Introduction

In recent years, the question of the state of academic freedom in different countries has been the subject of increasingly intense discussions. The momentum gained in our times is due to the rising challenge to academic freedom in a global perspective, including in our European neighbourhood (e.g., Hungary and Poland; V-Dem 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023; cf. European Parliament 2024). In this article I will give an account of how academic freedom is undermined not because of illiberal ambitions, which are often at the centre of this type of analysis, but rather due to a lack of understanding for the specificity of the university by the political and administrative sphere. I will display and problematize the weak constitutional support of academic freedom in Sweden and give a historic account on how Swedish universities have increasingly come to resemble and be treated as ordinary government authorities, i.e., having ended up with the same legal status as the state. This represents a lack of institutional autonomy that is difficult to reconcile with the university concept. I will also show how this organizational anomaly has led to an escalation of political steering of the academic activities at Swedish higher education institutions (HEIs) during the last three decades. Hence, what will be unfolded here is how political and bureaucratic overreach can pose a very real challenge to academic freedom.

In order to study the constitutional anomaly that characterizes the organizational form of state universities, and thus the lack of regulation of academic freedom in the Swedish constitution, a careful analysis is required. My first task will thus be to chisel out the meaning of academic freedom both from the research literature and from how this freedom is presented in international agreements and legal documents. This will then form the conceptual framework of analysis that I will apply to the Swedish case. The fact that the Swedish constitutional and organizational solution stands out internationally is apparent from a comparative perspective. In recent years, extensive empirical analyses of the legal regulation of all dimensions of academic freedom have been carried out, and for this part I will mainly use Karran et al.’s comprehensive study of EU member states (2017) and the European University Association’s (EUA) evaluation of the autonomy of higher education institutions in the EU (EUA 2023). The legal status of academic freedom in Sweden will successively be contrasted with the actual scope of freedom, i.e., the actual circumstances under which Swedish HEIs and academic teachers and researchers operate today. In this latter part, it is impossible to be completely exhaustive, which is why a selection of current examples will be given that have to do with the HEIs’ institutional autonomy and the freedom of higher education and research. The data material on which the various parts of the analysis are based is primarily public documents and previous research with regard to the formal part, and to study the actual freedom I use contemporary discussions (via public documents and media) and previous studies of the government’s and Parliament’s governance of Swedish HEIs.

Two Dimensions of Academic Freedom

The concept of academic freedom is a recurring and positively charged concept in the world of higher education, and this freedom can be seen as the very prerequisite for academic activity. This is also apparent in the political rhetoric. It is not uncommon for various Swedish governments’ higher education policy bills to include the word ‘freedom’ in their headings, such as, for example, Higher Education Institutions – Freedom for Quality (Government bill 1992/93:1), Academia for our Time – Greater Freedom for Higher Education Institutions, (Government bill 2009/10:149) and in one of the latest research policy bills, Research, Freedom, Future – Knowledge and Innovation for Sweden (Government bill 2020/21:60). The question, however, is what kind of freedom is actually intended. Who should be given freedom? University management, higher education teachers and researchers – or someone else? And what does the balance look like between formal and the actual scope of freedom? I will return to these questions. But first, let’s clarify what the concept of academic freedom itself includes.

It should be emphasized the great importance academic freedom has in ensuring the ability to seek knowledge freely at higher education institutions – that is, as a prerequisite for free search for, and dissemination of, knowledge to be able to occur, regardless of how such knowledge is received by political, economic or other interests. This is well captured by a frequently cited definition which states that academic freedom is ‘the freedom to conduct research, teach, speak and publish, subject to the norms and standards of scholarly inquiry, without interference or penalty, wherever the search for truth and understanding may lead’ (UN Global Colloquium of University Presidents 2005). In this definition, academic freedom is linked solely to the individual level, i.e., to the individual researcher or teacher; but there should also be a focus on the institutional level. In the literature, the concept of academic freedom is linked partly to higher education institutions and partly to individual academic researchers and teachers (Karran et al. Reference Karran, Beiter and Appiagyei-Atua2017; Nokkola and Bladh Reference Nokkala and Bladh2014). The former refers to the institutions’ scope for self-governance – for example in relation to the government, Parliament and the market – while individual academic freedom refers to the right to professional self-determination in teaching and research that is assigned to the individual teacher and researcher.

