Introduction

Childhood is a period of rapid emotional and social development for individuals (Bleidorn et al., Reference Bleidorn, Schwaba, Zheng, Hopwood, Sosa, Roberts and Briley2022). Due to the immaturity of psychological functioning, children are prone to problem behaviors (Basten et al., Reference Basten, Tiemeier, Althoff, Van De Schoot, Jaddoe, Hofman, Hudziak, Verhulst and Van Der Ende2016). Among various protective factors for children’s problem behavior, nature contact, relying on its widespread availability and easy access, offers a cost-effective approach to preventing children’s problem behavior (Dzhambov et al., Reference Dzhambov, Lercher, Vincens, Persson Waye, Klatte, Leist, Lachmann, Schreckenberg, Belke, Ristovska, Kanninen, Botteldooren, Van Renterghem, Jeram, Selander, Arat, White, Julvez, Clark and Van Kamp2023; Sakhvidi et al., Reference Sakhvidi, Knobel, Bauwelinck, de Keijzer, Boll, Spano, Ubalde-Lopez, Sanesi, Mehrparvar and Jacquemin2022). Nature contact refers to the experiences of an individual interacting with the natural environment (Frumkin et al., Reference Frumkin, Bratman, Breslow, Cochran, Kahn, Lawler, Levin, Tandon, Varanasi, Wolf and Wood2017). It is increasingly recognized as an essential factor that profoundly influences cognitive, behavioral, and social development (see systematic reviews for Chawla, Reference Chawla2015; Mygind et al., Reference Mygind, Kurtzhals, Nowell, Melby, Stevenson, Nieuwenhuijsen, Lum, Flensborg-Madsen, Bentsen and Enticott2021; Nguyen & Walters, Reference Nguyen and Walters2024), and is considered an important indicator that reflects the natural environment in which children are located (Chawla, Reference Chawla2015; Hartig et al., Reference Hartig, Mitchell, de Vries and Frumkin2014). Thus, the present study will focus on nature contact as a core variable to explore its effect and potential mechanisms in reducing problem behavior among children.

Moreover, a small amount of evidence suggested that problem behavior might restrain children’s nature contact (Musitu-Ferrer et al., Reference Musitu-Ferrer, Esteban-Ibanez, Leon-Moreno and Garcia2019; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Geng and Rodríguez-Casallas2023). However, due to the lack of longitudinal studies, the bidirectional relationship between nature contact and problem behavior remains unclear. Exploring the bidirectional relationship would lead to a more integrated theoretical perspective where child development and nature interaction are mutually reinforcing processes, promoting a more dynamic understanding of child-environment interactions.

There is still a limited understanding of the underlying mechanisms driving the potential bidirectional relationship between nature contact and problem behavior (Dzhambov et al., Reference Dzhambov, Lercher, Vincens, Persson Waye, Klatte, Leist, Lachmann, Schreckenberg, Belke, Ristovska, Kanninen, Botteldooren, Van Renterghem, Jeram, Selander, Arat, White, Julvez, Clark and Van Kamp2023). Children develop in relation to their natural as well as social environments (Barry, Reference Barry2007). However, the social factors influencing these interactions have not been sufficiently considered. The individual-social-ecological systems framework suggests that social factors are a critical linkage between the reciprocal relationship between natural interaction and individual behaviors (Muhar et al., Reference Muhar, Raymond, van den Born, Bauer, Böck, Braito, Buijs, Flint, de Groot, Ives, Mitrofanenko, Plieninger, Tucker and van Riper2018). Prosocial behavior, defined as socially positive actions intended to benefit others (Pfattheicher et al., Reference Pfattheicher, Nielsen and Thielmann2022), is considered a core aspect of social ability and an indicator of children’s social development (Carlo & Padilla-Walker, Reference Carlo and Padilla-Walker2020; Penner et al., Reference Penner, Dovidio, Piliavin and Schroeder2005). Within the framework context, (a) nature contact might promote prosocial behavior, thereby mitigating problem behavior, and (b) problem behavior might hinder the development of prosocial behavior in children, thereby limiting their connection with nature. However, there is a lack of empirical evidence to fully establish this bidirectional model, particularly in terms of how changes in problem behavior can lead to changes in nature contact through prosocial behavior. Furthermore, a cultural lens is critical to understand the complex relationships among nature contact, prosocial behavior, and problem behavior. Firstly, from a theoretical perspective, the Chinese philosophical concept that “unity of heaven and humanity” emphasizes the intrinsic interconnectedness and harmony between humans and nature (Li & Wang, Reference Li and Wang2024), which is consistent with the multi-system interaction emphasized in the individual-social-ecological systems framework. Secondly, given that the Chinese government has increasingly encouraged contact with nature through various policies and initiatives (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Yang, Wang, Li and Ge2024), nature contact may play an especially important role in children’s development in Chinese settings (Duan & Wang, Reference Duan and Wang2022). Thirdly, prosocial behavior is highly valued and seen as an essential means of maintaining social relationships in collectivist culture (e.g., China) (Schroeder & Graziano, Reference Schroeder, Graziano, Schroeder and Graziano2015). In this cultural context, the relationship between nature contact and problem behavior may be especially closer and highlights the important mediating role of prosocial behavior.

In the present study, we aimed to explore the bidirectional relationship between nature contact and children’s problem behavior and the potential mediating role of prosocial behavior from a longitudinal perspective. Theoretically, this study would shed light on how social factors can bridge environmental interaction and individual behavioral outcomes, emphasizing the novel perspective on interaction dynamics among nature interaction, social development, and behavior development. Additionally, by investigating these relationships in relatively less-explored collectivist settings, the findings could offer preliminary insights informing broader discussions about human-environment relationships across diverse cultural backgrounds. Practically, this study would offer actionable insights for policymakers and educators by demonstrating nature-based interventions’ efficacy in reducing problem behavior. This study would also highlight the value of prosocial behavior as a bidirectional leverage, deepening children’s engagement with natural environments and concurrently reducing behavioral problems, thus fostering well-rounded development and improving overall well-being.

