Introduction

The last decade has seen a marked increase in social scientific and public interest in populism. Since 2016, the year that saw Donald Trump elected president of the United States and Britain exit the European Union (Brexit), the number of publications including the terms “populism(s)” or “populist(s)” in their titles has virtually exploded, as have worldwide Google searches of the term “populism” (Peker et al., Reference Peker, Rémi and Laxer2023). Current scholarly investigations of populism are disproportionately informed by observations of right-wing populist movements in Europe, which are known to elicit public fears about the cultural influence of foreign and domestic “others.” This has left a clear imprint on the field, leading many to define populism as inherently prone to the exclusion of minority populations (for example, Engesser et al., Reference Engesser, Ernst, Esser and Büchel2017), while others treat nativism as particular to “thick” (Jagers and Walgrave, Reference Jagers and Stefaan2007) or right-wing populisms (Friesen, Reference Friesen2021).

In this study, we aim to ascertain whether and to what extent theoretical propositions derived from the European experience can illuminate the role and impact of populisms in non-European contexts. We focus on Canada, which, until recently, was widely viewed as impervious to the global populist surge, particularly its nativist dimensions. However, this literature of “exceptionalism” has become overshadowed by reports that parties, leaders and movements deploying populist discourses and strategies have taken on greater significance and visibility in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. At the federal level, the right-wing People’s Party of Canada (PPC) improved its vote share in the 2021 election (but failed to win a seat in Parliament) based on a campaign to end COVID-19 restrictions, as well as reduce immigration and scrap multiculturalism (CBC News, Reference News2021). Pandemic-related frustrations also helped secure Pierre Poilievre’s bid to lead the Conservative Party of Canada in 2022. A vocal supporter of the Freedom Convoy—the anti-mandate blockades that paralyzed the city of Ottawa for three weeks in 2022—Poilievre has gained popularity through a campaign that frames the federal Liberals, and former Prime Minister Trudeau in particular, as “gatekeepers” who prioritize their private interests over those of the “people” (Peker et al., Reference Peker, Laxer and Vivès2024). Populism’s significance is also evident at the provincial level, where it has been identified as a factor in resurrecting the Parti conservateur du Québec (Drouin and Giasson, Reference Drouin and Giasson2024; Peker and Winter, Reference Peker and Winter2024) and in legislative efforts to “shield” provinces from federal law, as in the case of the Alberta Sovereignty within a United Canada Act (McLean and Laxer, Reference McLean and Laxer2023).

To what extent does political discourse in this shifting landscape adhere to theoretical expectations about populism, particularly those regarding its relationship to party ideology and nativism? To answer this question, we apply quantitative techniques to a dataset of over 5,845 original tweets posted by the leaders of six federal political parties on X (formerly Twitter) between January 1 and December 31, 2022: Justin Trudeau (Liberal Party of Canada), Jagmeet Singh (New Democratic Party), Pierre Poilievre (Conservative Party of Canada), Yves-François Blanchet (Bloc Québécois), Maxime Bernier (PPC) and Elizabeth May (Green Party of Canada). Our decision to include politicians from across the political spectrum is informed by a conception of populism as a communication style (Jagers and Walgrave Reference Jagers and Stefaan2007; Moffitt, Reference Moffitt2016), which varies in degree both within and across parties, and which contains multiple dimensions, some of which are strategically adopted by “mainstream” parties (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Mondon and Winter2021). In including politicians from a range of ideological traditions, we also sought to avoid presuming who is or is not “populist,” opting instead to focus on instances of populist mobilizing, which can take varied forms (Diehl, Reference Diehl2022). We chose tweets as our units of analysis because they are a significant tool of political mobilization, which provide insight into politicians’ relatively unmediated interactions with the public and, as such, can illuminate the content and tone of populist communication (Drouin and Giasson, Reference Drouin and Giasson2024; Engesser et al., Reference Engesser, Ernst, Esser and Büchel2017; Ernst et al., Reference Ernst, Sina Blassnig, Büchel and Esser2019; Maurer and Diehl, Reference Maurer and Diehl2020). Our methodology is an adaptation of the approach used by Jagers and Walgrave (Reference Jagers and Stefaan2007), a foundational article which uses data from parties’ political broadcasts to quantify the prevalence of three characteristically populist discourses—people-centrism, anti-elitism and exclusivity (which we refer to as “exclusion of others”)—in the Belgian political system.

Our results both confirm and depart from existing research on populism as a communication style. Like others (for example, March, Reference March2017), we find that people-centrism is widespread across the political spectrum, leading us to question its value in operationalizing populism as a specific political phenomenon. As Margaret Canovan (Reference Canovan, Mény and Surel2002) has argued, a minimal understanding of populism—defined by the use of political rhetoric centered on the people—can be expected to be found in all political parties and actors in democratic regimes, given their emphasis on popular sovereignty. Our finding concerning people-centrism confirms this notion via analysis of the Canadian political scene. Our results also bring concrete evidence to bear on the Canadian exceptionalism literature, by confirming that federal politicians predominantly avoid the explicit exclusion of others. More unexpectedly, we show that, despite their ideological differences, the leaders of nongoverning partiesFootnote 1 in Canada have converged around a strategy of foregrounding threats to the people’s economic well-being while primarily blaming political elites for those threats. Although we cannot confirm this using our data, this convergence could conceivably reflect the unique social and political context surrounding Canadian politics in 2022. With COVID-19 in full-swing, this was a year marked by widespread economic dislocation and uncertainty in Canadian households as well as increased government intervention via pandemic-related restrictions and financial policies. Although their precise framing strategies differed, all leaders outside the governing Liberal Party may have adapted to this context by harnessing voters’ economic frustrations and channeling them into distrust of sitting governmental elites.

We begin by situating our study within larger theoretical debates about populism, including those addressing its relationship to party ideology and the role of nativism. We then address the Canadian exceptionalism literature and explain why Canada is a useful test case in assessing the validity and reliability of hypotheses derived from observation of European populisms. The third section details our methodology and outlines key hypotheses. Our main findings are discussed in the results section, followed by conclusions highlighting broader theoretical implications.

Populism: Key Dimensions and Debates

Definitions of populism, and identification of its key dimensions, are nearly as varied as the phenomenon itself. Indeed, scholars have variously described populism as a category of political party or movement, as a distinct ideology, as a political or organizational strategy, as a characteristic of leaders or leadership styles, and as a type of political communication or performance (Diehl, Reference Diehl2022). From among these many vantage points, three principal approaches have prevailed.

A first approach sees populism as a “thin-centered” ideology consisting of two main claims: that the interests of a pure and disadvantaged people are confronted by those of an illegitimate and corrupt elite, and that “politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people” (Mudde, Reference Mudde2004: 543). While it proclaims to share democracy’s emphasis on popular power, populism as a thin-centered ideology often threatens the democratic process by equating the people’s will with the will of the majority. However, populism’s precise democratic implications differ depending on the thick ideological constructs with which it is paired. Right-wing populisms are presumed to be especially susceptible to majoritarianism, because of the additional emphasis they place on threats posed by domestic or foreign others (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2018). This expectation is borne out by studies of European party competition, which find that a large proportion of right-wing parties—such as the Rassemblement National (RN, previously the Front National) in France, the Alternative for Germany (AfD), and the UK Independence Party (U.K.I.P.) to name a few examples—exhibit high scores on the “authoritarianism” index and display a propensity toward anti-immigrant, ultra-nationalist and eurosceptic stances (Norris, Reference Norris2019).

