Immediately after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, a Reuters journalist asked a Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) spokesperson, Hua Chunying 华春莹, “did the Chinese leader give his blessing for President Putin to attack Ukraine?” Hua replied with a barbed statement rather uncharacteristic of diplomatic rhetoric, saying, “I find such a way of questioning quite offensive, frankly speaking. It exposes a certain stereotype of looking at China with preconceived notions, bias, arrogance and malicious characterization.”Footnote 1 Such statements are often viewed in Western political and media circles as a manifestation of “wolf warrior diplomacy” (WWD, hereafter), a label used to describe the aggressive turn in Chinese diplomacy in the late 2010s, and one that is consistently eschewed by China.

WWD is widely seen as undiplomatic and counterproductive; it has been met with widespread criticism and spurred a concerted pushback from Western governments. The phrase has been used to describe an aggressive style of external communications (waixuan 外宣) that sees the so-called “wolf warrior” diplomats vociferously defending China’s position on issues while hitting back at any criticism of China’s domestic politics and foreign policy, often in strong terms.Footnote 2 Apart from diplomatic rhetoric, WWD has sometimes been used to describe China’s assertive, or in some cases coercive, foreign policy (waijiao 外交), whereby China leverages economic statecraft to force other countries to agree to Beijing’s demands. Our analysis focuses on the communicative aspect, which arguably is at the core of WWD.

The origins of “wolf warriorism” have been amply documented in research on Chinese diplomacy. Most analyses have attributed its rise to changes in China’s domestic politics and the international environment, including the personal preferences of President Xi Jinping 习近平, rising nationalism in China, and mounting criticism of China by its geopolitical rivals.Footnote 3 Without denying the causal significance of these factors, we add a piece to the puzzle by scaling down and focusing on a micro-level factor: aggressive journalistic questioning. The relevance of this factor is worth investigating given our focus on wolf warriorism as manifested in Chinese diplomatic rhetoric. We contend that aggressive questioning by foreign journalists is more likely to elicit an aggressive response by Chinese diplomats, particularly in a political climate characterized by increasing Western criticism of China.

Anecdotal evidence for this argument can be found in a narrative promoted by the MFA to counter criticism of China’s WWD: Chinese diplomats are not “wolf warriors” but are forced to “dance with the wolves.” For example, in May 2020, Wang Yi 王毅, the-then state councillor and foreign minister, underlined that China would “never pick a fight or bully others” but would “push back against any deliberate insult” and “refute all groundless slander.”Footnote 4 The narrative was further elaborated by spokesperson Hua Chunying at a press conference in December 2020: “[H]ow can anyone think China has no right to speak the truth while they have every right to slander, attack, smear and hurt China? … Do they think that China has no choice but the silence of the lambs while they are unscrupulously lashing out at the country with trumped-up charges?”Footnote 5 Most explicitly, Qin Gang 秦刚, China’s foreign minister from December 2022 to July 2023, emphatically stated in March 2023 that, “if faced with jackals or wolves, Chinese diplomats would have no choice but to confront them head-on.”Footnote 6 Wang, Hua and Qin are quoted here not to endorse their claims but to suggest that what was viewed by foreign audiences as aggressive was nothing other than a legitimate reaction from the perspective of the Chinese MFA. Stated alternatively, Chinese diplomats simply responded in kind. This lends support to our central claim that aggressive journalistic questioning is more likely to elicit an aggressive response from the Chinese MFA.

To empirically test our argument, we focus on the linguistic and interactional dynamics between foreign media and China’s diplomatic corps. Specifically, we analyse Chinese MFA press conferences, where foreign journalists and MFA spokespersons often engage in pointed exchanges on issues considered highly sensitive in China. Through a qualitative analysis of a total of 4,556 question–answer dyads spanning four years (March 2020—March 2024),Footnote 7 we not only uncover the intensity and variability of aggressiveness in foreign journalists’ questioning across different temporal and topic contexts, but we also assess the MFA spokespersons’ responses to determine the extent to which aggressive questioning elicits similarly aggressive replies.

In so doing, we contribute to the wider debates on Chinese diplomacy in two ways. First, our findings demonstrate the significance of aggressive journalistic questioning in the rise of wolf warriorism in Chinese diplomacy and underscore the need to study the interactional dynamics between Chinese diplomats and foreign actors when explaining China’s diplomatic practices. Second, our research draws insights from research on ad hominem attacks and provides a novel framework for dissecting China’s “undiplomatic” diplomatic rhetoric.

This article proceeds as follows. First, we review the literature on the factors contributing to the rise of wolf warriorism in Chinese diplomacy, with a view to situating our research. We then explicate how we understand and operationalize aggressiveness in foreign journalistic questioning and Chinese diplomatic rhetoric in this study. This is followed by a brief note on data and data analysis. We present our findings in two empirical sections: one focuses on aggressiveness in foreign journalistic questioning and one evaluates aggressiveness in MFA spokespersons’ responses. We conclude by summarizing our findings and discussing the implications of our study.

Situating the Research

Many argue that the assertive turn in Chinese diplomacy began in the wake of the 2008/09 global financial crisisFootnote 8 and accelerated after President Xi came to power in 2012.Footnote 9 However, the new combative and aggressive style of Chinese diplomacy did not materialize until the late 2010s.Footnote 10 Then, in the wake of the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan and the ensuing international blame targeting China,Footnote 11 WWD reached a crescendo.Footnote 12 It receded somewhat after mid-2021.Footnote 13 Owing to the widespread backlash it had generatedFootnote 14 and the increasingly vocal calls for restraint from high-profile career diplomats,Footnote 15 President Xi intervened. In a speech at a Politburo collective study session on 31 May 2021, he noted the need for those involved in external communications to be open and confident while remaining modest, with an eye to projecting “a reliable, admirable and respectable image of China.”Footnote 16 In the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Western criticism of China intensified once again. This gave rise to a surge of anti-Western sentiment in Chinese official rhetoric.Footnote 17 That said, the decision in January 2023 to assign former MFA spokesperson Zhao Lijian 赵立坚 to a much less prominent post signalled China’s effort to change course.Footnote 18

Given that WWD marks a clear break with China’s traditional diplomatic repertoire, many have discussed the factors that contributed to its rise. Here, we highlight two factors that feature in most analyses. The first concerns domestic sources, or rather, bottom-up and top-down political pressures. Nationalism is known to be a key force shaping the contours of Chinese foreign relations.Footnote 19 Under President Xi, popular nationalism is believed to have increased. Some argue that the popularity in China of Wolf Warrior II (the eponymous movie that inspired the term) can be attributed to its projection of “a strong nationalist sentiment through a series of stereotypes of China, the Global South and China’s position in the world.”Footnote 20 Meanwhile, China’s MFA had long been criticized domestically for being too conciliatory in defending China’s interests on the international stage.Footnote 21 As a result, the shift towards WWD may have been a calculated move on the part of the MFA to appease domestic nationalist forces.Footnote 22

