1. Introduction

This article addresses the observation from Jordanian Arabic (JA) that the object of an obligatorily transitive predicate can drop in SVO clauses without the use of an object pronominal element on the verb as long as the referent of the dropped object is already mentioned or identified in the preceding discourse.Footnote 1 Object drop is, on the other hand, totally prohibited in VSO clauses, even if the referent of the object is already mentioned in the previous discourse. Consider the contrast between SVO clauses in (1) and VSO clauses in (2).

(1)

a. ʔiz-zalameh ɣassal (ʔil-ʔawa:ʕi)

def-man wash.pst.3sg.m (def-clothes)

‘The man washed (the clothes).’

b. ʔil-mudi:r waʕad (ʔil-muwaðˁðˁafi:n)

def-manager promise.pst.3sg.m (def-employees)

‘The manager promised (the employees).’

c. Ɂumm-ij rabb-at (Ɂuwla:d ʔuxt-ij)

mother-my raise.pst-3sg.f (children sister-my)

‘My mother raised (my sister's children).’

d. ʔil-ʕami:deh na:qaʃ-at (mawðˁu:ʕ ʔil-ʔidʒa:za:t)

def-dean.f discuss.pst-3sg.f (subject def-vacations)

maʕ ʔil-dʒami:ʕ

with def-all

‘The dean discussed (the subject of vacations) with all (of us).’

(2)

a. ɣassal ʔiz-zalameh *(ʔil-ʔawa:ʕi)

wash.pst.3sg.m def-man def-clothes

‘The man washed the clothes.’

b. waʕad ʔil-mudi:r *(ʔil-muwaðˁðˁafi:n)

promise.pst.3sg.m def-manager def-employees

‘The manager promised the employees.’

c. rabb-at Ɂumm-ij *(Ɂuwla:d ʔuxt-ij)

mother-my raise.pst-3sg.f children sister-my

‘My mother raised my sister's children.’

d. na:qaʃ-at ʔil-ʕami:deh *(mawðˁu:ʕ ʔil-ʔidʒa:za:t)

discuss.pst-3sg.f def-dean.f subject def-vacations

maʕ ʔil-dʒami:ʕ

with def-all

‘The dean discussed the subject of vacations with all (of us).’

This article argues that SVO sentences with an object gap contain an instance of a dropped argument (i.e., an elided object) rather than VP ellipsis. It also provides a syntactic analysis of SVO sentences with an object gap and accounts for the ban on object drop in VSO clauses.

We present the word order patterns of Jordanian Arabic in section 2. In section 3, we discuss in more detail the observation that the object in certain contexts can drop in SVO sentences but not in VSO sentences. We argue that the nature of the elided object can be identified as a familiar topic using Frascarelli and Hinterholzl's (Reference Frascarelli, Hinterholzl, Schwabe and Winkler2007) terminology. Section 4 presents three pieces of evidence that SVO sentences with an object gap (OG) (SVΔ) contain an instance of a dropped argument rather than VP ellipsis. These tests include the modified Park-Oku test, the non-availability of sloppy interpretations, and the presence of the remnant VP material in their canonical positions. Section 5 introduces our argument that the subject in SVΔ sentences serves as a topical element, situated in the CP zone of the clause (see Rizzi Reference Rizzi and Haegeman1997) rather than being located in Spec,TP/Spec,vP. In section 6, we attempt to identify the syntactic positions that are filled with the elided object as well as the thematic subject in SVΔ sentences, proposing that the subject is located in the CP as a topic. Section 7 concludes.

2. Sentence structure of Jordanian Arabic

In Jordanian Arabic (JA), SV(O) is the quantitatively predominant unmarked word order, followed directly by VS(O) (El-Yasin Reference El-Yasin1985, Al-Shawashreh Reference Al-Shawashreh2016). Other word orders (VOS, OVS, OSV, and SOV) also occur; however, they are far less frequent (Al-Shawashreh Reference Al-Shawashreh2016, Jarrah and Abusalim Reference Jarrah and Abusalim2021). Consider the following examples representing all word order patterns used in JA (all translations are approximate):

(3)

a. ʔiz-zalameh ʔiʃtara: ʔitˤ-tˤa:wleh (SVO)

def-man buy.pst.3sg.m def-table

‘The man bought the table.’

b. ʔiʃtara: ʔiz-zalameh ʔitˤ-tˤa:wleh (VSO)

buy.pst.3sg.m def-man def-table

‘The man bought the table.’

c. ʔiz-zalameh ʔitˤ-tˤa:wleh ʔiʃtara:-ha (SOV)

def-man def-table buy.pst.3sg.m-it

‘The man, he bought the table.’

d. ʔiʃtara: ʔitˤ-tˤa:wleh ʔiz-zalameh (VOS)

buy.pst.3sg.m def-table def-man

‘The man, he bought the table.’

e. ʔitˤ-tˤa:wleh ʔiz-zalameh ʔiʃtara:-ha (OSV)

def-table def-man buy.pst.3sg.m-it

‘The table, the man bought it.’

e. ʔitˤ-tˤa:wleh ʔiʃtara:-ha ʔiz-zalameh (OVS)

def-table buy.pst.3sg.m-it def-man

‘The table, the man bought it.’

One important feature of JA, as compared to Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), is that it does not display overt case or mood markings on nouns and verbs, respectively (Jarrah and Alshamari Reference Jarrah and Alshamari2017, Jarrah Reference Jarrah2023). Additionally, JA does not show subject-verb agreement asymmetries, unlike MSA. Verbs in JA express full agreement with their subjects (in person, number, and gender) irrespective of the word order used, as already shown by all examples in (3) above. Note here that JA, like other Arabic varieties, is a pro-drop language, so an unexpressed pronoun can freely occur with all persons in all tenses (Al-Shawashreh Reference Al-Shawashreh2016).

Another important feature of JA, as compared to MSA, is that JA freely allows SVO sentences with an indefinite, non-specific subject. For example, the following sentence is grammatical in JA, while its counterpart in MSA would be deemed ungrammatical.

(4) zalameh ʔiʃtara: ʔitˤ-tˤa:wleh

man buy.pst.3sg.m def-table

‘A man bought the table.’

Jarrah and Abusalim (Reference Jarrah and Abusalim2021) argue that in JA, SVO sentences (unlike VSO) place no restrictions on the form of the subject (along these lines, see also Al-Shawashreh Reference Al-Shawashreh2016, Jarrah Reference Jarrah2019b). Drawing on a two-million-word corpus of naturally occurring data from JA, Jarrah and Abusalim (Reference Jarrah and Abusalim2021) found that the subject in VSO clauses, unlike SVO clauses, should be either a definite entity or a modified, indefinite entity. Jarrah and Abusalim (Reference Jarrah and Abusalim2021) proposed that the subject in VSO clauses is a topic or a focus, located in the so-called low IP area (cf. Belletti Reference Belletti and Rizzi2004), while the subject in SVO clauses can be a true subject, located in Spec,TP.

3. Object drop in JA

In this section, we investigate important aspects of the observation that an object can drop in SVO clauses but not in VSO clauses in JA. We discuss the discourse restrictions on object drop, the fact that the object drop is insensitive to the type of the predicate, our assumption that the elided object is a familiar topic, the occurrence of this observation in Najdi Arabic, and the assumption that null objects can be of different species and hence are not amenable to the same syntactic analysis.

3.1. Discourse restrictions on object drop

Although, as we have seen in section 1, the object in SVO clauses in JA can drop, this object drop is restricted, in that the referent of the dropped object must be mentioned (or identified) in the previous discourse. For instance, in the following dialogue, the referent of the dropped object in Speaker A's second utterance (which appears in italics) can be identified as ‘our relatives and other people’, who were already mentioned in the previous discourse (i.e., in Speaker B's first utterance).

