In nation-states, immigration governance is closely connected to politics of belonging (Winter, Reference Winter2024). The regulation of immigration is therefore a core jurisdiction of the national state, related to regalian powers and border control (Scholten and Penninx, Reference Scholten, Penninx, Garcés-Mascareñas and Penninx2016). Nation-states determine which, and how many, people are allowed to immigrate and under what conditions (Boushey and Luedtke, Reference Boushey and Luedtke2006). Nation-states thus create entry categories that are tied to various bundles of rights.

In federal states, however, immigration regulation is frequently shared with subnational levels of governance (Hepburn and Zapata-Barrero, Reference Hepburn and Zapata-Barrero2014; Zapata-Barrero et al., Reference Zapata-Barrero, Caponio and Scholten2017). As a result, these processes are more complex. In political science literature, this multi-governance model is described as immigration federalism. This refers to the sharing of prerogatives over immigration regulation and policymaking at different levels of government, as well as those levels of governments’ modes of interaction (Baglay and Nakache, Reference Baglay and Nakache2014: 6). Immigration federalism takes different forms depending on particular countries and time periods, and it involves (re)negotiations around the degree of decentralisation and the type of migration regulation concerned (Baglay and Nakache, Reference Baglay and Nakache2014; Paquet, Reference Paquet2016). More specifically, subnational units may have greater or lesser jurisdiction over immigration regulation and cooperate to a varying extent with other levels of government (Balgay and Nakache, 2014; Boushey and Luedtke, Reference Boushey and Luedtke2006; Hepburn and Zapata-Barrero, Reference Hepburn and Zapata-Barrero2014).

Most subnational units have integration and settlement capacities (Xhardez, Reference Xhardez2019). Some have enforcement capacities like in the United States (Chacón, Reference Chacón, Baglay and Nakache2014), or prerogatives more directly related to nation-building. This is the case of Germany and Switzerland's subnational units, which have a say in the naturalisation process (Baglay and Nakache, Reference Baglay and Nakache2014: 5), and of Canada and Australia's, which have unique selection powers (Paquet, Reference Paquet2019; Xhardez, Reference Xhardez2024).

Subnational units’ selection powers constitute an unusual form of immigration federalism. These are especially developed in Canada, where provinces contribute to a variable degree to the selection of an increasing proportion of economic immigrants (Picot et al., Reference Picot, Hou and Crossman2024), most of whom have previous temporary experience in Canada (Hou et al., Reference Hou2020). In fact, provinces appear to significantly drive an important trend in immigration policy, which is the noticeable increase in two-step migration—whereby transition to permanent residency (PR) is conditional on a temporary experience (Picot et al., Reference Picot, Hou and Crossman2023). However, the effect of the interaction between the process of federalization of immigration (Paquet, Reference Paquet2014) and two-step migration on migrants’ experiences is not well understood.

Research on the federalization of immigration mostly focuses on institutions and intergovernmental relations and norms (Paquet, Reference Paquet2016), as well as on the federal or very local levels rather than the meso level, such as provinces (Xhardez, Reference Xhardez2019). Comparatively, its consequence on noncitizens is given little consideration in the literature, a fact deemed “problematic given that immigration is first and foremost about people, and therefore, its analysis cannot be focused exclusively on the interests of the host states” (Baglay and Nakache, Reference Baglay and Nakache2013: 334). While some researchers have theoretically examined which form of immigration federalism might benefit migrants’ rights (for instance, Spiro, Reference Spiro2001; Vineberg, Reference Vineberg, Baglay and Nakache2014), they seldom examine it empirically and from a qualitative lens.

Therefore, this article complements the existing literature by providing deeper insight into the effects of multilevel governance of immigration on migrants’ experiences. More specifically, it analyzes how the federalization of two-step migration affects migrants’ transition process from temporary to permanent status, whereby immigrants become “included.” How do migrants negotiate and perceive this federalized inclusion process?

The province of Québec in Canada offers a particularly relevant vantage point to explore these questions because, contrarily to other Canadian provinces, Quebec selects all of its new economic immigrants, mostly through a two-step migration program (Fleury et al., Reference Fleury, Bélanger and Aline Lechaume2020). In practice, this means that PR applicants in Quebec (or those wishing to settle in the province) must be selected by the province before applying to a distinct PR program at the federal level. Moreover, as Canada's only French-speaking province,Footnote 1 the province considers itself to have a distinct identity. There are historical tensions between Quebec and the federal government over the protection of this identity and the autonomy—and even sovereignty—of the province, which contributed to its investment in immigration matters (Barker, Reference Barker2015; Iacovino, Reference Iacovino, Hepburn and Zapata-Barrero2014; Paquet, Reference Paquet2016). Because Quebec considers immigration to be an area of competitive nation-building, it implemented a distinct “integration regime” (Iacovino, Reference Iacovino, Hepburn and Zapata-Barrero2014: 93; Barker, Reference Barker2015), which has historically emphasized the economic value of immigration for the province (Houle, Reference Houle, Baglay and Nakache2014). This political stance was disrupted by the nationalist provincial party Coalition avenir Québec (CAQ), which took power in 2018. This right-wing political party has formed a majority government since its first election and has tied migrant selection to “nation-building” and identity at the provincial level. This produced a conflictual relationship with the federal government over immigration. Our article examines how this potential mismatch in political agendas and corresponding provincial and federal immigration policies affects applicants’ PR transition process.

Drawing from in-depth interviews with fourteen migrants interviewed three times (2019, 2020 and 2022) at different stages of their transition to PR, this article argues that the federalization of two-step migration produces an ambiguous process of inclusion, which partly results from contradictory federal-provincial political agendas and tensions. First, the article presents relevant past research, the context and the conceptual framework used. It then conceptualizes how the administrative process of immigration status transition constitutes an inclusion process and follows by an analysis of how this process is experienced by applicants. Instead of a progressive inclusion, the article argues that federalized two-step migration produces heightened risks of feeling, and experiences of, exclusion. Furthermore, instead of constituting a linear inclusion process into the province and the federal state, this form of two-step migration seems to favour provincial, rather than federal, belonging. In sum, this article contends that rather than functioning as an administrative process of linear inclusion, federalised two-step migration sets the stage for a struggle between federal and provincial nation-building aims—a competition played out in applicants’ lives.

Two-step Migration in Canada and Migrants of Uncertain Desirability

Migration has long been at the core of Canada's nation-building as a settler colonial state (Dauvergne, Reference Dauvergne2016). However, the exponential increase in temporary resident admissions—which has surpassed PR admissions since 2007 (Nakache and Kinoshita, Reference Nakache and Kinoshita2010)—marks a significant ideological shift towards a utilitarian use of migration to respond to short-term labour market demands (Dauvergne, Reference Dauvergne2016). Migration still appears to remain central to the country's nation-building (Rajkumar et al., Reference Rajkumar, Berkowitz, Vosko, Preston and Robert Latham2012), but now through new “hierarchies of rights and memberships in the Canadian nation” (Goldring et al., Reference Goldring, Berinstein and Bernhard2009: 247), as there is a growing group of people that resides on Canadian territory without full residency and the rights it provides (Goldring et al., Reference Goldring, Berinstein and Bernhard2009).

