Introduction

Personality pathology arises from the interplay between temperamental vulnerabilities and adverse social environments such as repeated negative interactions with others (De Fruyt & De Clercq, Reference De Fruyt and De Clercq2014; Fonagy et al., Reference Fonagy, Target, Gergely, Allen and Bateman2003; Fruzzetti et al., Reference Fruzzetti, Shenk and Hoffman2005; Linehan, Reference Linehan1993). This susceptibility is pronounced during early adolescence (Kaurin et al., Reference Kaurin, Do, Ladouceur, Silk and Wright2023a; Winsper et al., Reference Winsper, Lereya, Marwaha, Thompson, Eyden and Singh2016). Despite conceptual work on caregiver interactions in personality pathology development (Fonagy et al., Reference Fonagy, Target, Gergely, Allen and Bateman2003; Linehan, Reference Linehan1993), there is limited empirical research on longitudinal changes in youth personality pathology through behavioral observation of caregiver–adolescent interactions (Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Egeland and Sroufe2009; Whalen et al., Reference Whalen, Scott, Jakubowski, McMakin, Hipwell, Silk and Stepp2014). Instead, much of our understanding relies on studies characterizing maladaptive interaction patterns via (retrospective) self-reports that assess parenting or interaction patterns concurrently with trait vulnerabilities (Steele et al., Reference Steele, Townsend and Grenyer2019), with most studies focusing on young children (Lunkenheimer et al., Reference Lunkenheimer, Skoranski, Lobo and Wendt2021; Lyons-Ruth et al., Reference Lyons-Ruth, Bureau, Holmes, Easterbrooks and Brooks2013) and borderline personality disorder (BPD) specifically (Fleck et al., Reference Fleck, Fuchs, Moehler, Williams, Koenig, Resch and Kaess2023; Mahan et al., Reference Mahan, Kors, Simmons and Macfie2018; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Fleck, Fuchs, Koenig and Kaess2023).

Establishing these connections between interpersonal behavior and developmental personality pathology is one key, albeit difficult, goal of studying personality pathology, both because (social) behaviors are important and because they provide a validity criterion independent of possible biases in self- and informant reports (Kaurin et al., Reference Kaurin, Egloff, Stringaris and Wessa2016). This study aims to bridge this gap by examining whether observed caregiver–adolescent interaction patterns predict changes in girls’ maladaptive traits in early to mid-adolescence beyond baseline self- and caregiver-reports of the same.

Personality pathology can be conceptualized as a disruption in the socio-affective and socio-cognitive processes related to self and interpersonal regulation and understanding, manifesting in relationships (Hopwood et al., Reference Hopwood, Wright, Ansell and Pincus2013). Although personality pathology is most often diagnosed in early adulthood, it typically begins in adolescence (Solmi et al., Reference Solmi, Radua, Olivola, Croce, Soardo, Salazar De Pablo, Il Shin, Kirkbride, Jones, Kim, Kim, Carvalho, Seeman, Correll and Fusar-Poli2022). During puberty, biological and social processes undergo substantial changes, increasing sensitivity to positive and negative socio-emotional cues, leading to a heightened desire for peer affiliation and sensitivity to social evaluation (Crone & Dahl, Reference Crone and Dahl2012; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Somerville, Li, Ruberry, Powers, Mehta, Dyke and Casey2014). During that time, adjustment challenges (Kaurin, et al., Reference Kaurin, Sequeira, Ladouceur, McKone, Rosen, Jones, Wright and Silk2022), including developmental personality pathology (Kaurin et al., Reference Kaurin, Do, Ladouceur, Silk and Wright2023a), are susceptible to environmental influences (Sisk & Gee, Reference Sisk and Gee2022).

Sensitivity to socioemotional cues may be particularly heightened in girls (Crosnoe & Johnson, Reference Crosnoe and Johnson2011; Kaurin et al., Reference Kaurin, Do, Ladouceur, Silk and Wright2023a; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Leibenluft, McCLURE and Pine2005), who tend to exhibit a stronger relational orientation and greater affiliative needs during adolescence compared to boys (Vanwoerden et al., Reference Vanwoerden, Franssens, Sharp and De Clercq2022). Starting in early adolescence, girls report more interpersonal stressors, which they also perceive as more burdensome (Hankin et al., Reference Hankin, Mermelstein and Roesch2007; Kaurin et al., Reference Kaurin, Do, Ladouceur, Silk and Wright2023a; Rudolph, Reference Rudolph2002). Youth interpersonal and affective experiences are closely linked and mutually reinforcing over time (Griffith, et al., Reference Griffith, Young and Hankin2021a). Adolescent girls experience greater affective intensity and instability (Bailen et al., Reference Bailen, Green and Thompson2019) and normative declines in positive affect, along with increases in negative affect have been observed at an earlier age in girls compared to boys, likely due to pubertal timing (Griffith et al., Reference Griffith, Clark, Haraden, Young and Hankin2021b). Together, these factors highlight early adolescent girls’ vulnerability to changing social-contextual dynamics typical of this developmental period (Rose & Rudolph, Reference Rose and Rudolph2006).

The caregiver–child relationship is thought to be key for the development of self- and interpersonal capacities, relevant to personality pathology (Fruzzetti et al., Reference Fruzzetti, Shenk and Hoffman2005). These capacities increase over the course of adolescence, when youth transition toward greater autonomy (Sharp et al., Reference Sharp, Vanwoerden and Wall2018). Maintaining a supportive caregiver–child relationship to help youth master this developmental milestone is important for youth adjustment (Sisk& Gee, Reference Sisk and Gee2022; Skabeikyte-Norkiene et al., Reference Skabeikyte-Norkiene, Sharp, Kulesz and Barkauskiene2022). Recent evidence suggests that this may be particularly relevant during the transitional phase of early adolescence (Franssens et al., Reference Franssens, Abrahams, Brenning, Van Leeuwen and De Clercq2021). Supportive caregiver–adolescent relationships have been found to buffer against adverse effects from childhood (Colich et al., Reference Colich, Sheridan, Humphreys, Wade, Tibu, Nelson, Zeanah, Fox and McLaughlin2021) as well as concurrent social stressors such as bullying (Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Monti, Modi, Sze and Troop-Gordon2020).

While caregiving has been studied as a broad risk and protective factor for psychopathology, recent studies have differentially linked harsh and punishing parenting styles to adolescent BPD as compared to depression (Beeney et al., Reference Beeney, Forbes, Hipwell, Nance, Mattia, Lawless, Banihashemi and Stepp2021; Franssens et al., Reference Franssens, Abrahams, Brenning, Van Leeuwen and De Clercq2021). Preliminary evidence suggests, that while caregivers typically adapt their parenting practices during adolescence to be less coercive and to augment warmth, this normative increase in cohesion does not occur in families with children high in BPD traits (Stepp et al., Reference Stepp, Whalen, Scott, Zalewski, Loeber and Hipwell2014). Importantly, parental affective behaviors both contribute to the development of personality pathology and respond to trait vulnerabilities in children (Stepp et al., Reference Stepp, Whalen, Scott, Zalewski, Loeber and Hipwell2014). Youth with higher levels of maladaptive traits may be more challenging for parents, and these difficulties could manifest in lower dyadic interactional quality (Boucher et al., Reference Boucher, Pugliese, Allard-Chapais, Lecours, Ahoundova, Chouinard and Gaham2017). Offspring characteristics may influence caregiver interaction patterns, contributing to increased negative (Milan & Carlone, Reference Milan and Carlone2018) and decreased positive (Dietz et al., Reference Dietz, Birmaher, Williamson, Silk, Dahl, Axelson, Ehmann and Ryan2008; Milan & Carlone, Reference Milan and Carlone2018) communication patterns with caregivers. Similarly, children’s over-reactivity, impulsivity, and aggressiveness have been found to increase parental stress and contribute to inadequate parenting practices (Yan et al., Reference Yan, Ansari and Peng2021). Studying parent-child interactions at a dyadic level is, therefore, essential for understanding how maladaptive traits are mitigated or exacerbated over time. Reduced dyadic cohesion and reciprocity along with heightened negative affect displays have been associated with BPD traits and self-harm in adolescents (Crowell et al., Reference Crowell, Baucom, McCauley, Potapova, Fitelson, Barth, Smith and Beauchaine2013; Fleck et al., Reference Fleck, Fuchs, Moehler, Williams, Koenig, Resch and Kaess2023; Kaufman et al., Reference Kaufman, Puzia, Godfrey and Crowell2020a; Lyons-Ruth et al., Reference Lyons-Ruth, Brumariu, Bureau, Hennighausen and Holmes2015; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Fleck, Fuchs, Koenig and Kaess2023). Conversely, positive maternal and dyadic affective behaviors at age 16 have been linked to declines in girls’ BPD trait severity scores over time (Whalen et al., Reference Whalen, Scott, Jakubowski, McMakin, Hipwell, Silk and Stepp2014). This suggests that the mother–daughter context is an important protective factor in shaping the course of BPD during adolescence

