Introduction

This article contributes to the scholarly debate on central bank scientization by focusing on central bank governors. We argue that a sociology of monetary elites enhances our understanding not only of central bank scientization but also of the dynamics underpinning the scientization discourse.

This study considers the politics of central bank (CB) scientization as related to policies aligned with the neoliberal agenda and the discursive practices that claim scientific legitimacy for monetary policy when democratic political legitimacy is unviable. Instead of adopting definitions rooted in the central banks’ legitimating discourses, we propose an alternative perspective on scientization based on Pierre Bourdieu’s (1975; 2002) theory of social space and symbolic power. Drawing on Bourdieusian concepts, we theorize scientization as a reconfiguration of the interdependence between fields in favour of the scientific field. This sociological perspective links the scientization concept to a hypothetical shift in the balance of power in favour of actors from the scientific field over other actors, especially politicians and bureaucrats. The study tests this hypothesis by examining whether academic professionals and qualified scholars are increasingly assuming leadership roles in central banks, possibly displacing less academically qualified actors.

The scientific field embodies a competitive struggle ‘whose specific stake is the monopoly of scientific authority, inseparably defined as technical capacity and social power’, including the capacity to speak and act legitimately (i.e., with authority) in ‘scientific’ matters (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu1976: 89). At the heart of this struggle is the imposition of a particular worldview. The competition to describe the social world (i.e., to impose representations about it as ‘truth’) extends to all professionals of symbolic production, including politicians, journalists, and others who seek to impose their own worldview (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu1995: 4).

The central question guiding our study is: who has the authority to determine legitimate approaches in monetary governance and to decide on central bank policy, and to what extent is this authority legitimized by scientific credentials? To address this, the empirical analysis focuses on the biographical characteristics of 678 CB governors across the globe from 2000 to 2020. This period enables us to observe the possible impacts not only of the neoliberal reforms of the 1990s and 2000s, but also of the 2008 global financial crisis on CB governance. We examine the educational and professional backgrounds of elite decision-makers governing central banks to identify recent trends favouring scientific profiles. Following recent sociological work on CB scientization centred on discourse, instruments, or the internal organization of central banks (e.g., Marcussen, Reference Marcussen, Christensen and Lægreid2006, Reference Marcussen, Dyson and Marcussen2009; Mudge and Vauchez, Reference Mudge and Vauchez2016; Wansleben, Reference Wansleben2023), we ask whether there is a stronger presence of scientifically trained governors.

A second theoretical concern guides our approach. Against a potentially homogenizing view which would see central banks as variations of a universal and idealized model emulating the Federal Reserve or European Central Bank (ECB), this study aims to uncover the diversity of dynamics shaping central banking globally. It explores potential divergences between the Global North and South, challenging technocratic discourses and the norms often defined by the experiences and interests of the ‘developed’ world (Dezalay, Reference Dezalay2004; Escobar, Reference Escobar1995; Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2002).

We begin with a theoretical exploration of the politico-scientific process of knowledge production on CB scientization. The following empirical sections introduce the methodology and global data analysis from the CENTBANK prosopographical database, including descriptive statistics, data analysis techniques, and qualitative insights. The conclusion synthesizes the main findings, leading us to re-evaluate the scientization hypothesis.

A sociological approach to the politics of central bank scientization

CB scientization is mostly studied and defined in terms of these institutions’ own discourses and strategies for legitimizing their public policies within the context of neoliberal reforms, which disengage monetary policy from institutions built on democratic or traditional political legitimacy. Promoted by global economic elites and powerful organizations such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the insulation of central banks from the direct influence of governmental actors has been studied as a prime example of delegation to non-majoritarian institutions claiming technocratic expertise (McNamara, Reference McNamara2002). Since the late 1980s, CB independence and related legal reforms have been promoted as key elements of CB credibility. These reforms have been applied as part of the ‘new monetary consensus’, which, along with other components such as inflation targeting and floating exchange rates, operates as the dominant monetary policy regime of neoliberalism (Saad-Filho, Reference Saad-Filho2019). As a policy objective, CB independence aligns with the neoliberal technocratic paradigm, emphasizing objective, impartial, disinterested, and depoliticized policy-making (Polillo and Guillén, Reference Polillo and Guillén2005). However, various scholars argue that isolating monetary policy from democratic decision-making is a controversial political intervention which primarily serves the interests of global finance capital (Ayhan and Üstüner, Reference Ayhan and Üstüner2010), with distributional and political consequences favouring neoliberal interests (Palley, Reference Palley2019; Saad-Filho, Reference Saad-Filho2019). Grabel (Reference Grabel1997) suggests that, by facilitating the implementation of policies recommended by the International Monetary Fund, World Bank and other dominant actors, ‘credibility’ reforms have contributed to the global expansion of neoliberal programmes. Their negative effects, particularly in the Global South, have been obscured by technocratic discourses that depoliticize such policies (Grabel, Reference Grabel1997).

Based on these observations, we define the politics of CB scientization as the discursive strategies which accompany neoliberal reforms. These narratives seek to confer scientific legitimacy on monetary governance when reliance on political legitimacy is lacking. Thus, in the neoliberal era, the politics of scientization became a key component of what Lebaron (Reference Lebaron2000a; Reference Lebaron2000b) calls the ‘social process of neutralization’. Highly political processes are presented as ‘neutral’ (hence ‘neutralized’) within monetary authorities composed of ‘wise men’ acting as ‘guardians of money’ (Lebaron, Reference Lebaron2000a: 209). In this respect, central bankers labour under a ‘myth of neutrality’, which presents monetary policy as a purely technical issue, downplaying its political and distributive consequences (Adolph, Reference Adolph2013). As Lebaron (Reference Lebaron2000a; Reference Lebaron2000b) notes, the belief in ‘economic neutrality’ is increasingly underpinned by a belief in science. The centrality of scientific legitimacy in policy-making is only one dimension of the depoliticization observed at various levels of social relations in the contemporary world (Flinders and Wood, Reference Flinders and Wood2015).

Recent academic literature on CB scientization indirectly validates neoliberal technocratic discourses and central banks’ own claims to scientific legitimacy pivoting on ‘transparency goals’ and strengthening their independence. CB scientization is thus examined in terms of a disconnection between politics and central banking. Notably, Marcussen (Reference Marcussen, Christensen and Lægreid2006, Reference Marcussen, Dyson and Marcussen2009) has explored scientization as a ‘reform process’, which endows central banks with ‘scientific authority’, uncoupling them from what he calls ‘formal politics’. He contends that ‘central banking has not only been depoliticized, through a process of autonomization; it has been apoliticized through scientization and, consequently, it may be about to leave the official political game altogether’ (Marcussen, Reference Marcussen, Christensen and Lægreid2006: 82).

Marcussen’s claim contradicts previous research. For instance, Chang (Reference Chang2003) reveals politicians’ indirect influence on monetary policy through appointments in ‘independent’ central banks like the Federal Reserve (Fed) and the ECB. Not only are political orientations important in the appointment of governors, but highly politicized profiles remain prevalent in CB governance (Lebaron and Dogan, Reference Lebaron and Dogan2016).

Rather than taking central banks’ claims for scientific decision making for granted, we examine scientization as a hypothetical reconfiguration of the interdependence between fields in favour of the scientific field. This sociological approach assesses whether power is shifting towards actors from the scientific field who define legitimate ‘scientific’ ways of studying and intervening in the ‘economy’. We evaluate the hypothesis of an embodied ‘scientific culture’ within CB decision-making by focusing on the social properties of leading actors. We examine scientization as a social-historical process through which academic professionals and scholars access CB leadership, potentially displacing less academically qualified individuals. This approach aligns with academic literature that emphasizes the symbolic and social dimensions of scientization, such as the ‘universal paradigm of central banking’ (Lebaron, Reference Lebaron2012) operating as a common international culture and set of norms, increased recruitment of economist researchers in central banks, and their publications in specialized journals (Claveau and Dion, Reference Claveau and Dion2018).

The current literature tends to have a Western-centric perspective, neglecting the implications of scientization in the Global South, where the majority of central banks are located. By focusing primarily on powerful central banks like the Fed and ECB and generalizing findings to the entire central banking world, this literature reinforces the hegemony of these central banks as global models and norm-setters. Few studies investigate the specificities of scientization in leading central banks and the unique conditions shaping them. Mudge and Vauchez (Reference Mudge and Vauchez2016), for example, argue that the ECB’s ‘hyper-scientization’ results from a ‘field effect’ linked to the institution’s origins and position at the intersection of financial institutions, the internationalized economics profession, and the European political order. This ‘triple embeddedness’ requires continuous investment to maintain institutional authority and autonomy (Mudge and Vauchez, Reference Mudge and Vauchez2016). The claim to scientific legitimacy is a strategy used not only by the ECB but also other central banks to define and redefine the boundaries between the state and the economy (Coombs and Thiemann, Reference Coombs and Thiemann2022).

Wansleben’s analysis (Reference Wansleben2023, Reference Wansleben2024) on the rise of central banks as key actors of capitalist financialization demonstrates how these institutions have benefited from, and contributed to, neoliberal change. Major (Reference Major2012: 538) also highlights this central role in neoliberal ‘reregulation’ conceived as ‘depoliticization, or the movement of regulatory activities into technocratic, insular institutions dominated by public finance officials (finance ministries and central banks) and private financial institutions’. The increasing autonomy and authority of central banks over key components of economic policy and regulation reflects the neoliberal reconfiguration shifting power away from agencies subject to political pressure to those insulated from it (Major, Reference Major2012). As Adolph (Reference Adolph2013: 2) notes, despite the ‘masking role of a supposedly perfect form of political independence embodied by the modern central bank’, monetary decision-making is influenced by various ‘outside’ interests, principles and actors, particularly private banks. Our study contributes to this critical literature by showing that, in addition to the political field in which monetary policymaking is embedded, there are other influences that shape central banking.

We focus on CB governors in office between 2000 and 2020 (both years included), a period during which central banking practices were restructured by neoliberal reforms originating in the Global North. This time frame allows us to examine recent trends emerging from or in response to neoliberal transformations. While some governors in our database were appointed during the 1990s, when central banking reforms surged, the majority took office in the subsequent years when these reforms had possibly transformed central banking dynamics worldwide. Focusing on this period enables us not only to analyse the potential relationship between scientization and neoliberalism during a period when the effects of earlier reforms had matured, but also to explore changes in CB governance during and after the 2007-2008 financial crisis, which has been linked to neoliberal policies (Major, Reference Major2012; Saad-Filho, Reference Saad-Filho2019).

Analysing the social trajectories of governors is one way of exploring potential structural changes in CB governance. While there is a tendency to limit the authority of CB chairs by creating monetary policy committees to promote collective decision-making (Marcussen, Reference Marcussen, Dyson and Marcussen2009: 380), many central banks still leave the final say to the governor. CB presidents not only lead the institution, but also personify its leadership. The symbolic power of central banks, while legally grounded, also has a ‘personal’, partly charismatic, dimension: Institutional legitimacy is vested in the ‘spokesperson’ who embodies its authority and contributes to the institution’s reputation (Lebaron, Reference Lebaron2015). In this respect, the appointment of a governor is part of what Mudge and Vauchez (Reference Mudge and Vauchez2022) call ‘reputational signalling practices’. Focusing on these elites is particularly relevant to the study of CB scientization, as ‘in no other financial institution are the governors of that institution portrayed by the media as technical wizards; masters of an arcane knowledge that produces a public good’ (Abolafia, Reference Abolafia, Cetina and Preda2012: 95). Furthermore, a growing body of literature has shown that the social trajectories and characteristics of monetary decision-makers influence their policy orientations and choices (e.g., Adolph, Reference Adolph2013; Lebaron and Dogan Reference Lebaron and Dogan2016, Reference Lebaron, Dogan, Champroux, Depeyrot, Dogan and Nautz2018; Lebaron, Le Roux and Dogan, Reference Lebaron, Le Roux, Dogan, Barth, Leßke, Atakan, Schmidt and Scheit2023).

