Introduction

Austin’s introduction of the term ‘performativity’ in his lectures between 1950 and 1957, and their subsequent publication in 1962, marked a significant turning point in intellectual history, emphasizing how representational interventions make things in social life (Crary, Reference Crary2002). In subsequent years, performativity emerged as a profoundly interdisciplinary and captivating subject in social science and philosophy. Initially rooted in linguistic philosophy, the concept gradually permeated the fields of comparative literature, performance studies, sociology, anthropology, geography, management sciences, education, political science, history, musicology, gender studies, feminist studies, and queer studies. Consequently, a rich body of performativity studies began to flourish across various academic disciplines, with the partial exception of economics. It is remarkable that practically every area within the realm of the social sciences, philosophy, and humanities has seen scholars actively engaged in exploring or utilizing the concept of performativity.

The proliferation of approaches enabled by performativity has sparked excitement and creativity. Like other successful concepts, such as social capital and financialization, performativity’s accomplishments also led to fragmentation, incoherence, and the absence of a programmatic agenda. These challenges can be seen as symptoms of an excessive reliance on this concept, necessitating a cautious approach attentive to its limits – conceptual, empirical, and strategic, among others. However, they may also present an opportunity to embrace a more integrative approach, one that offers more theoretical work to deprovincialize performativity from the confines of individual disciplines. The Devices, actors, representations, or network (DARN) framework, introduced in this paper, responds to this opportunity by offering a systematic way to analyze performative processes through four interconnected components: Devices, Actors, Representations, and Networks. By focusing on these elements, the framework reconciles performativity’s diversity while addressing its conceptual fragmentation. The main goals of this paper are to connect rather than isolate phenomena, draw attention to the distributed and relational nature of action, and examine how action is shaped by representational interventions.

In our view, this integrative effort aligns with the very spirit of Actor-Network Theory (ANT), one of the foundational theoretical perspectives in performativity studies. Despite performativity being fundamental, at least implicitly, to ANT itself, ANT has not been used explicitly for the task we undertake here: to analyze studies of performativity and theorize its variations. ANT is of course contested terrain. What we see as ANT’s rich, polymorphic, and heuristic (rather than theoretical with a capital T) nature can strike critics as strategic ambiguity (Collins, Reference Collins2010), catch-all theory that can be used to account for just everything (Whittle and Spicer, Reference Whittle and Spicer2008) and underemphasis on relations of power (Elder-Vass, Reference Elder-Vass2015). Even ANT’s co-founders have expressed ambivalence about it, with Bruno Latour declaring that ANT was neither about A and N nor T itself (Latour, Reference Latour1996), before then returning to the term – with a second hyphen added (Latour, Reference Latour2005). Even Michel Callon, to our knowledge the original formulator of the notion of ‘actor-network’ (Callon, Reference Callon, Callon, Law and Rip1986), has largely stepped back, for example, employing the term explicitly only in passing in a major statement of his views on markets and economies (Callon, Reference Callon2021: 358).

Instead, Callon (2006; Reference Callon2021) has developed and deployed the term ‘socio-technical agencement’ and theoretically located its constituents. Callon’s notion of an agencement is a rich one and cannot be explored in depth here. Briefly, however, it is a specific combination of human beings and non-human entities that is endowed with the capacity to act. The approach that we take here builds upon this work by Callon (Reference Callon2021; see also Caliskan et al., Reference Caliskan, MacKenzie and Callon2024; Reference Caliskan, MacKenzie and CallonForthcoming). We view agencements as constellations of four types of entities, all with potential agential capacity: devices, actors, networks, and representations.

This, again, is heuristic, not ontological: we do not posit ontological differences between devices, actors, networks, and representations. We suggest that these four elements, all – to repeat – with potential agency, should be the focus of social research to explain and analyze distributed action (Caliskan et al., Reference DourishForthcoming). Caliskan and Wade (Reference Caliskan and Wade2022a, Reference Caliskan2022) originally developed this approach, modifying actor-network theory’s original acronym by dropping the T, and adding D (for devices) and R (for representations). The resultant verb, ‘DARN’, invokes ad-hoc material repair, and, generalizing from that, captures one of Actor-Network Theory’s foundational insights, which we might call ontological bricolage: the all-pervasive, always ad hoc construction of reality from heterogeneous elements.

Caliskan and Wade (Reference Caliskan and Wade2022a, Reference Caliskan and Wade2022) employed DARN to analyze the components of formal organizations and to develop a design method for human actors to intervene in agencement contexts. In this paper, we demonstrate that DARN works effectively to analyze performativity literature with rigor, making visible layers of empirical variation as well as making it possible to theorize common threads in this vast research site. Furthermore, this methodological elaboration and tightening can also help address potential problems of conceptual stretching (e.g. Sartori, Reference Sartori1970) that too easily slip into catch-all approaches.

Reconsidering the concept of performativity through the descriptive and analytical lens of the DARN framework, we define performativity as a representational intervention that alters a socio-technical agencement by influencing one or more of its constituents: DARNs. More specifically, we introduce four distinct modes of performativity, illustrating how devices, actors, representations, and networks emerge as dynamic, performative achievements resulting from material acts of representational interventions, which are subject to ongoing political and scientific contestations.

The development of the modes of performativity unfolds progressively throughout the paper, with each section building upon a robust theoretical and empirical foundation. We begin by presenting an empirical analysis that demonstrates the theoretical and practical applications of performativity across a wide range of disciplines, interpreting the findings in terms of the expansion, consolidation, and fragmentation of the existing scholarship. Building on that, we introduce four distinct ‘modes of performativity’ and elaborate on how the DARN framework offers both theoretical depth and methodological precision for examining these modes. The paper concludes by emphasizing the broader scientific significance of analyzing performativity in its various modes, reflecting on the potential of our meta-theoretical lens to enrich the performativity-oriented social research and foster inter/trans disciplinary engagement.

Emergence and distribution of performativity: Bibliometric evidence

By the end of December 2022, over 3,532 articles with ‘performativity’ in the title had been published, and more than 6,741 papers and books used the concept for a variety of analyses. In this section, we employ a heterodox methodological approach that combines hermeneutical interpretive study with computational text analysis, pursuing two key research objectives.

First, we utilized computational text analysis to uncover two key insights: determining the relative frequency of terms used within the literature, and performing a bibliographical analysis to identify the authors who are frequently referenced, thereby observing the relative trends and consolidations within the literature. We know that performativity, as it evolves into a multidisciplinary research agenda, runs the risk of losing coherence and consistency. Our efforts at providing an integrative perspective must therefore begin with a search for evidence of identifiable citation patterns that can help us flesh out shared research trajectories. By drawing on these analyses, we offer a snapshot of the performativity literature that visualizes the research landscape, focusing on authors who explicitly use and actively develop the term in their academic work.

Secondly, we read and carried out an interpretive analysis of all papers, books, and book chapters with ‘performativity’ in their titles spanning from 1962 to 2023 from our main corpus of 3,532 scholarly works. We downloaded and classified all these contributions according to topic (e.g. gender, economic sociology, etc.), consistent with our bibliometric analysis of a larger corpus. Each work was read by at least one author of this study. Studies that were deemed representative of a broader distribution of positions within a topic were then discussed and interpreted collectively in more depth. The year 1962 was selected as our baseline because of the publication of Austin’s groundbreaking How to Do Things with Words, which catapulted the concept into the limelight. Through scrutinizing the extensive array of disciplines, including philosophy, sociology, gender studies, comparative literature, and beyond, in which performativity has been developed and deployed, our study sheds light on the multifaceted ways the term has evolved and been applied across both theoretical and empirical contexts.

