Introduction

In June 1941, the clandestine communist newspaper De Stem der Vrouw published the following report on a demonstration by women in the Antwerp district of Deurne:

In Deurne, the women went to the town hall in large crowds. While the delegation was laying down its demands, a provocateur from VNV was sent up to address the women and urge them to demonstrate in front of the American embassy, to which the women did not respond, knowing full well that the occupier is the main culprit of our starvation.Footnote 1

This demonstration was part of a national propaganda campaign by the communist women’s movement against the German occupier. The communist resistance press called on women all over Belgium to demonstrate and loot to force a better food supply and undermine the legitimacy of the occupying forces.Footnote 2

In Antwerp, in May 1941 alone, sixteen women’s demonstrations and twenty-three lootings of bakeries and bakery carts by groups of women took place.Footnote 3 The local police and the occupier expected communist action in May 1941, a month including the symbolic dates of 1 May and 10 May, the end of the first year of the occupation. Still, no one expected communist women, in particular, to shake up the city so dramatically. On 18 April 1941, the Commissioner of the Judicial Police, George Block, detailed in a report how the party already had a highly developed illegal framework at the start of the occupation. Therefore, it could immediately proceed to ‘man-to-man agitation’ and to the clandestine production and distribution of leaflets and newspapers. The party – according to Block – also set up people’s committees. These were not allowed to carry out propaganda for communism but had to confine themselves to formulating demands regarding the food supply. They needed to maintain contact with the masses and organise demonstrations. Based on ‘profound surveys’ in various working-class circles, Block found that workers blamed the shortcomings and abuses regarding food supply on New Order movements. It was foreseeable that ‘in the coming times’, illegal communist propaganda would increase and that ‘the communist offensive has begun’. Indeed, the Antwerp judicial police were already planning numerous searches for illegal communist propaganda.Footnote 4

On 21 April 1941, a search took place at the home of the Antwerp leader of the communist women, Maria Govaerts, during which notes were found showing that communist women had an essential role in the illegal work of the Belgian Communist Party (KPB).Footnote 5 These notes stated that by establishing people’s committees, women were to engage in propaganda against the war. Possible actions were distributing pamphlets, publishing a clandestine newspaper for women and preparing mass demonstrations. An internal order from the KPB from March 1941 stated that:

Resistance against the occupying forces, which is growing in all sectors of the population, is based essentially on the growing discontent caused by the difficulties in obtaining supplies, the misery and the starvation of the population, who realise that this situation is due not only to the negligence of our former rulers, but also to the British blockade and above all to the occupation and their replacement by fascist-totalitarian institutions imposed by the occupying forces.Footnote 6

In the spring of 1941, the KPB combined a discourse that blamed both the Allied powers and Nazi Germany for the ‘imperialist’ war with a discourse of an anti-fascist struggle. Most importantly, it was clear that the occupier was the main culprit in the population’s misery and the main target for resistance actions.

Before the end of the non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, the lack of food was the most significant breeding ground for resistance actions against the occupier. Taking advantage of the miserable condition of the population, local cells of the party were to organise actions that discredited the occupier. The KPB stated in March 1941 that

through its victorious activity in the course of the last few months, in the strike movements, in the popular actions for the improvement of supplies and the anti-fascist demonstrations, the KPB has shown that it knows how to link the struggle for the bread of the workers with the struggle against the foreign occupier. . . . Before 1 May, every locality must organise demonstrations. Above all, it is necessary to insist . . . on certain forms of street demonstrations by considering the local possibilities and conditions.Footnote 7

During this period, the communist women’s movement organised women’s demonstrations and lootings. The communist women’s press reported on at least 142 demonstrations in eighty-one different locations across Belgium and presented these demonstrations as the primary form of ‘female’ resistance against the German occupier.Footnote 8

Some historians have questioned the political nature of these gatherings and suggested that they do not qualify as political resistance against the occupying forces. In this interpretation, the gatherings were the result of a material need and did not focus on the Nazi occupation.Footnote 9 My research suggests otherwise. By taking a more capacious definition of resistance as any activity directed against the aims of the German occupier, forbidden by the occupier and thus involving real risks for its perpetrators, the activities of communist women can be cast in a different light.Footnote 10 The occupation of Belgium involved not only military and political oppression but also economic exploitation, essential to support the German war effort. Thus, women’s demonstrations and lootings were not just expressions of social discontent but also political actions in the form of illegal propaganda against the occupier. Not all the participants in these demonstrations and looting will have understood or shared the view articulated in communist propaganda of the time. Nevertheless, they were engaged in resistance visible to bystanders.Footnote 11 Moreover, the communist militants who organised these actions very consciously sent these women into the streets; for them, this was as much an expression of a political commitment as handing out pamphlets.

In the past, Belgian resistance historiography has examined almost exclusively resistance organisations and activities as they existed at the time of the liberation of Belgium in September 1944. These studies emphasised the professionalism of resistance organisations and rarely paid attention to amateurism or experimentation with different forms of resistance.Footnote 12 This article, by contrast, examines precisely the earliest period in the development of communist resistance. The fact that the demonstrations and looting took place in the spring of 1941 was no accident but part of the Communist Party’s strategy in this early period. In late 1940 and early 1941, the Communist Party sought ways to mobilise the population for resistance. The period from the beginning of the occupation on 28 May 1940 to the German invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941 – when the non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union was still intact – was the period when resistance was ‘invented’. Propaganda played an essential role for all resistance groups at this early stage by emphasising the harmful consequences of the occupation and encouraging people to resist.Footnote 13

It is important to remember that the KPB was in an ambiguous position during this first year of occupation. Since the signing of the German–Soviet non-aggression pact in August 1939, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union had become geopolitical and economic partners, although they remained ideological enemies. At the start of the occupation, the KPB was tolerated by the German occupation regime. However, German intelligence services were actively gathering information about communist activity and also already arresting several communist militants. From the start of the occupation, the KPB published clandestine newspapers and pamphlets in which – despite blaming both the Allied powers and Nazi Germany for the war – it mainly targeted the occupying forces and Belgian collaborationist groups. The women’s demonstrations and looting during the spring of 1941 illustrate the difficult position in which the KPB found itself. These actions were not especially violent, nor were they too threatening to the occupier. But they did send a message that the occupier was to blame for the miserable living conditions of the Belgian population and that communists were prepared to fight to improve them. Women’s demonstrations and lootings show that in this early period, the KPB could already organise propaganda actions on a national scale. After May 1941, there were no more women’s demonstrations in Antwerp. With the entry of the Soviet Union into the war on 22 June 1941 and the subsequent radicalisation of the communist resistance and its persecution, it was clear to everyone that the occupying forces did not hesitate to repress any attack on public order.