Additionally, pressure on Chinese diplomats to act aggressively may have come from above. Over time, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has tightened its control over the MFA, a trend which has intensified under Xi.Footnote 23 Relatedly, China’s top leader has clearly expressed a preference for a more assertive approach in Chinese diplomacy, leading to a notable shift away from a strategy of “keeping a low profile” towards one of “striving for achievement.”Footnote 24 And, more recently, there has been an increased emphasis on “fighting spirit” in response to increasing international hostility.Footnote 25 In light of the tone set by Xi and adopted by the senior officials within the MFA, Chinese diplomats became “increasingly anxious to demonstrate that they are able to represent Xi’s vision and style on the global stage.”Footnote 26 Viewed in this context, the aggressive turn in China’s diplomacy could be viewed as a direct response to Xi’s stated preferences.

To be sure, there is an allure to explanations that point to domestic sources: for Chinese diplomats, the domestic audience matters just as much as, if not more than, the international audience. Yet, both bottom-up and top-down explanations fall short when accounting for the timing of the rise of WWD. There is little evidence of a dramatic change in China’s popular nationalism to drive the shift to WWD,Footnote 27 and privileging the role of political loyalty cannot satisfactorily explain why WWD emerged in the late 2010s and surged during COVID-19, given that the need to pledge loyalty remained a constant. Accounts focusing exclusively on domestic origins miss a significant part of the picture: the worsening international environment confronting China.

The second factor thus centres on foreign origins, namely (the perception of) a rising international hostility towards China. Given that China increasingly sees itself as locked in a political contest with the West, and that the CCP is acutely sensitive to any criticism that might threaten its legitimacy, some argue that it was the tidal wave of Western criticism directed at the party-state leadership and intensifying geopolitical rivalry that gave rise to WWD.Footnote 28 In this account, mounting censure of China by its geopolitical rivals entrenched a widely held belief among the Chinese leadership that the US and the West were bent on encircling, suppressing and containing China. The leadership reacted by adopting a tougher diplomatic posture. We contend that it is fair to emphasize the foreign origins of WWD, because the rise of wolf warriorism coincided with intensifying international criticism of China.

Building on the second explanation focusing on foreign origins, our research narrows the scope to the micro level and offers an account that emphasizes the impact of aggressive questioning by foreign journalists. We argue that aggressive journalistic questioning can, and often does, elicit an aggressive response from the MFA. As the main interface between the Chinese government and international audiences, the MFA speaks on behalf of many other Chinese actors (for example, the CCP and ministries)Footnote 29 and, consequently, bears the brunt of international criticism. From the MFA’s perspective, Chinese diplomats are oftentimes left with little choice but to “fight back … in the face of unscrupulous attacks, slanders and denigration.”Footnote 30 Many of these “attacks” originate in foreign media or are communicated to Chinese diplomats by the media. To assess the relevance of this micro-level factor, we first assess the aggressiveness of the questions put to MFA spokespersons during press conferences by foreign journalists. To that end, we draw insights from the literature on aggressive journalistic questioning.

Aggressiveness in Journalistic Questioning

Questioning public officials is part and parcel of journalistic practice and serves multiple purposes. It constitutes an important source of information, promotes transparency and accountability, and contributes to informed public debate.Footnote 31 Journalism can play a crucial watchdog role by holding public officials accountable to public interests; however, the tensions that can arise from this role can predispose journalists to adopt an aggressive stance towards officials, not least when government actions do not align with public demands. Aggressive questioning is commonly defined as a questioning style that is “hostile, verbally confrontational, adversarial, and contrary to civilized discourse.”Footnote 32 It manifests in different forms, with journalists trying to “criticize, apply pressure and construct situations that are difficult for the [questionee] to cope with.”Footnote 33

To assess aggressiveness in journalistic questioning, Steven Clayman and colleagues designed a composite measure comprising five indicators: initiative, directness, assertiveness, accountability and adversarialness.Footnote 34 Taking into consideration the setting of MFA press conferences, we omit initiative and directness, which concern aggressiveness as reflected in the manner in which a question is put.Footnote 35 Instead, we focus on the latter three indicators, which capture aggressiveness as evinced in the content of a question. Specifically, assertiveness exists when a question invites a particular answer and is opinionated rather than neutral; accountability is present when a question seeks explanation for specific policies or actions; and adversarialness is expressed when the preface of a question is oppositional or the question overall is suffused with an oppositional view.Footnote 36

It should be noted that this framework has been applied mostly to democratic settings to study interactional dynamics between media and public officeholders. This is understandable. Watchdog journalism and, by extension, aggressive questioning are decidedly less common in non-democratic countries because of the many constraints on press freedom and critical coverage.Footnote 37 Media regulation in China has intensified under President Xi, leaving little room for watchdog journalism.Footnote 38 That said, interactions between foreign journalists and the Chinese government are different. China-based foreign media are largely free from the constraints imposed on Chinese media and, consequently, can adopt an aggressive questioning style. Often, foreign journalists ask hardball questions on sensitive issues, which is typical of aggressive questioning. As such, the framework applied by Clayman and colleagues is useful for studying aggressive questioning at MFA press conferences.

The three indicators used in this study are all present in aggressive questions posed by foreign journalists during the period under study. For example, assertiveness is shown in the following question from Reuters: “With regard to China not allowing Canadian diplomats to attend the trials of Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, can you clarify that China is trying to say that its domestic law supersedes international agreement[s] like the Vienna Convention in this case?”Footnote 39 The question is specifically designed to invite a yes-type answer, which would require China to backpedal on its avowed position of adhering to international law and go against the general principle of the primacy of international law.

Accountability equally underpins some aggressive questions. The following question from NHK (Japan Broadcasting Corporation) is a case in point: “The Foreign Affairs Secretary of the Philippines said in a statement released yesterday that the award of the South China Sea arbitration is ‘final’ and ‘indisputable’ … China always advocates upholding the authority of the UN and international principles, why then does it reject this ruling?”Footnote 40 This question explicitly seeks an explanation from the MFA for why China, while being a party to and thus legally bound by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, refused to accept the ruling of the Hague tribunal on the South China Sea case.