Several major international agreements and conventions on academic freedom also emphasize the importance of both institutional autonomy and individual academic freedom. One example is the Magna Charta Universitatum, which was signed when the University of Bologna celebrated its 900th anniversary in 1988 (Magna Charta Universitatum 1988); a new version was adopted in 2020. Both versions underline the importance of institutional autonomy and individual academic freedom; that research and teaching must be free from political, ideological and economic interests; that teaching and research must not be separated; and that universities and state authorities have an obligation to respect these basic requirements (Jonsson Cornell and Marcusson Reference Jonsson Cornell and Marcusson2022).

What institutional arrangements are then required to ensure a real independence for academic activities? Two critical parameters for institutional autonomy are that the activities must have support in legislation and sufficient financial resources (Ahlbäck Öberg, Reference Ahlbäck Öberg, Björk, Bolkéus Blom and Ström2011). This is also something that has been emphasized in recent decades in several overarching policy documents on the status of higher education institutions. In 2006, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe adopted a recommendation on academic freedom and university autonomy, which emphasizes, inter alia, that the academic freedom of teachers and researchers and the institutional autonomy of universities should be confirmed and guaranteed by law, preferably by a constitution (PACE 2006: Recommendation 1762, paragraph 7). Thus, it follows from this recommendation that academic freedom also includes an institutional and organizational dimension, as being part of an infrastructure is a fundamental prerequisite for teaching and research. A recommendation of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe states that public authorities should provide a framework for academic freedom and institutional autonomy and monitor the implementation of these fundamental rights on an ongoing basis (Council of Europe 2012). This recommendation also emphasizes that financial autonomy is an important precondition for institutional autonomy. The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (EU 2010) requires respect for academic freedom, which each Member State should specify in law and preferably in its constitution.

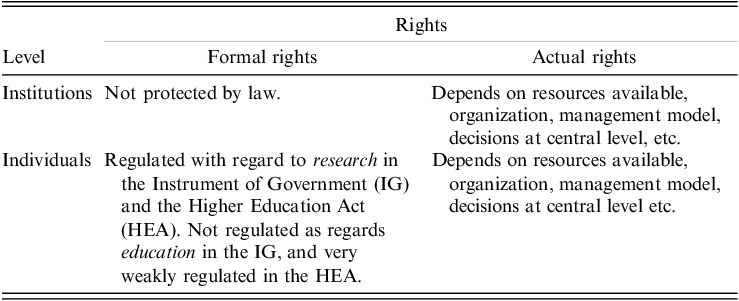

Based on this reasoning, we can identify some interesting questions of principle. At both institutional and individual level, it is important to distinguish between freedom as a formal right to self-governance and freedom as genuine scope to act freely. A lack of key resources, (e.g., time to conduct research), often limits researchers’ (actual) capacity to utilize their (formal) right to choose subjects and methods and to present results. On the other hand, there may be laws, regulations or research ethics standards that exclude projects that a researcher otherwise has the necessary resources to conduct (Norwegian Government Official Report, NOU 2006:19).

Table 1 captures the different dimensions of academic freedom by distinguishing between the freedom of the institution and the freedom of the individual, and by differentiating between the formal right to self-governance and the real scope for academic freedom. In what follows, I will discuss the current situation in Sweden with regard to what is formally prescribed and what the actual scope to act freely looks like.

Table 1. Freedom as the formal right to self-governance and freedom as real scope to act freely (in the Swedish context; adapted from Norwegian Government Official Report, NOU 2006:19, p. 13).

Institutional Autonomy

With regard to the formal right to self-governance, Table 1 shows that the support in Swedish legislation is very weak, i.e., there is no formal regulation when it comes to institutional autonomy – which refers to the relationship of higher education institutions to the state and society – for state higher education institutions. This was highlighted in a study in which the legal regulation of the institutional autonomy of higher education institutions in all EU countries was compared and where Sweden ranked in 26th place out of 28 (Karran et al. Reference Karran, Beiter and Appiagyei-Atua2017, Table 12; see also Nokkola and Bladh Reference Nokkala and Bladh2014). Although higher education institutions as organizations have been given an increasingly prominent role in Swedish higher education policy – through various decentralization reforms – we can see that this has not been accompanied by corresponding guarantees regarding the institutions’ autonomy (Marcusson Reference Marcusson2005).