Since the 1980s, historians of the French resistance, like Claire Andrieu and Paula Schwartz, have called for research on women’s resistance activities, such as sheltering people in hiding and women’s demonstrations.Footnote 14 To this we need to add the role of the communist movement in mobilising women, especially housewives, in so-called people’s committees. These formed the basis for organising protests against poor living conditions through petitions, strikes, demonstrations and looting to awaken public opinion. In the case of France, there has been limited research on communist women’s demonstrations.Footnote 15 Ivan Avakoumovitch and Danielle Tartakowsky have both produced important work based on the clandestine communist press and reports from local authorities and the occupying forces.Footnote 16 In Belgium, it was not until 1992 that women’s demonstrations were mentioned in resistance historiography, with the publication of José Gotovitch’s study of the resistance activities of the KPB. Gotovitch argued that the message emanating from these demonstrations was anti-German, even if the protesters’ banners and slogans referred exclusively to food problems and did not attempt to provoke the occupier.Footnote 17 Building on this, the resistance historian Fabrice Maerten has shown clearly that the occupier understood women’s demonstrations as political actions by the KPB and that they can be classified as ‘political and ideological resistance’.Footnote 18 However, neither Gotovitch nor Maerten give much detail about the protests themselves. How were they organised? How many of them took place, and where, and which women participated? How did local or German police deal with them? This article endeavours to answer some of these questions. Using new archival materials, I analyse women’s demonstrations in the strategic port city of Antwerp. A wealth of information on the demonstrations, lootings and the women arrested and tried for their participation is available in police and judicial archives.Footnote 19 No other Belgian city has such a diverse corpus of sources available for the occupation period. Alongside these archives, I have examined the Archives Service for War Victims (ASWV) and the State Archives (SA).Footnote 20 I have also examined, among other things, the individual files of the KPB’s Political Control Committee (PCC), as well as a thorough investigation of the communist press, the resistance press and post-war party newspapers.Footnote 21

‘Only Women Should Act’: A Campaign of the Communist Women’s Movement

On the night of 14–15 May 1941, two women posted notes in the mailboxes of several houses in Antwerp district of Deurne that read as follows:

Mothers, women! Hunger is pressing, misery is increasing daily, our children are already suffering from malnutrition, urgent improvement is needed. Therefore, demand with us on Thursday, 15 May at 11 a.m. in front of the town hall: more bread, potatoes, fat, more milk. Protest with us by keeping your children out of school on this day. All without exception on 15 May at 11 a.m. at the town hall. The People’s Committee. Please pass on.Footnote 22

Alarmed by these notes, the Deurne police were on extra alert on 15 May 1941 for gatherings or demonstrations and specifically watched the Cogelsplein, the location of the weekly market. Around 11 a.m., Anna Slenders led a group of protesting women into the square. She carried a banner that read: ‘We demand: potatoes for our stamps; more milk, bread and fat. Now!’Footnote 23 The police officers immediately dispersed the group and most women complied. Four women continued to urge bystanders to demonstrate and were, therefore, arrested. These women were thirty-three-year-old housewife Anna Slenders, twenty-eight-year-old servant Carolina Driesen and two labour women, thirty-six-year-old Josephina Huygens and fifty-nine-year-old Joanna Meerlemont. By bringing the banner to the market, Anna Slenders had wanted to provoke a gathering in front of the town hall. Carolina Driesen’s husband, Joannes Cauberg, had made the banner on the evening of 14 May 1941. Carolina Driesen said she formed the ‘People’s Committee of Deurne’ with Anna Slenders, Josephina Huygens and Huygens’ mother. There were other women affiliated with this people’s committee whose names she did not recall. The women had first met each other while waiting for milk distribution and discussing the rationing issue. Carolina Driesen confessed that she had distributed the notes together with Josephina Huygens. While searching Carolina Driesen’s home, police discovered several copies of this note and cards that read: ‘Good for a trip to Berlin – see the reverse – For V.N.V., Rex, Verdinaso and S.S. and never return’.

According to Carolina Driesen, the Deurne people’s committee did not have a permanent seat and its meetings alternated at the home of one of its members. The committee aimed to send complaints about food supply to the mayor. In the absence of improvement, they decided to organise a demonstration. At Carolina Driesen’s home, police also found another note containing several questions, apparently in preparation for a report on the working of the people’s committee, including: ‘1) How many seats does the committee have? Where are they located? 2) Number of meetings, date, number of people present per meeting, how many men, how many women, how many party members, how many sympathisers?’ Confronted with this note, Carolina Driesen changed her story and explained that the people’s committee – of which she had been a member since January 1941 – had already been established one month after the German invasion on 10 May 1940. A thirty-year-old woman had come to see her to ask her to join the committee. Apparently, the committee was not formed after a spontaneous meeting in the milk queue after all. People’s committees were already known to the Antwerp police, as was the link between them and the KPB. On 18 April 1941, in a report on the operation of the KPB, judicial commissioner George Block concluded the following:

Such [people’s] committees are found mainly in large centres. Outwardly, they would not carry out propaganda for communism but would merely be determined to put forward specific demands concerning the food supply. These committees should maintain contact with the masses and could possibly organise demonstrations in connection with the regulation of the food supply, which, especially in the large centres, is not always efficient.Footnote 24

According to testimonies about other incidents, the slogan of the people’s committees was that ‘only women should act and men should show themselves as little as possible’ and that looting had to be done by people living on the other side of the city so that bystanders and the police would not recognise them.Footnote 25