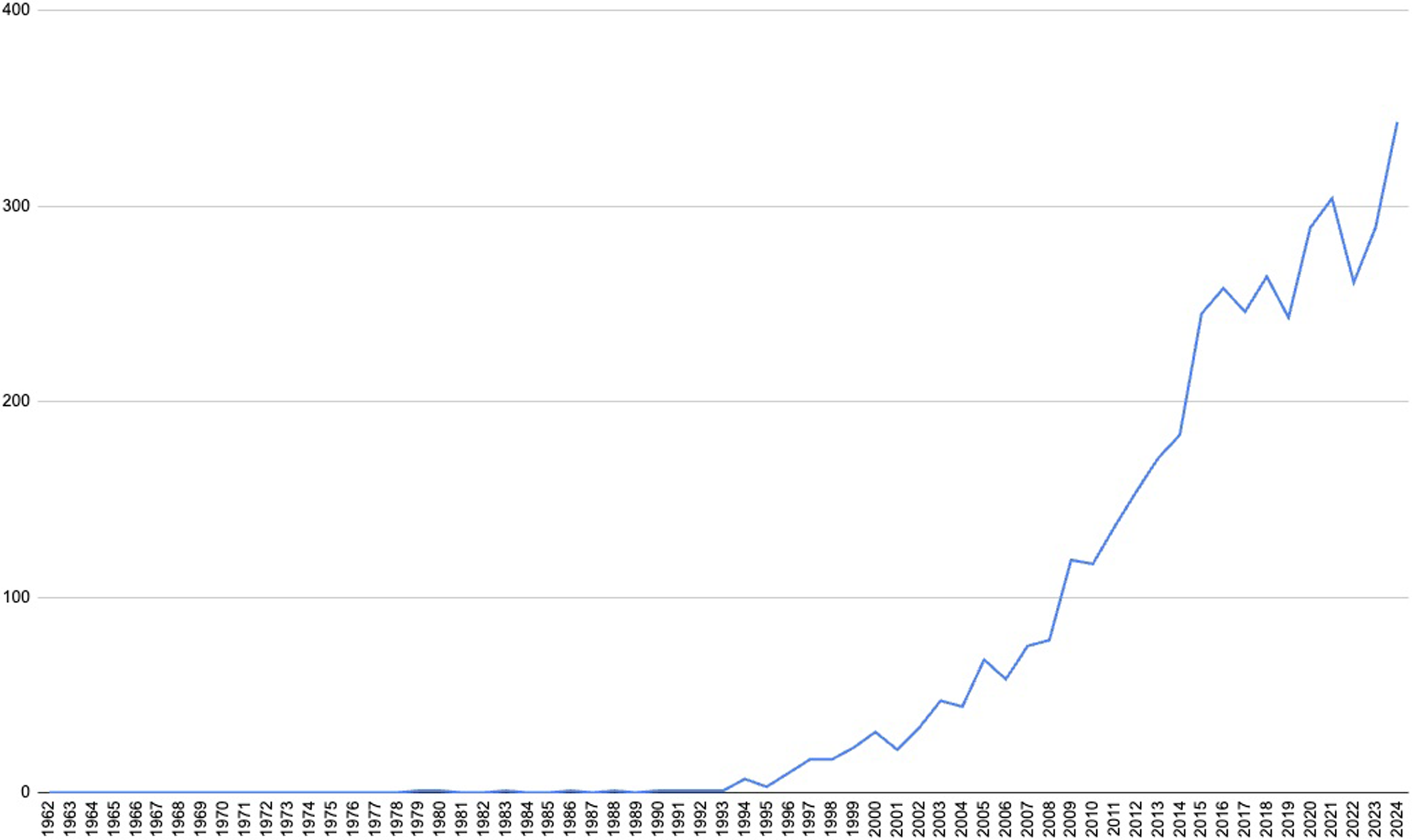

Figure 1 maps the term’s rise in scholarly literature. For the two decades leading up to 1992, performativity was primarily a niche concept in linguistic philosophy. The final decade of the twentieth century heralded a transformative phase, positioning performativity as a pivotal research theme in both gender studies and economic sociology. Following this Big Bang of performativity in research, we observed its extensive incorporation across almost all disciplines within the social sciences and humanities. Intriguingly, economics, a discipline often shown to have a profound performative power (Callon Reference Callon1998, Reference Callon2021; Mitchell, Reference Mitchell1998), appears reticent in explicitly embracing the very concept that underscores its role in socio-technical design.

Figure 1. Frequency of published articles with performativity in their title.

Source: Authors’ own.

To gain a bird’s eye perspective and ensure that our interpretive analysis captures and illustrates the multiple facets of this complex literature, we carried out descriptive bibliometric analyses on a broader corpus: a dataset of 6,741 articles, book chapters, proceeding papers, and book reviews by querying Web of Science for results with the term ‘performativity’ in any field (i.e., title, abstract, etc.). This more expansive computational text analysis allowed us to gain insight into the circulation of ‘performativity’ in the broader literature. For instance, including review articles that discuss the performativity approach in the context of a subfield helped reveal how performativity moved across and influenced relatively distant intellectual communities.

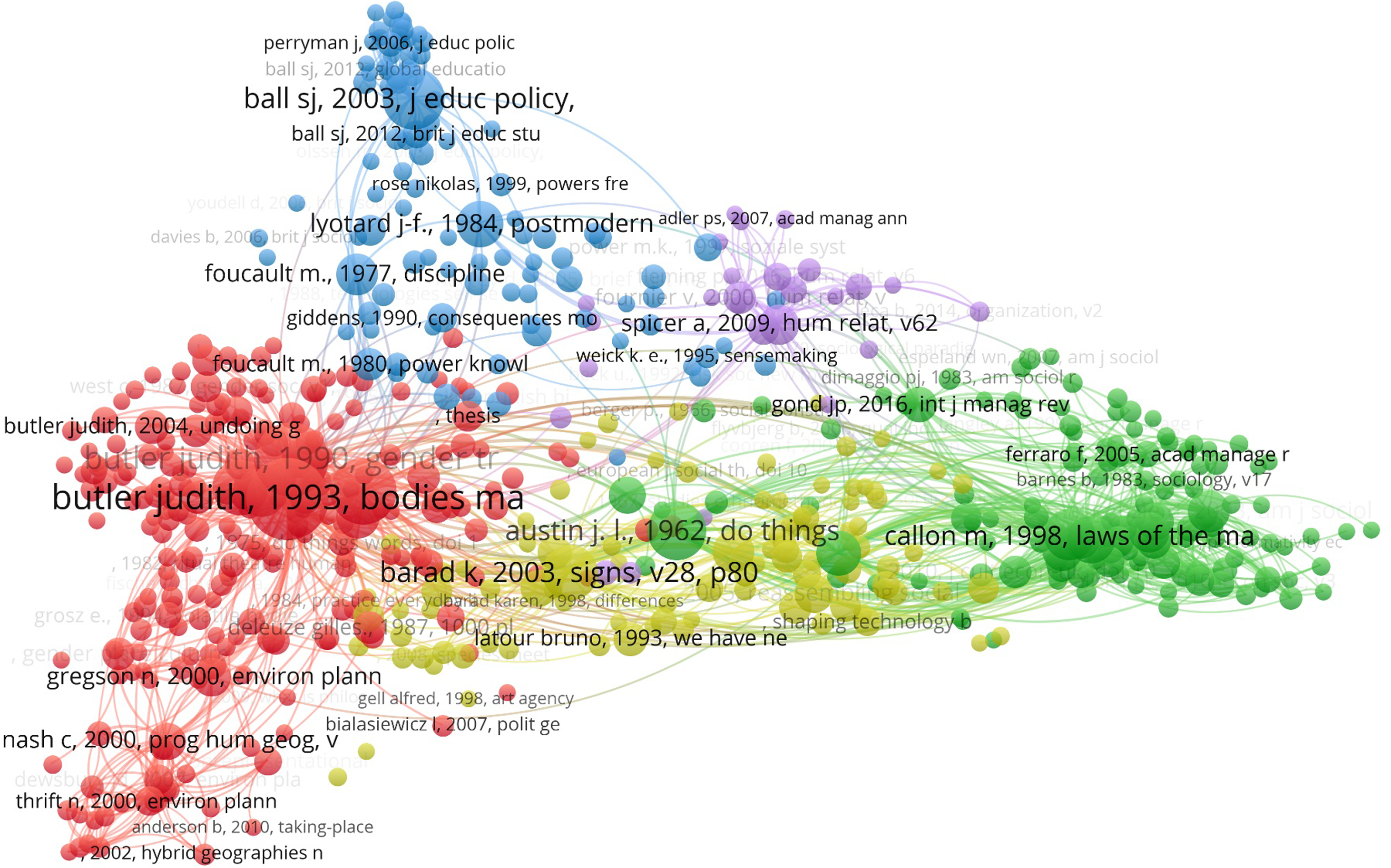

Figure 2 provides a visualization of co-citation analysis drawn from the Web of Science corpus focusing on performativity literature. A bibliometric network of citations would be unreadable without setting thresholds. Here we included papers that were co-cited at least 20 times, yielding 585 cited references. The design elements in the visualization highlight three key metrics: first, the prominence of a researcher based on citation count is represented by the size of a node. A larger node size corresponds directly to a higher number of citations a publication has amassed. Second, the degree of interrelation between two citations is evident in the distance between nodes: a shorter distance indicates more frequent co-citations. Thus, when two authors are frequently cited together, their positions in the visualization are closer, compared to authors who are cited together less often. Third, we utilize Gephi’s Louvain algorithm, a community discovery and analysis method that assigns a modularity score to each node and then groups nodes into distinct constellations, color-coded for easier understanding. This algorithm aims to maximize the density of connections within communities relative to connections between them (Maivizhi et al., Reference Maivizhi, Sendhilkumar and Mahalakshmi2016).

Figure 2. Bibliometric analysis of co-citations.

Source: Authors’ own.

Confirming our expectation, at the core of the figure lies Austin’s How to Do Things with Words (Reference Austin1962). Encircling it are five distinct research clusters. To the immediate right, colored in green, is Callon’s The Laws of the Markets (1998). This is intricately intertwined with a focus on economic sociology. Notably, our clustering algorithm places Austin’s book within this bibliographic cluster: while it is cited in numerous clusters, it finds its most frequent mentions in the realm of economic sociology. To the left, rendered in red, stands Judith Butler’s Bodies that Matter (Reference Butler1993), which is co-cited with a rich mix of works from political philosophy and feminist theory. Above Butler’s work is a prominent cluster in blue, zeroing in on education research. Directly to its right, a smaller purple cluster houses research focused on management studies, not too distant from economic sociology. It is interesting to note that a discipline whose relevance is tested very frequently by market forces seems to pick up performativity with success. Anchoring the lower section of the visualization, a research cluster in yellow, surrounds Barad’s influential article on ‘post-humanist performativity’ (Reference Barad2003) and Latour’s (Reference Latour and Porter1993) contributions to the literature from the vantage point of Social Studies of Science and Technology, again a very influential thread of research with strong links to economic sociology.