There are three main categories of residence statuses in Canada: citizenship, PR, and temporary residence. The Canadian scholarship examining the relationships between those statuses usually considers citizenship to be a secure status and permanent and temporary residence as precarious ones (Goldring and Landolt, Reference Goldring and Landolt2011; Rajkumar et al., Reference Rajkumar, Berkowitz, Vosko, Preston and Robert Latham2012). Indeed, citizenship is a “full” residence status which provides complete membership and access to social, economic, mobility and political rights (Goldring and Landolt, Reference Goldring and Landolt2011: 328). While we recognize that PR does not entirely protect from deportation nor provide political rights (Kaushal, Reference Kaushal and Dauvergne2021), we suggest that PR should be considered together with citizenship as a secure residence status, as 1) both offer full social rights and protections, indefinite stay,Footnote 2 geographical mobility, family reunification and free access to the labour market and education; and 2) PR holders are also eligible for citizenship (Rajkumar et al., Reference Rajkumar, Berkowitz, Vosko, Preston and Robert Latham2012). PR thus provides full social, economic and settlement inclusion into society as well as the possibility of full political inclusion.

By contrast, temporary residence is a precarious status providing limited rights compared to PR and citizenship (Goldring and Landolt, Reference Goldring and Landolt2011: 328). As temporary residence is subdivided into many different possible permits with varying durations and configurations of reduced rights—further modulated by one's nationality and province of residence—temporary residence produces what can be called differential levels of limited inclusion. Furthermore, temporary residence does grant eligibility to PR under certain conditions, but not to citizenship. Thus, PR is the main gate to cross to gain full inclusion into the society.

The divide between secure and precarious statuses is more or less porous depending on the temporary permit held, which itself depends greatly on nationality (Coderre and Nakache, Reference Coderre and Nakache2022). Literature shows that one's “entry category into Canada almost universally intersects with residency to heighten temporariness for some migrants while enhancing permanence for others” (Rajkumar et al., Reference Rajkumar, Berkowitz, Vosko, Preston and Robert Latham2012: 505), further highlighting the fact that several permits’ characteristics, such as their variable duration, facilitate or restrict the ability to qualify for PR (Haan et al., Reference Haan, Yoshida, Amoyaw and Natalie Iciaszczyk2021; Coderre and Nakache, Reference Coderre and Nakache2022; Rajkumar et al., Reference Rajkumar, Berkowitz, Vosko, Preston and Robert Latham2012). Two-step migration is one pathway from a precarious to a secure status. Designed to “‘skim’ the best prospects among temporary workers for inclusion” (Cook-Martín, Reference Cook-Martín2024: 2), it produces a double process of selection which further strengthens the “temporary-permanent divide” (Rajkumar et al., Reference Rajkumar, Berkowitz, Vosko, Preston and Robert Latham2012). Applicants are selected (1) for a temporary residence permit, by employers (for work permits), higher education institutions (for study permits) or the state for larger economic and cultural interests (through open work permits) (Bhuyan et al., Reference Bhuyan, Daphne Jeyapal, Sakamoto and Chou2017; Brunner, Reference Brunner2022), and then again (2) based on the “retrospective” assessment of the conformity of their temporary experience with the PR transition programs selection criteria (Sweetman and Warman, Reference Sweetman and Warman2010). Two-step PR selection serves to discriminate between those who are desired as full members of the state and meant to be “temporarily temporary” from those who are desired strictly for their temporary contributions and meant to remain “permanently temporary” (Rajkumar et al., Reference Rajkumar, Berkowitz, Vosko, Preston and Robert Latham2012). It also destabilizes the temporary/permanent dichotomy by producing a third category of people we call migrants of uncertain desirability. Indeed, they are desired to temporarily serve the labour market and higher institutions, but their desirability as permanent settlers is uncertain and tested against frequently shifting selection criteria, producing an uncertain temporariness. Further reinforcing this uncertainty, temporary residents must wait to get PR to become eligible to most settlement services, despite already residing in Canada (Rajkumar et al., Reference Rajkumar, Berkowitz, Vosko, Preston and Robert Latham2012).

In this context, increased provincial selection prerogatives sharpen the two-step migration selection process as provinces finely-tune their criteria to fit local economic/demographic needs (Xhardez, Reference Xhardez2024; Hou et al., Reference Hou, Crossman and Picot2020). Therefore, provincially selected permanent residents are selected based on their “desirability” for the province rather than for Canada as a whole. The growing scholarship on two-step migration in federal states contributes to documenting this interconnection. It shows that it is a “staggered process of entrance into the nation-state” (Robertson, Reference Robertson2013: 84), which entails different stages of temporariness. Further, it produces precariousness, risks of exploitation by employers and loss of status (Dennler, Reference Dennler2022) due to the difficulty of navigating frequently shifting policies and bureaucratic violence (Nourpanah, Reference Nourpanah2021; Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Bergen, Hajjar, Larios, Nakache, Bhuyan and Hanley2023). Applicants’ lives are often put on hold as the process affects their ability to both plan for the future and engage with the present (Dennler, Reference Dennler2021). In a study focusing specifically on the experience of a federalized two-step PR transition in Quebec, Bélanger et al. (Reference Bélanger, Myriam Ouellet and Fleury2023) contend that the addition of a provincial step “thickens administrative borders” and increases the complexity and the length of the administrative process, which in turn exacerbates applicants’ access to rights and risks of precariousness.

Federalized Migrants’ Selection and the Case of Quebec

An extensive scholarship examines the efficacy of jurisdiction-sharing in immigration regulation (for instance, Baglay and Nakache, Reference Baglay and Nakache2014; Hepburn and Zapata-Barrero, Reference Hepburn and Zapata-Barrero2014), including the optimal type of power sharing (Spiro, Reference Spiro2001; Vineberg, Reference Vineberg, Baglay and Nakache2014); the most appropriate level of governance depending on the immigration regulation considered (Baglay and Nakache, Reference Baglay and Nakache2014; Boushey and Luedtke, Reference Boushey and Luedtke2006; Thompson, Reference Thompson2011); and various criteria such as economic and political efficacy, optimal subsidiary principals and migrants’ rights protection, mostly from a theoretical point of view.

There is no consensus regarding which model of jurisdiction sharing is better for upholding migrants’ rights. Aldana argues that it is indeed “highly contextualized and cannot be generalized” (Reference Aldana2014: 89). While the issue remains contested, various researchers contend that economic migrants’ selection prerogative is better suited at the subnational level to better allocate public resources and respond to local labour market and cultural demands (Boushey and Luedtke, Reference Boushey and Luedtke2006). For similar reasons, Thompson (Reference Thompson2011) considers that immigration levels should primarily be set up by subnational entities. There is also little disagreement around the merits of a decentralized process of selection for migrants themselves (Boushey and Luedtke, Reference Boushey and Luedtke2006; Spiro, Reference Spiro2001), with both the central state and provinces working towards the same goal in a context of shared powers. The central state retains primary jurisdiction over this policy area while still allowing for some subnational units’ discretionary power (Zapata-Barrero and Barker, Reference Zapata-Barrero, Barker, Hepburn and Zapata-Barrero2014: 26).

