Introduction

Restrictive or coercive practices are used to maintain staff and patient safety in psychiatric hospital settings under relevant legal frameworks, but must only be undertaken in a manner that is compliant with human rights. There is increasing emphasis on reducing the use of these practices, or, when they are unavoidable, ensuring they are implemented as safely and briefly as possible. Restrictive interventions for managing behavioural disturbance encompass seclusion, chemical restraint, manual restraint using holds, and mechanical restraint (MR). Here, we define MR as per the UK’s Mental Health Act 1983 Code of Practice, as “a form of restrictive intervention which involves the use of a device to prevent, restrict or subdue movement of a person’s body, or part of the body, for the primary purpose of behavioural control.”

Although some attempts have been made to standardise practices across regions, for example, in Europe [Reference Luciano, De Rosa, Sampogna, Del Vecchio, Giallonardo and Fabrazzo1], patterns of the different types of restrictive practice still vary substantially. In some countries, only certain approaches are used [Reference Steinert and Lepping2], or even legal. Opinions and attitudes of staff, different legislation, and hospital policies [Reference Steinert and Lepping2, Reference Bowers, Alexander, Simpson, Ryan and Carr-Walker3] appear to play a greater role than empirical data. One systematic review highlighted wide variation in rates, indications, and outcomes of the use of seclusion between The Netherlands, Finland, and the USA [Reference Chieze, Hurst, Kaiser and Sentissi4]. Standard clinical practices in different countries suggest this is likely also the case for MR. For example, in the UK, the use of MR is usually confined to secure hospitals, most commonly high security hospitals, or during the transfer of patients between secure settings, whereas in some European contexts, it is more commonly used in general adult settings. However, national and international patterns of use, and associated outcomes, are not understood in detail. Addressing this deficit is important due to unique ethical and acceptability considerations associated with MR.

Previous syntheses of evidence for MR in psychiatric settings have been limited in scope. A 2006 review explored short-term management of violence in adult psychiatric settings and emergency departments [Reference Nelstrop, Chandler-Oatts, Bingley, Bleetman, Corr and Cronin-Davis5], however, MR was not emphasised. A Cochrane review on seclusion and restraint in the context of serious mental illness, last updated in 2012, only considered randomised trials, and so was not able to include any studies [Reference Sailas and Fenton6]. Two further reviews of seclusion and restraint have included wider observational study designs. One [Reference Gleerup, Østergaard and Hjuler7] narrowly defined MR as the “restraining of a patient to a bed using belts or straps,” and included only studies comparing seclusion and restraint with quantitative measures. The other [Reference Chieze, Hurst, Kaiser and Sentissi4] focused on adverse physical and mental outcomes, but forensic populations were excluded.

Together, the existing evidence base offers some insights into the current use of MR within the context of restrictive practice internationally, but a systematic appraisal of indications, patterns of use, regional variation, and outcomes, specific to MR, has been lacking. The current review addresses these gaps, by 1) focusing on MR only, 2) including a broad range of study designs and outcomes, including qualitative studies, and 3) clarifying the degree of regional variation in use. We also considered studies that examined the impact of interventions to reduce the use of MR, or the repercussions of ceasing its use. In so doing, we aimed to provide a comprehensive overview of available evidence specifically for MR, to inform policy and practice regarding its use in restrictive practices, and to provide clearer targets for future clinical research.

Methods

We used standard systematic review methodology, with some adaptations in line with recent guidance from the Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group [Reference Nussbaumer-Streit, Sommer, Hamel, Devane, Noel-Storr and Puljak8–Reference Gartlehner, Nussbaumer-Streit, Devane, Kahwati, Viswanathan and King10] for the benefits of rapid evidence synthesis (title/abstract screening and data extraction were undertaken by a single reviewer with 20% cross-check). The review was pre-registered on PROSPERO (CRD42023472271).

Search strategy

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, and PsycInfo for English language studies from inception to 7 September 2023, using a search strategy developed with information specialists [11] (Supplementary 1). We did not apply date limits to our search but made the subsequent decision to exclude studies conducted pre-1990, as, in keeping with large-scale work highlighting changes in psychiatric morbidity and treatment internationally from 1990 [Reference Kessler, Demler, Frank, Olfson, Pincus and Walters12, Reference Wu, Wang, Tao, Cao, Yuan and Ye13], it was agreed among the review team that studies undertaken earlier are unlikely to be representative of contemporary psychiatric settings. For a clinically meaningful comparison of contemporary practice in relation to restrictive practice internationally, in our synthesis, we presented data separately for a subgroup of studies reporting data from 2010 onwards, given that this decade was characterised by the introduction in Europe of specific universal initiatives, such as the “Safewards” model [Reference Stensgaard, Andersen, Nordentoft and Hjorthoj14].

Eligibility assessment

Included studies were of adults (aged 18–65) admitted to inpatient psychiatric settings. Studies in youth samples and old age psychiatry samples, in which demographics likely introduce further variation, were beyond the scope of the current review. No diagnostic exclusion criteria were applied. Psychiatric assessment units within general emergency departments were not considered for inclusion.

MR was defined as any form of restrictive intervention involving the use of a device to prevent, restrict or subdue movement of a person’s body, or part of the body, for the primary purpose of behavioural control. Studies that did not disaggregate findings between MR and other forms of restrictive practice such as manual restraint, or did not specifically define the restraint method used, were excluded. Studies reporting restraint for the purposes of nasogastric feeding in patients with an eating disorder, or examining the restraint of patients in general medical settings such as intensive care units, were not considered for inclusion as these represent distinct clinical scenarios.