Bidirectional relationship between nature contact and children’s problem behavior

Problem behavior refers to maladaptive behavior, including emotional problems, hyperactivity, conduct problems, and peer problems (Achenbach, Reference Achenbach1966). Children’s problem behavior has long-lasting negative effects on individuals’ academic performance (Shi & Ettekal, Reference Shi and Ettekal2021), occupational outcomes (Alaie et al., Reference Alaie, Svedberg, Ropponen and Narusyte2023), and psychological well-being (Hare et al., Reference Hare, Trucco, Hawes, Villar and Zucker2024; Luijten et al., Reference Luijten, Van De Bongardt, Jongerling and Nieboer2021). Epidemiological studies have shown that approximately 20% of children have problem behavior (Cui et al., Reference Cui, Li, Leckman, Guo, Ke, Liu, Zheng and Li2021; Ghandour et al., Reference Ghandour, Sherman, Vladutiu, Ali, Lynch, Bitsko and Blumberg2019), which results in heavy burdens on schools and society (Ogundele, Reference Ogundele2018). With regard to the protective factors for children’s problem behavior, previous studies have predominantly focused on genetic factors (Leve et al., Reference Leve, Anderson, Harold, Neiderhiser, Natsuaki, Shaw, Ganiban and Reiss2022; Yoon et al., Reference Yoon, Maguire-Jack, Ploss, Benavidez and Chang2024) and family and school influences (He et al., Reference He, Tan, Pung, Hu, Tang and Cheng2023; Pinquart & Kauser, Reference Pinquart and Kauser2018). Unlike the high-cost family and school interventions(Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Werner-Seidler, King, Gayed, Harvey and O’Dea2019), the natural environment offers rich experiential sensations that appeal to children (van den Bogerd et al., Reference van den Bogerd, Dijkstra, Koole, Seidell, de Vries and Maas2020) and is widespread availability and easy access, making it a more practical option (García De Jalón et al., Reference García De Jalón, Chiabai, Mc Tague, Artaza, De Ayala, Quiroga, Kruize, Suárez, Bell and Taylor2020). Individuals interacting experiences with the natural environment could be characterized by nature contact (Frumkin et al., Reference Frumkin, Bratman, Breslow, Cochran, Kahn, Lawler, Levin, Tandon, Varanasi, Wolf and Wood2017), which serves as a channel through which people perceive and comprehend their surroundings and the elements within them (Schertz & Berman, Reference Schertz and Berman2019).

Is the effect of nature contact on problem behavior reciprocal? Recent research in ecological psychology underscores the reciprocal dynamic between humans and their environment. It highlights that humans are not merely passive receivers of environmental stimuli, but active participants who both influence and are influenced by their surroundings (Soga & Gaston, Reference Soga and Gaston2022; Wang, Reference Wang2023). Accordingly, nature contact and children’s problem behavior might have bidirectional relationships.

The effect of nature contact on children’s problem behavior

Two classic theories provide frameworks to explain how nature contact alleviates children’s problem behavior through cognitive restoration and stress reduction (Kaplan & Kaplan, Reference Kaplan and Kaplan1989; Ulrich et al., Reference Ulrich, Simons, Losito, Fiorito, Miles and Zelson1991). Specifically, attention restoration theory posits that nature’s fascinating stimuli restore mental focus depleted by the demands of sustained attention in built environments (Kaplan & Kaplan, Reference Kaplan and Kaplan1989). Stress reduction theory proposes that nature’s calming effects activate the parasympathetic nervous system and improve mood, aiding recovery from stress (Ulrich et al., Reference Ulrich, Simons, Losito, Fiorito, Miles and Zelson1991). Accordingly, children benefit from concentration relaxation and emotions stabilizing provided by natural settings, thereby improving attention and reducing stress, which is key aspects of alleviating problem behavior (Achenbach, Reference Achenbach1966; Burkhart et al., Reference Burkhart, Horn Mallers and Bono2017; Gallen et al., Reference Gallen, Schaerlaeken, Younger, Anguera and Gazzaley2023; Russell & Lightman, Reference Russell and Lightman2019; Yao et al., Reference Yao, Zhang and Gong2021). Empirical evidence consistently indicates that nature contact can significantly reduce children’s problem behavior (Liang et al., Reference Liang, Yang, Liu, Pu, Bao, Zhao, Hu, Zhang, Huang, Jiang, Pu, Huang, Dong and Chen2024; Madzia et al., Reference Madzia, Ryan, Yolton, Percy, Newman, LeMasters and Brokamp2019). For example, Madzia et al.’s (Reference Madzia, Ryan, Yolton, Percy, Newman, LeMasters and Brokamp2019) cross-sectional study showed that increased exposure to residential green space was associated with reduced problem behavior in children aged 7 and 12. Liang et al.’s (Reference Liang, Yang, Liu, Pu, Bao, Zhao, Hu, Zhang, Huang, Jiang, Pu, Huang, Dong and Chen2024) cross-sectional study showed that nature contact (green and blue spaces) negatively predicted problem behavior in children and adolescents aged 6–18.

The effect of children’s problem behavior on nature contact

Conversely, evidence indicating that children with more problem behavior face greater barriers to nature contact remains limited but suggestive. Recent studies suggested that individuals with behavior problems may struggle to establish connections with external environments, including natural settings (Chawla, Reference Chawla2020; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Justice, Paul and Mashburn2016; Watson et al., Reference Watson, Harvey, McCabe and Reynolds2020). Moreover, a small number of studies suggested that increased problem behavior might be associated with reduced nature contact in children (Taylor & Kuo, Reference Taylor and Kuo2008). For example, Taylor and Kuo’s (Reference Taylor and Kuo2008) quasi-experimental study of children and adolescents aged 5 to 18 found that hyperactive children are more likely to play indoors or in built outdoor areas, while their non-hyperactive counterparts more frequently engage in green spaces. This contrast highlights that problem behavior may not only influence the type of play environments children select but also restrict their exposure contact with nature.

To sum up, most previous studies have found the unidirectional effect of nature contact on children’s problem behavior, whereas their bidirectional relationship has not been explored. Moreover, school-age children are not only in a sensitive period for forming and preventing problem behavior (Basten et al., Reference Basten, Tiemeier, Althoff, Van De Schoot, Jaddoe, Hofman, Hudziak, Verhulst and Van Der Ende2016) but also in a critical stage for exploring nature because the benefits of nature are more salient in children than in adults or the elderly (Bleidorn et al., Reference Bleidorn, Schwaba, Zheng, Hopwood, Sosa, Roberts and Briley2022; Maes et al., Reference Maes, Pirani, Booth, Shen, Milligan, Jones and Toledano2021). Thus, it is necessary to investigate whether nature contact and children’s problem behavior have a bidirectional relationship.

The mediating role of prosocial behavior in the bidirectional relationship between nature contact and children’s problem behavior

The individual-social-ecological systems framework suggests that (a) ecological interactions (e.g., nature contact) can shape social factors (e.g., prosocial behavior), thereby impacting psychological and behavioral responses (e.g., behavioral problem); (b) conversely, individuals’ psychological and behavioral response (e.g., behavioral problem) influence their social factors (e.g., prosocial behavior), which in turn affect their ecological interactions (e.g., nature contact). Prosocial behavior is considered a direct core aspect of social ability and an indicator of children’s social development (Carlo & Padilla-Walker, Reference Carlo and Padilla-Walker2020; Penner et al., Reference Penner, Dovidio, Piliavin and Schroeder2005). Accordingly, prosocial behavior might not only act as a social mediator in reducing problem behavior through nature contact, but also serve as a social barrier that hinders nature contact by problem behavior.