Finally, adversarialness, in the form of staking out an oppositional position in the preface to a question or in the overall question, is particularly conspicuous when foreign media deploy critical language to describe China and its domestic and foreign policies. In this regard, China is often presented as an autocracy that prioritizes control and secrecy, with scant regard for human rights and civil liberties. For example, foreign journalists formulated questions in a way that seriously challenged the appropriateness of China’s domestic policies, including, inter alia, its response to the COVID-19 outbreak (and its delaying of the WHO investigation into the origins of COVID-19), “crimes against humanity and genocide against Muslim Uyghurs” in Xinjiang and the “systemic erosion of liberty and democracy” in Hong Kong. In foreign relations, China was depicted as an aggressive or malicious actor that sought to maximize its narrow interests to the detriment of others. Using this problematizing frame, foreign journalists asked MFA spokespersons to respond to political and media comments about China engaging in WWD, “vaccine diplomacy,” “hostage diplomacy”Footnote 41 and “debt trap diplomacy,” waging “economic warfare” against countries daring to defy Beijing politically (for example, Australia and Lithuania), sending a “spy balloon” to the US to gather intelligence, and backing Putin’s war in Ukraine. On a systemic level, such questions frame China as a threat to the leadership of the US, the world of liberal democracies and the rules-based international order. Examples of journalistic questions substantiating the preceding claims are provided in Appendix 1.

It is important to underline that we are not suggesting that foreign journalists were intent on portraying China in a negative light or that they should have been less aggressive towards the MFA or the Chinese government in general. Their aggressive questioning was largely rooted in their perceptions of certain Chinese actions at home and abroad, and reflected the concerns about and negative reactions to these actions within the international community. Moreover, aggressive questioning aligns with established journalistic norms and is a common feature of press conference settings. In the Chinese context, given the role of the foreign media and the media environment in China, such (aggressive) questioning by foreign media serves particularly important functions. That said, it was viewed rather negatively in Chinese officialdom. In response, Chinese diplomats sometimes used explicitly aggressive rhetoric, to which now we turn.

Aggressiveness in Chinese Diplomatic Rhetoric

Communication plays an essential role in diplomacy.Footnote 42 In general, aggressiveness does not (and should not) characterize diplomatic rhetoric, which prioritizes tact, civility, respect and reasonableness. Yet, the rise of WWD changed Chinese diplomacy and made it increasingly “undiplomatic,” notably in its external communications. How, then, to operationalize aggressiveness in this specific context?

Considering the broad consensus on the characteristics of WWD – being confrontational and combative – and its divergence from the assertive turn in Chinese diplomacy that preceded it, we consider and evaluate aggressiveness in Chinese diplomatic rhetoric as adversarialness. To capture the essence of WWD, we further unpack adversarialness along two dimensions: content and style. Content adversarialness involves expressing a view or position that is diametrically opposed to either the one explicitly articulated by the journalist or that which is implicitly embedded in the question. In this regard, it can be argued that there has been more continuity in Chinese diplomacy over the past decade than commonly assumed. Content adversarialness has increased in tandem with growing assertiveness in Chinese diplomacy since the early 2010s, especially in issue areas considered to be China’s “core interests” or those subjected to close international scrutiny.Footnote 43 Adversarialness in communicative style, on the other hand, refers to the use of emotionally evocative, caustic, inflammatory or outright hostile language. Its growing prevalence in Chinese diplomatic rhetoric has been widely cited as evidence of China’s WWD.

The convergence of content adversarialness and style adversarialness almost invariably results in ad hominem attacks, which may manifest in three distinct (although not mutually exclusive) variants: personal attacks that question the opponent’s “honesty, reliability, expertise, intelligence or good faith”; circumstantial attacks that seek to undercut the opponent’s credibility by “pointing out special circumstances pertaining to the opponent or suggesting self-interest on the part of the opponent that make the opponent’s arguments mere rationalizations”; and you too (“whataboutist”) attacks that accuse the opponent of similar faults and highlight the opponent’s hypocrisy and inconsistency.Footnote 44 Given that the three variants of ad hominem attack are easier to operationalize (than content and style adversarialness), we use them as indicators for aggressiveness in Chinese diplomatic rhetoric.

All three variants can be found in the answers of MFA spokespersons to aggressive journalistic questioning. For example, in response to a question citing the-then US secretary of state Michael Pompeo’s accusation that the CCP was committing “crimes against humanity and genocide” in Xinjiang, Hua Chunying mounted a blistering personal attack on Pompeo, characterizing him as “a notorious liar and cheater,” “a doomed clown” and “a joke of the century.”Footnote 45 More broadly, the MFA sought to dismiss China hawks and critics as “driven by ideological bias,” and in some extreme cases, as “possessed by such evil [that] they are on the brink of losing their mind[s].”Footnote 46

Resorting to the circumstantial variant of ad hominem attack was also common. For example, when responding to a question about whether China was engaging in “an economic blitzkrieg … to seize commanding heights of the global economy and overtake [the] US,” Hua Chunying emphasized the strategic calculus behind this political narrative. She dismissed it as an attempt to “smear and attack China,” “contain its development,” and turn “attacking China [into a] panacea to deal with every domestic political issue.”Footnote 47 Similarly, Canada’s decision to detain Huawei chief financial officer at the behest of the US Department of Justice was described as “an act designed to hobble Chinese high-tech companies.”Footnote 48

Lastly, whataboutist arguments also prominently featured in MFA spokespersons’ aggressive responses. A case in point is Zhao Lijian’s response to a question about whether China would agree that Russia had committed war crimes in Ukraine by killing civilians. Zhao went on a tirade about the “hypocrisy” and “double standards” of Western governments and media, stating: “I wonder if you were equally concerned about the civilian casualties in Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan and Palestine. Do these civilians mean nothing to you? Do not forget Serbia in 1999, or the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Did you show any care about civilian casualties there? If not, then you are in no position to make accusations against China.”Footnote 49

Similarly, in a response to a question about whether China constitutes “the most serious long-term challenge to the international order,” Wang Wenbin 汪文斌 pointed the finger at the US and enumerated its faults and inconsistencies on multiple fronts, including “always put[ting] its domestic law above international law,” “cherry-pick[ing] international rules as it sees fit,” “running a huge deficit in democracy and human rights,” pursuing “coercive diplomacy,” “creating ‘small cliques’ … to contain China” and “interfere[ing] in China’s internal affairs.”Footnote 50

Data and Method

Given our research aim, MFA press conferences serve as an ideal data source. They are not only comprehensive, systematic and readily available,Footnote 51 but more importantly, MFA spokespersons play a significant role in the discussion on China’s WWD.Footnote 52 As the public faces of WWD, their caustic comments are often used to substantiate claims about wolf warriorism in Chinese diplomacy.