Unsurprisingly, Butler and Callon emerged as the two largest centers, followed by Barad and Ball, all of whom were connected by Austin. Interestingly, Butler and Callon, despite their work’s centrality to performativity, have tended to influence two relatively distinct groups of scholars – one focusing on (gendered) identity and the other on economic relations, despite both scholars’ relevance to economic inequality and agency.

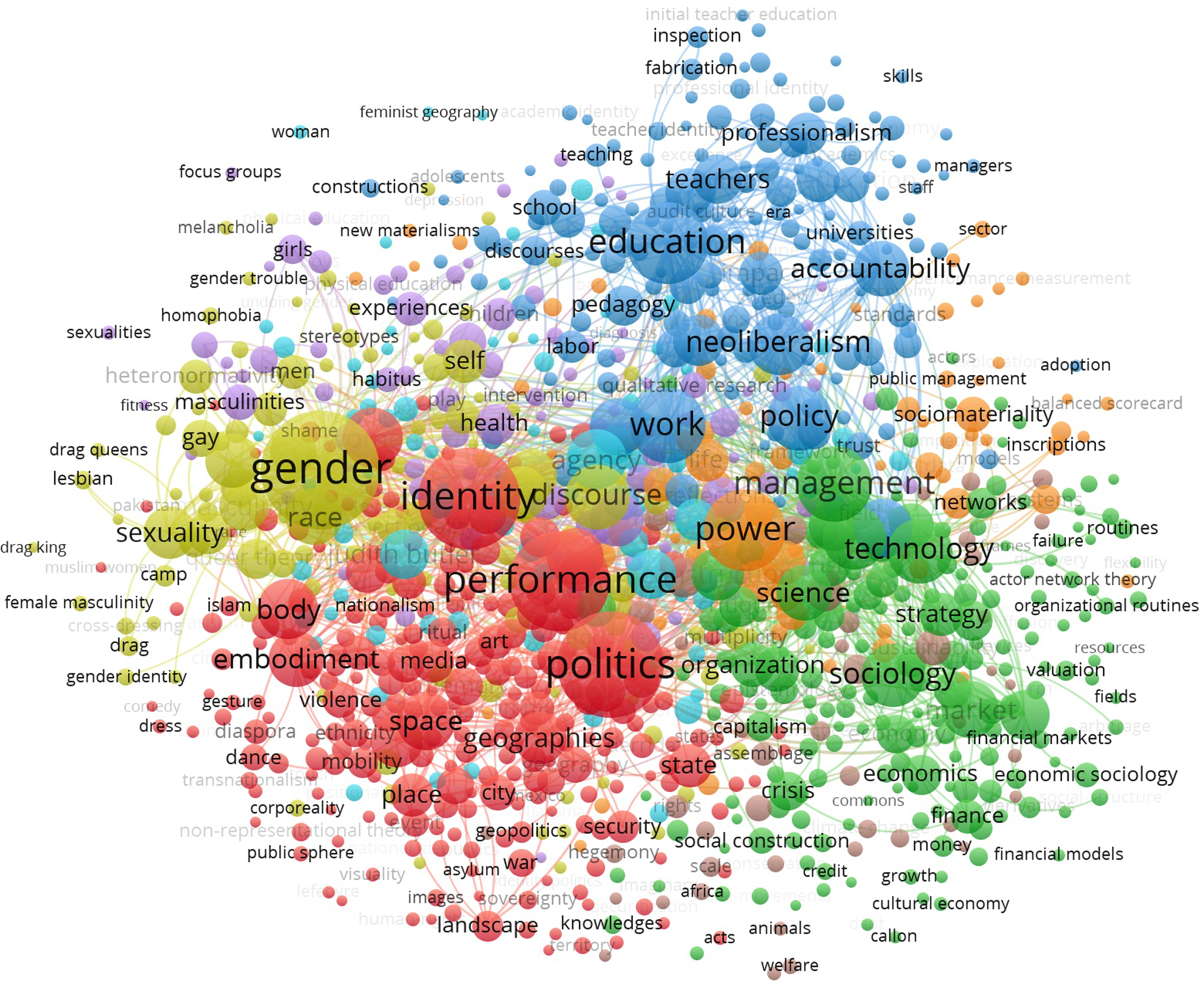

Figure 3 displays the results of a keyword co-occurrence analysis derived from the same corpus. In conjunction with the citation analysis, this figure elucidates key features of the five distinctive research communities mentioned earlier by spotlighting recurring keywords within citation clusters. These representative keywords provide insights into the central themes and inquiries driving each community.

Figure 3. Bibliometric analysis of keyword co-occurrence.

Source: Authors’ own.

The analysis shows that, (1) the cluster around the discipline of geography is characterized by keywords such as geographies, space, place, violence, and media. (2) Keywords like markets, innovation, economy, and financialization dominate studies of performativity in economic sociology and anthropology. (3) Research in education is represented by keywords such as education, pedagogy, accountability, and neoliberalism. (4) Work grounded in Butler’s theory and intersectional explorations of race, gender, and sexuality are signposted by terms like gender, sexuality, race, whiteness, and body. (5) The research community concentrating on management studies resonates with keywords such as organization, hegemony, and welfare.

This diversity of interests and research foci is both exciting and challenging, underscoring the necessity of developing a meta-theoretical framework. For instance, geography-related studies emphasize spatial concepts, while economic sociology and anthropology focus on market dynamics and innovation. Additionally, the dominance of certain keywords within specific clusters highlights the thematic concerns of those fields. For example, in education, keywords like pedagogy and neoliberalism indicate a focus on the impact of economic ideologies on educational practices. Similarly, in research related to Butler’s theories, the emphasis on gender, race, and sexuality underscores the importance of identity and intersectionality in these studies. This keyword distribution also suggests potential intersections between disciplines. For instance, terms like ‘space’ and ‘place’ in geography might connect with ‘organization’ and ‘hegemony’ in management studies, indicating areas where spatial analysis could inform organizational theory, or where economic concepts of innovation and markets could intersect with educational accountability and neoliberalism. These connections point to opportunities for cross-disciplinary dialogue and research.

Figure 3 also highlights untapped research areas that could be further explored. Two promising avenues of possibilities stand out. First, integrating gender and economic analysis through an intersectional framework could look into how gender performativity intersects with race, class, sexuality, and other social identities in shaping economic experiences and outcomes. For instance, research might examine further how racial performativity influences access to economic opportunities or how financialization disproportionately affects different groups. Second, gender performativity could be elevated to a central focus in socio-technical analysis of economizations. This could involve investigating how varieties of performativity of gender roles influence perceived economic performance, innovation capacity, and new finance. For example, studies might explore how gender performativity shapes innovation and access to financial resources in new financial communities.

Overall, our findings make visible two central insights: firstly, the performativity paradigm transcends disciplinary confines, fostering diverse research communities that incorporate performativity within their research trajectories. We clearly see the emergence of a new field of study in late modern societies. Performativity researchers have been demonstrating how we do and make things with representations in a variety of contexts in gender relations, economies, arts, politics, financial engineering, organizational design, and auction planning. Secondly, even though employment of the notion of performativity spans many diverse theoretical and empirical domains, a concern with performativity as performation – with how representational interventions perform actors, networks, devices, and representations – can be inferred across the vibrant interdisciplinary interactions revealed by the co-citation patterns. Accordingly, our meta-theoretical approach centers the performation process to help us see how performativity works through representational interventions such that gender, politics, security, and other central themes in the literature are performed. Modes of performativity give us the comparative framework to flesh out commonalities, and also identify variation in the performation process as a way of analyzing how these modes are deployed.