Nature contact plays an important role in children’s problem behavior through prosocial behavior

Nature contact may enhance children’s prosocial behavior by providing them opportunities to interact positively and build meaningful connections within their social groups (Huang & Lin, Reference Huang and Lin2023). Empirical studies have consistently demonstrated the positive role of nature contact in prosocial behavior in children (Pirchio et al., Reference Pirchio, Passiatore, Panno, Cipparone and Carrus2021; Putra et al., Reference Putra, Astell-Burt, Cliff, Vella and Feng2021). For example, Putra et al. (Reference Putra, Astell-Burt, Cliff, Vella and Feng2021) conducted a longitudinal study to investigate the long-term effects of nature contact on prosocial behavior among children aged 4–5 who were followed over ten years. They found that children whose caregivers perceived the quality of green spaces as good exhibited better prosocial behavior. Pirchio et al. (Reference Pirchio, Passiatore, Panno, Cipparone and Carrus2021) conducted a quasi-experimental study with 9- to 11-year-old children who engaged in nature-based activities for four months. Their findings suggested significant increases in prosocial behavior in the intervention group, underscoring the benefits of nature engagement.

Moreover, it has been suggested that children’s prosocial behavior is negatively associated with problem behavior. Specifically, children with greater prosocial behavior are better at making positive attributions and understanding social and emotional cues, leading to fewer problem behaviors (Dodge & Schwartz, Reference Dodge, Schwartz, Stoff, Breiling and Maser1997). Several studies have shown that prosocial behavior might be a protective factor against problem behavior (Flouri & Sarmadi, Reference Flouri and Sarmadi2016; Memmott-Elison & Toseeb, Reference Memmott-Elison and Toseeb2023). For example, Flouri and Sarmadi (Reference Flouri and Sarmadi2016) conducted a longitudinal study to examine how prosocial behavior affected children’s behavioral problems from ages 3 to 7. They found that children with lower levels of prosocial behavior were more likely to exhibit problem behaviors. Additionally, a longitudinal study by Putra et al. (Reference Putra, Astell-Burt, Cliff, Vella and Feng2022) involving children and adolescents aged 4 to 15 showed that prosocial behavior mediated the relationship between neighborhood green space and children’s problem behavior. However, this study focused on the objective conditions of the neighborhood green space, not the actual engagement with natural environments. Nature contact, reflecting actual interaction with nature (Frumkin et al., Reference Frumkin, Bratman, Breslow, Cochran, Kahn, Lawler, Levin, Tandon, Varanasi, Wolf and Wood2017), has been reported to more accurately predict individual benefits than merely the subjective conditions of the natural environment (Gong & Li, Reference Gong and Li2024). Hence, whether nature contact plays a role in children’s problem behavior through prosocial behavior remains unclear.

Problem behavior plays an important role in children’s nature contact through prosocial behavior

Correspondingly, children’s problem behavior might be associated with nature contact via prosocial behavior. Specifically, children with less problem behavior often have better self-regulation ability, allowing them to regulate their cognition and behavior in various contexts more effectively and actively participate in prosocial activities (Memmott-Elison & Toseeb, Reference Memmott-Elison and Toseeb2023). Several studies have shown that problem behavior negatively predicts children’s prosocial behavior (Memmott-Elison & Toseeb, Reference Memmott-Elison and Toseeb2023; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Ettekal, Liew and Woltering2021). For example, Shi et al. (Reference Shi, Ettekal, Liew and Woltering2021) conducted a 12-year longitudinal study to track the development of prosocial behavior among children from grades 1 to 12. The results revealed different patterns of prosocial behavior, with behavior problems playing significant roles in influencing these developmental paths. Similarly, Memmott-Elison and Toseeb (Reference Memmott-Elison and Toseeb2023) conducted a longitudinal study with children and adolescents aged 3 to 14 and found that problem behavior was associated with reduced subsequent prosocial behavior.

It has been proposed that people with satisfying social relationships may seek to connect with nature, as emotions facilitating connections with others could also extend to a desire to connect with the natural environment (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Fiske and Schubert2019). Studies have suggested that an individual’s prosocial tendencies can promote their nature contact (Duong & Pensini, Reference Duong and Pensini2023; Neaman et al., Reference Neaman, Montero, Pensini, Burnham, Castro, Ermakov and Navarro-Villarroel2023). For example, Neaman et al. (Reference Neaman, Montero, Pensini, Burnham, Castro, Ermakov and Navarro-Villarroel2023) found that prosocial tendencies in children and adolescents aged 11 to 19 promoted their connection to nature. Similarly, Duong and Pensini (Reference Duong and Pensini2023) found that prosocial tendencies were positively associated with their connection to nature in adults. Therefore, children’s problem behavior may negatively affect nature contact by diminishing their prosocial behavior.

In summary, previous studies have provided preliminary evidence for the unidirectional effect of nature contact on problem behavior via prosocial behavior. However, there has been limited exploration of the potential bidirectional mediating role of prosocial behavior between nature contact and problem behavior. Therefore, this study aimed to examine this bidirectional mediating role of prosocial behavior in the relationship between nature contact and problem behavior.

Current study

Although evidence has shown an association between nature contact and problem behavior, most studies focused on the effects of nature contact on children’s behavior unidirectionally. There was lacking studies exploring the effects of children’s behavior on nature contact conversely. Moreover, the precise mechanisms underpinning this relationship remain a key research focus. To date, only one study has provided preliminary evidence of the mediating role of prosocial behavior in this relationship (Putra et al., Reference Putra, Astell-Burt, Cliff, Vella and Feng2022), and there is a lack of empirical evidence on how problem behavior might impact nature contact through prosocial behavior. The mediation analysis using a cross-lagged panel model can effectively reveal the mechanisms mediating the relationships between variables (Cole & Maxwell, Reference Cole and Maxwell2003). Consequently, this study will employ a longitudinal mediation analysis using a cross-lagged model focusing on children aged 8–10. This age is critical for establishing connections with nature (Braun & Dierkes, Reference Braun and Dierkes2017), fostering prosocial behavior (Foulkes et al., Reference Foulkes, Leung, Fuhrmann, Knoll and Blakemore2018), and preventing problem behavior (Christner et al., Reference Christner, Essler, Hazzam and Paulus2021).

