Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the global suicide mortality rate is over 700,000 per year,1 with estimated reported SA of approximately 1.6 million per year.2 In the United States (U.S.), suicide is among the top 3 leading causes of death in individuals aged 15–343 and among the top 9 leading causes of death in individuals 35–64.3 The economic burden of suicide and depression in the U.S. is $326.2 billion,Reference Greenberg, Fournier, Sisitsky, Simes, Berman and Koenigsberg4 and suicide prevention is a key public health priority across multiple countries.1

Rapid-acting anti-suicidal agents are critical for patients diagnosed with severe major depressive disorder (MDD) and experiencing SI. For example, esketamine was approved in August 2020 for adults with MDD at risk for suicide.Reference Xiong, Lipsitz, Chen-Li, Rosenblat, Rodrigues and Carvalho5 Replicated evidence indicates that insomnia is associated with suicide-related outcomes.Reference Liu, Steele, Hamilton, Do, Furbish and Burke6 Consequently, it could be hypothesized that interventions that alleviate insomnia may have beneficial effects on measures of suicide. The FDA has approved many mechanistically dissimilar sedative-hypnotics in the treatment of insomnia including select antidepressants (e.g., doxepin), benzodiazepines (e.g., temazepam), “Z-drugs” (e.g., zolpidem, zaleplon, zopiclone), and dual orexin receptor antagonists (DORA; e.g., lemborexant, daridorexant, suvorexant).7 Evidence also suggests that CBT-I is effective in reducing depressive symptoms in persons with insomnia.Reference Hertenstein, Trinca and Wunderlin8, Reference Gebara, Siripong, DiNapoli, Maree, Germain and Reynolds9, Reference De Crescenzo, D’Alò, Ostinelli, Ciabattini, Di Franco and Watanabe10

Moreover, extant literature does suggest that select sedative-hypnotics and/or CBT-I may be effective in treating SI, SA, and SC, with potential mechanisms including an improvement in problem solvingReference McCall, Benca, Rosenquist, Youssef, McCloud and Newman11 and nocturnal wakefulness.Reference Kalmbach, Cheng, Ahmedani, Peterson, Reffi and Sagong12 For example, coprescription of zolpidem during initiation of an antidepressant was beneficial in suicidal outpatients, especially in patients with severe insomnia.Reference McCall, Benca, Rosenquist, Youssef, McCloud and Newman11 Pharmacovigilance data suggests that suvorexant, lemborexant, and daridorexant are significantly associated with lower odds of completed suicides compared to trazodone.Reference McIntyre, Wong, Kwan, Rhee, Teopiz and Ho13 Likewise, CBT-I has been reported to reduce measures of SI.Reference Kalmbach, Cheng, Ahmedani, Peterson, Reffi and Sagong12, Reference Jernelöv, Forsell, Kaldo and Blom14, Reference Chan, Lam, Zhang, Chan, Yu and Suh15

Herein, this systematic review aims to identify and evaluate the anti-suicidal effects of benzodiazepines, Z-drugs, ORAs, and other FDA-approved sleep agents. In addition, the effect of CBT-I on measures of suicide is also evaluated.

Methods

Data sources and search strategy

The 2020 PRISMA guidelines were applied in this study.Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann and Mulrow16 A systematic search was performed using the following electronic databases: PubMed, Medline, Cochrane Library, PsycInfo, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science from inception through the end of July 2024. Additional studies were identified manually using Google Scholar. Search strings can be found in the supplementary material. A registered protocol does not exist for this review.

