Introduction

In many European states, including Germany, diversity policies have become part of the political agenda. Such policies may address societal diversity in a general sense, for instance, celebrating a city’s diversity. They may also pursue a range of more specific aims: various local, regional, and national acts, regulations, and programmes aim to ensure equal opportunities for members of different disadvantaged groups. Cities seek to make state services more accessible, offer support to victims of discrimination, and celebrate diversity weeks (Martínez-Ariño et al., Reference Martínez-Ariño, Michalis Moutselos, Jacobs, Schiller and Tandé2019). Policies include provisions against discrimination, measures to meet the specific needs of religious or ethnic minorities, and to ensure more equal access to services as well as participation in different fields, such as employment and education. Sexual and gender minorities, women, persons with a disability may be targeted, but immigrant minorities and victims of racism are often at the centre of such policies. Thus, regional states in Germany have passed laws aiming to increase the participation of immigrant minorities (Schupp and Wohlfarth, Reference Schupp and Wohlfarth2022). While references to multiculturalism have disappeared from the European political agenda, the promotion of diversity is common. We understand diversity policies here as policies that aim to increase the participation of individuals belonging to minorities or disadvantaged groups, and to publicly acknowledge and reflect the diversity in society. Such policies indicate that influential political actors at the national and the EU levels (Swiebel, Reference Swiebel, Prügl and Thiel2009) increasingly recognize the socio-cultural diversity of society and the legitimacy of demands for respect and equal participation. But to what extent do such policies also enjoy the support of the population? Surprisingly, we know very little about this.

We lack wide-ranging studies, but existing research has identified human rights law, the pressure from minority rights advocates, and the wish to prevent conflicts as factors driving legislation (Cole, Reference Cole2005; Skrentny, Reference Skrentny2006; Celis et al., Reference Celis, Lena Krook and Meier2011; Sabbagh, Reference Sabbagh2011). Public opinion is not discussed much in this context. And yet, public opinion surely matters. Scholars have described the opinion-policy linkage as complex; policies apparently tend to conform with political opinion, although not in all cases (Burstein, Reference Burstein2020: 89; Rasmussen, Reference Rasmussen2019: 331, 335; Romeijn, Reference Romeijn2018). Politicians may feel inhibited or encouraged to pursue a particular course of action by what they perceive to be public demands (Senninger and Seeberg, Reference Senninger and Seeberg2024). Surely, marriage rights for same-sex couples would hardly have been granted without some level of public support (Ahrens et al., Reference Ahrens, Ayoub and Lang2022: 5; Hadler and Symons, Reference Hadler and Symons2018). Lack of public support may endanger the legitimacy of a policy. For civil society actors pushing for increased anti-discrimination and pro-minority measures, the extent and structure of support for such measures are important factors to consider. And yet, knowledge about public support for diversity policies is very limited, particularly in European countries. With reference to multiculturalism policies, some scholars argue that they are essentially an ‘elite project’ (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Johnston, Citrin and Soroka2017: 104) or, at least two decades ago, suffered from a ‘chronic lack of public support’ (Joppke, Reference Joppke2004: 237). However, evidence is scarce. A number of scholars have recently expressed their discontent with the state of research on popular support for an inclusive, multicultural, or diverse society (Dennison and Geddes, Reference Dennison and Geddes2019; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Schönwälder, Petermann and Vertovec2023; Tyrberg, Reference Tyrberg2024: 19). A range of studies on general attitudes toward immigration exists (e.g., Dražanová et al., 2024; Heath et al., Reference Dražanová, Gonnot, Heidland and Krüger2024), but less is known about views on societal diversity in general, and specifically the political consequences of diversification. More insights into the extent and contributing factors of support for policies aiming to acknowledge societal diversity and ensure equal participation for disadvantaged groups are urgently needed. Thus, Ivarsflaten and Sniderman (Reference Ivarsflaten and Sniderman2022: 10, 44) have called for more scholarly efforts to understand the conditions under which citizens in democracies support an inclusive society. As they emphasize, we find ‘a broad willingness to accept paths forward toward more inclusive societies’ in many European states, ‘a permissive coalition, a willingness to go along with inclusion’, but not necessarily consensus about interventions to ensure more equality and participation. Political science, in particular, should investigate responses to different policy options as existing research, in their view, does not offer much ‘regarding the acceptance of interventions aiming to shape a fair society’. Referring to multiculturalism, scholars contend that even for North America ‘relatively little is known about public attitudes towards (and support for) specific […] policies’ (Stolle et al., Reference Stolle, Harell, Soroka and Behnke2016: 336; see also Wright et al., Reference Wright, Johnston, Citrin and Soroka2017: 112). Scarborough and colleagues (Reference Scarborough, Lambouths and Holbrook2019: 195) lament a similar knowledge gap for diversity policies, despite the existing considerable body of research on public support for affirmative action in the USA (Krysan, Reference Krysan2000; Peterson, Reference Peterson1994). For Europe, research is still more limited. Even for the widely propagated workplace diversity policies, scholars have only recently begun to investigate their acceptance by the general public (Blommaert and Coenders, Reference Blommaert and Coenders2024).

This article contributes to an emerging scholarship in Europe in two main ways. First, we provide empirical insights into public support for diversity policies, here defined as policies that aim to increase the participation of individuals belonging to minorities or disadvantaged groups and to publicly acknowledge and reflect the diversity in society. Such policies may address diversity in an unspecified way or include measures targeting specific groups. We investigate support for general policies and for policies targeting immigrants specifically. Additionally, one question relates to gays and lesbians. We do this for German urban contexts, drawing on a survey with close to 3,000 respondents. Empirically, we assess support across a broad range of issues commonly addressed by diversity policies, such as political representation, the public sphere, cultural policies, education, and employment. In doing so, we substantially contribute to a better understanding of citizens’ support for common public policies. We demonstrate that public support for such policies is considerable, albeit uneven, in Germany. Second, we make a theoretical contribution to a deeper understanding of public support for policies aiming to increase equality and participation by exploring the patterns of such assent and its correlates. We find that such support is not driven by group interest, as assumed in previous studies. Rather, intergroup contact and general egalitarian views are strongly associated with support for diversity policies.

Diversity policies: concept and state of knowledge

The concept

Our concept of diversity policies, as used in this article, is related to, but not identical with, concepts of affirmative action policies or multiculturalism. Policies referred to as affirmative action, diversity, or multiculturalism policies partly overlap, and usage of such terms varies in the scholarly literature. If affirmative action policies are understood more narrowly as policies that ‘allocate scarce resources so as to remedy a specific type of disadvantage, one that arises from the illegitimate use of a morally irrelevant characteristic’ (Sabbagh, Reference Sabbagh2011: 109), they have a narrower scope than diversity policies, but may form part of them (but see King, Reference King2007: 110 with a wider definition). The concept of multiculturalism policies is broader in policy aims than that of affirmative action policies and differs regarding the target group, as it mainly focuses on ethnic and immigrant minorities rather than, for example, women. Introduced by Banting and colleagues (Reference Banting, Kymlicka, Johnston, Soroka, Banting and Kymlicka2006: 52, 56), it relates to ‘policies of public recognition, support, and accommodation’ for immigrant minorities, historic national minorities, and indigenous peoples. The key term ‘recognition’ adds an element that is not prominent in affirmative action, while ‘accommodate’ allows more modest interventions than the corrective justice intended with affirmative action.

While policy aims overlap across different concepts, we use a concept not restricted to ethnic or immigrant minorities or the ‘corrective justice’ motivation of affirmative action. Diversity policies can broadly be understood as policies that aim to increase the participation of individuals belonging to minorities and disadvantaged groups, and to publicly acknowledge and reflect the diversity in society. Like affirmative action policies (King, Reference King2007: 110), they potentially include a range of discrete interventions, such as regulations ensuring that public resources are allocated fairly, that services serve everyone, equal employment initiatives, initiatives aiming to increase political representation of underrepresented groups, funding for minority activities, support for (potential) victims of discrimination, public acceptance of minority rights and diversity, and campaigns for an inclusive and fair society.