A second approach conceives populism as an organizational strategy marked by an anti-establishment orientation and tendency to reject intermediate bodies and representative institutions, including existing parties and party systems, to forge direct, unmediated relationships with the people (Weyland Reference Weyland2001; Reference Weyland, Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017). When in office, leaders informed by a populist organizational strategy face dilemmas squaring this organizational orientation with their own institutionalization, which they often do by centering power in the executive and delegitimating other branches of the state, including the judiciary (Blokker, Reference Blokker2019). Although this approach is deeply rooted in the study of Latin American populisms (Barr, Reference Barr2019), it has been applied to other geographies. For instance, a key example in Europe can be found in Hungary, where Orban’s government drew on populist discourses to justify revising the constitution in ways that erode meaningful checks on the power of the executive (Bugaric and Kuhelj, Reference Bugaric and Kuhelj2018).

In this study, we subscribe to a third approach, treating populism as a communication style, which manifests in attempts to gain resonance through performative appeals to voters and other audiences (Jagers and Walgrave, Reference Jagers and Stefaan2007; Moffitt and Tormey, Reference Moffitt and Tormey2014). Although the nature of these appeals differs across cases, common features include the abundant use of frames that mobilize the people against the elites, expressions of “bad manners,” simplified explanations of complex phenomena, references to “us versus them,” promotion of “common sense” against expert knowledge and use of emotional or aggressive language (Moffitt, Reference Moffitt2016; Diehl, Reference Diehl2022).

Although presented as an alternative to the ideological approach, operationalizing populism as a communication style also builds, at least partially, on definitional dimensions offered by the literature on populism as a thin-centered ideology (Aslanidis, Reference Aslanidis2016: 92–93). These strategies vary, but a common approach is to focus on three key discourses: people-centrism, which consists of positive references to a people; “anti-elitism,” which highlights vertical discrepancies in the power of the people versus political, economic or cultural elites; and exclusivity, which highlights differences on a horizontal plane, distinguishing the people from the variously defined foreign and domestic others (Brubaker, Reference Brubaker2020; Jagers and Walgrave, Reference Jagers and Stefaan2007; Meijers and Zaslove, Reference Meijers and Zaslove2021; Zulianello et al., Reference Zulianello, Albertini and Ceccobelli2018).

Because it focuses on the contingent and shifting nature of political discourse, the stylistic approach to populism is less susceptible than competing perspectives to categorical uses of “populist” to label and typologize political leaders, parties and movements. The ideological approach is especially prone to such categorization “since it presupposes a ‘core’ of attributes which are ‘necessary and sufficient’ to delineate the concept” (Diehl, Reference Diehl2022: 21; see also Aslanidis, Reference Aslanidis2016: 92, 101). While they may have their own merits, these categorical distinctions among “populists” and “non-populists” are ineffective in recognizing that individual politicians—including those who are not traditionally considered populist (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Mondon and Winter2021)—may regularly deploy populist frames in a manner that is unstable and dependent on the political environment (Fahey, Reference Fahey2021). These findings underscore the advantages of theorizing populism not as a characteristic of parties, leaders and movements, but rather as a way of “doing politics” that varies by degree (Diehl, Reference Diehl2022; Meijers and Zaslove, Reference Meijers and Zaslove2021).

Despite appeals to avoid categorical treatments of populism, however, research remains susceptible to generalizing claims about what differentiates the populist style deployed by right- versus left-wing parties. In this regard, comparisons of European and Latin American cases have been influential. Based on systematic comparison of party-political populisms in Austria and France versus Bolivia and Venezuela, Mudde and Kaltwasser (Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2013) reached a generalized conclusion: in Europe, a relatively high degree of economic development has enabled (primarily right-wing) politicians to foreground post-materialist issues of identity, resulting in discourses of exclusion, while in Latin America, economic disparity and poverty have resulted in primarily materialist manifestations of populism, with (primarily left-wing) parties mobilizing “inclusive” discourses to promote socio-economic redistribution. This continental comparison informs the general hypothesis that left-wing populist repertoires promote a dyadic antagonism among the people and elite, whereas right-wing populism is triadic and also includes attacks on others (March, Reference March2017: 284–85).

The kinds of people and elite imagined by right and left populisms are also presumed to differ. In most European scholarship, right-wing populism is characterized as focusing on the cultural threat of immigration and its implications for national sovereignty (Berezin, Reference Berezin2009; Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2005). The people in this formulation are an ethnic or cultural group denied access to the collective goods of the state by both minority others—who siphon resources and recognition—and elites—who support liberal (often secular) ideas that erode the cultural traditions of the majority. Left-wing populisms, on the other hand, are presumed to be primarily concerned with rectifying economic inequality. They portray the people as having been denied economic resources by primarily corporate elites responsible for free trade, globalization and Western imperialism (Bonikowski et al., Reference Bonikowski, Daphe Halikiopoulou and Rooduijn2019: 67).

Empirical studies of populism in Europe broadly support these hypotheses, revealing that right-wing politicians are more likely to target political elites and the media, while those on the left more often target corporate elites (Maurer and Diehl, Reference Maurer and Diehl2020). They further confirm that right-wing politicians are more likely to discuss, and exhibit negative sentiments about, immigration (Berezin, Reference Berezin2009; Maurer and Diehl, Reference Maurer and Diehl2020; Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2005), whereas parties that deploy populism in the service of left-wing ideological projects are more likely to adopt pluralistic definitions of the people (Meijers and Zaslove, Reference Meijers and Zaslove2021).

Observations of European cases thus render a series of expectations about populism’s key dimensions and relationship to ideology. First, right-wing politicians deploying people-centrism as a discursive style are expected to define the people in cultural terms, whereas their left-wing counterparts will address the people in primarily economic terms. Second, there is an expectation that right-wing parties engaged in anti-elitism will primarily target political and cultural elites, whereas left-wing parties will focus their criticisms on economic or corporate elites. Third, the European literature renders the expectation that exclusion of others is a built-in feature of right-wing populisms, whereas left-wing politicians will avoid this tendency in favour of a more inclusive discursive style.

There are several reasons to question the validity and reliability of these expectations. Parties and leaders deploying populist ideas, strategies and/or styles are often ambiguous about what they plan to do, making their expressed ideologies less predictive of their policy decisions once in office. Relatedly, parties classified as populist in the literature often strategically eschew left-right ideological boxes, in favour of grand narratives capable of attracting an array of constituencies (Norris, Reference Norris2019: 985). How generalizable, then, are expectations of right- versus left-wing populisms derived from the study of European cases? To what extent do observations of European populisms serve as a useful blueprint for conceptualizing and operationalizing populist political performances elsewhere?

In proposing to tackle these questions via an examination of politicians’ social media activity in Canada, our study contributes to research investigating the role of shifting digital landscapes in the rise of populism. Since the early days of the internet, scholars have predicted novel opportunities and challenges for democratic participation and debate (Bimber, Reference Bimber1998). In the political scene, studies have found that social media might contribute to a tendency towards the personalization of politics, where charismatic leadership is emphasized (Kriesi, Reference Kriesi2014; Zamir, Reference Zamir2024). Moreover, works on political communication analyzed the specificities of the populist phenomenon in the age of information technologies, scrutinized through concepts such as “social media populism” (Bobba, Reference Bobba2019), “populism 2.0” (Momoc, Reference Momoc2018) or “digital populism” (Bartlett et al., Reference Bartlett, Birdwell and Littler2011), among others. However they may define and operationalize populism, contemporary examinations of the phenomenon increasingly make use of the digital rhetoric and performances of politicians and parties to assess their populist tendencies. Analyzing the online discourses of Canada’s federal leaders through the lens of populism, our article joins this burgeoning research field.

Canadian Populisms: Still the Exception?