No comprehensive study has yet focused on the biographies of central bankers to test the scientization hypothesis. Our study does so by studying social stratification at the top of central banks and examining potential changes triggered by the 2008 global financial crisis. Prior research has revealed trends in favour of economists in governor appointments since the 1990s, particularly those with PhDs (Lebaron, Reference Lebaron2000a; Reference Lebaron2008; Marcussen, Reference Marcussen, Christensen and Lægreid2006); but it has also highlighted notable disparities in the global production of this educational capital, primarily originating from Northern universities (Lebaron and Dogan, Reference Lebaron and Dogan2016; Reference Lebaron, Dogan, Denord, Palme and Réau2020). These asymmetries require further consideration. The following sections present our empirical findings after introducing our methodology.

Studying central bank governors’ biographies

This study relies on the CENTBANK prosopographical database, which collates biographical details of CB governors worldwide from the late 1990s. Multiple sources like international and national Who’s Who publications, institutional websites, online press, platforms and databases like Wikipedia, Bloomberg, Zoominfo, 4-Traders, and LinkedIn provided a wide array of prosopographical information (Dogan and Lebaron, Reference Dogan, Lebaron, Badache, Kimber and Maertens2023).

The study focuses solely on individuals who held the position of CB governor between 2000 and 2020. This slightly extends the analysis period as those who were nominated earlier but remained in office in the 2000s are included in the database. The resulting study population encompasses 678 CB governors from 178 countries and territories.Footnote 1 This implies comprehensive coverage despite around 7.5% missing data on key variables which describe: (1) educational and academic backgrounds (fields of study, degree, studies abroad); (2) primary career and professional experience in different sectors (central banking, finance, the private sector, state bureaucracy, politics, universities, and international organizations); and (3) other socio-demographic indicators (age, gender, place of birth). Additional variables on research activities, political engagements and ideological orientations, which could be helpful for further analysis, are excluded due to systematic lack of data.Footnote 2

The missing data are not randomly distributed across variables, countries, and time frames. Our data relies heavily on the primary sources of our study, which are public biographies. We do not scrutinize CB governors based on their actual achievements but based on their public profiles which combine self-presentations and institutional narratives (including media coverage). This focus is intentional and part of the study design to grasp public representations of personified governance and to discern which biographical properties and credentials take precedence or, on the contrary, remain concealed within these ‘strategic identities’ (Collovald, Reference Collovald1988).

Our database provides more extensive data on recent CB governors compared to those appointed in the 1990s and 2000s when internet accessibility for disseminating information was less widespread. The visibility of these elites online varies widely, depending on several factors, including a state’s global position, language prevalence, and even search engine algorithms. This information disparity – especially between the Global North and South – is valuable in examining our research question and is an aspect we further explore in our empirical analysis.

The terms ‘North’ and ‘South’ replace the dated ‘West and the Rest’ division (Hall, Reference Hall, Hall and Gieben1992), highlighting resource and power disparities (for a more elaborate consideration, see Sheppard and Nagar, Reference Sheppard and Nagar2004). However, there is no universally accepted classification or consensus regarding the precise scope of these terms. The Global North primarily includes Western Europe, North America, along with ‘high-income’ or ‘developed’ countries like Australia, New Zealand, Japan, or Israel. The UN’s classification of ‘developed’ and ‘developing’ countries – roughly 27% and 73% of the countries in our database – serves as the benchmark for this study even while we acknowledge the problems associated with these controversial categories that have their origins in European and North American institutions and colonial history (Escobar, Reference Escobar1995; Khan et al., Reference Khan, Abimbola, Kyobutungi and Pai2022; Rist, Reference Rist2001).

The social determinants of CB governance scientization

This section presents the results of the descriptive statistics of our prosopographic database. The findings are organized into six points outlining the characteristics and trends regarding scientization in CB governance.

Regional variability in CB governors’ visibility

Empirical data confirms a key argument of our study: CB governors are public actors with high visibility. We possess key educational and professional data for 80% of the CB governors in our database, with minimal missing information. For the remaining 20%, we have at least half of the crucial data (7 over 14 key variables) for approximately 11%, while roughly 9% have limited or inaccessible biographical details.

The visibility of CB governors varies among countries. Notably, governors from the Global North have higher visibility, with 98% of governors having extensively available biographical information. Considerable disparities exist, however, in the Global South. Locating information on CB governors is challenging in countries where they operate as bureaucrats behind the scenes, akin to other state departments, often under the leadership of a single party or charismatic (or authoritarian) political figures (e.g., North Korea, Turkmenistan, etc.). Finding governors’ public profiles is also difficult in countries experiencing war or significant conflict, especially when coupled with economic or humanitarian crises (e.g., Afghanistan, Burundi, Iraq, Mauritania, or Yemen).

These observations challenge the scientization hypothesis, both according to controversial common definitions (transparency, accountability, etc.) and our own. Without publicly available scientific credentials, it is difficult to claim scientific authority over decision-makers. The academic degrees of 17% of governors and the fields of study of 13% are not publicly available and are missing from our database. However, data is available on the primary career of 93% and other work experience of 90% of governors.

Dominance of male economists in CB governance

This study largely spans the neoliberal era, during which economics wielded substantial influence in reshaping power dynamics in the field of finance (Fourcade, Reference Fourcade2006; Lebaron, Reference Lebaron2000b; Maesse et al., Reference Maesse, Pühringer, Rossier and Benz2021, Markoff and Montecinos, Reference Markoff and Montecinos1993). The analysis shows how this transformation reverberated in monetary governance and the configuration of policymaking elites, by revealing that approximately 77% of governors in office since the 2000s have a degree in economics. This result confirms previous findings on the dominance of economists in governor positions since the late 20th century (Lebaron, Reference Lebaron2000a; Lebaron and Dogan, Reference Lebaron and Dogan2016; Reference Lebaron, Dogan, Denord, Palme and Réau2020).

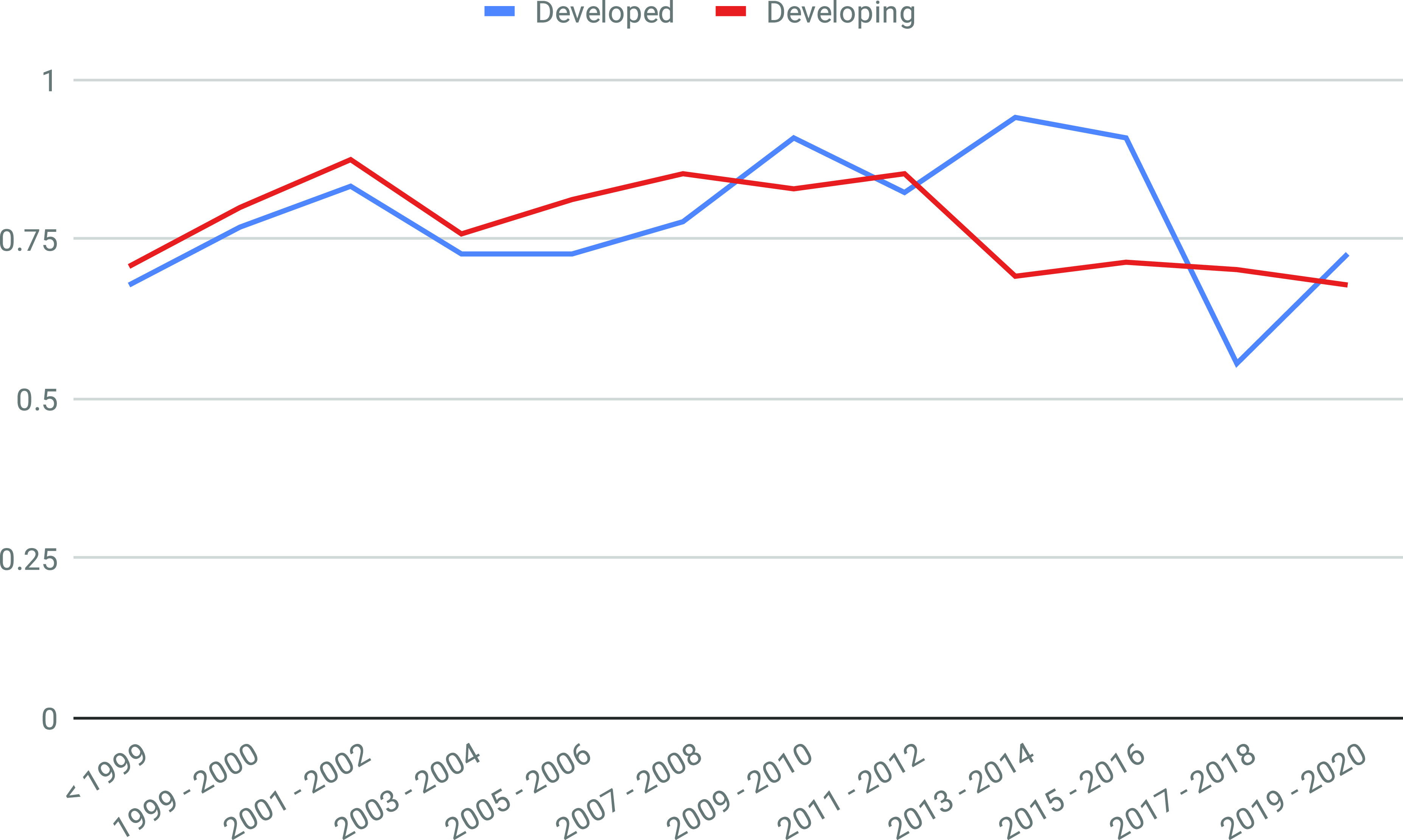

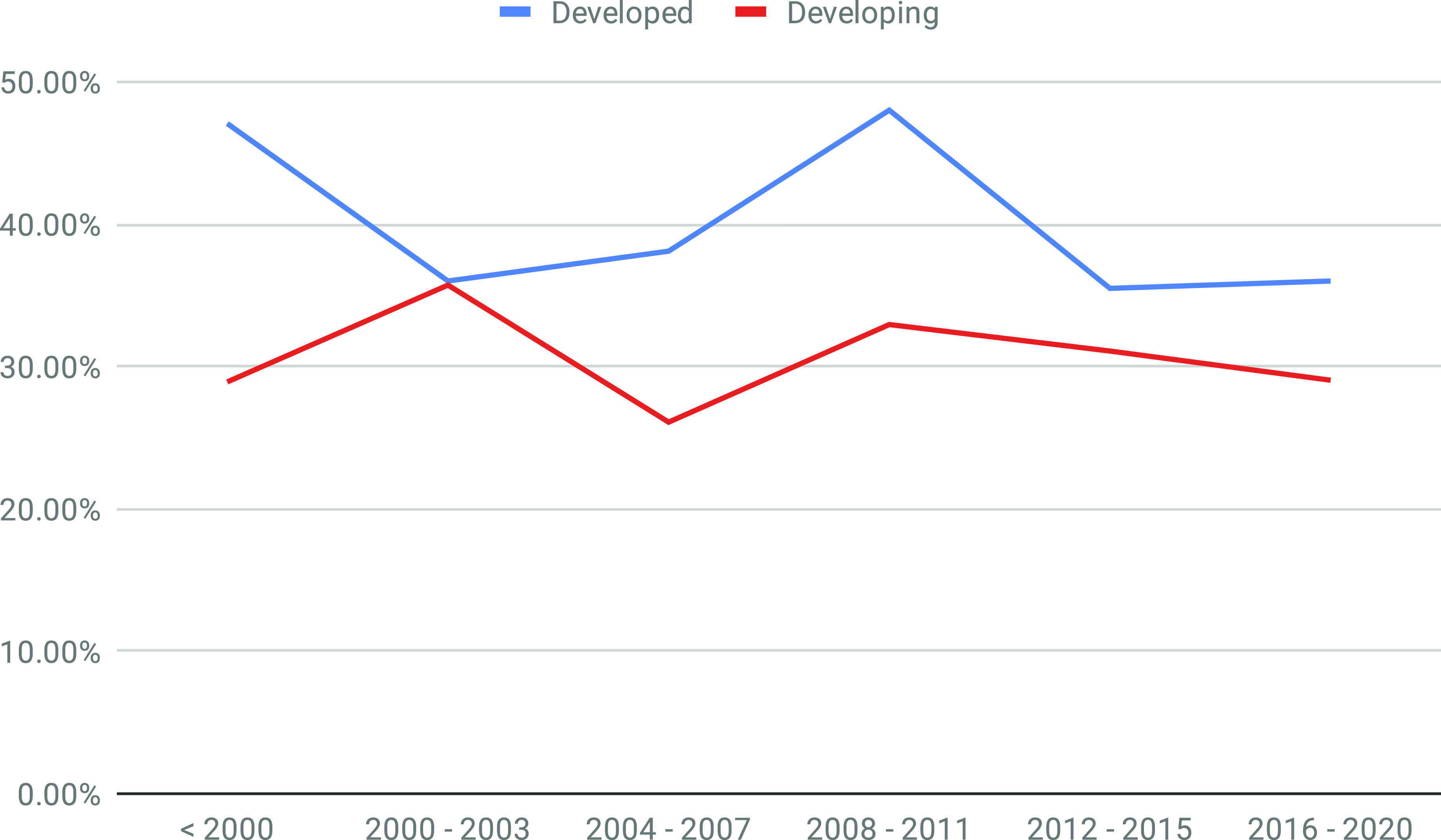

This trend is global, exhibiting little variation between the developed and developing worlds, at least until the 2007-2008 financial crisis. Figure 1 displays the share of governors with (at least) a degree in economics among overall appointments calculated in two-year intervals to mitigate annual fluctuations. Before the crisis, this proportion was slightly higher in the developing world. During the 2010s, this proportion declined in the developing world, but the decline was much sharper in the developed world despite a gradual upward trend until 2015. It should be noted that this group is highly sensitive to yearly fluctuations due to fewer observations.

