at lower-level jurisdictions (the uniform regulation mechanism).Footnote 31

I show empirically that another previously unidentified mechanism underpins a firm’s assessment of the distributional effects of environmental policy: precipitation risk (Table 1). Precipitation risk refers to the risk that taking a policy position in favor of environmental regulation—or even failing to oppose it strongly enough—leads to policy outcomes that are detrimental to a firm. While it is well-established that anticipated distributional consequences shape firms’ policy positions, precipitation risk captures an important but underappreciated dynamic: that firms’ policy positions shape anticipated distributional consequences.

My model also captures another new empirical finding: that stakeholder pressure can influence a firm’s genuine preference for environmental regulation (Figure 1, path B). Firms’ concern with their reputation is the causal link between stakeholder pressure and genuine preferences. A firm’s reputation is shaped not only by its own activities, but also by the reputation of the industry in which it operates. An industry’s reputation is “held in common by firms”Footnote 32 or, put another way, firms’ reputations are subject to “spillover harm”Footnote 33 from the actions of other firms in their industry. Stakeholder pressure shapes firms’ genuine preferences for environmental regulation when firms see regulation as a way of enhancing their industry’s and their own reputation. Environmental regulation can improve the environmental performance of an industry, and particularly of an industry’s worst environmental performers whose activities may be doing significant damage to the industry’s shared reputation. Previous research has shown that firms sometimes create self-regulation to manage reputational interdependence within an industry,Footnote 34 and I demonstrate firms sometimes see government regulation as serving a similar function. I show that firms sometimes believe reputational gains from environmental regulation will help them achieve desirable commercial outcomes in a range of areas, including raising capital, recruitment and policy advocacy.

My model implies that firms may make trade-offs between the distributional and reputational effects of an environmental policy when assessing their genuine preferences. As Figure 2 shows, a firm may have a genuine preference in favor of an environmental policy under which it incurs costs, if these costs are sufficiently low and the reputational benefits of policy sufficiently high.

Policy position

Closely following previous scholarship,Footnote 35 I identify four ideal-type policy positions that firms take on environmental regulation: genuine support, genuine opposition, strategic support and strategic opposition (Figure 3).Footnote 36 A firm’s policy position depends on both its genuine preference and the type of external pressure it confronts (Figure 3). External pressure can be either pro-regulatory or anti-regulatory, depending on the firm’s judgment of the overall balance of external pressures that it faces. External pressure can lead a firm to disguise its genuine preference for environmental regulation by adopting a policy position of strategic support or strategic opposition. Alternatively, external pressure can reinforce a firm’s genuine preference.

In my model, external pressure on firms takes one of two forms. First, external pressure can take the form of policy inevitability (Figure 1, path D). Policy inevitability is pro-regulatory if a firm believes environmental policy adoption is likely or inevitable, and anti-regulatory if environmental regulation will be repealed. The existing literature documents how, when policy inevitability is high, firms have an incentive to align their policy position with that of government to gain access to decision-makers and enhance their influence on a policy’s design.Footnote 37 In such a situation, firm position-taking reflects “strategic accommodation”Footnote 38 —an effort to prevent radical policy change by supporting more moderate proposals.Footnote 39

Second, external pressure can take the form of stakeholder pressure (Figure 1, path C). A firm’s business coalition peers are one source of stakeholder pressure. The influence of a firm’s peers on its policy position stems from the fact that business coalitions engage in policy contests across multiple domains and multiple rounds. This creates an imperative for firms to consider their relationships with others in their business coalition in their position-taking. Stakeholder pressure from a firm’s peers is often anti-regulatory—opposing environmental policy often best serves a firm’s relationship with its business coalition allies. However, the balance of peer pressure can flip to pro-regulatory under certain circumstances, where speaking out against regulation is unfavorable to achieving a business coalitions’ policy objectives.

I empirically identify and theorize two new mechanisms related to business coalition dynamics that influence a firm’s policy position. The coalition standing mechanism captures how a firm’s policy position is shaped by the desire to maintain influence within its business coalition. Companies which break ranks from their business coalition risk losing respect and influence with their peers because position-taking has consequences for all firms in the industry. One oil and gas company executive respondent described how concerns about maintaining influence affect firm position-taking:

“Unless your company really is just going to sort of plant a flag on a particular issue and doesn’t care what the potential fallout might be, you don’t want to let one issue compromise your ability to affect other issues in the industry, too much.”Footnote 40

The coalition maintenance mechanism captures how a desire to maintain an effective business coalition shapes firm position-taking. Firms recognize that maintaining an effective business coalition across different forums and over time requires compromise on policy positions. As one company executive described:

“There definitely is…a desire to play nice more often than not, right? It’s better if we can come to some kind of consensus position than to have real strong outlier positions that then create all sorts of issues externally and internally.”Footnote 41

Another respondent from an oil and gas company also pointed to maintaining coalition unity as a consideration driving firm position-taking, noting “There’s a feeling that industry can’t advocate effectively…if industry is always being divided and conquered.”Footnote 42