Over several decades, Canadian provinces have been increasingly involved in immigration matters such as integration and selection, usually with the support of federal funds (Aldana, Reference Aldana2014; Paquet, Reference Paquet2016). Regarding selection, all provinces except for Quebec negotiated the development of Provincial Nominee Programs (PNPs), which grant them the capacity to select potential permanent residents while the federal government is in charge of their admission. Such programs seek to maximize immigrants’ labour market outcomes and retention (Xhardez, Reference Xhardez2024; Hou et al., Reference Hou, Crossman and Picot2020). With faster processing times and wider criteria of selection than federal programs of selection (Seidle, Reference Seidle2013), the PNPs are advantageous for migrants, suggesting a successful cooperation in that regardFootnote 3.

Quebec stands out in this immigration governance architecture. The province negotiated considerable selection powers with Ottawa, which were granted by a special agreement in 1991 (the Canada–Quebec Accord Relating to Immigration and Temporary Admission of Aliens). As a result, the province directly selects 100 per cent of its economic immigrantsFootnote 4 (Paquet and Xhardez, Reference Paquet and Xhardez2020: 2). In other words, all economic immigrants have to be selected by the province before applying to the federal level, rendering migrant selection part of two nation-building projects—that of Quebec, and that of Canada. Most economic immigrants are selected through a two-step migration program which entails a two-step application process. In 2019, two-step immigrants represented 86 per cent of all economic immigrants selected by QuebecFootnote 5 (MIFI, 2020). Similar to PNPs, this cooperation seemed beneficial for migrants (Fleury et al., Reference Fleury, Bélanger and Aline Lechaume2020). The province also tailors its own selection criteria, establishes PR admission levels in dialogue with the federal government (Paquet and Xhardez, Reference Paquet and Xhardez2020) and has the capacity to apply its selection criteria to categories of migrants other than economic migrants (Iacovino, Reference Iacovino, Hepburn and Zapata-Barrero2014: 92–93). Iacovino further argues that while Quebec does not control naturalization policy, “it has tailored its integration and settlement capacities to reinforce a regime of differentiated citizenship in emphasizing distinct terms of belonging” (Reference Iacovino, Hepburn and Zapata-Barrero2014: 93).

According to Zapata-Barrero and Barker, these distinct prerogatives produce an asymmetric, rather than cooperative, scenario, characterized by a situation in which the central state “allows the coexistence of several centres of decision-making based on efficiency/ national identity criteria […] but does no extend this to all units” (Reference Hepburn and Zapata-Barrero2014: 28). Iacovino (Reference Iacovino, Hepburn and Zapata-Barrero2014) considers the example of Quebec within the Canadian governance framework of immigration to be marked by a variable decentralisation responding to two differing logics: “efficiency/functionality, vs. national identity/autonomy” (Hepburn and Zapata-Barrero, Reference Hepburn and Zapata-Barrero2014: 13). Still, the literature suggests that with regards to migrants’ selection in particular, Quebec political parties have favoured efficiency over the protection of cultural distinctiveness (Houle, Reference Houle, Baglay and Nakache2014; Paquet, Reference Paquet2016). Quebec's selection policies were congruent with both Canada's and other provinces’ selection policies, and Quebec political parties all considered immigration to be positive for economic, demographic and identity reasons (Paquet, Reference Paquet2016; Xhardez and Paquet, Reference Xhardez and Paquet2021).

The election of the CAQ party in 2018 marked the return of a nation-building aim in migrants’ selection to the fore, as well as the migration-as-a-threat-to-be-regulated discourse (Xhardez and Paquet, Reference Xhardez and Paquet2021). In practice, the CAQ reduced the economic PR target between 2018 and 2019 by 20 per cent, significantly reformed its two-step PR program to increase the minimum level of French language and temporary work experience required and included a so-called values’ test. This “new form of nationalism” (Gagnon et al., Reference Gagnon, Xhardez, Antoine Bilodeau, Birch, Dufresne, Duval and Tremblay-Antoine2022) produced tensions with the federal government insofar as some CAQ measures are at odds with federal policies, in a context of shared prerogatives. Two-step PR applicants were particularly affected by CAQ reforms and resulting provincial-federal tensions. While delays are common in many Canadian immigration programs (Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Bergen, Hajjar, Larios, Nakache, Bhuyan and Hanley2023), they became considerably longer for Quebec applicants at the federal level in comparison to previous cohortsFootnote 6 and to similar two-step PR applicants in the rest of Canada. Footnote 7 Such delays were said to result from the pandemic, a “pause” in the federal processing of new applications from the province in 2019, and, most significantly, from Quebec's reduced PR admissions targets, which were not followed by reduced selections at the provincial level. Faced with criticisms, the federal and Quebec governments deflected the blame on the other (Schué, Reference Schué2020). While those delays were reduced in subsequent years, they remain longer for Quebec applicants compared to applicants in similar programs in the rest of Canada. This sequence illustrates the consequences that federal-provincial tensions over policy areas might have on individuals.

Therefore, the case of Quebec warrants a closer examination to better understand the implications of the Canadian asymmetrical model of immigration federalism, especially in a context of rising federal-provincial tensions over this policy matter.

Precarious Legal Status and the Federalised Two-step PR

Scholars have demonstrated that temporary residence permits produce varying forms of precariousness (Rajkumar et al., Reference Rajkumar, Berkowitz, Vosko, Preston and Robert Latham2012; Vosko, Reference Vosko2023), to the point that temporary residence is increasingly considered as a “precarious legal status” (Goldring et al., Reference Goldring, Berinstein and Bernhard2009). Temporary residence permits constrain migrants’ margins of choices—that is, the space in which someone can make choices—in all of their life spheres (education, profession, migration and so forth) to various degrees, depending on characteristics which might regulate conditions of access to the labour market, education, geographic mobility, family reunification and access to secure residence status. Temporary migrants might find it difficult to plan for the future due to their permits’ limited duration and the uncertainty of maintaining a legal residence status (Rajkumar et al., Reference Rajkumar, Berkowitz, Vosko, Preston and Robert Latham2012). Furthermore, encounters with bureaucratic timeframes, such as application processing delays, produce a “temporality of indeterminacy” common to migrants dependent on bureaucracies’ decisions, including federalised two-step PR applicants (Bélanger et al., Reference Bélanger, Myriam Ouellet and Fleury2023; Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Bergen, Hajjar, Larios, Nakache, Bhuyan and Hanley2023). This affects their temporal engagement (Brunner et al., Reference Brunner, Karki, Valizadeh, Shokirova and Coustere2024; Dennler, Reference Dennler2021; Nourpanah, Reference Nourpanah2021).