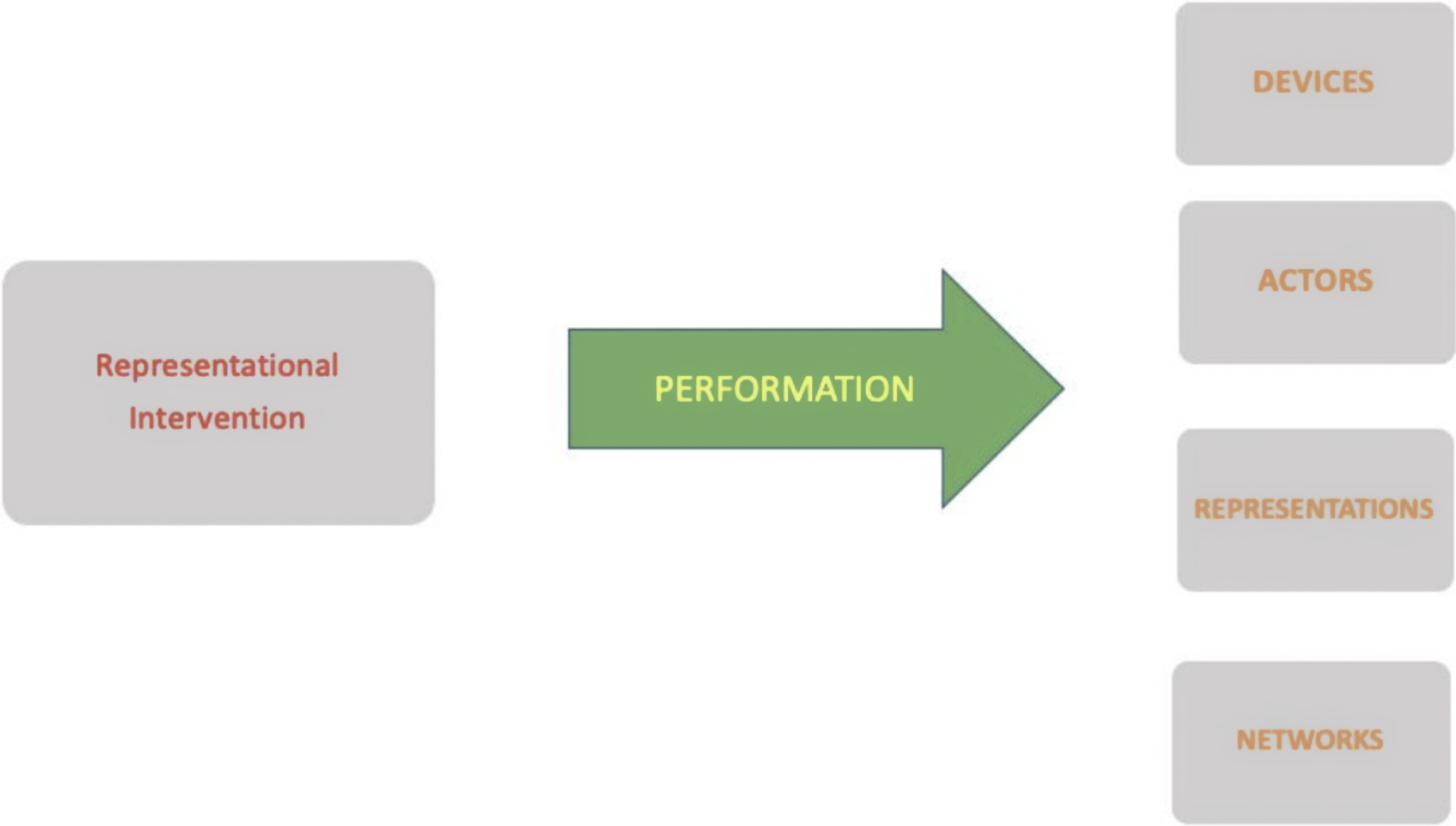

‘Mode’ refers to the trajectory or direction of a performation process in which a variety of representational interventions (such as a discursive proposition, an embodied engagement, a speech act, or a scientific or popular model) compete to influence the constituents of a distributed action universe, or in Callon’s terms, an agencement. As illustrated in Figure 4, the performation process encapsulates the intricate dynamics by which a representation succeeds in producing material, observable effects on such constituents of an agencement. Performation, as discussed by Callon (Reference Callon2006), extends beyond the mere articulation of representations to encompass their capacity to enact change by reconfiguring socio-technical agencements. This transformative process hinges on more than voluntarist declarations or symbolic gestures; successful performativity necessitates that the representational intervention aligns with its socio-technical context and engenders tangible impacts on its constituent elements (Caliskan, Reference Caliskan2022; Caliskan and Callon, Reference Caliskan and Callon2010).

Figure 4. Four modes of performativity.

Source: Authors’ own.

More precisely, a critical component of performation lies in the fulfillment of ‘felicity conditions’ that refer to contextual prerequisites such as the credibility and authority of the representation, the legitimacy of its proponents, and the receptiveness of the agencement’s constituents (Callon, Reference Callon2006). When these conditions converge, representations can transcend their descriptive function, reshaping the distributed action universe in ways that materialize their intended effects on its constituents: devices, actors, representations, and networks.

Within this framework, we define the four modes of performativity as follows: the Device Mode, where material devices are altered or created; the Actor Mode, which focuses on the shaping of human or collective agency; the Representation Mode, emphasizing creations of and changes within representational orders; and the Network Mode, addressing the configuration and reconfiguration of relational structures. Together, these modes provide a robust analytical toolkit to disentangle the multifaceted processes through which performative effects manifest and proliferate across socio-technical action universes.

Device mode

The Device Mode of Performativity refers to the change or making from scratch of a tangible or intangible material device due to a representational intervention. Once made or altered, this device is integrated into a socio-technical context, where it may be used by various actors. The essence of this mode lies in understanding how the deliberate alterations made to a device via a representational intervention influence and reshape the behavior and interactions of those who engage with it in a socio-technical setting. This process has been delineated by Callon (Reference Callon2016: 30–31) with reference to a specific kind of economic device, prices: ‘fixing the price of a good in [a market] transaction … stems from particular activities that I have proposed to call price formulation. … price formulation connects the particular conditions of the (bilateral) transaction to more general (e)valuations.’ When performativity scholars write about the performation of devices, they focus on how representations that combine various elements, from resources and artifacts, to machines, technologies, and calculative tools, enable the device to be used and thus change the relations among the actors who use it in their everyday life. The introduction of specific tangible (e.g., a shopping cart) or intangible (e.g., a stock index) devices, which are made via the device mode of performativity, plays a pivotal role in shaping actions and interactions within institutional settings, such as markets. By zeroing in on the representational interventions that perform devices, we are therefore able to open what would otherwise be an opaque box.

Calculations and measurements are a central theme, and while researchers vary in their emphasis on the practical uses of devices, economic sociologists and market scholars offer some of the most insightful analyses of the performation of devices. In some studies, this performation is seen as effective when it helps turn abstract ideas into concrete, thing-like entities through quantification and measurement. On the other hand, other researchers show that while these practical uses are crucial, they should be viewed within a bigger picture that includes moral, regulatory, and cultural factors. The usefulness of a tool’s measurements and definitions is tied to how well they fit within this wider economization context (Beunza and Ferraro, Reference Beunza and Ferraro2019).

McFall and Ossandón (Reference McFall, Ossandón, Adler, du Gay, Morgan and Reed2014: 256) describe this mode of performativity eloquently: ‘devices are performed by representations that frame them as helpful instruments: instruments that make valuation possible by “pricing, prizing, and praising”’. Cochoy (Reference Cochoy2008), in his discussion of shopping carts as market devices, describes them as one of the many forms that calculative spaces can take, where consumers can engage in various tasks. These tasks may include maneuvering large quantities of goods, performing intricate calculations, revising conflicting price and extra-economic interests, and making consumption decisions collectively. Price acts as a variable that qualifies the goods and contributes to their profiling. These interrelated framing processes continuously produce and perform a single space of calculation.

Caliskan (Reference Caliskan2007) presents another example of device mode of performativity in his ethnographic study of global cotton markets: a variety of prices as devices are made via representational interventions. Calling these market devices prosthetic prices, he analyzes how pricing tools are designed, deployed, and used by merchants and experts who work for them in global commodity markets (Caliskan, Reference Caliskan2007). A type of prosthetic price, the rehearsal price, is not binding, and it can be changed or withdrawn at any time. Transaction prices, by contrast, are the prices at which goods or services are actually bought and sold. They are different from rehearsal prices, which are used to test the market and gauge interest. Transaction prices are binding, and they cannot be changed or withdrawn after the transaction has been completed. Finally, market prices are the more general abstractions that circulate across global markets. They abstract from quality variations and local evaluations in order to sustain transactions across large distances. These various prices are produced in different forms in order to prevent or foster exchange in different sites. They function as prosthetic devices that organize speech acts, bodily performances, and even larger forces such as supply and demand. The device mode of performativity constitutes these prosthetic prices as devices, and thus makes the global commodity market possible on the ground. Without the performation of a device, he shows, there would not be a market.

For a complementary perspective that emphasizes the complex intersection of economic and political effects produced by performation of prices, Christopher (Reference Christophers2014) has shown how prices work in the global pharmaceutical industry and critiqued the idea that the tiered pricing model that allegedly self-regulates these markets is actually enforced by market actors from above. Prices are performed by instrumental representations that give them an appearance of objectivity and neutrality: these qualities then allow pricing models to serve as a public relations tool, giving substance to the claim that the industry cares about access to medicine. The models are invoked, talked up for their potential merits, and often experimented with, so that the industry can justify inaction, and prices are used to help create the appearance of ethical commitment. The economic and instrumental performation of models has political effects, in the sense that it helps stave off potential challenges to existing market arrangements by presenting the models as technically sophisticated as well as responsive to multiple stakeholders (Christopher, Reference Christophers2014: 1055–56).

Another important example that illustrates the performativity of representations of devices is offered by Alex Preda’s (Reference Preda2009) influential historical sociology of the stock ticker. In Preda’s book, the ticker is more than an observational instrument; it is a ‘generator,’ producing new ‘paths of action’ in the future. Serving as microscopic devices, stock ticking devices complement other market instruments and mercantile strategies in the coordination of economic activities.

