1. ATIMAÔ/ATIMOÔ AND ATIMAZÔ IN THE ATTIC ORATORS

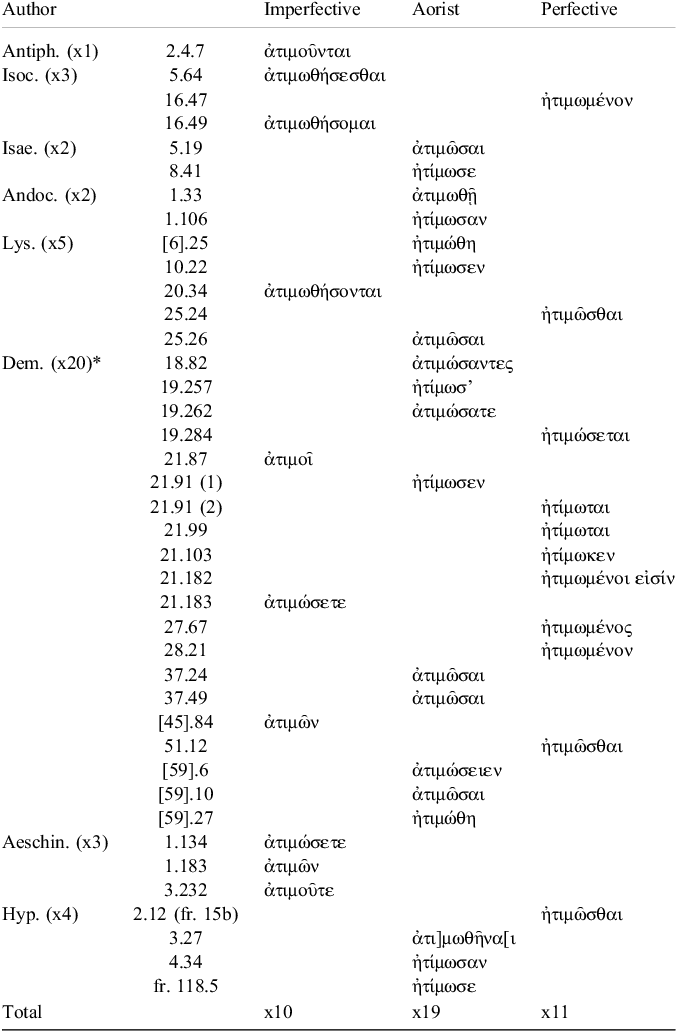

Two families of denominative verbs derive from the noun atimia (normally translated as ‘dishonour’):Footnote 1 atimaô/atimoô and atimazô. As the evidence examined in this article will show, the two families of verbs tend to relate respectively to atimia as a condition and atimia as an action: as a condition (corresponding to atimaô/atimoô), atimia represents the result of a successful act performed in the past; as an action (corresponding to atimazô), atimia describes the attempt to bring dishonour upon another (which might, however, fail). This differentiation is especially evident in the corpus of the Attic orators, where atimaô/atimoô is primarily used in connection to the legal penalty of atimia,Footnote 2 with the sense of ‘making someone legally atimos’ (or, in any case, effecting a tangible loss of status), while atimazô is used to talk about ‘disrespect’ or ‘disregard’.Footnote 3 This use of the verbs is in part reflected also in the ratios of the verbal aspect—imperfective, aorist, perfective—for the two families: as shown in the Appendix below, atimazô is mostly used in its imperfective forms (thirteen of seventeen occurrences), while atimaô/atimoô tends to be used in its aorist (x19) and perfective (x11) forms (out of forty occurrences). As will be seen in Section 2, the same differentiation in the use, and the same ratios of the verbal aspect, can be observed also in other major prose texts of the Classical period (Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon, Plato and Aristotle), where we regularly find atimazô for attempts to ‘dishonour’ others (mostly in imperfective forms), atimaô/atimoô for the legal penalty of atimia and/or objective loss of status (mostly in perfective forms).Footnote 4

The differentiation in the use of these verbs is a relatively late development, which was probably aided by the formalization of atimia as a legal penalty.Footnote 5 In the Homeric epos, for instance, atimaô/atimoô and atimazô are used interchangeably, sometimes in the exact same context, and often to talk about unwarranted disrespect rather than actual loss of ‘honour’.Footnote 6 However, in our prose sources from the Classical period, this is not the case—and this is particularly noticeable in the orators. Demosthenes’ Against Meidias (Dem. 21) provides a compelling exemplification of how the two families of verbs are used in the corpus. For instance, when discussing how Strato of Phalerum had become legally atimos for (allegedly) mishandling his role as arbitrator,Footnote 7 Demosthenes invariably employs the verb atimaô/atimoô:Footnote 8 at §§87–91,Footnote 9 when he recounts the story of Strato’s conviction, and at §99, when he highlights the seriousness of his situation by saying that ‘he had quite simply been made atimos by the strength of Meidias’ anger and hybris’ (ἁπλ![]() ς οὕτως ἠτίμωται [from atimaô/atimoô] τ