To understand how the uncertainty stemming from the federalized two-step migration process affects temporary migrants, we also mobilize a life course approach, which examines the loose relationship between individual biographies and social-historical contexts (Elder et al., Reference Mortimer, Shanahan, Elder and Kirkpatrick2003; Wingens et al., Reference Wingens, Windzio, de Valk and Aybek2011). By considering together different temporalities; social, institutional and historical contexts; as well as linked lives and agency, a life course approach provides useful tools to comprehend how people's agentic negotiation of constraints affects their life course. One of these tools is the concept of trajectory, defined as the temporal representation of interwoven spheres of life. We utilize it to better analyze how going through a federalized two-step PR transition in Quebec affects applicants’ life courses and their ability to make changes in their various trajectories, called transitions. We posit that the migration trajectory, and especially its legal residence status subtrajectory (Goldring, Reference Goldring2022), is central to migrants’ life courses because it ties deeply, and in different ways, all life trajectories as well as aspirations to the migration trajectory (Coustere et al., Reference Coustere, Fleury and Bélanger2021). Goldring offered the notion of “work of legal status” to capture the agentic work performed by migrants trying to gain a secure residence status, which includes the time, money, learning, and social navigation engaged in this process (Reference Goldring2022: 464). Such a conceptual framework allows us to understand how migrants negotiate the federalized two-step PR transition—working to obtain a secure residence status in the context of a precarious temporary status—and how such a negotiation affects their life course and aspirations in all life spheres.

Methodology

Qualitative longitudinal research “endeavours to understand how people successively make meaning about the trajectories of their lives, or specific conditions of their lives, by following them through time” (Hermanowicz, Reference Hermanowicz2016: 491). This diachronic approach facilitates the reconstruction of life trajectories and the analysis of shifting meanings almost as they occur, providing an advantageous lens into processes of change, such as precarization (Hélardot, Reference Hélardot2005) and migration (Salamońska, Reference Salamońska, Vlase and Voicu2018), which a retrospective approach might be less well equipped to capture. We therefore employed it to study temporary migrants’ migration and professional experiences in Quebec, Canada. In 2019, 2020 and 2022, we did repeat in-depth interviews with twenty-two migrants, all of whom had recently worked in the hospitality sector in Quebec while on a temporary resident status in 2019.Footnote 8 To recruit these participants and allow for a variety of profiles, we advertised our study through social media, university student associations, and NGOs providing services to migrants, in addition to employing a snowball sampling strategy. While most came to Canada with no intention to get PR, by the end of the fieldwork, fourteen had started the application process of transitioning to PR, three were trying to become eligible for the Quebec pathway of transition to PR, and three had definitively left the country. For this article, we focused our analysis on the fourteen people who went through part or all of the bureaucratic process of transitioning to PR. Apart from two who had obtained PR shortly before the first interview,Footnote 9 most went through the PR application process during the fieldwork. The small number of people interviewed as well as their initial recruitment based on employment in the hospitality sector is one limitation of the study. However, consistent with a qualitative approach, the research did not intend to be representative, but rather to collect rich data to better understand a phenomenon and conceptualize it through a process of “grounded theorization” (Paillé, Reference Paillé and Santiago Delefosse2017).

Informed by the life course approach, the interviews focused on participants’ past professional and migration experiences before Canada, as well as their general experience holding a temporary permit or PR (when applicable) in Quebec and their aspirations in various life spheres. Topics included their professional, relational, educational, and housing experiences, as well as their access to services, their bureaucratic encounters with the administration to maintain a temporary status or get a secure residence status, and their negotiation of the consequences of the pandemic in a foreign, institutional context.

The participants were eight women and six men who were nineteen to thirty-two years old at the time of their arrival in Canada, between 2013 and 2018. They came from France (8),Footnote 10 Mexico (3), Brazil, Italy, and Belgium (1 each), and they started their sojourn with a working holiday visa (7), a study permit (3), a closed-work permit (1 young professional, 1 temporary foreign worker), or as a tourist (1). Nine of them were native French speakers. The participants can be described as “middling migrants” that are “very much of the middle” within their countries of origin and of migration (Conradson and Latham, Reference Conradson and Latham2005: 229). They moved to travel, work, study or settle abroad, benefitting from relatively accessible residence permits due to their nationality or financial standing. Once in Canada, most developed a migration project to get PR—which does not always translate into wanting to settle in Quebec or Canada—yet encountered difficulties fulfilling this aspiration. During their sojourn, they went through different types of precarious legal situations, ranging from holding a succession of temporary residence permits to not having a status at all.

The Federalisation of Inclusion

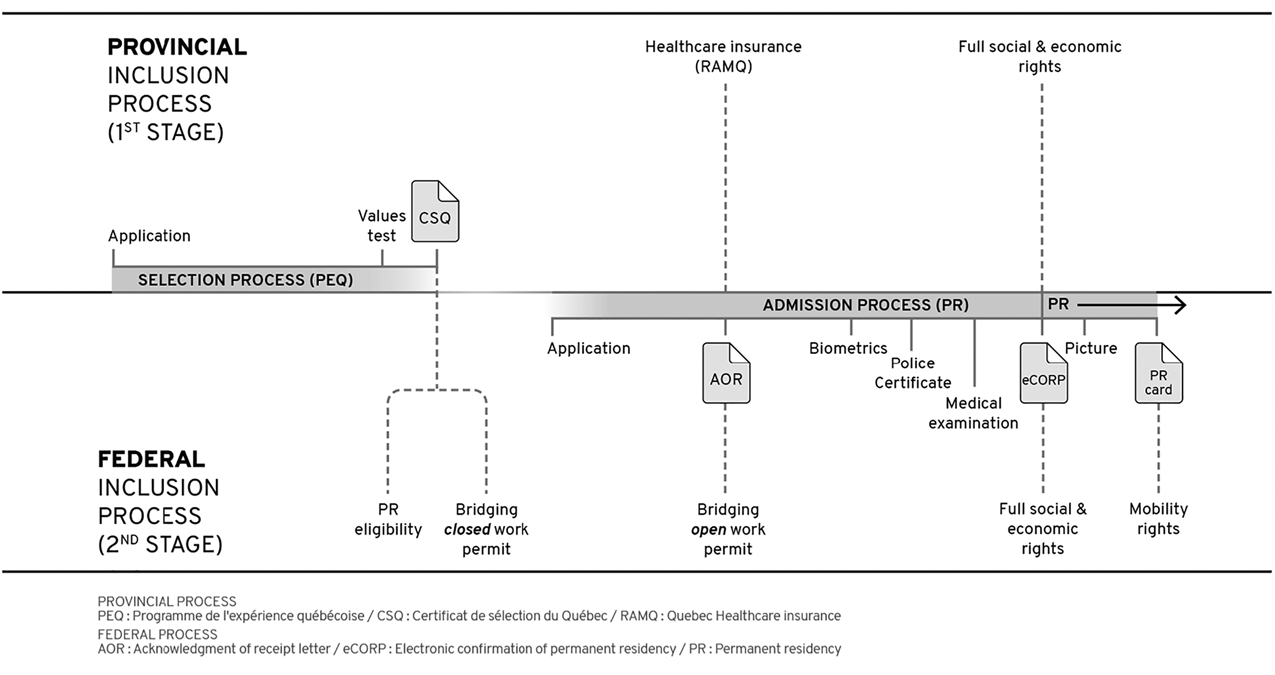

Waiting was central to applicants’ temporal experience of transitioning to PR (Robertson, Reference Robertson2013). However, it was also a dynamic process. It can be modelled as a succession of two stages (the provincial and the federal application processes), each phased by successive steps that signal an advancement in the application processing or require an application's action to advance it. Some of those steps constitute inclusion milestones materialized by the unlocking of rights at the provincial or federal level, which forms a federalized process of inclusion—what we refer to as a “double inclusion” process (See Figure 1). Indeed, the analysis showed that this administrative process is not limited to the selection and admission of permanent residents, but also gradually increases their inclusion by increasing their access to economic and social rights. This is especially relevant because (1) temporary residents have limited rights, and (2) they are typically excluded from settlement and integration programs, including in Quebec, despite recent improvements in that regard (Oeschlin and Bélanger, 2023).

