In today’s rapidly changing global era, the nature of people’s online interactions in the workplace makes it challenging for organizations to foster a collaborative and ethical culture that embraces empathy in day-to-day operations (Nakamura, Milner, & Milner, Reference Nakamura, Milner and Milner2022a; Parker, Knight, & Keller, Reference Parker, Knight and Keller2020). With increasing demands in workload, leaders face challenges in fostering empathy among employees and creating a collaborative culture in their organizations (Groysberg & Slind, Reference Groysberg and Slind2012; Nakamura, Milner, & Milner, Reference Nakamura, Milner and Milner2022b).

This article examines the role of empathy in leadership ethics through a relational lens. There is a scholarly debate between entitative and relational views of leadership (Painter & Werhane, Reference Painter and Werhane2023; Pérezts, Russon, & Painter, Reference Pérezts, Russon and Painter2020; Uhl-Bien & Ospina, Reference Uhl-Bien and Ospina2012). Scholars exhibit a continuum of perspectives on the relational dimension of leadership, ranging from a modernist entity viewpoint to a postmodernist constructionist approach. These varied positions are reflected in their ontological worldviews (Ospina & Uhl-Bien, Reference Ospina, Uhl-Bien, Uhl-Bien and Ospina2012). On the one hand, an entity approach focuses on leaders, emphasizing their attributes and impact on others, engaging in interpersonal relationship processes. On the other hand, the constructionist approach sheds light on leadership as a process of social construction, wherein leadership is fluid and co-constructed between leaders and members of the organization (Fairhurst, Reference Fairhurst2007; Uhl-Bien, Reference Uhl-Bien2006). Leadership work is seen as a dynamic, ongoing process where conversations and relationships are key for effective leadership practice (Crevani, Reference Crevani, Carroll, Ford and Taylor2015). This relationality aspect highlights the importance of nuanced moral and emotional dimensions of leadership (Jansson, Døving, & Elstad, Reference Jansson, Døving and Elstad2021).

Concerning relational leadership, the role of empathy becomes salient. Empathy is seen as one of the critical components in this paradigm, and its construction is deeply rooted in leadership ethics (Jian, Reference Jian2021; Pohling, Bzdok, Eigenstetter, Stumpf, & Strobel, Reference Pohling, Bzdok, Eigenstetter, Stumpf and Strobel2016). The relational perspective of leadership ethics includes generosity, care, and responsibility that facilitate empathic interactions (Jian, Reference Jian2021). Ethical leaders are open and focused on others, exhibiting generosity instead of having a self-centered ego (Diprose, Reference Diprose2002; Liu, Reference Liu2017; Pullen & Rhodes, Reference Pullen and Rhodes2014). They pay attention to their presence in relation to the world, demonstrating attentiveness to others, caring for their well-being, and promoting healthy relationship building (Ciulla, Reference Ciulla2009; Gilligan, Reference Gilligan1982; Mayeroff, Reference Mayeroff1971; Nicholson & Kurucz, Reference Nicholson and Kurucz2019; Nodding, Reference Nodding2013). Additionally, they feel a sense of responsibility towards others (Levinas, Reference Levinas1985; Grandy & Sliwa, Reference Grandy and Sliwa2017; Rhodes & Badham, Reference Rhodes and Badham2018). This relational aspect, which emphasizes relation to others, illuminates the inevitable nature of emotion (Painter & Werhane, Reference Painter and Werhane2023). Held (Reference Held1990, Reference Held2006) argues that ethics of care is being responsible, valuing emotions alongside rationality, and embracing the relational and interdependent nature of human beings. Gilligan (Reference Gilligan1982) sheds light on the importance of ethics of care with an affective element, while Kohlberg focuses on rationality in decision-making as a higher order (Kohlberg & Hersh, Reference Kohlberg and Hersh1977).

Building upon these ethical cornerstones of generosity, care, and responsibility, individuals who practice empathy in leadership ethics not only understand others’ emotional state and share emotions but also create emotional bonds through a mutually constructive reflexive space (Cunliffe & Eriksen, Reference Cunliffe and Eriksen2011; Tzouramani, Reference Tzouramani, Marques and Dhiman2017). From this relational theoretical perspective on leadership ethics, such leaders have an open mind and demonstrate true care and value. For instance, individuals who feel responsible for others while grappling with multiple issues such as market demands, resource constraints, and environmental crises might enact empathy in leadership by understanding the needs of others and co-creating an environment where people support each other (Rhodes & Badham, Reference Rhodes and Badham2018).

From a relational perspective, scholars have emphasized that leadership occurs through a dialogic approach where communication is a two-way street between leaders and others, centered on mutually shared interests (Jian, Reference Jian2021; Nicholson & Kurucz, Reference Nicholson and Kurucz2019). Through these interactions, people collectively make meaning of their experiences, understand and embrace differences, and challenge underlying assumptions (Painter & Werhane, Reference Painter and Werhane2023). Their collective processes promote shaping their identity within organizations, communities, and societies (Ospina & Foldy, Reference Ospina and Foldy2020). In this context, there is an ongoing debate over the teachability of ethics in leadership development. While some argue that core moral values are formed early in life, others contend that ethical decision-making skills can be developed through targeted training (Felton & Sims, Reference Felton and Sims2005). Painter-Morland and Deslandes (Reference Painter-Morland and Deslandes2017) discuss how and why leadership ethics education should focus on developing practical wisdom within organizational contexts, emphasizing that ethical leadership involves navigating complex relational and systemic dynamics.

Our research employs an entity perspective in relational leadership, contributing to the relational leadership debate. By shedding light on the relationship between leaders and others beyond formal hierarchical organizational settings, we examine the role of empathy in leadership ethics. In a workshop setting, our study also aims to address this ethical leadership complexity through a learning space provided for leaders to explore challenges within their specific relational and cultural environments via virtual interactions.

PROBLEM, PURPOSE, AND RESEARCH QUESTIONS

Relationship-based leadership focuses on individuals and their perceptions and behaviors in interpersonal relationships with one another. There are studies that have examined relational leadership from an entitative perspective. These studies incorporated theoretical lenses such as the Leader-Member Exchange theory (Graen & Uhl-Bien, Reference Graen and Uhl-Bien1995), the social exchange relationship between leaders and followers (Hollander, Reference Hollander1995), and social cognition and social identity theory of leadership (Brewer & Gardner, Reference Brewer and Gardner1996; Hogg, Reference Hogg2001). Although this entitative view of research has been discussed in regard to its association with gender stereotypes, the ethics of care as affective areas, which are considered more feminine aspects, is an under-researched area (Pérezts et al., Reference Pérezts, Russon and Painter2020). Specifically, further exploration is warranted in regard to how empathy is manifested or diminished in relational spaces as dominant leadership expectations and social norms operate heavily on rationality needs as opposed to emotion-sensitive interactions. These challenges are further escalated in virtual environments, where people have fewer opportunities for collaborative interactions and building relationships that foster ethics of care in the workplace (Nakamura et al., Reference Nakamura, Milner and Milner2022a). Situations like this can contribute to demotivation, low productivity, and high turnover (Kniffin et al., Reference Kniffin, Narayanan, Anseel, Antonakis, Ashford, Bakker, Bamberger, Bapuji, Bhave, Choi, Creary, Demerouti, Flynn, Gelfand, Greer, Johns, Kesebir, Klein, Lee and Vugt2021), which warrants more investigation from a relational building perspective to help organizations navigate the current hybrid and virtual workplace.

However, limited research focuses on empathy in leadership ethics through a relational leadership lens (Cunliffe & Eriksen, Reference Cunliffe and Eriksen2011; Jian, Reference Jian2021). Unpacking the role of empathy in leadership ethics from a relational leadership perspective remains an important research agenda, as it can help individuals better interact with others and contribute to the theoretical development of relational leadership (Jian, Reference Jian2021). By adding an ethical and empathic angle, this article links and extends the relationality of leadership to the current realities of virtual and hybrid work environments. Pérezts et al. (Reference Pérezts, Russon and Painter2020) have advanced the field by incorporating a relational leadership perspective in demonstrating how it can be put into practice. Mirrored in the long-existing debate of whether ethics can be taught, the question remains how empathic relational leadership can be enhanced for leadership ethics application. Still, there is little integration of knowledge on relational leadership, ethics, and empathy, showing how to leverage the collaborative synergies of empathic relational leadership and ethics. By focusing on empathy in leadership development, especially through leadership conversations, we add to the discussion of whether and how ethics can be taught in leadership education. Furthermore, our article sheds light on current debates about how ethical decision-making takes place, as reflected in the discussion between Gilligan’s ethics of care and Kohlberg’s rational highest order of decision-making (Gilligan, Reference Gilligan1982). We position our study within the context of “ethics of care” by valuing emotions alongside a rationality approach, highlighting empathy for relationship building and interdependencies (Held Reference Held1990, Reference Held2006; Painter & Werhane, Reference Painter and Werhane2023).

Understanding how digital relational leadership processes play out is crucial to shedding light on the influence of one’s (un)ethical decision-making during virtual interactions. Through the video-based approach employed in this study, we provide insights into how empathic nonverbal and verbal responses, such as active listening, questioning, and emotion synchronization, influence the overall conversation between a leader and a participant, hence supporting ethical leadership development in the current hybrid work reality.

Previous studies have focused on individuals’ experiences or perceptions of their conversations, relying on participants’ memories of events and discussions (Larsen, Flesaker, & Stege, Reference Larsen, Flesaker and Stege2008). Consequently, we still do not fully understand how leaders practice empathy in leadership ethics during conversations with others. A contribution would help to enhance leadership development education on ethics with experiential learning approaches. In addition, research into the ways in which others respond to a leader’s (non)empathic cues that influence communication contributes to healthy, positive relational processes in organizations and societies (Jian, Reference Jian2021). The study had three overarching research questions:

-

1. How do leaders demonstrate empathy in leadership ethics during conversations with others?

-

2. How do participants’ responses to leaders impact empathic leadership conversations?

-

3. How do empathic conversations influence both leaders’ and participants’ attention and perceived satisfaction?

Taking an epistemologically objectivist position (Johnson & Duberley, Reference Johnson and Duberley2000), an in-depth analysis of video-recorded conversations was conducted using a facial emotion expression platform, along with a set of perception surveys. The qualitative analysis served as the primary method for examining and interpreting the data. In addition, a supplementary quantitative analysis was performed on the video data to provide additional insights. Based on our findings, this article presents a set of practical applications and recommendations for future research.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