A complicating factor in the Swedish context is that higher education institutions which are currently run under the auspices of the state, which is the majority, are formally part of the Swedish public administration system and are thus state authorities. This is precisely what stands out in international comparisons, and it provides an important explanation for why Sweden ranks poorly in terms of institutional autonomy compared with other EU countries. It is easy to see that this stated subordinate relationship to the government does not chime well with ideas regarding autonomy for higher education institutions (cf. SOU 2008:104). Although it is reasonable that publicly funded research and education is conducted responsibly and thus subject to transparent examination, the activities of free academia require a clear dividing line in relation to the state, not a subordinate relationship.

This has also been raised by several inquiries and actors over the years (SOU 1996:21; SOU 1997:57; SUHF 2021b; Åmossa and Ericsson Reference Åmossa and Ericsson2021). These views have not received the support of the Parliament and the government. In several parliamentary bills, proposals for a new organizational form for state higher education institutions have been explicitly rejected by Governments (see for example Government bills 1996/97:141 and 2009/10:149), and a recurring argument is that the state authority operational structure is perceived as sufficiently ‘flexible’ for university activities that require autonomy.

What is more, the observation on the legal status of Swedish HEIs comprises a central question that has not been sufficiently addressed: how is it that the absolute majority of Swedish higher education institutions have fallen into the category of state agency, that is, given the same legal status as the state? The answer is that this, in many ways strange state of affairs, is never the subject of proper discussion, and on closer inspection it does not appear to be the result of a thoroughly considered principle-based decision by our ruling politicians. In other words, the basis for the organizational form of state universities has never been properly examined. There has never been a decision in principle that our public sector universities should be state agencies, but this has simply been a ‘logical’ consequence of a series of other decisions. Hence, what does emerge on closer analysis is that, over the course of more than 150 years, the state authorities have gradually transformed free academies into state institutions and later administrative authorities (see Committee Directives 2007:158, p. 3; Frängsmyr Reference Frängsmyr2010). The universities in Uppsala and Lund have a long tradition of great self-determination, including previously as separate legal entities with ownership rights to property donated to the universities. Following a decision by the state, these properties are now owned by foundations which are managed by the universities. At the end of the nineteenth century, non-state colleges were established in Gothenburg and Stockholm, which were transformed into universities in 1954 and 1960, respectively, and were consequently turned into state institutions. This change of legal personality was implemented without much debate. The backdrop was increased state funding and subsequent demands for state influence over operations (Gribbe Reference Gribbe2022: 125).

Universities were long considered to be independent legal entities (Sunnqvist and Wenander Reference Sunnqvist and Wenander2018: 567). This was because the universities were stated in their statutes, and still in the Royal University Statute of 1956 (SFS 1956:117), to be ‘under the protection of Majesty the King’ and enjoyed ‘unwaveringly the property, income, rights, benefits and freedoms’ which legally belonged to them (2 §, 1 point). This was changed with the Royal University Statute of 1964 (SFS 1964:461), where this protective formulation was removed without further discussion by both the government commissioned inquiry and the Government regarding the radical fundamental consequences of such a decision (SOU 1963:9, pp. 437−438; Government bill 1964:50). Hence, in the University Statute of 1964, and also in the Higher Education Acts of 1977 and 1993 respectively, there are no articles on the legal status of universities.

With the introduction of the new Instrument of Government in 1974, universities and colleges, like hundreds of other state institutions, became administrative authorities under the government (SOU 2008:104, p. 62). The new form of government thus codified the state higher education institutions’ form of operation as administrative authorities. As Sunnqvist and Wenander (Reference Sunnqvist and Wenander2018) have explained, this was done by emphasizing the distinction between public and private in the legal system in the preparatory works (see in particular SOU 1972:15, p. 123). While older law had accepted that there were intermediate forms such as public law corporations, the constitution was now based on a strict dichotomy between private and public. The new constitutional system is thus based on bodies being regarded as either public or private without, with a few exceptions, any possibility of intermediate forms (Sunnqvist and Wenander Reference Sunnqvist and Wenander2018; see also Strömberg Reference Strömberg1985). The consequence was thus that various types of government institutions were categorized as administrative authorities, and public sector higher education institutions belong to this group. There was no fundamental discussion of the fact that universities and university colleges could be seen as a special type of organization with greater requirements for independence.