Although a comprehensive Chinese MFA press conference corpus is publicly available,Footnote 53 we opted to build our own dataset for this research. We prefer transcripts in Chinese, as, in our view, they allow us to assess aggressiveness in MFA spokespersons’ responses more accurately.Footnote 54 Our dataset spans four years, starting on 24 March 2020 and ending in March 2024. Our choice of this starting date is by no means arbitrary; this is when the MFA first began disclosing information on the media organization behind each question. The practice has since continued, making it possible to distinguish between questions asked by foreign and Chinese media.

All press conference transcripts published during the four years were manually scraped from the MFA website.Footnote 55 Each transcript was further broken down into smaller data points based on the question–answer structure, with one data point representing one question–answer dyad.Footnote 56 In total, we gathered 5,644 question–answer dyads. Given our focus on aggressive questioning, we narrowed our focus further to media organizations from five countries: the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Japan and India. This decision was motivated by two considerations. First, media from these five countries asked 4,556 questions, accounting for about 81 per cent of the total number of questions. Second, these countries view China as a geopolitical rival, thus increasing the likelihood of their media engaging in aggressive questioning, or, at least, decreasing the likelihood of (especially state) media having to dampen their critical stance because of their home country’s close relations with China (for example, Russia, Pakistan). The 4,556 question–answer dyads constitute our data (a detailed breakdown is shown in Appendix 2).

Our data analysis followed a deductive approach. Based on the operational indicators discussed above, we parsed and manually coded all the question–answer dyads in our dataset. With regard to questions, we consider a question aggressive if at least one of the three indicators of aggressive journalistic questioning (assertiveness, adversarialness, accountability) is coded. As for answers, we consider an answer aggressive if at least one of the three variants of ad hominem attack (personal, circumstantial, whataboutist) is present. Of course, the actual coding process was more complicated. There were ambiguous cases, in both questions and answers, whose aggressiveness – or lack thereof – was not readily apparent. We critically discussed these cases with a view to further refining our operational understanding of the indicators and ensuring the vigour of our coding. In the following sections, we present the substantive results of our analysis.

Results

The question we aim to address in this study is: to what extent does aggressive questioning elicit an aggressive response? In the following two empirical sections, we first present findings about aggressiveness in foreign journalists’ questions and then demonstrate aggressiveness in MFA spokespersons’ answers.

Aggressiveness in journalistic questioning

The first finding concerns the intensity of aggressiveness in foreign journalistic questioning. Overall, about half (48 per cent) of the questions in our dataset are aggressive. This reflects the general level of watchdog journalism foreign journalists were practising vis-à-vis the Chinese government. The substantial share of non-aggressive questioning is attributable in large measure to the significant number of informational and confirmatory questions.Footnote 57 Typical questions falling under this category include those asking for information or confirmation about actions (to be) taken by China (for example, mitigation measures implemented by China to address COVID-19, overseas visits by Chinese leaders or officials), or bilateral or multilateral activities involving China (for example, high-level dialogues between China and other countries, China’s participation in multilateral conferences such as the G20 summits, and multilateral initiatives such as the Debt Service Suspension Initiative). These questions are overwhelmingly non-aggressive.