Public support

What do we know about levels and structure of public support for such interventions? As pointed out above, existing scholarship is patchy. For multiculturalism policies, scholars have assumed a lack of public support, but evidence is scarce (Joppke, Reference Joppke2004: 237; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Johnston, Citrin and Soroka2017: 104). Surveys in Europe have rarely included a larger battery of relevant items, thus, to our knowledge, no broader comparative studies on levels and structure of public support across different policies exist. Older studies have used the broad items provided by the European Social Survey (ESS) and the German Allbus, asking (in similar phrasings) whether ‘foreigners’ or ‘people who have come to live here should be given the same rights as everyone else’ (Gorodzeisky and Semyonov, Reference Gorodzeisky and Semyonov2009; Scheepers et al., Reference Scheepers, Gijsberts and Coenders2002; Wasmer and Koch, Reference Wasmer, Koch, Alba, Schmidt and Wasmer2003). Results provide empirical support for studying attitudes to allocating rights in a country as distinct from attitudes to the admission of immigrants (Gorodzeisky and Semyonov, Reference Gorodzeisky and Semyonov2009). Another set of influential studies has focused on gender equality (Kane and Whipkey, Reference Kane and Whipkey2009), often looking specifically at support for gender quota in political and economic life (e.g., Barnes and Córdova, Reference Barnes and Córdova2016; Möhring et al., Reference Möhring, Teney and Buss2019). Based on data for a range of Latin American countries, Barnes and Córdova (Reference Barnes and Córdova2016) emphasized the impact of general government performance and political values, specifically support for government involvement in citizens’ well-being, over and beyond individual-level mechanisms.

Three main observations are widely shared in the existing literature. They relate to affirmative action, multiculturalism, and diversity policies, but for the time being, we assume that they are of potential relevance to all these policies. Altogether, scholars have argued that popular attitudes are incoherent. Two specific aspects of such incoherence have been emphasized. First, people may be in favour of equality more generally, but not support measures designed to ensure such equality: ‘One long-standing puzzle in the study of racial attitudes is the discrepancy between white Americans’ widespread support for abstract principles of racial equality and their failure to endorse specific policies designed to ameliorate racial inequalities’ (Jardina and Ollerenshaw, Reference Jardina and Ollerenshaw2022: 577; see also Krysan, Reference Krysan2000: 140). The idea that a gap exists between support for the principle of equality and for measures to achieve it has been taken up for non-USA contexts as well (see, Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Durrheim and Thomae2017 for South Africa). However, recent research finds that significant parts of the American public now do support ‘racial equality in both principle and, to some extent, in practice’ (Jardina and Ollerenshaw, Reference Jardina and Ollerenshaw2022: 585). Hence, the gap between principle and practice may not be a general and stable feature of public opinion, but contingent.

Second, scholars observed incoherence in that, across different measures, levels of support vary (Krysan, Reference Krysan2000: 137). For European contexts, this has been noted in studies of public support for anti-discrimination policies (Verhaeghe et al., Reference Verhaeghe, Martiniello and Bourabain2023 for Flanders) and of attitudes toward the Muslim presence (Carol et al., Reference Carol, Helbling and Michalowski2015). Statham (Reference Statham2016) found that the views of Muslims and non-Muslims on different items varied, and in ways not easily explained (see also Blinder et al., Reference Blinder, Ford and Ivarsflaten2019). As Carol and colleagues (Reference Carol, Helbling and Michalowski2015: 666) suggest, future research should focus on a larger and broader range of rights to investigate this further.

Third, several studies, not only in North America, have found specific socio-demographic groups to be more supportive of diversity policies than others. Scholars have shown that women are more likely than men to support diversity or affirmative action policies (Crosby et al., Reference Crosby, Iyer and Sincharoen2006: 596; Fernández and Valiente, Reference Fernández and Valiente2021: 360; Scarborough et al., Reference Scarborough, Lambouths and Holbrook2019: 207; Teney et al., Reference Teney, Pietrantuono and Möhring2023). Further, ethnic or racially defined groups have been found to support such policies in greater shares than others (Scarborough et al., Reference Scarborough, Lambouths and Holbrook2019: 207; Stolle et al., Reference Stolle, Harell, Soroka and Behnke2016: 350). Teney, Pietrantuono, and Möhring (Reference Teney, Pietrantuono and Möhring2023) find that belonging to a disadvantaged group increases support for employment-related affirmative action, especially, but not exclusively, for one’s own group.

Explaining support for policies

Scholars have struggled to make sense of the perceived incoherence of views or identify mechanisms. Some have suggested that public support is larger when proposals are more general – rather than very specific, when policies do not involve major expenses or are merely symbolic (Stolle et al., Reference Stolle, Harell, Soroka and Behnke2016: 350; Verhaeghe et al., Reference Verhaeghe, Martiniello and Bourabain2023: 260–1; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Johnston, Citrin and Soroka2017: 113). Others point to more fundamental roots of varying support for different interventions. In a polarized USA debate such fundaments are – in sometimes unnecessary juxtaposition – located in ‘symbolic racism’ or ‘key nonracial values and principles’ (Banks and Valentino, Reference Banks and Valentino2012; Krysan, Reference Krysan2000: 148). Indeed, fundamental beliefs or values have been shown to correlate with attitudes to immigration (Petermann et al., Reference Petermann, Schönwälder and Harris2025). For the USA, empirical studies have shown that attitudes to race equality or diversity policy may be related to egalitarianism, beliefs about justice and social stratification, as well as to attitudes to politics of equality (Sniderman et al., Reference Sniderman, Crosby, Howell, Sears, Sidanius and Bobo2000). Theoretically, attitudes to diversity policy are then understood as driven by more fundamental dispositions towards social justice and state intervention. Empirically, perceptions of existing injustices, strong egalitarian beliefs, and some other general political views have been found to be associated with attitudes to diversity (multiculturalism, affirmative action) policies (Barnes and Córdova, Reference Barnes and Córdova2016: 672–3, 684; Krysan, Reference Krysan2000: 147–8; Möhring et al., Reference Möhring, Teney and Buss2019: 136–7; Scarborough et al., Reference Scarborough, Lambouths and Holbrook2019: 196). It is indeed plausible that, for instance, equal chances for minorities find more support among those who generally believe that the government should advance equality and support the disadvantaged. A person who believes injustices exist and are deplorable may be more likely to support measures aimed at correcting such injustices. On the other hand, interventions may be seen as violating meritocracy and possibly opposed for that reason (Krysan, Reference Krysan2000: 149–150). Factors driving views concerning diversity policies may vary across countries. After all, perceptions of disadvantage and views on fairness or equality – principles possibly driving different attitudes – differ across countries, as do views concerning state intervention (Guillaud, Reference Guillaud2013; Heuer et al., Reference Heuer, Lux, Mau and Zimmermann2020) as well as attitudes to the minorities concerned.

H1: Awareness and critique of social inequality and discrimination are positively associated with support for diversity policies.

Apart from equality-related views, several scholars see attitudes to diversity policies as driven by self or group interests. For women, as well as for ethnic and racial minorities, it is widely assumed that their higher support for diversity policies is motivated by self-interest, that is, the expectation of benefiting individually or as a group from the measures in question (Barnes and Córdova, Reference Barnes and Córdova2016: 672; Scarborough et al., Reference Scarborough, Lambouths and Holbrook2019: 207; Stolle et al., Reference Stolle, Harell, Soroka and Behnke2016: 350). Theoretically, this argument is based on the premise that individuals see themselves as belonging to a specific group and, through this mechanism, share an interest in the policies in question. Further, it is often assumed that such group consciousness extends to solidarity with other disadvantaged groups.