Study selection

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they (1) were RCTs or (2) reported on if CBT-I or one of the following pharmacological sleep interventions were associated with suicide-related measures as either a primary outcome, secondary outcome, or as a safety measure: benzodiazepine, alprazolam, brotizolam, midazolam, triazolam, estazolam, loprazolam, lorazepam, lormetazepam, temazepam, flunitrazepam, flurazepam, nitrazepam, quazepam, zaleplon, zolpidem, zopiclone, eszopiclone, daridorexant, suvorexant, lemborexant, doxepin, quetiapine, secobarbital, benadryl, diphenhydramine, unisom, or doxylamine. Included drugs were either FDA-approved sedative-hypnotics or an agent used off-label for the treatment of insomnia. Studies were excluded if they (1) were not written in English; (2) were not peer reviewed; (3) did not have full-text availability.

Study screening and selection were conducted by two reviewers (KV). Titles and abstracts were initially screened for relevance, and full-text articles were subsequently assessed for eligibility. A second author (KT) cross-validated the screening and inclusion of retrieved studies.

Data extraction

Published summary data from selected articles were independently extracted by KV and KT using a piloted data extraction form. Discrepancies were resolved via discussion with all additional authors. Information to be extracted was identified a priori and included (1) publication year, (2) sample size, (3) sample characteristics, (4) assessment tools, and (5) outcomes related to suicide. We endeavored to define and operationalize suicidality as SI, SA, and SC, reporting the aspect(s) observed in each identified study; however, in instances where study authors failed to separate these three dimensions, the term “suicidality” was applied.

