Introduction

High-quality parenting, characterized by high sensitivity, warmth, and responsiveness and low intrusiveness and detachment, can strengthen parent-child bonds and promote children’s language acquisition, cognitive development, and social-emotional skills (Fay-Stammbach et al., Reference Fay-Stammbach, Hawes and Meredith2014; Jeong et al., Reference Jeong, Franchett, Ramos De Oliveira, Rehmani and Yousafzai2021; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Criss, Silk and Houltberg2017). In two-parent families, parents not only engage in parenting behavior individually but also work together as a team to manage their parenting responsibilities. According to the relational developmental systems theory (Wanless, Reference Wanless2016), how parents coparent – chiefly, the extent to which they support or undermine each other in parenting – serves as an important relational context for parents to develop and perform their individual parenting behavior (Schoppe-Sullivan et al., Reference Schoppe-Sullivan, Settle, Lee and Kamp Dush2016).

However, in different-sex parent families, parental roles may not be the same for mothers and fathers. Especially in infancy, mothers are typically expected to “captain” the parenting team, providing intensive care, warmth, and emotional support, whereas fathers are often socialized as helpers instead of as equal partners in the coparenting team (Palkovitz et al., Reference Palkovitz, Trask and Adamsons2014). As a result, some have argued that fathers’ parenting behaviors may be more dependent on relational context (i.e., coparenting relationships) with partners than mothers’ parenting behaviors. This idea is reflected in the father vulnerability hypothesis (Cummings et al., Reference Cummings, Merrilees and George2010).

The father vulnerability hypothesis originated from research on interparental conflict and suggests that fathers or fathering behaviors are more vulnerable to the adverse impact of marital discord (Cummings et al., Reference Cummings, Merrilees and George2010). However, Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Schoppe-Sullivan, Yan and Yoon2023) proposed that the term “susceptibility” might offer a more accurate representation than “vulnerability,” given that the hypothesized stronger connection of interparental relationships to fathering than to mothering need not be limited to the negative aspects of interparental relationships. We argue that susceptibility or vulnerability is not a weakness of parents but reflects parents’ varying dependence on the relational context. Moreover, we posit that susceptibility is not confined to fathers nor solely due to their gender or role. Both mothers and fathers are likely affected by the coparenting relationship, although perhaps to different extents and in different ways. Given the critical role of social and cultural forces in shaping parental roles (Palkovitz et al., Reference Palkovitz, Trask and Adamsons2014), the notion of greater vulnerability or susceptibility of fathers solely on the basis of their gender or role could be constrained by time and place.

Indeed, the roles of fathers have witnessed significant changes in the past 50 years. Dual-earner households have become prevalent in the U.S. (Sullivan, Reference Sullivan2020), and fathers have doubled their time in developmental and physical child care since the 1980s (Sayer, Reference Sayer, McHale, King, Van Hook and Booth2016). At the same time, however, mothers’ time spent with children has not decreased but also increased (Sayer, Reference Sayer, McHale, King, Van Hook and Booth2016), and mothers continue to be primary caregivers in most families (Dagan & Sagi-Schwartz, Reference Dagan and Sagi-Schwartz2021). While the roles of mothers and fathers are arguably gradually converging, some distinctions persist (Fagan et al., Reference Fagan, Day, Lamb and Cabrera2014). Evolving parental and gender norms may introduce greater variability within gender roles, particularly for fathers. Thus, the current study goes beyond a binary parent gender perspective to delve more deeply into factors that are indicative of mothers’ and fathers’ individual susceptibility to the relational context of coparenting.

Informed by the developmental relational systems and ecological perspectives (Feinberg, Reference Feinberg2003; Wanless, Reference Wanless2016), the current study examined the roles of parents’ personal characteristics (i.e., beliefs about parental roles and perceptions of parenting) and children’s characteristics (i.e., infant temperament) in shaping links between coparenting and parenting for mothers and for fathers. To perform a rigorous examination, the current study adopted cross-lagged panel models to investigate directional associations between coparenting and parenting and separately examined positive and negative aspects of coparenting and parenting behavior to distinguish vulnerability and susceptibility. In taking these steps, the current study expands and enriches theory regarding links between coparenting and parenting behavior and provides valuable information for intervention programs regarding whose parenting behavior is most strongly affected by coparenting relationships and for whom limited resources should be prioritized.

Supportive/undermining coparenting and parenting quality

Coparenting refers to how parents or parental figures coordinate their joint parenting responsibilities (Feinberg, Reference Feinberg2003). There are several different conceptualizations of the internal structure of coparenting (e.g., Feinberg, Reference Feinberg2003; Margolin et al., Reference Margolin, Gordis and John2001; Van Egeren & Hawkins, Reference Van Egeren and Hawkins2004), but there is no clear consensus on which and how many dimensions are part of the coparenting construct. It is broadly agreed that coparenting undermining and coparenting support are critical components of the coparenting relationship and are commonly included in assessments of coparenting relationship quality (see Mollà Cusí et al., Reference Mollà Cusí, Günther-Bel, Vilaregut Puigdesens, Campreciós Orriols and Matalí Costa2020 for a review). A supportive coparenting relationship is characterized by cooperation, respect, trust, acknowledgement, and encouragement for partners on child-related work, whereas an undermining coparenting relationship is characterized by competition, discouragement, disparagement, blaming, and conflict between parents (Feinberg, Reference Feinberg2003; Margolin et al., Reference Margolin, Gordis and John2001; Van Egeren & Hawkins, Reference Van Egeren and Hawkins2004).

From the relational developmental systems perspective, one’s behavior is the result of the co-constructions of individual and context (Lerner, Reference Lerner2015; Wanless, Reference Wanless2016). Parents, as individuals, have agency in parenting, and how parents enact their agency is shaped by the relational context and their sense of safety in the relational context (Schoppe-Sullivan et al., Reference Schoppe-Sullivan, Settle, Lee and Kamp Dush2016). If individuals perceive a sense of safety in a relational context, they may feel comfortable with taking interpersonal risks (e.g., speak up, make suggestions, admit mistakes) and are more likely to take initiative, learn, act, and contribute to shared goals without concern for potential embarrassment or shame (Edmondson & Lei, Reference Edmondson and Lei2014). In the development of parenting behavior, the coparenting relationship is a proximal relational context (Schoppe-Sullivan et al., Reference Schoppe-Sullivan, Settle, Lee and Kamp Dush2016). Supportive coparenting may offer parents a sense of security to engage in parenting, practice parenting behavior, and ultimately gain parenting competence. Conversely, undermining coparenting may lead to a low sense of safety for parents to engage in and practice parenting behaviors, and parents may be less likely to learn from each other, ultimately not developing high-quality parenting.

Accumulating evidence has supported the associations between supportive/undermining coparenting and parenting behavior. For example, observed supportive coparenting was associated with higher parenting quality (i.e., high sensitivity, high positive regard, and low detachment) in new fathers with infants (Altenburger & Schoppe-Sullivan, Reference Altenburger and Schoppe-Sullivan2020). Mothers’ reports of higher levels of positive coparenting and lower levels of negative coparenting were associated with higher observed maternal emotional availability (i.e., sensitivity, structuring, non-hostility, non-intrusiveness) in infants’ first year of life (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Fredman and Teti2021). In families that displayed more undermining behaviors in coparenting at three months postpartum, mothers showed more harsh intrusive parenting at nine months postpartum (Zvara et al., Reference Zvara, Altenburger, Lang and Schoppe-Sullivan2019). A few randomized and controlled trials suggest that intervention programs targeting increasing positive coparenting behavior and reducing negative coparenting behavior can benefit parents’ parenting quality (e.g., Ammerman et al., Reference Ammerman, Peugh, Teeters, Sakuma, Jones, Hostetler, Van Ginkel and Feinberg2022; Feinberg et al., Reference Feinberg, Jones, Hostetler, Roettger, Paul and Ehrenthal2016).