The local police of Deurne sent copies of the police report containing these testimonies to the chief of the Judicial Police and the head of the German military police – the Feldgendarmerie – in Antwerp.Footnote 26 This aspect of the story confronts us with the delicate situation of the Antwerp local and judicial police in the prosecution of the women’s demonstrations and looting. Because of the limited size of the German military occupation force, the occupying regime called in the Belgian police and judiciary to maintain public order. Belgian prosecutors were asked to pass criminal reports to the German police. This posed a problem for the Belgian police and judiciary because the German police used their work to track down Belgian citizens.Footnote 27 A few days after their interrogation by the Deurne police, Carolina Driesen, Anna Slenders, Josephina Huygens, Joanna Meerlemont and Johannes Cauberg had to report to the Gestapo headquarters in Antwerp. They were allowed to return home after interrogation but received a summons to appear before the German Feld-Kriegsgericht in Antwerp on 1 July 1941. The three women who confessed to being committee members were sentenced to three months imprisonment in the German section of the Antwerp prison. Cauberg was sentenced to four months imprisonment and Meerlemont to two weeks. Cauberg received the most severe sentence, as, according to the judge, he created the banner that made more people join the demonstration and ‘stronger inhibitions against the crime were expected from him than from the accused women’. The German judge was thus more understanding of the women than of Cauberg. The belief that women were naturally more peaceful and that public actions by women were perceived as less threatening than actions by men played a role in the communist strategy of sending women into the streets.Footnote 28 The German Feld-Kriegsgericht stated that unauthorised marches and assemblies could not be tolerated under any circumstances as they could become a risk to the occupying power. However, the fact that the population received insufficient food in May and June 1941 was considered a mitigating factor.Footnote 29 On 11 September 1941, the Antwerp correctional court summoned the same five individuals for publishing illegal print and participating in an illegal demonstration. They were acquitted, as they had already been convicted for the same offences by the Feld-Kriegsgericht.Footnote 30 After the war, only Carolina Driesen and her husband, Joannes Cauberg, applied for recognition as political prisoners. Driesen was recognised, but Cauberg was not because, after his imprisonment, he went to work in Germany voluntarily. None of the arrested applied for recognition as resistance members.

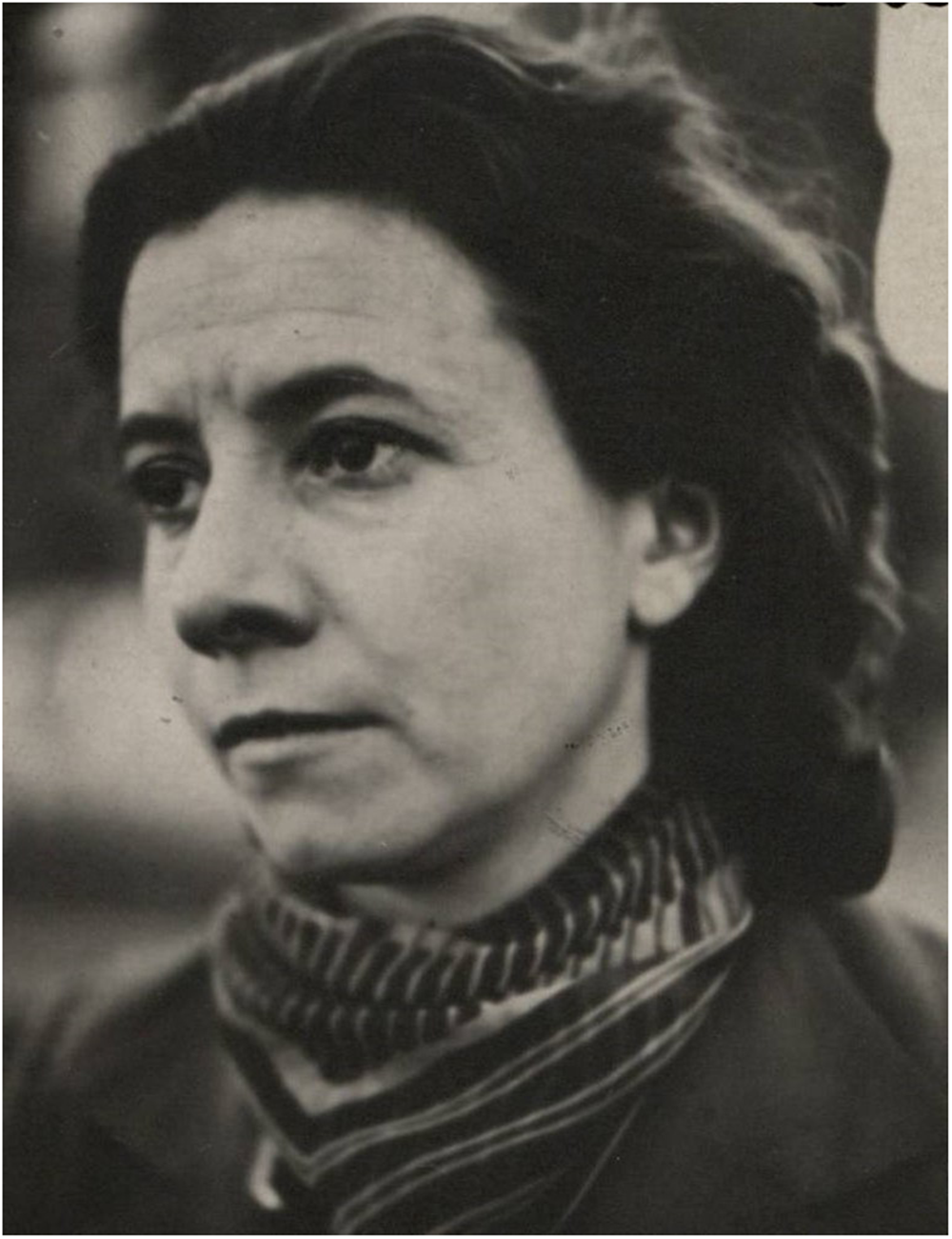

The woman who had recruited Driesen for the people’s committee was probably Maria Govaerts, twenty-eight years old at the time of the demonstration. Initially recruited for the party by Gilberte Borgers (Figure 1) in 1937, Govaerts led the Antwerp section of the communist women’s organisation from 1938.Footnote 31 She founded women’s groups throughout Flanders, organised political training for women and managed the women’s newspaper De Stem der Vrouw. She continued these activities during the occupation and founded the people’s committee in Deurne. Govaerts was the head of this committee, which, according to her, had forty members, and she recruited women by making house calls. A house search by the officer of the judicial police George Block in September 1941 – the second, after the first one in April 1941 – made her go into hiding. Govaerts left Antwerp and became active in Ghent, where she revived the women’s movement and organised a strike of textile workers. On 30 August 1942, the Gestapo arrested Govaerts in Ghent. After imprisonment and torture in the Ghent prison, the Breendonk prison camp, the Antwerp prison and the Brussels St. Gilles prison, she was deported to Ravensbrück concentration camp in June 1943.Footnote 32 Maria Govaerts survived her imprisonment and resumed her position in the Antwerp Federation of the communist party after liberation. She was recognised as a political prisoner in 1948 but not as a member of the resistance, as she refused to deliver any statement or documentary evidence about her activities to the government commission that granted these statutes.Footnote 33

Figure 1. Photo of Gilberte Borgers. Source: ASWV, File Documentation and Research Service Gilberte Borgers.