ς οὕτως ἠτίμωται [from atimaô/atimoô] τ![]() ῥύμῃ τ

ῥύμῃ τ![]() ς ὀργ

ς ὀργ![]() ς καὶ τ

ς καὶ τ![]() ς ὕβρεως τ

ς ὕβρεως τ![]() ς Μειδίου).Footnote 10 The verb is used to talk about the legal penalty of atimia in two other instances in the speech. First, at §103, where Demosthenes reminds the judges of how ‘dusty’ Euctemon, who had been hired by Meidias to lodge an accusation for cowardice (graphê deilias)Footnote 11 against Demosthenes, ‘made himself atimos’ (ἐκεȋνος ἠτίμωκεν αὑτόν) by failing to ‘follow through’ (epexelthein) with the accusation: the penalty for this was (partial) atimia, that is, the loss of the right to bring any type of public charge in the future.Footnote 12 Second, at §§182–3, in a discussion of the penalties against those who commit offences during a festival, Demosthenes mentions people who have been put to death or made atimoi by the courts,Footnote 13 sometimes through the imposition of heavy fines.Footnote 14 Conversely, when Demosthenes is considering atimia as ‘disrespect’ (rather than the legal penalty), he uses the verb atimazô instead. This comes to the fore in Demosthenes’ description of the infamous incident between Euaeon and Boeotus.Footnote 15 According to Demosthenes, when Boeotus punched Euaeon while drunk and Euaeon responded by killing him, it was not the punch itself that made Euaeon angry, but rather the atimia (qua disrespect)—and Demosthenes remarks that he understands the desire to react when disrespected (ἀτιμαζόμενος, from atimazô).Footnote 16 What he is clearly implying is that, by being punched, Euaeon suffered atimia in that he was disrespected by Boeotus, not in that he was punished with legal atimia, or even in that he lost the respect of his peers because of the punch.Footnote 17

ς Μειδίου).Footnote 10 The verb is used to talk about the legal penalty of atimia in two other instances in the speech. First, at §103, where Demosthenes reminds the judges of how ‘dusty’ Euctemon, who had been hired by Meidias to lodge an accusation for cowardice (graphê deilias)Footnote 11 against Demosthenes, ‘made himself atimos’ (ἐκεȋνος ἠτίμωκεν αὑτόν) by failing to ‘follow through’ (epexelthein) with the accusation: the penalty for this was (partial) atimia, that is, the loss of the right to bring any type of public charge in the future.Footnote 12 Second, at §§182–3, in a discussion of the penalties against those who commit offences during a festival, Demosthenes mentions people who have been put to death or made atimoi by the courts,Footnote 13 sometimes through the imposition of heavy fines.Footnote 14 Conversely, when Demosthenes is considering atimia as ‘disrespect’ (rather than the legal penalty), he uses the verb atimazô instead. This comes to the fore in Demosthenes’ description of the infamous incident between Euaeon and Boeotus.Footnote 15 According to Demosthenes, when Boeotus punched Euaeon while drunk and Euaeon responded by killing him, it was not the punch itself that made Euaeon angry, but rather the atimia (qua disrespect)—and Demosthenes remarks that he understands the desire to react when disrespected (ἀτιμαζόμενος, from atimazô).Footnote 16 What he is clearly implying is that, by being punched, Euaeon suffered atimia in that he was disrespected by Boeotus, not in that he was punished with legal atimia, or even in that he lost the respect of his peers because of the punch.Footnote 17

This distinction in the use of the two verbs is observed throughout the corpus of the orators,Footnote 18 and is broadly reflected in the major English translations of the speeches, where atimaô/atimoô is generally linked to the ‘loss of (civic) rights’ and atimazô with the more general notion of ‘dishonour’ or ‘disrespect’. But recognizing the consistency of this distinction is important, because it allows us to clarify the meaning of the verbs in those passages where the context could be ambiguous. Two examples will illustrate this point. The first is in the pseudo-Demosthenic Against Stephanus I (Ps.-Dem. 45). Here the speaker—Apollodorus, who is perhaps also the author of the speechFootnote 19—is accusing the defendant of having given false testimony in a previous paragraphê trial against his stepfather, Phormio, who had formerly been the enslaved manager of his father Pasion’s bank. Apollodorus attacks not only Stephanus (§§53–70), but also his associates, including Phormio (§§71–82) and his (Apollodorus’) brother, Pasicles, whom Apollodorus accuses of being Phormio’s son and therefore illegitimate (§83–4). And indeed, at §84, Apollodorus claims that, when Pasicles is taking legal action together with Phormio, ‘the slave’ (ὅταν γὰρ τ![]() δούλῳ συνδικ

δούλῳ συνδικ![]() ), and making his own brother atimos in the process (τὸν ἀδελϕὸν ἀτιμ

), and making his own brother atimos in the process (τὸν ἀδελϕὸν ἀτιμ![]() ν), it is easy to suspect as much. In one of the standard English translations of the speech, Scafuro seems to read the verb atimaô/atimoô as a reference to ‘dishonour’ in the non-legal sense, and translates ‘when [Pasicles] acts as an advocate for the slave and dishonors his brother’.Footnote 20 However, as Apollodorus himself admits (§6), he had lost the previous paragraphê rather spectacularly, having to pay a heavy epôbelia of more than three talents,Footnote 21 and Pasicles’ testimony, discussed at Dem. 36.22,Footnote 22 appears to have been instrumental in Phormio’s victory. Failure to pay a debt to the state resulted in legal atimia,Footnote 23 and therefore Apollodorus is implying that his brother is associating with Phormio in an attempt to make him (Apollodorus) atimos as a result of the debt:Footnote 24 it is clearly a reference to the legal penalty. Gernet does indeed interpret the passage from this perspective, and translates ‘Lorsqu’on le voit faire cause commune avec son esclave pour faire condamner son frère à l’atimie’,Footnote 25 with Dem. 27.67 as a comparandum. Highlighting that the use of atimaô/atimoô, here and elsewhere, directly refers to the legal penalty of atimia is important, because it not only further indicates that epôbelia was paid to the treasury rather than to the successful litigant,Footnote 26 but it also sheds further light on the speaker’s overall rhetorical strategy of presenting Pasicles as a morally bankrupt individual whose testimony is not to be trusted, because he is well versed in misusing the courts to his advantage—and not merely disrespectful towards his brother.

