1. Introduction: background, voicing in Old English

In Old English (OE) the phonetically voiced ([v ð z ɣ]) and voiceless fricatives ([f θ s x]) were in complementary distribution (cf. Kristensson Reference Kristensson, Laing and Williamson1994; Nielsen Reference Nielsen, Laing and Williamson1994; Lass Reference Lass1997; Fulk Reference Fulk2001; Minkova Reference Minkova2011, Reference Minkova2014; Thurber Reference Thurber2011; Laing & Lass Reference Laing and Lass2019 on the Middle English (ME) reflexes). A remnant of their allophonic distribution in OE is provided by Modern English (MoE) lexically conditioned alternations in the singular vs plural of some nouns (wolf/wolves, house/houses), etymologically related noun–verb pairs (house /s/ vs house /z/, sooth vs soothe), noun–adjective pairs (south vs southern) and a few others (life vs livelihood, alive), as well as some more obscured ones (day vs dawn, draw vs draught, owe vs ought). Some MoE words predictably have voiceless fricatives (offer, moth, kiss, wish from OE geminates).

We discuss the structure of (partial) geminates (cyssan ‘kiss’, sceaft ‘shaft’) using the insights of laryngeal realism (Honeybone Reference Honeybone, van Oostendorp and van de Weijer2005a, Reference Honeybone, Nevalainen and Traugott2012; Iverson & Salmons Reference Iverson and Salmons2006; with similar ideas found in Iverson & Salmons Reference Iverson and Salmons1995; Avery & Idsardi Reference Avery, Idsardi and Hall2001; Jessen & Ringen Reference Jessen and Ringen2002; Iverson & Ahn Reference Iverson and Ahn2007; and many others, and as early as Sievers Reference Sievers1876), laryngeal dimensions (and their completions) and enhancement (known as Vaux’s Law; see Vaux Reference Vaux1998; Avery & Idsardi Reference Avery, Idsardi and Hall2001). The obstruents of OE are unmarked (lenis) vs marked (fortis), formally shown with ‘h’, ‘H’, [spread] or glottal width (GW), carrying (considerably) different assumptions across frameworks, pace Hogg (Reference Hogg2011, §2.53), Minkova (Reference Minkova2014: 27), who present OE as a voicing language.Footnote 1 The feature GW distinguishes fortes from lenes and has/had a range of (combinations of) phonetic realisations both on the consonant and the preceding/following vowel/sonorant. In this manner, GW is less restrictive than ‘h’, which is visually more likely to imply aspiration only. We do not present new data; we argue for a new perspective. Although OE is well behaved with respect to West Germanic (Salmons Reference Salmons, Putnam and Page2020), some of the standardly held assumptions (on assimilation, for example, discussed by Spaargaren Reference Spaargaren2009) will be revisited.

OE has no examples for regressive voicing assimilation monomorphemically, across inflectional or derivational suffixes or post‑lexically. The past tense of mētan ‘meet’ is mētte, not **mēdde (mēt+de), as would be expected in a voicing language. Derived swićdōm ‘fraud’, lēohtbǣre ‘luminous’, rādscipe ‘discretion’ are never found as **swicgdōm [dʒ], **lēogdbǣre/lēhgdbǣre [ɣd], **rātscipe [t] (cf. Fulk Reference Fulk2002: 2.1). Assimilation is also missing post‑lexically: eft byreð, **efd byreð ‘bear’s back’. This shows that voicing in OE obstruents was a low‑level, gradient, mundane phonetic fact contingent on the availability of a voice‑friendly environment (Iverson & Salmons Reference Iverson and Salmons2003; Salmons Reference Salmons, Putnam and Page2020), i.e. by being surrounded by passively voiced obstruents or spontaneously voiced sonorants (or a combination of these), similarly to the modern reference varieties of English (e.g. Cruttenden Reference Cruttenden2014: 9.2.1).

2. Contrast and phonological positions in OE

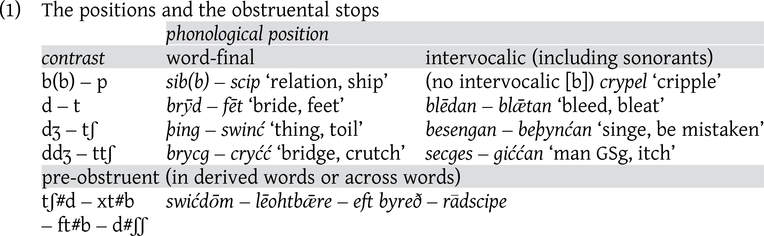

There are phonologically strong (word‑initial, pre‑tonic and sometimes post‑consonantal prevocalic) and weak positions (subsuming the rest of the positions; cf. Scheer Reference Scheer2004). The strong position is the most salient one phonetically, typically exemplifying all the contrasts found in a language. Whatever feature was responsible for the differentiation of 〈b〉 and 〈p〉, 〈d〉 and 〈t〉, 〈g〉 and 〈c〉, 〈cg〉 [ɟ/dʒ] and 〈ć〉 [c/tʃ], this phonological feature had a salient enough phonetic correlation to cue the laryngeal contrasts in phonologically weak positions; see (1), which is not an exhaustive list of the positions in which (obstruental) stops are found.

There is no lenition in the weak positions: no regular categorical devoicing word‑finally or voicing intervocalically (marked orthographically as such). The word‑initial position remains ideal for cuing the differences. OE is unlike modern Danish, where only the word‑initial position can cue the laryngeal differences. In the weak positions, Danish stops are all voiceless for all places of articulation; cf. Haugen (Reference Haugen1982: 81), Page (Reference Page1997): tyk ‘thick’, lække ‘leak’ and tyg ‘chew’, lægge ‘lay’ all have [![]() ß/k]). We do not encounter this in OE, with blǣtan continued as bleat still in contrast with bleed. (1) shows that the laryngeal contrast in the stops was maintained even in pre‑obstruent position, similarly to the reference accents of MoE, cf. newsfeed with /z0fGW/ [z̥f] (**/sGWfGW/), backbone /kGWb0/ (**/

ß/k]). We do not encounter this in OE, with blǣtan continued as bleat still in contrast with bleed. (1) shows that the laryngeal contrast in the stops was maintained even in pre‑obstruent position, similarly to the reference accents of MoE, cf. newsfeed with /z0fGW/ [z̥f] (**/sGWfGW/), backbone /kGWb0/ (**/![]() 0b0/). The OE system of oppositions in the stops has been constant in both the strong and the weak positions (excepting flapping in some modern varieties). The spelling itself is no evidence, but the (written) absence of regressive assimilation across morpheme/word boundaries is indicative of an ‘aspiration’ language.

0b0/). The OE system of oppositions in the stops has been constant in both the strong and the weak positions (excepting flapping in some modern varieties). The spelling itself is no evidence, but the (written) absence of regressive assimilation across morpheme/word boundaries is indicative of an ‘aspiration’ language.

