1. Introduction

This article is a first attempt to investigate the adaptation of Japanese vowels in Truku, an Austronesian language spoken in Taiwan, a country colonized by Japan for fifty years (1895 ~ 1945) after the Sino-Japanese War. So far the only data to be documented (Palemeq Reference Palemeq2014a, Lee and Hsu Reference Lee and Hsu2018) have been recorded with orthographic transcriptions, which do not always reflect the real pronunciation.Footnote 1 This study is based on data of more than 250 loanwords, with more than 600 vowel tokens, collected during 2020 and 2021.

Loanword adaptation is a process that involves inherent competition between two conflicting forces, that of being as faithful to the source word as possible and that of conforming to the phonology of the recipient language. By default, loanwords would be conditioned by the same markedness constraints as the native words; but loanword adaptation is not always so straightforward and may involve complex interactions between mimicry of the source words and conformity with native phonology (Kenstowicz Reference Kenstowicz and Rhee2005, Kang Reference Kang, Oostendorp, Ewen, Hume and Rice2011). For instance, a loanword may adopt a divergent repair strategy that contradicts native phonology; a loanword may import a foreign feature into the language which violates native phonology; a loanword may even be altered when the relevant sound/structure is permitted in the native language (i.e., the retreat to the unmarked) (Kenstowicz Reference Kenstowicz and Rhee2005). These intricate interactions thus require loanword-specific faithfulness constraints which are ranked differently from native input-output (IO) faithfulness constraints (Yip Reference Yip2002, Reference Yip2006; Kenstowicz Reference Kenstowicz and Rhee2005; Hsieh et al. Reference Hsieh, Kenstowicz, Mou, Calabrese and Leo Wetzels2009; among others).

Vowel adaptation in Truku involves not only the default type of adaptation, in which identity preservation is sacrificed to satisfy some native language markedness constraints; other Truku markedness constraints are also found to be sacrificed to achieve better matching, resulting in importation, showing that Truku markedness constraints are of different strengths and are ranked differently with respect to loanword-sensitive faithfulness constraints (referred to as JO correspondence constraints). Truku loanword adaptation is also interesting in that a native markedness constraint not respected in loanword adaptation may become active when the loanwords undergo affixation, a derived environment effect. This derived environment effect shows that in addition to IO faithfulness and JO faithfulness constraints, it is essential to identify the correspondence between loanwords and affixed loanwords (i.e., OO correspondence). Finally, in addition to the competition between markedness and JO faithfulness constraints, the less-than-ideal matching is partly due to the lack of perceptual saliency in some vowels.

There have been three major proposals for approaches to loanword adaptation: the Phonological Approach (Paradis and LaCharité Reference Paradis and Lacharité1997, LaCharité and Paradis Reference Lacharité and Paradis2005), which considers loanword adaptation to be primarily based on a phoneme-to-phoneme mapping; the Perception Approach (Peperkamp and Dupoux Reference Peperkamp and Dupoux2003, Peperkamp Reference Peperkamp, Ettlinger, Fleischer and Park-Doob2005), which considers the input to loanword adaptation and processing to be purely perceptual; and the Perception-Phonological Approach (Kenstowicz Reference Kenstowicz2001/2004, Reference Kenstowicz2007; Yip Reference Yip2006; Y. Lin Reference Lin2008), which considers perception as the basis of the input-to-loanword adaptation that can be modified by the native language's phonology. This article will show that Truku loanword adaptation, which involves a mixture of perception and phonology, is best accounted for by the Perception-Phonological Approach.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows: section 2 briefly introduces the basic phonological background of Truku. Section 3 and section 4 respectively provide descriptive generalizations and analyses based on Optimality Theory (McCarthy and Prince Reference McCarthy and Prince1993, Prince and Smolensky Reference Prince and Smolensky1993/2004) of the adaptations of Japanese vowels shared by and new to Truku. Section 5 concludes the article.

2. Truku phonology

Truku has a total of 22 surface consonants, as shown in (1), among which [ʃ], [tʃ], and [dʒ] are the allophones of /s/, /t/, and /d/ palatalized before /i/ and /j/ (e.g., /sibus/ [ʃibus] ‘tree branch’, /tiju/ [tʃiju] ‘point with finger’, /ddima/ [də-dʒima] ‘bamboo’) (Tsukida Reference Tsukida, Adelaar and Himmelmann2005, Lee and Hsu Reference Lee and Hsu2018). Other than [tʃ] and [dʒ], Truku has another surface affricate [ts]. But [ts] has a limited distribution, occurring only in loanwords, interjections, and gerunds (Tsukida Reference Tsukida, Adelaar and Himmelmann2005).Footnote 2 In Truku, /ʔ/ is a phonemic consonant, as minimal pairs such as [ku] ‘1st person singular nominative bound pronoun’ and [ʔu] ‘topic marker’ are available (Tsukida Reference Tsukida2009, A. Lee Reference Lee2010).

(1) Truku surface consonants

(2) Truku surface vowels

There are seven surface vowels in Truku, as shown in (2), among which /i, u, a/, and /ə/ are phonemes. The phonemic status of /ə/ is evident by minimal pairs such as [pəħoŋ] ‘wood chip’ and [paħoŋ] ‘gallbladder’. Several things about /ə/ are worth noting. First, despite the fact that /ə/ is phonemic and can bear stress (e.g., [pə́ħoŋ] ‘wood chip’), it does not occur in word-final position (Tsukida Reference Tsukida, Adelaar and Himmelmann2005, A. Lee Reference Lee2010, Lee and Hsu Reference Lee and Hsu2018). This shows that a constraint prohibiting weak vowels from word-final position (e.g., *WeakV]w, (7a)) should be dominant in the language. It is not uncommon for word-final position to avoid vowels of weaker sonorities. For instance, in Faialense Portuguese, unstressed [ə] and [u] vowels tend to be dropped in prosodic word-final position. Crosswhite (Reference Crosswhite2000, Reference Crosswhite2001) argues that prosodic word-final position is prosodically weaker than other environments and, therefore, that vowels are less well licensed in the prosodically weak positions.

Second, the weak vowel is often left untranscribed in Truku studies; therefore, despite the fact that Truku does not allow tautosyllabic CC clusters (A. Lee Reference Lee2010, Lee and Hsu Reference Lee and Hsu2018), in previous Truku studies, words transcribed with CC clusters can often be found in pre-tonic position (e.g., pbáya ‘not skillful’).Footnote 3 But in reality, between the transcribed CC clusters is a weak vowel ([pəbája] ‘not skillful’), with two exceptions.Footnote 4 The first is when the first consonant of the transcribed CC cluster is a legitimate coda, which often comes from nasal affixes (A. Lee Reference Lee2010, Oiwa Reference Oiwa2017, Lee and Hsu Reference Lee and Hsu2018, H. Lin Reference Lin2021). Therefore, when the first member of a CC cluster is a nasal, the adjacent consonants are heterosyllabic and do not form tautosyllabic CC clusters (e.g., km-bubu [kəm.bu.bu] ‘get along with mother’). The second exception is when the second consonant is a glide (e.g., sgbyutus [sɨ.ɣə.bju.tus]) (A. Lee Reference Lee2010, Lee and Hsu Reference Lee and Hsu2018). In this case, the glide can be considered as being syllabified in the nuclear position and the syllable margin remains simple.Footnote 5 The above facts indicate that *Comp-M (7b), which prohibits complex syllable margins (i.e., complex onsets/codas), should be dominant and, crucially, outranks Dep-IO (7j) in the language, assuming the inter-consonantal vowel comes from insertion. The inserted vowel is always a central vowel [ə] (or [ɨ], see discussion below), which Rice (Reference Rice1995) and Rubach (Reference Rubach2007) argue is placeless. Place-Markedness, which favours placeless segments, should therefore be at work, but should rank below Ident-IO to limit its effect to inserted vowels that have no input correspondents.

Third, other than being a phonemic and an inserted vowel, schwa is the most common reduced vowel in Truku. Truku stress falls on the penultimate syllable and a vowel reduction process targets all pre-tonic vowels, changing them to weak vowels (e.g., /patas-an/ > [pətásan] ‘school’).Footnote 6 Pre-penultimate vowel reduction in Truku could be accounted for by proposing a positional faithfulness constraint such as Head(Foot)-Max-IO-Vpl (cf. Alderete Reference Alderete1995; H. Lin Reference Lin, Zeitoun, Teng and Wu2015, Reference Lin2020), enforcing segmental identity between the output in the foot head and its input counterpart. This would rank it over Place-Markedness, which favours central placeless vowels.

(3) Head(Foot)-Max-IO-Vpl >> Pl-Markedness

/patas-an/ ‘school’

pə(tásan) > pə(tə́sən)

For simplicity, here and in what follows vowel reduction in Truku is considered as the result of the domination of a markedness constraint prohibiting pre-tonic placeful vowels (*Pre-tonic-Vpl, (7c)) over the faithfulness constraint preserving IO vowel place (i.e., Max-IO-Vpl, (7k)).