-

(5) Speaker A: ʕurs-ij l-isbu:ʕ ʔil-dʒa:j wa yu:sef

wedding-my def-week def-next and Yousef

ʔistaʔdʒar-l-ij be:t muʔaqqat

rent.pst.3sg.m-to-me house temporary

‘My wedding (party) is next week, and Yousef rented a temporary house for me.’

Speaker B: ʕazam-tu ɡara:jib-ku wa l-ʕa:lam

invite-pst-3pl.m relatives-your and def-people

‘Have you invited your relatives and (other) people?’

Speaker A: Ɂabu:-ij ʕazam (SV)

father-my invite.pst.3sg.m

Literally: ‘My father invited.’

Intended: ‘My father invited them.’

Speaker B: tama:m, ʕala:-xe:r ʔinʃa:llah

alright on-good if.God.willing

‘Alright! May it all be fine!’

By contrast, when the referent of the elided object is not mentioned or identified in the previous discourse, the sentence is ungrammatical. For instance, the understood object tˤalaba:t ‘applications’ in the following example should be mentioned, not elided:

-

(6) Speaker A: ʔimba:riħ ʔil-mudi:r ʔiʃtamaʕ fi:-hum

yesterday def-principal meet.pst.3sg.m with-them

‘Yesterday, the (school) principal met with them.’

Speaker B: ʔil-murʃid kam:an waqqaʕ *(tˤalaba:t) l-tˤ-tˤula:b

def-counselor also sign.pst.3sg.m applications to-def-students

‘The counselor also signed applications for the students.’

Notice here that if the VSO word order is used in Speaker A's second utterance in the dialogue in (5) above, instead of the SVO word order, the sentence is ungrammatical, as shown in (7):

-

(7) Speaker A: ʕurs-ij l-isbu:ʕ ʔil-dʒa:j wa yu:sef

wedding-my def-week def-next and Yousef

ʔistaʔdʒar-l-ij be:t muʔaqqat

rent.pst.3sg.m-to-me house temporary

‘My wedding (party) is next week, and Yousef rented a temporary house for me.’

Speaker B: ʕazam-tu ɡara:jib-ku wa l-ʕa:lam

invite-pst-3pl.m relatives-your and def-people

‘Have you invited your relatives and (other) people?’

Speaker A: *ʕazam Ɂabu:-ij (VS)

invite.pst.3sg.m father-my

Literally: ‘My father invited.’

Intended: ‘My father invited them.’

The ungrammaticality of Speaker A's second sentence in (7) can be taken as evidence that the object cannot drop in VSO sentences even if its referent is already established in the previous discourse.

It is important to mention here that an SVO clause with an elided object is judged as odd or deviant in out-of-the-blue neutral contexts. For example, SVO sentences with a dropped object can never occur as an appropriate response to ‘what's-up’ questions which normally presuppose no previous discourse, whether the understood object is a definite or an indefinite element. Consider the following example:

(8) A: ʃu: fi:

what there

‘What is up?’

B: *Ɂabu:-ij ʕazam

father-my invite.pst.3sg.m

Intended: ‘My father invited the people/people.’

Against this background, we propose that the object in SVO clauses can only drop if its discourse antecedent is established in the preceding context. We propose that object drop in JA is an instance of what Hankamer and Sag call a surface anaphor, which requires “a coherent syntactic antecedent in surface structure and otherwise behaves as a purely superficial syntactic process” (Reference Hankamer and Sag1976: 392, emphasis added).

3.2. Object drop is insensitive to the type of the predicate

After surveying the syntactic behaviour of 150 transitive predicates in JA, we found that the object can drop in SVO clauses regardless of the type of predicate used (e.g., (a)telic predicates, experienced/psych predicates, etc.). By contrast, the object cannot drop in VSO clauses with any type of predicate. For instance, the examples in (9)–(10) clearly show that transitive telic and atelic predicates behave similarly with respect to the use of a dropped object in SVO but not VSO clauses. The relevant previous discourse in these examples appear in (9a) and (10a) respectively.

(9)

a. ʔimba:riħ ʃuft ʔil-be:t wa-ʔana bi-s-sija:rah

yesterday see.pst.3sg.m def-house and-I with-def-car

‘Yesterday, I saw the house while I was driving.’

b. ʔiz-zalameh bana: (ʔil-be:t) bi-sbu:ʕ (Telic)

def-man build.pst.3sg.m (def-house) in-week

‘The man built the house in one week.’

c. *bana: ʔiz-zalameh (ʔil-be:t) bi-sbu:ʕ

build.pst.3sg.m def-man (def-house) in one week

Intended: ‘The man built (the house) in one week.’

(10)

a. le:ʃ ʔin-na:s tˤilʕ-u:

why def-people leave.pst-3pl.m

‘Why did the people leave?’

b. ʔisˤ-sˤo:t ʔazʕadʒ (ʔin-na:s) (Atelic)

def-sound annoy.pst.3sg.m (people)

‘The sound annoyed (the people).’

-

c. *ʔazʕadʒ ʔisˤ-sˤo:t (ʔin-na:s)

annoy.pst.3sg.m def-sound (people)

‘The sound annoyed (the people).’

Likewise, the examples in (11)–(12) below indicate that the ban on the use of an OG in VSO clauses holds with (non-)experienced/(non-)psych predicates, with the relevant previous discourse appearing in (11a) and (12a) respectively.

(11) (Experienced/psych)

a. ke:f ʕala:qat ra:ma ʔib-ha:ʃim

how relation Rama with-Hashem

‘How is the relation between Rama and Hashem?’

b. ra:ma bitħibb (ha:ʃim) ʔikθi:r

Ra:ma love.ipfv.3sg.f (Hashem) very much

‘Rama loves (Hashem) very much.’

c. *bitħibb ra:ma (ha:ʃim) ʔikθi:r

love.ipfv.3sg.f Rama (Hashem) very much

Intended: ‘Rama loves (Hashem) very much.’

(12) (Non-experienced/non-psych)

a. ke:f ʕala:qat Ɂabu:-k wa ɡara:jbu-h

how relation father-your and relatives-his

‘How is the relation between your father and his relatives?’

b. Ɂabu:-ij ʕazam (ɡara:jbu-h) ʕa-l-ʕurus

father-my invite.pst.3sg.m (relatives-his) to-def-wedding

‘My father invited (his relatives) to the wedding.’

c. *ʕazam Ɂabu:-ij (ɡara:jbu-h) ʕa-l-ʕurus

invite.pst.3sg.m father-my (relatives-his) to-def-wedding

Intended: ‘My father invited (his relatives) to the wedding.’

The examples in (9)–(12) show that the ban on the use of an OG in VSO clauses is not related to the type of the predicate (e.g., telic vs. atelic; (non-)experienced/(non-)psych, etc.). Therefore, we propose that the ban on the use of an OG in VSO clauses must be related not to the event structure of the predicate, but rather to the syntactic derivation of VSO and SVO clauses.Footnote 2

3.3. The elided object is a familiar topic

We propose that the dropped object in SVO clauses, preceded by a previous mention of the referent of the elided object, functions as a familiar topic that refers back to given information in the discourse (Frascarelli Reference Frascarelli2007; see also Pierrehumbert and Hirschberg Reference Pierrehumbert, Hirschberg, Cohen, Morgan and Pollack1990). As discussed by Frascarelli and Hinterholzl (Reference Frascarelli, Hinterholzl, Schwabe and Winkler2007), familiar topics are D(iscourse)-linked constituents that refer to background information or used for topic continuity (Givón Reference Givón1983). This categorization of elided objects in SVO clauses as familiar (continuing) topics is consistent with the fact that these elided objects should refer to an already established Aboutness topic. According to Frascarelli and Hinterholzl (Reference Frascarelli, Hinterholzl, Schwabe and Winkler2007), one major function of familiar topics is that they re-establish (through mentioning or referring to) the Aboutness topic of the relevant discourse. Consider the following example, where the whole discourse revolves around the wife of one of the interlocutors’ friends.