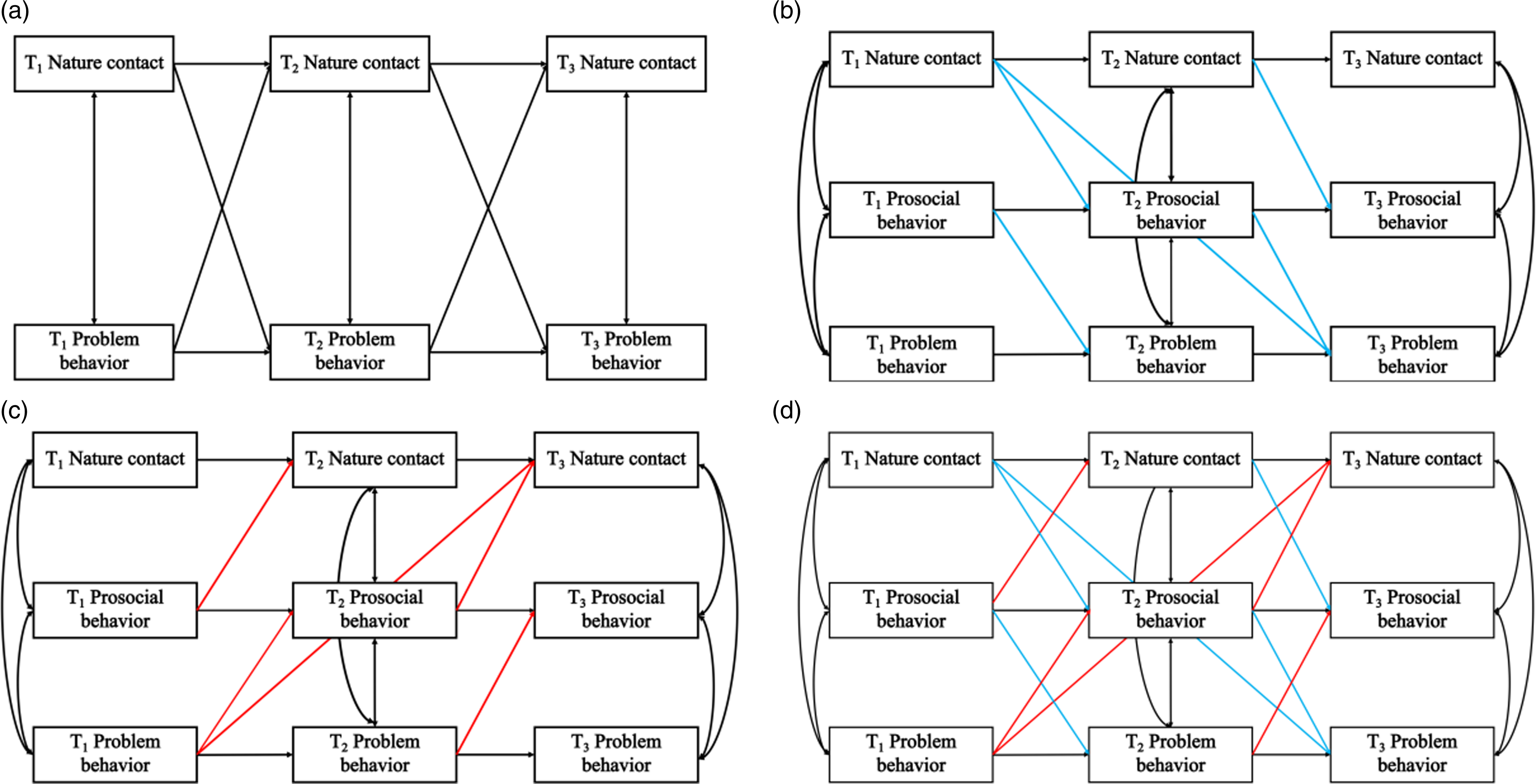

Using a three-wave longitudinal design, the current study aimed to investigate the bidirectional relationship between nature contact and problem behavior and the mediating role of prosocial behavior between them in 8- to 10-year-old children. We hypothesized that (a) nature contact and problem behavior longitudinally and negatively predict each other in children (Figure 1a); (b) prosocial behavior reciprocally mediates the relationship between nature contact and problem behavior in children (Figure 1b–d).

Figure 1. The proposed models for the relationships among nature contact, problem behavior, and prosocial behavior in children. Note. (a) Bidirectional relationship between nature contact and problem behavior. (b) Prosocial behavior mediates nature contact to problem behavior. (c) Prosocial behavior mediates problem behavior to nature contact. (d) Prosocial behavior reciprocally mediates the relationship between nature contact and problem behavior. Abbreviations: T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2; T3 = Time 3.

Method

Participants

Children from grades 3 to 5 across three public primary schools in Shandong Province, China, were recruited for this study. This study had a longitudinal design, and children participated in surveys at three time points across one year, with six-month survey intervals (Time 1, T1: July 2022; Time 2, T2: January 2023; Time 3, T3: July 2023). A total of 602 children (319 girls, M age = 9.90 ± 0.70 years old) agreed to participate and provided fully completed questionnaires at T1. A total of 535 children completed the survey at T2 (281 girls, M age = 10.41 ± 0.69 years old), and 516 children completed the survey at T3 (268 girls, M age = 10.88 ± 0.66 years old). The attrition rates of T2 and T3 were 11.13% and 14.29% respectively. Attrition analyses were performed to compare the children who remained at T3 with those who dropped out. The results showed no significant differences in gender [χ 2(1) = 0.01, p = .98], age at T1 [t = −1.44, p = .15], nature contact at T1 [t = 1.07, p = .29], prosocial behavior at T1 [t = 1.24, p = .22], and problem behavior at T1 [t = −0.06, p = .95]. Only children who completed all three surveys were included in the final analysis. All the children had normal or corrected-to-normal visual and hearing. No child has special educational needs or developmental issues, based on reports from their parents and teachers. This study was approved by the University’s Research Ethics Committee. We obtained approval from the participants’ guardians before the T1 survey (see Supplementary Materials for samples).

Measures

Nature contact

Nature contact was measured using an adapted version of the Nature Contact Index Questionnaire in Chinese (Zou & Yang, Reference Zou and Yang2018), validated for school-age children (Cronbach’s α = .95 in a pilot sample aged 6 to 12). The questionnaire includes 16 items on nature contact covering three aspects, i.e., “natural expectation and emotion” (e.g., “I hope to have more opportunities to interact with various plants and animals”), “nature appreciation and care” (e.g., “I will go to the park to play or admire plants and animals”), and “natural design and arrangement” (e.g., “I will participate in the management activities of organizing and designing my gardens, fields, green spaces, etc.”). Participants’ scores on the scale were calculated by averaging across items. Higher mean scores of items indicate higher nature contact levels among the children. The participants responded on a Likert-like scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). In the present study, the Cronbach’s α for this measure was .96, .94, and .92 for T1, T2, and T3, respectively. The confirmatory factor analysis for T1 to T3 showed that the models fit well [T1: χ 2/df = 4.92, CFI = .92, TLI = .91, SRMR = .05, RMSEA = .07; T2: χ 2/df = 4.35, CFI = .91, TLI = .92, SRMR = .05, RMSEA = .07; T3: χ 2/df = 3.90, CFI = .94, TLI = .93, SRMR = .05, RMSEA = .06], indicating good construct validity.

Prosocial behavior

Prosocial behavior was assessed using a Chinese version of the Prosocial Tendencies Measure (Carlo & Randall, Reference Carlo and Randall2002), demonstrating good reliability and validity in Chinese children (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Yang, Chen, Liu, Deng, Dai, Fan, Li and Cui2023). This scale included 26 items, representing six types of social behavior, which are public (e.g., “When other people are around, it is easier for me to help needy others”), anonymous (e.g., “I prefer to donate money anonymously”), dire (e.g., “It is easy for me to help others when they are in a dire situation”), compliant (e.g., “When people ask me to help them, I do not hesitate”), emotional (e.g., “I tend to help others especially when they are really emotional”), and altruistic prosocial behavior (e.g., “I tend to help others particularly when they are emotionally distressed”). Participants responded to each item using a 5-point scale (1 = does not describe me at all, 5 = describes me greatly). We calculated an average score across items on this scale, with higher scores representing increased levels of prosocial behavior. In the present study, Cronbach’s α for this measure was .97, .97, and .97 for T1, T2, and T3, respectively. The confirmatory factor analysis for T1 to T3 showed that the models fit well [T1: χ 2/df = 2.99, CFI = .94, TLI = .93, SRMR = .03, RMSEA = .06; T2: χ 2/df = 3.05, CFI = .93, TLI = .93, SRMR = .05, RMSEA = .06; T3: χ 2/df = 4.07, CFI = .92, TLI = .91, SRMR = .05, RMSEA = .07], indicating good construct validity.