Notice that while pre-tonic vowel reduction in Truku is active in suffixed words (e.g., /patas-an/ > [pətásan] ‘school’), it is less clear whether the same process is also active in the root form (despite the fact that just as with suffixed words, none of the pre-penultimate vowels in the root form are full, e.g., [bəɡíja] ‘hornet’). That is because unlike the schwa vowels in the suffixed forms, which have full vowel correspondents, pre-penultimate schwa vowels in the root form inherently lack full vowel correspondents from morphologically related forms. Therefore, root-internal schwa vowels in pre-penultimate syllables may have also come from epenthesis to repair CC clusters (e.g., /bɡija/ → [bəɡíja] ‘hornet’). This article makes no assumption as to whether the pre-penultimate schwas in the root form come from reduction or insertion. What is important to the present article is that, as with suffixed words, none of the pre-penultimate vowels in the root form are full, satisfying *Pre-tonic-Vpl, which is readily predicted by the constraint ranking proposed so far, as illustrated in (4).

(4) High ranked *Pre-tonic-Vpl and *Comp-M predicts pre-penultimate reduced vowels may come from vowel reduction or epenthesis

Fourth, previous studies of Truku consider that the schwa vowel, no matter whether it is underlying (as in the penultimate syllable), reduced (as in the pre-penultimate syllable), or inserted (to repair complex syllable margins), surfaces as [ə] without variation (e.g., phung [pə́ħoŋ] ‘wood chip’, ptasan [pətásan] (< patas-an /patas-an/) ‘school’, snaw [sə́naw] ‘man’, pspasan [pəsəpásan] (< p-sapah-an /p-sapah-an/) ‘for combing hair’); nonetheless, based on the sound files available in the online Truku dictionary (https://e-dictionary.ilrdf.org.tw/trv/search.htm) as well as data collected in the present study, the weak vowel after sibilants (i.e., coronal stridents such as [s], [ts]) actually surfaces with a higher tongue position (i.e., [ɨ], e.g., skalu [sɨkalu] ‘for combing hair’).Footnote 7 Such allophonic variation (i.e., [ɨ] after sibilants and [ə] elsewhere) is also observed in other Formosan languages (Austronesian languages spoken in Taiwan) such as Squliq Atayal (Huang Reference Huang2011, Reference Huang2018) and Tjalja'avus Paiwan (Chang Reference Chang2016). Lanakel, an Austronesian language of southern Vanuatu, also exhibits a similar allophonic variation in epenthesis, with [ɨ] occurring after coronals and [ə] elsewhere. The variation is accounted for in Kager (Reference Kager1999: 128) by ranking [cor-hi], which requires coronals to be followed by high vowels, over *[+ hi], which disprefers [ɨ]. Thus, the variation between [ɨ] and [ə] in Truku shows that a markedness constraint which requires sibilants and [ɨ] to co-occur (e.g., sib-ɨ, (7d)) should outrank the markedness constraint that prohibits [ɨ] (i.e., *ɨ, (7e)). The sib-ɨ constraint, on the other hand, should be outranked by Max-IO-Vpl, which is dominated by *Pre-tonic-Vpl, as not every post-sibilant vowel turns into [ɨ] (cf. (5e), (5f)); only underlying /ə/ and reduced or inserted vowels do (cf. (5d), (5j)). Notice that [ɨ] is a central vowel just as [ə] is, and therefore also placeless (following Rice Reference Rice1995, Rubach Reference Rubach2007), except that it has an additional feature of [+ hi]. According to Clements (Reference Clements1989), Odden (Reference Odden1991), Hume (Reference Hume1992, Reference Hume1996), and Clements and Hume (Reference Clements, Hume and Goldsmith1995), vocalic constrictions are defined in terms of two independent parameters: location (place) and degree (height), with vowel height independent of the vowel place node. Therefore, [ə] and [ɨ] can be both placeless, despite the fact that [ɨ] has an additional feature of [+ hi]. As [ɨ] derived from /ə/ violates the faithfulness constraint against feature addition (i.e., Dep-IO-[hi], (7l)), the change of /ə/ > [ɨ] to satisfy the sib-ɨ constraint suggests sib-ɨ crucially dominates Dep-IO-[hi] (cf. (5i) vs. (5j)).

(5) ||*Pre-tonic-Vpl >> sib-ɨ >> *ɨ|| predicts underlying /ə/ and reduced or inserted vowels surface as [ɨ] after sibilants

With respect to mid vowels [e, o], they are often the allophones of /i, u/ next to uvular /q/ and pharyngeal /ħ/ (e.g., qibu /qibu/ [qebu] ‘small mouse’, hubang /ħubaŋ/ [ħobaŋ] ‘fish scale’) (Tsukida Reference Tsukida, Adelaar and Himmelmann2005, A. Lee Reference Lee2010, Lee and Hsu Reference Lee and Hsu2018). Vowel lowering caused by adjacent postvelar sounds is not uncommon, being also observed in languages such as Arabic, Maltese, and Tiberian Hebrew (Hayward and Hayward Reference Hayward and Hayward1989, McCarthy Reference McCarthy and Keating1994) as well as in Formosan languages such as Atayal, Paiwan, Amis, and Bunun (Blust Reference Blust2009). Though seldom mentioned in previous Truku studies, the high back vowel [u] is also lowered before the velar nasal vowel (e.g., yayung /jajuŋ/ [jajoŋ] ‘river’) (cf. Hu Reference Hu2003). Mid vowels are cross-linguistically more marked than peripheral vowels (Crothers Reference Crothers and Greenberg1978, Disner Reference Disner and Maddieson1984, Beckman Reference Beckman1997). They are marked not only for being perceptually less distinctive (Gnanadesikan Reference Gnanadesikan1997, Flemming Reference Flemming2002) but also for violating more place markedness constraints, if mid vowels are assumed to combine the features of high and low vowels (Schane Reference Schane1984, Alderete et al. Reference Alderete, Beckman, Benua, Gnanadesikan, McCarthy and Urbanczyk1999). Thus, the allophonic variation of [i, u] ~ [e, o] in Truku native phonology shows that a context-sensitive markedness constraint prohibiting tautosyllabic adjacency of postvelar consonants and high vowels and a sequential markedness constraint prohibiting [uŋ] combinations (e.g., *PostVel-Vhi and *uŋ, (7g)) should crucially outrank the constraint prohibiting mid vowels (i.e., *e/o, (7f)) as well as the faithfulness constraint against the change of the [hi] feature (i.e., Ident-IO-[hi], (7n)). Please compare (6d) with (6c). The fact that postvelar-high vowel sequences as well as [uŋ] combinations are never repaired by changing the vowels to the placeless central vowels or the low [a] vowel shows that Max-IO-Vpl and Ident-IO-[lo] (7m), which require the preservation of the input specification for the feature [low], crucially dominates *e/o in the language (cf. (6d) vs. (6a) and (6b)).

But [e, o] are not always the allophones of [i, u]. There are words in the online dictionary that have [e, o] without a neighbouring /q/, /ħ/ or /ŋ/ (31 words containing [e] and 54 words containing [o]).Footnote 8 Therefore, the relation between [e, o] and [i, u] is not fully allophonic. According to A. Lee (Reference Lee2010), in addition to being the allophones of [i, u], [e, o] are also the allophones of [aj] and [aw], the former occurring in the word-medial position (e.g., [metaq] ‘thorn’, [doɾeq] ‘eye’) and the latter in the word-final position (e.g., [baɮaj] ‘very’, [baɾaw] ‘above’) (cf. also Tsukida Reference Tsukida2009 and Lee and Hsu Reference Lee and Hsu2018).Footnote 9 For instance, Lee and Hsu (Reference Lee and Hsu2018: 11) consider the underlying form of [metaq] ‘thorn’ to be /majtaq/. Nonetheless, segments that are in complementary distribution are not necessarily allophones, as with the English phonemes /h/ and /ŋ/, which are respectively banned from the word-final and the word-initial positions. Unfortunately, other than stating that [e, o] and [aj, aw] are in complementary distribution and providing a comparison of some lexical forms in the dialectally related Paran Seediq and Truku, which shows a correspondence between a Paran Seediq [o] and a Truku [aw] in the word-final position (e.g., Paran Seediq [ido] vs. Truku [idaw] ‘cooked rice’), no language internal evidence is provided in A. Lee (Reference Lee2010) to support the allophonic status between [e, o] and [aj, aw]. I examined words with [e, o] and [aj, aw] in the Truku online dictionary and found that when an [aj, aw] ending word is suffixed, [aj, aw] do not become [e] and [o] but become heterosyllabic [a.j] and [a.w] (e.g., [tə.maj] ‘enter’ > [tə.ma.jan] ‘place to enter’ *[tə.me.ʔan]; [ʃi.qaw] ‘stare’ > [sɨ.qa.wi], ‘stare-imperative’, *[sɨ.qo.ʔi]). Therefore, the [e, o] ~ [aj, aw] allophonic alternation does not seem to hold, at least in synchronic phonology. Assuming the [e, o] vowels without a neighbouring /q/, /ħ/, or /ŋ/ come from underlying /e, o/, Ident-IO-[hi] should crucially dominate *e/o to allow [e, o] vowels that are not adjacent o/q/, /ħ/, or /ŋ/ to surface faithfully (cf. (6e) vs. (6f)).