At the same time as the election of Donald Trump and victory of the “Brexit” campaign were drawing worldwide attention as examples of rising populism in 2016, Canada was being touted as an exception to populism’s surge. Indeed, as suggested by a 2016 Economist article entitled “The last liberals: Why Canada is still at ease with openness,” Canada was being praised as a stalwart of openness and inclusion in an era evidently marked by rising closure and exclusion (The Economist, 2016). Yet, historical evidence shows that populism has long been, and continues to be, a key feature in Canadian political culture, particularly at the regional level. In Alberta, for instance, populism has been a prominent vehicle for articulating “Western alienation” and demanding autonomy from the federal government (Wesley, Reference Wesley2011). In Saskatchewan, a stronger emphasis on collectivism has led populism to be, until recently, mainly a tool of the left, particularly the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation and its successor, the New Democratic Party (Wesley, Reference Wesley2011). The term “populist” has also been used to describe the rhetoric advanced by the Doug Ford government in Ontario (Budd, Reference Budd2020), to diagnose changes in Québec’s nationalist project (Tanguay, Reference Tanguay, Guillaume Dufour and Peker2023), and to describe the strategic efforts of pro-Anglophone parties and movements in New Brunswick (Chouinard and Gordon, Reference Chouinard, Gordon and Boily2021).

While certainly present in Canadian politics, there is an expectation that populism in Canada is less likely to feature nativist characterizations of the people for reasons tied to both demand and supply. On the demand side, desire for nativist populism is expected to be tempered by Canadians’ relatively strong and stable popular support for large-scale immigration, even in periods of relatively high unemployment (Ambrose and Mudde, Reference Ambrose and Mudde2015). Although the consensus around immigration has recently shown signs of fraying (Lundy, Reference Lundy2023), it was for many years bolstered by the emphasis on skills in Canada’s immigration system. Perhaps more important to Canadian exceptionalism, though, are the obstacles to populist mobilizing on the supply side. One such obstacle is the presence of a “first-past-the-post” electoral system, which benefits large parties with regional concentrations and discourages fringe parties’ success (Triadafilopoulos and Taylor, Reference Triadafilopoulos, Taylor, Samy and Duncan2021). Another important impediment to nativist populism is the role of linguistic and regional cleavages in limiting the resonance of pan-Canadian conceptions of the people (Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Jeram and Van der Linden2020).

Yet, the exceptionalism of Canadian populism with respect to nativism is also worthy of reconsideration. Research suggests that while Canadians generally score lower on the nativism scale, populist attitudes are prevalent in the public, whether or not supply-side factors are present (Medeiros, Reference Medeiros2021). Moreover, implicit discourses of exclusion have long permeated Canadian politics. For instance, in the discourse of Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper (2006–2015), the boundaries of the people were purposely kept discursively ambiguous and a wedge was created between “good” and “bad” immigrants. This enabled the party to increase its vote share in immigrant communities and achieve a minimum winning coalition lasting two terms, while simultaneously limiting the scope of policies related to immigration and multiculturalism (Abu-Laban, Reference Abu-Laban and Jedwab2014). When such discourses and policies began to take a more explicit form—for instance, through references to “old stock Canadians,” plans to target “barbaric cultural practices,” attacks on “fraudulent refugee claims” and a proposed niqab ban in citizenship ceremonies—the Harper government lost its hold over the immigrant vote and was ultimately defeated (Carlaw, Reference Carlaw2017; Friesen, Reference Friesen2021; Kwak, Reference Kwak2020).

The exclusion of immigrant minorities has been a far more explicit aim of the PPC, which Maxime Bernier, a former Conservative cabinet minister, founded in 2018 following a failed bid—with a very close margin—to lead the Conservative Party of Canada. A comparison of the party’s website, public statements and other written materials with those of other right-wing parties by Peker and Winter (Reference Peker and Winter2024) shows that the PPC pledges to reduce immigration and end Canadian multiculturalism, thereby casting aside the “cult of diversity” established by Justin Trudeau. The party’s official materials also explicitly refer to Canada’s immigration policy as a mechanism to “forcibly change the cultural character and social fabric of our country” (cited in Peker and Winter, Reference Peker and Winter2024: 13). The right-wing populist political rhetoric of exclusion also increasingly targets feminists and 2SLGBTQ+ minorities. Erl’s (Reference Erl2021) study of election survey data showed that PPC supporters showed hostility to feminism and opposed so-called special privileges for women. The fight against radical gender ideology is also a key tenet of the PPC’s current platform (People’s Party of Canada, September 4, 2021). While the party’s relative success in the 2021 election might be more directly related to opposition to COVID-19-related restrictions, nativist and populist attitudes are also influential predictors for supporting the PPC (Medeiros and Gravelle, Reference Medeiros and Gravelle2023).

Contrary to the exceptionalism literature, therefore, populism has long been a force in Canadian politics, manifested in both right- and left-wing ideological projects. Moreover, there is evidence that exclusion of others features both implicitly and explicitly in Canadian political rhetoric, although parties engaged in explicit discourses of exclusion along nativist lines (for example, the PPC) have had limited success at the ballot box. To what extent are the hypotheses and categories elicited by the European experience capable of capturing the contours of Canada’s evolving populist zeitgeist? To answer this question, we employ a methodological approach that estimates the prevalence and intensity of three populist political discourses—“people-centrism,” “anti-elitism” and “exclusion of others”—in original tweets published by federal party leaders across the political spectrum.

Methodology

Researchers have devised several strategies to operationalize and measure populism. One approach uses expert surveys to estimate the presence of populist rhetoric within a political party, often in cross-national perspective (Meijers and Zaslove, Reference Meijers and Zaslove2021; Norris, Reference Norris2019, Reference Norris2020). In a prominent study based on this technique, Norris (Reference Norris2019) uses the Chapel Hill Expert Survey to compare populist rhetoric—operationalized as anticorruption and anti-elitism—across a wide range of European countries. The author then considers how populism interacts with other dimensions of politics, including cultural cleavages (authoritarianism, liberalism) and economic ones (left, right). While they provide a useful snapshot of the prevalence of select populist themes across parties, and are therefore beneficial to comparative research, studies based on expert surveys suffer significant drawbacks. Based as they are on experts’ holistic evaluations of parties, they tend to freeze those parties in time, thus precluding attention to populism’s continuous or contingent features. Expert-based research is also unlikely to consider the kinds of people and elites that parties construct to gain resonance with the electorate. This leaves unanswered questions about whether and how party ideology (left vs right) corresponds with populist political communication styles in different settings.

A second approach to measuring populism is based on holistic grading, wherein researchers devise coding schemes to rank whole documents (for example, speeches, manifestos or press releases), and occasionally paragraphs (Rooduijn and Pauwels, Reference Rooduijn and Pauwels2011; Rooduijn et al., Reference Rooduijn, De Lange and Van Der Brug2014), and grade them on a populism scale (Bernhard and Kriesi, Reference Bernhard and Hanspeter2019; Fahey, Reference Fahey2021; Hawkins, Reference Hawkins2009; Pauwels, Reference Pauwels2011). In Hawkins’s (Reference Hawkins2009) foundational application of the method, a document counts as populist if it divides the political field into good people versus the evil elite and understands the elite as subverting the peoples’ interests. A text is graded 0 if not all elements of populism are present, a 1 if all elements are present but not consistently used and a 2 if all elements are present and consistently used (Hawkins, Reference Hawkins2009).Footnote 2 While the simplicity of this approach may be advantageous, holistic grading in its basic form precludes clear understanding of the ways that populism’s multiple dimensions interact (Meijers and Zaslove, Reference Meijers and Zaslove2021: 377).

A third approach to measuring populism, which we adopt in this study, uses social media data to ascertain the presence of populism as a communication style (Engesser et al., Reference Engesser, Ernst, Esser and Büchel2017; Ernst et al., Reference Ernst, Sina Blassnig, Büchel and Esser2019; Jagers and Walgrave, Reference Jagers and Stefaan2007; Maurer and Diehl, Reference Maurer and Diehl2020; Zulianello et al., Reference Zulianello, Albertini and Ceccobelli2018). Studies in this vein frequently consider how different dimensions of populism (such as people-centrism, anti-elitism and exclusion of others) interact with parties’ other characteristics (that is, right/left, challenger/incumbent, extreme/mainstream). The focus on social media is also advantageous, given its popularity as a tool for reaching large audiences in a relatively unmediated way. Social media algorithms are also known to funnel users to partisan information with which they are already likely to agree, thus strengthening the base of political movements (Pajnik, Reference Pajnik, Diehl and Bargetz2024). And, importantly when it comes to populism, social media are often perceived as a “voice for the underdog and the unrepresented,” providing means for “crowd building” among the politically disaffected (Gerbaudo, Reference Gerbaudo2018).