Figure 1. Share of economists in two-year interval CB governor nominations. Notes: N=160, with 160 developed and 429 developing. Each interval calculates the share of economists among those nominated to the CB governor position during the corresponding period. Note that the appointment period extends into the 1990s, as most governors in office during the 2000s were appointed before 2000.

While further data collection is necessary to comprehend long-term evolution, the current data calls into question the perceived steady rise in economist appointments. The average percentage of governors with an economics degree (76% in developing and 78% in developed countries) suggests a potential saturation point. If there was an escalating trend, it likely halted and possibly reversed, especially after the global financial crisis.

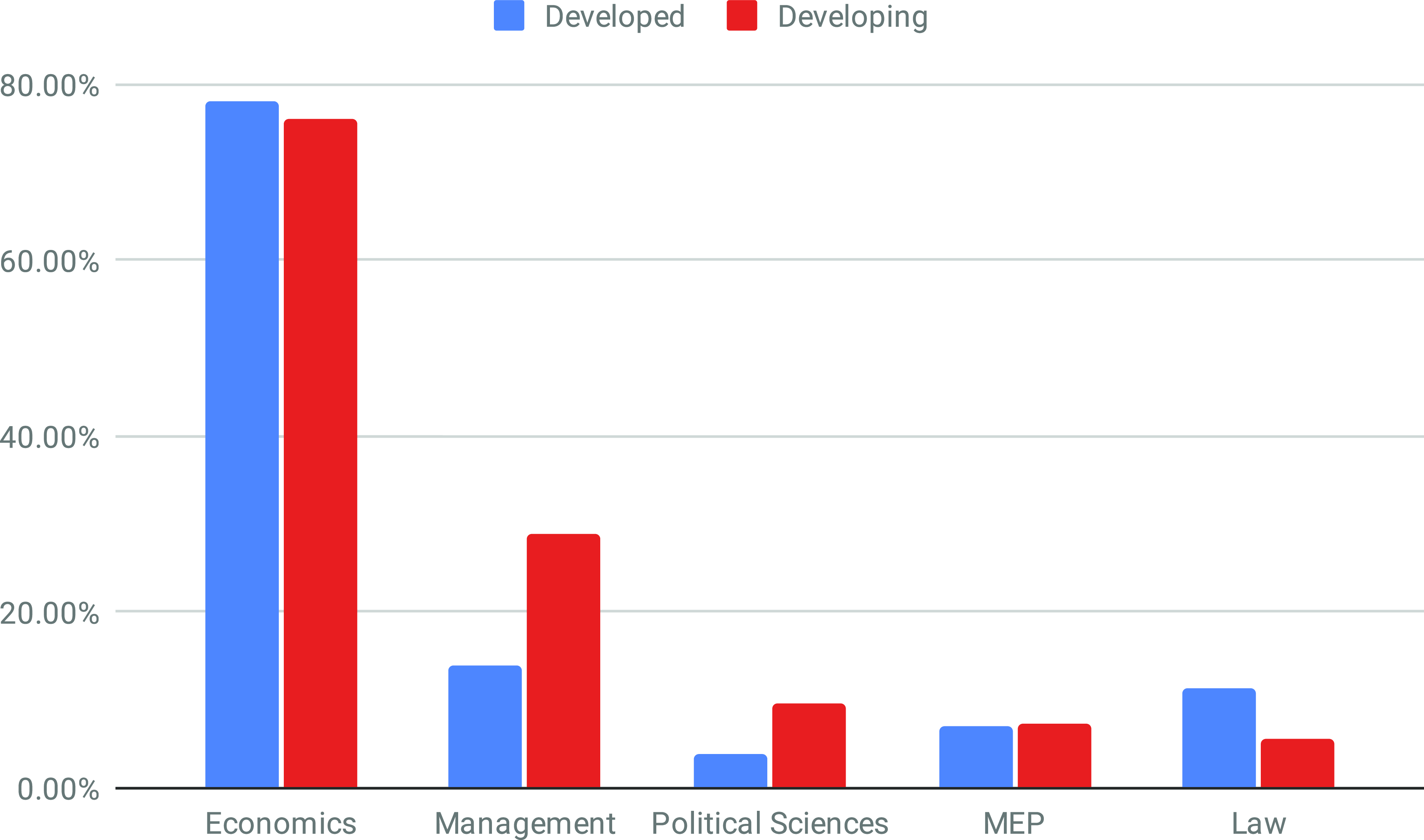

The second most common field of study, shared by 25% of governors, is management sciences, including business administration, finance, commerce, banking, and accounting. While management sciences may have a similar curriculum to economics in certain national programmes, these degrees do not provide the same academic credentials as an economics degree (Fourcade and Khurana, Reference Fourcade and Khurana2013). They emphasize stronger ties with the field of private business than that of science. The substantial gap between economics and management degrees shown in Figure 2 is in fact even greater, with around 10% of governors holding both degrees. Note, however, that this proportion is only 4% in the developed world. In fact, Figure 2 reveals that the share of governors who studied management sciences is much higher in the developing world (29%) than in developed countries (14%) where law degrees hold almost as much importance (11%). This field of study is not among the major disciplines which open the way to CB governance in developing countries (only 6% taking into account studies in Islamic Law). Conversely, political sciences (including public administration, international relations, and public policy), while being the third most prevalent field of study in these countries (10%) is not common among the governors of the developed world (4%). Even including the 2% (in both cases) who studied other social sciences (sociology, history, philosophy, geography, etc.), these disciplines do not compete with economics and management sciences. Likewise, only 8% of governors have a degree in mathematics, engineering, or physics (MEP), while other disciplines (statistics, agriculture, military, etc.) represent only marginal cases.

Figure 2. Share of CB governors according to fields of study. Notes: N= 588, with 159 developed and 429 developing.

Note, however, that economics and management degrees may be overrepresented in our database, potentially obscuring other disciplines. The lack of data, particularly in the Global South, might mask minor trends towards other fields due to a tendency to conceal educational backgrounds that do not align with normative expectations in the central banking field. This is mainly a qualitative observation, based on biographies that emphasize credentials in economics, for example, by noting that the individual majored in economics while studying another discipline (business, finance, public policy, etc.) or that they have completed certificate programmes.

Furthermore, these results might lead to the false assumption that the main characteristic central bank governors share with each other is their academic credentials in economics. According to data, their principal common property is being male. The share of women governors since 2000 is only 7%. This asymmetry which might find meaningful explanations in the feminist literature regarding the gendered distribution of power positions is a global trend with minor variations between the developed (8%) and developing (7%) countries. Highlighting how gender dynamics overwhelm other factors – including scientific credentials – in accessing monetary governance, this observation constitutes a counter argument for the scientization hypothesis.

Academic degrees of CB governors

A PhD degree seems to be a prerequisite for access to CB governance, particularly in the developed world, where 55% of governors hold equivalent or higher (post-doc) degrees, thus indicating a process of ‘academization’ (Lebaron, Reference Lebaron2012). However, Table 1 challenges the expectation that CB decision-makers primarily use PhDs to certify their scientific qualifications. Globally, more than half of the governors (58%) in our database do not have degrees beyond a Master’s. This observation is mainly associated with the predominance of Master’s degrees (46%) in the developing world, where Bachelor’s degrees are also relatively common (16%). The proportion of governors without degrees exceeds that of postdocs.

Table 1. Central bank governors’ academic degrees, 2000-2020.

Notes: Academic degree is considered in terms of the latest diploma. No degree indicates governors without any academic degree. Postdoc is a qualification obtained through post-doctoral research programmes.

This table potentially overestimates the share of postgraduates for the same reason mentioned in the previous section. The absence of data concerning academic qualifications (17%) may relate to a reluctance to disclose weaker academic backgrounds. Biographical sources and the press may refrain from mentioning that the governor has no university degree or has a Bachelor’s, especially when the field of study is unconventional in central banking. This might explain why we find more information on career trajectories than educational background. This hypothesis accentuates disparities between the Global North and the Global South, which concentrates missing data on academic degrees.