ν), it is easy to suspect as much. In one of the standard English translations of the speech, Scafuro seems to read the verb atimaô/atimoô as a reference to ‘dishonour’ in the non-legal sense, and translates ‘when [Pasicles] acts as an advocate for the slave and dishonors his brother’.Footnote 20 However, as Apollodorus himself admits (§6), he had lost the previous paragraphê rather spectacularly, having to pay a heavy epôbelia of more than three talents,Footnote 21 and Pasicles’ testimony, discussed at Dem. 36.22,Footnote 22 appears to have been instrumental in Phormio’s victory. Failure to pay a debt to the state resulted in legal atimia,Footnote 23 and therefore Apollodorus is implying that his brother is associating with Phormio in an attempt to make him (Apollodorus) atimos as a result of the debt:Footnote 24 it is clearly a reference to the legal penalty. Gernet does indeed interpret the passage from this perspective, and translates ‘Lorsqu’on le voit faire cause commune avec son esclave pour faire condamner son frère à l’atimie’,Footnote 25 with Dem. 27.67 as a comparandum. Highlighting that the use of atimaô/atimoô, here and elsewhere, directly refers to the legal penalty of atimia is important, because it not only further indicates that epôbelia was paid to the treasury rather than to the successful litigant,Footnote 26 but it also sheds further light on the speaker’s overall rhetorical strategy of presenting Pasicles as a morally bankrupt individual whose testimony is not to be trusted, because he is well versed in misusing the courts to his advantage—and not merely disrespectful towards his brother.

The second example is in the speech Against Timarchus (Aeschin. 1.183), where the verb atimaô/atimoô is used in the context of a discussion of a (supposedly) Solonian law on ‘the good order of women’ (ἡ τ![]() ν γυναικ

ν γυναικ![]() ν εὐκοσμία). By this law, Aeschines explains, any woman caught with a seducer was no longer allowed to wear jewellery and make-up, nor to attend public religious ceremonies, and anyone who caught her doing any of those things could mistreat her at will, provided that she was not killed or mutilated.Footnote 27 In this way the legislator is making the woman’s life ‘not worth living’ (τὸν βίον ἀβίωτον αὐτ

ν εὐκοσμία). By this law, Aeschines explains, any woman caught with a seducer was no longer allowed to wear jewellery and make-up, nor to attend public religious ceremonies, and anyone who caught her doing any of those things could mistreat her at will, provided that she was not killed or mutilated.Footnote 27 In this way the legislator is making the woman’s life ‘not worth living’ (τὸν βίον ἀβίωτον αὐτ![]() παρασκευάζων) and ‘punishing her with atimia’ (ἀτιμ

παρασκευάζων) and ‘punishing her with atimia’ (ἀτιμ![]() ν). The passage is analysed in Rocchi (n. 2) as part of a larger argument that challenges the communis opinio on atimia—namely, that it was a legal penalty used only against male Athenian citizens—by which the reference to atimia at Aeschin. 1.183 has generally be read as referring to extra-legal, informal dishonour.Footnote 28 The use of a verb that is employed virtually without fail in the corpus of the orators (and invariably in the forensic speeches) to describe the legal penalty of atimia, in a context where the text of an actual law is discussed, seems to me to provide further confirmation to the interpretation of atimia as a legal penalty (loss of one or more rights) that was programmatically flexible and whose actual application (that is, the right(s) being targeted) depended both on the crime committed and on the legal identity (and associated legal rights) of the person it was meted out to, regardless of gender. However, even if we reject this reading, it still seems significant that the verb selected to describe these women’s condition is one that focusses on the reality of their situation and on the tangible results of the legal provision: the actual curtailment of their freedom of movement and of expression, and a loss of standing in the community (with a corresponding loss of the legal right to protection from bodily harm) that is enshrined in the laws of the city.Footnote 29

ν). The passage is analysed in Rocchi (n. 2) as part of a larger argument that challenges the communis opinio on atimia—namely, that it was a legal penalty used only against male Athenian citizens—by which the reference to atimia at Aeschin. 1.183 has generally be read as referring to extra-legal, informal dishonour.Footnote 28 The use of a verb that is employed virtually without fail in the corpus of the orators (and invariably in the forensic speeches) to describe the legal penalty of atimia, in a context where the text of an actual law is discussed, seems to me to provide further confirmation to the interpretation of atimia as a legal penalty (loss of one or more rights) that was programmatically flexible and whose actual application (that is, the right(s) being targeted) depended both on the crime committed and on the legal identity (and associated legal rights) of the person it was meted out to, regardless of gender. However, even if we reject this reading, it still seems significant that the verb selected to describe these women’s condition is one that focusses on the reality of their situation and on the tangible results of the legal provision: the actual curtailment of their freedom of movement and of expression, and a loss of standing in the community (with a corresponding loss of the legal right to protection from bodily harm) that is enshrined in the laws of the city.Footnote 29