However, there are drawbacks to existing strategies for using social media to estimate populism. While types of elites are frequently given attention, rarely are the types of people invoked by political actors explored in these studies (for example, Jagers and Walgrave, Reference Jagers and Stefaan2007; Maurer and Diehl, Reference Maurer and Diehl2020). This is a significant oversight, given that different brands of populism identify the people’s interests in substantively different ways (Brubaker, Reference Brubaker2020). Similar blind spots exist with respect to understanding the exclusion of others. Perhaps because of a focus on the European experience, several studies single out and quantify negative references to immigrants in social media speech (for example, Maurer and Diehl, Reference Maurer and Diehl2020). However, the targeting of other minority groups—including 2SLGBTQ+ communities—to demarcate the people is rarely explored. Given evidence that exclusion of these communities is of growing significance to populism in North America (Stein, Reference Stein2023), this may lead to underestimating the exclusionary dimension of certain politicians’ populist rhetoric.

We aim to address these oversights in our quantitative analysis of 5,845 original tweets posted by federal party leaders on X (formerly Twitter) between January 1 and December 31, 2022. By that year, pandemic-related frustrations and public divisions occupied an increasingly prominent place in Canadian politics, which, by some accounts (McCullough, Reference McCullough2022), strengthened the role of parties, leaders and movements adopting right-wing populist discourses. Just a few months earlier, in the federal election of September 2021, the far-right PPC tripled its 2019 vote based on an anti-multiculturalist and anti-COVID mandate platform. Shortly thereafter, in early 2022, the Freedom Convoy opposing vaccines and other mandates drew international attention by shutting down the city of Ottawa for three weeks. Coinciding with these events was a marked spike in Google searches of the phrase “populism in Canada” (Peker et al., Reference Peker, Rémi and Laxer2023).

Our analysis focuses on the X activity of six federal party leaders. Justin Trudeau (1,607 tweets) was Prime Minister and leader of the centrist Liberal Party of Canada at the time of the study. Pierre Poilievre (1,541 tweets) announced his candidacy for the leadership of the right-wing Conservative Party of Canada at the height of the “Freedom Convoy” and was elected leader in September 2022. Jagmeet Singh (737 tweets) was leader of the left-wing New Democratic Party. Yves-François Blanchet (700 tweets) leads the Bloc Québécois, a party that advocates for Québec nationalism and interests at the federal level with a view to promoting Québec sovereignty, and only runs candidates in that province. Maxime Bernier (967 tweets) is leader of the far-right PPC, and Elizabeth May (293 tweets) led the Green Party of Canada in 2022. These tweets were collected using the X Application Programming Interface (API).Footnote 3 We focus on original tweets (we exclude retweets, for example) in order to prioritize content produced directly by the federal leaders.

Tweets were coded manually by a team of research assistants based on a codebook developed by the authors, which operationalizes the three main discourses associated with populism as a communication style: people-centrism, anti-elitism and exclusion of others. In a first round of coding, the exact terminology constituting each discourse was recorded. We then conducted a second round, grouping statements belonging to each discourse into common categories. We defined people-centrism as any statement referring positively to a group or community whose interests the leader in question claims to represent. This operationalization follows the approach adopted by Jaggers and Walgrave (Reference Jagers and Stefaan2007) and reproduced by others (Pauwels, Reference Pauwels2011; Maurer and Diehl, Reference Maurer and Diehl2020; Zulianello et al., Reference Zulianello, Albertini and Ceccobelli2018).Footnote 4 Depending on the characteristics assigned to the people, attributes of this variable were categorized as general, economic (that is, communities defined by their material interests), political (that is, communities defined in terms of their political/rights-based interests), cultural (that is, communities defined by their cultural interests) and other.Footnote 5 We defined “anti-elitism” as any statement referring negatively to an individual, organization or institution in a position of power, whose actions were deemed to undermine the interests of the people. Categories of this variable include elites who are political, economic, cultural, foreign and other.Footnote 6 Finally, we defined “exclusion of others” as any negative statement about a third out-group, besides the elite. Given our interest in estimating the value of hypotheses derived from European cases, where the focus is on immigrant out-groups, we prioritized negative statements addressing immigrants, and other ethno-cultural or linguistic minorities in our operationalization of others. We also demarcated negative statements pertaining to 2SLGBTQ+ communities, as they are an increasingly targeted identity group in right-wing populisms in North America (Stein, Reference Stein2023).Footnote 7

Based on these variables, we tested three hypotheses about populism’s key discourses and their relationships to party ideology.

H1: People-centrism: We expect, based on the literature, that right-wing parties displaying people-centrism will be more likely to define the people in cultural terms, whereas left-wing parties engaging in this tactic will define the people in primarily economic terms.

H2: Anti-elitism: We expect that right-wing parties deploying this discourse will primarily target cultural and political elites, whereas left-wing parties engaging in anti-elitism will primarily target economic or corporate elites.

H3: Exclusion of others: According to the literature, this discourse appears among right- but not left-wing parties. As such, right-wing parties should be more likely to display signs of exclusion of others.

To estimate the significance of each discourse in the leaders’ tweets, we adapted the index developed by Jagers and Walgrave (Reference Jagers and Stefaan2007). This index combines two measures: proportion (that is, the number of characters associated with each discourse divided by the total number of characters) and intensity (that is, the total number of times a discourse is mentioned in the dataset). Our index is a simple multiplication of proportion by intensity, divided by 100.

Two points about our sampling strategy should be noted. First, recognizing that there were significant discrepancies in the overall X activity of each leader during the period under study (with Trudeau being the most active, at 1,607 original tweets, and May being the least active, at 293 original tweets), we devised two different versions of the indexes of people-centrism, anti-elitism and exclusion of others. The first version involved measuring the significance of each variable controlling for differences in the overall X activity of the six leaders. To achieve this, we administered a weight to the intensity scores. Specifically, we multiplied the intensity scores by 700 (the number of tweets posted by Blanchet during the period examined), divided by the total number of tweets posted by each politician. For example, the weights applied to May, Singh and Poilievre were 700/293, 700/737 and 700/1541, respectively.Footnote 8 The second version seeks to capture actual differences in the content published by each party leader without controlling for overall X activity. In this series of analyses, we estimate the significance of each variable for the entire sample of tweets. Although it relies on unweighted data, this method allows us to ascertain the real magnitude of populist discourses put out by each leader on X. Below, we present results based on both the weighted and unweighted samples, allowing us to comparatively evaluate both sets of measures. Second, as Poilievre did not become party leader until more than halfway through the year, in September 2022, we ran the analyses separately to compare the results based on the full sample of tweets for the year 2022 to those based on the subperiod from September 10 to December 31, 2022, during which Poilievre became leader of the CPC. Finding no significant differences in the overall patterns among politicians between the two time periods, we proceeded to analyze results for the year as a whole.