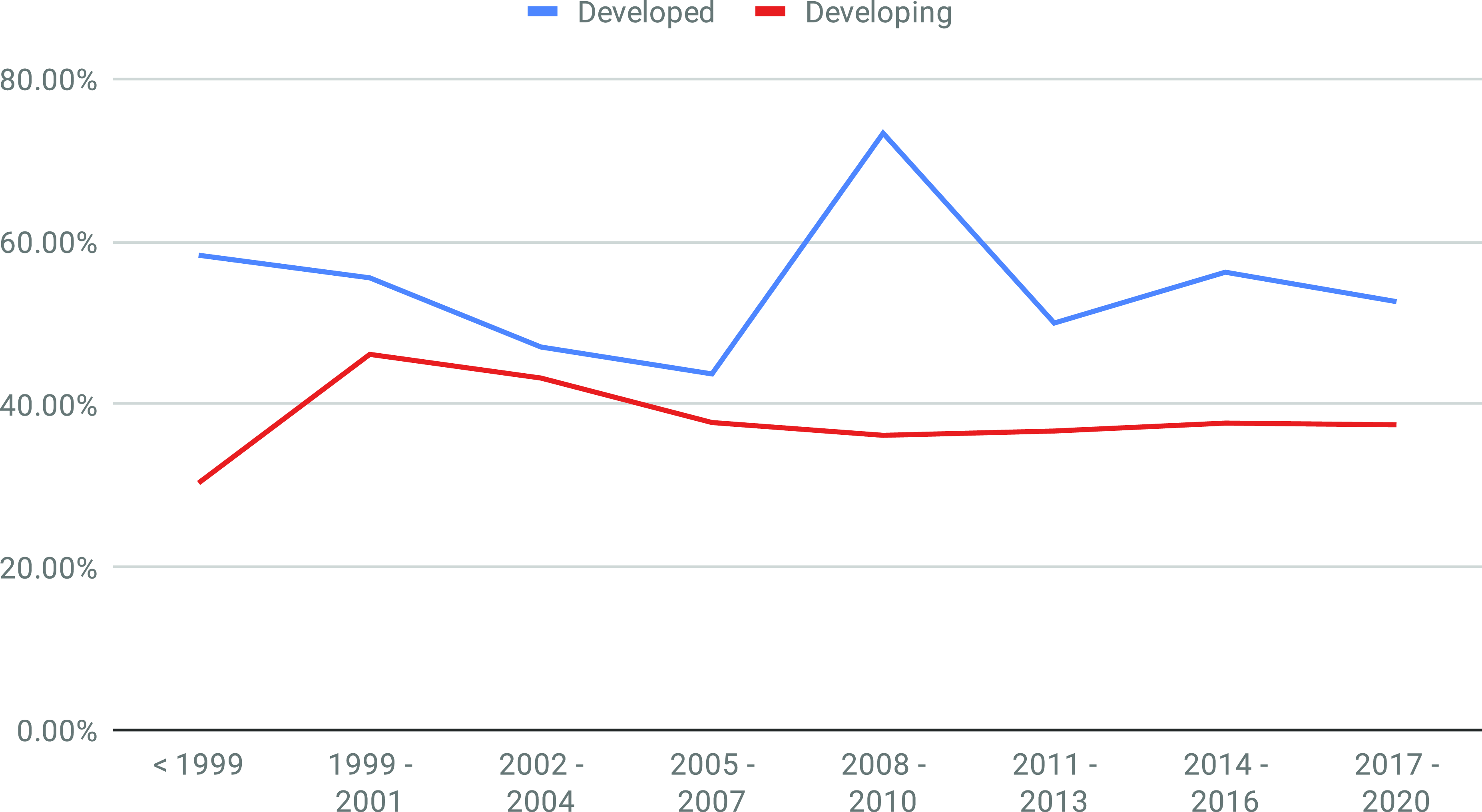

The disparity between the developing and developed worlds was even more pronounced for governor appointments before 2000 where the share of Bachelor’s degrees was respectively 22% and 17%, and that of Master’s graduates was 48% and 27%. Does this imply that the proportion of PhD holders has been increasing in the developing world since the 2000s? Significant variations exist in the evolution of academic degrees, and in particular the PhDs, especially when examining the Global North and South separately. Figure 3 aggregates the share of PhD holders in three-year nominations in developed and developing groups. It shows that their proportion is generally lower in the latter, possibly exhibiting a declining trend in the long run after a sharp increase at the beginning of the 2000s. Conversely, in the developed world, where the proportion of PhD holders is higher, the decreasing trend since the 1990s was interrupted by the 2007-2008 financial crisis, leading to an increase in the following three years. Subsequently, the proportion seems to have stabilized at approximately 50 to 60%, although additional data is needed to confirm these observations.

Figure 3. Share of governors with a PhD in total nominations, 2000- 2020. Notes: Calculated in three-year intervals. N = 561, with 153 developed and 408 developing.

Figure 4 highlights that a majority of PhD holders have a degree in economics, indicating a specialization among those with higher academic qualifications, reflecting scientific and cultural capital. This observation could serve as an argument for scientization in CB governance if the number of governors with PhDs continues to rise in the future. Long-term research is necessary to determine whether there is indeed a trend toward specialized academic capital.

Figure 4. Share of economists by degree. Notes: N = 553.

The dominance of the Anglo-American universities

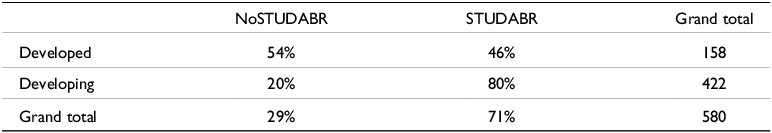

We have data on the location of study for 580 CB governors (86% of total). Of these, 411 (71%) studied abroad, with the majority (339) coming from developing countries. When it comes to overseas education, the contrast between the Global North and South is striking. While the majority of governors in the developed world were graduates of national institutions, 80% of those who had access to the same position in the developing world held foreign diplomas (Table 2).

Table 2. Studies abroad.

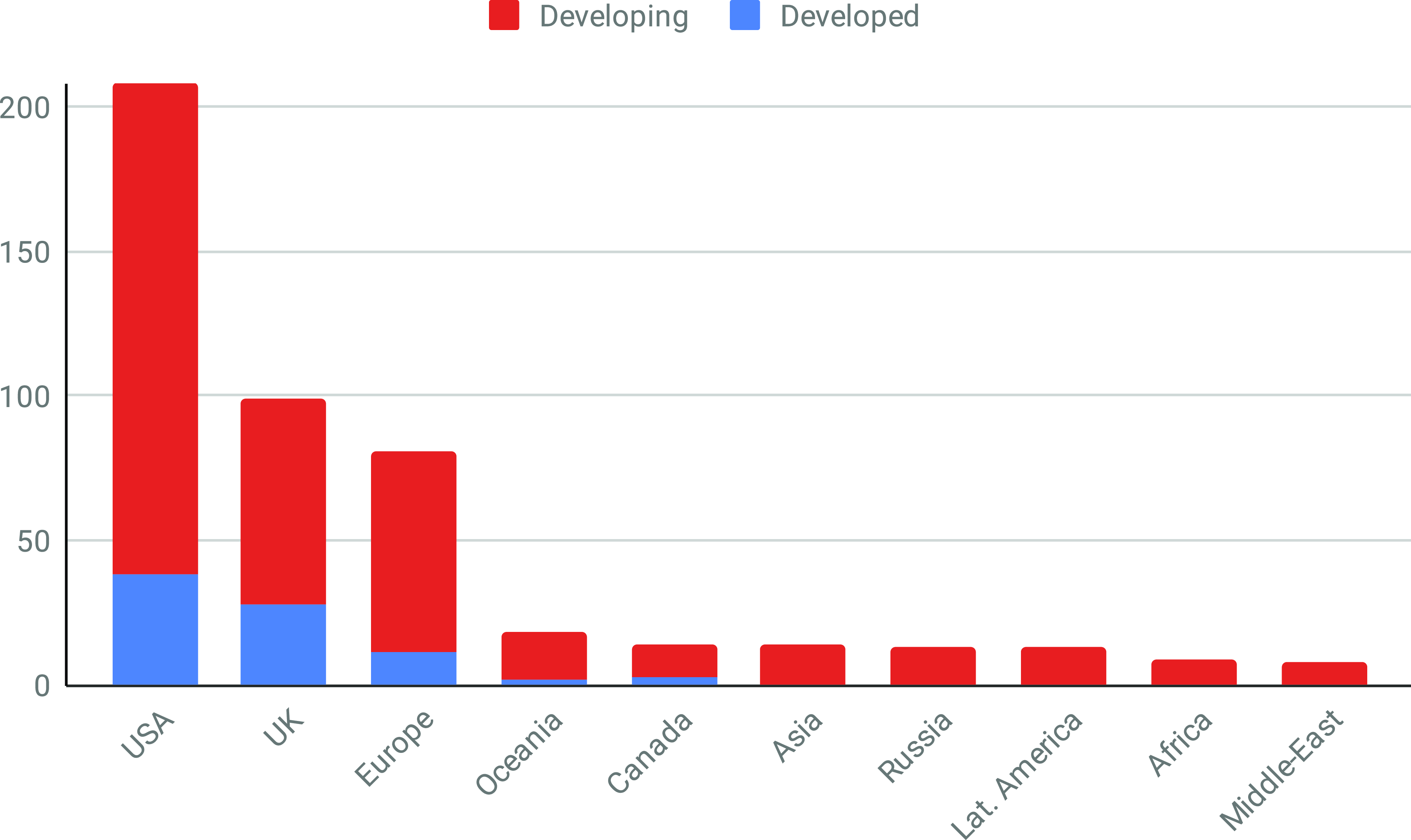

The diplomas required for access to monetary governance worldwide are primarily supplied by the Global North. Among the 411 governors who studied abroad, 51% acquired diplomas from US universities, and 24% studied in the UK (Figure 5). Of these, 20 (5%) have studied in both the USA and the UK.

Figure 5. Destinations for studies abroad (multiple destinations are possible).

The global asymmetry in the production of hegemonic knowledge and diplomas certifying cultural and academic capital is rooted partly in colonial and imperialist legacies. In Europe (excluding the UK), which is the third most common destination for overseas studies of governors (20%), France stands out, with its grandes écoles and universities in Paris attracting students (33 CB governors in our database) from the French (post)colonial zone. A similar relationship exists with the Netherlands (10 graduates in our database), although less pronounced than in the French case. Looking at central banks in former Dutch colonies, governors often hold diplomas from ‘metropolitan’ universities (Appendix, Table 5).

The legacy of colonial imperialism does not fully explain the observed asymmetries. Figure 6 illustrates that, while the global financial crisis briefly favoured national graduates in CB governor appointments worldwide, the importance of foreign diplomas for accessing top-level monetary decision-making has been increasing in the developed world since the 2000s. The growing trend implies a potential convergence with the share of overseas education in the developing world. The privileged diplomas for access to monetary governance in the Global North are also primarily supplied by the USA and the UK (Figure 5).

Figure 6. Share of studies abroad in total nominations in four-year intervals. Notes: N=580, with 158 developed and 422 developing.

Diplomas from prestigious US and UK universities have become valuable assets, acting as ‘wildcards’ to secure positions of power including the role of CB governor. As Fourcade (Reference Fourcade2006: 152) puts it, these campuses operate as ‘elite licensing institutions for much of the rest of the world’. The US is the dominant supplier of highly regarded credentials for access to CB governance globally, concentrating the most favoured institutions. At least 70 governors have studied at Ivy League universities which function as global elite institutions with intense stratification based on social background, particularly class (see Mullen, Reference Mullen2009). Harvard appears to provide the most powerful diploma with at least 27 governors in our database, followed by Columbia University (14) and University of Pennsylvania (12). Other most frequented institutions in the USA are highly competitive elite universities such as University of Chicago (11), MIT (10) and University of Illinois system (10). In the UK, Oxford (at least 18 graduates), Cambridge (10), LSE (11) and other London universities (15) have been contributing to the (re)production of the global monetary elite (Appendix, Table 5).

These training centres can be compared to the foyer central des valeurs (central hub of values), a concept articulated by Maurice Halbwachs (Reference Halbwachs1912) to study social stratification. According to Halbwachs, societies are structured as concentric circles with a central core, where interpersonal relations and social interaction are most intense and contribute most to setting prevailing values and norms. In the world of central banking, prestigious US and UK academic centres connected to dominant central banks, act as central hubs. While they show a certain diversity in their political and scientific traditions, they predominantly produce the hegemonic knowledge that permeate monetary authorities, through the influence of their governors (Lebaron and Dogan, Reference Lebaron, Dogan, Denord, Palme and Réau2020). Overall, few institutions have disproportionate power in forging what Gerth and Mills (Reference Gerth and Mills1953) would call the ‘character structure’ of CB governors with possible implications in terms of groupthink. This institutional stratification likely reinforces homogeneity of norms, values, control mechanisms and convergence in the structure of personal and collective networks and ‘habitus’.

No other country is able to rival USA and UK as educational centres, including France, which appears third in the list, albeit with merely 33 graduates. Canada, which is the fourth destination, has provided a university degree to only 14 governors. Other destinations include Russia (13) and Australia (12), which attract international students from neighbouring countries, a probable result of historical geopolitical influence. However, these countries do not compare with the top two providers of academic credentials. At least 286 CB governors between 2000 and 2020 (70% of those who studied abroad) earned their degrees in the USA and the UK, underscoring the dominance of these nations in exporting monetary policy knowledge.

These observations confirm the findings on the global field of economics (Fourcade, Reference Fourcade2006), emphasizing the internationalization of specific economic thought and the asymmetrical relationship between international producers and local importers of this knowledge (Dezalay and Garth, Reference Dezalay, Garth, Mallard, Paradeise and Peerbaye2010). Rather than supporting the scientization hypothesis, these insights help to explain how a certain ‘uniformity of beliefs’ (Fourcade, Reference Fourcade2006: 160) in global monetary governance is maintained through the uneven circulation of elites and hegemonic knowledge. They also help to understand how the export market for expertise is structured by the asymmetrical dissemination of legitimate perspectives on the economy and economic policy through a network of hegemonic institutions (Dezalay and Garth, Reference Dezalay, Garth, Mallard, Paradeise and Peerbaye2010).

Including education in Europe, Canada, and Oceania, 379 governors – 93% of those who studied abroad – received their diplomas in the Global North. This trend highlights the importance of symbolic imperialism in the contemporary global order, as highlighted in previous observations (Dezalay, Reference Dezalay2004; Dezalay and Garth, Reference Dezalay, Garth, Mallard, Paradeise and Peerbaye2010).