This focus on the end result of the action is especially prominent also in Isoc. 5.64, which is the only passage among the forty instances of atimaô/atimoô that is not immediately related to the legal penalty of atimia. Significantly, the instance is found not in a forensic speech, but rather in a pamphlet where Isocrates is addressing Philip II of Macedon and inviting him to unite all the Greek city-states and lead an expedition against the Persians. He uses the example of Conon who, after the battle of Aegospotami, had a fall from grace, but then recovered at the battle of Cnidus and managed to revive the fortunes of Athens as well. ‘And yet’, Isocrates asks, ‘who would have thought that the affairs of Greece would be overturned by a man who was doing so poorly, and that some of the Greek cities would suffer atimia (ἀτιμωθήσεσθαι) while others would raise to prominence?’ Isocrates is clearly not referring to the legal penalty of atimia here—what he wants to stress, by using atimaô/atimoô, is the fact that this reversal of fortune did in fact happen to these cities. It is not that, subjectively, these city-states felt disrespected—they actually suffered a loss of status, and forfeited the position of power they previously enjoyed.Footnote 30 What is in focus here, then, is the perfective meaning of the verb, which is the basis for its use as the preferred verb to describe the legal penalty of atimia: it describes an action performed in the past that has an objective result in the present.

On the other hand, the instances of atimazô—seventeen in total—undoubtedly show that the verb is used primarily to convey the idea of ‘(unwarranted) disrespect’. Aside from the clear example of Euaeon and Boeotus (pages 3–4 above), two instances in Aeschines’ speech On the Embassy (Aeschin. 2) clarify this point. In the opening paragraphs, Aeschines claims that, by slandering him, Demosthenes ‘dishonours’ (ἀτιμάζει, §9) him—he disrespects him, not giving him his due.Footnote 31 A similar use of the verb is found at §121, where Aeschines suggests that an envoy who had been prevented by his colleagues from reporting to the Assembly might rightly consider himself disrespected (ἀτιμασθείς), clearly implying that such behaviour on the part of his fellow ambassadors would be unwarranted, and would certainly not entail legal consequences for the disrespected envoy.Footnote 32 The same form of the verb is used by Demosthenes, coupled with the passive participle of propêlakizô, ‘to pelt with mud’ (ἀτιμασθεὶς καὶ προπηλακισθείς),Footnote 33 at Dem. 22.62, when the speaker, Diodorus, is describing how those who had been unjustly slandered and insulted by the defendant, Androtion, had understandably come to hate him.Footnote 34

The verb atimazô appears also in the second speech Against Boeotus (Ps.-Dem. 40), concerned with the recovery of Mantitheus’ mother’s dowry. This instance is worth examining, because the dispute raises issues of citizenship and legitimacy—and so, potentially, of atimia and epitimia as legal notions.Footnote 35 Mantitheus does often cast doubt on whether his father, Mantias, was also the father of Boeotus and Boeotus’ brother Pamphilus,Footnote 36 and uncertainty as to their father’s identity would have endangered their citizen status,Footnote 37 because being born of two Athenian parents was the condicio sine qua non to be considered citizens by birth.Footnote 38 However, he sensibly does not make much of this claim: first, because he himself is forced to admit that Mantias seemed to have been in love with Boeotus’ mother Plangon, and that they had children;Footnote 39 and second, because it is easier (and more advantageous to Mantitheus’ argument) to maintain that Mantias and Plangon, although they had a romantic relationship, were never actually married, since this would disprove the existence of Plangon’s dowry and endanger Boeotus’ and Pamphilus’ claim to a portion of Mantias’ estate—children of Athenian parents born out of wedlock were still citizens,Footnote 40 but could not inherit. Thus, when Mantitheus repeatedly uses the verb atimazô at §§26–9, he is not thinking of legal atimia,Footnote 41 especially since he starts by assuming his opponent’s point of view and suggesting that Boeotus would say that Mantias had disrespected (ἠτίμαζεν, §26) him, his brother, and their mother for the sake of Mantitheus and his mother: from Boeotus’ perspective (as described by Mantitheus), being excluded from Mantias’ household despite being his son had been a misrecognition of a legitimate claim. Indeed, in the following paragraphs, Mantitheus not only maintains that it would have been far more likely for Mantias to ‘dishonour’ (ἀτιμάζειν, §27)—that is, exclude from his household—him rather than Plangon’s children, but also that Boeotus cannot even claim that Mantias had adopted him as a child and then (unfairly) ‘dishonoured’ (ἠτίμαζεν, §29) him at a later time due to his anger at Plangon.Footnote 42 Here the action of dishonouring (atimazein) is explicitly contrasted to adoption and admission into Mantias’ family, and, although adoption is a legal procedure with legal consequences, exclusion from one particular household does not in itself amount to legal atimia. As is explained at §10, Mantias had even arranged for Boeotus and Pamphilus to be adopted by Plangon’s brothers, which would have preserved their political rights (τούτων γὰρ γενομένων οὔτε τούτους ἀποστερήσεσθαι τ![]() ς πολιτείας) while still preventing them from joining his family. This, in Boeotus’ view as Mantitheus presents it, was a clear lack of respect (atimia), irrespective of whether he and his brother kept their citizen status or not.

ς πολιτείας) while still preventing them from joining his family. This, in Boeotus’ view as Mantitheus presents it, was a clear lack of respect (atimia), irrespective of whether he and his brother kept their citizen status or not.