Firms also face pressure from stakeholders outside their business coalition over their policy position. Previous research has highlighted an activist campaign mechanism where NGO and public pressure on firms spur strategic support for environmental policy.Footnote 43 Another mechanism recognized in the extant literature is the political capital mechanism.Footnote 44 Political parties want support from business for their policy agenda, and firms consider how their policy positions will affect their relationship with political elites. I also identify another mechanism affecting firm position-taking not captured in the extant literature. While previous research has shown that investor pressure can lead firms to adopt measures to enhance corporate social performance,Footnote 45 I show that investors can specifically influence firm position-taking (investor pressure mechanism). Firms consider their relationship with investors in their position-taking because investors are the owners of the firm, sources of capital, and can drain firm resources and inflict reputational damage on firms and their executives through shareholder resolutions and board votes.Footnote 46

In sum, stakeholder pressure features in my model twice: it shapes a firm’s genuine preferences because environmental regulation itself can have reputation-enhancing effects (Figure 1, path B), and it shapes a firm’s policy position because position-taking has consequences for corporate relationships and reputation, either good or bad (Figure 1, path C).

A model of business coalition unity and fragmentation

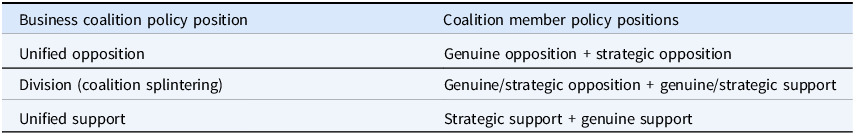

Building on my firm-level model, this section develops a theory of position-taking by business coalitions—one of the first efforts to theorize position-taking by coalitions of firms.Footnote 47 My theory of business coalition unity and fragmentation sets out the conditions under which coalitions of firms are united or divided over environmental policy reforms. It identifies three ideal-type policy positions taken by coalitions of firms: unified opposition, division (i.e., coalition splintering), and unified support (Table 2).

Table 2. Business coalition policy positions

First, business coalitions can take a position of unified opposition to environmental policy. Unified opposition consists of firms that genuinely oppose environmental policy, and sometimes firms that strategically oppose environmental policy (Table 2). Distributional effects, stakeholder pressure and policy inevitability can all contribute to unified opposition. Distributional effects contribute to unified opposition when environmental policy imposes costs on firms that are sufficient to rule out the possibility of genuine preferences in favor of environmental regulation (i.e., all firms are too far left on Figure 2). Similarly, anti-regulatory stakeholder pressure on firms, such as from their peers, creates strong incentives for firms to hold the line against environmental policy. Finally, low policy inevitability facilitates unified opposition because firms see an opportunity to prevent environmental regulation through strong opposition.

Second, business coalitions can fracture, and competing positions of support and opposition to environmental policy can emerge. Such “coalition splintering” occurs when firms defect from their coalition’s position either because they genuinely support environmental regulation or because they strategically support environmental regulation. Distributional effects can forcefully fracture existing coalitions when a policy’s material consequences are significant and clear cut. For instance, the lifting of restrictions on crude oil exports from the United States pitted the material interests of producers against refiners.Footnote 48 Other times, distributional effects may combine with stakeholder pressure to promote coalition splintering. Pro-regulatory stakeholder pressure on industries and firms over an environmental issue increases the chances of coalition splintering, especially when it falls on lower-adjustment cost firms, by creating reputational payoffs to both having and supporting environmental regulation. Policy inevitability can contribute to coalition splintering if firms take different views on the likelihood of environmental regulation succeeding. The chances of coalition splintering are highest when distributional effects, reputational incentives and views on policy inevitability simultaneously encourage potential defectors to break ranks.

Third, business coalitions can take a position of unified support for environmental policy. Unified support consists of positions of strategic and potentially genuine support for environmental regulation (Table 2). Unified support is driven by high policy inevitability and pro-regulatory stakeholder pressure, which shift firms which genuinely oppose environmental regulation to positions of strategic support despite the distributional costs they incur under the policy.

Method

Methane is a greenhouse gas released during the production and transportation of oil and gas. I study oil and gas company position-taking in the key policy battleground over oil and gas methane emissions in the United States between 2014 and 2021: the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) New Source Performance Standards (NSPS) for oil and gas under the Clean Air Act (40 CFR 60 Subpart OOOOa). The NSPS were so significant because they not only established regulations for “new” oil and gas facilities (i.e., those constructed or modified after 18 September 2015), but also triggered a requirement for the EPA to develop similar regulations for “existing sources”—the United States’ far larger existing oil and gas infrastructure. Methodologically, the NSPS provide a rare opportunity to study the evolution of business position-taking for the same environmental policy over time, controlling for changes in the policy itself and allowing the impact of other factors to be discerned. The NSPS were established under the Obama Administration, rescinded under the Trump Administration, and reinstated by the Biden Administration.

I focus on position-taking by the upstream and midstream of the US oil and gas industry. The upstream explores for and produces oil and gas, while the midstream transports and stores these commodities. Most upstream companies in the United States are “independents,” which range in size from tiny companies to some of the world’s largest. The seven oil and gas “majors”—large, integrated, international oil and gas companies headquartered in the United States (ExxonMobil, Chevron and ConocoPhillips) or Europe (Shell, BP, Total and Eni)—also operate in the United States.