The diffusion of the unique status of higher education institutions among state administrative authorities continued with decisions on matters such as external representatives on the universities’ board of trustees (1977), external majorities on the board of trustees (1988), external chairs of the boards of trustees (1998) and the deregulation of faculty boards (2010). Previously, professors’ powers of attorney were an important instrument for maintaining academic freedom against demands from external sources such as the government, but this power was abolished in 1993. These latter reforms have gone hand in hand with general administrative policy trends – i.e., public management policy applied to all central government agencies. What I expose here is the erasing of the academic distinctiveness among public authorities: universities have successively turned into being just like any government agency.

The fact that the state higher education institutions’ status as state agencies is not the result of clear and transparent political considerations is troubling. It shows that the academic activities at Swedish universities and colleges that require independence have been allowed to slide into a relationship of subservience to the state without any discussion of the principle, and where the political and bureaucratic understanding of the real meaning of what free academia is has been gradually overshadowed by this institutional weakness. This has had both structural and cultural consequences. For instance, nowadays it is often repeated within Swedish HEIs that they work as a government agency, refer to their Vice-Chancellors as Directors General (agency heads) and provide training to staff in civil service ethos (den statliga värdegrunden) rather than academic norms.

The weak institutional autonomy of Swedish state higher education institutions also shines a spotlight on another institutional aspect that needs greater scrutiny, namely the internal decision-making processes at HEIs. The internal division of power between the management (line management) and academic representatives (collegial management) has traditionally been the recipe for ensuring the self-determination of the core academic activities of teaching and research (Sahlin and Eriksson-Zetterquist Reference Sahlin and Eriksson-Zetterquist2016). There has always been tension between these two management principles and, in reality, we can therefore speak of a kind of power sharing at higher education institutions (Engwall Reference Engwall2017). If the institutions are government authorities, there is an even greater need for internal processes that protect decisions about the academic content of research and education from direct political control in order to ensure both institutional autonomy and individual academic freedom. However, the collegial management system has been subject to deregulation through the so-called Autonomy Reform of 2011 – i.e., the legal support for collegial decision-making within HEIs was deregulated – which has further added to the institutional vulnerability of the academic activities of state higher education institutions. Hence, following the Autonomy Reform, the managements of higher education institutions now decide whether there should be collegial decision-making bodies and what powers these should have. At the same time as the legislative support for the collegial form of governance was abolished, Vice-Chancellors and university boards continued to have strong positions as they retained – and in several cases expanded – their powers. The balance between the line management and the collegial management has thus been tipped constitutionally in favour of the former, and research shows that an actual process of ‘decollegialization’ has taken place at Swedish HEIs. That is, the institutional expression of academic freedom and decision making based on scholarly competence, through collegial decision-making bodies, has been significantly reduced at most of the state higher education institutions, although there are significant differences within the sector. At many higher education institutions, there are hardly any ‘islands of collegiality’ remaining, because both the principle of power sharing and the idea of collective decision making based on subject expertise are expressed more weakly, and in some cases not at all. Overall, it was found that a reform based on a stated goal of decentralization had actually led to greater local centralization – the autonomy offered by the reform was autonomy for the managements of the higher education institutions (Ahlbäck Öberg and Boberg Reference Ahlbäck Öberg and Boberg2023).

It should be emphasized that the fundamental organizational vulnerability of state higher education institutions in terms of institutional autonomy, such as their status as state agencies, makes this deregulation especially imprudent. It is a fallacy that academic freedom can be expected to come into being through non-binding general statements and requires no legal protection. Such an unregulated approach has never been considered with regard to other basic individual freedoms and rights in modern democracies.