Figure 1. Federalised two-step migration as an administrative process of federalised inclusionFootnote 11

The first stage is the provincial selection process. Applicants to two-step PR transition programs in Quebec must first become eligibleFootnote 12 and apply to the Programme de l'expérience Québécoise (PEQ). If selected, they receive the Certificat de selection du Québec (CSQ), which allows them to apply for PR at the federal level. Once submitted, this application takes a few weeks to half a year to be processed—a period of waiting filled with administrative processing interactions, like requests to provide clarifications or additional documents.

Since 2020, there is also an added step to pass: an “attestation of learning about the democratic values and Québec,” colloquially called a “values test,” to ensure applicants’ adhesion to Quebec “values.”Footnote 13 With a 99.93 per cent success rate in 2022, it appears more symbolic than selective (Lajoie, Reference Lajoie2022). Introduced by the CAQ government, this test represents an attempt at “framing the nationhood content” (Laxer, Reference Laxer2020: 127, emphasis in the original) in terms of values instead of rights (Laxer, Reference Laxer2020: 130). In trajectories of transition to PR, this test further signals to applicants that they are going through a process of inclusion in the province.

Successful applicants then get the CSQ, an inclusion milestone, which unlocks two rights. First, it allows applicants to apply for PR at the federal level, the next stage of this double inclusion process. Second, CSQ holders are eligible for a simplifiedFootnote 14 bridging closed-work permit issued by the federal government. Like other milestones, however, its significance in migrants’ trajectories varies depending on the economic and social rights already provided by the temporary residence permit held (for example, open vs. restricted labour market access, or provincial health insurance eligibility). Still, it signals their greater inclusion in Québec and Canada by facilitating their maintenance of a legal residence status.

As shown in the diagram, the second stage is federal admission. With the CSQ, temporary migrants are eligible for PR without needing to get through another selection process. A few months after they apply, applicants get an acknowledgement of receipt letter (AOR) which confirms that the application has been received and is complete. It is an important inclusion milestone into both Quebec and Canada. It signals further provincial social inclusion by unlocking the right to provincial health insurance (RAMQ). This is significant because not all temporary migrants in Quebec are eligible for such health insurance, a situation which varies depending on the province as healthcare is a provincial jurisdiction. At the time of fieldwork, AORs took months to be issued due to federal processing delays affecting Quebec applicants, leaving them in limbo. They did not know whether their application would be sent back as incomplete and did not have access to the rights opened up to them by AOR, delaying their inclusion process. The AOR also unlocks another kind of federal bridging work permit, and thus allows for a change of employer—signalling further economic inclusion into the province and Canada. This permit, which was already accessible to PR applicants in the rest of Canada, was only made accessible to Quebec applicants in 2021.

There are then successive steps that applicants are invited to take to advance the application process: biometrics data submission, medical examination, and police certificate provision. Each step can be difficult to complete. Applicants are given a short window of time (Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Bergen, Hajjar, Larios, Nakache, Bhuyan and Hanley2023), which might not be sufficient to get an appointment for biometrics, an appointment with an Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) approved physician, or police certificates from foreign administration(s). Successful applicants then receive an electronic confirmation of PR (eCORP), which constitutes proof of the new residence status, effectively cancelling their former temporary permit. It is a major inclusion milestone, but not a travel document. To get their PR cards, which is the last inclusion milestone of the process, new permanent residents must provide their picture. At the time of the fieldwork, PR card issuing processing delays were taking months, immobilizing new permanent residents in Canada while they waited for their PR card. Indeed, as their temporary permit is cancelled upon receiving the eCORP, they have no travel document to go back to Canada if they leaveFootnote 15—thus temporarily withdrawing their international mobility right. Significantly, at every application stage, frequent errors—both technical and human—often make the process more arduous.

The share of prerogatives over the administrative process of selection seems clearly delineated, with a provincial application stage preceding the federal one. However, the inclusion process is more entangled, with federal rights counterintuitively opened at the provincial stage. The unlocking of a federal right at a provincial milestone signals a federal recognition of Quebec's selection power by providing greater economic rights (and inclusion) to CSQ holders, which facilitates both the inclusion process into the province (as it is expected that applicants will work in Quebec) and into Canada. Conversely, access to a provincial right (RAMQ) at the federal stage of application further contributes to the apparent entanglement of the federalized inclusion process. The rhythm of the inclusion process varies amongst migrants, as temporary residence permits grant differing rights. Still, it formally leads to greater inclusion into both the province and Canada, reflecting provincial-federal cooperation. Finally, the model presented is unique to Quebec insofar as it includes its distinct policies of inclusion (for instance, a values test, healthcare access policies for temporary migrants, arrangements with the federal government regarding bridging work permits) but can serve as a basis to analyze similar two-step pathways to PR in other provinces.

Precarized Trajectories of Inclusion

This federalized process of inclusion contributes to precarizing Quebec applicants in two-step migration due to its administrative complexity and the consequences of provincial and federal dissonances. Notably, based on the analysis of our interview data, being a native speaker of French did not seem to either facilitate or complexify this process.

There are three layers of complexity for applicants in Quebec's federalized two-step PR process. The first stems from the need to complete two applications with distinct requirements as part of the transition process. Participants usually considered the provincial application to be easy, even “very easy” (LinaFootnote 16), compared to the federal one, which involves more documents to gather and complete. However, many faced challenges at both levels of applications. While application guidelines provided by both levels of government are available online, participants often reported that the information was not detailed nor clear enough, leading to mistakes, such as using the wrong pen colour for a manual signature. Those grey zones left a margin of interpretation, both for the applicants who had to adequately respond to the implicit and explicit guidelines and for the agent examining the file. Additional information or documents required might result from a conflict of interpretation that the applicant must resolve through extra work, as Chloé recalled about her provincial application:

of the 52 weeks [you have to prove to be eligible], the number of weeks with more than 30 hours that you have to justify, I had 4 at 29h. I counted them! […] I think they can include them anyway. And at first, they didn't want to, so I had to send them a GIGANTIC letter to explain HOW and WHY! […] I work in the restaurant business, so it's HARD to get stable hours. But you want that, I'll show you, I've got 85 pay slips! And some have 10 hours, some have 60!