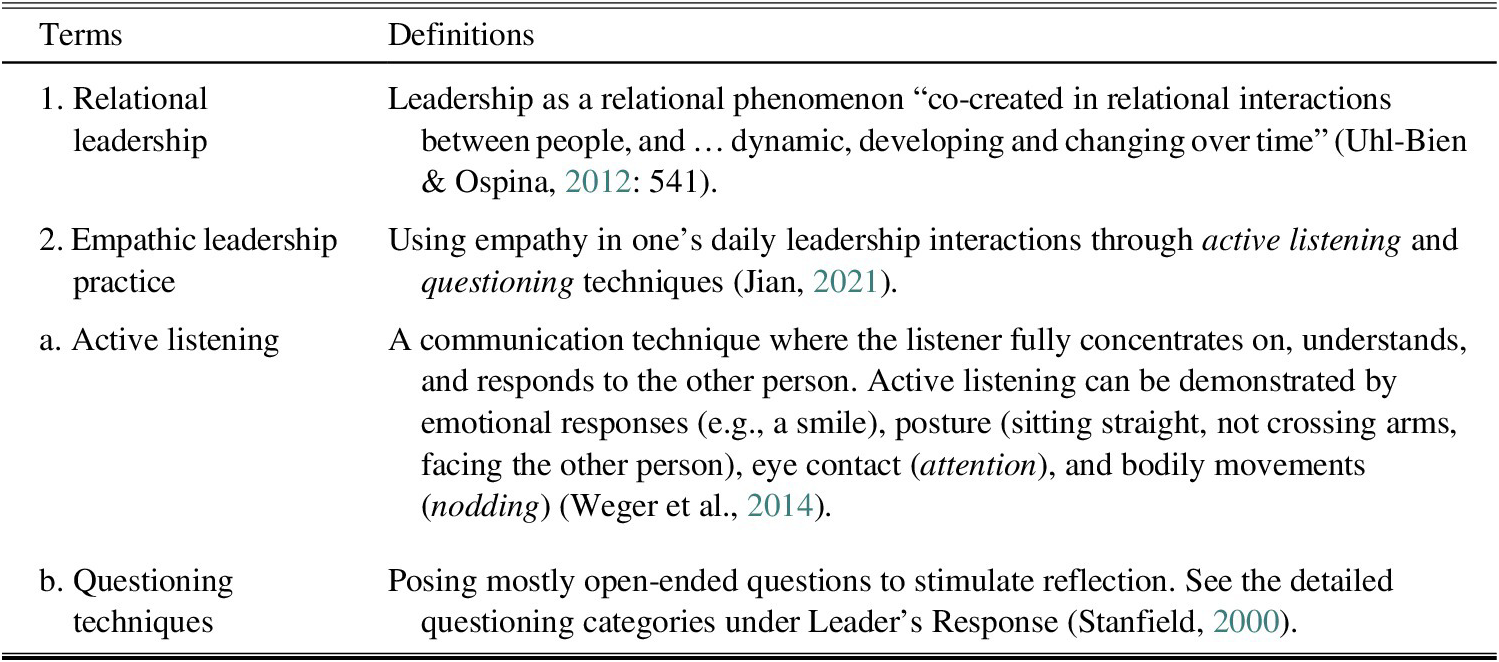

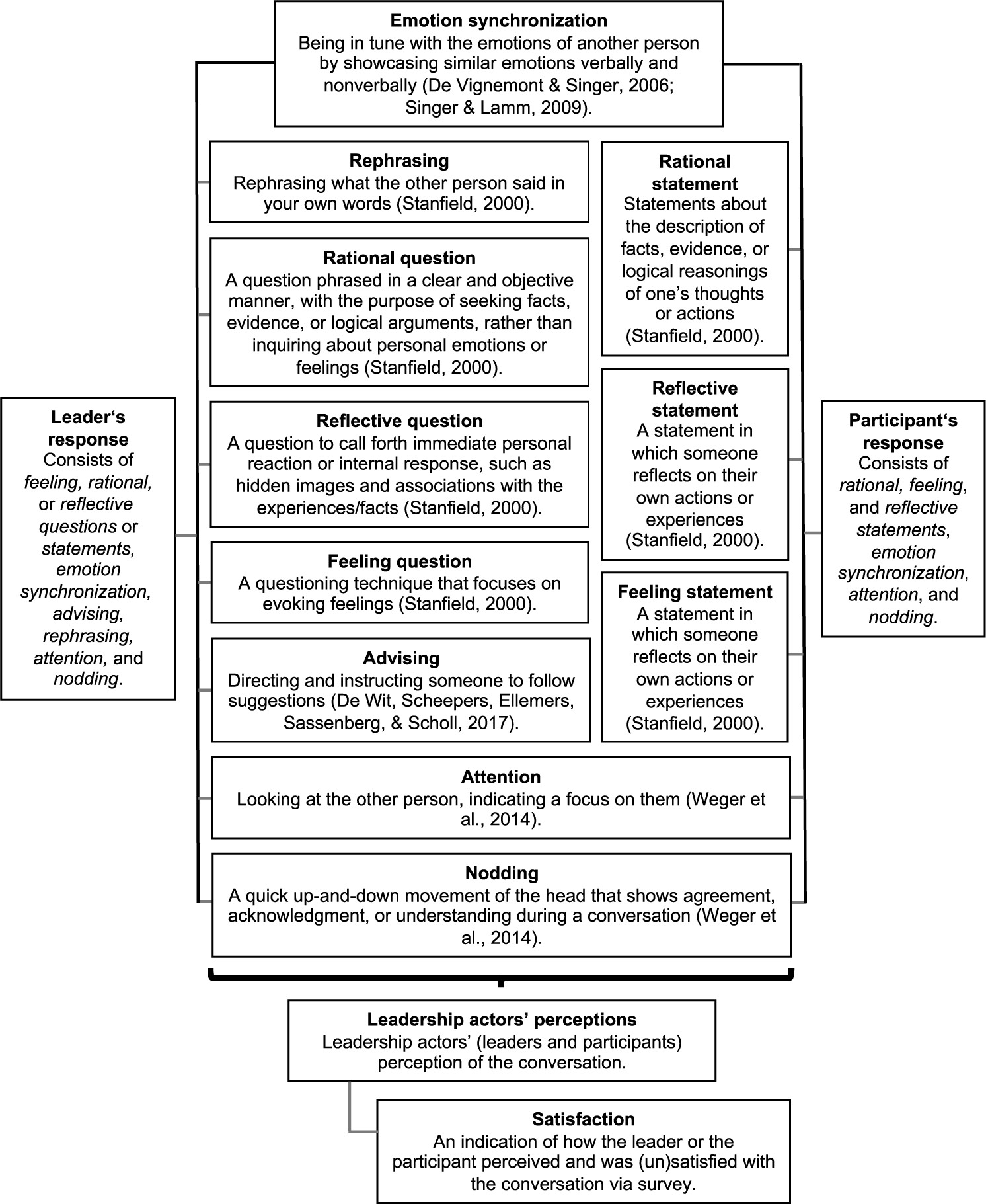

This study used a relational leadership framework with a focus on the role of empathy in leadership ethics. Scholars have argued that leadership ethics is manifested in everyday leadership conversations and has a deep connection to the concept of empathy (Jian, Reference Jian2021; Nicholson & Kurucz, Reference Nicholson and Kurucz2019). Table 1 provides a list of key terms in the theoretical framework and their definitions.

Table 1: Key Terms and Definitions

Leadership Ethics in Relational Leadership

Relational leadership remains a subject of scholarly debate, lacking universal descriptions and definitions (Painter & Werhane, Reference Painter and Werhane2023; Uhl-Bien & Ospina, Reference Uhl-Bien and Ospina2012). While acknowledging this spectrum—from a modernist entity perspective to a postmodernist constructionist viewpoint (Painter & Werhane, Reference Painter and Werhane2023; Pérezts et al., Reference Pérezts, Russon and Painter2020; Ospina & Uhl-Bien, Reference Ospina, Uhl-Bien, Uhl-Bien and Ospina2012)—this study primarily adopts an entitative perspective, which focuses on individual perceptions, attributes, and behaviors within leadership relationships, while still recognizing the importance of relational dynamics.

Despite the range of perspectives, common threads emerge, viewing leadership as a relational phenomenon “co-created in relational interactions between people, and that relational leadership is dynamic, developing and changing over time” (Uhl-Bien & Ospina, Reference Uhl-Bien and Ospina2012: 541). This relational view departs from the industrial era’s leadership perspective, which emphasized individual aspects such as leaders’ traits, personality, skills, styles, and behaviors (Uhl-Bien, Marion, & McKelvey, Reference Uhl-Bien, Marion and McKelvey2007). The traditional concept links to the idea of leadership as controlling, authoritative, and heroic, as exemplified in Carlyle’s (1841/Reference Carlyle1993) “Great Man” theory (Collinson, Smolović Jones, & Grint, Reference Collinson, Smolović Jones and Grint2018). This leadership paradigm emphasizes how leaders can influence others to achieve goals within formal hierarchical organizational structures (Uhl-Bien et al., Reference Uhl-Bien, Marion and McKelvey2007).

In today’s globalized era of rapid technological advancement, society has shifted from an industrial to a knowledge era, where knowledge is a core commodity, and its production is rapid. This shift necessitates viewing leadership not only as a position of authority but also as an emergent, interactive dynamic among individuals, illuminating interdependencies and relationships (Uhl-Bien & Arena, Reference Uhl-Bien and Arena2018; Uhl-Bien et al., Reference Uhl-Bien, Marion and McKelvey2007). In this context, the nuanced moral, emotional, and relational dimensions of individuals are emphasized (Jansson et al., Reference Jansson, Døving and Elstad2021), leading to scholarly arguments calling for the reconceptualization of leadership from a social and relational perspective (Jansson et al., Reference Jansson, Døving and Elstad2021).

Entity and Constructionist Perspectives of Relational Leadership

The relational perspective considers leadership “as a social influence process through which emergent coordination (i.e., evolving social order) and change (i.e., new values, attitudes, approaches, behaviors, ideologies, etc.) are constructed and produced” (Uhl-Bien, Reference Uhl-Bien, Painter and Werhane2023: 152). In other words, relational leadership emphasizes interdependencies and interactive dynamics where individuals influence each other. These relational dynamics challenge hierarchical models of leadership and illuminate complexity in systems in today’s global economy. This idea is discussed, for example, in the complexity leadership model (Uhl-Bien et al., Reference Uhl-Bien, Marion and McKelvey2007) and in systemic leadership (Painter-Morland & Deslandes, Reference Painter-Morland and Deslandes2017; Painter & Werhane, Reference Painter and Werhane2023).

The entity perspective on relational leadership emphasizes the importance of interpersonal relationships and focuses on “individual perceptions, cognition (e.g., self-concept), attributes, and behaviors (e.g., social influence, social exchange)” (Uhl-Bien, Reference Uhl-Bien, Painter and Werhane2023: 141). Leadership is seen as an “influence relationship” where individuals align to achieve mutual and organizational goals. These perspectives assume a realist ontology, viewing leadership as influenced by individually constituted realities, impacting organizational development (Dachler, Reference Dachler, Cranach, Doise and Mugny1992). Traditionally, the entitative approach focuses on manager-subordinate exchanges in established organizations (Uhl-Bien, Reference Uhl-Bien, Painter and Werhane2023). However, recent research calls for expanding these approaches beyond the manager-subordinate dynamic and recognizing that leadership can occur in any direction and is a relational property of a group (Graen, Reference Graen, Graen and Graen2006; Hogg, Reference Hogg2001; Uhl-Bien, Reference Uhl-Bien, Painter and Werhane2023; Uhl-Bien, Graen, & Scandura, Reference Uhl-Bien, Graen and Scandura2000).

In contrast, the constructionist approach emphasizes the importance of “relating” and relatedness like the processes and conditions of being in relation to others and the larger social system in constructing the meaning and reality of leadership. It views leadership as a socially constructed process, where leadership is fluid and co-created between leaders and members of the organization (Fairhurst, Reference Fairhurst2007; Uhl-Bien, Reference Uhl-Bien2006). This approach sees leadership as a dynamic, ongoing process where conversations and relationships are crucial for effective practice (Crevani, Reference Crevani, Carroll, Ford and Taylor2015), looking at the importance of the moral and emotional dimensions of leadership (Jansson et al., Reference Jansson, Døving and Elstad2021). This social constructionist view highlights the collective dimension of leadership (Nicholson & Kurucz, Reference Nicholson and Kurucz2019). Collaboration (Maak & Pless, Reference Maak and Pless2006), inclusivity (Carifio, Reference Carifio2010), and reciprocity (Cunliffe & Eriksen, Reference Cunliffe and Eriksen2011) are characteristics of this socially constructed process in leadership. Reciprocity indicates living in a way that promotes positive and mutually beneficial relationships with others, which goes beyond the exchange of resources (Nicholson & Kurucz, Reference Nicholson and Kurucz2019). With its collective stance, the relational view sees leadership as intersubjective, forming communicative actions and collective meaning-making (Cunliffe & Eriksen, Reference Cunliffe and Eriksen2011; Jian, Reference Jian2021; Uhl-Bien, Reference Uhl-Bien2006).

Ethics and Relational Leadership

Ethics is part and parcel of relational leadership, as Uhl-Bien (Reference Uhl-Bien2006) describes relational leadership as a social and ethical influence process among members of the organization. Leadership ethics in the relational view is generally referred to as leaders’ caring communication and relationships (Gilligan, Reference Gilligan1982; Mayeroff, Reference Mayeroff1971; Nicholson & Kurucz, Reference Nicholson and Kurucz2019; Nodding, Reference Nodding2013), generosity (Diprose, Reference Diprose2002), and responsibility for others (Grandy & Sliwa, Reference Grandy and Sliwa2017; Levinas, Reference Levinas1985; Rhodes & Badham, Reference Rhodes and Badham2018).