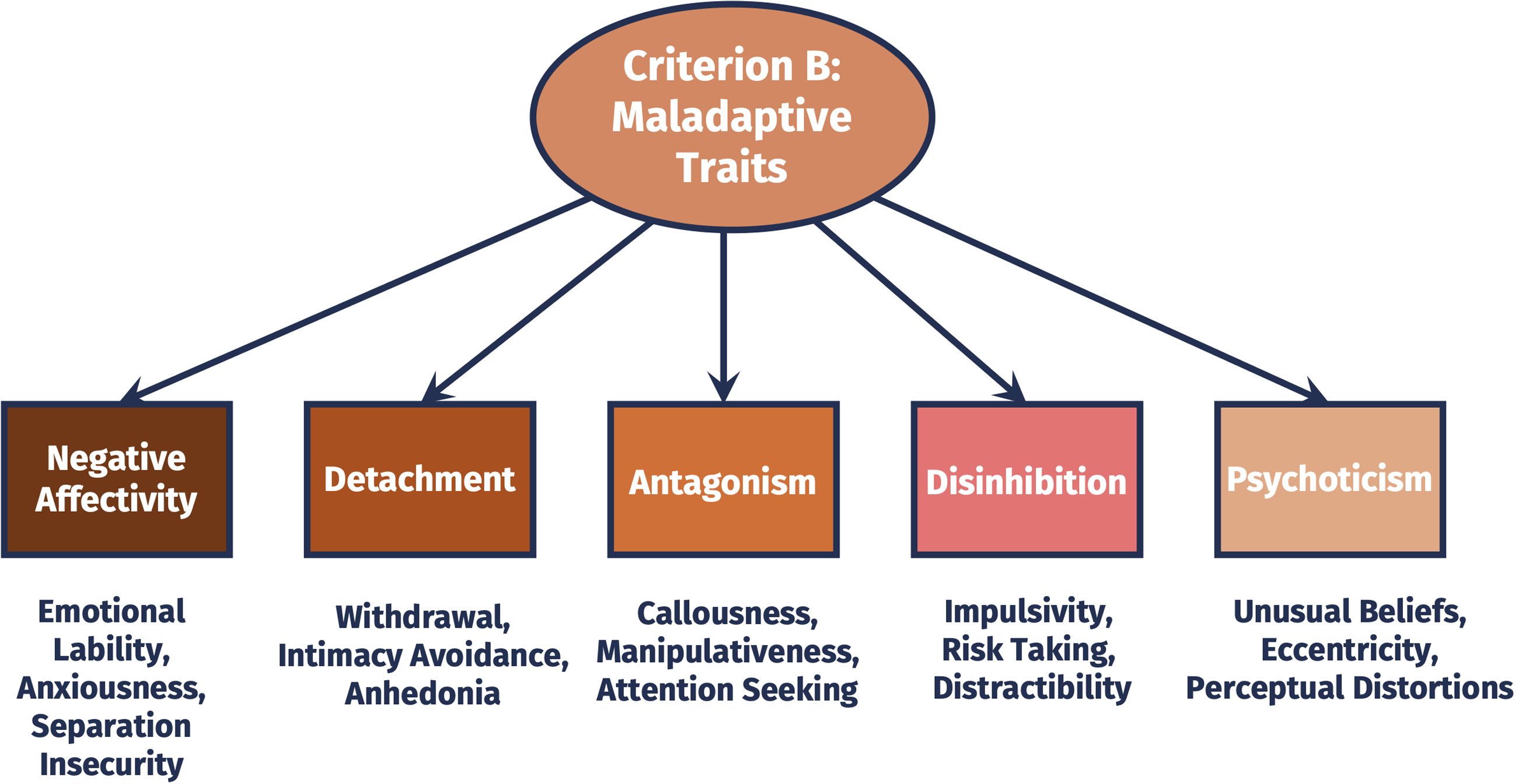

Previous related research has strongly focused on the emergence of BPD pathology in adolescents. Major classification systems, however, have shifted toward a dimensional assessment of personality pathology, differentiating personality disorder severity and maladaptive traits (American Psychiatric Association (APA), 2013; World Health Organization (WHO), 2019). According to the Alternative Model of Personality Disorders (AMPD; APA, 2013) in DSM-5 Section III, personality pathology is evaluated based on the level of impairment in self- and interpersonal functioning common to all personality disorders (personality functioning, Criterion A), and a dimensional trait perspective capturing more specific areas of dysfunction (Criterion B) which are considered useful for case formulation (Bach et al., Reference Bach, Markon, Simonsen and Krueger2015; Hopwood, Reference Hopwood2018). Criterion B is organized around individual differences in how impairments are expressed (e.g., a disposition to get irritated easily or difficulties with establishing and following a plan). It includes five higher order dimensions, namely negative affectivity, detachment, antagonism, disinhibition, and psychoticism (See Figure 1 for a schematic depiction). These align with the five-factor model of personality (Costa & McCrae, Reference Costa and McCrae1992) typically labeled as neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness and openness, but emphasize maladaptive extremes of these traits (Krueger et al., Reference Krueger, Derringer, Markon, Watson and Skodol2012; Krueger & Markon, Reference Krueger and Markon2014). The five domains identified by Criterion B are common to other dimensional models of psychopathology (Kotov et al., Reference Kotov, Krueger, Watson, Achenbach, Althoff, Bagby, Brown, Carpenter, Caspi, Clark, Eaton, Forbes, Forbush, Goldberg, Hasin, Hyman, Ivanova, Lynam, Markon and Zimmerman2017). Children’s dimensional trait dispositions can be identified early in life (Shiner, Reference Shiner, John and Robins2021). Therefore, the nuanced exploration of maladaptive traits linked to self- and interpersonal dysregulation allows adopting a developmentally sensitive perspective on early personality disturbances and personality pathology continuity (Kaurin et al., Reference Kaurin, Do, Ladouceur, Silk and Wright2023a; Sharp, Reference Sharp2020). Linking dysfunctional interpersonal processes with maladaptive traits, the AMPD enables the integration of decades of developmental temperament and trait research (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Roberts and Shiner2005; Costa et al., Reference Costa, McCrae and Löckenhoff2018; McAdams & Olson, Reference McAdams and Olson2010) into contemporary studies on personality pathology in youth (Sharp et al., Reference Sharp, Vanwoerden and Wall2018; Sharp, Reference Sharp2020).

Figure 1. Schematic depiction of Criterion B of the alternative model of personality disorders maladaptive trait domains and facets captured by the personality inventory for DSM-5 (PID-5).

From a developmental psychopathology perspective, vulnerability in relationships is highlighted during developmental transitions, when experiences in relationships play a crucial role in achieving developmental goals (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Insabella, Porter, Smith, Land and Phillips2006; Allen & Loeb, Reference Allen and Loeb2015). To date, there is little research on youth social functioning (e.g., via caregiver interactions) in the context of the AMPD. Some evidence suggests that maladaptive traits in youth are significant predictors of self- and interpersonal dysfunction, both concurrently in daily life (Kaurin et al., Reference Kaurin, Do, Ladouceur, Silk and Wright2023a) as well as longitudinally up to emerging adulthood (Vanwoerden et al., Reference Vanwoerden, Franssens, Sharp and De Clercq2022). While maladaptive traits have been found to show small normative declines during adolescence (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Cohen, Kasen, Skodol, Hamagami and Brook2000; Laceulle et al., Reference Laceulle, Rienks, Meijer, De Moor and Karreman2023; de Clercq et al., Reference De Clercq, Van Leeuwen, Van Den Noortgate, De Bolle and De Fruyt2009, Reference De Clercq, Hofmans, Vergauwe, De Fruyt and Sharp2017) they persist or increase in a subset of individuals (Laceulle, Reference Laceulle, Rienks, Meijer, De Moor and Karreman2023, De Clercq et al., Reference De Clercq, Van Leeuwen, Van Den Noortgate, De Bolle and De Fruyt2009). Given their prospective impact on psychosocial functioning, it is important to identify social-contextual dynamics contributing to change in maladaptive traits over time.