No comparator intervention was required for inclusion, however, studies in which MR was compared with other forms of restrictive intervention in terms of frequency of use or reasoning were considered for inclusion. Any reported intended or unintended effect of MR was considered for inclusion, both subjective/qualitative measures and objectively measured/quantitative outcomes. Qualitative data were considered for inclusion, given their utility to address complex healthcare questions, such as here around patterns, experiences, and outcomes of MR, thus adding understanding to an area that has been historically understudied.

Any primary randomised or observational study that reported patterns of use and/or outcomes associated with MR was considered. Qualitative studies that employed defined qualitative methodology (i.e. description of recognised approaches to sampling, data collection, and analysis) were eligible for inclusion. Reviews, commentaries of primary studies, and studies that surveyed staff or patient views or perspectives were not considered.

Data extraction and analysis

A standardised template was used for data extraction by two reviewers (JT and DW), with 20% cross-checked by a third (AL). The level of heterogeneity (e.g. in design, population, outcome, type of MR) was anticipated to be, and found to be, such that quantitative synthesis would not be appropriate, and narrative synthesis was instead undertaken. We predefined a plan whereby when discrepancies between reviewers arose, these would be resolved initially through consensus discussions among the two reviewers, and if necessary, by consulting a third reviewer.

Quality assessment

For studies reporting the prevalence of MR, the risk of bias was assessed using a checklist developed by Hoy and colleagues [Reference Hoy, Brooks, Woolf, Blyth, March and Bain15] and adapted by Agbor and colleagues by removing the criterion for the shortest appropriate prevalence period [Reference Agbor, Takah and Aminde16]. For studies focussed on examining the impact of an intervention to reduce the use of MR, the Newcastle-Ottawa scale was used [Reference Wells, O’Connell, Peterson, Welch, Losos and Tugwel17].

Results

Characteristics of included studies

Searches returned 2,108 unique records, and 309 full texts were reviewed for inclusion (see Supplementary 2 for PRISMA flow diagram). We included 83 articles, which reported on 73 separate studies or datasets. Included studies presented data from between 1990 and 2022, from 22 countries (with some reporting data from multiple countries): 14 from Denmark [Reference Stensgaard, Andersen, Nordentoft and Hjorthoj14, Reference Andersen and Nielsen18–Reference Gildberg, Fristed, Makransky, Moeller, Nielsen and Bradley33], 9 from Germany [Reference Bergk, Einsiedler, Flammer and Steinert34–Reference Badouin, Bechdolf, Bermpohl, Baumgardt and Weinmann45], 6 each from Japan [Reference Hubner-Liebermann, Spiessl, Iwai and Cording42, Reference Eguchi, Onozuka, Ikeda, Kuroda, Ieiri and Hagihara46–Reference Noda, Sugiyama, Sato, Ito, Sailas and Putkonen50] and Switzerland [Reference Martin, Bernhardsgrutter, Goebel and Steinert44, Reference Chieze, Courvoisier, Kaiser, Wullschleger, Hurst and Bardet-Blochet51–Reference Stoll, Westermair, Kubler, Reisch, Cattapan and Bridler55], 5 each from China [Reference Valimaki, Lam, Hipp, Cheng, Ng and Ip56–Reference Chien, Chan, Lam and Kam60], Norway [Reference Bak, Zoffmann, Sestoft, Almvik and Brandt-Christensen19, Reference Bak, Zoffmann, Sestoft, Almvik, Siersma and Brandt-Christensen20, Reference Husum, Bjorngaard, Finset and Ruud61–Reference Reitan, Helvik and Iversen65] and Spain [Reference El-Abidi, Moreno-Poyato, Toll Privat, Corcoles Martinez, Acena-Dominguez and Perez-Sola66–Reference Guzman-Parra, Garcia-Sanchez, Pino-Benitez, Alba-Vallejo and Mayoral-Cleries71], 4 each from Italy [Reference Dazzi, Tarsitani, Di Nunzio, Trincia, Scifoni and Ducci72–Reference Tarsitani, Pasquini, Maraone, Zerella, Berardelli and Giordani75] and the United States [Reference Newton-Howes, Savage, Arnold, Hasegawa, Staggs and Kisely49, Reference Staggs76–Reference Smith, Altenor, Altenor, Davis, Steinmetz and Adair79], 3 from Finland [Reference Keski-Valkama, Sailas, Eronen, Koivisto, Lonnqvist and Kaltiala-Heino80–Reference Valimaki, Yang, Vahlberg, Lantta, Pekurinen and Anttila84], 2 each from Australia [Reference Newton-Howes, Savage, Arnold, Hasegawa, Staggs and Kisely49, Reference McKenna, McEvedy, Maguire, Ryan and Furness85], Belgium [Reference De Hert, Einfinger, Scherpenberg, Wampers and Peuskens86, Reference van Heesch, Boucke, De Somer, Dekkers, Jacob and Jeandarme87], Poland [Reference Kostecka and Zardecka88, Reference Lickiewicz, Adamczyk, Hughes, Jagielski, Stawarz and Makara-Studzinska89], Slovenia [Reference Tavcar, Dernovsek and Grubic90, Reference Celofiga, Kores Plesnicar, Koprivsek, Moskon, Benkovic and Gregoric Kumperscak91] and The Netherlands [Reference Georgieva, Vesselinov and Mulder92, Reference Noorthoorn, Lepping, Janssen, Hoogendoorn, Nijman and Widdershoven93], and 1 each from Austria [Reference Fugger, Gleiss, Baldinger, Strnad, Kasper and Frey94], Canada [Reference Dumais, Larue, Drapeau, Menard and Giguere Allard95], Greece [Reference Bilanakis, Kalampokis, Christou and Peritogiannis96], Israel [Reference Porat, Bornstein and Shemesh97], New Zealand [Reference Newton-Howes, Savage, Arnold, Hasegawa, Staggs and Kisely49], Nigeria [Reference Aluh, Ayilara, Onu, Grigaite, Pedrosa and Santos-Dias98], and Scotland [Reference Walker and Tulloch99]. Of 185 data points cross-checked by a second reviewer, there were seven minor discrepancies (96% concordance), all resolved by consensus. Further characteristics are reported in Supplementary 3. See Supplementary 4 for full details of included quantitative studies of rates, associations, and outcomes, and Supplementary 5 for quality assessment of these studies.