Although common, the theoretical assumption that group membership drives policy attitudes has not remained unchallenged. Indeed, Lee (Reference Lee2008: 458) has called for closer investigation and theoretical reflection of this ‘identity-to-politics link’, that is, the premise ‘that individuals who share a demographic label […] will also share common political goals and interests and act in concert to pursue them’. Problems in many analyses included the external ascription of group belonging to individuals whose subjective belongings are unknown and may well be inconsistent (Lee, Reference Lee2008: 463). Group belonging needs to be part of individual identifications to become a motivating force for political views; subjectively perceived common interests should not simply be assumed. Such limitations need to be reflected when interpreting results of survey analyses that provide us with limited data on the complex identity-to-politics link. When formulating the following hypothesis, we are aware of missing information on subjective identifications, a problem we will get back to in interpreting the results. Still, we expect to produce results that lend support to the assumption of group interest as a driver of support for diversity policy for the German context.

H2: Having a migration background or being a woman is positively associated with support for diversity policies.

In addition to holding specific views and belonging to a disadvantaged group, a third set of factors may impact attitudes to diversity policies. Following Bolzendahl and Myers (Reference Bolzendahl and Myers2004), we refer to them as exposure-related factors. The underlying theoretical assumption is that exposure to difference and a plurality of ideas and cultural practices potentially fosters acceptance of diversity. Such attitudes are assumed to be flexible, not mainly determined by early socialization (but see Kustov et al., Reference Kustov, Laaker and Reller2021; Scott, Reference Scott2022). First, education, often shown to impact attitudes to minorities and immigration (e.g., Dražanová et al., Reference Dražanová, Gonnot, Heidland and Krüger2024), as well as to gender equality (Bolzendahl and Myers, Reference Bolzendahl and Myers2004), can be seen as exposure to a range of ideas. Second, given the progressive diversification of many societies, different age cohorts were exposed to different societal contexts during their lives, potentially affecting their attitudes and leading to age differences (see also Dražanová et al., Reference Dražanová, Gonnot, Heidland and Krüger2024: 321). Third, the size of a city in general implies exposure to more or less diverse contexts. Big cities are typically not only more diverse but also more likely to implement a range of diversity policies (Martínez-Ariño et al., Reference Martínez-Ariño, Michalis Moutselos, Jacobs, Schiller and Tandé2019), exposing their residents to this experience. And last, but not least, intergroup contact can be understood as even more direct exposure to difference. Numerous studies have now shown the positive effects of such contact on attitudes to others, with empathy being a main mechanism (Pettigrew et al., Reference Pettigrew, Tropp, Wagner and Christ2011; Schmid et al., Reference Schmid, Al Ramiah and Hewstone2014; Schönwälder et al., Reference Schönwälder, Petermann, Hüttermann, Vertovec, Hewstone, Stolle, Schmid and Schmitt2016: 171–205). It remains to be seen whether such correlations can also be observed with regard to policy interventions.

H3: Exposure to a plurality of ideas and cultural practices, specifically through higher education, age-specific life experiences, big city-contexts, and intergroup contact is positively associated with support for diversity policies.

Building on existing scholarship, our analysis will test three influential assumptions about drivers of support for diversity policies, namely that general political views on equality and disadvantage, membership in disadvantaged socio-demographic groups, and exposure to difference and plurality, are associated with supportive attitudes to diversity policy. We also show levels of support for such policies. Results are presented after the following section, which describes the dataset and details our empirical strategy for the analyses.

Data, operationalization and methods

In this paper, we exploit a unique dataset on support for societal diversity among the general population in Germany – the Diversity Assent Survey (DivA).Footnote 1 This survey measures the social experience and perception of diversity, as well as attitudes towards possible political consequences. It does so to fill a specific gap: while much past social science research focuses on understanding determinants of hostility towards minority groups, little research and data exist on what motivates those who support a diverse society. The specific items and measurements we use are described in more detail below.

Data

The survey was conducted with a professional company, Kantar, and administered by telephone between November 2019 and April 2020 on a random sample of 2,917 respondents through a dual-frame strategy mixing landlines and mobile numbers (for a similar strategy see the German survey on voluntary engagement, Simonson et al., Reference Simonson, Kelle, Kausmann and Tesch-Römer2022). Full technical details are available in a dedicated report (Drouhot et al., Reference Drouhot, Petermann, Schönwälder and Vertovec2021).The sample was drawn in twenty randomly selected German cities with at least 50,000 inhabitants. We relied on a stratified sampling strategy that considered population size and share of foreigners. The survey targets a population likely to have experienced diversity, namely those living in cities. Respondents include individuals aged 18 years and older with different migration backgrounds and citizenship. The survey could be answered in German, Turkish, Russian, and English to maximize immigrant participation. For the multivariate analyses, we use data for 2,826 respondents (more than 96% of the sample) to have full information across all variables of interest. In parts of our analyses, we calibrate our estimates with design and post-stratification weights using rich data from the Mikrozensus, the major official annual household survey conducted by statistical offices in Germany.Footnote 2 Weighted results are representative of adults living in German cities with at least 50,000 inhabitants.

Operationalization

The survey includes a large battery of questions regarding support for diversity-related interventions. Here, we use eight items that all relate to whether and how societal institutions and the distribution of resources should reflect diversity (see Table 1). Some items refer more generally to diversity, while others concern immigration, and one allows comparing views on a sexual minority.

Table 1. Diversity policies, dependent variables

Items cover typical areas of diversity policy: political representation (diverse parliaments), public services (schools, employment), and public expenditure. A question on mosques addresses the public presence of minorities. Three of our items relate to support for the ‘specific needs’ of selected minority groups (Muslims, refugees, gays, and lesbians). Arguably, policies aiming to ensure recognition for minorities, as well as a more equal distribution of public resources, will, at least sometimes, need to address the specific needs of minorities.

To arrive at more valid estimates of support for such policies, we used different question formats. Some use a common five-point scale ranging from strong agreement to strong disagreement. Here, often a relevant share of respondents choose the middle option (teils-teils/neither agree nor disagree) and thus avoid a clear statement (Sturgis et al., Reference Sturgis, Roberts and Smith2014). We thus, in addition, use so-called forced-choice questions that do not offer a middle option, but invite respondents to choose between two views that are both presented as equally legitimate. Third, the survey includes a set of items asking respondents whether they regard support for a specific minority as insufficient, sufficient, or excessive. Again, a decision is demanded of respondents, although they can refuse to answer.

We recoded, where necessary, variables into dummy variables to ease the comparison of results. Answers to items concerning support for specific minority groups were recoded as 1 if respondents claim that ‘too little is being done’ or ‘enough is being done’, and 0 otherwise. We thus interpret the opinion that ‘enough is being done’ to meet the specific needs of a group as support for such measures. We throughout treat both ‘Don’t know’ answers and non-responses as absent support for the proposal.Footnote 3 This enables us to identify those who explicitly support diversity policy.

We test to what extent three more general, equality-related political views are associated with support for diversity policies. As explained above, previous research indicates that awareness of existing inequalities and discrimination is associated with a greater likelihood to support measures aiming to address such social ills. Further, individuals who believe that social inequality is problematic are expected to be more supportive of measures aimed at ensuring more equal participation. Awareness that discrimination is a problem is tested with the statement ‘Now a question on cases of discrimination, for example against homosexuals or dark-skinned people. Do you think the media should report more about cases of discrimination? OR Do you think the media should report less about cases of discrimination?’ Perspectives on inequality are operationalized using two statements. One represents an egalitarian critique of an unequal society: ‘The existing inequality in our society is not alright, because it is a result of unequal opportunities’. The other describes social inequality as a problem requiring public intervention: ‘Our society should ensure that differences in living standards are reduced’. Survey respondents were invited to indicate their agreement or disagreement with each of these three statements on a 4-point scale (without a middle option), which we recoded into dummy variables. ‘Don’t know’ answers and non-responses were again treated as non-agreement.