The present study

Drawing on conceptual (De Fruyt & De Clercq, Reference De Fruyt and De Clercq2014; Fruzzetti et al., Reference Fruzzetti, Shenk and Hoffman2005) and empirical (Whalen et al., Reference Whalen, Scott, Jakubowski, McMakin, Hipwell, Silk and Stepp2014) evidence, this study investigates whether and which parent–adolescent interaction patterns predict the exacerbation or mitigation of adolescent maladaptive traits over time, according to Criterion B of the AMPD. We focused on early adolescence due to the emotional and interpersonal instability characteristic of this stage, making it a critical risk period for the onset of personality pathology (Griffith, et al., Reference Griffith, Clark, Haraden, Young and Hankin2021b). We narrowed our focus to early adolescent girls. Research suggests that girls, or youth socialized as girls, tend to exhibit a stronger relational orientation and greater affiliative needs during adolescence compared to boys (Vanwoerden et al., Reference Vanwoerden, Franssens, Sharp and De Clercq2022). This likely results in more frequent instances of interpersonal stress among girls (Kaurin et al., Reference Kaurin, Do, Ladouceur, Silk and Wright2023a).

We hypothesize that (1) maladaptive behaviors (e.g., negative escalation) at baseline will predict increases in maladaptive traits (negative affect, detachment, antagonism, disinhibition, and psychoticism) two years later, controlling for baseline levels of each trait. Conversely, we hypothesize that (2) positive dyadic behaviors—characterized by positive escalation, mutuality, relationship quality, and satisfaction—will predict decreases in maladaptive traits (negative affect, detachment, antagonism, disinhibition, and psychoticism) two years later, also controlling for baseline levels of each trait.

Because self- and caregiver ratings of adolescent maladaptive traits are typically only moderately related and differently linked with life-outcomes (Tromp & Koot, Reference Tromp and Koot2010), we incorporated self- and caregiver ratings of adolescent girls’ maladaptive traits. We exploratively examined the predictive value of dyadic interaction patterns on the unique and shared variances of self- and caregiver ratings, respectively.

Method

Transparency and openness

Data are not publicly available because open access was not included in the informed consent, and sharing could compromise participant privacy. The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. Exemplary code for our statistical analyses is available at (https://osf.io/t279c/). Our study represents a post-hoc data analysis of a larger study and therefore lacks a priori power calculation.

Participants

N = 129 girls ranging in age from 11-13 (M age = 12.27, SD age = .80)—of which 65% were white, 20% black/African American, 2% Asian, 1% Native American, 9% biracial, and 1% other—and their primary caregiver (M age = 42.62, SD age = 6.87) were recruited to take part in the study. Most girls (89.9%) were accompanied by their biological mother, 8.5% by their biological father and two girls by either their stepmom or their grandmother. 72.2% of the caregivers reported to be married, living with their spouse. 66.7% of the girls were living with both their biological parents, 4.7% in joint custody, 11.6% with their biological mother and her partner, 15.5% with their biological mother only, and 1.6% with adoptive or grandparents. Median total family income in this sample was between $80,000 and $90,000. Baseline observer rated dyadic interactions were available for n = 122 dyads. At baseline n = 127 girls and n = 126 caregivers completed assessments of personality pathology. This was true for n = 111 girls and n = 111 caregivers at two-year follow-up.

Procedure

The current data were derived from a larger longitudinal study examining neural and socio-affective influences on the development of symptoms of depression and anxiety among early adolescent girls. The study took place in a midsized Midwestern city in the U.S. A total of 129 adolescent girls aged between 11 and 13, along with their primary caregivers, were recruited via community and online announcements. Girls exhibiting shy or fearful temperament, as indicated by caregiver or participant report on the Fear and Shyness subscales of the Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire–Revised (EATQ-R; Ellis & Rothbart, Reference Ellis and Rothbart2001), were intentionally oversampled to increase representation of those at heightened risk for developing internalizing disorders. Consequently, two-thirds of the sample were classified as “high-risk,” while one-third were considered “typical-risk” based on shy and fearful temperament.

During the baseline assessment and at a two-year follow-up, adolescent and caregiver ratings of adolescent maladaptive personality traits were collected. Additionally, at baseline, adolescents and caregivers separately generated an issues list (Heatherington et al., Reference Heatherington, Henderson, Reiss, Anderson, Bridges, Chan, Insabella, Jodl, Kim, Mitchell, O’Connor, Skaggs and Taylor1999) to identify a mutually endorsed topic of disagreement from the preceding months (e.g., mutual behavior, keeping the room tidy, lying). Next, they completed a series of dyadic interaction tasks with their parents, including a conflictual discussion. The topic of the conflict discussion was determined by a mutually endorsed topic of disagreement from the above-described issues list. Dyads were instructed to talk about their disagreement for five minutes, attempting to devise a resolution. If they finished before time, they were asked to discuss another topic of disagreement.

Measures

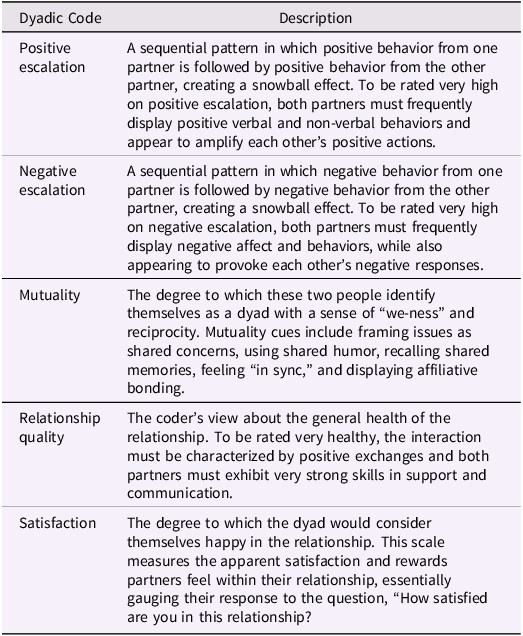

The Interactional Dimensions Coding System (IDCS; Julien et al., Reference Julien, Markman and van Widenfelt1986), adapted for use with adolescents (Furman & Shomaker, Reference Furman and Shomaker2008), was employed to analyze caregiver–child interactions during a conflict discussion. Five dyadic codes were used to assess various aspects of the interactions during the discussion. Table 1 provides brief descriptions and sample indicators of the interaction patterns coded as positive escalation, negative escalation, mutuality, relationship quality, and satisfaction. Study personnel (n = 5) were trained to code videotaped interactions. Training included each rater coding 10 videos from a prior study for which the IDCS system was used. Raters completed training after all 10 videos cumulatively met acceptable levels of reliability (i.e., α ≤ .70) with a previously established “gold standard” rater from the research group. For the present study, trained personnel rated the codes on a scale from one to five, with higher ratings indicating more pronounced expressions of the respective behaviors. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) were calculated to determine inter-rater reliability (positive escalation = .92, negative escalation = .88, mutuality = .83, relationship quality .91, satisfaction = .90, and average = .86)

Table 1. Descriptions of the dyadic interaction behavior codes rated according to the Interactional Dimensions Coding System (IDCS; Julien et al., Reference Julien, Markman and van Widenfelt1986)

The Personality Inventory for DSM-5—Brief Form. We used adolescent and caregiver responses to the Personality Inventory for DSM-5 Brief Form (PID-5-BF), a personality trait assessment scale designed for individuals aged 11–17 years. Previous studies replicated the five factor structure of the PID-5-BF in adolescent samples (De Clercq et al., Reference De Clercq, De Fruyt, De Bolle, Van Hiel, Markon and Krueger2014; Fossati et al., Reference Fossati, Somma, Borroni, Markon and Krueger2017). The PID-5-BF evaluates five distinct personality trait domains, namely negative affect, detachment, antagonism, disinhibition, and psychoticism. Each trait domain comprises five items (see Kaurin et al., Reference Kaurin, Do, Ladouceur, Silk and Wright2023a for a comprehensive list of items). Respondents were asked to assess the extent to which a statement accurately describes them or their child on a scale ranging from 0 (“Very False/Often False”) to 3 (“Very True/Often True”). A mean score was computed across all trait domains. As reported in Kaurin et al. (Reference Kaurin, Do, Ladouceur, Silk and Wright2023a) baseline caregiver- and adolescent-reports were significantly correlated, with coefficients ranging from r = .20 to r = .38.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using R Version 4.3.1 and Mplus Version 8.7. Sample characteristics are reported as means and standard deviations. Bivariate Pearson correlations were used to examine similarities between caregiver and adolescent reports at baseline and follow-up as well as similarities within the same rater over time. Differences between caregiver and adolescent-reports at baseline and follow-up, as well as changes in reports within the same rater over time, were examined using paired t-test to account for the dependencies in the data.