I use process tracing to unpack the different factors influencing oil and gas company position-taking on the NSPS between 2014 and 2021. Drawing on 71 confidential interviews conducted between 2022 and 2024, I reconstruct the broader political, technological and scientific context around methane emissions; track investor and NGO pressure on companies; and dissect the drivers of corporate position-taking.Footnote 49 Significantly, I conduct rarely-obtained interviews with senior representatives from US oil and gas companies (n = 13) and trade associations (n = 15)—the first on the industry’s stance on methane regulation and amongst only a few on the industry’s climate policy positions.Footnote 50 These include interviews with companies that broke ranks from their peers to support federal regulation as well as with opponents of federal regulation. I also interview investor and investor organizations (n = 10); NGOs (n = 8); congressional staffers (n = 4); government officials (n = 4); scientists (n = 3); methane technology industry representatives (n = 4); and experts on the oil and gas industry (n = 10).

In addition, I examine thousands of pages of internal documents from the American Petroleum Institute (API) and four major companies—ExxonMobil, Chevron, BP and Shell—released by a congressional inquiry to gain further insight into internal dynamics within companies and industry.Footnote 51 I also undertake a comprehensive review of public statements from companies and trade associations, including industry submissions to EPA rule-making processes and media sources.

By studying business position-taking empirically, I confront the “problem of preferences”—that actors may disguise their true motives and preferences. I address this issue to the extent possible by tracing business position-taking across time,Footnote 52 strategic context,Footnote 53 multiple sources,Footnote 54 and through confidential interviews with company and industry insiders, as well as with those who worked closely with industry.

Finally, my case lends itself to the use of a simple distinction between business support and opposition to environmental policy, given that between 2014 and 2021 companies largely took positions on whether there should be federal methane regulation, rather than what form it should take. As such, the genuine support by companies for methane regulation that I report in this study reflects support for some form of regulation, with the stringency of methane regulation that companies were willing to support unclear.

US case study

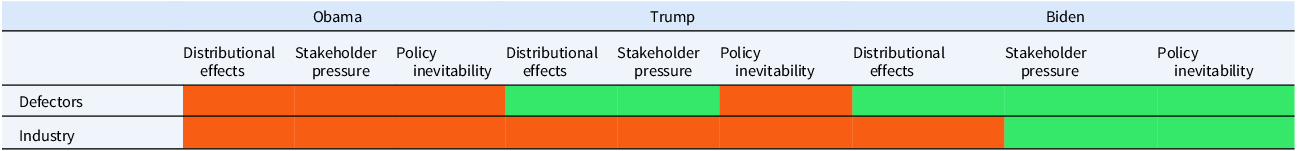

This section substantiates my theory of firm and business coalition position-taking using a case study of the oil and gas industry’s position on federal methane regulation under the Obama, Trump and Biden Administrations. I find that the oil and gas industry was united in opposition to Obama-era methane regulation but that coalition splintering occurred under the Trump Administration, before industry reunified to support federal regulation under the Biden Administration. Appendix 1 sets out how different drivers worked to either unite or divide industry under each Administration.

The Obama Administration: unified opposition

Context

Obama came to office in January 2009 against the backdrop of an accelerating shale oil and gas revolution in the United States. From 2011, science began emerging suggesting that methane emissions from the US oil and gas industry were being underestimated.Footnote 55 After the failure of cap-and-trade in Congress in Obama’s first term, Obama pivoted towards a climate policy strategy based on executive action. In March 2014, the Administration released its methane emissions strategy, flagging the potential for EPA regulations for the oil and gas industry.Footnote 56 Two years later, in June 2016, the EPA finalized regulations for methane from “new” oil and gas facilities, triggering a requirement under the Clean Air Act to extend the regulation of methane to “existing sources”—the United States’ older and much larger oil and gas infrastructure.

The oil and gas industry united in opposition to the Obama Administration’s efforts to regulate methane. The industry’s trade associations, and over thirty individual upstream and midstream companies, publicly opposed the EPA’s regulations or argued for a less stringent regulatory regime.Footnote 57 Meanwhile, the oil and gas majors either noted their support for their trade associations or remained silent on their position on the regulations. A small number of companies had a genuine preference for federal regulation and were willing to back it privately, either within the industry’s trade associations or with regulators and policymakers.Footnote 58 However, none made a public statement to this effect.