Even though atimazô is never the preferred verb to describe the legal penalty of atimia, in some instances its use has the potential to evoke the penalty without explicitly mentioning it in contexts where it would have been either inappropriate or inexpedient to do so.Footnote 43 That the two families of verbs maintained this kind of connection is not surprising, because the notion of atimia never lost its connection to the socio-ethical sphere, despite being an actual legal remedy. And yet, the consistency with which atimaô/atimoô is used to describe the legal penalty, while atimazô is employed in connection with atimia as ‘lack of respect’, is too pronounced to be casual, and the rare appearances of atimazô in passages where legal atimia is suggested invariably show that the verb was selected to highlight the focus on the extra-legal aspects of the concept. This can be seen in stark relief in the speech Against Philon (Lys. 31), a dokimasia speech against a prospective member of the Council.Footnote 44 After explaining at length why Philon is not worthy of Council membership, often by suggesting that he had engaged in actions—such as maltreatment of parents or military misconductFootnote 45—that were punishable with atimia,Footnote 46 the speaker says explicitly that the members of the outgoing Council, who are presiding over the dokimasia, should punish Philon at least ‘with the atimia available at this moment’ (τ![]() γε παρούσῃ ἀτιμίᾳ, §29), that is, rejection from office—since, as explained by Canevaro and Rocchi, the notion of timê in the legal sphere can identify a legal right,Footnote 47 revocation of a right can be construed as atimia.Footnote 48 Lysias, however, is well aware of the fact that this atimia, despite preventing its target from exercising a legal right, is contiguous but not entirely assimilable to the legal penalty bestowed upon conviction, that is, the atimia that he evoked when speaking of neglecting one’s parents or deserting one’s post. Therefore, at §30, he moves to a more general remark about how the Council honours good men (τοὺς ἀγαθοὺς ἄνδρας … τιμᾶτε) and dishonours bad ones (τοὺς κακοὺς ἀτιμάζετε)—he uses the verb atimazô not only to broaden the scope of his argument (which nods to the penalty of atimia but is not limited to it),Footnote 49 but also because, strictly speaking, rejecting a prospective councillor at his dokimasia is not equivalent to a conviction for the relevant crimes, even though it might lead to it.Footnote 50 Accordingly, at §33, Lysias’ client explains to the councillors that they would not disrespect Philon (οὐ γὰρ ὑμεȋς ν

γε παρούσῃ ἀτιμίᾳ, §29), that is, rejection from office—since, as explained by Canevaro and Rocchi, the notion of timê in the legal sphere can identify a legal right,Footnote 47 revocation of a right can be construed as atimia.Footnote 48 Lysias, however, is well aware of the fact that this atimia, despite preventing its target from exercising a legal right, is contiguous but not entirely assimilable to the legal penalty bestowed upon conviction, that is, the atimia that he evoked when speaking of neglecting one’s parents or deserting one’s post. Therefore, at §30, he moves to a more general remark about how the Council honours good men (τοὺς ἀγαθοὺς ἄνδρας … τιμᾶτε) and dishonours bad ones (τοὺς κακοὺς ἀτιμάζετε)—he uses the verb atimazô not only to broaden the scope of his argument (which nods to the penalty of atimia but is not limited to it),Footnote 49 but also because, strictly speaking, rejecting a prospective councillor at his dokimasia is not equivalent to a conviction for the relevant crimes, even though it might lead to it.Footnote 50 Accordingly, at §33, Lysias’ client explains to the councillors that they would not disrespect Philon (οὐ γὰρ ὑμεȋς ν![]() ν αὐτὸν ἀτιμάζετε) by not letting him hold office, but it is rather he himself who has behaved in a manner that has made him unworthy of active participation (ἀλλ᾽ αὐτὸς αὑτὸν τότε ἀπεστέρησεν): in this instance, with one verb, Lysias not only shows his awareness of the relationship (and difference) between rejection at a dokimasia and atimia upon conviction, but also suggests that, by excluding Philon, his client’s fellow councillors are not ‘unjustly disrespecting’ him—Philon would indeed have no right to be angry (μόνος δή … δικαίως οὐδ᾽ ἂν ἀγανακτοίη μὴ τυχών),Footnote 51 because he fully deserves to be excluded from office.Footnote 52 The expression, then, exonerates the outgoing councillors from the accusation of having unjustly disrespected Philon while simultaneously suggesting that Philon himself has indeed made himself atimos, and his atimia could (and should) very well be actualized.Footnote 53

ν αὐτὸν ἀτιμάζετε) by not letting him hold office, but it is rather he himself who has behaved in a manner that has made him unworthy of active participation (ἀλλ᾽ αὐτὸς αὑτὸν τότε ἀπεστέρησεν): in this instance, with one verb, Lysias not only shows his awareness of the relationship (and difference) between rejection at a dokimasia and atimia upon conviction, but also suggests that, by excluding Philon, his client’s fellow councillors are not ‘unjustly disrespecting’ him—Philon would indeed have no right to be angry (μόνος δή … δικαίως οὐδ᾽ ἂν ἀγανακτοίη μὴ τυχών),Footnote 51 because he fully deserves to be excluded from office.Footnote 52 The expression, then, exonerates the outgoing councillors from the accusation of having unjustly disrespected Philon while simultaneously suggesting that Philon himself has indeed made himself atimos, and his atimia could (and should) very well be actualized.Footnote 53