The research of Espeland and Sauder (Reference Espeland and Sauder2007) enhances the device mode of performativity by emphasizing non-instrumental representations in device design. As experts in organizational studies who analyzed public reactivity using the lens of law school rankings, they illustrate how public measures elicit responses from key organizational figures, like law school administrators, in a manner reminiscent of self-fulfilling prophecies. Specifically, they illustrate how the technical details underpinning rankings influence the anticipations and actions of external audiences, survey creators engaged in generating subsequent ranking rounds, financial backers both within and external to universities, and the universities themselves. Yet, none of these stakeholders genuinely believe that the rankings authentically reflect, encapsulate, or gauge the actual quality disparities among institutions. Instead, these technical representations are interspersed with idealistic visions and enticing comparisons, which in turn result in an increase in ‘gaming strategies’ to obtain a preferable ranking position in a system whose flaws and even irrationalities are widely acknowledged.

Other notable studies examine how devices are performed through multiple representational interventions. For instance, representations may influence the manifestation of measurements tied to the moral and ethical perspectives of entities, acting as mediums for their aspirations. As an example, Roscoe (Reference Roscoe2013: 386–87) weighs in on organ markets. He unveils the distinct ways in which devices, like prices and numbers, evolve into ‘economic facts’ and garner a ‘moral force.’ This force subsequently strengthens the ‘moral axioms’ rooted in ‘instrumental, utility-maximizing rationality’ in organ markets. These representations are performative not merely because they act as measurement devices that appear independent of political and moral endeavors, but because measurement inherently possesses a moral dimension.

Other researchers examine packaging and representations on it as devices enabling products to be branded and perceived to possess a specific quality. This perception holds even for relatively homogeneous items, such as bottled water (Hawkins, Reference Hawkins2013). Another noteworthy investigation analyzes a US-based premier financial data and technology provider that designed a calculative tool to foster the investment practice known as environmental, social, and governance (ESG) integration (Beunza and Ferraro, Reference Beunza and Ferraro2019). This tool became performative after the firm harmonized it with other organizational sectors, engaged consumers with it, and connected it through NGOs and regulatory bodies to a more expansive responsible investment domain.

Data devices, along with interconnected data-driven information systems, also shape various aspects of our daily lives (Blouin, Reference Blouin2020; Gustavsson and Ljungberg, Reference Gustavsson and Ljungberg2021). More specifically, focusing on performative effects of multiple data initiatives on meaning-making processes, Blouin (Reference Blouin2020) argues that European Core Health Indicators produced by the European Commission contribute to the re-definition of health when they are used as representative tools in everyday life (Blouin, Reference Blouin2020).

In sum, our theoretical focus on performation processes foregrounds the multiple representational interventions that perform devices at different points in time and in different locales. Performation is distributed across a broader network or arrangement, and it alters the devices’ capacity to influence the network in which they are embedded. Once a representational intervention changes how a device is performed, its effects can cascade onto other elements of the network. Understanding how a representation is performative of a device helps us grasp this process more clearly.

Actor mode

In referring to the Actor Mode of Performativity we deliberately employ the term ‘actor’ more narrowly than it is used in ANT: we refer specifically to individual or collective human agency. The Actor Mode of Performativity refers to the processes by which human agency – and varieties of its articulation, such as gender, sex, race, ethnicity, caste, religion, and even the physical body – are shaped, sustained, and evolved, leading to a distinctive performation effect that can change or redefine individual or collective human agency. One of the most renowned examples is Butler’s exploration of gender performativity. Particularly highlighted in Gender Trouble (1990), Bodies That Matter (Reference Butler1993), and Excitable Speech (Reference Butler1997), the actor mode ignited new interest among scholars across various disciplines. That has been crucial in expanding the performativity literature from its origins in linguistic philosophy to diverse fields such as gender studies, political theory, economic sociology, anthropology, education, and media, among others.

Amid the burgeoning interest in performativity, scholars examining identity through a poststructuralist prism showed that human identity (whether based on gender, national origin, ethnicity, race, etc.) is not an innate fact or a fixed entity. Instead, subjectivity emerges from the interplay between socio-cultural norms and linguistic practices that involve performative acts. The recurrent reiteration of judgments and norms, laden with their inherent significance, paves the way for such processes of subject formation. Building on this perspective, several scholars from diverse disciplines have shifted their attention to the performative crafting of normative identities (Salih, Reference Salih, Jenkins and Lovaas2007; Ringrose and Renold, Reference Ringrose and Renold2010).

Subject formation cannot be reduced to isolated discursive acts detached from their socio-historical contexts. Nor can it be viewed as a direct cause-and-effect sequence driven by singular actors possessing inherent, cohesive identities (Abe, Reference Abe2020). Moving beyond limited interpretations of performativity that restrict human subjectivity solely to linguistic frameworks, some scholars highlight the term’s relevance in discussions surrounding materiality, corporeality, and embodiment (Andersen, Reference Andersen2016; Abe, Reference Abe2020; Reference Tanupriya and Pannikot2021). Central to this perspective is the idea that the tangible body acts as a conduit in the processes via which subjectivities are crafted, sustained, and evolved (Butler, Reference Butler1993).

The importance of discussions of materiality and embodiment in relation to performativity becomes clear when examining the ongoing discourse distinguishing performance from performativity. These terms, while closely related, stem from distinct, albeit intersecting, theoretical traditions: the former is rooted in Victor Turner’s studies on ritual social drama and Erving Goffman’s dramaturgical perspective, whereas the latter is anchored in Butler’s approach. According to Goffman and Turner, performances require social acknowledgment and repetition (Abshavi and Ghanbarpour, Reference Abshavi and Ghanbarpour2019). This repetitiveness becomes a foundation for the emergence of established meanings deeply embedded in collective consciousness (Butler, Reference Butler1988). Thus, while Butler integrates and reshapes the theoretical insights of Turner and Goffman, differences between their perspectives persist (Ylivuori, Reference Ylivuori2022).

Consequently, there is a clear inclination among scholars in interdisciplinary performativity studies to differentiate between the concepts of performance and performativity (Bollen, Reference Bollen1997; Rak, Reference Rak2021). ‘Performance’ pertains to deliberate human activities within various situational contexts, whereas ‘performative’ encapsulates both intentional and unintentional actions anchored in ‘citational chains or a history of repetitive acts and entrenched practices’ (Sullivan, Reference Sullivan2012: 438). As a result, a performative practice influences how individuals act, aligning with the perceptions they aim to project in social exchanges. This suggests that performativity continually molds identities and standard subjectivities that are evident in daily life (Salih, Reference Salih2015). To be sure, instead of clearly demarcating performance from performativity, certain interdisciplinary scholars champion merging these concepts to foster a deeper understanding of subjects who manifest embodied actions over time and space (Smitheram, Reference Smitheram2011). This is perhaps most evident in the works of education scholars who rely on the actor mode of performativity. Within this body of work, scholars explore the potential for shifts and disruptions in the structures that mold individual participants such as teachers and students. Notably, these scholars highlight the agency of both teachers and students in effecting change, especially through pedagogical approaches. They also emphasize that these performances are contextually anchored: deeply rooted in specific institutional settings (Thompson, Reference Thompson2010; Vick and Martinez, Reference Vick and Martinez2011).

Scholars examining actor modes of performativity show that the performative creation of subjectivity can be seen as foundational for any kind of agency, as it fosters the emergence of subjects capable of action (Bacchus, Reference Bacchus2013). Additionally, human agency becomes evident in instances where the body does not consistently align with dominant gender norms and conventions of hegemonic heterosexuality (Knadler, Reference Knadler2003). The body can imagine and perform in ever-shifting patterns of cultural transformation, which in turn leads to alternative realities emerging from subversive gender performances (Reference Arrizón2002).

Scholars of gender and sexuality examine these subversive performances, which are marked by non-binary gender practices (Mills, Reference Mills2003; Weiss, Reference Weiss2005; Schippert, Reference Schippert2006; Mejeur, Reference Mejeur, Parker and Aldred2018; Milani, Reference Milani, Hall and Barrett2019; Wilson, Reference Wilson2018; Sanchez Espinosa and Sandoval, Reference Sanchez Espinosa and Sandoval2020; Pain, Reference Pain2020, 2020; Ramadhani and Mustofa, Reference Ramadhani and Mustofa2021). Specifically, these studies highlight how dominant concepts of hegemonic heteronormativity and sexual binaries are both contested and transformed (2020). Within this context, the term ‘queer’ signifies a departure from conventional norms rather than denoting a specific sexuality or gender (Mejeur, Reference Mejeur, Parker and Aldred2018).

Scholars of performativity also show how the processes of human actor formation are often influenced by normative judgments that wield regulatory and authoritative control over behaviors. Some interpret performativity as ‘a technology, a culture, and a mode of regulation that uses judgments, comparisons, and displays as tools of incentive, control, attrition, and change, leveraging both tangible and symbolic rewards and sanctions’ (Rich and Evans, Reference Rich and Evans2009: 2). Issues of accountability often materialize in standard performance evaluation criteria. Nevertheless, it is crucial to recognize that there always exist counterforces resisting dominant ‘performativity regimes’ that reflect overarching power/knowledge structures (White, Reference White2010). This resistance paves the way for the emergence of new forms of agency that challenge the status quo of disciplined and compliant individuals.