The ethics of care refers to the act of being attentive to one’s presence and its relation to the world and displaying empathic concern towards the well-being of others (Ciulla, Reference Ciulla2009). Ciulla (Reference Ciulla2009) draws upon Heidegger’s (Reference Heidegger1996: 3) concept of “care as attention to one’s own presence in the world,” emphasizing that care extends beyond the self and involves being attentive and engaged with others, often accompanied by a sense of responsibility. The ethics of care places significant importance on the interdependence of relationships (Tomkins & Simpson, Reference Tomkins and Simpson2015), which leads to a greater focus on fostering collaborative capabilities among members of the organization and highlights the significance of co-creating goals that facilitate the emergence of effective pathways for co-production (Nicholson & Kurucz, Reference Nicholson and Kurucz2019; Nodding, Reference Nodding2013). Gilligan’s (Reference Gilligan1982) perspective adds that traditional moral development theories, like Kohlberg’s, are biased towards abstract principles of justice, rights, and rules, often neglecting the relational and contextual dimensions. Gilligan (Reference Gilligan1982) argues that women often approach moral dilemmas with an “ethics of care,” focusing on maintaining relationships, resolving conflicts through communication, and being responsive to the needs of others. This approach underscores compassion and concern for relationships. The relational aspect, which focuses on connections with others, highlights the unavoidable role of emotion (Painter & Werhane, Reference Painter and Werhane2023). Held (Reference Held1990, Reference Held2006) argues that the ethics of care involves being responsible, valuing emotions alongside rationality, and recognizing the relational and interdependent nature of human beings.

Generosity indicates openness to others by recognizing their embodied existence (Diprose, Reference Diprose2002). Diprose (Reference Diprose2002) highlights the importance of acknowledging the embodied existence of others in her philosophy of corporeal generosity, which entails recognizing others as unique beings with their own perspectives and experiences. Our interactions and perceptions of others are shaped by embodiment, as their physical presence, including gestures, facial expressions, movements, and bodily sensations, mediates our experiences with them (Diprose, Reference Diprose2002; Jian, Reference Jian2021). By recognizing the embodied existence of others, empathy can be fostered, understanding can be cultivated, and mutual respect can be established, all of which are essential for ethical and social relations.

The ethics of responsibility emphasizes the importance of individuals taking responsibility for their actions and considering the impact of their decisions on others and their relationships (Levinas, Reference Levinas1985; Tomkins & Simpson, Reference Tomkins and Simpson2015). The ethics of responsibility enables leaders to value others (Rhodes & Badham, Reference Rhodes and Badham2018). It requires imagination and the ability to understand diverse perspectives, the willingness to exercise independent judgment, and the readiness to act and accept the consequences, even if personal sacrifice is involved (Ciulla, Knights, Mabey, & Tomkins, Reference Ciulla, Knights, Mabey and Tomkins2018; Gardiner, Reference Gardiner2018).

From this relational perspective on leadership ethics, positive relationships between leaders and others are stressed (Pless & Maak, Reference Pless and Maak2011). Leaders and members are “sensitive, attune and responsive to moments of difference, and feeling responsible for working with those differences” (Cunliffe & Eriksen, Reference Cunliffe and Eriksen2011: 1438). Therefore, the relational approach highlights that leadership is a socially constructed and ongoing dynamic process that emerges among individuals (Rhodes & Badham, Reference Rhodes and Badham2018).

Empathy and Leadership

In the theoretical construct of leadership ethics, empathy plays a pivotal role. In the following discussion, we explore the concept of empathy (Jian, Reference Jian2021). From an entitative perspective, scholars have examined empathy in terms of its affective, cognitive, and behavioral dimensions (Cuff, Brown, Taylor, & Howat, Reference Cuff, Brown, Taylor and Howat2016; Hall & Schwartz, Reference Hall and Schwartz2019; Meinecke & Kauffeld, Reference Meinecke and Kauffeld2019; Stosic, Fultz, Brown, & Bernieri, Reference Stosic, Fultz, Brown and Bernieri2022). Entitative leadership studies have mostly focused on the cognitive understanding of empathy, specifically exploring the link between individual empathy traits and leader outcomes (Uhl-Bien, Reference Uhl-Bien2006). For instance, a leader’s cognitive empathy refers to their capability to identify and understand the emotions of others (Bernstein & Davis, Reference Bernstein and Davis1982; Deutsch & Madle, Reference Deutsch and Madle1975; Hogan, Reference Hogan1969; Preckel, Kanske, & Singer, Reference Preckel, Kanske and Singer2018). In contrast, affective empathy arises from a leader sharing the emotions of another person (De Vignemont & Singer, Reference De Vignemont and Singer2006; Singer & Lamm, Reference Singer and Lamm2009) based on the ability to experience the emotions of others (Duan & Hill, Reference Duan and Hill1996). Lastly, behavioral empathy pertains to a leader’s ability to demonstrate compassion towards the needs, motivations, or viewpoints of others through actions (Decety & Jackson, Reference Decety and Jackson2004).

From a relational perspective (Carroll, Levy, & Richmond, Reference Carroll, Levy and Richmond2008; Crevani & Endrissat, Reference Crevani, Endrissat and Raelin2016; Crevani, Lindgren, & Packendorff, Reference Crevani, Lindgren and Packendorff2010; Raelin, Reference Raelin2016), empathic leadership practice involves dynamic interactions between actors. Empathy, as a complex process, plays a crucial role in effective communication. It allows leaders to understand and share the emotions of others, fostering emotional bonds and connections. In the context of empathic leadership, it is not solely the responsibility of the leader to demonstrate empathy; others also play a crucial role in responding to the leader’s empathic efforts.

The process of empathic leadership relies on active participation and mutual receptivity from both leaders and others, emphasizing the principles of relational leadership (Tzouramani, Reference Tzouramani, Marques and Dhiman2017). It is through communicative action that leaders and participants collaboratively create a space for empathic conversations, where emotions, thoughts, and experiences are shared and understood. This process helps build strong connections and enhances the overall quality of the leader-participant relationship.

Therefore, empathic meaning-making is an ongoing and dynamic phenomenon, arising from the continuous flow of interactions among leadership actors. We recognize the central role of discursive practices in the cultivation of empathy within leadership contexts (Barge & Fairhurst, Reference Barge and Fairhurst2008; Fairhurst, Reference Fairhurst2007, Reference Fairhurst2009; Jian, Reference Jian2021). In the next section, we delve into the practical aspects of empathic communication, specifically examining how it is enacted through the lens of leadership ethics. By exploring the intersection of empathy and ethical considerations, we aim to shed light on the ethical dimensions of empathic leadership and its significance in fostering positive organizational cultures.

Empathic Communication Practice with a Focus on Leadership Ethics

Individuals practice their leadership ethics by being open to and focusing on others through dialogic communication, as opposed to one-way communication, such as giving instructions or making suggestions when setting expectations (Nicholson & Kurucz, Reference Nicholson and Kurucz2019). Empathy serves as a vital element in such leadership dialogues (Cunliffe & Eriksen, Reference Cunliffe and Eriksen2011; Nicholson & Kurucz, Reference Nicholson and Kurucz2019; Orr & Bennett, Reference Orr and Bennett2017). Empathy can be nurtured through embodied conversational practices, where individuals actively engage and co-present with each other, striving to understand one another’s perspectives and emotional states. Embodied communication encompasses nonverbal cues, including body posture, facial expression, head movement, and eye contact (Jian, Reference Jian2021).

Arguing from a dialogue perspective, Jian (Reference Jian2021: 942) highlights that a series of communicative actions occur through “attention, question, invitation, and connection,” which help create a space for relating and connecting where empathy is mutually constructed through multiple empathic moments. The process is iterative, with the roles of empathizer and empathized often switching back and forth (Prior, Reference Prior2017). Empathic leadership practice can be broadly categorized into three components: active listening, questioning, and emotion synchronization (Jian, Reference Jian2021; Nakamura & Milner, Reference Nakamura and Milner2023; Prior, Reference Prior2017; Yokozuka, Ono, Inoue, Ogawa, & Miyake, Reference Yokozuka, Ono, Inoue, Ogawa and Miyake2018).

Active Listening

The ethics of generosity serves as a motivation for leaders to remain attentive and open to others, enabling them to deeply engage in interactions (Diprose, Reference Diprose2002). Leaders demonstrate their attention through embodied communicative acts, such as body posture, facial expressions, head movements (e.g., nodding), and eye contact, which convey their level of care for others (Jian, Reference Jian2021). This behavior can be categorized as active listening, as defined in Table 1 (Weger, Castle, Minei, & Robinson, Reference Weger, Castle, Minei and Robinson2014). Considering that leaders often occupy positions of power within hierarchical structures, their intentional communicative actions of attentiveness and openness are crucial for creating a positive relational space with others (Jian, Reference Jian2021).

By actively listening, leaders can make others feel understood (Weger et al., Reference Weger, Castle, Minei and Robinson2014). Active listening skills can be demonstrated through specific actions such as rephrasing what others have said, maintaining eye contact, and using appropriate gestures (Hawkins & Smith, Reference Hawkins and Smith2006). For example, a leader might say, “If I understand correctly, you are facing challenges in managing time with multiple assignments. Is that correct?”

In terms of appropriate postures and gestures, leaders can convey their focus on others by sitting up straight, maintaining eye contact, and nodding to demonstrate active listening (Weger et al., Reference Weger, Castle, Minei and Robinson2014). Integral to these active listening behaviors is the practice of silence, which creates a welcoming space that allows others ample time for reflection and response (Edmondson & Besieux, Reference Edmondson and Besieux2021; Škof, Reference Škof2016). These behaviors help build trust, creating an environment where individuals feel comfortable expressing their concerns and challenges and engaging in meaningful discussions to achieve common goals (McCarthy & Milner, Reference McCarthy and Milner2020).

Questioning

Leaders raise questions because they genuinely want to understand what others are going through and how they feel about the situations they are experiencing (Fuller, Kamans, van Vuuren, Wolfensberger, & de Jong, Reference Fuller, Kamans, van Vuuren, Wolfensberger and de Jong2021). The relational ethics of care can serve as a motivating factor for leaders to engage in empathic practices, where they play the role of an “empathizer (caring)” by showcasing care and concern, while also being open to being “empathized (cared for)” by others (Jian, Reference Jian2021; Mayeroff, Reference Mayeroff1971). Leaders invite others to co-construct a caring relationship, while recognizing that the other person caring also holds the role of being cared for (Nodding, Reference Nodding2013).

As an empathizer (caring), leaders can ask open-ended questions to foster meaningful conversations. For example, they might inquire, “How are you feeling about the situation?” (feeling) or “Please tell me more about how you made the decision given the circumstances” (rational). Effective conversations often involve a combination of questions that explore emotions (feeling) and reasoning (rational) (Stanfield, Reference Stanfield2000). Additionally, it can be helpful for leaders to pose reflective questions that assist the other person in making meaning of what was shared (Cranton, Reference Cranton2016; Marquardt, Reference Marquardt2011; O’Neil & Marsick, Reference O’Neil and Marsick2014). For instance, they might ask, “What did you learn from having this conversation?” In the role of a leader who is also being empathized with by others (cared for) (Nodding, Reference Nodding2013), it can be beneficial to share an associated dilemma or personal feeling related to the situation the other person is experiencing. This sharing can contribute to a collaborative process of meaning-making (Jian, Reference Jian2021). By actively listening and engaging in the reciprocal sharing of words and emotions, a connection space is created, leading to an intersubjective understanding.

Emotion Synchronization

Leaders invite others to share their emotional state so that they can emotionally connect with others by truly caring (De Vignemont & Singer, Reference De Vignemont and Singer2006; Singer & Lamm, Reference Singer and Lamm2009). Empathic leadership practice involves not only understanding the needs and wants of others but also sharing emotions because leaders are open, caring, and value others as they feel responsible for others (Rhodes & Badham, Reference Rhodes and Badham2018). When leaders display emotions with another person and their emotional state is synchronized, they can engage in conversations more effectively and naturally by asking questions and listening. For example, leaders may show feelings of sadness and say, “It must be very stressful,” which indicates feeling upset by hearing the other person’s “stressful” story. If leaders understand and care about another person and their emotional state (Bird & Viding, Reference Bird and Viding2014), they display empathy, which shows up in their facial expressions and synchronized emotions (De Vignemont & Singer, Reference De Vignemont and Singer2006; Singer & Lamm, Reference Singer and Lamm2009).

