Introduction

Nativist forces are gaining ground politically in many Western societies, often by fomenting tension around the arrival of ‘Others’ presented as being inherently dangerous and/or inferior.Footnote 1 In the case of the UK, several studies have documented the hostile asylum policies of consecutive governments, which treat ethnocultural ‘Others’ as threatening and undeserving of support.Footnote 2 This ‘securitisation’ of migration, the process of blurring migrant categories together and socially constructing them as dangerous to the host society, has not only increased prejudice and legitimised the suspension of human rights for refugees in the UK and internationally but has also fuelled anti-immigration attitudes, which were a key driver of the ‘Brexit’ vote.Footnote 3 More recently, the anti-immigration riots and anti-racism counter-demonstrations that swept across Britain in August 2024 highlighted the alarming growing societal divisions within refugee-hosting states. Yet while we know how threat perceptions drive hostility towards migrants, we still lack the required understanding of how to reverse them, with ‘desecuritisation’ remaining neglected compared to its conceptual twin.Footnote 4 In this context, promoting ‘outgroup empathy’ – the ability to put oneself in the shoes of people who belong to a different group than one’s own – has emerged as a possible solution. Indeed, strong empirical evidence shows its association with positive immigration attitudesFootnote 5 and may even be ‘a better predictor of support for immigration than any other predisposition or socio-demographic factor, save authoritarianism’.Footnote 6

The high societal value of outgroup/intergroup empathy has been well documented across multiple fields of study and professional practice and has been celebrated as necessary for deliberative democracyFootnote 7 and more inclusive and equitable societies.Footnote 8 However, at the heart of most empathy research, including its application to migration studies, lie three fundamental challenges which should make us cautious. The first challenge is conceptual: empathy is a multifaceted and inconsistently defined construct, with research often failing to align its definitions and measurements, limiting validity and comparability.Footnote 9 The second challenge is methodological, as the widespread reliance on self-reported empathy measures introduces biases such as socially desirable respondingFootnote 10 and gendered framing.Footnote 11 Self-reported empathy measures are tailored to ingroups taking a presumed perspective of an outgroup. However, neither ‘perspective-taking’ (cognitive empathy) nor ‘empathic concern’ (affective empathy) correlate with more accurate perception and comprehension of others’ emotions, when self-reported.Footnote 12 Simply, how can we be sure that the version of the world one sees through another’s eyes is valid, if we haven’t asked the ‘Other’ in the first place how they see the world? Lastly, the third challenge arises from empirical observations that empathy may not always be a ‘silver bullet’ for improving intergroup relations and can sometimes exacerbate polarisation or conflict.Footnote 13 Specifically, perspective-taking can amplify cooperation or competition, fostering positive outgroup attitudes while leaving biases unchanged.Footnote 14 Crucially, it may trigger selfish behaviourFootnote 15 or backfire when the ingroup feels under threat,Footnote 16 as seen in Ecuador, where empathy towards Colombian refugees led to temporary desecuritisation, later reversed.Footnote 17

Reflecting on these challenges, the aim of this paper is to propose a novel relational construct and measurement of empathy associated with perspective-taking, which we call Intersubjective Empathy (IE). IE is defined as the degree to which ingroup members can accurately recognise how outgroup members feel, given their circumstances. This construct requires that an ingroup’s presumed perspective of an outgroup’s emotions is triangulated with the actual emotional state reported by the outgroup itself. We propose, operationalise, and validate this concept, empirically testing its relevance to public attitudes towards refugees and outgroup helping in the UK. Situating our study within a highly polarised context, after the 2015 ‘refugee crisis’ and the UK’s referendum to exit the European Union (EU), provides an ideal setting to assess Intersubjective Empathy as a potential but contingent factor in desecuritising migration, controlling for other established political, economic, and sociocultural factors. Driven by a normative agenda, we ask three questions. First, is Intersubjective Empathy associated with reduced threat perceptions towards refugees? Second, does Intersubjective Empathy correlate with an increased sense of duty to help refugees? And third, can Intersubjective Empathy sometimes ‘backfire’?

To respond to these questions and test the usefulness of our proposed measure, we draw on unique and rare survey data capturing the attitudes of both UK citizens (n = 1,534; October 2017), and the experiences, emotions, and attitudes of young (18–32 years old) Syrian refugees in the UK (n = 484; July–September 2017). The first part of the paper outlines the interdisciplinary theoretical insights which inform our construct and analyses, drawing on securitisation theory, psychology, and political behaviour. We then operationalise and validate intersubjective empathy, showing that it correlates significantly with several prosocial attitudinal, affective, and motivational variables. Next, through multiple regression analysis, we demonstrate that Intersubjective Empathy is associated with reduced public perceptions of refugees as a threat, even when controlling for most other dominant factors identified in the political behaviour literature. Our construct also has a significant motivational component. The final part of the paper documents this through a general linear regression analysis, which shows that Intersubjective Empathy correlates with an increased sense of duty to help refugees, the essence of successful desecuritisation at the stage of mobilisation. However, there is a caveat: the initial positive effects of increased Intersubjective Empathy on outgroup helping have diminishing returns after a certain level of IE is reached and may, indeed, backfire. Our conclusion returns to and summarises conceptual, methodological, and empirical contributions we are seeking to make and explores their broader real-world implications.

(De)securitisation of migration and outgroup empathy

Migration in Western societies has undergone a process of securitisation, whereby it has come to be treated predominantly as a threat, not because of its ‘real’ or objective significance but because it has been socially constructed as such. According to securitisation theory, perceptions matter more than objective realities and are socially constructed through languageFootnote 18 and non-discursive practices and structures.Footnote 19 Migrants are typically depicted as a threat to the majority ingroup, legitimising the suspension of their human rights and, in the case of refugees, violating the international protection regime enshrined in the 1951 Refugee Convention. The decades-long securitisation of migration in Europe and the damaging and even deadly outcomes of ‘Fortress Europe’ for refugees have been well documented.Footnote 20 Although the different reasons people move are blurred when security discourses and practices become dominant in dealing with migration, the content of such arguments typically evolves around four main axes: an economic axis, about the migrants’ impact on the national economy; a cultural axis, about the threats they pose to the majority/national identity; a criminological axis, about the perceived threats they pose to public order; and a securitarian axis about threats to national security.Footnote 21 As Lazaridis and Wadia note, ‘asylum seekers and other migrant categories come to be seen as agents of social instability or as potential terrorists seeking to exploit immigration systems’.Footnote 22

The Security Studies literature has, however, not yet provided satisfactory answers to how to successfully reduce threat perceptions and intergroup competition. Despite some notable advancements centred around the concept of ‘desecuritisation’Footnote 23 – the untangling of security discourses, threat perceptions, and security practices – this area remains nascent.Footnote 24 Securitisation theory’s initial emphasis on decisive ‘speech acts’ and Buzan and colleagues’ designation of discourse analysis as ‘the obvious method’ to study itFootnote 25 not only obscured the contestation that typically occurs between competing securitising and desecuritising framesFootnote 26 but also disregarded, conceptually and methodologically, the role of the audience, which plays the decisive role.Footnote 27 As Buzan and colleagues explain, the audience determines whether something is an existential threat to a shared value, not the actors who make the claims or those contesting them: ‘thus, security (as with all politics) ultimately rests neither with the objects nor with the subjects but among the subjects’, making securitisation ‘an essentially intersubjective process’.Footnote 28 Later studiesFootnote 29 further specified that audiences, often the general public, have to make a dual evaluation: assess first the claim that ‘this is a threat’ (i.e. the ‘stage of identification’) and, second, the argument that ‘given that this is a threat, this is what we need to do about it’ (i.e. the ‘stage of mobilisation’). Illuminating the audience’s role requires diversifying the theory’s methodological toolbox, fertilising and strengthening interdisciplinary connections, and incorporating quantitative methodologies to study public attitudes towards outgroups in general, and migrants in particular.Footnote 30

These highlight the critical role of contestation in shaping public attitudes and threat perceptions – an aspect that is ‘often, and problematically, conceived as synonymous with desecuritisation’.Footnote 31 In cases of institutionalised securitisation, as with migration, ‘where the audience has been perpetually primed about the dangers the arrival of migrants and asylum seekers pose … any attempts to desecuritise the representation of migrants is likely to face resistance’,Footnote 32 raising doubts as to whether desecuritisation is ever feasible.Footnote 33 Empirical findings from Scotland demonstrate that civil society can, in certain contexts, successfully contest the ‘migration–security nexus’ through discursive and predominantly non-discursive activities.Footnote 34 More commonly, however, humanitarian organisations strive to evoke compassion by employing ‘the politics of pity’, with questionable results.Footnote 35 For example, Shetty finds that the depiction of Calais asylum seekers as ‘helpless victims, who can be helped only through Western agencies’ and the notable absence ‘of asylum-seeker-produced visuals in the political debates of Western media’ strip asylum seekers of their agency and voices and may also backfire by further dehumanising them.Footnote 36

The affective nature of salient desecuritising attempts, exemplified by the ephemeral wave of empathy that spread across the UK and Europe following the publication of the image of three-year-old Alan Kurdi’s dead body on a Turkish beach, underscores the crucial role of emotions in (de)securitisation contests. Yet hardly any attempts have been made to theorise this connection or integrate securitisation research with well-established relevant debates in psychology. One exception is Van Rythoven, who showed that ‘when the capacity to generate collective fears is constrained, so too is the practice of securitization’.Footnote 37 Applying this to migration attitudes, we ask: could some form of empathy towards ethnocultural ‘Others’ be associated with challenging the ‘Us vs Them’ logic of securitisation? And, in turn, could it be linked to lower threat perceptions and greater public support to care for them, rather than curtail them? Rejecting the security-threat framing does not automatically entail a guaranteed increase in the public’s motivation to care for refugees, as audiences have to make a ‘dual evaluation’ in securitisation contests. Following the analytical framework proposed by Karyotis, Paterson, and Judge,Footnote 38 we therefore argue that successful desecuritisation should be understood as a two-stage process, reducing threat perceptions at the stage of identification and activating a sense of duty to care at the stage of mobilisation. To assess empathy as a potential pathway to the desecuritisation of migration, we must empirically and rigorously test its effects in relation to both stages.