Problem behavior

Problem behavior was assessed using the self-report Difficulties subscale of the Chinese version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (Du et al., Reference Du, Kou and Coghill2008; Goodman, Reference Goodman2001), which demonstrated acceptable reliability and validity in school-age children (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Chien, Shang, Lin, Liu and Gau2013; Muris et al., Reference Muris, Meesters, Eijkelenboom and Vincken2004). It consists of 20 items in four dimensions, i.e., “emotional symptoms” (e.g., “I have many fears, is easily scared.”), “conduct problems” (e.g., “I often lie or cheat.”), “hyperactivity” (e.g., “I am restless, overactive, cannot sit still for long.”), and “peer problems” (e.g., “I have one or several good friends.”). Children were asked to answer with a 3-point Likert-like scale ranging from 0 (not true) to 2 (certainly true). Scores were averaged across items on this scale, with higher scores corresponding to higher levels of problem behavior. In this study, the Cronbach’s α for this measure was .82, .85, and .83 for T1, T2, and T3, respectively. The confirmatory factor analysis for T1 to T3 showed that the models fit well [T1: χ 2/df = 1.63, CFI = .96, TLI = .95, SRMR = .04, RMSEA = .04; T2: χ 2/df = 2.05, CFI = .94, TLI = .93, SRMR = .06, RMSEA = .05; T3: χ 2/df = 4.12, CFI = .93, TLI = .92, SRMR = .05, RMSEA = .07], indicating good construct validity.

Socioeconomic status (SES)

SES was assessed using parental educational attainment and monthly household income (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhang and Jiang2020). Parental education was coded into six levels: 1 = less than elementary school, 2 = completed elementary school, 3 = completed junior high school, 4 = completed high school or junior college, 5 = completed undergraduate or college education, and 6 = completed master’s degree or higher. These levels were coded to compute the average parental education score. Monthly household income was measured on an 11-point scale, where 1 = ¥0 – ¥3,999, 2 = ¥4,000 – ¥5,999, 3 = ¥6,000 – ¥7,999, 4 = ¥8,000 – ¥9,999, 5 = ¥10,000 – ¥11,999, 6 = ¥12,000 – ¥13,999, 7 = ¥14,000 – ¥15,999, 8 = ¥16,000 – ¥17,999, 9 = ¥18,000 – ¥19,999, 10 = ¥20,000 – ¥39,999, and 11 = more than ¥39,999. The scores of these two measurements were separately standardized and summed as an indicator of SES (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhang and Jiang2020), with a higher score indicating higher SES.

Procedure

At each time point, children were group-tested in quiet classrooms supervised by two psychology graduate or undergraduate students who had received systematic training. At the beginning of each survey, investigators read out a unified instruction, guiding students to complete the questionnaires independently. After the children completed the survey, they were given small gifts for participation. All questionnaires were collected and brought back. Each survey was about 40 minutes long.

Analytic approach

SPSS Version 22.0 was used for missing data analysis and preliminary analysis. For the attrition analyses, potential differences were explored using chi-square and independent t-tests for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. The missing data rates for the main variables at three time points ranged from 1.4% to 8.1%, with omissions primarily due to children failing to answer. The missing values were missing completely at random [Little’s MCAR test: χ 2 = 119.69, df = 103, p = .13] and estimated using full information maximum likelihood. The maximum likelihood estimator with robust standard errors was employed to accommodate any non-normality of the data. The preliminary analyses examined the descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations among all variables. If the correlations between potential covariates (i.e., age, gender, and SES) and variables of interest were significant, the covariates were controlled for in the cross-lagged panel models.

Mplus Version 8.3 was used for model construction and path analyses. Firstly, to examine the bidirectional relationship between nature contact and problem behavior, we constructed four competing cross-lagged models that hypothesize nature contact and problem behavior bidirectional predict each other. Specifically, (a) Model 1 (baseline model) was unconstrained, allowing for free estimation of both cross-lagged and auto-regressive paths; (b) Model 2 was a constrained model that auto-regressive paths were constrained to be equal across time points; (c) Model 3 was a constrained model in which cross-lagged paths were constrained to be equal across time point; (d) Model 4 was a constrained model in which cross-lagged and auto-regressive paths were constrained to be equal across time points. Secondly, to examine the mediating effect of prosocial behavior on the relationship between nature contact and problem behavior, cross-lagged mediation models were constructed (Cole & Maxwell, Reference Cole and Maxwell2003): (a) Model 5 was a “nature contact to problem behavior” mediation model; (b) Model 6 was a “problem behavior to nature contact” mediation model; (c) Model 7 was a reciprocal mediation model. In constructing cross-lagged panel models, we included autoregressive paths for nature contact, prosocial behavior, and problem behavior. After selecting the final cross-lagged mediation model, the bootstrap method (with 5000 samples) was performed to test the significance of the mediation paths.

The model fit indices consist of Chi-squared (χ 2), comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and standardized root means square residual (SRMR). The critical criteria for acceptable model fit were CFI ≥ .90, TLI ≥ .90, SRMR ≤ .08, and RMSEA ≤ .08 (Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999). For model comparison, considering that chi-square values are sensitive to large sample sizes and not considered a decisive criterion (Cheung & Rensvold, Reference Cheung and Rensvold2002), this study used ΔCFI and ΔRMSEA ≤ .01 as criteria for determining invariance (Little, Reference Little2013). If the difference in fit between these models were not significant, then a more parsimonious model would be favored. Non-significant paths were trimmed from the final model. For mediation effect testing, a 95% confidence interval (CI) of the indirect effect did not include 0, indicating a significant mediation effect (Preacher & Hayes, Reference Preacher and Hayes2008). All statistical tests were two-tailed. A p-value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Common method bias was tested using Harman’s one-factor test (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, Mackenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). The exploratory factor analysis included nature contact, prosocial behavior, and problem behavior at three time points. The results showed that the eigenvalues of 31 factors were higher than those without rotation. The first factor accounted for 19.18% of the cumulative variation (below the critical value of 40%), which indicated no significant common method bias in this study.