Insiders with long careers in central banking

While CB governors, as an elite category, display a high degree of multi-positionality (Dogan and Lebaron, Reference Dogan, Lebaron, Badache, Kimber and Maertens2023; see also the case studies in the qualitative analysis below), their main career patterns can be identified and examined on the basis of two criteria: (1) the number of years spent in a particular institution or function; and (2) the relative importance of specific positions, in particular the most recent position that paved the way for the individual’s nomination to the CB governance.

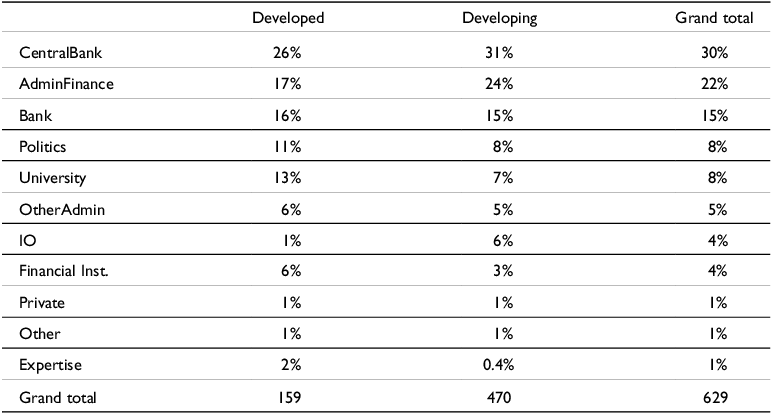

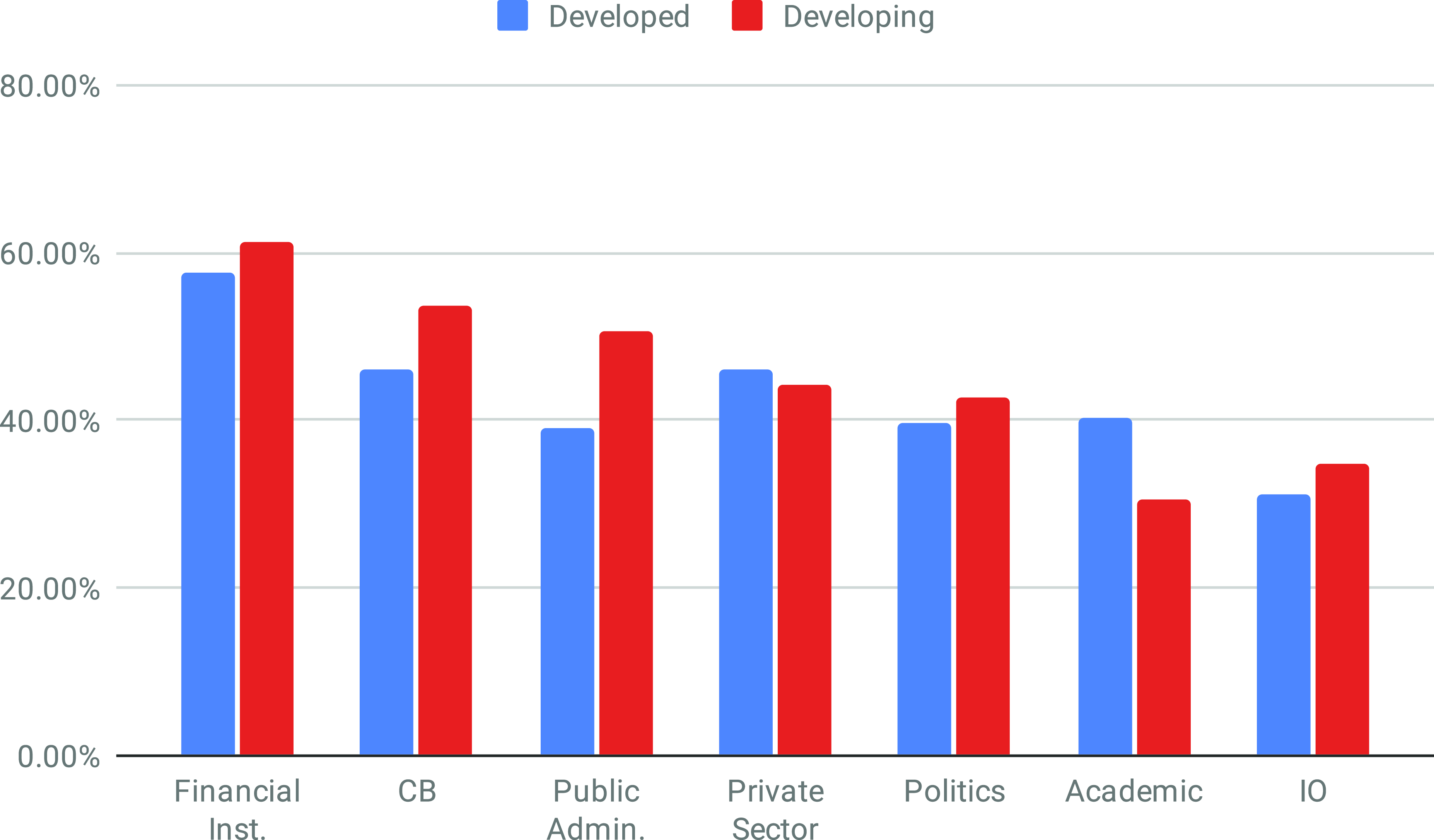

According to biographical data, CB governors predominantly emerge from the ranks of monetary authorities themselves. Table 3 shows that 30% of governors have ascended to their positions from within central banks, suggesting a prevalent trend, especially in the developing world, where 31% of governors have followed a similar path, compared to 26% in the developed world. Rather than necessarily signifying scientization, this pattern reflects a preference for insiders sharing the institutional habitus acquired through hands-on experience.

Table 3. Main career of central bank governors (before nomination), 2000-2020.

Contrary to the scientization hypothesis, as we interpreted it, our data shows that only 8% of governors come from academic backgrounds. The percentage of those involved in research activities remains low at 9%, even when considering experience in non-academic research institutions such as government and public sector research initiatives, think tanks or private consultancy and advisory service providers (grouped as Expertise in Table 3). While the proportion of academics in the developed world is 13%, visibly higher than the developing world at 7%, it is still lower than the prevalence of politicians and other career paths. In the developing world, where the proportion of politicians is also lower (8%) than in developed countries (11%), it also exceeds that of academics (7%).

The data reveals that CB governance remains deeply rooted in the bureaucratic field. Around 27% of governors originate from public administrations, with 22% hailing from economic and financial bureaucracies (e.g., Finance ministry, Treasury, fiscal commissions, supervisory councils, public investment funds, financial regulatory bodies, planning institutes, etc.). This trend is more pronounced in the developing world (24%) than in developed countries (17%). Public administration emerges as the second most common career path to CB leadership in both regions. This suggests that monetary authorities still operate within public finance at the intersection of political and bureaucratic fields, rather than evolving into autonomous scientific institutions like universities.

The influence of financial actors in monetary governance also contradicts the scientization hypothesis. In fact, 19% of governors come from the field of finance, including 15% who built their careers in private or public banks.Footnote 3 The percentage of financial actors in the developed world (22%) surpasses the developing world (18%). This disparity would disappear if we take into account careers in international financial institutions such as the IMF, World Bank, and other multilateral development banks. Indeed, international organization (IO) careers (6%) also rival academic backgrounds in certifying expertise for CB governance in the developing world.

These findings challenge the narrative of scientization, indicating that scientific profiles do not dominate over non-academic ones, particularly the highly politicized ones. Figure 7 demonstrates that political and academic profiles are not in direct competition but instead compete against insiders, bureaucrats, and financial actors, a global trend since the 2000s. In the wake of the global financial crisis, the developed world witnessed a steady increase in the share of politicians and academics, while the developing world experienced a significant decline in the share of academics between 2000 and 2016.

Figure 7. Share of academic and political careers. Notes: N=629; with 159 developed and 470 developing.

Professional experience: The weight of the financial sector

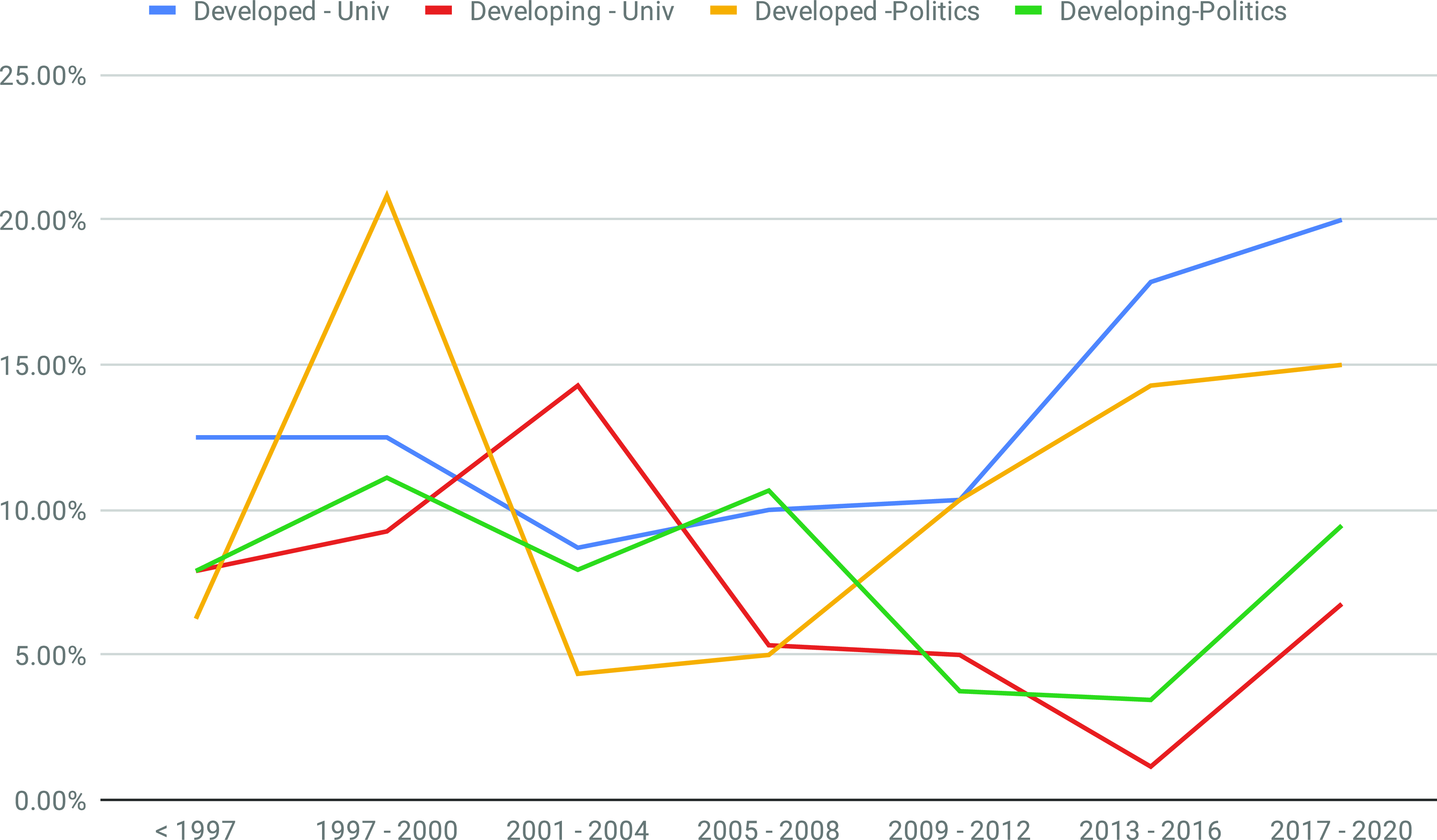

We possess data on around 620 CB governors’ professional experience in different sectors, revealing that 67% of them have diversified work experience in more than one sector. This trend is especially pronounced in the developed world (71%).