Indeed, outside Security Studies, the evidence is plentiful that outgroup empathy is associated with positive immigration attitudes.Footnote 39 Impressively, this finding has been corroborated across different Western contexts in Europe and North America;Footnote 40 across different referent migrant labels, from undocumented migrantsFootnote 41 and refugees,Footnote 42 to ethnic minoritiesFootnote 43 and immigrants more broadly’Footnote 44 and by both ‘traditional’ and experimental public opinion studies.Footnote 45 However, each of these studies focuses on different affective, perspective-taking, or motivational aspects associated with outgroup empathy; most of them rely on self-assessed measures; and none, to our knowledge, considers the perspectives of citizens and migrants concurrently. In our paper, we are normatively driven by an ambition to develop a construct of outgroup empathy that avoids the pitfalls of self-report but maintains the prosocial and pro-migrant tendencies that have recently attracted scholarly attention. To develop our concept, in preparation for empirical testing, we need to delve deeper into psychology.

The psychology of outgroup empathy

Psychology distinguishes between ingroup and outgroup/intergroup empathy. It considers the former a prerequisite of any group/community that is positively associated with greater prosocial behaviour towards one’s own group/community members.Footnote 46 Outgroup/intergroup empathy, on the other hand, and more specifically empathy towards outgroup members who are ethnically and culturally different from the ingroup/majority (i.e. ‘ethnocultural empathy’), is rarer. Along these lines, while caring for the well-being of ingroup members is common, people are far less likely to be motivated to alleviate the suffering of outsiders.Footnote 47 Yet recent studies have shown that this ‘caring for the other side’ can be activated under certain circumstances, even for outgroups that are perceived to be threatening.Footnote 48 As Kalla and Broockman found in their experimental research, ‘interpersonal conversations that deploy the non-judgmental exchange of narratives can reduce exclusionary attitudes’.Footnote 49 This, however, may be difficult to achieve if we exclusively rely on constructs of outgroup empathy that do not account for the actual emotions and attitudes of outgroup members. As detailed in the introduction, this represents a major challenge, inspiring us to respond to Sulzer and colleagues’ plea for a conceptualisation of empathy ‘as relational – an engagement between a subject and an object’.Footnote 50 Accordingly, and consistent with securitisation theory, we call this new construct that our article proposes, validates, and tests Intersubjective Empathy.

A key reference for the necessary qualities that should characterise our new construct and the most coherent body of work to measure ingroups’ empathy towards different outgroups empirically is offered by Group Empathy Theory (GET), which employs a multidimensional conception including affective, cognitive, and motivational components.Footnote 51 Outgroup empathy, GET posits, is ‘the ability to take the perspective of others and experience their emotions with the motivation to care about their welfare’, which is necessarily directed towards groups with whom one has little in common.Footnote 52 Outgroup empathy has an affective dimension – empathic concern – which involves a reflexive emotional response to the experiences of another, especially those facing struggle, discrimination, or need. However, its key component is perspective-taking, i.e. the cognitive ability to put oneself in someone else’s shoes, so that one can see the world through another’s eyes. Perspective-taking enables individuals to predict the actions and reactions of others, as noted by Davis.Footnote 53 This cognitive process may enhance intergroup understanding while avoiding negative emotional responses.Footnote 54 Research indicates that perspective-taking, rather than empathic concern, may be more effective in facilitating negotiations and uncovering hidden agreements.Footnote 55 Individuals with strong perspective-taking abilities are less likely to stereotype others,Footnote 56 exhibit greater tolerance for differing opinions,Footnote 57 and show a higher propensity for engaging in political discussions and debates.Footnote 58 Indeed, the ability to imagine/predict what another person feels/thinks given their circumstances has been shown to increase positive attitudes towards outgroups,Footnote 59 including refugees.Footnote 60

Moreover, a requirement for our construct of Intersubjective Empathy is that it has a motivational component to alleviate the suffering of ethnocultural ‘Others’. A large body of work has illustrated the important role of empathy in explaining intergroup/outgroup helping.Footnote 61 Indeed, outgroup empathy is strongly associated with prosocial behaviours like supporting war victims,Footnote 62 donating to charity,Footnote 63 and volunteering.Footnote 64 Overall, outgroup empathy is strongly correlated with support of political actions that have the potential to advance the welfare of an outgroup,Footnote 65 including migrants.Footnote 66 In all, the operationalisation of outgroup empathy as a multidimensional construct and its measurement through the ‘Group Empathy Index’ (GEI) produces evidence that ingroups can see past perceived or objective social divisions and conflicting interests and empathise towards outgroups, which has immense potential for moderating intergroup tensionsFootnote 67 and promoting desecuritisation.

Outgroup empathy has emerged as a leading contender for dislocating prevalent anti-immigration attitudes and a great motivator for incentivising caring for refugees and a humanitarian collective response, corresponding to desecuritisation at both the stage of identification and mobilisation. As discussed, however, this requires that the voices and emotions of outgroup members are actively listened to, which most empathy research relying on self-reported measurements does not account for. Our proposed construct of Intersubjective Empathy directly addresses this, and Pedwell’s critique,Footnote 68 by shifting empathy from an ingroup-centred, paternalistic exercise to a relational process that empirically integrates outgroup voices. This ensures that desecuritisation efforts are grounded in the actual experiences and emotions of those securitised. With these in mind, our ambition is to propose, operationalise, and validate a new construct – Intersubjective Empathy – which we employ to empirically assess its relationship with public attitudes towards refugees and outgroup helping in the UK, controlling for other established measures.

Hypotheses, data, and methods

Intersubjective Empathy is our proposed novel relational construct of outgroup empathy, based on the key component of perspective-taking (i.e. cognitive empathy). For measurement, IE requires that an ingroup’s presumed perspective of an outgroup is always triangulated with that outgroup’s actual emotional state. This is crucial because we hypothesise an ‘empathy gap’ between citizens and refugees, meaning citizens cannot fully and accurately recognise the emotions of refugees (H1). To test this, we compare the emotions that refugees actually felt at the time with those that citizens thought they felt.

Any construct intended to capture outgroup empathy should also include affective and motivational dimensions. Indeed, empathy without consideration of at least a motivational component is an oxymoron, since, as Sirin and colleagues aptly put it, ‘sociopaths are known for their keen ability to detect emotions in others but tend to use that knowledge to manipulate and deceive rather than help’.Footnote 69 While we subscribe to a multidimensional understanding of empathy, we advocate for a minimalist definition that treats the relationship between empathy’s cognitive component and its affective and motivational elements as empirical rather than definitional questions. Therefore, unlike other outgroup empathy constructs, affective and motivational components are not built into IE, so we must establish that our construct demonstrates the qualities expected of outgroup empathy. We hypothesise that IE correlates with various prosocial attitudinal, affective, and motivational variables (H2). To test this and ensure that IE is not a stand-in for any other measure, we perform a series of relevant correlations.

We then subject IE to two progressively ‘harder’ tests to establish that our construct is not only associated with the prosocial qualities of outgroup empathy but also correlates with successful desecuritisation at both stages. Specifically, we hypothesise that IE is associated with reduced threat perceptions towards refugees, at the stage of identification (H3), and an increased sense of duty to help them, at the stage of mobilisation (H4). To test the former, we perform a multiple regression analysis to assess the relationship between IE and public attitudes towards refugees, controlling for several established factors. For the latter, we conduct a general linear regression analysis to determine the relationship between IE and UK citizens’ sense of duty to help refugees, controlling for the same variables.

We also acknowledge the possibility that there might be instances where outgroup empathy may ‘backfire’. This is particularly pertinent for intersubjective empathy, given that perspective-taking has been described as a ‘relational amplifier’ that may lead to diminishing or negative returns in competitive situations. Moreover, this is especially relevant to outgroup helping within the context of intergroup relations between citizens and refugees, which are predominantly framed in ‘zero-sum game’ terms in public discourse. Hence, we hypothesise that there is a non-linear relationship between Intersubjective Empathy and the sense of duty to help refugees, resulting in potentially diminishing or negative returns at higher levels of IE (H5). To test this, we include both the linear (Intersubjective Empathy) and quadratic (IE Squared) terms in our general linear regression analysis.

We rely on two sources of data to capture the emotions of refugees and the attitudes and emotions of citizens in the UK. For the first element, we conducted 484 surveys with young (18–32 years old) Syrian refugees from July to September 2017. We recruited 13 peer researchers, comprising 6 young Syrians living in England and 7 in Scotland, all native Arabic speakers. We prioritised female researchers (10 women and 3 men) to reduce known barriers to survey participation among female migrants.Footnote 70 Two peer researchers were based in Coventry, with one each in London, Manchester, Sheffield, and Newcastle. In Scotland, one was based in Aberdeen, one in Edinburgh, and five in Glasgow. This design was influenced by the fact that, at the time, Scotland had welcomed over a third of the UK’s Syrian refugeesFootnote 71 and by the UK government’s policy of ‘dispersed accommodation’, which had resulted in certain local authorities hosting a disproportionately large number of refugees and asylum seekers relative to their populations.Footnote 72 To challenge traditional power dynamics in refugee research and promote active listening, we involved all peer researchers in designing the questionnaire, ensuring that their perspectives shaped both the questions and overall approach. Additionally, they received training on how to minimise the influence of their own experiences and biases in interactions with participants, as well as how to recognise signs of distress and respond with sensitivity.