Contemporary studies reporting prevalence of mechanical restraint

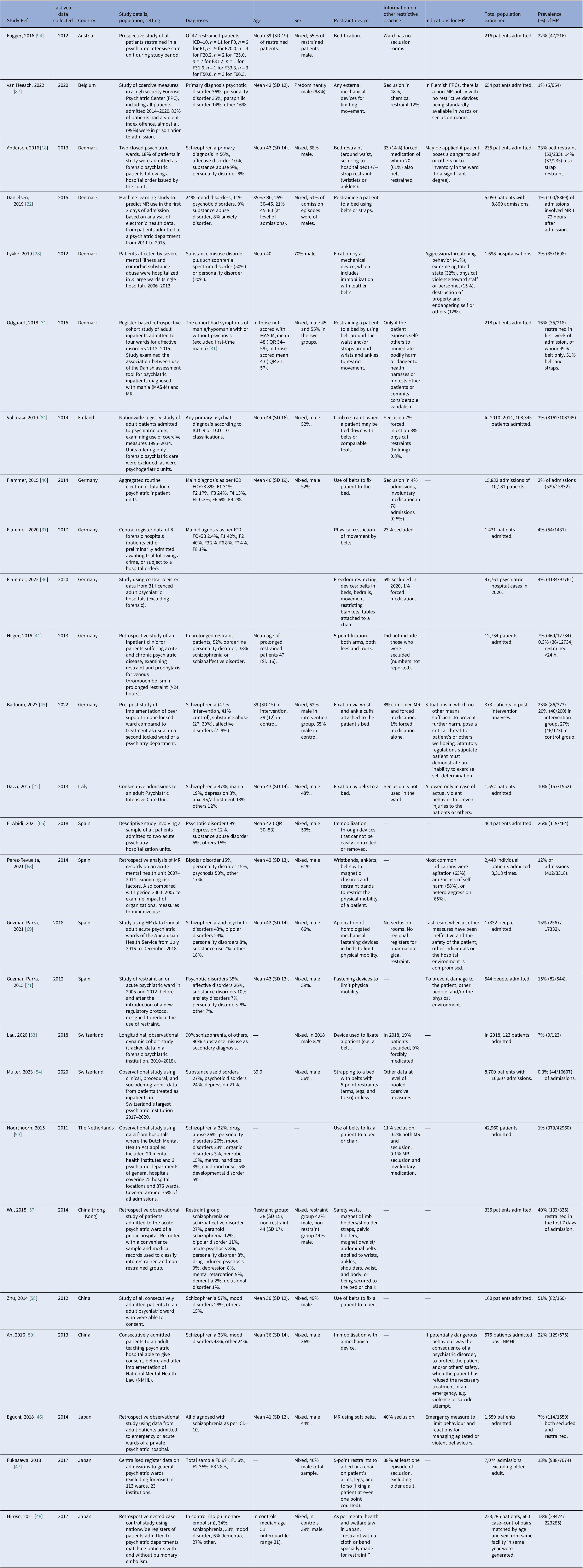

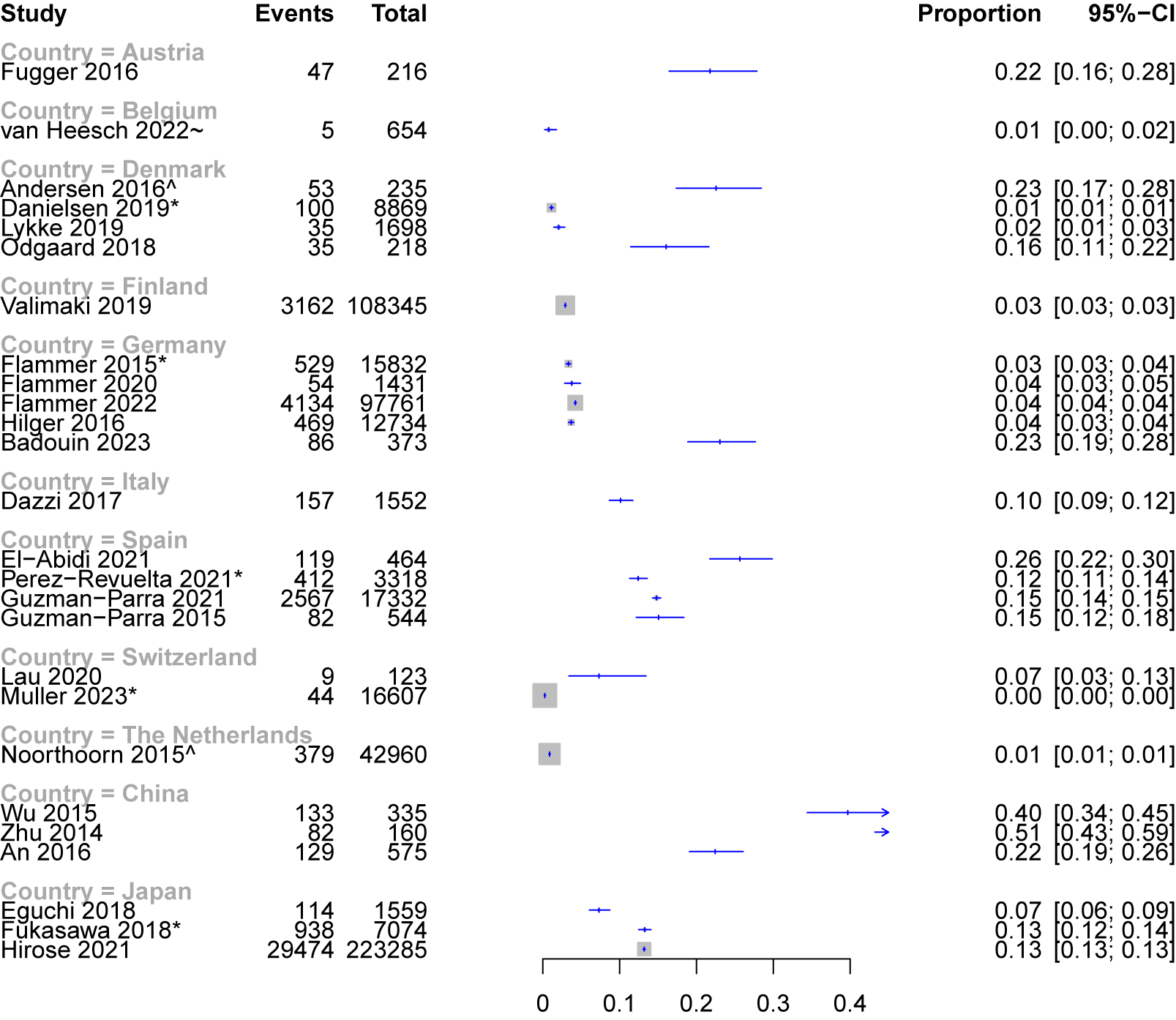

Twenty-six studies, conducted in 11 countries, presented prevalence data from 2010 onwards as proportions of all patients or hospital admissions affected by MR (Table 1). We present these for visual comparison in Figure 1, though as per our protocol, we did not pool data. In Europe, prevalence in adult inpatient settings varied between 0.3% in a study in Switzerland [Reference Muller, Brackmann, Jager, Theodoridou, Vetter and Seifritz54], up to 26% in one Spanish study [Reference El-Abidi, Moreno-Poyato, Toll Privat, Corcoles Martinez, Acena-Dominguez and Perez-Sola66]. In Japan, individual studies reported a prevalence of 7–13%, whereas the proportion of use was higher in China, ranging from 22–51% in the three included studies. The prevalence of MR also varied within countries.

Table 1. Subset of included studies that reported data from 2010-onwards for the proportion of all patients or hospital admissions affected by mechanical restraint (MR). Where studies reported data from a series of years, or pre−/post-intervention, the most recent or post-intervention data was chosen for comparison. SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range.

Figure 1. Proportion of patients or admissions (indicated by *) affected be mechanical restraint in included studies (2010 onwards) where this data was reported. ^Mixed adult and forensic samples. ~forensic sample.

Studies of forensic populations

Among the 10 studies that explicitly included forensic patients, one German study included 1,431 patients admitted across eight forensic hospitals, examining restraint compared with general psychiatric wards [Reference Flammer, Frank and Steinert37]. MR with belts affected 4% of patients in forensic wards, slightly lower than in the general psychiatric wards. However, the proportion