(6) ||*PostVel-Vhi, *uŋ >> Ident-IO-[hi] >> *e/o|| predicts the vowels in postvelar-high vowel sequences as well as [uŋ] are lowered; high ranked Max-IO-Vpl and Ident-IO-[lo] restrict the lowering to mid vowels.

Despite the fact that there is no synchronic evidence showing that [e, o] not adjacent to /q/, /ħ/, or /ŋ/ are derived from [aj, aw], it is true that [e] and [o] seldom occur in the word-final position. Of all the words containing [e] and [o] vowels without neighbouring /q/, /ħ/, or /ŋ/ in the online dictionary, only three root forms, gow [ɣo] ‘barking sound’, ney [ne] (meaning not provided in the dictionary), and mey [me] ‘serve one right’, and their affixed forms (i.e., tggow [tə.ɣə.ɣo] ‘barking sounds’; skney [sɨ.kə.ne] ‘used to saying “good”’, tnney [tə.nə.ne] ‘will say “good”’; skmey [sɨ.kə.me] ‘used to saying “serve one right”’), are found to have [e, o] in the word-final position. In other words, the distribution of [e, o] is highly limited word-finally. While the rare occurrence of [e, o] in word-final position may simply be a consequence of the fact that [e, o] are generally allophones of [i, u] (or may be allophones of [aj, aw]), it is more likely that this rarity is perceptually oriented. As mentioned, Truku is a language that disallows weak central vowels from occurring word-finally (cf. (7a) *WeakV]w) because word-final position is prosodically weak and unable to license weaker vowels (as also observed in other languages; Crosswhite Reference Crosswhite2000, Reference Crosswhite2001). Mid vowels are known to be perceptually less distinctive crosslinguistically (Gnanadesikan Reference Gnanadesikan1997, Flemming Reference Flemming2002). Therefore, the reason [e, o] are avoided word-finally could be attributed to the same reason word-final weak vowels are prevented in the language. It follows that the rare occurrence of [e, o] in the word-final position can be accounted for by a context-sensitive markedness constraint prohibiting word-final [e, o] (e.g., *e/o]w, (7 h)).

Finally, with respect to syllable structure, Truku syllables must begin with an onset (Tsukida Reference Tsukida, Adelaar and Himmelmann2005, Reference Tsukida2009). Although Truku words transcribed with an initial V or with VV clusters can often be seen in previous Truku studies (e.g., usa ‘go’, naa ‘should be’), according to Tsukida (Reference Tsukida2009), a glottal stop is always present and occupies the onset position in reality (e.g., usa [ʔusa] ‘go’, naa [naʔa] ‘should be’). This suggests that the markedness constraint of Onset (7i) is active in Truku and crucially dominates Dep-IO. Crosslinguistically, other than consonant insertion, vowel hiatus may also be repaired by other strategies such as gliding or coalescence. Whether these strategies are also used to resolve vowel hiatus in the native phonology is an understudied topic that is beyond the scope of this article. But I will show that gliding is the default strategy to repair vowel hiatus in loanword adaptation, while [ʔ]-insertion is only used to avoid generating marked structures.

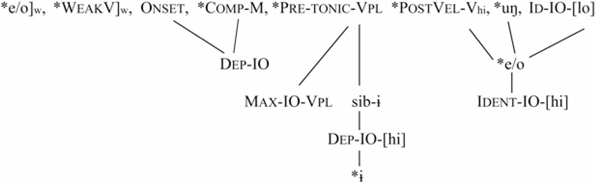

The constraints and the constraint rankings in Truku are summarized in (7) and (8), respectively:

(7) Markedness constraints active in Truku

a. *WeakV]w : No weak vowels in the word-final position.

b. *Comp-M: No complex syllable margins.

c. *Pre-tonic-Vpl: Pre-tonic vowels must be placeless.

d. sib-ɨ: A sibilant is followed by a [ɨ] vowel and a [ɨ] vowel is preceded by a sibilant.

e. *ɨ: No *ɨ vowels.

f. *e/o: No [e, o] vowels.

g. *PostVel-Vhi, *uŋ: No tautosyllabic adjacency of postvelar consonants and high vowels; No *uŋ combinations.

h. *e/o]w: No [e, o] vowels in the word-final position.

i. Onset: Syllables must begin with an onset.

Faithfulness constraints

j. Dep-IO: No insertion of segments.

k. Max-IO-Vpl: No deletion of the vowel place feature.

l. Dep-IO-[hi]: The [hi] feature in the output must have an input correspondent.

m. Ident-IO-[lo]: The specification for the feature [lo] in the input must be preserved in its output correspondent.

n. Ident-IO-[hi]: The specification for the feature [hi] in the input must be preserved in its output correspondent.

(8) Constraint rankings

The following two sections respectively provide descriptive generalizations and analyses of the adaptations of Japanese vowels shared by section 3 and new to section 4 Truku, based on data obtained through individual elicitation sessions with two Truku consultants in 2020 and 2021. Both consultants, retired pastors and native speakers of Truku with extensive linguistic knowledge, were interviewed separately. One of our consultants was born in 1952 and the other in 1955. Both of them know very little about Japanese. Before the interview, two wordlists were prepared, one for the researcher and the other for the consultants. The list for the researcher contains several common Japanese loanwords in Truku (Palemeq Reference Palemeq2014, Lee and Hsu Reference Lee and Hsu2018), together with the corresponding Chinese meanings as well as the Japanese source words in kana, in romanization, and in IPA (e.g., loanword in Truku: [minátu]; Chinese meaning: 港口 ‘port’; Japanese source word: みなとminato [minato]).Footnote 10 The list for the consultants contains only the Chinese meanings. During the interview, our consultants were asked if they knew any loanwords corresponding to the Chinese meanings. Due to the fact that Truku has loanwords originating from other languages such as Chinese and Taiwanese, words produced by our consultants that were very different from the Japanese source words and therefore could not possibly be Japanese loanwords were discarded (e.g., Japanese source word: [taɾai] taraiたらい; loanword in Truku: [bén.taŋ] ‘washbasin’).Footnote 11 If the produced word was close to the corresponding Japanese source word, the consultants were then asked to make a sentence for the word, to turn the simple loanword into an affixed word (e.g., [tatámi] ‘tatami’ > [tətəmí-ʔan] ‘tatami (locative focus)’), and to make another sentence for the affixed word. More than 250 loanwords, with more than 600 vowel tokens, were collected.Footnote 12

3. Vowels shared by Japanese and Truku

This section examines how Truku handles vowels in Japanese loanwords. Japanese has ten vowel phonemes, /i, ɯ, e, o, a, iː, ɯː, eː, oː, aː/. In addition to the ten phonemic vowels, the two Japanese high vowels [i, ɯ], which are the most frequent target of the highly salient rule of devoicing in Japanese, have the two allophones [i̥] and [ɯ̥] between voiceless consonants (e.g., /sitʃoː/ [ʃí̥tʃoː] ‘mayor’) or after a voiceless consonant in the word-final position (e.g., /daiɡakɯ/ [daiɡákɯ̥] ‘university’) (Han Reference Han1962, McCawley Reference McCawley1968, Tsujimura Reference Tsujimura2007, Fujimoto Reference Fujimoto and Kubozono2015). Some scholars note that devoicing can also occur with vowels other than high vowels (Vance Reference Vance2008, Labrune Reference Labrune2012), but devoicing of non-high vowels is less common and non-systematic (Labrune Reference Labrune2012, Fujimoto Reference Fujimoto and Kubozono2015). This paper will concentrate on how the 12 Japanese surface vowels [i, ɯ, e, o, a, iː, ɯː, eː, oː, aː, i̥, ɯ̥] are handled when entering Truku. The vowels that appear in both Japanese and Truku are the high vowel [i], the low vowel [a], and the mid vowels [e, o].Footnote 13

3.1 The peripheral vowels: [i], [a]

As expected, the vast majority of [i] and [a] enter Truku without change, as summarized in (9), with examples given in (10)–(15). Following Yip (Reference Yip1993, Reference Yip2002, Reference Yip2006), Steriade (Reference Steriade, Hume and Johnson2001), Kang (Reference Kang2003), Miao (Reference Miao2005), and Kenstowicz (Reference Kenstowicz2007), among others, this paper assumes the input-to-loanword adaptation is the surface form of the source language. Section 4.3. will address why the perception of the Japanese sounds is the input-to-word adaptation rather than the Japanese phonemes.