3. OE lenes

The allomorphy of the past tense suffix /d0/ of the first class of weak verbs is straightforward: [d] after sonorants, voiced stops and singleton fricatives (e.g. *hīeridǣ ‘hear, Pt’ > hīerde; *mæŋ![]() idǣ ‘mix, Pt’ > *mændʒidǣ > *mendʒdæ >

idǣ ‘mix, Pt’ > *mændʒidǣ > *mendʒdæ >

![]() emen

emen![]() de; *‑līeβidǣ ‘believe, Pt’ > belīefde), [t] after voiceless stops and geminated fricatives (*mœ̄tidǣ ‘meet, Pt’ > West Saxon OE mētte, *kœ̄pidǣ ‘keep, Pt’ > *kœ̄pdæ > West Saxon OE cēpte; *pyffidǣ ‘breathe out, Pt’ > *pyffdæ > pyfte).

de; *‑līeβidǣ ‘believe, Pt’ > belīefde), [t] after voiceless stops and geminated fricatives (*mœ̄tidǣ ‘meet, Pt’ > West Saxon OE mētte, *kœ̄pidǣ ‘keep, Pt’ > *kœ̄pdæ > West Saxon OE cēpte; *pyffidǣ ‘breathe out, Pt’ > *pyffdæ > pyfte).

Orthographic 〈t〉 shows a phonetically voiceless sound. Its phonological representation is a different matter. 〈t〉, however, does not directly translate into /tGW/. There is no need to assume phonological assimilation: /d0/ was heard as [t] (and spelt accordingly, a case of allophonic spelling). Examples for phonemic spelling such as gegrippde ‘he gripped’, slēpde ‘he slept’, slēpdon ‘they slept’, genēoclećde ‘he approached’, ræfsde ‘he seized’ (Hogg Reference Hogg and Fulk2011: §7.90) can also be found, showing that a spelling tradition showing (underlying) /d0/ could well have evolved.

After singleton fricatives, past tense is [d], e.g. rǣsde, **rǣste, from rǣsan ‘rush’. In a traditional account employing serialism the voicing of fricatives as a synchronic rule is ordered before syncopation (*rǣsidǣ > *rǣzidǣ > *rǣzdǣ), ensuring [zd] in recorded rǣsde. In our account, there is no ‘voicing of fricatives’. The lenis fricative in pre‑OE *rǣsidǣ was always phonetically passively voiced. In rǣsde perseverative voicing affects the entire sequence of the lenis singleton fricative and following lenis stop. The fricative is phonetically voiced not because [d] is phonologically marked for voice, but because both are found in a voice‑friendly environment. If [d] was phonologically voiced (/dGT/), we would expect it to voice voiceless stops and voiceless geminate fricatives, something never found: *mētidæ > **mēdde, *kyssidæ > **cysde, similarly to **swicgdōm; cf. Spaargaren (Reference Spaargaren2009) for a similar claim.

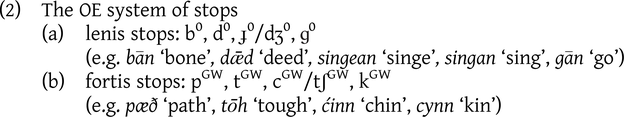

In Avery & Idsardi’s (Reference Avery, Idsardi and Hall2001) model GW is phonetically completed as [spread] or [constricted]. GT is completed as [slack] or [stiff]. These dimensions can be phonological or can later be added (non‑contrastively) as derivations become more phonetic (Iverson & Salmons Reference Iverson and Salmons2003). MoE uses [spread] in word‑initial position, as well as inside words before stressed vowels (tin vs din, atop vs adopt), word‑finally a host of phonetic solutions can be used: clipping of vowels/sonorants before fortis obstruents and/or pre‑glottalisation, something not found before the lenis obstruents (bit vs bid), which are phonetically voiceless word‑finally (cf. Lisker Reference Lisker1986; Kirby Reference Kirby2010; Farrington Reference Farrington2018; Iverson & Salmons Reference Iverson, Salmons, van Oostendorp, Ewen, Hume and Rice2011). What OE was exactly like phonetically must remain conjectural. What we do know based on the available data is that it was phonologically a GW language. See (2) for the list of obstruental stops (cf. Starčević Reference Starčević2024).

Intervocalic (perseverative/passive) voicing of /tGW/ in slitol (potentially merging it with the 〈d〉 of slidor) or word‑final weakening of /tGW/ in slāt (merging it with slād) was prevented by GW. The question of why GW was maintained in the weak positions cannot be answered in phonological terms (the phonetic cues, however, were robust enough to maintain the underlying opposition). We can, however, speculate on what the pronunciation of intervocalic /d0/ was in slidor: it is likely to have been passively voiced. The pronunciation of 〈t〉 in slitol can be given negatively: it cannot have been [d]. Its pronunciation can only be conjectural: [th], [ˀt], [ˀth] (or a combination of these and other phonetic cues), but (probably) not [ht]. An important theoretical point emerges: while phonology is categorical, phonetics is not. The laryngeally unmarked alveolar stop in standard German Dieb ‘thief’ is voiceless, in Made ‘maggot’ it is variably voiced, which is expected given that German is an ‘aspiration’ language (cf. Beckman et al. Reference Beckman, Jessen and Ringen2013). The contrast, however, with fortis stops is maintained: tief ‘deep’ (where /tGW/ is heavily aspirated), Matte ‘mat’ (where /tGW/ is voiceless (and variably aspirated), showing the absence of passive voicing). Phonetics may thus be malleable (cf. Beckman et al. Reference Beckman, Jessen and Ringen2013), but phonology is not.

4. OE geminate stops

All lenis stops existed as geminates: e.g. swebban ‘put to sleep’, tredde ‘press (for wine)’, brycg ‘bridge’, frogga ‘frog’. These were contrasted with voiceless geminates: clyppan ‘clasp’, sittan ‘sit’, cnyććan ‘tie’, docca ‘muscle’. The null hypothesis is that geminate voiced stops are what they appear to be: a sequence of two lenis stops ([swebbɑn]).

The representation of voiceless geminates must follow straightforwardly: as they do not show intervocalic neutralisation with lenis geminates, GW must be present in them: e.g. clyppan /pGWpGW/. The question is whether one wants to admit that both members of a geminate were marked for GW. We are agnostic about whether such doubly marked geminates are necessary or whether they follow straightforwardly from OE. Spaargaren (Reference Spaargaren2009: §3.2.3) is not the only analyst who considers cēpte to show progressive assimilation of GW from /pGW/ to /d0/, yielding /pGWtGW/ phonologically (Iverson & Salmons Reference Iverson and Salmons1999 for MoE). What the phonetic rendition of /pGWtGW/ may have been must remain conjectural given the absence of phonological proof for a possible post‑aspirated /tGW/ following a fortis consonant in an unstressed syllable (?[ptʰe]). Our contention is that the cluster 〈pt〉 was only specified for GW on /pGW/ to prevent it from undergoing passive voicing (**[bd]), from which the phonetic voicelessness of /d0/ follows straightforwardly in this non-voice‑friendly environment. We do not need to posit that GW spread progressively making a lenis segment phonologically fortis just to ensure that a lenis obstruent should sound voiceless. The /r/ in MoE trill, for example, is phonetically voiceless, but would not be marked for GW phonologically (no analysis is likely to claim that /r/ acquires GW). Importantly, the evidence of the hypothetical /tGW/ in cēpte is textual, not phonological. We claim that /d0/ does not become /tGW/, although it is phonetically [t]. Absence of perseverative voicing depends on GW. In cēpte GW in /pGW/ is sufficient for blocking voicing.Footnote 2