Maria Govaerts was recruited to the KPB by Gilberte Borgers, who led the Flemish section of the communist women’s movement as early as 1936. At the start of the occupation, Borgers lived in the Antwerp district of Hoboken with her two children. Her husband, François Lepomme, died fighting with the International Brigade during the Spanish Civil War in 1937. From the beginning of the occupation, Gilberte distributed communist propaganda. In May 1941, she was known to the court ‘as being a prominent communist and one of the fiercest propagandists’.Footnote 34 On Monday, 26 May 1941, Borgers delivered a speech to women at the vegetable market in Hoboken. She reportedly said: ‘It’s a shame that everything is expensive now; it’s the time to demonstrate for more bread, potatoes and food in general’. Borgers suggested meeting at the church around 10 a.m. the next day and marching to the town hall. Indeed, on 27 and 28 May 1941, 800 women and children, carrying banners and black flags, demonstrated at the Kioskplaats in Hoboken. Anna Scheerder walked in front, holding a black flag. At Borgers’ request, Scheerder had made this flag out of an old, worn-out apron. When Scheerder wanted to give the black flag to Borgers, the latter refused to carry it. Borgers walked behind Scheerder and recited what the women should shout. If gendarmes came, the women had to shout ‘Awoert’ and ‘parasites of the government’.Footnote 35 Frans Spiessens expressed similar insults during this demonstration: ‘You are cowards, traitors to your country, bastards, you are not yet worthy of being shot in the head.’ The insults of Elisabeth Borgwardt fit into the same discourse: ‘You are a coward with all your gang, you are not hungry, you have your cellars full of food, on 10 May you were the first to run, coward!’Footnote 36

The police announced that Mayor Jozef De Coster would receive a delegation of women.Footnote 37 Anna Scheerder, Elisabeth De Kok, Leontine De Beucker and Joanna Van Der Meynsbrugge volunteered to form this delegation. By not wanting to carry the black flag herself and by not being part of the delegation, Gilberte Borgers deliberately kept a low profile. The women who walked in plain sight by hurling insults, carrying the flag or being part of the delegation were the ones who got arrested. Gilberte Borgers’ arrest would immediately expose these demonstrations as communist actions and the party wanted to avoid this. The meeting between the women and Mayor Jozef De Coster at the town hall was interrupted by the German Feldgendarmerie. They brought the women to the Hoboken police station and detained them there from 5 to 10 p.m., when they were released.Footnote 38 To the judicial police, Elisabeth De Kok stated that she only participated in the demonstration because she had neither bread stamps nor bread left at home and her children were asking for food. Joanna Van De Meynsbrugge also declared that she participated in the demonstration because her husband was unemployed and she was very short of food for her four children.Footnote 39 In a letter to provincial governor Jan Grauls about these demonstrations, Mayor De Coster understood the protesters’ situation.Footnote 40 De Coster hoped for the governor’s benevolent intervention in the ‘prevailing misery of our housewives and their children’; he attached a copy of the pamphlet he received from the protesting women.Footnote 41 This hard-to-read and seemingly hastily drafted text was entirely in line with the propaganda before and during the demonstrations. The women, who called themselves ‘the bearers of the black flag’, complained that their children and men could no longer go to school or work because of hunger. They demanded potatoes, soup, milk and chocolate.

The Antwerp police never managed to arrest or question Gilberte Borgers about her role in these demonstrations. When the judicial police showed up at Borgers’ house on 9 June 1941, they found only a six-year-old child alone. The house search yielded no results and Borgers never responded to the summons for questioning.Footnote 42 Almost immediately after the demonstrations in Hoboken, Borgers went into hiding in West Flanders and started working as a recruiter and courier for the Armed Partisans.Footnote 43 On 14 April 1942, the Gestapo arrested her at her hiding place in Rumbeke and imprisoned her in Ghent. In July 1942, she was deported to Germany, where the Sondergericht in Essen sentenced her to death for communist propaganda. On 28 April 1944, she was executed in Katowice.Footnote 44 After the war, Gilberte Borgers was recognised as a political prisoner. She received recognition as an armed resister for her activities for the Armed Partisans.Footnote 45

When Hunger Protests and Looting Become Resistance

Women’s demonstrations were both spontaneous expressions of social unrest and conscious political actions orchestrated by female communist militants. These actions were not unique to Antwerp but took place all over Belgium in the spring of 1941. Public demonstrations for better food supplies were the dominant female resistance activity propagated in the communist resistance press from May 1941 to August 1944.Footnote 46 As mentioned earlier, the communist press reported on 142 women’s demonstrations that occurred during the occupation in eighty-one different locations throughout Belgium. It is difficult to determine how many individual demonstrations these figures represent, as reports on the demonstrations in the clandestine press gave little detail and rarely included a date. Moreover, we do not have a clear picture of the scale on which looting occurred. Most demonstrations and looting took place in the provinces of Liège and Hainaut, while the clandestine press reported no actions for Limburg and Luxembourg. This observation is not surprising since Liège and Hainaut were industrial centres with a strong tradition of strikes and demonstrations, even before the occupation and a strong presence of the KPB. In contrast, in Limburg and Luxembourg, the KPB was absent at the start of the occupation.