Factors that shape parents’ susceptibility to coparenting relationships

Although the relational context is important for individuals to thrive, susceptibility to the relational context varies across individuals (Schoppe-Sullivan et al., Reference Schoppe-Sullivan, Settle, Lee and Kamp Dush2016; Wanless, Reference Wanless2016). As suggested by the father vulnerability hypothesis (Cummings et al., Reference Cummings, Merrilees and George2010), the traditional hierarchy of parenting where mothers are primary caregivers and fathers are secondary caregivers (Palkovitz et al., Reference Palkovitz, Trask and Adamsons2014) may render fathers’ parenting behavior easily affected by their relationships with mothers. The father vulnerability hypothesis emphasizes the adverse impact of marital discord on parenting. However, if fathering behaviors are more vulnerable, they are likely not only more vulnerable to the impact of negative interparental relationships but also more sensitive to the benefits of positive interparental relationships, thus demonstrating greater susceptibility to the relational context.

Moreover, coparenting relationships are arguably a more proximal context for parenting and child development than other aspects of interparental relationships (such as marital discord, emphasized by the father vulnerability hypothesis), but limited studies have rigorously investigated the father vulnerability/susceptibility hypothesis in the coparenting context. Studies that have done so have supported a general positive association between coparenting relationship quality and parenting behavior, but these studies did not investigate whether fathers were only more strongly affected by negative aspects (vs. both positive and negative aspects) of coparenting relationships than mothers and did not provide consistent evidence. For example, a few studies have examined associations between coparenting relationships and different aspects of parenting, such as parental sensitivity (Wang & Schoppe-Sullivan, Reference Wang and Schoppe-Sullivan2023), parental involvement (Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Gallegos, Jacobvitz and Hazen2017; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Schoppe-Sullivan, Yan and Yoon2023), and parental adjustment (Solmeyer & Feinberg, Reference Solmeyer and Feinberg2011). Some studies indicate that fathers’ parenting is more affected by coparenting relationships than mothers’ parenting (Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Gallegos, Jacobvitz and Hazen2017; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Schoppe-Sullivan, Yan and Yoon2023), whereas others do not (Solmeyer & Feinberg, Reference Solmeyer and Feinberg2011; Wang & Schoppe-Sullivan, Reference Wang and Schoppe-Sullivan2023). The mixed findings of these studies, plus the evidence for converging roles of fathers and mothers (Fagan et al., Reference Fagan, Day, Lamb and Cabrera2014), suggest the importance of going beyond testing this hypothesis from a binary gender perspective and further exploring factors that may be indicative of individual parents’ variability in susceptibility to coparenting relationships.

Factors other than individual/family roles may contribute to parents’ susceptibility to the coparenting context. The ecological model of coparenting, outlined by Feinberg (Reference Feinberg2003), positions coparenting as a protective factor capable of mitigating the effects of individual, familial, and extrafamilial risks on family outcomes. However, from the relational developmental perspective, a supportive relational context may not only buffer against risks but also promote individual development. Thus, the current study extends the initial propositions of the ecological model of coparenting, proposing that coparenting not only serves as a buffer against risks, but also fosters developmental strengths. Therefore, the current study sought to explore parent characteristics and child characteristics that shape parents’ susceptibility to the coparenting relationship.

Beliefs about parental roles

Progressive parental role beliefs. Progressive parental role beliefs refer to the beliefs that mothers and fathers are equally responsible for parenting and should share parenting duties. However, given that parents are more likely to endorse equal or mother-centric beliefs than father-centric beliefs, parental role beliefs may manifest differential impacts on mothers and fathers. With progressive parental role beliefs, mothers are more likely to encourage fathers’ involvement, and fathers are more engaged in caregiving and demonstrate higher competence in childcare (Schoppe-Sullivan et al., Reference Schoppe-Sullivan, Brown, Cannon, Mangelsdorf and Sokolowski2008; Wang & Cheung, Reference Wang and Cheung2023). Endorsing progressive and traditional parental role beliefs is unlikely to make mothers feel that they are less critical as parents or make maternal involvement more dependent on relationships with fathers. In contrast, fathers with more progressive parental role beliefs are more likely to have clear expectations and standards for themselves as parents, which may make fathers’ involvement in parenting less dependent on their relationships with mothers, and hence, curtail the spillover from the coparenting relationship to parenting behaviors. Thus, endorsing less progressive parental role beliefs may make fathers’ parenting quality more strongly affected by the coparenting relationship, whereas mothers’ beliefs about parental roles may not affect their susceptibility to the coparenting relationship.

Maternal essentialism. Maternal essentialism refers to the belief that mothers are biologically and naturally more suitable for and better at parenting than fathers. Maternal essentialism beliefs center on parents’ predispositions and are distinct from parental role beliefs that focus on parents’ obligations (Gaunt & Deutsch, Reference Gaunt and Deutsch2024). It is possible that parents who adopt egalitarian parental beliefs still believe that mothers have a natural advantage in parenting. If mothers believe in maternal essentialism, they are more likely to be in charge of childcare responsibilities, set high standards for childcare, and consciously or unconsciously inhibit fathers’ involvement in parenting (Pinho & Gaunt, Reference Pinho and Gaunt2021). In contrast, if fathers believe in maternal essentialism, they tend to take shorter paternity leaves (Berrigan et al., Reference Berrigan, Schoppe-Sullivan and Kamp Dush2021) are less involved in childcare and housework (Pinho & Gaunt, Reference Pinho and Gaunt2021), and their parenting behaviors may be more likely to be shaped and regulated by mothers and relationships with mothers. As a result, the coparenting relationship may have a more substantial effect on fathers’ parenting behavior when fathers endorse maternal essentialism, but coparenting may have little impact on mothers’ parenting behavior when mothers endorse maternal essentialism.

Parenting perfectionism. Parenting perfectionism denotes the tendency to set excessively high standards for parenting, which may influence parents’ parental adjustment and parenting behavior (e.g., Lee et al., Reference Lee, Schoppe-Sullivan and Kamp Dush2012). Although few studies have investigated the associations between parenting perfectionism and parenting behavior in families of infants, studies on families with older children have shown that parenting perfectionism, especially maladaptive parenting perfectionism, is associated with negative parenting behaviors (e.g., overcontrol, psychological control; Affrunti & Woodruff-Borden, Reference Affrunti and Woodruff-Borden2015; Soenens et al., Reference Soenens, Elliot, Goossens, Vansteenkiste, Luyten and Duriez2005). Greater parenting perfectionism may not only affect parenting behaviors directly but may also shape parents’ susceptibility to other influences in the family system. Regardless of the type of perfectionism, parents pursuing parenting perfectionism are likely to set high standards for themselves and may feel obligated to be perfect parents, which may render their parenting behavior less driven by the support and undermining perceived from the relational context but more by internal motivation.

Perceptions of parenting

Parenting self-efficacy. Parenting self-efficacy is parents’ confidence in their parenting competence. There is abundant evidence in support of the positive link between parenting self-efficacy and parenting quality (see Albanese et al., Reference Albanese, Russo and Geller2019, for a review). Parenting self-efficacy may not only directly influence parenting behavior but may also buffer or magnify the impact of other family processes on parenting behavior. Theories on the broad construct of self-efficacy and parenting self-efficacy, in particular, point out that people with low or high self-efficacy have differential cognitive, affective, motivational, and behavioral reactions to task situations (Bandura, Reference Bandura1982; Coleman & Karraker, Reference Coleman and Karraker1998). Parents with low parenting self-efficacy are likely to have negative thoughts (e.g., self-doubt), experience negative feelings (e.g., anxiety, stress, hopelessness), show low motivation, and procrastinate or even avoid engaging in parenting tasks, which also signifies a greater need for support from relational context to overcome these reactions. These reactions may make parents more vulnerable to the adverse impact of undermining coparenting behavior and more sensitive to supportive coparenting behavior than more self-efficacious parents.

Infant temperament

Children also contribute to shaping family processes. Infant temperament includes a set of biologically based individual differences in reactivity and self-regulation present early in life (Rothbart, Reference Rothbart, Zentner and Shiner2012). Although different numbers of temperament traits and different labels are used across temperament theories, researchers agree on core domains of temperament (Sanson et al., Reference Sanson, Letcher, Havighurst, Sanders and Morawska2018), such as regulatory capacity and negative affect. Regulatory capacity, also known as effortful control, refers to the control or regulation of attention, emotions, and behaviors (e.g., can be soothed). Negative emotionality reflects children’s expression of negative emotions (e.g., anger, fearfulness, sadness). Other key domains of temperament, like surgency, may not particularly challenge or ease parenting and thus are not included in the current study.