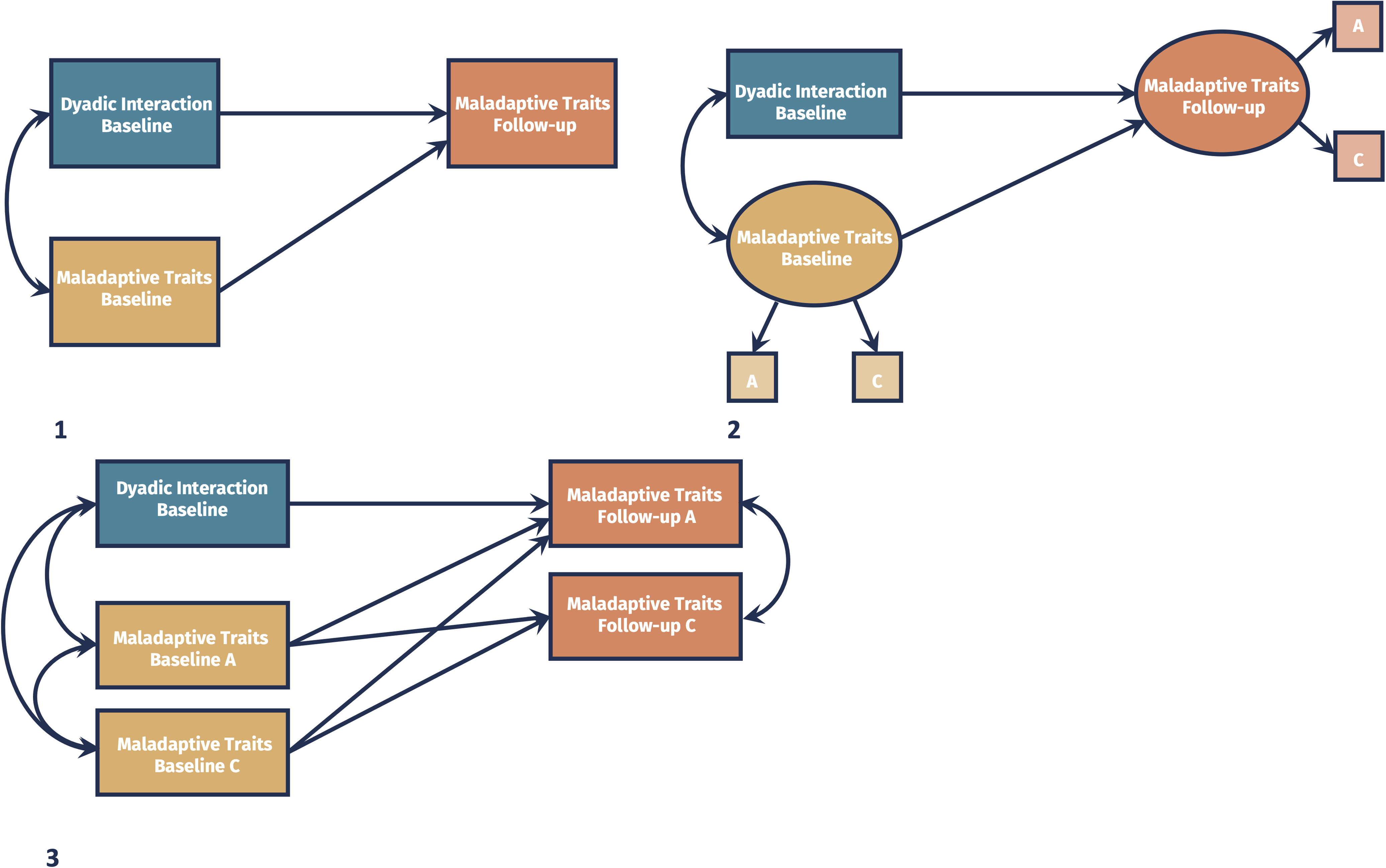

To evaluate how adolescent–caregiver interactions predict changes in adolescent maladaptive traits, we performed a series of path models. All analyses are based on the averaged sum scores of the PID-5 domains and global score. Figure 2 outlines the models: each dyadic code predicts the different maladaptive trait domains and global score from the PID-5, assessed at a two-year follow-up for girls and parent reports, while controlling for baseline values of the same domain (or global score) (Figure 2.1). To differentially assess the contribution of shared and unique variances between self- and caregiver reports, we combined parent and adolescent reports of one domain into one single factor and regressed it onto dyadic codes (Figure 2.2). For unique variances (Figure 2.3), we regressed a maladaptive trait domain on dyadic codes while controlling for the other-rater assessment of the same trait domain. Given that all positive dyadic interaction codes (positive escalation, mutuality, relationship quality, and relationship satisfaction) were strongly correlated, we included a sensitivity analysis repeating all steps based on a single score indicating global positive interaction. The analysis was carried out with global positive interaction modeled as a factor.

Figure 2. Schematic depiction of our analyses based on self- and caregiver reports of adolescent maladaptive traits (1), the shared (2) and unique (3) variance of both reporters predicted by dyadic interaction codes. Single headed arrows represent regression paths. Double headed arrows represent correlations. A = adolescent, C = caregiver, IDCS = Interactional Dimensions Coding System.

We used Bayesian estimation in Mplus, leveraging all available data under the assumption that missing data were missing at random. Significance for all model parameters was based on 95% credibility Intervals (CIs), with CIs that excluded zero indicative of a parameter that differed significantly from zero. We carried out a confirmatory factor analysis using the R-package lavaan (Rosseel, Reference Rosseel2012) to examine whether the positive IDCS codes could be amalgamated as a factor. An acceptable model fit was assumed if the following criteria were satisfied: nonsignificant chi-square value (X 2), comparative fit index (CFI)/ Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) ≥ .95, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤ .05, and, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) ≤ .08 (Schermelleh-Engel et al., Reference Schermelleh-Engel, Moosbrugger and Müller2003; West et al., Reference West, Wu, McNeish, Savord and Hoyle2023).