Moving beyond the Foucauldian vantage point, some scholars of performativity, adopting the material-semiotic perspective, especially from the ANT angle, emphasize the significance of diverse network relations in influencing the processes of actor formation. These interconnected relationships foster a myriad of associations, all of which collectively play a role in the creation of various actors (Law, Reference Law1992; Latour, Reference Latour and Porter1993; Lagesen, Reference Lagesen2012; Bryant, Reference Bryant2019; Glouftsios and Scheel, Reference Glouftsios and Scheel2021). More specifically, Bryant (Reference Bryant2019) illustrates how heterogeneous networks involving technology, media, objects, images, texts, norms, and experiences bring into being the performative manifestation of queer identity. In a similar vein, Lagesen (Reference Lagesen2012: 444) suggests that (gendered) subject formation is an ongoing movement ‘where associations with bodies, norms, knowledge, interpretations, identities, technologies, and so on are made and unmade in complex ways’.

Looking through the above lens, it can be argued that human agency and identity emerge as practical accomplishments of the performative work of socio-technical arrangements also in racialized contexts. The exploration of racial performativity equips scholars to better observe racial(ized) identities through a poststructuralist lens in contemporary social science (Scheie, Reference Scheie1998; Reference Arrizón2002; Knadler, Reference Knadler2003; Thompson, Reference Thompson2003; Muñoz, Reference Muñoz2006; Hübinette and Räterlinck, Reference Hübinette and Räterlinck2014; Gholson and Martin, Reference Gholson and Martin2019; Shilo, Reference Shilo2020; Melo, Reference Melo2021). Racial identity is now seen as a dynamically constituted construct that is consistently reformed, carrying with it the potential for transformation and reinterpretation (Thompson, Reference Thompson2003). The continuous human endeavor to challenge societal constructs renders racial identity profoundly performative. This persistent political resistance paradoxically compels scholars to probe the inherent inconsistencies within (racialized) human subjectivity. Moreover, rather than simply stating that racial identity is enacted, some researchers emphasize the intrinsic performativity of notions of race. Specifically focusing on ‘the actions resulting from race’, Muñoz (Reference Muñoz2006) posits that race has transformative outcomes, notably playing a pivotal role in the political acknowledgment of marginalized groups.

Studies of religion also demonstrate actor mode of performativity by describing the ways in which religion identity is performed, with a particular focus on the role of bodily engagement and material practices in shaping identity and subjectivity (e.g., Muslimness-Muslim identity) (Yaqin, Reference Yaqin2007; McLoughin, Reference McLoughin2017; Huygens, Reference Huygens2021). In this sense, religious identity is not just the expression of preexisting beliefs, but the performative creation of these beliefs, especially through symbolic rituals, material practices, and the construction and reproduction of everyday lived spaces of pious agencies.

However, it is also important to recognize the limiting or constraining facets of performativity, especially since performativity can impose regulatory and restrictive impacts on agency, particularly concerning technologies of control. In this context, Glouftsios and Scheel (Reference Glouftsios and Scheel2021) examine how information systems and digital technologies performatively govern and limit the agency of migrants and border-crossers, challenging control practices. Kasnitz (Reference Kasnitz2020) provides an ethnographic insight into how disability and the disabled are performatively constructed and reiterated as impaired human actors through specific interventions.

Representation mode

The Representation Mode of Performativity allows for the creation of a tangible impact on a representation through an intervention that is itself representational. This may seem like a complex and circular argument, yet it draws on a clear-cut process of performation. To give an example, performativity studies can themselves be shown to contribute to the making of the subdiscipline of social studies of finance, itself a series of scientific representations (Samman, Coombs, and Cameron, Reference Samman, Coombs and Cameron2015). According to Lomnitz (Reference Lomnitz2022), when a representation is verbalized, the speaker is acting, rather than merely describing the world around her. Such utterances ‘perform’ the actions they signify (Mäki, Reference Mäki, Karakostas and Dieks2013; Rak, Reference Rak2021). Examples of these performative utterances as posited by Austin include expressions like ‘I promise’, ‘I name’, ‘I do’, and ‘I bet’ (Bollen, Reference Bollen1997: 109). If I say, ‘I apologize’, I am not describing some external state of affairs but making an apology.

Callon (Reference Callon1998) and Mitchell (Reference Mitchell1998) show that the discipline of economics played a pivotal role in bringing into being ‘the economy’ as a tangible representation during the latter half of the 20th century. These scholars hailed from distinct research traditions. Mitchell (Reference Mitchell1998) was a pioneer in post-colonial studies of the Middle East, melding history and political theory, drawing heavily on Foucault and Derrida. One of the most frequently cited examples of the Representation Mode of Performativity is Callon’s (Reference Callon1998: 30) thesis that ‘the economy is embedded not in society but in economics’. Economics as a set of representations that describe economies, giving rise to a cascade of new representations, whose combined effects create a material experience of the economy. The emergence of the GNP is the condition of possibility for the performation of the economy. In the same vein, monetary aggregate M1 not only represents money supply, but also informs the description of the circulation of goods. Both GNP and M1 as representations that are partly made and performed by a series of preceding representations. Similarly, Reference Mason, Kjellberg and HagbergMason, Kjellberg, and Hagberg’s ground-breaking edited book made visible how a variety of performations take place in the processes of marketing practice (Mason, Kjellberg, and Hagberg, Reference Mason, Kjellberg and Hagberg2018). Finally, the role of market theories in making markets was tested by Shapiro. He showed that the neoclassical market model was used by platform companies to induce economic performativity ‘to extract greater value from customers or labor’ in platform contexts (2020: 163).

We must remember that representations are not mere symbols that make visible otherwise more real and latent ideas or things; rather, they themselves are material things that contribute to the making of realities on the ground. Dourish’sReference Dourish(2017) analysis of data as material representation or the famous demonstration of the material difference between Roman numerals and Arabic numerals are authoritative examples. Roman and Arabic numerals represent 9 or IX in materially different ways, with materially different consequences. Accounting and algebra are infinitely more difficult to carry out with Roman numerals; hence, Arabic Algebra is partly possible as result of the material difference of Arabic numerals.

Numerous empirical examples of the Representation Mode of Performativity often do not explicitly mention performativity, but are nevertheless performativity analyses. For example, Mitchell’s (Reference Mitchell1998) empirical examination of the emergence of ‘the economy’ has shown that it was assembled after the Second World War, drawing from a sequence of representational interventions that described a quantifiable entity, subsequently leading to an objectified representation. He has demonstrated ‘how the modern understanding of ‘the economy’ as the totality of the relations of production, distribution and consumption of goods and services within a given country or region arose in a mid-twentieth-century crisis of economic representation. The economy, represented as an autonomous domain … a concept of development without political upheaval’ (Mitchell, Reference Mitchell1998: 80).

Bringing together Marxian political theory and also drawing on Mitchell’s work, Gibson-Graham (Reference Gibson-Graham2008) has proposed a new iteration of the representational mode of performativity, calling for imagining new representations that might give birth to describing economies and making them ‘better’ at the same time. Referring to these material works as ‘performative practices’ (production of any kind of representation is impossible without a material practice), Gibson-Graham (Reference Gibson-Graham2008) has presented a series of representational interventions as well as their production and design process with the aim of managing a successful performativity of representations that aims to address relations of injustice.

Roitman’s work on the emergence and assembly of ‘crisis’ has shown that the deployment of the term to represent economic collapse have contributed to new representations of how to address it with specific corporate interests in mind. Crisis as a representation would then contribute to the performativity of ‘the economy’ as a representational subject, even at times when economies were shown to be not working (Roitman, Reference Roitman2013). The argument was interesting; the idea of ‘the crisis’ helped capitalists’ problems to be resolved in the way in which they wanted them to be resolved. The Representation Mode of Performativity was thus a central dynamic at work during times of crisis. Several years after the publication of Roitman’s Anti-Crisis, Kim has demonstrated that many statistical representations were produced and deployed in manufacturing a crisis representation during Greece’s debt default in 2015, providing the literature with another telling empirical example of the Representation Mode of Performativity at work (Kim, Reference Kim2023).

Central Banks appear to leverage the Representation Mode of Performativity frequently, especially in relation to representations of crises. Polillo (Reference Polillo2020) illustrates how the Italian Central Bank employed what he terms Fictional Performativity to construct a strategically assembled, partially fabricated history. This approach framed crises as exceptions to a desirable state of affairs, which the authority vowed to restore or preserve. By reimagining the past, the Bank effectively propagated visions of a ‘brighter’ future. Similarly, Morris (Reference Morris2016) explored the Bank of England’s press conferences, coinciding with their Financial Stability Reports and stress test results, as arenas for creating and disseminating new economic representations. These interventions – encompassing both textual and embodied performances – mobilized diverse modes of performativity, including ‘Austinian’, ‘generic’, and ‘layered’ performativity. Collectively, these performative strategies reshaped the representation of the economy and the Bank of England’s pivotal role within it.

In a related vein, legal performativity explores how judicial statements enact and transform realities, often mirroring the performative dynamics seen in economic governance. Many classical examples of Austinian performativity, such as an authority declaring a couple married or someone an outlaw, are inherently legal. Beyond these formal acts, legal scholars analyze how laws and regulations not only reflect but actively construct political and normative representations. This lens reveals underlying ideological biases and political agendas embedded in legal frameworks (Kebranian, Reference Kebranian2020). For instance, Vartazaryan (Reference Vartazaryan2022) examines how recognizing the Armenian Genocide by nations such as France, Germany, and the Czech Republic influences political narratives. Applying the concept of performativity to these ‘memory laws’ necessitates an analysis of the felicity conditions under which judicial or legal declarations succeed in shaping collective memory and social realities (Vartazaryan, Reference Vartazaryan2022: 196).