Drivers of business position-taking

The oil and gas industry’s position on federal methane regulation under the Obama Administration largely reflected widespread genuine opposition, although a few companies strategically opposed federal regulation. Genuine opposition was driven by the anticipated distributional effects of the policy (Figure 1, path A). Federal regulation of new oil and gas facilities entailed a new cost for industryFootnote 59 and, looking forward, would result in further costs by requiring the EPA to expand the regulation of methane to existing oil and gas infrastructure.Footnote 60 This eventual expansion of regulations to existing sources was a particular concern for companies: the regulation of new sources represented, in the words of one company executive, “the camel’s nose under the tent.”Footnote 61

A major driver of genuine opposition to the regulations was precipitation risk—that any industry support for the policy would result in “more regulation rather than less,” as one company official put it.Footnote 62 Similarly, a company executive described how precipitation risk was central to how the industry’s CEOs had historically seen methane regulation: “It is a slippery slope. If we give an inch, gosh knows where it will stop. And so we have to hold the line and be opposed in all respects to further regulation.”Footnote 63

The balance of external pressure on companies contributed to genuine opposition, as well as strategic opposition from companies who were willing to support federal regulation privately. First, there was anti-regulatory stakeholder pressure on companies to present a united front against EPA regulation (Figure 1, path C), with companies that broke ranks considered “heretics” by many in industry.Footnote 64 Companies factored in how their policy positions would affect their influence within their business coalition (coalition standing mechanism). “We weren’t going to take on API,” recalled an executive from a company that privately supported federal regulation under the Obama Administration. Companies that stepped out on particular regulatory provisions did lose standing within their business coalition, coming under pressure from peers. This pressure took the form of CEO-to-CEO lobbying or exclusion from industry trade association forums. According to a company official, powerful voices within industry felt they “needed to circle the wagons and anyone who spoke out of line needed to be silenced” and “those groups [trade associations], they can basically isolate you out of those so that your voice does not get heard.”Footnote 65 Company position-taking was also driven by the need to maintain an effective business coalition (coalition maintenance mechanism). “We had our opinion, but we also wanted to be a team player too,” recalled an executive from a company that privately favored federal regulation.Footnote 66 “You shouldn’t lightly go off on our own,” commented another company official, noting that a company’s aim is to maintain their coalition and move the coalition’s position towards its own.Footnote 67

While anti-regulatory stakeholder pressure on companies was significant, the industry faced limited pro-regulatory stakeholder pressure over methane emissions (Figure 1, paths B and C). NGOs—led by the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) and the Clean Air Task Force (CATF)—had been working to raise the profile of methane as an issue since the beginning of the decade. However, through most of the Obama Administration, natural gas was still widely viewed as a transition fuel. In June 2013, in a major speech on the Administration’s climate policy agenda, Obama identified natural gas as key to achieving US climate goals: “And, again, sometimes there are disputes about natural gas, but let me say this: We should strengthen our position as the top natural gas producer because, in the medium term at least, it not only can provide safe, cheap power, but it can also help reduce our carbon emissions.”Footnote 68 Companies were also under limited pressure from their investors. Investor organizations would not begin work on methane until 2015Footnote 69 and it would take some time for pressure on companies to build.

Finally, policy inevitability was low (Figure 1, path D). Although the Obama Administration was certain to adopt methane regulation, the industry had launched legal challenges over whether methane could be regulated under the Clean Air Act which had not been resolved—the possibility that methane regulation could still be derailed legally remained. Moreover, the timing of the expansion of methane regulation to cover existing sources was far from inevitable—industry opposition could potentially delay existing source regulation even if legal challenges fell over.Footnote 70

Summing up, under the Obama Administration, policy inevitability and pro-regulatory stakeholder pressure over methane emissions were low, while distributional costs and anti-regulatory pressure within industry were more significant—the result was widespread, unified and mainly genuine opposition to federal policy.

The Trump Administration: coalition splintering

Context

Trump came to the presidency in January 2017 promising American energy independence and moved to dismantle several key Obama-era climate policies, including for oil and gas methane emissions.Footnote 71 In September 2019, the Trump Administration proposed amendments to Obama-era regulations to eliminate controls on methane emissions for both the upstream and midstream of the industry.Footnote 72

Faced with the rollback of federal regulation, splits in the oil and gas industry’s position began to appear. Under the Trump Administration, a total of 12 companies publicly supported federal methane regulation, with ExxonMobil followed by three large European oil and gas companies—BP, Shell and Equinor—the first to take this stance (Table 3 and supplementary materials). Public position-taking appears to have reflected private positions for at least some firms that supported federal regulation. According to one company executive, the contest between the independents who opposed federal regulation and majors who supported it “almost broke up API and created a lot of tension…It was a serious rift.”Footnote 73 Similarly, a former EPA official reported that companies’ private positions generally reflected their public ones in discussions with the agency.Footnote 74 However, this was not the case for all firms that publicly backed federal regulation, according to one executive reporting on other companies’ private positions.Footnote 75 Further, defense of Obama-era methane regulation was not unequivocal. At least some companies that opposed the full rollback of regulation were open to changes to the rules to make them “more reasonable and workable.”Footnote 76

Table 3. First public statements of support for federal methane regulation by companies and trade associations, 2014–2021

Notes: API (American Petroleum Institute); CLNG (Center for Liquefied Natural Gas); INGAA (Interstate Natural Gas Association of America)

Sources: see supplementary materials.