Figure 8 highlights the sectors where CB governors have gained experience. A significant 60% hold experience in the financial sector. Private sector experience is notable, accounting for 45% overall. Over half of the governors (52%) have held prior roles within the CB itself, particularly higher in the developing world (54%) than the developed world (46%). Experience in state bureaucracy and public administration is also rather common (48%), more prevalent in the developing world (51%) compared to the developed world (39%). The involvement of governors in politics (42%) is a global phenomenon and is more important than their experience in academia (33%), particularly in the developing world. In this group, international organization experience is even more common than academic activity, indicating that CB governors tend to have more experience outside the scientific field.

Figure 8. Experience in professional sectors. Notes: Each percentage is calculated based on total answers for developed and developing world in each variable. N= 620, with 161 developed and 459 developing. The ranges are respectively 600-626; 154-161; and 446-465.

Contrary to the hypothesis of a growing importance of the scientific field in monetary governance, Figure 9 does not exhibit a consistent upward trend in academic experience of CB governors. While the 2007-2008 crisis potentially led to a brief increase in appointments with indirect academic links, this trend appears to have reversed post-2011.

Figure 9. Work experience in academia. Notes: N=620; with 161 developed and 459 developing.

Exploring the global social space of central bank governors

To enhance our findings, we use Geometric Data Analysis (GDA), specifically Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA), which is a statistical technique designed to analyse multidimensional categorical data, revealing multifactorial patterns and relationships. Drawing upon the works of Le Roux and Rouanet (Reference Le Roux and Rouanet2004, Reference Le Roux and Rouanet2010) and Le Roux (Reference Le Roux2014), this GDA methodology allows for a comprehensive examination of interrelations between variables and the visual representation of CB governors in a global social space.Footnote 4 We first examine the cloud of categories to visualize the relationships between socio-biographical characteristics based on the contributions of different categories. We then conduct a cluster analysis (hierarchical aggregative clustering) to identify groups of governors sharing similar characteristics within this social space.

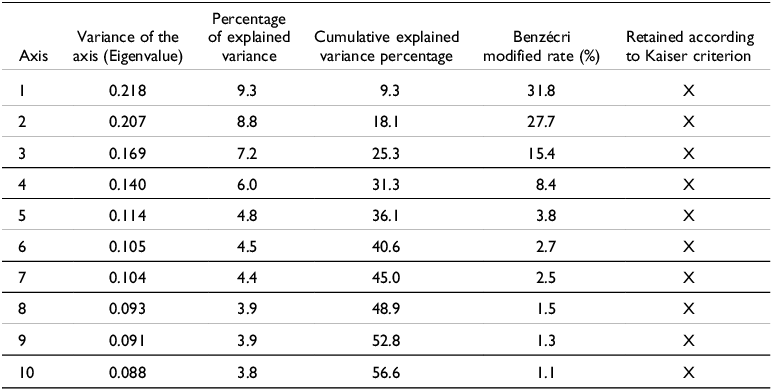

The specific MCA conducted on 576 cases, which present sufficient information across 12 active questions, reveals a total variance of 2.347. Table 4 highlights the complexity of the dataset, with ten axes that account for 56.6% of the total variance.

Table 4. Specific MCA principal indicators.

Notes: N=576; with 12 active questions. First 10 axes displayed here. Variance of the cloud (matrix trace) is 2.347.

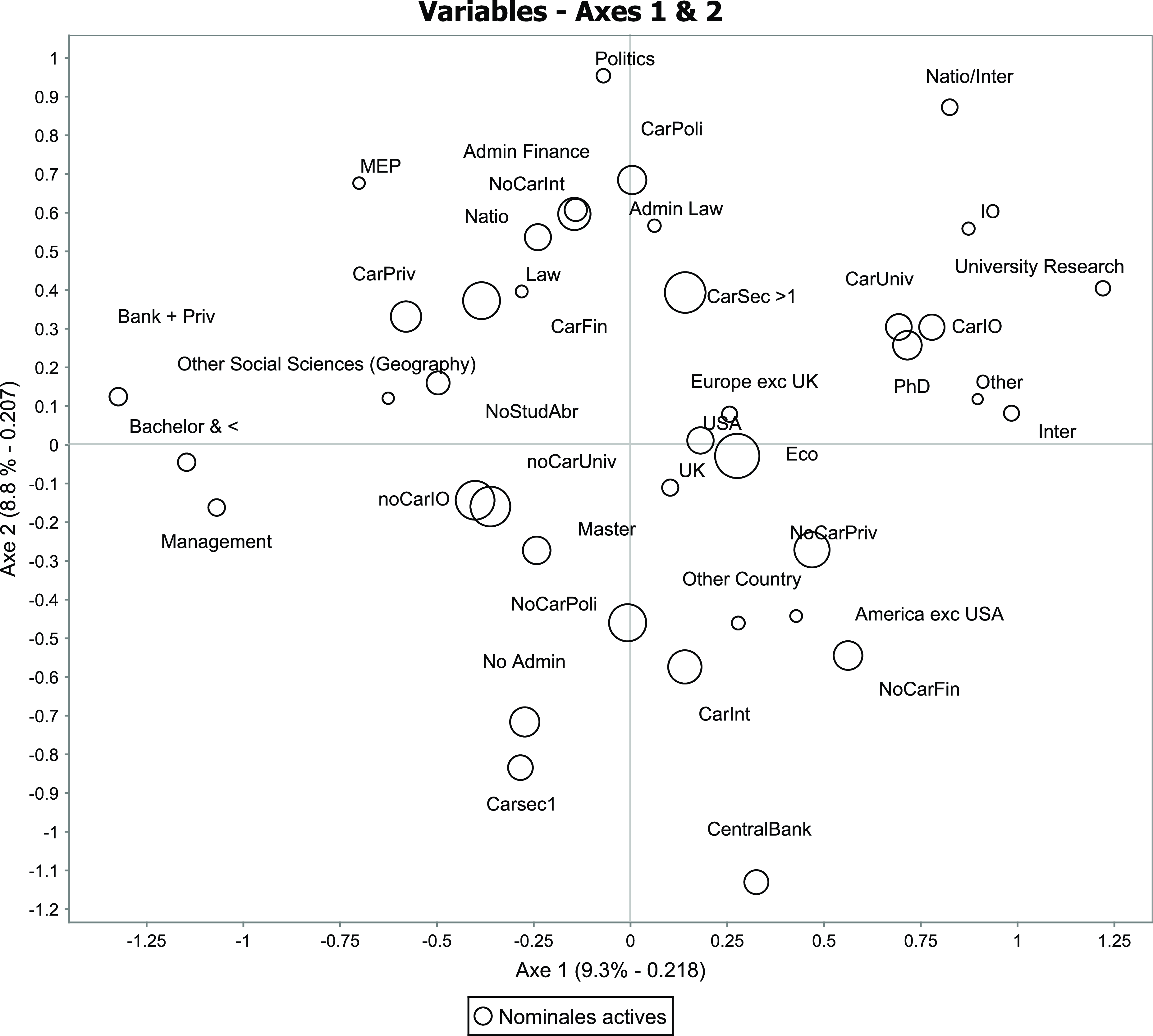

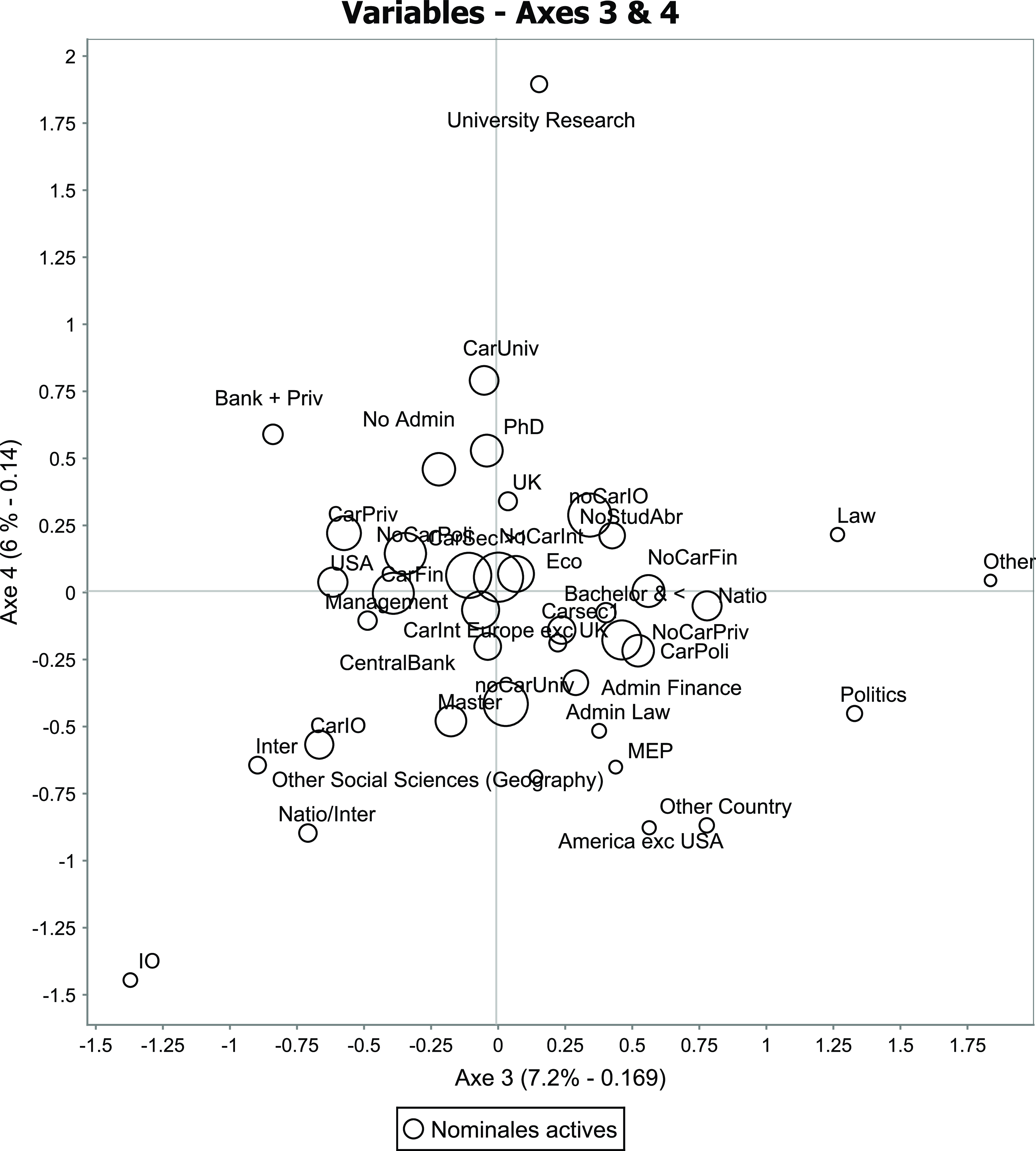

Notably, the first axis accounts for 9% of the raw variance and holds higher importance according to the Benzécri modified rate.Footnote 5 This rate is very low for the last six axes, indicating that they are not adept at representing the data. We will focus on the first four axes for interpretation as they account for 31% of the raw variance and a cumulative modified rate of 83.3%, while it should be noted that the relative importance of the fourth axis is lower than the first three according to the percentage of variance (including the Benzécri rate) explained by these axes. Our interpretation of these axes is based on the contributions of questions and categories (Figures 10 and 11), as elaborated below:

-

1. Academic vs. private managers axis. The first axis contrasts academic careers with managers. On the right side, we find CB governors with academic backgrounds (PhD) and main career trajectories in university and research. The opposite side exhibits governors with much lower levels of academic capital holding bachelor degrees in management sciences (mostly obtained from US universities) and professional experience in the private sector and especially finance.

-

2. Insiders vs. politicians and bureaucrats axis. The second axis highlights a dichotomy between central bankers (insiders within the field) and those who have experience in politics or national and international bureaucracies.

-

3. International vs. national administrative profiles axis. The third axis shows a divide between governors with international versus national administrative backgrounds. It portrays international officers on the left side and national public administrators and career politicians on the right side.