(9)

(10) i > i (88/94 = 93.6%)

(11) i > others (4/94 = 4.3%) (i > e, i > j)

(12) i > variation (2/94 = 2.1%) (i > i ~ j)

(13) a > a (155/159 = 97.5%)

(14) a > others (4/159 = 1.9%) (a > i, a > u, a > ə)

(15) a > variation (1/159 = 0.6%) (a > ∅ ~ a)

There are only a few cases in which [i] and [a] are adjusted to other vowels, but some are actually governed by Truku phonology. For example, the two loanwords in our database with the adjustment of [i] to [e] (cf. (11 a–b)) both have the target vowel adjacent to [ħ]. As Truku disallows a high vowel to be adjacent to [ħ], the adaptation of [i] to [e], even if the Japanese [i] has a direct counterpart in Truku, ensures that the output form follows the phonotactic constraint *PostVel-Vhi in Truku. The adaptation of [i] to [e] next to [ħ] shows that loanword adaptation is not just a matter of faithfully preserving a foreign output and that native phonology may play a more important role in the shaping of a non-native word than faithful mimicry of the source word, accounted for by the domination of the native markedness constraint *PostVel-Vhi over the loanword-sensitive constraint, Ident-JO-[hi], as illustrated in (16). (The Japanese [ç] is always adapted as [ħ] in Truku.)

(16) ||*PostVel-Vhi >> Ident-JO-[hi]|| predicts the adaptation of [i] to [e] next to [ħ]

The two loanwords in our database that unexpectedly involve the adjustment of [i] to [j], as shown in (11c) and (11d), are also motivated by native phonology. As the [i] vowel of the source words in both examples are adjacent to another vowel, the gliding of the high vowel helps prevent an onsetless syllable, respecting the Onset constraint of Truku.

(17) ||Onset >> Dep-JO >> Ident-JO-[syll]|| predicts gliding to repair vowel coalescence

There are two situations in which gliding does not occur. One is when gliding would result in a non-final offglide (i.e., *VGC; e.g. [koːmɯiɴ] > [ku.mu.ʔiŋ], *[ku.mujŋ] ‘civil servant’). As a VGC sequence violates *Comp-M, the absence of gliding before a tautosyllabic consonant can be predicted by the domination of *Comp-M over Dep-JO. The second situation in which gliding does not occur is across morpheme boundary (e.g., [tatami-an] > [tətəmi-ʔan], *[tətəmjan] ‘tatami (LF)’). This shows that a constraint requiring the right edge of a morpheme to coincide with the right edge of a syllable (e.g., Align-Morpheme-R) is at work and prevents syllables from containing segmental materials belonging to different morphemes.Footnote 14 The way Japanese vowel clusters are adjusted when entering Truku shows that gliding is the default repair strategy. But as the default native repair strategy of VV clusters requires further study, this paper cannot offer a comparison. Excluding the above predictable adjustment, the Japanese [i] vowels are preserved as [i] in 97.8% of cases.

In the cases where the low vowel [a] is mapped to other vowels, there is no clear pattern except that the adaptation of [a] to [ə] (i.e., (14c)) may be due to pre-tonic vowel reduction in Truku, which is generally not respected in unaffixed loanwords. This will be addressed in more detail in section 4.4.

3.2 The mid vowels: [e], [o]

Unlike the majority of high vowel [i] and low vowel [a], which enter Truku without changes, the mid vowels [e] and [o] are often mapped to the higher vowels [i] and [u] rather than being faithfully preserved as [e] and [o], even though [e] and [o] vowels also exist in Truku. The adaptations of [e, o] are summarized in (18), with examples given in (19)–(25).

(18)

(19) e > i (32/51 = 62.7%)

(20) e > e (11/51 = 21.2%)

(21) e > variation (8/51 = 15.6%) (e > i ~ e)

(22) o > u (62/85 = 72.9%)

(23) o > o (13/85 = 17.4%)

(24) o > others (2/85 = 2.4%) (o > i, o > ə)

(25) o > variation (7/85 = 15.3%) (o > u ~ o)

The fact that even though Truku has [e, o], Japanese [e, o] are more likely to be adjusted to [i, u] in Japanese loanwords indicates that the native markedness constraint *e/o should dominate the loanword-sensitive faithfulness constraint, Ident-JO-[hi], as shown in (26).Footnote 16

(26) ||*e/o >> Ident-JO-[hi]|| predicts the adaptation of [e, o] > [i, u]

In the majority of cases, it is unclear when [e, o] are mapped to the high vowels [i, u] and when they are faithfully preserved as [e, o]. Although in native phonology [e] and [o] are predominantly allophones of [i] and [u], occurring adjacent to postvelar consonants or velar nasal coda, in loanwords their distributions are not constrained by adjacent consonants. For instance, the /te, de, ɣe/ combinations in the source words can be adjusted as [ti, di, ɣi] (e.g., (19a–c)) or surface as [te, de, ɣe] (e.g., (20a–c)) in Truku, and /so, ʃo/ combinations in the source words can be mapped to Truku [su, ʃju] (e.g., (22a–b)) or [so, ʃjo] (e.g., (23a–b)). Pitch in the source word has no significant effect on the adaptation of [e, o] either, since [e, o] can enter Truku as high or mid vowels whether they are accented in the source word or not (cf. [bókɯ̥ʃi̥] > [búkuʃi] ‘priest’ and [sóba] > [sóba] ‘buckwheat’). Therefore, the variation is not phonologically conditioned.

There have been several proposals to account for variation within the OT framework (see e.g., Kager Reference Kager1999, Anttila Reference Anttila2002, and Coetzee and Pater Reference Coetzee, Pater, Goldsmith, Riggle and Yu2011). For instance, Partially Ordered Theory (Anttila Reference Anttila, Hinskens, van Hout and Wetzels1997, Anttila and Kim Reference Anttila and Kim2017) assumes that a grammar can have partial order (or incomplete ranking) of constraints and allow some constraints to be unspecified for ranking (or freely ranked), with the multiple rankings accounting for phonological or morphologically conditioned variation. Thus, to account for the variability of [e, o] to [i, u] or [e, o], Partially Ordered Theory can assume a free ranking between *e/o and Ident-JO-[hi]. The domination of *e/o over Ident-JO-[hi] predicts that [e, o] will become high vowels as a kind of default adaptation, while the reverse ranking predicts [e, o] will enter Truku without change, a kind of importation, as the preserved [e, o] will end up occurring in an environment where they normally do not appear in native words.

The adaptation of Japanese [e, o] as [i, u] or [e, o] in Truku is not conditioned by the mid vowel's position in the Japanese source, either. If it were, we would expect [e] and [o] to always map to [i, u] in word-final position, since [e] and [o] are prohibited word-finally in Truku native words (cf. the *e/o]w constraint). However, based on the present study, [e, o] in the source words are also preserved in word-final position. Although in word-final position more [e, o] become [i, u] than remain [e, o], the same tendency is also observed in non-word-final position. As the tables in (27) and (28) show, [e, o] have a higher chance of becoming high vowels whether they are in word-final or non-word-final position, suggesting that the mapping is not conditioned by the mid vowel's position in the Japanese source.

(27)

a. The adaptation of [e] in different positions

b. The adaptation of [o] in different positions

This shows that the phonotactic constraint *e/o]w in native Truku is suppressed by the loanword-sensitive faithfulness constraint in loanword adaptation (i.e., Ident-JO-[hi] >> *e/o]w), a situation of importation. Notice that the ranking ||Ident-JO-[hi] >> *e/o]w|| is crucial only in the minority pattern because the ranking for the majority pattern (i.e., ||*e/o >> Ident-JO-[hi]||) predicts that [e, o] always change to [i, u], irrespective of position. In the ranking for the minority pattern (i.e., ||Ident-JO-[hi] >> *e/o||), which allows [e, o] in the source word to be preserved, the combined ranking ||Ident-JO-[hi] >> *e/o]w, *e/o|| correctly predicts the existence of word-final [e, o] in loanwords, while the reversed ranking combined with ||Ident-JO-[hi] >> *e/o||, (i.e., ||*e/o]w >> Ident-JO-[hi] >>, *e/o||) wrongly predicts that Japanese [e] and [o] in the word-final position have to be mapped to [i] and [u].

Although the mapping of [e, o] to [i, u] does not always respect native phonotactics prohibiting word-final [e, o], it does always respect the native phonotactic constraint prohibiting [uŋ] and postvelar-Vhi sequences. Our data include two loanwords corresponding to Japanese words with [ho] and one corresponding to [ok] in Japanese, where [k] is adapted as [q] in Truku; in all these cases, [o] surfaces without change (i.e., [taihokɯ̥ ] > [tájħok] ‘Taipei’ and [nihoɴ] > [níħoŋ] ‘Japan’, [ɾoːsókɯ̥] > [ɾúsoq] ‘candle’). Ten loanwords corresponding to Japanese words with either [oŋ] or [oɴ] sequences (Japanese [ɴ] is adapted as [ŋ] in Truku) all have the Japanese [o] sounds faithfully preserved (cf. 29).Footnote 17 There are no Japanese [he] sequences in our data. However, as will be shown in section 4.2, the Japanese long vowel [eː], despite tending to enter Truku as [i], always surfaces as [e] after [ħ] in Truku loanwords (e.g., [heːtai] > [ħétaj] ‘soldier’). If the combinations of [ħo], [oq], and [oŋ] are excluded, the percentage of [o] becoming [u] in Truku approaches 85%, as summarized in (28b).