The wider oil and gas industry supported the Trump Administration’s approach. The industry’s trade associations almost unanimously backed deregulation.Footnote 77 As one trade association official put it, “When Trump came in, the industry said ‘we can get out from under this’.”Footnote 78

The defectors: drivers of business position-taking

What had happened to cause a small group of companies to break from the broader industry and declare their support for the federal regulation of methane when just a few years before industry was united against this very approach? In line with my model of business coalition unity and fragmentation, I suggest that coalition splintering was driven by growing pro-regulatory stakeholder pressure over methane emissions and shifting firm views on the distributional impacts of methane regulation.

Distributional effects

By the Trump presidency, some firms were re-evaluating their view on the distributional effects of federal methane regulation—a key factor shaping firms’ genuine preferences for environmental policy (Figure 1, path A). Several factors were behind this shift.

First, there had been significant falls in the costs of methane detection and mitigation, as well as an expansion in the types of technologies available (technology availability and cost mechanism).Footnote 79 For large companies, “the problem looked increasingly solvable” and methane abatement costs were “real but not material.”Footnote 80

Second, by the time of the Trump Administration, some companies had already taken steps to reduce their methane emissions—any rollback of regulation would leave them “beyond compliance” given continued pressure on them to reduce methane emissions from investors, NGOs and others (the beyond compliance mechanism).Footnote 81 As one trade association official put it and others emphasized, large companies found federal regulation “an easy thing to support because they were already doing it.”Footnote 82 Companies had begun taking steps to address their methane emissions partly because of the increasing risk of future regulation. The development of Obama-era methane regulations for new sources highlighted the risk that existing sources might one day be regulated, as the Clean Air Act required. Meanwhile, state action on regulating methane—including across Colorado, California, Ohio, Pennsylvania and New MexicoFootnote 83 —suggested that regulation would continue to spread or tighten at the state level. Another major driver of company efforts to reduce their own methane emissions was stakeholder pressure, particularly from investors. Such stakeholder pressure indirectly affected position-taking by spurring company efforts to tackle methane that in turn changed the distributional effects of regulation (Figure 1, path A), and also directly influenced company position-taking (Figure 1, paths B and C)—as discussed in the next section.

Third, the uneven patchwork of state-level regulations was becoming a burden for some companies that operated across multiple jurisdictions, with federal regulation a way to avoid the costs of regulatory fragmentation at the state-level (the uniform regulation mechanism).Footnote 84 For example, Dominion Energy—a company with an interstate pipeline business—appears to have backed federal regulation partly out of a desire for a uniform regulatory regime. As Dominion noted in 2019, “there is enough variation from one state to another that compliance will continue to be a challenge…a consistent and rigorous national standard is preferable.”Footnote 85

Finally, federal regulation may have offered an opportunity for companies that were doing more on methane emissions to impose a cost on competitors (market share mechanism). Company executives accused the oil and gas majors of supporting federal regulation as a means of “culling the herd” and putting their competition out of business, noting that the compliance costs of complex regulation were far lower for large, sophisticated firms.Footnote 86 Similarly, according to one trade association official, companies operating in states with methane regulation considered a federal standard as “leveling the playing field”Footnote 87 with competitors in other states, consistent with the idea that firms seek to “export” production standards to firms in less green jurisdictions.Footnote 88 However, interviewees from companies which supported federal regulation denied that competitive advantage was a motivation.Footnote 89 While competitive advantage may have been a factor to which executives were unwilling to admit, there is also ample evidence that large (and especially global) companies were thinking beyond these market share considerations to the much larger issue of the future of natural gas in the global energy transition, as I discuss in the next section.

Pro-regulatory stakeholder pressure

Perhaps the key factor leading companies to reassess their position on federal methane policy under the Trump Administration was increased pro-regulatory stakeholder pressure. This pro-regulatory stakeholder pressure had a dual effect on position-taking, influencing both genuine preferences (Figure 1, path B) and policy positions (Figure 1, path C).

Towards the end of the Obama Administration and through the Trump Administration, methane emissions were becoming an increasingly salient issue. A steady stream of studies suggested that oil and gas methane emissions were being underestimated in official statistics. EPA data did not account for “super-emitters”—the small number of high-emitting sites responsible for a large share of US oil and gas methane emissions.Footnote 90 An influential paper published in June 2018 found that methane emissions along the US oil and natural gas supply chain were approximately 60 percent higher than EPA estimates.Footnote 91

Alongside these scientific studies came increasing stakeholder pressure. The NGO campaign on methane had done much to raise the profile of methane emissions as an urgent but tractable issue with the industry’s stakeholders, building an evidence base; rallying other NGOs; lobbying regulators and policymakers at the state and federal levels; and engaging the media (activist campaign mechanism).Footnote 92 Footage of methane leaks shot by NGOs—such as the huge black plume over Los Angeles from the Aliso Canyon gas storage facility in October 2015—provided compelling visual material with which to raise stakeholder concern.Footnote 93 As the Trump Administration moved to wind back federal methane regulations, EDF directly pressured large companies to oppose the repeal.Footnote 94 Perhaps most crucially, however, by the time of the Trump Administration, NGOs had a powerful new ally: investors.