Lastly, a specific Representation Mode pinpointed by researchers holds a meaningful relevance for this article’s review of literature by emphasizing the central goal of this paper: to heighten broader awareness about performativity and its associated research. Gond et al. (Reference Gond, Mena and Mosonyi2023) demonstrated that literature reviews, as representations, possess the performative capability to transform, establish, and reconfigure scientific literatures. Through a captivating empirical investigation into 48 literature reviews on corporate social responsibility from 1975 to 2019, Gond et al (Reference Gond, Mena and Mosonyi2023: 195) identified the act of ‘literature reviewing’ – akin to our approach in this paper – as a performative action. It simultaneously defines and shapes the literature it aims to describe, engaging in a ‘dual movement of re-presenting – constructing an account different from the literature, and intervening – adding to and potentially shaping this literature’. If this is the case, scientists should be more aware of how their own reviews shape the literature of which their writing constitutes part.

Network mode

The last mode of performativity observed in the literature involves a successful intervention in the creation and revision of a network of relations. The notion that performativity is the felicitous outcome of a representation that alters the arrangement of a network is perhaps one of the most significant contributions of the performativity literature in economic sociology. Here, the outcome of interest, typically the formation of a new market or economic platform, is reframed as an instance of network formation. Other bodies of research in science studies, particularly in architecture and planning, as well as in the study of political and organizational governance similarly use the term ‘network’ to broaden their substantive focus, challenging the boundaries set by more conventional, naturalized, and constraining approaches.

The Network Mode of Performativity is at the center of MacKenzie and Millo’s (2003) historical sociology of a financial derivatives exchange, a paper that details the formation of this new financial market by the Chicago Board of Trade through the introduction of a new theory of options pricing, represented by the famous Black-Scholes formula. MacKenzie and Millo (Reference MacKenzie and Millo2003) have reconstructed the collective mobilization of financial innovators to set up a new trading floor. This was followed by the implementation of tools rooted in options-pricing theory to guide trading, and, crucially from the viewpoint of network-making, to make it easier to think about, talk about, and negotiate option prices. There was an initial discrepancy between the model’s forecasts and actual patterns of market prices. Remarkably, the model strategically dismantled what could have been a fatal resistance to options trading from regulators, who had previously dismissed such practices as vehicles for market manipulation or mere gambling. As time progressed, the model’s predictions aligned more closely with reality, providing a vivid substantiation of how the network mode of performativity works. The deployment of the Black-Scholes option pricing model transcended the realm of theoretical formalization; it materialized as an active representational force, assembling a network of actors, devices, and practices that reconstituted the very fabric of financial trading. Through its performative enactment, the model not only stabilized trading practices but also redefined the contours of legitimacy within financial markets, leaving an indelible mark on the architecture of contemporary finance. However, unforeseen financial volatility and crises (caused in part by other uses of the Black-Scholes) later created deviations, which can be interpreted as manifestations of ‘counter-performativity’ (see below).

Expanding on the performativity concept beyond the economic sphere, Healy (Reference Healy2015) analyzes the transformative role of social media and the solidification of formal network analytic methodologies and theories within sociology as an illustrative case of performativity. He argues that network analysis, with its robust theoretical foundation complemented by a suite of methods, and its adaptability to broader exchange structures, not only described but also influenced the very networks under scrutiny. This manifested in fostering connections within triads (evidenced by Facebook’s ‘people you may know’ suggestions), amplifying similarity-based connections in individual social networks, and paving the way for the propagation of other core network characteristics intrinsic to the theoretical framework.

Additional, important work that investigates this mode of performativity sits more squarely at the intersection between science and political economy. As a particularly useful example, Helgesson and Lee (Reference Helgesson and Lee2017) have discussed how valuation practices and economic assumptions become entwined with other knowledge-making practices, including pharmaceutical trials, to produce pharmaceutical candidates suitable for further research and development. Focusing on the European Medicines Agency and the Food and Drugs Administration, they show how networks of scientific researchers, market specialists, and regulators are brought together and reconfigured by specific interventions, such as the ‘compound finder trial design’ – a specialized approach to randomized controlled trials that allows for adaptive modifications to the trial even after its start. In this way, valuations that emerge from early phases of the trial can be included in later assessments of the drug’s usefulness in the health care system; by the same token, economic assessments of a drug’s marketability can be fed back into scientific assessments of the desirability of one kind of trial over others.

Though economic sociology and science studies remain the primary domains for this approach, two other significant areas also employ the Network Mode of Performativity as a foundational research strategy to explore how representational interventions mold networks: the performative design methodology in architecture and the performativity perspective in governance. The former examines human interactions with structures and how to create buildings that are not just environmentally harmonious but also foster beneficial interactions and networks. Notable references in this context include work by Grubbauer and Dimitrova (Reference Grubbauer and Dimitrova2022).

This approach melds the concepts of ‘sustainability’ and ‘resilience.’ It highlights how, in performative design, the design of a building not only concerns physical aspects such as structure, materials, temperature, and sound, but also impacts (sometimes deliberately) other factors such as human interaction, network formation and behavior. In this realm of architecture, the design process focuses on establishing or evolving the networks of relationships among human inhabitants or users, and between them and the physical space (i.e. the ‘design’ as traditionally conceived). Thus, function, form, network interactions, and subjectivity are intricately interconnected through a performance-oriented design mindset.

In terms of governance, an insightful illustration of what we call the Network Mode can be found in Burnier’s (Reference Burnier2018) exploration. She seeks to separate performance metrics from the neoliberal approaches of managerial oversight and repurpose them for projects that are accountable to democratic principles through the lens of ‘critical performativity’. She shows that performance indicators, derived from transparent deliberation and reflecting the unique organizational culture they engage with, can pave the way for establishing new networks. These networks emphasize democratic ideals, engaged citizenry, and effective organizational initiatives. Particularly captivating is Burnier’s (Reference Burnier2018) argument on the confluence of performance (viewed through a theatrical lens) and governance. She points out how limiting interpretations of performance as mere quantifiable outcomes can be re-evaluated by acknowledging the transformative impacts of expressive actions and ceremonies. An instance of this is the validation of public investments in the arts based on active citizen participation.

Integrating the modes: Toward a meta-theoretical framework for performativity

Employing the DARN framework, this paper introduces a meta-theoretical perspective to interrogate the multifaceted processes through which performativity unfolds. By articulating four interrelated modes, Device, Actor, Representation, and Network, the framework offers a heuristic for scholars to contextualize and critically analyze performativity in its situated manifestations.

First, the Device Mode of Performativity focuses on changes to devices found in a given social context. For example, a change in how price as a market device is used has a performative effect on the making of global prices as devices that are then used by traders to pursue their commercial interests (Caliskan, Reference Caliskan2007; Reference Caliskan2023). Second, the Actor Mode of Performativity, by contrast, foregrounds the emergence of agency as an outcome of performative processes. This mode highlights how representational interventions partially or wholly engender agency, exemplified by Butler’s (Reference Butler1988; Reference Butler1990; Reference Butler1993; Reference Butler1997; Reference Butler2004) hugely influential analyses of gender performativity. Third, the Representation Mode of Performativity interrogates the material effects wrought on representational systems through specific representational acts. Both Michel Callon (Reference Callon1998) and Timothy Mitchell (Reference Mitchell1998) have shown that economics as a discipline contributes to the making of ‘the economy’ as a representational material object of research. Finally, the Network Mode of Performativity centers on interventions that create or reconfigure networks of relations. MacKenzie and Millo (Reference MacKenzie and Millo2003) and MacKenzie (Reference MacKenzie2006) show how the Black-Scholes model of option pricing contributed to the making of exchange networks via which options and other financial ‘derivatives’ were traded. Shared models served as conduits for communication among traders, enabling the articulation of shared understandings about derivatives and the negotiation of their prices.

Crucially, these four modes of performativity are neither ontologically distinct nor mutually exclusive. Instead, they operate relationally, often overlapping and cascading into one another, and in some cases, unfolding synchronously. Each actor is a network, networks can assume agency, and agency itself is distributed variably across the agencement. While these elements are deeply interwoven, distinguishing among them heuristically offers valuable analytical leverage, allowing scholars to identify specific modes of performativity and trace the shifting power dynamics between these agential components.

The fluidity of these modes becomes particularly evident when the analytical focus shifts. A single entity such as the police might be understood as an actor, a device, or a representation, depending on the vantage point of inquiry. When specific representations, whether they represent an agency (like gender), a device (such as price), a network (such as a specific trading relationship), or the concept of representation itself (as in a ‘crisis’), impact the operation and interaction of these Ds, As, Rs, and Ns, we can empirically observe performativity.