A rhetorical use of the verb that fully capitalizes on its connection with the legal penalty is in Isocrates’ Encomium of Helen (10.58),Footnote 54 probably a response to Gorgias’ work of the same title. At the end of a section centred around the importance of beauty (§§54–8), Isocrates remarks that our reverence and concern for beauty are so great that ‘of those who possess beauty, we dishonour (ἀτιμάζομεν) those who hire themselves out (τοὺς … μισθαρνήσαντας) and make bad decisions with regard to their youthful charms more than those who wrong the bodies of others’. The reference to the legal penalty of atimia is clear: as we know from the Against Timarchus,Footnote 55 male citizens who ‘hired themselves out’ were regarded as atimoi and required to behave as such.Footnote 56 Yet Isocrates does not use atimaô/atimoô precisely because the verb here governs two categories, one of which—actual male prostitutes—might be subject to atimia in either sense (legal, as the penalty, and extra-legal, as ‘disgrace’ or ‘disrepute’), while the other—those who mishandle their beauty—would more normally be subject to it only in the non-legal sense. Moreover, Isocrates wishes his statement to have general validity from a socio-ethical standpoint: he is not interested in examining the legal consequences of (male) prostitution—which are not immediately relevant in this context—but rather, in using this analogy grounded by the allusion to legal atimia, to demonstrate the extent to which the misuse of beauty is generally regarded as morally base. In addition Isocrates, throughout the speech, often borrows forensic terms—such as ‘judge’,Footnote 57 ‘witness’Footnote 58 or ‘proof’Footnote 59—but intentionally gives them a different spin by using them in entirely non-legal contexts: he toys with legal notions and terminology without committing to a forensic style or to full-blown legal argumentation both to show awareness of the apologetic style of the previous Encomium of Helen—his polemical target—and to highlight, by contrast, his superior command of the encomiastic genre.Footnote 60 Thus in alluding to atimia, Isocrates might have had at the back of his mind a specific passage of the Gorgian speech, where the legal penalty is directly mentioned in a discussion on how ‘the undertaking undertaken by the barbarian [sc. abducting Helen and using hybris against her]Footnote 61 was barbarous in word and law and deed, and deserves blame in word, atimia in law (νόμῳ δὲ ἀτιμίας) and punishment in deed’:Footnote 62 Isocrates would then be showcasing not only his greater ability in using legal elements appropriately within a non-forensic speech, but also his deeper knowledge of Athenian lawFootnote 63—while, in classical Athens, (male) prostitution did invariably result in atimia qua debarment from active participation in political life, the penalty upon conviction for hybris was not fixed by law.Footnote 64

One final striking example is Lys. 16.5. Among the passages in which atimazô is used, this is the one for which the connection with the legal penalty of atimia would seem, at first sight, indisputable: when the speaker, Mantitheus,Footnote 65 says that the Thirty ‘would rather dishonour (ἠτίμαζον) those who joined them in overthrowing the dêmos’ than giving people who were abroad—like himself—a share in the constitution (μεταδιδόναι τ![]() ς πολιτείας), it might be hard to believe that he did not think, perhaps almost exclusively, of the diminution of rights of those who were debarred from active participation by the Thirty, which can be framed as a type of legal atimia. But the use of atimazô instead of atimaô/atimoô does not seem casual: imposing the penalty of atimia on an individual (atimaô/atimoô) is always the result of a legal process which, even though mistakes can be made,Footnote 66 is fundamentally sound and depends on criteria that have been agreed upon by the community. On the contrary, the Thirty’s regime had been the epitome of illegality and unlawfulness: they killed and exiled, removed citizens from government,Footnote 67 and disregarded the legitimate claims of both citizens and metics, and nothing they did—Mantitheus seems to suggest—can be described with the language of the law. While the unlawful exclusion enacted by the Thirty can be (and at times is) described as atimia,Footnote 68 with the verb atimazô Mantitheus is able to embrace—and denounce—a wider range of disrespectful treatments, and all the examples of ungratefulness (even towards those who helped them) perpetrated by the Thirty. He also manages to imply, in one stroke, that the Thirty were operating completely outside the boundaries imposed by the law.

ς πολιτείας), it might be hard to believe that he did not think, perhaps almost exclusively, of the diminution of rights of those who were debarred from active participation by the Thirty, which can be framed as a type of legal atimia. But the use of atimazô instead of atimaô/atimoô does not seem casual: imposing the penalty of atimia on an individual (atimaô/atimoô) is always the result of a legal process which, even though mistakes can be made,Footnote 66 is fundamentally sound and depends on criteria that have been agreed upon by the community. On the contrary, the Thirty’s regime had been the epitome of illegality and unlawfulness: they killed and exiled, removed citizens from government,Footnote 67 and disregarded the legitimate claims of both citizens and metics, and nothing they did—Mantitheus seems to suggest—can be described with the language of the law. While the unlawful exclusion enacted by the Thirty can be (and at times is) described as atimia,Footnote 68 with the verb atimazô Mantitheus is able to embrace—and denounce—a wider range of disrespectful treatments, and all the examples of ungratefulness (even towards those who helped them) perpetrated by the Thirty. He also manages to imply, in one stroke, that the Thirty were operating completely outside the boundaries imposed by the law.

Thus in the Attic orators the distinction between atimaô/atimoô and atimazô is consistently observed: atimaô/atimoô expresses the notion of ‘objective loss of status’, which is most normally represented by the legal penalty of atimia, while atimazô describes a kind of ‘disrespect’ that is primarily extra-legal, even though it can assume legal undertones.

2. ATIMAÔ/ATIMOÔ AND ATIMAZÔ IN OTHER CLASSICAL PROSE TEXTS

As mentioned in Section 1, this distinction in the use of the two families of verbs is found not only in the orators, but also in other major classical prose texts.Footnote 69 A few examples from classical historiography and philosophy will make this clear.