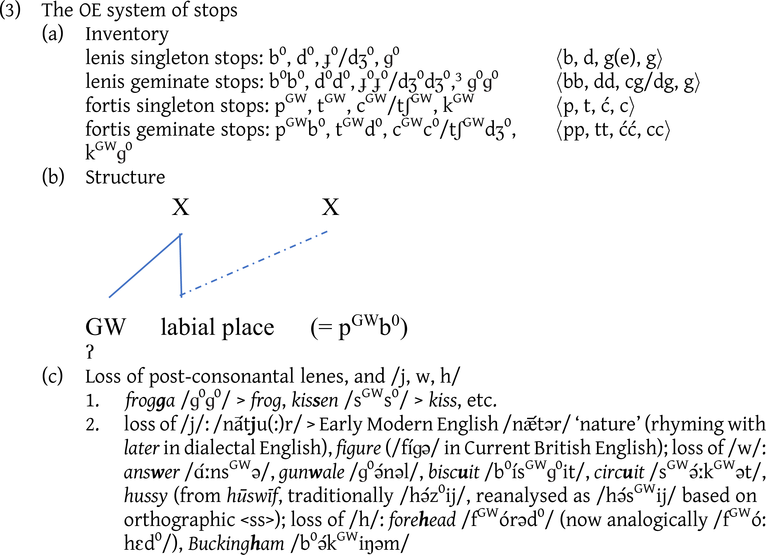

A similar structure to /pGWd0/ is found in voiceless geminate stops: they are a sequence of a fortis stop followed by a lenis stop: clyppan /pGWb0/, sittan /tGWd0/, etc. The structure of voiceless geminate stops does not ‘complicate’ OE phonology: they are composed of segments that are part of OE phonology. This produces the inventory of OE obstruental stops in (3a). The structure of OE fortis geminate stops follows from the general assumptions on geminates (Hayes Reference Hayes1986; Schein & Steriade Reference Schein and Steriade1986; Kirchner Reference Kirchner2000; etc.), shown in (3b). We can see that the second (lenis) member of such geminates was lost in ME degemination identically to post‑consonantal (non‑liquid) sonorants: melodically non‑complex segments were deleted in unstressed syllables, shown in (3c).

OE fortis geminate stops are left‑headed geminates, with GW linking to the left leg. As justifying the formal structure of the geminate is not our primary concern, the structure shown above is somewhat informal, yet the melody of the first consonant is understood to spread phonetically to the second one on account of ME degemination that deleted the second (structurally empty) member of such geminates (see below and section 11). We find justification for the anchor point of aspiration in (3b) in Iverson & Salmons’ (Reference Iverson and Salmons1995) claim that the phonetic implementation of [spread] takes longer than one segment to allow the vocal folds to settle back into voicing, which explains why there is no aspiration after s+stop clusters (as in spin, stick, skill). It also explains why [p] in spin, for example, can only be lenis (/b0/). If GW were to spread over two positions, there should be aspiration after the second consonantal position (**[spGWin]), too, resulting in a partly devoiced vowel (Kim Reference Kim1970: 114; Iverson & Salmons Reference Iverson and Salmons1995). The question arises why a doubly linked GW was/is not allowed. We must assume this is a phonological constraint inherited from Germanic, vaguely reminiscent of Grassmann’s law (Collinge Reference Collinge1985: 47). Historical changes offer a good testing ground for such hypotheses. ME degemination of /tGWd0/, /fGWf0/, /sGWs0/, etc. to /tGW/, /fGW/, /sGW/ shows that the geminates contained GW.

If ME degemination of long consonants (3c/1) and loss of post‑consonantal /j, w, h/ (3c/2) deletes the second minimally specified (non‑lateral/rhotic/nasal) segment, as well as the melodically empty right half of a geminate, then OE fortis geminates were affected in the same way on account of the lenis second half. Note the parallels between the two processes: both must have occurred after ME open syllable lengthening (cf. Minkova & Lefkowitz Reference Minkova and Lefkowitz2020) as there is no proof for lengthened vowels in words like either moth or gunwale (even granting the scarcity of lengthened high vowels). Additionally, the MoE short vowel in OE compounds like hūswīf shows that these were monomorphemic at the point of deletion, producing closed syllable shortening in ME (implying #huswif#), in addition to shortening of unstressed ī in ME before the great vowel shift (for comparison’s sake, the vowels before geminates were always short, excepting some before certain s+stop clusters). Short ŭ in hussy shows that deletion of /w/ must postdate the reanalysis of this word as monomorphemic as otherwise there would have been no phonological reason for shortening ū (ME [huːzəf] is phonotactically well‑formed) or deleting /w/ (there was no general deletion of /w/). The consonant clusters in ME (obscured) huswif and kisse(n) are treated identically: the (minimally specified) second half underwent deletion with no compensatory lengthening. The difference between /z0/ (/həz0ij/) and /sGW/ (/kisGW/) in MoE stems from their history in that the former originates in an OE lenis fricative, the latter in a fortis one.

5. The singleton fricatives of OE

The question of contrastive fricatives in OE is a truly vexed one. In Hogg (Reference Hogg2011), the voiced and voiceless fricatives are presented as being in complementary distribution. The once‑contrastive distribution of voiced and voiceless fricatives of West Germanic (see Moulton Reference Moulton1954, Reference Moulton, van Coetsem and Kufner1972) was disturbed by a series of changes. Essentially, contrast was lost; see (4). Campbell (Reference Campbell1959: 179) concludes that there was no distinction between OE voiceless and voiced fricatives, which can only be interpreted as ‘fricatives lacking any laryngeal specification’.

The changes in (4) contributed to the collapse in oppositions: in voice‑friendly environments, the fricatives are phonetically voiced (*/xGW/ was debuccalised and lost, probably through a stage with [ɦ]). Otherwise, they are phonetically voiceless. These changes, however, not only reduced the number of contrasts, but they also removed the sounds altogether from positions where they were in contrast with their closest congeners ([s], for example, could no longer be contrasted with [z]); cf. Blust Reference Blust2012. Additionally, unstressed prefixes do not ‘count’ for the intervocalic position (behíndan ‘behind’). The retention of [h], of course, shows absence of lenition (here sonorisation) in strong positions (cf. Davis & Cho Reference Davis and Cho2003; Honeybone Reference Honeybone2001, Reference Honeybone, Nevalainen and Traugott2012; Scheer Reference Scheer2004; among many others).

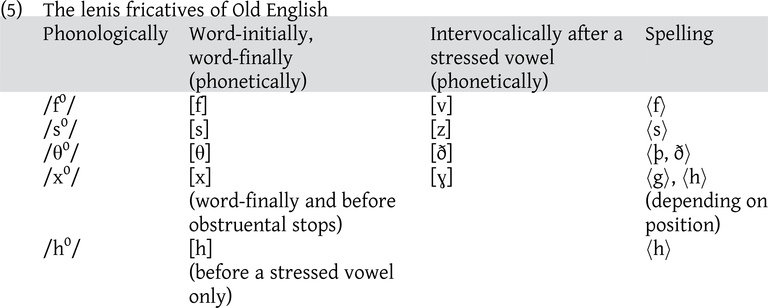

Speakers of post‑early OE (those speaking a language without intersonorant [x], and no opposition between [f] and [v/β]) had the oppositions in (5).