Investor pressure on companies over methane emissions had grown quickly (investor pressure mechanism). In the United States, EDF and investor networks—Ceres and the Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility (ICCR)—had begun work on oil and gas methane emissions around 2015. The campaign not only aimed to push companies to reduce their own methane emissions, but also called on companies to support federal regulation. A small but increasingly vocal minority of investors worked to “pick off companies” and “split the industry” in the knowledge that a divided industry was less well positioned to oppose regulation.Footnote 95 In late 2015, a letter to oil and gas companies by investor group ICCR had garnered support from a group of just 37 investors with assets of only $100 billion.Footnote 96 By December 2018, 61 investors representing $1.9 trillion in assets under management wrote to oil and gas companies urging them to oppose the Trump Administration’s rollback of methane regulations.Footnote 97 In August 2019, 140 investors with over $5.5 trillion in collective assets sent a similar statement to companies, asking them to support continued federal regulation.Footnote 98 As one company executive put it, “investors were telling companies, ‘you need to take this issue of the table’.”Footnote 99 Investors were an influential constituency with companies—the industry needed access to capital to drill its wells and build its pipes.Footnote 100

Pressure on the industry over methane emissions from other key stakeholders had also grown. Among democrats, methane emissions were damaging the industry’s reputation (political capital mechanism). One congressional staffer described how, under the Obama Administration, gas had “high popular support” and was a “bipartisan issue,” but that things had become a lot more polarized, noting that “a big reason for that shift is concerns around methane emissions.”Footnote 101 In addition, concern over the industry’s role in climate change was also being blamed for difficulties the industry was having in attracting skilled staff, with the number of petroleum engineering graduates halving between 2016 and 2021.Footnote 102

It was clear that stakeholder pressure associated with methane emissions was not going anywhere. Methane detection technologies were rapidly advancing, including satellite monitoring.Footnote 103 The industry confronted the prospect of greater scrutiny from the public, investors and NGOs.Footnote 104 “There will be nowhere to hide methane emissions,” wrote researchers from Columbia University in 2020 in a piece on satellite detection technologies.Footnote 105

In short, a broad-based consensus that gas was an important transition fuel was beginning to unravel during the Trump Administration. Companies’ stakeholders—investors, NGOs, political parties and the public—increasingly questioned the role of natural gas in achieving decarbonization objectives.

Large companies were acutely aware of the reputational damage methane emissions were inflicting. As the head of Shell United States stated in 2019, “our view is that any methane emissions—across the industry—hurts our business, because it hurts the reputation of natural gas.”Footnote 106 , Footnote 107 BP appears to have had a similar view of the reputational impacts of methane emissions, with an internal public relations strategy from 2018 pinpointing methane emissions as a way that some were seeking to “discredit gas as part of the future energy mix.”Footnote 108

Crucially, large companies could not escape the reputational damage associated with the industry’s methane emissions. As one trade association official noted: “No matter how much a company wants to differentiate itself…they are still part of the larger oil and gas industry.Footnote 109 Voluntary efforts by major companies to reduce their own methane emissions were not sufficient to mitigate this reputational damage. As BP noted, “Voluntary actions by several energy companies are not enough to solve the problem. These efforts will not have the industry-wide impact that we need and will not satisfy investors, consumers, policymakers or other stakeholders.”Footnote 110 Similarly, an official from a company that supported federal regulation recalled, “I think [my company] and others felt that it almost didn’t matter how well you performed. The oil and gas industry was under attack. And methane was the avenue.”Footnote 111

Large companies considered methane emissions to present a major risk if the problem was left unchecked. As an executive from a company that supported federal regulation under the Trump Administration noted: “the failure to adequately abate methane very quickly in the short term is a far bigger existential threat to the industry in the long term than the smaller companies might want to be thinking about.”Footnote 112 Future climate policy risks loomed large in the minds of industry executives. One executive noted that their company believed that without “a better track record on issues like methane emissions, that more onerous regulations would be coming down the pike.”Footnote 113 Another executive described how the overriding view within their company was that “Climate policy is the cost threat. And if we are not ahead of a changing dynamic in the policy landscape, then nothing else will really matter.”Footnote 114 The industry’s reputation amongst investors was also part of some companies thinking about the risks associated with methane emissions. As one company executive noted, “At a certain point, if the industry didn’t show improvement and show engagement on these issues, you would have seen investors start to peel away.”Footnote 115

Given the impacts of methane emissions on the industry’s shared reputation and the threat this posed to the industry long-term, stakeholder pressure influenced some companies’ genuine preferences for federal methane regulation, as my model captures (Figure 1, path B). Public statements from BP, ExxonMobil and Shell indicate they saw federal regulation as a way to protect the oil and gas industry’s and their own reputation with stakeholders (Figure 1, path B).Footnote 116 BP, for example, stated: “The best way to help further minimize methane emissions industry-wide and gain the confidence of a diverse group of stakeholders, is through direct federal regulation of new and existing sources.”Footnote 117 Multiple interviewees from companies that supported federal regulation confirmed that concerns over the industry’s reputation were a key driver of their companies’ policy position. As one put it, “One of the reasons to support regulation is…the perception of the industry…If you don’t have a grounding of policy, you can have all the blue-ribbon groups you want, the public won’t have confidence.”Footnote 118 Similarly, a company executive described how their company saw methane emissions as an existential risk and support for federal regulation from large companies as a means to address it:

“If the industry writ large lost its license to operate…[my company’s] not going to survive that… a big part of it was the bigger companies had to sort of force, in our opinion, had to be part of the raising of the bar on those issues… the issue was just too high profile and it was too much of a risk…to not take it head on.”Footnote 119

More specifically, federal regulation would manage reputational interdependence within the industry, helping mitigate the reputational damage being caused by the industry’s worst performers on methane emissions. ExxonMobil’s subsidiary XTO emphasized how the “correct mix of policies and regulations could help the entire industry raise the bar,”Footnote 120 with BHP, Equinor and Cimarex also making the case for a federal regulatory “floor” to promote industry-wide efforts.Footnote 121

Pro-regulatory stakeholder pressure also encouraged companies to support federal regulation in a second important way: it increased the reputational payoffs to companies of taking a policy position in favor of a federal approach (Figure 1, path C). The environmental NGO EDF publicized company statements in support of federal regulation,Footnote 122 providing reputational benefits for companies willing to speak out. Relationships with NGOs were a tangible consideration for some companies. As an executive from a company which backed federal regulation noted, “There was a desire to be seen as credible with moderate and even harder core environmental groups.”Footnote 123 Similarly, the investor campaign on methane sought to “elevate the leaders” within industry,Footnote 124 and investors commended announcements from oil and gas majors supporting federal regulation.Footnote 125 Investor backing appears to have been a material consideration for companies. As one investor respondent noted, company endorsement of methane regulation “doesn’t happen if they think it’s not a win with their investor base.”Footnote 126 However, it is important not overstate the reputational payoffs to companies with investors from a policy position in favor of federal regulation. As a company executive noted, while supporting federal regulation “sends a certain signal…I’d by lying if I told you that, you know, that moved a lot of capital.”Footnote 127

In contrast to the reputational benefits of taking a policy position in favor of federal regulation, staying silent on the Trump Administration’s rollback was a reputationally risky strategy for major companies. Trade association officials suggested that major companies did not “want to be perceived as having anything to do with this” and the way to achieve that was to “come out publicly.”Footnote 128 Companies that did continue to oppose federal regulation had to bear ongoing investor pressure over their policy position. As one company executive noted, “they kept trying to get us to join Exxon…they weren’t going to stop investing in us, but it was just kind of an undertow or a pull against us.”Footnote 129

The wider industry: drivers of business position-taking

While a small group of companies supported federal regulation under the Trump Administration, the industry by and large backed deregulation for several reasons. First, the anticipated distributional effects of regulation (Figure 1, path A) contributed to this continued opposition—regulation still represented an added cost for many firms.

Second, many companies which faced significant adjustment costs to regulation also faced far lower pro-regulatory stakeholder pressure—from investors, NGOs and the public—than large, publicly-owned, and highly visible oil and gas companies. As one company executive noted, investors were “going after the whales” and “investor pressure on the independents had not grown to the point that it was with them.”Footnote 130 Small operators faced little to no pro-regulatory stakeholder pressure at all. As an official from one investor group noted about small operators, “There’s just no pressure on them to do things better. And being a clean operator, unfortunately, isn’t a priority in this business model.”Footnote 131 Likewise private equity companies faced little scrutiny from investors, regulators and the general public, given weaker disclosure regulations than for public companies.Footnote 132

There was also anti-regulatory stakeholder pressure from the Trump Administration discouraging companies from adopting a policy position in favor of federal regulation (Figure 1, path C) (political capital mechanism). One company respondent reported pressure over companies’ policy positions from the political right, noting the “distaste for…politically woke businesses” in the Trump Administration and Republican party.Footnote 133 Similarly, an internal Shell email indicates public opposition to the rollback of federal regulation caused “heartburn” for the company with the Trump Administration.Footnote 134 Indeed, the desire to maintain good relations with the Trump Administration meant that some in industry flagged their opposition to the rollback with the Administration privately but stayed silent publicly.Footnote 135

Companies also considered what public support for federal methane regulation would mean for their relationships and political coalition with industry peers, with some respondents reporting CEO-to-CEO lobbying over company positions.Footnote 136 One executive from a company that supported federal regulation highlighted how the company’s policy position affected its influence with industry peers (coalition standing mechanism):

“We were kind of the cousin at the table that no one would have really cared if we had missed the holiday…I think we were treated pretty badly when we weren’t around…I think it did hurt us.”Footnote 137

Summing up, a split within industry over federal methane regulation opened up under the Trump Administration. The bulk of industry continued to oppose federal regulation, given the costs it would impose on their operations and a lack of pro-regulatory stakeholder pressure. However, a small group of mainly large, publicly-owned companies reassessed their view of the distributional effects of methane regulations; came to see federal regulation as a way of enhancing their industry’s and their own reputation; and seized the reputational payoffs from publicly supporting federal regulation. These considerations appear to have far outweighed policy inevitability as a driver of position-taking, which provided incentives for large companies to back the Trump Administration’s deregulatory agenda in order to influence its implementation.