Quality assessment

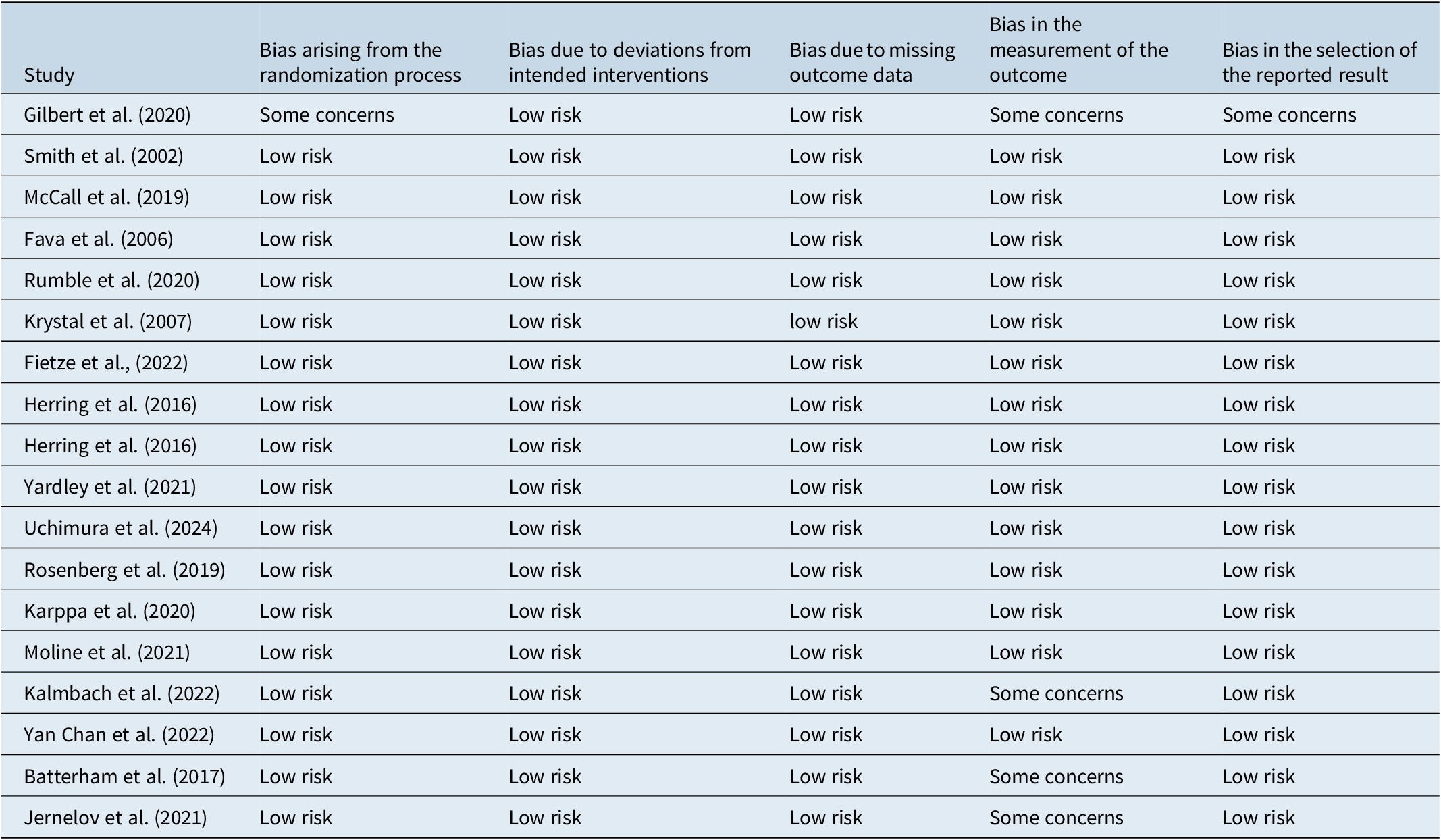

The risk of bias was assessed for all included studies (Table 1). Consistent with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions,Reference Higgins, Higgins and Thomas17 bias was evaluated based on the following areas: bias arising from the randomization process, bias due to deviations from intended interventions, bias due to missing outcome data, bias in the measurement of the outcome, bias in the selection of the reported result. Protocols were denoted as either “low risk,” “some concerns,” or “high risk.”