-

(13) Speaker A: binnisbeh la-marat-uh, baʃu:f ʔil-ʔumu:r muʕaqqadeh

as for-wife-his see.impf.1sg def-matters complicated

‘As for his wife, I see that (their) matters are complicated (so their marriage may fail).’

Speaker B: marat-uh badd-ha sija:seh

wife-his want-3sg.f politics

Literally: ‘His wife wants politics.’

Idiomatically: ‘His wife should be better treated with kindness and appeasement.’

Speaker A: ja:zam ke:f!

man how

ja:ser ʔiħtaram wu-wadʒdʒab

Yasir respect.pst.3sg.m and-admire-.pst.3sg.m

wu-saffar

and-travel.caus-pst.3sg.m

‘Man, how comes! Yasir respected and admired her and accompanied her on journeys (for leisure).’

The expression binnisbeh la ‘as for’ is used in JA to introduce Aboutness topics (Jarrah Reference Jarrah2019b). Therefore, the Aboutness topic in the exchange above is maratuh ‘his wife’, which is an element that is referred to by the elided object in Speaker A's second utterance.Footnote 3 According to Frascarelli and Hinterholzl (Reference Frascarelli, Hinterholzl, Schwabe and Winkler2007), a topic, which is first shifted to in the conversation, appears as an Aboutness topic, while other references to this topic in the same discourse are regarded as familiar topics. The elided object in SVO clauses is another reference to the Aboutness topic.

3.4. Object drop in Najdi Arabic

Before we introduce our account of object drop in JA, it should be mentioned that Najdi Arabic also allows the object to be dropped in SVO clauses but not in VSO clauses, provided the referent has already been mentioned in the discourse. Note that both SVO and VSO are productively used in Najdi Arabic (Alshamari Reference Alshamari2017), as the following examples demonstrate:

(14)

a. ʔar-ridʒa:l ʕazam (dʒama:ʕt-uh)

def-man invite.pst.3sg.m (relatives-his)

‘The man invited (his relatives).’

b. ʔal-ħurmah ɣassal-at (ʔal-mala:bis)

def-woman wash.pst-3sg.f (def-clothes)

‘The woman washed (the clothes).’

c. ʔal-mudi:r na:qaʃ ʔal-xitˤa:ba:t

def-manager discuss.pst.3sg.m (def-reports)

‘The manager discussed (the reports).’

(15)

a. *ʕazam ʔar-ridʒa:l (dʒama:ʕt-uh)

invite.pst.3sg.m def-man (relatives-his)

Intended: ‘The man invited (his relatives).’

d. *ɣassal-at ʔal-ħurmah (ʔal-mala:bis)

wash.pst-3sg.f def-woman (def-clothes)

Intended: ‘The woman washed (the clothes).’

e. *na:qaʃ ʔal-mudi:r ʔal-xitˤa:ba:t

discuss.pst.3sg.m def-manager (def-reports)

Intended: ‘The manager discussed (the reports).’

The restriction on object drop in SVO (but not in VSO) clauses is therefore not an idiosyncratic property of JA, as Najdi Arabic exhibits a similar phenomenon.

3.5. Object drop and the (in)definiteness status of the elided object

An anonymous reviewer points out that the object can drop in contexts where it is perceived as an indefinite element, challenging our account that the elided object is a topic. Consider the example in (16):

(16) ʔaħmad bana: be:t wa kama:n

Ahmad build.pst.3sg.m house and also

ʔimħammad bana: (be:t)

Mohammad build.pst.3sg.m house

’Ahmad built a house, and Mohammad also built (one).’

In (16), the object be:t ‘a house’ can drop from the second clause, and the sentence remains grammatical. However, we propose that the identity of the elided object in sentence (16) is different from that of the elided object in the type of sentences discussed in this article (i.e., the object refers back to a referent in the preceding discourse). For example, in the following discourse the indefinite object be:t ‘a house’ used in Speaker A's first utterance is dropped in Speaker B's second utterance, even though it does not refer to the same house referred to by Speaker A:

-

(17) Speaker A: dʒa:rna bana: be:t ʔib-ʕamma:n

neighbour-our build.pst.3sg.m house in-Amman

wa ʔastaqa:l min waðˤi:ft-uh

and resign.st.3sg.m from job-his

‘Our neighbour built a house in Amman and resigned from his job.’

Speaker B: le:ʃ bana: ʔib-ʕamma:n kawnuh

why build.pst.3sg.m in-Amman being

ʔistaqa:l min waðˤi:ftuh

resign.st.3sg.m from job-his

‘Why did he resign from the job since he built (a house) in Amman?’

Speaker A: biħki ʔinnuh raħ jiftaħ biznis

say.impf.3sg.m that will open.impf.3sg.m business

‘He is saying that he will start a business.’

Speaker B: ʕala fikrah ʔamm-i bana: kama:n ʔib-ʕamma:n

By the way uncle-my build.pst.3sg.m also in-Amman

‘By the way, my uncle also built (a house) in Amman.’

A point that bears mentioning here is that a VSO word order can be used in Speaker B's second utterance, while the sentence remains grammatical, as shown in (18):

-

(18) Speaker B: ʕala fikrah bana: ʔamm-i kama:n ʔib-ʕamma:n

by the way build.pst.3sg.m uncle-my also in-Amman

‘By the way, my uncle also built (a house) in Amman.’

On the other hand, a VSO sentence is not an option when the null object refers back to an entity that is mentioned in the discourse, as shown in the following example:

-

(19) Speaker A: dʒa:rna ʕazam ʔal-mudi:r ʔib-ʕamma:n

neighbour-our invite.pst.3sg.m def-manager in-Amman

‘Our neighbour invited the manager [to meet him] in Amman.’

Speaker B: le:ʃ ʕazam ʔib-ʕamma:n kawn

Why invite.pst.3sg.m in-Amman being

ʔal-mudi:r b-irbid

def-manager in-Irbid

‘Why did he invite (the manager) [to meet him] in Amman when the manager (is living) in Irbid?’

Speaker A: biħki ʔinn-uh ka:n ʕind-hum mawʕid ʔib-ʕamma:n

say.impf.3sg.m that was with-them appointment in-Amman

‘He is saying that they had an appointment in Amman.’

Speaker B: *ʕala fikrah ʕazam ʕamm-i ʔib-ʕamma:n kama:n

by the way invite.pst.3sg.m uncle-my in-Amman also

Intended: ‘By the way, my uncle invited (the manager) [to meet him] in Amman as well.’

The use of the SVO word order in Speaker B's second utterance makes the sentence grammatical, as shown in the following example:

-

(20) Speaker B: ʕala fikrah ʕamm-i ʕazam ʔib-ʕamma:n kama:n

By the way uncle-my invite.pst.3sg.m in-Amman also

‘By the way, my uncle invited (the manager) [to meet him] in Amman as well.’