The majority of the surveys (77 per cent) were conducted in person using Computer-Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI). Peer researchers used tablet devices equipped with an offline version of Qualtrics survey software to carry out these face-to-face interviews. On average, each interview lasted around 45 minutes. The remaining 23 per cent of surveys were completed through Computer-Assisted Self-Interviewing (CASI), allowing us to expand our geographical coverage and reach a larger number of respondents. A link to the online version of the questionnaire was distributed via local authorities and the personal networks of the fieldworkers. For these self-administered surveys, more detailed written instructions were provided to account for the absence of an interviewer. The questionnaire was identical for both methods and was available in Arabic and English, featuring both closed and a few open questions.Footnote 73

Convenience sampling was employed, necessitated by the lack of publicly available official data regarding the detailed demographic breakdown and characteristics of the Syrian population in the UK. Despite limitations, convenience sampling is considered one of the most appropriate avenues for data collection among hard-to-reach populations, whereby the primary selection criterion relates to the ease of obtaining a sample, considering the cost of locating individuals of the target population, the geographic distribution of the sample, and obtaining the interview data from the selected individuals.Footnote 74 An overview of the demographic characteristics of our sample is presented in the online Supplementary Materials.

For the corresponding citizens’ data, we draw on a national survey administered on our behalf online to a randomised sample of British citizens (n = 1,534) by polling organisation Survation in October 2017. In the regression models, data were weighted to the profile of all adults in the UK aged 18+ by age, sex, region, household income, education, 2017 General Election Vote, and 2016 EU Referendum Vote. Demographic descriptives for the citizens survey are given in the online Supplementary Materials. The two questionnaires included all standard measurements of political behaviour and attitudes as they appear in cross-national surveys like the European Social Survey and World Bank and UNCHR surveys on forced displacement but also included original instruments we developed pertinent to our research aims. The question wording and coding for variables used in our subsequent analyses are presented in the online Supplementary Materials. Both studies were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee at one of the co-authors’ universities, ensuring the rights, welfare, and dignity of the participants were protected. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and their confidentiality and anonymity were maintained throughout the studies. Any potential risks were minimised, and participants were given the right to withdraw from participation, at any time without any consequences.

Intersubjective empathy: Operationalisation, measurement, and validation

Given the challenges in empathy research outlined earlier, the key question, as Stosic and colleagues explain, is not what ‘the best measure of empathy’ is, but instead, ‘which facet of empathy is most relevant to my research question and which scale measures that particular facet most validly’.Footnote 75 Considering that empathy scales are not interchangeable but distinct constructs, it is crucial ‘to clarify whether one is talking about an empathy trait (e.g. the motivation to understand others’ emotions) or an empathy ability (e.g. accurately identifying emotional content)’.Footnote 76

Intersubjective Empathy is a construct we seek to operationalise and validate in this paper. IE is defined as the degree to which ingroup members can accurately recognise how outgroup members feel, given their circumstances, and is operationalised by drawing upon both our refugees’ and citizens’ surveys. This differentiates our construct from others in three important ways: first, IE is an ability, rather than a trait. It considers only the cognitive dimension of outgroup empathy and triangulates an ingroup’s presumed perspective of an outgroup with that outgroup’s actual emotional state. Second, IE is situational, rather than dispositional.Footnote 77 This entails that IE is always context-dependent and outgroup-specific, in line with key tenets of securitisation researchFootnote 78 and recent findings on outgroup empathy in social neuroscience.Footnote 79 Lastly, IE is measured through just 2 questions, compared to, for instance, the 14 items used in GEI. The outgroup is asked ‘How do you feel?’ The ingroup is asked separately ‘How do you think the outgroup feels?’

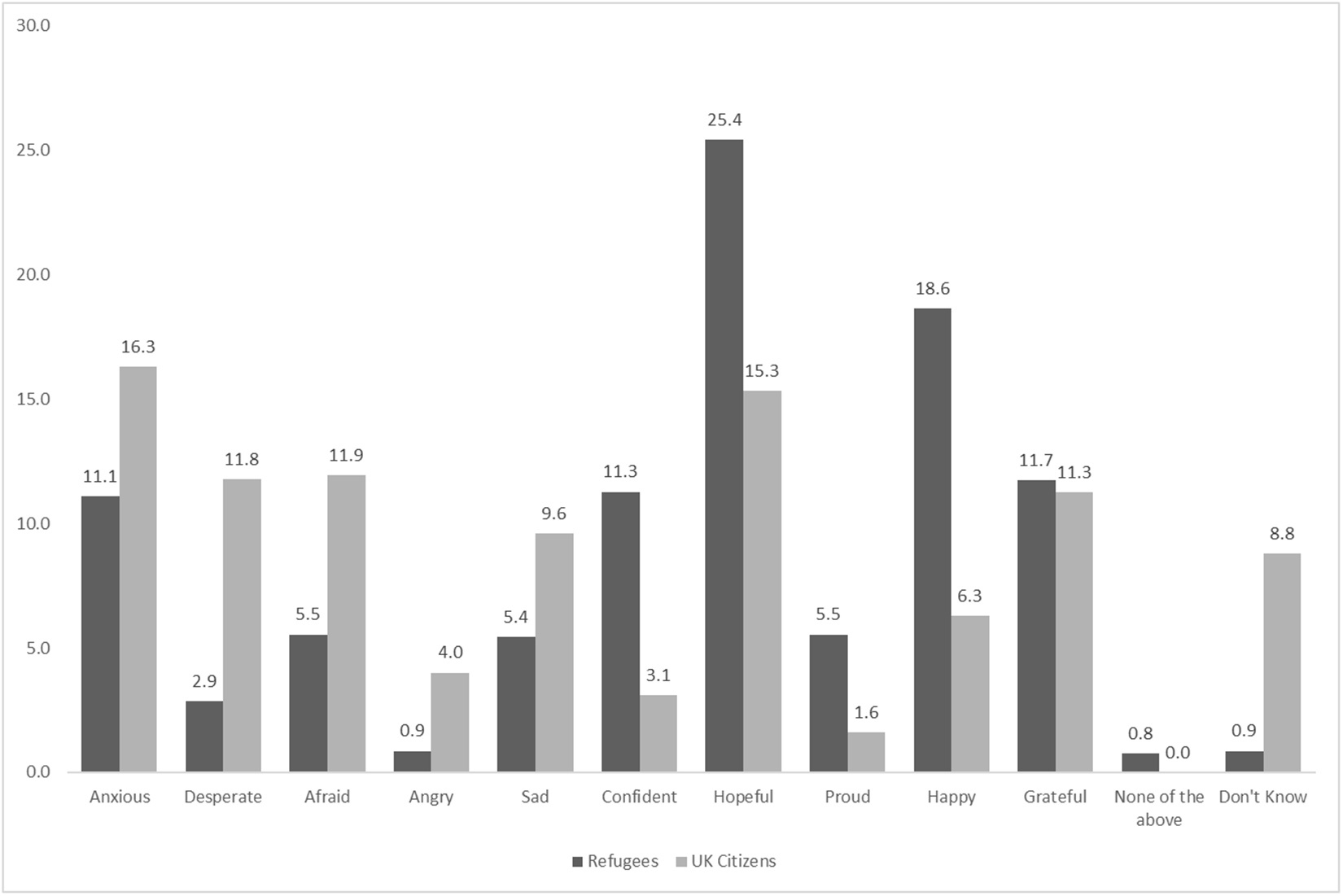

In our survey, we asked young Syrian refugees ‘How do you feel about your current situation in the UK? Which of the following emotions best capture your feelings?’ We rotated the emotions to prevent order effects and allowed participants to choose up to four items. The frequency of responses was as follows: Hopeful (266), Happy (195), Grateful (123), Confident (118), Anxious (116), Afraid (58), Proud (58), Sad (57), Desperate (30), Angry (9), Don’t know (9), None of the above (8). We excluded the latter two and created 10 dummy variables by weighting each of the remaining frequencies according to their overall count (1,030) to find the proportion of the sample identifying with each of these emotions. We also asked British citizens ‘How do you think Syrian Refugees feel about their current situation in the UK? Please select UP TO 4 emotions from the list below that best describe THEIR feelings in your opinion’. We presented them with the same rotated list of emotions and the frequency of responses was as follows: Hopeful (539), Happy (221), Grateful (396), Confident (109), Anxious (573), Afraid (420), Proud (57), Sad (337), Desperate (414), Angry (141), Don’t know (309).Footnote 80

The percentage frequencies of young Syrian refugees’ and UK citizens’ responses are shown in Figure 1. The differences between what young Syrian refugees feel, compared to what UK citizens think they feel, are immediately striking. While refugees report predominantly positive emotions of hope (25 per cent), happiness (19 per cent), gratefulness (12 per cent), and confidence (11 per cent), only one of these is recognised by citizens, who assume that they instead predominantly feel anxious (16 per cent), hopeful (15 per cent), afraid (12 per cent), and desperate (12 per cent). As this indicates, UK citizens were not particularly good at recognising what refugees actually felt at a time of heightened anxiety and polarisation around migration, security, and sovereignty. This supports the idea of the existence of an ‘empathy gap’ between citizens and refugees (H1) and underscores the need for a relational approach to measuring outgroup empathy, which is based on the triangulation of an ingroup’s presumed perspective of an outgroup with that outgroup’s actual emotional state.

Figure 1. Emotions experienced by young Syrian refugees, as identified by them and UK citizens (%).