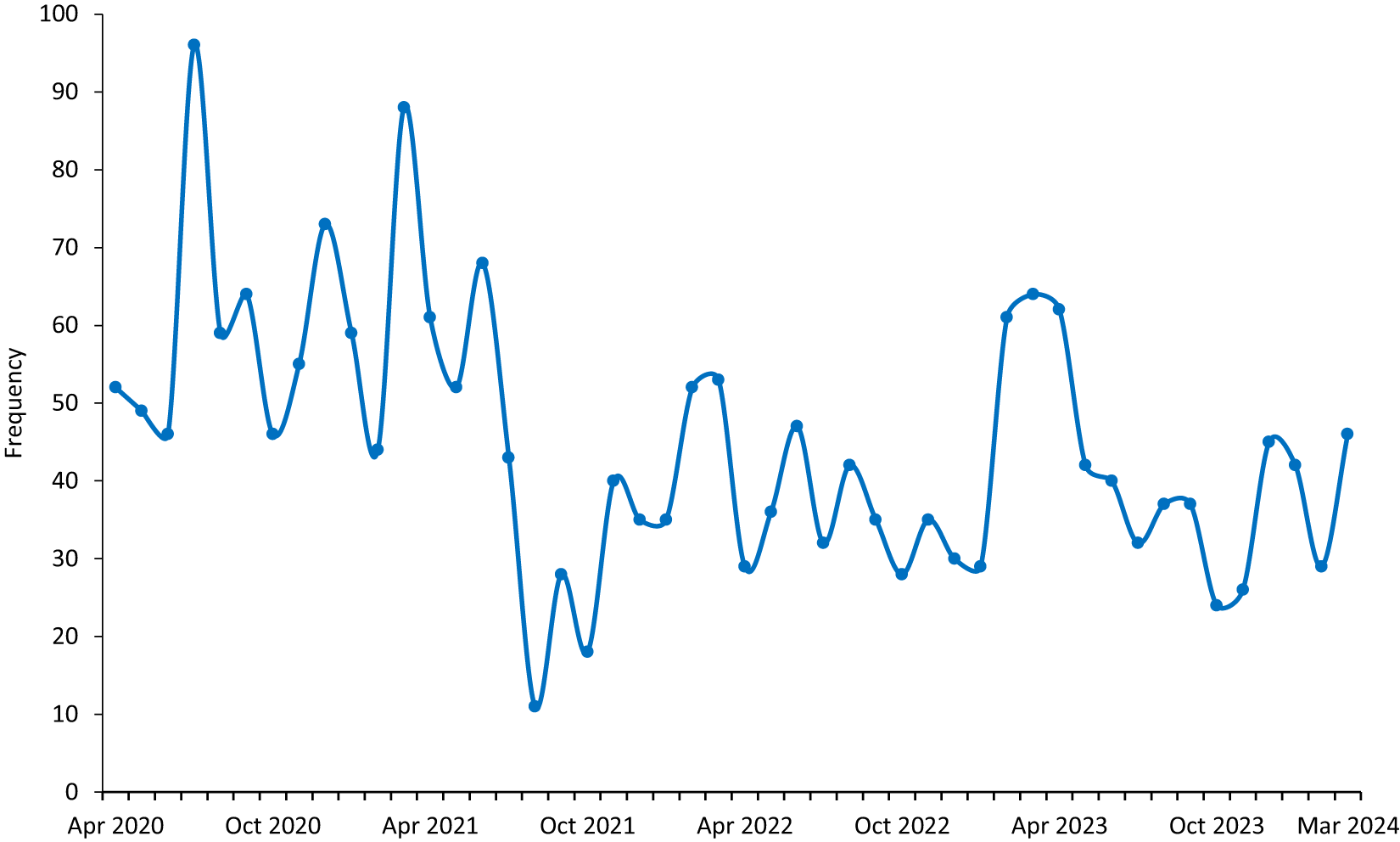

The distribution at the aggregate level may, nevertheless, be masking more nuanced underlying patterns across time and issue areas. The intensity of international criticism of China varied during the period under study. This is likely to be reflected in the interactions between foreign journalists and MFA spokespersons, because MFA spokespersons are frequently asked to comment on remarks critical of China made by foreign politicians, media outlets and policy pundits, and on the basis of that, to articulate China’s official position. Figure 1 shows the distribution of aggressive questioning month by month.Footnote 58 Two points are of note.

Figure 1. Temporal Distribution of Aggressive Questions

First, foreign journalistic aggressiveness was the most acute during (the early stage of) COVID-19. This is evidenced by the high frequency of aggressive questioning from April 2020 to June 2021.Footnote 59 A fair number of these aggressive questions focused on controversial issues relating to COVID-19 such as China’s early (mis)management of the outbreak, stringent containment and mitigation policy, alleged discrimination against Africans (leading to diplomatic complaints by several African countriesFootnote 60 ), closure of borders to international visitors, the origin-tracing of coronavirus and low efficacy of Chinese vaccines. That said, aggressive questioning during this period went well beyond COVID-19 and extended to a diverse array of issue areas, especially China’s fast-deteriorating political and economic relations with Western countries.

Second, foreign journalistic aggressiveness was amplified by notable political events. Owing to their political significance and newsworthiness, specific events managed to draw extensive media coverage and thereby became media hypes.Footnote 61 The peaks, as observed in Figure 1, attest to the effects of media-hype events on aggressive questioning. For example, the peak in July 2020 was attributable to the enactment of the National Security Law in Hong Kong on 30 June 2020, which generated international concern about the erosion of the city’s political autonomy and civic space; the peak in March 2021 was linked to the imposing of sanctions by the US, UK, Canada and the European Union on four Chinese senior officials in Xinjiang, on the grounds of their involvement in human rights abuses against the Muslim Uyghurs; the February–March 2022 peak can be explained by the growing international opprobrium of China’s tacit support for Putin following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine; and the peak in February–April 2023 can be traced to the “spy balloon” incident and ensuing political–diplomatic fallout between the US and China.Footnote 62

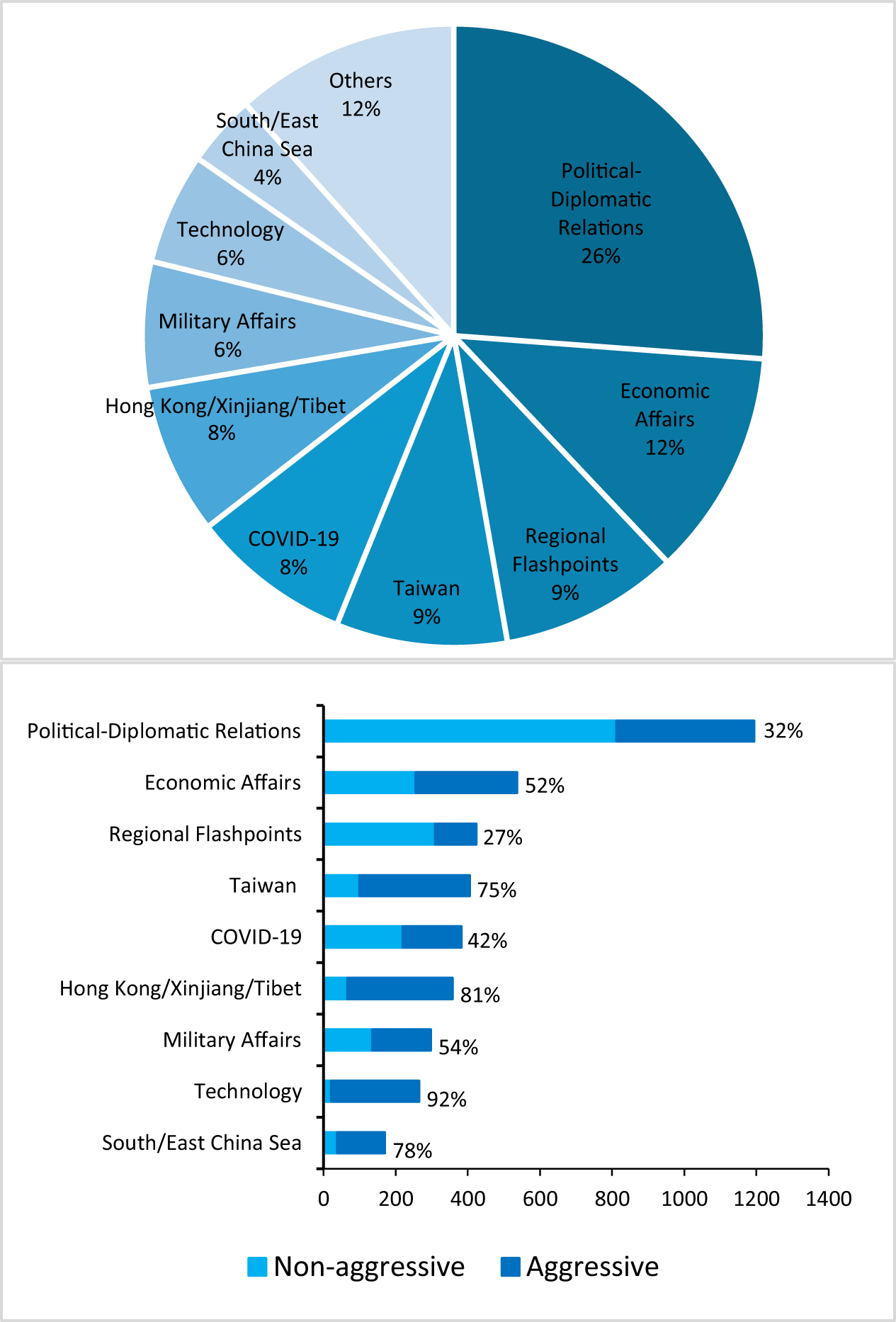

Figure 2 (top) shows the distribution of journalistic questions across issue areas.Footnote 63 There is a significant difference in issue salience, as reflected in the number of questions asked. Salient issue areas include China’s political relations and diplomatic activities with foreign countries, notably with the US and other Western governments, and with major international organizations; China’s economic-trade ties with other countries and outbound investments under the Belt and Road Initiative, and Chinese companies’ overseas operations; China’s position on regional flashpoints or conflicts in which China is not directly involved (for example, Ukraine war, Israel–Palestinian conflict, and nuclear tension on the Korean Peninsula). Issues relating to Taiwan, COVID-19, Hong Kong, Xinjiang and Tibet were also prominent in foreign journalistic questioning.Footnote 64