In Herodotus (not an Athenian), atimaô/atimoô is used on two occasions, and in both cases it refers to non-Athenian contexts. At 4.66, while discussing Scythian customs around war (4.64–6), Herodotus describes an annual celebration where the Scythians partake in wine-drinking on the basis of their military prowess: those of them who have killed enemies drink one cup of wine; those who have killed an extraordinary amount, two; those who have killed none, however, are not allowed to drink, but rather have to sit apart, ‘dishonoured’ (ἠτιμωμένοι, from atimaô/atimoô). Here the use of the verb is similar to what we find at Isoc. 5.64: the reference is not to the (Athenian) legal penalty of atimia, but rather to the fact that these ‘unworthy’ Scythians, in the eyes of their community, have failed to live up to the standards of behaviour that are collectively endorsed, and suffered a corresponding diminution of status. The rationale is similar to that behind atimia as the legal penalty for military misconduct in Athens (cf. n. 46). A connection between shortcomings in the military sphere and atimia as an objective loss of status is clear also in the second Herodotean passage where atimaô/atimoô is used, dealing with Sparta. At 7.231, Herodotus recounts the fate of Aristodemus who, upon surviving the battle of Thermopylae, was dishonoured (ἠτίμωτο) in that his fellow Spartans refused to speak or share their fire with him, and mockingly called him ‘the Trembler’. Herodotus also tells us that another Spartan Thermopylae survivor, named Pantites, was dishonoured in the same way (ἠτίμωτο, §232). Several other—mostly Athenian—authors link the Spartan treatment of cowards with the notion of atimia,Footnote 70 which seems to have been a legally sanctioned penalty (if, perhaps, under a different name) also in Sparta.Footnote 71 By contrast, unjustified dishonour is described with atimazô at 1.61, where Pisistratus having sexual relations with his wife, Megacles’ daughter, ‘not by the book’ (οὐ κατὰ νόμον) in order to avoid having children with her is perceived as a terrible lack of respect by Megacles (and presumably also by his daughter).

Thucydides never uses atimaô/atimoô, but has atimazô in two instances. The first is in Diodotus’ speech in the context of the Mytilenean debate (3.42.5): Diodotus is saying that a sensible polis should neither grant additional honour to her good advisers nor detract anything from the honour they already possess, and that a speaker whose advice does not prevail should suffer neither punishment nor dishonour (καὶ τὸν μὴ τυχόντα γνώμης οὐχ ὅπως ζημιο![]() ν ἀλλὰ μηδ᾽ ἀτιμάζειν). Here atimazô is contrasted with zêmioô, ‘to punish’: if Thucydides were referring to the legal penalty of atimia, the contrast would make no sense. At 6.38.5, in Athenagoras’ speech during an Assembly debate in Syracuse, the speaker directly addresses the youth and says that their exclusion from office is simply due to their age: once they will have reached maturity, no legal barriers will stand in their way. The verb conveys that this exclusion is due to no fault of their own, and therefore carries no shame—it is merely a question of reaching the appropriate age, and Athenagoras wants to stress that they will not be unjustly dishonoured (atimazô) once they are old enough to serve.

ν ἀλλὰ μηδ᾽ ἀτιμάζειν). Here atimazô is contrasted with zêmioô, ‘to punish’: if Thucydides were referring to the legal penalty of atimia, the contrast would make no sense. At 6.38.5, in Athenagoras’ speech during an Assembly debate in Syracuse, the speaker directly addresses the youth and says that their exclusion from office is simply due to their age: once they will have reached maturity, no legal barriers will stand in their way. The verb conveys that this exclusion is due to no fault of their own, and therefore carries no shame—it is merely a question of reaching the appropriate age, and Athenagoras wants to stress that they will not be unjustly dishonoured (atimazô) once they are old enough to serve.

All instances of atimaô/atimoô in the Xenophontean corpus are found in the Constitution of the Athenians by the so-called Old Oligarch, where the reference is clearly to the Athenian legal penalty of atimia.Footnote 72 By contrast, the instances of atimazô in the corpus are never connected to the penalty. In some cases, the verb conveys the idea of ‘unwarranted disrespect’: for example, at Hell. 4.1.27, where Herippidas confiscates the booty amassed by Spithridates and the Paphlagonians, who then feel unjustly disrespected by him; or at Ages. 5.5, where Megabates perceives Agesilaus’ refusal to kiss him as an unwarranted lack of respect. In other cases, atimazô describes a kind of disrespect that is perceived as justified at a socio-ethical level, but is not legally sanctioned. This is clear at Cyn. 12.21, where Virtue is said to honour those who are good to her and dishonour those who are bad (τιμ![]() τοὺς περὶ αὐτὴν ἀγαθούς, τοὺς δὲ κακοὺς ἀτιμάζει), but also at Mem. 2.2.14, where Socrates warns his son Lamprocles that being ungrateful (acharistos) to one’s mother is bound to attract the disesteem of other people. This second example is particularly telling because, in Athenian law, maltreating one’s parents was punished with atimia;Footnote 73 and yet, here Socrates/Xenophon chooses the verb atimazô both because he wants to focus on the social—rather than the legal—dimension of the ‘offence’ (that is, being shunned by one’s fellow men), and because, on a more practical level, being ungrateful towards one’s parents does not invariably entail the kinds of neglect and abuse that would be actionable under the Athenian graphê kakôseôs goneôn (and would be much harder to prove in court).

τοὺς περὶ αὐτὴν ἀγαθούς, τοὺς δὲ κακοὺς ἀτιμάζει), but also at Mem. 2.2.14, where Socrates warns his son Lamprocles that being ungrateful (acharistos) to one’s mother is bound to attract the disesteem of other people. This second example is particularly telling because, in Athenian law, maltreating one’s parents was punished with atimia;Footnote 73 and yet, here Socrates/Xenophon chooses the verb atimazô both because he wants to focus on the social—rather than the legal—dimension of the ‘offence’ (that is, being shunned by one’s fellow men), and because, on a more practical level, being ungrateful towards one’s parents does not invariably entail the kinds of neglect and abuse that would be actionable under the Athenian graphê kakôseôs goneôn (and would be much harder to prove in court).