Infant temperament can shape parenting behaviors such that difficult or negative temperament can elicit negative parenting behaviors, whereas easy or positive temperament traits are associated with more positive parenting behaviors (e.g., Bridgett et al., Reference Bridgett, Gartstein, Putnam, McKay, Iddins, Robertson, Ramsay and Rittmueller2009; Padilla et al., Reference Padilla, Hines and Ryan2020). Infant temperament may interact with coparenting to affect parenting behaviors (Feinberg, Reference Feinberg2003). Challenging infant temperament elevates the difficulty and uncertainty of parenting tasks and, as a result, increases parents’ susceptibility to the relational context. When infants have difficult temperamental characteristics (i.e., high negative affect and low regulatory capacity), support and encouragement from partners may be more influential in promoting positive parenting behavior, and undermining and discouragement from partners may also prompt more negative parenting behavior, compared to cases in which infants have easier temperamental characteristics.

The current study

Grounded in the relational developmental systems theory and ecological coparenting model (Feinberg, Reference Feinberg2003; Schoppe-Sullivan et al., Reference Schoppe-Sullivan, Settle, Lee and Kamp Dush2016; Wanless, Reference Wanless2016), the current study sought to expand the father vulnerability/susceptibility hypothesis from a binary gender perspective to a focus on variability in mothers’ and fathers’ susceptibility to the relational context to answer the central question: Whose parenting behavior is most susceptible to coparenting relationships? Specifically, the current study aimed to 1) investigate associations of supportive and undermining coparenting with positive and negative parenting behavior in new mothers and fathers, 2) test whether the links between coparenting and parenting are stronger for fathers than for mothers, and whether the magnitude of the association depends on the positive or negative component tested, and 3) examine parents’ beliefs about parental roles, parents’ perceptions of parenting, and infant temperament as moderators of the associations between coparenting and parenting. In addition, given reciprocal links between family subsystems (Cox & Paley, Reference Cox and Paley1997) and previous evidence on how parenting may affect coparenting (e.g., Bernier et al., Reference Bernier, Cyr, Matte-Gagné and Tarabulsy2023; Bureau et al., Reference Bureau, Deneault, Yurkowski, Martin, Quan, Sezlik and Guérin-Marion2021; Jacobvitz et al., Reference Jacobvitz, Aviles, Aquino, Tian, Zhang and Hazen2022), the current study adopted cross-lagged panel models to rigorously examine the directional associations between coparenting and parenting.

We hypothesized that supportive coparenting would be associated with more positive parenting behavior, and undermining coparenting would be associated with more negative parenting behavior for both mothers and fathers. We expected that the associations between coparenting and parenting would be stronger for fathers than for mothers regardless of the valence (i.e., positive or negative). We further anticipated that for fathers with a more traditional view about parental roles (low progressive role beliefs, higher maternal essentialism), parents with low expectations about parenting (low parenting perfectionism), parents who were less confident in parenting (low parenting self-efficacy), and parents with more challenging infants (high negative affect, low regulatory capacity), their parenting behavior would be more strongly affected by coparenting quality.

Method

Participants and procedure

Data were drawn from a longitudinal study of different-sex dual-earner couples transitioning to parenthood. Eligible couples were 1) expecting their first biological child; 2) at least 18 years old; 3) able to read and speak English; 4) both working for pay and expecting to return to work shortly after childbirth; 5) married or cohabiting. The methods of recruitment included flyers at doctors’ offices, visits to childbirth education classes, advertisements in newspapers, participant referrals, and word of mouth. The project was conducted under the oversight and approval of The Ohio State University Institutional Review Board (Protocol # 2007B0228).

A total of 182 families participated in this project. Of mothers, 85.16% identified as White, 6.04% as Black/African American, 2.75% as Asian, and 6.04% as other or mixed race; of fathers, 85.56% identified as White, 6.67% as Black/African American, 3.89% as Asian or Pacific Islander, and 3.89% as other or mixed race. Parents were relatively highly educated, with 75.27% of mothers and 65.38% of fathers having completed at least a bachelor’s degree. The mean of annual household income in the sample was $81,193 (SD = $42,297); 13.33% of families had annual household income below $40,000, 38.89% had income between $40,000 and $80,000, 31.67% had income between $80,000 and $120,000, and 16.11% had income above $120,000. As for marital status, 86.26% of couples were married, and 13.74% were cohabiting at the third trimester of pregnancy. In 48.31% of families, the first-born child was a girl.

The current study used data collected at the third trimester of pregnancy (T0), three months postpartum (3M), and nine months postpartum (9M). At T0 and 3 M, home visits were conducted to collect the data. At 9 M, participants were all invited to participate in the follow-up study at a research space at a local science museum, but a third of the families opted to complete the study at their homes. At T0, mothers and fathers independently reported their beliefs about progressive parental roles, beliefs about maternal essentialism, and parenting perfectionism. At 3 M, fathers and mothers independently reported parenting self-efficacy and infant temperament. To measure coparenting quality, mothers and fathers were asked to play with their infants together with provided toys as they usually did for 5 minutes at 3 M and were asked to teach their children to play with two toys for 10 minutes at 9 M. To capture parenting quality, mothers and fathers were asked to play with their children separately as they usually did for 5 minutes at 3 M and were asked to teach their children to play with a randomly assigned toy for 5 minutes at 9 M. At each time point, which parent played with the child first was determined randomly.

Measures

Progressive parental role beliefs at T0. Parents reported their progressive parental role beliefs using the Beliefs Concerning the Parental Role Scale (Bonney & Kelley, Reference Bonney and Kelley1996). The scale contains 26 items (e.g., “It is equally as important for a father to provide financial, physical, and emotional care to his children”). Parents rated their degree of agreement or disagreement with the statements on a 5-point Likert scale, from “1 = Disagree strongly” to “5 = Agree strongly.” The scale had good reliability: αMother = .86, and αFather = .85.

Maternal essentialism at T0. Three items from the Survey of First-Time Mothers (Beitel & Parke, Reference Beitel and Parke1998) were used to capture parents’ beliefs in maternal essentialism. Parents rated their degree of agreement with the statements (e.g., “Mothers are naturally more sensitive to a baby’s feeling than fathers are”) on a 5-point Likert scale, from “1 = Disagree strongly” to “5 = Agree strongly.” The scale had good reliability: αMother = .86, and αFather = .84.

Parenting perfectionism at T0. Twelve items from the Multidimensional Parenting Perfectionism Questionnaire (Snell et al., Reference Snell, Overbey and Brewer2005) were employed to evaluate parents’ self-oriented parenting perfectionism, desired partner parenting perfectionism, and societal-prescribed parenting perfectionism. Parents were asked to evaluate to which degree the statements (e.g., “I set very high standards for myself as a parent”) were characteristic of themselves in terms of what they thought their response would most likely be after the birth of their child. Parents rated these items on a 5-point Likert scale, from “1 = Not at all characteristic of me” to “5 = Very characteristic of me.” Items were averaged to represent overall parenting perfectionism, αMother = .91, and αFather = .87.

Parenting self-efficacy at 3M. Mothers and fathers reported their parenting self-efficacy using the Parenting Self-Efficacy Measure (Teti & Gelfand, Reference Teti and Gelfand1991). Parents reported how good they were at dealing with ten common situations that parents of infants encounter (e.g., soothing the infant when he/she is upset, fussy, or crying). Parents reported their self-efficacy on a 4-point scale from “1 = Not good at all” to “4 = Very good.” The reliability of the scale was acceptable: αMother = .78, and αFather = .84.

Infant temperament at 3M. Mothers and fathers independently reported the frequencies of children’s certain behaviors in the last week using items from the very short form of the Infant Behavior Questionnaire (Rothbart & Gartstein, Reference Rothbart and Gartstein2000). The negative affect subscale assesses children’s display of negative emotions and behaviors (12 items; e.g., “When tired, how often did your baby show distress”). The regulatory capacity subscale captures how easily children’s emotions can be regulated or soothed (12 items; e.g., “When singing or talking to your baby, how often did she/he soothe immediately”). Parents reported the frequencies of their children’s behavior on a 7-point scale from “1 = Never” to “7 = Always.” Additionally, parents could choose “Does not apply” for each of the behaviors. The reliability was good for the negative affect subscale (αMother = .80 and αFather = .82) and acceptable for the regulatory capacity subscale (αMother = .65 and αFather = .72). Mothers’ and fathers’ reports of infant temperament were significantly correlated and were averaged to indicate infant negative affect and regulatory capacity, rs = .44 and .25, respectively, ps < .01.