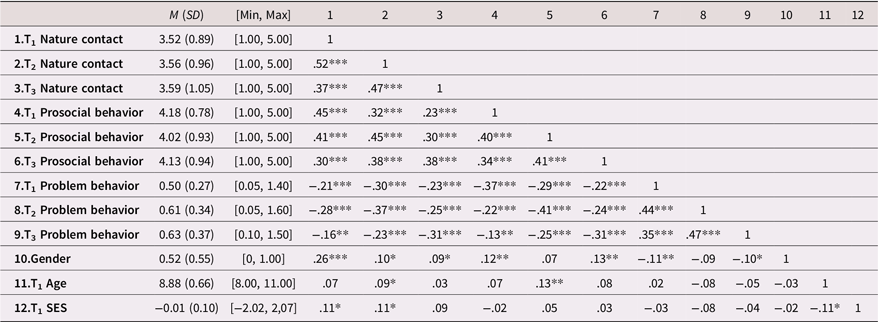

Table 1 shows the variables’ means, standard deviations, minimum and maximum values, and correlations each time. Results indicated a positive correlation between nature contact and prosocial behavior (ranging from .23 to .45), a negative correlation between nature contact and problem behavior (ranging from −.37 to −.16), and a negative correlation between prosocial behavior and problem behavior (ranging from −.41 to −.13). Since gender, age, and SES were correlated with main variables, the three variables were controlled for in the following analyses. The post hoc power analyses were conducted using G*Power (two tails; samples size = 516; r = 0.30, medium effect size; α = .05) and indicated sufficient power [1-β = 99.99%; over the critical value of 80%].

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlations of the variables at different time points (N = 516)

Note. Descriptive statistics were calculated from the average scores of all items across each scale. Gender was dummy coded: 0 = boys, 1 = girls. * indicates p < .05, ** indicates p < .01,*** indicates p < .001. Abbreviations: T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2; T3 = Time 3; SES = socioeconomic status.

Cross-lagged panel models of nature contact and problem behavior

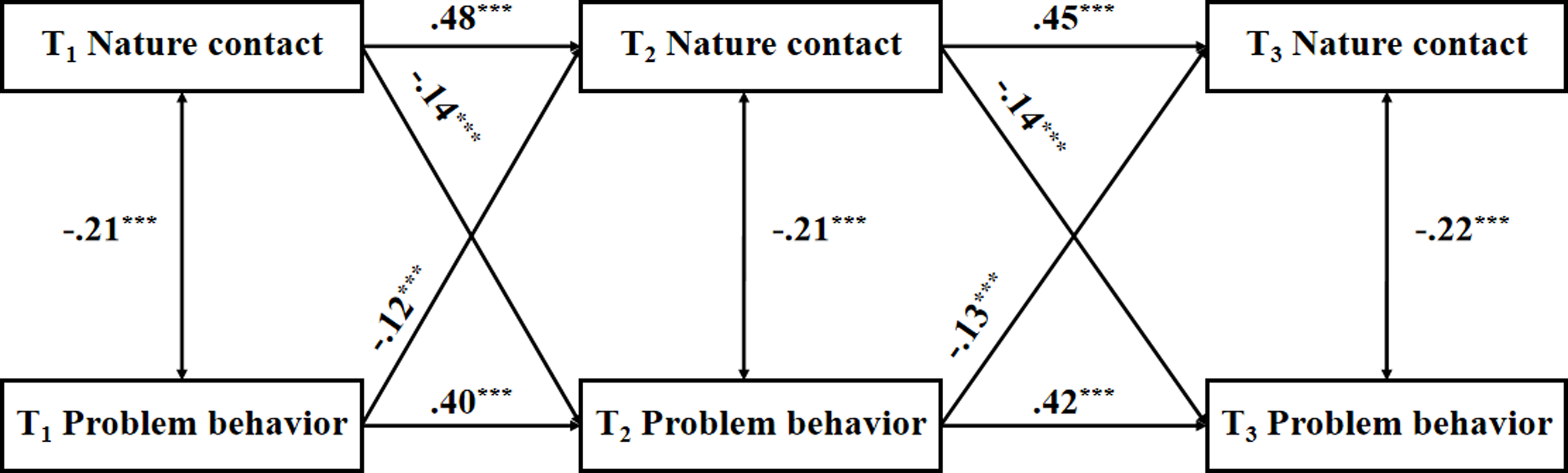

Cross-lagged panel models of nature contact and problem behavior were constructed (Model 1 to Model 4) to examine the bidirectional relationship between nature contact and problem behavior. All models were adjusted for covariates (i.e., age, gender, and SES). All model-fit statistics are presented in Table S1 in Supplementary Materials. The full unconstrained model (Model 1, baseline model) demonstrated good model fit [χ 2 = 24.95, df = 17, CFI = .952, TLI = .941, SRMR = .033, RMSEA = .052]. The model comparison results suggested that Models 2 and 3 did not demonstrate improved fit compared to Model 1. In contrast, Model 4 (the model with constrained auto-regressive and cross-lagged paths) exhibited better model fit than Model 1 [|ΔCFI| = .013 > .01]. Hence, Model 4 was selected as the final model.

Figure 2 and Table S2 in Supplementary Materials show the results of this final model. The results showed that nature contact negatively predicted problem behavior from T1 to T2 [β = −.14, SE = .03, p < .001] and from T2 to T3 [β = −.14, SE = .03, p < .001]; problem behavior negatively predicted nature contact from T1 to T2 [β = −.12, SE = .03, p < .001] and from T2 to T3 [β = −.13, SE = .03, p < .001]. The results indicated that an increase in nature contact predicted a decrease in problem behavior at six months, and a decrease in problem behavior predicted an increase in nature contact at six months. This finding suggested the bidirectional relationship between nature contact and problem behavior.

Figure 2. Cross-lagged panel model for nature contact and problem behavior. Note. (a) The values in the figure are the standardized regression coefficients for the path. (b) For simplicity, covariates (i.e., age, gender, and SES), residuals, and residual correlations were not presented. (c) The solid line indicates the significant paths. The dotted line indicates insignificant paths. (d) *indicates p < .05, **indicates p < .01,***indicates p < .001. Abbreviations: T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2; T3 = Time 3.

Cross-lagged mediation analyses of prosocial behavior

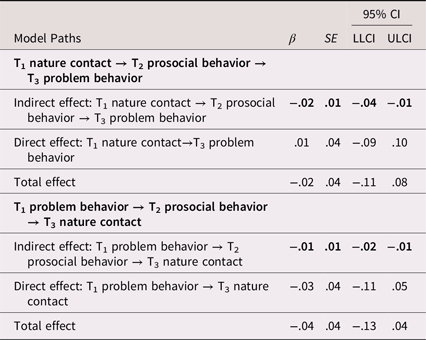

Cross-lagged panel models combined with mediation analyses were constructed to examine the longitudinal mediating role of prosocial behavior between nature contact and problem behavior, with age, gender, and SES included as covariates (Model 5 to Model 7). Model 5 was constructed, which proposed that prosocial behavior unidirectionally mediates the relationship between nature contact and problem behavior. Model 6 was constructed, which proposed that prosocial behavior unidirectionally mediated the relationship between problem behavior and nature contact. Model 7 was constructed, which proposed that prosocial behavior bidirectionally mediated the relationship between nature contact and problem behavior. As shown in Table S3 in Supplementary Materials, Model 6 did not meet the criteria for a satisfactory fitting model [CFI < .90, TLI < .90, SRMR ≥ .08, RMSEA ≥ .08], and Model 5 and Model 7 demonstrated acceptable fitness. Model 7 exhibited better model fit than Model 5 [|ΔCFI| = .016 > .01]. Additionally, Models 5 and 6 might not have adequately captured the complexity of the theoretical bidirectional relationship proposed. Thus, Model 7 was selected as the final model of associations among nature contact, prosocial behavior, and problem behavior.