Figure 2. Distribution of (Aggressive and Non-aggressive) Questions across Issue Areas

Figure 2 (bottom) shows the distribution of (non-)aggressive questions across issue areas. We select issue areas that received the most questions, which collectively account for 88 per cent. Those in which aggressive questioning predominates (i.e. accounting for more than 75 per cent) include technology (92 per cent), Hong Kong, Xinjiang and Tibet (81 per cent), the South/East China Sea (78 per cent) and Taiwan (75 per cent). Except for technology, these issue areas have long been lightning rods for international criticism targeting China. The extraordinarily high level of aggressive questioning about technological issues, by contrast, stems from a confluence of events, and in particular, the rising role of technology in the intensifying US–China strategic competition and the actions taken by the US to outcompete China technologically. An overwhelming majority (70 per cent) of tech-related questions centred on the US and its key allies imposing tough technological restrictions on China (for example, the export controls on advanced semiconductor technology unveiled first by the US in October 2022, then followed by Japan and the Netherlands in 2023) and on Chinese tech companies (for example, restrictions on Huawei’s participation in building 5G networks in Europe). The prevailing media framing, in lockstep with the narrative promoted by the US and other Western governments, was that a technologically empowered China would pose a serious threat to the liberal world and that Chinese tech companies are merely “Trojan horses” doing the bidding of Beijing and therefore cannot be trusted.

Equally, China’s military affairs, including its military exercises and overseas military ambitions (for example, its plans to build overseas military bases), military clashes with India in the Galwan Valley, and nuclear arms control, were the subject of high levels of aggressive questioning (54 per cent). Further, aggressive questioning was fairly common in the economic domain (52 per cent), with particular attention paid to China’s strained trade relations with the US, the EU and Australia, its increasing primacy in international development finance and the associated adverse implications,Footnote 65 and the punitive or restrictive measures taken by various countries targeting Chinese commercial companies and investments.

Aggressiveness in MFA responses

This section turns to the receiving end and looks at MFA responses to foreign journalistic questions, both aggressive and non-aggressive.Footnote 66 Overall, 34 per cent (1,571 out of 4,556) of the responses were coded as aggressive. This is rather significant given that we only consider a response aggressive if it contains at least one of the three variants of ad hominem attack, and that a fair number of responses were non-substantive and were coded as non-aggressive.Footnote 67 The relatively common use of adversarial, caustic language in diplomatic rhetoric substantiates claims about China’s “undiplomatic diplomacy.”