To calculate Intersubjective Empathy, we gave British citizens who selected ‘Don’t know’ a zero score. The reason for this is twofold. Conceptually, research shows that cognitive empathy involves actively recognising another person’s mental state. A ‘Don’t know’ response can be interpreted as an inability or unwillingness to engage in the cognitive processes necessary to empathise with members of an outgroup, which may reflect a deficit in cognitive empathy. Indeed, from a behavioural perspective, not knowing or being unwilling to guess how members of an outgroup feel can imply indifference or lack of concern about an outgroup’s perspective, which is a critical aspect of empathy. Thus, in practical terms, since we aim to capture ‘actionable’ empathy – i.e. cognitive empathy that is likely to also have a motivational dimension – we take that a ‘Don’t know’ response implies that an individual is unlikely to engage in empathetic actions. This approach aligns with findings that individuals who lack implicit cognitive empathy may still perform relevant emotion recognition tasks when explicitly instructed through vignettes, for example, but otherwise do not engage in empathetic processes.Footnote 81 Our sensitivity analysis (see online Supplementary Materials) shows that Intersubjective Empathy has a similar effect on outcomes in the regression models, regardless of whether the ‘Don’t know’ responses are excluded from the calculation of Intersubjective Empathy.

Intersubjective Empathy was calculated for each UK citizen by multiplying each selected presumed Syrian refugees’ emotion by the proportion of young Syrian refugees who actually selected that emotion and adding them together:

IntersubjectiveEmpathy = (FeelHopeful*.258) + (FeelHappy*.189) + (FeelGrateful*.119) + (FeelConfident*.115) + (FeelAnxious*.113) + (FeelProud*.056) + (FeelAfraid*.056) + (FeelSad*.055) + (FeelDesperate* .029) + (FeelAngry*.009)

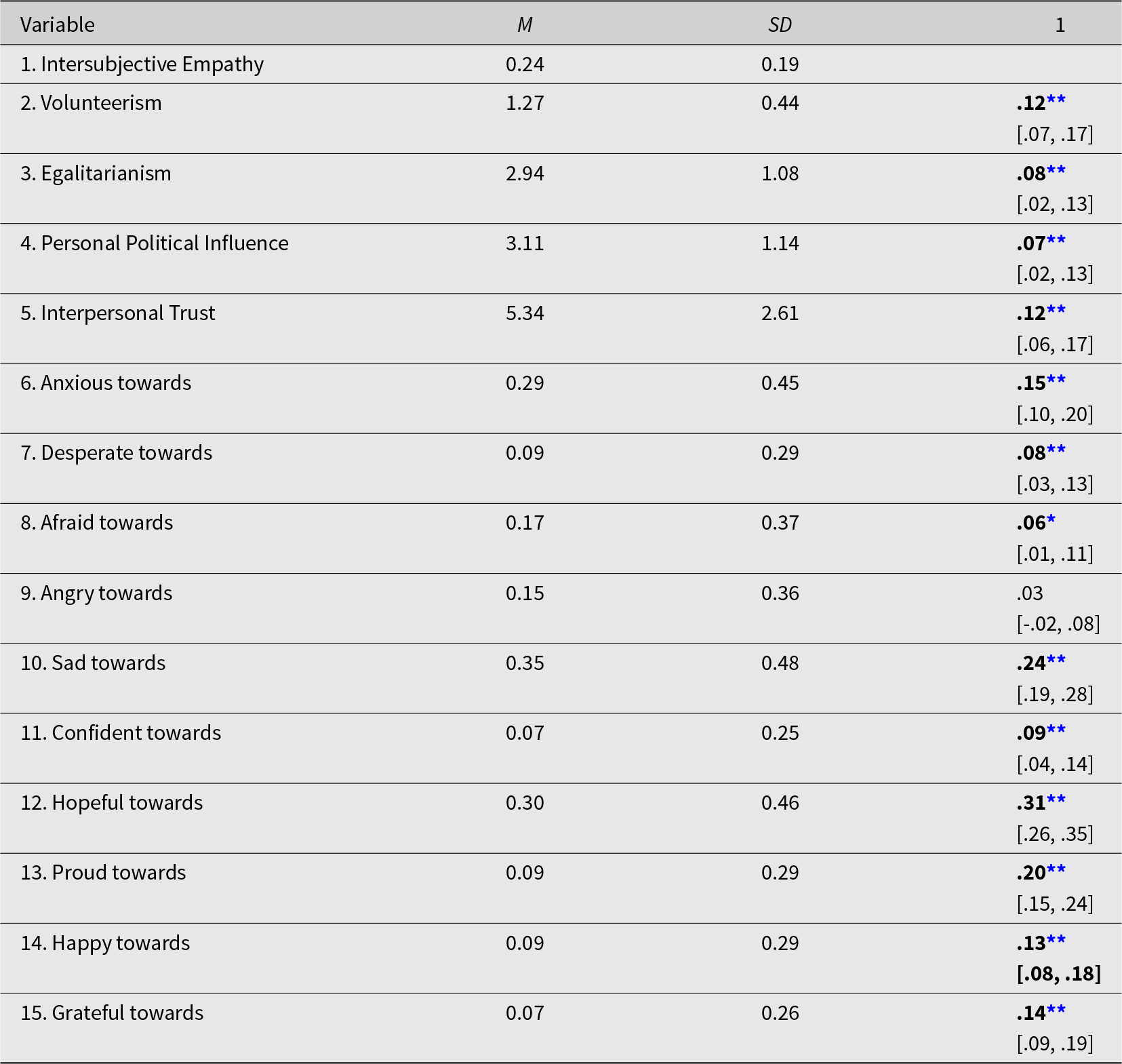

Mathematically, the formula can be represented as:

\begin{equation*}IE = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^n\left( {ei \cdot pi} \right)\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}IE = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^n\left( {ei \cdot pi} \right)\end{equation*}This formula captures the essence of calculating Intersubjective Empathy by considering the alignment of emotions selected by British citizens with those actually felt by young Syrian refugees, while also accounting for uncertainty or lack of knowledge indicated by selections of ‘Don’t know’. This weighted formulation ensures proportional relevance by reflecting the true distribution of emotions within the refugee population, making the empathy score context-specific and accurate. Secondly, it enhances precision and sensitivity, capturing subtle differences in perspective-taking. Thirdly, it avoids the pitfalls of arbitrary equal weighting seen in additive indices, instead emphasising more frequently experienced emotions. Fourthly, assigning a zero score to ‘Don’t know’ responses effectively integrates uncertainty, preventing the inflation of empathy measures. Lastly, it provides a standardised metric that facilitates consistent comparison and benchmarking across different groups and contexts, making it a reliable tool for tracking changes in outgroup empathy over time.

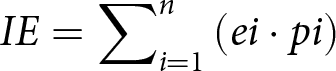

The calculated variable (n = 1,534) has a mean of .237 (SD = .195), median = .207, and a range of 0 to .682. The scores of our Intersubjective Empathy scale are shown in Figure 2. The distribution is right-skewed, and the highest density (peak) is at the lower end of the scale. Density gradually decreases as Intersubjective Empathy scores increase, with a long tail extending towards higher values. This suggests some variation, but high empathy scores are relatively rare. The density plot shows some fluctuations, indicating that there are multiple local peaks and troughs, which may suggest subgroups within the population with varying levels of Intersubjective Empathy towards Syrian refugees. Overall, this pattern supports the idea that most citizens find it challenging to accurately recognise the emotional states of Syrian refugees, likely due to a combination of social, psychological, and informational factors, which fall beyond the scope of our study.

Figure 2. Density plot of UK citizens’ intersubjective empathy towards Syrian refugees.

This pattern is hardly surprising since refugees are a ‘shadow population’. According to UNHCR, as of November 2022, there were 231,597 refugees in the UK, making up less than 0.5% of the total population. Statistically speaking, then, chances of intergroup contact that could, perhaps, foster citizens’ Intersubjective Empathy towards refugees are extremely slim. This, essentially, entails that the vast majority of citizens can only glimpse refugees’ experiences indirectly, through media portrayals and political cues, which have been shown to impact immigration attitudes.Footnote 82 Salient public representations of refugees in Western societies feature limited direct and nuanced engagement with what refugees actually experience, feel, and say, opting instead for ephemeral and sensational affective portrayals of them mainly as ‘victims or villains’.Footnote 83 Future research may fruitfully explore the extent to which media and political frames drive IE. In this paper, we are interested in its desecuritising potential, namely, IE’s hypothesised association with reduced threat perceptions at the stage of identification and an increased sense of obligation to help refugees at the stage of mobilisation.