Advice as Power

Even though the concept of relational leadership emphasizes a mutually constructive discourse among organizational actors, in reality, hierarchical power dynamics exist in many organizations. In such environments, leadership often lacks the previously mentioned empathic communication, as leaders are the ones who judge, suggest, and shape one-way conversations. This does not allow intersubjective meaning-making to take place. In comparison to active listening, previous research has shown that when giving advice, people can feel less understood (Eskreis-Winkler, Fishbach, & Duckworth, Reference Eskreis-Winkler, Fishbach and Duckworth2018; Weger et al., Reference Weger, Castle, Minei and Robinson2014). Therefore, it is critical for leaders to practice empathic responses for healthy and ethical relationship-building and effective collaboration in the workplace. With leadership ethics (Diprose, Reference Diprose2002; Levinas, Reference Levinas1969, Reference Levinas1998; Nodding, Reference Nodding2013), leaders can engage in empathic conversational practices that help form healthy ethical relationships and create intersubjective meaning with others for effective collaboration in the workplace (Jian, Reference Jian2021).

METHODS

Adopting an epistemologically objectivist position (Johnson & Duberley, Reference Johnson and Duberley2000), a mixed-methods approach was employed to examine the conversations focusing on leadership actors’ empathic cues. A conversation analysis, as part of organizational discourse analysis methods, was conducted to examine relational views of leadership (Fairhurst & Uhl-Bien, Reference Fairhurst and Uhl-Bien2012). We used a facial expression platform to manually code a leader’s empathic cues (e.g., questioning, rephrasing) for qualitative analysis. Additionally, we analyzed the transcripts of the conversations qualitatively through discourse analysis. To support the conversation analysis, a set of perception surveys was included, comprising both open-ended and closed-ended questions. Furthermore, the coded data were quantified to test the relationships and compare with the qualitative analysis.

Sample and Background

The participants of this study were individuals who had attended a leadership workshop. They were asked to engage in five-minute online leadership conversations and to complete three short online surveys. They were familiar with each other as they had attended another leadership workshop together prior to this study. During the previous workshop, they received training on communication techniques, such as active listening and questioning, as part of empathic response and advising. They also reflected upon ethical challenges within the leadership context.

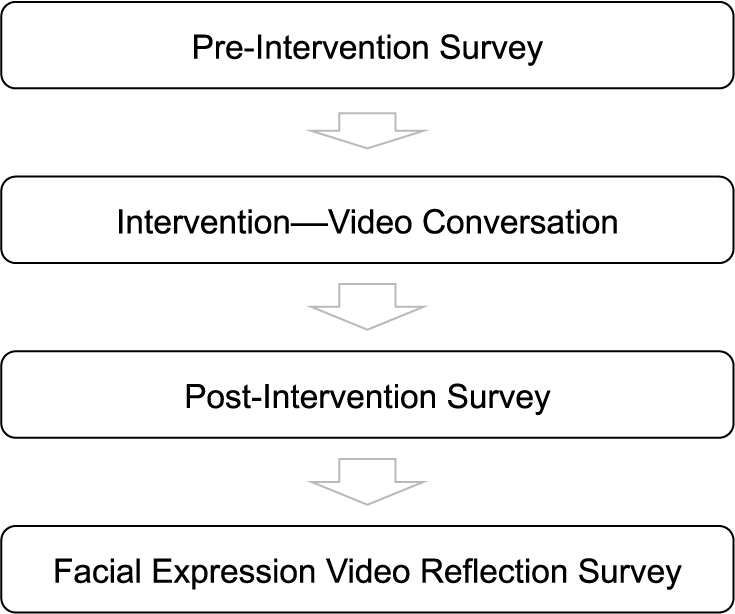

The surveys were conducted before and after video conversations, as well as after a debriefing reflection session, as illustrated in Figure 1. Participants were assigned to work in small groups, with roles rotated so that each person shared a leadership challenge with a new partner. The conversations were recorded on video, capturing both the leader and participant roles. Twenty-five people participated in the study, comprising 16 women and 9 men. They represented various industries, including manufacturing, shipping, energy/resources, consulting, and education, across Asia, Europe, and North America. On average, participants had 8.7 years of work experience and 2.8 years of management experience.

Figure 1: Timeline

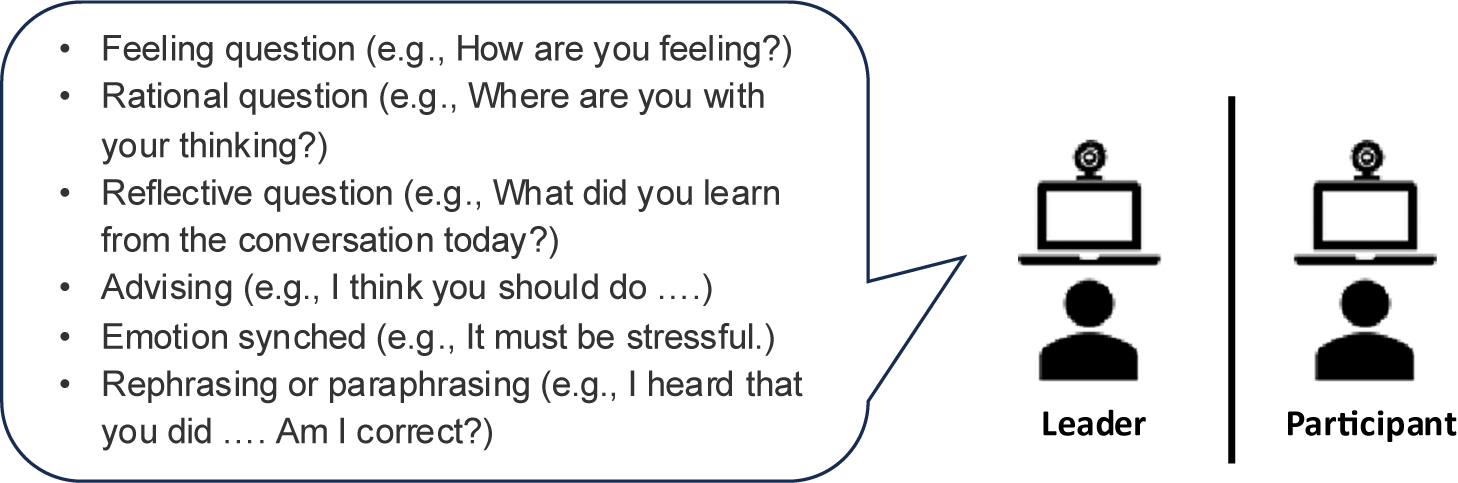

During the conversations, participants were asked to discuss their professional lives and/or career plans, while conversation leaders were instructed to implement three sets of responses or questions, as illustrated in Figure 2. To maintain authenticity, participants had the autonomy to decide when to use the different conversation modes, including feeling, rational, and reflective questions, as well as advising. The inclusion of advising allowed both leaders and participants to experience giving or receiving advice during the conversation.

Figure 2: Study Procedure: Online Video Conversations

To assess the participants’ perceptions of the conversations’ impact, the questionnaires included measures of satisfaction with the leadership conversation as well as open-ended questions to gather reflections on the discussion. Furthermore, to encourage participants’ reflexivity, a follow-up survey was administered after they watched the recorded video of the leadership conversation. The questionnaires were given to the subjects to compare conversation transcript analysis results for data validity, as depicted in Figure 1.

Data Collection and Procedure

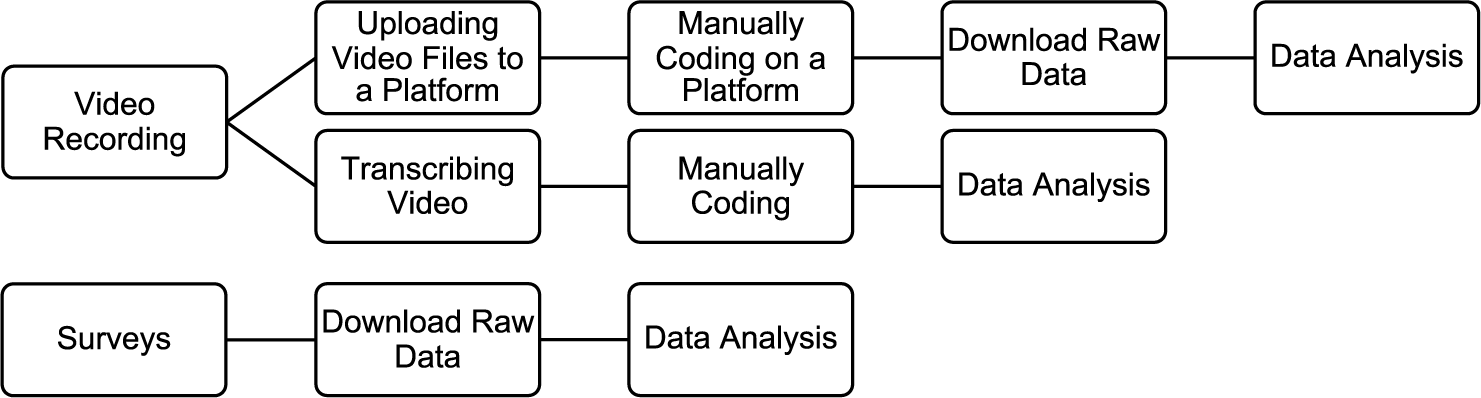

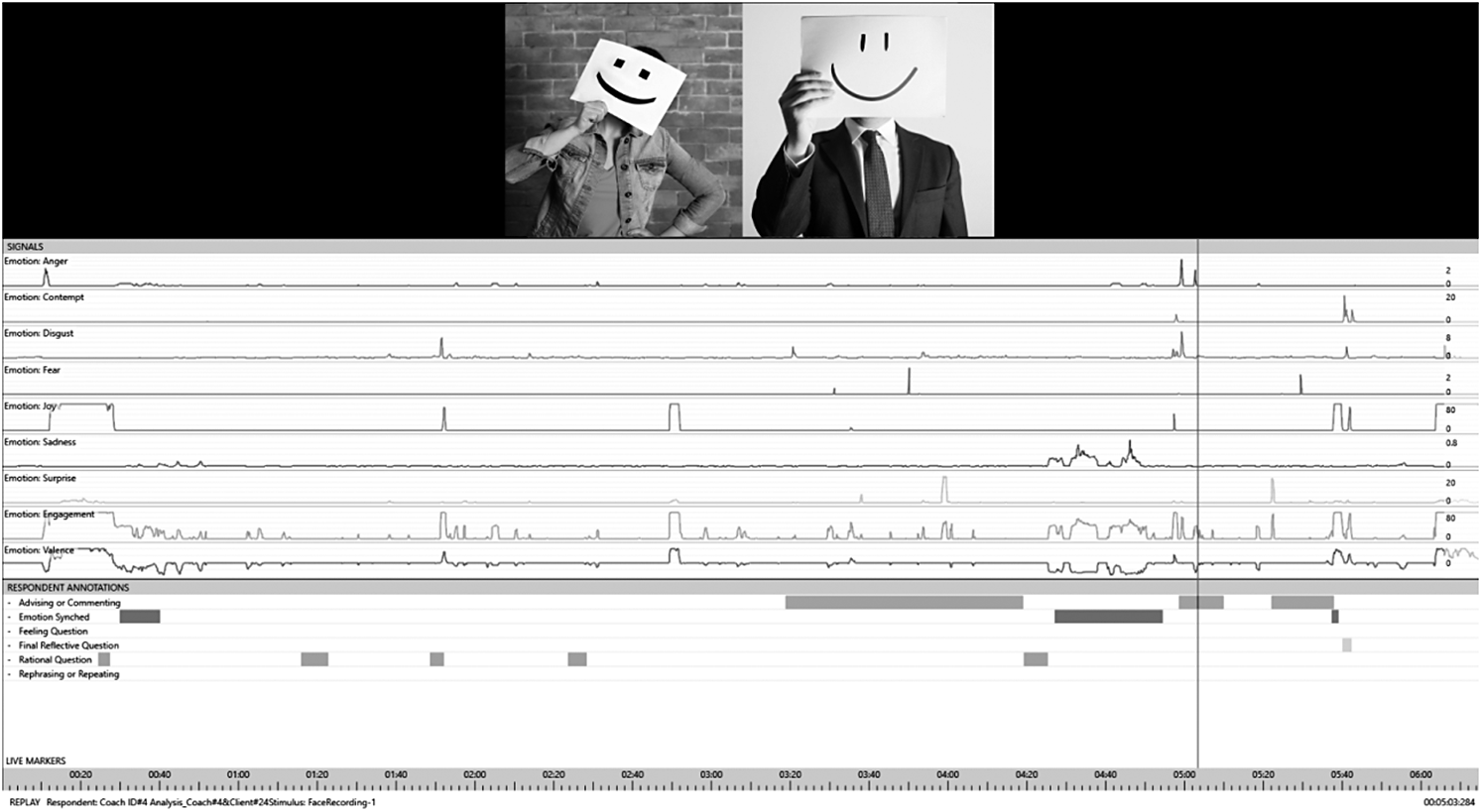

In this study, we employed both the Affectiva software integrated within the iMotions biometric research platform (Kulke, Feyerabend, & Schacht, Reference Kulke, Feyerabend and Schacht2020) and our own manual coding, along with surveys, to analyze the empathic conversations. The video (mp4) files were uploaded to the iMotions platform after obtaining them from the subjects for empathic conversation analysis, as shown in Figure 3. On the iMotions platform, we manually coded the six types of leader responses: three questioning categories (feeling, rational, and reflective), advising, rephrasing, and emotion synchronization. The specific instructions for the prompts given to the leaders, such as feeling, rational, and reflective questions and advising, were included among the six types of coding. Emotion synchronization and rephrasing were coded as we watched each video clip on the iMotions biometric research platform, as depicted in Figure 4. We watched the videos separately and discussed any discrepancies until we reached a consensus. (See the definition of the categories in Figure 5.)