(28)

a. The adaptation of [e] in different positions (excluding [e] in postvelar environment)

b. The adaptation of [o] in different positions (excluding [oŋ] and [o] adjacent to postvelar consonants)

(29) Japanese [o] is preserved as [o] before [ŋ] coda

The fact that when entering Truku, the Japanese [e, o] vowels are more likely to become [i, u] except to satisfy the phonotactic constraints which prohibit [uŋ] and postvelar-Vhi sequences indicates that just as in native phonology, the markedness constraints *PostVel-Vhi and *uŋ dominate *e/o in loanword adaptation (cf. (6)), as illustrated in (30).

(30) ||*PostVel-Vhi, *uŋ >> *e/o|| predicts the adaptation of [o] to [o] next to [ħ] and before [ŋ] coda

In sum, for Japanese vowels that have direct correspondents in Truku, the vast majority of high vowel [i] and low vowel [a] enter Truku without change. Some exceptions to this direct mapping occur to satisfy the native phonotactics that prohibits onsetless syllables and [uŋ] or postvelar-Vhi sequences. Unlike the peripheral vowels, the mid vowels [e] and [o] in the source words, perceptually less distinctive (Gnanadesikan Reference Gnanadesikan1997, Flemming Reference Flemming2002), vary between being faithfully preserved or changing to [i] and [u]. Japanese [e] and [o] exhibit a clear tendency to be adapted as [i] and [u] due to the marked status of mid vowels. But to satisfy even higher ranked markedness constraints, *PostVel-Vhi and *uŋ, [e, o] remain mid after postvelar onsets and [o] remains [o] before velar nasal codas. Although correspondences between the source words and the loanwords are by and large sacrificed to satisfy Truku native phonotactics, the mapping of [e, o] does not conform to all native phonotactic constraints. The fact that [e, o] are preserved in word-final position where native [e, o] vowels are prohibited shows that the Truku markedness constraint *e/o]w, which outranks IO-faithfulness constraints, is suppressed to achieve better correspondence between the source words and the loanwords. Thus, the adaptation of [e, o] involves both default adaptation and importation.

4. Japanese vowels not shared by Truku

This section examines the adaptation of Japanese vowels that lack direct correspondents in Truku: Japanese high back unrounded vowel [ɯ], long vowels [aː, iː, eː, oː, ɯː], and voiceless vowels [ɯ̥, i̥].

4.1 The [ɯ] vowel

Truku has two phonemic high vowels, [i, u], and the allophone [ɨ] which occurs instead of [ə] after sibilants. When [ɯ] enters Truku, the majority (81.4%) become [u], as summarized in (31), with examples given in (32). Some [ɯ] vowels, however, enter as [o], as exemplified in (33). The examples in (34) and (35) show [ɯ] varying or becoming other vowels.

(31)

(32) ɯ > u (48/59 = 81.4%)

(33) ɯ > o (6/59 = 10.2%)

(34) ɯ > others (2/59 = 3.4%) (ɯ > m̩, ɯ > i)

(35) ɯ > variation (3/59 = 5.1%) (ɯ > u ~ ɨ, ɯ > u ~ o, ɯ > u ~ ∅)

Several points about the adaptation of [ɯ] are worth noting. First, the Japanese [ɯ] always adapts to a vowel in Truku's inventory, indicating that, while a foreign feature absent in Truku such as [e, o] in the word-final position can be imported to Truku, a foreign vowel segment cannot. The adaptation of [ɯ] is thus triggered by the *ɯ constraint.

Second, the mapping of [ɯ] to the back rounded Truku [u] rather than the front unrounded [i] shows that the backness feature is more faithfully retained than the rounding feature.Footnote 18 This conforms to the finding that features have different phonological weights (Steriade Reference Steriade, Hume and Johnson2001, Reference Steriade2002; Miao Reference Miao2005; Y. Lin Reference Lin2009) and that the backness feature of vowels is more resistant to change than other features (Y. Lin Reference Lin2009), reflected by the ranking ||Ident-JO-[bk] >> Ident-JO-[rd]||. There are two unround vowels in Truku that are featurally similar to [ɯ]: [a] ([ +bk] and [-rd]), and [ɨ], (also [ +hi]), with the only featural difference between [a] and [ɯ] being that of height. The fact that [ɯ] never becomes [a] shows that the height features (i.e., [lo], [hi]) are more resistant to change than the rounding feature (i.e., [rd]), reflected by the ranking ||Ident-JO-[lo], Ident-JO-[hi] >> Ident-JO-[rd]|| (cf. (36a) vs. (36d)). As Japanese mid vowels can become high vowels in Truku to satisfy *e/o, changing the [hi] feature value (cf. section 3.2), Ident-JO-[hi] should be crucially dominated by *e/o (cf. (36 g) vs. (36 h)). Moreover, as high vowels after postvelar consonants and [u] before [ŋ] coda become mid vowels, Ident-JO-[lo] must crucially dominate *e/o (cf. (36i) vs. (36j)). On the other hand, [ɨ] differs from [ɯ] in having no place feature. Thus, the fact [ɯ] is rarely adapted as [ɨ], appearing only in one example that varies with [u] (i.e., (35a) [sɯ́ɾippa] > [suɾípa] ~ [sɨɾípa] ‘slipper’) shows that the Max-JO-Vpl constraint, which forbids the deletion of the place feature, should outrank the Ident-JO-[rd] constraint (cf. (36a) vs. (36b)).Footnote 19

Finally, there are several examples in which /ɯ/ is adjusted to [o] (cf. (33)). A closer look at these cases shows that [ɯ] in the source words either precede a [ŋ] coda or follow a [ħ] onset. Thus, the adjustment of [ɯ] to [o], but not to [u], is again to satisfy the native phonotactic constraint against tautosyllabic [ħu] or [uŋ] sequences, conforming to the native ranking ||*PostVel-Vhi, *uŋ >> *e/o|| (cf. (30)).

(36) ||Ident-JO-[bk] >> Ident-JO-[rd]|| predicts [ɯ] is adapted as [u] but not [i]

||Ident-JO-[lo] >> Ident-JO-[rd]|| predicts [ɯ] is not adapted as [a]

||Ident-JO-[lo] >> *e/o|| predicts [ɯ] is never adapted as [a] to avoid violating *e/o

||Max-JO-Vpl >> Ident-JO-[rd]|| predicts [ɯ] is not adapted as [ɨ]

Excluding the [ħo] and [oŋ] combinations, over 90% of [ɯ] are adjusted to [u] in Truku.

4.2 The long vowels

Truku native vowels are all short. When Japanese long vowels [iː] and [aː] enter Truku, they are all mapped to their corresponding short counterparts [i] and [a]. This can be predicted by the domination of *Vː over Ident-JO-[long], which requires identity of vowel length between the source words and the loanwords. And just like the majority of [ɯ], the Japanese long [ɯː] vowels are mapped to [u]. The mappings of the long vowels are summarized in (37), with examples given in (38)–(40). No loanwords corresponding to Japanese [ɯːŋ], [çiː], or [ɸɯː] combinations, which could potentially result in the unfavourable [uŋ], [ħi], or [ħu] sequences or be adapted as [oŋ], [ħe], or [ħo], were collected (Japanese [ç] and [ɸ] are always adapted as [ħ] in Truku).

(37) iː > i (4/4 = 100%)

aː > a (11/11 = 100%)

ɯː > u (6/6 = 100%)

(38) iː > i

(39) aː > a

(40) ɯː > u

Like their short counterparts [e, o], Japanese [eː] and [oː] are not always mapped to their closest short Truku counterparts. Although there seems to be an equal chance for [eː] to be mapped to [i] and [e], the majority of [oː] (71.6%) is mapped to [u] while the rest is either mapped to [o] (10.8%) or varies between [u] and [o] (17.6%), as summarized in (41), with examples given in (42)–(45).

(41)

a. The adaptation of [e]

b. The adaptation of [o]

(42) eː > i (6/12 = 50.0%)

(43) eː > e (6/12 = 50.0%)

(44) oː > u (53/74 = 71.6%)

(45) oː > o (8/74 = 10.8%)

There is also no clear pattern as to when [eː, oː] are mapped to [i, u] and when to [e, o], other than the mirroring of the adaptation of [e, o] and [eː, oː] to [e, o] after [ħ] onsets, to satisfy native phonotactics (cf. (46)). No loanwords corresponding to Japanese [ɯːŋ] (potentially resulting in the unfavourable [uŋ]) were collected.

(46) [eː, oː] always surface as [e, o] after [ħ]

Excluding the combinations of [ħo], [ħe], and [oŋ], over 75% of the [oː] vowels are adjusted to [u] and 60% of the Japanese [eː] are adjusted to Truku [i], as summarized in (47).