To assess the relevance of assumed self-interest, we test the influence of being female, and of having a migration background.Footnote 4 Both are dummy variables.

Exposure-related factors summarize conditions potentially affecting attitudes as individuals are exposed to relevant experiences and information. We focus on the following four factors. Education is a categorical variable where the lowest category refers to nine years of schooling or less, the highest category to the diploma qualifying for university (Abitur) or having a university degree, and the middle category to all other school degrees. The latter is the reference category in the regression analyses. We distinguish four age groups (18–24, 25–44, 45–64, 65+), with 45–64 years as the reference category in the regression analyses. To test whether city size has an impact, we distinguish between big (100,000 or more inhabitants) and mid-size (between 50,000 and 99,999 inhabitants) cities. Intergroup contact measures whether a person has daily or at least weekly contact to someone with or, respectively, without a migration background (for descriptive statistics for all variables included in the main analysis see online Appendix A, Table 1).

Methods

To test how selected views, self-interest and exposure to difference influence support for diversity policies, we require a regression method that is suited to dealing with a binary outcome variable. We therefore estimate a linear probability model (LPM), which, unlike non-linear models, enables us to compare coefficients across models (Angrist and Pischke, Reference Angrist and Pischke2008) and facilitates the interpretation of our results (Mood, Reference Mood2010). Importantly, there are no of out-of-range predictions, except for the model estimating views on public service recruitment where it is 1.5%. To ensure the robustness of our findings, we replicated all analyses using logistic regressions and were able to reproduce all the results (see online Appendices A and B).

Results

Levels and structure of support for diversity policies

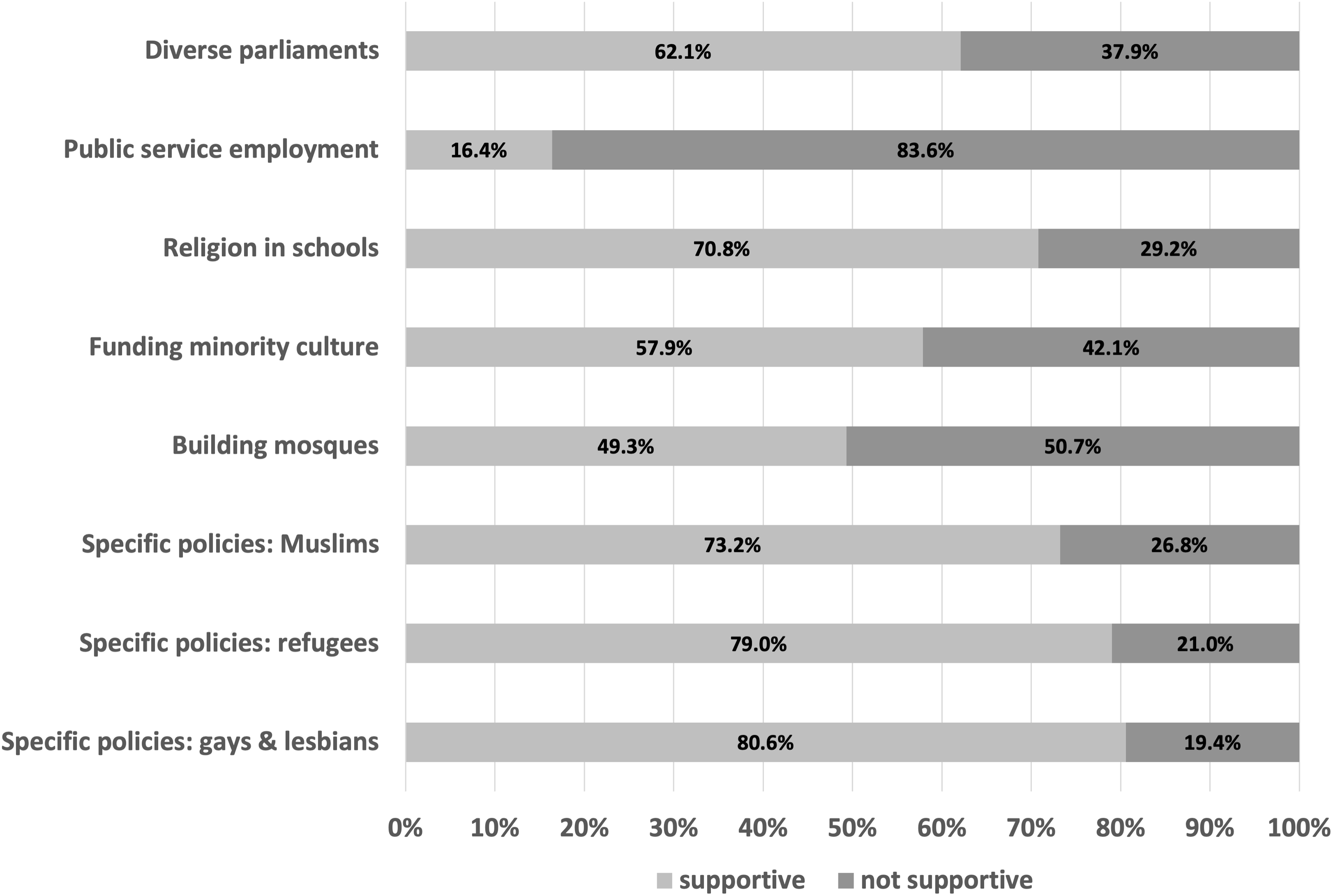

We begin by discussing descriptive results to explore the extent and structure of support for diversity policies (see Fig. 1). Residents of German cities are altogether supportive of diversity policies. Descriptive analyses for the eight items examined here show high, albeit differing levels of support.

Figure 1. Attitudes to diversity policies.

Note: For exact question wordings, see Table 1. Percentages are weighted; n = 2,917. ‘Not supportive’ includes disagreement, neither nor and no answer. Source: DivA-Survey 2019–20.

Looking at general policies, we find that, at 62%, agreement is high for diverse parliaments, followed by 58% for public funding for minority cultural activities, and 49% for the right to build mosques. For the latter item, clear opposition is more pronounced at 26%. All three proposals have far more supporters than clear opponents. A significant share of respondents, 25% to 31%, avoid a clear statement.

Respondents are overwhelmingly in favour of representing all religions equally in school teaching, with only about a quarter demanding preferential treatment for Christianity. This is despite 60% of survey respondents identifying as Christians. Most urban Germans are apparently in favour of religious plurality in public institutions. This is to a lesser extent true if Islam specifically is the focus (right to build a mosque), but even then, a public presence of the minority religion is supported by about half of the sample.

Respondents are also overwhelmingly willing to accept public support for measures addressing the specific needs of selected groups. Large shares accept existing measures to support minorities by choosing the answer that ‘enough’ or ‘too little’ was being done in Germany to meet the ‘specific needs’ of refugees, Muslims, and gays and lesbians. Again, we see an anti-Muslim bias here with more limited calls for extended support, but here as well, supportive measures are generally accepted. Although one might expect considerable opposition to measures benefitting just small groups, only a fifth of the sample (21%) wanted such support for at least one of the groups to be reduced.