When the null object refers back to an element that is mentioned in the previous discourse, only SVO order is allowed. Therefore, we propose that not all null objects belong to the same category, something that should be investigated further. In this article, we limit analysis to instances of object drop whose licensing rests on discourse and the type of word order used (see Soltan Reference Soltan2020 for a syntactic analysis of a null object which is restricted to [-animate] and [-definite] elements).Footnote 4

We propose that the relation between the presence of an OG and the SVO vs. VSO word order pattern in JA grammar leans on the assumption that the subject and the object (in constructions with an OG, SVΔ) are located in discourse-related positions (Spec,Topic Phrase). The thematic subject is located in the CP zone, while the elided object is located in the so-called low IP area of the clause (cf. Belletti Reference Belletti and Rizzi2004, Reference Belletti2005). We argue that the ban on the use of an object gap (OG) in VSΔ clauses appears as a result of the movement of the topical object over the topical subject and its ensuing relativized-minimality effects (Rizzi Reference Rizzi and Haegeman1997, Reference Rizzi2004). The effects of these interactions on object drop are significant in two ways. Firstly, they show that object drop in JA is affected not only by its discourse status as a topic, but also by the discourse status of other arguments within the same clause (being topics or foci). We demonstrate that the object can drop in SVO clauses when the subject also functions as an (overt or covert) topic, situated in the CP zone of the clause. Additionally, the effects of the interactions between the subject and the object add credence to the proposal that natural languages subsume a discourse-related field between TP and vP (Belletti Reference Belletti and Rizzi2004, Reference Belletti2005; consider Jarrah and Abusalim Reference Jarrah and Abusalim2021 for evidence that JA subsumes this area in its grammar). Object drop in JA grammar therefore results from the interaction of two discourse fields located in two different positions within the sentence structure, namely above IP (Rizzi Reference Rizzi and Haegeman1997) and between TP and vP (Belletti Reference Belletti and Rizzi2004).

In the following section, we provide evidence that the object drop in SVO clauses is an instance of a dropped argument (i.e., an elided object) rather than VP ellipsis.

4. SVΔ are not derived by VP ellipsis

We propose that SVΔ in JA are not derived by VP ellipsis, which as Landau (Reference Landau2020) argues has been canonized in most studies of ellipsis (see Van Craenenbroeck and Lipták Reference Van Craenenbroeck, Lipták, Chang and Haynie2008, Van Craenenbroeck and Merchant Reference Van Craenenbroeck, Merchant and Dikken2013, Lipták Reference Lipták2015, Van Craenenbroeck Reference Van Craenenbroeck, Everaert and Riemsdijk2017, Merchant Reference Merchant, van Craenenbroeck and Temmerman2019). In other words, the object gap (OG) in SVΔ constructions is not derived by the movement of the lexical verb to T0, through v0, followed by ellipsis of the VP layer, which contains a copy of the raising verb and the object. We propose instead that the OG in SVΔ constructions is derived by simple object dropping. We use three tests to argue this position: the modified Park-Oku test, the non-availability of sloppy interpretations, and the presence of the remnant VP material in their canonical positions.

4.1. The modified Park-Oku test

The Park-Oku test (Park Reference Park1997 and Oku Reference Oku1998), as modified by Landau (Reference Landau2020), is argued to be one of the best tests to reveal whether a given construction involves a dropped argument or an elliptical VP projection is the inclusion/exclusion of adjuncts in the ellipsis site (Landau Reference Landau2020). Consider the following example from Landau (Reference Landau2020: 3):Footnote 5

(21)

a. He read the sign loudly, but I didn't read ------

b. He didn't read the sign loudly, but I read ------

If the gap in (21a) corresponds to a full VP, it can permit the inclusion of the adjunct loudly, which is present in the antecedent VP. So, sentence (21a) can be interpreted as ‘I read the sign but not loudly’. By contrast, if the gap in sentence (21a) corresponds to a bare argument (where only the object is dropped, rather than the whole VP), the interpretation of the target clause should be ‘I didn't read the sign’.

Landau argues that the Park-Oku test should be used with caution because the VP ellipsis-based account “does not have to produce a reading distinct from that of the AE [Argument Ellipsis] analysis” (Reference Landau2020: 4). He suggests that in order to sharpen the Park-Oku test, examples with creation verbs should be used as a diagnostic, arguing that the advantage in using such predicates in this test is that their object is subject to negation. Therefore, the subsequent reference to their object is perceived as anomalous. Landau (Reference Landau2020: 4) gives the following example:

(22) He baked a cake with baking powder, but I didn't bake ------. It came out flat.

Under the AE analysis, the gapped clause recovers as ‘I didn't bake a cake’. Given that my cake was never baked, the continuation ‘It came out flat’ should be perceived as anomalous. On the other hand, under the VP-Ellipsis-based account, the gapped clause is recovered as ‘I didn't bake a cake with baking powder’. Therefore, the continuation ‘It came out flat’ can be perceived as possible and natural.

Let us now apply the modified Park-Oku test (i.e., using creation verbs) on the relevant sentences in JA. The corresponding JA clause for (22) is given in (23).

(23) ha:ʃim tˁabax ke:k bi-l-be:kimk ba:wdar

Hashem cook.pst.3sg.m cake with-def-baking powder

bas balqi:s ma: tˁabx-at

but Balqi:s not cook.pst-3sg.f

tˁiliʕ xarba:n

turn out.pst.3sg.m ruined

Intended: ‘Hashem cooked a cake with baking powder, but Balqees did not cook, so it came out ruined.’

One hundred native speakers of JA were asked to judge whether the continuation tˁiliʕ xarba:n ‘it came out ruined’ is perceived as anomalous or natural within the context of the sentence. All native speakers judged the continuation as anomalous, in that they did not interpret it to mean that Balqees had not used baking powder when cooking the cake. For many of them, Balqees did not even cook at all. This judgment supports our hypothesis that the OG in SVΔ constructions in JA is derived by argument dropping rather than VP ellipsis, which predicts that the continuation tˁiliʕ xarba:n ‘it came out ruined’ should be perceived as possible.

The modified Park-Oku test is used for other creation verbs such as rasam ‘painted’, dʒammaʕ ‘constructed’, and bana ‘built’ in JA, as shown in the following example:

(24) ʔil-walad rasam/dʒammaʕ/bana: be:t zaɣi:r ʔibʕina:jeh

the-boy painted/constructed/built house small carefully

bas ʔil-binit ma: rasmat/dʒammaʕat/banat

but def-girl not painted/constructed/built

tˁiliʕ xarba:n

turn out.pst.3sg.m ruined

‘The boy painted/constructed/built a small house, but the girl did not paint/construct/build, so it came out ruined.’

Once again, the continuation was judged as anomalous.

All native speakers who were asked to judge the felicity of the continuation tˁiliʕ xarba:n ‘it came out ruined’ were also asked to judge the second part of the sentence (with and without the continuation tˁiliʕ xarba:n) with VSΔ word order rather than SVΔ word order. See the sentence in (25):

(25) tˁabax ha:ʃim ke:k bi-l-be:kimk ba:wdar

cook.pst.3sg.m Hashem cake with-def-baking powder

bas ma: tˁabx-at balqi:s.

but not cook.pst-3sg.f Balqees

(tˁiliʕ xarba:n)

(turn out.pst.3sg.m ruined)

‘Hashem cooked a cake with baking powder, but Balqees did not, so it was ruined.’

All native speakers found sentence (25) deviant despite the first part of the sentence also occurring with VSO word order. On the other hand, with an overt object, the sentence's grammaticality improves considerably:

(26) tˁabax ha:ʃim ke:k bi-l-be:kimk ba:wdar

cook.pst.3sg.m Hashem cake with-def-baking powder

bas ma: tˁabx-at balqi:s

but not cook.pst-3sg.f Balqees

ke:k bi-l-be:kimk ba:wdar

cake with-def-baking powder

‘Hashem cooked a cake with baking powder, but Balqees did not cook the cake with baking powder.’

The contrast between sentences (25)–(26) shows that an OG is licensed in SVO clauses, but not in VSO.