(47)

a. The adaptation of [eː] (excluding [eː] adjacent to postvelar consonants)

b. The adaptation of [oː] (excluding [oːŋ] and [oː] adjacent to postvelar consonants)

Although the adaptation of [eː] and [oː] conforms to the native phonotactics against tautosyllabic postvelar consonants and high vowels, the adaptation of [eː] and [oː], just as that of [e, o], does not respect the native phonotactics against word-final [e, o] (cf. (43a), (45c)). This is readily predicted by the ranking ||Ident-JO-[hi] >> *e/o]w|| justified in section 3.2. It is true that [eː] and [oː] are more frequently adapted as [i, u] in the word-final position, but the tendency is similar elsewhere, as indicated in (48)–(49).

(48)

(49)

The adaptation of the long vowels is predicted by the constraint ranking in (36), with the addition of the Ident-JO-[long] constraint crucially dominated by *Vː, as shown in (50).

(50) ||*Vː, *PostVel-Vhi >> *e/o >> Ident-JO-[long]|| predicts the [eː, oː] > [e, o] mapping next to postvelar consonants and the [iː/eː, ɯː/ oː] > [i, u] mapping elsewhere

4.3 The voiceless vowels

Japanese has two allophonic voiceless vowels [i̥, ɯ̥], derived from [i, ɯ] between voiceless consonants or word-finally after a voiceless consonant. In Truku they are voiced, predicted by the domination of *V̥ over Ident-JO-[vce], which forbids the change of voicing in vowels.Footnote 21 As summarized in (51) and (52), as with [i, ɯ] and [iː, ɯː], the majority of Japanese [i̥] and [ɯ̥] are adapted as [i] and [u], respectively.Footnote 22 Some [i̥] and [ɯ̥] vowels are adapted as [e] and [o], but all are after postvelar onsets (e.g., (55), (56)), readily predicted by the crucial domination of *PostVel-Vhi over *e/o. As shown in (57), the adaptation of voiceless vowels can also be predicted by the constraint ranking justified above (cf. (50)), with the addition of the Ident-JO-[vce] constraint, crucially outranked by *V̥, illustrated in (57).

(51)

(52)

(53) i̥ > i

(54) ɯ̥ > u

(55) i̥ > e

(56) ɯ̥ > o

(57) ||*V̥, *PostVel-Vhi >> Ident-JO-[vce]|| predicts the [i̥, ɯ̥] > [e, o] mapping next to postvelar consonants and the [i̥, ɯ̥] > [i, u] mapping elsewhere

Nonetheless, unlike [i, ɯ] and [iː, ɯː], some voiceless vowels are also found to be deleted or replaced by [ɨ], as shown in (58)–(60). Despite the fact that the percentage of [i̥, ɯ̥] being deleted or replaced by [ɨ] is not as high as the percentage adapted as [i, u] (cf. (51), (52)), several points about the deletion/[ɨ]-replacement of the voiceless vowels are still worth noting. First, except for the two examples in (60), deletion and [ɨ]-replacement follow a general pattern: deletion takes place in word-final position (e.g., (58)), while [ɨ]-replacement occurs word-internally (e.g., (59)).

(58) Word-final voiceless vowels are deleted

(59) Word-internal voiceless vowels are replaced with [ɨ]

(60) Word-final vowels that are unexpectedly replaced with [ɨ]

Second, deletion/[ɨ]-replacement of the voiceless vowels occurs mainly after Japanese sibilants.Footnote 23 Chart (61) summarizes the distribution of the voiceless vowels after different consonants (excluding the adaptations that exhibit variations; i.e., six examples of [ɯ̥] and two examples of [i̥]; cf. (51), (52)). Among the 12 source words that have [ɯ̥] deleted/replaced with [ɨ], 10 have [ɯ̥] after Japanese sibilants (seven after the Japanese [ts] (62) and three after [s] (63)); only two have the vowel after a Japanese [k] (64). Among the six source words that have [i̥] deleted or replaced by [ɨ], one occurs after Japanese [tʃ] (65) and five after Japanese [ʃ] (66). In the loanwords collected, [ɯ̥] is also found after [ɸ], [p] and [ʃ] in the source word and [i̥] is also found after [p], [ç], and [k]. Nonetheless, as shown in (61), none of the voiceless vowels in these environments are deleted or replaced with [ɨ].

(61) Distribution of the voiceless vowels after different consonants

(62) tsɯ̥ > t(s)/ tsɨ

(63) sɯ̥ > s/ sɨ

(64) kɯ̥ > k/q

(65) tʃi̥ > ts/ t

(66) ʃi̥ > s/ sɨ

For the first point, the choice between deletion and [ɨ]-replacement is actually due to Truku native phonotactics. As mentioned, Truku has low tolerance for word-medial codas, generally allowing only nasal codas derived as a result of affixation. Since Truku also disallows complex syllable margins (*Comp-M) and word-final weak vowels (*WeakV]w), deletion of vowels word-internally would result in complex syllable margins (e.g., [sɯ̥káːto] > *[skátu] ‘skirt’), violating *Comp-M, while [ɨ]-replacement word-finally would result in word-final weak vowels (e.g., [ɡaɾásɯ̥] > *[ɣaɾásɨ] ‘glass’), violating *WeakV]w.Footnote 24 Deletion of vowels word-finally and [ɨ]-replacement word-internally are thus the options adopted in loanword adaptation.

As for the exceptional cases in (60), where the Japanese word-final voiceless vowels are unexpectedly replaced by [ɨ] rather than deleted, the first two cases are still due to native phonology. Truku words are generally disyllabic or trisyllabic (A. Lee Reference Lee2010). Monosyllabic words are not only rare but are also usually mimicry words (e.g., naq [naq] ‘nagging sound’, sing [ʃiŋ] ‘feeling of stinging pain’). This suggests that Truku native words generally follow word-minimality. While the loss of the word-final voiceless vowels in the Japanese source words in (58) still respects word minimality, the dropping of the Japanese voiceless vowel in the first two cases in (60) would result in a monosyllabic word (i.e., [ʃatsɯ̥] > *[ʃjáts] ‘top’, [ɡatsɯ̥] > *[ɣáts] ‘month’); therefore, [ɨ]-replacement, rather than vowel deletion, in (60a–b) is very likely to satisfy word minimality and can be accounted for by the domination of the constraint requiring word minimality (i.e., WdMin) over the markedness constraint prohibiting word-final weak vowels, *WeakV]w. As illustrated in (67), the proper ranking of different markedness constraints predicts that, with the exception of (60c), a Japanese voiceless vowel, when subject to [ɨ]-replacement or deletion, is replaced by [ɨ] word-internally and deleted word-finally, except to avoid generating monosyllabic loanwords.

(67) ||*Comp-M, MinWd >> *WeakV]w|| predicts word-internal [i̥, ɯ̥] > [ɨ] mapping and word-final [i̥, ɯ̥] > Ø, except to avoid monosyllabic loanwords.

One may question why the voiceless vowel is replaced by [ɨ] but not other vowels. This could be due to the low sonority of [ɨ]. Based on the sonority hierarchy given in (68), [ɨ] is the least sonorous vowel in the Truku vowel inventory. Assuming a voiceless vowel is slightly lower in sonority than the least sonorous voiced vowel (cf. (69)) and assuming faithfulness on a scale (i.e., a one-step change is more faithful than a change of more than one steps) (Gnanadesikan Reference Gnanadesikan1997, Alderete et al. Reference Alderete, Beckman, Benua, Gnanadesikan, McCarthy and Urbanczyk1999), the constraint IdentAdj(Son) in (70) can explain why voiceless vowels can be mapped to [ɨ] but not other vowels (cf. (71d) vs. (71f)) or when crucially dominating Max-JO-V, explains why voiceless vowels can be deleted (cf. (71a) vs. (71c)).

(68) Universal Sonority Hierarchy (Kenstowicz Reference Kenstowicz1997: 162, de Lacy Reference de Lacy2002: 55)

low peripheral V > mid peripheral V > high peripheral V > mid central V > high central V

(69) Universal Sonority Hierarchy (voiceless vowel included)

low peripheral V > mid peripheral V > high peripheral V > mid central V > high central V > voiceless V

(70) IdentAdj(Son): Corresponding segments must have identical or adjacent values on the Sonority scale.

(71) ||IdentAdj(Son), *WeakV]w >> Max-JO-V|| predicts word-internally [i̥, ɯ̥] is mapped to [ɨ] but not other vowels

The mapping of [ɨ] to the Japanese voiceless vowels also explains why [ɨ]-replacement and deletion of the voiceless vowels occurs only after Japanese sibilants. Consider first [ɨ]-replacement. Recall that in Truku native phonology, [ɨ] only occurs with sibilants, reflected by the constraint sib-ɨ. This constraint, when crucially dominating IdentAdj(Son), predicts that no voiceless vowels after non-sibilants can become [ɨ] (cf. (72e)). Notice that to allow a post-sibilant voiceless vowel to lose its place feature and turn into [ɨ], sib-ɨ also has to crucially dominate Max-JO-Vpl (cf. (72a) vs. (72b)). The ranking between Max-JO-Vpl and IdentAdj(Son) is also crucial. Max-JO-Vpl, when crucially dominating IdentAdj(Son), helps to predict that a word-final voiceless vowel does not delete after non-sibilants. Adapting voiceless [ɯ̥, i̥] to voiced [u, i] not only does not violate sib-ɨ but also better satisfies Max-JO-Vpl (cf. (73d) vs. (73e)).