Scepticism dominates when it comes to interventions in recruitment to the public service. This item was the most controversial among those tested. Only 16% of respondents agreed that care should be taken to raise the share of previously disadvantaged groups. In contrast, 84% found that exclusively suitability and competence (Eignung und Befähigung) should matter in recruitment to the public service. We do not know the motivations of the respondents, but different considerations may be involved. Employment could be a particularly sensitive matter, as respondents may see their own opportunities affected. Further, they may be of the opinion that decisions on the basis of suitability and competence will lead to fair outcomes. As Bohmann and Liebig (Reference Bohmann and Liebig2022: 100) report, Germans are more likely than other European populations to believe that everyone in their country has a fair chance to get their preferred job. Further, the pro-diversity option in our survey question suggests a change of the present situation (‘raise the share’), and people may be averse to change. This interpretation is supported by a finding reported by Ivarsflaten and Sniderman (Reference Ivarsflaten and Sniderman2022: 75). Here, people were more supportive of the proposal that textbooks should be written to reflect societal diversity than of the idea that they should be rewritten. A preference for continuity may also partly explain relatively high support for the view that ‘enough’ is being done to support the needs of selected minority groups.

In summary, we find that – with the exception of the controversial public service item – diversity policies are supported, or at least accepted, by many urban residents in Germany. Explicit opposition is limited, although significant shares avoid stating a clear opinion. We cannot tell what motivates such abstentions; hidden scepticism as well as perceived lack of information or interest may underlie them. Diversity and migration are sensitive topics, so social desirability may influence responses. Indeed, while, we see little outright opposition to all policies, abstentions may hide that. However, if social desirability concerns dominated responses, it would be hard to explain why people responded so differently to our eight questions.

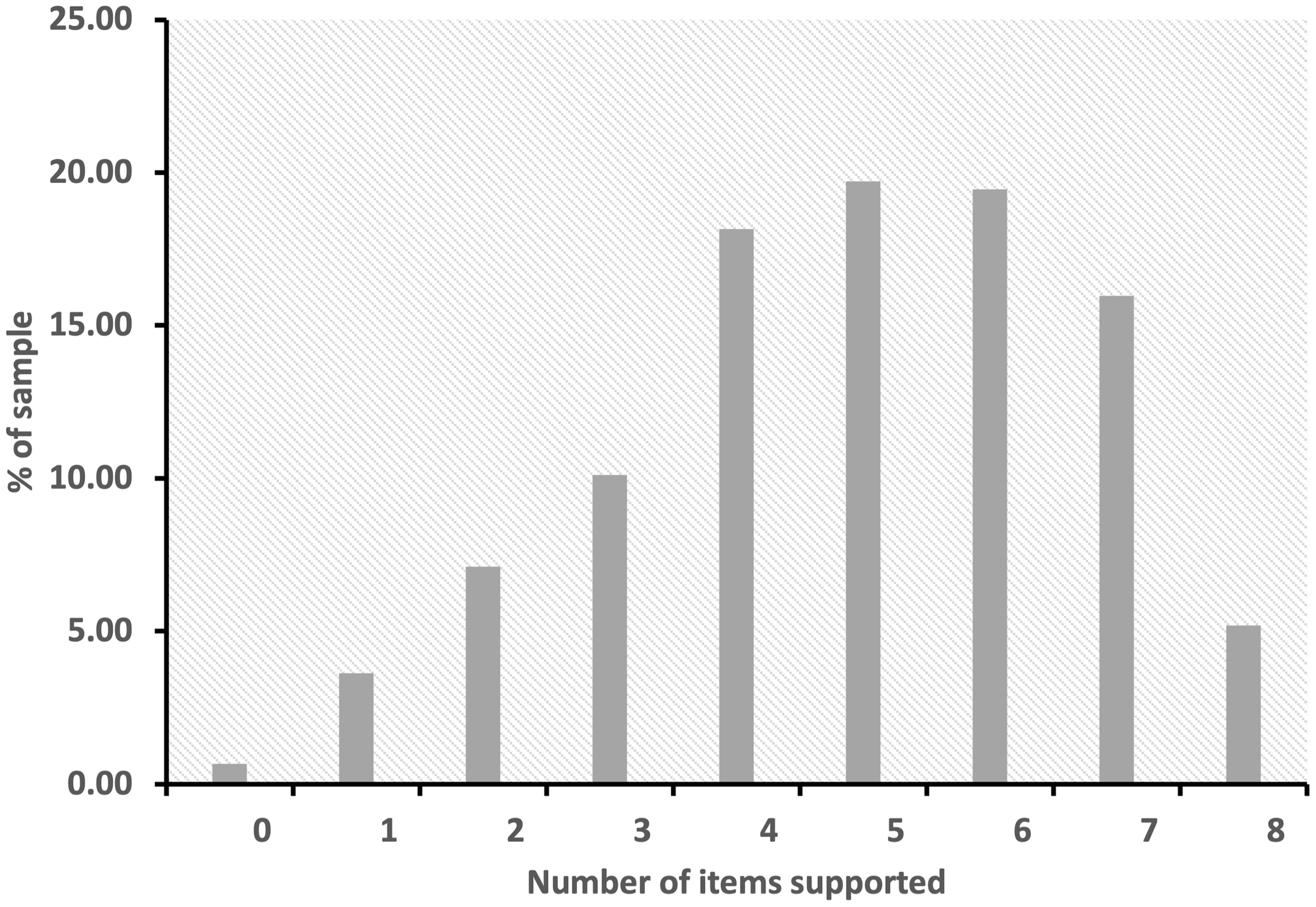

While support for individual pro-diversity items is widespread, it is not coherent across our eight items (see Fig. 2). Only 5% of the respondents expressed pro-diversity attitudes across all eight items. And yet, 60% of the respondents adopted pro-diversity positions for more than half of our eight items. Less than 1% never took a pro-diversity position, and only 4% of the respondents merely accepted one pro-diversity proposal.

Figure 2. Support for diversity policies by number of items.

Note: Percentages are weighted; n = 2,917. ‘Not supportive’ includes disagreement, neither nor and no answer. Source: DivA-Survey 2019–20.

It is difficult to identify a clear pattern here. We cannot confirm that support is lower once money comes into play – as other scholars assumed (e.g., Stolle et al., Reference Stolle, Harell, Soroka and Behnke2016). Funding minority cultural activities and support for minorities’ specific needs are widely accepted. However, policies targeting Muslims are less popular than other policies, a finding confirming widely held negative views of Muslims in the German population (Pollack and Müller, Reference Pollack, Müller, Ceylan and Uslucan2018). And yet, hostility towards Muslims does not explain the incoherent support pattern. If we set aside the two related questions (the right to build mosques, support for Muslim needs), still only 6% of the respondents expressed pro-diversity attitudes across all remaining items. When we exclude the unpopular public service item as well, support for the remaining five items rises to 29% of the sample. Many respondents chose not to include one or more items in a predominantly pro-diversity position, but their choices varied considerably. We proceed with multivariate analyses to shed more light on potential explanations.