4.2. The non-availability of sloppy interpretations

The second piece of evidence that the OG in SVΔ constructions is derived by object drop rather than VP ellipsis is given by the fact that the OG in SVΔ constructions can yield a “strict” rather than “sloppy” reading (Hoji Reference Hoji1998, Kim Reference Kim1999, Johnson Reference Johnson, Baltin and Collins2001). This conclusion is based on the fact that variable binding displays restrictions in elliptical constructions that do not hold for cases of co-reference (Anagnostopoulou and Everaert Reference Anagnostopoulou and Everaert1999, Reference Anagnostopoulou and Everaert2013). In fact, this test (particularly the unavailability of sloppy readings) is normally formulated in various syntactic analyses of the OG as a diagnostic for the availability of argument ellipsis in languages including Japanese (Hoji Reference Hoji1998, Oku Reference Oku1998, Sakamoto Reference Sakamoto, Bui and Özyçldçz2015), Chinese (Takahashi Reference Takahashi2007), and Egyptian Arabic (Soltan Reference Soltan2020). For instance, the following sentence includes an example of OG in SVΔ constructions; the OG in the elided constituent must have the same reference as the first clause.

(27) Ɂil-mudi:r sa:ʕad ʕamm-uh Ɂimba:reħ

def-manager help.pst.3sg.m uncle-his yesterday

wu-ʕali sa:ʕad kama:n

and-Ali help.pst.3sg.m too

‘The manager helped his uncle yesterday, and Ali did too.’

The sentence in (27) can be felicitously interpreted only if the manager and Ali helped the same person, i.e., the manager's uncle. In other words, the referent of the elided object in the second clause must be the same as the referent of the object in the first clause. If (27) is derived by VP ellipsis, it would pass the usual sloppy identity test, whereby the object can be interpreted as having a different antecedent in the elided VP than it does in the overt VP. According to Hoji (Reference Hoji1998), the unavailability of sloppy readings constitutes evidence against the VP analysis.

4.3. The presence of the remnant VP material in their canonical positions

The third piece of evidence that SVΔ constructions involve object drop comes from the fact that SVΔ constructions may contain VP adjuncts and/or an indirect object (in case of dative SVΔ constructions). To see this, consider the following sentence:

(28)

a. Ɂimħammad wadda (masˁa:ri) la-Ɂumm-uh Ɂibsurʕa

Mohammad send.pst.3sg.m (money) to-mother-his quickly

‘Mohammad sent (the money) to his mother quickly.’

b. mudi:r Ɂil-madraseh Ɂaɡnaʕ (Ɂil-mawdʒu:di:n)

principal def-school persuade.pst.3sg.m (def-attendees)

Ɂib-sillam Ɂir-ra:tib Ɂil-dʒdi:d

with-structure def-salary def-new

‘The school principal persuaded (the attendees) with the new salary structure.’

Under the VP-ellipsis analysis, the sentences in (28) must have a number of unmotivated movements of all VP materials, including the movement of the dative complement laɁummuh ‘to his mother’ and VP adverbial Ɂibsurʕa ‘quickly’ in (28a) and the movement of the PP bisillam Ɂirra:tib Ɂilʒdi:d ‘with the new salary structure’ in (28b). These elements must leave the VP in order to escape VP ellipsis. By contrast, under object drop, such movements are not needed. The direct object is dropped, while other VP material remains in situ, as there is no elided constituent.

Having shown evidence against a VP ellipsis-derived account of SVΔ constructions, we now discuss the ban of an OG in VSO clauses. We propose that object drop should be treated as an instance of topic deletion, a syntactic operation that targets elements located in Spec, Topic Phrase.

5. The position of the thematic subject in SVΔ constructions

As mentioned in section 1, an OG is permitted in SVΔ constructions but not in VSO clauses, as shown in the following examples:

(29)

a. Ɂabu:-j ʕazam (Ɂin-na:s) ʕala ʕuris Ɂaħmad

father-my invite.pst.3sg.m (def-people) to wedding Ahmad

‘My father invited (the people) to Ahmad's wedding.’

b. *ʕazam Ɂabu:-j (Ɂin-na:s) ʕala ʕuris Ɂaħmad

invite.pst.3sg.m father-my (def-people) to wedding Ahmad

Intended: ‘My father invited (the people) to Ahmad's wedding.’

Importantly, the existence of an OG in SVΔ constructions is conditional. The clausemate subject should be a definite and/or specific entity, in the sense that it is already established in the previous discourse. The examples in (30)–(31) illustrate this phenomenon. The sentences in (30) are ungrammatical because the subject is an indefinite, non-specific element, whereas those in (31) are grammatical because the subject is a specific element. Note that (30a–b) remain degraded even if these sentences are changed to the present tense with a generic interpretation. This is important because it excludes the possibility that such sentences are ungrammatical due to the use of an indefinite, non-specific subject, which is incompatible with eventive clauses in general (Kratzer Reference Kratzer and Rothstein1998).

(30)

a. *mudi:r ʕazam (Ɂin-na:s) ʕala ʕuris Ɂaħmad

manager invite.pst.3sg.m (def-people) to wedding Ahmad

‘A manager invited (the people) to Ahmad's wedding.’

b. *zalameh bana: (Ɂil-be:t)

man build.pst.3sg.m def-house

Intended: ‘A man built (the house).’

(31)

c. mudi:r kbi:r ʕazam (Ɂin-na:s) ʕala ʕuris Ɂaħmad

manager senior invite.pst.3sg.m (def-people) to wedding Ahmad

‘A senior manager invited (people) to Ahmad's wedding.’

d. zalameh min Ɂitˁ-tˁafi:leh bana: (Ɂil-be:t)

man from def-Tafila build.pst.3sg.m (def-house)

’A man from Tafila built (the house).

The two examples in (30)–(31) indicate that the existence of an OG in SVΔ clauses is associated with the presence of a definite/specific subject.

Before exploring the relationship between a specific/definite subject and OG in SVΔ clauses, it should be mentioned that JA freely allows SVO sentences with an indefinite, non-specific subject, as seen in section 2. For example, Jarrah and Abusalim (Reference Jarrah and Abusalim2021) show that SVO word order is the predominant word order in JA, and that, unlike VSO clauses, SVO clauses place no restrictions on the form of the subject. Therefore, the subject in SVO clauses can be an indefinite or non-specific element (in the sense that it is not already introduced in the discourse or has no referent in the preceding discourse). The sentences in (32) are examples of SVO clauses with an indefinite or non-specific subject.

(32)

a. bint lag-at Ɂil-wla:d ʕind Ɂil-masdʒid

girl find.pst-3sg.f def-boy next to def-mosque

‘A girl found the boy next to the mosque.’

b. tˁa:lib Ɂallaf qasˁi:deh Ɂimrattabih ʕann Ɂil-ʕagabah

student write.pst.3sg.m poem great about def-Aqaba

‘A student wrote a great poem about Aqaba.’

c. mikani:ki: sˁallaħ Ɂis-sajja:rah ʕala Ɂitˁ-tˁari:ɡ

mechanic fix.pst.3sng.m def-car on def-road

‘A mechanic fixed the car on the road.’

The examples in (32) show that the ban on the use of an indefinite, non-specific subject in SVΔ constructions is not a common property of JA clause structure (as the subject can be an indefinite, non-specific element in sentences without object drop).

Following the related literature (especially on Arabic clause structure) that the element that occupies Spec,TP should not be of a specific type (i.e., a specific entity, an (in)definite entity, etc.) (Fehri Reference Fehri1993, Mohammad Reference Mohammad1999, Soltan Reference Soltan2007, Aoun et al. Reference Aoun, Benmamoun and Choueiri2010, Jarrah Reference Jarrah2019a; see also Alexiadou and Anagnostopoulou Reference Alexiadou and Anagnostopoulou1998 and Rizzi Reference Rizzi, Brugé, Giusti, Munaro, Schweikert and Turano2005), we propose that the preverbal subject in SVΔ constructions is not located in Spec,TP, unlike in SVO clauses. One significant piece of evidence that supports this view comes from the position of the subject relative to high IP adverbials. Cinque (Reference Cinque1999) argues for the existence of a fixed universal hierarchy of clausal functional projections (see Jlassi Reference Jlassi2013, Alshamari Reference Alshamari2017, Tescari Neto Reference Tescari Neto2022 for related discussion). For instance, evidential adverbials/adverbs are located in a functional projection, which is labelled as Moodevidential Phrase. This functional projection dominates, e.g., Modepistemic, which is a projection that contains epistemic adverbs such as ‘probably’. The universal hierarchy of clausal functional projections is introduced in (33) (adapted from Cinque Reference Cinque1999: 106).