Results

Preliminary results

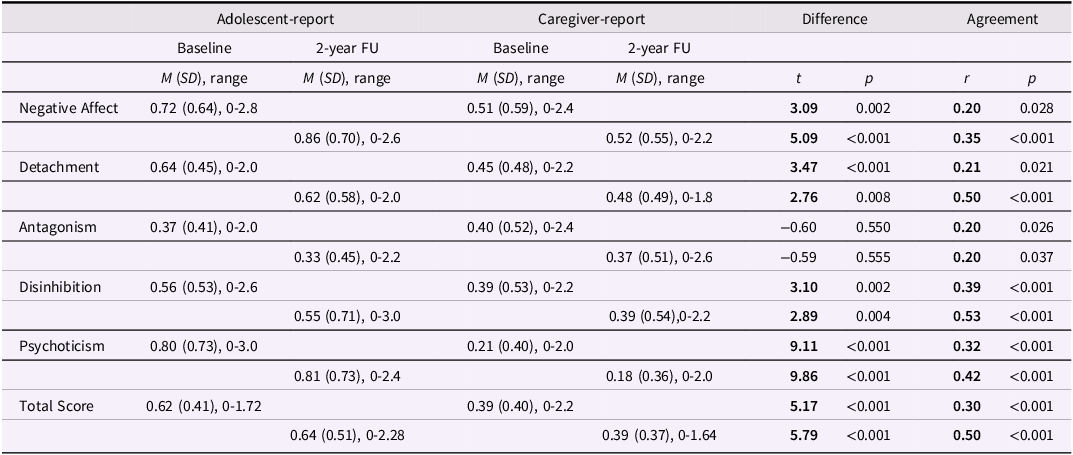

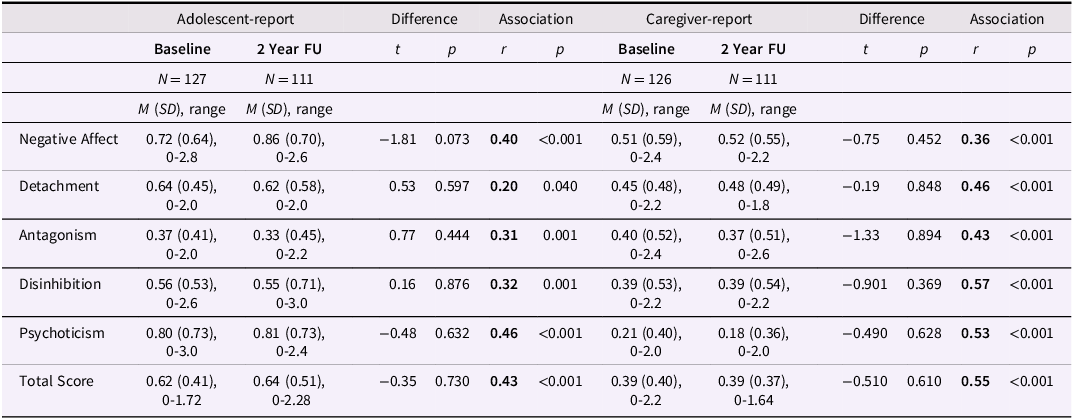

Table 2 summarizes adolescent and caregiver reports of trait vulnerabilities at baseline and follow-up. Across all domains and time points, we found small to moderate positive associations between adolescent and caregiver reports. Overall, associations between self- and parent-reports were higher at the two-year follow-up, compared to baseline assessments. There were also statistically significant differences between adolescent and caregiver reports, with adolescents generally reporting higher maladaptive trait levels, except for antagonism. Paired t-tests showed no significant differences in trait vulnerabilities over time for either self- or caregiver reports, while within-rater associations were moderate (Table 3).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of self- and parent rated adolescent maladaptive traits at baseline and 2-year follow-up

Note. FU = Follow-up; at baseline N = 124 dyads containing adolescent- and caregiver-reports, thus df = 123 for paired samples t-tests. At follow-up N = 110 dyads containing adolescent and caregiver reports, thus df = 109 for paired samples t-tests. Pearson correlations have been calculated for agreement between adolescent and caregiver report at baseline and follow-up, respectively.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics comparing self- respectively parent rated adolescent maladaptive traits over time

Note. FU = Follow-up; Baseline and Follow-up data available for N = 109 adolescents, thus df = 108 for paired samples t-tests. Baseline and Follow-up data available for N = 109 caregiver, thus df = 108 for paired samples t-tests.

Basic descriptive statistics and bivariate Pearson correlations among the IDCS dyadic codes are reported in the supplement (Supplement, Table S1). We found moderate to strong associations (min: −0.34; max: 0.83) among codes. Positive escalation, mutuality, overall relationship quality and satisfaction were positively correlated while negative escalation was negatively correlated with all other codes. Links between dyadic interaction patterns and youth personality pathology at follow-up that were not controlled for baseline, can be found in the supplement (Table S2, Table S3).

The relationship between dyadic interaction patterns and trait vulnerabilities

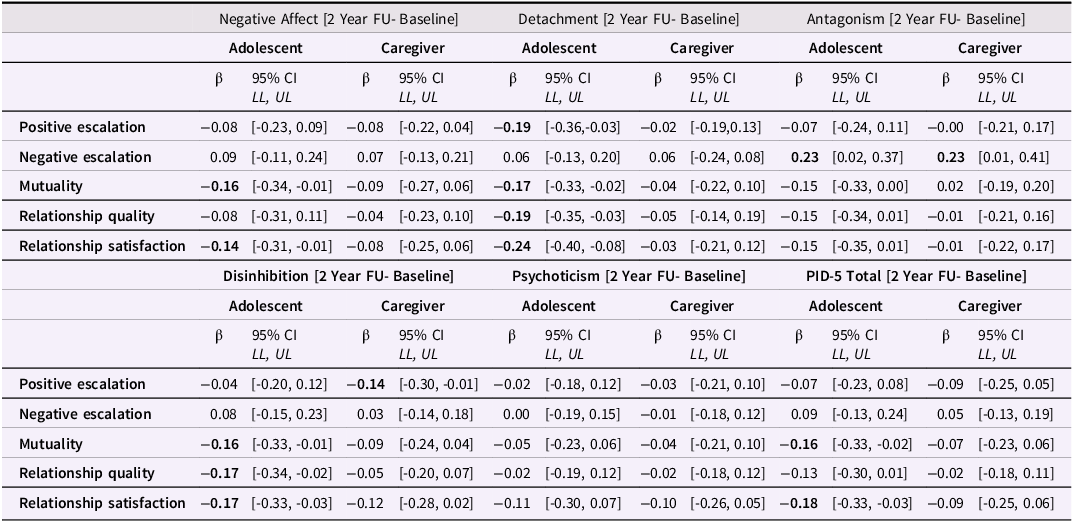

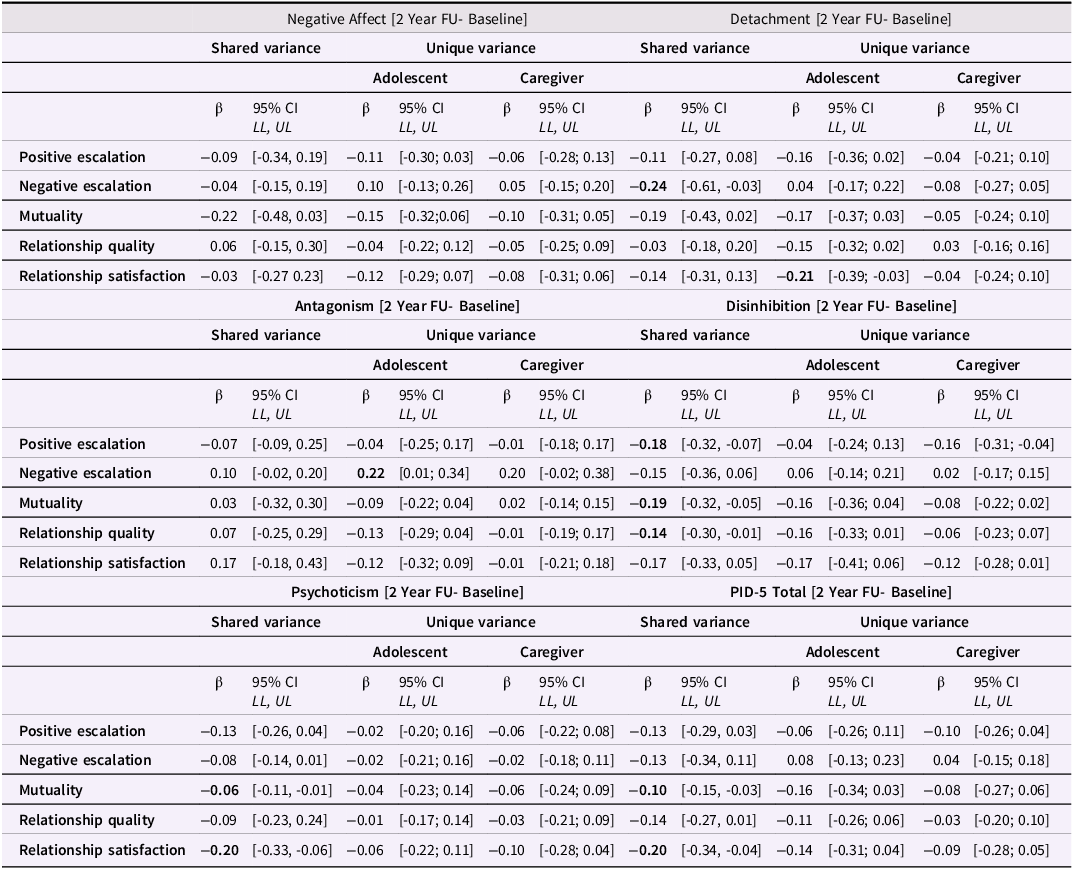

Results are summarized in Tables 4-5, organized by maladaptive trait domains. Table 4 reports dyadic interaction behavior predicting changes in adolescent maladaptive traits, separately for self- and caregiver ratings. Table 5 shows the prediction of the shared and unique variances among self- and caregiver ratings from dyadic interaction behavior.

Table 4. Key standardized coefficients from regression models predicting change in self- and parent rated adolescent maladaptive traits from dyadic behaviors during a conflict task

Note. FU = Follow-up; N = 125-129; Values in bold are those for which the credibility interval (CI, 95%) did not contain zero.