of patients subject to seclusion (23%) was around 8-fold higher in the forensic wards than in general psychiatric hospitals. A Dutch study in which the overall use of restraint was very low (<1%) reported that restraints were primarily on forensic rather than general wards [Reference Noorthoorn, Lepping, Janssen, Hoogendoorn, Nijman and Widdershoven93]. Similarly low rates of MR were reported in a study of a high-security forensic setting in Belgium, where out of 654 patients admitted over six years, five (0.8%) were mechanically restrained [Reference van Heesch, Boucke, De Somer, Dekkers, Jacob and Jeandarme87]. This is in the context of a clear local policy for no MR- in contrast, 48% of included patients were secluded. Two studies of forensic settings used qualitative methods to examine patient and staff perspectives [Reference Gildberg, Fristed, Makransky, Moeller, Nielsen and Bradley33, Reference Walker and Tulloch99], or examined the impact of interventions to reduce restraint in forensic settings [Reference Hvidhjelm, Brandt-Christensen, Delcomyn, Mollerhoj, Siersma and Bak30, Reference Smith, Ashbridge, Altenor, Steinmetz, Davis and Mader78, Reference Smith, Altenor, Altenor, Davis, Steinmetz and Adair79], discussed below.

Quantitative studies of rates, associations, and outcomes

Patterns and indications

Indications for MR were typically broad across included studies, principally for physical violence, threats, or aggression, or for significant danger to self or property. There was limited comparison of outcomes when restraint was used for different indications, although a study of 371 restrained patients in Norway reported those who were mechanically restrained for self-injury were restrained for significantly shorter periods than for other reasons [Reference Knutzen, Bjorkly, Eidhammer, Lorentzen, Helen Mjosund and Opjordsmoen62, Reference Knutzen, Bjorkly, Eidhammer, Lorentzen, Mjosund and Opjordsmoen63].