Explaining support for diversity policies: multivariate analyses

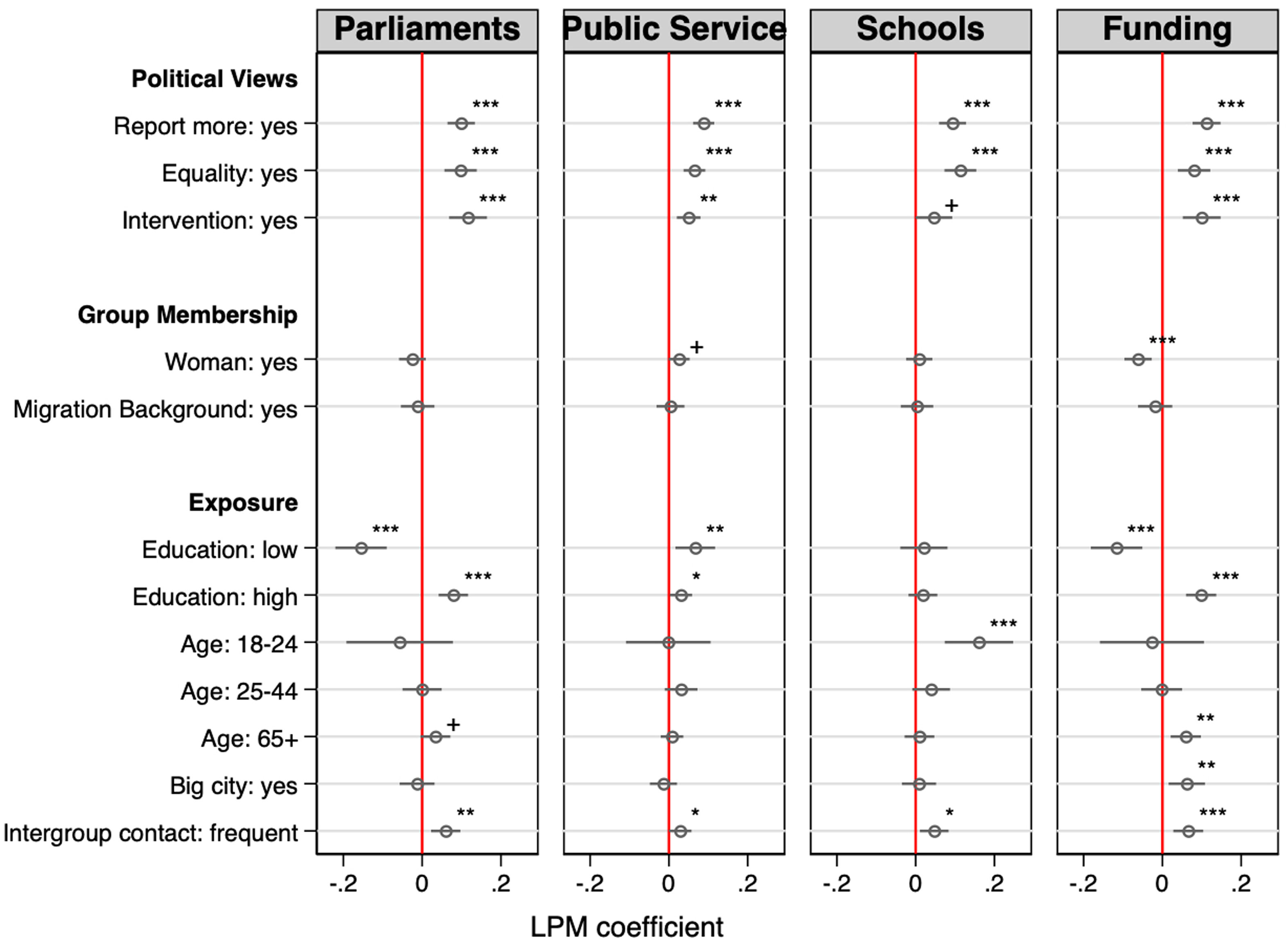

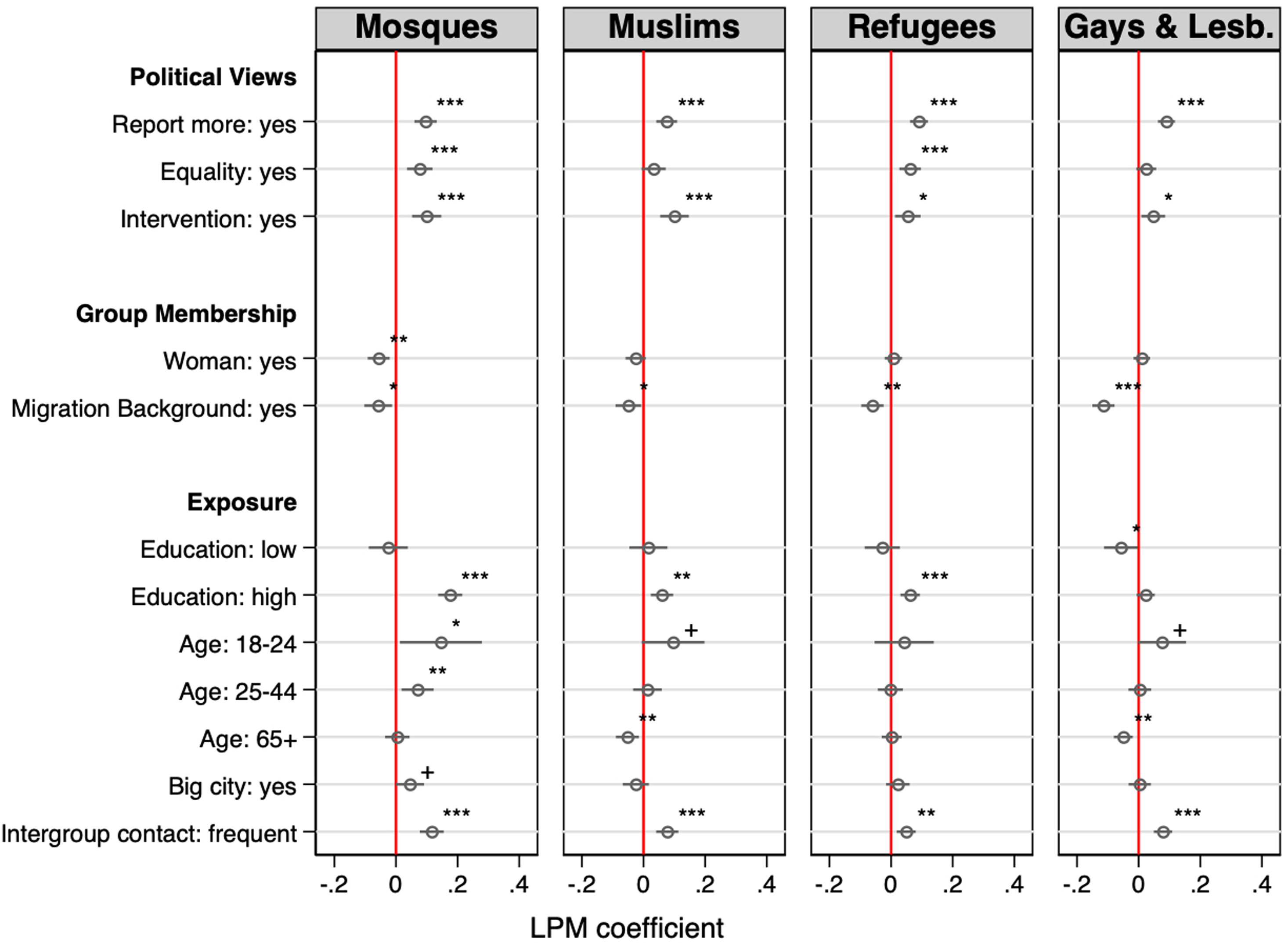

We now examine determinants of support for individual diversity policies using multivariate regression analysis. Figures 3 and 4 report the results for all eight models computed using LPM (see online Appendix A for regression tables). They are interpreted as follows. A coefficient represents the change in the probability of respondents supporting a diversity policy when the independent variable increases by one unit. A positive coefficient indicates an increased probability, while a negative coefficient indicates a decreased probability. For easier interpretation, multiplying the coefficient by 100 provides the percent probability of the outcome occurring. For example, Fig. 3, model 4 shows that women have a 6% decreased probability of supporting government funding for minority cultural traditions, compared to men, holding other factors constant (Fig. 3: Coefficient 0.06 × 100 = 6%).

Figure 3. Results from linear probability models I.

Note: This figure shows results from four linear probability models (LPM). The dependent variable is shown in the header. All models are computed with robust standard errors. Horizontal bars represent 95% confidence intervals; p-values are shown alongside markers: + P < 0.1, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. Source: DivA-Survey 2019–20; n = 2,826.