(33)

According to Cinque's (Reference Cinque1999) hierarchy in (33), MoodPspeech act, MoodPevaluative, MoodPevidential, and Modepistemic all dominate TP. We can use the position of the thematic subject relative to the respective adverbials of these four categories to determine whether or not the subject is located in Spec,TP (i.e., the thematic subject appears to the right of these adverbials) or in a higher position, in which case the thematic subject appears to the left of these adverbials.

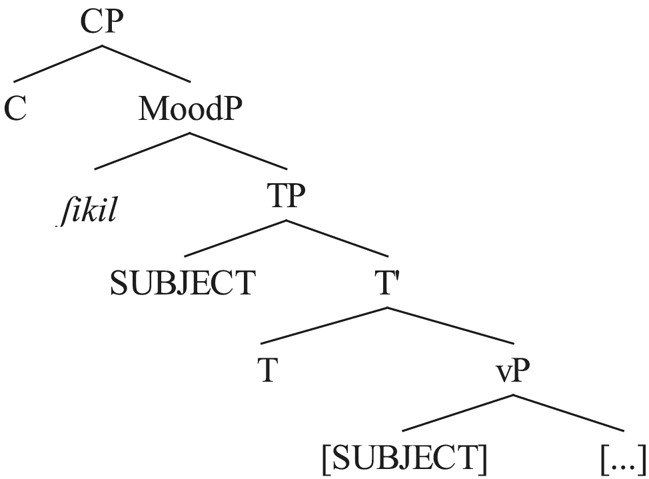

Jarrah and Alshamari (Reference Jarrah and Alshamari2017) argue that the particle ʃikil in JA is an evidentiality particle that heads MoodPevidential. They propose that ʃikil expresses the speaker's reliance on indirect evidence as the information source for his/her proposition. They show that ʃikil should appear to the left of all IP-related elements, including the subject, the verb, and the past tense copula ka:n (34a–b) and at the same time projects below (appears to the right of) all CP-related elements such as interrogative wh-words (34c–d) and topical elements (34e).

(34)

a. ʃikil-uh ʔil-muwazˤzˤaf ʔarsal ʔil-bari:d

prt-3sg.m def-employee sent.3sg.m def-mail

‘Evidently, the employee sent the mail.’

(Jarrah and Alshamari Reference Jarrah and Alshamari2017: 34)

b. ʃikil-uh ʔil-muwazˤzˤaf ka:n jirsil ʔil-bari:d

prt-3sg.m def-employee was sent.3sg.m def-mail

‘Evidently, the employee was sending the mail.’

(Jarrah and Alshamari Reference Jarrah and Alshamari2017: 34)

c. mi:n ʃikil-uh sarag ʔis-sijja:rah?

Who prt-3sg.m stole.3sg.m def-car

‘Who did evidently steal the car?’ (Jarrah and Alshamari Reference Jarrah and Alshamari2017: 37)

d. *ʃikil-uh mi:n sarag ʔis-sijja:rah?

prt-3sg.m who stole.3sg.m def-car

Intended: ‘Who did evidently steal the car?’

(Jarrah and Alshamari Reference Jarrah and Alshamari2017: 37)

e. ʔis-sijja:rah ʃikil-uh ʔiz-zalameh sarag-ha

def-car prt-3sg.m def-man watched.3sg.m-it

‘The car, the man evidently stole it.’ (Jarrah and Alshamari Reference Jarrah and Alshamari2017: 38)

The following tree structure shows the structural position of ʃikil, which is assumed to be an X0–element that projects MoodPEVIDENTIAL (MoodP).

-

(35)

We use the surface position of ʃikil relative to the position of the subject in SVΔ constructions to identify the structural position of the subject. In SVΔ sentences with the particle ʃikil, the subject should appear to the left of ʃikil. Consider the example in (36), where the argument understood to be the object is given in square brackets.

(36)

a. (*ʃikil-uh) Ɂiz-zalameh (ʃikil-uh) ʕazam

(prt-3sg.m) def-man (prt-3sg.m) invite.pst.3sg.m

ʕala ʕurs Ɂibn-uh

to wedding son-his

‘(*Evidently) the man (evidently) invited [the people] to his son's wedding (party).’

b. (*ʃikil-ha) Ɂumm-ij (ʃikil-ha) ɣassl-at

(prt-3sg.f) mother-my (prt-3sg.f) wash.pst-3sg.f

bidu:n musa:ʕadih

without help

‘(*Evidently) My mother (evidently) washed [the clothes] without help.’

The fact that the subject must appear to the left of the evidentiality particle ʃikil is evidence that the subject is not located in Spec,TP, but in a higher position that dominates MoodPevidential.

Note here that when the object is mentioned (not elided), ʃikil can appear either to the left or to the right of the subject, as illustrated by the examples in (37):

(37)

a. (ʃikil-uh) Ɂiz-zalameh (ʃikil-uh) ʕazam qara:jb-uh

(prt-3sg.m) def-man (prt-3sg.m) invite.pst.3sg.m relatives-his

ʕala ʕurs Ɂibn-uh

to wedding son-his

‘(Evidently) the man (evidently) invited his relatives to his son's wedding.’

b. (ʃikil-ha) Ɂumm-ij (ʃikil-ha) ɣassl-at Ɂisˁ-sˁħu:n

(prt-3sg.f) mother-my (prt-3sg.f) wash.pst-3sg.f def-dishes

bidu:n musa:ʕadeh

without help

‘(Evidently) my mother (evidently) washed the dishes without help.’

The contrast between (36) and (37) indicates that the subject occupies a different structural position in SVΔ constructions than in SVO clauses.

We propose that the subject in SVΔ constructions serves as a topic, located in CP. (We follow the assumption that when the subject is a topic in the left periphery, Spec,vP is to be filled with a non-expletive pro (Soltan Reference Soltan2007), referring to the same entity as the topical subject.)Footnote 6 The tree in (39) is a schematic representation of the sentence in (38).

(38) Ɂumm-ij ʃikil-ha ɣassl-at (Ɂisˁ-sˁħu:n)

mother-my prt-3sg.f wash.pst-3sg.f def-dishes

‘My mother evidently washed (the dishes).’

(39)

This proposal is consistent with the informational constraint that the subject should be a definite or specific entity, imposed on the form of the subject in SVΔ. In other words, what appears as the subject in SVΔ constructions is not a true subject occupying Spec,TP, but rather a topic located in the CP domain of the clause. According to Rizzi (Reference Rizzi, Brugé, Giusti, Munaro, Schweikert and Turano2005), indefinite, non-specific entities cannot be used as topics because they do not refer to the entities around which the sentence revolves or the salient element of the sentence's accompanying discourse. Chafe (Reference Chafe and Tomlin1987) argues that a topic is a given or accessible constituent, typically destressed and realized in a pronominal form (see also Reinhart Reference Reinhart1981, Givón Reference Givón1983, Pesetsky Reference Pesetsky, Reuland and Ter Meulen1987, Lambrecht Reference Lambrecht1994). Following this line of analysis, we can now account for the structural position of the subject in SVΔ constructions relative to the marker ʃikil. As the head of MoodPevidential (Jarrah and Alshamari Reference Jarrah and Alshamari2017), ʃikil should appear to the left of all material, dominated by MoodP projecting above TP. On the other hand, ʃikil should appear to the right of all CP material (cf. Cinque Reference Cinque1999). The subject in SVΔ constructions is a topic; therefore, ʃikil should occur to the right of the subject. On the other hand, the thematic subject in non-SVΔ constructions stays in Spec,TP; hence it can appear to the left of ʃikil. Note here that when the subject of SVO clauses (without an OG) is a topic, it appears to the left of ʃikil. This proposal accounts for the linear positions of the subject to the left and to the right of ʃikil in non-SVΔ constructions.