Observed coparenting quality at 3 M and 9M. At 3 M, mothers and fathers were asked to play with their infants together as they would usually do using an infant play gym for five minutes. At 9 M, mothers and fathers were asked to teach their children to play with two novel toys (jack-in-the-box and pop-up toy) together for ten minutes. Two different coding teams coded the coparenting interactions at 3 M and 9 M using coding scales that were developed by Cowan and Cowan (Reference Cowan and Cowan1996) and used in previous coparenting studies (e.g., Altenburger et al., Reference Altenburger, Schoppe-Sullivan, Lang, Bower and Kamp Dush2014). Coparenting cooperation (i.e., help and support for each other) and coparenting competition (i.e., attempts to outdo each other’s efforts to teach and play with children) at the team level were coded. We also captured mothers’ and fathers’ pleasure and displeasure in their partners’ interactions and relationships with their children during the interactions. Coders rated parents’ behaviors on a five-point scale. Coders overlapped on 50.6% and 56.2% of the cases at 3 M and 9 M, respectively. The gamma statistics ranged from .72 to .81 at 3 M and from .64 to .86 at 9 M. Coparenting cooperation and pleasure scores were highly correlated at both 3 M and 9 M (rs = .61 – 81, ps < .05) and were averaged to indicate supportive coparenting. Coparenting competition and displeasure scores were highly correlated at 9 M (rs = .75 – .81, ps < .05) but not at 3 M. Further examination showed that it was caused by a lack of variability in displeasure variables at 3 M, given that 77.65% of mothers and 87.06% of fathers showed no displeasure during the coparenting interactions. Guided by previous studies (e.g., Altenburger et al., Reference Altenburger, Schoppe-Sullivan, Lang, Bower and Kamp Dush2014) and to capture a range of negative coparenting behavior, we still averaged coparenting competition and displeasure to indicate undermining coparenting. Additionally, analyzing the models using competition scores rather than the composite undermining coparenting scores did not alter the results (see Supplemental Tables A and B).

Observed parenting quality at 3 M and 9M. At 3 M, mothers and fathers were each asked to play separately with their children as they typically do for five minutes. The focal parent played with their child alone in the first 3 minutes and with the presence of the other parent in the subsequent 2 minutes. At 9 M, fathers and mothers were separately asked to teach their children to play with a randomly assigned toy (either a shape sorter or stacking rings) for 5 minutes. These dyadic interactions were coded using the Parent-Child Coding Manual (adapted from Cox & Crnic, Reference Cox and Crnic2002). Five dimensions of parenting quality were captured: 1) sensitivity (e.g., manifesting awareness of the child’s needs, moods, interests, and capabilities and responding accordingly); 2) positive regard (e.g., speaking in a warm tone); 3) non-detachment (detachment in the interaction was captured and then reversed, e.g., rarely making eye contact or rarely talking to the child); 4) intrusiveness (e.g., insisting that the child do something that the child is not interested in doing); and 5) negative regard (e.g., negative tone of voice). Two separate coding teams coded parent-child interactions at 3 M and 9 M (no overlap with the coparenting coding teams). All the interactions were double-coded, and averaged scores were used. For the dyadic interactions at 3 M, parenting behaviors in the two parts of the interaction were coded separately first, and then weighted average scores were generated so that they were comparable to the scores at 9 M. The gamma statistics ranged from .60 to .93 at 3 M and ranged from .57 to .93 at 9 M. Following previous studies that used the same coding system (e.g., Olsavsky et al., Reference Olsavsky, Berrigan and Schoppe-Sullivan2020) and given the correlations among these parenting subdimensions, we averaged sensitivity, non-detachment, and positive regard to represent positive parenting, and averaged intrusiveness and negative regard to represent negative parenting.

Analytic plan

Preliminary data analyses were performed using SPSS 28. The means, standard deviations, valid cases, and correlations of primary variables were calculated. No available data were excluded from the analysis. The current study had missing data due to attrition, parents skipping certain questions, and failure to complete the observational tasks. Little’s Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) test was used to examine missing data patterns. Demographic variables included in the test were mothers’ and fathers’ age, race, education levels, household income, marital status, and child gender.

Primary data analyses were conducted using R 4.2.0, with the package “lavaan” (Rosseel, Reference Rosseel2012). In the primary data analyses, first, we tested two cross-lagged panel models, with one model focusing on supportive coparenting and positive parenting and the other focusing on undermining coparenting and negative parenting. All the possible stability paths and cross-lagged paths among observed coparenting, mothers’ parenting behavior, and fathers’ parenting behavior at 3 M and 9 M were included. Given that these two models were saturated, model fit indices are not reported. Second, we constrained the paths from supportive coparenting (undermining coparenting) at 3 M to mothers’ and fathers’ positive parenting (negative parenting) at 9 M to be equal to see whether the model fit changed significantly. We also tested models including both supportive and undermining coparenting and either positive or negative parenting, as well as models including both supportive and undermining coparenting and both positive and negative parenting. The results showed that only supportive coparenting was significantly associated with positive parenting behavior and only undermining coparenting was significantly associated with negative parenting behavior. These results are presented in Supplemental Tables C to H, given their inferior simplicity and collinearity issues. Third, we tested the moderating roles of parents’ beliefs about parental roles, perceptions of parenting, and infant temperament in the associations between coparenting at 3 M and parenting behavior at 9 M. Moderators and interaction terms (i.e., products) were added to the models, with one moderator included at a time. For significant moderators, simple slopes analysis was conducted to detect the patterns of moderation effects.

Results

The means, standard deviations, and correlations among the main variables of interest are shown in Tables 1–3. Little’s missing test suggested that the data were missing completely at random, χ2(1066) = 1197.073, p = .248. Full information maximum likelihood estimation was employed in the primary data analyses.

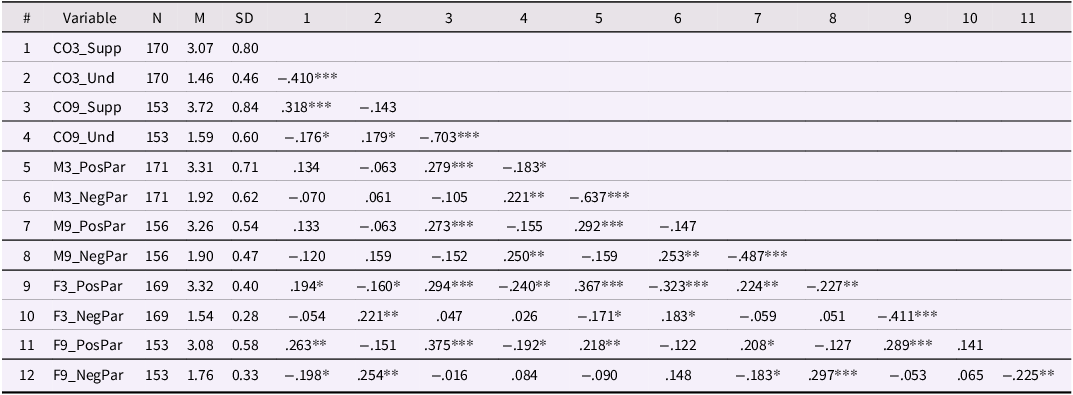

Table 1. Valid cases, means, standard deviations, and correlations of coparenting and parenting behavior variables

Note. CO = Coparenting; 3/9 = At three/nine months; M = Mother; F = Father; Supp = Support; Und = Undermining; PosPar = Positive parenting; NegPar = Negative parenting. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

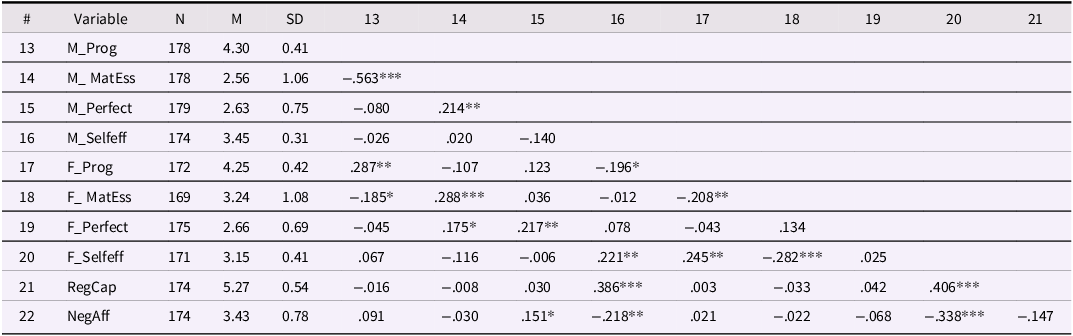

Table 2. Valid cases, means, standard deviations, and correlations of the potential moderators