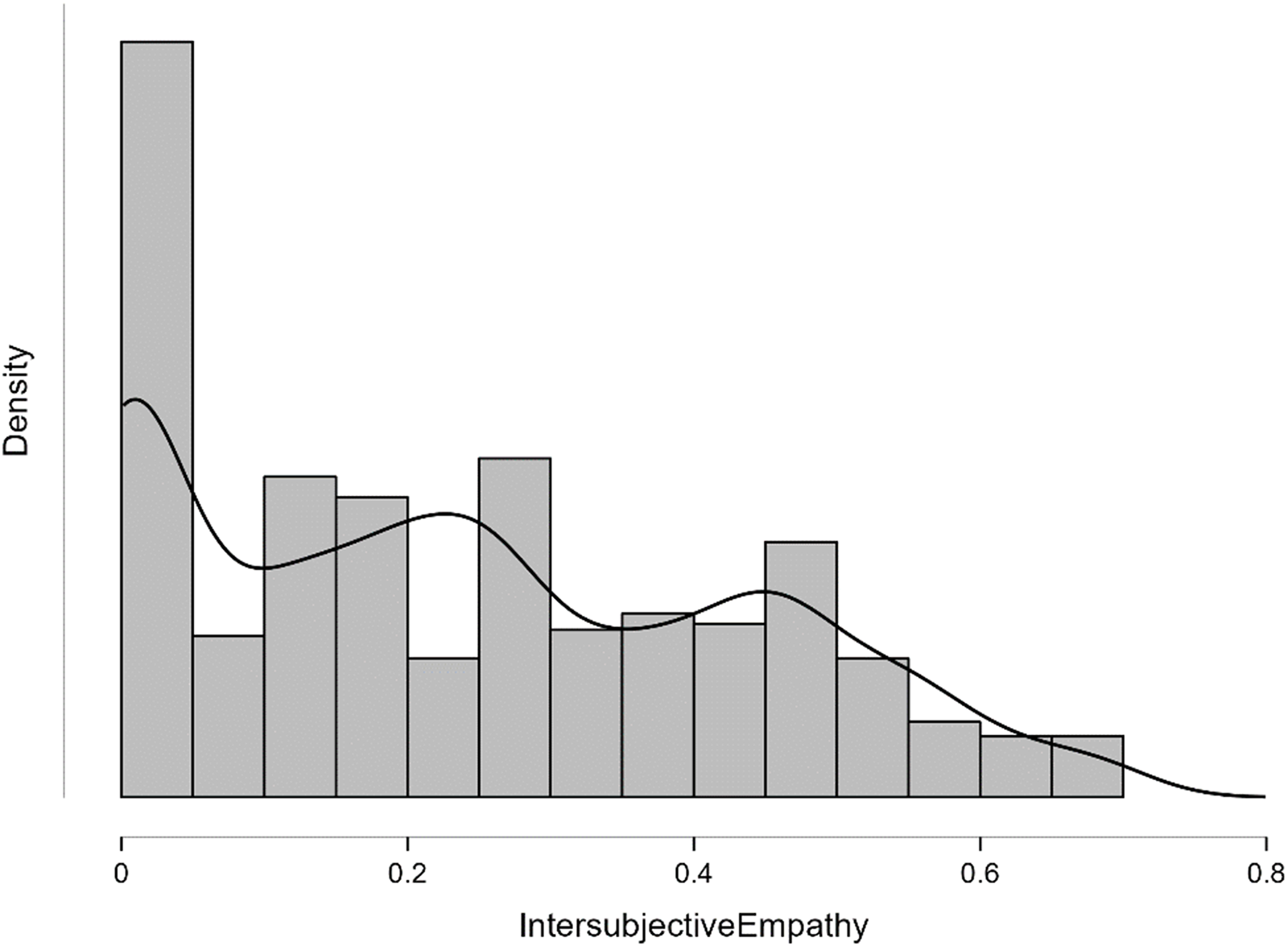

Validation of IE calls for ‘an examination of the nomological network of empirical relationships (positive, negative, and null) explicitly and implicitly theorised for that scale and its construct’.Footnote 84 We, therefore, need to explore through a series of correlations what attitudes, affects, and behaviours IE relates to, as well as ensure that it is not a stand-in for any established predictors. For our (cognitive) scale to really capture the qualities of multidimensional outgroup empathy, we would expect it to be correlated with relevant positive attitudinal, affective, and motivational components, such as prosocial attitudes, emotions, and behaviours. Table 1 presents a summary of these relationships (see full correlation matrix in the online Supplementary Materials).

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and correlations between IE and relevant affective and motivational empathy components.

Note: Values in square brackets indicate the 95 per cent confidence interval for each correlation. The confidence interval is a plausible range of population correlations that could have caused the sample correlation (Geoff Cumming, ‘The new statistics: Why and how’, Psychological Science, 25:1 (2014), pp. 7–29).

* indicates p < .05. ** indicates p < .01.

As hypothesised (H2), IE correlates with several prosocial attitudinal, affective, and motivational items, including several citizens’ prosocial emotions towards refugees. Emotions are characterised as having action tendencies,Footnote 85 meaning that they prepare us for action towards or away from an emotion-eliciting stimulus. In a review, van Kleef and Lelieveld identify various clusters of emotions – such as opportunity and affiliation, appreciation, distress, and dominance – with different tendencies towards social action.Footnote 86 Opportunity and affiliation emotions, such as happiness and hope, are often associated with prosocial behaviour.Footnote 87 With specific reference to refugees, happiness and hope have been found to predict prosocial concern.Footnote 88 Similarly, appreciation emotions, such as gratitude, are linked to increased concern for others.Footnote 89

However, we find that some negative emotions are also correlated with IE. Distress emotions, such as anxiety, desperation, fear, and sadness, have mixed effects, since sometimes distress leads us to escape uncomfortable or aversive situations while at other times it leads to prosocial intervention.Footnote 90 Feeling sadness towards refugees, for instance, is likely to motivate a desire to help.Footnote 91 Emotions associated with threat perceptions, like anxiety, fear, and desperation, predict hostility towards refugees.Footnote 92 Yet the latter can be more difficult to interpret since it can be seen in a prosocial or antisocial way. Dominance emotions, such as pride and anger, can lead to aggressive social actions, but, again, this depends on the context and the object towards which these emotions are directed.Footnote 93 For example, feeling pride towards refugees has been found to predict prosocial concern.Footnote 94 It is also important to note that anger does not correlate with IE in our study. Lastly, IE does not appear to be a stand-in for any other measure. Overall, as this rigorous assessment indicates, IE is plausible as a measure of outgroup empathy, demonstrating both prosocial affective and motivational dimensions, which are crucial for its desecuritising potential.

Attitudes towards refugees and outgroup helping: Operationalisation

For H3, we draw on the securitisation of migration literature to operationalise a multidimensional construct of public attitudes towards refugees that covers the four key axes that make up the ‘migration–security nexus’: economy, majority/national identity, public order, and national security.

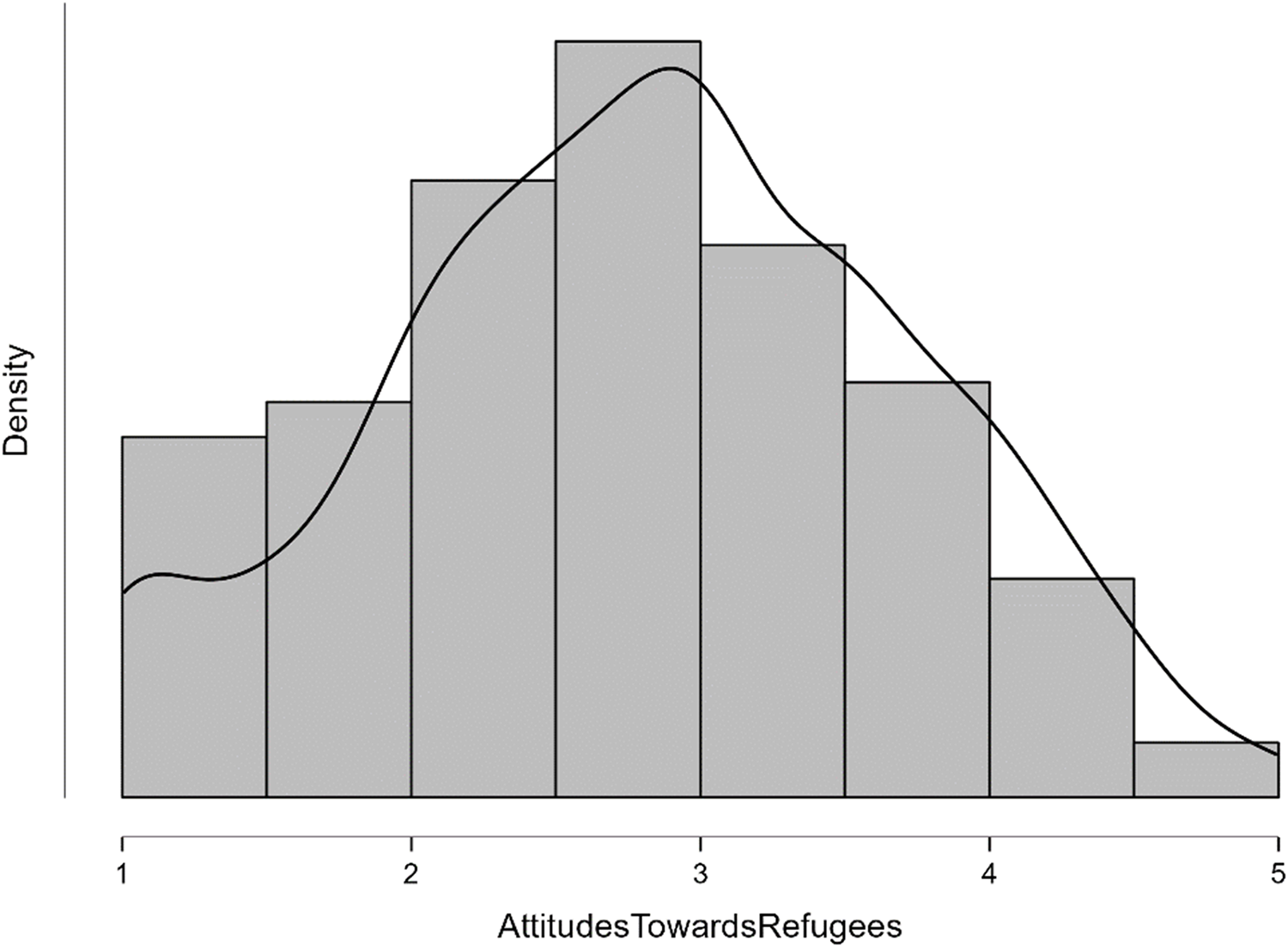

We thus constructed a scale variable, ‘Attitudes towards refugees’, which measures threat perceptions across these four key dimensions. Specifically, we asked to what extent participants agreed or disagreed with the following four statements (5-point Likert scales): ‘Refugees are generally good for the host country’s economy’, ‘Refugees increase crime rates’ (reversed), ‘Refugees are to blame for the rise of terrorism’ (reversed), and ‘How important, if at all, do you consider cultural differences are in causing any divisions between Syrians and citizens in the UK?’ (the latter using a not at all–extremely scale; reversed). The scale (Figure 3) had good reliability (α = .76). The mean score was calculated so that a higher score indicates more positive attitudes towards refugees and, thus, reduced threat perceptions at the stage of identification.