Results

People-centrism

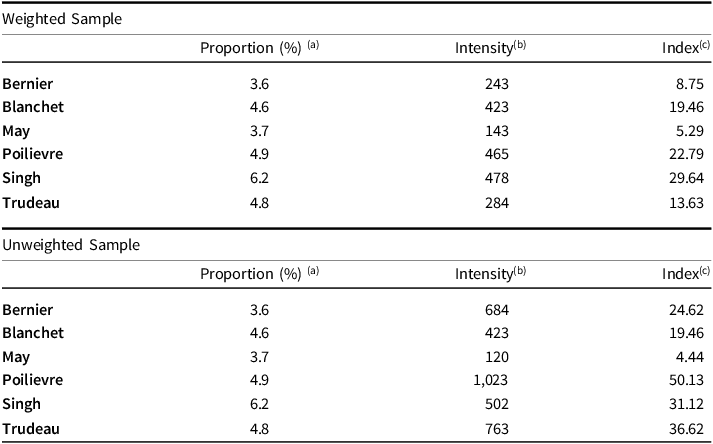

To assess the significance of people-centrism, we used the index of positive mentions of the people. As Table 1 indicates, the sampling strategy (weighted versus unweighted) did not significantly affect overall patterns in the degree of “people-centrism” exhibited by each political leader. The weighted results indicate that Singh is the most likely to invoke the people on X, with May being the least likely to engage in people-centrism, followed closely by Bernier. While Singh’s frequent mentions of the people consist with evidence that left-wing politicians, such as Bernie Sanders in the United States, are prone to people-centrism (Maurer and Diehl, Reference Maurer and Diehl2020: 459), Bernier’s limited use of this discourse conflicts with evidence that right-wing populisms are also prone to this discourse (Jagers and Walgrave, Reference Jagers and Stefaan2007: 327; Maurer and Diehl, Reference Maurer and Diehl2020: 459). Next to Singh, Poilievre and Trudeau are the most people-centric, a somewhat unexpected result given expectations that populist discourse is most pronounced among nongoverning parties (Jagers and Walgrave, Reference Jagers and Stefaan2007), especially newer challenger parties and parties at the margins of the political spectrum (Ernst et al., Reference Ernst, Sina Blassnig, Büchel and Esser2019: 11).

Table 1. Proportion, Intensity and Index of People-Centrism by Party Leader

Notes: (a): Number of characters associated with people-centrism, divided by the total number of characters, multiplied by 100. (b): Total number of times the people are mentioned. (c): (a) multiplied by (b), divided by 100.

Table 2 considers the types of people invoked through party leaders’ people-centric discourses, using the unweighted sample of tweets. The results indicate that, when engaging in people-centrism, all six politicians primarily address the people in broad, generalizing terms, using words like “people,” “Canadians,” “we,” “you,” “men/women” and so forth. Patterns concerning more precise categories of people conflict somewhat with prevailing assumptions in the literature about the people-centric nature of right versus left populisms.

First, although Singh adheres to those assumptions by being the most likely to define the people in economic terms (39%), this tendency is relatively pronounced among the leaders of the largest three parties, including Poilievre (32%) and Trudeau (33%). There are, however, important qualitative differences in the types of economic constituencies highlighted by each leader, which coincide more closely with ideological differences. While all three politicians frequently refer to the people as workers, families and youth, Singh most often refers to the working class, Poilievre most frequently references taxpayers and consumers, and Trudeau is most prone to highlighting the economic interests of students and seniors.

Second, contrary to prevailing assumptions of right-wing populism, Poilievre is far more likely to address the people in economic (32%), than in cultural (7.1%) or political (3.5%), terms. Although Bernier follows the right-wing populist playbook more closely, displaying the greatest tendency to address the people as a political entity (18.7%), he is not the most likely to address the people’s interests in cultural terms (7.6%). That distinction belongs to May (20.0%). Once again, there are clear qualitative differences in the precise location of the cultural boundaries attributed to the people by these politicians, which reflect ideological differences. While Bernier often refers to the people using terms like civilization or the civilized world, May more often invokes the cultural interests and priorities of Indigenous and 2SLGBTQ+ communities.

Table 2. Categories of the People as Percent of all Instances of People-Centrism by Party Leader

Notes: This table uses the unweighted sample of tweets.

Our observations of people-centrism among Canada’s federal leaders therefore paint a mixed picture, providing only partial support for prevailing hypotheses. Regardless of the sampling method used, the federal politician most often labeled populist in Canadian political discourse—Maxime Bernier—is the least prone to people-centrism, which many identify as the basic pillar of populism. Moreover, contrary to the expectation that left- and right-wing parties imagine the people in primary economic and cultural terms, respectively, our results show that the emphasis on challenges to the people’s material wellbeing is widespread across the political spectrum.

Anti-elitism

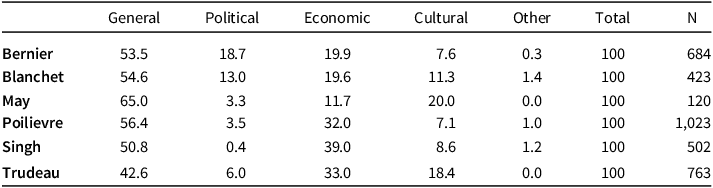

Having compared the federal leaders in terms of their propensity towards people-centrism, we turned to an examination of anti-elitism. Table 3 displays the proportion, intensity and index of this variable, differentiating between results based on the weighted versus unweighted samples. Once again, differences in sampling strategy did not affect overall patterns.

Table 3. Proportion, Intensity and Index of Anti-Elitism by Party Leader

Notes: (a): Number of characters associated with anti-elitism, divided by the total number of characters, multiplied by 100. (b): Total number of times elites are mentioned. (c): (a) multiplied by (b), divided by 100.

We found that Bernier displays the greatest propensity toward anti-elitism, while Trudeau and May are the least prone to this discourse.Footnote 9 In the case of Trudeau, this finding supports the expectation that anti-elitism is more pronounced among opposition parties. The case of May is more surprising: given the Green Party’s consistent opposition status, one would expect a greater propensity toward anti-elitism (Ernst et al., Reference Ernst, Sina Blassnig, Büchel and Esser2019).

Our results regarding the targets of anti-elite discourse also deviate somewhat from expectations. Table 4 displays the types of elites mentioned by the six leaders, as percentages of all instances of anti-elitism, for the unweighted sample of tweets. Within category comparisons across the political leaders generally conform to our hypotheses. Expectations of right-wing populisms are borne out by the fact that Bernier (71.7%) and Poilievre (75.6%) are—save for Blanchet (77.5%)—the most likely to target political elitess and that Bernier is the most likely to negatively address the media, academics and other cultural stakeholders (11.6%). In Blanchet’s case, mentions of political elites often involve concerns raised about jurisdictional boundaries vis-à-vis the federal government in the context of longstanding efforts to increase Québec’s provincial/national autonomy. Moreover, the fact that Singh is by far the most likely of all politicians (46.1%) to criticize economic elites also conforms to expectations of left-wing populism. Trudeau was the most likely of all politicians to address foreign elites (mainly Putin), and Poilievre scored highest in mentions of other elites because of his tendency to refer to target unspecified “gatekeepers” in his tweets.

Table 4. Categories of Elites as Percent of all Instances of Anti-Elitism by Party Leader

Notes: This table uses the unweighted sample of tweets.

However, comparisons across categories for individual politicians paint a more nuanced picture. While he leads the pack in targeting economic elites, Singh addresses political elites in almost equal measure (46.5%). In fact, in the discourses all leaders except Trudeau, political elites receive the largest proportion of negative attention. This result may reflect the role of context in determining the targets of anti-elitism. During the period we examined, 2022, federal government initiatives to address COVID-19 were in full swing, likely rendering it an especially likely target of criticism. On the right, this manifested mainly in opposition to vaccine mandates and restrictions, as well as in perceptions that Liberal fiscal policies had led to inflation (see also Laxer et al., Reference Laxer, Rémi and Peker2023). On the left, criticism of the federal government manifested primarily in claims that healthcare mismanagement and underfunding were putting patients at risk and financial support for workers dislocated by the pandemic were insufficient.