Figure 3: Data Collection Process

Figure 4: Facial Emotional Expressions of a Leadership Conversation in iMotions Platform

Figure 5: Leadership Conversation Key Terms and Definitions

As part of active listening, we made notes of facial expressions, including eye movements and head orientation (e.g., nodding), for both the leaders and participants. These notes were automatically marked and displayed on the iMotions platform. The Affectiva software within the iMotions platform employs a frame-by-frame analysis to classify facial expressions and display corresponding emotions based on facial or behavioral landmarks such as eye movement, head orientation, and attention (Kulke et al., Reference Kulke, Feyerabend and Schacht2020). The reliability of emotion recognition by the Affectiva software has been confirmed in validation studies (Stöckli, Schulte-Mecklenbeck, Borer, & Samson, Reference Stöckli, Schulte-Mecklenbeck, Borer and Samson2018; Taggart, Dressler, Kumar, Khan, & Coppola, Reference Taggart, Dressler, Kumar, Khan and Coppola2016). The data were recorded in a format that captured facial expressions at intervals of 125 milliseconds (8 Hz).

Additionally, we transcribed the leadership conversations using Otter.ai software. These transcriptions were later subjected to qualitative discourse analysis using approaches described by Fairhurst and Uhl-Bien (Reference Fairhurst and Uhl-Bien2012), Mayring (Reference Mayring, Mey and Mruck2010), Fairhurst (Reference Fairhurst2007), and Saldaña (Reference Saldaña2009). To facilitate real-time teamwork, we employed a collaborative Google Excel spreadsheet (Ose, Reference Ose2016). We analyzed the data (Mayring, Reference Mayring, Mey and Mruck2010) utilizing both predefined coding schemes—a priori coding schemes (Fairhurst & Uhl-Bien, Reference Fairhurst and Uhl-Bien2012)—based on the conceptual framework of empathic communication in leadership ethics, such as feeling and rational responses (Fairhurst & Uhl-Bien, Reference Fairhurst and Uhl-Bien2012; Jian, Reference Jian2021), and emerging coding schemes that identified specific responses such as humor influencing empathic conversations. Throughout the coding process, we repeatedly referred back to the iMotions platform to watch videos while going through the transcripts, capturing the effect of nonverbal cues. The coders reached 95 percent consensus and resolved any discrepancies through discussion.

To aid the qualitative data analysis, we also conducted a quantitative data analysis. The raw data in .csv format was downloaded from the iMotions platform for basic statistical analysis. The data included frequencies (number of occurrences) of codes with time stamps and signal levels (strength of the signal). Signal level is a numerical value automatically calculated through the Affectiva software that indicates how strongly a variable is expressed (e.g., nodding). Multiple regression analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel, considering the research questions and using the frequencies of advising, emotion synchronization, rephrasing, feeling, rational, and reflective questions as variables. Additionally, regression analyses were conducted on attention (signal level) and satisfaction (score through the perception survey), considering variables such as the conversation partner’s nodding (signal level), attention (signal level), and emotion synchronization (frequency).

The surveys were administered both before and after the leadership conversations and during a follow-up session after participants reviewed the video with their facial expression analysis. The purpose of these surveys was to capture basic demographic information about the sample and assess the participants’ perceived satisfaction with the conversation and their overall conversation experiences. In order to interpret the patterns observed in the data, participants were asked to indicate their likelihood of recommending a leader-participant conversation similar to the one they had if a friend or business contact asked for their advice. This likelihood was measured on a 10-point scale, ranging from “very high probability” to “very low probability” (Keiningham, Cooil, Andreassen, & Aksoy, Reference Keiningham, Cooil, Andreassen and Aksoy2007). Additionally, a general comment section was provided where participants could share reflections on their level of satisfaction with the leadership conversation and provide key takeaways from reviewing the conversation video and analyzing their own facial expressions.

As a limitation, it is important to acknowledge the power imbalance between participants and the seminar lead. Although participants were provided with a consent form and had the option to withdraw from the research at any time, their participation in the seminar necessitated involvement in activities so they could put into practice what they learned and receive feedback. This is a common approach in leadership seminars. The seminar took measures to ensure privacy for the conversations by conducting the recordings outside of the face-to-face seminar time.

RESULTS

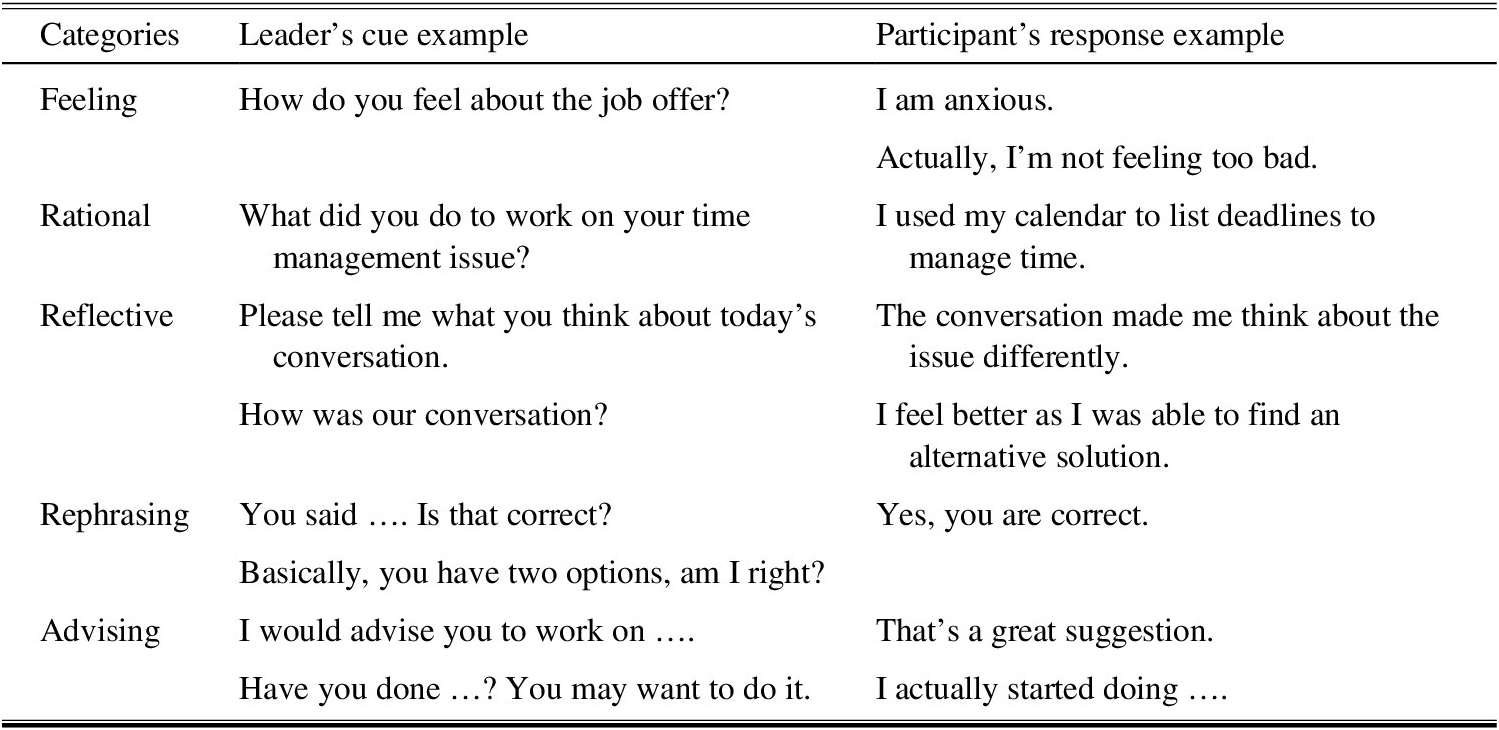

Overall, the qualitative data analysis revealed that the (un)empathic responses of leadership actors were deeply connected to the socially constructed conversation processes, which in turn influenced the perceived satisfaction of the conversations. Particularly, the combination of active listening cues such as nodding gesture and eye contact, feeling questions, and emotion synchronization played a crucial role in facilitating empathic conversations. Table 2 illustrates the patterns observed in each verbal cue (feeling, rational, and reflective questions, rephrasing, and advising) and provides examples of empathic responses.

Table 2: Patterns and Examples of Responses

Feeling Response and Emotion Synchronization Impact

The data analysis uncovered gendered patterns in leaders’ and participants’ feeling responses towards each other, which deeply influenced the overall empathic conversation. Although all leaders were instructed to ask feeling questions, most junior women leaders with three years of management experience or less, along with a few men leaders, consistently asked feeling questions throughout the conversation. They demonstrated active listening and synchronized their emotions with the participants. A common pattern observed was that these leaders initiated feeling questions from the beginning of the conversation, immediately after the participants shared a topic they wanted to discuss, and continued to ask feeling questions throughout the conversation. For example, a leader asked, “When you said you were not sure how you feel about the situation, are there any specific emotions when you are thinking about it?” The other example is, “How do you feel about your confidence working in your current [role at work]?”

Leaders who checked the participants’ emotional state through feeling questions also verbally indicated that they were emotionally relating to the other’s challenging situation—such as by saying, “I can definitely agree with you,” “I totally understand why you are having …,” “I am here with you on …,” or “I understand your dilemmas; it is stressful, I know,” with an active listening approach—and by nonverbal feedback, such as making eye contact with their facial expression showing sympathy (e.g., having a sad face if the participant’s situation was upsetting). For instance, a leader’s emotionally synchronized response combined with a feeling question is illustrated by the following conversation excerpt:

Participant: My concern is that I don’t know what I want to pursue…. I don’t know what I’m actually interested in life and how to pursue that.

Leader: …that’s very challenging. And how do you feel when you don’t know what to do about the situation?

Participant: It’s … at times, it feels annoying. But at times, I take it positively, because then I get to explore things. And I’m just not sticking to one thing, which I want to do. It allows me to have new experiences in different subjects. So, I take it both negatively and positively.

Some of the leaders embraced the participant’s emotion while they rephrased what their participants said to emotionally relate to them. Below is an example of a conversation that includes a rephrasing response in addition to a feeling question:

Leader: Okay, so, at this very moment, how are you feeling regarding this?

Participant: Actually, I’m not feeling too bad. I’m feeling more on the good side. I haven’t gotten anything concrete yet…

Leader: Okay, so it seems that you’re having … and that you’re feeling good with [it], basically. Right?