Similarly, in the Aristotelian corpus, atimaô/atimoô is used only twice, with reference to the legal penalty. Significantly, both instances are found in the works on constitutions:Footnote 74 at [Ath. Pol.] 53.6, where the verb describes the penalty used for misbehaving public arbitrators in Athens; and at fr. 611.42 Rose, from the constitution of Lepreum (Triphylia, Elis),Footnote 75 to talk about the penalty against both men and women caught in moicheia. atimazô is, again, only used to refer to ‘disrespect’: the best examples are at Pol. 1302b11–14 and Rh. 1378b30, where it designates disrespect that is perceived as unjust by its target.Footnote 76

Finally, the case of Plato is the most instructive. The only two instances of atimaô/atimoô in the corpus are Ap. 30d2 and Resp. 553b5, and both passages discuss legal penalties—death, exile or atimia—that can be incurred upon conviction in court. The instances of atimazô are much more numerous,Footnote 77 and they all refer to atimia as ‘disrespect’ or ‘disregard’: for instance, the passages cited above can be contrasted with Ap. 19c5 and 34e1, and Resp. 549d5, 551a4–5, where this sense is especially clear. The careful avoidance of the verb atimaô/atimoô is particularly significant in the Laws.Footnote 78 As Plato clarifies at Leg. 855c1–2, in Magnesia ‘nobody shall be made completely atimos (ἄτιμον … παντάπασιν) for any single crime’; accordingly, when the penalty of atimia is meted out, the expression used is the legal formula ἄτιμος ἔστω (‘let him/her be atimos’),Footnote 79 followed by the precise indication of the area(s) in which the criminal will experience a diminution of rights:Footnote 80 this is done to avoid the confusion that might derive from the use of atimaô/atimoô, which, in the orators, is most often used in reference to total atimia. The one instance in which atimazô is used with the sense of ‘excluding from office’ (Pl. Leg. 762d1–6) is consistent with the use of the verb at Lys. 31.29–30 (examined at pages 8–10 above): Plato’s wording suggests that being excluded from certain offices, from a legal point of view, is not the same thing as atimia upon conviction—and especially in the case of the officials whose functions he is describing in the passage (the archons and the agronomoi), who only serve for a period of two years and can therefore be debarred only during that limited timeframe. The meaning of atimazô, in opposition to the legal formula ἄτιμος ἔστω, is particularly evident at Pl. Leg. 784d2–e7, where it is prescribed that both men and women of reproductive age who engage in extramarital sex shall be atimoi (ἄτιμος ἔστω) and lose certain prerogatives—attending marriages and children’s birthday parties, as well as, for women, female excursions (τ![]() ν ἐξόδων … τ

ν ἐξόδων … τ![]() ν γυναικείων) and other feminine rights (τιμ

ν γυναικείων) and other feminine rights (τιμ![]() ν)—whereas older men and women are simply to be held in disesteem (ἀτιμαζέσθω, from atimazô).

ν)—whereas older men and women are simply to be held in disesteem (ἀτιμαζέσθω, from atimazô).

3. CONCLUSIONS

In the Attic orators, the verbs atimaô/atimoô and atimazô are not used interchangeably: although both families of verbs stem from the same root, atimaô/atimoô is used to describe objective diminutions of status, and most normally the legal penalty of atimia (the objective diminution of status par excellence); by contrast, atimazô expresses informal ‘dishonour’, often of a kind that is felt to be—or might be construed as—unjustified by its target and/or the wider audience. This is shown also by the distribution of verbal aspect in the corpus, where atimazô is found mostly in imperfective forms, to describe a conative action, while atimaô/atimoô is used primarily in aorist and perfective forms, to describe an action that brought about a state of affairs.

This distinction is mirrored in other prose texts from the Classical period: atimaô/atimoô, mostly in aorist and perfective forms, for actual diminution of status and standing (often with reference to the legal penalty of atimia); atimazô, mostly in imperfective forms, to describe instances of disrespect.

APPENDIX: USE OF ATIMAÔ/ATIMOÔ VS ATIMAZÔ IN THE ATTIC ORATORSFootnote 81

1. atimaô/atimoô (x40)

I have disregarded the instance at Dem. 21.93, because the testimony reported there is a late forgery: cf. D.M. MacDowell, Demosthenes. Against Meidias 21 (Oxford, 1990), 316–17 and Harris (n. 10), 120 n. 150.

2. atimazô (x17)

I have disregarded the instance at Ps.-Andoc. 4.31, because the speech is probably a late rhetorical exercise: see MacDowell in M. Gagarin and D.M. MacDowell, Antiphon and Andocides (Austin, 1998), 159–61 and, recently, E.M. Harris, ‘Major events in the recent past in assembly speeches and the authenticity of [Andocides] On the Peace’, Tekmeria 16 (2021), 19–68 and ‘Recent events in assembly speeches and [Andocides] On the Peace’, in A. Kapellos (ed.), The Orators and Their Treatment of the Recent Past (Berlin, 2022), 81–100. The use of the verb is comparable with the rest of the corpus (that is, the verb does not refer to the legal penalty), but perhaps it is significant that it is the only instance in which the aspect of the verb is perfective (ἠτιμακώς), and might be further proof of the spuriousness of the speech.