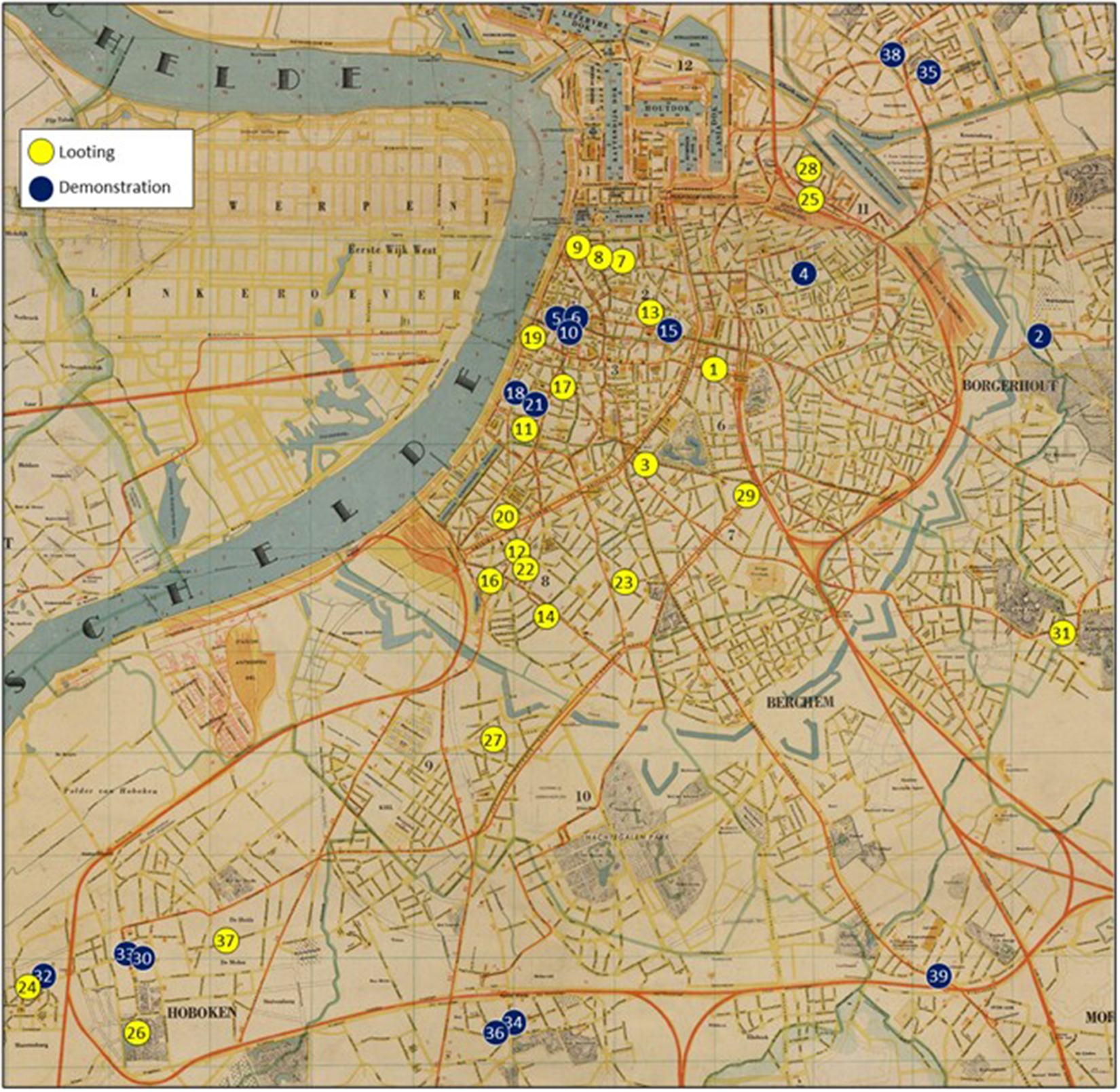

While the communist clandestine press reported nine women’s demonstrations for the city of Antwerp, my research shows that this is an underestimation. At least sixteen demonstrations and twenty-three lootings took place in May 1941 alone. The lootings started earlier than the demonstrations. On 5 May, ‘a group of unknown women’ stole a bakery cart containing 100 loaves of bread in De Keyserlei in Antwerp (Figure 2, nr. 1). However, the centre of gravity was in the last week of May: between 23 and 29 May, we count twenty-one lootings. The most notable incident was the looting and destruction by a thousand men, women and children of a bakery in the Prinsesstraat on 26 May (Figure 2, nr. 13). According to witnesses, the looters had first tried to raid a bakery cart, which failed, after which the group raided Jan Snoeys’ bakery:

They invaded my store and even went into my kitchen and wanted to break open the cellar door, which I was able to prevent. The troop was possibly a thousand strong; they were men, women and children. I saw no familiar faces among the raiders and could not recognise anyone. Nor can I give you any information enabling you to trace the perpetrators.

Figure 2. Overview of women’s demonstrations and lootings in Antwerp, May 1941. Source of Map: CAA, 12#887: Map of Groot-Antwerpen, 1943. Source of Data: List of Women’s Demonstrations and Lootings in Antwerp, May 1941, See Annex I.

The troops destroyed the bakery and the police found it difficult to control the crowd:

Our repeated pleas to clear the street and restore order were ineffective, so we were obliged to use the sabre. . . . Given the large crowd and the small number of police officers, we could not make arrests to prevent worse. In Jan Snoeys’s bakery store, 320 loaves of bread were stolen before our arrival.Footnote 47

After 29 May, looting became sporadic and there were no more mentions of groups of women involved.

The first demonstration occurred on 15 May in Deurne (Figure 2, nr. 2). The following two demonstrations occurred on 21 May in the Seefhoek in Antwerp and on the Grote Markt, the city’s main square. Over the next five days, seven more demonstrations took place in the city centre. From 27 to 31 May, eight other demonstrations were staged in Hoboken, Wilrijk, Merksem and Mortsel. Mostly, several hundred women demonstrated. The highest number, around 800, was counted on 27 May in Hoboken, a community with a working-class profile and a sizeable communist presence.