In some cases, local policy dictated that physical violence was the only indication for use [Reference Dazzi, Tarsitani, Di Nunzio, Trincia, Scifoni and Ducci72]. Local policy emphasis appeared to be related to the prevalence of use. For example, in one Swiss study, ward policy stated it was for “highly exceptional” use, with a preference instead for seclusion and forced medication. MR in this setting was low (0.5% of admissions) [Reference Chieze, Courvoisier, Kaiser, Wullschleger, Hurst and Bardet-Blochet51]. In contrast, in one Italian psychiatric intensive care setting, seclusion was not available, and here 10% of patients were restrained at least once [Reference Dazzi, Tarsitani, Di Nunzio, Trincia, Scifoni and Ducci72]. A smaller number of studies also referred to specific additional indications for MR, such as to permit treatment [Reference Porat, Bornstein and Shemesh97] or to reduce absconding risk [Reference Valimaki, Yang, Vahlberg, Lantta, Pekurinen and Anttila84], including in a planned manner for offsite transfers.

Studies reporting patterns in the use of MR considered numerous factors. Most consistently, in acute adult psychiatric settings, the early phase of admission (hours and days) was the period of highest risk for restraint [Reference Andersen and Nielsen18, Reference Perez-Revuelta, Torrecilla-Olavarrieta, Garcia-Spinola, Lopez-Martin, Guerrero-Vida and Mongil-San Juan68, Reference Di Lorenzo, Baraldi, Ferrara, Mimmi and Rigatelli73, Reference Lorenzo, Miani, Formicola and Ferri74]. In many cases, significant variation was found in use between different periods of the day and night, but the pattern of this varied between studies. Some reported less frequent use during the morning and afternoon shifts compared with the night shift [Reference Di Lorenzo, Baraldi, Ferrara, Mimmi and Rigatelli73]. Other studies found restraint occurring in other patterns, such as more often at night [Reference Lorenzo, Miani, Formicola and Ferri74], with morning and evening peaks [Reference Porat, Bornstein and Shemesh97], similarly distributed across day and night shifts [Reference Dazzi, Tarsitani, Di Nunzio, Trincia, Scifoni and Ducci72], or in the evening shift [Reference Kodal, Kjaer and Larsen24]. This included one Danish study (using data from 5,456 episodes of MR) in which restraint was initiated more often in evening than in day shifts (and with fewer episodes initiated at night for all types of coercion) [Reference Leerbeck, Mainz and Boggild25-Reference Martensson, Johansen and Hjorthoj27]. Another Danish study found that restraint was predominantly implemented during the day (8 am‐4 pm) and evening (4 pm‐12 am) shifts (82%), and only administered 18% of the time in the early morning when staff-patient ratios were lowest [Reference Lykke, Hjorthoj, Thomsen and Austin28].

One Norwegian study included 19,283 patients admitted to acute psychiatric settings over eight years and found that the use and type of restraint varied significantly by seasonal time [Reference Reitan, Helvik and Iversen65]. During summer, MR was used significantly more often than pharmacological restraint. A Danish study also found a significant variation by month of the year [Reference Kodal, Kjaer and Larsen24].

Clinical and demographic factors

Among the more consistent findings was an association of restraint and duration of restraint with male sex [Reference Noda, Sugiyama, Sato, Ito, Sailas and Putkonen50, Reference Knutzen, Bjorkly, Eidhammer, Lorentzen, Mjosund and Opjordsmoen63, Reference Knutzen, Sandvik, Hauff, Opjordsmoen and Friis64, Reference Dazzi, Tarsitani, Di Nunzio, Trincia, Scifoni and Ducci72, Reference Dumais, Larue, Drapeau, Menard and Giguere Allard95] and younger age [Reference Dazzi, Tarsitani, Di Nunzio, Trincia, Scifoni and Ducci72, Reference Dumais, Larue, Drapeau, Menard and Giguere Allard95]. Risk factors for restraint in individual studies also typically aligned with clinical factors associated with increased violence risk, such as persecutory ideation [Reference Danielsen, Fenger, Ostergaard, Nielbo and Mors22], intoxication [Reference Andersen and Nielsen18], poorer insight [Reference An, Sha, Zhang, Ungvari, Ng and Chiu59], and Broset violence checklist score [Reference Danielsen, Fenger, Ostergaard, Nielbo and Mors22].

The relevance of ethnicity or immigrant background was examined by several studies. A Norwegian study reported patients from ethnic groups other than Norwegian had a lower risk of restraint (odds ratio [OR] 0.4, 95% CI 0.2–1.0) [Reference Husum, Bjorngaard, Finset and Ruud61] and an inverse association with ethnicity was also reported by a study including 42,960 patients in The Netherlands [Reference Noorthoorn, Lepping, Janssen, Hoogendoorn, Nijman and Widdershoven93]. A Spanish study of 474 people consecutively admitted to acute wards found that language barrier was associated with a higher risk of MR (OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.2–3.7) [Reference El-Abidi, Moreno-Poyato, Toll Privat, Corcoles Martinez, Acena-Dominguez and Perez-Sola66]. An Italian study reported that extra-European nationality was associated with restraint [Reference Lorenzo, Miani, Formicola and Ferri74], and another study in Italy examined this relationship directly by matching 100 first-generation immigrants with 100 non-immigrants, finding that immigrant patients were more likely to be restrained as compared to Italian-born patients (11% vs 3%, relative risk [RR] 3.7, 95% CI 1.1–12.7) [Reference Tarsitani, Pasquini, Maraone, Zerella, Berardelli and Giordani75]. No significant differences were found between groups in rates of repeated restraints, however, nor in the overall duration of restraint, a finding mirrored by a study in Norway [Reference Knutzen, Bjorkly, Eidhammer, Lorentzen, Helen Mjosund and Opjordsmoen62, Reference Knutzen, Bjorkly, Eidhammer, Lorentzen, Mjosund and Opjordsmoen63].