This frequent back-and-forth with the administration increased the duration of the application process. Additionally, mistakes sometimes led to an application refusal, compelling the applicants to start again and adding a financial costFootnote 17 to the “learning cost” of the process (Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Bergen, Hajjar, Larios, Nakache, Bhuyan and Hanley2023).

The second layer of complexity stems from the simultaneous “double race” (Nourpanah, Reference Nourpanah2021: 17), which was run by applicants trying to get PR and to maintain a valid residence status. As a result of long processing times, most had to get their residence permit renewed or changed at least once during the transition process, adding to the work of status performed by applicants. Furthermore, these delays amplify the risk that the application processing time exceeds the temporary permit duration. In such cases, applicants’ status in Canada is known as “maintained status,” which provides the right to legally remain “under the same conditions” in Canada while their residence status application renewal is processed “only as long as the person remains in Canada” (Government of Canada, 2022). It is quite precarious, but in theory, applicants’ rights are maintained. However, since many social rights are a provincial prerogative, such continuity depends on the provinces. In Quebec, migrants on maintained status that have access to provincial health insurance lose it, illustrating the lived consequences of a dissonance in the federalized management of immigration, which can create a gap between formal and actual rights depending on the province. This is significant, as being on maintained status is a common experience for migrants. Most participants experienced it at least once during their temporary experience in Quebec, costing them holidays and attendance at important family events (as they did not dare to leave) and professional opportunities (as employers felt that it was a grey area), and causing them to worry over losing their healthcare:

Maintained status, we didn't really know if it was legal or not […] if the baby had an illness, we weren't covered for anything. (Claire)

Finally, the third layer of complexity results from the articulation between both processes—transitioning to PR and maintaining a legal residence status. As demonstrated in the previous section, those two processes are interlinked. For instance, the CSQ, a provincial document indicating eligibility for PR, grants the right to a federal bridging work permit, which is useful to maintain a legal residence status. This articulation inflates the risks that the transition process will affect the migration trajectory, as illustrated by Chloé's story. About six months before the end of her work permit, she applied to the provincial stage of the two-step PR transition (PEQ). Processing delays were short at the time, so she waited for the CSQ before applying to a closed work bridging work permit with her employer. However, an attempted reform of the PEQ shortly after she applied increased application processing times, putting her at risk of remaining without any residence status:

It's been a loooong ordeal! The CSQ [application processing time] lasted 4 months, it's supposed to last 6 weeks, but in fact, the file fell into a limbo when the law changed. So between the time it froze and the time they handed it in, 3 weeks went by, except that at that point I only had 3 weeks left on my visa!

Luckily, with the support of her provincial constituency office, she received the CSQ in time, preventing a loss of status which would have affected her professional and migration trajectories with risks of spillover into her whole life course.

Finally, the layer of complexity produced by the articulation further increases the level of expertise required of applicants who need to understand the distribution of provincial-federal prerogatives and their articulation to correctly navigate the transition process. For instance, many participants did not clearly grasp what the exact purpose of the CSQ was. In many cases, it did not affect their decisions. Valérie, however, mistook it for maintained status:

I thought that at first, the CSQ gave you the famous maintained status. And that's when the lawyer told me “no no, the federal is the federal, and the provincial is the provincial.” I said “okay, I didn't get it at all.”

Such a misunderstanding had a major consequence, as she remained in Quebec and worked without a legal residence status following the end of a temporary residence permit. This long and stressful period affected her professional plans and finances. Her mistake may not be unique, as Valérie recounts meeting other people with the same misconception. To avoid those pitfalls, applicants tried to get formal information and support, but getting in contact with, or non-contradictory information from, immigration officers proved difficult (Bélanger et al., Reference Bélanger, Myriam Ouellet and Fleury2023; Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Bergen, Hajjar, Larios, Nakache, Bhuyan and Hanley2023). Therefore, participants resorted to other sources. The most widely used were at-hand and free informal sources, such as friends, websites and online forums, and thematic Facebook groups. It provided participants with contextualized information and a better overview of the application processing dynamics. While useful, this informal information is also subjective and sometimes inaccurate, obsolete or not applicable to all cases. Pondering its value and applicability requires further work and knowledge. Consequently, to avoid mistakes and correctly interpret explicit and implicit administrative requirements, applicants must become experts through a highly time-consuming process of “hyper-bureaucratic vigilance” (Bélanger et al., Reference Bélanger, Myriam Ouellet and Fleury2023), and learning on-the-go, which becomes part of the work of status to perform:

So it's full of little details that if you don't follow the forums, and it takes time, it takes a crazy amount of time on top of… Well, you can, you can make a mistake and find yourself really stuck at the border. (Camille)

To overcome these issues, applicants also relied on another category of formal sources: professional intermediaries. Some are free of charge, such as federal and provincial members of parliament's constituency offices. Others, like immigration consultants and lawyers, have a cost and were especially sought after for their application support services. Participants stated that they decided to rely on an expensive intermediary because their case was complex, to correctly run the “double run” and to navigate the complexity of the federalized two-step process, given long processing times stemming from its federalization:

It's just that it's such a big, complex file, that I was afraid to do it, because of all the documents that I have to send and might forgot might slow the process further down, and [PR] is already a 2-year wait.

We didn't want to have the same problem as with the CSQ. So, we preferred to take the initiative to get a lawyer [for PR].

Even though most participants felt that this support was crucial for the success of their application, some were penalised by mistakes committed by their intermediary's. In sum, the “mere” need the make two bureaucratic steps at two levels of government instead of one increases the complexity of the work of status, multiplying the risks of errors and thus delays or denied applications with consequences for participants’ life courses. Additionally, provincial-federal tensions affect the duration of the process, increasing the risk of precarization and in turn, the need to resort to formal and informal sources of information and support with mixed results. Therefore, those complexities are produced by (1) the federalized form of the two-step process and related social and immigration policies, and (2) the politicization of the process at the provincial level, which affects delays. In comparison, PNP applicants in provinces outside Quebec face the same layers of complexities, given the similar federalized two-step migration process—yet without the consequences of federal-provincial conflicts such as in Quebec.

Mixed Feelings of Inclusion

While the transition process includes periods of intense activity to gather the documents and meet deadlines, most of the applicants’ time was spent waiting for the administration's answer or further requests, especially at the federal level where processing times are counted in years. This temporal experience produced a range of emotional experiences, affecting participants’ feelings of inclusion.

Right after applying at the provincial and then the federal level, participants mostly felt relief at having completed this work, and acceptance that they had to wait. However, at the time of the fieldwork, delays were growing longer than anticipated with no end in sight, producing stress and anxiety:

It's a daily thing. You get up, you think about it, you go to bed, you think about it, and it becomes almost obsessive in fact, because it's long, it's so long. You don't want to be one of those people who wait 28, 32 months. 37 months.