-

4. IO trajectories vs. academic trajectories axis. The fourth axis pits governors with careers in international organizations against those with academic experience.

Figure 10. Representation of categories of variables on the first two axes.

Figure 11. Representation of categories of variables on the third and fourth axes.

These observations highlight that scientific profiles contrast with governors from private finance with management (bachelor) degrees or – to a lesser extent – international profiles rather than political or bureaucratic ones. Instead, a strong opposition is observed between political careers and central bank insiders.

Figures 10 and 11 display variables on the first four axes which will serve for the cluster analysis by establishing a cloud of individuals (plane 1-2 and plane 3-4). Figure 12 below illustrates the global North and South country groups along the first four axes based on the development taxonomy. These visuals show a heterogeneous mix of profiles in the global South positioned at the centre in axis 1 and 2, and leaning more towards international trajectories on axis 4. The global North governors, on the other hand, lean slightly more towards academic pathways (axis 4) and diverge slightly from the general tendencies by concentrating more PhDs (axis 3). These observations emphasize the need for further examination of regional tendencies and variations rather than a narrow focus on the two world groups. In particular, the contrast between political and CB insider profiles in the first two axes would gain further insight by examining the notable divergence between the academically less qualified political trajectories in Eastern Europe and the governors in Polynesia and Melanesia who have spent their entire careers in central banking (see Figure 14 in the Appendix).

Figure 12. Representation of categories for developed and developing country groups and date of appointment on the first four axes.

As for the date of governor appointments, the analysis does not reveal a recent trend towards more scientific profiles. Instead, it suggests a slight decrease in the importance of academic qualifications for access to CB leadership after financial crises (Figure 12).

In sum, there is no discernible trend towards more academic profiles over time or a substantial variation associated with the level of development. These results challenge the scientization hypothesis, which suggests an increase in scientific profiles and a distancing from the political field among CB governors. The study will now proceed to a clustering analysis.

Diverse profiles of CB governors

Employing Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering (AHC) using the Ward method on all axes derived from the MCA, a five-cluster partition provides distinct sub-groups among CB governors, depicted in Figure 13. Cluster 1 reflects an academic profile, while Cluster 2 comprises insiders. Cluster 3 represents international profiles, Cluster 4 consists of private and financial trajectories, and Cluster 5 is associated with bureaucratic and political profiles.

Figure 13. Five-clusters partition by AHC represented in first and second principal planes of MCA.

Notably, Cluster 1 is characterized by a statistically significant over-representation of CB governors from developed countries. This underscores that the purported scientization model is mainly situated in the Global North. This trend is slightly more pronounced among recently appointed CB governors (post-2014), hinting at a localized and limited shift.

By integrating the MCA and AHC outcomes, a nuanced perspective emerges regarding the division between the Global North and South. Contrary to a stark divide, the Global South displays heterogeneity as well as strong connections to global trends. Conversely, Global North governors exhibit more uniform characteristics, relating to a distinct subgroup within the global field of monetary governance.

Insights from qualitative analysis and case studies

While quantitative analysis of biographies yields valuable insights, it inadequately captures the complexity of multi-positioned elites such as CB governors. The challenge lies in effectively accounting for the overlapping roles and activities to unveil field dynamics in global monetary governance and its sub-spaces. Based on an in-depth qualitative analysis and case studies using web sources, we outline four observations that contribute to the interpretation of our statistical findings.

Linkages between central banking, academia, and finance

We observe various cases of ‘insider’ governors, having primarily built careers in central banks, engaged in teaching within academic institutions and publishing in scientific journals concurrently. Although their primary career was not academic, these overlaps emphasize the close ties between central banking and the scientific field. However, further research is needed as these cases do not represent a global trend. Furthermore, various cases suggest that the ties between central banking and the scientific field might be more complex and collateral than they appear, as other fields, particularly finance, exert a strong influence on these trajectories (Box 1).

Box 1. Armínio Fraga Neto, Former Governor of Banco Central do Brasil (1999-2003).

Notes: Prepared by cross-checking Fraga’s profile on his (English and Portuguese) Wikipedia pages (“Armínio Fraga”, 2023a; 2023b) with his other online biographies including Yale School of Management (2013), Govtech Brasil (n.d.), CEBRI (n.d.), and the World Economic Forum (n.d.).

Education

-

• Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-RJ): Economics

-

• Princeton University: PhD in Economics

Academic experience

-

• Lecturer (Economics), PUC-RJ and Getulio Vargas Foundation Graduate School of Economics (1985-1988)

-

• Visiting Assistant Prof. (Economics), Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania (1988-1989)

-

• Adjunct Professor of International Affairs, Columbia University (1993-1999)

Experience in central banking

-

• Intern, Fed (1984)

-

• Director, Department of International Affairs, Central Bank of Brazil (1991-1992)

-

• Governor, Central Bank of Brazil (1999-2003)

Experience in financial sector

-

• Chief Economist and Operations Manager, Garantia Investment Bank (1985-1988)

-

• Vice President, Salomon Brothers (1989-1991)

-

• Managing Director, Soros Fund Management LLC (1993-1999)

-

• Founder and President, Gávea Investimentos (2003-present)

-

• Chair of the board of directors, BM&F BOVESPA (2009-2013)

Non-profit organizations

-

• Trustee of Princeton University

-

• Member of the advisory board of Columbia Global Center Rio de Janeiro

-

• Member of the São Paulo Fernand Braudel Institute of World Economics

-

• Board chair of the Institute for Health Policy Studies

-

• Trustee at the Brazilian Center for International Relations

-

• Member of the Group of Thirty and the Council on Foreign Relations

An exemplary illustration of interconnections between academia, finance, and central banking is seen in the trajectory of Armínio Fraga Neto, the former head of Banco Central do Brasil (BCB). While he lectured in academic institutions including USA Pennsylvania and Columbia universities and gained experience in central banking, his primary professional career was in private finance. He occupied important roles in financial giants such as the Wall Street based Salomon Brothers, the Soros Fund Management and Garantia Investment Bank and chaired the board of BM&F Bovespa, Brazil’s securities, commodities and derivatives exchange. He founded and chaired Gávea Investimentos, which he sold to JP Morgan and then bought back. Throughout his transnational financial career, Fraga maintained close ties with the scientific field, including universities and other research institutions specialized in international relations, economics and public policy studies, and published in the areas of international finance, macroeconomics, and monetary policy. A member of influential global policy advisory bodies, including the Group of Thirty and the Council on Foreign Relations, Fraga was also one of Joseph Stiglitz’s nominees to chair the World Bank.

The transnational links between finance, academia, and central banking are typical of a recurring profile. Similar dynamics are observed in the trajectory of Ilan Goldfajn, another former BCB governor and Fraga’s partner in Gávea Investimentos. Israeli-born Goldfajn’s profile is even more transnational with direct links to influential financial IOs. After studying economics at the PUC-RJ, and earning a PhD at MIT, Goldfajn maintained ties to the scientific field, publishing and teaching in academia, while building a career in private financial institutions, including Itaú and Credit Suisse, and at the IMF. Following his tenure as deputy CB governor (2000-2003), Goldfajn returned to the BCB as governor (2016-2018), before holding important positions at the IMF and the Inter-American Development Bank (Ilan Goldfajn, 2024; IADB, 2022; IMF Communications Department, 2021).

These case studies suggest that not only the links of the scientific field with central banking but also with the world of finance merits further attention. In most cases, the links between central banking and finance are much stronger than those with academia, and they are, of course, also observed in less academically qualified governors.

Central banking at the intersection of public finance and global private finance

Our second observation situates central banking at the intersection of public finance and global private finance. These connections are apparent even in regions like the Middle East, where the financial system diverges from the standard rules and instruments of global finance (Lebaron and Dogan, Reference Lebaron, Dogan, Galonnier, Fer and Angey2025). North Africa and West Asia CB governors show no significant deviation from global trends (see the MCA results in Figure 14, Appendix). In fact, if Islamic finance fits so well into the global finance landscape, this is also due to financial elites such as CB governors who forge strong links between public and private national, regional, and global institutions. Monetary authorities in Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain, the UAE, and others in the region display a convergence between these institutions, as evidenced by governors moving between multinational finance firms and sovereign funds. These governors rarely hold the academic credential of a PhD, mostly holding Master’s degrees in finance or other management sciences, including MBAs obtained from the USA or the UK.

Despite these governors’ strong ties to the public sector, the political leadership does not hesitate to intervene when CB policies conflict with its plans. One example is Faris Abdel Hamid Sharaf who was appointed governor of the Central Bank of Jordan (CBJ) in 2010, but was forced to resign the following year under pressure from the government after criticising its economic policies, which expanded the subsidy programme to strengthen support for the royal family in response to protests. Reuters reported that: ‘Prime Minister Bakhit, […] was quoted in local papers as saying U.S.-educated Sharaf’s liberal leanings and advocacy of free-market economics ran contrary to the government’s programme for expanding social welfare’ (Al-Khalidi, Reference Al-Khalidi2011). After obtaining a master’s degree in economics from Georgetown University, Sharaf has worked for private financial institutions including the UAE’s Dubai International Capital, the Capital Bank of Jordan, the Washington-based International Finance Corporation, and the Amman Financial Market. He also served as deputy CB governor (2003-2007) and head of the Social Security Investment Fund (MEED, 2011). After leaving CB governance, he became an advisor to Arab Bank (Market Screener Editorial Team, 2012). This example shows the circulations within the globalized field of finance highlighting the public-private affinities, but also the complexities, tensions and entanglements between central banking and political regimes. The revolving door of CB decision-makers ‘swinging back and forth from regulator to regulated industry’ (Adolph, Reference Adolph2013: 15) has strong implications in the political field, as we will further elaborate below.

Interdependence between central bank governance and the political field

Statistical analysis has shown that a countervailing trend to the scientization and distancing of central banks from politics is the appointment of political actors, including party members, mayors, parliament members, ministers, their deputies or secretaries, to CB leadership. The connections with finance ministries are even more evident. An example is the incumbent governor of the Banco Central de Bolivia, Roger Edwin Rojas Ulo. This PhD economist began his career as an economic researcher at the Finance Ministry eventually serving as deputy minister between 2008 and 2015. He also headed the Bolivian development bank, Banco de Desarrollo Productivo, and worked for the IMF as an advisor before his appointment as CB governor in 2020 (BCB, n.d.).

This trajectory and various other cases suggest that finance ministries serve as training centres producing elite advisors and administrators, certifying their expertise and increasing chances to access monetary governance. Does the investment of finance ministries in economic research departments and PhD economists constitute a new phenomenon related to scientization or the global ‘professionalization of economics’ (Fourcade, Reference Fourcade2006)? Or does it confirm that economics, like other social sciences, is an inherently governmental science since its origins as political economy (Foucault, Reference Foucault2004)? While further research is required, it is evident that economists often circulate between political and bureaucratic fields, the field of global finance, central banks, academia, and international organizations (see also Christensen, Reference Christensen, Byrkjeflot and Engelstad2018; Davis, Reference Davis2017; Markoff and Montecinos, Reference Markoff and Montecinos1993). This is characteristic of the social space of elites, observed through various interconnected fields of power (Denord, Palme, and Réau, Reference Denord, Palme and Réau2020; Kauppi and Madsen, Reference Kauppi and Madsen2014).

The movement is not unidirectional. Governors often transition into political roles (e.g., ambassador, prime minister, finance or other minister, president or their advisors) after leaving the CB, amplifying the connection and porosity between the two fields. This link exists globally, while in certain cases the political and central banking fields entirely overlap, as in communist regimes where only party members are nominated to the CB governance. There are other countries whose monetary authority is not only a state institution, but also directly controlled by the finance ministry.