A few caveats are in order: (i) this distribution is assumed to be rooted in synchronic, as opposed to diachronic/panchronic, OE postdating the loss of /h/; (ii) 〈sc〉 only existed as a geminate [ʃʃ] < */sGW![]() 0/; (iii) the anterior labial fricative shows the collapse of a (very) early‑OE contrast between [f] and [v]/[β], e.g. wulf [f] vs wulfas [v], geab ?[v] ‘gave’ vs Albred [v]; the non‑labial anterior fricatives had no contrastive early‑OE pairs; (iv) the posterior fricatives show the reinterpretation of pre‑OE */xGW/ and */ɣ0/ as /x0/ with two allophones: [x] vs [ɣ];Footnote

4 (v) /h0/ has a defective distribution (this is a new phoneme synchronically, from */xGW/), found in a limited set of environments. The fricatives in (5) are phonologically lenis. This dispenses with the problematic term ‘voiceless’, which should be reserved for a phonetic description.

0/; (iii) the anterior labial fricative shows the collapse of a (very) early‑OE contrast between [f] and [v]/[β], e.g. wulf [f] vs wulfas [v], geab ?[v] ‘gave’ vs Albred [v]; the non‑labial anterior fricatives had no contrastive early‑OE pairs; (iv) the posterior fricatives show the reinterpretation of pre‑OE */xGW/ and */ɣ0/ as /x0/ with two allophones: [x] vs [ɣ];Footnote

4 (v) /h0/ has a defective distribution (this is a new phoneme synchronically, from */xGW/), found in a limited set of environments. The fricatives in (5) are phonologically lenis. This dispenses with the problematic term ‘voiceless’, which should be reserved for a phonetic description.

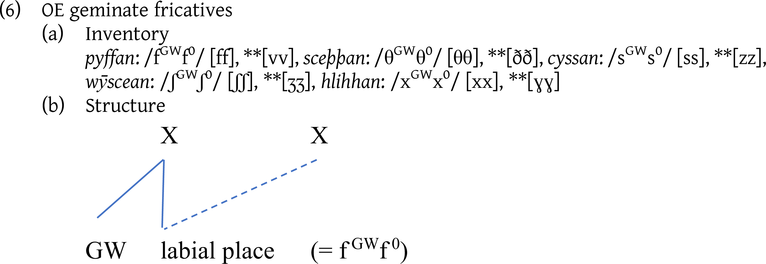

6. OE geminate fricatives

The question is why pyffan, cyssan, wӯscean have voiceless fricatives in OE. If they are construed as a sequence of two lenis fricatives, they should be voiced intervocalically, similarly to wisdom (< wīsdōm) and husband (< hūsbonda, an Old Norse word, but fitting the pattern; cf. Fulk Reference Fulk2002). Voiceless geminate fricatives behaved identically to voiceless geminate stops in barring passive voicing (e.g. cēpte /pGWd0/ [pt], **[bd], sittan /tGWd0/ [tt], **[dd]). Their inventory and structure of fortis geminate fricatives are shown in (6).

Our explanation for the absence of perseverative voicing lies in positing that GW was attached to the first leg of the geminate. The second leg has no GW attaching to it (with the rest of the features copied). Geminate fricatives thus do not undergo perseverative voicing. The similarities between /fGWf0/ [ff] 〈ff〉 and /pGWd0/ [pt] 〈pt〉, disregarding the differences in the melodic makeup, are structural: sequences of phonetically voiceless obstruent clusters in OE contain a fortis first member. The second/lenis leg of the geminate cannot be voiced given that it does not sit in a voice‑friendly environment. This does not show phonetic enhancement (GW) added to unmarked fricatives in accordance with Vaux’s Law (Vaux Reference Vaux1998) given that enhancement cannot create or destroy an underlying opposition ([zd] of wīsdōm never merges with [st] of wiston ‘knew’ through enhancement). GW is a structural feature of fortis geminates, part of their lexical phonological specification.

Sequences of two lenis fricatives in OE are missing: */β0β0/, */ð0ð0/ and */ɣ0ɣ0/ are found as stops in West Germanic (and OE): *waββja > webb ‘web’, *kuððo‑ > cudd ‘bag’, *muɣɣjo > mycge ‘midge’. If the traditional account sees an underlying singleton voiceless fricative as having no laryngeal features, and if such singleton fricatives are phonetically voiced in voiced environments, there is no reason why two such singleton unmarked fricatives should not have been voiced successively (e.g. Offa **[vv] vs ofer [v]). There is no formal mechanism that allows unmarked /f0/, but not /f0f0/, to be voiced in a voiced environment. Honeybone (Reference Honeybone, Carr, Durand and Ewen2005b) discusses segmental complexity and its relevance to the structure of geminates (and consonant clusters) as witnessed, for example, in Old High German affrico‑spirantisation. /tr/, as opposed to /pr/, was stronger by having coronality shared by both consonants (cf. MoE true vs German treu). /pr/, however, exemplified no such sharing of melody, giving /pfr/ (cf. OE prēon ‘needle’ vs Pfriem ‘awl’). Although place of articulation (and possibly manner) may create an environment disfavouring segmental decomplexification, the absence of spontaneous voicing in OE needs another explanation: if sharing was a barrier for voicing, there should be no phonetically voiced geminates, which is not the case (cf. webb, bedd, frogga). Additionally, it is not immediately evident how place (and possibly manner) may be able to impede spontaneous voicing given that voicing and place are controlled by two independent levels of organisation in a segment. The answer, at least for OE, must lie elsewhere.

Hogg (Reference Hogg2011: 277) views 〈ff〉, for example, to be [ff] on account of neither [f] being couched between voiced segments. ‘Voiceless’ in the explanation holds a phonological significance: fricatives are underlyingly voiceless and can only become voiced in voiced environments. In our account, fricatives are underlyingly neither voiced, nor voiceless: they are phonologically unmarked and are phonetically voiced or voiceless depending on whether passive voicing can affect them (and to what degree, see section 9).Footnote 5

7. Partial geminate‑like structures

OE had obstruental consonant clusters composed of a fricative marked for GW and a stop (in native words, there were no monomorphemic stop+stop clusters). These clusters were composed of [s/f/x] + [p/t/k] (note the */sGW![]() 0/ > /ʃGWʃ0/ change). Clusters involving s+stop were found initially, medially and finally, the rest only medially and finally. In traditional descriptions, a fricative in these clusters is considered voiceless as it is followed by a voiceless stop (as in westan ‘from the west’).

0/ > /ʃGWʃ0/ change). Clusters involving s+stop were found initially, medially and finally, the rest only medially and finally. In traditional descriptions, a fricative in these clusters is considered voiceless as it is followed by a voiceless stop (as in westan ‘from the west’).