Individual Academic Freedom

So far, the focus has been on institutional autonomy and its importance in enabling individual academic freedom. The outcome for Sweden so far has not been encouraging, despite all the signed international legal commitments and recommendations. But what is the situation with regard to individual freedom? As Table 1 shows, only the freedom of research is currently regulated by fundamental law in Sweden, and this protection was introduced as late as 2010 at the initiative of the Swedish Committee on Constitutional Reform (SOU 2008:125). The chapter of the Instrument of Government that regulates individual freedoms and rights, (Ch. 2, Art. 18, second paragraph), stipulates that ‘Freedom of research is protected according to provisions issued by law’. This freedom is specified in the Higher Education Act (Ch. 1, Art. 6, second paragraph):

The following general principles shall apply to research

-

1. research problems may be freely selected,

-

2. research methodologies may be freely developed, and

-

3. research results may be freely published.

However, there is no corresponding regulation of the freedom of higher education. It may seem remarkable that such a protection for the freedom of education did not come into being when the protection for the freedom of research was introduced. One can reasonably wonder why one of academia’s main activities was omitted. The political governance of Swedish higher education is also striking in some respects in a comparative perspective. It does not seem reasonable to assume that this aspect was not regulated because higher education faces no threats. However, the question of the freedom of higher education does not seem to have been a matter for discussion in the Committee’s work in this regard.

Admittedly, formal regulation does not necessarily guarantee that what is prescribed actually occurs, but it would still be a decisive step if the special nature of universities and colleges were more clearly established in the constitution, thus reinforcing the protection of academic freedom in Sweden. The tendency in the reality of politics to limit, for example, the freedom of research and higher education is currently evident in several ways and will be exemplified in the following.

Research

Free research depends on adequate funding, and financial autonomy is a key aspect of international comparisons of academic freedom and autonomy (see, for example, EUA 2023). However, the Commission Inquiry on Governance and Resources found that, over time, direct institutional funding of research to HEIs has declined overall in relation to external research funding, from 68% in 1981 to 44% in 2017 (with large variations between HEIs). The report recognizes that international comparisons of the level of external funding are complicated by the fact that conditions in different countries differ in several respects. However, it is pointed out that several analysts believe that the Swedish level of external funding is high in an international comparison (SOU 2019:6, pp. 264−265). The high dependence on external research funding causes several problems. At the HEI level, it means that there is no real financial room for manoeuvre, which is in fact a central part of the HEIs’ autonomy. For individual teachers and researchers, the low proportion of research in their permanent positions is a problem, not least in terms of the time that must be spent on constantly applying for external funding.

In addition, external funding via government research funding organizations has become increasingly targeted. It is clear from the government research councils’ letters of appropriation over time that the various governments’ control of the content of research has increased in recent decades (appropriation letters for Swedish Research Council, Swedish Research Council for Environment, Agriculture Sciences and Spatial Planning, and Swedish Research Council for Health Working Life and Welfare, https://www.esv.se/statsliggaren/). It is, of course, not unreasonable for the government to call for research on topics that are perceived as important or urgent. However, in recent years’ letters of appropriation to the government research councils, long and detailed lists of instructions from the government can be read, specifying the more precise research purpose for which the allocated funds are to be used. This development thus poses a direct threat to what we value in independent research. Both the fact that, by Nordic standards, Swedish academic teachers and researchers have little research in their employment contracts (Brommesson et al. Reference Brommesson, Nordmark and Ödalen2024) and the tendency for governments to increasingly direct research funding makes it difficult to live up to the conditions for independent research laid down in existing legislation.

Another current example is the tightening of the application and supervision of the 2020 Ethical Review Act, which imposes limits on the content and methods of free research. In the Swedish case, the government and parliament have chosen to model ethical review on the biomedical model – including for the humanities and social sciences – and have placed this assessment and standard-setting of the boundaries and application of research ethics in an authority outside academia. In an international comparison, it is a strange arrangement to place the non-medical research ethics assessment outside academia (Johansson et al. Reference Johansson, Bülow, Persson and Wahlberg2023), and to some extent in the hands of people who are not active researchers themselves. The formation of norms on such an important issue as research ethics is thus ‘outsourced’. This organization has had very far-reaching consequences (Persson et al. Reference Persson, Bülow, Johansson and Wahlberg2023). In the criticism that has followed the 2020 tightening of the ethical review system, the question of where the line is drawn for sensitive personal data is often raised. A telling example is that ethics approval is required to use the Swedish Parliament’s open data or to debate articles written by representatives of political parties, as these contain sensitive personal data in the form of political opinions. For example, ethics approval must be sought to conduct a discourse analysis of Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson’s public speeches (an analysis that any journalist can do without ethics approval). Through extensive bureaucratization, we currently have an ethical review system that severely restricts free research. Such a system can only arise in a context where the higher education institutions are treated as ordinary administrative authorities, from which it follows that the legislator perceives it as reasonable that research activities are regulated by law and controlled by other authorities (Ahlbäck Öberg and Boberg Reference Ahlbäck Öberg and Boberg2024). The protests against this control of research are and have been massive in the research community (see above all Dagens Nyheter 2023; Sundell Reference Sundell2024 for a current discussion). This has led to the government now investigating exemptions from the requirement for ethical approval for certain research and the regulation of supervision in the Ethical Review Act (Ministry of Education and Research 2023). However, what will come out of this remains to be seen.