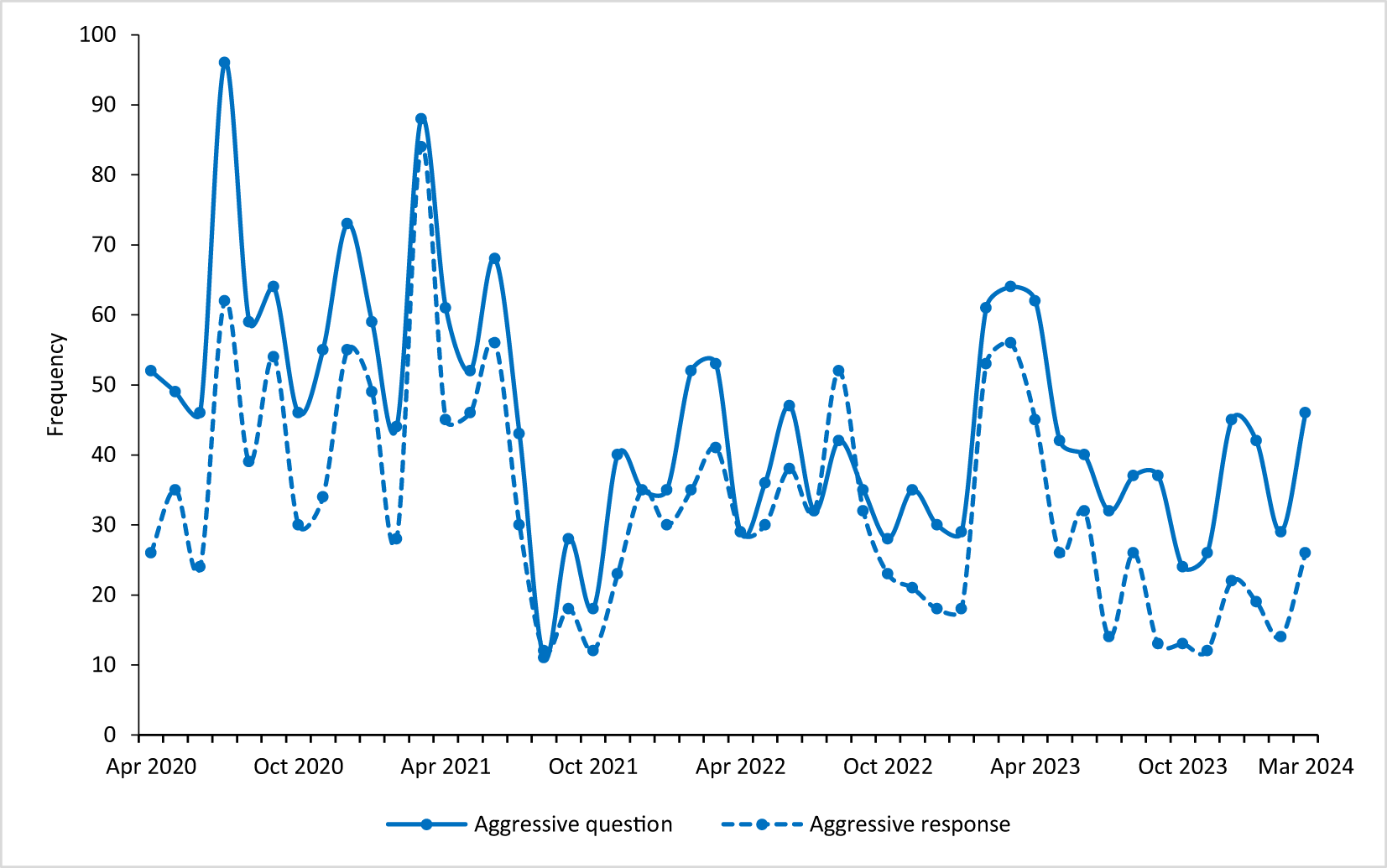

Figure 3 shows the distribution of MFA spokespersons’ aggressive responses, alongside aggressive journalistic questions, on a monthly basis. Two points stand out. First, aggressiveness in MFA spokespersons’ responses remained consistently high until June 2021; after that it trended downward. This supports prior research findings that China’s WWD reached a peak during 2020–2021 and has been receding since mid-2021.Footnote 68 That said, the aggressiveness of Chinese diplomatic rhetoric spikes quickly in response to intensifying international criticism, controversial political events, or a combination of both. This is borne out by the surge in aggressiveness in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Taiwan visit of Nancy Pelosi (the-then speaker of the US House of Representatives) and the “spy balloon” incident. It can thus be argued that while generally receding, WWD will resurface if circumstances warrant.

Figure 3. Temporal Distribution of Aggressive Responses and Aggressive Questions

Second, the aggressiveness of MFA spokespersons’ responses and that of foreign journalistic questions evolved in synchrony, lending support to our argument. A clear outlier is August 2022, when the aggressiveness of the MFA responses noticeably surpassed the aggressiveness of the questions asked, indicating that an atypically high number of non-aggressive questions elicited aggressive responses. Our underlying data reveal that Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan on 2 August considerably heightened tensions in both cross-Strait and US–China relations, provoking an exceptionally vigorous rhetorical response from China alongside a strong policy response, which included the launching of military exercises and suspension of military dialogues with the US.Footnote 69 When asked to comment on the visit one day after, spokesperson Hua Chunying accused the US of “collud[ing] with the ‘Taiwan independence’ forces” and “openly play[ing] with fire.”Footnote 70

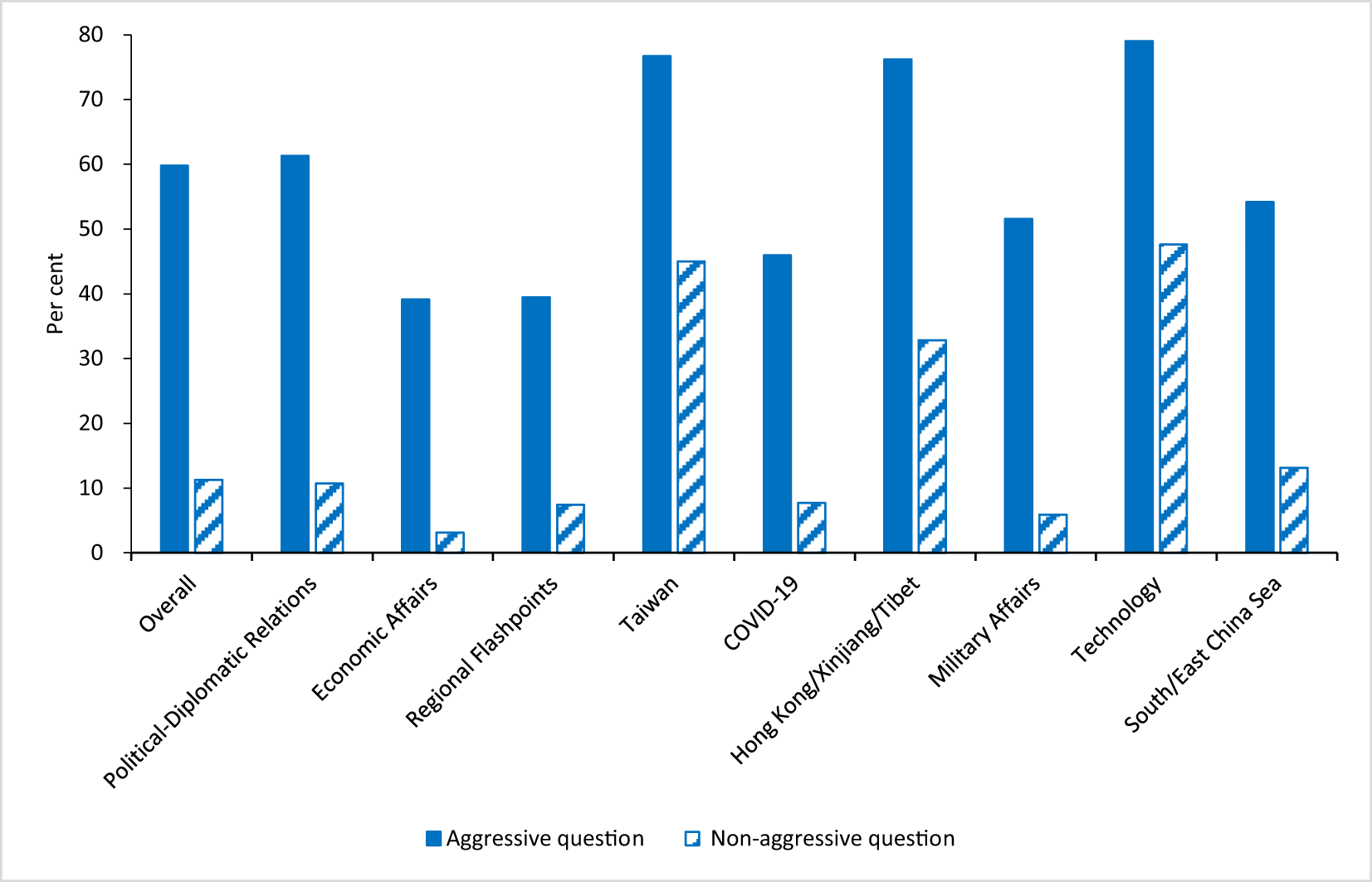

To assess more systematically the extent to which aggressive questioning was met with an aggressive response, we further narrow our focus to the subset of responses to aggressive questions. Figure 4 shows the results. In response to aggressive questions, 60 per cent (1,302 out of 2,178) of the responses exhibited aggressiveness, while only 11 per cent (269 out of 2,378) did so for non-aggressive questions. This indicates significant effects of aggressive questioning on aggressive responses.