An anonymous reviewer points out that if the dropped object is understood to be an indefinite entity, the sentence is fine both ways (the subject before the evidential marker or after it), as shown in the following sentence:

(40) Ɂiz-zalameh ʕazam na:s ʕala ʕurs Ɂibn-uh,

def-man invite.pst.3sg.m people to wedding son-his

(w-ʃikil-uh) Ɂil-mudi:r (ʃikil-uh) ʕazam

and-prt-3sg.m def-manager and-prt-3sg.m invite.pst.3sg.m

ʕurs bint-uh

wedding daughter-his

‘The man invited people to his son's wedding and the manager invited [people] to his daughter's wedding.’

We agree that the subject in such cases can appear to the left and to the right of the evidentiality marker ʃikil. However, as mentioned, the dropped object in sentences like (40) may not be perceived as a topic, so there are no restrictions on the use of the evidentiality marker relative to the subject, which can also be either a topic or a true subject.

Given this evidence, we argue that the subject in SVΔ sentences is located in the CP zone of the clause (in Spec,TP). One important point to mention here relates to the widely held assumption that the topical subject is externally merged in its surface position in Arabic clause structure (Soltan Reference Soltan2007; see also Fehri Reference Fehri1993, Ouhalla Reference Ouhalla, Eid and Ratcliffe1997, Shlonsky Reference Shlonsky1997, Mohammad Reference Mohammad2000, Soltan Reference Soltan2007, Aoun et al. Reference Aoun, Benmamoun and Choueiri2010, Albuhayri Reference Albuhayri2019, Jarrah Reference Jarrah2019b). The subject in SVΔ sentences is therefore not base-generated in Spec,vP, which is filled with a pro which shares the same φ-features of the dislocated subject. According to Soltan (Reference Soltan2007), the pro in Spec,vP refers to the same referent of the topical subject. Evidence that supports this line of analysis comes from the fact that the subject in SVΔ constructions can be dropped:

(41)

a. wadda (masˁa:ri) la-Ɂumm-u Ɂibsurʕa

give-pst.3sg.m (money) to-mother-his quickly

‘He gave his mother (the money) quickly.’

b. Ɂaqnaʕit (Ɂil-mawdʒu:di:n) bi-sillam Ɂir-ra:tib Ɂil-dʒi:d

persuade.pst.3sg.m (def-attendees) with-structure salary def-new

‘She persuaded (the attendees) with the new salary structure.’

The φ-content of the dropped subject can be identified by virtue of the inflectional marker that is attached to lexical verb bears. For instance, in (41b), the subject is identified as a [3sg.f] entity by virtue of the inflectional marker borne by the lexical verb.

In the next section, we address the relation between the topicality of the subject and the presence of an OG in SVΔ constructions.

6. The object in SVΔ constructions

Our account of SVΔ constructions is primarily based on the assumption that the object in SVΔ constructions functions as a topic situated in the low IP area (Belletti Reference Belletti and Rizzi2004, Reference Belletti2005). According to Belletti (Reference Belletti and Rizzi2004, Reference Belletti2005), the clause structure of natural languages subsumes a discourse-related area that projects between TP and vP. Belletti calls this area the low IP area, which is argued to be equivalent to, but distinct from, the left periphery of the clause (as proposed by Rizzi Reference Rizzi and Haegeman1997). Therefore, the low IP area has functional layers of Topic Phrase and Focus Phrase. Consider the following tree diagram that shows the schematic of Belletti's (Reference Belletti and Rizzi2004, Reference Belletti2005) proposal of the low IP area.

(42)

Evidence from languages whose low IP area has been examined indicates that the low IP projections are limited to a specific type of information, unlike the corresponding projections of CP. For instance, the low IP area is shown to be restricted to contrastive/corrective focus (but not information focus; cf. Kiss Reference Kiss1998) in English and Malayalam (Jayaseelan Reference Jayaseelan2008). Jarrah and Abusalim (Reference Jarrah and Abusalim2021) propose that low topics in JA require a high degree of contextual anaphoricity, so they cannot function as Aboutness or Shifting Topics.Footnote 7 The assumption that the dropped object in SVΔ is a low topic is plausible because speakers found the OG in SVΔ constructions grammatical when the relevant SVΔ constructions was accompanied by a felicitous context which included a mention of the referent of the elided object (see section 3.3).

Another important difference between low topics and high topics in JA rests on the assumption that the former are derived entities (a result of some movement), while the latter are base-generated in their surface position area (Jarrah and Abu Salem Reference Jarrah and Abusalim2021). This view is supported by the fact that low topics are not associated with a resumptive clitic on the lexical verb. To illustrate, consider the following examples:

(43)

a. Ɂis-sajja:rah nasi:b-ij Ɂiʃtara:-ha:

def-car brother-in-law-my buy.pst.3sg.m-it

‘The car, my brother-in-law bought it.’

b. Ɂiʃtara: Ɂis-sajja:rah nasi:b-i j

buy.pst.3sg.m def-car brother-in-law-my

‘The car, my brother-in-law bought.’

The object in (43a) Ɂis-sajja:rah ‘the car’ is analyzed as a dislocated element, which is base-generated in the CP zone of the clause. The structural position of the thematic object is filled with a resumptive clitic that absorbs the structural case on the verb (Shlonsky Reference Shlonsky1997, Soltan Reference Soltan2007). Consider the schematic representation of sentence (43a) in (44).

(44)

On the other hand, the object Ɂis-sajja:rah ‘the car’ in (44b) is analyzed as a low element, generated in the thematic position of the object, and then moved to the low IP area. This account explains why the low topic element in (44b) is associated with a gap rather than a resumptive clitic on the verb. Consider the schematic of sentence (43a) in (45).Footnote 8

(45)

Following this line of analysis, we propose that the OG in SVΔ constructions is occupied by an object topic, which leaves its base-position (as a complement of VP) to Spec,Topic Phrase in the topic position of the low IP area. Being situated in Spec,Topic Phrase of the low IP area, the object can drop. Consider the proposed derivation of sentence (1a), which is reproduced here for convenience (the tree is set for the version of the sentence with a dropped object) (irrelevant details are skipped):

(46) ʔiz-zalameh ɣassal (ʔil-ʔawa:ʕi)

def-man wash.pst.3sg.m (def-clothes)

‘The man washed (the clothes).’

(47)

We propose that topic deletion in JA grammar is only licensed when the topical element is located in the specifier position of Topic Phrase. This is not surprising, because elements that target Topic Phrase express accessible and salient information, which can be retrieved from the previous context. These properties of topical elements make them subject to the ellipsis operation that targets accessible elements in the sentence. In other words, the existence of an OG in JA grammar is dependent on the information status of the object. If the object expresses old information, it can target Spec,Topic Phrase, where it can drop. Our assumption that topical elements can drop when they reach Spec,Topic Phrase is based on the notion that the [topic] feature is a criterial feature that requires a configuration in which a head shares a major interpretable feature with its specifier for interpretation (Rizzi Reference Rizzi, Cheng and Corver2006). According to this approach, an element that carries the [topic] feature should move to the specifier position of Topic Phrase in order to be interpreted at the interface. Given that elements carrying the [topic] feature express salient information, we propose that they can be dropped at the interface once their interpretation is complete (see Frascarelli Reference Frascarelli2007 for more on the relation between the discourse properties of Topic constituents and their dropping at the interface).