These clusters never survive voiced into ME/MoE: lyft ‘air’, lyfte, lyfta ‘Pl’ **lyfde; hæft ‘bond’, hæfte ‘Dat’ **hæfde; cniht ‘servant’, cnihtes ‘Gen’ **cnigde/cnihde; æspe ‘aspen’ **æsbe; fōstre ‘nurse’ **fōsdre; etc. The structure of these partial geminates is identical to voiceless geminate stops and fricatives: the fricatives are fortis, the stops lenis, that is /sGWd0/ [st], for example. The inventory and the structure of partial geminates is shown in (7).

The fortis stops were found in all positions (even as first members of geminates), the fortis fricatives only as the first member of (partial) geminates. Their presence is revealed by the absence of passive voicing. It might be objected that if fortis fricatives existed in OE phonology, why were they not employed in a more varied set of environments. The answer is rooted in the historical changes affecting the fricatives from Germanic to OE: their contrastive capacity was whittled away, leaving them only in a limited set of environments.

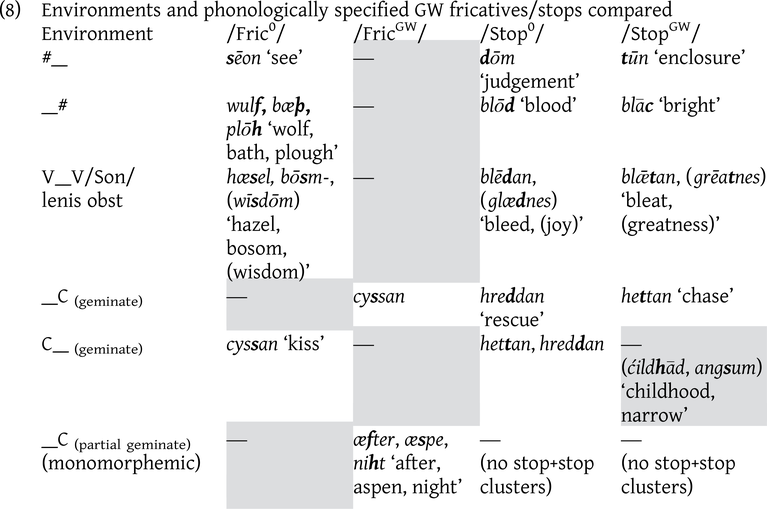

The question of contrast must be addressed. Even though there were fortis fricatives in OE, they could never be contrastive. They could not occur word‑initially, word‑finally or intervocalically (see (8)).

The fortis fricatives were relevant (contributing to the development of contrasts in the fricatives in ME/MoE), but never found in the same environment with lenis fricatives. In classical structuralist taxonomy, one might say they were in complementary distribution, but this is where the comparison ends. GW fricatives were phonological entities, but their non‑contrastive distribution was shaped by the history of the obstruent system. They must be considered the remnant of a once‑existing wider set of contrasts. The distribution in (8) can, however, be called non‑relevantly contrastive for lack of a better term (the environments do not overlap, but the GW feature is phonologically coded and cannot be dismissed as non‑phonemic/allophonic). Scobbie & Stuart‑Smith (Reference Scobbie, Stuart-Smith, Avery, Dresher and Rice2008) discuss the notion of scalar contrast, as well as ‘marginal’ contrast rooted in diverse (historical) causes. Laker (Reference Laker2009) discusses the possibility that OE already had phonemicised voiceless and voiced fricatives. The process, it is argued, was bolstered by Brittonic. Laker (Reference Laker2009: 214) admits there exist no minimal pairs that would settle the problem. It is not the absence of (near) minimal pairs that may prove crucial, but rather the absence of identical environments with differently voiced fricatives from some historical source. It is perfectly conceivable that some fricatives were voiceless in (voiced) environments where the contrast could not be compromised, but even if they were, there is no phonological (as opposed to possible, but unprovable phonetic) evidence that they were systematically distinguished in the same environment. OE blosm [s] vs bōsm [z] ‘bosom’ seems minimal, but blosm may be argued to be /blostm/, which corresponds to its historical form, so the absence of voicing is regular (it was also spelt blostm).Footnote 6 We may also say that by the time [t] was irretrievably lost in late OE or ME, the change left /sGW/ behind, unable to be passively voiced. Kiparsky (Reference Kiparsky, Honeybone and Salmons2015, Reference Kiparsky, Hyman and Plank2018) discusses cases of quasi‑phonemes (in connection with secondary splits that increase the number of contrastive sounds), sounds that can be argued to have acquired phonemic status even though their conditioning environment was still present. When the conditioning environment is lost, the segment originally affected by the environment emerges unchanged (showing that it did not depend on the environment for its interpretation even when the conditioning was still present). A commonly quoted example from ME comes to mind: after the loss of word‑final schwa (e.g. Trnka Reference Trnka, Jones and Fry1935: 63), voice was retained in the fricatives (making them contrast with their voiceless congeners in the same position): leaf vs leave, sooth vs soothe, rice vs rise, etc. The voiced fricatives in the traditional account were retained despite being word‑final, a position where such fricatives were disallowed in OE and early ME, showing that their voice feature was phonologised even before loss of schwa.Footnote 7 This is not relevant for OE fricatives, as the environments where they would have been able to contrast were missing. What is more, OE acquired no new singleton fricatives from a non‑native source (as opposed to ME). Of course, as (8) shows, the two series of stops were phonologically contrastive, hence no enhancement is expected or detected. In morphologically complex formations quasi‑contrasts can be found: rǣsde [zd] ‘rushed’ does (superficially) contrast with (wuldor)fæste [st] ‘glorious’, but there are no instances of [zd] monomorphemically.

The fortis fricatives are therefore only found in monomorphemic [sp, st, sk, ft xt] clusters. Corresponding monomorphemic lenis clusters are missing: **[zb, zd, z![]() , vd/bd, ɣd/

, vd/bd, ɣd/![]() d]. Of these, *[zb] never existed in West Germanic (/b/ being phonetically [v] after continuants), but even if it had, it would be found as [rv] 〈rf〉 in OE (given the *z0 > *r change in West Germanic). A comparable cluster is found in earfoþ ‘hardship’ (German Arbeit), from *[rv] (/rb/ or /rβ/ in standard analyses; cf. Ringe & Taylor Reference Ringe and Taylor2014). [zd] ([zð] /zd/ of West Germanic) is also missing in OE, given the *z0 > *r change (*gazdjōn > OE gierd ‘yard’). [z

d]. Of these, *[zb] never existed in West Germanic (/b/ being phonetically [v] after continuants), but even if it had, it would be found as [rv] 〈rf〉 in OE (given the *z0 > *r change in West Germanic). A comparable cluster is found in earfoþ ‘hardship’ (German Arbeit), from *[rv] (/rb/ or /rβ/ in standard analyses; cf. Ringe & Taylor Reference Ringe and Taylor2014). [zd] ([zð] /zd/ of West Germanic) is also missing in OE, given the *z0 > *r change (*gazdjōn > OE gierd ‘yard’). [z![]() ] ([zɣ] /z

] ([zɣ] /z![]() / of West Germanic) is found as [rɣ] in OE (*mazga > mearh/mearg, mearges ‘marrow, GSg’). [vd] and [ɣd] are also missing because of Common Germanic constraints and/or Indo‑European inheritance.Footnote

8 In other words, [sp, st, sk, ft xt] in OE have no opposing monomorphemic lenis counterparts, that is no [sp] vs [zb], etc.