Most participants, during both the demonstrations and the lootings, claimed they were there by chance and argued that the demonstrations and lootings were spontaneous actions. For example, Maria de Munck, a thirty-year-old housewife who participated in a demonstration on 26 May 1941, on the Kloosterstraat (Figure 2, nr. 18), was arrested by German Feldgendarmerie and interrogated the next day by SS Untersturmführer August Fest.Footnote 48 Maria de Munck claimed she was there by chance and had not participated in the demonstration. Fest dismissed her statement as implausible. According to him, de Munck lived in a neighbourhood where such events were discussed daily. All other women interviewed in other cases also made the same statements. Fest concluded that these demonstrations were organised in advance and that the participants were instructed about the statements to be made. The Gericht der Feldkommandantur 520 concluded that it could not be proven that de Munck belonged to a political party. Therefore, she should not be regarded as a rioter but a follower. She was released on 27 May 1941 as she had four children to care for and there was no fear of escape. She was still summoned to the correctional court in Antwerp for participating in an illegal demonstration but was acquitted on 13 August 1941.Footnote 49

Arrests were made for only four lootings, in each case of people who lived on the same street where the looting had taken place and were therefore recognised by the victims. The most striking example was the looting in Twee Netenstraat on 27 May (Figure 2, nr. 28), where a group of about thirty-five women stole more than 150 loaves of bread from the bakery cart of baker Frans Somers and the police arrested thirteen people living on this street. It seems that the whole street participated in this looting.Footnote 50 Martha Balemans, who ran a grocery store on the same street, testified to this:

I cannot give you the slightest information, for the good reason that it has not been spoken of again, from the moment the plundering took place. Furthermore, I think it is useless to declare to you that there is great solidarity among the people and that, particularly in this case, no one will be found who will say anything of another.

The judicial police officer, however, concluded in his report that intelligence had shown ‘that the initiative concerning the looting of baker’s carts would emanate from about two persons who . . . would belong to the communist party’.Footnote 51 Looting preferably did not take place in one’s neighbourhood. It was an explicit directive of the KPB to loot in other neighbourhoods so as not to be recognised by the police. Police, gendarmes and victims repeatedly noted that the looters were ‘from another neighbourhood’.Footnote 52

In total, ninety arrests were made, comprising eighty individuals: seventy-five women and five men (as ten women were arrested twice). Fifty-five people were arrested during a demonstration and twenty-five during a looting.Footnote 53 Rarely did the police resort to violence and the main focus was on negotiation to quieten the mood. The mayors tried to please the delegations of women with promises of improved food distribution. However, their answers were not always satisfactory, as illustrated by the demonstration of 23 May 1941 at the Grote Markt, Antwerp’s main square. One of the protesters, Maria Carpentier, testified, ‘Five women went to see the mayor and while they were in the cabinet, we walked around waiting for the answer. The mayor’s answer was unsatisfactory, considering it always sounds the same: “I will arrange for potatoes”, and we never obtained any’. After the consultation with Mayor Leo Delwaide, the demonstrators left the Grote Markt and marched towards the nearby headquarters of the provincial government.Footnote 54 Governor Grauls admitted a delegation of five women for a consultation.Footnote 55

Table 1. List of women’s demonstrations and lootings in Antwerp, May 1941. The numbers in the first column refer to the numbers on the map in Figure 2

The correctional court of Antwerp summoned a total of twenty-four people for their participation in an illegal demonstration. In some cases, an allegation of illegal press or slander of the police was added. Seven trials took place between 5 July 1941 and 13 October 1941. Of these twenty-four persons, ten were convicted of participation in an illegal demonstration and three of slander. Notably, all the persons in the first four trials were convicted and all those in the last three trials were acquitted. Among these acquittals, we find Maria de Munck and those involved in the above-described demonstration in Deurne, all of whom also appeared before the German Feld-Kriegsgericht. This might be related to the change of attitude of the judicial authorities toward these demonstrations, but we cannot be sure.

On 30 June 1941 – in a report on the women’s demonstration in Merksem on 29 May 1941 – judicial commissioner George Block concluded that the initiative for the women’s demonstration came from the local branch of the communist party.Footnote 56 Block’s exchange with the Hoboken deputy police commissioner on 7 July 1941 revealed that the Feldgendarmerie closely followed these demonstrations, as we have already seen in the examples of Deurne and Hoboken. Block noted that the situation of the Hoboken police in this matter was very delicate: the Feldgendarmerie demanded a copy of all police reports.Footnote 57 As mentioned, in 1941, the judiciary agreed to transfer potentially interesting files to the German authorities. For the judiciary, this caused a moral and legal problem: in Belgian law, exposing citizens to prosecution by the enemy was considered a crime against the state’s security. Eventually, by the end of 1942, the Brussels public prosecutor reacted with a clandestine order to the judiciary police: where political violence was concerned, they had to ensure that official reports did not include valuable evidence or information.Footnote 58 However, in May and June 1941, George Block still operated in a political climate that could inspire little sympathy for communists. Germany and the Soviet Union were not at war until 22 June 1941 and were considered allies by many. Indeed, at least until May 1941, all public prosecutors instructed the judicial police to gather information about communist underground activity. It was only after the German invasion of the Soviet Union that the climate changed and active intelligence-gathering in connection with underground communist activity ceased, at least in theory.Footnote 59 On 7 July 1941, a week after Block stated that the initiative for the women’s demonstration in Merksem came from the local branch of the KPB, he declared that ‘these demonstrations that took place both in Hoboken, Wilrijk, Mortsel and Merksem have no political character whatsoever’. In light of this context, we can understand why Block tries to deny the political nature of women’s demonstrations. He concluded that he believed that ‘between these various demonstrations, we must seek no connection or political motivation’. In the report, he added a list of people mentioned in police reports about the demonstrations in Hoboken, Wilrijk, Mortsel and Merksem. Furthermore, Gilberte Borgers’ name was absent from this list while the correctional court still prosecuted her for participating in the demonstrations. Omitting her name from this list was possibly an attempt to negate the political nature of the demonstrations.Footnote 60