Before addressing the question of the ban on the use of OG in VSO constructions, we explore the derivation of VSO clauses in JA. The syntactic derivation of these clauses in JA grammar is examined in depth by Jarrah and Abusalim (Reference Jarrah and Abusalim2021), who show that VSO clauses in JA are syntactically derived through the movement of the postverbal subject to the specifier position of Topic Phrase or Focus Phrase of the low IP area. The evidence for their account of SVO clauses comes from a two-million-word corpus of naturally occurring data from JA, supported by grammaticality judgments from 50 JA speakers. Jarrah and Abusalim (Reference Jarrah and Abusalim2021) found that the subjects in this corpus of JA are mostly a definite DP or a modified, indefinite DP, implying that a particular discourse-related interpretation (i.e., a topic or a focus) is associated with the post-verbal subject in VSO clauses. The presence of such an interpretation can account for the constraints on the form of the subject in VSO clauses (e.g., the subject cannot be an indefinite, non-specific entity). Additionally, Jarrah and Abusalim (Reference Jarrah and Abusalim2021) found that the subject in VSO clauses should occur to the right of the past tense copula ka:n ‘was’ (that fills T0), but to the left of high vP adverbials. Such distributional properties of the subject in VSO clauses demonstrate that the subject does not stay in Spec,vP whose lexical filler should appear to the right of high vP adverbials. These pieces of evidence support the assumption that the subject in VSO clauses moves to a structural position higher than vP adverbials, yet lower than T0. Jarrah and Abusalim (Reference Jarrah and Abusalim2021) propose that the subject in VSO clauses targets a structural position in the VP periphery of the clause structure. This area contains a number of projections with a discourse-related nature, which can be topics or foci. As mentioned above, Belletti (Reference Belletti and Rizzi2004, Reference Belletti2005) proposes that the VP shares a periphery resembling the clause-external CP left periphery. Following this, Jarrah and Abusalim (Reference Jarrah and Abusalim2021) propose that the subject in VSO clauses moves to the low IP area.Footnote 9 The derivation of a VSO clause like that of the sentence in (48) is schematically represented in (49):

(48) ɣassal ʔiz-zalameh ʔil-ʔawa:ʕi

wash.PST.3SG.M DEF-man DEF-clothes

‘The man washed the clothes.’

(49)

With this framework in mind, we can propose an account of the reason for the lack of OG in VSO sentences: the subject fills the VP peripheral topic position and has a topic-like interpretation. When the object also has a topic-like interpretation (bearing the [topic] feature), it cannot move to the low IP area because it is intercepted by the presence of the topical subject, due to relativized minimality (cf. Rizzi Reference Rizzi1990, Reference Rizzi2004). This proposal is schematically illustrated in (50):

(50)

Note that the object must first move to the edge of the v*P phase due to the effects of the Phase Impenetrability Condition (Chomsky Reference Chomsky and Kenstowicz2001), which disallows elements to escape from their containing phases unless they move first to the edge of the phase. However, the movement of the topical object to the edge of the vP phase and then to the low IP area does not take place because of the presence of the topical subject (or its silent copy) in Spec,vP. We propose that there is no OG in VSO clauses because the topical object cannot target Spec,Topic Phrase of the low IP area, which, according to our proposal, is the place where elided elements can be licensed in JA grammar.

As for SVΔ constructions, we propose that the OG in such constructions is possible because the thematic (topical) subject is not base-originated in Spec,vP. As discussed in section 5, the standard analysis of SVO clauses where the subject is a topic in Arabic generative grammar is that the subject is base-generated in the CP, whereas its thematic position is filled with a pro. We suggest that the pro in Spec,vP does not trigger an intervention effect against the movement of the topical object to the low IP because the subject pro (in Spec,vP) does not necessarily have a topic feature. Evidence for this comes primarily from sentences including a pro that does not refer to an already-established element in the relevant discourse. Consider the following example, seen in a news headline:

(51) ðabaħ dʒa:r-uh ʕalaʃa:n masˤaf sijja:rah

kill.pst-3sg.m neighbour-his for parking car

‘(He) killed his neighbour for the parking spot.’

In sentence (51), the subject pro is used despite the fact that no previous discourse is mentioned. The pro subject is understood to refer to a [3sg.m] entity whose identity is not revealed.

The exchange in (52) also provides evidence that the subject pro may not be established in the previous discourse; it is used as an answer to a what's-up question that presupposes no previous discourse:

(52) ʃu: sˤa:jir

what happening

‘What is happening?’

ma: raħ ʔizi:du ʔir-rawa:tib

not will raise-ipfv-3pl.m def-wages

‘They will not raise the wages.’

We take this as evidence that not every instance of a pro requires a topic feature.

An anonymous reviewer questions whether the object can drop in ka:n-topic-verb-object sentences. In fact, according to our judgment and that of our participants, an object cannot be dropped in ka:n-topic-verb-object, as shown in the following sentences:

(53) ka:n mudi:r ʔil-midraseh ʔiwaɡɡiʕ

was principal def-school sign.ipfv.3sg.m

*(ʔil-kuʃu:f) ʔisˤsubuħ

def-reports morning

‘The school principal was signing the reports in the morning.’

The observation that the object cannot drop in this type of clause is expected, as the subject in such cases is assumed to be a topic (see Jarrah and Abusalim Reference Jarrah and Abusalim2021); therefore, the subject prevents the topical object from going to the left periphery.

On the other hand, when the subject in ka:n-subject-verb-object sentences is a focus, the object can drop, as shown in the following sentence:

(54) ka:n mudi:r ʔil-midraseh muʃ ʔil-murʃid

was principal def-school not def-counselor

ʔiwaɡɡiʕ (ʔil-kuʃu:f) ʔisˤsubuħ

sign.ipfv.3sg.m def-reports morning

‘The school principal, not the counselor, was signing (the reports) in the morning.’

Given the fact that the subject is a corrective focus in (54), the object can escape the effects of the subject, moving to the low IP area. This is because the subject bears a [focus] feature, whereas the object bears the [topic] feature. We take this as evidence that focus and topic are distinct and do not cause defective intervention effects in JA grammar.

7. Conclusion

We have provided a syntactic account of the observation that in JA, the object can drop without being resumed by a clitic on the verb in SVΔ clauses but not in VSO clauses. We have proposed that this observation can be explained in terms of the featural (and hence informational) content of the subject and the object as well as a proposed principle that elements can be elided once they reach Spec,Topic Phrase. In SVO clauses, the object can reach the Spec,Topic Phrase of the low IP area, non-intercepted by the pro that fills Spec,vP. The thematic subject in SVO clauses is a CP element that does not interfere in the movement of the topical object to the low IP area. On the other hand, the object cannot be dropped in VSO clauses because it cannot reach the low Topic position due to the interference of the topical subject, following relativized minimality. In other words, the object is forced to remain in situ because the subject has the [topic] feature and is located in Spec,vP, causing an intervention effect against the movement of any element that bears a similar feature, and blocking ellipsis. On these grounds, we provide new evidence for the strength of intervention effects in JA grammar supporting an analysis for JA where low topics are derived, and CP peripheral topics are externally merged in their surface position.

Acknowledgements

Our sincere gratitude goes to three anonymous reviewers for their constructive criticism and suggestions. We would also like to thank the audience at Cambridge Comparative Syntax (CamCosS 9) and the 55th Annual Meeting of the Societas Linguistica Europaea (both in 2022), where an early version of this paper was presented. Their discussions of some data and issues mentioned in this article were helpful and stimulating. Additionally, we would like to thank all of our JA participants and Murdhy Alshamari for judgments of Najdi Arabic sentences provided here.