Figure 3. Density plot of UK citizens’ attitudes towards refugees.

To test H4, we consider whether IE could also be associated with public support to care for refugees at the stage of mobilisation, which is essential for successful desecuritisation. Desecuritising counter-narratives and calls for a more inclusive, humanitarian, and empathetic engagement with ‘Others’ often challenge dominant security discourses and practices. These tend to emphasise that the real threat is not refugees, but rather the intolerance and racism towards them, and, hence, the appropriate and necessary response is to stand with and care for refugees.Footnote 95 Accordingly, we used the ‘Duty to Help’ scale variable as a measure for outgroup helping. Specifically, we asked our participants ‘To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statement: Everyone has a duty to help refugees?’ (5-point Likert scale). The mean score was calculated so that a higher score indicates an increased sense of duty to help refugees. Figure 4 presents the frequencies of our outgroup helping variable.

Figure 4. Frequency plot of UK citizens’ sense of duty to help refugees (outgroup helping).

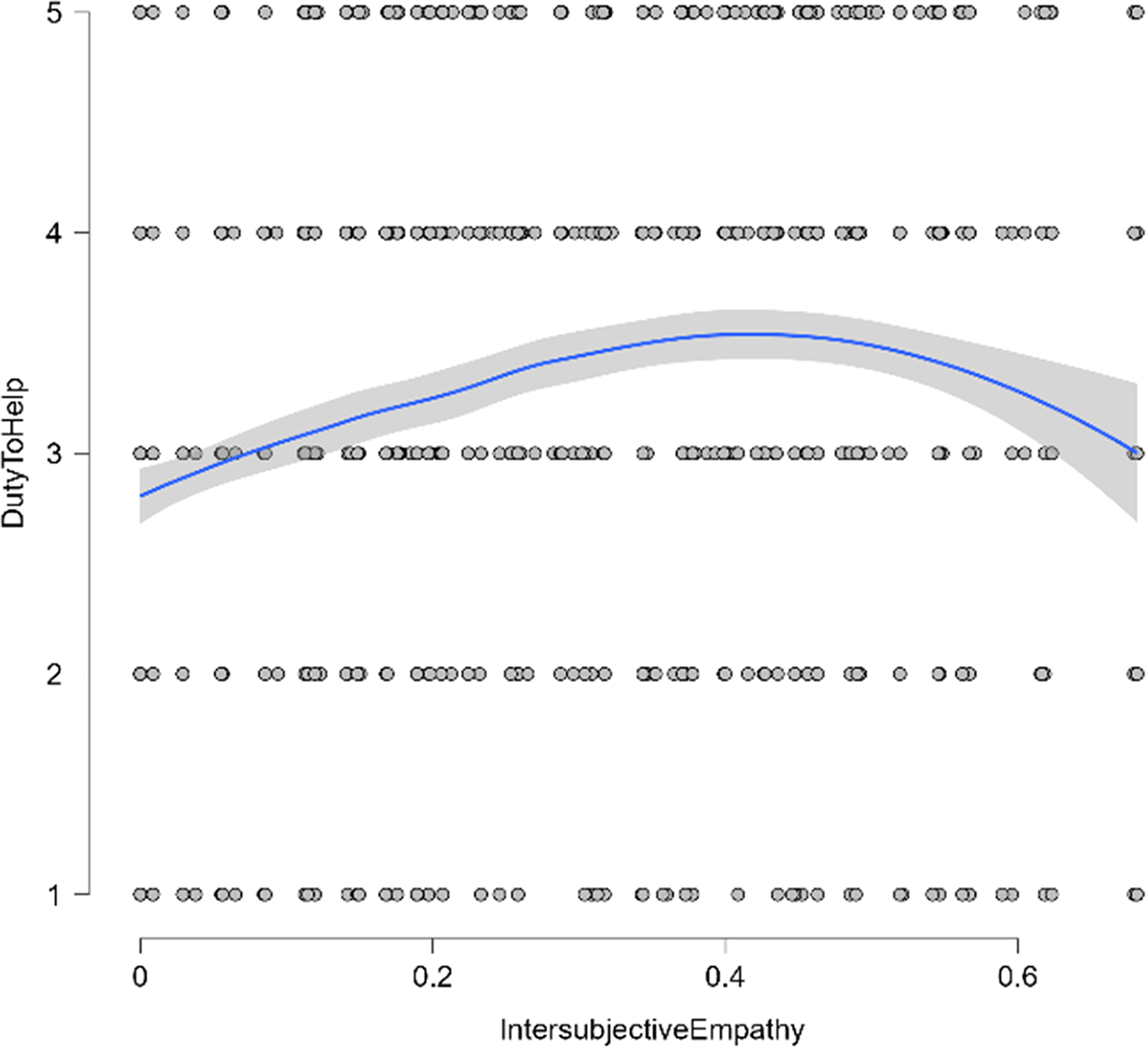

The relationship between UK citizens’ Intersubjective Empathy and their sense of duty to help refugees is visually plotted in Figure 5. The graph shows a slight positive trend, suggesting that higher levels of Intersubjective Empathy are associated with increased motivation to help outgroups. However, the relationship is curvilinear, which suggests that the impact of IE on duty to help does not increase at a constant rate. The curve peaks towards the middle range of Intersubjective Empathy and then slightly declines as IE increases further. This non-linear pattern could imply that the initial positive effects of increased Intersubjective Empathy might have diminishing returns after a certain level of IE is reached. Hence, to test H5, we include in our analysis both the linear (IntersubjectiveEmpathy) and quadratic (IntersubjectiveEmpathy2) terms. With our construct of Intersubjective Empathy validated and operationalised, we proceed to respond to our three empirical questions.

Figure 5. Scatter plot of UK citizens’ IE vs Sense of duty to help refugees.

Is Intersubjective Empathy associated with reduced threat perceptions towards refugees?

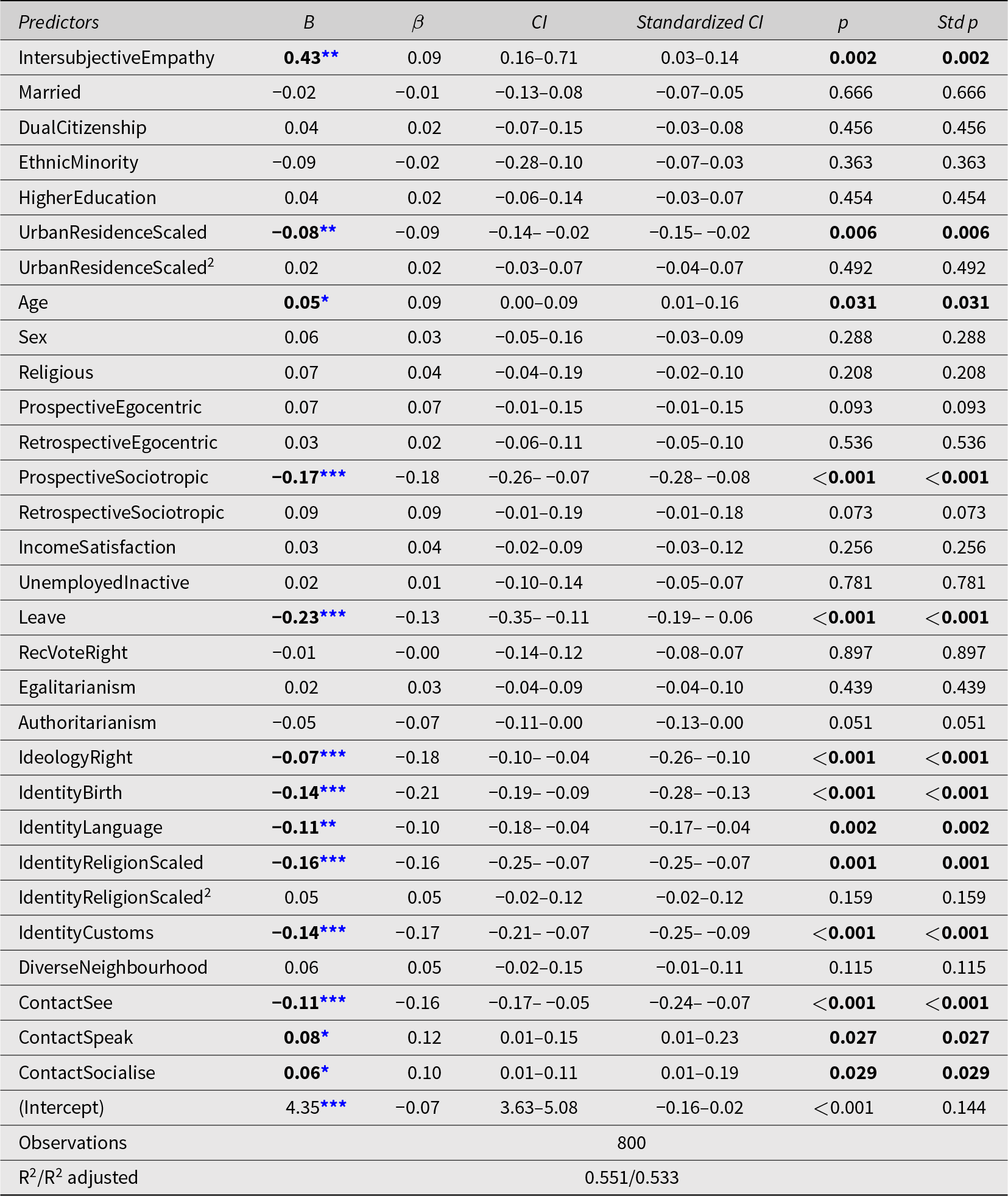

As a first test of the desecuritising potential of our construct, we explore the relationship between IE and public threat perceptions towards refugees, at the stage of identification. For reliability, we have to test the effects of IE on attitudes, controlling for most key established economic, political, sociocultural, and sociodemographic measures that have been identified in the political behaviour literature.Footnote 96 We thus ran a multiple regression analysis, controlling for sociodemographic characteristics, economic, political and ideological factors, variables associated with different conceptions of national identity, and intergroup contact factors. All assumptions for linear regression were met. Quadratic terms were added to the model to see if the model was improved using the car package in R.Footnote 97 Adding urban residence and importance of religion for British identity (IdentityReligion) as quadratic terms improved the model. The model as a whole is very strong, explaining a substantial portion of variance in attitudes toward refugees (R2 = 0.551, adjusted R2 = 0.533). IE contributes unique explanatory power, controlling for traditional sociodemographic, economic, political, and cultural predictors. Results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary of multiple regression analysis on positive attitudes towards refugees (‘stage of identification’).