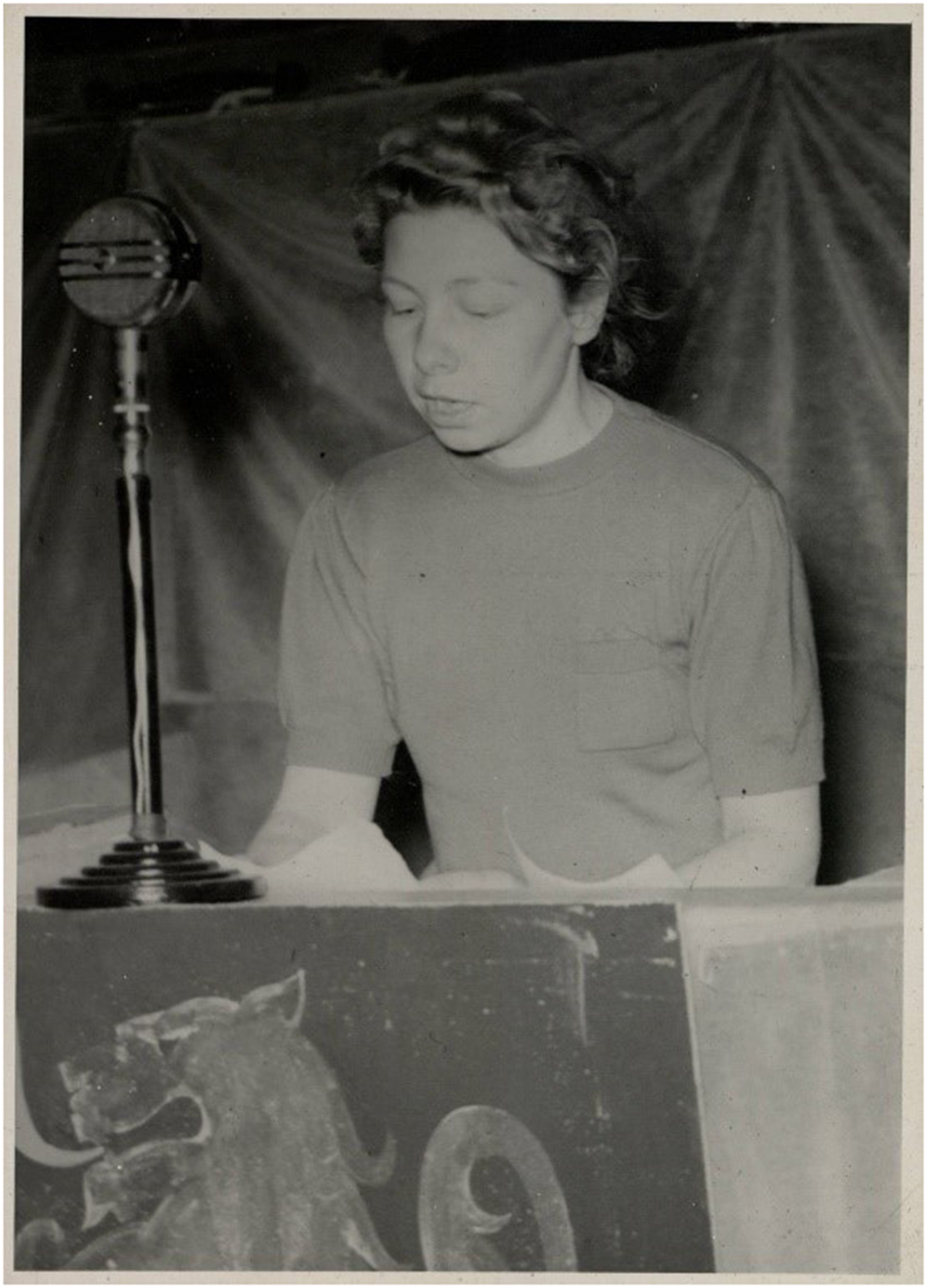

The youngest arrested was Jeanne Letroye, who was fourteen years old when she participated in a looting in the Halfmaanstraat in Antwerp. Interestingly, the oldest arrested took part in the same looting on 26 May, Louisa D’Hooghe, who was sixty-five years old. Sixty-six per cent of the arrested were between twenty-six and forty-five years old. This is not entirely unexpected, as this is the age when women generally start a family and also have to support it. This group was the biggest victim of poor food supply and probably the easiest to motivate for a demonstration or looting. At the same time, this group of women is traditionally expected to avoid risk, as mothers are expected to be peaceful and caring and not to jeopardise their family’s stability by participating in illegal actions. But 75 per cent of the arrested were married and 74 per cent had at least one child. For sixty-one arrested persons, we have information on their jobs; twenty-six women were housewives or had no profession and fifteen worked as housekeepers. Generally, the women arrested during demonstrations or looting were married mothers aged between twenty-six and forty-five, performing unpaid labour.Footnote 61 We cannot specify how many women in our sample were ‘followers’ or ‘instigators’. We know that Maria Govaerts and Gilberte Borgers led these demonstrations and probably also incited groups of women to loot. Outside Antwerp, too, it was experienced communist militants who organised women’s demonstrations and looting. Jeanne Cornand in Aalst (Figure 3), Suzanne Grégoire (Figure 4) and Alice Adère-Degeer (Figure 5) in Liège, Juliette Hermans (Figure 6) in Brussels and Félicie Mertens (Figure 7) in Charleroi all had experience organising political action and recruiting women to the KPB before the occupation and continued to do so during it.

Figure 3. Jeanne Cornand in 1938. Source: CArCoB, Het Vlaamsche Volk, September 1938.

Figure 4. Suzanne Grégoire, picture from the 1940s (undated). Source: CArCoB.

Figure 5. Alice Adère-Degeer in 1945. Source: CArCoB.

Figure 6. Juliette Hermans in 1938. Source: Resistance Museum Anderlecht.

Figure 7. Félicie Mertens in 1946. Source: CArCoB.

These demonstrations were similar to what Fabrice Maerten observed for the province of Hainaut. Here, the majority of women's demonstrations also occurred in May 1941. Maerten confirms that the women’s demonstrations were part of a campaign orchestrated by the KPB but does not give figures on the estimated number of demonstrations or lootings. The women carried black flags and demanded better food supplies and the liberation of prisoners of war. According to Maerten, the KPB believed it could avoid the occupier’s repression by mobilising women for action. Demonstrations, symbolic gestures and strikes were a long-standing resistance practice among the working-class population. The arrest wave of 22 June 1941 disrupted the KPB for some time and, according to Maerten, was why we only see women’s demonstrations re-emerge in the spring of 1942. Mass arrests in 1942 discouraged the KPB from making another attempt until July 1944. In the summer of 1944, this action was probably intended as a stepping stone to a general uprising.