Table 1. Summary of Study Quality and Bias Assessment in Randomized Trials

Results

Search results

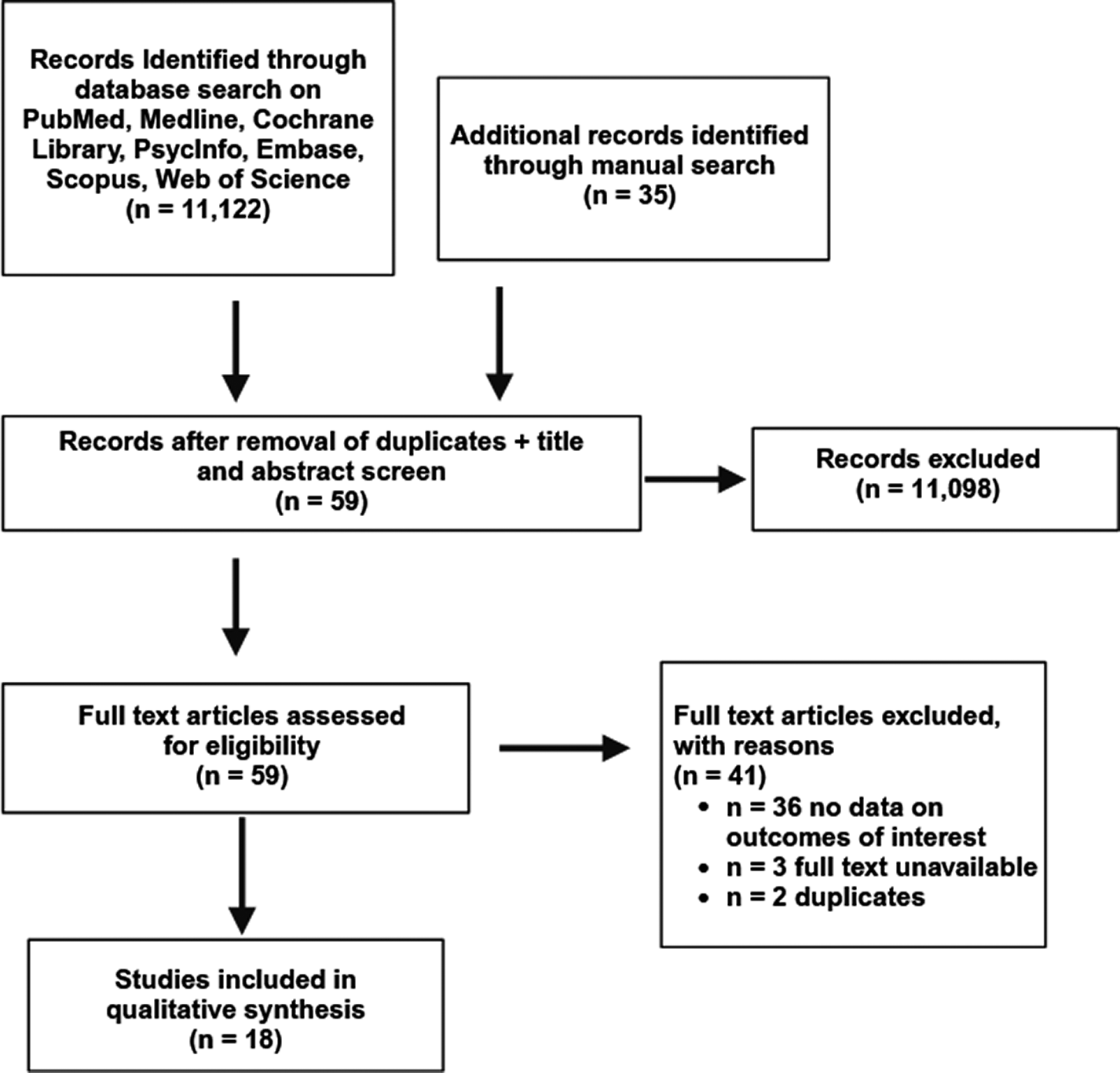

The literature search yielded 11,122 studies. Following the removal of duplicates and screening of titles and abstracts, 59 articles were eligible for full-text screening against eligibility criteria. Following full-text screening, 36 studies were further excluded due to the absence of data related to the outcome(s) of interest. Study selection details are outlined in Figure 1. In total, 18 studies were included.

Figure 1. Study selection flow diagram.