* p<0.05 ** p<0.01 *** p<0.001

Results show that IE has a positive and statistically significant relationship with attitudes towards refugees (B=0.43, β=0.09, p=0.002), as per our third hypothesis (H3). Individuals who demonstrate a higher ability to recognise the emotions of Syrian refugees tend to have reduced threat perceptions towards them, indicative of the clear desecuritising potential of IE. Specifically, a one-unit increase in IE corresponds to a 0.43-point decrease in threat perceptions on a 5-point scale, controlling for all other established factors. Moving from the lowest to the highest level within the observed range of IE (0 to 0.682) results in a 0.29-point decrease in threat perceptions, further highlighting its practical significance. Compared to other factors in the model, IE has a relatively modest but statistically significant standardised effect size (β=0.09). Some factors, such as the perceived importance of having been born in the UK for British identity (IdentityBirth, β=-0.21, p<0.001), produce stronger effects on public threat perceptions. However, IE is more impactful than some established measures, such as ethnic minority status (β=-0.02, p=0.363) or higher education (β=0.02, p=0.454).

Overall, in line with our theoretically informed expectations, we find that our novel measure of outgroup empathy – Intersubjective Empathy – adds explanatory power to the model, providing a unique, additional dimension to understanding public attitudes towards refugees. While modest in size, the positive impact of Intersubjective Empathy is robust, underscoring its importance as a complementary measure that may indeed promote a reduction in public anxieties about the presence of ethnocultural ‘Others’. Simply put, citizens’ ability to recognise how refugees actually feel given their circumstances in the host society is a measure that contributes meaningfully to promoting desecuritisation at the stage of identification, controlling for many other established explanatory factors.

Our findings are also important for the broader migration attitudes literature. On average, we find that sociocultural variables – i.e. different conceptions of national identity, and quality of intergroup contact – are more closely associated with public attitudes than economic and political-ideological variables. Among these, variables related to different conceptions of national identity show the strongest associations, reaffirming their previously identified importance. Exclusionary understandings of what it means to be British, specifically the perceived importance of having been born in the UK, being able to speak English, being a Christian, and sharing British customs and traditions for British identity are strongly linked to high threat perceptions towards refugees. These findings may be a testament to the dominance of nativist narratives in public discourse in the period around the ‘Brexit’ referendum. But they may also reveal a more pervasive securitising effect of the UK’s strategy to create a ‘hostile environment’ towards asylum seekers that dates to the late 1980s.

Does Intersubjective Empathy correlate with outgroup helping?

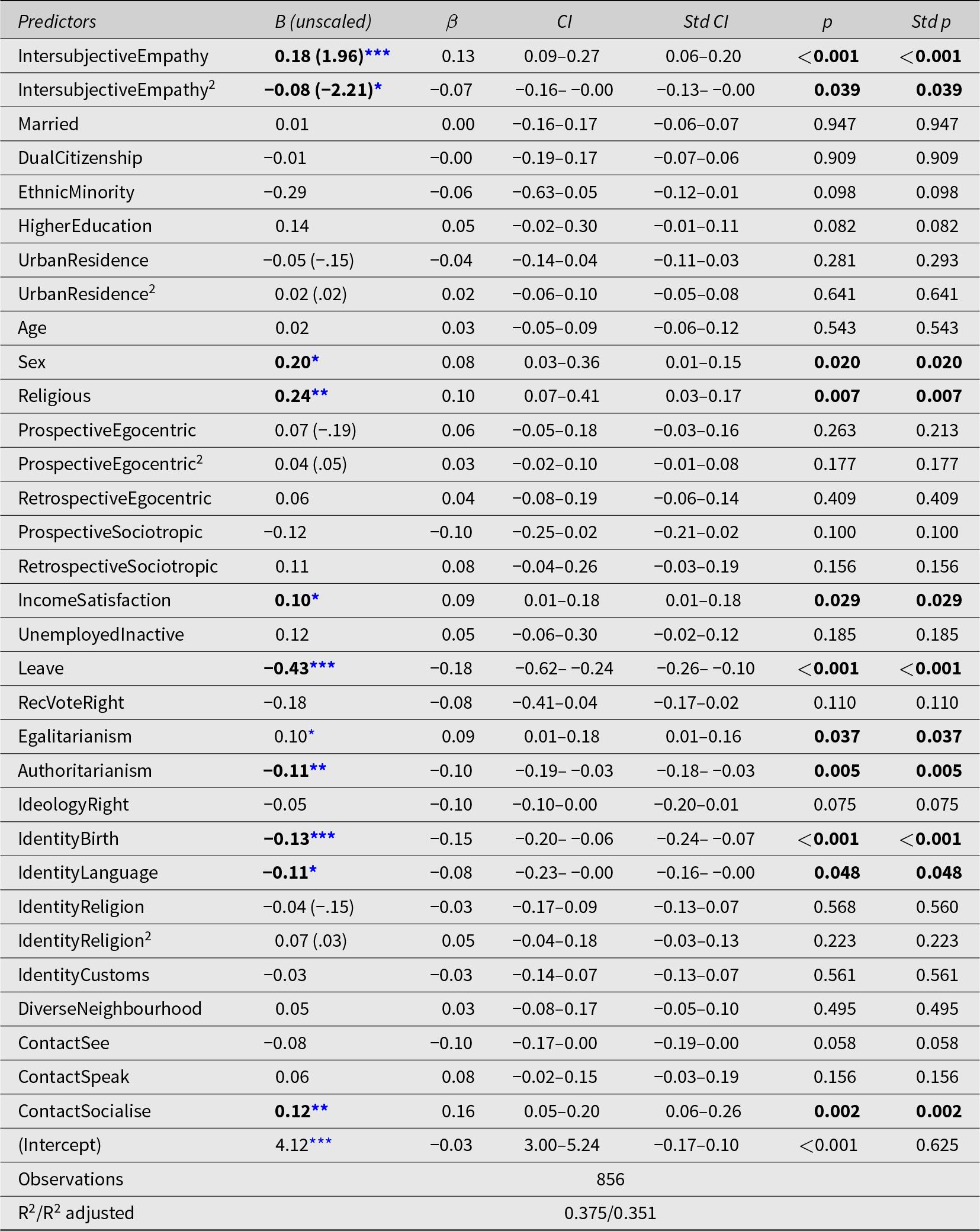

As a final test of the usefulness of our construct, we explore whether IE correlates with an increased UK citizens’ sense of duty to help refugees, which captures the motivational component of desecuritisation. Our model controls for all variables used in the previous analysis and also incorporates a quadratic term for IE (IntersubjectiveEmpathy2) to test for a potential curvilinear relationship. A linear regression model was tested with weights applied, and the addition of quadratic terms was evaluated using the car package in R. Quadratic terms were added for the following variables to improve the model fit: Intersubjective Empathy, Urban Residence, Prospective Egocentric, and the Importance of Religion for British Identity (IdentityReligion). To mitigate multicollinearity between the linear and quadratic terms, these variables were scaled prior to analysis. Scaling ensures that both linear and quadratic terms are on comparable scales and stabilises coefficient estimates. The analysis demonstrates that the model provided a good fit to the data (R2 = 0.375, adjusted R2 = 0.351; F(32, 283) = 15.45, p < .001), explaining approximately 38 per cent of the variance in motivating a sense of duty to help refugees among the audience. The coefficients for all predictors, including scaled variables and their quadratic terms, are presented in Table 3. Robust standard errors (HC3) were calculated using the sjPlot packageFootnote 98 to ensure an accurate estimation of effects.

Table 3. Summary of general linear regression analysis on outgroup helping (‘stage of mobilisation’).

* p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01 *** p < 0.001

Results show that Intersubjective Empathy (scaled; B = .18, β = .13, p < .001; unscaled B = 1.96) is indeed strongly associated with a greater sense of duty to help refugees among UK citizens, supporting our H4. However, the quadratic term for IE (scaled; B = -0.08, β = -0.07, p = .039; unscaled B = -2.21) is also significant, indicating a curvilinear relationship. This suggests that the positive association between IE and the sense of duty to help refugees diminishes at higher levels of empathy.

Specifically, moving from the lowest to the highest observed levels of IE (0 to 0.682) is linked to a predicted net increase in the sense of duty from 2.80 to 3.11. This calculation reflects the combined effects of both the linear (B = 1.96) and quadratic (B = −2.21) terms. The analysis suggests that increases in IE are linked to a stronger sense of duty to help refugees up to a breakpoint of approximately 0.44 (the vertex of the quadratic curve), beyond which further increases in empathy are associated with a decline in this perceived obligation. At the mean level of IE (0.24), the linear effect of a one-unit increase in unscaled IE is estimated to produce a 1.96-point increase, while the quadratic term introduces a modest counteracting effect at higher levels.