Figure 4. Percentage of Aggressive Responses to (Non-)Aggressive Questions

Perhaps more importantly, the effect varies greatly across issue areas. Aggressive questions are highly likely to trigger aggressive responses in issue areas such as technology (79 per cent), Taiwan (77 per cent), and Hong Kong, Xinjiang and Tibet (76 per cent). Political–diplomatic relations (61 per cent), the South/East China Sea (54 per cent), and military affairs (52 per cent) are also issue areas where there is a high likelihood of aggressive questioning giving rise to an aggressive response. Notably, all of these issue areas, with the exception of political–diplomatic relations, are those where aggressive questioning predominates (see Figure 2).

Issues relating to Taiwan, Hong Kong, Xinjiang and Tibet, and the South/East China Sea have traditionally been viewed as part and parcel of China’s “core interests,” which focus on political stability, state sovereignty and territorial integrity, national reunification, and national security. These issues represent the “non-negotiable bottom lines of Chinese policy.”Footnote 71 This typically translates into high levels of rigidity and militancy on the part of the MFA.Footnote 72 For example, with regard to Taiwan, China maintains the position that all Taiwan-related affairs are purely domestic affairs and that any external interference in the form of assisting Taiwan in expanding its international diplomatic presence or impeding China’s reunification will absolutely not be countenanced. As such, aggressive questions on Taiwan are mostly met with equally, if not more, aggressive responses, or else dismissed altogether on the grounds that the MFA only deals with foreign affairs.

Regarding technology, in response to the increasing securitization of advanced technologies and the enactment of wide-ranging restrictions by the US in coordination with its Western allies, China actively promoted the narrative that the US was suppressing Chinese tech companies under the pretext of protecting national security and abusing its dominant position in certain tech sectors to contain China technologically and economically.Footnote 73 This narrative became a common refrain in the MFA spokespersons’ responses to aggressive questions on China-specific tech restrictions, as exemplified by US semiconductor export controls on China and restrictions on Huawei.

Results for the issue category of political–diplomatic relations are somewhat surprising. Non-aggressiveness characterizes the majority of the questions in this category (see Figure 2), and yet 61 per cent (233 out of 380) of aggressive questions that fell under this category triggered aggressive responses. A close examination of our data reveals that the dominance of non-aggressive questioning is owing to a significant share of informational questions about diplomatic events; in contrast, the high likelihood of aggressive questioning eliciting aggressive responses largely reflects the escalatory spiral between China and the US and its Western allies during the period under study.

Conclusion

Research into the origins of WWD has largely focused on Chinese diplomacy in the Xi era. While prior studies have emphasized foreign influences, our investigation shifts focus to a more granular aspect: the impact of aggressive questioning by journalists. To highlight how this affects the assertiveness in Chinese diplomatic language, we analyse the linguistic and interactional patterns between foreign journalists and spokespersons from the MFA. We have collected and examined a dataset of 4,556 question–answer dyads taken from MFA press conferences. Our findings strongly suggest that aggressive questioning plays a significant role, as indicated by the notably increased aggressiveness of MFA spokespersons in response to confrontational questions, along with a parallel increase in both aggressive questioning and responses.

Our data reveal stark temporal and issue-specific variations in the aggressiveness of journalistic questions and MFA responses. Temporally, aggressiveness on both sides remained consistently high during (the early stage of) COVID-19, but from mid-2021 onwards, it generally trended downwards. That said, the receding of China’s WWD was not characterized by a uniform trend towards ever less aggressiveness; rather it was punctuated by a patchwork of highly aggressive moments. As such, the wolf warriorism in Chinese diplomacy is unlikely to dissipate completely; it will likely re-emerge when China is again subject to intense international criticism. Equally, aggressiveness on both sides varied greatly across issue areas. There was greater aggressiveness exhibited by both foreign journalists and the MFA in issue areas that China increasingly prioritizes (for example, technology) or those that it has long considered as its “core interests” (for example, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Xinjiang, the South China Sea).

Our research makes two contributions – one empirical and one conceptual – to wider debates on Chinese diplomacy. Empirically, we move the discussion about the origins of China’s WWD beyond the focus on such macro-level factors as domestic pressure and international criticism. Our analysis highlights the role of a micro-level factor in sustaining and amplifying wolf warriorism in Chinese diplomacy. More broadly, the interactions between Chinese MFA spokespersons and foreign journalists constitute a microcosm of those between China and the global community. Seen this way, our study offers a telling example of how China’s (diplomatic) practice can be shaped in and through its interactions with the outside world, thereby attesting to the need for studying it from an interactional perspective.

Second, we suggest a novel way for understanding and operationalizing aggressiveness in Chinese diplomatic rhetoric. While there are well-established indicators for evaluating aggressiveness in journalistic questioning, no such indicators exist for studying aggressiveness in diplomatic rhetoric. Attuned to our analysis, we propose to use the presence of ad hominem attack as a proxy. The typology of ad hominem attack, underpinned by three types of fallacious arguments, offers a vantage point for analysing aggressiveness in diplomatic rhetoric.

Contributions aside, our study has limitations. First, the distinct question–answer structure at MFA press conferences allows us to make a compelling case for the causal effect of aggressive questioning based on our findings. However, our (qualitative) research design is such that we are unable to eliminate all the potential causes of endogeneity in our inference. Second, much as we would like to take a longer perspective and compare aggressiveness in foreign journalistic questioning before and after the rise of WWD, we are unable to do so; the data on media organizations attending and asking questions at MFA press conferences before March 2020 are unavailable.

In demonstrating the effect of aggressive journalistic questioning on the shaping of China’s WWD, our study suggests some avenues for future research. For example, future studies could probe how MFA spokespersons’ aggressiveness on social media featured in China’s WWD, or shift the focus to other “wolf warrior” diplomats (for example, Chinese ambassadors in Europe) and analyse how they reacted to critical questions or comments on China. Equally, given the conjunctural nature of causality, it would be interesting to explore how aggressive questioning or intense international criticism interacted with domestic factors (for example, popular nationalism, top-down political pressure) in the rise of wolf warriorism in Chinese diplomacy.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741025000396.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the three anonymous reviewers, as well as Chengxin Pan and Weiwen Yin for their excellent comments. We also commend the editorial team of The China Quarterly for an efficient review process.

Competing interests

None.

Lize YANG is an assistant professor at the School of International Relations, Sun Yat-sen University. His research focuses on Chinese diplomacy and foreign relations. He has published in Global Policy.

Hai YANG is an assistant professor at the department of government and public administration, University of Macau. His research centres on Chinese external communications and the politics of (de)legitimation in global governance. His research has appeared in International Studies Review, International Affairs, Global Policy and Cambridge Review of International Affairs, among others.