The modes of performativity must not be conflated with the totality of what constitutes DARNs. Rather, they play a variable and context-dependent role in shaping these elements. Nor can these modes be treated as autonomous explanations of social action. Their principal contribution lies in elucidating how representations engender material, observable effects. Analytically, they focus on a single strand within the complex weave of distributed social action, clarifying the role of performativity in the broader formation of DARNs by anchoring it in tangible socio-technical outcomes. By prioritizing the empirical validation of performative effects, this framework mitigates the dangers of over-abstraction, emphasizing specificity in the analysis of how representational interventions generate concrete and measurable outcomes. The empirical cases reviewed in this paper, ranging from the role of calculative devices in the performation of financial markets to the shaping of racial and gender identities, underscore the tangible effects of performative representations across diverse domains.

As underscored throughout this paper, we propose that only representations can be performative. While Devices, Actors, and Networks undoubtedly possess agency, agency itself cannot be equated with performativity (Caliskan and Wade, Reference Caliskan and Wade2022a, Reference Caliskan and Wade2022). For instance, when we refer to the Device Mode of Performativity, we are not suggesting that devices themselves are performative; instead, we are analyzing how a representation becomes performative of a device. Similarly, the Actor Mode of Performativity examines the processes that contribute to the making of agencies, such as gender. It does not focus on how gendered actors enact or perform social action because, fundamentally, actors are not performative. Performativity is intrinsically tied to the effects of representations, not to the actions of agents. Actors do and make things, and it is important to state this as plainly as possible. In this regard, the Actor Mode of Performativity with respect to gender provides a framework for analyzing the creation of gendered agencies, rather than exploring how gendered actors generate social effects.

Ultimately, the modes of performativity pertain to the processes through which devices, agencies, representations, and networks are brought into being. They do not purport to capture the broader effects of DARNs on social action. Instead, they illuminate the representational dynamics that underpin the making of these elements, offering a grounded and empirically validated lens for examining performative interventions in the socio-material world.

The discussion here highlights the theoretical and practical implications of the DARN framework, emphasizing its contributions to understanding distributed social action and its potential to advance performativity-oriented social research. One of the key contributions of this paper lies in its systematic articulation of the modes of performativity, which not only underscores the adaptability of the term performativity but also helps to address the complexity of the concept.

The diversity of the modes of performativity might suggest that the concept is fragmentary. By offering a structured approach to navigating the complexity of performativity, the framework addresses the apparent fragmentation within existing scholarship, particularly the disciplinary silos that have shaped its development. This synthesis reveals that such fragmentation reflects differences in disciplinary emphases or focus of analysis rather than fundamental theoretical divergence. For instance, while Butler’s work in gender studies significantly illustrates the Actor Mode of Performativity, the economic sociology of ANT scholars like Callon predominantly engages with the Network and Device Modes. Yet, upon closer examination, a deeper convergence emerges. Both Butler and Callon begin their analyses with representational interventions, whether they are gender norms or economic theories, that catalyze material processes, ultimately generating tangible transformations in sociological phenomena, such as gendered agency or economic systems. Butler (Reference Butler1990; Reference Butler1993; Reference Butler1997) and Callon (Reference Callon2010) also acknowledge the potential for representational interventions to fail in achieving their intended effects and recognize the subversive potential of social realities to be performed in ways that deviate from dominant representations.

Furthermore, Butler and Callon share a common interest in the interplay between representations and materialities in the socio-political engineering of social phenomena (Du Gay, Reference Du Gay2010). Callon’s exploration of performativity resists positivism and essentialism by examining the assemblage of materials, devices, and infrastructures that constitute categories, objects, and agents (Du Gay, Reference Du Gay2010). Similarly, Butler (Reference Butler1993) draw attention to the materiality of the body and its role in the enactment of representations, such as gender norms, in producing gendered phenomena, including human agency, identity, and subjectivity.

This shared focus allows us to argue that, despite employing different conceptual jargon, these scholars share a theoretical core. At its essence, performativity entails a representational intervention that not only describes actors, networks, devices, or representations but also actively alters one or more of them. This process of performation, where a representational intervention is enacted, produces a performativity effect within socio-technical agencements. By bridging these seemingly disparate traditions, the DARN framework provides a robust lens for analyzing the dynamic interplay of representations, materialities, and politics in the ongoing reconfiguration of social realities.

The cohesive framework we introduce here illuminates such often-overlooked yet latently existing commonalities shared by the ‘contradictory’ perspectives within performativity scholarship. In this sense, far from offering a merely pragmatic methodological toolkit to analyze any sociological entity one might conceive of as performed, our perspective illuminates the shared theoretical threads that bind disparate approaches. In doing so, it underscores the coherence of performativity as a distinctive and robust explanatory framework for the distributed universes of social action. As illustrated in Figure 4, our framework foregrounds representations as pivotal entry points for scholarly inquiry, enabling the systematic tracing of the relational dynamics structured within performation processes. These processes constitute and transform entities, shedding light on how representations serve as engines of socio-technical and material change. By anchoring the analysis in the performativity of representations, the framework facilitates a deeper understanding of the mechanisms through which performative interventions shape, stabilize, and reconfigure social realities.

As the concept of performativity teeters precariously on the edge of conceptual overstretch, there arises an urgent need for a framework that is both nuanced and comprehensive – one capable of addressing the escalating misapplication and overuse of the term with intellectual precision and analytical depth. Too often, this overreach crystallizes in such reductive discourses as ‘everything is being performed’, a refrain that reverberates with the echoes of a bygone era, when the popularity during the 1980s and 1990s of apparently attractive but nuanced and overextended understandings of ‘social construction’ and ‘relativism’ overshadowed the insights and careful qualifications of the best constructivist work. Against this backdrop, our framework endeavors to arrest conceptual inflation, offering a more refined and rigorous lens through which to illuminate the performative forces that shape and transform the fabric of our world.

Conclusion

The study of performativity has had something of a meteoric rise in the social sciences, philosophy, and humanities over the past 25 years. This paper offers a foundational map for scholars to identify and analyze instances of performativity across various contexts. It unpacks the complex mosaic of performativity by tracing its trajectory, exploring its multiple manifestations, and highlighting its academic scope. Showing that performativity is a widely used lens in social science and humanities, the paper has analyzed the layered interplay between representation and constituents of an agencement on the ground.

The findings presented here open up a wealth of avenues for future research. The modes of performativity outlined in this paper offer scholars a means to critically evaluate and integrate perspectives that might otherwise seem disconnected or irrelevant to their research focus. By orienting empirical attention toward underexplored modes within specific research traditions, these frameworks can uncover new analytical and theoretical possibilities. Equally significant, the modes of performativity provide clarity for researchers regarding their own objects of analysis, encouraging novel interrogations within disciplines. For instance, while the Actor Mode of Performativity has yet to be explicitly examined in the literature on social movements and collective action, its inclusion could deepen our understanding of how social movement actors’ identities evolve and how they navigate perceived opportunity structures. Similarly, the Network Mode of Performativity that is underutilized in platform studies holds promise for analyzing how platform owners attempt to align the actual operations of their networks with the representations embedded within platform software. Given the increasing centrality of platforms as economic institutions (Stark and Pais, Reference Stark and Pais2021), this mode could shed light on the performative strategies underpinning their governance.

Moreover, the performative production of effects offers direct applications beyond academic research, informing practices such as service design, strategic design, and the construction of auction and platform systems. In this sense, performativity studies are not merely intellectual exercises but have the potential to shape public awareness and policy interventions. Just as an awareness of ideology or discourse highlights the unconscious influences shaping human action, a broader understanding of performativity could strengthen democratic norms in late modernity, fostering accountability and inclusivity in policy and design interventions.

The comparative framework proposed in this paper also invites further exploration of how different modes of performativity intersect and interact within specific socio-political contexts. For example, examining the interplay between the Representation and Network Modes in the creation of economic governance frameworks offers a promising avenue, particularly in the aftermath of global financial crises.

Finally, the concept of counter-performativity, where representational interventions yield effects that undermine or diverge from their intended goals, warrants deeper investigation. Our framework could inspire scholars to investigate how inconsistencies or misalignments in the enactment of sequences of modes of performativity might lead to counter-performativity. Specifically, by examining how disruptions or conflicts between devices, actors, representations, and networks impact the intended performative effects, researchers could gain insights into the conditions under which these interventions backfire. For instance, a poorly calibrated sequence of representational interventions might fail to align with the socio-technical agencements they aim to shape, producing effects that contradict or undermine the original goals. Such inquiries could deepen our understanding of how performativity operates and reveal the mechanisms through which counter-performativity emerges in practice. Understanding the conditions under which counter-performativity arises could illuminate the vulnerabilities and limitations of socio-technical systems, offering critical insights into the fragility and adaptability of the infrastructures that govern contemporary life. By charting these unexamined terrains, performativity scholarship can further establish itself as an indispensable resource for both theoretical innovation and real-world impact.

The underlying motivation of this analysis is to offer an integrative perspective aimed at creating new opportunities for research through structured cross-pollination. Critics may disagree with this approach, countering that a meta-theoretical perspective like the one we build here may further contribute to the proliferation of performativity studies in ways that will dilute the analytical power of this concept. We do not recommend ‘throwing caution to the wind,’ of course. In our view, however, the full potential of performativity remains to be unlocked, and it is by creating new connections rather than setting up boundaries that this can be achieved. We offer our contribution in this spirit.