These findings support H5 of a curvilinear association between Intersubjective Empathy and the sense of duty to help refugees. While the overall relationship is positive, its effect diminishes as empathy increases beyond a moderate level. In simple terms, ‘too much’ IE towards refugees may reduce the perceived obligation to assist them, aligning with recent findings on the limits of empathy.Footnote 99 This highlights the normative value of moderate levels of Intersubjective Empathy in fostering a sustainable sense of duty to help, at the stage of mobilisation. Encouraging citizens to accurately recognise refugees’ emotions – without making unfounded assumptions about their experiences – could foster a more caring and compassionate public response. Providing structured opportunities for refugees to voice their actual emotions and for host citizens to engage in active listening may contribute to a more sustainable desecuritisation of asylum-seeking. Our findings indicate that such opportunities have the potential not only to reduce threat perceptions at the stage of identification but also to enhance the audience’s sense of duty to care for refugees, at the stage of mobilisation.

Identifying what specifically drives the curvilinear relationship between IE and outgroup helping is worthy of further investigation, which is beyond the scope of our paper. This relationship is further complicated by the fact that refugees expressed, in our case, predominantly positive emotions about their situation in the UK. Highly Intersubjectively Empathic citizens who can recognise these emotions may conclude that refugees are coping well in the host country and may feel less compelled to offer help, assuming it’s not needed. Another possibility is that, instead of simply assuming that help isn’t needed, these citizens may actively decide against helping because they perceive a zero-sum dynamic between refugees and their own community. Simply put, highly Intersubjectively Empathic citizens may believe that refugees’ well-being is achieved at the expense of citizens – perhaps in terms of resources, opportunities, or social cohesion – which may lead them to withhold help as a way of protecting their own group’s interests.

Indeed, perceived self-threat is the most plausible explanation as to why Intersubjective Empathy may backfire at higher levels. Self-threat arises when an ingroup is asked to take the perspective of an outgroup that is perceived to be too threatening or dissimilar to the self, when perspective-taking contradicts favourable views about the self, or when the outgroup is seen as undermining the ingroup’s self-interests, especially in competitive, ‘negative interdependent contexts’.Footnote 100 Any or all of these factors might be relevant to (de)securitisation contests, where refugees are dealt with as a multifaceted threat to host countries, due to institutionalised securitisation. As Sassenrath and colleagues succinctly put it, ‘both motivational and cognitive forces [work] to create the self-threat that hinders self-other overlap and the associated positive consequences of perspective taking’.Footnote 101

Beyond IE, demographic and socioeconomic factors also significantly shaped attitudes towards outgroup helping. Sex was a significant correlate, with females showing a higher level of duty to help (B = 0.20, β = 0.08, p = .020). Religious identification also positively influenced this sense of obligation to assist refugees (B = 0.24, β = 0.10, p = .007). Additionally, income satisfaction was found to be a significant positive influence, suggesting that individuals who are more satisfied with their income are more likely to be motivated to help (B = 0.10, β = 0.09, p = .029). Political-ideological variables had particularly strong associations, a testament, perhaps, to the highly politicised nature of the obligation to help refugees. Negative associations were observed for variables such as ‘Vote Leave’ (B = −.43, β = −0.18, p < .001) and authoritarianism (B = −0.11, β = −0.10, p = .005). As previously, sociocultural variables appear to play a significant role in shaping attitudes towards outgroup helping. Exclusionary conceptions of national identity in the sense of placing a high importance on being born in the UK (B = −0.13, β = −0.15, p < .001) and speaking English (B = −0.11, β = −0.08, p = .048) as a prerequisite for being British were linked to lower levels of the moral obligation to help refugees. In contrast, frequent socialisation with ethnocultural ‘Others’ (B = 0.12, β = 0.16, p = .002) was linked to higher levels of UK citizens’ sense of duty to help.

Overall, these findings highlight the importance of outgroup empathy, as measured by Intersubjective Empathy, in fostering UK citizens’ willingness to help refugees, a key component of desecuritisation at the stage of mobilisation. When citizens are able to accurately recognise the emotions of ethnocultural ‘Others’, they are more likely to perceive a moral obligation to assist them. However, the results also reveal a curvilinear relationship, suggesting that, beyond a certain point, further increases in Intersubjective Empathy may lead to emotional and/or cognitive overload. This, in turn, can diminish the perceived duty to help, tempering its desecuritising potential in highly polarised contexts.

Conclusion

The sociopolitical value of outgroup empathy in today’s world of increasing securitisation of migration is obvious. Yet the application of the concept to desecuritisation efforts is hindered by conceptual inconsistencies and methodological limitations. To this end, we proposed a minimalist and relational conceptualisation and measurement of outgroup empathy as the degree to which ingroup members can accurately recognise how outgroup members feel, as reported by them. We call this concept Intersubjective Empathy and position it as a potential yet contingent factor in desecuritising migration, with its effect dependent on the audience’s dual evaluations within a specific context. We show that Intersubjective Empathy is associated with the prosocial qualities and positive outcomes expected from a measure of outgroup empathy, while it avoids common problems arising from relying, predominantly, on self-report measurements across fields. Because affective and motivational components are not built into our construct, to validate it we established its association with several prosocial attitudes, emotions, and behaviours. For measurement, Intersubjective Empathy necessitates that an ingroup’s presumed perspective of an outgroup is always triangulated with that outgroup’s actual emotional state. Since ethnocultural ‘Others’ are usually rendered invisible, and their voices are often misrepresented or silenced in Western societies that host themFootnote 102 – a form of disempowerment and disenfranchisementFootnote 103 – it may not surprise us to find that UK citizens were not very accurate in recognising how Syrian refugees actually felt.

Our study reflects an understanding of securitisation as a contest, in our case involving competing messages about how threatening refugees are and what should be done about it. The audience is the ultimate judge. It also highlights the value of enriching securitisation research with interdisciplinary insights and methodologies from psychology and political behaviour, which can facilitate rigorous analyses of the dual evaluations that audiences are called to make. Results demonstrate that Intersubjective Empathy is strongly associated with reduced threat perceptions towards refugees, even when accounting for other economic, political, sociocultural, and sociodemographic factors. Providing outgroup members with opportunities to share their experiences and emotions, and making these accessible in public discourse, therefore, may support desecuritising efforts at the stage of identification. Crucially, Intersubjective Empathy is also linked to positive motivational outcomes that may encourage more inclusive public responses. This lends empirical evidence in support of Kalla and Broockman’s experimental findingsFootnote 104 that recognising another’s actual emotions and viewpoints does indeed reduce defensive reactions towards an outgroup and may also have behavioural consequences promoting more caring desecuritising responses at the stage of mobilisation.

However, the ability to recognise how ethnocultural ‘Others’ actually feel is not a panacea for desecuritising migration. Our findings suggest that the positive effects of Intersubjective Empathy on highly politicised and polarising issues, such as the moral obligation to help refugees, may have a threshold. In situations where an outgroup is framed and perceived to be a threat, engaged in a competitive ‘zero-sum game’ with an ingroup, higher levels of Intersubjective Empathy may not always mobilise inclusive responses. Instead, ingroup members may withhold support, prioritising their own group’s security and cohesion. Overall, our case study highlights the relevance of Intersubjective Empathy in understanding outgroup helpingFootnote 105 and its potential value in strategies aimed at reducing intergroup conflict, which we find is significant, albeit not immune to polarising effects at its extremes.Footnote 106

A limitation of our proposed measure is that it captures the extent to which ingroup members can accurately identify the average emotional state of an outgroup. However, each forcibly displaced person experiences refugeehood uniquely, and previous studies have found that refugees’ settlement experiences in the UK depend, among others, on their mode of access into the countryFootnote 107 and their region of settlement.Footnote 108 The simplicity of our construct, which requires just two questions administered to both ingroups and outgroups, is arguably advantageous but may also raise problems. We recognise that this approach might not always be possible and that, in some cases, including our own, there are complex practical (e.g. access and resources) and ethical considerations that must be negotiated to capture an outgroup’s emotions and attitudes accurately. However, not all securitised outgroups are equally invisible, protected, or vulnerable – and therefore hard to reach – as Syrian refugees in the UK. We hope our construct may be of use for application, testing, and refinement across fields of studies, where empathy features prominently but often promiscuously. Finally, we conclude that Intersubjective Empathy is a valuable theoretical and methodological construct that enables the accurate assessment of empathic understanding in intergroup contexts in general, and the systematic analysis of desecuritisation contests around migration in particular. This may also help understand the dynamics of (de)securitisation contests in contexts where the audience’s dual evaluations are embedded in racialised, colonial, and gendered discourses and collective memories of victimisation.Footnote 109 Its further application in Western and non-Western contexts will facilitate refined comparative evaluations of how successfully it accounts for intergroup attitudes and desecuritisation effects across cases.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/eis.2025.15.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the journal editors and anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments and invaluable suggestions. We are also grateful to Sebastian Popa, Rosario Aguilar, and all members of the Governance and Political Organisations (GPO) Cluster at Newcastle University, as well as to Ian Paterson, for their constructive feedback on earlier drafts of the paper. Finally, we extend our thanks to Giannis Maroulis, for the many discussions that contributed to the development of the concept of Intersubjective Empathy.

Dimitris Skleparis is Senior Lecturer in the Politics of Security at Newcastle University. His research focuses on how migration is governed, perceived, portrayed, and experienced amid increasing insecurities. He approaches these issues from an interdisciplinary and mixed-methods standpoint.

Georgios Karyotis is Professor of Security Politics and Co-Lead of the ‘Peaceful, Secure and Empowered Societies’ interdisciplinary research network in the College of Social Sciences at the University of Glasgow. His main research and teaching interests lie in the areas of securitisation theory, crisis management, political behaviour, and migration studies (see www.CrisisPolitics.net).

Andrew McNeill is Lecturer in Psychology at Queen’s University Belfast. A political psychologist, his research particularly focuses on how past experiences of suffering shape present intergroup attitudes and rhetoric.