/ of West Germanic) is found as [rɣ] in OE (*mazga > mearh/mearg, mearges ‘marrow, GSg’). [vd] and [ɣd] are also missing because of Common Germanic constraints and/or Indo‑European inheritance.Footnote

8 In other words, [sp, st, sk, ft xt] in OE have no opposing monomorphemic lenis counterparts, that is no [sp] vs [zb], etc.

8. Fricatives enhanced with GW

GW in the fricatives of OE was only sparingly exploited phonologically. Phonetically, however, it could be derivatively added to lenis fricatives in certain phonological positions by a mechanism known as Vaux’s law (9).

The rule in (9) ensures that fricatives are enhanced with GW whenever possible (bearing in mind the language‑specific constraints on strong vs weak positions). Enhancement cannot lead to new (or compromise existing) phonological oppositions. If a language has a phonological opposition between unmarked and GW fricatives, as does MoE, the unspecified fricatives lack enhancing. In OE the fricatives were never found in an environment where a contrast was possible, so they could be enhanced with GW. The next question is where such enhancement occurred in OE. In intervocalic position, the unspecified fricatives were phonetically voiced. In other words, they were enhanced with GT (a.k.a. passive voicing). The degree of propagation of GT in the examples in (10) was categorical (the MoE continuations unfailingly have phonetically voiced lenis fricatives or their continuations).

The question is whether all fricatives in voice‑friendly environments were voiced must be answered in the negative. Evidence comes from the absence of voicing before stressed vowels (or word‑initially); see (11).

These intervocalic fricatives may be expected to emerge voiced in this environment, yet none survives as such, similarly to word‑initial ones (fæder, sēon, fultrū́wian). A straightforward explanation emerges: they were enhanced with GW and were thus impervious to perseverative voicing. This enhancement is visible in the northern varieties of ME as compared to the southern ones whence ME varieties with word‑initial ‘voiced’ fricatives descend, where unenhanced fricatives would have been interpreted as phonetically voiced (vial, vixen, zenne); see Lass (Reference Lass1991–3) and below.

9. The relevance of voice(lessness) in OE fricatives

Whether a fricative was phonetically voiced or not was irrelevant given that OE had no laryngeal contrast in the fricatives: whether wīf was pronounced with word‑final [v] or [f] (or anything in between) did not matter phonologically. It is conceivable (given modern phonetic analyses) that the phonetic value of the final fricative was gradient; cf. the discussion in Cruttenden (Reference Cruttenden2014, §9.4) on the phonetic opposition between lenis and fortis fricatives in MoE. In terms of Iverson & Salmons (Reference Iverson and Salmons2003), passive voicing can be modelled as the (gradient) propagation of GT from left to right dependent on how voice‑friendly an environment was, the most conducive one to voicing being the post‑tonic intervocalic one, as in hæsel. Viewed from MoE, post‑tonic fricatives unfailingly survive as lenis only when they were followed by a vowel or a sonorant, attesting to a high degree of robustness of propagation of GT compared to that found in post‑tonic word‑final fricatives (scythe vs bath). Historically, bath shows that the propagation of GT in OE/ME baþ fell below the phonological threshold of a ME speaker, showing that such fricatives had no categorical GT phonetically.Footnote 9 Mapping phonetic variation on phonological categoricity has become important (cf. the notion of fuzzy contrast in e.g. Turton Reference Turton2017; Strycharczuk & Scobbie Reference Strycharczuk, Scobbie, Przewozny, Viollain and Navarro2020). Historical linguistics may prove essential in showing how phonology codes scalar phonetic properties. In our account, the problem of MoE fortis fricatives in wolf, bath, grass does not originate in OE (with variably voiced fricatives), but rather in ME where these received phonological GW: wolf /fGW/, bath /θGW/, grass /sGW/. One of the conditions for their variable phonetic voicelessness being reanalysed as GW in ME must have been provided by words that originally had (categorically voiceless) geminates in OE, such as moth, coss ‘kiss’, wish. The difference between a word‑final ‘somewhat’ voiced fricative (bath) and a completely voiceless one (moth) would have been impossible to maintain in the long run (in a language with a developing system of fortis vs lenis opposition in the fricatives a decision had to be ‘taken’ on the phonological status of word‑final fricatives). As revealed by bath vs bathe, ME did not have word‑final devoicing of the originally categorically voiced fricatives; see Maguire et al. (Reference Maguire, Alcorn, Molineaux, Kopaczyk, Karaiskos and Los2019) for an analysis of word‑final devoicing of OE [v] in pre‑Literary Scots.

Stress thus must also have played a role in cuing a phonetically voiced fricative: one found after a stressed vowel, as in bæð , is more likely to have been phonetically voiced than the final one in duguð ‘nobles’. Phonologically, these degrees of voicing were irrelevant: wulf, bæð, græs, duguð end in fricatives that are phonologically neither voiced, nor voiceless, and phonetically variably so. When part of an obscured compound, the unmarked /f0/ (as in līflād) was in a better position phonologically to be categorically voiced. Encapsulated in this remark is the supposition that word‑final /f0/ in (hē ūs) līf forgeaf, (þǣr is) līf gelang or prepausal līf was voiced/voiceless to varying degrees, but was categorically voiced in (obscured) līflād or (inflected) (on) līfe on the evidence of MoE livelihood/alive /f0/ vs life /fGW/.

The extent of voicing in fricatives flanked by unstressed syllables in (pre‑)OE is another moot question; cf. MoE cleanse with lenis /z0/ (< *klainisōjan)Footnote 10 vs filth (fӯlþ(u) < *fūliθu), seventh (seofoþa), month (< mōn(a)þV‑) with fortis fricatives in MoE, which are apparently less problematic (see Luick Reference Luick, Wild and Koziol1914–40, §639.2). A voiced fricative would not be phonotactically impossible here ([mənðz] being a phonotactically possible plural of month). However, whenever such fricatives came to be preceded by a stressed vowel, they are found as lenis in MoE (e.g. *sigiθe > sigþe, sīþe ‘scythe’), showing that stressed vowels were better at supporting the phonetic cues identifying a voiced fricative. In words like seofoþa, *sigiθe there was no enhancement with GW (as the fricatives were found in a weak position). Here, given the unstressed vowel before the fricatives, there would have been no categorical propagation of GW (for clǣnsian and adesa ‘adze’, however, see footnote 6).

It was not phonetically impossible for a word‑final fricative to be perceived as voiced even when preceded by an unstressed vowel. Examples come from early fourteenth century voicing (Luick Reference Luick, Wild and Koziol1914–40, §763) that affected word‑final ‑s preceded by an unstressed vowel: the third-person singular of verbs (hisses), plurals (bridges, Wales), possessives (John’s) and (originally) non‑plural nouns (alms, eaves, James, Charles, Thames, Well(e)s).Footnote 11 There is no phonological argument for viewing this process to be a ME phenomenon exclusively. This phonetic voicing may have been variably present in OE as well. There is no orthographic evidence for this, but this is expected given the absence of opposition. Additionally, as Fulk (Reference Fulk2002) shows, OE word‑final fricatives followed by voiced sounds in obscured compounds survive voiced in MoE (e.g. Southill /ð0/ < sūþ + Gifle), showing that such fricatives were enhanced with GT (similarly to scythe).