Several protective factors were reported, such as prior community mental health contact [Reference Andersen and Nielsen18], negative symptoms, and negative affect [Reference Dazzi, Tarsitani, Di Nunzio, Trincia, Scifoni and Ducci72]. In a study comparing a total of 2,927 episodes of restraint in Denmark and Norway, mandatory review, patient involvement, and lack of over-crowding were significantly associated with a low frequency of MR episodes, and six preventive factors confounded the differences found between the countries: staff education, substitute staff, acceptable work environment, separation of acutely disturbed patients, patient:staff ratio, and the identification of crisis triggers [Reference Bak, Zoffmann, Sestoft, Almvik and Brandt-Christensen19, Reference Bak, Zoffmann, Sestoft, Almvik, Siersma and Brandt-Christensen20].

Staff factors

Few studies reported on associations with staff or ward factors. A study in Japan of 7,074 admissions found restraint (and seclusion) was more likely in wards with more beds, more nurses, in acute wards, and in urban areas [Reference Fukasawa, Miyake, Suzuki, Fukuda and Yamanouchi47]. A Danish study of 259 admissions found an association with the male gender of care workers (OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.0–2.1) but no associations were found between restraint and staffing level, age, education, experience of care workers, or change of shifts [Reference Kodal, Kjaer and Larsen24].

Outcomes and acceptability

One randomized trial compared experiences of coercion with MR versus seclusion in an adult admission ward [Reference Bergk, Einsiedler, Flammer and Steinert34]. Patients were interviewed four weeks after the intervention and re-interviewed around 18 months later in a follow-up study [Reference Steinert, Birk, Flammer and Bergk35]. Factors most frequently cited by patients to alleviate the distress associated with restraint were contact with staff and having personal objects nearby. In the original study, there were no significant differences in experience of stress between the two groups, in adverse events, or in the level of experienced coercion. At follow-up, however, coercion ratings for MR versus seclusion were significantly more negative on six of the nine items.

A Danish national study examined all complaints received via their centralised system. Roughly one in six patients subject to MR filed a complaint, and for around one in 25 restrained patients, this was subsequently found to have been illegitimate when reviewed by authorities (typically as no violence or threat was demonstrated) [Reference Birkeland21]. Several studies quantitatively assessed patients’ experiences of coercion or trauma related to restraint. An Austrian study interviewed patients shortly after restraint. On visual analogue scales, patients considered themselves depressed and powerless during restraint, with fear relatively absent. Anger was markedly present during restraint but not in consecutive visits as psychopathology improved. Patients’ acceptance of the coercive measure was higher than expected, while patients’ memory was significantly lower. About 50% of the patients documented high perceived coercion, and PTSD could be supposed in a quarter of the restrained individuals [Reference Fugger, Gleiss, Baldinger, Strnad, Kasper and Frey94]. Another Danish study assessed 20 patients who had each experienced multiple MR episodes, and in this sample, interpretation of restraint episodes as central to identity was significantly related to higher PTSD symptoms [Reference Holm and Mors23]. Centrality of episodes also explained variation in PTSD symptom severity. A study in Spain of 111 people who had been restrained and/or involuntarily medicated found significant differences in experienced coercion, this being highest in combined measures followed by those who had been mechanically restrained [Reference Guzman-Parra, Aguilera-Serrano, Garcia-Sanchez, Garcia-Spinola, Torres-Campos and Villagran67].

Two studies examined rates of venous thromboembolism. In a German study in which 469 patients were restrained, none of the restraints (either prolonged, in which case patients are given prophylaxis with enoxaparin, or those lasting less than 24 hours, who are not given prophylaxis) were associated with deep vein thrombosis [Reference Hilger, von Beckerath and Kroger41]. However, a Japanese study including 660 case–control pairs of patients found that being in physical restraint for 15+ days was associated with increased risk of pulmonary embolism (OR 3.2, 95% CI 1.2–8.5) [Reference Hirose, Morita, Nakamura, Fushimi and Yasunaga48].

There was very limited reporting of measurable positive effects. Japanese data in patients with psychosis where seclusion with restraint was used reported favourable changes in psychosis and thought disorder as measured by the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) [Reference Eguchi, Onozuka, Ikeda, Kuroda, Ieiri and Hagihara46].

Impact of interventions, policy, or other changes

Among the 16 studies reporting the effects of changes (Supplementary 6, and Supplementary 7 for quality assessment), no significant effect was reported for moving to a new hospital building [Reference Harpoth, Kennedy, Terkildsen, Norremark, Carlsen and Sorensen29], use of an assessment tool for psychiatric inpatients diagnosed with mania [Reference Odgaard, Kragh and Roj Larsen31], sensory modulation [Reference Andersen, Kolmos, Andersen, Sippel and Stenager32], or peer support [Reference Badouin, Bechdolf, Bermpohl, Baumgardt and Weinmann45]. A study of implementing moral case deliberation (reflective practice) on two wards in Switzerland showed no significant decrease in the number of restraints, though the intensity of restraints (calculated using the duration) did significantly decrease [Reference Stoll, Westermair, Kubler, Reisch, Cattapan and Bridler55]. A Danish study of the implementation of the Safewards model showed no effect, but trends were already following a downward trajectory prior to the study period [Reference Stensgaard, Andersen, Nordentoft and Hjorthoj14], and another Polish study of Safewards did show a significant difference in the number of patients mechanically restrained [Reference Lickiewicz, Adamczyk, Hughes, Jagielski, Stawarz and Makara-Studzinska89].