There were two patterns of the participants’ responses to the leaders’ feeling questions. In some cases, participants described their feelings to answer the leaders’ feeling questions, such as in the excerpts above. In other cases, largely men participants did not describe their feelings but responded rationally to leaders’ feeling questions. An example of the conversation is below:

Leader: How do you feel about that, having to pick up new skills [through a new assignment]?

Participant: I’d be able to pick it up….

Leader: …How did you feel about this conversation if it impacts you in any way?

Participant: I am looking back and actually analyzing the role deeper.

The conversation above did not involve the participant’s emotion, as he did not answer any of the feeling questions posed by the leader. Instead, he responded with his action-oriented rational thoughts on the matter he was discussing with the leader. The nature of conversations filled with rational thoughts prevented leaders from sharing emotional states and creating an emotional bond with the participants. In such conversations, leader-participant emotion synchronization rarely occurred.

When we examined the survey results, both leaders and participants reported feeling more satisfied with their conversations when leaders exhibited feeling and emotion synchronization, combined with active listening behaviors such as eye contact and nodding, while participants shared their emotions in response to the leaders’ questions. The participants noted that these conversations were more productive and helped them to reconsider situations, leading to the identification of different solutions. For example, one participant mentioned, “[The leader asked] the right questions to help … move [me] in directions that [I was not] thinking about and that could be [the] right ones.” Another participant stated, “[The conversation] can help you see the blind spot in your vision [and] provide a new angle of solution to your problems or interests.” The participants’ comments in the survey highlighted how leaders’ empathic active listening made them feel comfortable sharing their struggles and challenges. One person described, “She was a great listener, and I felt comfortable sharing my feelings with her.” Another person mentioned, “He was very empathic and involves himself in the problem with you and helps you find a conclusion.”

Furthermore, the follow-up survey indicated that some leaders described how they intentionally attempted to create an inviting conversational space. An individual reported, “I showed a lot of joy, engagement, and [positive] valence, because during the session I wanted to create a friendly, happy environment.” This finding suggests that leaders have the ability to intentionally shape a co-constructive space by synchronizing emotions and being purposeful in their feeling-focused cues, thus influencing the participant’s emotional state of mind during the conversation.

Rational Questions and Advising

Not all of the leaders asked a feeling question as instructed and/or demonstrated emotion synchronization. The conversations that lacked emotion synchronization tended to have more rational questions. These individuals were often men or women leaders with 10 years or more of management experience. Such leaders focused on asking what and how the participant did without inquiring about the participant’s emotional state of mind or sharing the same emotion. Rational questions steer conversations towards the logic and reasoning aspects of the thinking process. For example, when a participant discussed his dilemma in choosing between two new career options, a leader delved deeper by asking a series of rational questions, such as: “Is one of the two options of [new career opportunities] more attractive to you?”; “Tell me about your work experiences and what strengths fit in the management role?”; “Do you have anything that pushes you back from this position?”; “Regarding the other option, what drives you to think that this is also a good option?” However, the conversation primarily focused on facts and (future) actions, without involving emotional sharing moments between the leader and participant. The conversations that were filled with rational thoughts and had less synchronized emotional conversations resulted in lower satisfaction for both leaders and participants compared with the pairs who had the first pattern of feeling conversation.

Interestingly, as instructed, almost all leaders included advising components. However, men and women leaders with more than 10 years of management experience not only focused mostly on rational questions but also spent more time providing advice compared to others who asked feeling questions throughout the conversation. For example, a leader said, “You should ask your boss about your struggle at work.” In their reflections, none of the participants indicated how the leader’s advice impacted their conversations or how they felt about it.

Emotional Bonding Moments

Specific emotional bonding moments between leaders and participants emerged from the data analysis. These bonding moments were initiated when participants shared particular challenges. For instance, a participant humorously shared his struggle with being talkative. The participant’s humor made this initially serious leader smile and relax, setting a more relaxed tone for the conversation.

Leader: What would you think a weakness or some weaknesses that you might find during [collaborative work]?

Participant: My weakness could be like, I am a chatty person [smile], so I might overdo it and talk more than I need.

Leader: [Smile] Okay. And what do you think you could do to all get a bit better to change the situation so that you don’t feel that you’re being too chatty or …

Once a participant used a word “chatty” to humorously and casually describe his personality struggle, both the leader and participant smiled. From that point on, they relaxed more and used “chatty” as a keyword to continue their conversation. The use of a shared keyword throughout the conversation created a mutually understood emotional bond.

In addition, the data analysis results indicated that some conversations started with a greeting such as “hello,” “good to see you,” or “how are you?” by a leader. Participants responded with statements like “I am doing good. How are you?” Having a moment for greetings allowed for warm and smiling facial expressions from many leader-participant pairs. However, in some cases, this greeting space was not created. In these conversations, the leaders started off by asking what the participant wanted to talk about, skipping the greeting exchange and checking on how the participant was doing. The post-debrief session survey indicated that it was not always easy to create an emotional bonding moment at the beginning of the conversation. For instance, the individual said, “My attention and engagement dipped a bit in the beginning, and it took me a while to stay present.” The other person said, “I just got up then and was kind of unresponsive.” These individuals’ mental states interfered with their attentiveness due to tiredness and the need to adjust to the conversation.

At the end of the conversation, some pairs indicated a continued exchange. For instance, a leader said, “We can continue to work on this. Let’s talk more next time.” A participant agreed by saying, “Yes, that would be nice.” The beginning and ending of the conversations can also serve as moments for emotional bonding.

Cross-Cultural Dynamics

The study pointed towards an intricate interplay between empathy and cross-cultural understanding. Conversations appeared to be negatively impacted when, in the eyes of the participant, the leader failed to demonstrate empathy. This was particularly evident in interactions where participants from one cultural background communicated with leaders from another. Participants reported lower satisfaction with conversations when leaders exhibited less active listening, asked fewer feeling questions, and lacked emotion synchronization. For instance, in a conversation, a leader from outside of Europe did not use nodding gestures and maintained less eye contact by frequently looking away from the screen while a participant from Eastern Europe discussed her struggles with cultural identity and fitting into the work culture of Western Europe. During these sensitive cultural identity conversations, the participant expressed a sense of disconnection. In such conversations seemingly lacking empathy, the participants were less satisfied. One participant commented, “[The leader] seems not interested in my problems.” The participant also mentioned that “[the leader] did not focus on what I wanted to discuss.”

When leaders failed to relate to a participant’s cultural background or experiences, such as in the case of cultural identity described above, they tended to avoid asking feeling questions, rephrasing, and demonstrating emotion synchronization or actively listening. Instead, they continued to ask rational questions throughout the conversation. For example:

Participant: I’m under pressure and it makes me anxious … I think I cannot perform good on [work]. I’m super nervous.

Leader: So you want to talk about [work] or you want to talk about [the other work], or …?

Participant: I think I wanna discuss … how I’m anxious about [fitting] into … culture. I don’t know how to behave here.

Leader: Okay … Okay … So then you wanna talk about … cause you can behave however you want.

Participant: What do you mean?

As a result, the leader failed to establish shared emotional moments, and the participant perceived the conversation as lacking mutual constructiveness. In summary, while a general lack of empathy and active listening can hamper any conversation, this study highlights the added layer of complexity when navigating cross-cultural dynamics, especially around sensitive topics like cultural identity.