Figure 4. Results from linear probability models II.

Note: This figure shows results from four linear probability models (LPM). The dependent variable is shown in the header. All models are computed with robust standard errors. Horizontal bars represent 95% confidence intervals; p-values are shown alongside markers: + P < 0.1, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. Source: DivA-Survey 2019–20; n = 2,826.

We begin by discussing the influence of political views, addressed in our first hypothesis. To start, views concerning social equality and interventions to reduce inequality are important determinants of individual support for pro-diversity policies. People who acknowledge that social inequality is a problem in German society are also more likely to support policies for more equal participation. Pro-equality views are significant in all but two models. The weight they carry varies, but a person who considers social inequality a problem has a 6.5 to 11.4 percentage points increased probability to also support diversity policies, compared to someone who does not acknowledge that inequality is a problem, holding other factors constant. Somewhat surprisingly, critique of inequality is not associated with support for measures to meet the needs of Muslims as well as of gays and lesbians; both may not (just) be seen as an equality issue, but touch upon moral convictions. Next, believing that interventions are desirable to reduce inequality, is positively and strongly correlated with support for pro-diversity policies across all eight models. Lastly, people agreeing that the media should pay more attention to discrimination in Germany, thus those aware of a discrimination problem, are also more likely to support pro-diversity policies. The correlation is highly significant and positive for all policy items. This finding confirms the expectation that problem-awareness concerning discrimination is associated with support for diversity policies. Overall, all three political views tested here are important predictors of support for pro-diversity policies. We confirm our first hypothesis.

Our second hypothesis assumes that being part of a disadvantaged group affects individual support for pro-diversity policies. First, the results for gender are inconclusive. Women are less likely to support the right to build mosques. This may be due to an anti-Muslim bias, but the result for supporting Muslim needs is not significant. Women are also significantly less likely to approve of funding for cultural traditions of minorities, an item that does not mention religion. Only for one item, being female has a positive impact, that is, ensuring more diversity in public service employment. Gender, however, is unrelated to support for diverse parliaments. These latter two items can be seen as relating to policies likely to benefit women, but only one finds significant support, albeit only at the 10 per cent level. We find no effect for the remaining items: religious plurality in schools and support for the specific needs of Muslims, refugees and gays/lesbians. Previous literature had suggested that women are generally more supportive of affirmative action measures (e.g., Teney et al., Reference Teney, Pietrantuono and Möhring2023), a finding we cannot confirm for the diversity policies tested here.

Second, and also contrary to expectations, having a migration background even reduces the likelihood of supporting measures for specific minority groups. This is regardless of the group meant to benefit from such measures (refugees, Muslims or gays and lesbians). Migrants and their descendants are also less likely to support the right to build mosques in their own neighbourhood. The number of Muslims in the sample is small, and non-Muslim immigrants may not see common interests. A sub-group analysis reveals that Christian migrants, a significant share of migrants in Germany, are significantly less likely than others to support meeting Muslim needs and mosque building (see online Appendix B, Tables 1a, 1b). For the other four policy items, migration background has no relevance. Our second hypothesis is thus not confirmed, for none of the two groups tested.

Within the wide-ranging category of migration background, that is, individuals born in another country than Germany or with parents who immigrated, not everyone may feel disadvantaged as an immigrant or identify with other immigrants and other disadvantaged groups. Further, respondents may not see themselves, or a group they identify with, as potential beneficiaries of diversity policies. They may even fear a backlash if set apart. Previous research has shown that sensitivity to disadvantage differs across migrant generations (e.g., Schaeffer and Kas, Reference Schaeffer and Kas2024). Our own results point in the same direction. We find that foreign-born migrants are significantly less supportive of diversity policy than the second generation concerning funding minority cultures, building mosques, meeting specific needs of refugees and gays and lesbians (see online Appendix B, Tables 2a, 2b). First- and second-generation migrants do not differ concerning their support for the remaining four diversity policies. Here, some more specific mechanisms might be at play that we cannot grasp with our data.

Finally, exposure-based factors also play an important role for pro-diversity attitudes, as our third hypothesis assumed. Education presents the largely expected picture. On the one hand, we see that higher educated people have an increased probability to support policies targeting minorities. This is true regarding funding for cultural activities, support for mosque building, for Muslims and refugees – but not for gays and lesbians. They are also more supportive of diverse parliaments than people with a lower educational level. In contrast, a lower level of formal education is associated with a significantly lower likelihood to support diverse parliaments and funding of minority cultures. Interestingly, educational levels are not related to backing equal representation of all religions in schools. Regarding public service recruitment, lower and higher levels of education are associated with more support for the diversity policy. Possibly middle education levels go along with a stronger belief in already fair recruitment processes in that sector. However, in general, the education effects confirm expectations.

Turning to age, we find that younger respondents are more open to supporting Muslims, mosque building, and equal representation of all religions in schools. They are also more supportive of measures favouring gays and lesbians. In contrast, belonging to the oldest group is associated with more supportive views on funding for minority culture. Possibly, this age group is more disposed to funding culture in general. Younger respondents tend to show more tolerance for religious and sexual diversity, but age remains insignificant in relation to meeting refugee needs, ensuring parliamentary diversity and promoting diversity in the public service.

Living in a bigger city hardly matters. Only for funding of minority cultures did we find clear effects in the expected direction, with greater support in bigger cities. Altogether, the on average greater diversity and more widespread diversity policies prevalent in larger cities do not seem to impact residents’ attitudes towards diversity policies to any remarkable extent.

Intergroup contact is positively and significantly associated with support for all pro-diversity policies, a remarkably consistent result. This finding aligns with the theoretical assumptions derived from contact theory (e.g., Schönwälder et al., Reference Schönwälder, Petermann, Hüttermann, Vertovec, Hewstone, Stolle, Schmid and Schmitt2016: 171–205), but, so far, mostly tested for general attitudes to other groups. We can show that exposure to others is positively associated with an increased probability to favour policies acknowledging diversity and supporting under-represented groups. In some models, this association might be attributed to non-migrants having frequent contact with migrants (see online Appendix B, Tables 3a, 3b). Unfortunately, our data does not allow us to examine the direction of causality, that is, whether those with more positive diversity policy attitudes seek more inter-group contact. However, previous research in Germany provides some evidence suggesting a causal relationship between inter-group contact and positive attitudes towards refugees (Giesselmann et al., Reference Giesselmann, Brady and Naujoks2024) and other immigrant groups (Schönwälder et al., Reference Schönwälder, Petermann, Hüttermann, Vertovec, Hewstone, Stolle, Schmid and Schmitt2016). In sum, mainly intergroup contact and education are consistently associated with support for diversity policy, partially confirming, but also refining, our third hypothesis.

Discussion and conclusions

Policies aiming to acknowledge the growing socio-cultural diversity of populations and ensure fairer participation are nowadays common practice in many European states. But to what extent are such diversity policies supported by the population? Using original data for residents in German cities, one aim of this article was to shed light on the extent and structure of support for diversity policies. Overall, we found considerable support for public diversity policies. Majorities of urban residents endorse many of the proposed interventions and guiding principles. Like previous studies (e.g., Krysan, Reference Krysan2000) though, we found that not all pro-diversity policies are backed to the same extent. We clearly see effects of an anti-Muslim bias. Where Muslims or Islam are mentioned as beneficiaries of policies, levels of support are lower than for other policies – although even here, explicit opposition remains limited. Equal representation of all religions in school education, however, is backed by a clear majority. Pollack and Müller (Reference Pollack, Müller, Ceylan and Uslucan2018: 104) describe positions of the German population to religious diversity as ambivalent. Possibly, explicit reference to Islam, as in the mosque question, triggers more negative reactions. Indeed, Helbling and colleagues (Reference Helbling, Jäger and Traunmüller2022) contend that the Muslim bias is strongly driven by a religiosity bias.