Table 5. Key standardized coefficients from regression models predicting change in the shared and unique variance of self- and caregiver rated adolescent maladaptive traits from dyadic behaviors during a conflict task

Note. FU = Follow-up; N = 125-129; Values in bold are those for which the credibility interval (CI, 95%) did not contain zero.

Adolescent self-report. Less mutuality (ß = −0.16; 95% CI [-0.34, -0.01]) and relationship satisfaction (ß = -0.14; 95% CI [-0.31, -0.01]) predicted higher self-rated negative affect beyond baseline levels of this maladaptive trait. Higher self-rated detachment was predicted by reduced positive escalation (ß = -0.19; 95% CI [-0.36, -0.03]), mutuality (ß = -0.16; 95% CI [-0.33, -0.02]), relationship quality (ß = -0.19; 95% CI [-0.35, -0.03]), and relationship satisfaction (ß = -0.24; 95% CI [-0.40, -0.08]). Lower mutuality (ß = -0.16; 95% CI [-0.33, -0.01]), relationship quality (ß= -0.17; 95% CI [-0.34, -0.02]), and relationship satisfaction (ß = -0.17; 95% CI [-0.33, -0.03]), predicted higher self-rated disinhibition two years later, while higher total PID-5 levels were predicted by reduced mutuality (ß = -0.16; 95% CI [-0.33, -0.02]), and relationship satisfaction (ß = -0.18; 95% CI [-0.33, -0.03]). The only trait domain predicted by negative escalation (ß = 0.23; 95% CI [0.02, 0.37]) was antagonism, with more negative escalation displayed during the conflict task predicting higher antagonism two years later. Self-rated psychoticism was not statistically significantly predicted by any of the dyadic interaction codes.

Caregiver report. We found stronger dyadic negative escalation (ß = 0.23; 95% CI [0.01, 0.41]) during the conflict task to predict caregiver rated antagonism two years later. Moreover, reduced positive escalation (ß = 0.14; 95% CI [-0.30, -0.01]) predicted disinhibition.

Shared and unique variance in adolescent and caregiver reports. The shared variance in self- and caregiver ratings of adolescent increased detachment was linked to lower negative escalation (ß = -0.24; 95% CI [-0.61, -0.03]) during the conflict tasks. The unique variance in increased adolescents’ detachment self-ratings was predicted by lower relationship satisfaction (ß = -0.21; 95% CI [-0.39, -0.03]). The shared variance in increased disinhibition was predicted by lower positive escalation (ß = -0.18; 95% CI [-0.332, -0.07]), mutuality (ß = -0.19; 95% CI [-0.32, -0.05]), and relationship quality (ß = -0.14; 95% CI [-0.30, -0.01]). Finally, lower mutuality (ß= -0.06; 95% CI [-0.11, -0.01]) and relationship satisfaction predicted the shared variance in increases in psychoticism. Similarly, mutuality (ß = -0.10; 95% CI [-0.15, -0.03]) and relationship satisfaction (ß = -0.20; 95% CI [-0.34, -0.04]) were negatively linked to the shared variance in augmented total PID-5 ratings.

Sensitivity analysis

Based on CFA the one-factor solution for showed acceptable to good fit (X2 (df = 2) = 3.03, p = 0.219, CFI = .99; TLI = .99, RMSEA = .07; SRMR = .02) with all standardized factor loadings ≥ |.77|. The internal consistency of this positive interaction dimension was high α = .91. Results of the path analyses predicting adolescents’ self- and caregiver rated maladaptive traits (Table S4) and their shared and unique variances (Table S5), controlled for baseline ratings of maladaptive traits, are reported in the supplement. The positive interaction dimension modeled as a factor predicted increases in adolescent-rated detachment (ß = -0.24; 95% CI [-0.41, -0.06]) only. This was confirmed when separating the unique and shared variance in the caregiver and adolescent ratings. Positive interaction solely predicted unique variance in adolescent rated increases of detachment (ß = -0.20; 95% CI [-0.40, -0.05]).

Discussion

This study is the first to use a comprehensive behavioral assessment to explore developmental personality pathology within the AMPD framework, focusing on interactions between early adolescent girls and their caregivers. We found that adaptive interactions, particularly mutuality and relationship satisfaction, negatively predicted increases in maladaptive traits such as negative affectivity, detachment, disinhibition, and psychoticism over two years. The results were more consistent in girls’ self-reports than in caregiver reports. When statistically accounting for the overlap in variance between self- and caregiver ratings, dyadic interaction patterns only sparsely predicted unique variance in the girls’ self-ratings. The finding is likely due to moderate associations between self- and caregiver ratings. Overall, the found significant associations between dyadic interaction and changes in girls’ maladaptive traits were small. This, however, is to be expected given the relative mean level stability in maladaptive traits and the strength of associations between dyadic interaction and prospective BPD symptoms reported in previous research (Whalen et al., Reference Whalen, Scott, Jakubowski, McMakin, Hipwell, Silk and Stepp2014).

The impact of dyadic interaction on trait changes

To date, only one other longitudinal study has assessed observed dyadic interaction behavior and the development of personality pathology during adolescence, finding that negative escalation significantly predicted higher BPD traits while positive interactions led to better adjustment (Whalen et al., Reference Whalen, Scott, Jakubowski, McMakin, Hipwell, Silk and Stepp2014). We found negative escalation primarily linked to self- and caregiver rated antagonism, while other trait domains (negative affect, detachment, disinhibition, psychoticism) were predicted by reduced positive interaction patterns, primarily relationship satisfaction and mutuality. This finding may be influenced by a lower base-rate and reduced variability in negative escalation in our study. Yet, it also highlights that high levels of maladaptive dyadic behavior do not necessarily equal low levels of adaptive behavior, both entailing different risk-signatures. Given that many studies in youth focus on BPD traits, future research should use dimensional assessments to determine if negative behaviors are primarily linked to antagonistic features in BPD-related behaviors (Fleck et al., Reference Fleck, Fuchs, Moehler, Williams, Koenig, Resch and Kaess2023).

Moreover, finding reduced positive interaction behavior prospectively predicting maladaptive traits is important because knowledge on harsh and other forms of explicitly invalidating parenting (Hallquist et al., Reference Hallquist, Hipwell and Stepp2015; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Keng, Yeo and Hong2022; Stepp et al., Reference Stepp, Whalen, Scott, Zalewski, Loeber and Hipwell2014) and negative dyadic behavior (Crowell et al., Reference Crowell, Baucom, McCauley, Potapova, Fitelson, Barth, Smith and Beauchaine2013; Lyons-Ruth et al., Reference Lyons-Ruth, Brumariu, Bureau, Hennighausen and Holmes2015) has been studied intensively. In contrast, our results and Whalen et al.’s (Reference Whalen, Scott, Jakubowski, McMakin, Hipwell, Silk and Stepp2014) findings highlight positive dyadic interactions as key predictors of changes in girls’ self-rated adjustment. This is in line with—and extends—previous cross-sectional studies that found lower dyadic reciprocity and less dyadic warmth in clinical compared to non-clinical samples (Fleck et al., Reference Fleck, Fuchs, Moehler, Williams, Koenig, Resch and Kaess2023; Kaufman et al., Reference Kaufman, Puzia, Godfrey and Crowell2020a). A recent study based on informant reports has shown that in particular, high maternal emotional support exerts protective effects over time (Franssens et al., Reference Franssens, Abrahams, Brenning, Van Leeuwen and De Clercq2021). Together, these findings on developmental personality pathology and related behavior align with broader research highlighting positive adolescent-caregiver experiences as a key protective environmental factor for youth mental well-being (Sisk & Gee, Reference Sisk and Gee2022).