Other studies showed the impact of legislative or policy changes. A Chinese study examining restraint before and after the implementation of a national mental health law found that restraint was independently associated with having been admitted before the law change [Reference An, Sha, Zhang, Ungvari, Ng and Chiu59]. In a German study, the introduction of the requirement for an immediate judge’s decision for any restraints lasting longer than 30 minutes was associated with a significant reduction in restraint (but an increase in seclusion) [Reference Flammer, Hirsch and Steinert38].

In eight Danish forensic units, a stepped-wedge cluster-randomised trial examined the implementation of the short-term assessment of risk and treatability (START) to reduce MR in male patients who displayed at least one aggressive episode [Reference Hvidhjelm, Brandt-Christensen, Delcomyn, Mollerhoj, Siersma and Bak30]. This was associated with a significant reduction in MR (RR 0.2, 95% CI 0.1–0.4). A cluster randomised trial of the implementation of de-escalation training in Slovenia was also associated with a reduction to 30% of the rate in the control group (incidence rate ratio [IRR] 0.3, 95% CI 0.2-0.4) [Reference Celofiga, Kores Plesnicar, Koprivsek, Moskon, Benkovic and Gregoric Kumperscak91].

Other studies examined the impact of more cumulative changes. A large Spanish study including data from over 17,000 people admitted described changes associated with a multicomponent intervention based on the “Six Core Strategies.” [Reference Guzman-Parra, Aguilera-Serrano, Huizing, Bono Del Trigo, Villagran and Garcia-Sanchez69] Comparing the first and last semester of the study, there was a significant reduction in restraint hours (by 33%), restraint episodes (by 6%), and proportion of patients restrained (by 8%). There was a significant decreasing trend in the total number of MR hours during the implementation of the intervention, but not in the number of episodes [Reference Guzman-Parra, Aguilera-Serrano, Huizing, Bono Del Trigo, Villagran and Garcia-Sanchez69].

Similarly, an American study described the impact over two 10-year periods of multiple measures, demonstrating a significant decline in the use of restraint in forensic centres in Pennsylvania [Reference Smith, Ashbridge, Altenor, Steinmetz, Davis and Mader78, Reference Smith, Altenor, Altenor, Davis, Steinmetz and Adair79]. During the decade to 2010, the rate of patient-to-staff assaults declined, though the rate of patient-to-patient assaults was unaffected. Leadership, data transparency, use of clinical alerts, workforce development, policy changes, and discontinuation of psychiatric use of as-required medication orders were all described as contributing factors [Reference Smith, Ashbridge, Altenor, Steinmetz, Davis and Mader78]. In the subsequent decade, seclusion and restraint were abolished entirely, and incidents of assault, aggression, and self-injurious behaviour significantly declined or were unchanged by the decreasing use of containment procedures [Reference Smith, Altenor, Altenor, Davis, Steinmetz and Adair79].

Qualitative studies

Findings from four included qualitative studies [Reference Gildberg, Fristed, Makransky, Moeller, Nielsen and Bradley33, Reference Chien, Chan, Lam and Kam60, Reference Aluh, Ayilara, Onu, Grigaite, Pedrosa and Santos-Dias98, Reference Walker and Tulloch99] are detailed in Supplement 8.

Discussion

This review represents the most extensive synthesis to date of published studies examining the use of mechanical restraint (MR) in inpatient psychiatric settings internationally. It addresses evidence gaps in previous work by using more exhaustive search criteria focussed on MR, and considering a full range of adult inpatient settings. In so doing, we have presented data from 73 different studies of mechanical restraint, substantially expanding on existing syntheses [Reference Chieze, Hurst, Kaiser and Sentissi4, Reference Gleerup, Østergaard and Hjuler7], which have either undertaken broader examinations of restrictive practice or focussed on the small number of comparative studies. We present four key summary findings from this new, comprehensive review with implications for clinical services, policymakers, and researchers.

First, for the first time assimilating prevalence data in this manner, we have demonstrated the extent to which MR in adult inpatient psychiatric wards internationally remains widely practiced. Individual studies reporting the prevalence of use since 2010 provide estimates ranging to an upper bound of 13% in Japan, 27% in a European setting, and 51% in China. This intervention thus requires regulation and a clear consensus on best practice to support frontline staff, who must consider complex ethical issues to balance autonomy, dignity, and safety [Reference Manderius, Clintståhl, Sjöström and Örmon100]. This guidance should be based on a robust appraisal of outcomes alongside human rights considerations. Prevalence varied widely between included studies, including between hospitals within the same countries and regions. Differences are therefore likely attributable in many cases to hospital-level policy variation.

Second, MR was broadly defined in most included studies as the use of belts or straps, with limited granularity in the description (e.g. manufacturer, exact materials), indications for use, and outcomes associated with different types of MR. Importantly, despite the widespread use, many included studies did not give a clear account of the specific indication for MR, compared with other forms of restrictive practice. Where this information was available, local policy, rather than clinical or other factors, appeared to guide practice. For instance, where one or other form of restriction was either preferred or was unavailable (such as in centres/regions in which seclusion rooms were not present), this appeared to largely account for any very low rates of use of one or other form of restriction in included studies. Local policy and legislation around approval and review may also account for the apparent variations in the length of time spent in restraint.