Financial implications do not seem to impact support for different diversity policies, other than assumed by some scholars (e.g., Stolle et al., Reference Stolle, Harell, Soroka and Behnke2016). Alongside the cost-neutral diversity in parliaments, the costly funding for minority cultures is widely supported. However, employment policy for the public service is contentious. Apparently, confidence in the fairness of recruitment processes described as based on suitability and qualifications is strong. Many respondents may also perceive interventions aiming to raise the share of previously disadvantaged groups as a threat to their own opportunities. Controlling for other factors, not even women and those with migration backgrounds are more supportive of such policies, although they would likely be the beneficiaries. Our survey did not include a related question on the private sector, so we cannot tell whether changes to the public service are a particularly sensitive issue, or a generally strong belief in the fairness of recruitment practices (Bohmann and Liebig, Reference Bohmann and Liebig2022: 100) makes changes to these practices seem superfluous. Altogether, however, support for diversity policies is widespread.

Turning to the second main aim of this article, to shed light on factors motivating support for diversity policies, our results partly deviate from those of previous research. In particular, the assumption of group interest as a key motivation was not confirmed. Neither women nor individuals with a migration history are particularly likely to back diversity policies, all else being equal. Immigrants are even more sceptical regarding mosque building as well as regarding support for the needs of specific minority groups. Several reasons may be at play. The statistical group of individuals with a migration background is a very heterogeneous group in Germany. Many are neither Muslims nor belong to visible minorities, that is, those more likely to experience discrimination. A very heterogeneous group is less likely to form a group consciousness, ascribed, and perceived identity may not coincide. People with migration backgrounds may not perceive themselves as part of a disadvantaged minority, thus lack the group consciousness necessary for any perception of group interests (Lee, Reference Lee2008: 468–469). This is even less likely where political actors mobilizing around the migration experience, discrimination, and the right to compensatory measures remain weak, as in Germany. Previous research on support for minority political representation also found that migrant-origin residents in Germany do not behave as ‘a uniform group’ (Street and Schönwälder, Reference Street and Schönwälder2021: 2663). Further, individuals may – even if they identify with the group – not agree with the proposed measures. Diversity policies may not be supported for fear that emphasizing group membership and minority rights will provoke opposition; a strategy of assimilation may be seen as an alternative path towards equality.

Women may not be particularly supportive of diversity policies in general, because they do not identify with immigrant minorities, addressed in some of our policy items. They appear to be slightly more negatively disposed towards Muslims. However, somewhat surprisingly, of the policies likely to benefit women, they are only slightly more supportive of one, namely employment policy. Apparently, self-interest does not motivate our sample in the hypothesized way. It may too often be assumed that people who share a demographic label also share common interests, a link that should be further investigated (Lee, Reference Lee2008). Possibly, women are more supportive of only specific, dedicated policies, such as gender quota for management positions (Barnes and Córdova, Reference Barnes and Córdova2016; Teney et al., Reference Teney, Pietrantuono and Möhring2023), an issue that should be further investigated. More attention also should be paid to context-specific political processes necessary for the formation of group consciousness and perceptions of common interests.

Exposure to difference and a variety of socio-cultural practices was not found to consistently correlate with positive views of diversity policies. Indeed, scholars have expressed doubts about the influence of environmental factors on immigration attitudes (Kustov et al., Reference Kustov, Laaker and Reller2021). In our own analysis, only intergroup contact was consistently associated with support for diversity policies. In particular, non-immigrants who frequently interact with others who have migration experiences are more likely to agree with policies aiming to increase fair participation and representation. Such contact likely goes along with more insights into the disadvantages and discrimination experiences faced by minorities, thus making diversity policies seem more urgent. While our own study cannot establish causal effects, contact is known to reduce negative attitudes to minorities (Giesselmann et al., Reference Giesselmann, Brady and Naujoks2024), attitudes that might lower support for diversity policies. In contrast, the more indirect experience of diversity through living in bigger cities has no clear effect. This aligns with the ‘Diversity and Contact’ study (Schönwälder et al., Reference Schönwälder, Petermann, Hüttermann, Vertovec, Hewstone, Stolle, Schmid and Schmitt2016: 204–205) conducted earlier in a partly identical sample of cities. Here, diverse contexts affected attitudes to diversity only as mediated through increased intergroup interaction. The findings suggest that observations alone, in the absence of direct personal contact, have limited impact. Higher education also altogether showed the expected positive association with support for diversity policy.

The clearest results were found for general egalitarian commitments. Residents of German cities seem to favour diversity policies because they perceive social inequalities as problematic or unjust and favour interventions to correct them. Consistent with findings in previous studies (e.g., Möhring et al., Reference Möhring, Teney and Buss2019; Scarborough et al., Reference Scarborough, Lambouths and Holbrook2019) and in line with our own expectations, we found that specific political views, in our case egalitarian commitments and the view that discrimination is a problem worth more attention, are clearly related to supporting diversity policies. Clearly, such views matter more than socio-demographic characteristics; at least in Germany, political views, rather than group membership seem to drive support for diversity policies.

Our study focused on general and immigrant-related diversity policies. Our results indicate that drivers of pro-diversity views may deviate somewhat when sexual minorities are the intended beneficiaries. Possibly, in this case, egalitarian commitments are overshadowed by heteronormative convictions. More comparative research covering various dimensions of diversity policy, such as gender, migration, LGBTIQ, and disability, would be desirable.

Our findings contribute important and novel insights into support for diversity policies in Europe. Nevertheless, some limitations exist due to the geographical scope of the survey. Our results reflect the views of the urban population in Germany. Rural populations are often somewhat less supportive of diversity, which may well be the case for diversity policies. Further, national peculiarities, including the strength of equality norms and the influence of pro-diversity movements, may shape results. To what extent our results extend to rural areas and can be replicated in other countries should be answered by further studies. To allow such research, surveys should more often include a broad range of relevant items. Group consciousness and interest perception among disadvantaged groups also deserve further investigation; here targeted sampling and a broader range of questions are necessary.

Altogether, awareness and critique of inequality and discrimination as well as intergroup contact most clearly predict support for diversity policies. Its extent is surprisingly broad among residents of German cities – a result that contradicts earlier scepticism regarding public support for multiculturalism policies. Such support is not tied to self-interest, but ranges across population groups. This has important political implications. In general, actors promoting diversity policies can rely on widespread, albeit uneven, backing of such policies, at least in the urban population. It may be a particularly promising approach to present such policies as embedded in general efforts to make society more equal.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773925000104.

Data availability statement

Data used in the analysis are in the online repository GESIS – Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences at https://doi.org/10.7802/2581.

Acknowledgements

Lucas Drouhot, Eloisa Harris, Sören Petermann, and Steven Vertovec have contributed to the development of the survey and dataset underlying this analysis. Apart from them, we thank Margherita Cusmano and Laurence Go for their valuable input on previous drafts of this text.

Funding statement

The ‘Diversity Assent’ project was made possible through funding from the Max Planck Society.

Competing interests

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Ethics statement

The Diversity Assent (DivA) Survey was conducted by a professional company, Kantar. Practices of such companies are subject to regulations in the Bundesdatenschutzgesetz (Federal Law on Data Protection), ensuring strict anonymization. We only received an anonymized dataset. Detailed written information on the survey and data protection was made available to (potential) respondents. In developing the questionnaire, great care was taken to avoid any unethical content and of course in any way abusive or discriminatory language. A formal ethics review was at the time not available at our institution. However, the Max Planck Society has rigid regulations on research ethics and data protection, binding for all its researchers https://www.mpg.de/199493/regelnWissPraxis.pdf.