Exclusion of others

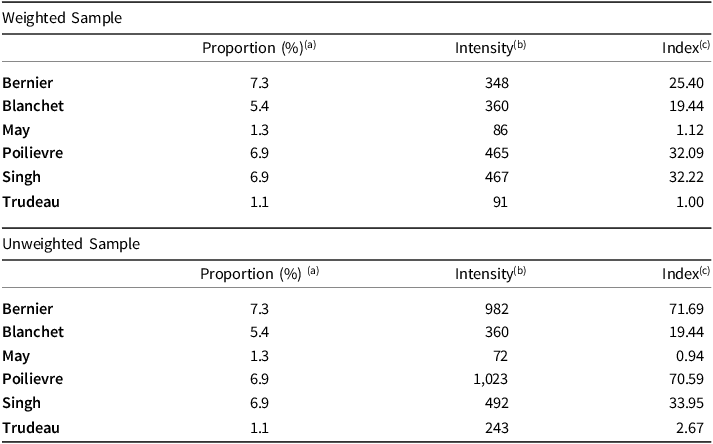

Evidence pertaining to the exclusion of others appears in Table 5. We included two main groups in our definition of “others.” To enable comparison with European right-wing populisms, which are known to elicit distrust of immigrant minorities in particular, we included negative mentions of immigrants as well as ethnocultural and linguistic communities. In addition, considering the increasing negative focus on transgender and gender nonbinary individuals in right-wing populist discourse (Stein, Reference Stein2023), we included negative mentions of 2SLGBTQ+ communities in our operationalization of others.

Table 5. Proportion, Intensity and Index of Exclusion of Others by Party Leader

Notes: (a): Number of characters associated with exclusion of others, divided by the total number of characters, multiplied by 100. (b): Total number of times others are mentioned. (c): (a) multiplied by (b), divided by 100.

In keeping with the literature of Canadian exceptionalism, just two of the six leaders—Bernier, and to a lesser extent, Blanchet—negatively referred to immigration and/or minority communities, although in quite different ways, in their tweets in 2022. In the case of Bernier, negative mentions echo more closely European right-wing populist rhetoric, mainly targeting immigrants, “fake refugees” and transgender individuals (often referred to as “perverts”) and appeared in 0.6 per cent of all characters. Blanchet’s negative mentions of other groups, by contrast, appeared in just 0.1 per cent of all characters and contained no reference to 2SLGBTQ+ communities. These mentions, very few in number, focused predominantly on mass immigration and “irregular refugees/migrants.” Exemplifying minority nationalism within a federation, the case of the Bloc speaks to the recent politicization of immigration in Québec politics, which goes hand in hand with the demand to have more control over immigration and cultural politics (particularly regarding the French language and secularism) vis-à-vis the federal government (Xhardez and Paquet, Reference Xhardez and Paquet2021).

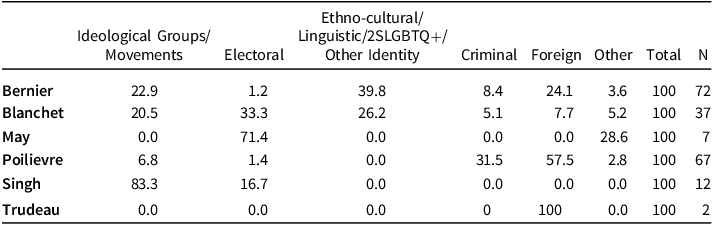

Negative mentions of others beyond those defined by immigration, ethnicity, language, sexual orientation or gender identity are displayed in Table 6. Results show that Singh is most prone to negative mentions of ideological groups and movements (83.3%), mainly the Freedom Convoy, “white supremacy” and “far-right extremism.” By contrast, Bernier, who addressed ideological groups and movements in 22.9 per cent of his negative mentions of others, mainly targets those related to “wokism,” “gender ideology” and “radical gender activism.” Poilievre’s negative mentions of others mainly target criminals (31.1 per cent) and foreign powers, often referred to as “dictators” (58.1%). Trudeau’s negative mentions of others are directed at criminals (33.3%) and foreign powers, mainly Russia (66.7%). Blanchet’s targeting of others beyond those defined by immigration, ethnicity and language focuses mainly on electoral opponents and ideological groups (that is, the Freedom Convoy).

Table 6. Categories of Others as Percent of all Instances of Exclusion of Others by Party Leader

Notes: This table uses the unweighted sample of tweets.

Our observations with respect to the exclusion of others thus support the Canadian exceptionalism literature, indicating a very limited propensity among all six politicians to negatively address others outside the elite. Exclusionary statements targeting immigrants, ethnocultural, linguistic and 2SLGBTQ+ groups are especially rare. This suggests that populism in Canada primarily operates on a vertical plane, emphasizing antagonism between the people and elites, with horizontal claims addressing conflicts between the people and others appearing far less frequently. In the next section, we consider the prevalence of all three discourses in tandem, in hopes of gaining insights into how populism, as a multidimensional phenomenon, manifests in Canada compared to Europe.