(72) ||sib-ɨ >> Max-JO-Vpl || predicts only post-sibilant voiceless vowels are mapped to [ɨ]

(73) ||Max-JO-Vpl >> IdentAdj(Son)|| predicts word-final voiceless vowels do not delete after non-sibilants

The ranking in (72) (= 73) predicts the deletion/[ɨ]-replacement of voiceless vowels after sibilants. But not all voiceless vowels after sibilants are deleted/replaced by [ɨ] (cf. (61)). To account for the variation of [ɯ̥, i̥] between [u, i] and deletion/[ɨ]-replacement, the Partially Ordered Theory can assume the free ranking between sib-ɨ and Max-JO-Vpl. The reverse ranking of Max-JO-Vpl and sib-ɨ (i.e., ||Max-JO-Vpl >> sib-ɨ||) predicts that no voiceless vowels should be deleted or lose their place features, even after sibilants, as shown below.

(74) ||Max-JO-Vpl >> sib-ɨ|| predicts voiceless vowels are not deleted or replaced by [ɨ] even after sibilants

In conclusion, unlike voiced vowels, Japanese voiceless vowels are sometimes replaced by [ɨ] or deleted. I have assumed the input-to-loanword adaptation to be the phonetic output rather than the phonemic input of Japanese. This assumption is supported by the different behaviours between [i̥, ɯ̥] and [i, ɯ] with respect to [ɨ] replacement and vowel deletion. If the input to loanword adaptation were the phonemic input of Japanese words, the phonemically identical pairs [i̥, ɯ̥] and [i, ɯ] would be expected to exhibit uniform behaviour. The different behaviours of [i̥, ɯ̥] and [i, ɯ] thus suggest that Truku adaptation takes into account the voiceless allophones in Japanese. Therefore, an adaptation model that assumes mapping based on phonemic similarity between the donor and recipient languages (Paradis and LaCharité Reference Paradis and Lacharité1997, LaCharité and Paradis Reference Lacharité and Paradis2005) would fail to provide a good explanation for the discrepancy between the adaptations of Japanese voiceless and voiced vowels in Truku. The greater susceptibility of voiceless vowels – perceptually weaker than their voiced counterparts – to deletion or [ɨ]-replacement suggests that perceptual saliency influences loanword adaptation. This indicates that loanword adaptation is shaped by auditory perception rather than solely by phonological structure.

4.4 Stress-related adaptation

As mentioned in section 4.3, some Japanese voiceless vowels are replaced by [ɨ] when entering Truku. Given that Truku has a phonological process of pre-tonic vowel reduction, it is of interest to know whether the [ɨ] replacement of the Japanese voiceless vowel is relevant to the native process of vowel reduction. There are reasons to reject this possibility. First, while vowel reduction in native phonology targets pre-tonic vowels, Truku [ɨ] corresponding to Japanese voiceless vowels do not always occur before the stressed syllable. While Japanese accent is lexically specified, hence unpredictable (Beckman and Pierrehumbert Reference Beckman and Pierrehumbert1986), stress in Truku falls predictably on the penultimate syllable. The data collected in this study show that the stress of a Japanese loanword still falls on the penultimate position irrespective of the accent of the source word, as in (75).

(75)

The examples in (62c–d) and (66b–c) show that the [ɨ] vowel does not always occur before the stressed syllable in loanwords. Besides, even though words like [ʔajsɨkuɾímu] ‘ice cream’ (< [aisɯ̥kɯɾíːmɯ]) and [sɨkátu] ‘skirt’ (< [sɯ̥káːto]) have [ɨ] before the penultimate syllable, other pre-tonic vowels, such as [a] and [u] in [ʔajsɨkuɾímu], are not reduced. As a matter of fact, vowels that correspond to voiced vowels in Japanese seldom undergo reduction even in pre-penultimate syllables. Of the 274 Japanese loanwords and more than 600 vowel tokens collected in this study, only three vowels corresponding to Japanese voiced vowels undergo pre-penultimate reduction, as shown in (76).

(76) Pre-tonic vowel reduction

The fact that the majority of the pre-penultimate vowels in loanwords are not reduced shows that it is more important to conserve the vowel place feature in loanword adaptation than to respect the markedness constraint of vowel reduction. The importation of this foreign feature is captured by the domination of the loanword-sensitive faithfulness constraint Max-JO-Vpl over the markedness constraint *Pre-tonic-Vpl, which in return outranks the native IO faithfulness constraint, as illustrated in (77).

(77) ||Max-JO-Vpl >> *Pre-tonic-Vpl >> Max-IO-Vpl|| predicts the lack of pre-tonic vowel reduction in loanwords

It is worth noting, however, that while the vast majority of the simple (unaffixed) loanwords do not respect the native constraint of *Pre-tonic-Vpl, pre-penultimate vowels are reduced when the simple loanwords undergo suffixation. This study collected 13 suffixed loanwords, all involve pre-penultimate vowel reduction, as illustrated in (78).

(78)

The blocking of pre-penultimate vowel reduction in unaffixed loanwords and its application in affixed loanwords can be considered a kind of derived environment effect, or nonderived environment blocking (NDEB; Kiparsky Reference Kiparsky, Hargus and Kaisse1993), as pre-penultimate vowel reduction in the Japanese loanwords in Truku occurs only in morphologically derived environments. Because the vowel reduction is derived in a purely morphological sense (i.e., the affix doesn't provide some of the phonologically relevant material for vowel reduction to take place), it belongs to a special kind of NDEB, also termed TETU blocking or false blocking (Kiparsky Reference Kiparsky, Hargus and Kaisse1993, Burzio Reference Burzio, Booij, Ralli and Scalise1997, Inkelas Reference Inkelas2000, Łubowicz Reference Łubowicz2000). In Burzio, this special kind of NDEB is accounted for by the TETU ranking ||IO-faith >> Markedness >> OO-Faith||. Burzio assumes that a simple unaffixed output form stands in an IO faithfulness relation to its corresponding input form and that a derived affixed form stands in an OO faithfulness relation to its corresponding unaffixed form. According to Burzio, there is no IO-faithfulness relation for an affixed form and, therefore, a derived affixed form satisfies IO-faithfulness constraint vacuously. Should the derived form have an IO-faithfulness relationship, the relevant alternation would also be blocked in the affixed output due to the higher-ranked IO-faith in the TETU ranking. In other words, an unaffixed form needs to be faithful to the input due to IO-faith, but an affixed form, which has no IO-faithfulness relation, has to obey the markedness constraint, which dominates OO-Faith.

With respect to the derived environment effect in Truku loanwords, Burzio's TETU blocking analysis can successfully account for the blocking of pre-penultimate vowel reduction in simple loanwords, except that the simple loanword (unlike in Burzio's TETU ranking) stands in a JO-faithfulness rather than IO-faithfulness relation to its corresponding Japanese source word. However, the derived loanword stands in an OO-faithfulness relation to its corresponding simple loanword, as shown in (79). The simple loanword does not undergo pre-penultimate vowel reduction due to the domination of JO-faithfulness over *Pre-tonic-Vpl. On the other hand, since the affixed loanword has no JO-faithfulness relation and is governed by the OO-faithfulness constraint, the markedness constraint of *Pre-tonic-Vpl becomes top-priority and is respected in the affixed form, as shown in (80).

(79) TETU ranking for the derived environment effect in Truku loanword adaptation

Max-JO-Vpl >> *Pre-tonic-Vpl >> Max-OO-Vpl

(80) ||Max-JO-Vpl >> *Pre-tonic-Vpl >> Max-OO-Vpl|| predicts suffixed loanwords undergo pre-tonic vowel reduction

The derived environment effect in Truku loanword adaptation conforms to the general idea that morphologically integrated loanwords are more likely to be nativized than bare loanwords (Bloomfield Reference Bloomfield1993). Jurgec (Reference Jurgec2014), for instance, reports a similar derived environment effect related to the differential adaptation of suffixed vs. unsuffixed forms in Dutch and Ukrainian speakers’ pronunciation of English loanwords. Some Dutch speakers pronounce recent loanwords from English with the foreign segment [ɹ], but only if the loanwords are unsuffixed; the foreign [ɹ] is replaced by the native [ʀ] in suffixed words (Op[ɹ]ah ‘Oprah’ > Op[ʀ]ah-tje, *Op[ɹ]ah-tje ‘Oprah-dim’).