Study characteristics

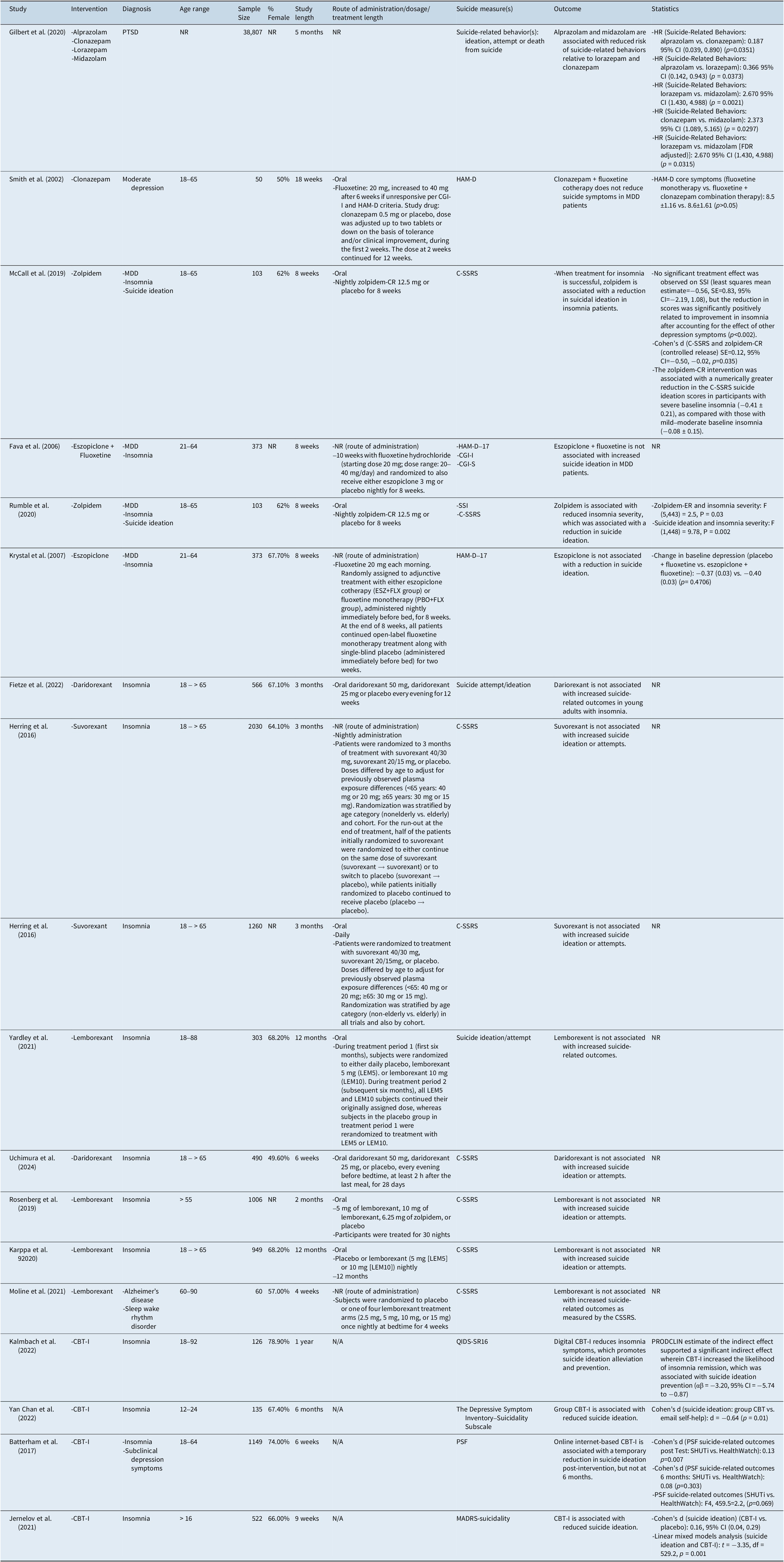

Sociodemographics, outcome measures, and results can be found in Table 2. Sample sizes ranged from 50 to 38,807 for the studies included. The ages of the participants ranged from 12 to 92. Patient diagnoses varied per study and included insomnia disorder, sleep–wake rhythm disorder (one study assessed this disorder comorbid with Alzheimer’s disease), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and MDD. According to reported numbers, females comprised 66.3% of the total population.

Table 2. Study Demographics and Outcomes

Abbreviations: BSSI, Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideations, CBT-I, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia, CGI-I, Clinical Global Impression Improvement, CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression Improvement Severity Items, CI, confidence interval; C-SSRS, Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale, df, degrees of freedom, FDR, false discovery rate, HAM-D, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, HR, hazard ratio, LEM, Lemborexant, MADRS, Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, NR, not reported, PRODCLIN, PRODuct Confidence Limits for INdirect effects, PTSD, post traumatic stress disorder, PSF, psychiatric symptom frequency, QIDS-SR16, Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, SSI, Scale for Suicide Ideation, SHUTi, Sleep Healthy Using the Internet, zolpidem-CR, zolpidem controlled-release, zolpidem-ER, zolpidem extended-release.

Benzodiazepines

Two RCTs studied the anti-suicidal effects of benzodiazepine medications.