Still, unlike Hainaut, in Antwerp, we see no new campaign of demonstrations or looting after May 1941.Footnote 62 We already saw that the leaders of the Antwerp and Flemish communist women’s movements went into hiding and left Antwerp after the demonstrations of May 1941. By the end of 1942, the occupier had arrested Maria Govaerts and Gilberte Borgers. This seems a more likely explanation for why there was no similar campaign of demonstrations and looting after May 1941 than the situation of food distribution. Although hunger was a breeding ground for these actions in May 1941, this is an insufficient explanation as to why these actions took place just then. Belgium had always depended mainly on overseas shipments for its food supplies. Because of the British blockade of continental European ports in May 1940, the country had to rely on supplies from Germany. This caused food shortages almost immediately. On top of this came the German requisitions and the fact that the occupying forces also bought up large quantities of scarce goods. The daily ration was already low and people were not getting what they were entitled to under this rationing. The inadequate food supply generally did not improve after May 1941 but continued throughout the occupation.Footnote 63

Looking beyond Belgium, the Antwerp demonstrations are comparable to those that took place in France, where most agree that demonstrations were part of a communist resistance strategy. As such, the Parti communiste français (PCF) took advantage of food shortages to organise demonstrations and women who were already politically active in the communist women’s movement before the occupation. The protests began in the first half of 1941 in places with a strong communist presence but later spread to more right-wing regions in the south. Avakoumovitch has documented more than 300 locations where at least one protest occurred. Working-class women, the group most affected by poor living conditions, comprised most of the participants.Footnote 64 One event in France was an exception to the overall image of the women’s demonstrations. On Mother’s Day (31 May) 1942, an exceptionally violent incident occurred on the rue de Buci in Paris. Two policemen were killed, and, as a result, forty participants (both men and women) were arrested and ten people who were connected to this incident were executed. The violent course and dramatic consequences of this incident are related to the changed context of May 1942, when communist resistance and its repression radicalised in both France and Belgium. Another significant difference from the demonstrations and looting in Antwerp in May 1941 was the involvement of men. Women played the leading role, mingling in the long queue of people waiting in front of the shop doors, and as soon as the signal was given, they called out to loot the shop. Men acted as passive observers and effectively formed a backup security team. Some of these men – members of underground partisan groups – were armed, but most were not. The profile of the forty protesters arrested also differed from that of the protesters in Antwerp: most had a paid job and only one was a housewife. Nevertheless, the age ranged from late twenties to early forties, as in Belgium; the majority had children.Footnote 65

In the spring of 1941, when there was perhaps still an illusion that it was possible to negotiate with the Germans, these lootings were a way of putting pressure on the occupier. The women who demonstrated and looted had power over an essential commodity for the occupier: social peace. They used this to obtain what was precious to them: enough food to feed their families. A year later, when both the resistance and the occupier were highly radicalised, such action was much more challenging to justify and organise. It was then clear to everyone that the occupying forces did not hesitate to violently suppress any attack on public order. When, in June 1941, the entire leadership of the KPB went underground, the organisation of these ‘public’ and ‘aboveground’ actions became less evident. Sabotage increased from the summer of 1941, and from a strategic point of view, there was less need for women’s demonstrations as a public action.

Conclusions

This article analyses the May 1941 women’s demonstrations and looting in Antwerp as a form of political resistance. Starting from what was perhaps the most traditional female role – a mother feeding her children – the clandestine communist women’s press mobilised women for the most active and public form of citizenship: taking to the streets to protest the lack of food. It was the women’s job to deprive the occupiers of food, fuel and labour, thus sabotaging the German war effort. Paradoxically, it was the same clandestine communist women’s press that embedded women’s participation in a traditional view of women, to the extent that this even camouflaged the resistance nature of female activities. Party propaganda placed women in their roles as housewives and mothers. Women’s demonstrations and clandestine aid did not threaten the traditional image of women in the 1940s but confirmed it.

Interestingly, the propaganda inciting women to demonstrate and loot was considered resistance by the commissions deciding on recognition after the war, but demonstrations and lootings were not. Subsequently, most participants likely did not identify as resistance members after the occupation and did not apply for recognition even when their actions had led to imprisonment. However, the protests discussed in this article were, in my view, a form of illegal propaganda against the occupier, which was underpinned by conscious political action aimed at mobilising large groups of women for the resistance struggle. They may not have achieved this goal, but, at least for the women who organised these demonstrations, this was an essential part of their resistance trajectory, which started early in the occupation and often ended in arrest and deportation.

After the war, few, if any, communist women were remembered because of their role in this activity, primarily not by the communist party. Within the party after the war, ‘heroic memory’ prevailed and the memory of armed partisans and political prisoners came to dominate.Footnote 66 However, participation in early women’s demonstrations led to persecution and punishment by the German occupation forces, who were well aware of the political meaning of these actions. An occupied population taking to the streets to protest, thereby undermining the legitimacy of the occupier, was, in the eyes of the Germans, a clear danger. Denying the legitimacy of the occupier was the first way for the population to resist. Strikes for better food distribution aimed not to destroy the enemy but rather to correct the most intolerable daily effects of the occupation. This kind of action happened outside all military logic.Footnote 67 A population that refused to let the German occupiers transport food and fuel to Germany was as much in resistance as a population that resisted the deportation of political prisoners. This was resistance to the country’s economic exploitation and economic – and ultimately military – gain for the enemy.

In this article, we have encountered a group of women largely absent from resistance historiography: working-class mothers and women. The power of this group lay in its members’ identities as women and mothers. Through their demonstrations and protests, they exposed the occupier as the enemy and showed that resistance was an option. They were essentially non-threatening, and violence against this group would have been disastrous for public opinion. In this particular early period of the occupation, this identity gave them leeway to show their discontent with the occupier’s New Order. By the same token, my analysis of women’s actions in this period demonstrates the difficulties in defining resistance. Contemporaries and the clandestine communist press considered their actions as resistance, but, after the war, this was questioned, as memory of – and research on – resistance became dominated by professional organisations with a clear political–ideological orientation, structured according to a military hierarchy, with strong leaders who waged a patriotic struggle. But a closer examination of women’s non-armed resistance reveals a more nuanced picture, challenging traditional definitions of ‘real’ resistance. Instead of simply ‘adding’ women to the existing history of resistance, approaches such as the one I have adopted in this article allow us to write a history of female resistance.