Table 2 and Figure 3 show that the results of cross-lagged mediation model (model 7). Table S4 shows the standardized parameter estimation for the cross-lagged mediation panel model. The results demonstrated a significant indirect effect of T1 nature contact on T3 problem behavior through T2 prosocial behavior [β = −.02, SE = .01, 95% CI = [−.04, −.01]]. The direct effect of T1 nature contact on T3 problem behavior was not significant [β = .01, SE = .04, 95% CI = [−.09, .10]]. Results revealed that prosocial behavior at T2 mediated the relationship between nature contact at T1 and problem behavior at T3. This finding suggested that an increase in nature contact predicted an increase in prosocial behavior at six months, and an increase in prosocial behavior predicted a decrease in problem behavior at six months.

Figure 3. The longitudinal mediating role of prosocial behavior on the relationship between nature contact and problem behavior. Note. (a) Model 5: nature contact to problem behavior model. (b) Model 6: problem behavior to nature contact model. (c) Model 7: reciprocal model. The values in the figure are the standardized regression coefficients for the path. For simplicity, covariates (i.e., age, gender, and SES), residuals, and residual correlations were not presented. The solid line indicates the significant paths. The dotted line indicates insignificant paths. * indicates p < .05, ** indicates p < .01, *** indicates p < .001. Abbreviations: T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2; T3 = Time 3.

Table 2. Direct and indirect effects in the cross-lagged mediation model

Note. Significant paths (p < .05) are indicated in bold. The β represents the standardized regression coefficients. Abbreviations: LLCI = lower limit of confidential interval; ULCI = upper limit of confidential interval; T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2; T3 = Time 3; SE = standardized error.

Conversely, the results demonstrated a significant indirect effect of T1 problem behavior on T3 nature contact through T2 prosocial behavior [β = −.01, SE = .01, 95%CI = [−.02, −.01]]. The direct effect of problem behavior at T1 on nature contact at T3 was not significant [β = −.03, SE = .04, 95%CI = [−.11, .05]]. The finding indicated that prosocial behavior at T2 mediated the relationship between problem behavior at T1 and nature contact at T3. This finding suggested that an increase in problem behavior predicted a decrease in prosocial behavior at six months, and a decrease in prosocial behavior predicted a decrease in nature contact at six months. T2 prosocial behavior accounted for 19.1% of the relationship between T1 problem behavior and T3 nature contact. The findings indicated that prosocial behavior might play a bidirectional mediating effect between nature contact and problem behavior.

Discussion

Several studies have suggested that nature contact benefits children (Dzhambov et al., Reference Dzhambov, Lercher, Vincens, Persson Waye, Klatte, Leist, Lachmann, Schreckenberg, Belke, Ristovska, Kanninen, Botteldooren, Van Renterghem, Jeram, Selander, Arat, White, Julvez, Clark and Van Kamp2023; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Huo, Wang, Bai, Zhao and Di2023), including being protective of children’s behavior problems (Liang et al., Reference Liang, Yang, Liu, Pu, Bao, Zhao, Hu, Zhang, Huang, Jiang, Pu, Huang, Dong and Chen2024; Madzia et al., Reference Madzia, Ryan, Yolton, Percy, Newman, LeMasters and Brokamp2019). However, most studies in this area have focused on the effects of nature contact on children’s behavior development unidirectionally, but recent evidence suggested that children’s behavior also has effects conversely (Musitu-Ferrer et al., Reference Musitu-Ferrer, Esteban-Ibanez, Leon-Moreno and Garcia2019; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Geng and Rodríguez-Casallas2023), though whether this extends into school-age children and the underpinning mechanism has rarely been explored. This study used a three-wave longitudinal design to examine the bidirectional relationship between nature contact and children’s problem behavior, as well as the bidirectional mediating role of prosocial behavior between them. The results indicated that nature contact and problem behavior have a longitudinal and bidirectional relationship, which is bidirectionally mediated by children’s prosocial behavior.

Bidirectional relationship between nature contact and children’s problem behavior

This study shows that nature contact is a protective factor for children’s problem behavior, which was in line with previous studies (Liang et al., Reference Liang, Yang, Liu, Pu, Bao, Zhao, Hu, Zhang, Huang, Jiang, Pu, Huang, Dong and Chen2024; Madzia et al., Reference Madzia, Ryan, Yolton, Percy, Newman, LeMasters and Brokamp2019). Nature provides rich opportunities and experiences that contribute to children’s holistic development in physical, cognitive, emotional, and social aspects (Dopko et al., Reference Dopko, Capaldi and Zelenski2019), leading to a reduction in problem behavior. For example, engagement in natural environments has been linked to reduced levels of stress (Mygind et al., Reference Mygind, Kjeldsted, Hartmeyer, Mygind, Stevenson, Quintana and Bentsen2019), helping children regulate their emotions and behaviors more effectively (Bakir-Demir et al., Reference Bakir-Demir, Berument and Akkaya2021; Mueller & Flouri, Reference Mueller and Flouri2020). In another way, our study suggested that children’s problem behavior hinders their contact with nature, aligning with and extending previous research, highlighting the effect of problem behavior on nature contact. Firstly, while existing research has suggested specific problem behaviors (e.g., inattention/hyperactivity) might impede nature contact (Taylor & Kuo, Reference Taylor and Kuo2008), our findings reveal that behavioral behaviors at a broader level may systematically restrict children’s nature contact. Children exhibiting higher levels of problem behaviors may struggle to engage in activities due to challenges in attentional regulation and peer acceptance (Han et al., Reference Han, Way, Yoshikawa and Clarke2023; Taylor & Kuo, Reference Taylor and Kuo2008), limiting their opportunities for meaningful interactions with natural environments. Secondly, empirical research suggested that curiosity and positive peer interactions support individuals’ contact with nature (Łaszkiewicz et al., Reference Łaszkiewicz, Kronenberg, Mohamed, Roitsch and De Vreese2023; Om et al., Reference Om, Brereton, Dema, Ploderer, Buchanan, Davis, Al Mahmud, Sarsenbayeva, Soro, Munoz, Potter, Taylor and Tsimeris2021). However, children with more problem behaviors show less interest and affiliation with the world around them (Han et al., Reference Han, Way, Yoshikawa and Clarke2023; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Justice, Paul and Mashburn2016; Watson et al., Reference Watson, Harvey, McCabe and Reynolds2020) and might experience more social exclusion and hinder cooperative play in natural settings (Krull et al., Reference Krull, Wilbert and Hennemann2018), limiting their opportunities for nature contact. Collectively, the bidirectional relationship between nature contact and problem behavior highlights the importance of viewing children as active participants in their interactions with nature, rather than merely passive recipients, and further supports the emerging perspective that human-nature interactions are reciprocal (Soga & Gaston, Reference Soga and Gaston2022; Wang, Reference Wang2023).