Despite their moderate to high correlations, in our main analysis, we examined caregiver–adolescent interactions using individual dyadic codes from the IDCS-Scoring manual rather than a global factor. This approach offers more detailed insights into the specific dyadic behavior patterns that may influence adolescents’ adjustment, which we consider crucial for informing clinical practice. In our sensitivity analysis, the factor score of the positive dyadic codes demonstrated worse predictive performance in terms of predictive validity. This finding may suggest that the codes outlined in the IDCS-Scoring manual are differentially linked (and thus differentially clinically informative) to developmental outcomes. It must be noted that conducting our analysis at the raw item level overlooks measurement error and increases the likelihood that our results may reflect differential reliability. As we cannot rule out this possibility, the results must be interpreted carefully and warrant replication. We are unable to directly compare this result with existing literature on personality pathology or general psychopathology in youth, as previous research did not include all dyadic codes from the IDCS (McMakin et al., Reference McMakin, Burkhouse, Olino, Siegle, Dahl and Silk2011; Whalen et al., Reference Whalen, Scott, Jakubowski, McMakin, Hipwell, Silk and Stepp2014). However, various aspects of positive dyadic behaviors and parenting strategies have been shown to have differential links to BPD symptoms, particularly emphasizing the role of emotional sensitivity, support, and warmth (Fleck et al., Reference Fleck, Fuchs, Moehler, Williams, Koenig, Resch and Kaess2023; Franssens et al., Reference Franssens, Abrahams, Brenning, Van Leeuwen and De Clercq2021; Kaufman et al., Reference Kaufman, Puzia, Godfrey and Crowell2020a). High levels of dyadic sensitivity and emotional warmth may be reflected in the affiliative bonding and relational satisfaction captured by the mutuality and satisfaction codes of the IDCS, which most reliably predict changes in maladaptive traits in our study

It may indicate that a lack of “we-ness” (i.e., valuing each other’s perspective, cooperation, and maintaining warmth despite disagreements) poses developmental risks. This ability for mutual recognition and tolerance parallels the interpersonal component of AMPD Criterion A, which is focused on empathy and intimacy. Besides the capacity for deriving pleasure from interpersonal relationships, it comprises the ability to grasp other individuals’ feelings and motives while also being able to experience and tolerate differences (APA, 2013). These social cognitive skills, which can be referred to as mentalizing, develop gradually from childhood into and throughout adolescence (Crone & Dahl, Reference Crone and Dahl2012; Desatnik et al., Reference Desatnik, Bird, Shmueli, Venger and Fonagy2023). The maturation of these skills is crucial for building self-regulatory and interpersonal skills necessary for adult roles. Therefore, significant disruptions in this process can signal the onset of personality disorders during this period (Sharp et al., Reference Sharp, Vanwoerden and Wall2018).

Early adolescence thus may be a time when experiencing mutuality and satisfying, effective communication fosters youth social learning. This in turn may enhance youths’ sense of being accepted and competent social partners and supports positive trait development (Whalen et al., Reference Whalen, Scott, Jakubowski, McMakin, Hipwell, Silk and Stepp2014). Previous research further indicates that positive caregiver–child interactions in early adolescence predict later empathy (Kobak et al., Reference Kobak, Zajac, Abbott, Zisk and Bounoua2017). Future studies should focus on assessing self- and interpersonal functioning in relation to maladaptive trait development within the AMPD framework.

Importantly, our study used a conflict paradigm to assess dyadic interactions. A key indicator of personality pathology is persistence across different situations. To sample more diverse interpersonal patterns, future research should explore the predictive validity of interpersonal behaviors in varied contexts. Williams et al. (Reference Williams, Fleck, Fuchs, Koenig and Kaess2023) noted that adolescent-caregiver interactions differ between fun-day planning and conflict situations: while healthy dyads improved under stress, those with youth high in BPD traits showed decreases in fluency. At-risk youth often depend more on parental emotion co-regulation than self-regulation (Naor-Ziv et al., Reference Naor-Ziv, Shamay-Tsoory and Levy-Gigi2023). Reduced dyadic cooperation under stress may signal ineffective emotional co-regulation, perpetuating developmental risks (Lougheed, Reference Lougheed2020).

We chose to investigate caregiver–child interactions at the dyadic level rather than differentiating between caregiver vs. child-driven effects, focusing on family communication as a risk or protective factor. While several studies have highlighted the responsiveness of caregiving and parental functioning to girls’ BPD-traits (Kaufman et al.; Reference Kaufman, Victor, Hipwell and Stepp2020b; Stepp et al., Reference Stepp, Whalen, Scott, Zalewski, Loeber and Hipwell2014), recent evidence highlights the role of caregiver effects on early adolescents’ BPD-trait trajectories (Franssens et al., Reference Franssens, Abrahams, Brenning, Van Leeuwen and De Clercq2021). Studies on observed dyadic interactions—including caregiver, adolescent, as well as dyadic assessment—have more consistently found an impact of maternal and dyadic behavior on adolescents’ outcomes (Crowell et al., Reference Crowell, Baucom, McCauley, Potapova, Fitelson, Barth, Smith and Beauchaine2013; Fleck et al., Reference Fleck, Fuchs, Moehler, Williams, Koenig, Resch and Kaess2023; Kaufman et al., Reference Kaufman, Puzia, Godfrey and Crowell2020a, Williams et al., Reference Williams, Fleck, Fuchs, Koenig and Kaess2023) as compared to youth behavior (Kaufman et al., Reference Kaufman, Puzia, Godfrey and Crowell2020a, Williams et al., Reference Williams, Fleck, Fuchs, Koenig and Kaess2023). The longitudinal examination of the interplay between child, caregiver, and dyadic effects based on interactional observation should be targeted in future studies.

Stability of maladaptive traits and differences between raters

Baseline and follow-up reports of maladaptive traits showed both convergence and divergence between youth and caregiver ratings (De Los Reyes et al., Reference De Los Reyes, Augenstein, Wang, Thomas, Drabick, Burgers and Rabinowitz2015; Kaurin et al., Reference Kaurin, Do, Ladouceur, Silk and Wright2023a). Our study partially replicated the stronger agreement for externalizing maladaptive traits (Tackett et al., Reference Tackett, Herzhoff, Reardon, Smack and Kushner2013; Tromp & Koot, Reference Tromp and Koot2010), with the strongest agreement for disinhibition but not antagonism. Inter-rater agreement increased between baseline and follow-up in all domains except antagonism, suggesting increasing convergence with age. With the exception of antagonism, youth rated their maladaptive traits as more pronounced than caregivers at both points, speaking to Tackett et al.’s (Reference Tackett, Herzhoff, Reardon, Smack and Kushner2013) findings of higher levels of social desirability in caregivers (Merydith et al., Reference Merydith, Prout and Blaha2003). The shared variance of self- and caregiver-reports in disinhibition ratings was predicted by positive escalation, mutuality, and relationship quality, aligning with findings of greater convergence on externalizing symptoms among adolescents with disorganized attachment (Borelli et al., Reference Borelli, Palmer, Vanwoerden and Sharp2019).

While some studies have explored youth maladaptive trait trajectories (De Clercq et al., Reference De Clercq, Van Leeuwen, Van Den Noortgate, De Bolle and De Fruyt2009, Reference De Clercq, Hofmans, Vergauwe, De Fruyt and Sharp2017; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Cohen, Kasen, Skodol, Hamagami and Brook2000; Laceulle et al., Reference Laceulle, Rienks, Meijer, De Moor and Karreman2023), our findings contrast with normative declines reported in early adolescence up to young adulthood. However, these studies incorporated larger, mixed-gender samples and age-specific approaches. Our study was based on a smaller sample size (N = 129) and a small age range for girls (2.93 years), limiting our capacity to inform age-specific trajectories. None of these studies incorporated the AMPD assessment to evaluate maladaptive trait trajectories. Only one study (Fossati et al., Reference Fossati, Somma, Borroni, Markon and Krueger2017) reported on repeated measures of the PID-5 during adolescence with high temporal stability during a two-month interval. Our data may serve as preliminary evidence to further corroborate relative mean-level stability of AMPD maladaptive traits in adolescent girls. Developmental trajectories of underlying trait dimensions are characterized by higher stability compared to categorical conceptualizations of personality pathology (Hofmans et al., Reference Hofmans, Vergauwe and De Clercq2023). However, future age-sensitive studies based on larger and more diverse samples are urgently needed to comprehensively understand maladaptive trait development in youth, including comparison to non-maladaptive trait development (Soto & Tackett, Reference Soto and Tackett2015).