Higher Education

Although the detailed governance of higher education from older times has lessened, there are today several examples of different governments’ clear desire to intervene. One example of political involvement at a highly detailed level that is often mentioned in these contexts is the Swedish System of Qualifications (examensordningen). Here, the government not only determines which degrees may be issued by Swedish higher education institutions, but it also regulates which qualitative goals each student must fulfil in all educational programmes leading to each degree. While the general qualifications contain more general goals, vocational degrees are regulated in significantly greater detail. This means that the government, through the System of Qualifications, in practice also regulates the content of the education (SUHF 2021a).

Another example of political governance is provided by the Swedish Higher Education Authority (Universitetskanslersämbetet, UKÄ) which, in a report, highlights that the government is increasingly identifying which education programmes are to be prioritized when state grants are increased, even in case of temporary increases (UKÄ 2015). In addition to the fact that this restricts the freedom of higher education institutions to plan their own education, it makes the higher education institutions – and thus those who conduct the teaching – vulnerable to political instability, which in itself counteracts long-term and, from a teacher’s perspective, sustainable planning. The Higher Education Authority quite rightly points out that it takes time to build up an educational programme, both to design courses and to recruit teachers. There may also be shortages of teachers in subject areas that everyone suddenly has to prioritize. The report identifies short-term political goals, with their prioritizations of different subjects and programmes, as a particularly large problem – and a problem that has grown over time (UKÄ 2015).

We find further examples of the lack of demarcation between politics and academia when we study political agreements signed when governments were formed following the general elections of 2018 and 2022. In both the January Agreement (2019) and the Tidö Agreement (2022), we find wordings that undoubtedly imply political control at a detailed level, i.e., interference, with regard to academic freedom in higher education. In the January agreement, the signatories, (the Social Democratic Party, the Centre Party, the Liberal Party and the Green Party), stated that teacher training was to be reformed (2019, p. 13):

56. Reforms within teacher training. The requirements regarding the teacher training educational programme will be tightened. Admission requirements will be raised. More teacher-led hours will be introduced and the connection between theory and practice will be reinforced and the focus on methodology increased[.] The conditions for graduates to choose the teaching profession will be made simpler. The length of supplementary teacher education (KPU) programmes will be reduced and the pace of study increased. Opportunities to combine working at a school with teacher training programmes will be expanded. Sex education will be a mandatory component of teacher training programmes, as well as knowledge of neuropsychiatric disabilities.

In the Tidö Agreement (2022), the Moderate Party, the Sweden Democratic Party, the Christian Democrat Party and the Liberal Party state that ‘Bachelor of Science programmes in social work will be reformed to include juvenile crime as a mandatory component. Specialization in juvenile crime will be introduced in the programme’ (Tidö Agreement 2022: 27). This agreement also contains directives on what the teacher training programme is to include (Tidö Agreement 2022: 52). There is thus no reason to hope that politics will automatically maintain a respectful distance from what is reasonably assumed by the concept of academic freedom when it comes to the content of higher education. The need to introduce constitutional protections for academic freedom in higher education in Sweden has been highlighted jointly by the Swedish National Union of Students, the Association of Swedish Higher Education Institutions and the Swedish Association of University Teachers and Researchers (Svärd et al. Reference Svärd, Adolfsson and Wolk2023).