Findings suggest that alprazolam and midazolam are associated with reduced risk of suicide-related behaviors (SRBs), defined as SI, SA, or SC. In PTSD patients, alprazolam was associated with fewer SRBs compared to clonazepam (Hazard Ratio (HR) 0.187 (95% CI [0.039, 0.890] p = 0.0351) and lorazepam (HR 0.366 (95% CI [0.142, 0.943] p=0.0373) over an average 6 month follow-up period.Reference Gilbert, Dinh La, Romulo Delapaz, Kenneth Hor, Fan and Qi18 Likewise, it was observed that patients prescribed midazolam experienced fewer relative incidences of SRBs when compared to lorazepam (HR 2.373 (95% CI [1.089, 5.165] p = 0.0021) and clonazepam (HR 2.670 (95% CI [1.430, 4.988] p = 0.0297).Reference Gilbert, Dinh La, Romulo Delapaz, Kenneth Hor, Fan and Qi18 Midazolam was associated with reduced SRBs following FDR adjustment (p=0.0315).Reference Gilbert, Dinh La, Romulo Delapaz, Kenneth Hor, Fan and Qi18

Independently, it was reported that in patients diagnosed with MDD, clonazepam was not associated with a reduction in suicidality as indicated by the HAM-D.Reference Smith, Londborg, Glaudin and Painter19

Non-benzodiazepine gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)ergic sedative-hypnotics

We identified four studies that reported on the association between non-benzodiazepine GABAergic sedative-hypnotics and measures of suicidality. Studied agents include zolpidem (n = 2) and eszopiclone (n = 2).

Findings suggest that zolpidem reduces SI in insomnia disorder patients. It was also reported that improvement in SI was moderated by improvement in overall insomnia.Reference McCall, Benca, Rosenquist, Youssef, McCloud and Newman11, Reference Rumble, McCall, Dickson, Krystal, Rosenquist and Benca20 In patients exhibiting SI, insomnia, and depression, it was observed that zolpidem administration was associated with reduced long-term insomnia, which was, in turn, associated with a reduction in suicidal thoughts (Longitudinal linear association (beta) = 0.12, standard error (SE) = 0.04, p = 0.002).Reference McCall, Benca, Rosenquist, Youssef, McCloud and Newman11 Likewise, in an exploratory analysis using the same population, it was observed that zolpidem was not associated with a reduction in the SSI; however, a reduction in scores was significantly positively correlated to the improvement in insomnia (Longitudinal effect [autoregressive covariance] = 9.78, p = 0.002).Reference Rumble, McCall, Dickson, Krystal, Rosenquist and Benca20 Zolpidem was associated with a greater reduction in the C-SSRS SI scores in participants with severe baseline insomnia (−0.41 ± 0.21) versus those with mild–moderate baseline insomnia (−0.08 ± 0.15),Reference McCall, Benca, Rosenquist, Youssef, McCloud and Newman11 as measured by the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI).Reference McCall, Benca, Rosenquist, Youssef, McCloud and Newman11

Independently, in patients exhibiting both MDD and insomnia, eszopiclone + fluoxetine combination therapy was not found to be associated with an increased risk of suicidality relative to placebo + fluoxetine.Reference Krystal, Fava, Rubens, Wessel, Caron and Wilson21, Reference Fava, McCall, Krystal, Wessel, Rubens and Caron22

Orexin receptor antagonists

We identified 8 studies reporting on the association between ORAs and suicidality. Reported medications include daridorexant, lemborexant, and suvorexant. All RCTs assessed safety outcomes associated with ORAs wherein suicide-related outcomes were included as a safety measure.

Taken together, there was no increase in SI or SA. In patients diagnosed with insomnia, dariorexant, lemborexant, and suvorexant were not associated with an increase in SI or SA.Reference Rosenberg, Murphy, Zammit, Mayleben, Kumar and Dhadda23, Reference Herring, Connor, Ivgy-May, Snyder, Liu and Snavely24, Reference Uchimura, Taniguchi, Ariyoshi, Oka, Togo and Uchiyama25 Likewise, in patients diagnosed with both Alzheimer’s disease and sleep–wake rhythm disorder, lemborexant was not associated with an increase in suicidality as measured by the C-SSRS.Reference Moline, Thein, Bsharat, Rabbee, Kemethofer-Waliczky and Filippov26

Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia

Four studies investigated the anti-suicidal effects of CBT-I.