In our study, the observed behavioral patterns were most reliably linked to self-rated detachment, comprising items of the anhedonia, withdrawal, and intimacy avoidance facets of the PID-5 (Krueger et al., Reference Krueger, Derringer, Markon, Watson and Skodol2012). This finding may, in part, be due to the specific characteristics of the study population oversampled for shy and fearful temperament. These traits entail a risk for the development of internalizing rather than externalizing psychopathology throughout childhood and adolescence (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Baibazarova, Ktistaki, Shelton and Van Goozen2012; Ormel et al., Reference Ormel, Oldehinkel, Ferdinand, Hartman, De Winter, Veenstra, Vollebergh, Minderaa, Buitelaar and Verhulst2005). Fearful-anxious and shy-withdrawn temperament has also been described as behavioral inhibition, which in terms of the five-factor model, reflects a combination of negative affectivity (neuroticism) and detachment (introversion) (Tackett, Reference Tackett2006). While childhood shy and fearful temperament increases risk, moderating and mediating factors contribute to the onset of psychopathology (Liu & Bell, Reference Liu and Bell2020). In this vein, our data imply that reduced positive caregiver–adolescent interactions, notably a lack in relationship satisfaction, may exacerbate patterns of preexisting shyness and interpersonal avoidance associated with low psychological well-being in adolescent samples (De Caluwé et al., Reference De Caluwé, Verbeke, Aken, Heijden and Clercq2019; De Clercq et al., Reference De Clercq, De Fruyt, De Bolle, Van Hiel, Markon and Krueger2014).

At the same time, the detachment domain of the PID-5 most effectively seems to differentiate between clinical and non-clinical adolescents, suggesting that a maladaptive developmental trajectory may be more readily observable in this domain for this age group (De Clercq et al., Reference De Clercq, De Fruyt, De Bolle, Van Hiel, Markon and Krueger2014). Further studies involving diverse at-risk groups, such as children with low effortful control—a trait linked to externalizing psychopathology (Kochanska & Kim, Reference Kochanska and Kim2020; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Sessa, Avenevoli and Essex2002; Ormel et al., Reference Ormel, Oldehinkel, Ferdinand, Hartman, De Winter, Veenstra, Vollebergh, Minderaa, Buitelaar and Verhulst2005)—are needed to distinguish the developmental precursors of the different PID-5 domains in youth. Lastly, caregiver-rated traits appeared to exhibit greater stability over time compared to self-rated traits. Notably, among the self-reported traits, detachment emerged as the least stable domain, suggesting that more residual variance was available to be predicted. This may, in part, explain why the observed interaction patterns were more predictive of changes in self-reported detachment than in other traits, while being less predictive of changes in caregiver-reported traits, where stability left less variance to be accounted for. However, this interpretation should be viewed with caution, because the differences in stability between self- and caregiver-reported traits may also reflect measurement-related factors or individual differences that were not fully captured in the current study.

Limitations

Despite its strengths, some aspects of our study must be evaluated in light of their limitations. We adopted a highly explorative approach due to the paucity of previous data on the relationship between adolescent maladaptive personality traits and interpersonal behavior in critical situations, warranting further replication. Our sample size was small (N = 129) reducing the statistical power to detect small effects.

Moreover, the studied population was limited to girls oversampled for shy and fearful temperament, thus limiting the scope of interactional patterns more characteristic for youth at elevated risk for personality pathology. As outlined in Table 3, we observed little change in PID-5 values from baseline to follow-up assessment. For this reason, our predictive models of change can be considered as conservative, sensitive to small changes. As displayed in supplementary Table S2, S3, associations between dyadic behaviors and personality pathology assessed at follow-up were less sparse.

In our attempt to empirically study the impact of distinct dyadic interaction behaviors on the development of five maladaptive trait domains, we specified multiple unique models for each trait domain and interaction code, thereby increasing the risk for Type I error. Therefore, our results cannot be viewed as definitive and require replication in larger samples. Given the lack of comprehensive studies on the topic, our data offer the opportunity to test the caregiver–adolescent relationship as a sensitive context for developmental personality pathology as highlighted by theory.

Our measures of dyadic interaction were not specifically designed to comprehensively assess interpersonal processes depicted in Criterion A, which would be conceptually more aligned with our assessment choice for personality pathology. Therefore, our investigation should be viewed as a proof of concept aimed at guiding future research directions in this underexplored area.

Another limitation pertains to examining one caregiver only, with the majority being biological mothers. We decided against examining potential moderating effects of the caregiver’s role, as the subgroups are too small for thorough comparisons. Previous studies have shown considerably high agreement between caregivers on personality ratings of their children (De Fruyt & Vollrath, Reference De Fruyt and Vollrath2003; Tackett, Reference Tackett2011). Moreover, caregiver maladaptive traits or psychological adjustment, influencing parental reports on their children (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Durbin, Donnellan and Neppl2017; Vanwoerden et al., Reference Vanwoerden, McLaren, Stepp and Sharp2023), as well as family interactions (Sell et al., Reference Sell, Daubmann, Zapf, Adema, Busmann, Stiawa, Winter, Lambert, Wegscheider and Wiegand-Grefe2021), were not incorporated in our analyses. Although we instructed the girls to attend with their primary caregiver, we do not assess with whom they typically experience conflict or how relationship dynamics may vary within the broader family context. Caregivers might be inclined to provide socially desirable ratings of their children (Merydith et al., Reference Merydith, Prout and Blaha2003) or tend to rate problematic externalizing behavior more appropriately (De Los Reyes et al., Reference De Los Reyes, Augenstein, Wang, Thomas, Drabick, Burgers and Rabinowitz2015). This might be highlighted in adolescence, when due to increased autonomy and time spent with peers, caregivers may not be fully aware their offspring’s risk behaviors (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Bucholz, Reich, Fox, Kuperman, Kramer, Hesselbrock, Dick, Nurnberger, Edenberg and Bierut2006). Thus, including peer or teacher informant ratings may shed further light on maladaptive trait development during adolescence (Kraemer et al., Reference Kraemer, Measelle, Ablow, Essex, Boyce and Kupfer2003).

Previous research has shown that personality pathology items translated from adult samples may not be developmentally sensitive to specific behaviors in youth, potentially affecting reliability findings on scales such as the PID-5-BF (De Clercq et al., Reference De Clercq, De Fruyt, De Bolle, Van Hiel, Markon and Krueger2014; Fossati et al., Reference Fossati, Somma, Borroni, Markon and Krueger2017; Koster et al., Reference Koster, Laceulle, Van Der Heijden, Klimstra, De Clercq, Verbeke, De Caluwé and Van Aken2020; Romero & Alonso, Reference Romero and Alonso2019). Our sample was predominantly white, and we studied a population of girls based on birth assigned gender, rather than including diverse gender identities. Current personality pathology theory largely fails to acknowledge the role of social context beyond the most immediate interaction partners (e.g., caregivers). Yet, the defining features of personality pathology can be influenced by sociocultural context and minority youth repeatedly experience stressors that are not evoked by themselves but by a context that marginalizes their experience. This may result in behavior (e.g., decreased interpersonal trust, and reticence) interpreted as personality pathology but more likely represents an adaptive habitual response to a continued experience of stigma. As a field, we need to improve on studying pathways of psychosocial functioning in youth with a more fine graded understanding of how the same behavior patterns may be adaptive and dysfunctional regarding the broader social context (Campbell & Allison, Reference Campbell and Allison2022; Rodriguez-Seijas et al., Reference Rodriguez-Seijas, Rogers and Asadi2023).

Conclusion and outlook

This study pioneers the application of a comprehensive behavioral assessment paradigm to developmental personality pathology research within the dimensional framework of the AMPD. It involves repeated assessments of maladaptive traits during a critical developmental period, an area previously underexplored in behavioral observation. Our findings underscore how adolescent-caregiver interactions influence maladaptive trait expression over time (De Fruyt & De Clercq, Reference De Fruyt and De Clercq2014), highlighting the importance of studying contextualized dynamic processes in developmental psychopathology (Kaurin et al., Reference Kaurin, King and Wright2023b). The development of personality pathology in girls is affected by interpersonal dynamics, particularly a lack of positive communication with primary caregivers. This highlights early adolescence as a developmental stage, where youth are receptive to environmental influence, including protective effects of positive social experiences (Sisk & Gee, Reference Sisk and Gee2022).

By focusing on observable behaviors, our study sheds light on specific interaction patterns that could be targeted in interventions, such as fostering perspective-taking during discussions. Additionally, our results suggest that girls’ self-reports provide valuable insights and may be more informative than parent-reported measures of personality pathology. Longitudinal research spanning early childhood and adolescence is necessary to grasp the interplay and associated trajectories of interpersonal interaction and trait vulnerabilities, pinpointing sensitive risk-signatures (Feldman, Reference Feldman2010).

Acknowledgements

N/A.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579425000252.

Funding statement

This study was supported by NIH grants (R01 MH103241; UL1 TR001857; F32 MH127880). The opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and not those of the funding source. Our consent form did not request permission for open sharing of the data, and therefore we are unable to post the data online.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.