In native Truku, despite the fact that it is not clear whether pre-penultimate vowel reduction is also active in the underived root form (since the alternations between full and reduced vowels are available only under suffixation), none of the pre-penultimate vowels in the root form are full, showing that *Pre-tonic-Vpl is satisfied in both the derived and the underived environment in native words. But in loanword adaptation, it is clear that pre-penultimate vowel reduction applies only in derived but not simple loanwords. As mentioned, for Burzio's TETU analysis to work, the affixed output must not refer to information in the input. An affixed loanword must also not refer to the Japanese source word; otherwise, pre-penultimate vowel reduction would be blocked due to Max-JO-Vpl, which dominates *Pre-tonic-Vpl. In loanword adaptation, it is reasonable that the affixed loanword should not refer to the Japanese source word, as it becomes a new lexical item in Truku. Therefore, the affixed loanword should no longer have access to the source word and should not be governed by the faithfulness constraint regulating the correspondence between loanwords and their corresponding source words (i.e., Max-JO-Vpl). The derived environment effect in Truku loanword adaptation shows that in addition to IO faithfulness and JO faithfulness constraints, it is essential to identify OO correspondence between loanwords and affixed loanwords.

5. Conclusion

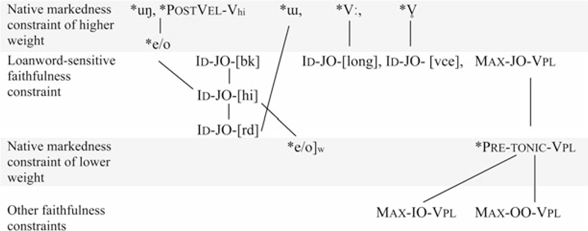

I have shown that Japanese vowels that have direct correspondents in Truku are generally faithfully preserved, while those lacking direct correspondents are generally minimally modified and adapted as the closest vowels. The minimal modification of the Japanese [ɯ(ː)] to [u] but not [i] conforms to the finding that features have different phonological weights and that the backness feature of vowels is more resistant to change than other height or rounding features. This is reflected by the domination of the loanword sensitive faithfulness constraints (||Ident-JO-[bk] >> Ident-JO-[hi] >> Ident-JO-[rd]||). Preservations are not always achieved due to the satisfaction of native markedness constraints. Most adaptations of [e(ː)] and [o(ː)] vowels to [i] and [u] are to satisfy the native markedness constraint, prohibiting the universally marked mid vowels. This is reflected by the domination of the native markedness constraint over the loanword faithfulness constraint (||*e/o >> Ident-JO-[hi]||). In certain environments (i.e., after postvelar consonants and before velar nasal), however, the [ɯ(ː)] vowel is mapped to a lowered [o] and the [e(ː)] and the [o(ː)] vowels are mapped to the more marked [e, o]. These mappings are due to the native markedness constraint ranking, with the sequential markedness constraint prohibiting [ħu] and [uŋ] outranking *e/o (i.e., ||*PostVel-Vhi, *uŋ >> *e/o||).

Although native phonology is generally respected in loanword adaptation, two native markedness constraints are not. The first is that mid vowels, prohibited word-finally in native words, are found in the final position of some loanwords. The second is that pre-tonic vowels are not reduced in simple loanwords, even though pre-tonic vowel reduction applies normally in affixed loanwords, exhibiting a derived environment effect. Both are reflected by the domination of the relevant loanword sensitive faithfulness constraints over the native markedness constraints (i.e., Ident-JO-[hi] >> *e/o]w for the former and ||Max-JO-Vpl >> *Pre-tonic-Vpl|| for the latter). The two exceptions show that native markedness constraints are also of different phonological weight and are valued differently in loanword adaptation. Markedness constraints of higher weight (i.e., *PostVel-Vhi, *uŋ, *e/o) are satisfied by sacrificing the identity between source words and loanwords (i.e., ||*PostVel-Vhi, *uŋ >> *e/o >> Ident-JO-[hi]||); on the other hand, markedness constraints of lower weight (i.e., *e/o]w, *Pre-tonic-Vpl) are suppressed to achieve better source-loanword identity (i.e., Ident-JO-[hi] >> *e/o]w; ||Max-JO-Vpl >> *Pre-tonic-Vpl||), as summarized in (81).

(81)

The fact that foreign features can be imported in Truku also shows that it is essential to distinguish between native and loanword-sensitive faithfulness constraints, with the latter dominating the native markedness constraints and the former outranked by them (e.g., ||Max-JO-Vpl >> *Pre-tonic-Vpl >> Max-IO-Vpl||). It is not clear why foreign vowel segments can never be imported into Truku while foreign features can. But the importation of the foreign features can lead to the so-called ‘marginal contrast’, a phonological contrast whose distributions lie somewhere between being fully separate and completely overlapping (Martin et al. Reference Martin, van Heugten, Kager and Peperkamp2022). Marginal contrast happens when imported words contain sounds that are not contrastive (but allophonic) in the borrowing language. For instance, P. Lee (Reference Lee2013) reports how [ʃ] and [s], allophonic in native Korean, become contrastive in some words due to the borrowing of English words such as show. In Truku native phonology, due to the absence of word-final [e, o] and pre-penultimate vowel reduction, [e, o] are not contrastive with other vowels word-finally and full vowels are not contrastive with reduced (/weak) vowels [ə, ɨ] in pre-tonic syllables. But the borrowings of Japanese words with word-final [e, o] and words with pre-tonic full vowels lead to the emergence of marginal contrasts.

Finally, Truku loanword adaptation shows an interesting derived environment effect involving the blocking of the pre-penultimate vowel reduction in unaffixed loanwords and its application in affixed loanwords. The fact that a native markedness constraint not respected in loanword adaptation (i.e., *Pre-tonic-Vpl) may become active when the loanwords further undergo affixation shows that in addition to IO faithfulness and JO faithfulness constraints, it is essential to identify the correspondence between loanwords and affixed loanwords (i.e., ||Max-JO-Vpl >> *Pre-tonic-Vpl >> Max-OO-Vpl||).

In addition to native phonology, perceptual saliency also plays an important role in loanword adaptation in Truku. This is evidenced by the fact that the perceptually weaker mid (as opposed to peripheral) vowels are more likely to exhibit variation, and that several voiceless (but not voiced) vowels are found to undergo [ɨ] replacement or deletion. Unlike the Phonological Approach (Paradis and LaCharité Reference Paradis and Lacharité1997, LaCharité and Paradis Reference Lacharité and Paradis2005), which considers loanword adaptation to be primarily based on a phoneme-to-phoneme mapping, both the Perception Approach (Peperkamp and Dupoux Reference Peperkamp and Dupoux2003, Peperkamp Reference Peperkamp, Ettlinger, Fleischer and Park-Doob2005) and the Perception-Phonological Approach (Kenstowicz Reference Kenstowicz2001/2004, Reference Kenstowicz2007; Yip Reference Yip2006; Y. Lin Reference Lin2008) consider the input to loanword adaptation and processing to be perceptual in nature, but they differ with respect to the role phonology plays in the process of adaptation. While the Perception Approach considers that the adaptation of non-native sounds occurs solely on the perceptual level and that phonology plays only an indirect role in determining “which sounds and sound structures are available for the non-native ones to map onto” (Peperkamp et al. Reference Peperkamp, Vendelin and Nakamura2008: 131), the Phonetic-Phonology Approach argues that the native language's phonology plays a direct role in shaping perceived acoustic signals from the source language. The findings of loanword adaptation in Truku support the Phonetic-Phonology Approach. First of all, mappings of Japanese and Truku vowels do not apply on a phoneme-to-phoneme basis. The fact that phonemically identical [i̥, ɯ̥] and [i, ɯ] behave differently with respect to [ɨ] replacement and deletion shows that vowel adaptation crucially refers to non-contrastive phonetic details of the Japanese input. Voiceless vowels are more likely to be replaced by [ɨ] or deleted, presumably because voiceless vowels are perceptually weaker than their voiced counterparts. That input-to-loanword adaptation is more likely to be based on auditory perception also finds support from the fact that Truku mid vowels are not only less likely to be faithfully retained but also exhibit more variation than high and low vowels, since unlike peripheral high and low vowels, mid vowels are perceptually less distinctive. Despite the fact that auditory perception places an important role in the adaptation of Japanese vowels in Truku, it cannot be accounted for by the Perception Approach, which considers loanword adaptation to take place entirely on the perceptual level and as the result of misperception. In particular, the variation seen in the adaptation of the Japanese mid vowels would be hard to explain with a purely perceptual account, since the same vowel would not expected to be perceived differently. As seen here, the variable adaptation of the mid vowels is partly due to Truku native phonology, which prohibits [uŋ] sequences and tautosyllabic adjacency of mid vowels and postvelar consonants. The fact that Truku phonotactics such as *[ħi], *[ħu], and *[uŋ], no complex syllable margins, and no onsetless syllables are always respected shows that Truku phonology also plays an important role in shaping the non-native sounds perceived. Therefore, the Perception-Phonology approach appears to best account for vowel adaptation in Truku loanwords.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to my Truku consultants Iyuq Ciyang and Tusi Yudaw (alphabetically ordered) for their help with the language data. I would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers and the editors for their valuable comments. All possible errors are my own responsibility. This study is supported by Taiwan's Ministry of Science and Technology, with the project number MOST 109-2410-H-003-109 -.