Studies suggest that CBT-I is effective in reducing SI. It was reported that CBT-I was associated with a reduction in SI in patients diagnosed with insomnia (Linear mixed model analysis (t) = −3.35, p = 0.001).Reference Jernelöv, Forsell, Kaldo and Blom14 Likewise, using the distribution of the PRODuct Confidence Limits for INdirect effects (PRODCLIN) program, it was observed that improvement in SI was moderated by an improvement in insomnia symptoms. (Estimate of indirect effect (αβ) = −3.20 (95% CI [−5.74, −0.87])).Reference Kalmbach, Cheng, Ahmedani, Peterson, Reffi and Sagong12 Group CBT-I is associated with reduced SI (Effect size (d) = −0.64, p = 0.01)Reference Chan, Lam, Zhang, Chan, Yu and Suh15; however, unguided, internet-based CBT-I transiently demonstrated a reduction in suicidal thoughts post-intervention (d = 0.13, p = 0.007), and not after a 6-month follow-up (d = 0.08, p = 0.303).Reference Batterham, Christensen, Mackinnon, Gosling, Thorndike and Ritterband27

Discussion

This systematic review provides the most recent assessment of sleep-related interventions on suicidality outcome measures. Overall, zolpidem and CBT-I are associated with a reduction in SI.Reference McCall, Benca, Rosenquist, Youssef, McCloud and Newman11, Reference Kalmbach, Cheng, Ahmedani, Peterson, Reffi and Sagong12, Reference Jernelöv, Forsell, Kaldo and Blom14, Reference Rumble, McCall, Dickson, Krystal, Rosenquist and Benca20 Alprazolam and midazolam are associated with reduced risk of SI, SA, and SC in comparison to lorazepam and clonazepam.Reference Higgins, Higgins and Thomas17 Similarly, ORAs are not associated with an increase or decrease in SI or SA.Reference Rosenberg, Murphy, Zammit, Mayleben, Kumar and Dhadda23, Reference Herring, Connor, Ivgy-May, Snyder, Liu and Snavely24, Reference Uchimura, Taniguchi, Ariyoshi, Oka, Togo and Uchiyama25, Reference Moline, Thein, Bsharat, Rabbee, Kemethofer-Waliczky and Filippov26 Our findings are in accordance with additional reviews suggesting that emerging evidence suggests that sleep interventions can be beneficial for suicidality; however, additional studies in more diverse populations, especially those highly comorbid with sleep disorders (e.g. substance use disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [ADHD]) are needed.Reference Mournet and Kleiman28, Reference Hertenstein, Trinca, Wunderlin, Schneider, Züst and Fehér29

Moreover, findings suggest that the efficacy of sedative-hypnotics and CBT-I in reducing SI are moderated by a reduction in insomnia symptoms. For example, zolpidem-mediated anti-suicidal effects were moderated as a function of changes in insomnia symptoms.Reference De Crescenzo, D’Alò, Ostinelli, Ciabattini, Di Franco and Watanabe10 Likewise, CBT-I displays SI reductive effects in insomnia patients, moderated by an improvement in insomnia symptomatology.Reference Jernelöv, Forsell, Kaldo and Blom14 However, the anti-suicidal effects of sedative-hypnotics are not entirely accounted for by improvements in insomnia, as alprazolam and midazolam broadly reduce SI, SA, and SC in patients diagnosed with PTSD.Reference Higgins, Higgins and Thomas17 Likewise, zolpidem’s anti-suicidal effects are associated with an improvement in depression, suggesting an underlying pleiotropic mechanism.Reference De Crescenzo, D’Alò, Ostinelli, Ciabattini, Di Franco and Watanabe10