Note. M = Mother; F = Father; Prog = Progressive parental role beliefs; MatEss = Maternal Essentialism; Perfect = Parenting perfectionism; Selfeff = Parenting self-efficacy; RegCap = Infant regulatory capacity; NegAff = Infant negative affect. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

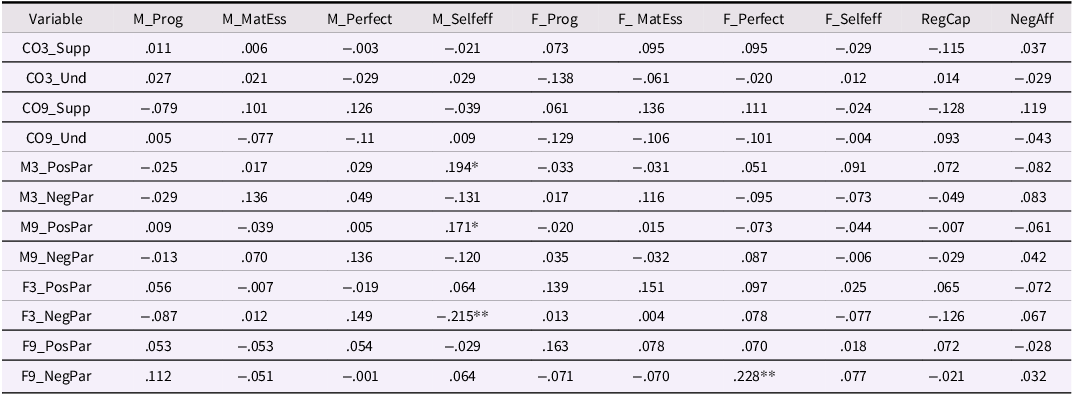

Table 3. Correlations of coparenting behavior, parenting behavior, and potential moderators

Note. 3/9 = Three/nine months, CO = Coparenting; M = Mother; F = Father; Supp = Support; Und = Undermining; PosPar = Positive parenting; NegPar = Negative parenting; Prog = Progressive parental role beliefs; MatEss = Maternal Essentialism; Perfect = Parenting perfectionism; Selfeff = Parenting self-efficacy; RegCap = Infant regulatory capacity; NegAff = Infant negative affect. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Supportive coparenting and positive parenting

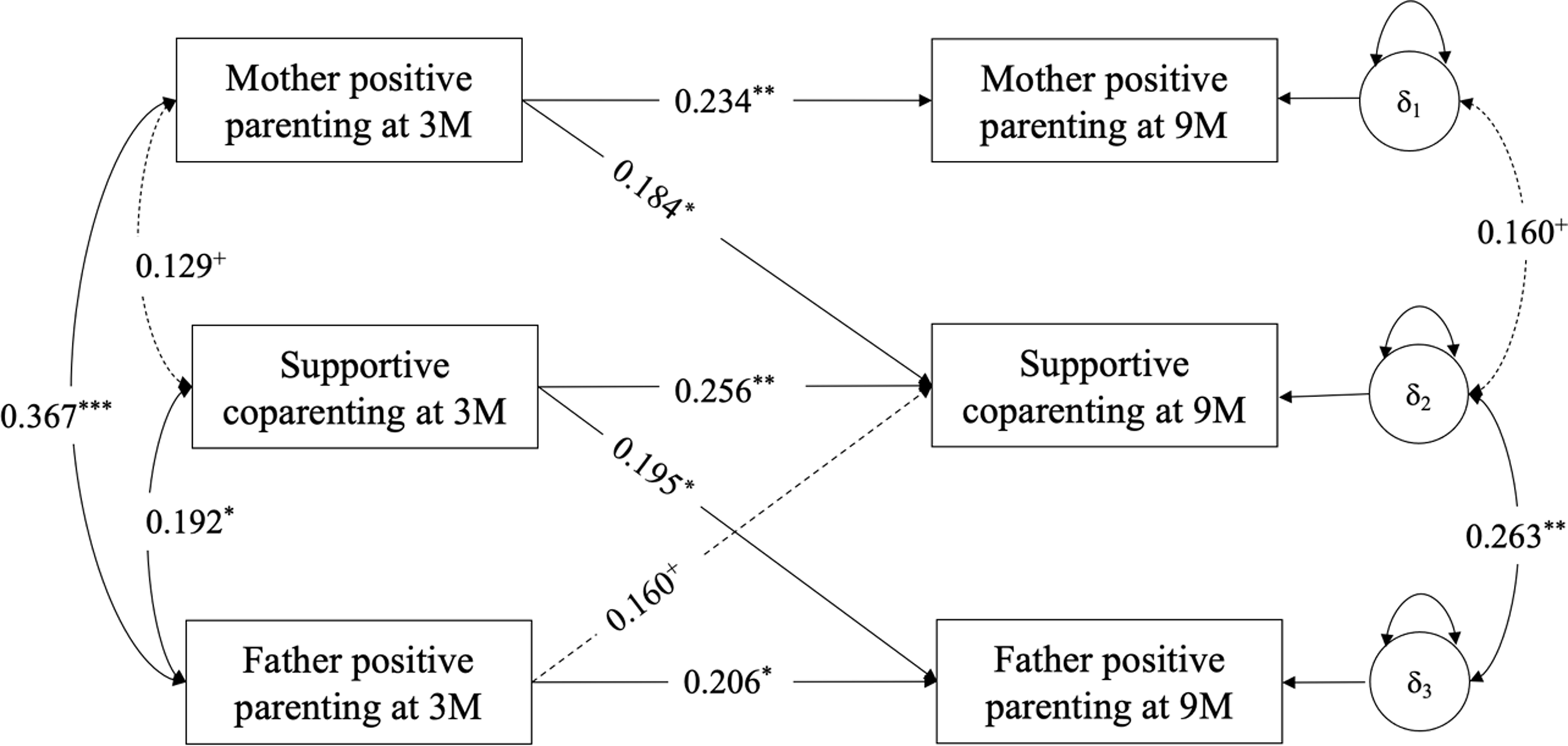

The associations between supportive coparenting and positive parenting behavior are presented in Figure 1 and Supplemental Table I. Mothers’ positive parenting behaviors (β = 0.234, z = 2.781, p = .005), fathers’ positive parenting behaviors (β = 0.206, z = 2.397, p = .017), and observed supportive coparenting (β = 0.256, z = 3.370, p = .001) at 3 M were positively and significantly related to subsequent analogous behavior at 9 M. Mothers’ positive parenting at 3 M was positively related to supportive coparenting at 9 M, β = 0.184, z = 2.288, p = .022, but the same association was not significant for fathers, β = 0.160, z = 1.879, p = .060. Observed supportive coparenting at 3 M was significantly associated with higher fathers’ positive parenting at 9 M, β = 0.195, z = 2.513, p = .012, but not mothers’ positive parenting at 9 M, β = 0.077, z = 0.973, p = .330. Constraining these two paths to be equal did not significantly change the model fit, Δχ2(1) = 1.459, p = .227. Thus, supportive coparenting at 3 M had similar associations with mothers’ and fathers’ positive parenting behaviors at 9 M, βMother = 0.131, βFather = 0.138, z = 2.303, p = .012.

Figure 1. The model of supportive coparenting and positive parenting. Note. 3M/9M = three/nine months. Standardized estimates are reported. Non-significant paths are not shown. Dashed paths have p-values between .05 and .10. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .01.