Third, studies provided limited insight into the influence of clinical and demographic factors. Factors such as younger age, male sex, and substance misuse were the most consistently associated with MR. This is understandable theoretically, given the overlap with established violence risk factors in psychiatric populations [Reference Lagerberg, Lambe, Paulino, Yu and Fazel101, Reference Whiting, Lichtenstein and Fazel102], and the finding that violence was typically defined as one of the main indications for MR in included studies. In acute settings, the early phase of admission was identified as a higher risk for MR. However, other potentially modifiable factors associated with the use of MR were examined to only a very limited extent, such as the impact of staff factors and shift patterns, which was reported in several studies, but without clear consensus. Such factors are likely to be highly unit-specific and are important to understand given they may lend themselves to being practically addressed. Language barriers and ethnicity or immigrant status were also identified as potentially important avenues for further exploration. The positive impact of strategies to develop staff skills in verbal de-escalation would seem to triangulate with the importance of communication in avoiding the need for MR.

Fourth, data regarding outcomes associated with MR was limited, while studies that compared MR directly with other forms of restriction in terms of outcomes were rare. Only one randomized study directly compared restraint with seclusion, and whilst post-intervention assessment of affected patients did not find a significant difference between groups, follow-up after 18 months found the restraint to be significantly less favorably regarded than seclusion. Findings from other studies of perceived coercion and PTSD symptoms also identified these as areas for consideration. Regarding physical sequelae of restraint, prolonged restraint was associated with pulmonary embolism risk but there was limited other reporting of physical health outcomes.

Implications for clinical practice and future research

Included studies highlight key areas that require further examination in both reviews of local clinical practice and future empirical research.

Detailed case-use mapping of the type, duration, and specific indications for restraint in different settings and diagnostic profiles should be a priority. Whilst risk to others broadly is the most frequently cited indication, a consensus around the typical scenario for which MR is of benefit over other forms of coercion is not well described, other than in extremis, in settings where other forms of coercion are preferred as the first line. References to the principles of collaborative risk assessment and management, which are increasingly seen as policy priorities, were notably lacking in included studies For example, instances where MR has been pre-planned or part of an agreed individual care-plan were not described in the included studies. Similarly, approaches to monitoring physical wellbeing whilst in restraint were not well described in the included studies and these need development and practical evaluation.

There was a suggestion in included studies that language, communication barriers, and ethnicity warrant exploration as potential risk factors. Such factors are likely to vary in their significance in local contexts, and so should be a focus for local clinical services as well as larger-scale research. Likewise, the relation of ward staff mix (gender, ratios, shift changes, and times of day) needs examination given evidence for their potential relevance to patterns.

High-quality studies of patient experience were limited and this should be a priority for future research [Reference Herrera-Imbroda, Carbonel-Aranda, García-Illanes, Aguilera-Serrano, Bordallo-Aragón and García-Spínola103, Reference Lindekilde, Pedersen, Birkeland, Hvidhjelm, Baker and Gildberg104]. Such work would benefit from being assessed as proximally to the restraint incident as possible to avoid recall bias, and the small number of included studies that used this approach demonstrated that this is feasible. Included studies did provide examples of best practice or factors that either reduced the need for or improved the experience of restraint that require further clarification and standardised implementation. These included processes for mandatory review or patient involvement, interaction style of staff, and frequency of contact during restraint, along with explanation and the presence of personal belongings. More broadly, staff permanency, ratios, and satisfaction were associated with lower levels of restraint and are of importance at a service level.

Positive outcomes (such as improvement in psychotic symptoms) were seldom reported in the included studies. Understanding these, as well as the reduction of negative outcomes such as assault, for an individual patient, compared with other forms of coercion, requires individualised consideration. Only one study examined staff experiences [Reference Walker and Tulloch99], and for an intervention that requires such direct physical involvement by staff, this is a significant knowledge gap that needs addressing.

Several studies reported changes that significantly reduced or even abolished MR. In keeping with the wider literature for reducing restrictive practice [Reference Väkiparta, Suominen, Paavilainen and Kylmä105], the nature of these interventions in included studies was heterogeneous, and evidence mixed. There was, however promising evidence for implementation of ward-level interventions such as de-escalation training or assessment tools where this was with the specific goal of reducing MR. Specifically targeted procedural changes, such as to the legal approval framework for ongoing restraint, also had a significant effect. Overall, there was an indication that rates of MR are sensitive to change in individual units. Such work however cannot be interpreted without understanding aligned changes in other forms of coercion. Further research is also needed to understand whether reductions are specifically attributable to the intervention or a general effect of increased scrutiny during such periods.

Conclusion

Mechanical restraint remains widely practiced in psychiatric settings internationally, though with considerable national and regional variation. Given the clinical and ethical implications, robust empirical support for its use is essential, and clinical policy should be evidence-led rather than based only on local conventions or facilities. High-quality studies remain scarce, especially those specifying the type of restraint, indications, clinical factors associated with use, and impact of ethnicity and language (of both patients and staff). Evidence for outcomes is even more limited, with little or no high-quality evidence of patient experience. These considerations should be research priorities, as such work has the potential to directly influence improved best practice guidelines. In limiting the use of mechanical restraint, some ward-level interventions show promise, however, strategies must be considered in the context of other restrictive practices, including seclusion. While abolishing mechanical restraint in psychiatry may not be realistic, there is evidence to suggest it is possible to improve the precision, safety, and effectiveness of its use. This should encourage further high-quality studies, which are imperative in aligning this practice with expected clinical and ethical standards of contemporary psychiatric care.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2025.2453.

Data availability statement

Data from included primary studies supporting the findings of this review are contained within the manuscript and supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Sadie Clare, Information Specialist, Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust for support with the literature searches.

Financial support

This review was supported by Health Innovation East Midlands.

Competing interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.