For many, such uncertainty permeated their whole life. They felt like the present was suspended because the future was uncertain:

I'd tell you that I'm, I'm, I'm swimming in the unknown right now. (federal application)

I used to plan a future like, when you asked me about the two-year career, I had a plan. I don't have it anymore! Actually, I cancelled it. […] Why do start planning if we don't even know what's going to happen in the future? (provincial application)

This uncertainty contrasted with their previous understanding of the transition process. Many had heard the federal and provincial discourses advertising the possibility of two-step PR transition, leading them to believe that it would be relatively easy. One French participant, determined to settle in Quebec and confident in her ability to be getting PR, even bought a house as a temporary migrant. She later regretted it as she experienced a long, difficult, and precarious transition to PR, further complicated by the difficulty in maintaining a valid residence status. Discouraged, she contemplated giving up on her migration project as her latest temporary work permit application had been refused:

I thought at one point I'd stop everything and go home. Like completely. I said “too bad, they'll have filled their pockets with my money […] too bad for the money we'll have lost, I mean, if they don't want us, it's because they don't want us…” I thought about it. (Valérie)

Another participant, Joaquin, stopped emotionally investing in the PR outcome due to issues stemming from the precariousness of his temporary residence permits and the complexity of the multilevel PR transition:

For example, in my case, I am no longer interested in the residency answer, I am simply interested in getting an answer. Yes or no. I don't care which one. Why? Because I have already spent seven years of my life here. Before, I was telling myself that I was investing time, but I am really spending it because Quebec is not allowing me to move forward at any time, and neither is Canada.

Research suggests that those “uncertainties” and “ambivalences” are common for temporary migrants experiencing a two-step migration process, including before applying to PR (Brunner et al., Reference Brunner, Karki, Valizadeh, Shokirova and Coustere2024). However, while the administrative process of federalized two-step migration formally appears as an inclusion process that could progressively reduce those feelings, our analysis suggests otherwise. The participants’ cases illustrate how the precariousness produced by the long and complex federalized two-step PR transition might affect feelings of inclusion. In fact, while most participants did not consider giving up on their migration project, many experienced contradictory feelings. Instead of undergoing progress towards a greater inclusion through the federalized process of two-step migration, they felt that the process was at odds with the inclusion they had experienced when they landed in the province, making them feel undesirable instead.

Counter-rhythmic Inclusion Process

The federalized inclusion process signals a progressive inclusion through the unlocking of rights at both levels that should be reflected in applicants’ lives and transitions. While many reported indeed feeling stuck during the process of transition to PR—whether geographically or in various life spheres—this feeling did not always quite match important transitions that applicants made in their life spheres at the same time.

Those transitions resulted partly from the unlocking of rights at different stages, which sometimes facilitated significant transitions and thus materialized the progressive inclusion promised. For instance, Felipe and his wife's temporary residence permit did not provide them with provincial health insurance, but they became eligible for it upon receiving the AOR. It constituted a turning point in their family trajectories, opening the possibility to try to have a child.

Such transitions also illustrate the ability to engage in the present and have a relative certainty about the future. Indeed, most participants believed that they would be granted PR once selected by Quebec. This confidence in the outcome of the federalized two-step PR transition seems to result from the fact that Quebec selects future PRs, making it the highest gate to cross:

There are not many problems anymore, since I already applied to residency, it is just a matter of getting it. Many people have already told me that if you have the CSQ, they have already accepted you.

Now I have a provincial permanent resident document [the CSQ].

I had an immigration lawyer who told me that normally if they give you your CSQ, Quebec or the federal government has no reason to say no to you. […] You only to wait for them to say yes, but at least they have no reason to say no if you haven't done anything criminal. That stuck with me.

Some still imagined the consequences of being refused PR, like Lina, who exclaimed: “It's true that it worries me in the sense that if it doesn't work [PR], you know, what are my alternatives? I don't have any. I want to stay! [laughs].” But this risk was not considered serious by most participants. In fact, Lina later recounted that she had invested in a pension fund. Rather than being uncertain with the PR transition's outcome, Quebec applicants were uncertain of its duration in a context of rising federal processing delays, which reduces the precariousness of their situation.

Still, most participants usually waited to make such important decisions as buying a house or becoming parents—not because of the risk of not getting PR, but because of the limited rights granted by their precarious temporary permits, combined with the uncertain duration of the PR transition process. Indeed, such precarious statuses limit work opportunities, since some work is only available to PRs and citizens; increases the cost of certain decisions—for example, tuition fees are higher for students with temporary residence—and reduces access to social protection.

Many expressed a deep feeling of relief, freedom and happiness upon receiving their RP confirmation. It brought improved rights and opportunities, and the end of a long administrative process and, for some, of a long migration trajectory. Signalling full membership, PR had the potential to affect people's migration project, like the couple who finally decided to settle in the province upon receiving PR despite their previous hesitations. However, some participants did not consider PR as a game changer, even when they were delaying transitions in various life courses in its expectation:

But [PR] didn't change anything! I think when we travel, it will make a difference. We'll get home quicker and yada yada but for living here, it hasn't changed anything, it's the same. We've got a document in my drawer that I don't need during the day, that's all.

Well… honestly, I don't think much of it [PR]. Just to buy the house. And stop doing paperwork. That's it! Because we've already got everything we could do except - well, vote, when you're a citizen.

This opinion reflects their “middling” privilege and resources, which can be materialized in “flexible” temporary residence permits (Akbar, Reference Akbar2022), as well as the progressive inclusion process, which unlocks rights before the obtention of PR. Therefore, the process of inclusion itself tends to reduce the significance of PR as an inclusion milestone.

Finally, while PR is a federal status which provides its holder with full social, economic and mobility rights across Canada, some who wanted to move to other provinces felt that they could not fully take advantage of the latter before getting citizenship, because they had been selected by Quebec:

your PR is still linked to your CSQ, that, I know. I've looked into it. But then, you can also prove that you want to live elsewhere in Canada […] And frankly, I don't recommend it because I've read a lot of people who were refused citizenship because in the end they didn't succeed.

And even if you have residency, you don't know if you can move to another province, because some people say yes, and some say no. So it's the same thing. So it's the same, it's not clear at all. You have lawyers telling you yes, no problem, and other lawyers telling you no. So you don't know. […] We wanted to continue in Quebec City. To get our citizenship, because PR isn't enough, because then you can't move to another province.

Well [citizenship] would make us free to live wherever we want, even to leave Quebec.

For those new permanent residents in Québec, PR signalled a full inclusion process to the province, rather than to Canada as a whole. It seems puzzling at first, because respecting the intention of settlement in the province of selection for PR is not a condition of eligibility for citizenship. However, we interpret the fear expressed as the result of repeatedly declaring the intent to stay in Quebec in both the provincial and federal applications, combined with the circulation of contradictory discourses from formal and informal sources, which produce an uncertainty that immobilizes those new permanent residents in Quebec. Indeed, part of their work of status during the transition process has been to learn to interpret unclear governmental requirements, to sort between relevant information and to be careful to avoid mistakes. Therefore, faced with an uncertainty surrounding interprovincial mobility, they chose to be careful to keep their hard-won settlement right. While this perception might change, citizenship appears to them as the stage to pass in order to achieve inclusion in Canadian society rather than in the province of selection only. In sum, the federalized two-step process of inclusion in Quebec seems to produce a counter-rhythmic inclusion process, with various gates to cross and in which PR may not be experienced as the most significant one.