Examples can be found among monarchies in Asia that share certain features of governance with the Islamic monarchies of the Middle East. In Brunei Darussalam, for example, the Deputy Finance Minister appointed by the Sultan leads the central bank (MOFE, n.d.). The trajectories of past and present governors in this country provide an extreme example of the intertwining of political and bureaucratic fields with central banking. However, these interconnections manifest in different ways in most countries. In Bhutan, for example, the Royal Monetary Authority (RMA), founded in 1982, was governed by the finance minister until the relatively recent reform in 2010, which reinforced its autonomy and authority.Footnote 6 However, political dynamics since Bhutan’s recent transition to constitutional monarchy explain this process better than scientization. The Constitution of 2008, which established a parliamentary government, authorized it to manage the monetary system.Footnote 7 This power shift is counterbalanced by the 2010 RMA Act, which empowers the king to appoint the CB governor whilst the deputy governors are appointed by the government (RMA, 2018b).

The always relative autonomization of central banking depends on political dynamics, competition, and interests at stake within the field of power, and does not necessarily imply complete separation from the political field. For example, in the Maldives Monetary Authority, officially governed by the finance minister from its establishment (1981) to the 2007 amendment providing formal independence (MMA, 2023), the appointed governors remained deeply involved in politics and bureaucracy. The CB chair was rarely occupied by individuals without direct ministry connections.

The observation that central banking is still part of the political field, with intricate links with state bureaucracy and elected government, is further supported by various cases in which, after unexpected departures in CB governance, the economy or finance ministers or ministerial officials lead the CB until the official appointment of a new governor. An example is from Ecuador, where the Coordinating Minister of Economic Policy temporarily chaired the CB between 2012 and 2013 after the governor admitted having faked his university degree and resigned due to pressures (Gill, Reference Gill2013).

We might add to these observations that the establishment of central banks in the post-colonial world often saw leaders deeply entrenched in the political struggle for independence and state reconstruction. The case of Saïd Ahmed Saïd Ali (1945-2018) in Comoros exemplifies such political involvement from its independence in 1975. A graduate of the Ecole Nationale des Douanes in France, Saïd Ahmed Saïd Ali became involved in politics in his twenties and joined the Comoros Socialist Party (Pasoco) campaigning for national independence. While taking part in the struggle, he worked as a civil servant in the Finance Ministry and later as Deputy Director General of Customs. He was elected municipal councillor for his native city, Moroni, in the first municipal elections following independence. After a brief political imprisonment, he pursued his political career, joined the government, and occupied important positions including Finance Minister and Economy Minister. He served as the CB Governor between 1996 and 2001. He then became involved in local development activities and was elected Moroni’s mayor in 2007 (Mmagaza, 2018; Al-watwan, 2018; Habarizacomores, 2018).

These examples illustrate that central banking remains deeply interconnected with the political field, showing a high degree of porosity between the two fields. Additionally, they reveal the influence of historical, transnational, and power-related dynamics in shaping central banking institutions across different nations.

Monetary governance as a space of imperial influence, scandals, and discrimination

Central bank governance is not a scientized, neutral space, but is structured by national and transnational power dynamics. Notably, the case of Comoros underscores the enduring influence of postcolonial power relations on the supposedly impartial and disinterested universe of monetary governance. The Statuts de la Banque centrale des Comores ( 2010 ), established by the French and Comorian Ministries of Economy and Finance, reveal ongoing French control in CB affairs, including board nominationsFootnote 8 and the tacit authority in appointing the governor.Footnote 9 This is not an isolated instance; various post-colonial states and overseas territories continue to operate under the monetary jurisdiction of their former colonizers, emphasizing that CB governance is not only configured within national politics but also within transnational power relations.

Central banking is a world of political interests and conflicts. Political interventions frequently prompt premature changes in CB governors. While the median mandate length is 5 years, over 70 governors in our database were replaced before their second year, and in total, 206 held their positions for three years or less, showcasing the prevalence of early replacements. In certain regions like Southern Asia and South America, a significant 29% of mandates endure for two years or less, portraying the political context’s influence on CB governance stability. In Central and Southern Asia and South America the median mandate lengths are around 3-4 years, whereas in Oceania and Western Europe they extend to about 9-10 years. Longer mandates are often linked to support from the ruling party, especially in Western and Eastern Asia, which concentrate longest mandates lasting between 15 and 30 years in 14-15% of cases.

The longest tenure in the database, 33 years, is in Eastern Europe, held by Mugur Isărescu, the head of the Băncii Nationale a României since 1990, barring a one-year tenure as prime minister in 2000. His prior role in strengthening relations with the USA, IMF, and WB as an official of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs during Romania’s transition from the communist regime might have contributed to securing this extended mandate (Mugur Isărescu, 2024). However, instances of extended tenures also exist alongside allegations of corruption, as seen with Riad Salamé, a former Merrill Lynch banker who has led Banque du Liban from 1993 to 2023 and faces international legal issues related to alleged embezzlement and money laundering (Riad Salamé, 2024; Sallon, Reference Sallon2023).

Corruption scandals are not uncommon and can lead to investigations, legal actions, and flights abroad. Some CB governors are suspected of involvement in offshore activities, such as those detailed in the Paradise Papers (ICIJ, n.d.) and other offshore leaks documents with several examples from the British ‘overseas territories’.

Far from being the idealized ‘rational’ and ‘scientific’ decision-making space, CB governance is marked by imperial or private financial interests, corruption and conflicts. Religion also has a part to play. In fact, religious capital, alongside scientific or professional capital, and in relation to particular political and economic configurations, is an often ignored but rather important and influential component of CB governance not only in the Global South but also in the North (Lebaron and Dogan, forthcoming Reference Lebaron, Dogan, Galonnier, Fer and Angey2025). CB governance is also marked by ideological struggles and discrimination. As we have seen, 93% of governors in the database are men. CB governance is a possibly patriarchal universe that discriminates against women and probably other minorities.Footnote 10 All these factors invite us to reconsider the narrative of a ‘scientized’ and ‘neutralized’ universe of central banking.

Conclusion

This study provides theoretical and empirical contributions to the central banking literature. It sheds light on a ‘politics of scientization’ that responds to neoliberal agendas, seeking scientific legitimacy in CB governance while concurrently depoliticizing monetary policy. Rather than aligning our definition of scientization with the discursive practices of influential central banks, we proposed a sociologically grounded framework to analyze scientization as a social-historical process that potentially alters the power dynamics between different fields in monetary governance in favour of the scientific field.

The examination of the biographical profiles of CB governors reveals that the data does not substantiate the hypothesis that academic professionals and qualified scholars are supplanting less scientific actors from political, bureaucratic, or financial backgrounds. Our results suggest that economic technocrats, rather than scientists, govern money.

The analysis also shows that the share of economists is substantially higher than governors from other disciplines, hinting at a potential saturation point. Exploring prior periods could illuminate whether there have been historical periods where economists were not the predominant group in CB governance and whether their prevalence was part of a more extensive ‘rise of the economists’ in the latter half of the twentieth century (Markoff and Montecinos, Reference Markoff and Montecinos1993). Our findings indicate that if there was an increasing trend, it did not persist consistently beyond the 2000s. Counter-tendencies, particularly observable in the developing world after the 2007-2008 financial crisis, suggest a possible plateau or even a reversal, even though economics remains by far the most important discipline giving access to monetary governance.

The preponderance of degrees in economics and, secondly, in management sciences in the training of CB leaders aligns with the observations of Fourcade and Khurana (Reference Fourcade and Khurana2013) regarding the rise of these disciplines and their ‘ecological linkages’ in neoliberal governance. Economics as an expert, scientific practice is a globally institutionalized field described in the literature as a ‘global profession’ (Fourcade-Gourinchas, 2001, Fourcade, Reference Fourcade2006) and a ‘global science’ (Dezalay and Garth, Reference Dezalay, Garth, Mallard, Paradeise and Peerbaye2010), entrenched in a vernacular and underpinned by a shared set of training and qualification standards. However, the symbolic value of an economics diploma differs across academic institutions, with US and British universities predominantly shaping and training the most influential economists worldwide (Fourcade-Gourinchas, 2001, Fourcade, Reference Fourcade2006; Dezalay and Garth, Reference Dezalay, Garth, Mallard, Paradeise and Peerbaye2010). Our study confirms the insights of earlier research, affirming the significant influence of economists trained in the USA and the UK (Lebaron and Dogan, Reference Lebaron and Dogan2016, Reference Lebaron, Dogan, Denord, Palme and Réau2020). However, rather than indicating the preeminence of the scientific field in the broader power structure, this finding underscores the highly asymmetric nature of this field. Northern academic institutions serve as hubs of training and dissemination of dominant knowledge, contributing to symbolic imperialism.

The field of economics is characterized by globalized trajectories and a constantly evolving, ‘globalized logic’ that is responsive to the economic transformations it engenders (Fourcade, Reference Fourcade2006). Our study illustrates that monetary governance is integral to this process. While we observe a substantial proportion of governors with PhDs in economics, we argue that this trend is associated more with a process of professionalization than scientization. Central banks select their leaders predominantly from economists with insider central banking experience or careers in state bureaucracy, especially in public finance. The analysis of governors’ professional backgrounds suggests that economic technocrats – ‘econocrats’ (Froud et al., Reference Froud, Nilsson, Moran and Williams2012) – rather than economic scientists preside over monetary policy. Further research may provide insights into how this trend relates to broader observations in positions of power in state institutions regarding the increasing proportion of elites who have an educational and/or professional background in economics and related (business and management) fields. According to Davis (Reference Davis2017), this professional econocracy contributes to maintaining elite cohesiveness through three key mechanisms: It (1) facilitates the mobility of elites across institutions and sectors; (2) unites disparate groups around a shared neoliberal ideology and associated interpretive frameworks translated across elite groups and networks; which (3) operate as a form of governmentality based on common tools, techniques, and mechanisms, especially of neoclassical economics, financialization, and audit systems.

CB leaders are often well integrated into the bureaucratic field, notably in public finance, while maintaining close ties with private finance. The importance of financial sector experience is highlighted by our statistical results as well as qualitative case studies, which additionally reveal career orientations towards private finance after leaving CB governance. Moreover, our case studies indicate strong links with financial lobbies, think tanks, and clubs such as the Group of Thirty, which are influential in setting global financial rules (Tsingou, Reference Tsingou2015).

In fact, the revolving door of regulator and regulated, highlighted by studies on monetary policymakers (Adolph, Reference Adolph2013; Carré and Demange, Reference Carré and Demange2017), is stronger than the mobility between academia and central bank leadership. At the top of central banks, we do not find scientists but rather financial elites moving between central banks and executive roles in financial institutions such as banks, and investment and insurance companies. This observation is consistent with the existing literature on the historical entanglements between finance and central banking, and the role of the latter in developing the governing techniques at the heart of contemporary policy regimes of financialized capitalism (Wansleben, Reference Wansleben2023, Reference Wansleben2024). The revolving door between central banking and finance has specific consequences in terms of policy choices and orientations (Adolph, Reference Adolph2013), misaligning public and private interests (Coombs, Reference Coombs2024) and turning central banks, in certain cases, into ‘key allies’ of the financial sector (Kalaitzake, Reference Kalaitzake2019).

As a consequence of elite circulations, central bank governance is often structured as ‘closed policy circles’, highlighting the interdependence between the state and the financial sector and the privileged position of the latter within policy battles (Kalaitzake, Reference Kalaitzake2019: 2). Our study also reveals the revolving door intersecting CB governance with the political and bureaucratic fields, which requires further investigation. These observations contradict the scientization hypothesis according to both Marcussen’s (2006; 2009) and our own definition. In fact, our statistical and qualitative findings depict a more complex global configuration than scientization and depoliticization (or apoliticization). Central banks, especially in the Global South, remain within public finance at the intersection of political and bureaucratic fields, rather than becoming autonomous scientific institutions. Furthermore, the coexistence of academic and political governors blurs the supposed separation between the scientific and political fields, even in the Global North. Expertise for monetary governance develops at the intersection of these fields with (public and private) finance, and notably within the field of central banking itself. While there are academic governors, they remain a minority when compared to main-career central bankers and public administrators and do not exhibit a discernible upward trend.

Although more governors in the developed world possess scientific credentials (PhD, main career or experience in academia), classifiable within the AHC cluster of academics, the Global North still presents a variety of profiles. Even in this region, which appears more homogeneous than the Global South, academic governors are a minority compared to central bankers and public administrators, and the available data does not support a conclusive pattern of growth in their numbers.