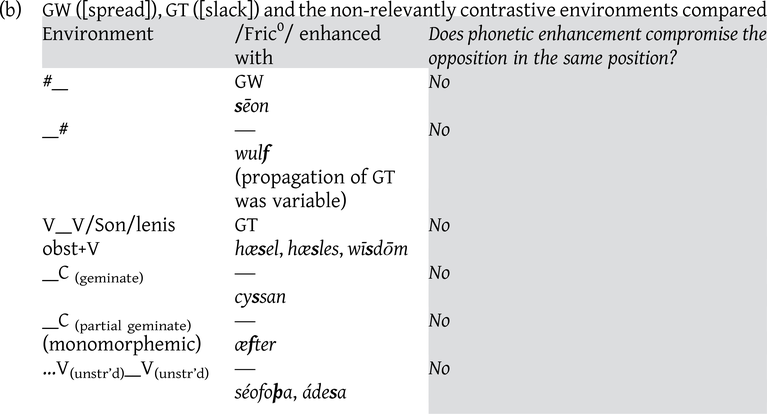

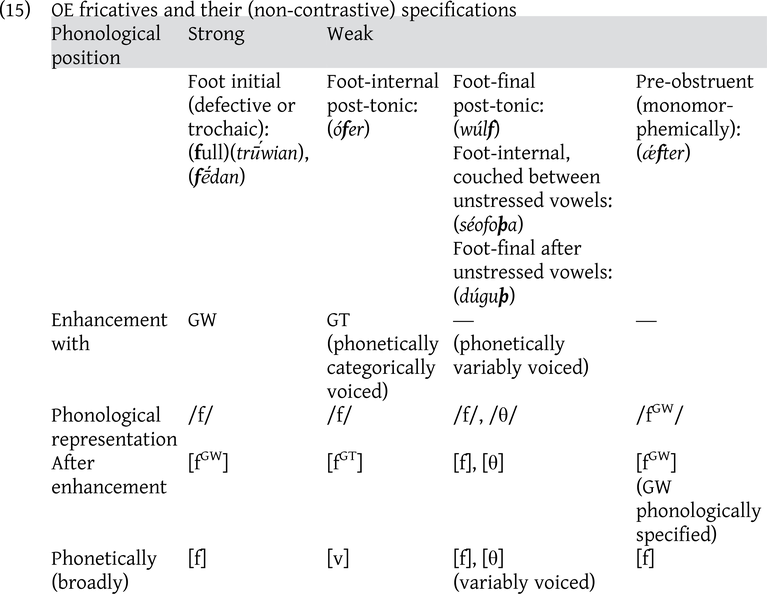

10. The domain of enhancement

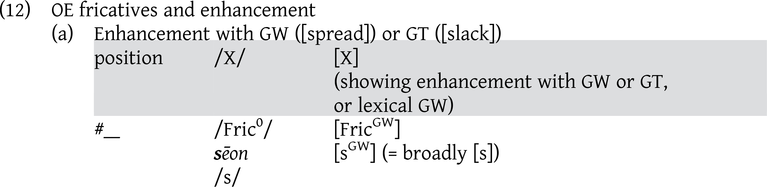

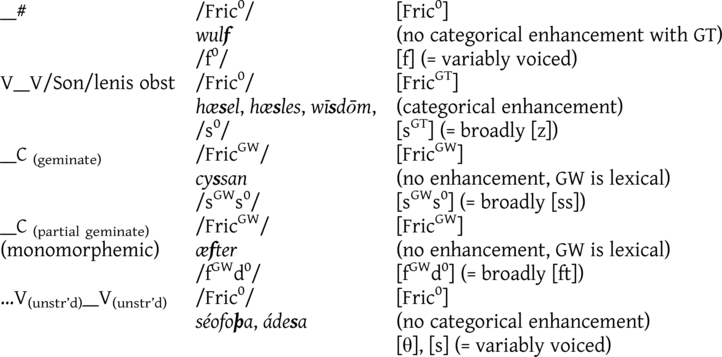

Enhancement with GW applied foot‑initially, i.e. at the left‑periphery of either a defective or a trochaic foot: ( full)(trū́wian) ‘confide’, (be)( fóran) ‘before’.Footnote 12 (Categorical) enhancement with GT applied within trochaic feet: (ófer), (sī́ðe), (hǽsel), (lágu). Variable enhancement with GT happened at the end of trochaic feet: (wúlf ), (bǽð ), (grǽs ), (dā́g ), (dúguð ), as well as foot‑internally to fricatives couched between two unstressed vowels, i.e. (séofoþa), (*fӯ́liθu), (ádesa). We interpret the absence of non‑categorical passive voicing in (what would appear to be) a voice‑friendly environment (séofoþa ) as a consequence of the inability of the surrounding prosodically weak vowelsFootnote 13 to cue voicing for a (post‑OE) generation of speakers with a nascent phonological opposition of fortis vs lenis. A summary is provided in (12a). Example (12b) shows that enhancement with GW could evolve exactly because it compromised no contrast. Enhancement with GT in intersonorant position did not compromise any contrast either (but this is less controversial).

In Ayenbite of Inwyt of Kentish provenance from the fouteenth century, the newly invented orthography of Dan Michael shows for the first time the orthographic imprint of phonetically voiced fricatives. Apparently, there is voicing word‑initially where one would expect voiceless continuations of OE fricatives (e.g. uader ‘father’, uram ‘from’, zenne ‘sin’, zuord ‘sword’). The data are discussed in various frameworks, starting with Luick (Reference Luick, Wild and Koziol1914–40). Honeybone (Reference Honeybone, van Oostendorp and van de Weijer2005a, Reference Honeybone, Nevalainen and Traugott2012), for example, terms it South English Fricative Voicing (SEFV) or South English Fricative Weakening (SEFW). The process is also known as Old English Fricative Voicing (Lass Reference Lass1991–3) or the Voicing of Initial Fricatives in ME (Fisiak Reference Fisiak1984). The problems are apparent: if a voiced fricative can only be conceptualised as one showing the ‘added’ feature of GT, the origin of voicing remains obscure. The process occurred domain‑initially, making it sit uneasily in theories of lenition. Honeybone (Reference Honeybone, van Oostendorp and van de Weijer2005a) sees this as de‑laryngealisation. A [fGW] (his fh) losing GW was (phonetically) [v] (phonologically, it was still /f0/), [sGW] as [z], etc. The new/word‑initial lenis fricatives seem to have merged with word‑internal intersonorant ones (uzeþ ‘he uses’). Even more telling is that uerst ‘first’ is spelt with the same 〈u〉 found in Old French uirtues ‘virtues’ (cf. uour uirtues cardinales ‘four cardinal virtues’). The author does not consistently use his self‑invented orthography. There is no new symbol for a ‘voiced’ thorn, although 〈þ〉 /θ0/ in words like þre, þinges, þe, þet may conceivably have been [ð] (cf. Wakelin & Barry Reference Wakelin Martyn and Barry1968; Thurber Reference Thurber2011). Our interpretation is that these word‑initial fricatives do not show the abandoning of OE enhancement with GW, but the continued phonetic interpretation of unenhanced fricatives as voiced in the southern varieties of OE, from which this Kentish variety of ME developed, in addition to the rest of the southern varieties (cf. Lass Reference Lass1991–3). In other words, in the south of England, there was no enhancement with GW in the strong positions. This adds a new dimension to phonetic variation in OE, something that needs to be addressed separately.