Discussion

Based on the case of Quebec, we argue that federalized two-step migration is also a federalized process of inclusion. In other words, this administrative process sends a shared political message to applicants. Future permanent residents are to be progressively included into both the provincial and the federal societies through the acquisition of social and economic rights throughout the administrative process. This inclusion into both spaces is entangled: inclusion milestones at one level of application might materialize through new rights at the other level, producing a progressive access to rights throughout the process, which reflects a provincial-federal cooperation. This is significant, because integration and settlement policies tend to exclude temporary residents, including in Quebec (despite recent changes). Furthermore, as not all temporary migrants going through the process want to remain in Quebec or Canada, examining the inclusion effect of the process matters. In fact, our analysis argues that the administrative process of transition to PR plays an inclusion role.

Yet, the analysis of applicants’ experiences reveals a rather ambiguous inclusion process, stemming from its complexity and from provincial-federal tensions, which materialized within the administrative process. It directly affected applicants’ lives, producing feelings and experiences of exclusion with their life course becoming the location of those tensions. Such results are representative of a specific situation: the experience of federalized two-step migration in Quebec, at a time of rising polarization around immigration at the provincial level, which produces tensions with the federal level. The results would probably have been different if the study had been conducted a couple of years earlier when delays where much shorter. A distinct feature of the Quebec case at the time of the fieldwork, that is, provincial-federal dissent, significantly affected the results. Indeed, the delays it produces seriously amplify the complexities of the process, which increases risks of precarization, and applicants’ feelings of exclusion. Those delays result in great part from the fact the CAQ issued higher number of CSQs than its set PR admission targets, lengthening the application processing times at the federal level, which had to respect Quebec PR admission targets. This mismatch reflects a provincial policy gap between Quebec's selection policy and its admission target. Yet, as the federal government is responsible for granting PR within the limits of Quebec's admission target, the provincial policy gap played out on participants’ lives at the federal stage of application, producing a conflict between the federal and the provincial government for the responsibility of those delays.

This situation is rather unique in Canada because provinces outside of Quebec do not set their own provincial PR targets. However, they do determine levels of selected nominees through PNPs in cooperation with the federal government (Seidle, Reference Seidle2013). So far, those levels have aligned with the federal government’s own PR admission targets, and processing delays have been much lower than in Quebec. Yet Quebec's case suggests that while the determination of admission levels may be better suited at the subnational level (Thompson, Reference Thompson2011), misalignments between federal and provincial levels of PR admission for provincially selected candidates risks exacerbating the differences between the PR transition experiences of federally and provincially selected applicants—an hypothesis that should be further tested.

The federalization of the process undeniably increases its complexity, in a context of general bureaucratic complexity and opacity around immigration files processing (Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Bergen, Hajjar, Larios, Nakache, Bhuyan and Hanley2023), and with the added difficulty of maintaining a temporary residence status (Nourpanah, Reference Nourpanah2021). Such a situation is likely similar in other provinces and in countries in which subnational units participate in migrants’ selection (like Australia), with probable provincial variations in the type of risks produced by the complexity due to specific provincial social policies and migration programs’ reforms and should be explored by future research.

Furthermore, while we contend that PR is the main gate to full inclusion in Canada, the analysis suggests that the division between the PR selection process (at the provincial level) and the PR admission process (at the federal level) in federalized migration systems renders the provincial stage as the most important-yet-insufficient gate to cross to gain full membership, followed by a long and relatively precarious waiting time for full inclusion rights to be unlocked by PR. The analysis suggests as well that PR acquired through provincial selection is viewed as a provincial residency status. There are limits to this hypothesis, as the number of participants wishing to settle into another province was limited, and their perception of PR might change later. Still, their belief that citizenship is necessary in order for provincially selected permanent residents to move to another province demonstrates the performative effect of the applications’ requirements, further strengthened by contradictory discourses. While PR is conceived as a status providing membership into the federal state, the provincial selection instead produces a membership to the province first. As such, it is experienced as a more conditional status that does not grant full membership to Canada. Through federalised two-step migration, Quebec solidifies its provincial borders and nation-building, and keeps “challenging the actual boundaries and markers of citizenship” (Iacovino, Reference Iacovino, Hepburn and Zapata-Barrero2014; 101).

Such an observation is not limited to this province. In other provinces as well, federalized two-step programs require applicants to commit to settling in the selecting province in both stages of applications, even though the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms allows PR freedom of movement and settlement in any province. This application requirement attempts to facilitate their retention and thus contributes to their province-building aims (Seidle, Reference Seidle2013; Xhardez, Reference Xhardez2024). Yet, in both cases, the devolution of selection powers seems to produce two types of PR statuses, effectively raising provincial borders and destabilising the PR status. However, this situation does not appear to be the source of federal-provincial tension, showing that it meets federal goals as well.

Finally, this situation shows the precarious privilege of middling migrants in this space of uncertain desirability. While they usually benefit from flexible temporary residence permits and are among the limited number of temporary residents’ eligible for PR, they still need to prove their worthiness to be included permanently through a bureaucratic process that precarizes them. Yet, in a context of rising temporary residence admissions to Canada, granting provinces selection powers contributes to providing a fast PR pathway to people already contributing to Canada but ineligible for federal PR programs. In fact, our analysis does not infer that shared immigration selection prerogatives in Canada are generally dysfunctional from the point of view of migrants’ rights, concurring with most of the literature (Boushey and Luedtke, Reference Boushey and Luedtke2006; Spiro, Reference Spiro2001; Vineberg, Reference Vineberg, Baglay and Nakache2014). It rather points out a context (federal-provincial dissent, with the province pursuing a nation-building aim at odds with the federal aims), in a certain type of shared jurisdiction (devolution of selection power to the province, in cooperation with the federal level), which allows those dissents to be played out on migrants’ lives. In fact, the applicants did not lose rights but were often precarized by this dissent.

In sum there are two issues: first, the increasingly high number of people in Canada without full social, economic and residential rights, who are vulnerable to precarization, including when going through the process of getting a secure status; and second, the increased politicisation of immigration in Canada and federal-provincial tensions, which have significant repercussions on migrants’ lives in the current immigration federalism framework.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors have no competing interests or declarations to report.

Funding

This work was supported by the Quebec Research Funds – Society and Culture (FRQSC), the Équipe de recherche sur l'immigration au Québec et ailleurs (ÉRIQA), and the Centre de recherche Culture – Arts - Sociétés (CELAT).

Acknowledgment

A preliminary version of the argument developed in this article was presented at the 2023 ÉRIQA conference hosted by the ACFAS congress. We thank the participants who commented on this communication; Dr Lisa Brunner for her language editing and valuable questions, suggestions, and comments; and Sylvie St Jacques, who produced the figure. Finally, we also would like to thank the reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions which greatly improved the quality of the article.