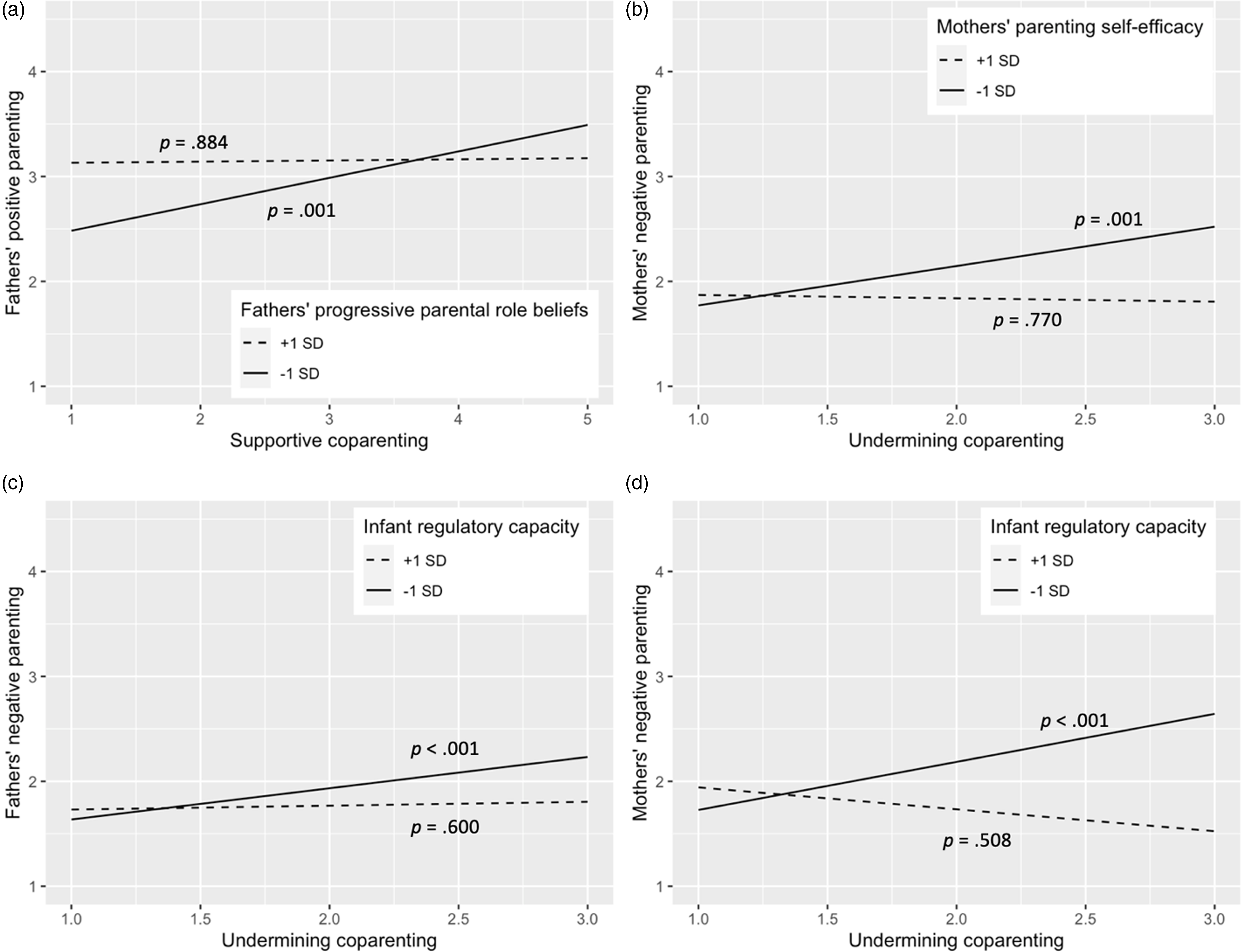

Next, we tested the potential moderators. Only one significant moderator was identified. Fathers’ progressive role beliefs moderated the associations between supportive coparenting at 3 M and fathers’ positive parenting behavior at 9 M, β = −0.171, z = −2.353, p = .019. Simple slopes analysis (see Figure 2a) showed that when fathers held more progressive parental role beliefs, the association between supportive coparenting and fathers’ positive parenting was not significant, β = 0.015, z = 0.145, p = .884. However, when fathers held less progressive parental role beliefs, the positive link between supportive coparenting and fathers’ positive parenting was strengthened, β = 0.351, z = 3.433, p = .001.

Figure 2. The moderating effects of progressive parental role beliefs, parenting self-efficacy, and infant temperament.

Undermining coparenting and negative parenting

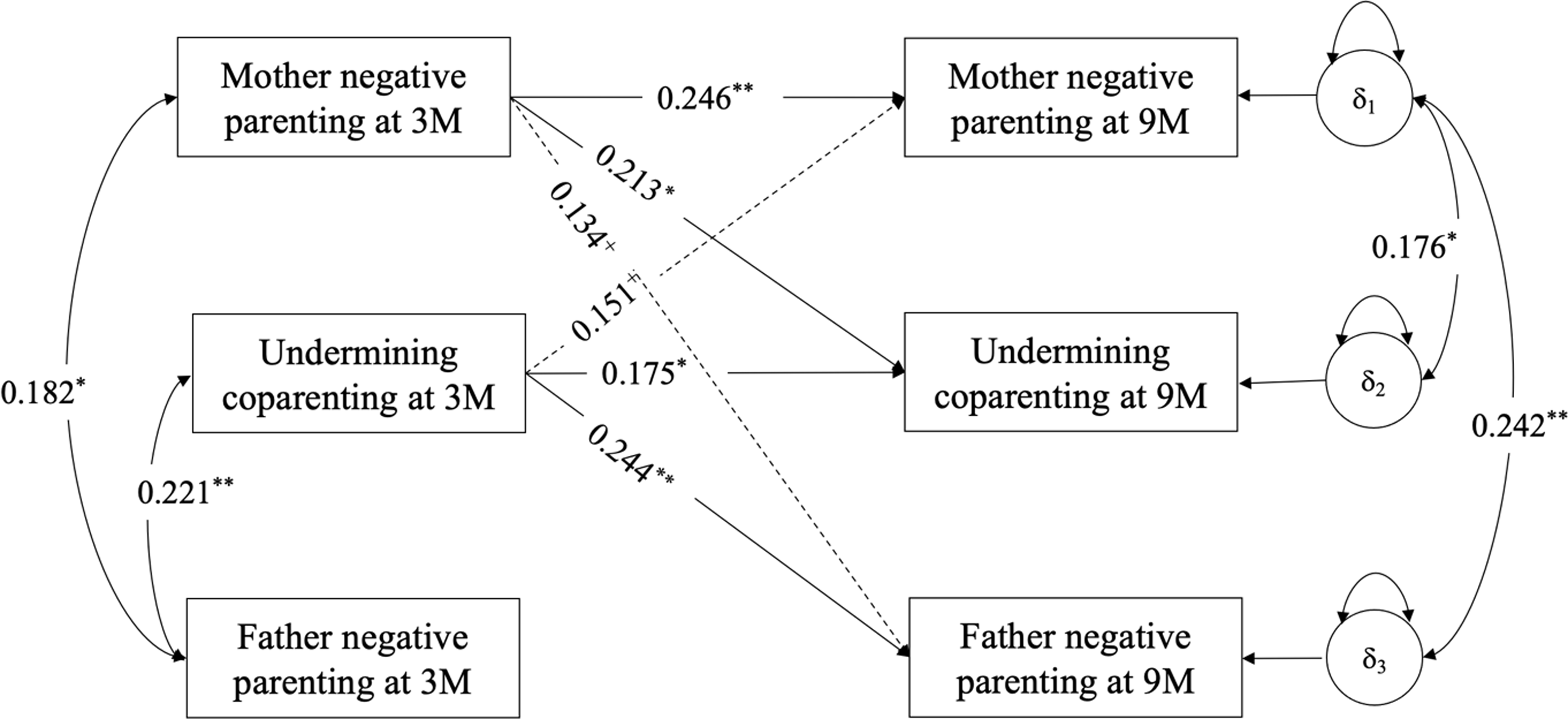

Another cross-lagged panel model was used to examine the associations between undermining coparenting and parents’ negative parenting behavior (see Figure 3 and Supplemental Table J). Mothers’ negative parenting at 3 M predicted mothers’ negative parenting at 9 M, β = 0.246, z = 3.109, p = .002. This association was not found for fathers’ negative parenting, p > .05. Undermining coparenting at 3 M was positively associated with undermining coparenting at 9 M, β = 0.175, z = 2.163, p = .031. Mothers’ negative parenting at 3 M was positively associated with observed undermining coparenting at 9 M, β = 0.213, z = 2.726, p = .006. Fathers’ negative parenting at 3 M was not significantly associated with observed undermining coparenting at 9 M, β = −0.055, z = −0.684, p = .494. The association between undermining coparenting and mothers’ negative parenting was not significant, β = 0.151, z = 1.848, p = .065, and the link between undermining coparenting and fathers’ negative parenting was significant, β = 0.244, z = 3.009, p = .003. Constraining the cross-lagged links between undermining coparenting and negative parenting to be equal for mothers and fathers did not change the model fit, Δχ2(1) = 0.060, p = .806. Therefore, undermining coparenting at 3 M was similarly related to mothers’ and fathers’ negative parenting behavior at 9 M, βMother = 0.166, βFather = 0.236, z = 3.209, p = .001.