Our findings have both clinical and research implications. Firstly, insomnia is established as a risk factor for suicidality.Reference McIntyre30, Reference Valentino, Teopiz and Wong31 Practitioners should be evaluating individuals presenting with psychiatric and medical disorders as to whether they are experiencing insomnia and should it be prioritized as a therapeutic target. Notwithstanding important safety information communicated by regulators and present package inserts alerting practitioners to the potential of suicidality associated with sedative-hypnotics, we did not identify a replicated body of literature documenting an increase in suicidality associated with any agent. Moreover, in many cases, either no effect or decreased ratings across aspects of SI and behavior were noted. In addition, CBT-I also, perhaps by improving symptoms of insomnia, manifests benefits across aspects of suicidality. From a research perspective, discerning neurobiological and cognitive mechanisms that link insomnia to aspects of suicidality is a priority vista. For example, it could be hypothesized that chronobiological disturbances are linked to changes in neurobiology that affect aspects of cognition and reward valence that may portend aspects of suicidality.Reference McIntyre30, Reference Valentino, Teopiz and Wong31

Several limitations affecting our inferences and interpretations should be noted. First, inconsistent definitions of the aspects of suicidality, as well as disparate measures of these dimensions were applied between studies, potentially affecting the internal consistency of our findings. Second, the heterogeneity of duration and enrollment populations affect the predictive validity of our data. Studies also varied with respect to whether aspects of suicidality were a safety measure or an efficacy outcome. Third, there were insufficient data concerning participant history of mental disorders and/or suicide. Fourth, studies varied in dosing regimens as well as the non-pharmacological interventions participants were receiving while enrolled in respective studies.

Taken together, our systematic review summarizes the extant literature evaluating the anti-suicidal effects of sedative-hypnotics and/or CBT-I. In turn, highlighting the efficacy treating comorbid insomnia has in reducing suicidality. Available evidence suggests that FDA-approved sleep aids do not increase suicidal risk. Further research should aim to identify the most effective ways to optimize the anti-suicidal effects of sedative-hypnotics and/or CBT-I, potentially through clarifying the mechanisms the aforementioned interventions influence when reducing SI.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852925000318.

Competing interests

Roger S. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) and the Milken Institute; speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes, Neumora Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sage, Biogen, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, Viatris, Abbvie, Atai Life Sciences. Dr. Roger McIntyre is the CEO of Braxia Scientific Corp.

Dr. Joshua D Rosenblat has received research grant support from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR), Physician Services Inc (PSI) Foundation, Labatt Brain Health Network, Brain and Cognition Discovery Foundation (BCDF), Canadian Cancer Society, Canadian Psychiatric Association, Academic Scholars Award, American Psychiatric Association, American Society of Psychopharmacology, University of Toronto, University Health Network Centre for Mental Health, Joseph M. West Family Memorial Fund and Timeposters Fellowship and industry funding for speaker/consultation/research fees from iGan, Boehringer Ingelheim, Braxia Health (Canadian Rapid Treatment Centre of Excellence), Braxia Scientific, Janssen, Allergan, Lundbeck, Sunovion, and COMPASS.

Kayla M. Teopiz has received fees from Braxia Scientific Corp.

Roger Ho has received National University of Singapore iHeathtech Other Operating Expenses (A-0001415-09-00),

Dr. Taeho Greg Rhee is supported in part by the National Institute on Aging (#R21AG070666; R21AG078972; R01AG088647), National Institute of Mental Health (#R01MH131528), National Institute on Drug Abuse (#R21DA057540), and Health Resources and Services Administration (#R42MC53154-01-00). Dr. Rhee serves as a review committee member for the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and has received honoraria payments from NIH, PCORI, and SAMHSA. Dr. Rhee has also served as a stakeholder/consultant for PCORI and received consulting fees from PCORI. Dr. Rhee serves as an advisory committee member for the International Alliance of Mental Health Research Funders (IAMHRF).

All other authors declare no disclosures.