Bidirectional mediating role of prosocial behavior in the relationship between nature contact and children’s problem behavior

This study found that nature contact reduced children’s problem behavior via fostering prosocial behavior. Previous research (Putra et al., Reference Putra, Astell-Burt, Cliff, Vella and Feng2022) showed the positive effect of objective conditions of nature contact (i.e., green space quality) on children’s problem behavior through prosocial behavior. Our study expanded this understanding by examining how children’s subjective perceptions and feelings about their interactions with nature shape these behavioral outcomes. The natural environment, with its open and diverse spaces, provided objective contexts for children to engage in various sensory experiences and interaction opportunities (Goldy & Piff, Reference Goldy and Piff2020). These objective aspects of nature (e.g., flora and fauna) create an enriched setting where children can explore and interact (Norwood et al., Reference Norwood, Lakhani, Fullagar, Maujean, Downes, Byrne, Stewart, Barber and Kendall2019). Simultaneously, these environments subjectively influence children’s perceptions and feelings, enhancing their emotional and psychological engagement with the space. Such rich and immersive experiences allow children to create feelings of connectedness and relatedness to the natural world (Bratman et al., Reference Bratman, Olvera-Alvarez and Gross2021), promote children’s social interaction and prosocial behavior, and reduce problem behavior (Hukkelberg et al., Reference Hukkelberg, Keles, Ogden and Hammerstrøm2019; de La Osa et al., Reference de la Osa, Navarro, Penelo, Valentí, Ezpeleta and Dadvand2024). The dual impact of nature, through both its objective physical properties and subjective experiential qualities, allows children to not only be physically exposed but also emotionally and cognitively connect with the environment, fostering comprehensive social and behavioral development.

This study found the longitudinal mediating role of prosocial behavior between problem behavior and nature contact. Children’s problem behavior can lead to negative social interactions with others, which may result in social rejection and exclusion (Chávez et al., Reference Chávez, Salmivalli, Garandeau, Berger and Kanacri2022; Obsuth et al., Reference Obsuth, Eisner, Malti and Ribeaud2015), further diminishing opportunities for practicing and reinforcing prosocial behavior (Khoury-Kassabri et al., Reference Khoury-Kassabri, Zadok, Eseed and Vazsonyi2020; Kong & Lu, Reference Kong and Lu2023). Additionally, children with problem behavior may struggle to regulate their emotions and respond appropriately to others (Thomsen & Lessing, Reference Thomsen and Lessing2020), leading to impulsive or aggressive reactions instead of prosocial behavior (Ren et al., Reference Ren, Ren, Yan, Lu and Zhou2022). The long-term absence of prosocial behavior might lead to a lack of feeling of connection with others (Fiske, Reference Fiske, Mates, Mikesell and Smith2010). The lack of connection with others would consequently lead to a decreased sense of affiliation and connection with nature (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Fiske and Schubert2019). Our findings not only provided empirical support but also deepened the understanding of the individual-social-ecological systems framework by demonstrating that prosocial behavior serves as a critical mediator between nature contact and problem behavior. This mediation elucidates key social mechanisms, highlighting how environmental factors are linked to individual behavioral outcomes (Hartig et al., Reference Hartig, Schutte, Torquati and Stevens2021). Moreover, our findings support the integrated nature of these interactions, reinforcing the framework’s conceptualization of individual, social, and ecological systems as a synergistic and interconnected network (Hartig et al., Reference Hartig, Mitchell, de Vries and Frumkin2014). Notably, this study did not directly investigate the mechanism within the frameworks of attention restoration theory and stress reduction theory (Kaplan & Kaplan, Reference Kaplan and Kaplan1989; Ulrich et al., Reference Ulrich, Simons, Losito, Fiorito, Miles and Zelson1991), both of which might also explain how nature contact alleviates children’s problem behaviors. Future research could explore additional mediators embedded within these theoretical frameworks to elucidate their mechanisms further.

Implications

The present findings have implications for educational practice. Firstly, the findings not only suggest the cascades between nature contact, prosocial behavior, and problem behavior, but also highlight the importance of holistic approaches that consider both environmental and psychological interventions. For one thing, this supported nature education as a cost-effective way to promote children’s behavior development. For another thing, this suggested that educators might implement structured nature activities that are specifically designed to be inclusive and engaging for children who exhibit higher levels of problem behavior, thereby ensuring that these children are not inadvertently excluded from the benefits of nature contact. Secondly, since children’s prosocial behavior is intertwined with their nature contact and problem behavior, interventions that target prosocial behavior could be more effective for reducing problem behavior and enhancing nature contact simultaneously. Educators could foster children’s prosocial behavior by creating opportunities or conducting school-based interventions (Shin & Lee, Reference Shin and Lee2021). Specifically, parents could organize activities where children can engage in helping others, such as community service projects or cooperative games that require teamwork and sharing (Setiawati & Handrianto, Reference Setiawati and Handrianto2023). Additionally, schools could provide structured programs, which were designed to help students better understand and manage their emotions, and enhance cooperation and support among peers (Crompton et al., Reference Crompton, Kaklamanou, Fasulo and Somogyi2024). Thirdly, in the context of collective culture and ecological civilization, understanding the effects of nature contact on children in China can provide empirical support for policies promoting nature contact as a component of public health and education strategies. It highlights the potential for environmental policy to play a role in mitigating problem behaviors and enhancing prosocial behaviors among children.

Limitations

Although this study reveals the bidirectional effects and mechanism of nature contact and problem behavior and finds a potentially low-cost and efficient way to alleviate children’s problem behavior, this study has some limitations. Firstly, this study used a self-report method of nature contact. Future research could combine subjective perceptions (e.g., self-report) and objective measures (e.g., Geographical Information System technique) of nature contact to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationships among nature contact, prosocial behavior, and problem behavior. Secondly, because this study was based on a sample from a province of China, the generalizability of the results might be limited. Further research could be conducted using large-scale surveys and recruiting children from different regions. Thirdly, our analysis did not include measures of parental attitudes and guidance towards nature, which could significantly influence a child’s opportunities for and engagement with natural environments. Future studies should consider assessments of parental attitudes and guidance to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the environment and family contributing to nature contact among children.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to explore the bidirectional relationship between nature contact and problem behavior in children, which might be explained by prosocial behavior. It provided insights into the human-society-nature relationship and highlighted a potential pathway to promote the comprehensive development of children.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457942500032X.

Data availability statement

Data collected during the study is openly available at OSF (https://osf.io/v6hpm/?view_only=10d90aaacf72445ea00fd239f8653efe).

Author contributions

Haoning Liu: Writing – Original draft, Formal analysis. Jingyi Zhang: Writing – review & editing. Yue Qi: Writing – review & editing. Xiao Yu: Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. Xinyi Yang: Software.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 72404027].

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.