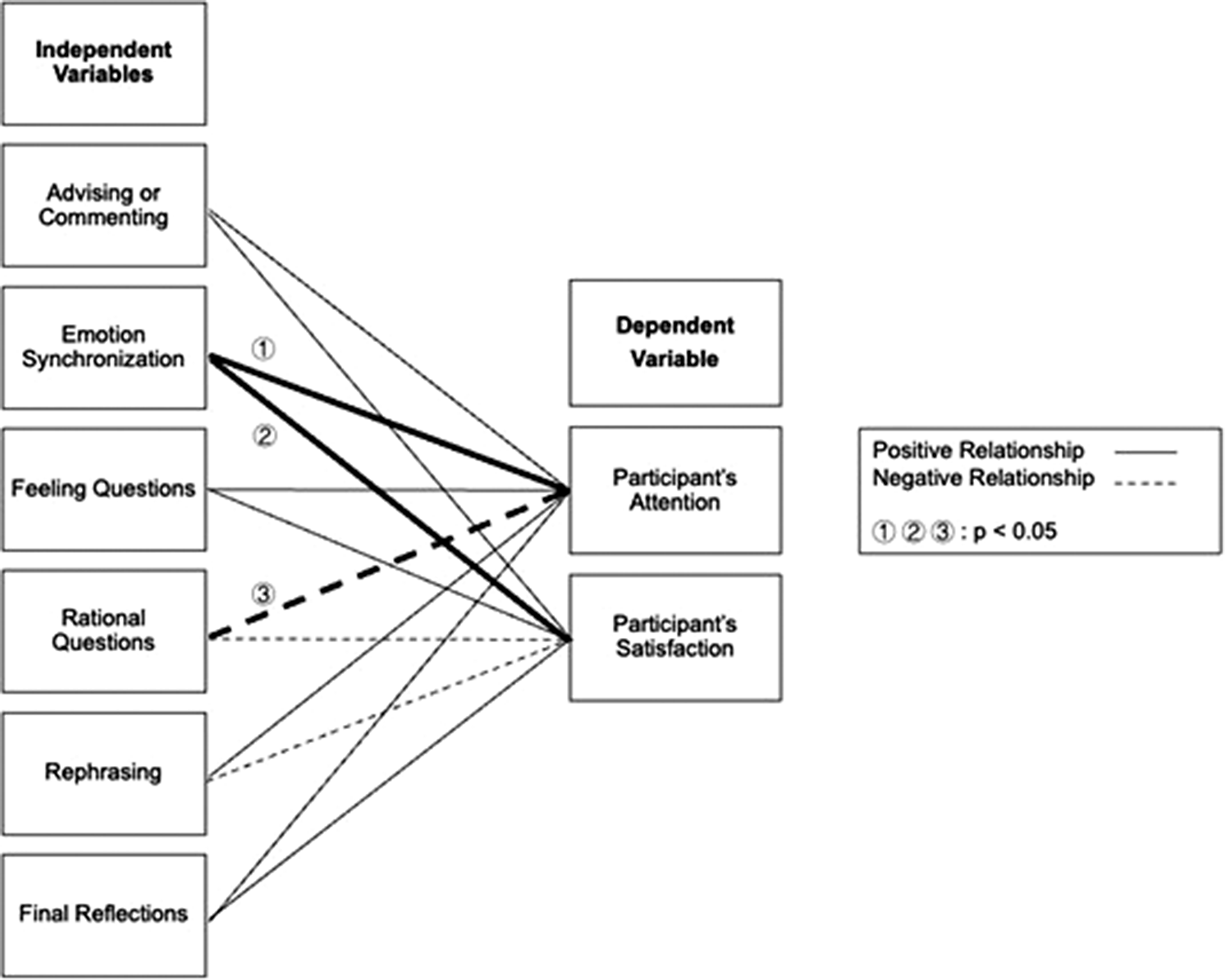

Empathic Cues That Impact Attention and Satisfaction

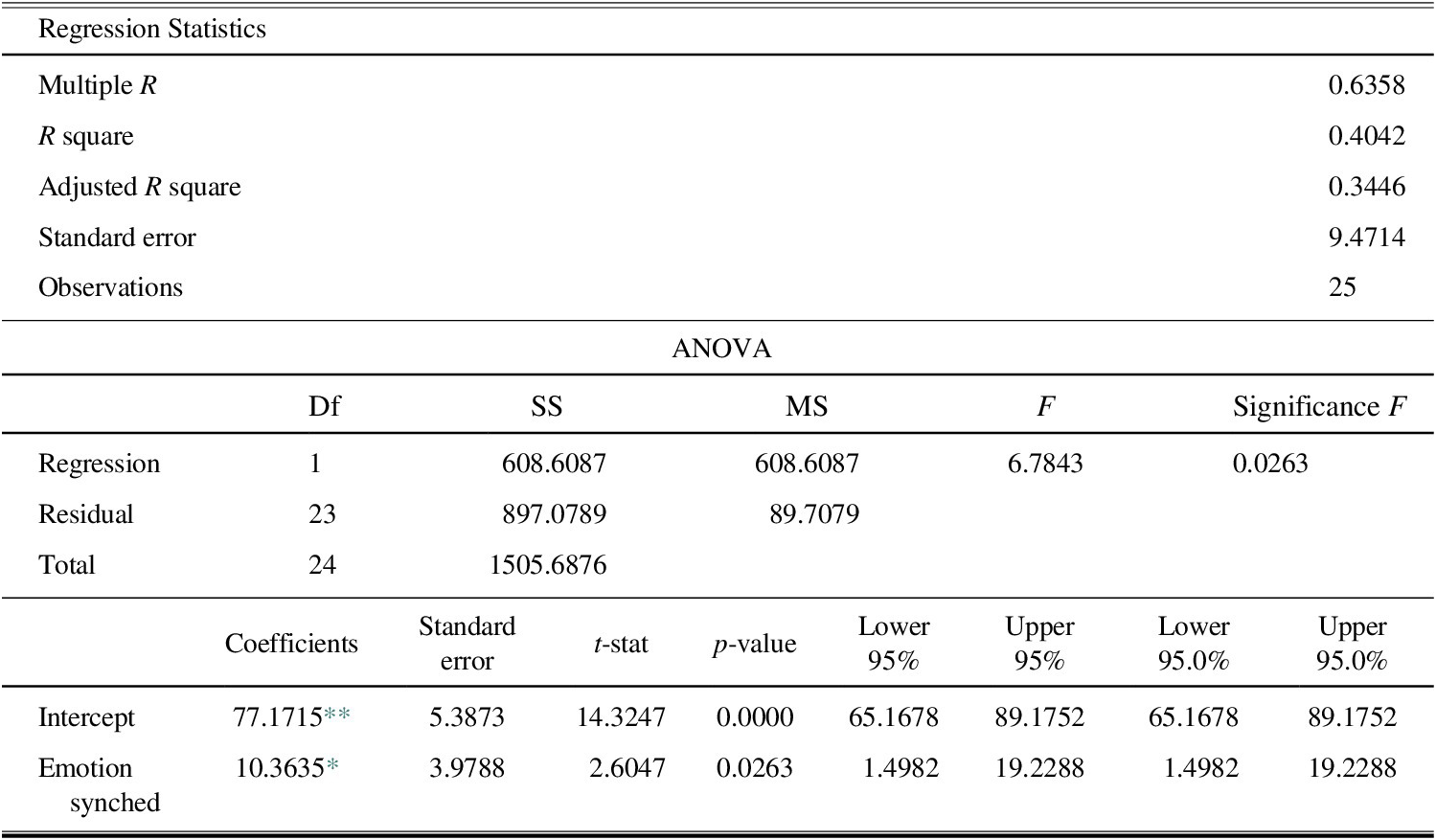

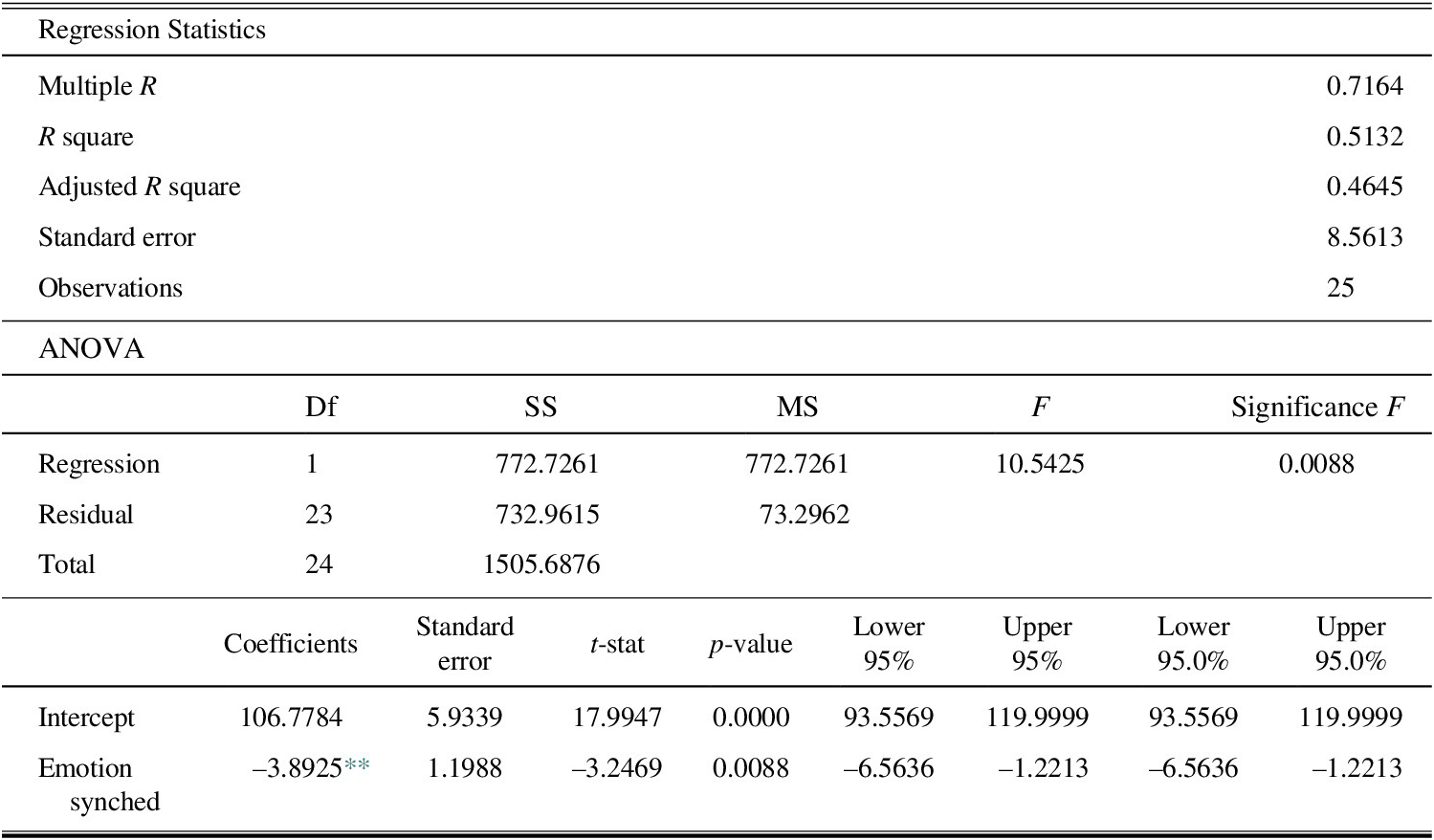

As a supplement to the qualitative data analysis, basic statistical analysis was conducted to validate the findings. The study tested attention and satisfaction of the participants as separate variables. Figure 6 displays the variables, with solid lines indicating positive relationships and dotted lines indicating negative relationships. The numbers 1, 2, and 3 next to the lines indicate significant relationships. Regression analysis was performed on the participant’s attention over the leader’s empathic responses (feeling, rational, reflective questions, emotion synchronization, advising, and rephrasing). As Table 3 shows, the quantity of emotion synchronization had a significantly positive impact on the participant’s attention (β = 10.3635, p = .0263) while, as shown in Table 4, the number of rational questions had a significantly negative impact on the participant’s attention (β = −3.8925, p = .0088) throughout the experiment. The results indicate that higher levels of emotion synchronization led to increased participant attention, while more rational questions asked by the leader resulted in decreased participant attention.

Figure 6: Regression Results: The Impact of Leaders’ Cues on Participants

Table 3: Regression Results: Participants’ Attention on Emotion Synchronization

* p < .05.

** p < .01.

Table 4: Regression Results: Participants’ Attention on Rational Questions

* p < .05.

** p < .01.

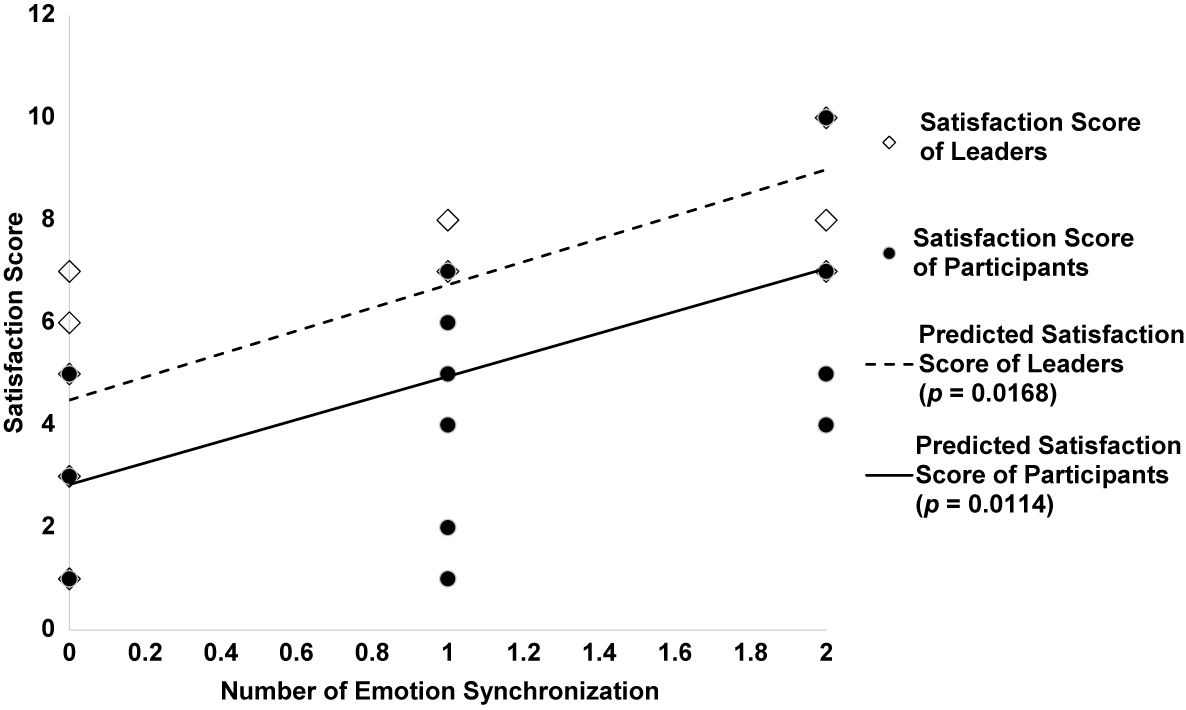

Furthermore, Figure 7 illustrates a positive relationship between the leader’s emotion synchronization and satisfaction (p = .0168), as well as a positive relationship between the participant’s emotion synchronization and satisfaction (p = .0114). Leaders’ satisfaction scores are marked in orange, while participants’ satisfaction scores are marked in green. When emotions were synchronized, participants’ satisfaction was more positively impacted compared to leaders’ satisfaction. When there was no emotion synchronization, the average satisfaction level of leaders was higher than that of participants.

Figure 7: Emotion Synchronization and Satisfaction Between Leaders and Participants

Emotion That Influences Leadership Conversation

Overall, the study findings shed light on the patterns of empathic responses exhibited by leadership actors during conversations and how these responses are perceived by both leaders and participants. The combination of active listening, feeling questioning, and emotion synchronization appeared to contribute to positive and comfortable conversations, particularly when participants openly shared their emotions in response to feeling questions. Notably, the presence of emotion synchronization during the conversation increased satisfaction levels for both leaders and participants. Another significant finding pertains to specific emotional bonding moments initiated by participants, such as introducing humor, which positively influenced leaders and facilitated emotion synchronization. However, an excessive focus on rational questions and advising limited opportunities for leaders to share emotions with participants, resulting in decreased attention and satisfaction. Cross-cultural dynamics also emerged as a potential barrier to empathic conversations. Furthermore, participants reported higher levels of satisfaction when their emotions were synchronized with those of their leaders. This underscores the importance of emotional alignment in fostering positive experiences during conversations.