Populism in multidimensional perspective

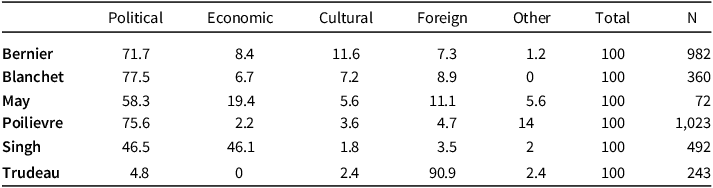

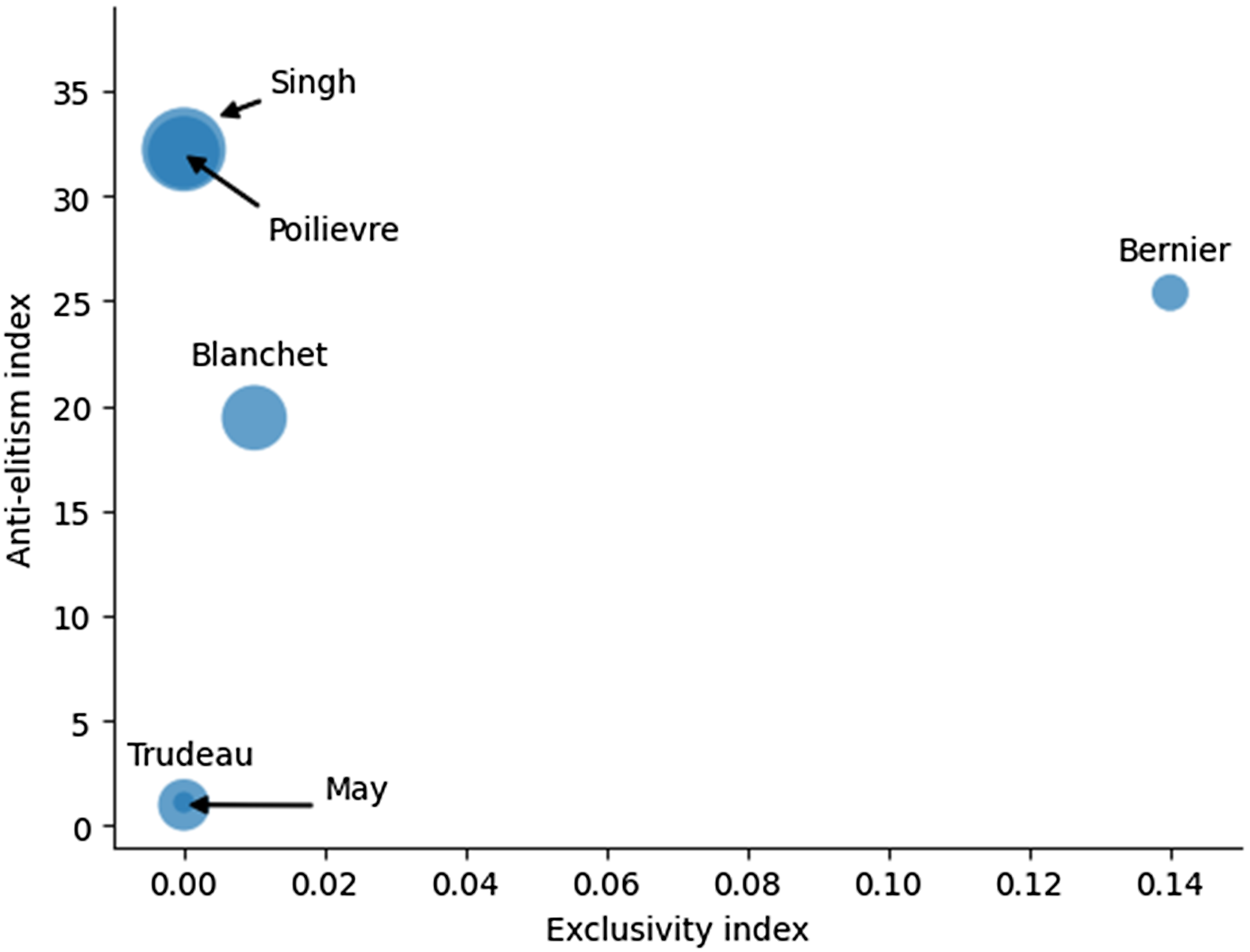

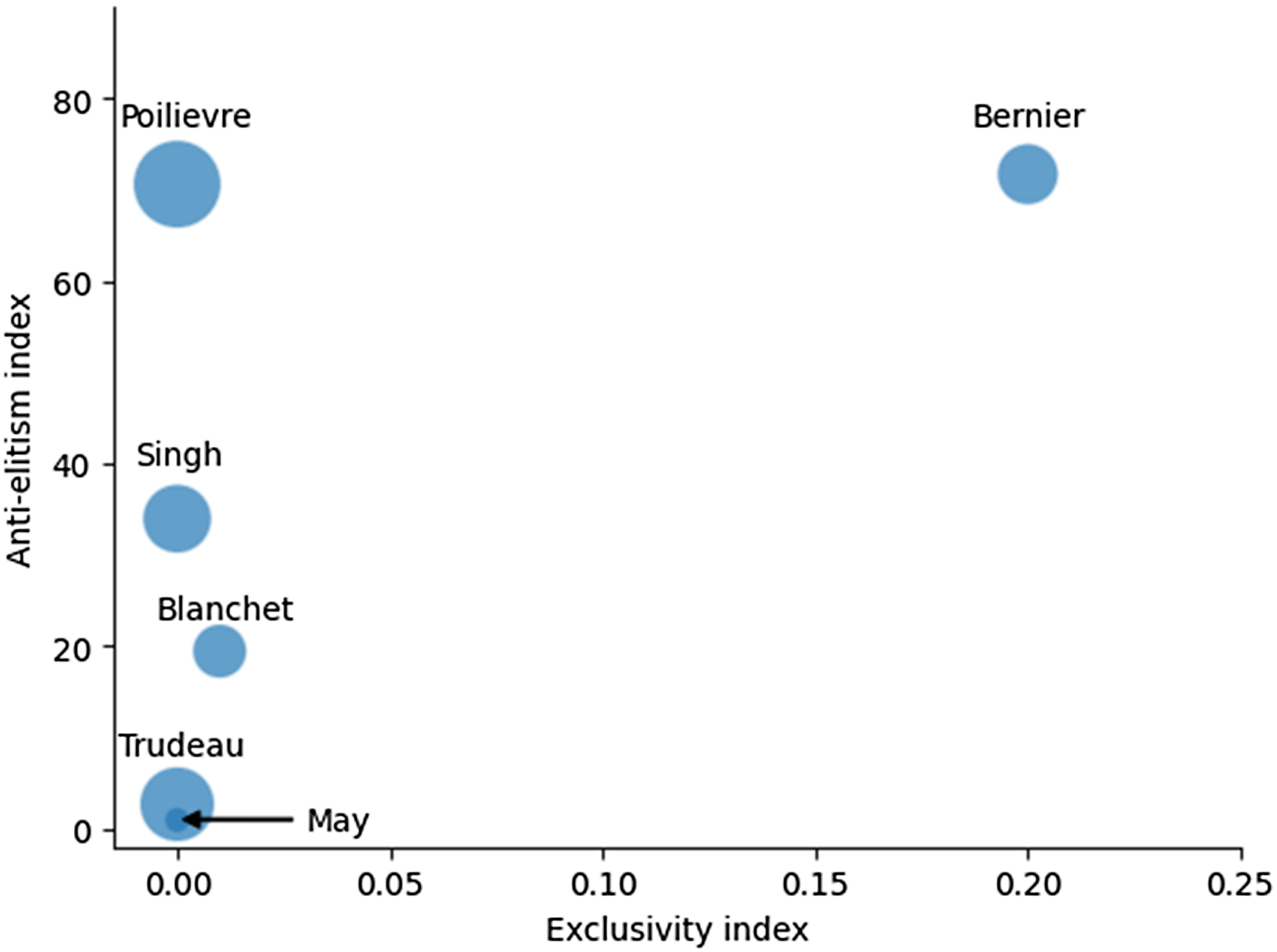

Figures 1 and 2 broadly replicate the approach taken by Jagers and Walgrave (Reference Jagers and Stefaan2007) by presenting the three indexes measuring people-centrism, anti-elitism and exclusion of others in tandem, for both the weighted (Figure 1) and unweighted samples (Figure 2). People-centrism is represented by the size of the bubbles: the larger the bubble, the greater the leader’s propensity to engage in people-centrism. Anti-elitism and the exclusion of others are illustrated by the vertical and horizontal positions of the leaders’ bubbles: the higher the leader is situated in the graph, the greater his/her propensity to engage in anti-elitism and the further to the right he appears, the more he/she engages in exclusion of others, namely immigrants and communities defined by their ethnocultural, linguistic and 2SLGBTQ+ identities. The results differ substantially from those of Jagers and Walgrave (Reference Jagers and Stefaan2007), which showed that Belgium’s far-right Vlaams Blok was the only political party to engage in complete populism, clearly exhibiting the highest levels of people-centrism, anti-elitism, and exclusion of others.Footnote 10

Figure 1. People-Centrism, Anti-Elitism and Exclusion of Others Indexes by Party Leader, Weighted Sample

Notes: Exclusion of others in this graph is limited to negative statements about communities defined by their ethnocultural, linguistic, 2SLGBTQ+ or other identities.

Figure 2. People-Centrism, Anti-Elitism and Exclusion of Others Indexes by Party Leader, All Tweets

Notes: Exclusion of others in this graph is limited to negative statements about communities defined by their ethnocultural, linguistic, 2SLGBTQ+ or other identities.

Our findings suggest a far more nuanced relationship between party ideology and populism’s key stylistic discourses. The fact that Bernier occupies the upper right quadrant in both figures—displaying relatively high levels of anti-elitism and exclusion of others coincides with expectations of right-wing populism in the European literature. However, Pierre Poilievre, who leads the largest right-wing party in Canada and is often labeled a populist in Canadian political discourse, does not exhibit exclusion of others. In fact, he is no more prone to the exclusion of immigrants and communities defined by their ethnocultural, linguistic and 2SLGBTQ+ identities than his left-wing counterpart, Jagmeet Singh. Thus, when it comes to the nativist element of populism, the key ideological boundary is not between left and right, but between mainstream and fringe.

The extent to which ideology informs the vertical dimension of populism in Canada—anti-elitism—is more sensitive to sampling decisions. When we control for overall differences in leaders’ X activity (Figure 1), Singh appears nearly as prone to elite targeting as Poilievre. However, when we compare indexes based on the actual content published by the leaders (Figure 2), Poilievre and Bernier demarcate themselves as by far the most prone to anti-elitism. When it comes to the vertical dimension of populism, therefore, left-right ideology seems to be the defining factor.

Conclusions

This study set out to assess the theoretical validity and empirical reliability of hypotheses derived from the European literature on populism by applying these to the exceptional case of Canada. Focusing on the stylistic aspect of populism, we quantitively examined the discourses of people-centrism, anti-elitism and exclusion of others among federal party leaders on X, with the hope of clarifying relationships among these dimensions of populism and comprehending how party ideology relates to populist communication styles. Our findings depart from expectations derived from the study of European populisms, with implications beyond the Canadian case.