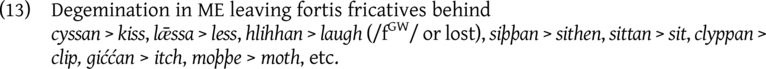

11. Middle English degemination

As discussed above, OE geminates are found voiceless in ME (see (13)). The absence of compensatory lengthening in a language with an established opposition of long vs short vowels is conspicuous: the vowels of moth, kiss, bed, sit, etc. never show a lengthened reflex. Following de Chene & Anderson (Reference Chene and Anderson1979: §2.32) we propose that this degemination involved the loss of the second (lenis) member of the cluster, leaving a fortis obstruent behind and no compensatory lengthening as such consonants were lost in unstressed syllables (or word‑finally): cyssan /kGWysGWs0an/ > kissen /kGWisGWən/, **/kGWeːsGWən/. The same process affected the OE lenis geminate stops with no compensatory lengthening either, leaving behind lenis stops, as expected: frogga /![]() 0

0![]() 0/ > frog /

0/ > frog /![]() 0/, brycg /dʒ0dʒ0/ > bridge /dʒ0/, see (13).

0/, brycg /dʒ0dʒ0/ > bridge /dʒ0/, see (13).

The ME period is when the modern contrastive distribution of the fricatives is established (bath vs bathe, grass vs graze, etc.). The details are complex and long‑drawn‑out. Degemination of OE voiceless fricatives and loss of word‑final schwa, nevertheless, contribute to the nascent contrast in fricatives in intersonorant and word‑final position. There is no phonological reason for enhancing the fricative in moth, but not in bathe. After degemination moth, kiss, itch have fortis fricatives because of OE inheritance (these must have been strengthened in their status by French loans having voiceless fricatives). We also claim that words having [s/f/x]+stop clusters (last, aspen, ask, haft, night) also inherited fortis fricatives from OE.

12. Inheritance of GW

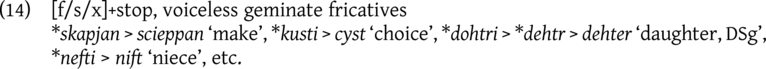

The question is why [f/s/x]+stop clusters or voiceless geminate fricatives contained a GW fricative and whether this was due to enhancement or inheritance. The answer must be sought in inheritance and the difference between strong and weak positions. If a change is recorded in (whatever counts as) a strong position, that change is also observed in the weak positions, but not the other way around: if debuccalisation (e.g. [fGW] > [h]) takes place in the coda (weak position), it does not necessarily take place in word‑initial onset (strong position). There is evidence for the unspecified fricatives enhanced with GW in word‑initial position (habban) and before a stressed vowel (behíndan), but there is no evidence for this word‑finally. In [f/s/x]+stop clusters (and the voiceless geminates) the first member of the cluster was in coda; see (14).

Although there is disagreement about the syllabification of s+stop sequences as coda‑onset, all syllable‑based accounts would argue for a syllable boundary forcing a geminate or a [f/x]+stop into a coda‑onset (sciep.pan, deh.ter) or a complex coda (meaht). There is also the argument internal to OE for syllabifying these clusters as shown: pre‑OE high vowels (*i, *u) and *j were deleted after heavy syllables, including those made heavy by a coda consonant (e.g. *doh.tri > *dehtr > dehter), including s+stop clusters (e.g. *kusti > cyst; cf. also Hogg Reference Hogg2011, §6.18). The data show that [f/s/x] were in the coda, which is a weak position, in which (given the OE facts) enhancement with GW is not expected. The presence of GW must show inheritance from a period preceding OE, a period when /sGWd0/ [st] was opposed to /s0d0/ (= /zd/, as traditionally understood). The opposition between these clusters ceased in West Germanic after the *z0 > *r change. The question that arises is what phonetic cues were there to maintain the phonological representation of [st], for example, as /sGWd0/, rather than /s0d0/. The answer is beguilingly simple, we think: phonetically, it was the absence of perseverative voicing in voice‑friendly environments that helped cue the underlying identity of [st] as /sGWd0/. Phonologically, there would have been no mechanism to prevent passive voicing from affecting /s0d0/, a sequence of two unmarked consonants (a lenis cluster in itself presented no hindrance to passive voicing, cf. rǣsde). The phonetically voiceless OE geminate fricatives (e.g. /sGWs0/) and [f/s/x]+stop clusters (e.g. /sGWp0/) show the preservation of pre‑OE GW into OE. Although GW is not contrastive in OE singleton fricatives, its presence is relevant for OE phonology, see summary in (15).

13. Conclusions

The two series of OE stops are distinguished as lenis/unmarked vs fortis (marked for GW). Laryngeal enhancement adds the dimension of GW (completed as [spread]) to the singleton lenis fricatives in the strong positions at the left periphery of a defective foot or a trochee, shown by the absence of fricative voicing in the V(Son)FricV́ environment ((be)( fóran)) in the non‑southern varieties of OE. Fricatives specified for GW were impervious to passive voicing (i.e. the propagation of GT in voice‑friendly environments). In the foot‑internal weak position fricatives ((hæsel)) were categorically enhanced with GT (they underwent categorical passive voicing, witnessed by the MoE lenis reflexes). Foot‑final fricatives after a stressed vowel ((wulf )) or after an unstressed vowel ((duguþ )), as well as foot‑internal ones couched between unstressed vowels ((seofoþa)) were unenhanced with GT (and phonetically variably voiced, emerging as fortis in MoE, e.g. wolf, seventh).

One of the outcomes of the analysis can be seen in the structure of voiceless geminate fricatives (〈ff〉, 〈ss〉, etc.) and fric+stop clusters (〈ft〉, 〈st〉, etc.): these are composed of a lexical, phonologically fortis fricative followed by a lenis fricative/stop (/fGWf0/ 〈ff〉, /fGWd0/ 〈ft〉, /sGWd0/ 〈st〉). These fortis fricatives are the remnant of a pre‑OE system with a more extensive system of contrastive fortis vs lenis fricatives. These OE lexical fortis fricatives were revealed owing of a change in perspective that sees OE as a GW language. The question as to whether OE had phonologically specified fortis fricatives must be answered in the affirmative. Their distribution was limited, but they contributed to ME developing a wider system of contrastive fricatives than that of OE, a system which survives in MoE.

Acknowledgements

This publication was (partly) sponsored by the National Research, Development and Innovation Office (OTKA #142498). I would also like to thank the two reviewers for their insightful comments. Not all of them could be incorporated. I would also like to thank the editor for their help in the production.