DISCUSSION

The findings of the study revealed that both the leader’s and participant’s responses to each other influenced empathic conversations. When both the leader and participant synchronized emotions and openly shared emotions, they felt comfortable and had productive conversations. Despite providing instructions that required all leaders to include feeling, rational, and reflective questions, as well as advice during their conversations, certain patterns emerged in terms of the combinations of questions and advice, and participants’ responses to these cues from leaders. These patterns that influenced empathic conversation can be explained through the perspectives of relational leadership: big “D” Discourse and small “d” discourse (Fairhurst & Connaughton, Reference Fairhurst and Connaughton2014). Big “D” Discourse refers to the dominant narratives, ideologies, and cultural beliefs that shape and influence leadership practices within a specific context, representing the larger societal or organizational discourses that often hold power and influence over how leadership is understood and enacted (Fairhurst & Connaughton, Reference Fairhurst and Connaughton2014). Small “d” discourse refers to the localized, micro-level interactions and conversations that take place among individuals within a social group, focusing on communication patterns that construct meaning and influence leadership practices at an interpersonal level (Fairhurst & Connaughton, Reference Fairhurst and Connaughton2014).

The Role of Emotion in Leadership Conversation

The findings of the study revealed that many junior women leaders exhibited a higher frequency of feeling questions and engaged in emotion synchronization with their conversation partners during leadership conversations. This behavior can be understood through the lens of big “D” Discourse, which reflects sociocultural norms and expectations placed on women. Scholars have argued that communal stereotypes, such as the expectation for women to be caring (Pullen & Vachhani, Reference Pullen and Vachhani2021), may have influenced women leaders’ inclination to use feeling questions to understand participants’ emotional state (Bird & Viding, Reference Bird and Viding2014) and connect their emotions with their conversation partners through emotion synchronization (De Vignemont & Singer, Reference De Vignemont and Singer2006; Singer & Lamm, Reference Singer and Lamm2009). These gendered stereotypes shape the language, ideologies, and behaviors of leadership (Pullen & Vachhani, Reference Pullen and Vachhani2021).

The approach of using feeling questions and emotion synchronization, along with active listening, is deeply related to leadership ethics. Leaders demonstrated openness (Diprose, Reference Diprose2002; Liu, Reference Liu2017; Pullen & Rhodes, Reference Pullen and Rhodes2014) by seeking to understand participants’ experiences, showed concern for their well-being (Gilligan, Reference Gilligan1982; Mayeroff, Reference Mayeroff1971; Nodding, Reference Nodding2013), and felt a sense of responsibility to support them (Levinas, Reference Levinas1998; Grandy & Sliwa, Reference Grandy and Sliwa2017; Rhodes & Badham, Reference Rhodes and Badham2018). These behaviors of leadership ethics often appeared in women leaders’ conversations, which allowed the participants to feel comfortable and attentive to what the leader said or asked, generating a fruitful and satisfactory dialogue. As a result, the participants were able to think differently about the challenging situations they were talking about, and in some cases, find a solution to their challenges. Gilligan (Reference Gilligan1982) argues that women often handle moral dilemmas with an “ethics of care,” emphasizing relationships and responsiveness to others’ needs. The more prevalent manifestation of such behaviors in women’s leadership can be a disadvantage in contexts where male-embodied, stereotypically masculine leadership (Borgerson, Reference Borgerson2018) is perceived as successful, and is ultimately shaped by social norms elucidated by the big “D” Discourse (Fairhurst & Connaughton, Reference Fairhurst and Connaughton2014). However, ethics of care represents being responsible, valuing emotions alongside rationality, and recognizing the relational and interdependent nature of human beings (Held, Reference Held1990, Reference Held2006; Painter & Werhane, Reference Painter and Werhane2023). Our findings support Gilligan’s notion of ethics of care. Hence, we echo her emphasis on emotions and relationships, which is more than the rational “force” proposed by Kohlberg (Gilligan, Reference Gilligan1982). Our stance is aligned with Gilligan in postulating that for ethical decision-making, women may develop an empathy-based approach, but this is not about a lower order of moral development as shown in Kohlberg’s developmental stage theory (Kohlberg & Hersh, Reference Kohlberg and Hersh1977). We contribute to the ethical leadership literature by illuminating how empathy, specifically relating to feeling questions, enhances relational leadership. Therefore, it is crucial to underscore the profound impact of exemplifying leadership ethics in cultivating positive and healthy relationships.

As a mutually constructing process, the conversation is influenced by both the leader and participant, and the leader cannot dictate the process. The viewpoints of the big “D” Discourse can explain how male participants exhibit rational behavior due to social norms and expectations of agentic behavior (Pullen & Vachhani, Reference Pullen and Vachhani2021). Agentic behavior in leadership is associated with masculinity, such as assertiveness, confidence, and a focus on task-oriented goals (Mccabe & Knights, Reference Mccabe and Knights2016; Pullen & Vachhani, Reference Pullen and Vachhani2021). This leadership style is often characterized by a hierarchical and authoritative approach, where individuals take charge. However, as the results of the study show, not sharing emotions can make it difficult to foster emotional bonding opportunities even when leaders ask feeling questions to understand participants’ emotional states of mind. Individuals may not feel comfortable sharing their emotions due to concerns about being perceived as lacking confidence, assertiveness, and decisiveness. This type of behavior may be reinforced by working in an environment where hierarchical and authoritative masculine leadership is dominant. Therefore, in order to facilitate empathic leadership conversations, both the leader and participant should be open to hearing, acknowledging, and sharing their emotional states of mind to co-create a space for connection.

The Role of Power in Leadership Conversation

The heroic and authoritative image of leadership stereotypes remains deeply rooted in today’s society (Painter & Werhane, Reference Painter and Werhane2023). In our study, men and women leaders with over 10 years of management experience predominantly focused on rational questions and spent more time providing advice during leadership conversations. This behavior can also be explained through the sociocultural association of rational masculine leadership (Ciulla & Forsyth Reference Ciulla, Forsyth, Bryman, Collinson, Grint, Jackson and Uhl-Bien2011; Ciulla et al., Reference Ciulla, Knights, Mabey and Tomkins2018; Painter, Reference Painter, Painter and Werhane2023). However, such leadership practices often neglect relational feminine behaviors.

Men leaders often adhere to masculine leadership stereotypes, emphasizing qualities such as assertiveness, authority, and decisiveness. Consequently, they tend to utilize their power to give advice, positioning themselves in a higher role of suggesting actions to participants. Women leaders with extensive years of management experience may have adopted social norms associated with masculine leadership in order to achieve success, resulting in a preference for rational behavior over relational behavior. In their study, Mavin and Grandy (Reference Mavin and Grandy2016) discussed the embodied experience of elite women leaders and how their presentation as leaders is deeply influenced by sociocultural expectations regarding their appearance and presentation. Research has indicated that women leaders are often subjected to criticism and negative judgments regarding their display of empathy in ways that men are not (Brescoll, Reference Brescoll2016; Eagly, Reference Eagly2018). Studies have shown that when women exhibit behaviors that are traditionally associated with empathy, such as being emotionally sensitive, they can be perceived as lacking in leadership qualities (Brescoll, Reference Brescoll2016; Eagly, Reference Eagly2018). This phenomenon is often referred to as the “double bind” for women leaders (Smith, Brescoll, & Thomas, Reference Smith, Brescoll, Thomas, Connerley and Wu2016). Due to societal experiences, women leaders may feel compelled to prioritize rational questions and offer advice, aligning with a traditionally masculine leadership image in the workplace. These behaviors are historically valued in leadership positions (Pullen & Vachhani, Reference Pullen and Vachhani2021).

Moreover, the leaders’ persistent emphasis on rational questions made participants less attentive to the conversations. In some cases, leaders continued to ask only rational questions without including other types of questions (feeling and reflective) or rephrasing (active listening) throughout the conversations. Such conversations may stem from the perception of being judged or having limited space to explore their emotional states, which can lead to discomfort. Although feeling, reflective, and rephrasing questions are all a form of questioning, some leaders may still hold the belief that feelings or emotions should not be explored in the business context, where the “great man theory” of leadership is deeply rooted (Spector, Reference Spector2016). When employees perceive a lack of emotional connection with their leader, they may resort to defensive behavior, limiting help-seeking, and conceal vulnerability (Marquardt, Reference Marquardt2011). Through the lens of ethical behavior, participants may not view leaders as sharing their concerns and challenges (Jian, Reference Jian2021). Consequently, these types of leadership conversations, lacking emotion synchronization, demonstration of ethics of care, and responsibility for participants’ well-being (Jian, Reference Jian2021), result in lower overall satisfaction for both the leader and the participant. We argue that such experiential learning that lacks satisfaction can prevent the fostering of future ethical leadership conversations and thus miss out on mutual understanding, care, generosity, and responsibility (Ciulla, Reference Ciulla2009; Diprose, Reference Diprose2002; Gilligan, Reference Gilligan1982).

Leadership Conversation as a Co-creating Story

Some leadership conversations are co-constructed around particular triggering moments that create an emotionally bonded space with shared narrative and understanding. These types of conversations can be explained through small “d” discourse, where interpersonal conversations are held among leadership actors (Fairhurst & Connaughton, Reference Fairhurst and Connaughton2014). The conversations entail the exchange of ideas, beliefs, and information within a specific context or social setting. They involve the negotiation of meaning, the sharing of perspectives, and the construction of shared understanding between individuals during their conversations. Participants can initiate the conversation by inviting the leader to co-construct a space through humor, as exemplified in our results section. The humor can be playful and a sign of a trusting relationship between the leader and the participant. In this study, a leader responded favorably to the participant’s humorous talk with a warm laugh and built on the humor by referencing it throughout. As a result, the two engaged in a sequenced action, playing with language and co-producing a narrative that disarmed the leader who joined the participant to tackle challenges associated with the topic of the conversation. The narrative co-construction and its story performances are co-creations of leaders’ and participants’ conversations (Fairhurst & Uhl-Bien, Reference Fairhurst and Uhl-Bien2012). This approach, initiated by the participant and joined by the leader, exemplifies another instance of leadership’s ethical behavior toward others (Jian, Reference Jian2021).

The Impact of Cultural Dynamics on Leadership Conversations

Cultural dynamics can create barriers to establishing a constructive space when the leader and the participant come from different cultural backgrounds. While a lack of empathy or active listening can occur in any context, in our study, the nuances associated with cross-cultural interactions were evident. The cross-cultural example highlighted a lack of empathic responses from the leader, which had a negative impact on the participant’s discussion experiences. The leader may be distant from the issue that the participant is struggling with due to cultural differences, but we also acknowledge the potential influence of the research setting. The participants’ cognitive load was likely heightened by a dual focus on formulating their next question and grasping diverse cultural experiences. This might have limited their mental capacity to listen attentively.

Culture as a broader perspective can be viewed through the big “D” Discourse in regard to sociocultural expectations and norms. However, culture can also be discussed through a small “d” discourse perspective (Fairhurst & Connaughton, Reference Fairhurst and Connaughton2014), as the pairing in our study of leader and participant often entailed different cultural backgrounds, which affected interpersonal relationships surrounding their discussion on culture-related challenges, such as cultural identity. Such dynamics can put both the leader and the participant in out-group or in-group situations (Graen & Uhl-Bien, Reference Graen and Uhl-Bien1995). This distance tests leaders’ identities, making them inattentive and unable to embody active listening, resulting in appearing disengaged.

Interestingly, some people reported being too preoccupied with thinking about the next questions they wanted to ask, which was perceived as inattentive. This difficulty for the leader in asking the right questions to advance the conversation and support the participant ultimately led to a lack of care and responsibility for the participant’s well-being. In the previously described conversation surrounding the cultural identity issue, the leader may have found it difficult to relate to the situation the participant experienced due to unfamiliarity with the cultural settings, making it challenging to ask appropriate questions. This led to the leader’s missing the ethics of generosity due to being inattentive, such as frequently looking away from the screen, and lacking active listening gestures like nodding (Diprose, Reference Diprose2002). Although moments like this may not immediately damage the conversation, they can result in unproductive discussions, hindering the building of a collaborative relationship between leaders and participants (Maak & Pless, Reference Maak and Pless2006).

This type of conversation can occur when leaders engage with individuals who are not clearly connected to them, leading to a lack of trust (Nakamura et al., Reference Nakamura, Milner and Milner2022a). For example, in the case of a cross-functional group of organizational members, different groupings may be influenced by out-group versus in-group dynamics (Graen & Uhl-Bien, Reference Graen and Uhl-Bien1995). In such situations, leaders might find it challenging to demonstrate generosity, caring, and responsibility for the well-being of others because of cultural differences that prevent them from bonding or understanding each other well (Jian, Reference Jian2021).