Figure 3. The model of undermining coparenting and negative parenting. Note. 3M/9M = three/nine months. Standardized estimates are reported. Non-significant paths are not shown. Dashed paths have p-values between .05 and .10. *p < .05, **p < .01.

Among all the potential moderators tested, two statistically significant moderation effects were identified. Mothers’ parenting self-efficacy moderated the link between undermining coparenting at 3 M and mothers’ negative parenting at 9 M, β = −0.228, z = −2.798, p = .005 (see Figure 2b). When mothers had high parenting self-efficacy, observed undermining coparenting at 3 M was not significantly associated with mothers’ negative parenting at 9 M, β = −0.031, z = −0.292, p = .770. In contrast, when mothers had low parenting self-efficacy, observed undermining coparenting at 3 M was positively associated with mothers’ negative parenting at 9 M, β = 0.367, z = 3.423, p = .001.

Infant regulatory capacity moderated the link between undermining coparenting at 3 M and fathers’ negative parenting at 9 M, β = −0.176, z = −2.097, p = .036 (see Figure 2c) and the link between undermining coparenting at 3 M and mothers’ negative parenting at 9 M, β = −0.319, z = −3.999, p < .001 (see Figure 2d). When infants had high regulatory capacity, undermining coparenting was not significantly related to fathers’ (β = 0.051, z = 0.413, p = .680) nor mothers’ (β = −0.204, z = −1.707, p = .088) negative parenting. However, when infants had low regulatory capacity, undermining coparenting was positively related to fathers’ (β = 0.408, z = 3.671, p < .001) and mothers’ (β = 0.445, z = 4.188, p < .001) negative parenting behavior.

Discussion

The current study aimed to answer one central question: Whose parenting behavior is most susceptible to coparenting relationships? The current study expanded the father vulnerability/susceptibility hypothesis from a binary gender perspective to a focus on variability in mothers’ and fathers’ dependence on relational contexts. Findings revealed that the associations between both positive and negative aspects of coparenting and parenting were not significantly stronger for fathers than for mothers. Thus, the results did not support fathers’ greater susceptibility to coparenting solely on the basis of gender or role nor fathers’ greater vulnerability only to negative aspects of interparental relationships. However, we did find that different factors contributed to mothers’ and fathers’ susceptibility to coparenting relationships. Specifically, for fathers with less progressive parental role beliefs, supportive coparenting was more strongly associated with positive fathering behavior; for mothers with lower parenting self-efficacy, undermining coparenting was more strongly related to negative mothering behavior; and for parents with infants lower in regulatory capacity (mothers and fathers alike), undermining coparenting was more strongly associated with negative parenting behavior.

Considering mothers and fathers together, coparenting quality was significantly associated with new parents’ parenting quality. As expected, coparenting relationships serve as an important relational context for the development of individual parenting competence, such that supportive coparenting was associated with higher positive parenting behavior, whereas undermining coparenting was associated with higher negative parenting behavior. Moreover, these associations were not significantly stronger for fathers than for mothers, which did not support our expectation drawn from the father susceptibility/vulnerability hypothesis. These results are not necessarily surprising, however, given that participants in the current study were dual-earner couples with relatively stable relationships and relatively ample socioeconomic resources. Fathers in these families may have more support and resources for carrying out their parenting responsibilities than fathers from disadvantaged backgrounds, which may make parenting competence less heavily dependent on their relationships with mothers (Wang & Schoppe-Sullivan, Reference Wang and Schoppe-Sullivan2023). In fact, previous studies have revealed mixed findings on fathers’ and mothers’ differential vulnerability to interparental relationships (Cummings et al., Reference Cummings, Merrilees and George2010), which implies that parents’ susceptibility to the interparental relationship is not – at least not solely – determined by their gender or sex. There may be considerable individual differences in mothers’ and fathers’ susceptibility to coparenting quality, which likely rendered the small differences between mothers and fathers observed in the current study nonsignificant. The current study supported this possibility by revealing factors beyond gender that contribute to parents’ susceptibility.

As expected, mothers’ parental role beliefs did not appear to influence their susceptibility to the coparenting relationship. This finding may indicate that mothers feel obliged to fulfill their roles as parents, regardless of how they view the parenting responsibilities of fathers. In contrast, fathers’ progressive parental role beliefs moderated the link between supportive coparenting and their positive parenting behaviors. Fathers with more progressive parental role beliefs appeared less affected by the coparenting relationship compared to fathers with less progressive parental role beliefs. Fathers with progressive parental role beliefs expect themselves to be involved in parenting as much as mothers do. They may have clearer definitions of their roles and responsibilities as parents and a lower susceptibility to the relational context. Their parenting behaviors, as a result, are less likely contingent on mothers’ encouragement and facilitation. In contrast, fathers with more traditional parental or gender role beliefs expect women to carry more parenting responsibilities and tend to be less involved in parenting infants (Wang & Cheung, Reference Wang and Cheung2023), which may inflate their need for support in the relational context to engage in parenting and practice parenting skills. They may develop better parenting competence if they are supported and facilitated by mothers but may practice their parenting skills less often if mothers offer limited encouragement. It is important to note that participants in the current study were dual-earner couples, and these parents tend to have more progressive parental role beliefs than traditional single-earner couples (Buckley & Schoppe-Sullivan, Reference Buckley and Schoppe-Sullivan2010). Thus, it is possible that fathers’ susceptibility to coparenting in families with more traditional roles would be more pronounced.

Mothers’ parenting self-efficacy interacted with undermining coparenting in relation to their negative parenting behavior. When mothers had low parenting self-efficacy, they appeared to become more vulnerable to the adverse impact of undermining coparenting. Poor parenting self-efficacy is associated with lower parenting competence and greater maternal mental health issues (e.g., postpartum depression, parenting anxiety, and parenting stress; Albanese et al., Reference Albanese, Russo and Geller2019). A lack of perceived efficacy in parenting not only creates stress and distress in mothers directly but also interacts with poor coparenting relationships to compromise mothers’ parental adjustment. For example, Schoppe-Sullivan et al., (Reference Schoppe-Sullivan, Settle, Lee and Kamp Dush2016) found that mothers’ (but not fathers’) low parenting self-efficacy strengthened the association between lower reported coparenting support and greater parenting stress. The elevated distress caused by low parenting self-efficacy and exacerbated by undermining coparenting relationships may make mothers prone to employ negative parenting behavior. Note that the current study did not specify who is being undermined in behavioral coparenting coding, and it is possible that undermining coparenting behavior is adopted by only one parent or both. The interaction effect between parenting self-efficacy and undermining coparenting is likely to exist regardless of who is being undermined. Mothers may experience elevated stress and distress and adopt negative parenting behavior when mothers’ lack of confidence in their own parenting is accompanied by distrust of their partners’ parenting as well as when mothers’ lack of confidence in parenting is further reinforced by their partners’ undermining. Different from our expectations, fathers’ low parenting self-efficacy did not appear to render them more vulnerable to negative coparenting relationships. Fathers on average have lower levels of parenting self-efficacy than mothers in children’s infancy (Solmeyer & Feinberg, Reference Solmeyer and Feinberg2011), and societal expectations for fathers of infants tend to be more relaxed (Cummings et al., Reference Cummings, Merrilees and George2010). It is possible that low parenting self-efficacy among first-time fathers in the postpartum period may not be especially damaging to fathers’ adjustment and may be perceived as acceptable for fathers.