The Biden Administration: realignment towards unified support

Context

In January 2021, Biden came to office promising to restore US leadership on climate change. The Biden Administration sought to unwind the Trump Administration’s rollback of methane regulation for new oil and gas facilities using the Congressional Review Act—the so-called “midnight rule”—which allows Congress to overturn rules issued by agencies at the end of the last Congress.

At the start of the Biden Administration, the industry at large began to reposition itself in favor of federal regulation. API—the industry’s largest and most influential trade association—stated its support generally for federal methane regulation, the strongest sign of an industry-wide pivot to a policy position in favor of a federal standard. In addition, two other federal trade associations announced their support for the Congressional Review Act resolution before the House and Senate votes in mid-2021, while the number of companies backing federal regulation grew by four (Table 3).

Drivers of business position-taking

The shift in the wider industry’s stance to a policy position in support of federal methane regulation partly reflected pro-regulatory policy inevitability (Figure 1, path D). Under the Biden Administration, the reinstatement of methane regulations appeared inevitable: democrats controlled both houses and the Congressional Review Act resolution required only a simple majority to pass. In addition, legal challenges to EPA’s authority to regulate methane had run their course.Footnote 138 Trade association officials noted that the “lawerly fights” under the Obama Administration had been resolved and “now the fight is on a workable rule.”Footnote 139 API’s decision to support federal regulation was in part an effort “to effectively engage the Biden Administration” and gain “a seat at the table” (political access mechanism), according to internal documents and public statements from the trade association.Footnote 140

In addition, a shift in the balance of anti-regulatory and pro-regulatory stakeholder pressure on firms under the Biden Administration may explain why more companies announced their support for federal regulation (Figure 1, path C). Firms faced far less anti-regulatory stakeholder pressure to oppose federal regulation—both from their peers within industry and from the Administration. Meanwhile, continued pro-regulatory stakeholder pressure from investors and NGOs made it costly for firms to oppose methane regulation publicly, and even opposing privately brought risks of a “PR nightmare” if a firm’s position was leaked.Footnote 141 In short, the combination of high policy inevitability and pro-regulatory stakeholder pressure generated unified business support for federal regulation by shifting companies that genuinely opposed regulation to a position of strategic support.

Conclusion

Position-taking by firms and business coalitions is a key dynamic influencing the scope and pace of climate and environmental policy reforms. Building on recent theoretical advances in the extant literature,Footnote 142 this article has developed a theory of firm and business coalition position-taking on environmental policy using an original and substantively important case study of federal US oil and gas methane regulation. The paper’s empirical findings demonstrate that stakeholder pressure can influence a firm’s genuine preference for environmental regulation, suggesting the traditional conception of a firm’s genuine preferences as dictated only by the direct distributional effects of public policy is sometimes too limited. My findings also highlight previously unidentified influences on firm position-taking: that investor pressure can push firms towards supporting environmental policy, while dynamics related to maintaining influence and cohesion within business coalitions often pull in the opposite direction. Coalition dynamics can lead firms to oppose environmental regulation even when they have a genuine preference to the contrary, suggesting that quiet pockets of business support for environmental reforms sometimes exist. Further research is needed to understand the scope conditions under which these newly-identified mechanisms are influential in shaping firm position-taking.

The theory developed in this article should be generalizable to understanding and anticipating business position-taking on climate policy in other high-emitting sectors. Methane emissions are scope 1 (direct) emissions for the oil and gas industry, much like methane and carbon dioxide are for other high-emitting industries in sectors like agriculture, mining and manufacturing. However, the conditions that led to coalition splintering over federal US methane regulation are not likely to materialize across all areas of climate policy. Tackling methane emissions is a tractable, technical problem for the oil and gas industry and abatement is relatively low cost, partly because captured methane represents natural gas that can then be sold. Where climate policy entails significant material costs for firms, distributional consequences will rule out the possibility of genuine support and encourage united opposition.

I conclude by underscoring the need for further research on the scope and pace of climate policy reforms that high-emitting industries can be expected to support. While high-emitting industries have often been cast as the opponents of climate policy, a growing number of scholars have argued that incumbents represent potential allies of policy reform.Footnote 143 However, while high-emitting firms may support some form of climate policy, the extent to which they are willing to support the breadth and depth of regulatory policy required to achieve global climate targets remains to be seen. In sum, there is much work to be done to understand both the possibilities and limits around when firms and industries might be “convertible” when it comes to supporting climate policy.Footnote 144 Such work will be needed to underpin thinking on policy-political pathways for decarbonizing a range of high-emitting industries.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/bap.2025.2

Acknowledgements

I gratefully acknowledge the support of the Sir Roland Wilson Foundation PhD Scholarship Program including financial support. I thank the three anonymous reviewers, Christian Downie, Jensen Sass, Barry Rabe and Gareth Williams for their many helpful suggestions and comments.

Appendix 1. Indicative drivers of position-taking of defectors and wider industry