In addition, when it comes to this individual level of academic freedom, Sweden ranks very poorly in the table of the countries included in the Karran et al. (Reference Karran, Beiter and Appiagyei-Atua2017, Table 12) study. Admittedly, there is a general statement in the Swedish constitution about academic freedom for research, but the overall rating suffers from the fact that higher education is not covered, and the scant wording in the constitution regarding the freedom of research. It should be noted that academic freedom was not included in the Higher Education Act when the study was conducted. On the other hand, there are several instances of vagueness in the new regulation from 2021, such that it is uncertain whether the grade would have been so much higher in this part. Only the HEIs were tasked with promoting academic freedom – without further specification of its meaning – while the state, for its part, does not commit to anything in this respect in relation to the HEIs (Government bill 2020/21:60; Higher Education Act, Ch. 1, Art. 6).

Conclusion

As presented above, the protection of academic freedom in the Swedish constitution is not sufficient, and this state of affairs has enabled reforms and governance that together undermine rather than support the institutional autonomy of state HEIs and the academic freedom of teachers and researchers. It is not enough for politicians to talk about – or defend in words – the idea of academic freedom, if real reforms to support this freedom are lacking or if the content of key reforms even works in the opposite direction.

The fact that state HEIs have the same legal personality as other administrative authorities is a problem, and also a starting point that can be strongly questioned, given that a proper and elaborate decision on the organizational form (legal status) has never been taken. Moreover, as mentioned above, it represents a departure from what can now be claimed under EU legislation. The fact that the current form of operation is a problem has also been pointed out over the years by several investigations and stakeholders (see, for example, SOU 1996:21; Strömholm Reference Strömholm1996; Marcusson Reference Marcusson1997; SOU 1997:57; SUHF 2021b; Åmossa and Ericsson Reference Åmossa and Ericsson2021; Ekberg Reference Ekberg2024). These views have not been heard by the Riksdag and the government. In several bills, proposals for a new organizational form for state universities have been explicitly rejected by governments from both blocs (see, for example, Government bills 1996/97:141 and 2009/10:149), and a recurring argument is that the form of government agency is perceived as sufficiently ‘flexible’ for the universities’ activities demanding autonomy. In many of the reforms that higher education has undergone from the 1970s onwards, the subtext has thus been that the Swedish administrative model has been sufficiently adaptable to accommodate all kinds of autonomy-demanding government activities.

In the case of HEIs, the interface between politics and HEI activities has thus been based on an idea of an invisible contract, where the autonomy of state HEIs has rested on the assumption of political restraint and self-commitment, not on robust institutional structures. However, the constitutional practice on how to deal with autonomy-demanding public activities that have developed in a more consensus-oriented era is not sufficient when there is increasing disagreement about what constitutes established practice and whether it should be followed at all (see Beckman Reference Beckman2021). For what happens when disagreement arises over the content of the contract? In our time, the contemporary discussion on shortened terms of office for university boards – allegedly to ‘ensure security policy expertise’ – is an excellent illustration of the potential for politicians to reinterpret the informal contract to their own governance advantage (Government decision 2023).

To summarize, the political speeches about academic freedom ring hollow. The invisible contract between the state and universities that has previously applied is now inadequate. More proper constitutional regulation is needed to secure the guardrails of academic freedom and to create the respectful distance between politics and academic activity that international agreements and legal instruments require. A government-commissioned inquiry noted that securing such a margin is far more than a group interest for academics and intellectuals: ‘Scientific freedom is a crucial prerequisite for the cultural climate, for the health of democracy, for the dynamism of the economy and for the development capacity of society as a whole’ (SOU 2008:104, p. 65).

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the guest editor of the journal, Professor Lars Engwall, for his help and valuable comments on this text. I would also like to thank Karin Åmossa, Head of Research and International Affairs at the Swedish Association of University Teachers and Researchers (SULF), who inspired me to start researching this topic (see Ahlbäck Öberg Reference Ahlbäck Öberg2023).

About the Author

Shirin Ahlbäck Öberg is Professor of Political Science in the Department of Government, Uppsala University. Her research interests include public administration and management, and how NPM reforms have challenged professionalism and public ethos in the public sector. In recent years, she has researched university governance and the political steering of the university sector. Ahlbäck Öberg holds a position as Deputy Director of the Centre for Higher Education and Research as Objects of Study (HERO), Uppsala University.