Infant temperament showed similar moderating effects on the associations between coparenting and both mothers’ and fathers’ parenting behavior. In families with infants who were low in regulatory capacity, undermining coparenting was positively associated with negative parenting behaviors, whereas this association was non-significant in families with infants who were high in regulatory capacity. Difficult infant temperament (Padilla et al., Reference Padilla, Hines and Ryan2020) and undermining coparenting (Zvara et al., Reference Zvara, Altenburger, Lang and Schoppe-Sullivan2019) can directly elicit more negative parenting behaviors. The absence of one negative factor may buffer the adverse impact of the other factor, whereas the co-presence of the two negative factors may enhance the roles of each by facilitating the spillover process or by impairing parents’ psychological adjustment and increasing their dependence on the relational context (Andreadakis et al., Reference Andreadakis, Laurin, Joussemet and Mageau2020; Solmeyer & Feinberg, Reference Solmeyer and Feinberg2011). Given that the coparenting relationship is more modifiable relative to infant temperament, the reduction of undermining coparenting warrants special attention for new parents, especially when parents have infants whose emotions and behaviors are not easily regulated. Additionally, in the current study, mothers and fathers displayed similar responses to the interaction of infant temperament with coparenting behavior. Mothers need support, not undermining, from their coparenting relationships as much as fathers do in caring for temperamentally challenging infants.

It is worth noting that in the current study, the moderation effects were examined individually to ensure adequate power of analyses. Although both mothers’ parenting self-efficacy and infant regulatory capacity moderated the associations between undermining coparenting at three months and mothers’ negative parenting at nine months, the current study did not examine the three-way interactions among them. Testing higher-order interactions was beyond the scope of the current study. Nonetheless, it is likely that stress and distress stemming from the parent (low parenting self-efficacy), infant (low regulatory capacity), and relationships (high undermining coparenting) could strengthen the adverse impact of one another on parenting behavior. Future studies should further explore these complex interactions among multiple individuals and relationships within families.

The current study substantiated links from coparenting to fathers’ parenting behavior 6 months later but did not substantiate links from fathers’ parenting to coparenting, which differs from the results of previous studies (Bernier et al., Reference Bernier, Cyr, Matte-Gagné and Tarabulsy2023; Bureau et al., Reference Bureau, Deneault, Yurkowski, Martin, Quan, Sezlik and Guérin-Marion2021; Jacobvitz et al., Reference Jacobvitz, Aviles, Aquino, Tian, Zhang and Hazen2022). Compared to previous studies, one significant strength of the current study was the inclusion of repeated measures of parenting and coparenting, which allowed a more rigorous examination of directional associations. The longitudinal associations between parenting and coparenting should be considered together with their concurrent associations, such that supportive coparenting was positively related to fathers’ positive parenting concurrently at both three and nine months postpartum and undermining coparenting was positively related to fathers’ negative parenting concurrently at three months postpartum. Perhaps fathers’ parenting quality takes more time to stabilize, given that fathers spend less time with infants than mothers in the early months; thus, we observed significant concurrent associations but not longitudinal associations from parenting to coparenting for fathers. Future studies are required to test this speculation. Even so, the non-significant findings from fathers’ parenting to coparenting ought not be interpreted as evidence for the absence of associations and should be interpreted with caution.

Moreover, the inclusion of positive and negative aspects of coparenting and parenting behavior contributes to our knowledge about family processes. The results show that fathers with less progressive parental role beliefs benefit from supportive coparenting, whereas mothers with low parenting self-efficacy and parents with infants low in regulatory capacity appear particularly vulnerable to undermining coparenting. These results imply that positive and negative aspects of the coparenting relationship are not on a single continuum (Altenburger et al., Reference Altenburger, Schoppe-Sullivan, Lang, Bower and Kamp Dush2014; Van Egeren & Hawkins, Reference Van Egeren and Hawkins2004) and may follow different paths in shaping parents’ functioning and that the development of positive and negative parenting behaviors may have distinct antecedents. The spillover of positive and negative emotions and behaviors in family subsystems is not in exact opposition to one other. Thus, separately measuring positive and negative (or multiple) aspects of coparenting and parenting behaviors may be desirable for disentangling the underlying mechanisms of family functioning.

Limitations and future directions

Despite its strengths and contributions, the current study is not without limitations. First, participating families in the current study were mostly White, relatively affluent, and of relatively high functioning, which limits the generalizability of the current findings. Future studies should examine fathers’ and mothers’ susceptibility to the coparenting relationship with diverse and more representative samples. Second, the observations of parenting and coparenting used in this study were relatively brief and did not elicit a large range of negative behaviors. Researchers should develop and employ parent-child dyadic and triadic interaction tasks that are better suited to elicit a wider range of parenting and coparenting behaviors and observe parenting and coparenting across caregiving contexts (e.g., playing, feeding, teaching) and for longer periods of time. Third, in the context of appropriately reporting all the interaction effects tested in the current study, the number of interaction effects that reached statistical significance was modest, and the current study may have lacked enough power to detect small moderation effects. Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to confirm these moderation effects. Additionally, coparenting relationships and parenting behaviors are likely to develop or change during the transition to parenthood. However, with two waves of data, the current study could not examine the trajectories of changes or their associations. Future longitudinal studies with more waves of data are warranted.

The current study was also unable to consider that parents’ beliefs about parenting are likely to change after childbirth (Cowan et al., Reference Cowan, Cowan, Heming, Garrett, Coysh, Curtis-Boles and Boles1985), and future studies could explore how postnatal parental beliefs shape the parents’ susceptibility to coparenting relationships. Also, from the family systems perspective, parents’ beliefs and perceptions may not influence family dynamics independently of one another. The congruencies and discrepancies in parents’ beliefs and perceptions may also have implications for family functioning (McHale et al., Reference McHale, Kuersten-Hogan, Lauretti and Rasmussen2000; Schoppe-Sullivan et al., Reference Schoppe-Sullivan, Wang, Yang, Kim, Zhang and Yoon2023), and how the match and mismatch of parental role beliefs or perceptions of coparenting relationship quality directly and interactively influence parenting behavior should be considered in future research. Finally, the current study was unable to fully consider the richness of the coparenting construct by including dimensions beyond support and undermining. Knowledge regarding parents’ susceptibility to coparenting and the coparenting relationship would be enhanced by more in-depth qualitative or quantitative examinations focused on multiple components of coparenting and parenting behavior and perceptions.

Implications

The current study highlights the spillover effect from the coparenting subsystem to the parent-child subsystems, suggesting that promoting higher-quality coparenting relationships may serve as a good starting point for enhancing family functioning and child wellbeing, consistent with the established benefits of several coparenting-focused programs (Ammerman et al., Reference Ammerman, Peugh, Teeters, Sakuma, Jones, Hostetler, Van Ginkel and Feinberg2022; Feinberg et al., Reference Feinberg, Jones, Hostetler, Roettger, Paul and Ehrenthal2016). Beyond affirming the importance of a focus on coparenting, results of the current study suggest that in designing intervention programs, it is important to consider parents’ susceptibility to coparenting dynamics and to avoid the implicit or explicit assumption that individual differences in susceptibility are limited to parent gender or role. The consideration of parents’ levels of susceptibility may benefit programs targeting individual parenting competence. For example, should the results of the current study be replicated, promoting supportive coparenting behavior could be prioritized to facilitate positive spillover if fathers endorse traditional parental role beliefs, whereas reducing undermining coparenting behavior could be emphasized to mitigate negative spillover if mothers have low parenting self-efficacy or infants’ emotions and behaviors are challenging to regulate. Moreover, fathers may benefit from prenatal programs targeting parental beliefs and mothers may benefit from postnatal interventions focusing on building parenting self-efficacy. Additionally, practitioners could encourage the joint participation of parents with high susceptibility, given that this may offer extra benefits to coparenting than parents attending separately (Cowan & Cowan, Reference Cowan and Cowan2019). In sum, the more nuanced perspective on associations from coparenting to parenting supported by the results of this investigation holds promise for enhancing researchers’ and practitioners’ focus on parents’ strengths in addition to their vulnerabilities, and for advancing the view of parents’ differences in susceptibility to the relational context of coparenting beyond a primary focus on binary gender distinctions, consistent with maternal and paternal role convergence in many 21st century families.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579425000409.

Data availability statement

Data and code are available by contacting the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Claire M. Kamp Dush’s invaluable contributions to the design and execution of the New Parents Project.

Funding statement

The New Parents Project was funded by the National Science Foundation (CAREER 0746548, Schoppe-Sullivan), with additional support from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD; 1K01HD056238, Kamp Dush), and The Ohio State University’s Institute for Population Research (NICHD; P2CHD058484).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.