A first implication of our findings concerns the theoretical and empirical value of people-centrism, used as a key discursive measure of populism by Jagers and Walgrave (Reference Jagers and Stefaan2007) and others. We found this variable to be of limited analytic use in delineating the communication styles of political leaders in Canada. One reason is the ubiquitous use of people-centrism across the political spectrum, as would be expected in democratic conversation (Canovan, Reference Canovan, Mény and Surel2002); the other is its lack of correlation with the other two discourses. Justin Trudeau, for instance, who displayed virtually no signs of anti-elitism or exclusion of others, displayed relatively high levels of people-centrism. By contrast, Maxime Bernier, the politician most prone to combining anti-elitism with exclusion of others, was among the least people-centric. These findings echo those that March (Reference March2017: 289) reports with respect to the United Kingdom, where the average people-centrism score is generally higher for mainstream parties compared to their populist counterparts. March (Reference March2017: 290) interprets these results as evidence that demoticism—a “closeness to ‘ordinary’ people” without antagonism—is on the rise, as all parties seek to maximize their resonance in increasingly majoritarian and polarized political systems. In his words, this shift “may facilitate populism but is not synonymous with it” (290, emphasis added). We concur with this interpretation and further propose that the transcendent nature of people-centrism suggests we need to be cautious in applying a gradational approach to populism. This approach is a response to concerns that categorical references to populists and non-populists are essentializing and insufficiently nuanced. While we broadly agree with this and have applied a gradational methodology in the present study, our results suggest that, particularly when applied separately to individual dimensions of populism, “degreeism” can be taken too far, muddying the conceptual waters.

Second, our findings bring concrete empirical evidence to bear on the hypothesis that Canada is “exceptional” when it comes to the nativist dimension of populism. Among federal leaders on X, engagement in discourses that explicitly exclude immigrant, ethnocultural, linguistic and/or 2SLGBTQ+ others is rare and mainly spearheaded by the PPC. This finding is at odds with the European literature, which often portrays the exclusion of others as constitutive of (particularly right-wing) populism that tends to spill over to the mainstream (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Mondon and Winter2021). Although Canadian public support for immigration has recently showed signs of decline, due especially to economic issues, the supply-side factors identified in the exceptionalism literature—such as Canada’s electoral system and geography—arguably discourage most federal parties from adopting a nativist language. This finding calls for an expansion of the tools currently being used to define and operationalize right-wing populisms in global comparative perspective.

At the same time, there may be grounds to consider a wider range of tactics used by right-wing party leaders to generate a sense of us versus them in Canadian politics. One of these tactics involves politicians’ (not-so)-implicit endorsement of right-wing conspiracy theories that invoke the threat of outsiders, without necessarily directly targeting immigrants or ethnic minorities. An example of these theories, “The Great Reset,” is embraced by several key political actors and grassroots organizations, including those involved in the Freedom Convoy (Farokhi, Reference Farokhi2022). Its adherents believe that governments and global elite organizations (such as the World Economic Forum) are exploiting the COVID-19 pandemic (which they may have instigated) to expand their powers and forge a global communist society that will supersede national boundaries and eradicate individual freedoms (Christensen and Au, Reference Christensen and Ashli2023). By hosting interviews with, and appearing alongside, individuals and organizations that promote this thesis (Celestini and Warne, Reference Celestini and Warne2022), Maxime Bernier and Pierre Poilievre have effectively stoked fears about the permeability of Canadian nationhood. Poilievre himself actively participated in establishing the Great Reset narrative when he published an online video calling on audiences to “Stop the Great Reset” in November 2020, a phrase which quickly became a popular hashtag (Christensen and Au, Reference Christensen and Ashli2023: 2353). This flirtation with conspiracies tied to globalism arguably contributes to the erection of boundaries between us and them. This more recent development may warrant a reconceptualization and expansion of the exclusion of others dimension of right-wing populism, especially given that populism, nativism and conspiracism—despite being distinct phenomena—have been shown to function in complementary ways in multiple other cases (Bergmann, Reference Bergmann, Butter, Hatzikidi, Jeitler, Loperfido and Turza2024).

A third important finding concerns the convergence among Canada’s opposition leaders around a discursive emphasis on the people as a primarily economic community threatened by a primarily political elite. This pattern of convergence is especially relevant to comparative assessments of the discourses deployed by Singh and Poilievre. Representing distinct ends of the political spectrum, both politicians primarily define the people in economic terms while being the least likely to focus on the political dimensions of peoplehood. Yet, both primarily address political elites as responsible for the people’s economic challenges, although, unlike Poilievre, Singh is nearly as likely to emphasize the role of economic elites.

We have speculated that this convergence may reflect the importance of social and political context in moderating the effect of party ideology on populist communication styles. It also speaks to a related aspect of populism: that it is not a substantive political ideology, but is rather, as Brubaker (Reference Brubaker2021: 81) emphasizes, “defined by what it opposes.” While the target of populism—elites—is formally always the same, it is substantively variable and relational, taking advantage of shifting opportunities (Dufour, Reference Dufour, Guillaume Dufour and Peker2023: 53). This shape-shifting nature of populism has been especially evident during the pandemic. Whereas conservative ideologies are traditionally more sensitive to threats of contamination—and indeed, such threats were articulated early on through characterizations of COVID-19 as the “China” virus—the response of most right-wing populisms was to advocate freedom from government mandates directed at limiting the spread of the virus. Brubaker (Reference Brubaker2021) argues this is because the space of protectionism was already taken up, leading populist leaders to adopt anti-protectionist stances vis-à-vis the virus. Something similar may be occurring in our data with respect to party positions on the economic impacts of COVID-19. Although they attribute these impacts to somewhat different “elite” forces, federal leaders saw a political opportunity to harness the sense of material dislocation elicited by the pandemic and use it to question the actions and intentions of the sitting government.

In interpreting these findings, the limitations of our study should also be considered. Our focus on the year 2022 necessarily precludes us from assessing whether and to what extent the nature and prevalence of populist discourses in that year might differ from the period before or since. One could posit, for example, that, besides contributing to Trudeau’s resignation as Liberal leader on January 6, 2025 accumulating charges of elitism put pressure on the Trudeau government to amplify its own targeting of corporate elites, encouraging it to demand that large grocery chains stabilize their prices in 2023 and to propose increasing the capital gains tax in 2024. Testing this and other hypotheses related to context would require a larger time frame. In addition, because our purview is limited to party leaders, we do not consider the discursive repertoires of party representatives. Expansion of the study to include whole party rosters might yield differing results, given the professionalization and branding that go into leaders’ social media publications.

Ultimately, our findings confirm the relevance of studying populism as a phenomenon that can be assessed—at least partially—in the domain of social media, thus adding to a growing research field relating to “digital populisms” (Bobba, Reference Bobba2019; Bartlett et al., Reference Bartlett, Birdwell and Littler2011). While it is beyond the scope of this article to comment on the real-life implications and relationships of these digital activities, the results attest to the opportunities for developing rigorous measures for populism using data available thanks to information technologies. Our findings also underline the theoretical and empirical value of addressing populism as a multidimensional and context-dependent phenomenon. Unidimensional and holistic approaches lack conceptual depth and validity because populism is, by definition, a relational phenomenon. It thrives on articulations of vertical and (often) horizontal antagonisms. Yet, despite growing emphasis on multidimensionality (Meijers and Zaslove, Reference Meijers and Zaslove2021: 377), much research remains invested in the use of blunt categories (people/elite) and preconceived ideas about what differentiates populist communication styles among left- versus right-wing parties. Our results show that, when defined multidimensionally, with attention to precise characterizations of the people and elite, populist discourses intersect with party ideology in unexpected ways. Grasping these unexpected constellations, moreover, requires close attention to context. Just like political claims-making generally, populist communication is responsive to political opportunities.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.